Censorship and Translation into Spanish of the Lesbian Novel in English: the case of Rubyfruit Jungle (1973)

Sara Llopis Mestre

Gora Zaragoza Ninet

Universitat de València

This article analyses the only translation into Spanish of Rita Mae Brown's Rubyfruit Jungle (1973), translated in Spain by Jorge Binaghi in 1979. In order to do so, the study reviews lesbian narrative in English during the 20th century and the social and political factors that might have influenced its translation in Spain. An overview on Francoist literary censorship is followed by a discussion on how the Spanish literary market has received English lesbian novels and the case of Rubyfruit Jungle. Despite being one of the first lesbian novels published in democracy in Spain, the analysis suggests that the Francoist ideological paradigms are still perpetuated and have altered the translation.

palabras clave: Ireland, Maria Edgeworth, Translation, Cultural Studies, Literature by women, Descriptive Translation Studies.

Censura y traducción al español de la novela lésbica en inglés: el caso de Rubyfruit Jungle (1973)

El artículo analiza la única traducción al español de Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) de Rita Mae Brown, traducida en España por Jorge Binaghi en 1979. Para ello, el estudio hace un balance de la narrativa lésbica en inglés durante el siglo XX y de los factores sociales y políticos que podrían haber afectado su traducción en España. A continuación, se realiza un breve análisis de la censura literaria franquista y se comenta la recepción de la novela lésbica en el mercado literario español, especialmente en el caso de Rubyfruit Jungle. A pesar de ser una de las primeras novelas lésbicas publicadas en España ya en democracia, el análisis indica que los paradigmas ideológicos franquistas continúan perpetuándose y han alterado su traducción.

key words:

traducción, censura, novela, género, lesbianismo,

LGBT.

recibido en octubre de 2019 aceptado en septiembre de 2020

INTRODUCtioN

Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle was published by Daughters, Inc. in 1973 and translated into Spanish for the first time by the publishing house Martínez Roca in 1979, being one of the first explicit lesbian novels imported and published in Spain after fascist dictator Francisco Franco’s death in 1975. This novel is widely considered a landmark work for lesbian literature and, so, this essay aims to analyse its translation into Spanish in such particular context, reviewing the reception of English lesbian narrative in Spain and the factors that conditioned the reception and translation process.

Quebecois feminist translators pointed out that patriarchal canon has always prevailed and “defined aesthetic and literary value [privileging] work by male writers” (Von Flotow, 1991: 30) and, therefore, decided to start “reviving” forgotten works, stating that “a lineage of intellectual women who resisted the norms and values of the societies in which they lived [needed] to be unearthed and established” (1991: 31). Lesbian women, a historically discriminated minority that has struggled with a double oppression due to their gender and sexuality, have resisted with their identities the social “norms and values” feminist translators mentioned, making them more likely to be excluded from the literary canon. As a matter of fact, Lesbian Studies expressed the need to establish a lesbian literary tradition in order to “retrieve the pears of our lost culture” (Borghi, 2000: 154). The question to explore here is whether translation has successfully retrieved lesbian narrative for the Spanish-speaking community and how the “recovered” novels have been translated.

It is not easy, however, to establish a definition for lesbian literature. Marilyn Farwell (1995: 157) defines lesbian narrative as stories not necessarily written by lesbians or about lesbians, but stories which give room to lesbian subjectivity, the narrative space in which lesbian characters can be active and agents of wish. More precise definitions, like Julie L. Enszer’s (2010: 104), consider lesbian literature “literary creations that include lesbians as central characters”. This study has included works of fictional narrative in prose that portray in the foreground homosexual relationships between women —that can be, any type of romantic and/or sexual connection between women— or present an explicitly lesbian main character.

Lesbian novels in English developed during the 20th century after Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness was published in 1928, considered the first English novel with a lesbian theme. English and American lesbian narrative did not suffer censorship from a totalitarian regime as it will be seen in the case of Spain, but it did not escape the prevailing homophobia in the patriarchal framework of the 20th century. In fact, The Well of Loneliness (1928) was banned in Britain for decades due to the Obscene Publications Act (1857), a law that allowed state control to be exercised “at the point of circulation in order to protect audiences for whom the materials were most probably not intended or likely to reach, but who might be influenced by them” (Gilmore, 1994: 609). As a result, many of the works of fiction that addressed homosexuality during this century responded morally judgmentally to it and developed two repetitive patterns in the treatment of lesbian characters:

[T]he dying fall, a narrative of damnation, of the lesbian’s suffering as a lonely outcast attracted to a psychological lower caste; and the enabling escape, a narrative of the reversal of such descending trajectories, of the lesbian’s rebellion against social stigma and self-contempt. (Stimpson, 1981: 350)

Mary McCarthy’s The Group (1963) contributed to create a shift in the paradigm, showing lesbianism as an acceptable subject. Despite the lack of moral condemnation, lesbianism was portrayed fused with romantism, and the main character was completely free of stigma and self-contempt. Since the publication of this novel, a far less tormented lesbian character surfaced. Heterosexual writers mostly treated the lesbian character as a romp for erotic writing. Lesbian and sympathetic feminist writers, on the other hand, rejected the trope of lesbians’ damnation as more opened magazines and presses appeared. A remarkable case was Daughters, Inc., a publishing house that exclusively published books written by women and was considered “a medium that lesbian novelists could count on” (Stimpson, 1981: 374).. These new narratives were more hopeful and confident about homosexuality and claim the respectability of lesbianism. Among these novels was Patience and Sarah (1972), originally published as A Place for Us (1969), that emerged with the Stonewall riots, the beginning of the Gay Liberation movement. Almost immediately Daughters, Inc. published Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle (1973), the most successful of new lesbian novels that during the 1970s replaced The Well of Loneliness as “the one lesbian novel someone might have read” (1981, 375). These novels were a big influence in the contemporary English novel, as they introduced feminist ideology that abandoned patriarchal practices in their attitudes towards gender and sex.

After explicitly lesbian literature was established in the 1970s, the Lambda Literary Award, which included several lesbian categories, was founded in 1988 to help normalize and promote LGBT literature. During the 1980s and 1990s the lesbian novel became steadily more prolific and diversified into genres that not only included romance and realism, but fantasy, science fiction, mystery or young adult. These novels began then to be included for consideration in national awards and gained their spot amongst critical acclaim. That is the case of Bastard out of Carolina (1992) by Dorothy Allison, Fingersmith (2002) by Sarah Waters or Southland by Nina Revoyr (2003).

LESBIAN WOMEN IMN FRANCOISM

To analyse the reception in Spain of these works, it is paramount to take account of the social and political background that deeply affected Spanish culture and conditioned the production and translation of homosexual narrative. The 20th century in Spain was a very complex political period that directly affected gay and lesbian literature in the country. During this century, Spain experimented a period of monarchy with Alfonso XIII de Borbón (1886-1931)—which included the brief dictatorship of Primo de Rivera—, the democratically elected Second Republic (1931-36), the coup d’état that unleashed a civil war (1936-39) and plunged the country into the right-wing Catholic dictatorship of Francisco Franco for 40 years (1936-75), and the transition to parliamentary monarchy (1978-). The turbulent events involved times of repression and censorship in literary production that either featured homosexuality or was written by non-heterosexual authors. In the first decades of the 20th century preceding the Civil War, there was a period of a certain male homosexual splendour, but that is, strictly male. Women not only had to face the prevailing systematic homophobia, but also deal with settled and institutionalized sexism. Once Francoism was established and homosexuality was criminalized, gays and lesbians being considered “social dangers” by law, a strict mechanism of censorship of media, cinema and literature was installed, which buried any reference to everything that differed from the ruling heterosexual pattern.

The Francoist dictatorship established highly defined gender roles among which lesbianism, just like anything that strived from the catholic patriarchal frame, had no room1. Women had to adhere to their traditional roles as housewives that served their husbands, and as mothers, getting pregnant and raising their children in the faith and morals of the Catholic Church. Hence, compulsory heterosexuality was an intrinsic key aspect in Franco’s regime, damning deviance as dissidence. While in the post-war years the regime had not been as concerned with homosexuality, from the 1950s on, it developed “an inexplicable concern with codifying, pathologizing, and containing the activities of homosexual” (Pérez-Sánchez, 2012: 25). In 1954, the Law of Vagrants and Thugs was updated and modified to include homosexuals considering them “ill and handicapped”, so they were exposed to the application measures such as:

a) Confinement to a work camp or an agricultural colony. Homoxesuals [sic] who are subject to this security measure must be confined to special institutions and, at all costs, with absolute separation from the rest.

b) Prohibition from residing in certain designated places, and obligation to declare their domicile.

c) Submission to the surveillance of delegates. (qtd. in Pérez-Sánchez, 1981: 28)

In 1970, as Francoism was facing towards its final end in 1975, institutionalised homophobia took a final step forward when homosexuality was legally criminalized in the Law 16/1970, the Dangerousness and Social Rehabilitation Act (Ley de Peligrosidad y Rehabilitación Social), in a response to the fear of the disintegration of the Francoist system. Homosexuals feared police retaliation as Francoist laws were free to impose severe and arbitrary security measures such as:

a) Confinement in a re-education institution [for a period no less than four months and no longer than five years].

b) Prohibition from residing in a place or territory designated [by the court] and submission to the surveillance of the delegates [for a maximum of five years]. (qtd. in Pérez-Sánchez, 1981: 25)

In contrast to the law from 1954, the Law of Rehabilitation not only reinforced separation of homosexuals from society, but intended to ensure the creation of centres “staffed with the needed ideal personnel, [would] guarantee the social reform and rehabilitation of the dangerous subject through the most purified technique” (1981: 25).. Huelva’s Center for Homosexual was the main institution in charge of implementing “re-education measures”, that included “electroshock and the aversion therapy” (1981: 30). However, these centres were designed for male homosexuals and the Law did not state where convicted lesbians should be interned (Galván García, 2017: 67). The Rehabilitation Law only led to the official conviction of two lesbians2, and most of them were ignored and neglected by criminologists and, also, by gay liberation movements. The reason behind it was mainly based on the denial of the existence of lesbianism. In a highly conservative sexist society with such defined gender roles that only valued heterosexuality and relegated women to passive male-contenting roles, it was hard to conceptualise, even for homophobes, women’s independent sexuality. The author Carmen Alcalde portrayed very clearly the situation of lesbianism during the regime in a letter to U.S. feminist in the early 1970s:

[In Spain] there is no criminalization of lesbianism; it’s not contained in any article [of the Penal Code]. They don’t consider lesbianism, they think it’s nothing, that it’s a game, they don’t take it seriously. If they catch two women in lesbianism [sic], I assure you that nothing will happen to them, because the first thing they’ll think of is that a man was missing. They don’t have a sense of identity for lesbianism here. In truth, you can walk arm-in-arm on the street with a woman and, at a maximum, some ill-thinking man will insult you, but if he denounces you to the police, the police won’t know what to do. They don’t understand, they don’t understand that a woman would like another woman. There is no room for this in their ego, in their narcissism. (Gould Levine & Feiman Waldman, 1980: 36).

The regime was based on a catholic patriarchal system that relied on compulsory heterosexuality and the notion of the traditional family. For this reason, lesbian women are seen as a threat to a sexist system, much more than gay men: the lesbian is a woman who does not fulfil her only role socially assigned to her, that is, being a fertile womb (Huici, 2008: 178). Moreover, the lesbian does the unacceptable for a sexist catholic doctrine: rejecting submission to men and proposing an alternative model of family. The strategy most used to denature and eliminate lesbianism from the social horizon was invisibilization, forcing the “closet” on lesbians and denying their existence.

FRANCOIST CENSORSHIP ON LITERATURE

Censorship was one of the most remarkable tools during the times of the regime to establish and maintain this ideology. During Franco’s dictatorship, a specific censorship apparatus was established with the aim of filtering literature and eliminating any idea that might have been contrary to the regime. Censorship is understood here as the series of actions originating from the state and its formal institutions to impose suppressions or modifications of any kind on a text prior to its publication against the will or acquiescence of the author. Censorship is here a tool of the regime and a propaganda weapon to establish and maintain the Francoist ideology and dogma, and it was, thus, institutionalised and regulated by law.

There were two periods of regulated censorship during Franco’s dictatorship. The first one corresponds to the post-war censorship, from 1939 to 1945. During these years, the Falangist Juan Beneyto Pérez was appointed as head of the censorship in books, which helped to print in the criteria of literary censorship the fascist imprint, creating a bureaucratic apparatus in which priority was given to anyone close to the Falange movement (Pérez del Puerto, 2016: 36). Any text needed to go through the censorship service before being published. In order to complete the process of approval of a work, it was first necessary to request the examination of the censor, providing the identification of the author or publisher, as well as format, number of pages and sale price (2016: 49). This information gave the censor an idea of what type of audience could have access to the reading of the text he was evaluating depending on their level of education. After reading the work, the reader-censor had to answer the following questions following the triad God, Homeland and Family that so marked the Francoist ideology3:

- Does it attack dogma?

- Morality?

- The Church or Its members?

- The Regime and its institutions?

- People who collaborate or have collaborated with it?

- Do censurable passages qualify the total content of the work?

- Report and other observations

However, in 1941, a new turn was made in the process of centralization of the State and the creation of the Vice-Secretariat of Popular Education, in charge of the press and propaganda services. For many authors, this meant the end of the Falange’s domination, a process that culminated in 1945 after the decision to separate the Regime and its image from European fascism defeated in World War II. Falangist Catholics of a more moderate cut replaced the previous Falangist directors with the new orientation that was taking over the dictatorship. The necessity for the survival of the regime to put an end to the image of Spain as a fascist ally of the defeated Germany and Italy was accentuated in 1945, and Catholicism was imposed as the national defining character. As Pérez del Puerto reflects on his research, this fact turned the balance of power towards the Church and in detriment of La Falange and a second period of censorship much more controlled by Catholicism started. From 1945 onwards all the competencies of the Vice-Secretariat of Popular Education dominated by falangists were transferred to a new body called the Undersecretariat of Popular Education, which was now controlled by the Ministry of Popular Education, a ministry dominated by a Catholic majority.

In general, however, the censorship apparatus did not strive much from the modus operandi outlined during the stage of Falangist management, but some aspects were readjusted. Since 1939, the system of evaluation of the works had been staggered and systematized and by 1945 there was a process of revision in three levels organized in a pyramidal scheme, like many other Francoist organisms. The base of this pyramid were the reader-censors, who wrote a basic report and proposed a solution; at the second level were the dictaminadores, who received the report and met with the author or editor to present the changes; the third level belonged to the head of staff of the censorship policy (Abellán, 1980: 115-116). Among the main changes, there was a variation in the questions that guided the censor-reader’s report, which in 1945 turned to the following4:

- Does it attack dogma?

- The Church?

- Its Ministers?

- Morality?

- The Regime and its institutions?

- People who collaborate or have collaborated with the Regime?

According to several authors, this slight variation showed the primacy of the Catholic criteria over the politicians, since now four out of six questions revolved around religious matters. However, it is worth noting that institutional censorship was not the only type of censorship that affected the literary production in Spain. De Blas (1999: 287) defines as “self-censorship”, the foresighted measures that a writer adopts with the purpose of avoiding the eventual adverse reaction or repulse that his text may provoke in all or some of the groups or bodies of the state capable or empowered to impose suppressions or modifications with or without his consent. In such definition the subdivisions of self-censorship are also included, distinguishing between an explicit and an implicit self-censorship. Explicit censorship would reference to the censoring actions agreed by both author and repressive institution to “save” the text. Regarding implicit censorship, it is subdivided into conscious and unconscious. Conscious explicit self-censorship would be, then, the decisions taken by the author as the text is being written, taking into account the censorship apparatus the text will have to face when sent to publication. Lastly, unconscious censorship would make reference to acquired habits, historical and social conditioning factors that influence the writing and even the writer believes to discover, by introspection, time after having written his work, as influential in its genesis.

All this meant that, despite the efforts of translators and publishers, a large number of universal literature works did not reach Spain, since either their publication was banned, or they suffered internal censorship through the suppression of words, paragraphs and sections (Fernández López, 2000: 227). Today, many of these works have not yet been published or the censored versions of the texts continue to circulate, which may affect both the image of the author in the target culture, or even influence the conception that the target culture will have of the culture of origin (Zaragoza, 2018: 43). Deep research has been done on the impact of translation on the history of the literature in the different cultures. However, not as much has been studied about aspects like the censorship apparatus, the agents involved in the process (i.e., reader, censor, censorship board), from the publisher’s request for publication to the acceptance or rejection of the work. Zaragoza (2018: 53) points out that barely any research has been done on translation processes, on what is translated, how and for whom. In literature, generally, the name of the translator appears on the credits page of the work, as if it were an unimportant agent with little relevance in the product that reaches the target culture. In the same way, the censorship files that contain the justification for the rejection of a work, that is, the critical comments based on ideological fidelity to the Franco regime, should be objects of reflection. It is important to highlight the difficulty in tracing these files and also to discover which books in circulation are being censored versions.

Some works on the past decade have been conceived based on the concept of the translation and censorship, since censorship becomes a dangerous matter when it operates via translation, that is, from one language and one culture to another. If part of the meaning, function and form of a source text are lost in the passage from one language to another, if in addition that translated text is partially or totally censored (non-translated) or even corrected, the result will be a text that is different in many significant ways to the original. As Zaragoza, Martínez Sierra and Ávila establish (2015: 10), the consequences affect not only the image of the writer in the target language, but also the image, or idea, of the entire source literary system. In the same study, Zaragoza points out that, in addition, one of the problems faced when studying censorship is the great difficulty of tracing it. It is not easy to establish authoritatively when a text that has not been translated, and is therefore not available in a certain language, was translated at the time and immediately censored. The difficulty transcends even to cases where censorship is known, being the search, consultation, compilation and reproduction of censorship files mostly available in the Archive of Alcalá de Henares extremely complicated, since the request for materials is subject to severe restrictions that hinder the work of the researcher.

TRANSLATED LESBIAN LITERATURE IN SPAIN

Not much research has been carried out on how the English lesbian novel has been received by the Spanish literary scene. As studied, the Spanish literary market was not always open to lesbian fiction but has undoubtably improved in favour of representation of LGBT+ writing in the past 25 years. In the distribution of English lesbian writing, it is worth mentioning the important editorial work of Egalés and Odisea, gay and lesbian publishers who have been responsible for publishing and marketing a great number of translations. However, in the case of lesbian classic literature, only a few works have been recovered, such as Radclyffe Hall’s The Loneliness Well (La Tempestad, 2003).

Nonetheless, exclusively gay or lesbian publishers represent a small market share, not only because they are publishers with a significant but small catalogue, but also because in the sum of all LGBT themed titles published their share is small. In addition to them, without being aimed exclusively at LGTB, there are publishing houses that publish some basic titles (Turiel, 2008: 263), such as Laertes, La Tempestad, Icaria, Irreverentes, Anagrama or Vertigo, among others. The feminist publishing house Horas y Horas deserves here a special mention too, since they have published lesbian novels since 1991, even though under feminist pretentions, like the collection “La llave la tengo yo”, which they described as “los primeros libros abiertamente lesbianos en un país de sexualidad mojigata” (Cabré, 2011: 20).

To understand how the critic and the market deals with the lesbian novel in Spain it is worth studying the case of one of the biggest referents in the publication of lesbian narrative in the country, Mili Hernández, founder of Egalés and the renowned LGBT bookshop Berkana. She released a series of books called “Salir del armario”, a collection of contemporary narrative where the homosexual plot and voices are protagonists. She affirmed that she focused on publishing books that “are affirmative, often pedagogical texts that aim to normalize homosexuality for ‘unsophisticated’, ‘uncultured’ gay and lesbian readers” (Robbins, 2003: 111), which was criticized by writer Luis Antonio de Villena in an interview with Leopoldo Alas. They acknowledged her pedagogical role but criticized the fact that her only audience are “uncultured party boys” that do not buy books and never take into account, though, that “[many of those novels] are directed not at men at all, but at lesbians”, and Robbins proceeds pointing out that “[o]ne could productively critique the heteronormativity in ‘Salir del armario’, but Alas and Villena do not deign to analyze those texts at all. In a final note of condescension, Villena expresses his admiration for Hernández by admitting that she is ‘una chica lista’ [a clever girl], a form of praise that infantilizes this powerful woman” (2011: 112). This example serves as a representation for the situation of lesbianism among scholars and the LGBT community and it is for Robbins “a shadow of the deprecation of the feminine in the general intellectual community of Spain” (2011: 112). Robbins also explains how the Spanish intellectual elite “continues to be sexist, sexually conservative, anti-popular” and keeps on relegating gay women to a secondary role even within the gay community. This has contributed to the invisibilization of lesbian wome in the Spanish literary history, as it can be seen, for example, in Luis Antonio de Villena’s Amores iguales: Antología de la poesía gay y lésbica, that only includes three women out of a total of 126 poets.

When numbers are analysed, it can also be proved that lesbian writing is also less published and translated than male gay narrative. One of the most important bookshops in Spain on LGBT works for the past 25 years, besides Berkana, has been Librería Cómplices. The aim of this historical bookshop based in Barcelona is normalising, visibilizing and spreading LGBT culture. Their vast online catalogue is proof of the situation of lesbian literature previously noted in the country. The reader can find 287 works of national lesbian narrative, in contraposition to 639 works of national gay narrative. This study intended also to perceive if the inequality of this situation was compensated in the selection of translated materials. The results proved, however, that it was not the case. The catalogue presents 237 works of translated lesbian narrative, while the reader could find 428 examples of translated male gay narrative. Therefore, only 39% of the translated homosexual narratives published by this major house are lesbian novels.

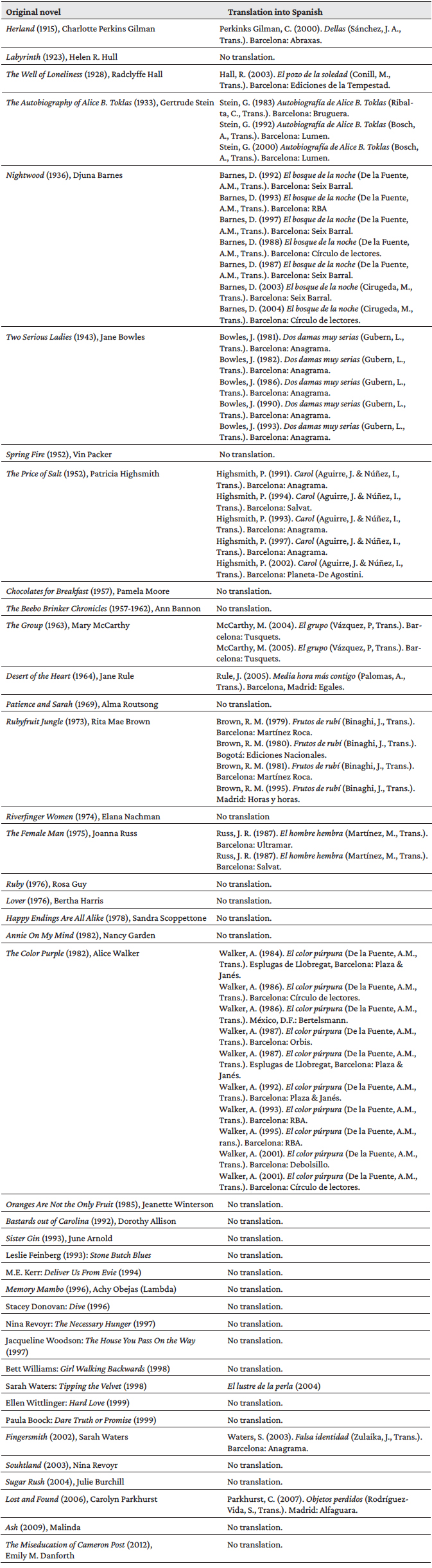

The next step of this research was, then, to study how and when contemporary English lesbian literature is being translated. In order to do so, a list was made containing most of the remarkable influential lesbian novels, many of them mentioned during the study, and all their documented translations. The research was carried out consulting Index Translationum, UNESCO’s database of book translation, and the Spanish Biblioteca Nacional (BNE). The data compiled5 allows the distinction of three groups of novels in terms of their translation.

There is a first group of novels published during the Francoist censorship that suffered through the filters of censorship and were translated and introduced to the Spanish culture for the first time decades later. That is the case of Herland (1915), only translated into Spanish in 2000, almost a century after its publication. In the same way, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933) was not translated until 1983, The Price of Salt (1952) was not translated until 1991, and The Group (1963) was only translated in 2004. It is also the case of Two Serious Ladies (1943), not translated for the first time until 1981. Regarding this novel, the Spanish Archivo General de la Administración was consulted during the study in order to find out whether it had been fully censored during those four decades. Archivo General confirmed there are classified censorship files about the novel, that have been requested for the study. The famous novel The Well of Loneliness (1928), which was not published in Spanish until 2003, is also part of this group. The novel was systematically thwarted by the Francoist censorship board, as Zaragoza (2018) documents. The recovered censorship files show how the first importation attempt was suspended in 1952 alleging:

An inverted who must live with successive lovers clears the way —though with deep renouncement— so the last of her lovers can seek regeneration in the normal love for a man. A novel with serious formal and content drawbacks. Those make it unpleasantly repulsive. These make it a work that needs further revision and opinion by other readers. Dangerous, therefore not acceptable. (Zaragoza, 2008: 52)

These files always show the established questions included in every censorship file. The only one that was answered with “yes” is “does it attack the Moral?”. On the same grounds, there were two more importation attempts in 1956 and 1957, but the novel remained fully censored. In the 1956 file, the censor verdict stated:

A novel about a woman inverted by the circumstances. The author presents the mother of this girl as the most repugnant being in maternity: she hates her daughter because she wasn’t born a male. While it details the main character’s tragedy before an ‘ungrateful’ world that rejects her, it also wants to justify inverted love. These novels about inverts only raise and aggravate the evil in today’s society. That is why we believe IT CANNOT BE IMPORTED. (Zaragoza, 2018: 41)6

The censors made use of homophobic slurs such as invertida in several occasions to indicate the main character’s sexuality and banned the translation of “these novels” (lesbian novels) based on moral grounds, considering them a “danger” to society.

A second group was also differentiated, formed by novels published originally when Spain was in democracy already, mostly during the 1990s and 2000s until the present. These novels would have been translated into Spanish without traces of censorship. It is the case of novels such as Tipping the Velvet (1998), Fingersmith (2002) and Lost and Found (2006).

The third group is the most numerous, since it is composed of novels that, despite their impact and recognition, have not been translated at all. These novels cannot be a restricted to a specific period of time, since they constitute 26 of the 40 novels listed, and its publication dates vary from dictatorship times to the present. In this group we find novels that have been not only popular, but remarkable works in lesbian literature, also acknowledged by the critic. For instance, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985) won Whitbread Award for a First Novel in 1985, was twice adapted to television and also audiobooks and is included on both GCSE and A Level educational curricula for England and Wales, Stone Butch Blues (1993) was a finalist for the 1994 Lambda Literary Award and won the Stonewall Book Award in the same year or Hard Love (1999) was one of the most critically acclaimed young adult novels in its time, winning more than 15 awards, including the Lambda Literary Award, Prink Award Honour Book and YALSA’s Best Book for Young Adults. Still, none of them have been translated into Spanish.

RUBYFRUIT JUNGLE (1973) IN SPAIN: TRANSLATING LESBIANISM

A novel that did not completely fit in any of these categories was Rubyfruit Jungle, since it was originally published in 1973 and translated only six years after in Spain, already in the recently established Transition period. The novel was written by Rita Mae Brown, a novelist, activist, poet and screenwriter born in 1944 in Hanover, Pennsylvania. She attended University of Florida (UF) with a scholarship, which was later revoked and in 1964 when she was expelled. She was said to have been reprimanded for her civil rights activism, but the author disclosed that the real reason behind it was her sexual orientation, as she openly stated to a Triple Delta sorority officer that “she did not care whether she fell in love with a man or a woman” (Barragan, 2006).. However, she received a scholarship for New York University (NYU). In 1967 she joined Columbia University’s Student Homophile League, from which she left after realizing that “gay men, like straight men, did not care about women’s issues” (Iovannone, 2018). She then became an early member of the National Organization for Women (NOW), from which she later also resigned due to Betty Friedan’s lesbophobic comments and the organization’s attempt to distance from lesbianism to protect the “respectability” of feminists. In 1968, she received a BA degree in English and the Classics and a degree in Cinematography from the New York School of Visual Arts. In 1973, she received her PhD from the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington DC. Having previously published feminist poetry, it was also in 1973 when she published her most renowned novel, Rubyfruit Jungle. Up to date, she has published three poetry books, more than twenty novels and wrote several screenplays for films and television. According to the Index Translatonium and Biblioteca Nacional, only Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) and Six of One (1999) have been translated into Spanish.

It is her novel Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) the work that was and still considered a landmark novel for lesbian literature, in part due to the fact that it was one of the first novels to explicitly portray lesbianism and a remarkable piece of literature that contributed to eradicate the lesbian stereotype at the time. It was an immediate success, a bestseller upon publication and arguably considered “the most popular lesbian work of fiction, surpassing even Radclyffe Hall’s 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness” (Iovannone, 2018). It was awarded the Lee Lynch Classic Book Award from the Golden Crown Literary Society in 2015, and the Pioneer Award at the 27th Lambda Literary Awards in 2016.

The novel is semi-autobiographical and tells the story of Molly Bolt, a good-looking American girl who was very aware of her attraction to women since she was a child. The book portrays her journey as a lesbian woman through primary school, high school and university and, in contrast to Stephen Gordon in The Well of Loneliness, she is “self-possessed, seductive, funny, and a clear heroine” (Iovannone, 2018). The novel also shows the strategies used by women to rebel against oppression and lays the foundation for feminism in the late 1960s. Molly’s story precedes the gay rights movement, second wave feminism and sexual revolution, but still shows how she fights against gender stereotypes and discovers her own self.

Interestingly, in an introduction the author wrote for the 2015 edition, Rita Mae Brown stated she is not keen to consider the book a “lesbian novel”, as she considers that any work labeled with a qualifier is relegated to second-class literary status. Anyhow, in this study, lesbian novels are not intended to be portrayed as second-class literature and labels are deemed necessary to make visible and highlight a situation of oppression, and, therefore, an important tool in order to achieve equality and normalization. Agreeing with Brown, the study considers that labels should not be necessary in an ideal cultural context where lesbian voices are heard, but here labels serve an instrumental purpose in order to identify these voices and be able to recover them. The tradition of invisibilization and censorship regarding lesbian narrative is exemplified in the translation of the novel into Spanish. As it was previously stated, it was the only big lesbian literary work translated in Spain in the 70s. It was a case of translation that stood out, due to the political context: it was translated in 1979, only five years after its publication, when Francoist laws on censorship were only fully derogated in 1978. The Spanish translation for Rubyfruit Jungle was first edited and published by the publishing house Martínez Roca in 1979, in Barcelona. It was titled Frutos de rubí. Crónica de mi vida lesbiana and the translation of the novel is signed by Jorge Binaghi. In 1981 it was re-published by the same house, and in 1995 the same translation by Jorge Binaghi was published by the feminist publishing house Horas y Horas.

In his translation, the only version of Rubyfruit Jungle the Spanish reader could have read in Spanish, there are traces of the situation of lesbianism at the time. It should be noted, once again, that it is a 1979 translation of a novel about a lesbian woman published in Spain right after Franco’s death, in the transition to democracy after a period of repression and censorship by the fascist and Catholic dictatorship. During 1977 and 1978, the mechanisms of censorship in the media, cinema and literature were put to an end. However, although it began in 1976, it was not until 1989 that the Law on Rehabilitation and Social Danger, which legally considered homosexuals criminals, was completely repealed. Bearing this context in mind, it is likely that in Jorge Binaghi’s translation there are features that reflect that lesbianism was far from being normalized and the Francoist paradigms were still present. In order to prove this thesis and draw conclusions, the three published translations (1979, 1981, 1995) were compared to prove that it was indeed the same translation and no fragments had been censored in translation. After confirming that was indeed the case, the first 1979 edition was carefully analysed and compared to the original text to study how lesbianism was being received and portrayed for the target culture in the target language. Two main relevant patterns have been found that are worth noting: the euphemistic translation of lesbophobic slurs and the perpetuation of the Francoist paradigm of imperative heteronormativity through the translation.

During the analysis, the translation of homophobic slurs stood out. Rubyfruit Jungle presents a deeply colloquial register that also introduces great variety of slang. To refer to a lesbian woman, the text mainly uses lesbian and queer but, while compiling a corpus, gay, dyke, femme, and butch were also found. In analysis the translation of queer, there is a difference in the way it was translation, depending on whether the term refers to a woman or to a man. It can be easily perceived in a conversation between Molly, the lesbian main character, and her cousin, Leroy, a gay man struggling with his sexuality. Only the term queer is used during the conversation to refer to both of them, individually. In the conversation Leroy says “You don’t do it and they say you’re queer” (Brown, 1973: 56), which is translated as “si no lo haces, dicen que eres raro” (Brown, 1979: 55). However, soon, Molly replies “You mean queer for real—sucking-cock queer?” (p. 57), which is translated as “¿Qué quiere decir eso de raro?... ¿Maricón?” (p.56). It a euphemistic translation, less vulgar and explicit than the original. Nonetheless, here, the slur maricón is first introduced and its equivalent derivation marica is used from this moment, established as the translation for queer for the rest of the conversation when referring to male homosexuals7. However, a slur is never established for the same term, queer, when it refers to a woman, and the euphemistic term rara [strange/weird] is maintained. It can be seen in the same conversation, as Leroy tells Molly “I think you’re queer” (p. 56), which is translated by Binaghi as “creo que eres una chica rara” (p. 55). The translation is maintained through the conversation8, and the only exception is observed in one of Molly’s cavillations: “Yeah, maybe I’m a queer. […] Me being a queer can’t hurt anyone, why should it be such a terrible thing?” (p. 62), translated as “Sí, tal vez soy homosexual […]. Que sea rara no puede hacer daño a nadie” (p. 60). This is the first case in which queer when referring to lesbians is translated with a term that explicitly acknowledges homosexuality. It is, however, still a neutral term that would be the literal equivalent to homosexual, but not to a slur.

It must be pointed out to understand these examples that queer is a term used to refer to sexual and gender minorities that had strong pejorative connotations. Activists in the late 1980s began a process to reclaim the word and, up to date, it is commonly used as an umbrella term to refer to themselves as members of the LGBT community, and was assimilated even in academic disciplines such as Queer Theory. However, this is not how it is used in the text. The novel was published in 1973 and the plot portrays the social picture of the United States in the 1960s, when Queer Studies and the reclaiming of the word had not been developed yet. As it was shown, throughout the same conversation, the translator chose four different ways to translate the same term into Spanish. When queer was referring to Leroy, a boy, it was translated at first as raro, later maricón and then it was established as marica. However, in the case of addressing Molly, queer is always translated as rara, expect for one time in which the translation is homosexual. Rara would be the equivalent to weird or strange, but certainly does not have the same pejorative connotation and insulting strength as queer:

[t]he term ‘queer’ has operated as one linguistic practice whose purpose has been the shaming of the subject it names or, rather, the producing of a subject through that shaming interpellation. ‘Queer’ derives its force precisely through the repeated invocation by which it has become linked to accusation, pathologization, insult. (Butler, 1993: 18)

The translation does not deny the target text from such a strong slur in the case of male homosexuals, but it does when referring to lesbians. The reason is strictly linked to the situation of lesbianism in Spanish culture, influenced by the Francoist repression. This conversation shows how it was common to have homophobic insults for men, but lesbians were invisible. Whether intentional or not, maintaining the translation of the slur as rara right after translating the same form towards men as marica serves as a telling cue of the consideration and reception of lesbianism in Spain.

In order to get to a more factual conclusion, the translation of the rest of the allusions to female homosexuality that strived from lesbian were analysed, specially the case of the translation of the term queer. Firstly, a tendency to keep avoiding the use of the slur in Spanish was noted, using different techniques. One of the first translation techniques observed was the use of deixis and ellipsis. In a conversation between Molly and her two high school best friends, Connie and Carolyn, Rita Mae Brown writes: “We are not queer. How can you say that? I’m very feminine, how can you call me a queer?” (p. 93), which was translated as “No somos eso. ¿Cómo puede decir semejante grosería? Soy muy femenina; no tienes derecho a llamarme de ese modo” (p. 87). Here, the deictic eso was used as a euphemism, and so was de ese modo, in order to avoid an explicit term. The tendency continues in cases where the original does not even present a slur. Molly and her roommate Faye are asked “Had either of you been gay before college?” (p. 105), which is translated as “¿Y anteriormente ya habíais tenido la experiencia?” (p. 98), using the definite article to purposely elide the reference to homosexuality.

The most common tendency in the novel regarding the translation of queer when referring to women is translating it as rara, as it was already seen in the analysis of the conversation between Leroy and Molly. Binaghi translates “Yeah, everybody would call you queer, which you are, I suppose” (p. 93) as “Sí: todo el mundo os llamaría ‘raras’, que es lo que supongo que sois” (p. 87), introducing the use of quotes in rara, which is maintained in most of the novel in Spanish to indicate the special euphemistic use of the word. Instead of opting for an equivalent slur, Jorge Binaghi continues translating “that doesn’t make me queer” (p. 93) as “eso no hace de mí una ‘rara’” (p. 87) and “Do you think you’re queer? […] Oh, great you too. So now I wear this label “Queer” emblazoned across my chest” (p. 94) as “¿Crees que eres “rara”? […] Oh no, ¡tú también! Mira, de ahora en adulante usaré una banda con la palabra ‘rara’ que me ciña todo el pecho” (p. 88). The only other case in which queer referring to women is translated with an explicit term directly linked to homosexuality, besides the aforementioned isolated case in which is translated as homosexual, is when it is translated as lesbiana. The examples can be found only in a conversation between Molly and her mother. The latter says “A queer, I raised a queer, that’s what I know. […] Even being a stinky queer don’t shake you none” (p. 119), which is translated as “Una lesbiana, he criado una lesbiana, eso es lo que sé. […] Ni siquiera te avergüenza ser una asquerosa lesbiana” (p. 109).

The translation of specific lesbophobic slurs also stood out in the analysis. In the case of the term dyke, it is also translated inconsistently but with a tendency to use euphemisms or more neutral words. Examples were found, such “So an old dyke tries to buy my ass?” (p. 147), which was translated as “¿Así que una vieja lesbiana quiere comprarme?” (p. 132), showing that in some cases the slur is also translated as lesbiana. In another fragment we found that “[W]hy don’t you come right out and call me a dyke too if that’s how your mind is misfunctioning?” (p. 93) was translated as “¿Por qué no dices que soy un macho si tienes la mente así de pervertida?” (p. 87), showing a different translation this time. Macho might be a closer term for dyke in terms of connotation, since it appeals pejoratively to the stereotypical masculinity in a woman that is socially linked to her homosexuality. A third translation for the term was also found: “Only a lesbian would stoop to such a thing. Did you know that James? Your girlfriend is a dyke” (p. 165), which was translated as “Sólo una lesbiana se rebejaría a una cosa semejante. ¿No lo sabías, James? Tu amiga es una tortillera” (p. 146). Tortillera is one of the two specific lesbophobic slur found in the corpus. It must be taken to account, however, that Molly was called a lesbian right before being called also a dyke, which limits the choices of the translator when it comes to using once again lesbiana, since it had been used in the same sentence as the translation for lesbian.

Along the same lines, there are some specific terms that are not slurs, but are related to lesbianism. There is one particularly interesting conversation in which Molly is in a lesbian bar and she gets asked “Speaking of tits, sugar, are you butch or femme? […] A lot of these chicks divide up into butch and femme, male-female” (p. 130). This fragment was translated as “Y hablando de tetas, dulzura, ¿eres macho o hembra? […] Algunas de estas mujeres son “machos” y otras, hembra” (p. 118). Here, butch and femme are translated as macho and hembra, the equivalent to male and female, alluding to the traditional gender roles of masculinity and femininity that these women follow. In fact, male-female is not translated since it would be redundant. It must be taken into account that the options for the translator were limited: Spanish did not have a proper equivalent for these terms, since lesbian subculture had not been yet developed due to the political repression. Nowadays, actually, there is not a common term in Spanish to reference the dichotomy butch/femme yet, and in lesbian circles these terms are sometimes used in English as loanwords. It is true that butch could be translated as marimacho, but there is not a term in Spanish that can cover femme9. This slur is in fact used later, when Molly is told “I though you knew or I wouldn’t have sprung it on you” (p. 130), which is translated “Creía que sabías estas cosas; de otro modo no habría permitido que te atosigara ese marimacho” (p.118). This is the second specific lesbophobic slur found in the novel, despite the term not being present in the original intervention. Moreover, the next sentence in the dialogue is followed by what could be considered a mistranslation, since the original says: “Some people don’t, but this bar is into heavy roles and it’s the only bar I know for women” (p. 130), being translated as “Las que vienen a este a este bar están especializadas en hacer el papel activo. Es el único bar para mujeres que conozco” (p. 118). The original never stated that the women coming to the bar were “specialized in taking the active role”. The reasons behind this (mis)translation might imply a lack of understanding of what “being into heavy roles” means (the roles being here butch and femme, not necessarily meaning that any of them take the “active role”), perhaps due to the fact that the translator is a man not familiarised with lesbian culture. This is also proved along the novel in cases such “You’re a goddamn fucking closet fairy, that’s what you are” (p. 112), which was translated as “¿Sabe lo que pienso? Que usted es tan lesbiana como yo. Usted es una aborrecible hada, pero de letrina, no de cuento” (p. 104). Here the term closet fairy is introduced, which is used to refer to a homosexual person who is still closeted and prefers not to reveal that they have a sexual preference for people of the same gender. In the Spanish version, however, the term is mistranslated into “an abominable fairy, but from a latrine, not a fairy tale” which does not allude to her closeted homosexuality at all. Here it must be noted once again that there is not an equivalent term in the Spanish language, however. The lack of lexicon in Spanish proves how the homosexual scene, and specially lesbianism, had been repressed and has still not been socially developed in Spain as in other western countries. During the novel, the constant use of lesbiana seems to be a consequence of the invisibilization of lesbianism and therefore the lack of common terms to refer to them, but the reason behind might lie also on the fact that lesbiana was considered insulting and shaming enough. In fact, Molly’s mother, after calling her a queer, tells her daughter “I know you let your ass run away with your head, that’s what I know” (p. 119), which was translated into “Sé que has perdido la cabeza y, junto con ella, la vergüenza, eso es lo que sé” (p. 109). Here, the translator adds the concept of shame that is not present in the original text. This fragment might support the hypothesis that the Spanish society had insults to shame gay men that were commonly used, but lesbophobic insults were not as common, since the Spanish society barely needed shaming a group that did not exist in their eyes. That is to say, gay men could be persecuted because they were visible and acknowledged, but lesbians were not even recognised as a reality and were ignored in official and social discourse (Rodríguez, 2003: 88).

On the other hand, even more revealing might be the second trend noticed in the analysis of the translation, that shows the perpetuation of the Francoist paradigm of heteronormativity. The translator shows a tendency to translate the marks of heterosexuality in the text with terms that allude to normality. In the novel, Molly tells Faye, her roommate who wants to sleep with her, “my experiences with non-lesbians who want to sleep with me have been gross” and Faye replies “how can you be a non-lesbian and sleep with another woman?” (p. 107). This was translated as “Mis experiencias con mujeres normales que quieren acostarse conmigo han sido tremendas” and “¿Cómo es posible ser normal y acostarse con otra mujer?” (p. 100). By turning non-lesbian (what could have been easily translated as no-lesbianas or heterosexuales) into mujer norma,l the translator is changing the message and adds a homophobic connotation not present in the original, in this way perpetuating the Francoist morality and social codes that only consider heterosexuality normal.

The tendency is extended through the novel, also when translating the term straight. The phase “but everybody does it, straight or gay” (p. 106) is translated as “pero todo el mundo lo hace, normales o no” (p. 99). This could have been translated with many equivalent terms, such as “hetero o gay”; however, once again, the translation is associating heterosexuality to normality and making homosexuality the opposite. This translation is even mantained when a gay person that has come to terms with their sexuality is speaking: Molly’s cry “Christ, I’ll never understand straight people!” (p. 171) is now in the Spanish version “¡Cristo, nunca entenderé a los seres normales!” (p. 151); “I was afraid you’d be some straight chick up here for an abortion” (p. 124) was translated as “Temía que fueras una de esas chicas corrientes que vienen aquí para abortar, o algo así” (p. 114); and “I cried and allowed as how I’d change and go straight and all that shit. […] You fuck a little with a member of the opposite sex and you got your straight credentials in order” (p. 131) turned into “yo lloraba y prometía cambiar y convertirme en una persona normal. [...] Basta con que te acuestes algunas veces con un miembro del sexo opuesto para obtener tus credenciales de normalidad” (p. 119). Compulsory heterosexuality is in this way subtly perpetuated throughout the novel. Even though translating an important lesbian novel constitutes a step forward in the visibilization of lesbian women in the target culture, the reception of it keeps depicting lesbianism as something “unnatural” and, as Adrienne Rich stated in Compulsory Heterosexuality, “any cultural/political creation that treats lesbian existence as a marginal or less ‘natural’ phenomenon […] is profoundly weakened thereby” (1980: 632). It must be highlighted that this is the translation featured in every edition published in Spain, including in the feminist publishing house Horas y Horas. That means, therefore, that this is the only conception the Spanish-speaking community might have of a landmark work of lesbian literature.

CONCLUSION

It is clear, therefore, that a series of social and political circumstances influenced the situation and consideration of lesbianism in Spain. Francoism was the most influential one, as it fostered the stigmatization of lesbians and thwarted the development of the lesbian novel in the country. The stigmatization process in the case of lesbians was particularly different to the case of male homosexuals, since the process was here based on invisibilization. The translation into Spanish of Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) serves as an example of how there was a lack of lexicon and understanding of lesbianism.

The political and social context has also affected the translation of the Lesbian Novel in other ways. First of all, it has delayed the translation of important lesbian classics for decades, since their importation was banned by the Francoist censorship apparatus. That is the case of important works of literature such as Two Serious Ladies (1943) or The Well of Loneliness (1928). A need to study censorship and recover censorship files that have thwarted translations has also been proved paramount during the analysis, since scholars have been paying little attention to the matter. In second place, it has been shown that there is a great number of lesbian novels that have not been translated into Spanish at all. That was the case of 26 out of 40 popular, awarded lesbian novels analysed, including Hull’s Labyrinth (1923), Harris’ Lover (1976) or Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985). In the same line, the study also indicates that even within LGBT literature today, the lesbian novel is at a disadvantage compared to the number of male gay novel translations. In the third place, lesbian novels have been distributed presenting censorship and these editions are still distributed up to date, which can affect the image of the author in the target culture, or even influence the conception that the target culture will have on the source culture. The analysis of the translation of Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) has pointed out how, even in democracy, the Francoist homophobic model was perpetuated in translation, and this remains the only version distributed in the country of such a landmark work.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abellán, Manuel L. (1980): Censura y creación literaria en España: 1939-1976, Barcelona: Península.

Barragán, Carolina (2006): «Rita Mae Brown», Pennsylvania Center For the Book, (2006), in <https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/bios/Brown__Rita_Mae> [accessed 14 March 2019].

Borghi, Liana (2000): «Lesbian Literary Studies», in Theo Sandfort et al. (eds.), Lesbian and Gay Studies: An Introductory, Interdisciplinary Approach, London: SAGE, 154-160.

Brown, Rita M. (1979): Frutos de rubí. Crónica de mi vida lesbiana, trans. Jorge Binaghi, Barcelona: Ediciones Martínez Roca.

Brown, Rita M. (2015): Rubyfruit Jungle, London: Vintage Classics.

Butler, Judith (1993): «Critically queer», GLQ: A journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 1/1, 17-32.

Cabré, Maria Angels (2011): «Plomes de paper: Representació de les lesbianes en la nostra literatura recent» in Accions i reinvencions. Cultures lèsbiques a la Catalunya del tombant del segle xx-xxi.

De Blan, J. Andrés (1999): «El libro y la censura durante el franquismo: un estado de la cuestión y otras consideraciones», Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie V, Historia Contemporánea, 12, 281-301.

Enszer, Julie R. (2010): «Open the Book, Crack the Spine: 69 Meditations on Lesbians in Popular Literature» in Jim Elledge (ed.), Queers in American Popular, California: ABC-CLIO.

Farwell, Marilyn R. (1995): «The lesbian narrative: The pursuit of the inedible by the unspeakable» in Professions of desire: Lesbian and gay studies in literature, New York: The Modern Language Association of America.

Fernández López, Maria (2000): «Comportamientos censores en literatura infantil y juvenil: Traducciones del inglés en la España franquista» in Rabadán (ed.), Traducción y censura inglés-español: 1939-1985, León, Spain: Universidad de León, 227–254.

Galván García, Valentín (2017): «De vagos y maleantes a peligrosos sociales: cuando la homosexualidad dejó de ser un delito en España (1970-1979)», Daimon Revista Internacional de Filosofía, 67-82.

Gilmore, Leigh (1994): «Obscenity, Modernity, Identity: Legalizing The Well of Loneliness and Nightwood», Journal of the History of Sexuality, 4/4, 603-624.

Gould Levine, Linda and Feiman Waldman, Gloria (1980): Feminismo ante el franquismo: entrevistas con feministas de España, Miami: Ediciones Universal.

Huici, Adrián (2018): «La construcción de la lesbiana perversa. Visibilidad y representación de las lesbianas en los medios de comunicación. El caso Dolores Vázquez–Wannikhof [Review]», Revista Internacional de Comunicación Audiovisual, Publicidad y Literatura, 1/6, 176-180.

Iovannone, Jeffry J. (4 June 2018): «Rita Mae Brown: Lavender Menace», Medium, in https://medium.com/queer-history-for-the-people/rita-mae-brown-lavender-menace-759dd376b6bc.

Pérez del Puerto, Ángela (2016): La censura católica literaria durante la Posguerra española: Traspasando las fronteras de la ideología franquista, (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Tennessee) in https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5156&context=utk_graddiss [accessed 14 May 2019]

Pérez-Sánchez, Gema (2012): Queer Transitions in Contemporary Spanish Culture: From Franco to La Movida, Albany: SUNY Press.

Rich, Adrienne (1980): «Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence», Signs: Journal of women in culture and society, 5/4, 631-660.

Robbins, Jill (2003): «The (in) visible lesbian: The contradictory representations of female homoeroticism in contemporary Spain», Journal of lesbian studies, 7/3, 107-131.

Rodríguez, María Pilar (2003): «Crítica lesbiana: lecturas de la narrativa española contemporánea» in Establier (ed.), Feminismo y multidisciplinariedad, Alicante: Universidad de Alicante, 87-102.

Stimpson, Catherine R. (1981): «Zero degree deviancy: The lesbian novel in English», Critical Inquiry, 8/2, 363-379.

Turiel, Josep M. (2008): «La edición y el acceso a la literatura y los materiales GLTBQ», Scriptura, 19, 257-280.

Von Flotow, Luise (1991): «Feminist translation: contexts, practices and theories», TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction, 4/2, 69-84.

Zaragoza Ninet, Gora (2008): «Censuradas, criticadas... olvidadas: las novelistas inglesas del siglo XX y su traducción al castellano» (unpublished doctoral thesis, Universitat de València).

Zaragoza Ninet, Gora (2018): «Gender, Translation, and Censorship: The Well of Loneliness (1928) in Spain as an Example of Translation in Cultural Evolution» in Seel (ed.), Redefining Translation and Interpretation in Cultural Evolution, Pennsylvania, USA: IGI Global, 42-66.

Zaragoza Ninet, Gora, Martínez Sierra, J. José and Ávila-Cabrera, J. Javier, (2015): «Introducción», Quaderns de Filologia: Estudis Literaris, 20, 9-13.

Appendix

Landmark lesbian novels and their translation into Spanish

1 Manuel Ortiz Heras, ‘Mujer y dictadura franquista’, Aposta. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 28 (2006), pp. 1-26; Gema Pérez-Sánchez, Queer Transitions in Contemporary Spanish Culture: From Franco to La Movida, (SUNY Press, 2012).

2 See Appendix 1.

3 My translation.

4 My translation.

5 See Appendix.

6 My translation

7 “He don’t look like no queer to me. Not with all those muscles and that deep voice. […] Maybe I’m a queer. […] You’re the only one in the world I can tell cause I think you’re queer too. […] I may be queer but I ain’t kidding no men. […] The guys at school roll queers all the time. […] Do you think I’m a queer?” (p. 58) was translated as “No me parece marica con estos músculos y esa voz profunda. […] Tal vez soy marica. […] Eres la única en el mundo a quien se lo puedo decir porque pienso que tú a lo mejor eres también así. […] Luego me dijo que me quería y trató de besarme. Puedo ser marica, pero no voy a besar a ningún hombre. […] Tengo miedo … Los muchachos de la escuela te llaman marica a gritos por cualquier cosa. […] ¿Piensas que soy marica?” (p. 58)

8 “First you tell me I’m a queer, and now you are so worried everybody’s gonna think you’re one” (p. 57) was translated as “primero dices que soy rara, y luego te preocupas porque todos van a pensar que tú lo eres”. Also, “See, I told you you were queer” as “Ves, ya decía yo que eras rara” (p. 57).

9 A lesbian whose appearance and behaviour are seen as traditionally feminine.