Between Strangeness and Natural Equivalences: Translating Lorine Niedecker's Experimental Poetry

Natalia Carbajosa Palmero

Universidad de Málaga

Este artículo muestra cómo mis traducciones de la poeta norteamericana objetivista Lorine Niedecker para el volume bilingüe Y el lugar era agua: Antología poética, publicado en 2018, han buscado constantemente equivalencias plausibles en español en cuanto a ritmo y sonido, a la vez que tratan de aplicar distintas estrategias traductológicas con el fin de mantener el tono de extrañeza que requiere una aproximación más literal a la traducción (siguiendo las reflexiones de Walter Benjamin acerca de la traducción de la poesía experimental). Para lograrlo, el artículo revisa usos específicos de la traducción (signos de puntuación como el guion largo y otros elementos visuales, paráfrasis y amplificación, homofonía, aliteración, y técnicas para el mantenimiento de un tono sostenido en el texto traducido). Sin ser definitivas, las conclusiones de este enfoque a la traducción de la poesía experimental, intrínsecas a los poemas analizados, confirman al menos la constante fluctuación entre los dos extremos que contribuyen a la naturalidad de un poema traducido, a la vez que aflora su extrañeza lingüística. Más aún: relacionan las prácticas y perspectivas predominantes sobre cómo traducir poesía angloamericana experimental para los lectores hispanohablantes del siglo XXI.

palabras clave: Traducción de poesía, poesía experimental, extrañeza, aproximación literal, técnicas de traducción.

Entre la extrañeza y las equivalencias naturales: traducir la poesía experimental de Lorine Niedecker

This paper shows how my translations of objetivist American poet Lorine Niedecker for the bilingual volume Y el lugar era agua: Antología poética, published in 2018, have constantly sought for natural Spanish equivalences in sound and rhythm while trying, through different translating and rhetorical techniques, to keep the tone of strangeness that a more literal approach to the translation (after Walter Benjamin's reflections on the translation of experimental poetry) would render. To this end, specific translation uses (punctuation sings such as the long dash and other visual display elements, paraphrasing and amplification, homophony, alliteration, and techniques for the reproduction of a sustained tone in the target text) will be explained with respect to the translation choices for some of the most successful poems of the author. Far from definitive, the conclusions for such an approach to the translation of experimental poetry, intrinsic in the poems analyzed, give at least evidence of the constant oscillation between the two extremes of making a poem sound natural in the translation, at the same time that its linguistic strangeness is exposed. More importantly, they connect with the predominant views and practices about how to translate twentieth-century Anglo-American experimental poetry for twenty first-century Spanish readers.

key words:

Poetry Translation, Experimental Poetry, Strangeness, Literal Approach, Translation Techniques.

recibido en febrero de 2020 aceptado en septiembre de 2020

INTRODUCtion

In the last decades1, among Spanish translators of contemporary Anglo-American poetry, the prevailing views about poetry translation have moved on from Robert Frost’s gloomy adage that “poetry is what is lost in translation” and been replaced by an open acknowledgement of the difficulties and an active engagement with the challenges (Doce, 2007). This line of thought is appropriate for the demanding register of Lorine Niedecker’s surrealist-objectivist poetry (Wisconsin, 1903-1970), namely, the awareness of the untranslatable estrangement inherent in all poetry and in avant-garde poetry in particular; a kind of estrangement that turns each poet’s style into a language in itself.

Experimental poetry has forced translators to review their techniques, because the surplus of unintelligibility that contemporary poetry offers is, in its own way, the catalyst for the awareness of experimentation in both languages. Walter Benjamin wrote in 1923 that «the fundamental error of the translator is that he holds fast to the state in which his own language happens to be rather than allowing it to be put powerfully in movement by the foreign language». With this in mind, the poetry translator’s task is to try to open up spaces in the target language for the inexpressible, or unintelligible, latent in the source text, always fluctuating between the two extremes of either keeping the foreign aspects visible or immersing them in Spanish and its cultural context.

Who was Lorine Niedecker? To pose this question among readers of poetry in Spain would produce few answers, just as Niedecker’s question in her poem “Who was Mary Shelley” anticipated few answers. Since Niedecker asked her question in the early 1960s, and even before, Mary Shelley and her writing have become widely known. We can allow ourselves to hope and even expect that the same recognition awaits Niedecker. Born in 1903 in the island of Black Hawk in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, where she stayed for most of her life under constant economic stress and among working-class neighbors who knew very little of her devotion to art, hers is a unique example of a kind of surrealist-objectivist poetry with a local flavor taken from her hometown’s working-class idiom and folklore.

Admired by poets like Cid Corman and Charles Tomlinson, Niedecker has been named «the twentieth-century Emily Dickinson» for the sparseness of her almost subterranean poetry, through which she managed to talk about the hardships of her life without ever becoming sentimental, not even, for that part, confessional (Carbajosa, 2016). Since the beginning of this century, she has been claimed by critics as an enlightening voice, capable of addressing gender and class issues in an avant-garde register, even before the former ones were acknowledged as such.2 Among her main books we can highlight New Goose, My Friend Tree, North Central or My Life by Water, all of them subjected to an erratic publishing trajectory that only recently has been amended through the 2002 publication of her Collected Works by Jenny Penberthy.

My 2018 Spanish translation of Niedecker in a bilingual volume Y el lugar era agua: Antología poética, published by Eolas Editions in North-west Spain is part of a trend in Spain since the 1990s to translate Anglo-American poetry into Spanish. Alongside this is the widespread interest in Spain in discovering new women writers. Where the experimental character of Niedecker’s poetry might have discouraged readers and publishers, now a number of small independent publishers have established themselves and in the last two decades have discovered a growing interest in reading and circulating foreign, non-mainstream poetry in books and magazines, printed or online.

I discovered Niedecker’s poetry while I was translating the Language poet Rae Armantrout. Although she is not a prolific essayist, Armantrout’s brief reflections on difficult poets are among the most compelling sources I have come across and have, without fail, drawn me to the very authors she herself admires. Her 10-page essay “Darkinfested” (2007) put me on to Niedecker’s poetry.

Having those preliminary statements into account, the purpose of this article is no other than sharing a few reflections about the difficulties and challenges, also about the rewards, of translating her poetry into Spanish. Before dealing with the poems, however, I would briefly like to focus on some previous ideas about the translation task itself. Both the difficulties of translating poetry into another language and the specific nature of Niedecker’s poetic style seem to ask for this. Otherwise, some particular decisions in regard to the translation of sounds, for example, or to the constant ‘trade-off’ between the natural and the strange in the translated versions, would not be properly understood.

The prevailing views about translating poetry have moved on from Robert Frost’s gloomy adage that «poetry is what is lost in translation» and been replaced by an open acknowledgement of the difficulties and an active engagement with the challenges. Among Spanish professionals, the poet and translator Carlos Jiménez Arribas believes, for example, that the trace of the untranslatable is the most translatable part of a poem.3 This line of thought is appropriate for the challenging register of Lorine Niedecker’s poetry, namely, the awareness of the untranslatable estrangement inherent in all poetry and in avant-garde poetry in particular; a kind of estrangement that turns each poet’s style into a language in itself.

Under this light, the poetry translator’s task is to try to open up spaces, in the target language (in this case, Spanish) for the inexpressible, or unintelligible, latent in the source text (here, the original English). Always fluctuating between the two extremes of either keeping the foreign aspects visible or immersing them in Spanish and its cultural context, most poetry translators see their activity as a variant or extension of literary creation that reveals the impossibility of translating in the full sense of the term, as Jordi Doce says. Furthermore, translators agree that the translation should sound like poetry within the limits imposed by the source language.

In the case of the Niedecker translations, Anglophone material, rhythm and sound patterns must be translated into Spanish, a Romance language that, instead of beats and alliteration, bases its poetry traditions on syllabic meter and consonant/assonant rhyme. Niedecker’s method is outlined for the Spanish reader in the introduction to the translated edition:

lines are carried forwards on the previous ones as mud is carried forward by water; enjambments make grammatical categories float, like water makes household utensils float; unfinished endings could very well be the beginning of an inescapably cyclic reality (9-10).4

Experimental poetry has forced translators to review their techniques, because the surplus of unintelligibility that contemporary poetry offers is, in its own way, the catalyst for the awareness of experimentation in both languages. Walter Benjamin wrote in 1923 that «the fundamental error of the translator is that he holds fast to the state in which his own language happens to be rather than allowing it to be put powerfully in movement by the foreign language». (1997: 153). Bearing this in mind, my translation of Niedecker has constantly sought for natural Spanish equivalences in sound and rhythm while trying to keep the tone of strangeness that a more literal approach to the translation would give.

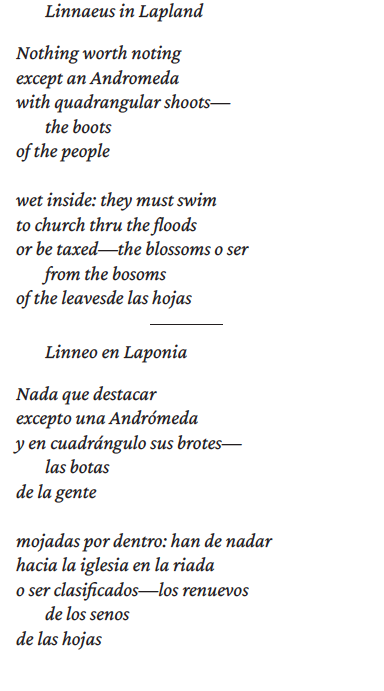

One example of this double strategy lies in the visual/aural impact of the poems. In a large number of them, Niedecker uses the long dash as a resource for joining and separating words/clauses/realities all at once. This delays the flow of the poem for a second then it lets the lines flow unexpectedly in a different direction. In email exchanges with poet Bob Arnold, literary executor of Lorine Niedecker’s works, he suggested that her dash operates almost as a word, since it impacts the structure of the stanza, as well as the tone and appearance. At first, I was reluctant to use a punctuation mark that does not have a clear equivalence in Spanish, but he persuaded me to keep it it. The following poem, whose content is entirely drawn from the journals of Linnaeus, is one of many examples:

In this poem, Linnaeus’ scientific notes appear juxtaposed to the poet’s awareness of her closest reality, with certain terms (shoots/brotes) flowing naturally from the scientific to the quotidian (blossoms/renuevos). This flow, or displacement of meaning, begins in the first stanza where the dash signals a change from the botanical observation to the observation of local people wading through water towards the church. The episode continues in the second stanza where, again, the dash marks another change or displacement: “be taxed” can refer both to people having to pay taxes, and to the famous botanist’s taxonomic classification of species.

As far as the translation is concerned, notwithstanding the unfamiliar presence of the dash in Spanish, the visual effect is similar to that of the original version. In the first stanza where “shoots” and “boots” are tensely separated by the dash while joined by sound, the same occurs with “brotes” and “botas” where sound similarity is based on alliteration rather than rhyme. Alliteration is a less common resource than rhyme in Spanish poetry and, therefore, its use instils a feeling of strangeness. The same can be said, in the second stanza, with the sound pairing between “blossoms” and “bosoms” in the original, and “renuevos” and “senos” in the translation: here, with assonance in “e-os” and alliteration in “n”. The sound-patterned transfer of meaning occurs here as it does in the Niedecker original.

In contrast, the multiple meanings of “be taxed,” cannot be reproduced in Spanish. In my first draft, I translated it in its economic/punitive sense, which was right for “the people” but not for “the blossoms”; on second thoughts, I opted for the “classification” nuance because, even though obliquely (and with the help of an endnote), it could contain a hint for both contexts. All in all, the cadence of the translation runs smoothly, mainly thanks to the recurrence of the liquid phoneme /r/ and the alternation of the open vowel sounds /a/ and /o /.

As for the first line –and Niedecker seems more than conscious of the sound effects that her poem openings produce–, the threefold trochaic beat (“Nóthing/wórth/nóting”), reinforced by the alliterative phonemes /n/, /i/ and nasal /ŋ/, is attenuated in the translation, although alliteration is also present in the invariable Spanish /a/ sound: “Nada que destacar.” It should be remembered that the Spanish language has only five vowel sounds, corresponding to the five vowel letters. That is the main reason why English pronunciation is so difficult for Spanish learners, as English has thirteen different vowel sounds and, consequently, there is no direct relationship between sounds and letters. In compensation, a rhythmic impact is produced by the proximity of two long words whose stress falls on the third-from-last syllable, “An/dró/me/da” and “cua/drán/gu/lo.” This type of stress is the least frequent in Spanish and its sounding is always powerful and immediately perceived. Its use in poetry is very striking.

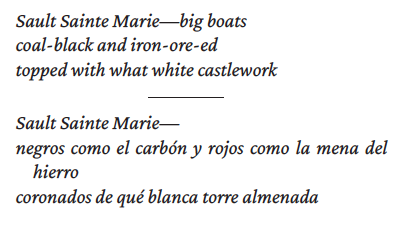

Another example of the difficulty of literal translation of English poetry occurs with compound words where Spanish cannot hyphenate two words to form a compound. This is evident, among many instances, in the following lines from “Lake Superior,” a long poem, crucial in the poet’s late trajectory, that exemplifies Niedecker’s capacity to join history, geology and poetic language in extreme condensation:5

The translation keeps the dash but cannot incorporate the hyphenated constructions “coal-black” and “iron-ore-red.” Instead, those two compound adjectives have to be paraphrased with the help of the particle “como” (like), forming a much longer line than the original. A translating practice which is less popular now than decades ago, would probably have opted for splitting such a long line into two. In contrast, I prefer to keep the same number of lines, since Spanish poetry allows for such long lines without losing rhythm; furthermore, the parallel expression marked by the repetition of “como,” together with the predominance of two-syllable words stressed in the first syllable (“grán/des”, “bár/cos”, “né/gros”, “ró/jos”, “mé/na”, “hié/rro”, “blán/ca”, “tó/rre”), make the lines fit better into the stanza, as well as in relation to the rest of elements.

Paraphrase as a kind of amplification (from the Latin amplificatio, that is, increase or addition) is the translating solution in the following poem as well:

As we know, this and other five-line poems represent Niedecker’s way of evoking the haiku. On the sound level, the rhyme or near-rhyme of “wall,” “hole” and “cold” is transferred to “atornilló,” “tapó” and – in the last line – “ratón” (mouse), thus reproducing the playful tone of the poem, easily identifiable in the Spanish version (several Spanish nursery rhymes play with the word “ratón” and the repetition of the terminal “on”: “debajo de un botón-tón-tón… había un ratón-tón-tón…”). To that end, the past participle form “screwed to” has been changed by the simple past forms “atornilló” and “tapó,” which rhyme in assonance with “ratón.”

The unexpected element in Niedecker’s poem is the use of the noun “mouse” as if it were a verb “mouse in.” This change in the word category sneaks into the poem as a real mouse would sneak into a room. The translation misses this crucial nuance because the Spanish language doesn’t allow for such a twist of word category; the alternative could be literally translated as “so that the cold cannot sneak in / like a mouse.” In compensation, the displacement of the rhyme from “frío” (cold) to “ratón” (mouse), not by chance the last word in the Spanish version, leaves an arresting final impression on the reader, not far from the stealthy surprise factor in the original. The translation remains aware of the philosophy behind the composition of haiku with its simple – though hard to achieve – combination of image and movement at the same time that it catches the childish air implied from the very beginning by the term “pop-corn,” even more childish-sounding in the Spanish term “palomitas.”

In relation to homophony –the language phenomenon of two words that look different but sound exactly the same– another five-line poem presents an interesting case:

Niedecker starts her poem with “Hear” while the term simultaneously evokes the adverb of place, “here.” In Spanish, there is not such homophony between the equivalent terms. However, the imperative “hear” in the second person plural form (“Oíd”) and the adverb of place “there” (“ahí”) are very similar in sound. In this case, therefore, the two words together emphasize the double resonance of the original. In contrast, the word “here” is translated in a different way in the first stanza of the following poem written after a review that Zukofsky wrote about her work:

Unlike the poem “Hear / where her snow-grave is” now the adverb “here” is literally translated as “aquí;” it does not try to evoke the “hear” implicit in the original version. The double-word choice of the previous example (“oíd ahí”) could have been incorporated in this poem and for the same reasons. However, in this second case, the result sounds unnecessarily contrived in Spanish. To compensate for the loss of resonance, then, the second and final stanza of the translated poem reproduces the frequency of the /i/ sound that serves as onomatopoeia for the cricket song (the matching sounds are underlined):

The last line, “un poquito,” literally means “a little bit” (“a little” would be translated as “un poco”). Opting for “un poquito” helps reproduce the /i/ sound at the same time that it emphasizes the importance of this final line for the correct reading of the poem. According to Rae Armantrout, in this poem probably written after a review in The New York Times of Zukofsky’s Some Time, we do not learn whether the poet is pleased with the review or not: «Is it fame itself that is ephemeral—ringing only “a little,” as Niedecker puts it with her dry wit? Or is it her evening which, in contrast to fame, is a seedy, quiet thing, but one which rings with cricket-song? In either case, her own life and the life of the famous person are held within the brackets the phrase “a little” deftly constructs» (66). Niedecker’s and Zukofsky’s long epistolary relationship has been documented by Penberthy (1993).

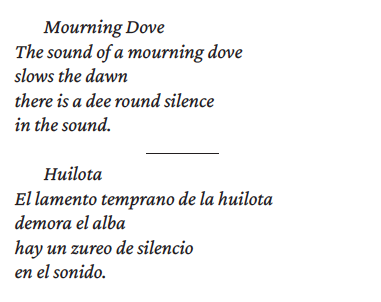

Going back to the poem “Hear / where her snow-grave is,” clearly related to Niedecker’s mother’s passing, it is interesting to note how the name of the “mourning dove” with its inherent reference to the sad cooing sound and, by means of homophony, to the time of day (mourning / morning), cannot be directly translated. The Spanish version uses the American bird species common noun “huilota” and, once more, resorts to amplification by introducing the adjective “triste” (i.e. sad, mournful), in agreement with the mood of the poem. Niedecker’s mother, deaf since her daughter’s birth and neglected by her husband, is a constant reference in the poet’s writings, acting as a mirror of the very despondency that the author tried to shy away from throughout her life.

The mourning dove appears in another, earlier poem, but in this case the supplementary information is different, as the poem’s subject demands:

In this poem, Niedecker refers to the mourning dove’s particular way of cooing twice: the first time, simply as “sound;” the second time, as a “dee round silence / in the sound,” where “dee” works as the onomatopoeia both of the bird’s coo and the musical key, thus emphasizing the paradoxical quality in the association of “silence” with “sound.”6 The difficulty of translating “mourning dove” into Spanish in regard to the “mourning” nuance leads me once more to the solution of amplification: “lamento temprano” (literally, early mourn). These two terms replace the much simpler “sound” while conveying the double nuance of “early” in relation to “mo(u)rning” and “dawn” (the line “demora el alba” is accurately rendered from “slows the dawn”) and also to a mournful sound.

As for the “dee sound,” it is translated by the prepositional phrase “zureo de silencio;” “zureo” is a noun that describes the cooing sound of any dove. This is not a frequent word in Spanish, though quite powerful in its resonance. Concretely, it forces the reader to pay attention to it in the middle of the line, producing an effect analogous to “dee,” equally singled out as a “rare” element in the original poem. Obviously, there is no semantic literal translation in this choice. However, my thorough search for a sound equivalence has led me to a translation of the resonance of the dove’s “utterance” that the poem aims to transmit.

Finally, compensating for the omission of “sound” in its first appearance in the translation, in its second appearance “sound” is placed prominently at the end of the stanza. In regard to this decision, it seemed crucial to highlight the rhythmic part in the closing, together with its phonic relation with “silence.” This time, there are no obstacles to the exact translation: silencio-silence / sonido-sound. Furthermore, and even though Spanish stress patterns do not correspond to beats, there is a natural tendency to read these final lines in the English rhythmic-patterned mode; the result differs from Niedecker’s original but, to a certain extent, it corresponds to the intended effect of quiet closure, as can be appreciated in the stressed words and syllables signaled in the following lines:

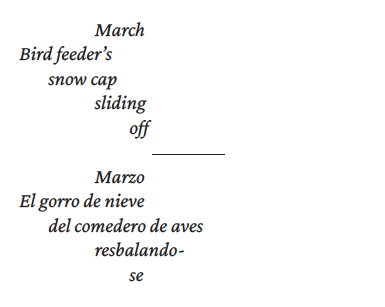

A corollary to the previous comments is to be found in the following poem. Here, the two techniques of trying to make the poem sound natural in Spanish at the same time that its experimental nature is exposed converge, this time for the sake of visual display on the page:

In this example, the Spanish version takes up more space than the original but this can’t be avoided because the Spanish language has fewer monosyllabic words than English. In addition, the absence of the possessive structure “apostrophe + s” in Spanish makes it necessary to use the preposition of possession “de” (of). All of this reduces the visual force of the poem. Nevertheless, the descending-scale structure crucial to the poem’s identity is preserved.

The two last lines pose another problem: there are no verbs in Spanish formed by two words, such as “slide off.” In contrast, reflexive verbs such as “wash oneself” / “lavarse” (formed from “wash” / “lavar”) are quite common, and the case is applicable here: “resbalando-se.” The implicit nuance is that the bird feeder’s snow cap slides because of the very weight of the snow itself, without any external help. I have, therefore, replaced a prepositional particle by a reflexive pronoun particle.

At this stage, the visual arrangement requires further work: on the one hand, the pronoun cannot be separated from the stem verb; on the other hand, in Spanish verse it is allowable to split up parts of a word between the end of a line and the following one, as long as they belong to different syllables. This separation should always be hyphenated, as is in prose. To split the verb into two in this poem, following the rules at the same time that we respect the literal translation i.e. focusing the attention on the act of sliding off by the position of the verb itself on two different lines, finally enables us to achieve an eloquent fidelity to the original poem, not only in its visual display but also in the perception of the gentle movement that is produced, once more, in a haiku-like manner.

The weight of alliteration (specifically, the repetition of initial consonants in words) as a source of communication through sound instead of merely through semantic meaning is of course inherent to all poetry in English, and a powerful resource in Niedecker’s poems. Its translation into Spanish relies, to a certain extent, on looking for alternative repetitions of initial consonants. The strategy is visible in the memorable opening of “Paean to Place,” one of her most important compositions:

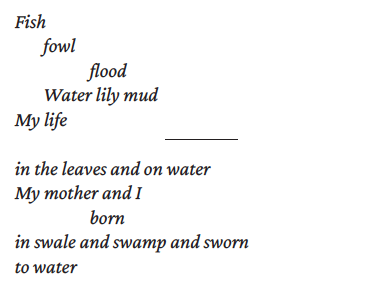

The sound impact of this opening is the main criterion for translation, even more than the direct rendering of meaning. This priority requires a certain semantic displacement. For the fricative /f/ sound of “fish/fowl/flood” to become the plosive /p/ of “pez/pájaro/pantano,” a free translation of “flood” is necessary (“pantano” meaning “swamp” or “marsh”). With the /sw/ phonic group of “swale/swamp/sworn”, the /m/ and /a/ sounds in “marjal/marisma/amarradas” also involve a readjustment in meaning (“amarradas” means “tied up” or “moored”). This is a clear example of keeping the strangeness of the language, on the one hand, because sound repetition through alliteration is not a common strategy in Spanish where end-rhyme is the usual procedure. On the other hand, subordinating meaning to sound is a way of keeping the result as natural as possible, using the old technique of direct transposition of one word for another, where both words belong to the same grammatical category.

An important goal in the translation and composition of this book has been to create a sustained tone throughout the whole collection. This is particularly relevant in the selection of poems for the Spanish anthology from the book New Goose, where traditional rhyme patterns associated with folklore mesh with experimental procedures. Since direct translation of rhymed sounds is impossible, I have resorted to several solutions. A paradigmatic case can be found in the well-known piece from New Goose, a work that rescues the folklore character of children’s tales “Mother Goose” and renders it in new ways, close to the vicissitudes of her working-class environment:

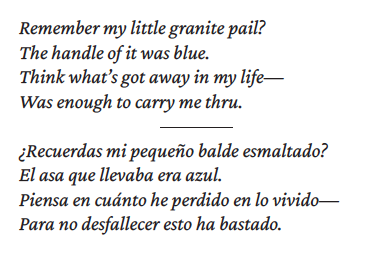

Some critics have compared this poem with Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow.” According to Rachel Blau DuPlessis, it works almost as an epitaph of solid matter remaining among the ruins (2009: 115). True to the spirit of Objectivism, life’s losses are visualized through a common object, and a very solid one, thus resisting the temptation for a more subjective, self-pitying mode of expression. This is a constant trait in Niedecker’s poetry, which never indulges in sentimentalism and faces life’s setbacks and constraints not with meek resignation, but in a matter-of-fact mood. In these four lines, and apparently dealing with an ordinary utensil in a plain, brief poetic form resembling a nursery rhyme, the poet takes a philosophical stance in regard to time and existence. For translation to be effective, the main challenge is to render the poem in the same unadorned way while not allowing it to fall short of its connotations. The risk is twofold: the poem can either sound too solemn or too trivial in its message.

All this requires close attention to the sounds, of course, but also to the choice of words in terms both of meaning and resonance. To start with, the end-rhyme has been located in lines 1 and 4 in the Spanish, instead of in lines 2 and 4 as in the original. A more accurate solution is hard to find. However, it seemed crucial to keep the rhyme at the end of the last line, because the closing of the poem relies on it not emphatically, but as a firm conclusion anyway. The rhyme transference works in combination with vocabulary adjustments: “has got away” is turned into “he perdido” (I have lost), whereas “to carry thru” becomes “no desfallecer” (not giving up). In the first case, the translation incorporates a personal subject that does not appear in the original version, though in its implicit form (“yo” he perdido); in the second one, the object pronoun “me” is transformed into the impersonal verb phrase “ha bastado” (it has been enough), as a compensation.

The main reason for these changes is related to rhythm: poems in New Goose must sound like folk song and are, consequently, constrained by meter. In fact, it is the combination of rhythm, rhyme, plain style, everyday context and deep resonance (almost as an understatement), that turns them into unique pieces at the crossroads of experimentalism and tradition. In the translation, formal constraints constitute a kind of advantage because the elements at play are reduced.

An account such as this of my experience of translating Niedecker must also describe its failures or problems for which I have found no satisfactory solution. These are mostly due to the intrinsic nature of Spanish and English and, more specifically, to sound-meaning associations that are impossible to reproduce. This occurs in a poem like “Tradition:” “Life / Thy will be done / Sun,” where the biblical style offers a pun on words with the homophony of “sun” and “son.” The Spanish translation in this case is simply “sol” (sun), plus an endnote explaining the pun. A similar problem is posed by the line “clause of claws” in “Foreclosure,” a poem in which Niedecker expresses the weariness of having to deal with the debts inherited from her careless father. The alternative chosen is to keep the meaning (“cláusula feral”) at the expense of sound, because the nuance of depicting the world of money and banks as a wild one seemed more important in this particular case.

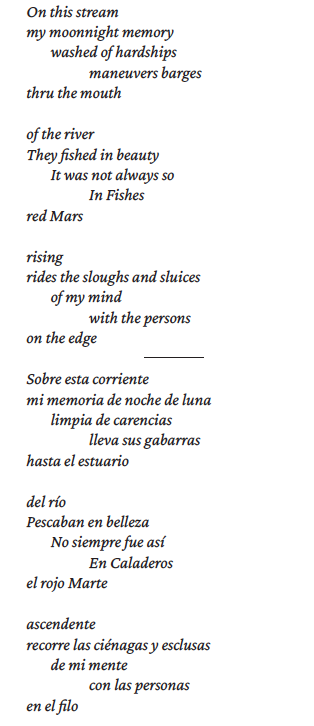

Likewise, in her poem “Paean to Place,” one of her best-known accomplishments with regard to sound, memory and condensation, it was impossible to keep alliteration in the group “sublime / slime- / song,” nor the homophonic/ pun that “new dead / leaves” triggers (the implicit oxymoron “dead/lives”). In addition, in “My Life by Water,” another most-relevant piece of her corpus, a perfect equivalent to the homophony between “letters” and “lettuce,” which places both terms at the same level of material and metaphysical importance through sound resemblance, could not be achieved. In all these examples, it was preferable to accept the frustration of not being able to go farther, rather than produce alternatives too far-fetched in relation to the poet’s choice. These shortcomings are usually compensated for a general, balanced tone that may leave the reader with a compelling impression of the whole text, notwithstanding specific defects. The translation of the closing stanza of the above mentioned “Paean to Place,” for instance, has been praised for the beautiful serenity it conveys, thus contributing to the final impression it leaves in English as well. Curiously enough, this is an example of an almost word-by-word translation, since no more complex strategies were needed:

An involuntary rhyme between “ascendente” (rising) and “mente” (mind) occurs, involving the smoothness of nasal and vowel sounds. As in the original version there is a recurrent /ai/ diphthong sound (rising/rides/mind) and a flowing /sl/ sound in “sloughs” and “sluices”, it becomes a natural alternative for the sound cadence that undoubtedly transmits the calmness of a successfully finished task: that of word, place, and memory coalescing in brilliant poetic synthesis. At this point, it should be highlighted that, for a poet so focused on sound, probably as a compensation for her poor sight, Niedecker was not favourable to public readings, since she held that poetry had to be read in silence and under a deep state of concentration. As a matter of fact, it took great effort to Cid Corman to record her shortly before her sudden death in 1970, being Corman’s the only recorded file available of her voice.

It goes without saying that all these translation proposals are far from definitive; another translator could come up with equally valid and perfectly grounded alternatives. In all cases, Spanish poetry readers are already accustomed to experimental poetry in their mother tongue and in foreign languages. Consequently, it is not unreasonable to assume that they will easily decode the grammatical, visual and phonic clues that the translator has identified in the source text, as well as the ways she has chosen to render them in Spanish by means of her own language tools and resources. From the point of view of gender, translating female avant-garde poetry helps overcome the myth, already more diminished than a few decades ago, about women poets’ alleged preference for poetry of a biographical tone or, more importantly, for the fusion between biography and identity, as if experimental poetic language left personal experience out; an issue strongly contested, among other critics, by Rae Armantrout (2007) and Marianne DeKoven (1989).

Oscillating between the two extremes of making a poem sound natural in the translation at the same time that its linguistic strangeness is exposed ultimately depends on what a certain instinct, or common “poetic” sense, dictates. Together with translation theory, this instinct contributes to the final golden rule of translation: the invisibility of the translator that must, by definition, preside over any translation task, so that the reader does not notice the finely tuned process that has taken place. In fact, it will be the Spanish readers who decide whether this principle has been thoroughly respected or not. As for the translator, the main satisfaction lies in the possibility he or she has had to blend linguistic strategies and poetic intuition in a single task, while neither betraying the source text nor underestimating the potential readers of the translated version. It is this ‘in-between’ nature of this task that makes the challenge such a fascinating one, in spite of its evident limitations. If any kind of poetry reflects and updates this process, experimental poetry makes it all the more evident.

In the chapter of personal reward, when translating poetry in general and Niedecker’s poetry in particular, a few intimate issues arise. Apart from the linguistic benefits of the discipline of translation there is also the larger-than-life experience of engaging with another identity. Lending one’s voice to the poetry of someone else, that is to say, to the deepest world of another self, provides an existential abode that leaves no translator indifferent or unaffected. We emerge from poetry translation turned into others, or into larger, more complex versions of ourselves. The resonance of successive authors accumulates within our own sense of selfhood. A trace of our temporary alignment with our most recently translated poet remains floating in the air, untranslatable, exactly like that unintelligible part of the poetry or traces of words that the poem contains, that we must try to translate against all odds. All in all, translation opens capricious criss-crossed paths between languages, between lives, and even between the living and the dead.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armantrout, Rae (2007): «Darkinfested», in Collected Prose. San Diego: Singing Horse Press, 63-72.

Armantrout, Rae (2007): «Feminist Poetics and the Meaning of Clarity», in Collected Prose. San Diego: Singing Horse Press, 38-48.

AUGUSTINE, Jane (1982): «The Evolution of Matter: Lorine Niedecker’s Aesthetic», Sagetrieb, 1, 277-284.

AUGUSTINE, Jane (1996): «What’s Wrong with Marriage: Lorine Niedecker’s Struggle with Gender Roles», in Jenny Penberthy (ed.) Lorine Niedecker: Woman and Poet. Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 139-156.

Benjamin, Walter (1997): «The Translator’s Task», TTR, 10:2, 151-165.

BLAU DUPLESSIS, Rachel (1996): «Lorine Niedecker, the Anonymous: Gender, Class, Genre and Resistances», in Jenny Penberthy (ed.) Lorine Niedecker: Woman and Poet. Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 113-137.

CARBAJOSA, Natalia (2016): «Las Brontë tenían sus páramos, yo tengo mis marjales: La poesía en el agua de Lorine Niedecker», Jotdown, <https://www.jotdown.es/2016/02/las-bronte-tenian-sus-paramos-yo-tengo-mis-marjales-la-poesia-en-el-agua-de-lorine-niedecker/>.

CRASE, Douglas (2013): «Niedecker and the Evolutionary Sublime», in Lorine Niedecker: Lake Superior, Seattle, Wave Books, 28-48.

DekovEn, Marianne (1989): «Male Signature, Female Aesthetic: The Gender Politics of Experimental Writing», in Ellen G. Friedman & Miriam Fuchs (eds.), Breaking the Sequence: Women’s Experimental Fiction, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 72-81.

Lemardeley, Marie-Christine (2007): «Poetry, Poverty, Property: Lorine Niedecker’s Quiet Revelations», EREA, 5:1, 7-13.

Middleton, Peter (1997): «Lorine Niedecker’s ‘Folk-base’ and Her Challenge to American Avant-Garde», Journal of American Studies, 31:2, 203-18.

Monstruos en su laberinto: Poesía y traducción (2006): Carlos Jiménez arribas , «Traducción y contemporaneidad: La lengua en acto»; Jordi Doce: «Traducir: Teoría»; Miguel Casado: «La experiencia de lo extranjero» <http://www.dvdediciones.com/monstruos_poesiaytraduccion.html>.

Niedecker, Lorine (2018): Y el lugar era agua: Antología poética, tr. Natalia Carbajosa, León: Ediciones Eolas.

Penberthy, Jenny (1993): Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky 1931-1970. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Penberthy, Jenny (2002): Lorine Niedecker: Collected Works, Stanford: University of California Press.

I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Jenny Penberthy for her invaluable help throughout the drafting and revision of this essay and to my fellow-translator Jean Gleeson Kennedy for her accurate suggestions. Moreover, the dissemination of Lorine Niedecker’s poetry in the Spanish-speaking world would have been impossible without the support of the editors Héctor Eolas and Tomás Sánchez Santiago.

1 I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Jenny Penberthy for her invaluable help throughout the drafting and revision of this essay and to my fellow-translator Jean Gleeson Kennedy for her accurate suggestions. Moreover, the dissemination of Lorine Niedecker’s poetry in the Spanish-speaking world would have been impossible without the support of the editors Héctor Eolas and Tomás Sánchez Santiago.

2 See, among others, the studies by Jane Augustine (1982 and 1996), Marie-Christine Lemardeley (2007) and Peter Middleton (1997).

3 The two Spanish poet-translators’ remarks mentioned in this essay (Carlos Jiménez Arribas, Jordi Doce) have been taken from the page “Monstruos en su laberinto: Poesía y traducción” (http://www.dvdediciones.com/monstruos_poesiaytraduccion.html).

4 Translation to the Eolas bilingual anthology (2018): “versos que se van arrastrando unos a otros como el agua arrastra al lodo; encabalgamientos que hacen flotar las categorías gramaticales lo mismo que el agua hace flotar los enseres; finales inconclusos que en realidad podrían ser el comienzo de una realidad inevitablemente cíclica.”

5 Douglas Crase (2013) attests to Niedecker’s hundreds of notes written during her journey around the Great Lakes.

6 It must be highlighted that the dove’s cooing sound has various different notes. Niedecker refers to the D tuning note to evoke the dove’s song in a general sense.