Interpretation in health services during the pilgrimage season: a case study

Abdallah Jamal Albeetar

University of Granada

This article will show the results of the research conducted in Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia in 2015, related to interpretation services in hospitals during the pilgrimage (Hajj), which target the non-Arabic speakers pilgrims that visit the kingdom each year. For this, we will talk about the scientific methodology used and its various stages, then we will show the most important results obtained by the analysis of the information. Finally we will give our suggestions to improve interpretation services in hospitals during Hajj.

key words: interpretation services, hospitals, pilgrimage, analysis, suggestions.

La interpretación en los servicios de salud durante la temporada de peregrinación: un estudio de caso

En este artículo presentamos los resultados del estudio realizado en La Meca y Medina en Arabia Saudí en 2015, sobre los servicios de interpretación prestados en los hospitales durante la Peregrinación Mayor destinados a los peregrinos no arabófonos que visitan el país cada año. Con este propósito, describiremos el enfoque metodológico adoptado y sus fases. Acto seguido, desplegaremos los resultados más importantes del análisis de datos, y finalmente, propondremos algunas sugerencias para mejorar los mencionados servicios en La Peregrinación Mayor.

palabras clave: servicios de interpretación, hospitales, peregrinación, análisis, sugerencias.

Introduction

Interpretation in public services specifically in health represents a profession that has gained paramount importance around the world in recent years for several reasons. These include: the increasing growth of immigrants, the flow of foreign students in addition to pilgrims. Undoubtedly this situation is characterized by the existence of multiple cultures and language groups that need translation whether written or oral in order to communicate with each other, which will inevitably lead encountering solutions to the difficulties that lie in understanding what the two parties want to express (Taibi, 2011). The studies of this profession have attracted the attention of many researchers, including: Cambridge, 1999, 2002, 2003; Gentile et al. 1996; Gentile, 1997; Hale, 2007a, 2007b, 2010; Martin, 2000, 2003, 2006; Abril, 2006; Mikkelson, 1996, 2002; Tomassini, 2002; Valero-Garcés and Mancho, 2002; Valero-Garcés, 2003, 2005, 2008a, 2008b, 2011, 2014, 2017; Foulquié-Rubio et al., 2018.

On the other hand, with regards to the research project that we conducted in this evaluation, we noticed that there is no scientific study in the Arab world concerning interpretation in public services, particularly for health. According to a prior investigation, we found that only a few Arab authors are interested in this profession from a point of view related to translation sciences, which means how these kinds of translations are done. Among those researchers are Dr, Mustapha Taibi, a researcher of Moroccan descent, who published on interpretation in public services in the Arab world in 2011 and 2016. In 2011, his research focused on providing a study that included three cases:

- Amazigh minority in the Kingdom of Morocco.

- Foreign workers in the United Arab Emirates.

- Non-Arabic speaking pilgrims to Saudi Arabia, without highlighting the health field.

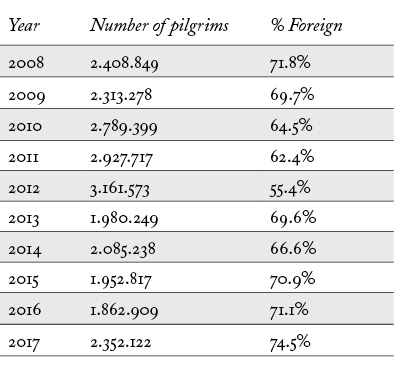

From this standpoint, and depending on the above, we have decided to provide a study on interpretation services in the field of health during the period of pilgrimage. We aim to highlight the importance of interpretation services in hospitals, following the same path initiated by the researcher Taibi. Furthermore, we will provide a description for the interpretation in public services in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia during the pilgrimage season (Hajj), as the kingdom receives millions of pilgrims yearly coming from all over the world. According to the statistics regarding pilgrims compiled up to 2017, 2012 was the year which received the largest number of pilgrims in the past decade (3.161.573). In 2015, due to projects of expansion of both mosques the Saudi government decided to reduce the number of visitors. The following table clarifies the evolution of the number of pilgrims who visited Saudi Arabia in the past ten years (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2017).

Motivation

The idea of accomplishing this research is attributed to unexpected participation in interpretation which I personally experienced in the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina during my visit to the kingdom to perform the Umrah (The minor Hajj) in 2010. While I was walking in the courtyard of the mosque, I found a French pilgrim asking for help in his language to find an all-night pharmacy to measure his blood pressure. Fortunately I was passing by and I was able to help him and accompanied him to the nearest pharmacy. There, I explained to the pharmacist what happened with the pilgrim and he thus provided the necessary assistance. After this incident, the following questions came to my mind:

- How does the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia face such situations?

- How the interpretation services are organized in hospitals during the pilgrimage season?

- Are there guidelines for this profession?

After an initial investigation, we checked that the work we are about to do had never been done by any other researcher before. For this reason, we can justify our choice to do this study with the following:

- After extensive review, we found that research of interpretation in health services in the Arab world in general, and Saudi Arabia in particular, are rare. For this reason we decided to pave the way for this kind of investigation in such countries.

- The obligation to facilitate the Hajj by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As mentioned before, the kingdom receives millions of pilgrims every year coming from all over the world, which leads to an urgent need for interpretation in public services in general and health in particular.

Methodology

In order to conduct this research, we adopted the case study methodology, which is scientific, experimental, and qualitative. It is aimed at studying phenomena characterized by their significance in society while expecting to provide, verify or refuse certain events. To this end, it uses many different tools to gather information, such as interviews, questionnaires, and observation, etc. (Coller, 2000: 29). This scientific methodology contains three stages in order to be applied properly. They are: designing the study, field work, and case analysis.

Constructing the research

The first stage is to construct the research. It allowed us to prepare a separate document which includes an outline of the theories that we used in the second stage; the application of the research to the field. This separate document includes the reason for choosing this study and justifies our decision for choosing this case instead of others. Likewise, it has some ideas and theories that we want to clarify, reject or ascertain, and the type of tools and information that we needed to collect in order to build a case and extract results using questionnaires, documents, statistics, interviews, etc. Moreover, we outline the approximate dates for the start and end of the study. The research duties (preparing the separate document to construct the research, preparing invitations to participate in the research, visiting the places of the research and preparing the results), as well as a list of references that we have used to prepare the case study, are also included. Finally, we propose other cases similar to the one we studied to be addressed in the future.

Field work

This stage has enabled us to collect the important and necessary information to get the results required to accomplish this study. To this end, we personally visited the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina during the pilgrimage season of 2015.

1. Collecting information

In order to collect the necessary information for the completion of this study, we adopted open-ended questions which we used during 90 interviews, at various hospitals in the two holy cities. We used a Panasonic recording machine to record interviews in order to facilitate the analysis process. The establishments that participated in this study in the two holy cities were:

a) Mecca:

- King Abdullah Medical City (KAMC)

- Maternity and Children Hospital (MCH 1)

- King Abdulaziz Hospital (KAH)

- Al-Noor Specialist Hospital (ASH)

- The Cooperative Office for Call and Guidance (COCG)

- Turkish Pilgrims association (TPA)

b) Medina:

- Al-Ansar Hospital (AAH)

- King Fahd Hospital (KFH)

- Ohud Hospital (OH)

- Maternity and Children Hospital (MCH 2)

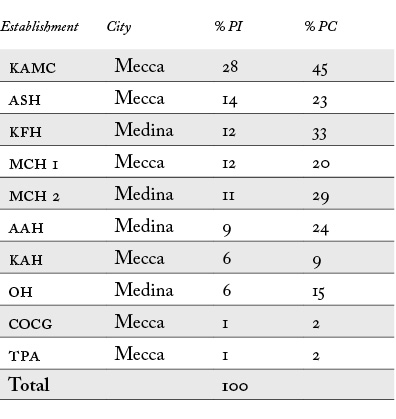

The following table shows the hospitals visited, with the participation percentages of the interviewers in both cities. The percentages refer to the total of the sample participation based on the city and the site visited:

pi: Participans in the investigation. pc: Participans in the city

2. The Research Sample

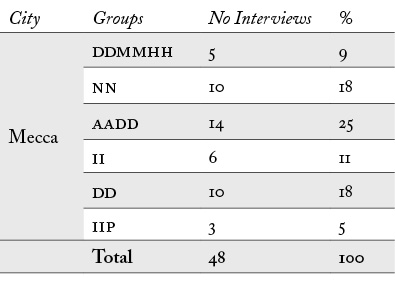

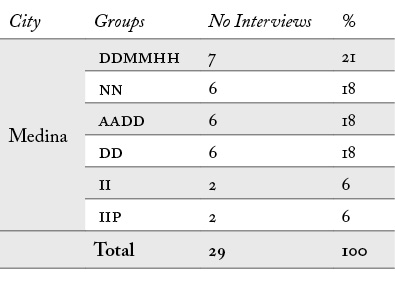

The research sample included six categories divided amongst the aforementioned hospitals:

- Administrators (AADD)

- Department Managers in hospitals (DDMMHH)

- Doctors (DD)

- Nurses (NN)

- Volunteer Interpreters (II)

- Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage (IIP)

Concerning the demographic makeup of the sample: 65% were between 30 and 40 years of age and 35% between 41 and 60; 75% male, and 25% female. 86% were from Arab countries with Arabic as their Mother-tongue the rest were from India, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh; 89% of these spoke English as a second language, because it was the language of their studies. None of them had a diploma in translation or interpretation. Doctors made up the highest percentage of people in the study at 33%, administrators at 32%, nurses 24%, and volunteer interpreters 10%. Moreover, 99% received pilgrims daily who do not speak Arabic and thus have communication problems. The following tables show the number of interviews conducted with each category in hospitals in the two holy cities:

Information Analysis

In order to analyze the information and obtain the required results, we transcribed the recorded interviews taking into consideration everything said by the people we interviewed. Sometimes we found some redundancy or evasion in answers. This is due to two reasons: either because they do not know the answer, or did not want to accept responsibility.

After completing the process of transcribing the interviews, we dispensed with those that provided us with useless information for this study, then we compiled and linguistically scrutinized the interviews according to the aforementioned categories. After that, we set the symbols which enabled us to extract the information necessary for the success of this study. Finally, we used the qualitative research software (Inspiration 7.6) which helped us to extract the number of similar answers to each question. We will not display all the answers because the situation does not permit this, but leave that for future publications.

Results

This stage is considered the corner stone of the study, which enables us to display the results that we extracted by pre-analyzing the interviews. We will directly display some answers of the people we interviewed in hospitals.

Mecca

A ) Administrators: 93% of administrators stated that interpretation services are available in hospitals by Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage (Al-Tawafa institutions), also by staff doctors and nurses who speak several languages. As for the difficulties they face when receiving non-Arabic speaking pilgrims, there are several including:

- Not knowing the pilgrims’ identity nor the language.

- Inability to know what the pilgrim is suffering from.

- The delay of translators in reaching the hospitals to help in translation which negatively affects the diagnosis of the case, and thus having to conduct full checkups to solve the problem.

- The limited number of translators available in hajj guidance institutions (Al-Tawafa).

- Lack of people who know respective sign languages.

- The absence of translators which in its turn leads to a lack of knowledge of the medical history of the patient.

- Focusing on interpretation of the major languages during pilgrimage while neglecting the minor ones.

- Facing problems while requesting translators from the hajj guidance institutions (Al-Tawafa).

B ) Department Managers in Hospitals: 20% of the interviewees stated that interpretation service is not officially available in hospitals, but is provided outside the hospital by the Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage. As for the difficulties, we should mention that department managers are also doctors and they face the following problems:

- Inability to communicate with the patients before and during diagnosis.

- Inability to get the patient’s permission to perform any surgical or treatment intervention.

- The process of getting information is set back due to the delay of the translator.

C ) Doctors: 60% of doctors stated that interpretation services are not officially available in hospitals but performed by the hospital staff members, while another 20% said that sometimes Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage are responsible for that. While the last 20% declared that interpretation services are not available during the pilgrimage season. As for the difficulties, they are as follows:

- Inability to communicate with patients to obtain the necessary information for diagnosis.

- Failure to find translators when the patients suddenly arrives without a translator.

- Patients do not provide the doctor with any medical report that clarifies the patient’s medical history which forces the doctor to do full checkups to know what the patient is suffering from.

- The wasting of time to collect information about the patient’s condition due to lack of translators.

- The translators delay or non-arrival, which leads to searching for people who speak several languages within the hospital, but sometimes there is no one to help available.

- The problem of minority languages for pilgrims, such as Chinese.

- Translators’ delay.

D ) Nurses: regarding this category, 70% of the people we interviewed stated that interpretation services are officially available at hospitals, through Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage. In cases when the translator from these institutions is not available, they ask the doctors, nurses, and sometimes the sanitation workers for help in interpretation. As for the difficulties, they are:

- Inability to communicate with the patient.

- The delay in translators reaching the hospital.

- Inability to communicate with the interpreters to obtain the necessary information to diagnose the condition and know the patient’s medical history.

E ) People on charge of translation and volunteers: regarding this category, we prefer to shed light on the qualifications of the interpreters, since all of the people we interviewed stated that they have certificates in fields different from the services they provide (100%).

F ) Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage: with regard to this category, we found it appropriate to highlight the lack of standards they (Al-Tawafa) adopt in the search for translators, as all of the people we interviewed (100%) stated that IIP do not have any specific standards to search for translators other than speaking a particular language.

Medina

Regarding Medina, we noticed the same difficulties that we listed above, for this reason we will not repeat them again. Also, the majority of the people we interviewed in Medina stated that interpretation service is available by Al-Adella Institutions (Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage), a term used in Medina which is comparable to Al-Tawafa Institution in Mecca. In the following we share some important notes we collected during the interviews:

- Some administrators, doctors, and nurses are not familiar with the necessary information related to their work; we noticed this through repetition, answer evasion, and even their tone.

- Regarding the people who speak languages and are in charge of translation, most of them are not fluent in Arabic nor English as the majority languages during the pilgrimage season.

- With regards to the lists of names of the translators, we noticed that the names of some people were written without their knowledge; also some wrote wrong email address or phone numbers, while others wrote their names even though they live in another city (it is important to note that they might be needed for emergencies).

- A large number of hospitals in the two holy cities use Google for translation which is useless especially in the health field and might negatively affect the diagnosis of the patient’s condition.

Based on the above mentioned, we have decided to make the following suggestions in order to improve interpretation services in the health field of the Kingdom:

- Organize training courses in interpretation for the health field for the people who want to participate. These courses are divided into two sections: theoretical and practical, knowing that each section requires a certain number of working hours. The theoretical section gives a general idea of interpretation in the health field, with other types of translations, in addition to the necessary norms that the translators should follow. The practical section is to apply the theories in the field and to give realistic examples to benefit from. Various prestigious universities around the world have adopted such programs, like the universities of Spain, United Kingdom, and Australia.

- Solving the problems of interpretation in the health field needs the adoption of unconventional ideas relying on the latest modern techniques available in order to better help the pilgrim.

Conclusion

After visiting hospitals in the two holy cities and collecting the necessary information from the previously mentioned categories, we acknowledge (as specialists in the field of oral and written translation) that professional interpretation services in the health field are not available during the pilgrimage seasons, but limited to Institutions Involved in Pilgrimage (Al-Tawafa) which in turn provides unqualified people to perform this role, which is very important especially in such gatherings, as well as nurses, doctors, and even sanitary workers who do not have any background of interpretation in the health field. These results are the same obtained by different authors who have conducted similar studies (Foulquié-Rubio et al., 2018, among others), such as in the description of the current situation of Public Service Interpreting in Spain.

Finally, despite the importance of interpretation in general and interpretation in the health field in particular, it does not receive the attention it deserves. This is why we need to improve it by working hard, especially where we can, in order to better communication with pilgrims, which will in turn help advance the services in this field provided by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

RECIBIDO EN octubre de 2018

ACEPTADO EN febrero de 2019

VERSIÓN FINAL DE junio de 2019

References

Abril, María Isabel (2006): La interpretación en los servicios públicos: caracterización como género, contextualización y modelos de formación. Hacia unas bases para el diseño curricular. Doctoral Thesis, Granada University.

Cambridge, Jan (1999): «Information Loss in Bilingual Medical Interviews Through an Untrained Interpreters», The translator , 5/2, 201-219.

Cambridge, Jan (2002): «Interlocutor Roles and the Pressures as Interpreters», in Carmen Valero-Garcés and Guzmán Mancho Barés (ed.) Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos: Nuevas necesidades para nuevas realidades / New Needs for New Realities, Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad, 121-126.

Cambridge, Jan (2003): «Unas ideas sobre la interpretación en los centros de salud» in Carmen Valero-Garcés (ed.) Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos. Contextualización, actualidad y futuro, Granada: Comares, 57-59.

Coller, Xavier (2000): Estudio de casos. Cuadernos Metodológicos, Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Foulquié-Rubio, Ana Isabel, Mireia Vargas-Urpi and Magdalena Fernández Pérez (2018): «Introducción 2006-2016: una década de cambios», in Ana Isabel Foulquié-Rubio, Mireia Vargas-Urpi and Magdalena Fernández Pérez (ed.) Panorama de la traducción y la interpretación en los servicios públicos españoles: una década de cambios, retos y oportunidades, Granada, Comares, 1-13.

Gentile, Adolfo, Uldis Ozolins and Mary Vasilakakos (1996): Liaison Interpreting: A Handbook, Melbourne: University Press.

Gentile, Adolfo, Uldis Ozolins and Mary Vasilakakos (1997): «Community Interpreting or Not? Practices, Standards and Accreditation», in Silvana E. Carr, Roda P. Roberts, Aideen Dufour and Dini Steyn (ed.) The Critical Link: Interpreters in the Community, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 109-118.

Hale, Sandra (2007a): Community Interpreting, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hale, Sandra (2007b): Quality in interpreting - a shared responsibility. Selected papers from the 5th International Conference on Interpreting in Legal, Health and Social Service Settings, Parramatta Australia, 2007, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Hale, Sandra (2010): La interpretación comunitaria la interpretación en los sectores jurídico, sanitario y social, Granada, Comares.

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (2017): Iḥsa´āt al-Haŷŷ. Available from: https://hajmap.stats.gov.sa/haj_1438.pdf. [Accessed: 2nd January 2018].

Martin, Anne (2000): «La interpretación social en España», in Dorothy Kelly (ed.) La Traducción y la Interpretación en España hoy: perspectivas profesionales, Granada: Comares, 207-223.

Martin, Anne (2003): «Investigación en interpretación social: Estado de la cuestión», in Emilio Ortega Arjonilla (ed.) Panorama actual de la investigación en traducción e interpretación (vol. 1), Granada: Atrio, 431-446.

Martin, Anne (2006): «La realidad de la Traducción y la Interpretación en los servicios públicos en Andalucía», Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 19/1, 129-150.

Mikkelson, Holly (1996): «Community Interpreting. An Emerging Profession», Interpreting, 1/1, 125-129.

Mikkelson, Holly (2002): «Adventures in online learning: Introduction to medical interpreting», in S. Brennan (comp.) Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference of the American Translators Association, Alexandria, VA: American Translators Association, 423-430.

Taibi, Mustapha (2011): Tarjamat Al-kadamat Al-’mmah [Community Interpreting and Translation], Rabat: Dar-Assalam.

Taibi, Mustapha (2016). New Insights into Arabic Translation and Interpreting, North York: Multilingual Matters.

Tomassini, Elena (2002): «Overview of interpreting in the health sector in the Emilia Romagna region», in Carmen Valero-Garcés, and Guzmán Mancho Barés (ed.) Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos: Nuevas Necesidades para Nuevas Realidades, Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá: Servicio de Publicaciones de la universidad. 193-199.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen and Guzmán Mancho Barés (ed.) (2002): Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos: Nuevas necesidades para nuevas realidades / New Needs for New Realities, Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen (2003): «Una visión general de la evolución de la Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos», in Carmen Valero-Garcés (ed.) Traducción e interpretación en los Servicios Públicos. Contextualización, actualidad y futuro, Granada: Comares. 3-33.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen (2005): Traducción como mediación entre lenguas y culturas/ Translation as mediation or how to bridge linguistic and cultural gaps, Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá. Servicio de publicaciones de la universidad.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen (2008a): Formas de mediación intercultural: Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos: Conceptos, Datos, Situaciones y Práctica, Granada: Comares.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen (2008b): Investigación y Práctica en Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos: desafíos y alianzas / Research and Practice in Public Service Interpreting and Translation: Challenges and Alliances, Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá. Servicio de publicaciones de la universidad.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen (2011): El futuro en el presente: Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos en un mundo INTERcoNEcTado (TISP en INTERNET), Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá. Servicio de publicaciones de la universidad.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen (2014): Considerando Ética e Ideología en Situaciones de Conflicto - (Re) visiting Ethics and Ideology in Situations of Conflict, Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá. Servicio de publicaciones de la universidad.

Valero-Garcés, Carmen (2017): Superando límites en traducción e interpretación en los servicios públicos / Beyond Limits in Public Service Interpreting and Translation, Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá. Servicio de publicaciones de la universidad.