Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

ABSTRACT

In light of the intense information disorder that has ensued since the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic, the aim of this study is to analyze the similarities and differences between the disinformation circulating in three countries, based on the posts of their pioneering fact-checking organizations: Agência Lupa (Brazil), Newtral (Spain), and Jornal Polígra- fo (Portugal). A quantitative and qualitative content analysis (Bardin, 2011) was run on the fact checks (n = 87) performed by the three organizations in March 2021, 12 months after the pandemic had been declared by the World Health Organization, using the analytical categories “classification”, “medium”, “format”, “source”, and “topic”. The disinformation identified in the three countries shared three similarities, namely, a predominance of false content, the primary use of text formats, and the dissemination of disinformation on social media platforms. As to the sources cited and subject matter, differences were found in the strategies employed to validate the disinformation and in the topics covered. It can be concluded that while the pandemic was a global phenomenon, the disinformation circulating about it was influenced by the political, social, and cultural particularities of each country.

Keyword: Disinformation, COVID-19, infodemic, fact-checking, Ibero-America, content analysis

RESUMEN

En medio de la crisis de salud de la COVID-19, hemos estado experimentando un intenso desorden informativo. En ese contexto, nuestro objetivo en este estudio fue analizar las similitudes y diferencias entre los contenidos desinformativos que circularon en tres países del espacio iberoamericano, a través de las plataformas fact-checking pioneras en sus lugares de origen: Agência Lupa (Brasil), Newtral (España) y Polígrafo (Portugal). Seleccionamos las verificaciones realizadas en marzo de 2021, doce meses después del anuncio de la pandemia por parte de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Un total de 87 documentos fueron explorados cuantitativa y cualitativamente bajo el prisma del análisis de contenido (Bardin, 2011) y por medio de cinco categorías analíticas: clasificación, plataforma de servicio, formato, fuente y tema. Tres aspectos presentaron similitudes: predomina el contenido falso, en formato de texto y circula por las redes sociales. Entre los tipos de fuentes y los temas, se observaron diferencias en las estrategias de validación del contenido desinformativo y en los temas tratados. Concluimos que, aunque la pandemia es un fenómeno global, la desinformación responde a especificidades de los contextos políticos, sociales y culturales de los distintos países.

Palabras clave: Desinformación, covid-19, infodemia, fact-checking, Iberoamérica, análisis de contenido

1. Introduction ↑

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (hereinafter WHO) declared the novel coronavirus (hereinafter COVID-19) a global pandemic. As societies gradually became aware of the new disease there was a veritable explosion of information in the field of communication, spearheaded by digital media, in terms of its immediacy and scope. The ensuing infodemic (WHO, 2018) associated with the pandemic was instrumental in the spread of unfounded rumours, false information, and inaccurate news about the disease and its causes, symptoms, treatments, and prevention. Disinformation became a major threat to public health efforts and to the acceptance of scientifically proven measures for controlling the virus by some sections of society (Cinelli et al., 2020).

Disinformation has been an object of study since the mid-twentieth century (Romero Rodríguez, 2013). However, the new information ecosystem emerging since the turn of the twenty-first century, marked by the popularization of online communication platforms and social media, has raised the phenomenon to new heights. The idealized view of a hyperconnected world enabled by digital technologies, democratizing access to information, has swiftly been replaced by the recognition of a scenario of growing information disorder conducive to the circulation of extreme content, conspiracy theories, rumours, and decontextualized, manipulated, or even intentionally false information (Wardle, 2019).

Some authors have adopted the concept of fake news to refer to such intentionally and verifiably false content, designed to undermine the credibility of the news by imitating its formats and lan guages (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Tandoc Jr., 2019). Despite having a news-like appearance, such content is not produced in accordance with the norms, values, or intentions traditionally associated with journalistic output (Lazer et al., 2018). For Allcott and Gentzkow (2017), the production of fake news is driven by both commercial and ideological motivations. From a financial point of view, fake and sensationalist news makes a splash and drives clicks and views, which are then converted into advertising revenues. From an ideological perspective, fake news may be associated with extreme positions and designed to bolster or discredit certain stances, actors, or social institutions. Nonetheless, it is important to note that in the broader context of information disorder, as Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) call it, entirely fabricated content circulates alongside other information that may be intentionally decontextualized, distorted, or misleading. The concept of disinformation, therefore, encompasses a broad spectrum of content associated with a variety of communication dynamics linked to its production, reception, and circulation.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic there has been an unprecedented increase in the production and circulation of disinformation. Some studies indicate that pandemic-related disinformation in Latin America tends to have political overtones and may even be actively spread by public figures (Ceron et al., 2021; Quintana Pujalte & Pannunzio, 2021; Recuero et al., 2021; Soares et al., 2021). Disinformation should therefore be understood as a set of practices implemented in a broader cultural scenario in which different social actors vie with one another in establishing the meaning of different phenomena which, when thoroughly analysed, reveal a debate not so much on public health or scientific issues as on particular political or ideological stances (Oliveira, 2020a).

Several strategies have been adopted to combat the proliferation of disinformation and to promote a more informed public debate. One such initiative, fact-checking — a set of procedures used by journalists to ensure the accuracy of the information that they publish (Graves et al., 2016) — has been increasingly adopted by news outlets and scientific and civil society organizations in several countries. This phenomenon has been explored in a number of studies, which have observed the evolution and trends in pandemic-related disinformation. Brennan et al. (2020), for example, analysed English-language fact checks conducted between January and March 2020, demonstrating that there was more distorted and decontextualized information about COVID-19 than the completely false kind. For their part, López-García et al. (2021) monitored the work of fact checkers in Spain, finding that fake news on mask wearing and diagnostic testing not only persisted, but gradually became more elaborate, incorporating, for example, the use of scientific terminology and adapting to different media contexts.

It is worth noting, however, that the work of official fact-checking organizations does not cover every kind of disinformation, since they all follow their own criteria for selecting the content that they deem relevant and “checkable”. Nevertheless, focusing on their work is a viable analytical methodology considering the growing importance of fact-checking in the fight against disinformation and the feasibility of collecting and analysing data from these sources. Investigating specific cases published by fact-checking organizations may therefore offer important inputs for understanding the infodemic prevailing during the pandemic.

Against this backdrop, the aim here is to investigate the characteristics of the disinformation circulating in different political, cultural, and media contexts, especially in Ibero-America. While it can be assumed that the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting disinformation have raised similar concerns among populations the world over (Salaverría et al., 2020), this study is based on the assumption that discourses grounded in disinformation may differ across countries. Accordingly, it analyses the similarities and differences between disinformation in three countries based on information reviewed by fact-checking organizations. To this end, a series of fact checks conducted by Agência Lupa (Brazil), Newtral (Spain), and Polígrafo (Portugal) were analysed. They were chosen because of their status of pioneers in their respective countries and their links to prominent international initiatives, such as the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) 1 and Facebook’s Third Party Fact-Checking Project 2.

For this study, the COVID-19-related fact checks conducted by these three organizations in March 2021, one year after the WHO officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, were selected. Inspired by content analysis (Bardin, 2011), a methodology was developed to assess, both quantitatively and qualitatively, different aspects of the fact-checked disinformation, such as the formats employed, the sources cited to legitimize it, the media used to spread it, and the most recurrent topics.

As such, despite the differences between the news contexts in each country and the way in which each fact checker organizes and goes about its work, the analysis offers comparable data that allows for determining similarities and differences between the pandemic-related disinformation fact checked in the three countries. This research is thus justified by the need to gain a better understanding of the disinformation landscape in Ibero-America, its transnational trends, and the specific characteristics of each national scenario. Further insights into the “glocal” nature of the phenomenon of disinformation could provide valuable inputs for any strategy designed to combat information disorder and to promote media and scientific literacy.

1.1. (Dis)information in Brazil, Portugal, and Spain: some background information

Despite their socioeconomic and cultural differences, Brazil, Portugal, and Spain have a high percentage of Internet users: 74 %, 78 %, and 93 %, respectively 3. According to the Digital News Report 2020 (Newman et al., 2020), social media serve as information sources for 56 % of users in Spain, 58 % in Portugal, and 67 % in Brazil. In addition, in all three countries Facebook, YouTube, and WhatsApp are the social media most widely used for keeping abreast of the news. These media not only facilitate the rapid spread of essential science and health information, but also accelerate that of disinformation, which might have undermined the efficacy of initiatives designed to contain the propagation of the new coronavirus (Cinelli et al., 2020).

Brazil is a particularly significant case. Recuero et al. (2021) and Soares et al. (2021) have found a strong engagement with false COVID-19-related content on social media and messaging apps. By and large, this kind of content chimes with far-right discourses, as well as framing the pandemic in a political, rather than public health, context. Since the beginning of the health crisis, the country’s government has tended to play down the severity of the disease and to oppose preventive measures, such as social distancing and mask wearing (The Lancet, 2020), while advocating for the use of drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, whose effectiveness against COVID-19 has yet to be proven. This attitude has also permeated the public debate on social media. In 2020, when the debate on these drugs had started to ebb in most countries, disinformation on their use against COVID-19 continued to circulate in Brazil (Machado et al., 2020; Monari et al., 2020).

The failure of the different authorities to engage in coordinated action to combat the virus and the spread of disinformation on social media contributed to the country becoming one of the epicentres of the disease, with over 600,000 confirmed deaths by October 2021 (Diele-Viegas et al., 2021). By December 2021, 8.1 % of all cases and 11.5 % of all COVID-19 deaths worldwide 4 had occurred in Brazil, despite the fact that the country accounts for only 2.7 % of the world’s population 5.

The situation in Portugal was somewhat different. From the outset, the government spearheaded the fight against COVID-19, managing to gain the citizenry’s support for self-isolation. The easing of these measures as of October 2020, however, paved the way for an escalation in the number of daily cases, pushing the country’s health system to the brink of collapse (Costa, 2021). By December 2021, the country had recorded 1.22 million cases and 18,800 deaths from the disease 6. The situation was gradually turned around thanks to the efficiency of the country’s vaccine rollout. By the end of 2021, Portugal had completely immunized 86 % of its population and 100 % of its citizens aged over 50, thus making it one of the most vaccinated countries in the world 7. Nonetheless, there was a significant amount of COVID-19-related disinformation on social media, especially first-hand accounts of purported health specialists and conspiracy theories, as well as the appropriation of the pandemic for political ends (Cardoso et al., 2020; Moreno et al., 2021).

For its part, Spain was one of the first countries to feel the brunt of COVID-19 (Domínguez-Gil et al., 2020). In March 2020, when Europe became the epicentre of the pandemic, it was country with the second highest number of confirmed cases, before reaching first place in April and May (Pérez-Laurrabaquio, 2021). Since then, there have been at least five waves of COVID-19, the last, associated with the Delta variant, occurring between June and September 2021 (Iftimie et al., 2021). By December 2021, the country had recorded 5.45 million cases and 88,700 deaths 8.

In Spain, several studies have pointed to the importance of closed networks, such as Facebook and WhatsApp groups, in the spread of false information (Fernández-Torres et al., 2021; Salaverría et al., 2020). In addition, in a study of information verified by Spanish fact-checking organizations Salaverría et al. (2020) observed that the disinformation on the pandemic and its discursive exploitation for political purposes were, thematically speaking, remarkably diverse.

In all three countries, different researchers have traced the trends in disinformation based on the work of fact-checking organizations (Brennan et al., 2020; Salaverría et al., 2020; López-García et al., 2021), providing a valuable opportunity for performing a comparative study on disinformation in the aforementioned scenarios.

2. Methodology ↑

In order to create a corpus for meeting the research objectives, content was gathered from a sole fact-checking organization in each one of the three countries — Agência Lupa (Brazil), Newtral (Spain), and Polígrafo (Portugal) — and then analysed. The methodology comprised three stages, as proposed by Bardin (2011), to wit, pre-analysis, exploration of the material, and treatment of the results. The combination of qualitative and quantitative analytical techniques in this approach allowed for the systematization and classification of diverse and sometimes contrasting content, with an eye to inferring issues relating to its production and reception.

The pre-analysis involved selecting and organizing the corpus, based on fact checks posted on the websites of the three organizations between March 1 and 31, 2021, the time frame chosen to analyse quantitatively and qualitatively the disinformation one year after the WHO had declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic. The aim was to examine how disinformation might have related to the evolution of COVID-19, as well as to sociopolitical and media developments in each country, with a view to performing a comparative analysis on the infodemic’s yearly progression in future studies.

Firstly, a total of 291 fact checks — 66 from Lupa, 62 from Newtral, and 163 from Polígrafo — were identified. All the information that was unrelated to the pandemic and classified as true was then discarded, leaving a corpus comprising 87 — 36 from Lupa, 25 from Newtral, and 26 from Polígrafo — fact-checked news items.

In the second stage, after data collection, five categories based on the research objectives were established. For each category, the codes pertinent to the research objectives and the analytical categories were systematized, which enabled the different researchers involved to develop similar and comparable results. Based on the proposals of Sampaio and Lycarião (2021), a spreadsheet was generated with the data obtained, which was then used for running the reliability tests and performing the final coding. The categories and their coding are described in table 1.

In the final stage, a quantitative and qualitative analysis was performed on the content retrieved from Lupa (Brazil), Newtral (Spain), and Polígrafo (Portugal), based on the categories described above. As Sampaio and Lycarião (2021) contend, the inferences and interpretations obtained from quantitative analyses allow for identifying the frequency, intensity, and importance of the phenomenon under study. By observing the regularity with which certain characteristics of disinformation appeared in the three countries, it was possible to identify similarities and differences between them. Furthermore, some of the content fell into more than one category, combined different formats, and/or came from more than one source. All these data were considered in the quantitative results and in the final percentages.

TABLE 1

| Category | Description | Coding |

| Classification | Labels used to identify the fact-checked content | Categories established by each organization to indicate the degree of veracity of the information in question – including the false, contradictory, unsubstantiated, etc., kind |

| Medium | Platforms and channels through which the disinformation circulates | Content classified according to the medium from which it was retrieved, including social networks, messaging apps, TV broadcasts, etc. |

| Format | Language and codes used to present the disinformation | Content classified as texts, images, videos, cards, infographics, etc., or a combination of one or more of these codes |

| Source | Actors and institutions leveraged by the producers of the disinformation to give it a sheen of legitimacy | Presence or absence of an alleged source and its type, such as scientific, political, expert, media, testimonial, etc. |

| Topic | Subjects and topics addressed | Presence of keywords for discussing topics such as vaccines, numbers of cases and deaths, treatments for COVID-19, etc.TABLE 1 |

Analytical categories.

TABLE 2

| Lupa (Brazil) | Polígrafo (Portugal) | Newtral (Spain) | |||

| False | 76.9 % | False | 73.1 % | False | 96.0 % |

| True, but... | 7.7 % | Imprecise | 15.4 % | Misleading | 4.0 % |

| Overstated | 7.7 % | Decontextualized | 7.7 % | ||

| Too soon to say | 3.8 % | True, but ... | 3.8 % | ||

| Contradictory | 1.9 % | ||||

| Keeping watch | 1.9 % | ||||

Breakdown of the information fact checked by Lupa, Polígrafo, and Newtral into different classifications.

3. Results and discussion ↑

The content analysis involved observing the way in which the three fact-checking organizations classified the different kinds of disinformation, ranging from “true” to “false”. In Brazil, Lupa uses nine classifications: “True”, “True, but …”, “Too soon to say”, “Overstated”, “Contradictory”, “Underestimated”, “Unsubstantiated”, “False”, and “Keeping watch”. Meanwhile, in Spain Newtral employs only four: “True”, “Half-true”, “Misleading”, and “False”. Finally, in Portugal Polígrafo uses seven: “True”, “True, but …”, “Imprecise”, “Decontextualized”, “Manipulated”, “False”, and “Trumped up” 9.

Table 2 shows the frequency (%) with which each one of these classifications appeared in the corpus. Despite the differences, “False” was the most used, accounting for 76.9 % of the information fact checked by Lupa, 96.0 % by Newtral, and 73.1 % by Polígrafo.

The predominance of the classification “False” in all three countries, accounting for 80.5 % of the corpus, could be an important indicator of how disinformation on COVID-19 was still being spread one year after the outbreak of the pandemic. This percentage is inconsistent with the data gathered by researchers early on in the pandemic, such as Brennan et al. (2020) who found that 38 % of the information fact checked between January and March 2020 was completely false. This begs the question of why the percentage here was so high, bearing in mind that it might just as well be a reflection of the editorial criteria established by the three fact-checking organizations as that of the current level of disinformation in the countries in question.

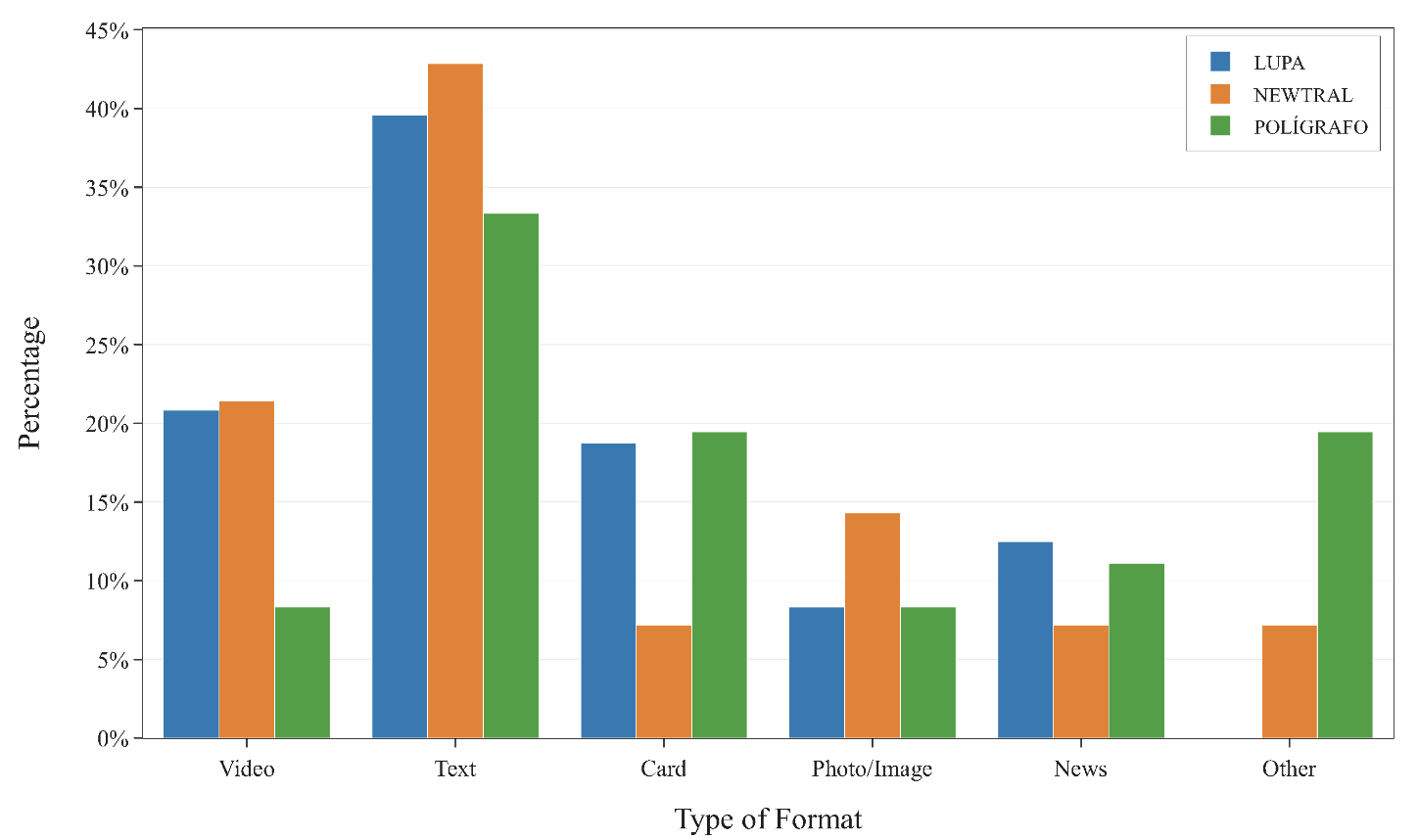

Graphic 1. Types and percentages of the formats of content containing disinformation collected from Lupa (Brazil), Newtral (Spain), and Polígrafo (Portugal).

As to the media through which the disinformation was spread, social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, plus the WhatsApp messaging app, predominated in all three countries. Since it is common for fact checkers not to identify precisely from which digital media the disinformation has been retrieved, all these media were combined in a single category, generically called “social networks”, into which 94.4 %, 92.0 %, and 69.2 % of the content retrieved from Lupa, Newtral, and Polígrafo, respectively, fell.

These results point to the current importance of social networking sites as information sources (Newman et al., 2020). However, their participatory nature also makes them vulnerable to the circulation of inaccurate and distorted information (Chou et al., 2009). In addition, the vast amount of information that they put into circulation tends to lead to an overload, making users more likely to like and share posts without fully reading them (Zago & Silva, 2014). In this scenario, sensationalist news and clickbait headlines are attention-grabbers that can contribute to the spread of disinformation (Chen et al., 2015).

Even so, it warrants recalling that there are other kinds of communication channels through which disinformation can be spread. As regards Lupa, these corresponded to 5.6 % of the total, including a press conference given by the former health minister Eduardo Pazuello and statements made by the Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro both online and at face-to-face events. Moving on to Newtral, 8 % of its fact checks had to do with such contexts, like the statements made by the congresswoman Rosa María Romero Sánchez in a plenary session of the Congress of Deputies and those by the minister of economic affairs Nadia Calviño in an interview on the television news program La hora de la 1. Lastly, as to Polígrafo, 19.2 % of the fact-checked information circulating via channels other than social networks included one blog, two TV programs, one parliamentary debate, and one complaint lodged against the organization. However, it was the only fact-checking organization that published findings without identifying the information source, this being the case in 11.5 % of the sample.

The predominant use of texts to disseminate disinformation might be down to the fact that it is easier to produce content in this format, as it requires less resources and know-how than others, such as images, audio recordings, and videos. Nevertheless, audio-visual content constituted a not insignificant proportion of the corpus, accounting for 20.8 %, 21.4 %, and 8.3 % of the information fact checked by Lupa, Newtral, and Polígrafo, respectively. There were also other formats, accounting for fewer cases, such as questions from readers (11 % in the case of Polígrafo) and statements made by public figures collected directly by the organizations (7.1 %, Newtral, and 8.3 %, Polígrafo). Graph 1 shows the frequency (%) with which the different formats of content fact checked by Lupa, Newtral, and Polígrafo appeared.

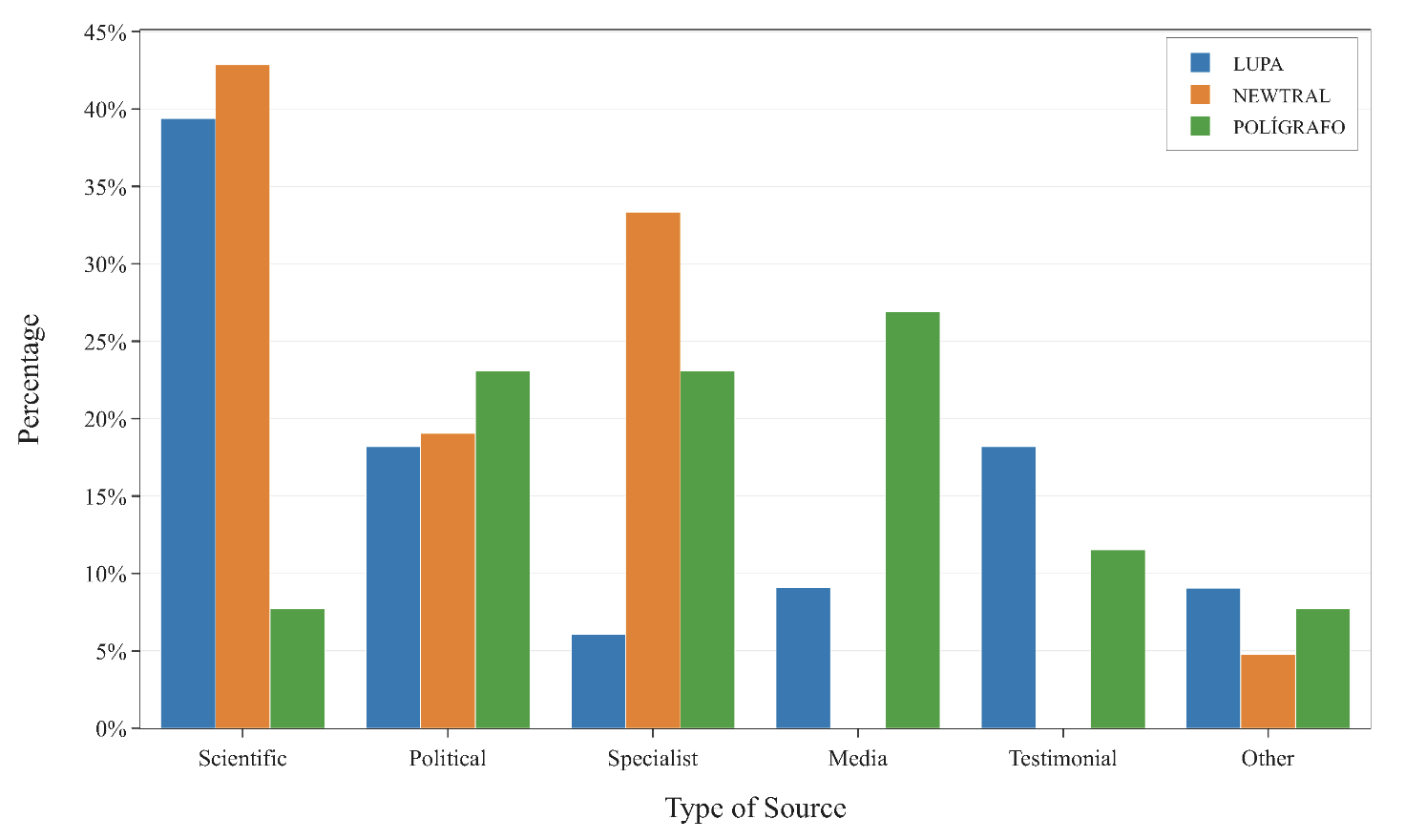

Graphic 2. Types and percentages of sources cited in disinformation fact-checked by Lupa (Brazil), Newtral (Spain), and Polígrafo (Portugal).

In the analysis of the sources — the social actors exploited with the aim of giving the disinformation a sheen of legitimacy — it was found that in 78.1 % of the corpus, false information was attributed to individuals and/or institutions, while in 21.8 % no source was cited, indicating that this is not a prerequisite for information sharing. Graph 2 shows the sources divided into the “scientific”, “specialized”, “political”, “testimonial”, “media”, and “other” categories, for the corpus as a whole, including those cases in which more than one was cited.

The “scientific” sources were institutions or scientists to whom research, discoveries, or recommendations contradicting the current state of the knowledge of the disease were falsely attributed, representing 30 % of the sample. The data suggest that in the midst of an epistemic crisis (Oliveira, 2020b), with the institutions responsible for the production and communication of knowledge coming under fire, the credibility of these actors was undermined by disinformation.

The “scientific” category also includes governmental and multilateral bodies which, despite not engaging directly in research, can be seen as scientific “spokespersons”, offering the citizenry behavioral guidelines aimed at combating the disease. The disinformation containing references to such bodies therefore appropriates their legitimacy so as to enhance its own credibility, as was the case of “#Factchecked: It Is False that the CDC Concluded that Masks do not Prevent Contagion by COVID-19” 10 (Lupa, Mar. 11, 2021), in which the person(s) responsible for the disinformation cite(s) the US health protection agency so as to spread the hoax that mask wearing has a negligible impact on the propagation of COVID-19. In “# Factchecked: It Is False that Research Has Proven the Effectiveness of Ivermectin for Treating or Preventing COVID-19” 11 (Lupa, Mar. 12, 2021), there is a clear effort to reproduce the scientific research style and genre, including the meticulous presentation of supposedly accurate data and graphics and the citation of over 200 sources.

The “specialist” category includes both professionals and organizations in the field of biomedicine, whose authority is also misappropriated to legitimize disinformation. Sources that are classified as “political” comprise elected representatives and public administrators. In a context of information disorder, the circulation of false information about science can be expedited by citing political actors unrelated to the field (Oliveira et al., 2020). Whether in pronouncements, debates, or press statements, figures like these sometimes end up being simultaneously subjects and sources of disinformation, presenting themselves as voices of authority. In Brazil, this perception was heightened by the actions of President Bolsonaro. One piece of information checked by Lupa — “In a statement, Bolso naro changes his tone, but repeats mistruths about vaccination” 12 (Mar. 23, 2021) — he states that the Sinovac vaccine CoronaVac is ineffective, thereby spreading an anti-vax narrative without mentioning any scientific source to substantiate his position.

Sources classified as “testimonials” are ones whose arguments are based on lived/observed experiences, which are employed to lend their discourses credibility. First-person videos showing empty hospitals are disseminated as evidence that the pandemic is a hoax, claiming greater credibility than objective information. This practice also ties in with the aforementioned epistemic crisis, which saw a shift in authority away from scientific parameters towards personal opinions and emotions (Sacramento et al., 2020). This type of source, the second most representative one in the sample from Brazil, was employed by political leaders, such as Bolsonaro himself when defending the use of hydroxychloroquine (ibid.).

It was those sources classified as “media”, including TV stations, newspapers, and informational websites, that were the most cited in the sample from Portugal. In a process analogous to the appropriation of scientific credibility, journalistic authority is leveraged to legitimize content produced without observing the field’s professional standards (Tandoc Jr., 2019). The sources cited ranged from mainstream media to non-professional websites, which tend not to be clear on the editorial criteria followed or the author(s) of the stories (Massarani et al., 2020). The presence of the latter among disinformation sources demonstrates that while the diversification of broadcasters in the contemporary media ecosystem could help to underpin democracy, it could also jeopardize access to quality content. Finally, the “other” category included isolated cases, such as celebrities, a private company, and a business owners’ association.

Lastly, the “topics” category was used to investigate the subjects covered most often in the disinformation fact checked by the three selected organizations. For the most part, each news item containing disinformation covered a single theme, although 11 — five fact checked by Lupa, four by Polígrafo, and two by Newtral — covered more than one. This was the case, for example, of the claim that vaccines were responsible for the increased mortality rate in Israel, in that it was misleading about both their safety and the mortality rate in that country. Curiously, this was also the only case in which the same information was fact checked by all three organizations, albeit with slight variations on the theme: “It is false that the mortality rate in Israel increased after the Pfizer vaccine was introduced” 13 (Lupa, Mar. 5, 2021); “Has the COVID-19 vaccine led to an increase in the mortality rate among the elderly in Israel?” 14 (Polígrafo, Mar. 10, 2021); and “There is no evidence that in Israel the mortality rate among the elderly ‘from vaccines’ is 40 times higher than that from COVID-19” 15 (Newtral, Mar. 15, 2021).

Table 3 shows the topics identified and their respective frequencies (%).

TABLE 3

| Topic | Explanation | Lupa | Newtral | Polígrafo |

| Vaccines | Content on the research into and the production, and administration of vaccines, their side-effects, and the protection that they offer | 29.3 % | 37.0 % | 31.0 % |

| Preventive measures | Content on methods used to combat the pandemic, such as social distancing, mask wearing, etc. | 19.5 % | 37.0 % | 37.9 % |

| Number of cases and deaths | Content that over- or understates the number of cases and deaths caused by the disease | 24.4 % | 11.1 % | 10.3 % |

| Treatment | Content that defends treatments that are not effective for COVID-19 | 14.6 % | 0.0 % | 6.9 % |

| Mismanagement of the pandemic | Content on purportedly inadequate, negligent, or illegal conduct on the part of political actors in the fight against the disease | 4.9 % | 3.7 % | 10.3 % |

| Causative agents | Content on the virus that causes COVID-19 | 2.4 % | 7.4 % | 0.0 % |

| Effects of COVID-19 | Content on the complications, long-term effects, and immunity caused by the disease | 2.4 % | 0.0 % | 3.4 % |

| Other | Content on other issues, such as social welfare, postmortems, etc. | 2.4 % | 3.7 % | 0.0 % |

Topics and frequencies (%) of disinformation in the samples from Lupa, Newtral, and Polígrafo.

As can be seen in table 3, over a year after the outbreak of the pandemic, with vaccination at an advanced stage in all three countries, the primary topic of disinformation was the “vaccines” themselves, accounting for a third of the total. However, the profile of this disinformation varied across the three countries. In Brazil, most of the fact checks performed by Lupa were on content with a pro-vaccine slant, including information on a secret vaccine supposedly produced by a Brazilian research institute, the purchase of fake vaccines on the international market, overstated vaccination numbers, and the alleged concealment of vaccine doses by opponents of the federal government. This finding is consistent with previous studies, in which it was found that pro-vaccine disinformation abounded, namely, stories that accepted the validity of the vaccines, but exploited them for political purposes (Massarani et al., 2020).

Meanwhile, most of the vaccine-related fact checking conducted by Newtral was on openly anti-vax content. In the main, discourses of this nature claimed that vaccines were unnecessary for winning the battle against the pandemic or potentially harmful, associating them with deaths, DNA alterations, and cancer. Anti-vax discourses were also more common among the fact checks conducted by Polígrafo, with arguments like the claim that vaccines could give rise to new coronavirus variants and that they were produced to curb global population growth.

Discourses calling into question the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, based on arguments denying the validity of scientific evidence, were already circulating before the pandemic (Kata, 2012). According to Cuesta-Cambra et al. (2019), individuals with anti-vax attitudes tend to seek information to sustain their pre-existing beliefs, while simultaneously rejecting information that contradicts what they consider to be true. For Kata (2012), anti-vax groups are always putting forward new theories about the harm caused by vaccines, drawing on purportedly solid evidence to support their claims. This could explain the variety of anti-vax arguments in the sample, ranging from genetic mutations to an association between vaccination and death.

Disinformation attacking scientifically proven measures for combating the pandemic was also identified in the corpus, in particular self-isolation, seen as ineffective and harmful to the economy and the citizenry, alike. There were references to the legality and scope of the lockdown rules, above all in the fact checks conducted by Polígrafo, in which disinformation about social isolation represented 22.2 % of the total. For example, it was claimed that hairdressers and beauty salons had been allowed to open and, despite the ban on international travel, that flights had been operated between Brazil and Portugal during the “state of emergency”.

Still on the topic of “preventive measures”, there was also a significant amount of disinformation about masks. A common issue among the information fact checked by Lupa and Polígrafo was the use of old images of political figures without face masks that were passed off as recent. Meanwhile, in Spain there were more misleading stories that associated mask wearing with other diseases, such as pneumonia, cancer, atrioventricular canal defects (AVCs), and dermatitis. Lastly, both of the European fact-checking organizations disclosed disinformation about the PCR tests used to detect the presence of the virus in humans. They generally claimed that PCR testing was ineffective for identifying the presence of COVID-19 and that false positives were inflating the real number of cases.

Stories about the alleged blunders, negligence, or criminal behaviour of government officials were classified as “mismanagement of the pandemic”. On the whole, this type of disinformation was more political than health-oriented, with the aim of criticizing the authorities, examples including false reports of hospital equipment being left abandoned by Brazilian governors and the alleged closure of a hospital in Madrid.

The stories falling into the “number of cases and deaths” category claimed that there was a hidden truth behind the pandemic that only health workers and administrators knew about. One of the disinformation strategies observed was that of playing down the severity of the disease by underestimating the number of cases and deaths, as in “#Factchecked: It is False that Hospital Moinhos de Vento, in Porto Alegre, is not Overcrowded because of COVID-19” 16 (Lupa, Mar. 3, 2021) and “The False Statements Made by Ana María Oliva, the Scientist who Denies Deaths Are Caused by COVID-19” 17 (Newtral, Mar. 5, 2021). There were also others in which it was argued that an intentional effort was being made to increase the death rate, as in “#Factchecked: It is False that there is a Protocol to Lower the Oxygen of Intubated Patients so as to Increase COVID-19 Deaths” 18 (Lupa, Mar. 19, 2021) and “Do Portuguese Hospitals Receive Funding for Declaring Deaths Caused by COVID-19?” 19 (Polígrafo, Mar. 28, 2021).

As regards death rates, some stories claimed that there had been an increase in deaths associated with vaccination, implying that the vaccines were not safe. Examples include “#Factchecked: It is False that Anvisa [Brazilian healthcare regulatory agency] Recorded 26 Deaths Caused by COVID-19 Vaccines in the Last 24 Hours” 20 (Lupa, Mar. 11, 2021); “#Factchecked: It is False that 30 % of People Vaccinated against COVID-19 Will Die in Three Months” 21 (Lupa, Mar. 24, 2021); and “Does the Number of COVID-19 Deaths ‘Beat All Records’ in Countries that ‘Vaccinate More’?” 22 (Polígrafo, Mar. 30, 2021). In these cases, they were included in both the “vaccines” and “number of cases and deaths” categories.

Lastly, news stories relating to the “Treatment” category, especially those covering drugs such as hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, were only found in Brazil and Portugal. In addition, Lupa identified false information on homemade inhalation remedies made with baking soda, bleach, or hydrogen peroxide, as was stated in a study of the hoaxes spread via WhatsApp in Spain to prevent and/or cure COVID-19 by Moreno-Castro et al. (2021). In their study, Salaverría et al. (2020) reveal that in the early months of the pandemic Spanish fact checkers disclosed a plethora of false recommendations and treatments. Its lower presence in the corpus as a whole, and even its absence in the Spanish sample, may suggest that this topic had lost ground to other issues, such as vaccination, social distancing, and the number of cases and deaths.

Albeit to a lesser extent, disinformation about the “causative agents” of COVID-19 was also identified, as in the case of one news item fact checked by Lupa (Mar. 8, 2021) 23, which proved that a claim, attributed to Russia, that the disease was caused by bacteria modified by 5G was false. In this less frequent category there were stories about the effects of the disease — “Is an Involuntary Erection Lasting more than Four Hours a New Symptom of COVID-19?” (Polígrafo, Mar. 21, 2021) 24 — and about other topics, such as the care taken in post-mortems of COVID-19 victims and social welfare during the pandemic.

4. Concluding remarks ↑

The analysis of the pandemic-related fact checks carried out by Lupa (Brazil), Newtral (Spain), and Polígrafo (Portugal) in March 2021 revealed both similarities and differences between the ways disinformation was presented. The disinformation identified in all three countries shared three similarities, namely, a predominance of false content, the primary use of text formats, and its circulation on social media platforms. This indicates that there could be transnational trends in disinformation and in the discursive battles raging over this phenomenon.

The fact that 80.5 % of all the news items in our corpus were classified by the fact-checking organizations as false indicates that this was the type of disinformation prevailing in the public debate at the time when the data were collected. If studies conducted early in the pandemic in other contexts, such as that of Brennan et al. (2020), reveal a predominance of manipulated content, our results show that one year on, there was more disinformation that was completely fabricated, which could be particularly harmful for the public debate.

In all three countries, social media were the channel most frequently used to circulate disinformation, thus confirming a trend already noted in the literature on disinformation and healthcare. Understanding the context of the COVID-19 infodemic implies recognizing the importance of digital media in the dynamics of the production, circulation, and reception of disinformation. On the other hand, this phenomenon points to the existence of a media ecosystem — of which fact-checking organizations form part — in which they can also be harnessed to combat disinformation and appropriated in media literacy initiatives.

Another similarity between the three countries was the use of texts as the predominant format for spreading disinformation, followed by audio-visual content. The ease with which texts can be produced could be one of the reasons behind their prevalence, reinforcing the importance of studies designed to investigate the aesthetic features and narratives employed.

Regarding the type of source cited to validate the false narratives, the data fact checked by each organization painted a diverse picture. Scientific sources predominated among the stories fact checked by Lupa and Newtral, but only ranked fifth in the case of Polígrafo, which indicates that the strategic use of science for validating news story with no scientific basis could be a key feature of the infodemic in Brazil and Spain. The information fact checked by Lupa often took the shape of testimonials, which was not the case with the other two organizations. This might have had to do with the local context, in which testimonials in combination with other validation strategies have been noted in discourses, including those of political leaders, advocating for the use of ineffective treatments. As to the fact checks performed by Newtral, scientific sources were followed by the expert and political kind. For its part, Polígrafo was the only fact-checking organization to register a prevalence of news stories citing media sources, although the specialist and political kind also prevailed in the Portuguese sample.

As to the topics covered, vaccination was the most prevalent. However, while in the stories fact checked by Lupa the accent was placed on the vaccination process, in those verified by Newtral and Polígrafo anti-vax narratives were more common. Once again, the cultural idiosyncrasies of the three countries might have affected the way in which immunization was addressed in COVID-19-related disinformation — either with stories that cast doubt on the vaccines’ safety and effectiveness or by exploiting the vaccination process for political gain.

Other topics that appeared frequently in the samples included “preventive measures” and “number of cases and deaths”, which ranked among the top three in the news items fact checked by each organization. These were followed by “treatment” particularly in Brazil (Lupa), “causative agents” in Spain (Newtral), and “mismanagement of the pandemic”, which came in joint third place in Portugal (Polígrafo). Only one specific piece of disinformation appeared in all three countries, thus reflecting the variety of subjects and narratives covered in local contexts. Despite being a global phenomenon, the disinformation about the pandemic was shaped by the political, social, and cultural particularities of each one of the three countries.

Our analysis of fact-checking in Spain, Portugal, and Brazil confirms the complexity of the contemporary infodemic. The existence of similarities and differences between the subject matter confirms our hypothesis of the “glocality” of disinformation in the three countries. In a situation in which transnational trends interweave with local contexts, more comparative studies are required for tailoring strategies to local and international contexts in order to combat disinformation.

Funding ↑

Performed at the Instituto Nacional de Comunicação Pública da Ciência e Tecnologia (INCT-CPCT), based at the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz), this study was funded by the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Inova Fiocruz/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, all from Brazil.

Sources and bibliography ↑

Allcott, Hunt, & Gentzkow, Mathew (2017): “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election”, in Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31 (2), pp. 211-236. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Bardin, Laurence (2011): Análise de conteúdo. Edições 70.

Brennan, J. Scott; Simon, Felix Marvin; Howard, Philip N.; & Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis (2020): Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation. Oxford: Reuters Institute/University of Oxford. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation

Cardoso, Gustavo; Pinto-Martinho, Ana; Narciso, Inês; Moreno, José; Crespo, Miguel; Palma, Nuno; & Sepúlveda, Rita (2020): Information and misinformation on the Coronavirus in Portugal: Whatsapp, Facebook e Google Searches. Lisbon: Media Lab. Retrieved from https://medialab.iscte-iul.pt/information-and-misinformation-coronavirus-in-portugal/

Ceron, Wilson; De-Lima-Santos, Mathias-Felipe; & Quiles, Marcos G. (2021): “Fake News Agenda in the Era of COVID-19: Identifying Trends through Fact-Checking Content”, in Online Social Networks and Media, 21, pp. 1-14. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.osnem.2020.100116

Chen, Yimin; Conroy, Niall J.; & Rubin, Victoria L. (2015): “Misleading Online Content: Recognizing Clickbait as ‘False News’”, in WMDD’15: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on Workshop on Multimodal Deception Detection. Doi: http://doi.org/10.1145/2823465.2823467

Chou, Wen-Ying S.; Hunt, Yvonne M.; Beckjord, Ellen B.; Moser, Richard P.; & Hesse, Bradford, W. (2009): “Social Media Use in the United States: Implications for Health Communication”, in Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11 (4), e48. Doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1249

Cinelli, Matteo; Quattrociocchi, Walter; Galeazzi, Alessandro; Valensise, Carlo Michele; Brugnoli, Emanuele; Schmidt, Ana Lucia; Zola, Paola; Zollo, Fabiana; & Scala, Antonio (2020): “The COVID-19 Social Media Infodemic”, in Scientific Reports, 10 (1), e16598. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

Costa, José Carlos (2021): “Os impactos da COVID-19 no acesso à saúde em Portugal: Uma cartografia dos resultados registados durante a segunda vaga da pandemia”, in ARIES: Anuario de Antropologia Iberoamericana, 1-10. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3D2Jh5K

Cuesta-Cambra, Ubaldo; Martínez-Martínez, Luz; & Niño-González, José Ignacio (2019): “An Analysis of Pro-Vaccine and Anti-Vaccine Information on Social Networks and the Internet: Visual and Emotional Patterns”, in El Profesional de la Información, 28 (2), e280217. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.mar.17

Diele-Viegas, Luisa María; Hipólito, Juliana; & Ferrante, Lucas (2021): “Scientific Denialism Threatens Brazil”, in Science, 374 (6.5700), pp. 948-949. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abm9933

Domínguez-Gil, Beatriz; Coll, Elisabeth; Fernández-Ruiz, Mario; Corral, Esther; Del-Río, Francisco; Zaragoza, Rafael; Rubio, Juan J.; & Hernández, Domingo (2020): “COVID-19 in Spain: Transplantation in the midst of the pandemic”, in Am. J. Transplant., 20 (9), pp. 2593-2598. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15983

Fernández-Torres, María Jesús; Almansa-Martínez, Ana; & Chamizo-Sánchez, Rocío (2021): “Infodemic and Fake News in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic”, in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (4), 1781. Doi: http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041781

Graves, Lucas; Nyhan, Brendan; & Reifler, Jason (2016): “Understanding Innovations in Journalistic Practice: A Field Experiment Examining Motivations for Fact-Checking”, in Journal of Communication, 66 (1), pp. 102-138. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12198

Iftimie, Simona; López-Azcona, Ana F.; Lozano-Olmo, María José; Hernández-Aguilera, Anna; Sarrá-Moretó, Salvador; Joven, Jorge; Camps, Jordi; & Castro, Antoni (2021): “Differential Features of the Fifth Wave of COVID-19 Associated with Vaccination and the Delta Variant in a Reference Hospital in Catalonia, Spain”, in medRxiv. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.14.21264933

Kata, Anna (2012): “Anti-Vaccine Activists, Web 2.0, and the Postmodern Paradigm: An Overview of Tactics and Tropes Used Online by the Anti-Vaccination Movement”, in Vaccine, 30 (25), pp. 3778-3789. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.112

Lazer, David M. J.; Baum, Matthew A.; Benkler, Yochai; Berinsky, Adam J.; Greenhill, Kelly M.; Menczer, Filippo; Metzger, Miriam J.; Nyhan, Brendan; Pennycook, Gordon; Rothschild, David; Schudson, Michael; Sloman, Steven A.; Sunstein, Cass R.; Thorson, Emily A.; Watts, Duncan J.; & Zittrain, Jonathan L. (2018): “The Science of Fake News”, in Science, 359 (6380), pp. 1094-1096. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

López-García, Xosé; Costa-Sánchez, Carmen; & Vizoso, Ángel (2021): “Journalistic Fact-Checking of Information in Pandemic: Stakeholders, Hoaxes, and Strategies to Fight Disinformation during the COVID-19 Crisis in Spain”, in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (3), 1227. Doi: http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031227

Machado, Caio C. Vieira; Santos, Joao Guilherme; Santos, Nina; & Bandeira, Luiza (2020): Scientific [Self] Isolation. LAUT, INCT-DD, CEPEDISA. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3sl7SAY

Massarani, Luisa; Leal, Tatiane; & Waltz, Igor (2020): “O debate sobre vacinas em redes sociais: uma análise exploratória dos links com maior engajamento”, in Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36 (Suppl. 2), pp. 1-13. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00148319

Monari, Ana Carolina; Santos, Allan; & Sacramento, Igor (2020): “COVID-19 and (Hydroxy)Chloroquine: a Dispute over Scientific Truth during Bolsonaro’s Weekly Facebook Live Streams”, in Journal of Science Communication, 19 (07), A03. Doi: https://doi.org/10.22323/2.19070203

Moreno, José; Narciso, Inês; & Sepúlveda, Rita (2021): “Dinâmicas de circulação de conteúdo (des)informativo sobre a COVID-19 no WhatsApp, nos media e nas redes sociais online”, in Observatorio (OBS*), 15 (1), 03-23. Doi: https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS0020211926

Moreno-Castro, Carolina; Vengut-Climent, Empar; Cano-Orón, Lorena; & Mendoza-Poudereux, Isabel (2021): “Exploratory Study of the Hoaxes Spread Via WhatsApp in Spain to Prevent and/or Cure COVID-19”, in Gaceta Sanitaria, 35 (6), pp. 534-540. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2020.07.008

Newman, Nic; Fletcher, Richard; Schulz, Anne; Andi, Sigme; & Nielse, Rasmus Kleis (2020): Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Reuters Institute/University of Oxford. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3GXW7V3

Oliveira, Thaiane M. (2020a): “Como enfrentar a desinformação científica? Desafios sociais, políticos e jurídicos intensificados no contexto da pandemia”, in Liinc em Revista, 16 (2), e5374. Doi: https://doi.org/10.18617/liinc.v16i2.5374

Oliveira, Thaiane M. (2020b): “Desinformação científica em tempos de crise epistêmica: circulação de teorias da conspiração nas plataformas de mídias sociais”, in Fronteiras-Estudos Midiáticos, 22 (1), pp. 21-35. Doi: https://doi.org/10.4013/fem.2020.221.03

Oliveira, Thaiane; Quinan, Rodrigo; & Toth, Janderson P. (2020): “Anti-vacina, fosfoetanolamina e mineral miracle solution (mms): mapeamento de fake sciences ligadas à saúde no Facebook”, in Reciis—Revista Eletrônica de Comunicação, Informação e Inovação em Saúde, 14 (1), pp. 90-111. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29397/reciis.v14i1.1988

Pérez-Laurrabaquio, Óscar (2021): “Covid-19 en España: primera ola de la emergencia”, in Medicina General y de Familia, 10 (1), pp. 3-9. Doi: http://doi.org/10.24038/mgyf.2021.007

Quintana Pujalte, Leticia, & Pannunzio, María Florencia (2021): “Fact-checking en Latinoamérica. Tipología de contenidos virales desmentidos durante la pandemia del coronavirus”, in Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información, 26, pp. 27-46. Doi: https://doi.org/10.35742/rcci.2021.26.e178

Recuero, Raquel; Soares, Felipe; & Zago, Gabriela (2021): “Polarization, Hyperpartisanship, and Echo Chambers: how the Disinformation about COVID-19 Circulates on Twitter”, in Contracampo, 40 (1). Doi: http://doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v40i1.45611

Romero Rodríguez, Luis Miguel (2013): “Hacia un estado de la cuestion de las investigaciones sobre desinformación/misinformación”, in Correspondencias & Análisis, (3), pp. 319-342. Retrieved from https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4739767

Sacramento, Igor; Santos, Allan; & Abib, Roberto (2020): “A saúde na era na testemunha: experiência e evidência na defesa da hidroxicloroquina”, in Revista Comunicação, Cultura e Sociedade, 7 (1), 003-023. Available at https://periodicos.unemat.br/index.php/ccs/article/view/5087

Salaverría, Ramón; Buslón, Nataly; López-Pan, Fernando; León, Bienvenido; López-Goñi, Ignacio; Erviti, María-Carmen (2020): “Desinformación en tiempos de pandemia: tipología de los bulos sobre la Covid-19”, en El Profesional de la Información, 29 (3), e290315. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.15

Sampaio, Rafael Cardoso, & Lycarião, Diógenes (2021): Análise de conteúdo categorial: manual de aplicação. Enap Escola Nacional de Administração Pública. Retrieved from https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/6542

Soares, Felipe B.; Recuero, Raquel; Volcan, Taiane; Fagundes, Giane; & Sodré, Giéle (2021): “Research Note: Bolsonaro’s Firehose: How Covid-19 Disinformation on WhatsApp Was Used to Fight a Government Political Crisis in Brazil”, in The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 2 (1). Doi: http://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-54

Tandoc Jr., Edson (2019): “The Facts of Fake News: A Research Review”, in Sociology Compass, 13 (9): e12724. Doi: http://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12724

The Lancet (2020): COVID-19 in Brazil: ‘so what?’”, in The Lancet, 395 (10235), 1461. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31095-3

Wardle, Claire (2019): First Draft’s Essential Guide to Understanding Information Disorder. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3suiNrY

Wardle, Claire, & Derakhshan, Hossein (2017): Information Disorder: toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3FflYHP

WHO (2018): Managing Epidemics: Key Facts about Major Deadly Diseases. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272442

Zago, Gabriela & Silva, Ana Lucía (2014): “Sites de rede social e economia da atenção: circulação e consumo de informações no Facebook e no Twitter”, in Vozes e Diálogo, 13 (1), pp. 5-17. Doi: https://doi.org/10.14210/vd.v13n01.p%25p

1 Available at: https://bit.ly/3pddDyH. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

2 Available at: https://bit.ly/3J1O0ZL. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

3 Data from World Bank. Available at: https://bit.ly/3slaezO. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

4 Data from the Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University. Available at: https://bit.ly/3GYTuTc. Accessed on: Dec. 20, 2021.

5 Data from World Bank. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Ei832e. Accessed on: Dec. 20, 2021.

6 Data from the Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University. Available at: https://bit.ly/3GYTuTc. Accessed on: Dec. 20, 2021.

7 Data from the Ministry of Health of Portugal. Available at bit.ly/3M9YGro. Accessed on: May 15, 2023.

8 Data from the Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University. Available at: https://bit.ly/3GYTuTc. Accessed on: Dec. 20, 2021.

9 The definitions of the classifications can be consulted at: Lupa — https://bit.ly/32lh0dU, Newtral — https://bit.ly/3yHyBZL, Polígrafo — https://bit.ly/3J9R5ae. Accessed on Dec. 1, 2021..

10 Available at: https://bit.ly/3zuErzY. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

11 Available at: https://bit.ly/3O2PPHr. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

12 Available at: https://bit.ly/3EeZANh. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

13 Available at: https://bit.ly/3mmdKWW. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

14 Available at: https://bit.ly/32hoOh3. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

15 Available at: https://bit.ly/3sh0vdU. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

16 Available at: https://bit.ly/3J8fAEm. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

17 Available at: https://bit.ly/3pgd1IN. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

18 Available at: https://bit.ly/3qdlETx. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

19 Available at: https://bit.ly/33zbMvF. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

20 Available at: https://bit.ly/3ecxkAh. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

21 Available at: https://bit.ly/3J6Dn7N. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

22 Available at: https://bit.ly/3EiVvYu. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

23 Available at: https://bit.ly/3J5jQEG. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.

24 Available at: https://bit.ly/3yIVLyX. Accessed on: Dec. 1, 2021.