Judge a Book by its Cover: a paratranslational approach to the translation of The Communist Manifesto in the minority languages of the Spanish State

Robert Neal Baxter

Universidade de Vigo

This paper traces the history of the Asturian, Basque, Catalan and Galician translations of the Communist Manifesto, emphasising the role played by translation in its spread. The paper applies the concept of paratranslation to the wide array of translations in these languages to determine their underlying function. The results distinguish between several functions, ranging from political, commemorative and historical to academic and didactic editions. The paper concludes that, while all of the translations derive from the same original source text, they do not all perform the same function, rendering them not only autonomous of each other but also of the source text itself.

palabras clave: paratranslation, minority languages, Asturian, Basque, Catalan, Galician, Communist Manifesto.

Juzgar un libro por su cubierta: un enfoque paratraductológico de la traducción del Manifiesto Comunista a las lenguas minoritarias del Estado Español

Este artículo traza la historia de las traducciones al asturiano, euskara, catalán y gallego del Manifiesto Comunista, haciendo hincapié en el papel que jugó la traducción en su difusión. El artículo aplica el concepto de paratraducción a la amplia gama de traducciones a estas lenguas para determinar su función subyacente. Los resultados distinguen entre varias funciones, que van desde ediciones políticas, hasta conmemorativas, históricas, académicas y didácticas. El artículo concluye que, si bien todas las traducciones se derivan del mismo texto original, no todas cumplen la misma función, lo que las hace autónomas no sólo las unas de las otras, sino también del propio texto fuente.

key words:

paratraducción, lenguas minoritarias, asturiano, euskara, catalán,

gallego, Manifiesto Comunista.

recibido en enero de 2020 aceptado en julio de 2020

INTRODUCTION

The year 2018 marked the 170th anniversary of the publication of the Manifesto of the Communist Party. Despite its scant 23 original pages, this political pamphlet has been described as “one of the most influential and widely-read documents of the past two centuries” (Boyer, 1998: 151) and as “an essential classic in the fields of political science, economics and sociology owing to the influence that it has had on Western culture” (Argemí, 1999: 11)1. Indeed, Taylor (1967: 7) not only puts it on a par with Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, but goes so far as to place it “in the same class as the Bible or the Koran”.

Originally published anonymously in German in London, the Manifesto was written at the behest of the League of Communists by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, whose identity was only revealed two years later in the first English translation by Helen Macfarlane (1850), an early indication of the role translation was to play in its history. The text was revised the following year, resulting in the 30-page corrected version that was to serve as the basis for future editions.

This paper presents the paratextual elements (authorship, the contents of the prologues and epilogues, the translators’ backgrounds and political affiliations, graphic design, etc.) which all form an intrinsic part of the translations of the Communist Manifesto as published in Asturian, Basque, Catalan and Galician. By analysing these elements, the aim is to determine to what extent they can condition the way individual translations are perceived by the public, whereby the same source text can spawn translations that are functionally autonomous not only of each other but also of the source text itself.

The Communist Manifesto: an outstanding work for translation studies

As one of the most widely translated works in history (Rich, 2015: 7), the Communist Manifesto deserves to occupy a place in Translation Studies on a par with the Bible.

Indeed, from its very inception the Manifesto itself announced that it was to be translated into English, French, German, Italian and Flemish, with the first translation published in Swedish the very same year as the original. The concern on the part of Marx and Engels themselves with the translation of the Manifesto is a constant running throughout the eight different Prefaces penned by the authors. For example, Marx and Engels’ Preface to the 1872 German Edition opens with details of the very first translations and a series of further, extensive commentaries also feature prominently in Engels’ Preface to the 1888 English Edition and again in his Preface to the 1890 German Edition.

It is clear, therefore, that the huge scope of the translation processes to which the text has been subject throughout history can be seen as being central to the spread of the work, as Engels himself highlighted in his Preface to the 1888 English Edition.

In line with the tradition of the Internationals upon which the worldwide socialist movement reposed, a vast number of translations appeared in rapid succession (Paradela López, 2011), most notably thanks to the work of the Moscow-based Foreign Languages Publishing House (later Progress Publishers), responsible for translating and spreading the classics of Marxism-Leninism to the far corners of the Soviet Union and the former socialist countries, as well as neutral allies much further afield, e.g. Indian languages such as Assamese, Gujarati, Odia and Telugu and African languages, such as Hausa, Malagasy and Swahili2:

Some sense of the breadth of its influence can be gauged from the fact that some 544 editions are known to have been published in 35 languages […] even prior to the Bolshevik revolution; there must have been during that period other editions which are not known, and infinitely greater number of editions were to be published, in very many more languages European and non-European, after the Revolution of 1917 (Ahmad, 1999: 14).

Following the Sino-Soviet split, the Foreign Languages Press controlled by the Communist Party of China also took up the baton of disseminating such works as the Manifesto, including translations into Mongolian and Tibetan (see footnote below), as well as major Western languages.

Inextricably linked to the history of the Manifesto, translation can be seen to have played a key role in spreading the message of the text and as the concrete expression of the principle of “proletarian internationalism” crystallised in the world-famed closing words of the Manifesto “Workers of the world, unite!”. In a word: it is a work born to be translated.

Paratranslation as a heuristic tool

It is widely believed that translation is —if not exclusively, then at least primarily— an activity whose single most aim is communication, i.e. enabling people to access texts written in languages with which they are unfamiliar. This utilitarian view is supported and popularised not only by influential sources such as Wikipedia but also by specialists in the field, e.g. Blum-Kulka (2004 [1986]: 29).

It is, however, obvious that such an explanation cannot hold true in the case of multiple translations of the same original into the same language nor, in the specific case discussed here, translations into minority languages where all of the speakers could equally well access the work via the range of pre-existing Spanish translations (García González, 2005: 107).

Beyond such communicative explanations, paratextual analysis provides us with a heuristic tool to shed light not on how a translation is accomplished per se (i.e. the strategies adopted) but, at a much deeper level, why it is published in a certain way, i.e. the function(s) it is intended to perform based on the way it is perceived.

Genette (1987) coined the term ‘paratext’ as one of his five types of transtextuality developed in his earlier work Palimpsestes (1982). Working specifically within the field of paratranslation, i.e. paratextuality applied to Translation Studies, Yuste Frías (2015: 320) provides the following succinct definition of the paratext: “a textual accompaniment made up of discursive, iconic, verbo-iconic or purely material elements which serve to introduce, present, surround, accompany and envelop it physically (peritext) or to prolong it beyond the medium on which it was printed (epitext)”.

When applied to the field of Translation Studies, the concept of paratextuality becomes a useful tool (Nord, 2012: 407) for determining the underlying function behind any given translation vis à vis its target public (Yuste Frías, 2015: 322). Stratford and Jolicoeur (2014: 99-100) and Garrido Vilariño (2005: 31) note how the elements surrounding a text (the cover, the publishing company, the prologues and their authors, etc.) can condition potential readers even before they reach the contents of the text itself.

What makes the Communist Manifesto unique in the field of Translation Studies is the multiplicity of readings to which the paratextual elements present in the huge range of versions available lend themselves. A paratranslational analysis such as that proposed in this paper can help elucidate the motivations behind the way they are likely to condition the reader by defining its place and function within the literary system, e.g. whether it is perceived as a classic of World literature, a political call to revolution, a classic of Western philosophical thinking, a decorative object, etc.

As such, although they are all ostensibly derived from the same source text, different translations can convey substantially different and even conflicting messages above and beyond the actual contents themselves, in such a way that they should be seen as autonomous works in their own right.

a paratranslational chronology

Given the historical significance of the Communist Manifesto, it is hardly surprising that cultures should seek to bolster their literary canons by producing their own translations in accordance with Polysystems Theory developed by Even-Zohar (1990) and applied early on to cases such as Galician by Cruces Colado (1993). As a result, the Communist Manifesto has been translated into a surprisingly wide range of ‘minority languages’ (see Baxter, 2018; 2021). Indeed, it is noteworthy that languages with a very scant modern literature such as Cornish, Low German, Genoese or Venetian have felt the need to avail themselves of a translation of the Manifesto until as recently as 2018.

The translation of the Communist Manifesto has a particularly long and plentiful history as far as the minority languages of the Spanish State are concerned, dating back to the first Catalan edition of 1930 and continuing up to the present day. Indeed, the wide range of existing translations and reeditions, displaying an equally wide range of paratranslational differences (Baxter, 2021), effectively make the Manifesto the single most translated work in Basque, Catalan and Galician. It is also worth noting that retranslation of the same work is a luxury rarely engaged in by languages with such a limited readership, thus rendering this phenomenon all the more exceptional in the field of Translation Studies.

Chronologically, the translations analysed here, spanning a total of 86 years from 1930 to 2016, can be roughly divided into three main historical periods mirroring the contemporary political history of the Spanish State.

The first period: Pre- and Early/Mid-Francoism

Beginning with the end of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship and brought to an abrupt halt by the Spanish Civil War, this period revolves around the restoration of the Generalitat during the 2nd Spanish Republic and includes translations into Catalan only (Gasch Grau, 1975; Mota Muñoz, 2010), ranging from the first translation published in 1930, followed in rapid succession by three more until 1948.

All of the translations published during this period (as well as many of the later editions) are linked paratextually by a clear common thread running through them involving the political nature of many of the publishing houses involved as well as the political background and affiliation of many of the prologue writers and the translators themselves.

This was the case of Emili Granier Barrera, General Secretary of the Socialist Union of Catalonia (USC) and later Catalan State (EC), responsible for the first translation based on the French version produced by Marx’s own daughter, Laura Lafargue. This filiation ostensibly legitimised the use of a secondary text in the face of the pressing desire to produce a Catalan version, overriding considerations of translational rigour. Published as part of the Social and Political Studies collection by Arc de Barà, run by Manuel González Alba, a member of the Workers and Peasants’ Bloc (BOC) and later Catalan State-Proletarian Party (EC-PP), the text opens with a long introduction by Manuel Serra i Moret, founder of the USC and a comrade of the translator, which describes the “working-class and nationalist precepts which drove the Socialist Union and the Catalan State” (Rodés, 1976: 11).

The first translation based directly on the original German appeared five years later as a pamphlet published by Justícia Social (1935), the organ of the USC, reissued a year later by Atenea. The translation was the work of Pau Cirera i Miquel, also a member of the USC. It contains a prologue by Joan Comorera, the General Secretary the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC) that he helped found in 1936 when he was a member of the Executive Committee alongside the translator. Given the brevity of the prologue, it can be deduced that the seal of approval granted by its authorship was more important than its actual contents. The volume also contains a brief yet telling translator’s note stating that: “The aim of this translation is not to delight the reader, but to contribute towards the spread of the principles that comprise the basis of the modern proletarian and revolutionary movements”.

Very shortly afterwards, Edicions Europa-Amèrica, run by the Spanish Communist Party (Mota Muñoz, 2010), published a new translation in 1937 as part of its Popular Series of Socialist Classics under the label ‘P. Yuste impressor’, known for printing La Internacional Comunista, the organ of the Communist International. This double volume was accompanied by the Inaugural Manifesto and General Statutes of the International Workingmen’s Association. The editor’s note specifically indicates that it took as a source text that published by the Moscow-based Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute, effectively sanctioning it in the eyes of the official communist parties of the time, completed with a quote by Marx: “The conquest of political power has therefore become the great duty of the working class”. All of these paratextual elements serve to align the text with the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) and, in turn, with the official line of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Given the very short time that elapsed between this and the previous translation, it may be surmised that it was published “in response to the need to prepare communists at the time with whom the Europa-América publishing house was linked” (Rodés, 1976: 16). In other words, the PCE sought its own, authoritative translation, linked explicitly to the authority of the CPSU. This was the first of many partisan translations to be published in Basque, Catalan and Galician where, as in the case in hand, the authorship of the translation is either not mentioned or ascribed to an anonymous group of people not only in order to protect their identity but also intended to portray it as the collective work of the Party.

Finally, there are indications that a fourth, oft-cited translation (Riera Llorca, 1974; Rodés, 1976; Mota Muñoz, 2010) may also have been produced. Although the actual text itself is unavailable, having most likely been destroyed due to political in-fighting (Rodés and Ucelay-Da Cal, 1978: 53), the paratextual elements surrounding it are nevertheless of interest. The translation in question was to be published abroad in 1948 by Lluita (‘Struggle’), the official organ of the PSUC, directed by Joan Comorera (see above), clearly continuing the same political lineage, underscored by the fact that it was the work of Amadeu Bernadó i Calcató, who also became a member of the same party from which he was eventually expelled for aligning himself with the Catalanist wing, led precisely by Joan Comorera (Martínez de Sas and Pagès i Blanch, 2000: 2006). It is unlikely that any of these elements tying the publication to the PSUC would have gone unnoticed by a politically aware reader in Catalonia at the time.

This last example underscores the importance of paratextual analysis; while “there can be no translated text without its corresponding paratranslated paratexts” (Yuste Frías, 2015: 327, paraphrasing Genette, 1987: 10), it would seem that the paratext can indeed exist without a supporting text, in this case a translation.

The second period: Late and Post-Francoism

As was to be expected, the censorship under Franco’s dictatorship brought the publication of socialist literature to an abrupt halt, whilst at the same time targeting minority language and cultures (Rodés, 1976: 5).

This second period heralded the first Basque and Galician translations, together with a plethora of translations and reeditions in Catalan and —most significantly from a paratextual perspective— the incorporation of graphic design elements.

The first two Basque translations were published anonymously abroad owing to the censorship at the time: the first in 1971 by the Parisian Librairie du Globe printed in the Socialist Republic of Rumania, a safe-haven for communist literature; and the second across the border in Baiona/Bayonne in the Northern Basque Country within the French State in 1974 (Azurmendi, 1998: 44). The front cover of the 1971 edition shows a simple red stripe symbolising communism flanked by three horizontal stripes in the colours of the Basque flag. While this double motif is repeated in later editions —often reinforced by the inclusion of the hammer and sickle and other elements— its use in this edition may also be no accident inasmuch as it coincided with the emergence of ETA-pm and the leftist swing of many national liberation movements at the time.

The end of the dictatorships saw the first Basque edition published in the Southern Basque Country (Spanish State) in 1980 by Hordago, a company specialising in Basque-language literature based in Donostia/San Sebastián, the work of the author and member of the Royal Basque Language Academy (Euskaltzaindia), Xabier Kintana. Unlike Catalan and Galician, this is one of several bilingual editions in Basque, possibly indicative of the state of the language at the time, although this fails to explain the decision to include a parallel Spanish-language text in later editions which postdate the officialisation and wide-spread teaching of Basque, at least within the confines of the Autonomous Community (CAV). This edition returns to the same graphic leitmotif used in the 1971 edition, whilst reinforcing the communist facet by the addition of a simple silhouette of Marx and Engels.

The end of the Francoist regime heralded the first two Galician translations, both published in 1976 and separated only by a matter of months. The first was released by Nova Galicia as part of its Classics of Marxism collection. Its authorship is attributed to “a militant of the Communist Party of Galicia” identified as Xoan Andeiro, ostensibly a pseudonym (Luna Alonso, 2006: 194; Máiz Suárez, 1998: 29), indicative of the fact that the shadow of Franco still loomed large, which also explains why this edition was published clandestinely over the border in Lisbon.

It is interesting to note that both editions are linked to the PCE, legalised in April 1977, expressed explicitly in the case of the prologue to the Nova Galicia edition: “This is the first time the Communist Manifesto has been published in Galician. The initiative is due to the Communist Party of Galicia”, i.e. the PCE in Galicia.

In the case of the slightly later edition of the same year (1976), translated by the lexicographer, Isaac Alonso Estravís and published by AKAL, a publisher with strong ties to the Galician left despite being based in Madrid, the link with the Spanish Communist Party is established more covertly via the figure of Xesús Alonso Montero. This well-known PCE member since 19623, was responsible for the text that appears on the back cover and which, despite its brevity, is likely to be the first thing to capture a potential reader’s attention. This highly political text appeals to the need to apply Marx and Engels’ vision to overcoming the oppression of the Galician people, insisting upon the continued relevance of the Communism Manifesto, It also cites a well-known verse referring to Galician as “the proletarian language of my people”, from the poem Deitado frente ao mar (‘Lying facing the sea’) by the Galician poet Celso Emilio Ferreiro, one of the cofounders of the Galician People’s Union (UPG), the Marxist-Leninist patriotic party founded in 1963 and which continues to this day.

Although both are cheaply produced, perhaps in order to encourage their spread as widely as possible amongst the working class, they include a number of significant graphic elements, all of which are exclusively communist in nature, i.e. not including any elements alluding especially to their Galician nature, unlike the Basque editions described above. The predominantly red cover of the Nova Galicia edition is emblazoned with a black-and-white etching of Marx. The allusions are clearer in the case of the AKAL edition which reproduces black-and-white photos of the two authors on the inside pages in line with the Spanish edition of the Manifesto published in the USSR, in an attempt to identify it visually with the well-known Progress Publishers at the time, thus implicitly reinforcing its ties with the authoritative publishing house of the Soviet Union. In this instance, it is worth noting that the plain red cover is not used to symbolise communism, as it is common to the whole of the collection regardless of the subject matter.

In either case, the accompanying peritexts are highly partisan, reflecting the clearly proselytising motivation behind the translations, as stated clearly in the short introduction to the Nova Galicia edition: “With this publication we hope to contribute to the spread of Marxism amongst the Galician people and especially its youth”. However, as unsurprising as this political motivation may seem, this need not necessarily be the case, as indeed later editions published in periods less influenced by Marxist thinking show.

The year 1976 was to be especially fruitful for the Catalan language, with a reedition of Pau Cirera’s translation, coinciding with the referendum on the Political Reform Act which officially marked the end of the Francoist regime. This first reedition of a pre-existing translation was released by Undarius, a publishing house specialising in politics and especially Catalanism, including Joan Comera’s Socialisme i qüestió nacional (‘Socialism and the National Question’). This edition of the Manifesto differs significantly from the first edition in several regards and is especially noteworthy owing to its array of accompanying peritexts.

As well as a final biographical index and a series of explanations regarding certain historical figures and political concepts, the primary peritext is a 12-page presentation by Jesús M. Rodés Gràcia, an erstwhile member of the PSUC arrested for his political convictions (Bastardes, 1989) and described by Robles (2014) as a “pro-soviet communist”. While he opens by describing the Manifesto as a part of the “universal heritage of humanity” and underscores the important contribution made by the translator, in keeping with the tradition marked out by the earlier prologues by Manuel Serra i Moret and Joan Comorera (both of which are reprinted in this volume together with Pau Cirera’s original translator’s note), this introductory text serves as a platform to trace the history of socialism in Catalonia through the existing editions of the Manifesto, placing special emphasis on the first two. As such, it can be clearly seen as a continuation of the same political lineage combining socialism with Catalanism.

Only one year later saw the publication of what was to become the most frequently reedited translation in Catalan (see below). The two companies responsible, Edicions 62 and La Magrana, were cofounded by the anti-francoist activist, Ramon Bastardes i Porcel, and Jordi Moners i Sinyol, a founding member of the Socialist Party for National Liberation (PSAN), also responsible for the translation of the Manifesto itself as well as other Marxist classics into Catalan, most notably Capital (6 tomes, 1983) and The German Ideology (2 tomes, 1987), thereby clearly harking back once again to the figure of translator cum political activist.

It is a very basic yet complete edition, including all of the canonical original prologues and footnotes (which do not appear, surprisingly, in all editions). Nevertheless, for the first time in the history of the Catalan translations, it is bereft of any introduction of its own, barring a short paragraph stretching to barely eight lines.

No doubt with a view to enabling any worker to acquire the work at the modicum price of 70 pesetas (printed on the back), the graphics are minimal, involving the typical, rudimentary portraits of Marx and Engels on the front cover and on the back cover simply an excerpt from the opening of the Manifesto beginning with the famous sentence “A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of Communism”.

The third period: Post-transition

The first translation published following the complete instauration of the current parliamentary constitutional monarchy and the establishment of the Autonomous Communities when Basque, Catalan and Galician became co-official languages was yet another translation in Catalan published in 1986. However, from a paratextual perspective it deviates radically from the previous translations in a number of important ways and constitutes the first of its kind.

Its publication outside Catalonia in Madrid by Alhambra in conjunction with Oikos Tau reveals how publishing companies suddenly became interested in the new (and lucrative) markets opening up for books in the newly co-official languages, especially those destined to be used in schools with a large potential audience. In fact, it is significant that this Catalan version is identical to the schoolbook originally published by Alhambra/Longman in Spanish in 1985.

Figure 1. Neutral cover of the Catalan translation published for use in schools by Alhambra (1986)

Although the translator, Rosa Maria Borràs, was a member of the PSUC and later the PSUC-viu (Mientras Tanto, 2008), this has no bearing on the way the genre of the text is to be interpreted. This edition was clearly intended to be read as a neutral, scholarly text of modern philosophy, as indicated by the title of the collection Classics of Thought, further reinforced by its sober cover design, shared by the other books in the collection, including authors such as Aristotle, Descartes, Kant, Plato, etc. This double volume also includes Marx’s eleven short philosophical notes entitled Theses on Feuerbach, again reinforcing the way the Manifesto should be seen as a classic of philosophy rather than a political call to action per se.

The two paratexts on the back cover serve to present and situate the work. The general introduction underscores the need to teach philosophy as a basis of the history of humanity and announces that the reader will find exercises, reading notes and a series of documents regarding the author and his work. The editor then provides a brief introduction to the Manifesto itself, once again stressing its place as a key work set within the realm of philosophy, while the use of cartoons to accompany the commentaries indicates that it is clearly designed to appeal to a younger audience, specifically secondary school students

The editor, Anselmo Sanjuán Nájera, who has published a series of papers on philosophy4, was responsible for the 50-page-long introduction, detailed timeline and study guide which accompany the text, completed with a glossary and bibliography.

This was followed in 1997 (reed. 2002) by another translation in Catalan by Glòria Battestini. It too was the twin of an earlier Spanish translation by the same publisher, Librería Universitaria Barcelona, carried out by Paco Leiva. However, unlike the Alhambra edition, this is an extremely streamlined publication, with no accompanying peritexts (no introduction, not even any of the original prologues, etc.) and with a very basic cover design showing portraits of the authors in black and white. It can be interpreted as being intended as a neutral translation issued by an academic publisher targeted at university students requiring a cheap, basic text of the work.

One year later (1998) saw the release of a new type of Manifesto, quite different in many respects from those that preceded it. Although the actual text itself was essentially a reedition of Jordi Moners’ translation, it is surrounded by a series of paratextual elements that make it a distinct work in paratranslational terms.

It is the only edition published by a public body, namely Sueca town council, and also the only version published to date in the Valencian version of Catalan, adapting the original translation accordingly. It is also the only commemorative edition published in Catalan (other commemorative editions were later published in Galician), to mark the 150th anniversary of the Manifesto. It stands out by dint of its rather sumptuous physical outward appearance: considerably larger in size, printed on high quality paper and protected by a decorative cardboard sleeve, with the title picked out in letters designed to resemble gold-leaf.

The prologue by the Professor of Contemporary History at the Universitat de València, Pedro Ruiz Torres, also marks a distinct turn towards a much more high-brow academic tone in order to wreathe the edition in an aura of prestige. In what is essentially a historiographical portrait of Marx, he does include the de rigueur nod at the continued relevance of the Manifesto, whilst at the same time introducing a hint of criticism, cautioning the reader against applying it in a “doctrinal” or “dogmatic” manner.

This edition is clearly intended as a commemorative book/object enabling the corporation of the town hall to make a symbolic statement regarding their political leanings; clearly to the left but free from the “dogmatism” of the traditional communist parties.

Nothing could be further from the original translation by Jordi Moners on which it was based, nor indeed the later reeditions published by Tigre de Paper (2015; 2017), which return to the very humble appearance of 1977, providing a cheap and accessible edition in line with the spirit of Moners’ translation, even going so far as to include a Creative Commons license. The iconography on the front cover of these editions by Tigre de Paper is clear and unabashed: a large yellow hammer and sickle set against a red background. This is accompanied and reinforced by the short text on the back cover that states unequivocally that the Manifesto is as useful as ever for “combatting the material reality that hits the working class especially harshly”.

El Grillo Libertario (‘The Libertarian Cricket’) distributes yet another version of Moners’ translation published by the elusive CyD. However, this anarchist distributor does not seek to cast the Manifesto in a positive ideological/political light, as reflected by the fact that it is classified in a section entitled “authoritarian communism”5. Also in line with the libertarian thinking behind this edition, it is interesting to note from a paratranslational perspective that it is merely a rather shoddy, photocopied facsimile of Moners’ translation, with absolutely no mention of the original author or any possible copyright and includes no place or date of publication.

What this series of (re)editions clearly illustrates is the ambiguous nature of translation itself, whose intended role can vary substantially and can only be fully understood via a global paratranslational analysis taking into account all of the and/or the lack of accompanying paratexts and epitexts which define it. In a word, while all of these editions take the same translated text by Jordi Moners as their basis, they are, to all effects and purposes, different translations.

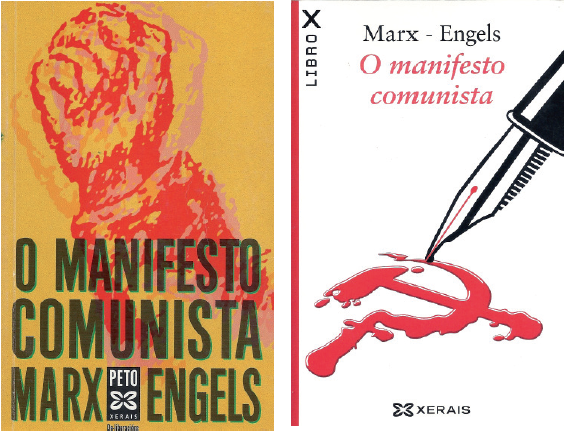

It wasn’t until 1998 that the reputed Xerais company released the first Galician translation using the current official norms approved fifteen years earlier under the auspices of the Royal Galician Academy (RAG) and the Galician Language Institute (ILG) in 1982. The paratextual elements are to a certain extent in conflict with one another. On the one hand, we see the raised fist in red against a yellow background on the front cover. This is complemented on the back cover by an excerpt taken from Leer el Manifiesto Hoy (‘Reading the Manifesto Today’) by Juan Ramón Capella, close to the PCE and IU6, where he defines the Manifesto as a “classic of the movement for emancipation” inspired by a “loathing for injustice” and refers to the class struggle and the liberation of the “exploited and oppressed class”. All of these elements tend to identify this edition as a political work, inscribing it in line with the tradition that began with the two earlier Galician editions.

On the other hand, however, there is also a very clear intention to mark it out as a technically authoritative version. It stresses that the translation was the work of the professional translator Franck Meyer directly from the original text in German. It also includes, very unusually, a translator’s introductory note, setting it at the extreme opposite of other clearly partisan works, where the translator is intentionally anonymised. These preliminary elements serve to alert the reader to the fact that this is a ‘serious’ and translationally rigorous edition, subscribing to a rather traditional view of translation, when the translator states that he sought to provide “the most literal translation possible” as opposed to “a ‘primped’ version [...] which would gloss over the unresolved problems and imply the existence of someone who decides what kind of primping to apply”.

This air of academic seriousness is further bolstered by the long introduction by Ramón Máiz Suárez, Professor of Political Sciences and Administration at the University of Santiago de Compostela, who adopts a primarily historical and aseptic approach towards the work, in stark contrast to the political-ideological tone of the partisan translations issued by Abrente and the Friedrich Engels Foundation (see below).

It is also important to note that this edition was published as part of a collection of paperbacks comprising a series of Western classics, ranging from Descartes to Voltaire, which further helps to convey the idea that it is a serious classic rather than a pamphlet calling for political revolt.

This translation was reedited twice, once by the Spanish-language newspaper La Voz de Galicia in 2005 and again by Xerais in 2015. Notwithstanding the fact that all three editions share the same base text, there is a series of key paratextual elements which make them stand apart from each other as different translations from a paratranslational perspective.

First and foremost, the La Voz de Galicia edition is a prime example of the ‘book/object’, essentially devoid (indeed voided) of any real political content, much more so in fact than the Catalan edition published by Sueca town council in 1998 (see above). It was released as part of a collectible series entitled Galician Library of Universal Classics sold alongside the newspaper over a period of several months, described by Luna Alonso (2006: 187) as part of the wider drive to revitalise the Galician language and culture by reinforcing its literary canon by incorporating prestigious works of World literature. The cover design of this hardback edition (the only one of its kind) is the same as for the rest of the collection and bears no relation whatsoever to the theme of the Manifesto, designed exclusively to look good as part of the complete collection on a shelf: it is intended to be seen rather than read and much less acted upon. As such, it is of little surprise that it is bereft of any of the paratextual elements which might appeal to a reader interested in the subject matter, having even gone so far as to omit the original introduction and translator’s note.

The version republished by Xerais is of particular interest because it demonstrates how even a reedition of the same base text by the very same publishing house can lead to sensibly different products as regards the impression conveyed by them via the use of differing paratextual elements. This edition diverges radically not only from the original edition but also from all of the other editions analysed here by dint of the new cover design: a hammer and sickle drawn in dripping blood by a fountain pen. This negative message can only be construed to mean that the Manifesto has led to massacres in the name of communism.

Figures 2-3. Covers of the first (1998) and second (2015) Galician editions both published by Xerais

Returning to 1998, Abrente Editora, the official publishers of the communist and independentist party Primeira Linha whose espoused aim is “to contribute towards the preparation of the Galician revolutionary militants”7, released its own ‘translation’ of the Manifesto the self-same year as the first edition by Xerais. The two could barely be more different at almost every level, not least the name of the collection to which the Abrente edition belongs, i.e. the Library of Marxism-Leninism. Although issued to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the Manifesto, just as the later reedition in 2004 (see below) was timed to coincide with the 80th anniversary of the death of Lenin, this is far more than a merely commemorative edition.

Both editions published by Abrente differ from the rest by their choice of reintegrationist Galician – carried much further in the second edition – that aligns the language more closely with standard Portuguese, a linguistic choice often identified with the independentist movement. Also, unlike the other editions, it is not actually an ex novo translation, but rather the orthographic adaptation by an unnamed group of people (in line with other partisan versions) of several Portuguese translations. In contrast with the translation by Franck Meyer that was interested in translational accuracy, this edition puts the ideological needs of the Party first, as clearly stated in the eight-page Prologue by the Central Committee: “the aim is not to carry out an academic or stylistic analysis of a classical essay, nor to provide a historical or philological reading … [It is] aimed at the men and women for whom K. Marx and F. Engels wrote the whole of their exceptional work: the working class and the popular sections of society as a whole, in order for them to become aware of their oppression and to fight for their necessary emancipation”.

The prologue is also markedly partisan in character, eschewing “the failed experiences of Stalinist bureaucratic authoritarianism”. In a similar vein, the succinct, three-paragraph-long prologue to the later 2004 edition goes on to emphasise the continued relevance of the Manifesto, linking social emancipation and national liberation, in line with the thinking of the party behind the publication.

These elements are also reinforced by the cover design which is essentially similar in both cases from a semiotic perspective, with portraits of Marx and Engels against a red-coloured background, together with the inside flaps that underline the revolutionary aspect of Marx’s work and include a list of the works published to date by Abrente in the collections entitled Galician Library of Marxism-Leninism, International, Political texts and Constructing Galicia, highlighting at first glance the ideology behind the publishing enterprise/party responsible.

All in all, from a paratranslational perspective, these two editions by Abrente could be described as ‘instrumentalist’ and partisan in a way similar to those published by the Friedrich Engels Foundation, serving not only to divulge the message of the Manifesto itself, but also to spread the political line of the party, which this prestigious work in turn also serves to legitimise.

In that same year (1998), Jakin republished the Basque translation originally produced by Xabier Kintana, but with significant paratextual differences between the two. The new, graphically bland cover design shared by the whole of the collection conveys an air of neutral academic seriousness, despite the fact that the volume contains none of Marx and Engels’ original prologues or footnotes. The collection itself is dedicated to classical and latter-day philosophers and their works, from Aristotle and Nietzsche to Badiou. The extensive, 40-page-long introduction entitled K. Marx’s evolution up to the Manifesto. From Hegelian idealism to historical materialism by the prestigious Basque writer and philosopher, Joxe Azurmendi, is also notably academic in tone, all of which, together with the contents of the brief bibliographical details of the authors on the back cover, combine to create an overall impression of the work as an essentially philosophical rather than political text.

This contrasts strikingly with the political function conveyed by the graphics of the original front cover, again demonstrating the way that the same text/translation can be portrayed differently by dint of the paratexts in which it is wrapped.

However, it should be said that the initial impression of overall blandness conveyed by the outer wrappings of the Jakin reedition sits uncomfortably with the epilogue written in 1979 by Mario Onaindia, at the time General Secretary of the Marxist and nationalist Party for the Basque Revolution (EIA), which lends a far more political twist to the volume, albeit at the very end as an apparent afterthought.

The year 1999 saw the publication by Editora del Norte, specialising in Asturian literature, of the first (and to date only) translation of the Manifesto into Asturian, the work of the author and translator Pilar Fidalgo Pravia. The front cover is clearly militant in style, showing three rugged, bearded factory workers in overalls and shirtsleeves staring defiantly ahead in the centre ground backed by a throng of workers, all flanked by images of chains, cogs and smoking chimneystacks reminiscent of the Industrial Revolution. The title of the work is also bedecked by a large hammer and sickle. The translation opens with an extremely brief, two-page introduction by Gaspar Llamazares whose political activism began in the Asturian branch of the PCE, before going on to become the leader of the United Left (IU) in 2000. As we have seen in previous cases, the interest of this introduction lies not so much in its contents per se, as in the political cachet associated with its author. The linguistic prestige is provided by the almost equally short preface by the erstwhile President of the Asturian Language Academy, Xosé Lluis García Arias, entitled Un testu clásicu (‘A classical text’), thereby seeking to boost the Asturian literary canon. Overall, the paratextual elements clearly mark this edition out as an eminently political work.

Figure 4. Cover of the only Asturian translation, published by Editora del Norte (1999)

As of 2005, the Trotskyist Fundación Federico Engels (‘Friedrich Engels Foundation’) launched a series of translations of the Manifesto into the co-official languages of the Spanish State, all based upon the much earlier Spanish ‘base’ edition published by the same Foundation (1996; 2004): namely Catalan (2005; 2013), Basque (2007; 2014) and Galician (2009).

Despite a series of minor differences, all of these editions share a number of key paratextual features, making them to all effects one and the same translation from a paratranslational point of view and with regards to the function they are intended to perform.

As in other partisan editions, all of these translations are systematically attributed to an anonymous “group of translators of the F. Engels Foundation”, thereby effectively collectivising the work above and beyond any individual effort. These unnamed translators basically act as the conduit for a series of Trotskyite and partisan propaganda: all of the translations open8 with the extensive introduction originally written in 1996 by the well-known Trotskyist theorist and leading member of the International Marxist Tendency (IMT), Alan Woods. They all also close with a wealth of pages dedicated to directly promoting not only the Foundation itself and the works it publishes —many by Trotsky and Trotskyist theorists— but also the newspaper El Militante (‘Militant’) the review Marxismo Hoy (‘Marxism Today’) and the Cuadernos de Formación Marxista (‘Marxist Training Booklets’), all with subscription bulletins.

It is interesting to note that the 2014 Basque reedition was published in conjunction with the Sindicato de Estudiantes (‘Union of Students’), effectively linking it ideologically to this Trotskyist current. The Union’s logo appears prominently on the front cover, showing a group of workers protesting with raised fists in front of a boss. This unusual use of a cartoon-like caricature is clearly intended to appeal to a younger audience, as reflected in the picture of students taking part in a demonstration on the back cover. It also includes an introduction of its own, emphasising the on-going relevance of the Manifesto and the need to take to the streets and protest written by the Union’s then General Secretary.

Another new and completely anonymous Catalan translation appeared in 2007 published by Aeditors. The front cover reproduces Lewis Wickes Hine’s photograph Power house mechanic working on steam pump (1920) set against a red background, representing the working class and socialism. This message contrasts strikingly with —and even contradicts— the short, yet pithy, introduction by Xavier Vega who, in barely four pages, manages to describe the Manifesto as a “brilliant booklet” and a “classic of political literature”, whilst at the same time decrying it as brimming with “messianic vehemence” with a less than veiled criticism of the way its teachings have been applied in practice: “while horrors have been committed in the name of Marxian praxis, a struggle has also been fought to dignify the condition of those who are marginalised”. However, on the whole, the introduction tends to situate the Manifesto as a key philosophical text on a par with Descartes’ Discourse on the Method, placing it paratranslationally with the other pedagogical/philosophical editions published by Alhambra (1986) and —albeit perhaps to a lesser extent— Librería Universitaria Barcelona (1997). Vega doesn’t hesitate to describe the latter as “drab and verging on the unsound”, despite the fact that the Aeditors edition not only fails to identify the translator, but also saw fit to omit all of the usual canonical original prologues and footnotes by Marx and Engels.

The year 2010 saw the publication of the only trilingual edition in Basque, French and Spanish, evidently designed to cover the needs of the whole of the historical Basque Country. In common with most other partisan editions, it was published anonymously by Kimetz (lit. ‘Seed’) which defines itself on its website9 as a Basque communist organisation.

In a clear declaration of its ideological stance and its Marxist-Leninist principles, the cover illustrations of the joint authors Marx and Engels are supplemented with that of Lenin. Although only four paragraphs long, the anonymous introduction also makes very clear the Party’s ideological affiliation, with praise not only for Marx, Engels and Lenin, but also for Mao and Stalin.

As in the case of the Friedrich Engels Foundation, this version stands as another very clear example of a highly partisan edition, whose prime aim is to uphold and spread the message of the party responsible for publishing it, illustrating the fact that, through the use of different paratextual elements, the same base text (i.e. the Manifesto itself) can not only be made to fulfil different functions (decorative, political, philosophical, etc.), but can even be used to legitimise opposing political positions within the same spectrum, in this case Stalinism (Kimetz edition) and Trotskyism (Engels Foundation editions).

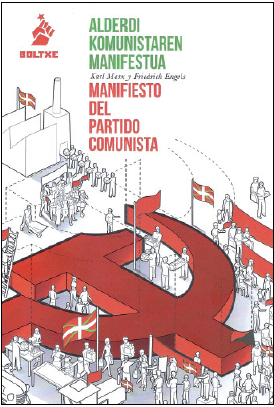

One of the most recent versions available is the bilingual Basque/Spanish edition published in 2016 by Boltxe. It is firmly rooted in the militant tradition, combining graphic elements representing the communist and pro-independence elements seen in earlier editions and reflecting this group’s political stance10.

Figure 5. Cover of the Basque edition by Boltxe (2016) combining Basque and communist motifs

The front cover is emblazoned with a huge red, three dimensional hammer and sickle as its centre piece with several Basque flags flying prominently above and around it, all set within groups of workers from different sectors, including a group of demonstrators. In common with the other partisan editions, what appears to be a new translation when compared with previous versions is once again shrouded in anonymity. The very short introduction emphasises the relevance of the Manifesto today and urges the Basque working class to read it. Finally, as in the case of the Catalan edition published by Tigre de Paper, this translation also has a Creative Commons licence in order to encourage its spread beyond any financial constraints.

Finally, the most recent translation to date is a new Catalan edition published by Taifa Llibres in 2017, coinciding with the centenary of the Russian Revolution and the eve of the Bicentenary of the birth of Karl Marx. In many ways, it stands out visually from the previous editions as a very sleek volume, with the main cover and inside title pages stylishly printed in white on black. Its red outer band and elegant dust jacket inscribed with the opening words of the Manifesto in a faux Cyrillic typography are clearly reminiscent of Soviet propaganda posters.

The translation itself was the work of the literary translator Núria Mirabet i Cucala, whose name figures prominently below that of the author of the prologue on the outer band, which would tend to indicate that it is to be viewed as a serious, literary work. However, on closer inspection, the choice of the author of the extremely long prologue, which runs to nearly 50 pages divided into eight separate chapters and occupying a third of the book, contradicts the initial impression that this may be another example of a decorative book/object. While overtly political in tone, unlike other ideological prologues which tend to lean towards various hues of communism or socialism, the author, Santiago López Petit, is a philosopher renowned for his libertarian anarchist views and activism, thus putting yet another ideological spin on the way the text is intended to be read and interpreted.

conclusions

Given the impact that the Manifesto of the Communist Party has exerted and continues to exert on the history of humanity, together with the key role that translation has played since the very outset, even in the minds of the authors themselves as expressed in their canonical prologues to the text, this particular work definitely warrants a special place in the field of Translations Studies.

Translation plays a significant role in the development and revitalisation of the literary canon of minority languages and it is, therefore, significant to note that this is one of the few works to have been constantly and repeatedly reedited, reprinted and retranslated into languages such as Basque, Catalan and Galician in a very long-standing tradition stretching back over nearly a century up until the present day, a phenomenon which is wholly unheard of for any other translated work into languages such as these.

While the fortunes of the translation of the Manifesto can be seen to run parallel to the political history of the Spanish State, a paratextual analysis reveals that it is also directly linked not only to the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) —as one might expect— but also exhibits very strong ties to other political parties specific to each the historical nations where the translations were produced, notably socialist/communist and pro-independence/nationalist parties.

A paratranslational analysis of the textual elements (the contents and political affiliations of the authors of the introductions, prologues and epilogues, the name and background of the translators, etc.), together with graphical elements (most notably the cover design) that envelop any given translation, reveals that, alongside the expected political readings attributed to the Manifesto (some with a very clear partisan agenda), the paratexts can condition the way a text/translation is perceived and interpreted. Long before they actually reach the main text itself, these elements allow/lead potential readers to allot the work to a particular genre, ranging from a primarily political, philosophical or historical document from either a militant, academic or pedagogical perspective, to an essentially decorative element in the form of a book/object devoid of any political drive.

What this indicates is that while all of the translations derive from one and the same original source text, the inevitable incorporation or absence of different paratextual elements means that they do not all necessarily perform the same function with regards to the potential target public. This effectively renders individual translations and even reeditions of the same translated text not only autonomous of each other but also of the source text despite containing similar or even identical contents.

As such, this type of paratranslational approach proves to be a useful heuristic tool for analysing and understanding the way translation has depicted such influential texts as the Communist Manifesto through time in line with the specific needs of publishers and political parties and could well be applied to other types of key translated works.

bibliography

Ahmad, Aijaz (1999): “The Communist Manifesto In Its Own Time, and In Ours”, in Karat Prakash (ed.), A World to Win: Essays on the Communist Manifesto, New Delhi: LeftWord, 14-47.

Argemí, Lluís (1999): “El Manifest comunista en la història del pensament”, Papers. Revista de Sociologia, 57, 11-20.

Azurmendi, Joxe. K. (1998): “K. Marxen eboluzioa Manifestu-ra arte. Hegelen idealismotik materialismo historikora [‘K. Marx’s evolution up to the Manifesto. From Hegelian idealism to historical materialism’]”, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Alderdi Komunistaren Manifestua [‘Manifesto of the Communist Party’], Donostia/San Sebastián: Jakin, 7-48.

Bastardes, Enric (1989): “Jesús María Rodés. De la cárcel por comunista a la enseñanza policial”, El País, 4 January, <https://elpais.com/diario/1989/01/04/ultima/599871603_850215.html> [Accessed: 06-VII-2020].

Baxter, Robert Neal (2018): “Análise paratradutiva das diferentes edicións do Manifesto do Partido Comunista ao galego: a ideoloxía das marxes”, Revista Galega de Filoloxía, 19, 31-60.

Baxter, Robert Neal (2021. In press.): “Història i anàlisi paratextual de les traduccions del Manifest del Partit Comunista al català”, Quaderns: Revista de traducció, 28, s.p.

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana (2004 [1986]): “Shifts of Cohesion and Coherence in Translation”, in Lawrence Venuti (ed.), The Translation Studies Reader, London and New York: Routledge, 298-313.

Boyer, George R. (1998): “The historical background of the Communist Manifesto”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12/4, 151-174.

Cruces Colado, Susana (1993): “A posición da literatura traducida no sistema literario galego”, Boletín Galego de literatura, 10, 59-65.

Even-Zohar, Itamar (1990): Polysystem Studies, Durham (NC): Duke University Press.

García González, Marta (2005): “Translation of minority languages in bilingual and multilingual communities”, in Albert Branchadell and Lovell Margaret West (eds.), Less Translated Languages, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 105-123.

Garrido Vilariño, Xoán Manuel (2005): “Texto e Paratexto. Tradución e Paratradución”, Viceversa. Revista galega de tradución, 9-10, 31-39.

Gasch Grau, Emili (1975): “Difusió del Manifest comunista a Catalunya i Espanya (1872-1939)”, Recerques: Història, economia i cultura, 5, 21-30.

Genette, Gérard (1982): Palimpsestes. La Littérature au second degré, Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Genette, Gérard (1987): Seuils, Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Luna Alonso, Ana (2006): “A Biblioteca Galega dos Clásicos universais”, Viceversa. Revista galega de tradución, 12, 187-201.

Máiz Suárez, Ramón (1998): “Marx, Engels e a revolución de 1848”, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, O Manifesto Comunista, Vigo: Xerais, 5-29.

Martínez de Sas, María Teresa and Pelai Pagès i Blanch (2000): Diccionari biogràfic del moviment obrer als països catalans, Barcelona: Universitat Barcelona y Abadia de Montserrat.

Mientras Tanto (2008): “Maria Rosa Borràs: in memoriam”, Mientras Tanto, 107, 5-9.

Mota Muñoz, José Fernando (2010): “‘Un espectre atemoreix Europa: l’espectre del comunisme’. Vuitanta anys de la primera traducció al català del Manifest comunista”, Associació Catalana d’Investigacions Marxistes (ACIM), <http://www.fcim.cat/bloc/2010/10/05/un-espectre-atemoreix-europa-lespectre-del-comunisme-vuitanta-anys-de-la-primera-traduccio-catalana-del-manifest-comunista/> [Accessed: 06-VII-2020].

Nord, Christiane (2012): “Paratranslation – a new paradigm or a re-invented wheel?”, Perspectives. Studies in Translation Theory and Practice, 20/4, 399-409.

Paradela López, David (2011): “‘Un mundo que ganar’: la traducción del Manifiesto Comunista”, El Trujamán. Revista diaria de traducción, 19 August, <https://cvc.cervantes.es/trujaman/anteriores/agosto_11/19082011.htm> [Accessed: 06-VII-2020].

Rich, Adrienne (2015): “Preface: Karl Marx, Rosa Luxemburg and Che Guevara”, in Deborah Shnookal (ed.), Manifesto: Three Classic Essays on How to Change the World (Ernesto Che Guevara, Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, Rosa Luxemburg), Washington: Ocean Press, 1-10.

Riera Llorca, Vicenç (1974): “Passada la ratlla: Sobre les versions catalanes d’un text cèlebre”, Serra d’Or, XVI/172, 97.

Robles, Antonio (2014): Historia de la Resistencia al Nacionalismo Catalán, Pennsauken: BookBaby.

Rodés, Jesús María (1976): “Presentació”, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifest del Partit Comunista, Barcelona: Undarius, 5-17.

Rodés, Jesús M. and Enric Ucelay-Da Cal (1978): “Una vida significativa: Amadeu Bernadó”, L’Avenç, 11, 50-53.

Stratford, Madeleine and Luis Jolicoeur (2014): “La littérature québécoise traduite au Mexique: trois anthologies à la Foire internationale du livre de Guadalajara”, Meta: journal des traducteurs / Meta: Translators’ Journal, 59/1, 97-123.

Taylor, Alan John Percivale (1967): “Introduction”, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, F., The Communist Manifesto, London: Penguin, 7-47.

Yuste Frías, José (2015): “Paratraducción: la traducción de los márgenes, al margen de la traducción”, Documentação de Estudos em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada, 31, 317-347.

1 Unless stated otherwise, all translations of quotations in languages other than English are by the author.

2 See the "Cross-Language Index" at the Marxists Internet Archive (https://www.marxists.org/xlang/index.htm) and "Communist Manifesto" in 75 languages at Comintern (S-H) (http://ciml.250x.com/archive/marx_engels/me_languages.html).

3 Biblioteca de Galicia: http://bibliotecadegalicia.xunta.gal/es/catalogos-coleccions/biblioteca-de-xesus

4

See Dialnet: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/autor?

codigo=4203795.

5 The work appears to be no longer available on the site (https://www.elgrillolibertario.org/botiga).

6

See Primera escuela de octubre. Comisiones Obreras de Asturias (http://www.fundacionjuanmunizzapico.org/

EscuelaDeOctubre/2009/2009_05.htm).

7 From the publisher's site: http://www.primeiralinha.org/abrenteditora.htm

8 With the notable exception of the Catalan reedition of 2012, when the by then 20 year old introduction was no doubt judged to be too outdated.

10 See their official website: https://www.boltxe.eus/.