A Brief History of Game Localisation

Miguel Á. Bernal-Merino

University of Roehampton

Lecturer in Game and Media Localisation

Breve historia de la localización de videojuegos

La historia de los videojuegos es bastante corta cuando se la compara con la de otros productos del mundo del entretenimiento tales como las obras de teatro y las películas, la poesía y las canciones, las novelas, etc. A pesar de lo torpe de sus comienzos, y del colapso de la industria después del primer pico, los productos de entretenimiento interactivo han ido adaptándose a distintas actividades de ocio, multiplicando las ganancias de la industria hasta superar las de los otros productos de entretenimiento. Este éxito estuvo y sigue directamente relacionado con el éxito de los profesionales de la localización de videojuegos, que tuvieron que crear estrategias y protocolos para satisfacer las exigencias inauditas de los productos multimedia interactivos. Este artículo hace un repaso de los cambios de los últimos treinta años con la esperanza de que la industria no repita los errores del pasado a la hora de enfrentarse al creciente mercado global.

palabras clave: videojuego, historia, culturalización, localización, globalización

Video games have a rather short history when compared against other entertainment products, such as plays and films, poetry and songs, novels, etc. Nevertheless, and despite its somewhat clumsy beginnings, and its early crash, interactive entertainment has found a way of adapting into different niches, and rocketing its returns beyond all other entertainment products. This success story was fully dependent, and is inextricably linked to the success story of the game localisation profession that had to be created from scratch in order to cover the unprecedented demands of multimedia interactive products. This article presents an overview of the changes in the past thirty years in the hope that it may help the industry avoid the errors of the past when facing the growing global marketplace.

key words: video game, history, culturalisation, localisation, globalisation

Although the game localisation industry is still improving its processes, and it is perhaps too early to have a final historical account, a quick glance at its evolution over the past decades can elucidate the role it played in the advent of video games as real contenders for our leisure time, and how they have changed the entertainment industry worldwide. This brief history can be divided into periods that help us understand the severe initial challenges and considerable adjustments that had to take place in game programming, project management, etc., in order to turn products tailored for local use into products that welcomed an ever-growing amount of consumer in different countries, and could adapt to their cultural values, legal systems, and expectations. The following pages are an introduction to the different stages in this non-stop progression that has made video games into the most lucrative entertainment industry ahead of books, music and films.

There was a great amount of preconceptions that had to be changed in almost every aspect of game developing and publishing in order to facilitate non-national sales. As it could be expected these changes were born out of market trends and foreign consumer demand, even if it was sometimes only found out indirectly due to the growth of grey (international) sales and black (illegal distribution) markets. There are basically four stages that could be aligned to the four decades since the beginning of video games:

1970s: the birth of the video game industry

US developers created games for the national market, initially only present in amusement arcades sharing the space with pinball machines, and foosball tables. Some of the most popular arcades where Computer Space and Pong, and such was their popularity that similar technology was quickly developed for home entertainment, and a great variety of consoles and computer systems could also play games.

Japanese creative minds swiftly realised the potential of these products and, by the end of the decade, they were the first to join in this US-only industry, specialising in arcade games that they would immediately make available to the enormous US market. There were very few exports if at all, and games would normally be shipped in their original (mostly English) versions to some European markets, mostly the United Kingdom. Many companies rushed into the market trying to get a foothold with different gaming systems (or platforms) and games. Establishing a brand and catering for the more immediate American and Japanese markets were the priorities, but we can’t really talk about a game localisation industry yet. Most video games relied on clear mechanics and engaging gameplay, so there was little text to be read, and in deed to be translated. This early period is in fact responsible for the introduction into most languages of English terms such as ‘arcade’, ‘joystick’, ‘score’ and, of course, ‘game over’. The need for localisation was rather low due to the small relevance of foreign markets. This wasn’t the case for developers in the Asia block, amongst other reasons, computer programming was in its infancy and only the Roman-based English alphabet could be easily displayed.

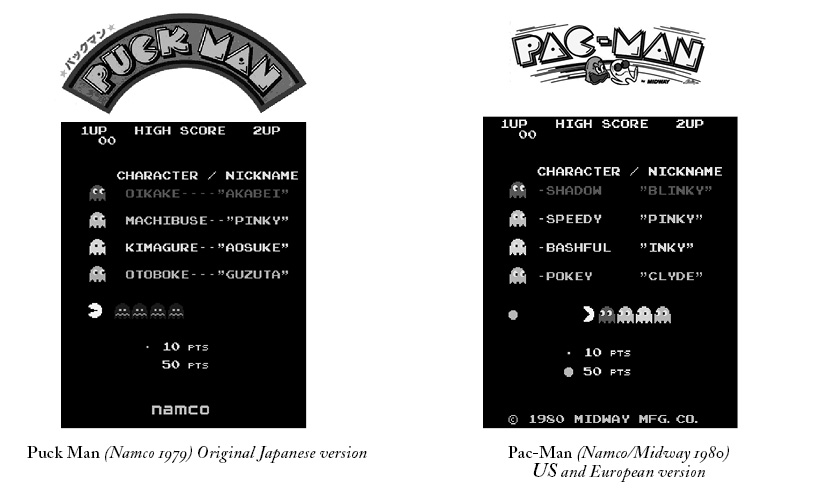

Commercially speaking, Japanese developers and publishers always saw the US as the best place for them to extend to and enlarge their return on investment (ROI), so it could be said that they were the ones who started thinking about localization earlier, if only out of sheer necessity. One of the main and earliest example of which is the internationally popular Pac-Man. The Japanese name was initially transliterated as ‘Puck Man’ (pronounced ‘pakkuman’), and it is a creation inspired on the Japanese onomatopoeia ‘paku paku taberu’, normally used to indicate that someone is eating eagerly and it imitates the fish-like opening and closing of the mouth. The initial transliteration into English Roman characters sounded like ‘Puck-Man’ to Japanese hears, but when localising the product for the US market, they decided that ‘Puck’ was far too close to the coarse four letter word ‘F***’, and decided to go for a similar but less troublesome spelling. The solution, ‘Pac-Man’, proved successful in every sense.

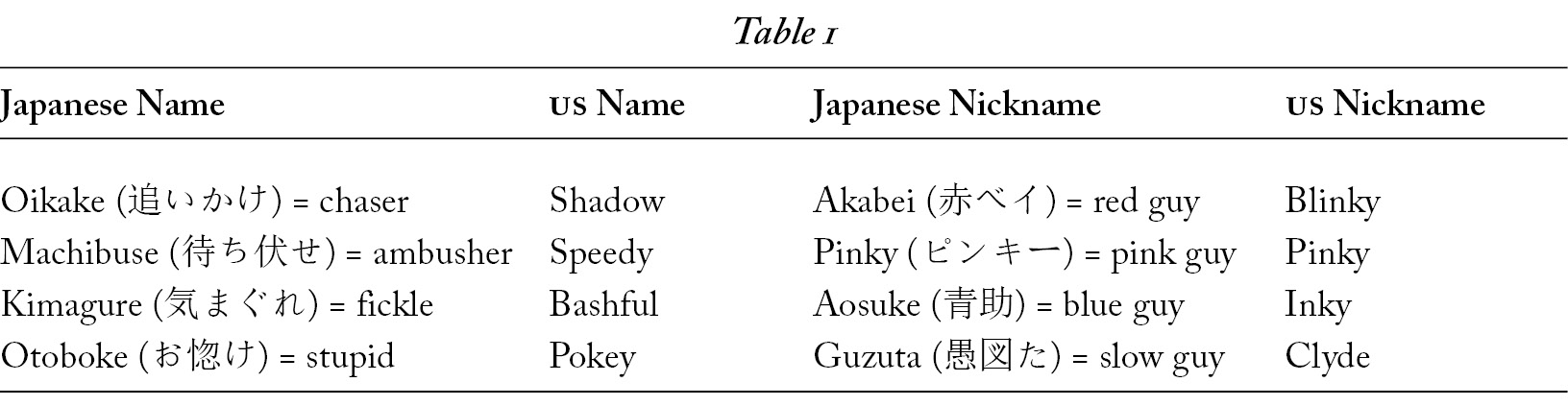

It is also worth noting that the original version never displayed Japanese script, this was very early on in the game industry (and even the software industry), and it was programmed in English displaying only English characters. Japanese characters could not be implemented (Unicode was first released in 19911) unless they were treated as images, so they employed the Romanised version of the kana. In the original Pac-Man, the four ghosts had their names and nicknames slightly altered. Instead of opting for a direct transliteration or a dry, dictionary translation of the original, the publisher decided to give a certain American gloss to the game just to make it more accessible to US players. All the characters had a name and nickname describing the ghost’s behaviour or colour. The North American version adopted a more playful approach, using euphonic and catchy names, as shown in the image above, and explained in the table 1 below.

This way of dealing with the localisation of video games for foreign markets is completely in line with the essence of games as customisable entertainment, and it fits perfectly with the development of the global market, where everything can be regarded as a product that needs adapting to easily reach new consumers in other geographies.

1980s: establishment of the game industry

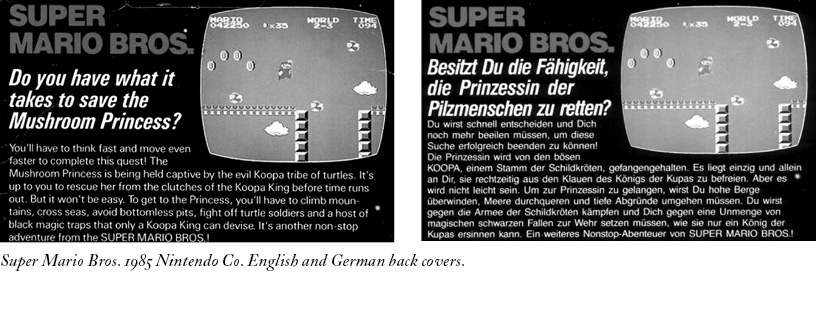

Although there was a bit of a setback in the 1982-84 period2 (many say due to lack of creativity and somewhat clumsy repetition of ideas and gameplay mechanics), by the end of the decade the interactive entertainment software industry was back in the black and making profits. There was also a significant increase in quality, expansion of the home console offer with the Sega Genesis, and the beginning of the handheld market with the Nintendo Game Boy. One of the most internationally appreciated game of that time was Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. which was distributed with packaging and documentation translated into German, French, Spanish, Italian and Dutch3, although the in-game text (menus, etc.) remained in English. This level of translation was often referred to as “Box and Docs”.

The translation of packaging and documentation became standard practice amongst those publishers who understood that this small investment could easily increase their revenues simply by being slightly more accessible to foreign consumers. So much so that the acronym ‘E-FIGS’ (that stands for ‘English, French, Italian, German, and Spanish’) was coined then, and has been used ever since because it is still the minimum default group of languages that most games are translated to. The early prioritisation of these languages was directly related to the maturity of their national markets in terms of amount of computer users, available per capita income, and demand for new forms of entertainment.

1990s European market established

This decade saw a shift from the minimal box’n’docs transition to what Chandler (2005: 14) calls “partial localisation” for most titles, where also the UI (user interface or interactive menus) would be translated, and subtitles would often be provided for pre-rendered cut scenes, and in-game animations. This proved to be a more than welcomed improvement because now non-English speakers were less dependent on manuals (they had to check constantly while playing), and they could also follow the story more closely and stay immerse in the game. The subtitle option also opened multimedia interactive entertainment for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community, both at home and abroad, since it enabled the option of intralingual as well as interlingual subtitles, making the game accessible and enjoyable to many more players, effectively enlarging national and international markets.

Although players were appreciative of these improvements, audio files remained an obvious sticking point. The recording of voiceovers for each language version is by far the most expensive part of any localisation project, and so it was reserved for the titles that were expected to be undisputed blockbusters. This is mostly a marketing decision and is often referred to as “full localisation”. The localisation of audio files was the first step towards treating international players as local ones, and the one that could be said to have established the game localisation industry as a necessary partner of the game industry. If video games were going to be considered a worthy entertainment option to the film, the music, and the book industry, they had to deliver equal or superior levels of service and adaptation to consumers. The benefit of interactive media is, of course, that customisation is part of the very nature of the technology that makes it possible, as well as part of the essence of entertainment software.

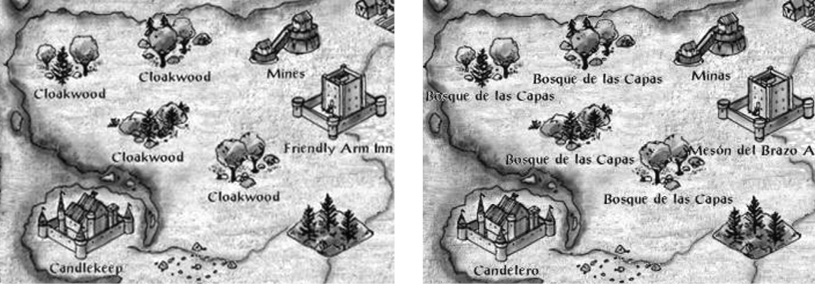

Some games during this decade pushed the boundaries proving beyond any doubts what could be done in localisation. Baldur’s Gate (Bioware/Interplay 1998), for example, was one of the first role playing games to be ‘fully’ translated and dubbed into Spanish. It was especially meaningful from the localisation point of view because, like most RPGs, it had hundreds of thousands of words (part of books, maps, and parchments found in the adventure) to be translated, as well as several thousand voiceover files to be recorded for each language version.

By the end of the nineties revenues had doubled in the games industry (ESA), and although there was some internal growth more than half of it came from the efforts put into localisation. This tendency continued in the following decade.

2000s. globalisation and the sim-ship race

As more and more countries joined the IT and internet revolution, the amount of players grew significantly which meant that the same video game product could potentially sell many more copies, if only the right localisation steps were taken. Due to the fact that video games have a rather short life span, even when immensely successful, the best way forward for game publishers was the simultaneous shipment of all language versions. The Sim-Ship model of distribution capitalises on the momentum built up by a single international marketing campaign, and minimises the risk of grey imports and piracy. In practical terms, what it means for language professionals is that most games are unfinished (not playable) when localisation needs to get started which has several and serious implications in workflow. This model prompted the beginning of a whole host of necessary changes in video game development, localisation and publishing, processes that are still taking place in many companies. Global revenue projections for the game market was around $20 billion dollars at the end of the 20th century, by the end of the first decade of the new millennium analysts (such as Price Waterhouse Coopers) has valued the interactive entertainment industry at around $50 billion. We have reached this figure despite the world recession. Although it can be argued that localising into more languages eats into revenues, it is clear that many of the international sales would not be there in the first place if not because of localisation.

Perhaps, one of the most significant changes to localisation (and the game industry in general) was the dramatic success of games in the online arena at the end of the 20th century, and particularly of MMOs (Massively Multiplayer Online games). Players found interacting online with other people around the world preferable to playing against the machine, dispelling the isolation argument often wielded by detractors of video games. Ultima Online (Origin Systems/EA 1997) was one of the first immensely popular MMOs with thousands of players; however, the undisputed king of the hill in this particular genre is World of Warcraft (Blizzard 2004-10) which reported in October 2010 having reached twelve million subscribers worldwide. But the great advancement of MMOs is not that they allow for thousands of concurrent players interacting in the virtual world, but that game creators can collect very detailed information about subscribers, their game style, their language of interaction, etc. Itemised market research data can be difficult to obtain, especially when having to deal with multiple countries, languages and character sets; online games that require some kind of registration or subscription, even when it is free, yields information from the moment the account is created. When demand is big enough for a particular language, publisher can translate the game being reassured by their own internal data and direct players’ feedback through forums. It is almost impossible to find specific figures with regards to how much revenue companies make as a result of having localised an MMO for another locale, but the fact that they keep increasing the languages they offer is telling in itself.

The first decade of the new millennium has seen many companies specialising in game localisation only, which is evidence of the volume of demand. Although not all games make constant use of voiceover, full localisation is slowly becoming the standard and what most consumers expect, because all triple A titles tend to have this characteristic.

the road ahead

As full localisation becomes standard practice for more and more languages, some professionals in both the language services and the game industry, have started talking about “deep” or “enhanced” localisation. This adjective modifying established, generic term is used to indicate that the game is brought closer to the consumer in each locale, in other words, anything that is not against the game world itself and can ease the immersion of players can be reconsidered and adapted to fit what is considered to have a more successful local impact. In a way, game localisation can at times take a creative role that traditional views on translation would sanction as being beyond the scope of language experts’ duties. The other point of view, and the one that perhaps applies in the case of video games, is that they are conceived as consumer products (and not works of art) from the very beginning, so in this sense, there is shared authorship and responsibility for its success and revenues; when this approach is employed on a multimedia interactive entertainment product, publishers and localisers have to guarantee that game elements that could be misinterpreted or lost in translation are deleted or adapted. It can be something as simple as adding all major ethnicities for players’ avatars, or local brands and celebrities that fans can relate to, or even change storylines and locations so as to not alienate consumers in particular locales. It is certainly a delicate concept and one that can be unwittingly stretched too far, but often games themselves state rather unambiguously what is admissible and what is not.

It was perhaps to be expected that as we venture deeper into a global capitalist society, consumers expect to be catered for, and multimedia interactive entertainment products are in a way the perfect exemplification of this, since they are customisable by design. Some games require only a straightforward translation of texts, because the concepts explored and the gameplay put forward is perhaps part of the common shared knowledge. There is however little doubt in my mind that full, enhanced localisation is the goal that most game publishers are working towards, because this would guarantee consumer satisfaction and, as a result, the increase in revenues, as well as the strengthening of the brand.

recibido y versión final: nov. de 2010

aceptado en enero de 2011

1 See official Unicode page www.unicode.org/history/publicationdates.html

2 Source Gamespot http://uk.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/video/hov/p5_01.html

3 Source Mobygames www.mobygames.com/game/super-mario-bros/cover-art/gameCoverId,104936/