Translating non-standard forms of reported discourse in children’s books: Den tredje grottans hemlighet by Swedish author P. O. Enquist in French and German as a case in point

Carina Gossas

Dalarna University

Ulf Norberg

Stockholm University

The imitation of character voices and the relationship between narrator and characters are known to be fruitful domains for authors’ creativity and expressivity and thus constitute an intriguing translation problem that lacks clear solutions. In this study, we examine the translating of non-standard forms of reported discourse as distinct representations of voices in the French and German translations of the second children’s book by the Swedish author P.O. Enquist Den tredje grottans hemlighet, 2010 (“The Secret of the Third Cave”). We set out to analyze the translations of two stylistic features of this text: the use of hybrid forms of direct and indirect speech and the use of italics to mark a cited discourse.

key words: translation of children’s literature, P.O. Enquist, voices in translation, non-standard reported speech

Traducir formas no canónicas del discurso indirecto en libros para niños: Den tredje grottans hemlighet del autor sueco P.O. Enquist al francés y al alemán como estudio de caso

La imitación de las voces de los personajes así como la relación entre el narrador y los personajes son fecundas fuentes para la creatividad y la expresividad de los autores y hacen que el traductor se enfrente a problemas de traducción que no tienen soluciones muy obvias. El objetivo del presente trabajo es comparar las traducciones francesa y alemana de las formas no canónicas del discurso indirecto del segundo libro para niños del autor sueco P.O. Enquist Den tredje grottans hemlighet (El secreto de la tercera cueva, en español). Analizamos aquí la traducción de dos rasgos estilísticos de este texto: las formas mixtas del discurso directo e indirecto y el uso de cursivas para marcar un discurso citado.

palabras clave: traducción de literatura para los niños, P.O. Enquist, voces en traducción, discurso indirecto

Introduction

It has been pointed out that in children’s literature «[f]ictional dialogue is the appropriate place for evoking everyday speech, lending authenticity and credibility to the narrated plot and giving a voice to fictitious characters» (Brumme, 2012: 8). Although characters’ voices are mainly represented in dialogues, they can also be heard in other parts of the literary text, where the protagonists’ speech is accounted for indirectly by a verbum dicendi, or when the author depicts events from the perspective of a protagonist. The latter can involve, for example, applying free indirect discourse, or focalizing. Characters’ voices are usually important for the literary form, the progress of the plot and the characterization.

In translated children’s literature, the voice of the translator, in narratological terms the implied translator, is added (cf. Alvstad, 2013). As O’Sullivan (2003, 2005) claims, this is particularly tangible here «due to the asymmetrical communication in and around children’s literature» (2005: 1). One area in which the voice of the (implied) translator is often clearly heard is when the original uses non-standard forms of reported discourse (cf., for adult literature, Folkart, 1991, Taivalkoski-Shilov, 2006, 2010, 2013). In this article we examine this narrative device in a children’s book written by a highly acknowledged author of adult literature, who has recently crossed over to children’s literature, using non-standard language. We believe that this is a particularly interesting context from a translational point of view. Our observations take the starting point from the claims of Descriptive Translation Studies (see Toury 1995/2012) in which translation is seen as a norm-governed activity, which should be studied in the context of the needs and expectations of the target culture. The basic assumption is that any translator is called upon to make an overall choice between two extreme orientations: subjecting themselves primary either to the norms realized in the source text thus aiming at adequacy of the target text, or to the prevailing norm of the target culture, thus aiming at the translation’s acceptability whether as a target language text in general, or, more narrowly, as a translation into that language (Toury 1995/2012: 79). Indeed, as has been pointed out for instance by Nières-Chevrel (2008: 29f) for the French market, the norms regulating the translation of children’s literature permit more important deviations from the original than do the norms of adequacy that can be observed in the translation of general literature written for an adult audience. The empirical departure point for the study is the international trend, during recent years, of authors of adult literature starting to write for children; editors encourage their authors to address the younger public, as they perceive there to be a market both at home and abroad (Beckett 2009: 163-171). Following Becket, we use the term crossover writer to talk about an established author of literature for adults who take up writing for children. In the case of crossover writers, their status as renowned high prestige authors could result in less adaptation to the target norms. Alternatively, the norms applying for children’s literature could still prevail. To our knowledge there is hitherto no research on the question regarding translations into French and German.

We have found a rich material for a comparative investigation of this issue in the children’s book Den tredje grottans hemlighet (2010; from now on abridged as TGH) by Swedish author P. O. Enquist (born 1934). Enquist is a world-renowned author of adult literature who has since the 1960s published a large number of novels, including Musikanternas uttåg (1978; The March of the Musicians), Livläkarens besök (1999; The Visit of the Royal Physician) and Boken om Blanche och Marie (2004; The Book about Blanche and Marie). He has also written plays, such as Tribadernas natt (1975; The Night of the Tribades). His works have been translated into a large number of languages.

TGH is the second children’s book published by Enquist, who thereby has joined the crossover trend.1 It is a continuation of De tre grottornas berg (from here on abridged as TGB) from 2003, a chapter book about a grandfather and his grandchildren undertaking an expedition up in the mountains, where they experience a number of unlikely incidents. The first children’s book was translated into 22 languages, among them major languages such as English (Three Cave Mountain, or: Grandfather and the Wolves), Spanish (La montaña de las tres cuevas), French (Grand-père et les loups), and German (Großvater und die Wölfe). The same translator, Wolfgang Butt, has translated the two books into German. Butt is a renowned literary translator, who has translated many of Enquist’s books for adults. Different translators, on the other hand, have produced the French versions. The first book was translated by Agneta Ségol and the second by Marianne Ségol-Samoy & Karin Serres. Agneta Ségol has been one of the most productive translators of Swedish children’s literature into French, and her daughter Marianne has gone in her footsteps; with a special interest in theatre she has also translated Swedish plays into French. The German translation appeared in a highly regarded publishing house, Hanser, as did the French version, namely in La joie de lire, a small publishing house in Geneva specializes in children’s literature of high quality.2

In a previous publication (Gossas & Norberg, 2012), we discussed with regard to the French and German translations of TGB different ways of rendering speech in translation. We distinguished between a number of formal categories of rendered speech, all contributing to the polyphonic structure of the text. These are: direct speech, supposedly a mimetic copy of the utterance and normally marked with a dash or a quotation mark, indirect speech, integrated into the narration and formally marked by a speech act verb and a subordinator — this canonically comes with transpositions of tense and personal pronouns — and free indirect speech, in which linguistic elements in the context make it plausible to assume that words or thoughts should be ascribed to an enunciator different from the narrator.

We observed a shift towards a more monophonic structure in both translations, even though the German version was considerably closer to the original’s heteroglossia in many respects. More precisely we observed that the mimetic style in direct speech was more easily transposed into the translations, compared to the mimesis appearing through the polyphonic structure of the narrating sequences. In the case studied, this might have been due to the fact that the narrator’s mimesis of «child language» collides with the standards of literary discourse in the target cultures.

The aim of this article is to further investigate the translation of cited discourse in the specific type of crossover fiction in which a highly esteemed adult author writes for a young audience. We set out to investigate how translators respond to situations in which a secondary discourse is integrated into the primary discourse, either through the use of hybrid forms of direct and indirect speech (in order to, for example, enhance the expressivity of the literary text), or through the use of italics citing one of the protagonists. In doing so, we will also touch upon how translators respond when the voices of different characters imitate each other, in this case often for a humorous effect. Our hypothesis is that both translations will standardize some of the deviant language characterizing the source text, since this has long been pointed out to be a general or even universal feature of translation (see, for example, Toury, 1995: 267f, Laviosa-Braithwaite, 1998: 289f), but that the extent of the standardizations will probably not be the same in both languages.

In section 2, a presentation is made of TGH and its French and German translations, in order to provide a wider context for the translation shifts that are discussed. Section 3 presents a theoretical background of the issues of voices in translation. The analysis of the two translations follows in section 4. In section 5, some concluding remarks are made.

Presentation of den tredje grottans hemlighet (TGH) and its translations into French and German

TGH has many similarities with its predecessor (TGB), both being humorous adventure books that take place in a rural area of Sweden of today. Both characters and surroundings are presumed to be real. This can, of course, be explained by the fact that the story was originally written for the author’s grandchildren. It could also be observed that the book borders on the documentary trend in Swedish children’s literature that was pointed out by The Swedish Institute for Children’s Books (SBI) in their yearly documentation of Swedish children’s literature for the year 2003, when TGB appeared. The main protagonists are a grandfather and some of his grandchildren. The grandfather is the fictional representation of the author himself and the illustrations in the Swedish originals greatly resemble the author. The grandfather is mainly called «grandfather», but in TGH the grandchildren Gabriel and Moa also use «P.O.» (TGH, p. 98 and p. 119) and adults who do not know him personally call him «Enquist» (for example, p. 120). The children also bear the names of the real grandchildren of the author, as he points out in the radio interview from 2010. It is stated explicitly in TGH that the main events take place three years after those of the first book (which are often referred to), specifically on some particular dates in the summer of 2006. In the second book, the grandchildren have thus become some years older, and the book is addressed to somewhat older children (9-12 years of age). Consequently, the imitation of voices has also undergone some changes, as will be discussed below.

TGH can be seen as a character-oriented, classical but slow-moving adventure story with a fairly long introduction, including the death of the dog Mischa and the start of the expedition at a summer house in West Sweden, where a number of mysterious incidents take place. These include finding an abandoned hidden tent in the woods, mysterious policemen, the finding of a Lithuanian book (a translation of TGB,3 including a map of the area in question), and a threatening nighttime phone call. There is a climax in which the grandfather and his grandchildren, the latter equipped with a stolen gun (a Kalashnikov), defeat some Russian smugglers around the «third cave» (hence the name of the book) with the help of different animals (not least a bear destroying the criminals’ helicopter), and finally a solution section at the end, in which a mother wolf is buried, a reference back to the beginning of the book.

Death and ageing are central themes in the book, for example, with episodes of the deaths of animals both starting and ending the book, by the foregrounding of the grandfather’s poor health, and the expression ånga upp (steam up) repeated a number of times (p. 23, 34, 48, 127, 128, 173), indicating the grandfather’s view on the philosophical question of what happens after death. Didactic elements are quite frequent, through the grandfather’s explanations that come repeatedly, as well as through the highlighting of the importance and pleasure of language.

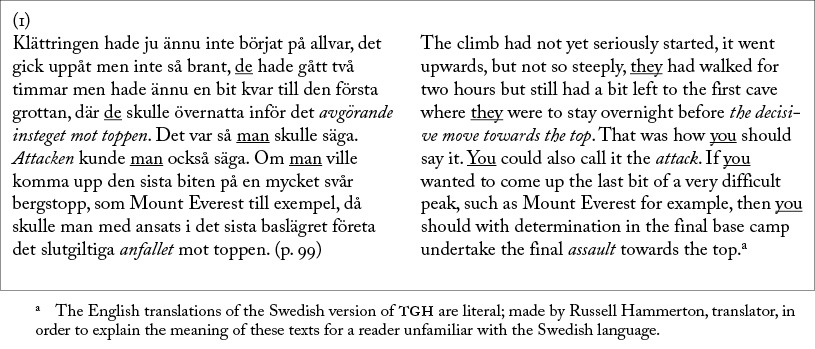

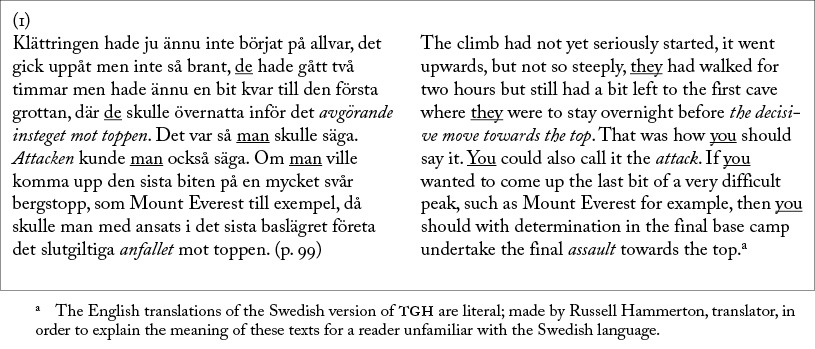

TGH is a book in which the story is constructed by the dialogue between the voices of the different characters. By letting the characters’ voices be heard in the book, the author can present the story from the perspectives of these different characters. It is to a large extent through the style of language that the relationship between the generations is revealed in the book. The grandfather has a specific language that the children repeatedly relate to. Whereas in TGB the children’s voices were present in the narrator’s voice, in TGH the presence of the grandfather’s voice in the narrator’s voice is more prominent. Grandfather can be said to have both a «poetic» and an «exact» discourse, and the narrator repeatedly reports both. Renderings of these discourses are often marked graphically in italics,4 as in example (1)5 illustrating the «exact» discourse of the grandfather. The protagonists are on their way up to the cave to investigate why the wolf seems to be howling. The narrator describes their way up. In the middle of the example, there is a shift from external focalization by the use of the third person plural pronoun (de ‘they’) into internal focalization marked by the impersonal pronoun man (‘one’).6 In the example, the second sentence and those following contain a metalinguistic reflection of the expressions that should be used in order to properly describe the last part of the ascension. The expressions are marked by italics, and it is rather obvious from the context that this discourse can be ascribed to the grandfather, as it uses a rather military register (insteg ‘move’,7 attack ‘attack’, anfall ‘assault’).

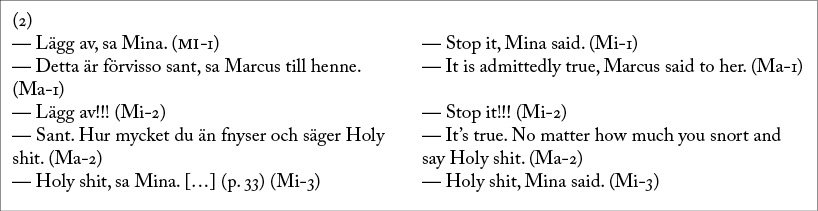

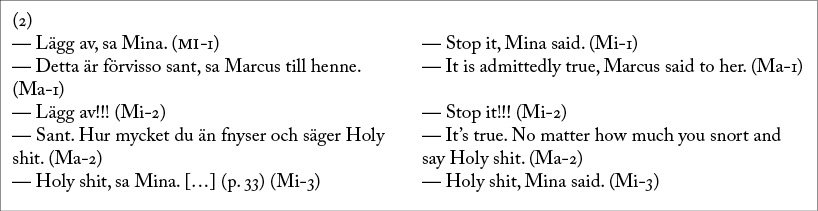

The children seem keen to adopt the somewhat specific language of their grandfather, which has different traits from theirs, being both old-fashioned and poetic. The following example (2) illustrates the stylistic variation that appears throughout the book. In the second line, Marcus makes use of the old and formal adverbial expression förvisso (‘admittedly’) in the phrase Detta är förvisso sant (‘This is admittedly true’) (Ma-1), which contrasts with his second more spontaneous intervention Sant. (‘True.’) (Ma-2), as well as the tone of Mina in her first and third lines (Mi-1, Mi-3).

The peritext (i.e., the paratext surrounding the literary text on and in the book itself, see Genette, 1987) differs considerably between the three versions. In both translations, the titles are changed considerably. The French version is called La montagne aux trois grottes Three mountain caves, a rather literal translation of the title of the first book, thereby breaking with the foregrounding of the (famous) grandfather in the title of the first book (in French it was called Grand-père et les loups Grandfather and the wolves). The German version continues its aim of putting the grandfather in the foreground, as he was in TGB (called Großvater und die Wölfe Grandfather and the wolves), calling this Großvater und die Schmuggler (Grandfather and the smugglers). The illustrations in TGH are considerably more «adult-like» than those in the first book. The German version contains drawings by the same (German) illustrator as the first book, Leonard Erlbruch. The French version has the same cover picture as the German, but no pictures in the book itself.

The cover texts also differ considerably. The Swedish version does not mention comments on the book by professionals (i.e., reviews). However, on the back cover, it acknowledges the fact that the first book was translated into 22 languages and received a prize for best children’s book of the year in Germany. The French version refers to the author as «le grand écrivain suédois» (Engl. ‘the big Swedish author’) and continues by saying that he tells the story of a grandfather that every child would dream of having (the same phrase is used on both covers). The German version refers to the terrific adventures of the first book and hints that they are even surpassed here, all in a language spiced with child-like words. It is complemented by an enthusiastic review of the first book, the reference to it ending with the words «des großen schwedischen Schriftstellers» (Engl. ‘of the big Swedish author’).

Concerning the reception of the book in the Swedish market, it was, to say the least, lukewarm. Some reviewers were of the opinion that the book addressed adults too much and that neither the style nor the humour would be well received by children (Per Israelsson in Svenska Dagbladet [Nov. 2, 2010], Malin Lindroth in Göteborgs-Posten [Oct. 27, 2010]).8 In his review, the highly acclaimed children’s book author Ulf Stark compared the styles of Enquist as an adults’ and children’s book author, and pointed out that the precise tone of the adults’ author is missing here. He comments critically on «strange italicizing, words and repetitions» (Stark, 2010),9 which according to him do not characterize Enquist’s style when he writes for adults. Even if Stark finds it praiseworthy that authors normally writing for adults change target group, he does not find this a successful example, «whatever the critics in Germany might say».10

In French-speaking countries, we have been able to find only a few book reviews. Ricochet, the Internet site of the Swiss institute for children’s books, which guides readers in the vast area of newly released children’s literature in French, considered the book to be especially well worth reading, since they presented it under the title of «Notre sélection 2011». In their review, the narration was described as «abundant and euphoric» and attention was drawn to the successful depicting of realistic characters; each child displaying its own personality, and the grandfather being both wise and foolhardy. In German-speaking countries, the second book was also very well received. Reviewers emphasized the verbal imaginativeness of the book (Christine Lötscher in Buch & Maus, 2011), stating that «childish and old-fashioned language harmonize well with each other» here, and that the fact that the narrator perpetually changes position provides variation, sometimes being close to the grandfather and sometimes close to the grandchild Marcus (Anna Wegelin in Die Wochenzeitung, [April 14, 2011]). Interestingly, it received a children’s book prize in Switzerland (Pro Senectute Schweiz, Prix Chronos) that highlights the theme of age and relations between generations with the motivation that «Enquist’s second children’s book amazes with its playful language, the self-ironic language of the grandfather and its narrative skills» (2012).

Theoretical background

The narration in a novel is the result of an act of enunciation by what we will call a primary speaker, the narrator, which generally includes other acts of communication in the text accomplished by what we call a secondary speaker. In this article, we do not intend to hold a narratological discussion about the status or types of narrators, but instead we will take a linguistic perspective. Following the enunciative framework of modern linguistics represented, for instance, by Laurence Rosier (2008) and Alain Rabatel (2009), and of textual linguistics, represented, for instance, by Jean-Michel Adam (2008), we acknowledge the dialogical nature inherent in the language system and the fact that mediating discourse is not confined to literary discourse, even though it has its special function within this discourse.

The use of character-oriented discourse in a children’s book has various functions, for instance, leading the plot forward and giving body and shape to the characters (see Nikolajeva, 2002: 223-240). The interplay of voices gives the text a polyphonic structure, in which the voices of the narrator, and those of different characters with their social and individual variations, are given expression and form.

As mentioned above, we are interested here in the interaction between direct and indirect speech. The alternation of direct and indirect discourse is most often a question of rhythm and variation (Nikolajeva, 2002: 229). This alternation is not uncomplicated in TGH, especially not from the point of view of the translator.

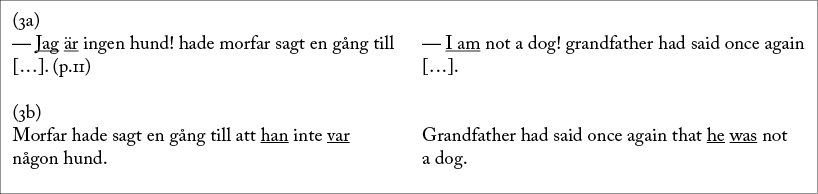

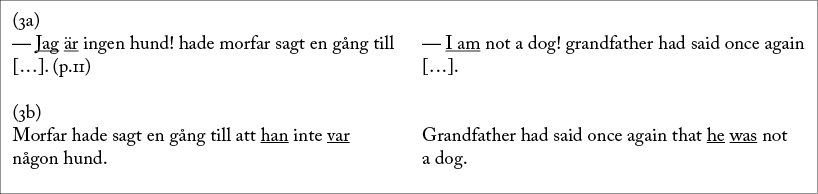

The different types of mediation of a secondary discourse establish a tension between the discursive continuity of the narration and the discontinuity automatically generated by the citations (Adam, 2008: 75). Whereas direct speech leads to a discontinuity by the explicit rendering of the words of a secondary enunciator, indirect speech tends somewhat towards homogeneity by transforming the deictic elements of the utterance. Direct speech, thus a supposedly true copy of the utterance,11 is also canonically clearly separated from the body of the text with a dash or quotation marks that reflects the discursive discontinuity. A typical example (3a) of direct speech in TGH illustrates this.

We can observe that the quote here is marked by several formal means: new line, dash, capital letter, exclamation mark and a following verbum dicendi. A transformed sentence, canonical for indirect speech, would be example 3b.

In this referential sentence, the personal pronoun and the tense are changed (deictic expressions would also have been changed if there had been any), a subordinator is added, but neither a dash, a capital letter, nor an exclamation mark are used. It is noteworthy here that the standard for rendering both direct and indirect speech for all the three languages involved here –French, German, Swedish– is more or less the same; only the use of dash vs. quotation marks, and, concerning the latter, the appearance of the quotation marks differs between them.

As demonstrated by Rosier (2008: 52f), it is possible to distinguish between several mixed forms in which some traits of the direct discourse are present in the construction of an instance of indirect speech (third person pronoun, past tense), or vice versa. For instance, the subordinated secondary utterance can maintain mimetic elements proper to the utterance situation. It is thus not justified to postulate a necessary correlation between the grade of mimesis and the type of cited discourse. It is also possible to encounter an instance of indirect speech which maintains the deictic forms proper to the enunciation of the reported discourse, but which is nevertheless introduced by a subordinator that thus works in the direction of syntactic integration within the primary discourse. As a matter of fact, Rosier (2008: 53) mentions four types of direct speech (here translated into English):

- Canonical form: He did not stop saying: «My illness is haunting me!»

- Direct speech with subordinator: He did not stop saying that «my illness is haunting me!»

- Direct speech typographically emancipated: He did not stop saying my illness is haunting me!

- Free direct discourse:12 He looked at her. My illness is haunting me.

According to the norms, the secondary discourse in (a) appears with the tense and the pronoun proper to the situation of the utterance. However, in (b) a subordinator proper to the direct speech appears. In (c), the graphical marking separating the primary and the secondary discourses is omitted. In (d), only the tense and the pronoun formally indicate the discursive discontinuity. The contextual clue for an interpretation of discursive discontinuity can also be found in the perception verb in the previous sentence. As Rosier stresses, these examples only illustrate the fact that we can organize the different forms of reported speech on a continuum, and that there exist hybrid forms. This is thus not to be understood as an exhaustive list of possibilities.

Rosier (2008: 53) likewise proposes four types of indirect speech:

- Canonical form: He did not stop saying that his illnes was haunting him.

- With interpolated clause: His illness was haunting him, he did not stop repeating.

- Mimetic: He did not stop saying that «his illness was haunting him!».

- Without subordinator: He did not stop saying «his illness was haunting him!»

The forms b-d all deviate in different ways from the canonical case illustrated in (a), but still maintain the past tense and the third person pronoun. However, in (c) and (d) some characteristics from the utterance situation are added. In both, there is an exclamation mark proper to the secondary discourse, and the dashes mark mimesis. In (d), the syntactic marker of subordination has been omitted.

As seen above, the discursive discontinuity in the rendering of direct speech is marked in the canonical case by a number of formal means. However, as Rosier (2008) shows concerning written French, the formal marking can be totally eliminated without this essentially affecting the interpretation. The reader will also identify the cited expression without any formal means at all. Following Rosier (2008: 55), we finally postulate that for reported discourse, there is always a tension between the over-marking and the erasure of the citing discourse. In this article, we use the term «overmarking» when several formal means concur in the marking of the enunciative status of an expression. This makes it possible to compare the degree of formal marking in terms of the relative over- and under-marking between the versions of the book, as well as differences with regards to the formal devices that are used.

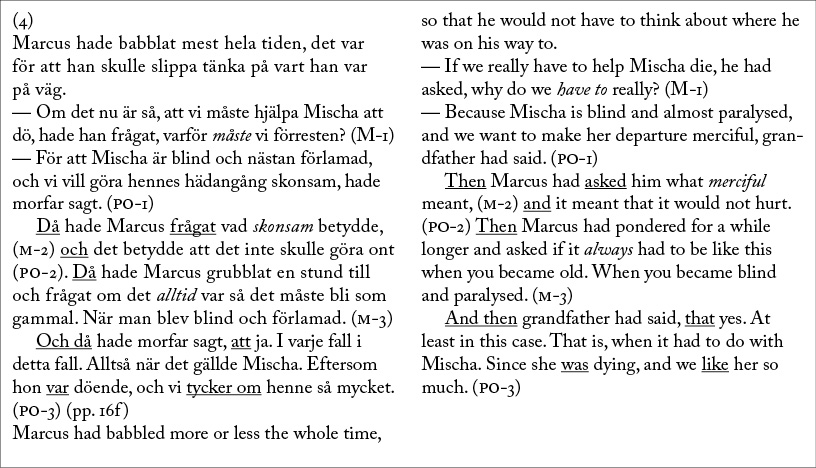

In TGH, there are many instances of hybrid forms in which, for example, instances of direct speech do not receive all the markers shown above and in which instances of indirect speech are integrated more or less in the primary utterance. Let us look at an example of how different types of formal means interact in the rendering of the mediated discourses. In (4), below, we see an interaction between Marcus and his grandfather that takes place in the car on the way to the veterinary clinic. The first two turns (M-1 = Marcus’s first turn; PO-1=grandfather’s first turn) are mediated through canonical direct discourse (dash, first person, question mark in M-1). The following turns (M-2 and PO-2) are mediated through indirect discourse (past tense) and integrated within the same sentence. Thus, only M-2 is introduced by a speech verb (fråga ‘ask’) mentioning explicitly who is speaking. For turn PO-2, there is no such indication. The next turn of Marcus’s (M-3) directly follows in the same paragraph, whereas PO-3 (composed of four sentences) comes in a new paragraph. Here, we find a less canonical rendering, as we simultaneously have a subordinator (att ‘to’) and the past tense (var ‘was’), which alternates with the present tense (tycker om ‘like’).13

The temporal logic used here (underlined above: Då ‘then’, och ‘and’, Då ‘then’, Och då ‘and then’) lends both a child’s perspective and oral characteristics to the narration. This is also an example of grandfather using a rather «adult language» (PO-1: hädangång ‘passing’), and illustrates the way in which grandfather usually explains words for the children (PO-1: skonsam ‘merciful’).

In the following section, we will discuss the translation of what we could call hybrid forms of reported speech, in which the author in the same sequence uses both traits belonging canonically to direct speech and traits typical of the expression of indirect speech. Formal categories (tense, pronouns and punctuation marks) are used here in a non-canonical way. These blurred forms are interesting from the perspective of translation, not least since they are instances for which there probably very seldom exist strong translation norms. We will also discuss the translation of italicized expressions where the typography indicates a cited discourse.

Translation analysis

In many (but not all) aspects, the French version diverges more from the Swedish original than does the German version, which has repercussions for the voices of the protagonists. Consequently, the French translation normalizes hybrid forms of direct speech – recurrently forming a clear distinction between primary and secondary discourse, which is marked graphically (by a new line, a dash, or a colon). A possible reason for this could be the mission of children’s literature to teach reading; the text should be easy to read.14

The German translation respects many more non-standard traits of reported discourse than does the French one, without being a totally servile one. However, missing quotation marks in the source text are most often inserted, as well as colons. The non-canonical use of italics as signs for speech is sometimes removed in the German version. It is noticeable that it has long been claimed in translation studies that punctuation is among the cases in which translators tend to standardize to a large extent (see, for example, Vanderauwera, 1985). The strong norm might be due to the issue being closely connected with opinions about «good» and «bad» language.

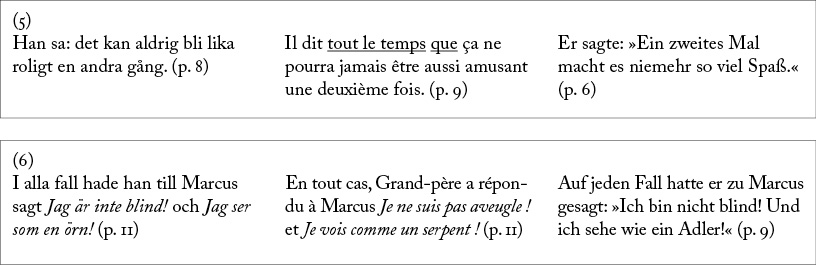

In the following, we first discuss forms relatively close to standardized direct speech, and then continue with more non-canonical ones. Let us first consider an example in which both translations have undergone standardizations, each one opting for different solutions. In example (5), the secondary discourse (det kan aldrig bli lika roligt en andra gång ‘it can never be as funny a second time’) is only separated from the primary discourse with a colon after the speech verb. The simple use of a colon to mark the separation between the two discourse levels can be described as a relative under-marking of this distinction. In a more standardized form, the mediated discourse would have been introduced by a capital letter, and possibly surrounded by quotation marks.15 The sequence appears at the very beginning of the book; the children want to return to the mountains, but the grandfather is, surprisingly, the one who blocks a new expedition. It is worth mentioning that the context actually points towards an iterative interpretation of the sentence; the grandfather repeatedly refuses to embark on a new expedition because he assumes that it could not be as fun as the first time. The iterative interpretation might possibly explain the use of this non-standardized form.

The French version chooses to standardize into indirect speech introduced by the subordinator que, whereas the German version chooses to standardize the direct speech, with a colon, quotation marks, a capital letter and a full stop in the secondary discourse, which – it could be argued – together makes the iterative interpretation much less plausible. Both procedures mirror a recurrent pattern throughout the respective translations. The French version, on the other hand, adds the adverbial tout le temps (‘always’), thus explicating an iterative interpretation of the utterance.

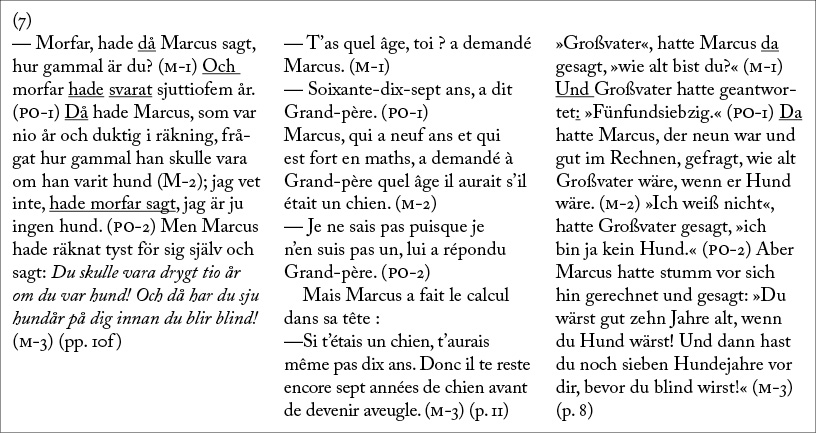

In example (6), there are two reported utterances by grandfather that attract our attention (Jag är inte blind! ‘I am not blind!’, Jag ser som en örn! ‘I see like an eagle!’). These two instances of direct speech (present tense, first person) are both marked by capital letters, italics, and exclamation marks, but lack other graphical markers such as colons, dashes or new lines, which contributes to a faster rhythm of reading.

In this case, it is the French version that follows the original’s non-canonical uses, whereas these are normalized in the German version, in the second repartee of which, in addition, the conjunction «Und» is integrated into the reported utterances.

The interaction in (7) shows a mix of different ways to mark cited discourse. The example shows clearly how a faster rhythm of reading is created in Enquist’s text by the use of a number of different non-canonical means. For instance, several turns are woven together by leaving out new lines, colons, dashes and quotation marks, but instead adding italics; the latter helping the reader to identify cited discourse and not become lost in the reading (cf. Cadera, 2011: 40f). The example starts with a repartee with a dash, introducing a question by Marcus to his grandfather (M-1). The grandfather’s response (PO-1) is reported within the same paragraph and only marked by a speech verb (hade svarat ‘had answered’), this time coming before the reported utterance. The second question asked by Marcus (M-2) follows again within the same paragraph, but this time in the form of an indirect question. The emotional enhancement is then reflected in the punctuation and reading rhythm, as the response (PO-2) comes immediately after a semicolon, intersected with an interpolated clause (hade morfar sagt ‘had grandfather said’). The paragraph ends by an emphasized repartee by Marcus in italics after a colon, but without a dash or quotation marks (M-3).

The French version clearly separates the voices of the different characters (M-1, PO-1, M-2- PO-2) by the use of dashes and new lines (a line break for the indirect question in M-2), privileging clarity and readability. The German version, on the contrary, mainly follows the original when it comes to the structure of the interaction, but adds a colon and quotation marks in PO-1, separates M-2 and PO-2 by a full stop, and also adds quotation marks in PO-2. It finally introduces quotation marks and takes away the italics in M-3.

The restructuring in the French version entails the omissions of the connective markers of colloquial style in the opening two sentences (då ‘then’, Och ‘and’, Då ‘then’; underlined above). However, the repartees in general are rendered in a colloquial tone, reflected, for instance, in the use of the contracted form imitating orality (T’as < Tu as ‘you have’). Once again, we observe that the German version keeps more of the norm-breaks than does the French one, but standardizes some. The addition of quotation marks is particularly recurrent in the German version. By not using a new line in order to separate the turns, the German version can also easily maintain the connective markers.

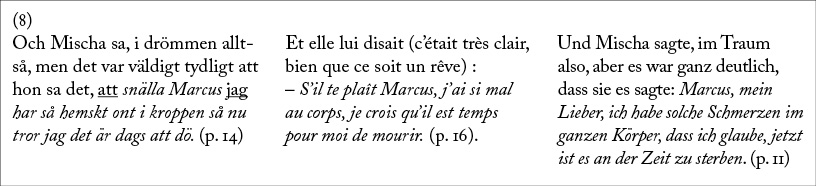

In example (8), an instance of blurred direct speech by the dog (snälla Marcus jag har så hemskt ont i kroppen så nu tror jag att det är dags att dö ‘please Marcus, my body hurts terribly so now I think it’s time to die) is syntactically integrated into the primary discourse by the use of the subordinator att (‘that’).16 The use of the present tense, the first person pronoun (jag ‘I’), and presumably also the use of italics, advocate the interpretation of direct citation, in spite of the subordinator directly ahead, and no use of a colon, a dash, a new line or a capital letter.

None of the translators respected this typographically. In both translations, the restructuring leads to a clear indication of direct speech (colon), in the French version also with a dash. Yet, they both keep the italics, perhaps because of the highly expressive content (a declaration of pain and death) and the unusual speaker (the dog).

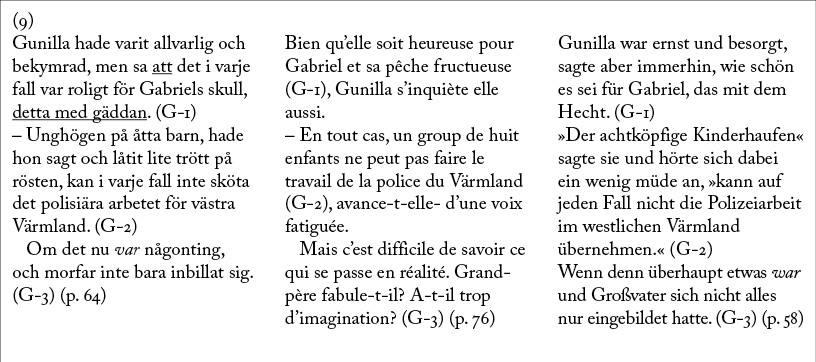

In example (9), we see that different utterances within a turn can be reported differently. Indeed, the contribution of grandfather’s wife Gunilla is cited in three different ways. The first utterance (G-1) is integrated syntactically within the primary discourse by the subordinator att (‘that’) but has a clear mimetic character through the right-dislocation detta med gäddan (‘this about the pike’), which helps evoking the feeling in the reader of having direct access to Gunilla’s formulations. The second utterance (G-2) is rendered by the standard form of direct speech, whereas the third case (G-3) could probably best be interpreted as an example of free indirect discourse. This interpretation is enhanced by the italics of the verb var (‘was’), which marks a specific intonation. (G-3 is also situated at the end of a whole section.)

The French version transforms the item of indirect speech (G-1) to a description of Gunilla’s mood (Bien qu’elle soit heureuse pour Gabriel et sa pêche fructueuse ‘Although she is happy for Gabriel and his success in fishing’), whereas the German version keeps close to the source text. G-2 has the same structure in the three versions, just with a tense change in the translations, from the pluperfect tense into the present tense in the French version, and the preterit tense in the German one. In G-3, the French version reduces the voice ambiguity; only the narrator’s voice is heard. The German version once again stays closer to the original, since Gunilla’s voice is clearly heard here.

As already mentioned above, the use of italics contributes essentially to the expression of the protagonists’ voices in TGH. Italics can, of course, have many functions, and as indicated above they are particularly abundant in TGH. In some cases, italics simply mark the special intonation of an element in the cited discourse, as can be seen above in (4), where the modal adverb måste (‘must’) is in italics. Additionally, they can function as quotation marks, as in (6) and (8). In the following example, (10), an additional function is illustrated, namely to literally cite a certain word or a phrase within the primary narrator’s discourse.

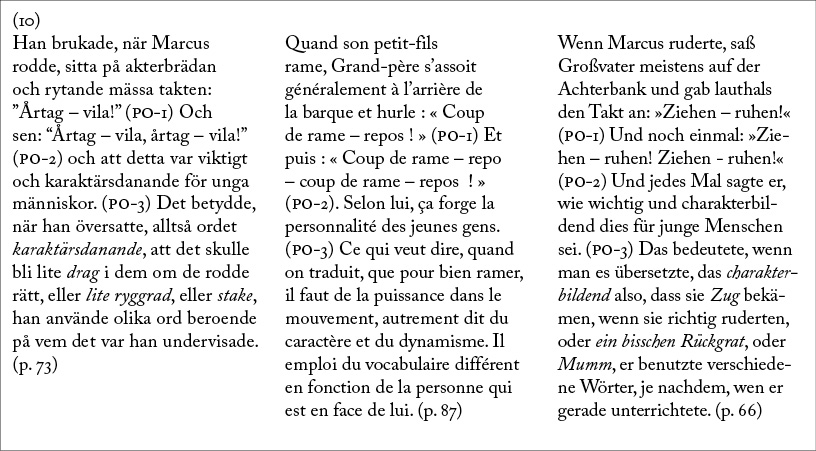

The example opens with a description of grandfather shouting in the boat in order to help the children maintain a good cadence while rowing. Two interventions in indirect speech (PO-1, PO-2), as well as one intervention in indirect speech (PO-3), are rendered in the two first sentences. The speech verb mässa (‘chant’) mentioned in the second line extends to all of these instances. Then, the narrator reports three explanative reformulations of the word karaktärsdanande (‘character-forming’). The narrator tells us that grandfather uses different conventional metaphorical expressions depending on the person he addresses (drag ‘energy’, ryggrad ‘spine’, stake ‘pole’). The use of italics and the expressivity naturally lead the reader to consider this as a faithful citation. The narrator also says that this is the way that grandfather översatte (‘translated’) the expression used. This rather humorous and self-ironic way of explaining appears to be a stylistic feature of TGH, and a way to combine a child and an adult perspective.

The French translation here undertakes some standardization both on the formal and lexical levels. A frame adverbial (selon lui ‘according to him’) is added in PO-3 that also starts a new sentence. The italics disappear and the personal pronoun han (‘he’) is replaced by the impersonal on (‘you’). The explanation thus moves away from the character of the grandfather and the citation function is lost, as well as its characterizing function. However, the last sentence in the example (an asyndetic construction in the original) states that this is how grandfather used different expressions. It is finally worth mentioning that the sequence alltså ordet karaktärsdanande (‘that is the word character-forming’) is omitted. The German translation makes the same change from personal to impersonal pronoun (man ‘you’), but maintains the italics and their citing function.

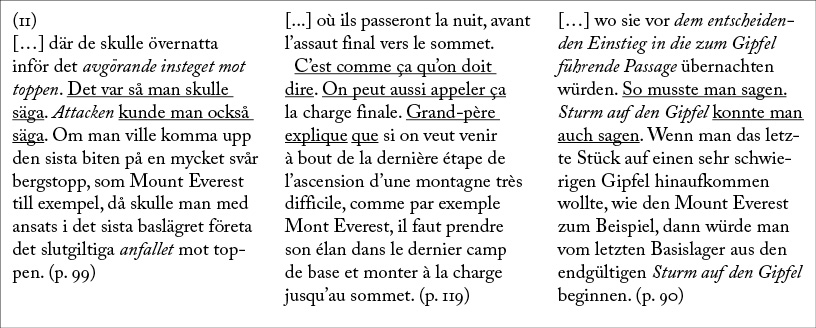

Another example where the French translation has omitted the italics, whereas they are maintained in the German version, can be seen in (11).17 Here, the tone is more serene. The protagonists are in a dangerous and crucial situation as they intend to climb to the top. Grandfather has explained how to do this. The rendering of this is from the children’s perspective (by the use of the impersonal pronoun man ‘you’). In the original, there is no explicit mentioning of grandfather as being responsible for the explanation, but the stylistic level and the italics constitute strong contextual cues leading to this interpretation. Once again we are dealing with three reformulations (avgörande insteget mot toppen ‘the decisive move towards the top’, attacken ‘the attack’, anfallet ‘the assault’).

It is worth noticing that the omission of the italics in the French version correlates with the addition of a speech verb (grand-père explique ‘grandfather explains’) that explicitly ascribes the explanation to the grandfather.

In (12), we see again that the standardization of the typography goes hand in hand with a syntactic standardization, as well as with normalization at the level of enunciation. This time, the three varied formulations are about a word play. Grandfather firstly uses the comical and childlike expression ta ihop sig (‘take oneself together’), which is a distortion of the standard expression ta sig samman (‘put oneself together’) where the two verb particles ihop and samman (‘together’) have the same concrete denotation, but are not in this case interchangeable. The last variant bemanna sig (‘nerve oneself, embolden oneself’) has military connotations and is very unusual, but is an expression also often appearing in Enquist’s writings for adults (so is the use of italics).

In the French version the mimetic impression is less articulated, not only as a result of the omission of the italics, but also, and perhaps even more so, because of the omission of the deictic time adverb nu (‘now’), the clause adverb faktiskt (‘indeed’) and the first two exclamation marks. The connective men ‘but’ is also omitted in French; the sequence instead starts with the time adverbial Soudain (‘suddenly’): Soudain, Grand-père a dit qu’il fallait qu’ils se ressaisissent. (‘suddenly grandfather said that they should pull themselves together’). Except for the presence of the exclamation mark found at the end of the sequence, the French version thus presents an indirect discourse according to the standards. It sacrifices the word-play by omitting one of the reformulations, but renders the vivid style of the original by the use of a completive in the second sentence that is governed by the verb in the first sentence and followed by an exclamation mark: Qu’ils prennent sur eux ! (‘That they make a special effort!). The humorous effect of the repetition of Eller: (‘Or:’) disappears in the French version. The German version’s only standardization is the taking away of the colons.

In (13), there is again a self-ironic tone in the two expressions that are marked by italics, which indicates that they are quotations. The underlying primary discourse acquires an iterative function through the long time adverbial at the end of the sentence (när han ville ha medkänsla och ihållande applåder från barnbarnen vid kvällens sagostund ‘when he wanted compassion and never-ending applauses from the grandchildren during the bedtime story’), as well as by the formula som han sa (‘as he said’).

This time the French translation maintains a part of the first italicized expression, but standardizes the rest. The fact that the italics are maintained here correlates with a restructuring of the subordinate clause som han sa (‘as he said’), which is translated as Grand-père aime raconter (‘grandfather loves to tell’) on a new line. The French version here presents an objective narrator. The German version keeps close to the original, but standardizes this into the pluperfect tense.

In our last example, (14), both the italicized adjectives (blanka och natursköna ‘blank and scenic’) and the explicit speech verb (han kallade ‘he called’) have been omitted in the French translation, whereas the preposition phrase indicating the location (à la surface de l’eau ‘on the surface of the water’) is left. As this citation echoes the verbal interaction between the protagonists, and points to the specific language used by the grandfather, it is also a characterizing device that is lost. In the German version, it is on the contrary kept.

Interestingly, what is being neutralized in the French version in this case is the adult voice of the grandfather (representing the author), and not the child’s language.18 This contributes to the neutralizing of stylistic shifts, which make up one of the stylistic features of the text, to the advantage of the coherence and the readability of the text.

Conclusion

A premise for this study was the fact that the characters’ voices are expressed by different linguistic forms (conveying different stylistic features according to the context) and that there normally is a variation between possible expressions within a text (for example for the sake of variation in rhythm or in order to indicate a certain relationship between the narrator and the characters, etc.). The exploration of different citing techniques can actually be placed at the very heart of literary development. As indicated in section 3, linguistic research has recently presented different models to capture the forms that deviate from prevailing norms prescribed by, for instance, normative grammars and reference guides for writing. We saw that the secondary discourse can be more or less formally and graphically separated from the primary discourse, and that several blurred forms of the traditional direct and indirect speech exist.

The aim of the study was to compare the French and German translations of non-standardized forms of reported speech in a children’s book where different forms of reported speech played an important role, not only for the plot, but also for the characterization of the protagonists. The hypothesis was that there would be standardization in both translations, since this has long been pointed out to be a general or even universal feature of translation. However, we also hypothesized that the limit of acceptability would not be the same in the two versions. The analysis showed that the hybrid forms were standardized to a high degree in both the French and German translations, but more in the French one. We proposed comparing the formal separation of direct discourse and narration in terms of relative over-marking. It is clear that both translations tend to use more graphical and formal markers to more clearly separate the two levels of enunciation. However, the German version nevertheless keeps more closely to the structure of the original. The German translation thus accepted more deviations from norms and standard language, but the punctuation norms were not transgressed. The italics (when used as a reporting device) were to a high extent omitted in the French version, but mainly maintained in the German version. As one of the functions of the italics was to give form and shape to one of the characters, namely the old author and grandfather – and thus indirectly to the relationship between him and the children – this dimension is also to a certain extent reduced in the French version.

These standardizations of non-canonical forms of rendered speech can have several possible explanations. As indicated above, concerns about teaching reading may have crossed the minds of the translators. It is a question of self-confidence, and how the translator thinks that they as translators will be judged as translators, if they reproduce deviant language . The important shifts that have been observed in the French version seem to indicate that this crossover author has been translated according to the prevailing norms of children’s literature, and not according to the norms of adequacy that we had assumed would be more dominant in the translation of a highly esteemed author such as Enquist.

RECIBIDO EN ENERO DE 2014

ACEPTADO EN MARZO DE 2014

VERSIÓN FINAL DE ENERO DE 2014

Primary sources

Enquist, P.O. (2010). Den tredje grottans hemlighet. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren.

—(2011). Großvater und die Schmuggler. (Translated by Wolfgang Butt.) München: Carl Hanser.

—(2011). La montagne aux trois grottes. (Translated by Marianne Ségol-Samoy & Karin Serres.) Genève: La joie de lire.

Reviews

Ekholm, S. «Per Olov Enquist: Den tredje grottans hemlighet». Dagens Nyheter, Nov. 9, 2010.

Israelson, P. «Enquists text griper aldrig tag». Svenska Dagbladet, Nov. 2, 2010.

Lindroth, M. «Per Olov Enquist: Den tredje grottans hemlighet». Göteborgs-Posten, Oct. 27, 2010.

Lötscher, C. «Grossvater und die Schmuggler». Buch & Maus, Heft 1, 2010.

Pro Senectute Schweiz, Prix Chronos «Per Olov Enquist: Grossvater und die Schmuggler».

Ricochet, Institut suisse Jeunesse et Média. <http://www.ricochet-jeunes.org/livres/livre/43195-la-montagne-aux-trois-grottes> (Accessed on Oct. 1, 2013).

Stark, U. «Per Olov Enquist: Den tredje grottans hemlighet». Expressen. Nov. 1, 2010.

Wegelin, A. «Drama auf dem Dreihöhlenberg». Die Wochenzeitung, April 14, 2010.

Secondary sources

Adam, J.-M. (2008/2005). La linguistique textuelle. Introduction à l’analyse textuelle des discours. Paris: Armand Colin.

Alvstad, C. (2013). «Voices in Translation». In Gambier, Y. & L. van Doorslaer (eds.). Handbook of Translation Studies. Volume 4. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 207-210.

Beckett, S.L. (2009). Crossover Fiction: Global and Historical Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

Brumme, J. (2012a). «Introduction». In Fischer, M. B. & M. Wirf Naro (eds.). Translating Fictional Dialogue for Children and Young People. Berlin: Frank &Timme, pp. 7-13.

Cadera, S. M. (2011). «Translating Fictional Dialogue in Novels». In Brumme, J. & A. Espunya (eds.). Translation of Fictive Dialogue. New York: Rodopi.

Enquist, P.O (2003). De tre grottornas berg. Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren.

—(2003). Großvater und die Wölfe. (Translated by Wolfgang Butt.) München: Hanser.

—(2005). La montaña de las tres cuevas. (Translated by Frida Sánchez Giménez.) Madrid: Siruela.

—(2007). Grand-père et les loups. (Translated by Agneta Ségol.) Genève: La Joie de lire.

Fischer, M. B. & M. Wirf Naro (eds.) (2012). Translating Fictional Dialogue for Children and Young People. Berlin: Frank & Timme.

Folkart, B. (1991). Le conflit des énonciations: traduction et discours rapporté. Montreal: Éditions Balzac.

Freunek, S. (2007). Literarische Mündlichkeit und Übersetzung. Am Beispiel deutscher und russischer Erzähltexte. Berlin: Frank & Timme.

Genette, G. (1987). Seuils. Paris: Seuil.

Gossas, C. & U. Norberg (2012). «Voices and imitation in the translation of children’s books: The case of De tre grottornas berg by Swedish author P.O. Enquist in French and German». In Fischer, M. B. & M. Wirf Naro (eds.). Translating Fictional Dialogue for Children and Young People. Berlin: Frank & Timme, pp. 185-200.

Laviosa-Braithwaite, S. (1998). «Universals of translation». In Baker, M. & K. Malmkjær (eds.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London & New York: Routledge, pp. 288-291.

Lindgren, C., Andersson, C., & C. Renaud. (2007). «La traduction des livres pour enfants suédois en français: 1ère partie: choix et transformations». La Revue des livres pour enfants, 234, pp. 87-93.

Marnette, S. (2005). Speech and Thought Presentation in French: Concepts and Strategies. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Nières-Chevrel, I. (2008). «Littérature de jeunesse et traduction : pour une mise en perspective historique». In Thouvenin, C. & Delarbre, A. (eds.). Traduire les livres pour la jeunesse: enjeux et spécificités. Paris: Hachette, pp. 17-30.

Nikolajeva, M. (2002). The Rethorics of Character in Children’s literature. Lanham, Maryland, & London: The Scarecrow Press.

O’Sullivan, E. (2003). «Narratology meets Translation Studies, or, The Voice of the Translator in Children’s Literature». 48/(1-2), pp. 197-207.

—(2005). Comparative Children’s Literature. New York: Routledge.

Rabatel, A. (2009). «A Brief Introduction to an Enunciative Approach to Point of View». In Hühn, P. et al (eds.). Point of View, Perspective, and Focalization. Modeling Mediation in Narrative. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 79-98.

Rosier, L. 2008. Le discours rapporté en français. Paris: Ophrys.

Schwitalla, J. & L. Tiittula (2009). Mündlichkeit in literarischen Erzählungen. Sprach- und Dialoggestaltung in modernen deutschen und finnischen Romanen und deren Übersetzungen. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Svenska barnboksinstitutet (SBI) (2004). Dokumentation och statistik. 2003 års utgivning. <http://www.sbi.kb.se/sv/Utgivning-och-statistik/Bokprovning/Dokumentation/> (Accessed on Nov. 1, 2013.).

Svenska språknämnden. (2005). Svenska skrivregler. Stockholm: Liber.

Taivalkoski-Shilov, K. (2006). La tierce main. Le discours rapporté dans les traductions françaises de Fielding au XVIIIe siècle. Arras: Artois Presses Université.

—(2010). «When Two Become One. Reported Discourse Viewed through a Translational Perspective». In Azadibougar, Omid (ed.). Translation Effects. Selected Papers of the CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2009, pp. 1-16.

—(2013). «Voice in the Field of Translation Studies». In Taivalkoski-Shilov, K. M. Suchet (eds.). La Traduction de voix intra-textuelles/Intratextual Voices in Translation. Québec: Éditions québécoises de l’oeuvre, pp. 1-9.

Toury, G. (1995/2012). Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Vanderauwera, R. (1985). Dutch novels translated into English: the Transformation of a «Minority» Literature. Amsterdam: Ropodi.

Audio material

Stark i P1 (Radio interview with P.O. Enquist) Dec. 21, 2010. <http://sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/64582?programid=3924>.

1 Enquist said in a radio interview in 2010 that he started writing children’s books without any thoughts that they were to be published. The driving force was to establish a writing relationship with his grandchildren (the heroes in the books are the grandchildren of the author under their right names and the places are authentic). Additionally, he says that he does not know how to write for children, since he himself is a bit too old to have read (modern) children’s literature as a child when it appeared in Sweden around 1945 (for example, Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren).

2 Even if it would have been interesting to compare the influence that editors have exerted in the translation process, it falls outside of the scope of this article to compare the presence of the voice of the editor in the two versions dealt with here.

3 Another example of the documentary style in the book is that the smugglers have read the first book, contact the author and make the woods described in the book their new scene of crime.

4 It is, however, worth mentioning that italics are also used for other various purposes. These were not viewed well by a number of the Swedish reviewers, who argued that their abundance gives them less impact (see also below).

5 Italics in the following examples are always from the books themselves. Underlining has been added by the authors for items that are considered in the discussion.

6 We have marked these by underlining in the example.

7 Insteg is according to the dictionary Svensk ordbok (2009) only used in a few expressions, and thus represents the somewhat old-fashioned vocabulary characterizing the book.

8 In Sweden, the first book was not well received either, as we showed in the former article (Gossas & Norberg, 2012). Some rather harsh criticism was made, focusing not least, like leading critic Lena Kåreland, on the dominance of the adult narrator and the many «winks to the adults». In France and Germany, the first book was instead highly praised. In France, it was claimed that the big Swedish author had placed himself at the child’s level, that the style was poetic, and they particularly mentioned the concomitance of burlesque and wisdom. The story was described as being both funny and touching. In Germany, as mentioned, the book received a prestigious prize and critics praised, above all, the full entry into the child’s perspective.

9 This translation of the reviews and all the following ones from French and German, respectively, are made by the authors.

10 It is not uncontroversial for authors to change market. In the field of children’s literature, authors and others have long strived to earn the prestige and recognition of adult literature. The author who normally writes for adults and who changes market will be judged with respect to her/his previous production as well as to the current expectations on children’s literature. On the other hand, it is possible that the work of the author will be praised according to the reputation s/he has already earned as a writer for adults. The reputation can be different in different cultures and this may also affect the assessment of translations.

11 It has been pointed out that, after all, there are no previous utterances to imitate in fictitious statements in novels, and therefore it is also more adequate to claim that in fiction you render «representations of words/statements of the other» (Rosier, 2008: 4) – the traces that are typical for the oral code are also neutralized in order to be intelligible.

12 The use of free direct discourse can be described as the 20th century parallel to the trend of using free indirect discourse in the 19th century, taking the liberation of the speech of the characters one step forward (see Marnette, 2005: 239). As Marnette points out, the lack of speech verb and of typographical marks «give an impression of immediacy that reinforces the impression that the narrator is not controlling the characters but merely observing them.» (2005: 248)

13 The dialogue continues for approximately two more pages, mainly with direct speech, with some turns integrated in the narration.

14 The French version also sometimes restructures paragraphs, and omits some repetitions, also concerning direct speech (e.g., utterances by grandson Marcus on p. 15, 38).

15 As recommended, for instance, by the norms prescribed by the Swedish official organ for language politics and purism (Språkrådet) in Svenska skrivregler (2005: 154).

16 Och Mischa sa, i drömmen alltså, men det var väldigt tydligt att hon sa det, att [..] ‘But Mischa said, in the dream that is, but it was very clear that she said it, that’ […]

17 The discourse used by grandfather in this example is discussed in section 2.

18 The neutralization of child language has been dealt with in previous research, e.g. in Lindgren et al. (2007).