Contemporary Archeology

A crisis works like turbulence or a brake, decelerating our activities. Slowing down a speeding machine has an unpleasant effect; a shock, a collision even, with unwanted obstacles that, even though they were already on the road, have so far been easy to avoid.

From my point of view, emergency braking belongs to the past. The time has now come to look at the static elements around us. A moment to stop and dig up historical remains. To study these static components and analyze their essence. Phenomena from ancient times are coming back from the dead like ghosts and demanding to be put back together. So were they approved by history too quickly and inadequately absorbed before being put on a shelf in the archives? One thing is for certain: many of us are becoming archeologists of past events. Most probably in order to “organize the future”. Situations and events are whirling around and ending up back at the top, in the present. This is certainly the case in Poland. Why do we need to repeat lessons from the past? Perhaps we made mistakes that prevent us from declaring things ‘settled’. The fall of communism in Eastern Europe at the end of the 20th century, which was called a historic victory, a political transformation and a change in favor of individual freedom, now seems to be just an episode, a short period of leave granted with the consent of the warden, for fun, almost. Could the moral havoc and mayhem around identity not allow for independence? Is freedom without education just a harness?

In an era when nationalist and even fascist movements are seeing a revival, in times when populist views or an admiration for communist ideology are becoming increasingly popular, a return to global lessons seems inevitable. According to the accepted rules, people make states, and above all democracies. Recent times, however, have shown that rules can be juggled around and states manipulated. And that democracy can even be stolen, and with the consent of its citizens. However, it can be very misleading to form hasty opinions of particular nationalities based on what happens in a given country. Prejudices deepen until – often suddenly and surprisingly – the changes start affecting us directly. I would therefore advise against reading this text from the perspective of my faraway province. Watching from a distance will only lower your guard; from there, it only takes a fraction of a second and you will be waking up to a different reality.

The ritual of cleansing the past that I will be discussing in this article – this shell dug up from the ground and examined anew – has become, for me, a gesture that allows me to maintain a certain ‘stability to the present’. This is why I am keen to look at artistic activities touching upon issues that bring back themes from the past. An example may be the work of Nicholas Galanin (plates 1–3) and his excavations on the island of Kakadu. The artist “‘uncovers’ or ‘excavates’ the shadow cast by the Captain Cook statue. The work rests between a possible past or future burial, a presence through absence of an object that today very much still functions as a celebration of colonial heroics”. (The 22nd Biennale of Sydney, 2020)

Plates 1–3. / Nicholas Galanin (2020) Shadow on the Land, an Excavation and Bush Burial. Installation view for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), Cockatoo Island. Image: Alex Robinson; Courtesy of the artist.

Going through the archive, and even ‘archaeological research’ on old concepts, also accompany my artistic work, albeit on a different level. Digging up old works and re-examining past projects is like going full circle and also being surprised by reality, which itself requires repeat performances and the digging up of activities buried in the past.

Rituals of power

In 2018, I was invited to show a series of my archival works entitled Confessionals at a group exhibition called Between Salvation and the Constitution (plate 4). The project was run by the BWA Warszawa gallery, which had just moved to a new location in the center of the Polish capital. BWA Warszawa is a private art gallery, whose exhibitions very often reflect the views of the owners. One of the founders of the gallery is a leading activist and member of the Green Party.

The curatorial idea for creating the exhibition was the political situation in my country and the social emotions related to the observance of the rule of law and the separation of the State and Church. Of relevance was the fact that in 2018, Poland was celebrating the 100th anniversary of its independence. So it was an exceptional year. However, the catalyst for the exhibition was a short, but significant, statement made by a representative of the Church authorities, which was widely reported in the media, during the celebration of one of Poland’s most important religious holidays. Journalist and publicist Piotr Sarzyński commented on it and the reaction of the BWA Warszawa gallery thus: “It is highly unusual for exhibitions to respond so directly and quickly to events in everyday life. This exhibition is a form of artistic commentary on Archbishop Wacław Depo’s notorious sermon, in which (...) he lamented that in Poland, the Constitution precedes the Gospel. The title of the exhibition is also a play on words, because the gallery’s new location is between Plac Konstytucji [Constitution Square] and Plac Zbawiciela [Salvation Square]”.1 One might think that the coincidence of the change of address contributed to a revision in the relationship of “secular and ecclesiastical power, politics and faith, law and ecclesiastical law”.2

Of course, the real reason why artists were invited to speak out was more serious. The curators recognized that the upheaval from the changes that had begun to take place in Polish political and social consciousness, which had initially taken place imperceptibly, required artists to join the debate, although they would be reluctant to view politics in the context of their work. It was surprising, however, that similar problems were raised in Polish socially-engaged art as far back as three decades ago.

Plate 4. / Excerpts from the exhibition Między Zbawieniem a Konstytucją / Between Salvation and the Constitution (2018) BWA Warszawa (Poland); image: Bartek Górka; Courtesy of the BWA Warszawa Gallery .

In the early 1990s, comments and speeches made by artists criticizing the socio-economic and political situation constituted a clear trend in Polish art, defined by media expert Ryszard W. Kluszczyński3 as the trend of critical art. Leading art theorists and curators following events after the collapse of the Iron Curtain4 included Piotr Piotrowski and Izabela Kowalczyk. Piotr Piotrowski’s works, such as In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945–19895 and Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe6 are examples of the most significant analyses to be found in the literature on the changes in artistic culture in Central and Eastern Europe. The author focuses on a range of topics including art and politics, artistic topography, gender, nationalism, censorship, memory, and the concept of new museology, which he discussed in more depth in another book entitled The Critical Museum.7 An interesting point of reference proposed by Piotr Piotrowski is the perception of the past and the heritage that it always carries with it as a traumatic experience, and the distinctions in further analysis can only be divided into those classified as traumatophobia or traumatophilia. By applying the suggested filter, the analysis of cultural phenomena in Eastern Europe will undoubtedly be deepened and the nuances easier to read.

However, if we want to discuss the artists of that period, it is enough to mention the profiles written by Izabela Kowalczyk in the publication accompanying the 2002 exhibition Dangerous liaisons between art and the body8 or the artists showcased by Artur Żmijewski in his study entitled Trembling bodies. Conversations with artists.9 The authors transcribed hours of conversations with Polish artists, including Paweł Althamer, Anna Baugmart, Grzegorz Kowalski, Zofia Kulik, Zbigniew Libera, Joanna Rajkowska and Katarzyna Kozyra, who in 1999 received an honorary mention at the 48th International Art Biennale, Venice for her work Men’s Steam Room. The interviews reveal radical artistic attitudes towards consumerism, but also the problem of identity and corporeality, along with entanglement in power structures, political and religious contexts. In her review of Żmijewski’s book, art historian Dorota Jarecka points out that “this art is unpopular with the authorities. The more organized political movements are, the tighter their ranks become, the more discipline flourishes in them, the more (...) the powers that be hate art. Probably because its essence, its sense, above all other values, is absolute freedom. To put it another way: art is an experiment that you keep on starting from scratch, trying to find out how much freedom you can carve out of your life. That’s why this art has so many points of contact – with society, politics and religion. It does not take place in artistic space, but in real space”.10

Most of the critical art exhibitions at that time provoked loud discussions and even radical reactions on the part of the authorities, which were often nothing more than scandalous abuses against artists. An example is the accusation against the young artist Dorota Nieznalska of offending religious feelings, which followed the showing of her installation Passion (plate 5) as part of the New Works exhibition shown at the Wyspa Gallery in Gdańsk. In 2003, she was sentenced to six months’ community service. After an appeal, there was a second trial and she was finally acquitted, but not until 2010.

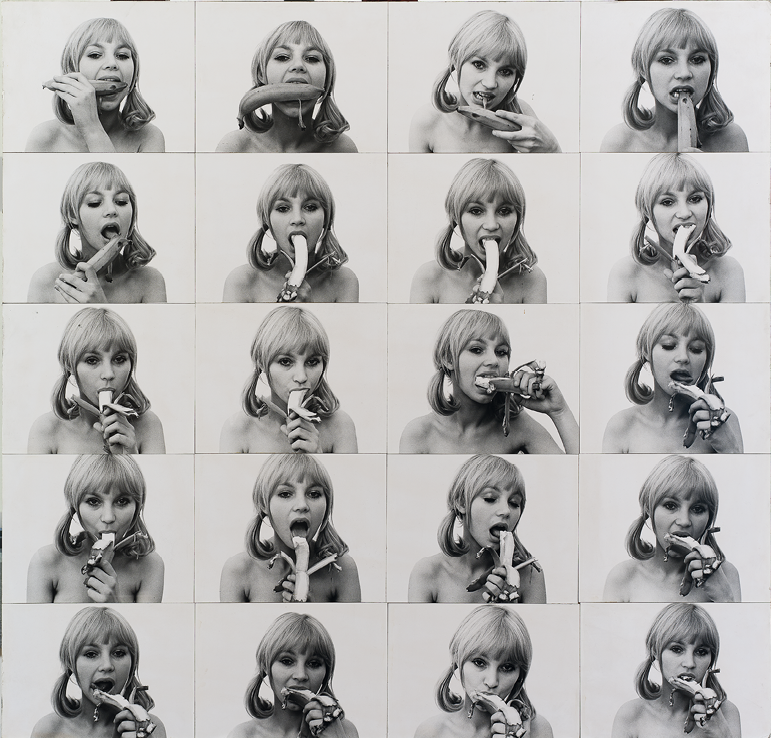

The founder of the Wyspa Gallery in Gdańsk, Grzegorz Klaman, was part of the critical art movement. His works were symbolically mentioned during the above-mentioned exhibition at BWA Warszawa. Significantly, after the showing of Dorota Nieznalska’s Passion, the Rector of the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk ordered that the Wyspa Gallery be closed. While the decision was harsh, it was treated as a one-off, unprecedented incident. However, as events more recently have shown, the real toll taken by the systemic closure of institutions in Poland, the replacing of the management, or the establishment of new institutions with a particular agenda was yet to come. The past few years have shown how much we, as a society, were unprepared for these changes, and how astonished we were at the multiple decisions to transform entire institutional structures that had functioned for years. Most noticeable from afar are the changes to the models of the Polish Institutes operating worldwide. Previously, the diplomatic priority was to “create the belief that contemporary Polish culture is attractive”.11 Programs were designed to make residents from individual countries want to come to events and thereby become interested in Poland. Spaniards, for example, would always go to Polish jazz concerts in large numbers, and the recent exhibition of Andrzej Wróblewski’s paintings at the Queen Sofia Art Center at the National Museum in Madrid in 2015 drew over 120,000 visitors, a far greater number than had visited the exhibition when it was shown in Poland.12 From 2016, however, the objectives of the Polish Institutes were redefined. There was a departure from projects for international audiences and, instead, a focus on links with the Polish diaspora. The main goals were to promote the so-called Polish raison d’état, the Polish historical narrative and to demonstrate that Poland is a traditional nation with conservative values. There were layoffs and surprising nominations to cultural institutions. In 2016, Paweł Potorczyn, who for many years had been responsible for cultural diplomacy at the Adam Mickiewicz Institute operating worldwide, was dismissed by the Polish deputy prime minister during his term of office, for no reason. No substantive or financial allegations were ever made.13 Another high-profile dismissal was that of the director of the Silesian Museum in Katowice, Alicja Knast, and although the case had many twists and turns, the social loss is irreparable. Anyway, shortly after being removed from her position, she was appointed to run the National Gallery in Prague, Czechia, and left Poland. It is worth recalling that Alicja Knast is a multiple award winner: “She has been recognized by the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Association of Museums in the Netherlands and the London Metropolitan University”.14 In Poland, the number of nominations to management positions at cultural institutions without the requisite transparent application process has also increased recently, and the appointees are increasingly lacking relevant qualifications. Artists’ work is also being censored, the most notorious example being the decision of the director of the National Museum in Warsaw, Jerzy Miziołek, to remove the works of the artists Natalia LL, Katarzyna Kozyra, and the Sędzia Główny Group from the 20th and 21st Century Gallery collection15. Of course, there were instant social reactions and public demonstrations consisting in the ostentatious consumption of bananas in public places, or in the media, which was a reference to the works of Natalia LL dating from the 1970s (sic!), Consumer Art (plate 6). These were a mass irreverent reaction to the absurd decisions to appoint unqualified people to important positions in cultural institutions. If we examine the artistic activities from the period of critical art in Poland, which are often based on provocation and playing with moral norms, entering the social fabric and stimulating a discussion, numerous points of contact with the current atmosphere in Polish culture and art can be seen. So it has become a big issue again. The only difference is that the sender of these provocations has changed. Now artists are reacting to the shocking actions of the authorities.

Plate 5. /Dorota Nieznalska Pasja (2001) at the New Works exhibition, Wyspa Gallery, Gdańsk (Poland). Photograph from the opening of the exhibition by Dorota Nieznalska, image: Sławomir Mielnik / Agencja Gazeta; Courtesy of Gazeta Wyborcza.

Plate 6. / Natalia LL, Sztuka konsumpcyjna. Faza – XI / Consumer Art. Phase – XI © Fundacja ZW and Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź.

Exhibition or protest?

One of the decisions taken by the creators of the Between Salvation and the Constitution exhibition was to abandon accompanying curatorial descriptors. However, the public had access to press articles commenting on the statement by the church hierarchy. One title read: “A country Where the Gospel takes precedence over the constitution. Welcome to the Polish Catholic Republic, where the law must come from God”.16 In this way, the Between Salvation and the Constitution exhibition was thrown into the crucible of social debate and handed over to the public along with press articles and the current political context. The event resembled more a protest banner than one of the many exhibitions that had been held in the gallery to that point. The voice of the art world made it clear that the time had come to react, and cultural institutions could no longer operate within the accepted frameworks. One could say that this was another moment of revision to the institutional structures in the art world. The old question about the ‘new museology’, raised by Piotr Piotrowski in his book Muzeum krytyczne [The Critical Museum], returned. Basing his work on Carol Duncan’s Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums,17 Piotrowski emphasizes that the museum is “an institution between the past and the future (...) a place where a given community develops the values of its own identity, but also (...) a place of power. The role of citizens is (...) not so much to leave passive members of a hierarchical society as to take away the power to control the rituals that shape these structures. Only then will we be able to say that the democratic historical processes which underpinned the creation of a public museum are being fulfilled”.18 As Jean Clair wrote in Malaise dans les Musées: “One day we will have to try to explain why the two most architecturally surprising museums of contemporary art in recent years have taken the form of sea monsters washed up on the shores: the Guggenheim in New York, a giant ammonite writhing between East River and Central Park, and the Guggenheim in Bilbao, a crab shell on the other side of the same ocean. These two mollusks are just empty shells, dead and motionless. The novelty of the Guggenheim system was the creation of shellfish museums on both sides of the Atlantic, museums devoid of the delicate and tasty flesh of the collections they were to protect. These museums are fossils of a culture that – like the sea – seems to be retreating from everywhere”.19 In this context, I hope that the decisions of small cultural centers in various parts of the world will contribute to reflection on the lost value of the idea of exhibiting art. As Jean Clair goes on to say, “Malraux invented a museum of the imagination that the English called a museum without walls”.20 Perhaps it would be worth refurbishing these walls to redecorate the apartment, not a museum, of art.

Wash and go

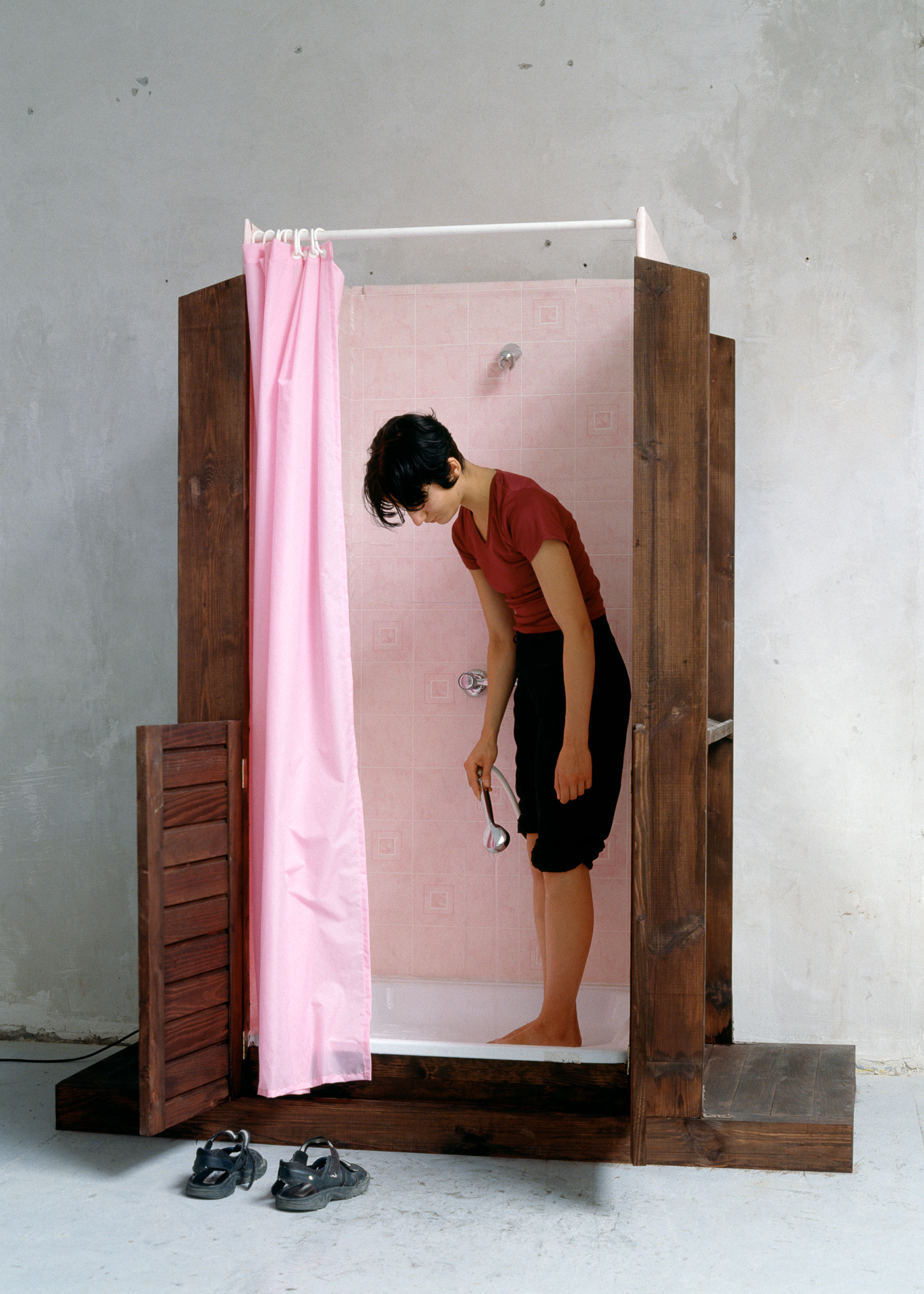

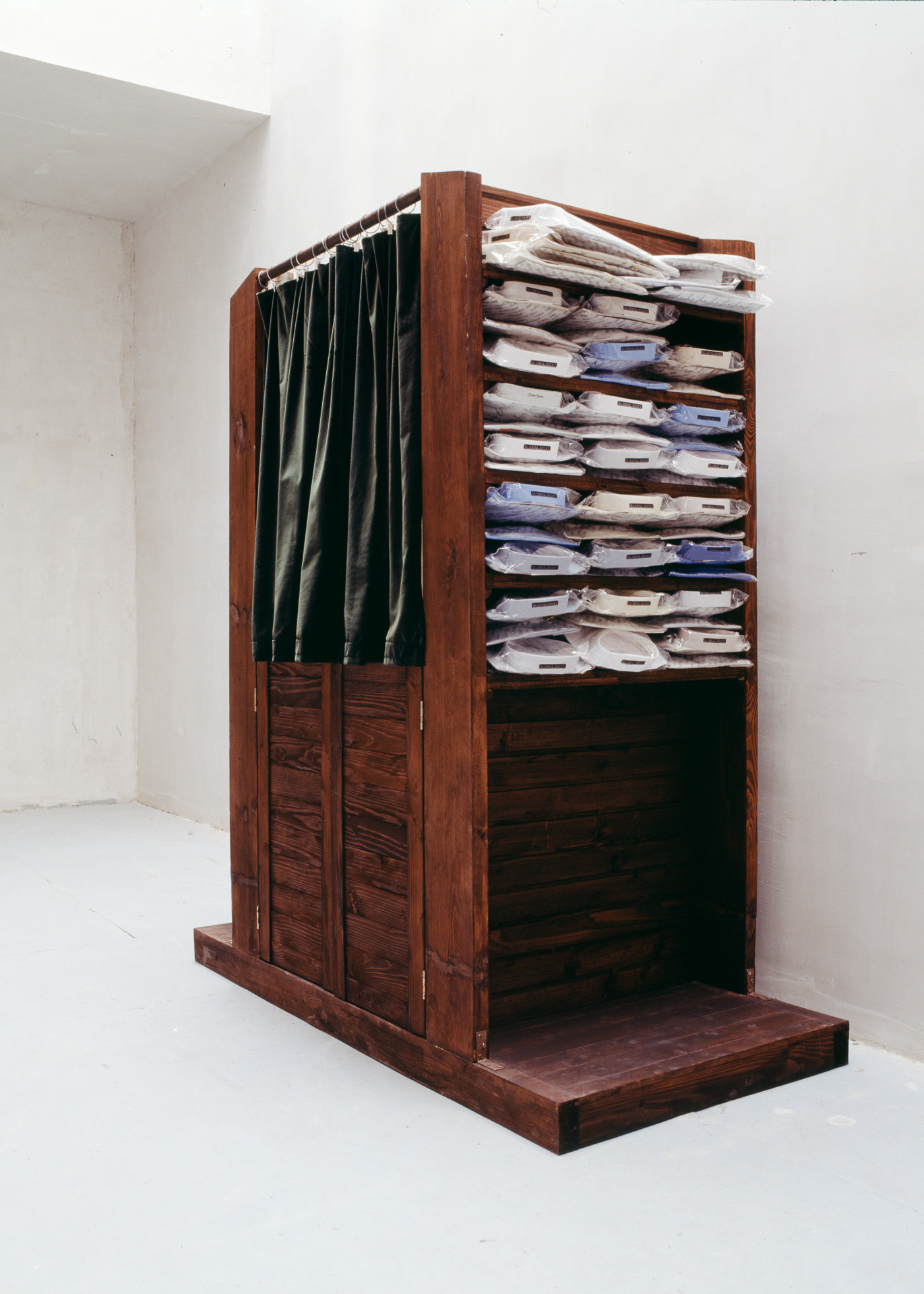

At the BWA Warszawa exhibition, I showed photographic documentation of objects that I had made many years previously (plate 7). The works have been in the archives for a very long time and I did not think that they would ever be contemporary again and comment on the current situation in Poland. “In a series of works created in 2000, we find (...) a striking resemblance to confessionals found in churches (plates 8–11). They take their name from the Latin word confessionale, which means confession of faith, religion or confession of sin. The confessional box is a special place, because it is an intimate space in which the person who opens up their most private experiences kneels not only before the God to whom they confess, but also, and perhaps above all, comes into contact with the institution. So (...) we are at a crucial point of intersection between the private and public space”,21 wrote Marek Wasilewski, art critic, referring to the objects in the Confessionals series.

Taking each work separately, on the other hand, he recalled: “The Confashional is an object that is a cross between a changing room and a confessional box. You can go inside and try on one of the shirts that the artist has hung above the kneeler. Another work, entitled Wash and Go, under the guise of a confessional hides a shower cubicle that can be used during the exhibition. What we have here is an ironic play on meanings, because the confession is also a symbolic cleansing, a purification or renewal, or a new, clean garment. The relationship of these objects to the confessional can also be found in terms of measurement, because they are, after all, made to measure, and assume that person’s isolation. Another object in this series, The Interior Layout (plates 12–13), is a confessional turned inside out, with the kneelers for the faithful inside, and the potential confessor outside. This simple trick creates no end of new meanings (…)”.22

Plate 7. / Anna Klimczak (2000) from the series Confessionals; from the left: Wash and Go, Konfekcjonał (Confashional), International Art Center Inner Spaces, Poznań (Poland); image: Bernard Francois.

Plates 8–11. / Anna Klimczak (2000) Konfekcjonał (Confashional) and Wash and Go, Międzynarodowy Festiwal Sztuk Wizualnych Inner Spaces Multimedia, International Art Center Inner Spaces, Poznań (Poland); images: Bernard Francois.

Plate 12-13. / Anna Klimczak (2001) Układ wewnętrzny (The inner arrangement), 1 Biennale Rybie Oko, (1st Biennale Fish Eye), Baltic Gallery of Contemporary Art, Słupsk (Poland).

Plate 14. / Anna Klimczak (2001) Układ przenośny (The portable arrangement) and Układ wewnętrzny (The inner arrangement), 1 Biennale Rybie Oko, (1st Biennale Fish Eye), Baltic Gallery of Contemporary Art, Słupsk (Poland).

Graduates on notice

The series of works entitled Confessionals were made shortly after I graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań (now the University of the Arts). In the work, it is easy to decode the echoes of my education at the conceptual drawing studio of Professor Jarosław Kozłowski, where students created installations or artistic objects, among other things. The works from this series were created as a result of free play with form and meanings rooted in consciousness. The transformation of an object that had a specific symbolism and fulfilled the functions assigned to it corresponded to spontaneous research, which was based on manipulating concepts, and changing functions in such a way as to lead back to the starting point. And ask the viewer: ‘What do we know about a given object and what is that knowledge?’ Playing with form in 2000 turned out to be reality almost twenty years later. Unfortunately, the current context has made the work unpleasantly serious rather than ironic. On this occasion, it is worth recalling that a large group of artists left the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań; their activities have been tried to be classified as the Poznań School of Installation. The term was used and disseminated in the 1990s by the Polish art critic and co-founder of the well-known Raster gallery23, Łukasz Gorczyca, who evaluated the projects made by Poznań graduates not so much critically, but mockingly, even. However, like many phenomena analyzed in this article, this formulation has also come full circle and has been subject to review. In 2014, the ArtStations Foundation gallery in Poznań showed an exhibition entitled Instalatorzy [Installers] curated by Mateusz Bieczyński, which encouraged us to examine artists from this circle, in particular the youngest generation of artists including Monika Sosnowska (plate 15) and Wojciech Bąkowski, artists with an established position in the field of contemporary art. What is an installation? 24 wonders Diana Wasilewska in the text on the exhibition, “Is it actually a genre? If so, then it is confused, because of its highly fluid and open borders. A medium? Probably not necessarily, if we treat it broadly, and not as Claire Bishop wants, with a clear link to the issue of the presence of the viewer. In the 1990s, the installation was one of the decade’s hallmarks, and thus a tool of polemics, more often even rhetorical than descriptive or classifying. Today, this concept has not only been dumbed down but has also widened its limits to the maximum (…)”.25

The absurdities of reality

In one of my very early artistic statements, I wondered, ‘Is there any comprehensible name for the reality we live in?’ The question seems absurd, but so far it has been the key to analyzing my artistic activities. The trail of my searches – as I wrote in my dissertation Art versus Institutions – often starts with the breaking up and disordered assembly of generally accepted concepts and contents. I try to combine several or even several layers of meaning in one work. At that point in time, difficulties in finding answers were created by formal puzzles, which caused the multiplication, blurring and permeation of concepts, and which resulted in difficulties in classification.26 I have always understood that undermining what is apparently obvious and replacing the matching mental elements of a puzzle27 are the essence of creativity. According to one of my favorite writers, Witold Gombrowicz, “Art (...) should destroy reality, break it down into elements, and from them build new absurd worlds – in this freedom, law is hidden, violating sense makes sense, in destroying our external sense, madness introduces us to our internal sense”.28 When I reflect on these observations, I have the impression that for some time they have been not only an act of artistic searching, but a part of my reality in which I live and function. And the madness, which played the role of artistic catalyst in the creative act, has become the participation of institutions that should ensure law and order.

Flags, or coloured attributes of power

Coming back to the exhibition Between Salvation and the Constitution, it is worth mentioning that the curators also invited a newly established collective called 100 Flags (plates 16–17) to participate in the project, whose aim was to remind the public of the 100th anniversary of Polish women’s right to vote.

Plate 15. /Installation view: Monika Sosnowska, 1:1, 2007/2008, steel construction, installation at Schaulager: 19’ 8” x 24’ 11” x 48’ 7”, construction produced in 2007 by Zacheta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, Courtesy Foksal Gallery Foundation, Galerie Gisela Capitain, kurimanzutto, The Modern Institute, exhibition „Andrea Zittel, Monika Sosnowska. 1:1“, 26 April – 21 September 2008, Schaulager® Münchenstein/Basel, © Monika Sosnowska, photo: Tom Bisig, Basel.

As the founders write, “The background to the 100 Flags idea was the rather interesting social situation in 2018, when the number of celebrations, marches, publications, exhibitions, reconstructions and other initiatives concerning the centenary of our regaining independence completely took over the public sphere. All this was treated with great seriousness, dominated by the historical-national narrative and, law-oriented, historical policy. The catchphrase a hundred for a hundred became the perfect slogan for getting all kinds of funding”.29

Plate 16. / 100 Flags for the Centenary of Polish Women’s Right to Vote (the 100 Flags project main event), to which everyone was invited to take part; Warsaw, 11.24.2018; image: Rafał Żwirek; Courtesy of the 100 Flag Collective.

Plate 17. / View of the building to which the BWA Warszawa gallery moved in 2018, on ul. Marszałkowska in Warsaw (Poland) – the section between Plac Konstytucji (Constitution Square) and Plac Zbawiciela (Salvation Square). Image taken on November11 2018 during the National Independence Day march. Visible on the balcony is the spontaneous performance by the 100 Flags Collective. The event accompanied the 100 Flags for the Centenary of Polish Women’s Right to Vote march. A video of this event was then shown at the Between Salvation and the Constitution exhibition; image: Rafał Żwirek; Courtesy of the 100 Flag Collective.

This was an important part of the Between Salvation and the Constitution project, as the gallery became a rallying point. I would not call the 100 Flags group a performance, but an invasion of protesters from the street into the institution, and the Polish white-and-red state flag became a part of the discussion. This thread was also visible in the exhibition. As Piotr Sarzyński notes: “The exhibition is both opened and closed by a work that is not new, but highly symbolic for the subject and well remembered in this context: one of Grzegorz Klaman’s flags (plate 18), in which not two but three colors are combined (in different configurations, too): white, red and black. As a warning, with a small dose of hope”.30

The manipulation of hallmarks and approved communication codes always brings to mind intense or disturbing signals. When artists revise socially ingrained symbols, they usually perceive disruptions in how rules and norms are functioning. I undoubtedly tried to use this kind of irritation in the Confessionals series. Overlapping semantic layers led to a glitch in the formal and semantic sense. The objects were hemmed in the same way as the flags from the 100 Flags project (Plate 19.).

Plate 18. / Grzegorz Klaman (2001) Flaga dla III RP (Flag for the 3rd Polish Republic), exhibited at Between Salvation and the Constitution, BWA Warszawa, 2018; Image: Bartek Górka; Courtesy of the BWA Warszawa Gallery.

Plate 19. / The100 Flags project (November 2020), commemorative photo taken at the BWA Warszawa gallery following the collective’s spontaneous performance, along with invited guests. The event accompanied the 100 Flags for the Centenary of Polish Women’s Right to Vote march. A video of this event was then shown at the Between Salvation and the Constitution exhibition; image: Rafał Żwirek; Courtesy of the 100 Flag Collective.

Plate 20. / Marina Abramović The Hero, C-print, Spain, 2001, Ph: TheMahler.com, Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives

The first visual impression is optimistic and funny, but the next layer of meaning shakes you out of your self-satisfaction. Maybe that is why it is worth examining Eastern European art, which can be reduced to a minimalist message, but emphasizes the seriousness of the political and historical turbulence that devastates societies. Works that also use flags come to mind, but are the opposite of the examples given above. They have been stripped of their colors. Witness Marina Abramović’s video, Hero (plate 20.), the motive for which was the death of her father.

We perceive an almost static frame in which we can see the artist sitting on a white horse and holding a huge white flag in her hand. The difficult relationship with her father, who was involved in politics, and the collection of trivial objects that he left behind, were the reason for the artist’s emotions31. Another work is an installation by Bulgarian artist Pravdoliub Ivanov, entitled Territories (Plate 21). A row of flags is displayed as if they were a part of an official ceremony, but have been coated in mud.

The installation was shown for the first time at the 4th Istanbul Biennale, Turkey, in 1995. Personally, however, I had the opportunity to see the work at the 2006 4th Biennale of Contemporary Art in Berlin, curated by Maurizio Cattelan, Massimiliano Gioni and Ali Subotnick.

Plate 21. / Pravdoliub Ivanov Territories (1995), Fridericianum Museum, Kassel (Germany); Courtesy of the René Block Collection and the artist.

The subject of national symbols was something I also approached many years ago. It is another concept that has come back to me from a bygone age. In the Wschodnia Gallery in Łódź, I made a work called Poland Now (plates 22–27). The site-specific installation consisted in incorporating the red and white colors of the Polish flag into two interconnected rooms. Magdalena Bojarska described the existing space as follows: “The artist (...) has made it for the requirements of a specific interior (...). She has used two rooms as a place where the two colors characteristic for our Polish identity – red and white – function together. She has managed to get the colors to interact by covering the large panes of windows with (...) colored material. So in the red room, red is actually only the light that seeps through the window, and it feels like everything has taken on that color. She has turned the passage between the rooms into a revolving door made of white and red stripes of fabric. So you can twist them around to mix up the original colors of the rooms a little”.32 In each room there was also a container holding leaflets. “In the white room, clean and innocent (we all carry this code inside us), there are leaflets for apartments for sale. Among them is an advertisement for the artist’s apartment. In the red one, wild, but also hiding some danger, foreshadowing evil (again obvious associations), she has placed offers from escort agencies. Not only do the colors used correspond to the content associated with them, but they even emphasize them. The link that binds this double-track content is the graphic symbol Teraz Polska [Poland Now] and the message associated with it”.33

The installation title repeated the name of a logo which is a guarantee of high quality Polish products. It is also intended to be prestigious and be widely recognized. However, this original meaning has been lost, and the slogan Poland Now has become an area for discussion of negative phenomena in the country.

Plates 22-27. / Anna Klimczak (2001) Teraz Polska (Poland Now), Galeria Wschodnia (Wschodnia Gallery), Łódź (Poland); image: Jerzy Grzegorski.

Conclusion

The flag, a demonstration, a clarification of old, unsettled matters between religion and secular law. After all, the archeology of the past serves to understand the future. The collapse of institutions is astonishing, and the voice of the people on the streets refuses to die down. Mass protests during the pandemic demonstrate their opposition to the current situation (plate 28).

The consequences of the crisis are waves of new behavior. It is impossible to return to the old order. We have discovered too many secrets in the excavation of modern civilization to accept the current order. The crisis has brought problems, but also hope for cleansing. We have entered the shadowlands, as in Nicholas Galanin’s Shadow on the Land, an Excavation and Bush Burial. We have come full circle to once again sieve every thought, every blueprint we have pumped life into. We separate the impurities to start all over again.

Plate 28 / A protest on the tightening of the abortion law in Poland organized by the Women’s Strike (2020); image: Jasiek Zoll, aka MrFlyGuy; courtesy of Jan Zoll.

References

Abramović, M. (2016). Pokonać mur, Dom Wydawniczy REBIS.

Bojarska, M. (April 2001). “Teraz Polska” [Now Poland], “Wschodnia” Gallery. AKTIVIST. Łódź. Text retrieved from the artist’s private archive. The text was on the website: http://www.wschodnia.pl/html/terazpolska1.htm © 2001 Adam Klimczak/galeriawschodnia@go2.pl (website no longer exists)

The 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020). Nirin, Nicholas Galanin. Shadow on the Land, an Excavation and Bush Burial. https://www.biennaleofsydney.art/artists/nicholas-galanin

Clair, J. (2007). Malaise dans les musées [Discomfort in museums]. Flammarion. (Polish edition published 2009: Kryzys muzeów. Słowo/obraz terytoria)

Chehab, M. R. (2016). Nowa dyplomacja kulturalna. Co będzie z Instytutami Polskimi za granicą? Szykują się zmiany, Gazeta Wyborcza. https://wyborcza.pl/1,75410,19726733,polska-kultura-na-eksport-co-polubi-swiat.html

Dudek, A. J. (2018). Kraj, w którym ewangelia jest ważniejsza od konstytucji [A country where the gospel is more important than the constitution]. Wysokie Obcasy. http://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,100865,23793876,kraj-w-ktorym-ewangelia-jest-wazniejsza-od-konstytucji-witajcie.htm

Duncan, C. (1995). Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

100 Flags. (2020). Home [Facebook Page]. Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/100flagkobiet/

Gombrowicz, W. (1953). Śluby [Weddings]. In W. Gombrowicz, Dzieła [Literary works]: Vol. 6. Edited by J. Błoński (1986), Kraków.

Jarecka, D. (2007). Drżące ciała. Rozmowy z artystami, Gazeta Wyborcza. https://wyborcza.pl/1,75410,3898763.html

Kowalczyk, I. (2002). Niebezpieczne związki sztuki z ciałem. Galeria Miejska Arsenał.

Natszo (2016). Wróblewski podbił Hiszpanię. Ponad 120 tys. osób odwiedziło wystawę polskiego malarza. Gazeta Wyborcza. https://wyborcza.pl/1,75410,19688632,wroblewski-podbil-hiszpanie-100-tysiecy-osob-odwiedzilo-wystawe.html

Piotrowski, P. (2010). Agorafilia. Sztuka i demokracja w postkomunistycznej Europie. Dom Wydawniczy REBIS

Piotrowski, P. (2005). Awangarda w cieniu Jałty [In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989]. Dom Wydawniczy REBIS.

Piotrowski, P. (2011). Muzeum krytyczne. Dom Wydawniczy REBIS.

redPor (2001). Wystawa Anny Klimczak w Łodzi, Gazeta Wyborcza. https://lodz.wyborcza.pl/lodz/1,35135,220577.html

Sarzyński, P. (2018). Biało-czerwono-czarna [White-red and black]. Polityka nr 49/3189

Sienkiewicz, K. (2019). Kto się boi bananów Natalii LL, czyli dulszczyzna i cenzura w Muzeum Narodowym. Dyrektor Miziołek wyskoczył przed szereg. https://wyborcza.pl/7,112588,24708236,kto-sie-boi-bananow-natalii-ll-czyli-dulszczyzna-i-cenzura.html

Słomski, D. (2017). Paweł Potoroczyn wygrał w sądzie pracy z wicepremierem Glińskim, MONEY.PL. https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/wiadomosci/artykul/pawel-potoroczyn-sad-pracy-zwolnienie-piotr,38,0,2239782.html

Wasilewska, D. (2014). Kto komu zrobił psikusa? Wystawa „Instalatorzy” w poznańskiej ArtStations Foundation, Kultura Liberalna. https://kulturaliberalna.pl/2014/07/01/komu-zrobil-psikusa-wystawa-instalatorzy-poznanskiej-artstations-foundation/

Wasilewski, M. (2001). Przedmioty i Przestrzenie [Objects and Spaces]. In Promocje Wieży Ciśnień; Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej. Wieża Ciśnień.

Żmijewski, A. (2006). Drżące ciała. Rozmowy z artystami [Shivering Bodies. Conversations with artists]. Seria Krytyki Politycznej, Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej.

Monographs

Klimczak, A. (2003). Sztuka wobec instytucji. Poznań

Klimczak, A. (1998). Przestrzenie dla Przestrzeni. ASP w Poznaniu.

Notas

1. Piotr Sarzyński (2018). Biało-czerwono-czarna, Polityka no. 49/3189.

2. Piotr Sarzyński (2018). Biało-czerwono-czarna, Polityka no. 49/3189.

3. This term was used by Ryszard Kluszczyński (1999) in: Put artists in the stocks, send art critics to the psychiatric ward, i.e. the latest discussions on critical art in Poland. EXIT no. 4/40.

4. The Iron Curtain, a term used to describe the isolation of areas under USSR domination from the non-communist world, came from a speech by Churchill in Fulton, USA (March 1946), in which he called on the United States to oppose Stalin’s policy aimed at expanding Soviet influence and the communist system. This speech is considered to signal the start of the Cold War. The Berlin Wall, erected in 1961, was the most eloquent proof of the existence of the Iron Curtain; the division of Europe, symbolized by the Iron Curtain, lasted until 1989, when the collapse of the communist system in Central and Eastern Europe began. https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo/zelazna-kurtyna;4002896.html

5. Piotr Piotrowski (2005). Awangarda w cieniu Jałty, Dom Wydawniczy REBIS [EN: In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989; Reaktion Books Ltd, 2009].

6. Piotr Piotrowski (2010). Agorafilia. Sztuka i demokracja w postkomunistycznej Europie, Dom Wydawniczy REBIS [EN: Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe, Reaktion Books Ltd, 2012].

7. Piotr Piotrowski (2011). Muzeum krytyczne, Dom Wydawniczy REBIS.

8. Izabela Kowalczyk (2002). Niebezpieczne związki sztuki z ciałem, Galeria Miejska Arsenał.

9. Artur Żmijewski (2006). Drżące ciała. Rozmowy z artystami, Seria Krytyki Politycznej, Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej.

10. Dorota Jarecka (2007) Drżące ciała. Rozmowy z artystami, Gazeta Wyborcza, retrieved from: https://wyborcza.pl/1,75410,3898763.html (own translation).

11. Milena Rachid Chehab (03/07/2016) Nowa dyplomacja kulturalna. Co będzie z Instytutami Polskimi za granicą? Szykują się zmiany, Gazeta Wyborcza, retrieved from: https://wyborcza.pl/1,75410,19726733,polska-kultura-na-eksport-co-polubi-swiat.html

12. Mil Natszo (02/27/2016) Wróblewski podbił Hiszpanię. Ponad 120 tys. osób odwiedziło wystawę polskiego malarza. Gazeta Wyborcza, retrieved from: https://wyborcza.pl/1,75410,19688632,wroblewski-podbil-hiszpanie-100-tysiecy-osob-odwiedzilo-wystawe.html

13. The information refers to: Damian Słomski (01/21/2017) Paweł Potoroczyn wygrał w sądzie pracy z wicepremierem Glińskim, MONEY.PL, retrieved from:: https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/wiadomosci/artykul/pawel-potoroczyn-sad-pracy-zwolnienie-piotr,38,0,2239782.html

14. Aureliusz M. Pędziwol, (10/14/2020) Nie chcieli jej w Katowicach. Teraz pokieruje Galerią Narodową w Pradze, Deutsche Welle, retrieved from: https://www.dw.com/pl/nie-chcieli-jej-w-katowicach-teraz-pokieruje-galeri%C4%85-narodow%C4%85-w-pradze/a-55270051

15. Karol Sienkiewicz (28 / 04 /2019) Kto się boi bananów Natalii LL, czyli dulszczyzna i cenzura w Muzeum Narodowym. Dyrektor Miziołek wyskoczył przed szereg, retrieved from: https://wyborcza.pl/7,112588,24708236,kto-sie-boi-bananow-natalii-ll-czyli-dulszczyzna-i-cenzura.html?disableRedirects=true

16. Anna J. Dudek (08/17/2018) Kraj, w którym ewangelia jest ważniejsza od konstytucji, Wysokie Obcasy, retrieved from: http://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,100865,23793876,kraj-w-ktorym-ewangelia-jest-wazniejsza-od-konstytucji-witajcie.html

17. Carol Duncan (1995). Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums. Taylor & Francis Ltd

18. Piotr Piotrowski (2011) Muzeum krytyczne. Dom Wydawniczy REBIS, p.22 (own translation)

19. Jean Clair (2007) Malaise dans les musées. Flammarion; Polish edition: Jean Clair Kryzys muzeów, Wydawnictwo słowo/obraz terytoria, Gdańsk (2009), p. 92 (own translation)

20. Jean Clair (2007) Malaise dans les musées, Flammarion; Polish edition: Jean Clair Kryzys muzeów, Wydawnictwo słowo/obraz terytoria, Gdańsk (2009), p. 92 (own translation)

21. Marek Wasilewski (2001) Przedmioty i Przestrzenie, in: Promocje Wieży Ciśnień, Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Wieża Ciśnień, Konin (Poland)

22. Marek Wasilewski (2001) Przedmioty i Przestrzenie, in: Promocje Wieży Ciśnień, Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Wieża Ciśnień, Konin (Poland)

23. A private Polish contemporary art gallery in Warsaw founded by Łukasz Gorczyca and Michał Kaczyński in 2001.

24. Diana Wasilewska (2014) Kto komu zrobił psikusa? Wystawa „Instalatorzy” w poznańskiej ArtStations Foundation, Kultura Liberalna, retrieved from: https://kulturaliberalna.pl/2014/07/01/komu-zrobil-psikusa-wystawa-instalatorzy-poznanskiej-artstations-foundation/

25. Diana Wasilewska (2014) Kto komu zrobił psikusa? Wystawa „Instalatorzy” w poznańskiej ArtStations Foundation, Kultura Liberalna, retrieved from: https://kulturaliberalna.pl/2014/07/01/komu-zrobil-psikusa-wystawa-instalatorzy-poznanskiej-artstations-foundation/

26. Excerpt from my doctoral dissertation, Anna Klimczak (2003) Sztuka wobec instytucji, Poznań (own translation)

27. Excerpt concerning my doctoral dissertation, Anna Klimczak (1998) Przestrzenie dla Przestrzeni, promotor: prof. Alicja Kępińska, ASP w Poznaniu

28. Witold Gombrowicz (1953) Śluby, in: W. Gombrowicz Works Vol. 6. p. 288; ed. J. Błoński (1986), Kraków (own translation)

29. 100 Flags (2020), from Facebook Fan Page, retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/100flagkobiet/

30. Piotr Sarzyński (2018) Biało-czerwono-czarna, Polityka (No. 49/3189)

31. Marina Abramowic (2016) Pokonać mur [Walk Through Walls]. Dom Wydawniczy REBIS, p. 298

32. Magdalena Bojarska “Teraz Polska” [Now Poland], “Wschodnia” Gallery, AKTIVIST (April 2001), Łódź. Text retrieved from the artist’s private archive. The text was on the website: http://www.wschodnia.pl/html/terazpolska1.htm © 2001 Adam Klimczak / galeriawschodnia@go2.pl (website no longer exists); see also: redPor (April 6 2001) Wystawa Anny Klimczak w Łodzi, Gazeta Wyborcza, retrieved from:https://lodz.wyborcza.pl/lodz/1,35135,220577.html

33. Magdalena Bojarska “Teraz Polska” [Now Poland], “Wschodnia” Gallery, AKTIVIST (April 2001), Łódź. Text retrieved from the artist’s private archive. The text was on the website: http://www.wschodnia.pl/html/terazpolska1.htm © 2001 Adam Klimczak / galeriawschodnia@go2.pl (website no longer exists); see also: redPor (April 6 2001) Wystawa Anny Klimczak w Łodzi, Gazeta Wyborcza, retrieved from:https://lodz.wyborcza.pl/lodz/1,35135,220577.html