The impact of typological differences on the perceived degree of dynamicity in motion events*

Paula Cifuentes-Férez

University of Murcia

Drawing from Talmy’s work on lexicalization patterns, and Slobin’s thinking-for-speaking hypothesis, the translation of motion has been an active arena for research. Recently, a new line of research on the reception of translations of motion has arisen, suggesting that typological differences have an impact on the target audience’s assessments about a translated text. This paper aims to explore the influence that typological differences between English and Spanish may have on readers’ judgments about the degree of dynamicity of the motion events narrated in original English texts and in Spanish translations. 20 excerpts were taken from 5 bestsellers written in English and their corresponding translations into Spanish. Participants were asked to rate in a 1 to 4 point scale the degree of dynamicity of the events described. Results suggest (a) Spanish translations did not differ in terms of dynamicity when path and manner information has been either lost or totally kept, and (b) that lexical verb choice in some English fragments together with the intrinsic nature of the events seemed to have an effect on the English audience’s judgments.

Keywords: motion events; dynamicity; English; Spanish; translation; reception.

El impacto de las diferencias tipológicas en el grado de percepción de dinamismo en los eventos de movimiento

La traducción de los eventos de movimiento, basada en la teoría de Talmy sobre los patrones de lexicalización y en la teoría neorelativista de pensar-para-hablar de Slobin, ha sido una prolífica área de investigación. En los últimos años, encontramos una nueva línea de investigación sobre la recepción de la traducción de eventos de movimiento que argumenta que las diferencias tipológicas influyen en las percepciones que la audiencia meta tiene sobre el texto traducido. El objetivo del presente trabajo es examinar el posible impacto que las diferencias tipológicas entre el español y el inglés tiene en la recepción de textos originales en inglés y sus correspondientes traducciones al español en cuanto al grado de dinamismo de los eventos narrados. Con tal fin en mente, se eligieron 20 fragmentos de 5 novelas en inglés con su respectiva traducción al español y se les pidió a los participantes que valoraran el grado de dinamismo de los eventos en una escala de 1 a 4. Los resultados muestran que (a) las traducciones al español se consideraban igual de dinámicas cuando se perdía información sobre el evento de movimiento, así como cuando se lograba mantener toda la información del texto original y (b) sugieren que la particular elección léxica en algunos fragmentos en inglés junto con la naturaleza intrínseca del evento narrado parecen haber tenido un impacto en la audiencia anglófona.

Palabras clave: eventos de movimiento; dinamismo; inglés; español; traducción; recepción.

1. Introduction

Typological studies on the linguistic expression of motion events are of great interest to translation studies. It is well known that languages differ in the way they lexicalise motion (Berman & Slobin, 1994; Strömqvist & Verhoeven, 2004; Talmy, 1985, 1991, 2000) and that translators have to conform to the target language rules when rendering texts between languages which belong to similar or different typological groups (Cappelle, 2012; Cifuentes-Férez, 2013; Filipović, 2007, 2008; Ibarretxe-Antuñano & Filipović, 2013; Slobin, 1996a, 2005).

Slobin’s (1996b, 2003, 2006) thinking-for-speaking hypothesis, based on Talmy’s (1985, 1991, 2000) semantic typology of languages, has proven fruitful for the investigation of how the differing attention paid to manner of motion by satellite-framed languages, such as English, and verb-framed languages, such as Spanish, have consequences for the translation product. This line of research pioneered by Slobin and which has been followed up by many scholars (e.g., Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 2003; Jaka, 2009; Cifuentes-Férez, 2013; Cifuentes-Férez & Rojo, 2015; Molés-Cases, 2015, 2016) shows that translators adapt the source text to the rhetorical style of the target audience, creating a text which is natural for their target readers. According to Slobin (1996a: 205), satellite-framed languages seem to “devote more narrative attention to the dynamics of movement” because of the availability of manner-of-motion verbs which can readily be followed by satellites and prepositional phrases to describe paths. Verb-framed languages, by contrast, devote less narrative attention to the dynamics of the motion event and more to the static setting and the result of the motion event.

The goal of this paper is to explore the effects that typological differences between English and Spanish may have on the reception of both source text and target text with regard to the readers’ judgments about the perceived degree of dynamicity of the motion events narrated.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a brief overview of the theoretical background of this paper which revolves around two points, namely, thinking-for-speaking/translating research, and the impact of typological differences on audience’s memory and judgments about an event. Then, Section 3 presents a reception study on the potential effects that English-to-Spanish translations may have on the target audience’s judgments of dynamicity of the events described. Last, Section 4 sums up the main conclusions and addresses some avenues for future research.

2. The impact of lexicalization patterns on language use and mental processes tied to language

2.1. Thinking-for-speaking research

The seminal work by Talmy (1985, 1991, 2000), among others, contributed to the renewed interest in linguistic relativity, that is, in how language thought under specific circumstances. Slobin’s (1991, 1996a, 2003, 2006) thinking-for-speaking hypothesis is a neorelativistic theory which claims that languages influences thought when we are using language, in other words, when we are thinking with the purpose of speaking, writing, translating, and even when listening, reading, imaging, etc.

Throughout Slobin’s work, he argues that the language one speaks has a pervasive effect on selective attention for particular motion event characteristics since speakers are constrained by the resources available in their languages. As Talmy’s work has shown, path of motion is the core component of a motion event. However, manner of motion is optional for verb-framed languages but easily encoded in satellite-framed languages. This results in differences between the rhetorical or narrative styles of each group of languages, as research compiled in volumes by Berman & Slobin (1994) and Strömqvist & Verhoeven (2004) has shown. On the one hand, satellite-framed languages typically provide rich and detailed path and manner descriptions as they can stack a great number of satellites and prepositional phrases after a single manner verb. Thus, motion descriptions seem to be highly dynamic1. On the other, verb-framed languages tend to provide less dynamic descriptions because they (a) only encode manner when is relevant to the context, (b) are constrained to use paths verbs when a boundary-crossing is predicated (Aske, 1989; Slobin & Hoiting, 1994; Alonso, 2013), and (c) tend to include only one ground per clause. Thus, Spanish motion descriptions tend to focus on the endpoint of the motion event. Following Ikegami’s (1991) terminology of become-language (i.e., which focuses on the change from one state into another) versus do-language (i.e., which focuses on the activity of an individual), verb-framed languages could be categorized as become-languages whereas satellite-framed languages would be categorized as do-languages.

As stated above, Slobin’s thinking-for-speaking hypothesis also applies or extends to thinking-for-translating. In his pioneering work, Slobin (1996a, 1997) examines translations between English and Spanish novels, analyses the translation strategies followed for the translation of manner and path of motion, and quantifies how much information is translated. Regarding path information, English translations were faithful to the original Spanish in most cases and even added some paths which were implicit in the Spanish source text. In contrast, when translating from English to Spanish, the Spanish target text kept only three quarters of the path descriptions found in the English source text due to the impossibility of expressing several trajectories with a single motion verb and to the boundary crossing constraint. Thus, English complex trajectories are broken up in Spanish translations by including a path verb for each one of the trajectories expressed by English satellites. Regarding manner information, when translating from English into Spanish, only half of the original English manner information was kept in the Spanish target text, while in translations from Spanish into English, most of the Spanish manner information was maintained and English translators also generally added manner descriptions not present in the Spanish source text. Apart from the aforementioned boundary-crossing constraint, differences in the semantic specificity exhibited between English and Spanish manner-of-motion verbs can also account for the high degree of manner loss found in the Spanish translations. According to Slobin (1997), all languages seem to have a two-tiered lexicon of manner verbs with (a) a general or superordinate level, represented by neutral, everyday verbs, such as walk, run, jump, fly, etc., and (b) a more specific and expressive level, such as amble, tiptoe, stroll, shuffle, stride —which denote different ways of walking—, and bounce, skid, vault, which refer to different ways of jumping. Furthermore, Slobin argues that languages do not distribute their verbs in the same way in the two tiers. Thus, English has a very extensive second tier (i.e., hyponyms) whereas the Spanish manner verb lexicon is not as rich and mainly consists of general manner-of-motion verbs (i.e., hyperonyms). Much in the same line, Cifuentes-Férez (2009) remarks that there are some similarities in the way the two languages devote the greatest part of their verb lexicon to distinct motor patterns and in the way they organise the subdomain of human locomotion (both of them have more walking verbs than running or jumping ones), but there are also important cross-linguistic differences: English manner verbs outnumber those of Spanish—as already suggested in previous research by Slobin (2004, 2006)—and tend to exploit some manner parameters2 much more often than Spanish manner verbs. On the whole, it can be concluded that a significant part of manner-of-motion information and some path information tend to get lost in English-into-Spanish translation whereas such information tends to be added in Spanish-into-English translation. Slobin (2005) corroborates previous findings in a larger project in which he examines the translations of Tolkien’s 1937 novel The Hobbit into nine languages (satellite-framed: Dutch, German, Russian and Serbo-Croatian; verb framed: French, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish and Hebrew).

Based on Slobin’s work, other scholars working on both inter- and intra-typological translation of motion events have expanded the list of translation strategies (e.g., Cifuentes-Férez, 2013; Jaka, 2009; Ibarretxe-Antuñao, 2003; Ibarrexte-Antuñano & Filipović, 2013; Molés-Cases, 2016), emphasized the role of intratypological contrast (e.g., Filipović, 1999; Ibarretxe-Antuñao, 2003) and even broken ground to explore the impact of typological differences on the translation process (Cifuentes-Férez & Rojo, 2015). Overall, this research provides further support to Slobin’s findings. In a few words, translators actually accommodate the source text to the demands of the target language, thus, conforming to the narrative style of the target audience.

The bulk of research on thinking-for-translating discusses the consequences that inter- and intra-typological differences may have on the translation as a product; however, with a few exceptions it does not explore the impact that the actual translation product has on the target audience. In the following section, an overview of this groundbreaking line of research is presented.

2.2. Effects of typological differences on the audience

Research on linguistic relativity based on the different lexicalisation patterns for motion events has been very prolific3 and has provided both positive and negative evidence for the influence of language on cognition. Some of the studies which have provided evidence for an influence of language in memory tasks4 are Filipović (2011a), Filipović & Geva (2012) and Feist & Cifuentes-Férez (2013). Filipović (2011a) showed that English speakers perform better than Spanish speakers in a recognition memory task that involved verbalizing and remembering complex motion events (i.e., three manners of motion were involved for each motion event). The results were replicated in Filipović & Geva (2012), which also showed that the typological advantage for English speakers was not found when the covert and the overt verbalisation of the events was inhibited. Thus, it seems that language is used explicitly or tacitly as a tool or an aid to problem solving (e.g., Gentner & Goldin-Meadow, 2003) and no language-specific effects are found when free overt or covert encoding is disabled. Much in line with previous findings, Feist & Cifuentes-Férez (2013) observed that English speakers produced fewer errors than Spanish speakers in a recognition memory task which involved basic motion events (i.e., a manner plus a path of motion), suggesting once more that habitual attention to manner by English speakers may result in greater attention to fine details of manner. Unlike Filipović (2011a) and Filipović & Geva (2012), in Feist & Cifuentes-Férez (2013) language was not used and yet a language effect was found. Overall, these three studies support the linguistic relativity hypothesis and Slobin’s thinking-for-speaking hypothesis.

Apart from the effects of linguistic framing on memory, the different lexicalisation patterns have been reported to influence people’s judgments. Filipović (2011b) argues that readers’ judgments on the violence of an event can be affected by the presence or absence of manner in the original text and the translation. The stimuli for her study were eight sentences taken from an online newspaper available in both English and Spanish. The original language of the stimuli was Spanish and the English translation of the same sentences was provided by the newspaper. The results reveal that speakers who read about the events in English rated the violence described higher than those who read about it in Spanish since, overall, English translations of the Spanish statements added manner information which was absent in the original (e.g., He slammed me down to the ground as a translation for Me tiró al suelo «(he) threw me to the floor». Along the same lines, Trujillo (2003), in a study which just focused on English speakers, found significant differences in readers’ ratings for violence between high-manner descriptions containing manner-of-motion verbs and neutral-manner descriptions containing path verbs, suggesting that lexical choices may have an impact on the audience’s perception and subsequent judgments of the same events. More recently, Rojo & Cifuentes-Férez (2017) investigated the effect that loss of manner information in English-into-Spanish translation has on the readers’ judgments on the events being reported. Based on findings from previous related studies, they hypothesized that losing manner in the Spanish translation of an English crime account would decrease the perceived violence and, thus, would elicit a less severe judgment than that elicited by translations that maintain a higher degree of manner information. Five testimonies of assault and battery crimes were taken from Trujillo (2003) and from www.verdictsearch.com. Then, they were adapted and translated into Spanish. Two different versions were provided for each testimony but the baseline testimony: one version with high-manner descriptions and one with low-manner descriptions. Participants were told to assess the degree of violence on a one-to-nine scale, and to decide whether the crime would be punishable with a fine for a certain amount of money and/or a sentence to prison confinement for a given period of time. Results revealed that translations with more manner details were judged as more violent than those with a lower degree of manner, except for the most violent crime and the least violent one. Moreover, translations with more manner details showed weaker correlations between ratings of violence and strength of punishments, suggesting that participants had more problems deciding on a punishment when perceived violence was higher.

These last studies illustrate the extent to which speakers can experience and understand events in different ways based on the language in which the texts are written and on the particular wording of it. In the following section a reception study is presented in order to provide further insights into the reception of both original and translated texts as well as into the potential impact that the loss of manner and/or path information in English-into-Spanish translation may have on the target audience.

3. Degree of dynamicity in English-Spanish translation5

This study sets out to explore (1) whether linguistic framing may influence speakers’ perception of the dynamicity of a motion event and (2) whether the loss of manner and/or path information characteristic of English-into-Spanish translation may result in less dynamic events in the Spanish target texts. In order to investigate these issues, we asked English and Spanish speakers to read brief fragments containing motion events and assess their degree of dynamicity on a 1 to 4 scale, where 1 was not dynamic at all and 4 was very dynamic.

The first hypothesis is that English original excerpts are likely to be perceived as more dynamic (and centred on the action) than their corresponding Spanish translations, as might be expected due to their different rhetorical or narrative styles. The second hypothesis is that Spanish translations in which manner and/or path information has been omitted totally or partially are likely to be assessed as less dynamic than Spanish translations in which manner and path information has been fully rendered.

3.2. Participants

40 native English speakers from the University of Louisiana, University of Georgia (US), and East Anglia University (UK) and 45 native Spanish speakers from the University of Murcia (Spain) volunteered to participate in the study. The mean age for English participants was 23.68 with a standard deviation of 2.91, and for Spanish participants was 20.29 with a standard deviation of 2.48. This indicates that variability in terms of age is scarce. On the contrary, variability in terms of sex can be observed. 26 (65%) out of the 40 English participants and 38 (84.4%) out of the 45 Spanish ones were female, whereas 14 (35%) in the English group of participants were male and 7 (15.6%) in the Spanish one were male.

3.3. Materials and design

We selected a total of 20 excerpts (see Appendix) from 5 bestsellers—four fragments for each—written in English and their corresponding translations into Castilian Spanish:

- Boyne, John. 2006. The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. Ireland: David Fickling Books.

- Boyne, John. 2006. El niño con el pijama de rayas. Translated by Gemma Rovira Ortega. Barcelona: Salamandra.

- Collins, Suzanne. 2010. Mockingjay. New York: Scholastic Press.

- Collins, Suzanne. 2010. Sinsajo. Translated by Pilar Ramírez Tello. Barcelona: Molino.

- Follet, Ken. 2008. World without End. Nueva York: New American Library.

- Follet, Ken. 2007. Un mundo sin fin. Translated by ANUVELA. Barcelona: Plaza Janés.

- Rowling, J.K. 2003. Harry Potter and the order of the Phoenix. London: Bloomsbury.

- Rowling, J.K. 2004. Harry Potter y la orden del Fénix. Translated by Gemma Rovira Ortega. Barcelona: Salamandra.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. 2002. The Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. 1982. El Hobbit. Translated by Manuel Figueroa. Barcelona: Minotauro.

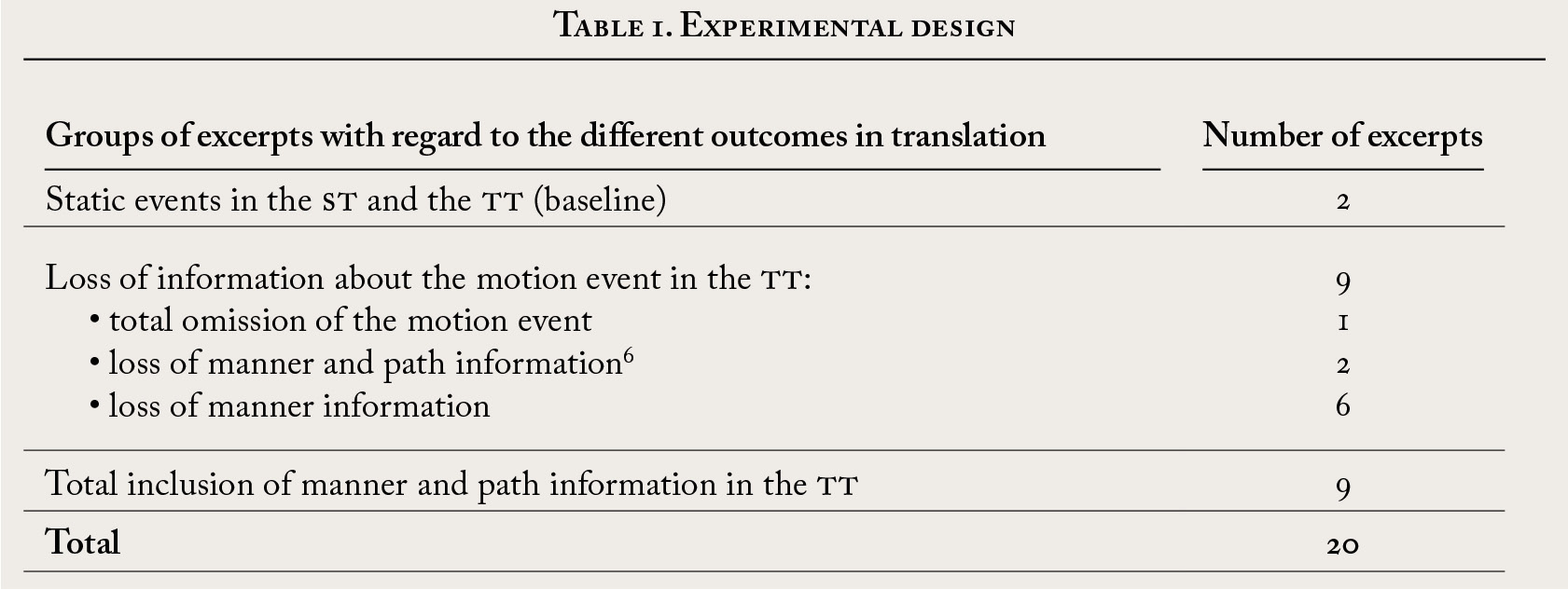

As Table 1 illustrates, 2 excerpts describing static events were selected to serve as a baseline. 9 excerpts involved loss of information about the motion events in the target text and other 9 excerpts maintained the motion event information encoded in the English source text.

The dependent variable is the degree of rated dynamicity and the independent variables are the three groups of excerpts: static events, loss of information about the motion event in the target text—which is further subdivided into three groups—, and total inclusion of manner and path information.

3.4. Procedure

Participants were given a link to access an online survey. They were asked about their sex, age, and mother tongue. They were told to read carefully 20 excerpts from bestsellers at their own pace and rate the degree of dynamicity of the events being depicted on the 1 to 4 scale, with 1 = not dynamic at all and 4 = very dynamic. The order of presentation of the excerpts was randomized to avoid carry-over effects. No time limit was given.

3.5. Results and discussion

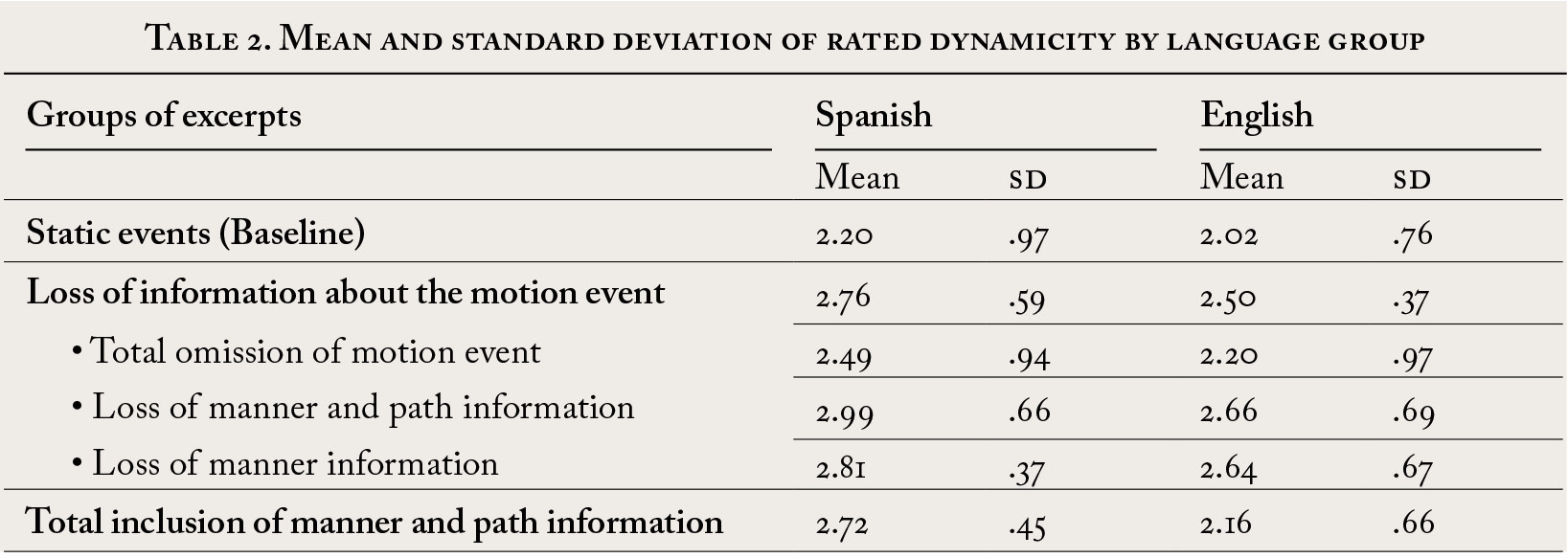

Descriptive statistics results, displayed in Table 2, show that Spanish participants overall gave slightly higher ratings in terms of dynamicity than did English participants across all five groups of excerpts.

Before dealing with differences between language groups, non-parametric tests were performed to find whether there were statistically significant differences in the degree of dynamicity among the groups of extracts from the English originals selected for our study. The reader should have in mind that the labels given to the groups of excerpts refer to the outcome in the English-into-Spanish translation and not to specific features of the English source texts. Friedman chi-square tests showed that there were significant differences among the groups of excerpts (X2 = .000, p < .05). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon tests revealed that dynamicity ratings for the group of static events (baseline) were significantly different from the loss of information group (T = .013, p < .05) and the total inclusion of information group (T = .000, p < .05). Moreover, significant differences were found between the loss of information group and the total inclusion of information group (T = .000, p < .05). As can be seen in Table 2, the mean rating for the loss of information group is higher (M = 2.50; SD = .37) than the mean rating for the total inclusion of information group (M = 2.16; SD = .66). A closer look at the excerpts selected for each group suggests that the particular verb choice by English-speaking writers for the total inclusion of information group might have played a role in the perceived degree of dynamicity. More concretely, seven out of the nine excerpts within the group contain path verbs such as fall, pass, reach, return, and more generic manner verbs, such as walk and step, whereas excerpts in the loss of information group contain more specific manner verbs such as climb, huddle, hunch, rattle, skid, slide, slip, scramble, and soar.

If we focus on language group differences regarding the static events, which act as a baseline here, it was found that they were rated as the least dynamic events by the two language groups (Spanish, M = 2.20, SD = .97; English, M = 2.02, SD = .76). Descriptive statistic results show that the mean rates by each language group are very close, suggesting the comparability between the two language groups. Non-parametric tests were also performed to assess whether there were any statistically significant differences between both language groups. Mann-Whitney tests revealed that the two language groups did not differ significantly in their ratings for the baseline.

With regard to the other groups of excerpts, both language groups rated the highest degree of dynamicity in the excerpts involving loss of manner and path information in the Spanish translations (Spanish, M = 2.99, SD = .66; English, M = 2.66, SD = .69), yet statistically significant differences were found between the language groups (U = .034, p < .05). This group consists of excerpt 2 and excerpt 3 (see Appendix). Excerpt 2 depicts a reptilian winged horse rising up out of the like a giant bird, and excerpt 3 describes a scene in which someone is having a distant view of the Gryffindor Quidditch team soaring up and down the pitch.

Mann-Whitney tests also reveal a remarkable difference between language groups in their ratings with respect to excerpts in the total inclusion of manner and path information group (U = .000, p < .05), with the target texts in Spanish (M = 2.72, SD = .45) rated as much more dynamic than the English source texts (M = 2.16, SD = .66).

Further Mann-Whitney tests were carried out so as to find where the statistical differences were within each group of excerpts. Within the loss of manner and path information group, ratings for excerpt 3 by each language group were statistically different (Spanish, M = 2.82, SD = .96; English, M = 2.35, SD = .89). Within the total inclusion of manner and path information group, ratings for excerpts 8, 9, 10, 11, 15, 17 and 18 by each language group were statistically different, that is, seven out of the nine excerpts included in this group.

In order to shed light on these results, a qualitative analysis of the excerpts is needed. As example 1 illustrates, in excerpt 3 manner information about how quickly the team is flying as well as the upward and downward trajectory get lost in translation. Despite this, the mean rating from Spanish participants (M = 2.82, SD = .96) is, as shown earlier, higher than the rating from English participants (M = 2.35, SD = .89).

(1) Excerpt 3

a. English source text: He now had a distant view of the Gryffindor Quidditch team soaring up and down the pitch.

b. Spanish target text: A lo lejos veía al equipo de quidditch de Gryffindor volando por el campo (lit. «far away (he) saw the team of quidditch of Gryffindor flying over the pitch»)

A plausible explanation for the much lower rating in dynamicity by English participants is that the collocation acting as the main verb of the sentence (i.e., to have a distant view) might have guided their judgement about the degree of dynamicity of the event. In other words, the act of looking at a motion event might have been considered as the main action and, therefore, judged accordingly. However, the same does not seem to be true for Spanish.

With regard to the seven excerpts that yielded significant results for the total inclusion of manner and path information groups, a qualitative analysis of the type of motion verbs included in the English excerpts shows that many path verbs (e.g., fall, reach, return, pass) and more generic or superordinate manner verbs (e.g., walk, step6) were used, as shown in examples 2-9. The particular verb choice made by the writers of the bestsellers seems to have helped Spanish translators to render all the information contained in the original English excerpts since Spanish does possess equivalent path verbs and manner verbs. In addition, it might have pushed English participants to rate the events as much less dynamic than when the characteristic English lexicalization pattern (i.e., manner verb + path expressions) is used and/or more energetic motion events are described.

(2) Excerpt 8: With every step he seemed to face the danger of toppling over and falling down, but he never did and managed to keep his balance, even at a particularly bad part where, when he lifted his left leg, his boot stayed implanted in the mud while his foot slipped right out of it.

(3) Excerpt 9: Shmuel reached down and lifted the base of the fence, but it only lifted to a certain height and Bruno had no choice but to roll under it, getting his striped pyjamas completely covered in mud as he did so.

In examples 2 and 3, we find the path verbs to fall, to lift, and to reach. To fall denotes downward motion, whereas to lift upwards motion and to reach generally refers to the accomplishment of the figure’s (Shmuel) movement towards a goal (i.e., the base of the fence). The nature of the events of falling, lifting and reaching, devoid of manner information, may explain why those two excerpts are perceived as less dynamic, even though in both excerpts one or two manner verbs are found. In example 2 (excerpt 8), the manner verb to topple denotes unsteady motion, but unlike other verbs depicting unsteady motion, the figure falls down as result of its loss of balance. However, in this instance, it is important to notice here that the figure was in danger of toppling, but did not in fact do so. The manner verb to slip in this particular context means to slide unintentionally. In example 3 (excerpt 9), the manner verb to roll denotes moving forward on a surface by turning over and over.

(4) Excerpt 10: With that remark she walked away, returning across the hallway to her bedroom and closing the door behind her.

(5) Excerpt 11: All around the house in Berlin were other streets of large houses, and when you walked towards the centre of town there were always people strolling along and stopping to chat to each other.

(6) Excerpt 17: They walked along the muddy bank of the river, past warehouses and wharves and barges.

In examples 4, 5 and 6, the generic manner verb to walk is found followed by different path expressions (away, towards the centre of town, along the muddy bank […] past […]). Moreover, the manner verb to stroll, which denotes to walk in a slow relaxed manner usually for pleasure, is found in example 5. Although to stroll is a quite specific manner verb, the event of strolling along the streets may be judged as less dynamic than other events involving manner verbs conveying more energy and/or speed. With regard to example 4 (excerpt 10), in addition to the generic manner verb to walk, the path verb to return is found. In general, it seems that the events narrated filtered through the verb choice made by the writers might have made the reader perceive and, thus, rate them as less dynamic than other motion events. A case in point would be example 4, in which the verb to storm could have been used instead of to walk, and to slam instead of to close to denote that the figure is somehow angry after something happened and storms across the hallway to her bedroom, slamming the door behind her—which is the inference the reader might make when reading this particular excerpt in the novel.

(7) Excerpt 15: Boggs guides Finnick and me out of Command, along the hall to a doorway, and onto a wide stairway.

Example 7 contains the verb to guide7 which denotes that multiple figures move together in a particular direction, in this case, along the hall to a doorway, and then onto a wide stairway. This verb does not encode any information about how the figures (Boggs, Finnick, and the narrator) are moving along the trajectory described. Once more, the reader might have inferred that the default manner of motion would be walking and, thus, have rated the event as less dynamic.

(8) Excerpt 18: […] a kitchen boy passed through the room and went up the stairs carrying a tray with a big jug of ale and a platter of hot salt beef.

In example 8, the path verb to pass and the deictic verb to go are found in the description. No manner verb is used in excerpt 18. In the scene narrated, the omniscient narrator tells us about a boy passing through the room and going up the stairs, providing no further information about how the boy proceeds and making the reader infer that he was more likely than not walking. Again, the nature of the event being described might be responsible for the lower ratings.

(9) Excerpt 19: She tried to step backward, hoping to force a gap in the bodies behind her, but everyone was still pressing forward to look at the bones of the saint.

In example 9, the verb to step denotes lifting one foot or both feet and setting it/them down again, in other words, to walk. This example depicts a scene in which she is unable to move despite trying to force a gap. As a result, the intrinsic nature of the narrated event might account for the lower ratings on dynamicity for excerpt 19. However, the question still remains open as to why the very same event in Spanish was rated much higher in terms of dynamicity.

Finally, Wilcoxon tests were performed to assess whether there were significant differences in dynamicity between the loss of information group and the total inclusion of information group in the Spanish excerpts as it was hypothesized that lower dynamicity ratings would be found for the loss of information group than for the total inclusion of information group. Wilcoxon tests did not reach significance, that is, Spanish target texts from the two groups of excerpts did not differ in terms of dynamicity, suggesting that the observed differences in dynamicity in the originals were not preserved in translation. The translation product in Spanish in these two groups of excerpts, faithful to the target-text narrative style, seems to be perceived and, as a result, judged similarly in terms of dynamicity.

On the whole, our results neither provide support for our first hypothesis nor for the second hypothesis. The first hypothesis stated that English original excerpts would be likely to be perceived as more dynamic than their corresponding Spanish translations, whereas the second hypothesis was that Spanish translations in which manner and/or path information had been omitted totally or partially would be more likely to be assessed as less dynamic than Spanish translations in which manner and path information had been fully rendered. Contrary to these hypotheses, Spanish target excerpts overall were rated higher in terms of dynamicity, but differences between both language groups only reached statistical significance for the group of excerpts whose path and manner information was fully rendered in the Spanish target excerpts. A closer look at those excerpts revealed that differences between the language groups could be due to the verb choice in the English original excerpts and the intrinsic nature of the narrated event. Moreover, within the Spanish language group, no difference in terms of dynamicity were found between excerpts which lost path and manner information and those which kept all information. The most plausible reason is that translators conform to the rhetorical style of the target language irrespective of the lexical choice in the English source excerpts which may either facilitate or hinder the translation process. It seems likely that when an event is being described in the usual way, i.e., following the target language conventions, the dynamicity of the event might be conditioned by the intrinsic nature of the events instead of by how much manner and/or path information is encoded.

4. Conclusions

The study introduced in the present paper has explored the issue of whether and to what extent the different lexicalization patterns in English and Spanish may result in more or less dynamic events by comparing the perceived dynamicity of the events in English original fragments and their corresponding Spanish translations, and provided evidence that Spanish translations seem to produce the same effect in terms of the dynamicity of the narrated events on the target audience. Additionally, the paper provides insights into the role that the particular wording of some English fragments seems to play on the audience’s judgments, corroborating findings from previous related research (e.g., Trujillo, 2003; Filipović, 2011b; Rojo & Cifuentes-Férez, 2017).

Results suggest that Spanish readers perceive the same degree of dynamicity in events in which path and manner information contained in the original excerpt has been lost and in those which managed to keep path and manner information. What is kept or lost in translation might be one of the main concerns of translation scholars and translators, but actual readers deal with the actual product of translation. English-into-Spanish translators are guided by the narrative style of the target language which, in turn, is restricted by the linguistic resources available in the language, such as the more restricted manner verb lexicon or the impossibility to express complex trajectories after a single motion verb. The fact that Spanish narratives neither contain as vivid and expressive manner information nor as elaborated path descriptions as do English descriptions does not seem to result in less dynamic motion events in Spanish, but just in motion events hand-embroidered in the way Spanish readers expect.

Moreover, this paper has also suggested that verb choice made by the English writers might influence English participants’ judgments in terms of dynamicity of an event. Namely, when an event is narrated using path verbs and/or generic or less specific manner verbs, the event seemed to be rated as much less dynamic as opposed to other events which conformed more closely to their narrative or rhetorical style, i.e., use of manner verbs followed by path expressions. However, a sound conclusion cannot be drawn since verb choice has not been separated from the intrinsic dynamicity of the event itself. The role of the wording might be also connected to the potential influence of the intrinsic nature of the events being described. The excerpts selected as materials for the study depict motion events which might be assessed along a cline of dynamicity—ranging from low dynamic events to highly dynamic events. However, the question still remains unanswered as to why this might have only affected English readers.

For future research, it would be interesting to expand this study to other verb- and satellite-framed languages to test whether and to what extent our findings apply to other language pairs, including other languages that either belong to the same or different typological groups. Moreover, it would be worthwhile to use a large corpus of original texts and translated texts, and to place events along a cline of dynamicity so as to further explore the impact of the intrinsic nature of the narrated event together with the impact of linguistic framing. Finally, it would also be interesting to look at the same event, framed in different ways linguistically, both within and across languages.

To conclude, Slobin’s thinking-for-translating, drawing from Talmy’s seminal work on lexicalization patterns for motion, has proven useful for reception and descriptive translation studies. The study presented in this paper focuses on the reception of both original and translated texts, highlighting the importance of the audience in the translation process but overlooking the actual translation process. We hope that researchers interested in motion and translation will adopt a joint perspective to approach translation since reception research and translation process research complement each other, shedding light on the two faces of the same coin.

Recibido en junio de 2015

Aceptado en abril de 2016

Versión final de noviembre de 2016

5. References

Alonso, Rosa (2013). «Motion events in L2 acquisition: the boundary-crossing constraint in English and Spanish». US-China Foreign Language, 11/10, pp. 738-750.

Aske, John (1989). «Path predicates in English and Spanish: A closer look». Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 15, pp. 1-14.

Berman, Ruth & Slobin, Dan I. (1994). Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cappelle, Bert (2012). «English is less rich in manner-of-motion verbs when translated from French». Across Languages and Cultures, 13/2, pp. 173-195.

Cifuentes-Férez, Paula (2009). A Crosslinguistic Study on the Semantics of Motion Verbs in English and Spanish, Munich: LINCOM.

— (2013). «El tratamiento de los verbos de manera de movimiento y de los caminos en la traducción inglés-español de textos narrativos». Miscelánea, 47, pp. 53-80.

Cifuentes-Férez, Paula & Rojo, Ana (2015). «Thinking for translating: a think-aloud protocol on the translation of manner-of-motion verbs», Target, 27/2, pp. 379-300.

Feist, Michele I. & Cifuentes-Férez, Paula (2013). «Remembering how: language, memory and the salience of manner», Journal of Cognitive Science 14/4, pp. 379-398.

Filipović, Luna (2007). Talking about Motion: A Crosslinguistic Investigation of Lexicalization Patterns. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

— (2011a). «Speaking and remembering in one or two languages: Bilingual vs. monolingual lexicalization and memory for motion events», International Journal of Bilingualism, 15/4, pp. 466-485.

— (2011b). Bilingual witness report and translation: Final research report. Manuscript, University of Cambridge.

Filipović, Luna & Geva, Sharon (2012). «Language-specific effects on lexicalization and memory of motion events». In L. Filipović and K. Jaszczolt (eds.) Space and Time across Languages and Cultures: Language Culture and Cognition [Human Cognitive Processing 37], Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 269-282.

Filipović, Luna & Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide (2015). «Motion». In E. Dabrowska & D. Divjak (Eds.), Mouton Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 526-545.

Gentner, Dedre & Golding-Meadow, Susan 2003, Language in mind: Advances in the study of language and thought. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide (2003). «What translation tells us about motion: A contrastive study of typologically different languages», International Journal of English Studies 3/2, pp. 153-178.

— (2006). Sound symbolism and motion in Basque, Munich: Lincom Europa.

Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide & Filipović, Luna (2013). «Lexicalisation patterns and translation». In A. Rojo & I. Ibarretxe-Antuñano (eds.), Cognitive Linguistics and Translation: Advances in Some Theoretical Models and Applications, Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 251-281.

Ikegami, Yoshihiko (1991). «“DO-language” and “BECOME-language”: Two contrasting types of linguistic representation». In Y. Ikegami (Ed.), The empire of signs: semiotic essays on Japanese culture, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 285-326.

Jaka, Aiora (2009). «Mugimenduzko ekintzak ingelesez eta euskaraz, Sarrionandiaren itzulpen baten azterketatik abiatuta» [Motion events in English and Spanish: a translation study], Uztaro 69: pp. 53-76.

Levin, Beth (1993). English Verb Classes and Alternations: A preliminary investigation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Loftus, Elizabeth F. & Palmer, John C. (1974). “Reconstruction of Automobile Destruction: An Example of the Interaction Between Language and Memory”. Journal of Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13/15, pp. 585-589.

Molés-Cases, Teresa (2015). «La “saliencia” de la manera en los eventos de movimiento. Propuesta de técnicas de traducción». In I. Ibarretxe-Antuñano & A. Hijazo-Gascón (eds.), New Horizons in the study of Motion: bringing together applied and theoretical perspectives. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

— (2016). La traducción de los eventos de movimiento en un corpus paralelo alemán-español de literatura infantil y juvenil. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Rojo López, Ana & Cifuentes-Férez, Paula (2017). «On the reception of translations: Exploring the impact of typological differences on legal contexts». In I. Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide (ed.), Motion and space across languages and applications, Amsterdam, John Benjamins, pp. 367-398.

Slobin, Dan I. (1991). «Learning to think for speaking: Native language, cognition, and rhetorical style», Pragmatics, 1, pp. 7-26.

— (1996a). «From “thought and language” to “thinking for speaking”». In J. Gumperz & S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking Linguistic Relativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 195–217.

— (1996b). «Two ways to travel: Verbs of motion in English and Spanish». In M. Shibatani & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), Essays in semantics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 195-219.

— (2003). «Language and thought online: Cognitive consequences of linguistic relativity». In D. Gentner & S. Goldin-Meadow (eds.), Language in mind Advances in the investigation of language and thought, Cambridge, MA: the MIT Press, pp. 157-191.

— (2004). «The Many Ways to Search for a Frog: Linguistic Typology and the Expression of Motion Events». In Relating Events in Narrative: Typological and Contextual Perspectives in Translation, ed. by Sven Strömqvist and Ludo Verhoeven, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 219-257.

— (2005). «Relating narrative events in translation». In D. D. Ravid & H. Bat-Zeev Shyldkrot (Eds.), Perspectives on Language and Language Development: Essays in Honor of Ruth A. Berman, Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 115-129.

— (2006). «What Makes Manner of Motion Salient?» In M. Hickman & S. Robert (Eds.), Space in Languages: Linguistic Systems and Cognitive Categories, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 59-82.

Slobin, Dan I. & Hoiting, Nini (1994). «Reference to movement in spoken and signed languages: Typological considerations». Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 20, pp. 487-505.

Strömqvist, Sven & Verhoeven, Ludo (eds.). (2004). Relating Events in Narrative: Typological and Contextual Perspectives, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Talmy, Leonard (1985). «Lexicalization patterns: Semantic structure in lexical forms». In T. Shopen (ed.), Language typology and lexical descriptions: Vol. 3. Grammatical categories and the lexicon, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 36-149.

— (1991). «Path to realization: a typology of event conflation». Berkeley Linguistic Society,7, pp. 480-519.

— (2000). Toward a cognitive semantics: Vol. I & II. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Trujillo, Jennifer (2003). The difference in resulting judgments when descriptions use high-manner versus neutral-manner verbs, unpublished senior dissertation, University of California Berkeley.

Appendix. Materials

1. He was a skinny, black-haired, bespectacled boy who had the pinch, slightly unhealthy look of someone who has grown a lot in a short space of time.

Era un chico delgado, con el pelo negro y con gafas, que tenía el aspecto enclenque y enfermizo de quien ha crecido mucho en poco tiempo.

Lit. He was a skinny boy, with black hair and glasses, who had the unhealthy and weak look of someone who has grown a lot in little time.

2. A great, reptilian winged horse rose up out of the trees like a grotesque, giant bird.

Un enorme caballo alado con aspecto de réptil se irguió entre los árboles como un gigantesco y grotesco pájaro.

Lit. «A great, reptilian winged horse stood up between the like a grotesque, giant bird.»

3. He now had a distant view of the Gryffindor Quidditch team soaring up and down the pitch

A lo lejos veía al equipo de quidditch de Gryffindor volando por el campo.

Lit. «Far away (he) saw the Gryffindor Quidditch team flying over the pitch.»

4. So Dori actually climbed out of the tree and let Bilbo scramble up and stand on his back.

De modo que Dori bajó realmente del árbol y ayudó a que Bilbo se le trepase a la espalda.

Lit. «So Dori actually descended the tree and help Bilbo to climb onto his back.»

5. He still wandered on, out of the little high valley, over its edge, and down the slopes beyond.

Continuó caminando, fuera del pequeño y elevado valle, por el borde, y bajando luego las pendientes.

Lit. «(He) went on walking, out of the little and high valley, over its edge and descending the slopes.»

6. There was no time to count, as you know quite well, till we had dashed through the gate-guards, out of the lower door, and helter-skelter down here.

No hubo tiempo para contar, como tú sabes muy bien, hasta que nos abrimos paso entre los centinelas, salimos por la puerta más baja, y descendimos hasta aquí atropellándonos.

Lit. «There was no time to count, as you know quite well, until we had opened our way through the gate-guards, exited through the lower door, and descended until here trampling on each other.»

7. […] they were sliding away, huddled all together, in a fearful confusion of slipping, rattling, cracking slabs and stones.

[…] el grupo descendió en montón, en medio de una confusión pavorosa de bloques y piedras que se deslizaban golpeando y rompiéndose.

Lit. «The group descended in droves, in the mid of a fearful confusion of slabs and stones which slid cracking and breaking themselves.»

8. With every step he seemed to face the danger of toppling over and falling down, but he never did and managed to keep his balance, even at a particularly bad part where, when he lifted his left leg, his boot stayed implanted in the mud while his foot slipped right out of it.

A cada paso que daba se arriesgaba a tropezar y caerse, pero eso no llegó a suceder y consiguió mantener el equilibrio, incluso en un tramo del camino particularmente difícil, cuando levantó la pierna izquierda, la bota se quedó enganchada en el barro y el pie se le salió.

Lit. «With every step he took he ran the risk of toppling over and falling down, but that never happened and managed to keep his balance, even at a particularly bad part of the path where, when he lifted his left leg, his boot stayed stuck in the mud while his foot exited.»

9. Shmuel reached down and lifted the base of the fence, but it only lifted to a certain height and Bruno had no choice but to roll under it, getting his striped pyjamas completely covered in mud as he did so.

Shmuel se agachó y levantó la base de la alambrada, que sólo cedió lo justo, por lo que Bruno tuvo que arrastrarse por debajo; al hacerlo, su pijama de rayas quedó completamente embarrado.

Lit. «Shmuel crouched down and lifted the base of the fence, which only lifted a little enough and Bruno had to drag under it; as he did so, his striped pyjamas was completely covered in mud.»

10. With that remark she walked away, returning across the hallway to her bedroom and closing the door behind her.

Y echó a andar, cruzó el pasillo, entró en su dormitorio y cerró la puerta.

Lit. «And (she) started to walk, crossed the hall, entered in her room and closed the door.»

11. All around the house in Berlin were other streets of large houses, and when you walked towards the centre of town there were always people strolling along and stopping to chat to each other.

Alrededor de Berlín había otras calles con grandes casas, y cuando caminabas hacia el centro de la ciudad siempre encontrabas personas que paseaban y se paraban para charlar un momento.

Lit. «Around Berlin there were other streets of large houses, and when you walked towards the centre of town you always found people strolling and stopping to chat for a moment.»

12. Machine gun fire coming from the roof of the dirt brown warehouse across the alley. Someone is returning fire.

Sin esa distracción oigo otro sonido: ametralladoras que disparan desde el tejado del almacén color tierra del otro lado del callejón: alguien responde al ataque.

Lit. «Without that distraction I hear another sound: machine guns firing from the roof of the brown warehouse on the other side of the alley: someone is answering to the attack.»

13. Before anyone can stop me, I make a dash for an access ladder and begin to scale it. Climbing. One of the things I do best.

Antes de que puedan detenerme, corro hacia una escalera de acceso y empiezo a subir, a trepar, una de las cosas que mejor se me dan.

Lit. «Before anyone can stop me, I run towards an access ladder and begin to ascend, to climb, one of the things I do best.»

14. We skid into a nest with a pair of soldiers, hunching down behind the barrier.

Nos metemos en un nido con un par de soldados y nos agachamos detrás de la barrera.

Lit. «We entered in a nest with a pair of soldiers and we crouched down behind the barrier.»

15. Boggs guides Finnick and me out of Command, along the hall to a doorway, and onto a wide stairway.

Boggs nos saca a Finnick y a mí de la sala de mando, y nos lleva por el pasillo hasta una puerta y las amplias escaleras que hay detrás.

Lit. «Boggs takes Finnick and me from the command room, and takes us along the hall until a door and the wide stairway behind it.»

16.Gwenda was eight years old, but she was not afraid of the dark.

Gwenda solo tenía ocho años, pero no le temía a la oscuridad.

Lit. «Gwenda was only eight years old, but she was not afraid of the dark.»

17. They walked along the muddy bank of the river, past warehouses and wharves and barges.

Avanzaron por la lodosa orilla del río y dejaron atrás varios almacenes, embarcaderos y gabarras.

Lit. «They advanced along the muddy river bank and left behind some warehouses, wharves and barges.»

18. […] a kitchen boy passed through the room and went up the stairs carrying a tray with a big jug of ale and a platter of hot salt beef.

[…] un mozo de cocina atravesó la estancia y subió la escalera con una bandeja en la que portaba una enorme jarra de cerveza y una fuente de ternera ahumada.

Lit. «A kitchen boy crossed the room and ascended the stairs with a tray with a big jug of ale and a platter of smoked beef.»

19. She tried to step backward, hoping to force a gap in the bodies behind her, but everyone was still pressing forward to look at the bones of the saint.

Intentó retroceder con la esperanza de abrirse camino entre los cuerpos que tenía detrás, pero todo el mundo deseaba avanzar en la dirección opuesta para poder contemplar los huesos del santo.

Lit. «She tried to go back with the hope of open a way among the bodies behind her, but everyone wished to advance in the opposite direction to contemplate the bones of the saint.»

20. Keeping her face turned away from him, she pushed past him, heading toward the back of the crowd.

La niña pasó por su lado en dirección al fondo, con el rostro vuelto hacia un lado.

Lit. «The girl passed by his side in direction towards the back, with the face turned away.»

1 The reader should note that there are manner of motion verbs in English which involve low degree of dinamicity, such as trudge or shuffle. Despite this, these manner verbs contribute to provide motion descriptions which are centred on the action itself in contrast to motion descriptions which focus on the result or endpoint of motion by means of the use of path verbs as it is generally the case in Spanish.

2 See also Ibarretxe-Antuñano (2006) for a summary list of the fine-grained manner categories which have been proposed for the semantic analysis of motion verbs.

3 For a more detailed review see Cifuentes-Férez (2009: 60-64) and Filipović & Ibarretxe-Antuñano (2015).

4 The interested reader can consult Loftus & Palmer (1974), one of the first studies which provide evidence for the influence of verb choice in the recalled memory of a video in which two cars ran into each other. After viewing the video, participants estimated a higher speed for the cars when the recollection was probed with a question which contained the verb to smash as opposed to the verbs to collide, to bump, to hit or to contact.

5 This experiment is based on a pilot study carried out by the author of this paper.

6 According to Cifuentes-Férez (2009: 110), «step seems to refer to the action of moving by lifting your foot or feet and setting it/them down again, that is, to go on foot or to walk […]; thus, step might be said to be more general in meaning than trample, stamp and tread.»

7 This verb belongs to Levin’s (1993: 270) accompany verbs and to verbs conflating Motion + Figure + Co-Motion (Cifuentes-Férez, 2009:109).