We become what we

behold.

(McLuhan, 2001:

20)

1. INTRODUCTION: CRONENBERG TAKES MCLUHAN AT HIS WORDS

In Understanding Media,

his landmark study of media as «the extensions of man», Canadian media theorist

Marshall McLuhan first coined the catchphrase so dear to the world of

advertising: «the medium is the message» (2001: 7). The publication of his next

book with the tongue-in-cheek title The Medium is the Massage

transformed McLuhan into a media «guru», as he became a fixture on television

panel shows discussing the impact of media on popular culture, politics and

personal psychology, even giving an extended interview to Playboy magazine.

McLuhan argued that the impact of communications media on our lives is

omnipresent: «All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their

personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and

social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected,

unaltered. The medium is the massage» (2008: 26). Media, McLuhan maintained, «massage»

our thinking into quiescence by encouraging us to examine their content rather

than their nature qua media, thus putting critical reflection on their

unforeseen consequences to sleep. Media’s very omnipresence blinds us to their

influence on life and thought; media’s impact, McLuhan believed, tends to

remain unperceived and unthought.

It

is no exaggeration to say that McLuhan’s work had a major impact on his

compatriot, the film-maker David Cronenberg. This is not surprising for two

reasons. The first is that Cronenberg attended the University of Toronto at the

same time that McLuhan taught there. Though Cronenberg didn't attend McLuhan’s

lectures, he certainly did fall under the media scholar’s spell as he recalls:

«suddenly Marshall McLuhan was the guru of communications and was on all the TV

shows and in all magazines» (Grünberg, 2006: 66); in another interview, he admits

he «read everything [McLuhan] wrote» (Browning, 2007: 64). The second reason

concerns the film-maker and theorist’s shared conception of technology: for

both McLuhan and Cronenberg, technology plays an inseverable part in our

make-up as a species. Technology endows us with what McLuhan called vital

«extensions» of our senses only by severing (a verb with obvious

Cronenbergian connotations) us from old ways of perceiving and thinking about

the world (2001: 4). These techno-extensions alternately expand and contract

consciousness as they «shift the ratios among all the senses» (McLuhan, 2001: 71).

«I

don’t believe anybody is in control», Cronenberg told Chris Rodley, «That’s

what McLuhan was talking about when he said the reason we have to understand

media is because if we don’t it’s going to control us» (Rodley, 1992: 67).

Cronenberg was referring to McLuhan’s conception of media as «minor religions»

at the altars of which we worship each time we direct attention towards

screen-content through which the new gods talk to and «control us»:

To behold, use, or

perceive any extension of ourselves in technological form is necessarily to

embrace it. To listen to radio or to read the printed page is to accept these

extensions of ourselves into our personal system and to undergo the «closure»

or displacement of perception that follows automatically […] By continuously

embracing technologies, we relate ourselves to them as servo-mechanisms. That

is why we must, to use them at all, serve these objects, these extensions of

ourselves, as gods or minor-religions. (2001: 50-51).

The notion of technology

as something that we come to serve, even something to which we willingly

submit, would inspire some of Cronenberg’s best work, not least Videodrome, the director’s most «McLuhanesque» film.

The insectoid talking typewriter in Naked Lunch; the organic video game

console in eXistenZ; the diary written in

hieroglyphics mirroring the protagonist’s arcane mind in Spider; the

breathing voluptuous TV set in Videodrome—these

are among the most obvious incarnations of the film-maker’s philosophical

concerns. For if Cronenberg’s oeuvre can be said to embody a philosophical

position, then one could do worse than describe it as a kind of phenomenology

of the media subject. To watch a Cronenberg film is to «become interwoven with

the «I» of the characters» (Pearson, 2012: 166), who are all too often

subjected to an impressively vicious form of psychic and physical malaise of

technological origin. In this sense, many of Cronenberg’s films can be seen as

case studies of technology-induced disease: «David Cronenberg», as Gabriel Bortzmeyer aptly puts it, «presents a nosology of the media

subject» (my translation, 2021).

McLuhan’s

influence on Cronenberg is no secret and virtually all major studies of the

director’s oeuvre to date recognize this fact. Such recognition, though,

typically amounts to little more than the aforementioned acknowledgment of

shared concerns about the fact that, in McLuhan’s words, «Whole cultures could

now be programmed to keep their emotional climate stable» via the manipulation

of communications media and/or the implementation of technological prostheses

for nefarious ends (2001: 30)[1].

What is missing in Cronenberg studies, and certainly in discussions of Videodrome, is an examination of the ways in which

Cronenberg actually adapts the account of television in Understanding

Media, as well as in its bestselling sequel, and of how McLuhan’s

two books can be seen as source texts informing the film’s dialogue, motifs and

even plot points.

In an uncharacteristic

first person aside, McLuhan reflects: «I am curious to know what would happen

if art were suddenly seen for what it is, namely, exact information of how to

rearrange one’s psyche in order to anticipate the next blow from our own extended

faculties» (2001: 63). I want to suggest that Videodrome

presents the viewer with the spectacle of just this: it unveils in

visceral cinematic imagery the concealed nature of media that McLuhan’s text

discloses by means of aphorism and figurative image. In doing so, the film foreshadows

«the next blow» to our collective psyche, this time in the guise of tactile

interactive screens fitted onto globally connected gadgets (i.e. smart phones,

smart watches, smart glasses, Neuralink implants)

anticipated by the nominally tactile television medium as theorized by McLuhan[2].

From the point of view of

adaptation, Videodrome is unique in

Cronenberg’s oeuvre, because, unlike the director’s adaptations of literary

texts (The Dead Zone, Dead Ringers, Spider, Cosmopolis),

the film is a bona fide cinematic adaptation of—and not merely, as I aim to

show, a work «inspired by»—McLuhan’s writing. The article begins by drawing on

the relevant literature in adaptation studies in order to provide a suitable

framework for this atypical case of cinematic adaptation. What further

complicates and enriches matters is the fact that there exist not one but two «Videodromes»: after Cronenberg completed the first draft of

the original screenplay (which would undergo further revisions during filming)

he agreed for the novel adaptation to be released at the same time as the film.

He invited the respected fantasy writer Dennis Etchison, then writing under the

pseudonym Jack Martin, to Toronto; Martin, working with the original script,

completed the novel in time for the film’s release in 1983 (Lucas, 2008: 119).

What this means, in fact, is that Martin’s novel is as close as the viewer can

get to the film’s original text: by comparing the ways in which Videodrome the film and Videodrome

the novel both differ from and echo each other, this article seeks to

demonstrate the significance of McLuhan’s work for a richer understanding not

only of Cronenberg’s chef-d’oeuvre, but of the process of cross-media

adaptation itself.

This

article is inspired by a provocative remark made by Steven Shaviro

in The Cinematic Body. In the chapter devoted to Cronenberg, Shaviro writes: «The brutally hilarious strategy of Videodrome is to take media theorists such as

Marshall McLuhan and Jean Baudrillard completely at their word, to overliteralize their claims for the ubiquitous

mediatization of the real» (2006: 138). A discussion of Baudrillard’s idea of

media-created simulations becoming more real than flesh and blood is beyond the

scope of the present essay; as far as McLuhan is concerned, Shaviro’s

remark reveals more than he intended by it. Cronenberg’s film not only makes

palpable the claims made in Understanding Media about the nature and

cultural impact of media: it actively adapts and appropriates McLuhan’s style

of thinking and manner of expression. Cronenberg literally takes McLuhan

at his words.

2. ADAPTATION, DIALOGUE,

APPROPRIATION

Considering

Videodrome through the lens of adaptation

poses a challenge. Unlike other Cronenberg adaptations, we are not dealing with

a transposition of a literary text to the big screen. Instead, the film adapts

the argument and metaphors deployed in Understanding Media as disturbing

mise en scène. The

film’s novelization by Jack Martin too sheds light on Cronenberg’s adaptation

of McLuhan’s work, in that it gives the viewer access to the film’s «original»

text: reading Videodrome the novel, that is,

allows us to glimpse elements of the original screenplay that informs the

imagery we see, thereby attesting to the intermedial nature of the interpretive

act.

Setting

aside the ambiguous and rather unhelpful notion of fidelity to a source text,

Robert Stam proposes that we instead think of adaptation practice as

translation, or what he also calls «intersemiotic

transposition» from one sign system to another (2000: 62). Since we are

concerned with a cinematic transposition of theoretical ideas, this is a more

promising way of understanding how one kind of metaphor (conceptual) can become

another (visual). «Imagery is important to me, ultimately because of the metaphor»,

Cronenberg remarks, «In a way, imagery is not even imagery. It has a

metaphorical weight» (Grünberg, 2006: 70). Indeed, the metaphorical imagery in Videodrome is «weighty», as we will see, precisely

because it enters into dialogue with the oracular conceptual language used to

describe the nature of television in McLuhan’s text.

Drawing

on Mikhail Bakhtin and Julia Kristeva, Stam suggests that a fruitful way to

characterize intermedial adaptation is the notion of «dialogical process», an

ongoing contestation of verbal meaning and intertextual exchange (2000: 64).

However, intertextuality and its kindred notions of «a tissue of texts», the

palimpsest, and so on, tends to minimize specificity, inferring as it does a

nebulous galaxy of texts as potential sources of allusive meaning. This fact

prompted Gérard Genette to constrain the concept of intertextuality to mean the

co-presence of two texts, for example in the form of quotation, allusion, or

even plagiarism (Stam, 2006: 65). A related concept introduced by Genette is «hypertextuality»: here, Genette distinguishes between a «hypotext», defined as a clearly identifiable source or

proto-text, and a «hypertext», a new work based on the source text (1997: 5). Videodrome thus seems to commit us to a

triangulation of concepts: the film’s key hypotexts,

I have suggested, are Understanding Media and The Medium is the

Massage, because a close reading of these texts promises a fuller

understanding of the film’s themes and plot. But McLuhan’s works also act as hypotexts for Videodrome

the novel (which, incidentally, opens in a paratextual signalling of its hypotext with the epigraph «the medium is the massage»).

Our third adaptation vector, then, is the relationship between the film and the

novel as both relate to their source texts.

Now,

it might be objected that, unlike in customary adaptation practice where a

film-maker adapts a literary text and where there is an unambiguous

relationship between hypo- and hypertext (i.e. the characters, and sometimes

even the titles, have the same names, the plot is more or less similar), an

adaptation of a theoretical text risks diluting the specificity of the concept «adaptation»[3]. Recognizing the many pitfalls to be negotiated when trying to talk

about adaptation, Julie Sanders suggests the concept of appropriation.

Appropriation refers to a more diffuse kind of adaptation, where «the

appropriated text or texts are not always as clearly signalled or acknowledged

as in the adaptive process. They may occur in a far less straightforward

context» (Sanders, 2006: 27). The lack of such clear signalling in Videodrome would seem to qualify it as a case of

appropriation, rather than adaptation proper. There is a further important

distinction between appropriation and adaptation: an appropriation does not

seek to retell or reproduce the same content as the original text; instead, it

presents a reworking, a reinterpretation and even a critique of the source text

(Sanders, 2006: 28). Videodrome, from this

perspective, is certainly not a mouthpiece for McLuhan’s ideas about modern

communication media; in fact, the film often playfully satirizes the «guru» of

media studies. And yet, if we fail to consider how much the film owes to Understanding

Media and The Medium is the Massage, we risk not seeing all that the

film has to show us. To appreciate the full extent in which Cronenberg employs

McLuhan’s writing, it is perhaps best to see his film as an appropriation of a

style of thought carried out by means of the visual adaptation of the language

in which this thought is expressed. That is to say, in appropriating McLuhan’s

pronouncements about media Cronenberg’s film adapts (us to) the media

theorist’s figurative language as cinematic image.

3. THE VOICE OF

THE MEDIA PROPHET

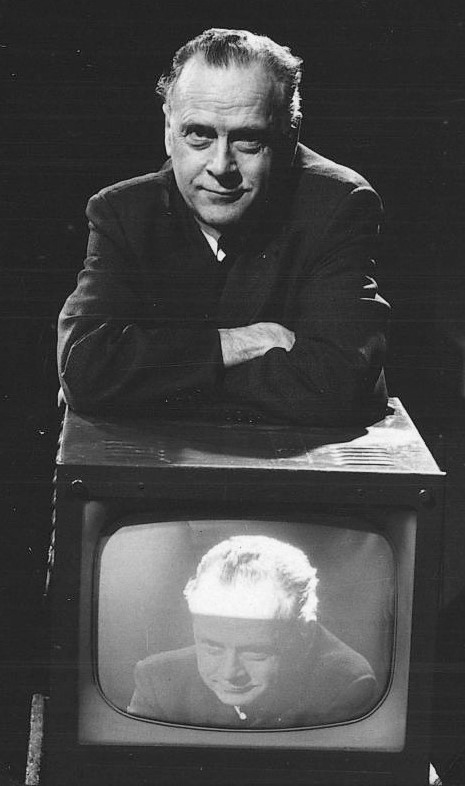

Before

examining the film’s imaging of McLuhan’s concepts, it seems apt to begin with

the figure of the man himself (see fig. 1). McLuhan’s stand-in in Videodrome is of course Professor Brian O’Blivion, whom we meet early on in the story. Max Renn

(James Woods), president of CIVIC-TV, a channel specializing in risqué television

programmes, has been invited to participate in a panel discussion on a late-night

talk show hosted by Rena King (Lally Cadeau). He is joined by Nicki Brand

(Debbie Harry), a pop psychologist with masochistic tendencies, and the famous

media expert Professor O’Blivion, who joins the panel

via what we assume is a live television broadcast. Having O’Blivion

appear throughout the film only on television is an ingenious representation of

the heavily mediatized persona of McLuhan (who would himself go on to make a

famous cameo appearance in Woody Allen’s 1997 classic, Annie Hall).

According to Tim Lucas, the original script describes O’Blivion

«as a cross between Marshall McLuhan and Andy Warhol» (1983: 35), though it

must be said that casting Jack Creley in the role certainly gives him more of a

McLuhan look (see fig. 2). King asks O’Blivion

whether he thinks that erotic and violent TV content lead to the

desensitization and dehumanization of its viewers; his response is nothing

short of McLuhanesque: «The television screen has become the retina of the

mind’s eye»—a clear echo of McLuhan’s statement in The Medium is the Massage:

«In television, images are projected at you. You are the screen» (2008: 125).

McLuhan’s

overt representation in the film is certainly not without irony. Later in the

story, Max learns from O’Blivion’s daughter, Bianca

(Sonja Smits), that her father has been dead for over a year and that all his

television appearances were pre-recorded on videotape. Max then plays one such

recording and watches O’Blivion deliver another

volley of seemingly connected statements, beginning with a repetition of the

aforementioned comment that left the talk show host understandably nonplussed:

The television screen is

the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore the television

screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore

whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those

who watch it. Therefore, television is reality and reality is less than

television (Cronenberg, 1983).

The

film cuts to a close up of Max, who snorts in contempt. In the novel’s

rendition of this scene, narrated in free indirect style, we read: «The way he

put it, it sounded eminently logical. Or did it? […] He’s a pro. Media prophet,

isn’t that what they call him? It’s a little spooky» (Martin, 1983: 100). The «spookiness»

Max refers to is the fact of listening to a dead man address you on videotape.

But the «spookiness» also points to more than this: in the novel, O’Blivion is given the following extra lines of dialogue:

«For those who have a natural propensity for its imagery, [television is] a

kind of bio-electric heroin. Your brain has already become an electron gun.

Your retinae have become video screens» (Martin, 1983: 101). In one sense,

these lines can be read as a parody of McLuhan’s portentous style of writing;

to read them as such, however, is to miss the fact that they are a paraphrase

of McLuhan’s actual concepts. When watching television, McLuhan (not O’Blivion) writes: «You are the screen. The images wrap

around you. You are the vanishing point» (2008: 125); elsewhere, he describes

the content of a medium as «the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to

distract the watchdog of the mind» (2001: 19).

McLuhan’s

media theory is filled with language of this kind, with imagery suggestive of

invasion, mutation, transformation, building up a picture of a body under

constant bombardment by information signals coming from without, even as it is

made to extend its faculties of sense perception without acquiescing to do so.

4. TELEVISION AND

THE BODY

If

there is a single passage in McLuhan’s work that might be taken to be

representative of Cronenberg’s oeuvre, and that could well be read as its

unstated motto, it is this one:

With

the arrival of electric technology man extended, or set outside himself, a

live model of the central nervous system itself. To the degree that this is

so, it is a development that suggests a desperate and suicidal autoamputation,

as if the central nervous system could no longer depend on the physical organs

to be protective buffers against the slings and arrows of outrageous

mechanism (my italics, 2001: 48).

«A

live model of the central nervous system», «autoamputation», «outrageous

mechanism»: one struggles to find more fitting phrases to characterize

Cronenberg’s cinematic universe. Cronenberg’s cinema often presents us with

visions of «outrageous mechanism» (Crash, Crimes of the Future)

assaulting and altering the human body, and it repeatedly shows us how the

extensions of «the central nervous system», made possible by technology, lead

to grotesque bodily transformations and the consequent mutation of identity (The

Fly, eXistenZ, Scanners).

McLuhan’s

discussion of the impact of media on consciousness hinges on a distinction he

makes between «hot» and «cool» media (2001: 24-26). A «hot» medium, like radio

or photography, tends to discourage active audience participation: it presents

its content in a relatively straightforward, «high definition» manner. A «cool»

medium, on the other hand, allows for greater participation and interpretive

scope, and McLuhan considered television to be exemplary in this regard. Before

the advent of high-definition TV, television presented a grainy low quality image shown on a relatively small screen. Unlike

the crisp image projected on the cinema screen, the image emitted by TV is low

in visual data, requiring the viewer to «fill-in» missing details; the TV image

is, moreover, «closer» to the viewer in space so that you can even touch it.

Cinema is, then, a «hotter» medium than television[4].

This

is how McLuhan describes the nature of what we see on TV: «The TV image

requires each instant that we “close” the spaces in the mesh by a convulsive

sensuous participation that is profoundly kinetic and tactile, because

tactility is the interplay of the senses, rather than the isolated contact of

skin and object» (my emphasis, 2001: 342). Videodrome

portrays this kind of tactile impact on consciousness by the sensory «extension»

of television. The film opens with an extreme close-up shot of a TV screen: we

see the face of a young woman addressing the camera; it is Max’s secretary,

Bridey (Julie Khaner), calling him with a scheduled

wake-up call. The establishing shot does two things: first, the close-up of the

TV screen foregrounds the film’s concern with mediation: Bridey’s face speaking

directly into the film’s camera via a television screen is like the director’s

way of saying, with McLuhan, that «no medium has its meaning or existence

alone, but only in constant interlay with other media» (2001: 28). Second, the

opening scene places the viewer within the same space inhabited by the

protagonist: we feel as though we too are being addressed by the speaker, whose

grainy image seems more tangible than the cinema screen on which it appears. As Gorostiza

and Pérez write, the opening scene «provoca que el

espectador se convierta en un personaje que, como Max, tiene delante una

pantalla que podría en cualquier momento interactuar con su vida» (2003: 167)[5]. From this point onward, the television set becomes a living and

breathing character in its own right, interacting vicariously with the viewer.

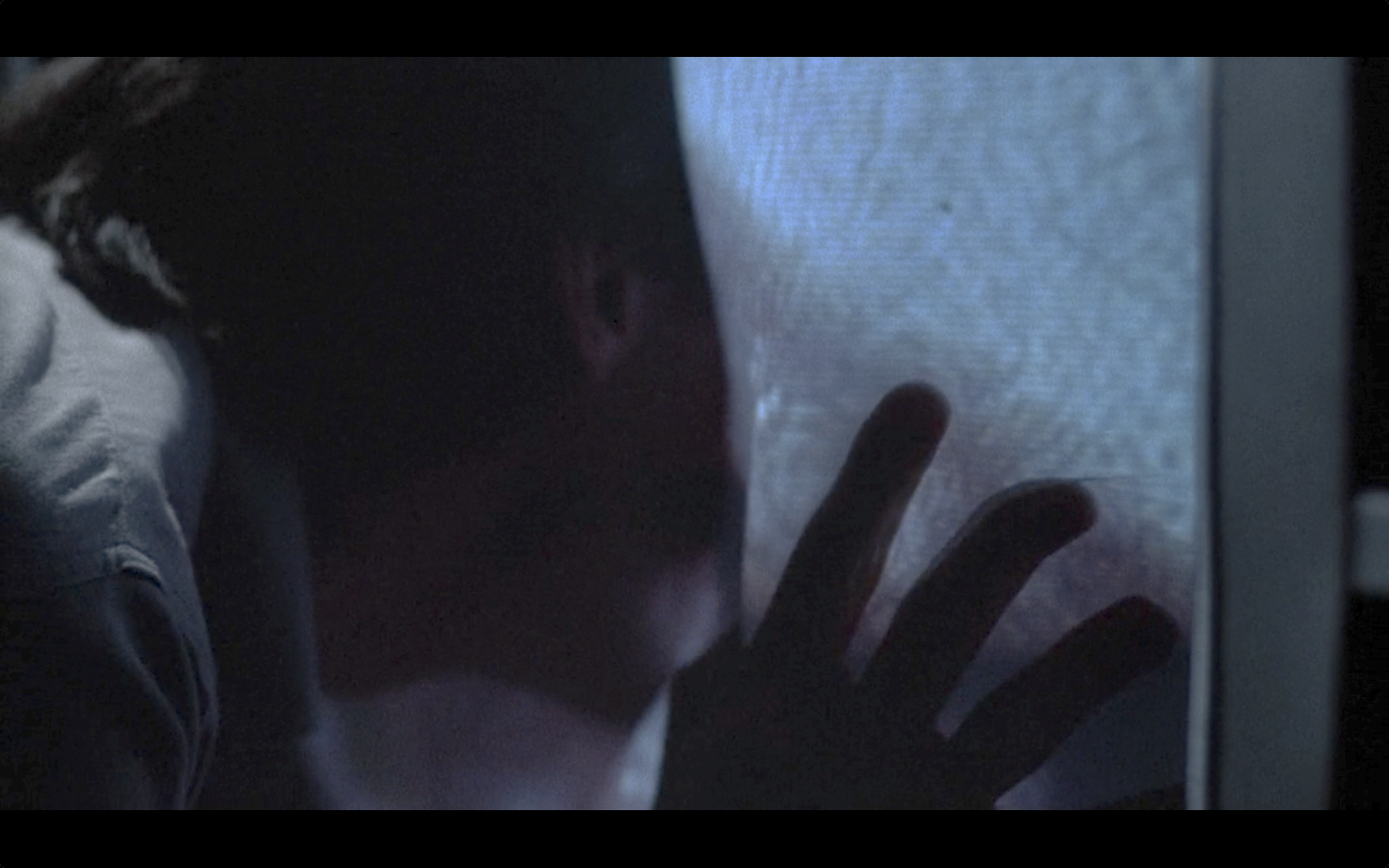

In

the history of cinema, there is perhaps no other film that has portrayed the

tactile aspect of television quite as memorably as Videodrome.

Throughout the film, we see Max stroke, caress, kiss, grope, whip and finally

shoot the television set. The film’s iconic moment is the scene where Max

kisses Nicki Brand’s televised lips: the scene begins with the point of view

shot of Brand speaking to Max as she invites him to join her «inside»

television, signalling the beginning of his becoming a slave to the «Videodrome» signal. Next, there’s the medium shot of Max

kneeling before the set as he bends forward, his face making intimate contact

with the screen’s fleshy exterior[6]. Finally, we see a close-up of Max’s face buried inside the TV screen as

his fingers prod its pliable surface (see fig. 3).

McLuhan

stressed television’s tactility: «TV is, above all, an extension of the sense

of touch, which involves maximal interplay of all the senses» (2001: 364); «In

television there occurs an extension of the sense of active, exploratory touch

which involves all the senses simultaneously, rather than that of sight alone»

(2008: 125). The reason McLuhan identifies television with the sense of touch,

rather than sight or hearing, is to underscore the fact that the TV image,

unlike the projected image of cinema, is emitted from within: «the

viewer is the screen» (McLuhan, 2001: 341). The old CRT screen produced static

so that when touching it you would occasionally receive a not unpleasant

sensation of shock, making physical contact with the electronic signal of the

cathode ray tube. This is why television, more so than cinema, speaks of

humanity’s intimacy with media, of its welcome occupation of our most private

living spaces and of its serving our most secret, even

shameful desires (we are concerned here with the age before the global home

invasion by smart phones). In another flight of mixed metaphor, McLuhan writes:

«The TV viewer […] is bombarded by atoms that reveal the outside as inside in

an endless adventure amidst blurred images and mysterious contours» (2001:

357). The violent opening image shape-shifts into the metaphor of «an endless

adventure» across a topography of «blurred images and mysterious contours»,

conveying the implicit eroticism of TV, what McLuhan also refers to as «the

indomitable tactile promptings of the TV image» (2001: 344). Martin’s

novelistic rendition of Max kissing Brand’s televised lips portrays the

symbiosis between the virtual world of television and the corporal world of the

viewer very effectively:

As

he grasped the breathing sides of the set, her larger-than-life lips distended

to meet his forehead, the glass of the tube melting and ballooning outward to

touch his skin […] Max’s eyes closed. He no longer needed them to see. Nicki

Brand fired through his eyelids as though they were no longer there, a mere

technicality. He licked the screen, the soft screen, distorting the plastic

face of Nicki Brand as he strained toward the possibility of acceptance and

release in her, caressing her, sinking deeper into the pores and pulsing veins,

the wet membranes of her flesh. The mouth widened in response. Her teeth

opened, revealing the glistening sea of her tongue, the video scan lines

growing wider, separating horizontally and opening to receive him between their

strobing, deeper and deeper into the swelling red lips, until he was totally

engulfed by the darkness in her throat (Martin, 1983: 102-3).

Visualizing

this scene, we no longer distinguish the seam between the virtual and the real

as the world of TV engulfs the world of flesh: as one commentator puts it, in

Cronenberg’s world «los medios

son cuerpos virtuales de

las imágenes tanto como transformadores de la percepción

corporal subjetiva» (Russo, 2017).

5. THE VERBAL

SCREENING OF VIRTUAL IMAGES

As

the above excerpt illustrates, Martin’s adaptation captures the film’s imagery

in words exceptionally well—especially considering the fact that Martin did not

get to see the film and only had Cronenberg’s script to work with when writing

the novel. But perhaps this is not that surprising: it is safe to assume that

most readers of Martin’s adaptation of the original screenplay of Videodrome come to read the novel only after

watching the film. McLuhan liked to reiterate that «the “content” of any medium

is always another medium» (2001:8) and «no medium has its meaning or existence

alone, but only in constant interplay with other media» (2001: 28). This kind

of media «interplay» is most apparent when we engage with adaptation, where a

particular text/film acts as the grain against which critical reading must rub.

«As we read», Stam writes, «we fashion our own imaginary mise-en-scène of the novel on the

private stages of our minds» (2000: 540). Stam is describing what we do when we

read a literary text, but when it comes to Videodrome’s

plot and characters, the privacy of our minds’ «stages» is somewhat

compromised. Reading the novel, it is a challenge not to imagine James

Woods’ engrossing portrayal of the protagonist and not inwardly picture Debbie

Harry as Nicki Brandt: the film’s iconography provides the viewer with the

visual aesthetic according to which the novel’s success, as an adaptation, is

measured. As one reads (assuming one has seen the film before reading the

novel) one’s recollection of the film’s scenes continually contests one’s

visualization of the novel’s restaging of them.

And

yet we do see something in the novel that we did not see in the film. Consider

the excerpt above: Brand’s teeth open, revealing «the glistening sea of her

tongue, the video lines growing wider, separating horizontally and opening to

receive him between their strobing, deeper and deeper into the swelling red

lips». If the film is distant in memory, one might well imagine that this special effects widening of video lines was something

that we actually saw on the screen, though we did not. Similarly, when reading

a descriptive passage like the following one, it is easy to misremember the

film:

As

[Max] watched in disbelief, a TeleRanger console TV

set rose up out of the water, out of the blue Algemarin

foam like a hulking electronic Venus on the half-shell. The set swelled,

breathing and snorkling as befitted a marine creature

of its substantial size.

On

its screen was a close-up of a woman, an anguished expression wracking her

features, a leather strap tight around her wrinkled neck.

Masha

(my italics, Martin, 1983: 166).

At

the time of reading Martin’s novel, having last watched Videodrome

several years ago, I could not say whether this scene was in the film or not

(it is not). It certainly felt like it should be[7].

The

metaphor in the passage above has been italicized to draw attention to the

virtuality that is inherent in a verbal description to a much greater degree

than is possible in film; as Stam puts it, «The words of a novel […] have a

virtual, symbolic meaning; we as readers, or as directors, have to fill in

their paradigmatic indeterminacies» (2000: 55). Like the preceding example of

the scene of Max kissing the fleshy television set, this scene is another

instance of the literary device known as ekphrasis. Though it is often used in

the more restricted sense of a verbal description of a visual artwork,

ekphrasis designates, in Bolter’s definition, «the description in prose or

poetry of an artistic object or striking visual scene; it is the attempt to

capture the visual in words» (1996: 264). Ekphrasis is synonymous with an

intensely visual and emotionally resonant description, bringing to the fore the

«interplay» between media which is always a key part of adaptation criticism. Hence,

Liliane Louvel describes ekphrasis as «an intermedial

mixture of word and image» (2018: 246) while Claus Clüver defines it as process

of «intermedial translation» (2017: 465).

Perhaps

the most important recent critical contribution to the study of ekphrasis is

Ruth Webb’s Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion in Ancient Rhetorical

Theory and Practice, where Webb traces the earliest known uses of

ekphrastic speech and writing, showing the heuristic value of ekphrasis for

modern cinema, media, and literary studies. Most simply, ekphrasis can be

defined as «a speech that brings the subject matter vividly before the eyes»

(Webb, 2016: 1). As the two examples from Martin’s Videodrome

attest, the most effective way of conveying visuality verbally is by means of

descriptive metaphor, particularly if said metaphor happens to be intermedial: «like

a hulking electronic Venus on the half-shell», the striking comparison that

personifies and estranges its object (an '80s TV set) by invoking Botticelli’s

Venus, allows the reader of the novel to experience the sensation of «seeing»

an animate TV rising out of Max’s bathtub through his eyes, such that this

image conveys «the imperceptible and almost ineffable: the speaker’s state of

mind at a precise moment in the past» (Webb, 2016: 191).

What

is crucial about ekphrasis, then, and what makes it a valuable tool when

considering cinematic adaptation and/or novelization of film, is the fact that

it immerses us inside the mind of the protagonist. Ekphrasis is impossible

without a distinct point of view: what we see in ekphrasis is «not so much an

object or scene or person in itself, but the effect of seeing that thing», Webb

notes (2016: 127)[8]. Indeed, all that we see when we read Videodrome

is focalized through the eyes of Max Renn: the novel is narrated in a free

indirect style at times almost taken over by first person narration, as Max’s

voice vies for dominance with the voice of the third person narrator. The

following passage illustrates how focalization is used throughout the text:

«Now I’ve done it, thought Max forlornly. Caffeine nerves, insomnia . . . look

what happens to you. Get a grip on yourself, boy» (Martin, 1983: 38). Martin’s

decision to use free indirect style is true to Cronenberg’s own conception:

Lucas, who interviewed the director on set during filming, observes that

«Cronenberg had the notion of making a first-person film that would show an

audience the subjective growth of the hero’s madness» (1983: 34). As Cronenberg

himself described it: after the first 40 minutes of conspiratorial plot, the

viewer suddenly finds himself within «a relentlessly first-person point of

view» (Rodley, 1992: 94). The use of free indirect speech, together with

ekphrastic visualization, thus ensure that the reader is continually exposed to

the contagion of Max’s hallucinatory world.

6. THE MEDIATED

REAL

«After

all there is nothing real outside our perception of reality», O’Blivion’s video-ghost tells Max. As we read the novel and

as we watch the film, it is difficult to say at what exact moment Max’s

hallucinations begin to seep into the narrative world, turning reality into

television-dream. After Max watches the first «Videodrome»

transmission recorded by his assistant, he begins to experience a series of

visceral visions. A suggestive example is the scene, early in the novel/film,

where Nicki Brand arrives at Max’s apartment and they watch a videotape

recording of «Videodrome».

A

woman is being tortured by two masked men in a basement-like room with a red

clay wall; while the muted violent imagery plays in the background, «as

ubiquitous now as electric wallpaper», Max and Brand have sex, and something

strange begins to happen:

He

lifted from her and saw now the pools of condensation forming like heat mirages

around the cushions. The floor melted and sloshed with

electrified water. The dark walls of his apartment seemed to close in, the

ceiling lowering, reflecting the flickering of the candles like the

phosphors of a television image: warm, deeper than orange, and finally

red as a darkroom. The sofa and furniture blurred into insubstantial

shadows, then fell away completely, leaving them naked under the light

of the red room (my italics, Martin, 1983: 71).

So

strong is this sensation of finding himself inside the room shown in the «Videodrome» recording that Max expects to hear «the

slogging approach of heavy boots [of the torturers]. But they did not come. Not

this time» (Martin, 1983: 72).

In

Webb’s characterization, ekphrasis «evokes sights, sounds and sensations of

absent things that, moreover, have the power to make us feel “as if” we can

perceive them and share the associated emotions» (2016: 168). The ekphrasis of

Max’s hallucinatory vision, with his bedroom taking on the quality of a

televised image, is similarly synesthetic: words like «heat», «melted», «sloshed»,

«flickering», «warm», «blurred» and «light» invoke touch, hearing and vision,

imitating verbally the multisensory immersion of TV. «Television», McLuhan

writes, «demands participation and involvement in depth of the whole being»

(2008: 125), which is exactly what ekphrasis tries to make possible in the

novel.

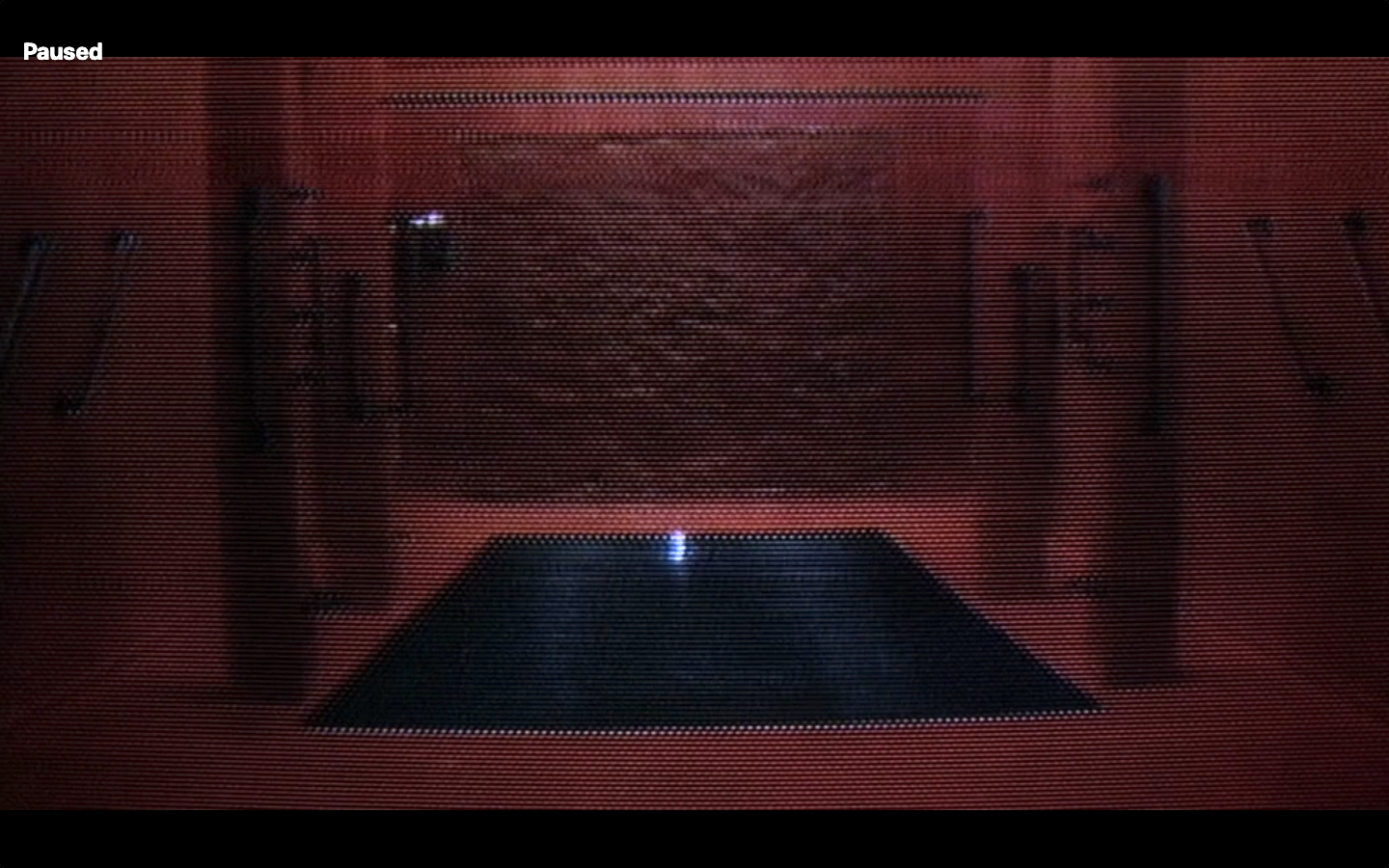

In

the film, Cronenberg portrays this kind of «involvement in depth»

characterizing this scene by a juxtaposition of two distinct images. First, we

see a long shot of Max and Nicki Brand in bed, with the TV set showing the «Videodrome» imagery in the background. Then the scene

changes: Max and Brand are no longer in his bedroom but in a room resembling

the «Videodrome» torture-chamber. The dark crimson

floor and black rectangular space upon which the figures lie, accompanied by

Howard Shore’s brooding soundtrack, create an eroticized, threatening

atmosphere: we’re inside Max’s mind, in a cinematic equivalent of ekphrastic

visualization, for what we are here given to see is the world fallen prey to,

and dominated by, the iconography of televised reality. As if to underscore the

point, the film then cuts, briefly, to a long shot of the same space but now

without the two bodies: the room is shown through the mesh of the CRT screen,

which, in effect, tells us that Max’s world belongs to television (see fig. 4).

Shaviro captures the idée fixe expressed in this

scene, which also characterizes Videodrome as

a whole: «The point at which subjective reality becomes entirely hallucinatory

is also the point at which technology becomes ubiquitous, and is totally melded

with and objectified in the human body» (2006: 141).

We

begin to see more clearly how the effect of ekphrasis, as it is used in

Martin’s adaptation of the film, mirrors McLuhan’s account of the impact of

television, as it is portrayed cinematically by Cronenberg. The conception of

communication upon which ancient rhetorical practice was based—and which, I

claim, is shared by McLuhan—is one where language is conceived «as a

quasi-physical force which penetrates into the mind of the listener, stirring

up images that are stored there» (Webb, 2016: 128). When reading ekphrastic

prose, Webb observes, we experience «language passing like an electrical

charge» between the text and the reader; ekphrasis, moreover, can even lead to

the temporary «enslavement» of the listener by the speaker (2016: 129). If all

these points are taken together, it would seem as if antiquity’s conception of

ekphrasis foreshadowed McLuhan’s theory of media as the «extensions of man»,

not least his account of television as «the most recent and spectacular

extension of our central nervous system» (2001: 345).

Videodrome the novel and Videodrome the film express,

respectively, the visualization made possible by synesthetic description and

the cinematic rendering of conceptual metaphors. In doing so, they point to how

the two media, writing and cinema, form an inseverable part of our picture of

the real and the space we occupy within it via their mediation.

7. A MCLUHANESQUE

PLOT

Having

examined how Videodrome can be said to have

appropriated McLuhan’s theoretical concepts, both in dialogue and cinematic

image, I would like to address my claim that the film’s plot echoes the

discussion of television in Understanding Media. The chapter McLuhan

devotes to TV is by far the longest in the book; it is also where his language

is most Cronenbergian. Beginning the chapter with an image of a child gazing

raptly at a TV screen and concluding with the grisly broadcast of the murder of

Lee Harvey Oswald by Jack Ruby, McLuhan portrays television as an uncanny

medium-intruder into the home that affects society insidiously and unawares.

Contrasting the more linear thought-processes associated with print culture, he

writes: «The introspective life of long, long thoughts and distant goals, to be

pursued in lines of Siberian railroad kind, cannot coexist with the mosaic form

of the TV image that commands immediate participation in depth and admits no

delays» (2001: 354). In McLuhan’s depiction, we are presented with the full

immersion of consciousness «inside» TV, with the mind enveloped in and touched

by its bluish glow. It is important to emphasize here that McLuhan does not

consider television to be pernicious qua medium; media, after all, are tools

which can be used for both virtuous and vicious purposes. McLuhan’s point is

that media, conceived as «extensions» of the central nervous system,

necessarily alter «our sense-lives and our mental processes» (2001:

362).

If

the chapter devoted to television in Understanding Media can be said to

have plot, then it might be summed up as follows: the story begins (like Videodrome) in the intimate interior of the home: a

child is mesmerized by the moving pictures on the tube which come to affect the

way the child processes information, even how she perceives space. Television

is then shown to influence the grown-ups’ world: fashion, clothing, cars,

lifestyle, politics, even daily routines. From the time of the Renaissance—a

period encompassing the invention of the printing press as well as the

perfection of perspective in painting—the Western mind was encouraged to

conceive the world visually: one beheld a uniform space upon which

objects appeared in various configurations and, crucially, one remained

separate from this space in beholding it. Television, on the other hand, in

projecting and extending the sense of touch, «is total, synesthetic, involving

all the senses», immersing the viewer in what she is watching (McLuhan, 2001:

365). Television is so involving, in fact, that it can compel the viewer to

lose his own individuality as he identifies with ritualized audience

participation: the television viewer is content to commit to the «tribe» of the

audience (McLuhan, 2001: 366). It would be wrong, however, to suppose that TV

breeds passivity; as McLuhan argues: «TV is above all a medium that demands a

creatively participant response. The guards who failed to protect Lee Oswald

were not passive. They were so involved by the mere sight of the TV cameras

that their lost their sense of their merely practical and specialist task»

(2001: 368). McLuhan is being ironic, of course: the guards did not act

appropriately precisely because they were already «acting» in the spectacle of

the scene that the TV cameras were in the process of creating.

In

Videodrome, Max’s trajectory as a character

can be seen to mirror the story of television as sketched by McLuhan. His is a

transformation from somebody who programmes (and, of course, avidly consumes)

late-night television content to somebody who becomes programmed by the «Videodrome» signal. O’Blivion

reveals to Max (via television) the hidden truth behind «Videodrome»:

it turns out that being exposed to the transmission induces a brain tumour,

which causes the visceral hallucinations. After watching «Videodrome»,

Max begins seeing a series of increasingly violent visions, eventually acting

them out and murdering two colleagues at CIVIC TV, his assistant Harlan, and

ultimately Barry Convex, CEO of Spectacular Optical, a nefarious enterprise

which seeks to use «Videodrome» to control society.

(«We make inexpensive glasses for the Third World and missile guidance systems

for NATO. We also make Videodrome», Convex

blithely informs Max.)

In

a suggestively titled chapter, «The Gadget Lover», McLuhan writes: «Man

becomes, as it were, the sex organs of the machine world, as the bee of the

plant world, enabling it to fecundate and to evolve ever new forms» (2001: 51).

McLuhan’s reproductive metaphor is given memorable expression in the film’s

visual aesthetic, obsessed as it is by the idea of coupling with technology and

losing the ability to distinguish between self and medium, so that the self becomes

the medium through which those in control can act (see fig. 5). In such imagery

as Max’s infamous flesh gun, the breathing video cassette, the vein-streaked TV

set, and, most spectacularly of all, the animate vaginal slit in Max’s belly, Videodrome gives flesh to McLuhan’s metaphor-fuelled

concepts by «overliteralizing» them, in Shaviro’s phrase; in doing so, the film makes palpable for

the viewer what the reader of Understanding Media and The Medium is

the Massage is left only to imagine. «The TV image», McLuhan writes, «is

[…] a ceaselessly forming contour of things limned by the scanning-finger. The

resulting plastic contour appears by light through, not light on, and the image

so formed has the quality of sculpture and icon, rather than picture» (2001:

341). As we have seen, McLuhan repeatedly emphasized the tactility of

television[9] and the way in which Cronenberg conveys this in the film is i) by means of ingenious prosthetic make-up such as the

scene of Max's kissing the television lips of Nicki Brand, or the explosive

shot of the flesh-gun stretching the TV screen as Max shoots himself by

shooting at the screen; and ii) by filming the TV screen in extreme close-up

and simulating the effect of sitting «in front of the tube» in one’s own living

room.

Seeing

a giant close-up of a TV screen in a movie theatre is not a little

disconcerting. One reason for this is the fact of being confronted with the

medium itself: in seeing a close-up of Bridey’s televised face, at the

beginning of the film, or in looking at the close-up of Max pointing the

flesh-gun at his temple through the mesh of TV, we attend to the texture of the

medium as much as, or even more so, than we do to the content of what we are

shown. What is significant about these scenes is precisely the fact that they

show televised-images lending their content a kind of patina of tactility. The

film’s closing scene presents us with two versions of the same shot: we first

see a close-up of Max’s face with the flesh-gun raised to his temple on the «Videodrome» TV set; then, in the final shot, the same

close-up is used but this time without the «filter» of the TV screen[10]. The unexpected effect of this

is that, instead of the latter shot seeming more «real» than the former, it is

actually the televised close-up that bears the weight of the tangible: in

seeing Max shoot himself on the «Videodrome» set,

which explodes in a spray of guts, we feel as though his fate has already been

sealed. Max has become television: the living word, the film’s metaphor for the

human, has become the New Flesh.

8. CONCLUSION: AN

ADVENTURE IN «THE UNIFIED SENSORIUM»

McLuhan

insisted that what distinguished the image on television from the cinematic

image is the former’s low resolution: the TV image, unlike the light captured

on film stock, is an easily discernible «mosaic mesh of light and dark spots»

(2001: 342). He believed that should television one day improve to the point of

what we now know as HD-quality, we will no longer be dealing with the medium of

television. Yet McLuhan’s account of the television of the 1960s is arguably

even more fitting as an anticipation of the medium’s evolution into the

interactive touchscreen that presently dominates the globe. «In television

there occurs an exploration of the sense of active, exploratory touch which

involves all the senses simultaneously»: if we substitute «smart phone» for «television»

here we can see how prophetic McLuhan could be, however inadvertently.

Today,

the Internet, encompassing social networks and data streaming services, is

something we consume (and something that consumes us) bodily, as we cradle

screen-content in our hands and touch it with our fingers. «Cronenberg was able

to foretell our electronic evolution», Nick Ripatrazone

argues, «the quasi-Eucharistic way we «taste and see» the Internet […] Videodrome shows what happens when mind and device

become one» (2017). Recent advancements in communications media bespeak the

contemporary relevance of McLuhan’s vision of the impact of television on

consciousness. However, as eloquent and far-seeing as that vision is, it is

constrained by its own medium of expression: the linear printed word which

houses this thought. Cronenberg, I have argued, translates that linearity into

cinematic image, hyperbolizing McLuhan’s metaphors of sensory extension as

grotesque mise en scène.

In this way, Cronenberg’s film «adapts» the viewer to McLuhan’s picture of the

violent impact of media on consciousness.

When

Max is taken to see Barry Convex at the headquarters of Spectacular Optical, he

is shown the enterprise’s latest invention (see fig. 6): a glowing helmet

contraption that looks like an eerie prototype of a contemporary VR headset

(recently rebranded as a «mixed-reality» spatial computer). The helmet, Convex

explains to Max, does two things. First the wearer is shown scenes of violent

and/or sexual imagery intended to overstimulate the nervous system: the violent

footage triggers hallucinations, which the helmet then records. The helmet thus

becomes a repository of its wearers’ most secret desires and dreams, dreams

that become the property of Spectacular Optical, which broadcasts them via the «Videodrome» signal. What may have seemed like wide-eyed

dystopian fantasy in 1983 has become reality. Contemporary AI technology is

already capable of reproducing high quality images from an MRI scan of brain

activity: a subject is shown a picture of an animal, for example, and the AI

system translates the neuronal glow detected by the MRI into a more or less

accurate digital reproduction of the original image[11].

As

impressive as the film’s imaginative anticipation of technological innovation

is, it does not capture what is most significant about Cronenberg work. Recall

the director’s remark: cinematic imagery is important, he says, when it has «metaphorical

weight»; for McLuhan, similarly, «All media are active metaphors in their power

to translate experience into new forms» (2001: 63). Showing us how one medium

(television) impinges on consciousness, Cronenberg’s film has metaphorical

weight in precisely this sense: it shows the viewer how media translate and

adapt sensory experience and thereby change us into new forms—often in the most

brutal and perversely stimulating way possible.

Cronenberg,

I think, would be sympathetic to McLuhan’s claim that «not even the most lucid

understanding of the peculiar force of a medium can head off the ordinary “closure”

of the senses that causes us to conform to the pattern of experience presented»

(2001: 359). «Print asks for the isolated and stripped-down visual faculty»,

whereas today we find ourselves within «the unified sensorium» (McLuhan, 2001:

336) of the world of haptic screens. If ekphrasis sought to make the reader a

virtual witness to what was being described, as if the reader could forget the

language-screen making the description possible in favour of the visions

immanent within it, then the image in Videodrome

asks the viewer to remember the living word before, or even as, it becomes the

New Flesh. It may be impossible to extricate ourselves from the media which

compose the texture of reality, yet it is possible, as both Videodrome

the novel and Videodrome the film attest, to

portray the texture’s weave.

IMAGES

Fig. 1. Marshall McLuhan leans on his own televised

image. Photograph by Bernard Gotfryd, 1 January 1967.

Public domain.

Fig. 2. Jack Creley as Professor Brian O’Blivion, McLuhan’s stand-in in Videodrome

(David Cronenberg, 1983).

Fig. 3. Max Renn (James Wood) kisses and fondles the

television screen (David Cronenberg, 1983).

Fig. 4. Max Renn’s bedroom portrayed as a televised

image of the torture-room in the «Videodrome»

transmission

(David Cronenberg, 1983).

Fig. 5. The flesh-gun suicide on the «Videodrome» TV set shown in the film’s closing sequence

(David Cronenberg, 1983).

Fig. 6. Max Renn wearing the helmet that records

dreams (David Cronenberg, 1983). BIBLIOGRAPHY Bilmes, Leonid (2023), Ekphrasis,

Memory and Narrative after Proust, London, Bloomsbury Academic. Bolter, Jay David (1996), «Ekphrasis, Virtual Reality, and the Future of

Writing», in G. Nunberg (ed.), The Future of the Book, Berkeley, University of

California Press, pp. 253-273. Bortzmeyer, Gabriel (2021), «Métastases Médiatiques: David

Cronenberg lecteur de Marshall McLuhan», Débordements

[Online: https://debordements.fr/Metastases-mediatiques/. Accessed 31/1/2024]. Browning, Mark (2007), David Cronenberg: Author or Film-maker?, Bristol, Intellect Books. Clüver, Claus (2017), «Ekphrasis and Adaptation», in T. Leitch (ed.), The

Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp.

459-477. Debord, Guy (2005), Society of the Spectacle, trans. by K. Knabb,

London, Aldgate Press. Genette, Gérard (1997), Palimpsests. Literature in the Second Degree,

trans. by C. Newman and C. Doubinsky, Lincoln, University of

Nebraska Press. Gonzáles-Fierro Santos, José Manuel (1999), David

Cronenberg. La estética de la carne, Madrid, Nuer Ediciones. Gorostiza, Jorge and Ana Pérez

(2003), David Cronenberg, Madrid, Catédra. Grünberg, Serge (2006), David Cronenberg: Interviews

with Serge Grünberg, London, Plexus. Leitch, Thomas (2012), «Adaptation and Intertextuality, or, What isn’t an

Adaptation, and What Does it Matter?», in D. Cartmell

(ed.), A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation, Chichester,

Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 87-105. Louvel, Liliane (2018), «Types of Ekphrasis: An Attempt at Classification», Poetics

Today, 39/2, pp. 245-263. Lucas,

Tim (2010), «Medium Cruel: Reflections on Videodrome»,

Criterion [Online: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/676-medium-cruel-reflections-on-videodrome. Accessed: 8/2/2024]. Lucas,

Tim (2008), Videodrome: Studies in the

Horror Film, Lakewood, Centipede Press. Lucas,

Tim (1984), «Videodrome: Filming One of the

Genre’s Most Original and Cerebral Stories in Years», Cinefantastique

14/2, pp. 32-49. Martin, Jack (1983), Videodrome, New York,

Zebra Books. McLuhan, Marshall and Quentin Fiore (2008),

The Medium is the Massage, London, Penguin Books. McLuhan, Marshall (2009), «The Playboy Interview», Playboy Magazine 03.1969

[Online: https://nextnature.net/story/2009/the-playboy-interview-marshall-mcluhan. Accessed: 20/3/2024]. McLuhan, Marshall (2001), Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man,

Abingdon, Routledge. Rodley, Chris (1992), Cronenberg on Cronenberg, Toronto, Alfred A.

Knopf Canada. Pearson, Brook W.R. (2012), «Re(ct)ifying Empty Speech: Cronenberg and the Problem of the

First Person», in Simon Riches (ed.), The Philosophy of David Cronenberg,

Kentucky, The University Press of Kentucky, pp. 155-175. Ripatrazone, Nick (2017), «The Video Word Made Flesh: Videodrome

and Marshall McLuhan», The Millions [Online: https://themillions.com/2017/04/the-video-word-made-flesh-videodrome-and-marshall-mcluhan.html. Accessed: 16/2/2024]. Ruberg, Sarah and Jacob Ward

(2023), «From brain waves, this AI can sketch what you’re picturing», NBC

News [Online: https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/brain-waves-ai-can-sketch-picturing-rcna76096. Accessed:

20/3/2024]. Russo, Eduardo (2017), «David Cronenberg y el cuerpo:

medio y dispositivo en Videodrome y eXistenZ», diCom [Online:

https://maestriadicom.org/articulos/david-cronenberg-y-el-cuerpo-medio-y-dispositivo-en-videodrome-y-existenz/. Accessed: 15/2/2024]. Sanders, Julie (2016), Adaptation and Appropriation, Abingdon,

Routledge. Shaviro, Steven (2006), The Cinematic Body, Minneapolis, University of

Minnesota Press. Stam,

Robert (2000), «Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of

Adaptation», in James Naremore (ed.), Film

Adaptation, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, pp. 54-76. Webb,

Ruth (2016), Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion in Ancient Rhetorical

Theory and Practice, Abingdon, Routledge. Fecha

de recepción: 21/03/2024. Fecha de aceptación: 24/05/2024.