1. Introduction

The advent of the fax machine brought about a revolution, providing artists with new opportunities for creative expression, communication, and research. The term “Fax Art” is used to describe artistic proposals that employed the fax machine as a creative tool, transgressing its initial use. It did give rise, from the late 1970s to the 1990s, to groups of artists, mainly belonging to the Mail Art and Copy Art movements, who exploited the fax machine to instantly transmit works usually created on the basis of the xerographic language of photocopy machines. Owing to this, the relationship between Mail Art, Copy Art and the use of fax is strength so, as it will be explained in this text, the majority of artists experimenting with fax were part of the Mail Art and, mostly, Copy Art movement (Escribano, 2016; Escribano, 2017; Firpo et al., 1978).

The fax process is based on a point-to-point transmission and a synchronized reproduction and printing of the image. Essentially, it was a technology combining an image scanner-transmitter, a telephone modem, and a receiver-printer. The scanner converted the graphic document into analog or digital signals, which were sent through the telephone line to another fax machine that reproduced the document at a different geographical point. In fact, this is an interesting artistic aspect, as the artist did not have control over the receiver one, which would be in charge of materializing the artwork.

There was a necessary interaction between sender and receiver for the artwork to be finally done. Therefore, the graphic language became as relevant as the communicative aspect. In other words, a work could be considered Fax Art if it was transmitted, making the process, collaborative and communicative aspect the focal points.

2. Historical Events

In 1842, scientist Alexander Bain (1818-1903) constructed the first facsimile device. This machine was capable of reproducing low-quality images, not entirely visible due to a lack of synchronization between the transmitter and receiver. Five years later, F. Bakewell (n.d.) discovered the basis of the synchronized system using cylinders. But the first functional system emerged in 1861, thanks to the Italian Abbe Caselli (1815-1891), who achieved a facsimile teletransmission between Paris and Lyon using the Pantelegraph.

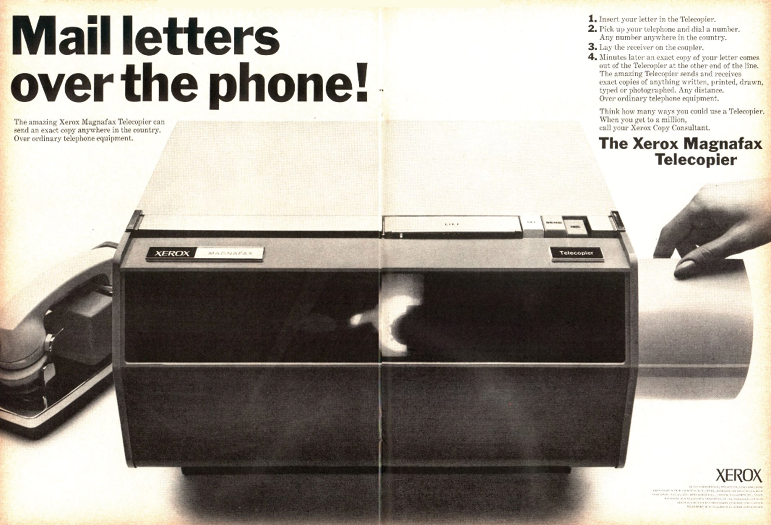

In 1922, the first transatlantic facsimile service was established by Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which transmitted a photograph in 6 minutes. In the same year, Arthur Korn (1870-1945) sent a photograph of Pope Pius XI from Rome to Bar Harbor (Maine, USA), employing a device with a photoelectric scanning method. Subsequently, faxes began to be used, particularly for the transmission of weather maps, police records, and press photographs, to establish collaboration, exchange and circulation of information. In 1948, Western Union built a facsimile machine for commercial purposes, but it was with the Magnafax telecopier in the 60s, when the devices we know were developed.

The artistic use of this technology has been occurring since the late 1960s. A tool in which transmission, collaboration, and the network of image exchange are the bases, giving rise to the graphic language of poor images. Early faxes employed thermal printing that required specific paper, and only a few used laser printers. With the advent and cost reduction of inkjet printing, there was a surge in normal paper faxes, transforming them into multifunctional devices.

Equipped with a scanner and a printing system, the fax machine worked similar to a photocopy machine, which is one of the reasons why the majority of artists belong to the Copy Art movement. Indeed, in 1964, Xerox Corporation, that introduced the first automatic photocopy machine Xerox 914, patented the version of a fax machine named “Long Distance Xerography” (LDX). Then, Xerography1 was also used to create the first instant transmission medium for documents across spatial barriers. Kate Eichhorn addressed the topic and stated that:

With the introduction of the Xerox Long Distance Xerography System (LDX) in 1964, Xerography –by then already recognized as a compressor of time in document reproduction– showed its potential to compress space as well by enabling documents to be transmitted across long distances in a matter of minutes. (2016, p. 17)

Successively, in 1966, Xerox introduced the Magnafax Telecopier that was easier to handle and could be connected to any standard telephone line. Before the fax boom, one of the early models was the Exxon Qwip6, which operated exactly like a photocopy machine, using the optical reading of the graphic element reflected onto a drum. The reflected light was sent to a photocell in which the electric current in the circuit varied with the amount of light. This current controlled a tone generator that defined the frequency of the next tone transmitted using an acoustic coupler connected to the microphone of a telephone handset. At the receiving end, a headset speaker was connected to an acoustic coupler (a microphone), and a demodulator converted the variable tone into a variable current that controlled the mechanical movement of the pen or pencil. Thus, the image was reproduced on a blank sheet of paper positioned on a rotating drum at the same speed. The first digital fax machine was developed by Dacom, based on digital data compression technology advanced at Lockheed Corporation for satellite communication.

Moreover, the specific technical features of the medium allow it to be considered in relation to the use of the xerographic language and, therefore, Copy Art. Once transmitted, the final piece was a xerography hardly distinguished from one produced by a photocopy machine, except for the indicators of the phone, date, and time printed on the received fax sheet:

Fax Art? At that time it was fantastic that you could send a copy of your artwork in some seconds to another city or country for example directly in an exhibition room. The Fax machine was a good technical help and the (almost) contemporaneous aspect was new and exciting. (Kierspel, 2016)

It must be clarified that this discourse is framed within historical Media Art, and within those structures being revisited through the Media Archaeology. It is from this standpoint that new data is sought to contribute to the speculations developed over the past 50 years in this field. There is a desire to rethink the purely technicist focus these practices have been treated with, as well as the scarcity of publications that theorize about the artistic aspect, in order to acknowledge the undeniable relevance in the historical Media Art.

3. Methodology

Considering that this research reviews a recent past to establish commonalities with the present, the canonical methodologies of study proved inadequate as they rely on traditional parameters. Art, being a way of perceiving the world, has evolved; consequently, the methodology for elucidating the history of art in each era must progress. It is illogical to apply a historiographical methodology based on traditional art to these artistic practices that challenge established art paradigms, entailing the loss of aura and uniqueness due to transmission and reproducibility (Benjamin, 1969), the rupture of traditional concepts such as original, copy, unique, and multiple; the distancing of the artist as a creative genius, the process as research-creation, or the automation and immediacy in the creative process.

To comprehend the value of the artistic practices involving fax begins by situating ourselves in that context, understanding the developments and the environment that cultivated them. Therefore, the methodological approach of Media Archaeology is employed to assert these artistic practices which constitute part of the historical roots of Media Art – alongside the practices involving photocopy machines, video cameras, and computers. Considering all the aforementioned, a deep archaeology was self-imposed for this research, grounded in a critical consideration and study surrounding the main artists, artworks, productions, historical publications that have been marginalized in the official art texts to date.

Media Archaeology started paying particular attention to the materiality of media and seeks to engage different dimensions. For example, the media itself, the historical context, the infrastructure of appearance in the market, the modes and content production, circulation, among others. For this limited text, this study underlines the fax artworks, which, clearly, depended and were shaped by the features and limits of the machine itself, but also the technical, artistic, social, and political context.

Media Archaeology rejects linear genesis, and situates these practices in the context of their production, emphasizing their characteristics. Although following the words by Thomas Elsaesser (2016), the term Media Archaeology means slightly different things for those who practice it (see Elsaesser, Ernst, 2011; Huhtamo y Parikka, 2011; Kittler 1986; Zielinski, 2006) among others), what unifies them is “[…] the discontent with linear narratives of the ‘from ... to’ variety, the need to ‘read [media history] against the grain’, to provide ‘friction’, uncover ‘layers’, ‘probe strata’ and to ‘dig out’ forgotten, suppressed and neglected histories [...]” (Elsaesser, 2016, p.183). And, from this point of view, one of the relegated parts is the fax machine figure and its use as a creative tool.

To centralize this discourse from an artistic perspective, the methodology of this research, initiated in 2014, has followed several stages, the results of which are briefly summarized in this article. First, a bibliographic review was conducted on the topic of fax, as well as its relationship to Mail Art and Copy Art, consulting books, articles, exhibition catalogs, doctoral theses, manuscripts, and press materials. Many of these publications were found in museum libraries such as the one in MIDECIANT (Cuenca), MUSINF (Senigallia), Museum für Fotokopie (Mülheim), and the Centre Pompidou (Paris), among others. Documentary materials created by the artists themselves (memoirs, texts, photographs, VHS videos) were also analyzed, located in these and other museums, centers, and private collections, for example, the Fondazione Jacqueline Vodoz e Bruno Danese (Milan), the private museum of Karin und Uwe Hollweg (Bremen), the Archiv-Black Kit archive of Boris Nieslony (Cologne), and by artists like Jesús Pastor, Pierluigi Vannozzi, Rubén Tortosa, Jean-Pierre Garrault, Marisa González, and Franz John.

Then, due to the limited literature available on the subject, a database was designed to organize the main ideas, key concepts, and artistic approaches to working with fax. Once the literature review was completed and the key concepts identified, the aim was to distinguish the various artistic practices and uses of fax. To this end, and because one of the primary sources of information is the interview, artists were interviewed to gain first-hand insights into their practices and the connection between Fax Art, Mail Art, and Copy Art. To identify the most relevant artists to interview, the study began with those established in the literature review, many of whom belong to the Third Generation of Copy Art2. It should be noted that not all artists were included, as many used fax sporadically without developing a continuous practice with the medium.

The interviews were conducted during work and research stays in Venice (Italy), Krems an der Donau (Austria), Bremen (Germany), Paris (France), Winchester (UK), Glenside (USA), and Spain (country of residence). These visits focused on key locations, including museums, collections, and both public and private archives. Although the interviews were limited to the European context, they granted access to private collections by artists such as Franz John, Jürgen Kierspel, Jürgen O. Olbrich, Jesús Pastor, Lieve Prins, Jean-François Robic, Daniele Sasson, Pierluigi Vannozzi, among many others

Simultaneously, an analysis was conducted of the artworks present in the museums, collections, and archives visited, which allowed determining the influence of the medium’s specificity on the graphic language. This analysis also highlighted how artists used fax with the necessary collaboration, transmission, and circulation of images, thus generating the poor image representative of Fax Art. The information on all the works accessed was organized into a database designed for this purpose. The combination of the literature review, direct interviews with artists, and the study of artworks have been fundamental in shaping this research.

4. Mail Art- Copy Art- Fax Art

It can be contemplated that Fax Art had drawn inspiration from the concept and way of working of Mail Art and the network of contributors united by the pleasure of practicing art outside the conventional system. The most important feature of both Fax Art and Mail Art is the priority of communication, collaboration and exchange among different artists.

Fax Art required the presence of a sender, a channel (the fax), and a receiver. It was similar to Mail Art, but the fax machine could transmit the artwork in real time, representing an evolution within telecommunications, as the receiver fax machine and person were in charge of finishing the process and the work, in many cases. This gave rise to a spatial-temporal flow between different places that would be revolutionary at the time.

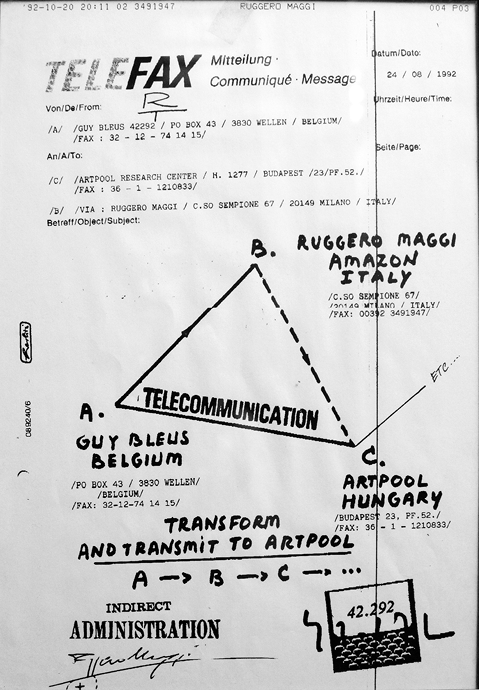

In fact, Fax Art became integrated into many postal projects to send and receive artworks or to create chains of collaboration, as it was the case with Guy Bleus (see Figure 1), Piermario Ciani, or Hans Ruedi Fricker. In this sense:

Fax Art was an ‘event’ where the artist could transmit the image but didn’t have complete control over the receiver’s equipment, so the aesthetic aspect of fax art is secondary compared to the communicative aspect [...]. It could be considered a type of Mail Art that, when transformed into electronic form, keeps the Eternal Network alive with a fax. (Bleus, 1994, p. 42)

Figure 1. Guy Bleus. Instructions for a fax event with Ruggero Maggi and Artpool Hungary. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

Bleus spoke about “Telecopy” on the electronic network, considering that “The world is a fax-village” (1994, p. 40). Instead of Fax Art, he chose the term “Telecopy Art”, keeping the word “copy”, to highlight that it was a similar process to the one with the photocopy machine. Certainly, if it was related to any artistic movement, it was to Copy Art, which transgressed the photocopy machine as an artistic tool. Since the sixties, groups of artists globally became attracted to the immediacy of its reproduction and printing process. These artists took the media specificity of the machine, its characteristics and limits, as opportunities for creative expression and visual language.

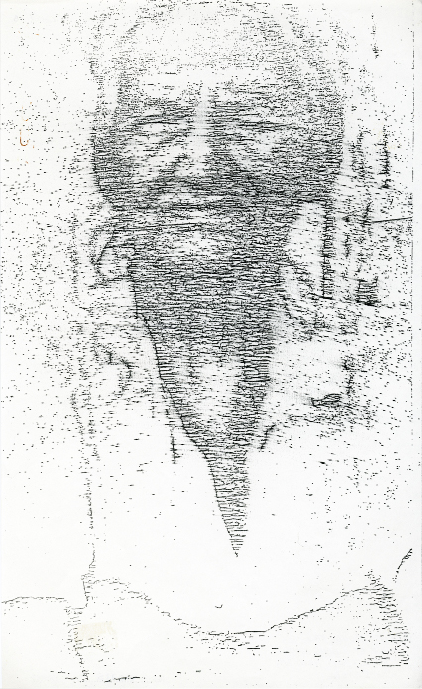

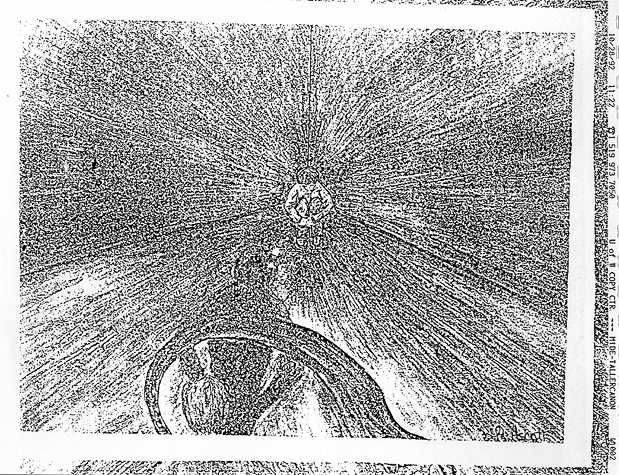

Many artists who produced art with the fax machine were also those who transgressed with the photocopy machine. Why? The reason is that once transmitted, the resulting fax is similar to a xerography with the indicators from the telephone, date, and time printed on the sheet by the receiver’s device, as it can be realized in Figure 2 and 3. Actually, it was the need of going on researching the concept of time-space in collaboration with other artists, which motivated them to use faxes. The relationship between the space-time of the sender and the one of the receiver in the transmission process was the clue.

Figure 2. Marik Boudreau. Untitled. 1984. Monochromatic xerography. 35 x 21 cm. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

Figure 3. Roy Ascott. Untitled. 1992. Tele-transmission (fax) and xerographic print on paper. 21 x 26,5 cm. Fax Action ‘Fax AUDA-Cuenca’. Received: 10/28/1992, 11:22 AM. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

In general, in places where there was experimentation with photocopiers, there was also experimentation with fax machines. Spain exemplifies this trend through the efforts by the International Museum of Electrography in Cuenca (Spain), established to safeguard artworks, housing multiple fax machines, too. The museum evolved into a focal point for various international trends, gathering a substantial collection of global works that influenced artistic production both within the museum and in the city of Cuenca.

5. Collaboration, the Central Point

Collaboration was the central element in the creation and dissemination of Fax Art, Copy Art, and Mail Art, which involved a strategy of decentralization. Particularly for those artists in Mail Art, it was an expressive independent channel from the official art system, emerging as a reaction “[...] either to a situation of non-communication caused by the ‘hot media’, or to the limitations imposed by the cultural market”3 (Di Lorenzo, 2004, p. 62). It acted as a form of communication that also proceeded from the revolts of the 1960s and for underground culture, “Money and Mail Art do not mix!” says German artist Jürgen Kierspel (2016).

At the same time, the fact of being a resulting poor image, as it could be read later, created with technologies for commercial reproduction and transmission, meant that it was not valued within the official art system. Owing to this, artists practicing within Fax Art and Copy Art sought to integrate themselves into culture, much like Media Art is doing.

This need to be recognized required the artist not only to be an artist-researcher, collaborating with scientists and engineers, but also to be curator, cultural promoter, collector, theoretical and practical disseminator, and professor of their innovations within this movement (Escribano, 2017). Nevertheless, Fax Art developed its own collaborative strategies through different modes of production and collaboration with fax machines:

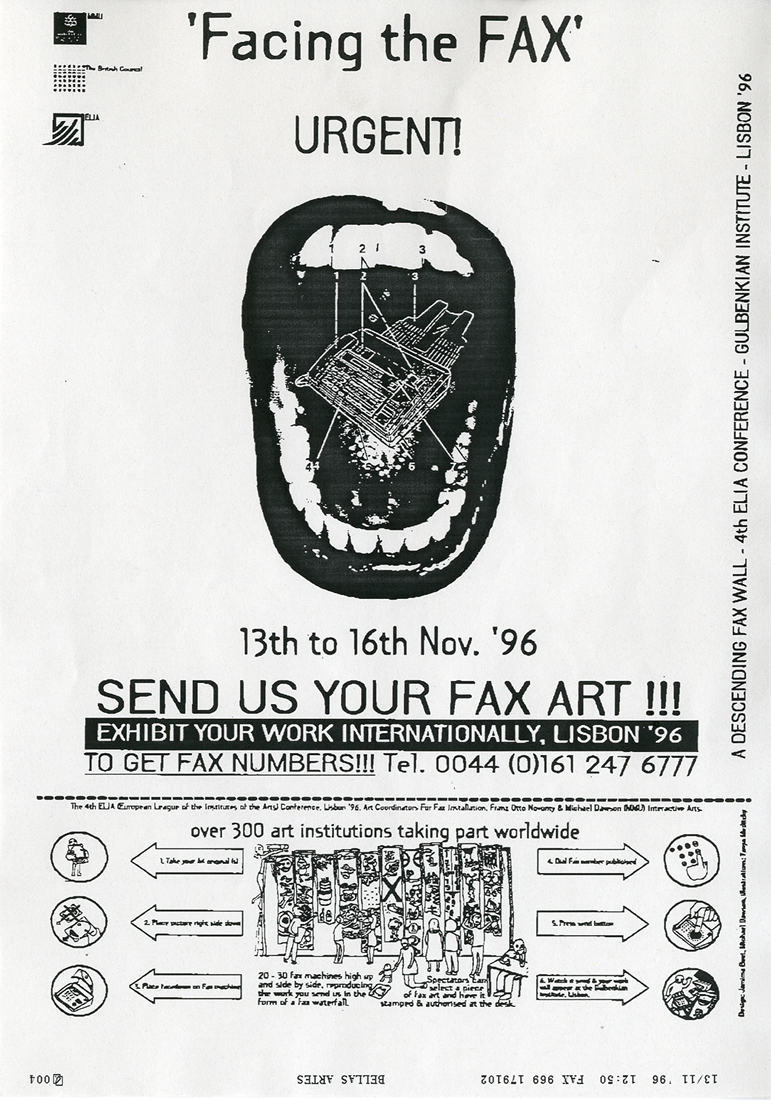

- On the one hand, with the organization of events, exhibitions, meetings, and biennials, which were the best way to bring together artists and power the exchange of knowledge outside the official art.

Figure 4. Call for ‘Facing the FAX’ project. 29 x 21 cm. 1996, Lisbon. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

- On the other hand, with the creation of specified centers for the promotion, dissemination, and preservation of such works, as well as the research on emerging technologies. One example is the Generative Systems Department at the Art Institute of Chicago, where Sonia L. Sheridan taught since 1961 to 1980. This center followed the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts; The Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, and the Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia. Sheridan explained:

Frustrated by the time required for most art processes, she sought speedier ways to create serial images. First becoming intrigued with a Xerox photocopier, and then moving on to the 3M Thermo-Fax, Sheridan brought her unique creativity to the manipulation of the machine to produce her art. (Kirkpatrick & Sheridan, 2009, n.p.)

The Centre Copy-Art in Montreal was also established, where Philippe Boissonnet placed a fax machine for artistic research; and the Centre Xeros Art in Milan, by Celeste Baraldi, Giuseppe Denti, or Marcello Chiuchiolo. Jean Mathiaut founded Media Nova Center in Dijon (France), Klaus Urbons instituted the Museum Für Fotokopie in Mülheim (Germany); and helped (with Christian Rigal) to create the International Museum of Electrography in Cuenca (Spain), by José Ramón Alcalá and Fernando Ñíguez. In Budapest, the Hungarian Museum of Electrographic Art was established in Szombathely, based on the private collection of the Revue d’Art 90º association and Joseph Kadar.

In some cases, Fax Art emerged as a political collaborative event in works such as Office of Information about the Vietnam War (1968) by David Lamelas for the Venice Biennale. This artwork incorporated images, audio, and text, introducing real-time updates through a fax machine constantly transmitting news from the war. In the Ars Electronica 1982 edition, Robert Bob Adrian X organized The World in 24 Hours in which artists from three different continents engaged in communication for 24 hours using the telephone, computer mailboxes, television, and fax. Vienna, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Bath, Wellfleet, Pittsburgh, Toronto, San Francisco, Vancouver, Honolulu, Tokyo, Sydney, Istanbul, and Athens participated. Each location received a phone call from Linz at 12:00 local time to initiate the project from 12:00 noon Central European Time on September 27 and progressing with the noon sun worldwide, concluding at 12:00 noon the following day. These are examples of how collaboration and the circulation of images was the central point, giving artists the opportunity to work, for the first time, in real-time connection with between different places.

On January 12, 1985, the Liechtenstein Palace in Vienna became the starting point for a journey around the world that was completed in 32 minutes in the Global-Art-Fusion project. The project reached Joseph Beuys in Düsseldorf, moved on to New York with Andy Warhol, and finally reached Tokyo with Kaii Higashiyama, before returning to Vienna:

As different the form of art may be in which Beuys, Warhol and Higashiyama clad their message, it yet forms a unity, also in the sense of formal qualities: what each of the three artists created was assembled by the telecopying appliance. (Brodrecht, 1985: n/p)

In this case, the final artwork is constructed in the manner of an exquisite corpse: individually but as a part of a whole created in completely different places and diverse time zones. Similar to this, Planetary Network event was organized by the UBIQUA lab during the XLII Biennale di Venezia in 1986, featuring the participation of 24 different stations in Canada, USA, Italy, France, Australia, UK, and Austria. Over the first two weeks, these locations were added to a daily exchange program using fax, slow-scan television, and computer communication. The curators were Roy Ascott, Tom Sherman, Don Foresta, and Tommaso Trini, with Robert Adrian overseeing the coordination of the network.

1991 was an intense year in terms of fax-related actions where collaboration and the circulation of fax images was the key. Connect by Gilberto Prado allowed people in different parts of the world to create a unique real-time artwork through an interactive fax piece (Kac, 2005). Participants needed to have two fax machines at each location. When the messages began to arrive through one fax machine, participants had to feed the thermal paper roll (without cutting it) into the other machine, transforming the images in the process and then sending it to another location. This process generated a loop in the creation between artists and machines and opened the process for everyone to participate outside the official art. The first connection occurred on May 31, between Paris (Université Paris I - Centre Saint Charles) and Pittsburgh (Carnegie Mellon University). This collaboration also works again in a real-time process which is dynamic.

In the same year, the Telescanfax action, during the Machines à Communiquer exhibition in Paris, included artists connected through the telecommunication network. Among the participants were Gilberto Prado, Marc Colson, Pierre Amatore, Michel Suret-Canale, Claire Jovanovic, Thierry Dupuy, Lydie Le Gléhuir, Isabelle Millet, as well as some Copy Art artists, such as Pierre Granoux, Liliane Terrier, and Marisa González. Each creator modified the received image and then marked the branching done on the map, recording the dates of the contact to send it to two other participants in the network. The map’s route was constructed from the image’s branches and transformations, meaning that each participant received the successive stages of transformation that the image had undergone. The final artwork was the result and representation of collaboration, exchanges and not a unique artist.

Between 1988 and 1993, numerous events with similar characteristics took place always with this collaboration and circulation of images in the process: in 1989, Telekomunikatie in Kunst (the Netherlands); Project G.A.I.A. as part of the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz; Art Planet/FR2 – L’Europe des Créateurs in Paris; International Technoculture Reunion at the University of Paris; or El Silencio Homologado at Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona. In 1990, The Longest Fax Line by Alcalacanales in Valencia; Fax at the Faculty of Santa Marcelina in Sao Paulo; or People to People – Manufaxtura in Prague. In 1991, Fake/Faxed/Facade at the National Museum in San José, Costa Rica; Fax Art at CeBIT’91 in Hanover; or Infest. Machines a communiquer at the Cité des Sciences et de la Industrie, in Paris. Additionally, in 1993, Six Continent Fax Performance in Ross, Inverness; Fax Art as part of Montage’93 at the Mercer Gallery in Rochester; or El Árbol de la Vida, in Encuentro Otras Gráficas at UNAM in Mexico.

Besides, numerous international centers related to Art and New Technologies were interested in Fax Art, including the Academie Minerva in Groningen, Netherlands; Art Access Networking, led by Roy Ascott, in Bristol; Art Com Electronic Network in San Francisco; the Art Institute of Chicago with Eduardo Kac; the Centre Copie-Art in Montreal; Cetech in France; École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, with Professor Jean Mathiaut; the Museum für Fotokopie in Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany; and, of course, MIDECIANT in Cuenca. The success of Fax Art during that time was attributed to the search for alternative forms of production and collaboration, outside traditional channels.

Regarding the fax artworks held in the Museum of Electrography - Center for Innovation in Art and New Technologies (MIDECIANT) in Cuenca, this museum features a wide variety of examples created within its own workshops, equipped with the most advanced models of this technology. This museum became the receiver of many creations, and among the significant collection held by MIDE are those works from the 2nd Biennial of Electrography and Copy Art in Valencia in 1988. The artworks correspond to the teleaction-tribute titled 10.22.38 – 10.22.88; Astoria/Valencia, which involved the installation of two fax machines in the same building. The majority of the received works were created on the theme of the 50th anniversary of the first copy by Chester F. Carlson, in 1938, coinciding with the Biennale. Consequently, featuring images of Carlson, the photocopy machine, or alluding to the location and key dates associated with the invention.

Another group of important artworks are those from the XX Biennial of Sao Paulo, 1989, where the fax event Hands of Time was organized with the participation of students from Universidade Estadual Paulista – coordinated by Luiz G. Monforte, the Rochester Institute of Technology – coordinated by Charles Arnold Jr. and Patricia Ambrogi-; and MIDECIANT and the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cuenca – coordinated by José R. Alcalá and Fernando Ñ. Canales. The objective was to connect three countries simultaneously, breaking the political barriers: the United States, Spain, and Brazil. This event started at 2:00 p.m. in Rochester, 3:00 p.m. in Sao Paulo, and 6:00 p.m. in Spain, according to their time zones, and artists from the Biennial started sending various images, created by the professors and artists, to the respective students in each country. These students had an hour to work on the images and send them back to the different connected fax machines and, in turn, back to the Biennial in a completely procedural, collaborative, performative work, constructed in the manner of an exquisite corpse.

Another significant collection of works at MIDECIANT, valuable not only for the artworks themselves but also for the many artists who created them, originates from I Muestra Internacional de Fax, held at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cuenca in 1993. The student association AUDA curated the exhibition, with Arturo Caraballo, Ricardo Echevarría, and Kepa Landa. Among them, some of the most valuable artworks, both conceptually and in terms of collaboration and exchange are explained in the next section.

Thanks to the fax, artists were able to participate in collaborative works and exchanges, creating timeless pieces from various geographical locations in an infinite loop, producing images of poor character as result. All this signified moving beyond the concept of a single genius artist and the breaking the difference between original and copy, since each of the reproduced works through the receiver fax machine were used to continue their collaborations and exchanges. This not only broke geographical barriers, as happened with the Internet, but also political, social, and cultural walls, enabling creation outside the official art system.

6. The Graphic Language of Fax Images

These technologies introduced unique challenges resulting in the graphic quality of fax images, poor ones characterized by low resolution, degradation, loss, and distortion. Clearly, the graphic language of artistic fax creations is closely tied to the media specificity of the machine and that collaboration, exchanges, and circulation needed in the process.

But not only this, to overcome many of the machine’s limitations, artists developed specific procedures. In creating with fax machines, they searched to maintain a dialogue with the machine and became interested in the “black box” (Flusser, 1990, p. 19), too. Thus, the resulting poor image is the result of unstable processes and continuous permutations, where error, chance, play and work are the clue. Error in the process, in collaborating, exchanging and printing the image, entails a change and the appearance of a graphic that had not previously been taken into account in an artistic manner. But, moreover, the fax creation introduced a different aspect: the space-time relationship between the point of emission and the point of reception (Alcalá and Escribano, 2016), the need for collaboration in the process. This is something that gave artists the opportunity to manipulate during the process of reading or transmitting the information.

At the close of this text, the significant collection of artworks held by the International Museum of Electrography - Center for Innovation in Art and New Technologies (MIDECIANT) in Cuenca would be taken as example, the ones which come from the 2nd Biennial of Electrography and Copy Art (Valencia, 1988), the XX Biennial of Sao Paulo (1989), and the I Muestra Internacional de Fax (Cuenca, 1993). Through some examples, it could be understood how the technical limitations of the fax machine and the collaborative creative process itself contributed to the creation of a unique graphic language of poor images.

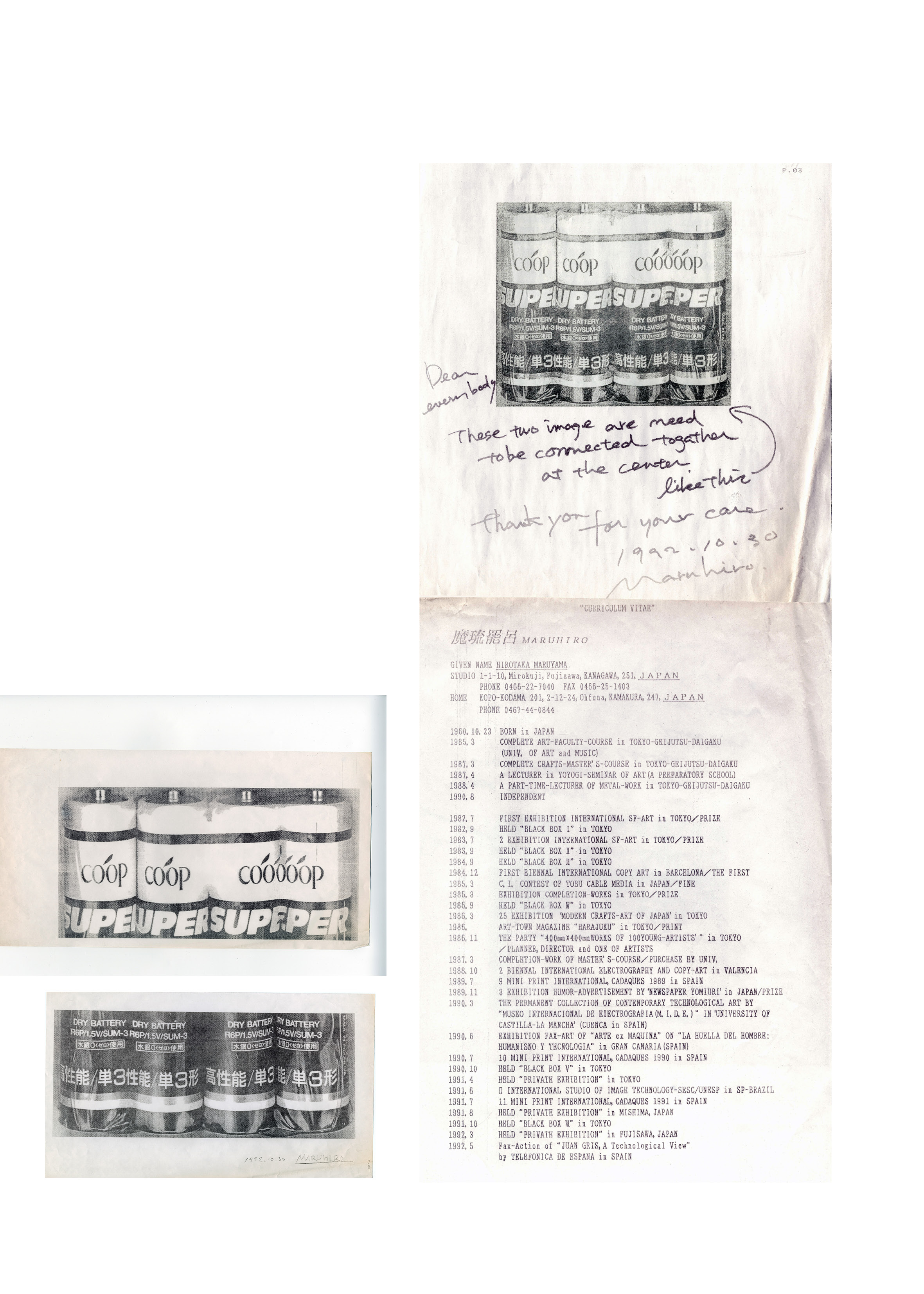

- Size and limited format of the fax machines. Graphically, the configuration of the artwork sheet depends on the fax machines. In the collaborative process, artists could only incorporate small elements, and fragments, and, in larger works, the receiver fax person had to assemble the generated pieces to compose a unified whole. This is exemplified in The Faxed Battery by Maruyama (1992), who fragmented the composition into two pieces and sent them with an instruction sheet to the MIDECIANT. The collaboration with the receiver artist was required to have the final work.

Figure 5. Hirotaka Maruyama (Maruhiro). The Faxed Battery. 1992. Tele-transmission (fax) and xerographic print on paper. 29 x 31 cm. ‘Fax AUDA-Cuenca’. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

But, also, this size limitation gave rise to the process of image fragmentation-enlargement, which became one of the most prevalent artistic approaches in Fax Art: enlarging and fragmenting the base image for transmission. As a result, a larger image is produced, though with a low-quality and degraded graphic outcome, filled with noise and printing dots, along with errors in the conversion of the image into transmittable signals. A notable example is in Khalid Hammoumi’s artwork Sequence nude in 6 parts, in which the artist transmitted a photograph of her nude body, previously enlarged and fragmented into six distinctive parts, from the E.N.B.A. in Dijon (France). Although each segment was sent from the same location, the time of reception print varied as the transmission progressed. This is not only a fax action or a procedural work but also an event in the sense of philosopher Jean-Louis Déotte (2013).

- The horizontal format of the glass for creation: the fatness effect. With the evolution and cheaper use of fax technology, most models started to have a glass for scanning the documents, and artists used it for creation. Xerox, for example, sold the Xerox Magnafax Telecopier I (1966) (see Figure 6), a photocopy machine plus a fax, that started the successful mass production of cheaper fax machines (Coopersmith, 2015, p. 106). This way, artists no longer worked on the vertical classical plane, but they did it on the horizontal plane as “a genuine worktable”4 (Ñíguez, 1986, p. 54), inaugurated with the avant-garde. Due to the horizontal format, objects and other elements were pressed to the machine’s glass, having a particular flatbed iconography in the resulting works, “The flatbed picture plane lends itself to any content that does not evoke a prior optical event.” (Steinberg, 1972, p. 49).

Figure 6. The Xerox Magnafax Telecopier. 1966.

- Undefined and diffused atmosphere consequence of the limited depth of field, so objects positioned approximately 10 cm from the glass lost definition. Moreover, the material contributed to this diffuse atmosphere, as from 1970 to 1990 applied direct thermal printers with rolls of thermal paper. From the mid-1990s onward, thermal transfer printers, inkjet printers, and laser printers had also been used. The material was sensitive to both light and humidity, producing most works to gradually blur. In this context, conservation assumes a significant role, requiring the appropriate storage in black folders to prevent exposure.

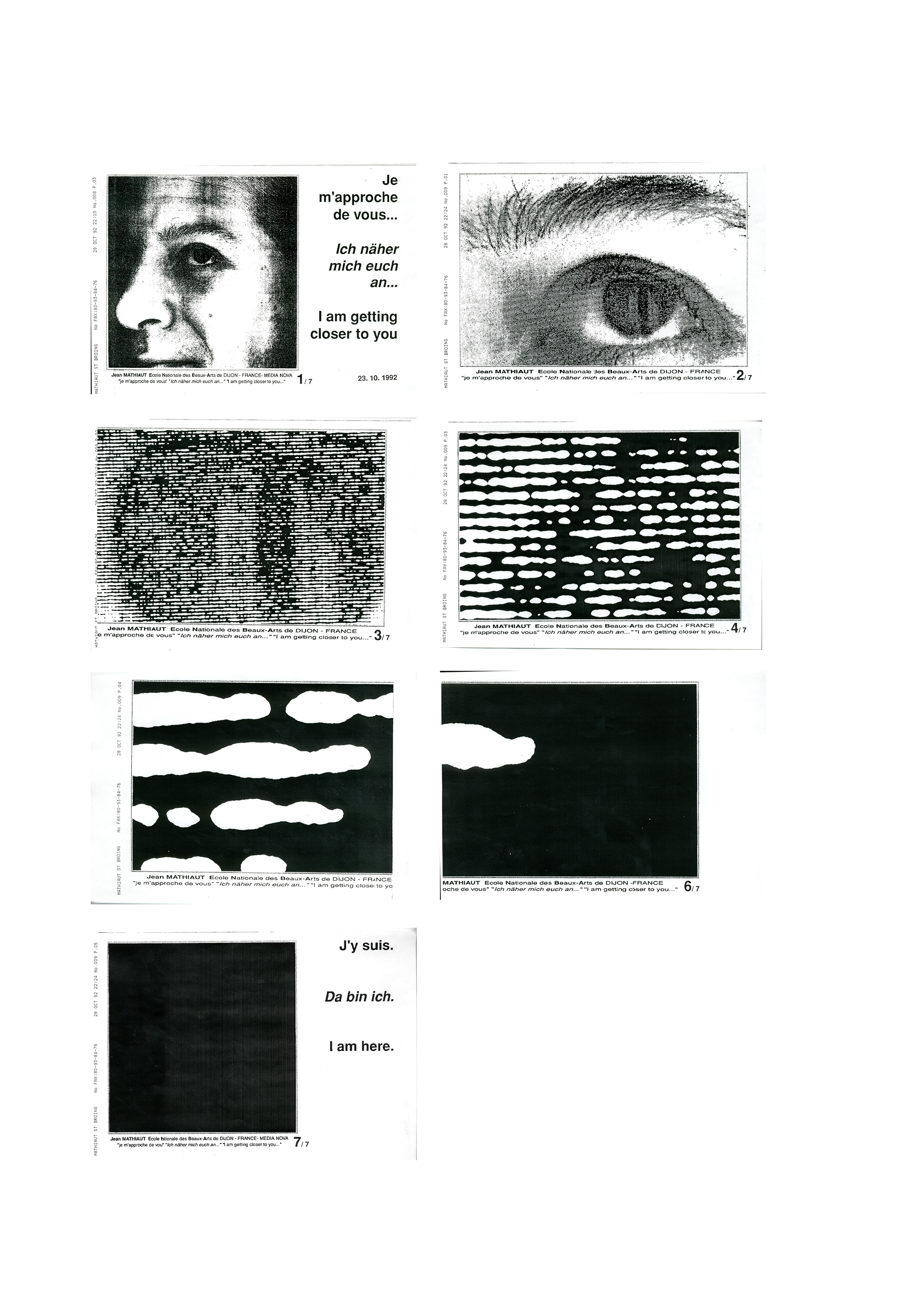

- Visual grammar-noise on the image, determined by the material used, which creates a specific grammar when enlarged or degenerates in consecutive processes. In the pursuit of artistic expression with fax, practitioners developed diverse techniques for image degeneration, which involved enlargements of the image with each transmission, aimed at capturing the visual grammar in the material. A notable example is I am getting closer to you (1988) by the French artist Jean Mathiaut. This fax-based piece is divided into seven parts, each representing a progressive approximation to its own essence. The artwork transcends mere adherence to xerographic grammar, revealing an exploration of the genesis of the image: the dot.

Jesús Pastor and Jacques Fivel did the same in Copy Art, contributing to the exploration of the genesis of the image. In fact, this work was a continuation of the discourse conducted within Copy Art, based on the degenerative process, consisting of uninterrupted copies of copies that have expanded into a world of toner genesis. In an extension, Mathiaut took the fax to engage with the receiver, communicate, serving as a gradual immersion into the constituent matter of the artwork, to the dot of the graphic language.

- The absence of colours and limited grayscale capabilities (Sasson, 1989) in the machine. This gave rise to a new way of producing coloured artworks, relying on the receiver’s machine. The MIDECIANT collection has a number of pieces that deal with the difficulty of creating colour works with fax machines and in which the collaboration and circulation of the images was essential.

Between May 25 and May 27, 1992, the International Museum of Electrography received the pieces of the Fax art Separation Process, Une Première Mondiale artworks. It included the concept of the project by Montreal-based artists Richard Garneau and Jacques Charbonneau, along with the formal resolution of the works created through the receiving faxes and the colour photocopier Canon CLC-1 by artists at MIDE.

These artworks consisted of various pieces: Jacques Charbonneau, from the Centre Copie-Art (Montreal, Canada), sent Le Bicycle #1, while Richard Garneau, from Cégep du Vieux Montréal, sent Autoportrait. In both cases, the process involved sending three faxes with the same image, starting with an original in magenta, another in yellow, and another in cyan tones. Consequently, the grayscale tones in the receiving faxes had various contrasts and values. These received fax images were printed on acetate paper by artists at MIDECIANT, one for each colour. It was when the different acetates were combined that the final colour image appeared, as these images were xeroxed following the instructions and became the final colour work. The sent works were fax art pieces, but the completed work in the receiving space was a colour xerography.

Figure 7. Jean Mathiaut. I am getting closer to you (7 pieces). 1988. Tele-transmission (fax) and xerographic print on paper. 21 x 28.5 cm (each piece). ‘Fax AUDA-Cuenca’. Received: 10/28/1992, n.d. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

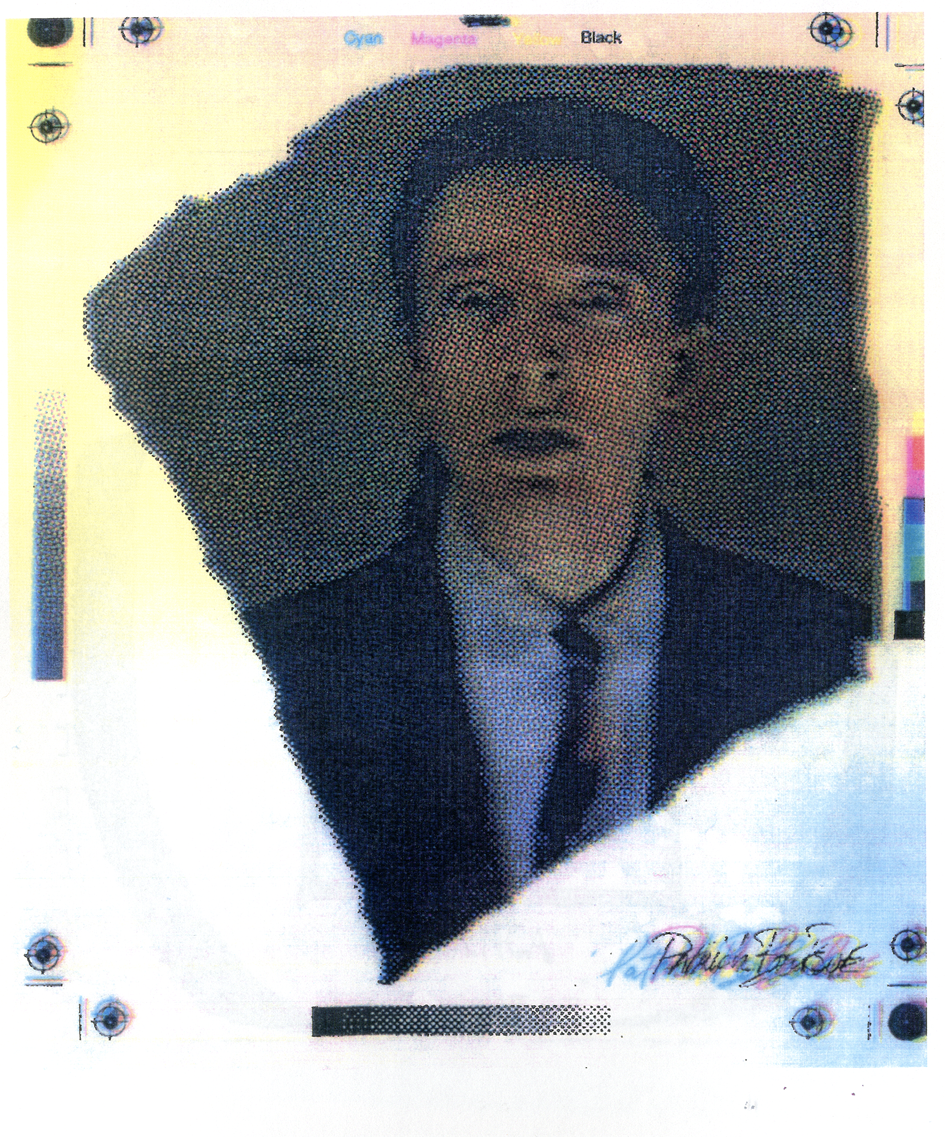

Patrick Bourque followed the same process, but this time he included the four-colour with black in addition to cyan, magenta, and yellow. The images were received at the MIDECIANT Workshop’s fax machine at 15:07, 15:09, 15:10, and 15:10 on October 31, 1992, from the Centre de Recherche en Communication Informatique at the Université du Québec in Montreal.

In these three works, it can be perfectly understood the relevance of the receiver in the process of a Fax Art piece as well as the resulting poor image. The work would not have existed without those at MIDECIANT who made it possible to complete the communicative process and finish the work. The exchange, communicative and circulation of image processes are the base and reason for the Fax Art poor images.

Figure 8. Patrick Bourque. Untitled. 1992. Tele-transmission (fax) and xerographic print on paper. 21 x 29,7 cm. Received: 27/05/1992, 10:48 / 10:49 / 10:51. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

- Temporalization of the image. In some works, the movement of the element on the machine’s process generated a temporality in the image, expressed as displacement and duration. It can be said that there is a chronometric structure in which the passage of time is documented by motion, and its visualization is condensed into a single image. The sweeping time of the fax machine can be contemplated as the exposure time in photography, and it generates a series of errors due to its line-by-line register and printing process. Therefore, it produces the effect of distorting objects based on the direction of movement, and was frequently used with photocopy machines too and in Scan Art.

One example is The Faxed Battery artwork (Figure 5), by Japanese artist Hirotaka Maruyama (Maruhiro), which provides insight into a dynamic collaborative work in progress in two distinct places: Tokyo (sender) and Spain (receiver). It encompasses the conceptualization of the image-process, wherein an object on the glass of a fax machine is displaced to generate a captivating visual effect by rotating a small volt electric battery over the fax scanner’s light, which moved simultaneously. The entire process represents a transformation, where the narrative of time links with the successive encoding and decoding of electric, graphic, and visual registers.

This artwork needed the collaboration between Maruyama, who was creating from his studio in Tokyo, and artists in the workshop of MIDE in Cuenca, Spain to be finished. The artwork was received in two different segments, accompanied by an additional fax piece, in which the artist outlined: “These two images need to be joined together at the center like this”, with an arrow pointing to an image serving as a conceptual sketch. This is an example of the priority of collaboration between artists in different places to have the artwork done in Fax Art. Sometimes, the receiver artist had the role of assembling the different pieces to compose a cohesive piece. Consequently, a graphic language closely assigned with collage and fragmentation emerges, composed of images that have been reproduced, transferred, exchanged or previously enlarged.

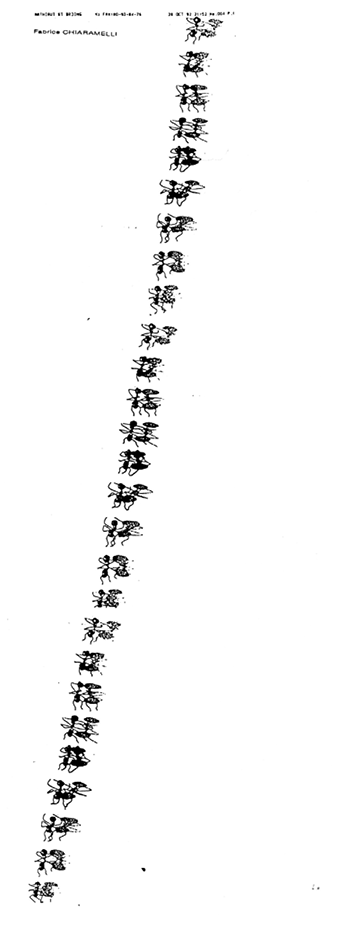

This time is also the temporalization of the communication and collaborative process: the printing instant. Artist Fabrice Chiaramelli employed the technical and formal attributes of the fax machine to create a piece that takes advantage of the communication and collaborative process. In this composition, a sequence of ants traverses the support in a vertical trajectory, enhancing the directional aspect of the fax paper, and performing as an authentic ant animation as the fax receiver began to spit out the paper. This piece also engages with the inherent rhythm of materialization within the receiving apparatus, serving as the impetus behind the emergent animation. A similar dynamic is in the work Pyramid by Cejar, wherein the animation of a pyramid aligns with the establishment of the process with the fax receiver.

Figure 9. Fabrice Chiaramelli. Untitled. 1992. Tele-transmission (fax) and xerographic print on paper. 29 x 31 cm. ‘Fax AUDA-Cuenca’. Received: 28/10/1992, 21:45. MIDE Collection, Cuenca, Spain

- Space-time: the true innovation. However, one of the most profound innovations of fax technology is the space-time relationship in the collaboration between artists located in different places and temporal spaces, yet connected instantly through fax. One of the most noteworthy Fax Art events ever conducted was La Activación de la Superficie Plana, conceived and coordinated by artist Rubén Tortosa in 1992. Tortosa took as a reference point the collection of Cubist works by painter Juan Gris and asked eleven artists all around the world to take Gris as inspiration for the event.

Tortosa suspended 11 fax machines at a height of 2.5 meters from the ground, through which these 11 artists would be sending their works simultaneously from different geographical points, all at the same time in Spain: 8:00 p.m. Madrid time, different ones in the United States and Tokyo.

At 8:00 p.m., the inauguration time in Madrid, the 11 fax machines started to receive the creations in which each artist had been working on in different parts of the planet and in different time zones. Time and space were automatically and instantly connected by a technological medium. Tortosa described it as follows:

It was exciting how the fax machine from Tokyo was emitting on the liquid screen of the fax machine from the next day, or in other words, it was traveling back in time. Here, the circle was perfectly closed on what it meant for those Cubist painters who were inaugurating modern art, what it meant for the artwork to speak of space and time. (Tortosa, 2015)

Figure 10. Rubén Tortosa. La Activación de la Superficie Plana. 1992. Participants: Calduch (Valencia, Spain), Pastor (Salamanca, Spain), Hockney (Los Angeles, USA), Sheridan (Evanston, USA), Cano (Madrid, Spain), Bruscky (Recife, Brazil), Muntadas and Rabascall (Paris, France), Olbrich (Kassel, Germany), Maruyama (Tokyo, Japan), Levine (New York, USA), Munari (Milan, Italy). ‘Variaciones en Gris’. Centro Cultural de la Villa, Madrid, Spain

Additionally, behind this installation of the 11 fax machines, there were other large-format fax works – assembled using collage techniques – that each artist had sent in advance and that, following their instructions, had been adjusted and assembled by Tortosa.

All the limitations and characteristics of fax, along with the essential collaboration it required, gave rise to the artistic processes associated with the medium and its graphic qualities. These are defined by the degradation and loss of visual information due to the distance and spatial constraints, texturization and visual noise, and the deterioration of images caused by conservation issues with fax materials. These factors shaped the visual characteristics of fax images, ultimately influencing their artistic value, too.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

The exploration of Fax Art reveals a distinctive graphic language shaped by the media specificity and the collaborative processes. The fax machine imposed new conditions, demanding immediacy, transmission, circulation and collaboration. The ways in which artists employed techniques such as fragmentation, enlargement, movement and layering to transform fax limitations into aesthetic strengths, as well as the error and impoverished images owing to the tele-transmission technology. Through those innovative practices, such as fragmentation and temporalization, artists navigated the constraints of the fax machine, fostering a unique graphic language that embraces error and chance. Artists incorporated them, transforming these challenges into opportunities for creative expression. It is crucial to emphasize how artists embraced the constraints and features of the fax machine to convey a sense of rawness, impoverishment, authenticity, and immediacy in their artworks, making them unique.

Thus, the role of transmission and collaboration between artists in the configuration of other modes of production and circulation of works, other narratives for artistic practices, is highlighted thanks to the transgression of the fax. The resulting artworks are not mere representations but dynamic dialogues between sender and receiver, highlighting the meaning of collaboration in the process. This collaborative framework emphasized the interdependence of artists across geographical and temporal boundaries, enriching the creation and interpretation of fax art. It not only disrupted spatial continuity but also managed to achieve a fusion of instantaneous time in the creative process. The fax machine laid the foundation for the Telepresence Art that began to develop in the early nineties, strongly influenced by Eduardo Kac and Ken Goldbeg (Grau, 2007). Additionally, it was a precursor to the Internet in Media Art because artists creatively utilized the first tool that enabled the transmission of data and image in real-time, “Another instrument of play and imprint”5 (González, 1992, n.p.).

Significantly, events like La Activación de la Superficie Plana exemplify how technology can bridge distances, allowing multiple artists to engage simultaneously in a shared creative experience. Ultimately, the fusion of technology and collaboration not only enhances artistic expression but also redefines our understanding of space and time within the realm of contemporary art. The exploration of fax images serves as a tribute to the innovative potential of artistic practices that emerge from technological limitations and the importance of collaborative efforts in the creative process.

In conclusion, the discussion underscores the central role of collaboration in the evolution and dissemination of Fax Art. Artists had utilized these tools to establish networks of collaboration and production. The advent of distributed modes of production and circulation through fax technology had not only democratized artistic expression but also fostered a rich ecosystem of creative exchanges and innovation between artists. As artists continued to explore the possibilities afforded by collaborative approaches and decentralized distribution channels, the fax remained a potent tool for constructing alternative narratives and challenging conventional artistic practices and parameters. This, the collaborative ethos inherent in fax art underscores its enduring significance as a dynamic form of artistic expression and cultural exchange.

References

Alcalá, J. R. (1985). El “Copy Art” o Arte de la Copia; la Copiadora como Instrumento para la Producción de Imágenes Plásticas Contemporáneas. Bachelor’s Thesis. Director: Facundo Tomás Ferré. Valencia: Faculty of Fine Arts, Polytechnic University of Valencia.

Alcalá, J. R. & Escribano, B. (2016). International Museum of Electrography. Cuenca Center for Innovation in Art and New Technologies. A: Alcalá, José Ramón y Jarque, Vicente. CAAC Cuenca, Cuenca Center for Art, Archives and Collections: Cuenca - the city and its culture (pp. 469-652). Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

Benjamin, W. (1969). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Schocken Books [Originally published in German as “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit” in 1935].

Bleus, G. (1994). “…Telecopying in the electronic netland...”. A: Urbons, Klaus. Elektrografie. Analoge und digitale B. (pp. 40-44). DuMont.

Brodrecht, G. (1985). Prologue/Epilogue. A: AA.VV. (1986). Global-Art-Fusion. Art-Fusion-Edition. n/p.

Brunet-Weinmann, M. & Mühleck, G. (1987). Medium Photocopy: Canadian and German Copygraphy. Transatlantic Press. Book of the exhibition at Gelsenkirchen Rolf Glasmeter Studio, 3/01 - 28/01/1986; at the Museum für Fotokopie in Mülheim, 5/01 - 28/01/1986; at Pforzheim Brötzinger Art Gallery, 31/01 - 28/02/1986, and at Stuttgart Künstlerhaus, 11/03 - 26/03/1986).

Coopersmith, J. (2015). Faxed. The Rise and Fall of the Fax Machine. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Déotte, J. L. (2013). La época de los aparatos. Adriana Hidalgo editora.

Di Lorenzo, R. (2004). Arte da lontano. Dalla Mail Art ai telefoni cellulari. Undergraduate Thesis. Director: Antonella Sbrilli. Roma: Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia. Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”.

Eichhorn, K. (2016). Adjusted Margin. Xerography, Art and Activism in the late twentieth century. The MIT Press.

Elsaesser, T. (2016). Media archaeology as symptom. New Review of Film and Television Studies, 14:2, pp. 181-215. [online] Available on: https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2016.1146858

Escribano, B. (2017). Copy Art Histories: The emergence of the photocopy machine in the 20th century art and its role as Historial Media Art. Tendencies and thematic cartography of Copy Art. Doctoral Thesis. University of Castilla-La Mancha.

Escribano, B. (Coord.) (2016). Procesos: El Artista y la Máquina. Reflexiones en torno al Media Art histórico. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

Firpo, P., Alexander, L., & Katayanagi, C. (1978). Copy art: The first complete guide to the copy machine. Richard Marek Publishers.

Flusser, V. (1983). Hacia una filosofía de la fotografía. Sigma. 1990 [Publicated as Für eine Philosophie der Photographie].

González, M. (1992). Network Generative Systems Spain. A: AA.VV. (1993). I Muestra Internacional Fax Art. Colecciones del MIDECIANT.

Grau, O. (ed.) (2007). Media Art Histories. The MIT Press.

Huhtamo, E., & Parikka, J. (eds.) (2011). Media Archaeology. Approaches, Applications and Implications. University of California Press.

Kac, E. (2005). Telepresence & Bio Art: Networking Humans, Rabbits & Robots. The University of Michigan Press.

Kierspel, J. (2016). Interview conducted by the author with the artist Jürgen Kierspel on October 16, 2016, via email.

Kirkpatrick, D., & Sheridan, S. L. (2009). The art of Sonia Landy Sheridan. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College.

McCray, M. (1979). Electroworks. International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House.

Ñíguez, F. (1986). La fotocopiadora: evolución, descripción y utilización de la electrofotografía con fines expresivos. Undergraduate Thesis. Supervisor: Facundo Tomás Ferré. Valencia: Facultad de Bellas Artes de Valencia. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia.

Raap, J. (1991). New aesthetics. A: Pellini, Pietro y Berbesz, Yola. Copy Art Fax Aktion. Hannover: CeBIT’91. n/p

Sasson, D. (1989). L’Arte Schiacciabottone. Assessorato Istruzione e Cultura Amministrazione Provinciale Siena.

Steinberg, L. (1972). Reflections on the State of Criticism. Artforum, pp. 37-49.

Tortosa, R. (2015). I Ciclo de Videoconferencias MIDE25. Cuenca [online]. Available on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0gcnUcFooe0

Zielinski, S. (2006). Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means. The MIT Press.

Notas

1. The term "xerography" refers to the printing process that employs dry electrostatics for graphic reproduction, which was invented on October 22, 1938, by Chester F. Carlson. The company that commercialized it was The Haloid Company (Xerox after that), and in 1959, it launched the Xerox 914, which created black-and-white copies on regular paper in a simple and fast manner. At the beginning of the 1980s, with the emergence of other international companies involved in the development of photocopiers (which had been delayed due to Xerox's monopoly), many considered that this term was no longer appropriate. However, from an artistic perspective, and considering the appearance of digital models, "xerography" can be defined as the technique used by artistic practices that employ the techniques and processes derived from the use of the photocopy machine. It can be either analog, referring to the use of dry electrostatics for graphic reproduction, or digital, where the record is converted into numerical binary data, 0 and 1, which can be edited before being returned to the toner material via the semiconductor laser (Escribano, 2017). Indeed, other terms associated with the photocopier were considered less precise, as “[…] if ‘xerography’ is too limiting, then inversely, ‘electrography’ and ‘reprography’ are terms much too broad, open to techniques that have nothing to do with photocopying. ‘Electrophotography,’ a term used by the inventor Chester F. Carlson, was not practical due to its length” (Brunet-Weinmann & Mühleck, 1987, p. 33).

2. In 1979, curator Marilyn McCray recognized two of the three artistic generations in the catalog text of the exhibition Electroworks, referring to them as "First Generation" or "Generation One" (McCray, 1979, p. 11) and "Second Generation" or "Generation Two" (McCray, 1979, p. 24). Later, artist and researcher José Ramón Alcalá, in his Bachelor's thesis titled El ‘Copy Art’ o Arte de la Copia; la Copiadora como Instrumento para la Producción de Imágenes Plásticas Contemporáneas (1985), specifically distinguished three generations, including the one they themselves were living as artists between 1985 and 1995. This fact was analyzed and confirmed in a study conducted by Beatriz Escribano, and concluded in 2017.

3. “[…] sia ad una situazione di incomunicabilità provocata dai ‘media caldi’, che alle limitazioni imposte dal mercato culturale.” (Author’s translation)

4. “una auténtica mesa de trabajo” (Author’s translation)

5. “Otro instrumento de juego y de huella” (Author’s translation)