The treatment of offensive and taboo terms in the subtitling of Reservoir Dogs into Spanish

José Javier Ávila-Cabrera

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid

Offensive and taboo exchanges are very recurrent in Quentin Tarantino’s films, whose screenplays are full of characters who swear, curse and make ample use of taboo terms. The way subtitlers deal with such terms can cause a greater impact on the audience than oral speech (Díaz Cintas, 2001a). This paper aims to provide some insights, from a Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS) approach, into the subtitling of offensive and taboo language into Spanish by examining Tarantino’s first blockbuster, Reservoir Dogs (1992), and making use of a multi-strategy design, which enhances triangulation (Robson, 2011). The ultimate goal is to shed some light on the way this film has been subtitled in Spain, by assessing whether the dialogue exchanges have been rendered in the subtitles in a close way to the source text or, by contrast, some type of censorship (i.e. ideological manipulation) may have taken place.

key words: Interlingual subtitling, offensive and taboo language, translation strategies, multi-strategy design, ideological manipulation.

El tratamiento de los términos ofensivos y tabú en la subtitulación de Reservoir Dogs al español

Los diálogos ofensivos y tabú son muy recurrentes en los filmes de Quentin Tarantino, uno de los cineastas cuyos guiones incluyen personajes que dicen palabrotas y utilizan todo tipo de términos tabú. La manera en la que los subtituladores tratan estos términos puede causar un gran impacto en la audiencia, mayor que el producido por el lenguaje oral (Díaz Cintas, 2001a). Este artículo pretende esclarecer, desde un punto de vista basado en los Estudios Descriptivos de Traducción (EDT), cómo se ha subtitulado el lenguaje ofensivo y tabú del primer éxito cinematográfico de Tarantino, Reservoir Dogs (1992), por medio de un diseño multiestratégico que hace uso de la triangulación (Robson, 2011). Así pues, se espera arrojar luz con respecto al modo en que este filme se ha subtitulado en España, analizando si los subtítulos siguen de cerca el texto origen o, si por el contrario, se ha dado algún tipo de censura (como la manipulación ideológica).

palabras clave: Subtitulación interlingüística, lenguaje ofensivo y tabú, estrategias traductológicas, diseño multiestratégico, manipulación ideológica.

Language can take the form of several registers depending on the context in which it is used. When dealing with informal language on screen, there are low register terms, which can cause emotional impact leading to rejection or negative reception in the audience. Some authors refer to such terms as dirty language (Jay, 1980), strong language (Scandura, 2004), bad language (McEnery, 2006), foul language (Wajnryb, 2005), rude language (Hughes, 2006), taboo language (Allan and Burridge, 2006; Jay, 2009), emotionally charged language (Díaz Cintas and Remael, 2007) and/or offensive language (Díaz Cintas, 2012; Filmer, 2014). In an attempt to be consistent with our terminology, we will resort to the phrase offensive and taboo language (Ávila Cabrera, 2014).

Subtitling Tarantino’s dialogue presents a considerable challenge to any translator because of the difficulties encountered while dealing with very fast exchanges, which are liberally peppered with offensive and taboo elements, while at the same time having to abide by the technical requirements of this particular mode of audiovisual translation (AVT). In this regard, not only does this paper examine the way in which these terms have been subtitled, making use of a taxonomy of offensive/taboo terms, but it also illustrates a number of translation strategies employed in subtitling. In addition, technical constraints have been carefully observed in order to prove whether the toning down or deletion of this type of terms is due to spatio-temporal constraints or, by contrast, the subtitler may have flattened them because of pressure by the client or because of his/her own decision, in which case ideological manipulation can be said to have taken place.

2. SUBTITLING

Subtitlers not only have to deal with the rendering of a source text (ST) into a target text (TT), but they also have to bear in mind certain restrictions impinging on the choices that they can make. Temporal and spatial restrictions do not allow subtitlers to write as many characters per line as they might want, since it is advisable that subtitles appear on screen for a minimum of one second and a maximum of six seconds (D’Ydewalle et al., 1987; Brondeel, 1994) and occupy one line (one-liners) or two lines (two-liners) of text. Within these technical limitations, their use of appropriate translation strategies is paramount in order to tackle the numerous difficulties that they have to face when transferring ST terms into the TT.

2.1. Technical restrictions

Offensive and taboo language can be said to contribute to fulfilling a thematic function in the film and their deletion may therefore entail the loss of the characters’ linguistic attributes. This type of language is, nonetheless, usually toned down and even omitted when temporal or spatial constraints are stringent (Díaz Cintas and Remael, 2007). When working for the DVD industry, it is not unusual to adhere to a reading speed of 180 words per minute, though some companies may resort to even higher rates. Table 1 shows the calculations for this reading speed (Díaz Cintas and Remael, 2007: 97), which are used in the present study to analyse all the examples extracted from the audiovisual corpus under scrutiny:

|

180 words per minute |

seconds : frames |

spaces |

seconds : frames |

spaces |

|

01:00 01:04 01:08 01:12 01:16 01:20 |

17 20 23 26 28 30 |

02:00 02:04 02:08 02:12 02:16 02:20 |

35 37 39 43 45 49 |

|

|

seconds : frames |

seconds : frames |

spaces |

seconds : frames |

spaces |

|

03:00 03:04 03:08 03:12 03:16 03:20 |

04:00 04:04 04:08 04:12 04:16 04:20 |

70 73 76 76 77 77 |

05:00 05:04 05:08 05:12 05:16 05:20 06:00 |

78 78 78 78 78 78 78 |

Table 1. Equivalence between time/space for 180 wpm

These calculations are based on WinCAPS, Screen’s professional subtitling preparation software package, and show the equivalence between seconds/frames and the suggested maximum number of characters for the TT.

2.2. Subtitling strategies

The subtitling strategies chosen for this paper have been selected in accordance with the features of the type of register being analysed. Eight strategies are described below and follow the classifications proposed by Vinay and Darbelnet (2000: 86-88), in the case of strategy one, and Díaz Cintas and Remael (2007: 202-207) for the other seven, which are described as follows:

Literal translation (LT), also known as word for word or verbatim translation, entails the direct transfer of a word/cluster of words from a source language (SL) into a target language (TL), in keeping with the grammar and idiom of the original (Vinay and Darbelnet, 2000). To cite an example from the corpus, «he tried to fuck me» has been literally subtitled as ha intentado follarme [he has tried to fuck me].

- A calque (CAL) is a literal translation of a word or expression in a way that it is not usual in the TL. For example, when Mr Blonde is about to burn Officer Nash alive, he tells him «have some fire», subtitled as ten fuego [have fire] rather than the more common vas a arder [you are going to burn]. As it can be observed, calques are not very idiomatic and they tend to lean towards foreignisation.

- Explicitation (EXP) has the effect of bringing the target audience closer to the subtitled text through the use of specification, by using a hyponym (i.e. a word with a more precise meaning), or by resorting to a hypernym or superordinate (i.e. a word with a broader meaning). For example, when Mr Orange uses the verb «bleed», the translation resorts to the hyponym desangrándonos [bleeding to death].

- Substitution (SUBS) is a variant of explicitation and constitutes a typical subtitling strategy since it tends to be used when the spatial constraints do not allow for the insertion of a long term in the subtitle. Eddie says «I know, motherfucker» which is subtitled as ya lo sé, coño [I know it, bloody hell]. As it can be observed, the insult «motherfucker» is changed for a shorter term in the TL, coño [bloody hell], which can be said to maintain the tone of the original.

- Transposition (TRAN) is carried out when the item from one culture is changed for another from a different culture, a procedure that tends to imply some sort of clarification. The violent allusion to a «Wild West show», which might remind the viewer of armed standoffs, has been dealt with via transposition, which can be seen in the rendering carnicería [slaughter].

- Compensation (COM) entails making up for a translational loss at a certain point in the programme by reconsidering the translation at another point in the TT. To cite an example, one of the main characters says «we got a major situation here», which gets subtitled as está bastante jodido [it is quite fucked up]. The ST expression does not contain any offensive element, but the subtitler has, nonetheless, subtitled it by resorting to a vulgar expression to compensate for any tone downs in other parts of the film.

- Omission (OMS) is rather frequent in subtitling due to technical limitations in the form of spatio-temporal constraints, and may entail the deletion of words, clauses and sentences containing proper nouns, vocatives, adverbs, conjunctions and the like. An example takes place when Mr Pink asks Mr White «did he fucking die?» and the subtitle resorts to ¿la ha palmado? [has he snuffed it?], where the derogatory item «fucking» has been deleted.

- Reformulation (REF) is used to express an idea in a different way, by rephrasing the ST. Sometimes reformulation entails text reduction/condensation and its main function is to transmit the ST terms in an idiomatic way. This strategy will be considered for both cases of rephrasing and condensation, that is, when the word/utterance is expressed in a different way and/or it is abbreviated. Mr Orange recurrently says «I’m gonna die», which is reformulated as me muero [I die], rather than the more literal me voy a morir [I am going to die], an instance where reformulation and condensation converge.

In order to understand how the translation strategies work in subtitling, it is paramount to acknowledge the existence of two channels – the acoustic and the visual – which make the audiovisual programme a complex semiotic composite (Chaume, 2004: 16).

3. OFFENSIVE AND TABOO LANGUAGE

Offensive language refers to those linguistic terms or expressions made up of swearwords, expletives, etc., which are normally considered derogatory and/or insulting. This type of language, considered to be low register (Murray et al., 1884), entails «a particular choice of diction or vocabulary regarded as appropriate for a certain topic or social situation» (Hughes, 2006: 386). Taboo language is related to terms that are not considered appropriate or acceptable with regard to the context, culture, language and/or medium where they are uttered. All these denominations have been included under the umbrella term of offensive and taboo language, in an attempt to be linguistically consistent.

Offensive and taboo language exists in the majority of cultures although the acceptability of this type of linguistic register differs according to the type of society, culture, beliefs and the like. All these terms are understood to be part of offensive, bad or emotional language and can be grouped into various subcategories, which are described below.

3.1. Taxonomy on offensive and taboo categories

For this study, a taxonomy of offensive and taboo language based on Wajnryb (2005), Hughes (2006), and Jay (2009) is used. This classification, summarised in table 2, shows examples taken from the dialogue exchanges in American English of the audiovisual corpus and has been employed to categorise every single offensive/taboo element under analysis:

Table 2. Taxonomy of offensive and taboo language

|

TAXONOMY OF OFFENSIVE AND TABOO LANGUAGE |

|||

|

Category |

Subcategory |

Types |

Examples |

|

Offensive |

Abusive Swearwords |

Cursing |

Goddamn you! |

|

Derogatory tone |

I’m sick of fucking hearing it |

||

|

Insult |

A real fucking animal |

||

|

Oath |

I swear on my mother’s eternal soul |

||

|

Expletives |

Exclamatory swearword / phrase |

Holy shit! |

|

|

Invectives |

Subtle insult |

It’s the one job basically any woman can get |

|

|

Taboo |

Profane / blasphemous |

Jesus Christ |

|

|

Animal name terms |

You know what these chicks make |

||

|

Ethnic / racial / gender slurs |

[…] like a bunch of fucking niggers |

||

|

Psychological / physical condition |

He went crazy |

||

|

Sexual / body part references |

Like a Virgin was a metaphor for big dicks |

||

|

Urination / scatology |

I gotta take a squirt |

||

|

Filth |

You shit in your pants and dive in and swim |

||

|

Drugs / excessive alcohol consumption |

I wasn’t gonna be Joe the Pot Man |

||

|

Violence |

I’m gonna fucking blow you away |

||

|

Death / killing |

He was gonna blow you to hell |

||

Within the offensive language category, the following subcategories can be found:

(1) Abusive swearwords refer to those terms that can be considered abusive, derogatory and/or insulting, and which can involve metaphoric curses (Wajnryb, 2005). This category is divided into four subcategories. «Cursing invokes the aid of a higher being; it is more ritualistic and deliberately articulated […] and it may not involve the use of foul language» (Wajnryb, 2005: 20). Swearwords can be considered derogatory in tone as is the case with «this is a shitty piece of work» (Wajnryb, 2005: 17). The third category is that of insults. According to Wajnryb (2005: 19), swearwords and insults can be said to go hand in hand in real language, for example «fuck you, maniac». Thus, we could refer to insults as those terms in which you swear at someone with the aim of insulting him/her. When talking about oaths, we can refer to a formal promise (Hughes, 2006) or, as it is of interest here, an oath «is rather like the loose metaphoric curse», for instance «He muttered an oath when the hammer hit his finger» (Wajnryb, 2005: 20).

(2) Expletives are exclamatory swearwords or swear phrases uttered in emotional situations to express anger, frustration, joy, surprise, and the like (Wajnryb, 2005: 18-19). Expletives are not normally addressed to anyone in particular and their function is primarily to release the speaker’s emotion in relation to a given situation, as in «shit!», «fuck!», and «fucking hell!».

(3) An invective is a subtle version of an insult used in a formal context (Wajnryb, 2005: 20). It can be said to constitute an insult rather than a swearword, inasmuch as it tends to avoid the use of standard terms resorting to irony, wit and wordplay. It allows the speaker to be disrespectful towards someone without having to resort to the use of offensive words, as in the phrase «you shining wit» (Wajnryb, 2005: 20).

The second part of the taxonomy is made of terms considered taboo. Historically, taboo topics have moved from religious to secular areas such as sex and race, and «they can manifest themselves in relation to a wide variety of things, creatures, human experiences, conditions, deeds, and words (Hughes, 2006: 462). Nowadays, the use of taboo words is related more to expressing something considered grossly impolite or offensive rather than strictly forbidden. The various subcategories within this group are described below.

(1) As noted by Jay (2009: 153-154), taboo words can be categorised as «profane or blasphemous (goddam, Jesus Christ)». Firstly, profanity can be understood as «swearing through the use of words that abuse anything sacred» (Wajnryb, 2005: 21). It may not involve vilifying «God» or «Jesus» for example. Secondly, blasphemy is «a form of swearing that deliberately vilifies religion or anything associated with religious meaning» (Wajnryb, 2005: 17). For instance, although «Jeez» is very common nowadays, it might be regarded as blasphemous if it were to be said so as to offend a committed Christian. Blasphemy used in this way can therefore be said to constitute a deliberate insult. (2) In the words of Jay (2009: 153-154), they can also extend to «some animal names (bitch, pig, ass)»; (3) «ethnic-racial-gender slurs (nigger, fag, dago)»; and (4) references to «psychological, physical, or social deviations (retard, wimp, lard ass)», where physical conditions are taken into account. (5) Taboo language can be said to include «sexual references and body parts», for example «blow job», «cunt», «a guy with a big dick»; (6) «body products and bodily functions», the latter falls within the subcategories of «urination and scatology», i.e. «shit», «crap», «I gotta take a piss». (7) According to Wajnryb (2005), expressions connected with «filth» are also included within the taboo subcategory, examples of which are «pigs sleep and root in shit». In addition to all these subcategories, Hughes (2006: 231) also discusses the new values present in US cinema, such as those provided by Tarantino himself, where there is room for many taboo topics such as «gratuitous violence, gangsterism, drug culture, sexual promiscuity, sodomy, and racism». (8) Thus, in this author’s view (Hughes, 2006), the subcategories pertaining to «drugs», including the «excessive consumption of alcohol» and (9) «violence», have also been added as subcategories within the taboo category given that talking about the aforementioned items can be a taboo topic depending on several aspects such as viewers’ age, culture, language, etc. (10) Lastly, Wajnryb (2005) considers «death referents» to constitute taboo words as well, and these are categorised in these pages under «death/killing».

3.2. Censorship and manipulation

From a linguistic perspective, censorship has been defined as «the suppression or prohibition of speech or writing that is condemned as subversive of the common good» (Allan and Burridge, 2006: 13). In the words of Hughes (2006: 62), «[c]ensorship basically takes two forms, namely preventive interference by the state prior to publication, or subsequent punitive prosecution, dealt with more fully under fines and penalties and lawsuits». Other types of external intervention can be exerted by Press regulatory bodies, the Church or the government. In addition, there is another internal force known as self-censorship through which translators themselves are the ones to censor certain words or expressions for the sake of the target audience, determining what is right or wrong. All types of interventions whether imposed or voluntarily selected can be caused by cultural standards within a society, namely political correctness. Allan and Burridge (2006: 90) «consider political correctness as a brainwashing programme and as simple good manners».

Audiovisual texts can of course be the object of manipulation, which Díaz Cintas (2012: 285) defines as «the incorporation in the target text of any change (including deletions and additions) that deliberately departs from what is said (or shown) in the original». This concept, which can be said to be carried out in the service of power, somewhat relates to what Lefevere (1984: 92) knows as patronage: «any kind of force that can be influential in encouraging and propagating, but also in discouraging, censoring and destroying works of literature». Within patronage, Lefevere (1992: 16) distinguishes the ideological, economic and status components. In the present paper, the ideological component is of particular interest.

According to Díaz Cintas (2012: 284), manipulation does not have to entail always a negative connotation. Subtitling, for instance, is subject to spatio-temporal constraints which on occasions force dialogue exchanges to be condensed in the TL in order to respect the technical restrictions. This is what the author knows as «technical manipulation» and it should not be seen as an opportunity to tone down or delete offensive and/or taboo elements in the subtitles, although this has been the case especially in past regimes in which censorship was routinely carried out (Merino, 2007).

Translators play a leading role capable of disseminating or restricting the ideological discourse present in their culture (Díaz Cintas, 2012). The way texts are transferred may give place to the transmission of the values of the source culture or to ideological manipulation, leading to linguistic choices which come into conflict with ideological considerations, as it can be the case when dealing with the subtitling of offensive and taboo terms.

3.3. Research on offensive/taboo language

Various studies have shed light on these less explored linguistic fields, usually from a sociological or psychological perspective. Montagu (1973) examines the anatomy of swearing, documenting the history of taboo words/phrases and examining the genre from a philosophical and psychological perspective. Jay (1980; 1992; 2009), a world-renowned expert on cursing, takes a psychological approach when analysing the use of dirty language, sex roles and punishment for curses. Allan and Burridge (1991; 2006) deal with the social value of euphemisms, dysphemisms and forbidden words, whilst Dooling (1996) is more interested in swearing, free speech and sexual harassment. In his early work, Hughes (1991/1998) looks at foul language, oaths and profanity from a socio-historical perspective. And later, he published an encyclopaedia on swearing, including the social history of oaths, profanity, foul language, and ethnic slurs all over the English-speaking world, which first appeared in 2006. Not only does this work delve into the aforementioned concepts etymologically, but it also provides the reader with a vast array of insights into terms related with bad and forbidden language from a historical approach.

The Lancaster Corpus of Abuse (LCA), a project hosted within the British National Corpus (BNC), is focussed on spoken bad language and contains entries classified according to speakers’ sex, age and social class (McEnery, 2006).

Regarding AVT, there are various studies that have motivated the interest for the present study. Díaz Cintas (2001b) deals with the subtitling of strong and taboo terms and pays special attention to the translation of sex-related language from Spanish into English in the TV and video/cinema versions of the film La flor de mi secreto [The Flower of My Secret], a film directed by Pedro Almodóvar in 1995. Contrary to the initial assumption that subtitles would be more daring in the video/cinema version than in the television one, the latter was found to be more explicit and to follow the ST more closely than the VHS version. Filmer (2014) devotes her study to the transfer of offensive language, in the form of racial slurs and swearwords, between cultures with different societal values and taboos, namely, between the US and Italy. Based on different approaches such as politeness theory, linguistic anthropology, discourse analysis and DTS, she compares derogatory racial examples extracted from Gran Torino (Clint Eastwood, 2008) with the TT renderings of the subtitled and dubbed Italian versions. She foregrounds the fact that not only do the translated programmes mirror some of the racial slurs of the original film but they also make use of homophobic insults that were not present in the English dialogue.

4. METHODOLOGY

The methodology followed in this study is primarily based on the DTS paradigm, and focuses on the operations carried out during the process of translation. It is firmly rooted on the case study method and makes use of the multi-strategy design, which combines quantitative with qualitative data (Robson, 2011).

4.1. Research questions

In an attempt to shed light on the way offensive and taboo language found in the film Reservoir Dogs has been subtitled into Spanish for a Spanish audience, the present paper addresses the following questions:

- What are the most recurrent offensive/taboo subcategories found in the corpus under analysis?

- What are the translation strategies that the subtitler has used when rendering the offensive and taboo exchanges into the Spanish subtitles?

These two questions will be answered by undertaking a quantitative analysis of the dialogue and subtitles of the film analysed.

- What pattern did the subtitler follow when dealing with the transfer of offensive/taboo terms? In order to answer this question we will look ivwnto the number of instances where the offensive and taboo terms have been toned up, maintained (i.e. the offensive/taboo load is kept), toned down (i.e. the offensive/taboo load is softened), neutralised (i.e. the offensive/taboo load disappears in the TT as it is rendered in more neutral terms) or omitted (i.e. the offensive/taboo load is null). This data will help ascertain whether there has been any type of (self-)censorship on the subtitled programme. In order to address the first of these questions, a quantitative analysis will be carried out. To approach the second aim, and given the impossibility of contacting the actual subtitler, Fernanda Leboreiro – the marketing director of the company Bandaparte subtítulos, where the subtitling of Reservoir Dogs was commissioned – was interviewed to find out whether the subtitler was given certain instructions to deal with the rendering of offensive and taboo language.

- When dealing with the subtitling of offensive/taboo words, can the implementation of omission, reformulation and/or substitution be justified because of potential spatio-temporal constraints?

Multi-strategy designs can be divided into different typologies and the one chosen for the present study, known as «sequential explanatory design», is based on Creswell (2003). Firstly, data is collected and analysed quantitatively. Secondly, data is collected and analysed qualitatively. Priority is given to the quantitative data and then during the interpretation stage of study, the function of the qualitative data is to explain and interpret the findings uncovered in the quantitative study.

4.2. Data analysis

Reservoir Dogs (1992) was Tarantino’s first blockbuster film produced by Live America, and Dog Eat Dog Productions Inc. Filmed in Los Angeles and shot in American English, it lasts 99 minutes. It was rated R «contains some adult material» by the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America)1 because of its extreme violence and threatening language.

This case study has been conducted on the DVD version of the film, where 645 instances of offensive and taboo terms have been found in the original dialogue and shown in 501 subtitles. Taking into account that the DVD version contains a total of 1,231 Spanish subtitles, offensive and taboo language appears in 40.7% of all subtitles.

The following are some of the most illustrative examples2 found in the subtitles of the film:

|

example 1 |

||

|

Context: The film starts with eight men in black having breakfast at a café, Mr White, Mr Pink, Mr Blue, Mr Blonde, Mr Orange, Mr Brown, the big boss Joe Cabot and his son Nice Guy Eddie Cabot. |

||

|

Mr White: I’m sick of fucking hearing it Joe, I’ll give it back when we leave […] Toby Chung? Fucking Charlie Chan! […] and Toby the Jap I-don’t- know-what coming out of my right. |

||

|

0039 00:02:11:06 00:02:13:21 |

Estoy hasta los huevos. Te la daré al salir. |

[I am up to the balls/fucking sick of it. I will give it back to you when getting out.] |

|

0044 00:02:27:17 00:02:30:02 |

¿Toby Chang? El puto Charlie Chan. |

[Tobby Chang? The fucking Charlie Chan.] |

|

0046 00:02:33:18 00:02:36:11 |

a la chinita Toby en el derecho. |

[the little Chinese (girl) Toby in the right.] |

|

0039. Abusive swearing (derogatory) > REF at clause level (maintained) 0044. Abusive swearing (derogatory) > LT (maintained) 0046. Taboo (racial) > TRAN (maintained) |

||

|

example 2 |

||

|

Context: Mr White has taken Mr Orange to the warehouse. The latter believes that he is going to die. |

||

|

Mr White: I can’t take you to hospital. Mr Orange: Fuck jail, man! ... I swear to fucking God, man. Mr White: You’re not gonna fucking die, kid, all right? |

||

|

0198 00:13:31:23 00:13:34:22 |

-No puedo llevarte al hospital. -¡No me jodas! |

[-I cannot take you to the hospital. -Do not fuck me!] |

|

0202 00:13:50:03 00:13:52:21 |

Mierda, te lo juro por Dios. |

[Shit, I swear to God.] |

|

0206 00:14:06:16 00:14:09:24 |

No te vas a morir, ¿vale? |

[You are not going to die, right?] |

|

0198. Abusive swearing (derogatory) > REF at clause level (maintained) 0202. Taboo (blasphemy) > REF at clause level (toned down) (NOT technically justified) 02:22-28(50) 0206. Taboo (death) > REF at clause level (toned down) (NOT technically justified) 03:13-25(63) |

||

|

example 3 |

||

|

Context: Mr Blonde enters the warehouse and more arguments and quarrelling arise. |

||

|

Mr Pink: You’re acting like a bunch of fucking niggers, man! You wanna be niggers, ah. Just like you two always saying they’re gonna kill each other! Mr White: You said you thought about taking him out! |

||

|

0496 00:33:54:22 00:33:57:05 |

Os comportáis como un par de negros. |

[You behave like a couple of blacks.] |

|

0497 00:33:57:10 00:33:59:24 |

Siempre están diciendo que se van a matar. |

[They are always saying that they are going to kill each other.] |

|

0496. Abusive swearing (insult) > SUBS (neutralised) (NOT technically justified) 02:13-35(44) 0497. Taboo (racial) / taboo (killing) > OMS at clause level (technically justified) 02:19-41(48) / LT (maintained) |

||

In subtitle (0039) the swearword «fucking» has been translated by means of reformulation, i.e. hasta los huevos [up to the balls/fucking sick of it], so this instance of swearing has been addressed by rephrasing, using a term that is more common in the TT (domestication) and maintaining the offensive load. In subtitle (0044), the phrase «fucking Charlie Chang» has been translated literally, el puto Charlie Chang, so that this is another instance of domestication. In the next subtitle (0046), the term «Jap» became offensive in the US during World War II, when it was used to refer to the Japanese.3 In the film, it has been translated using transposition inasmuch as it is not usual to refer to the Japanese derogatorily in Peninsular Spanish. Hence, the preference for the term chinita [little Chinese (girl)], which derives its derogatory load from the feminisation of the addressee.

In (0198), the derogatory adjective «fuck» has been reformulated and the subtitler has resorted to the offensive utterance no me jodas [do not fuck me], which maintains the offensive tone of the ST. The blasphemy «I swear to fucking God», found in (0202), is potentially extremely offensive to some users of the TL and this could be the reason why the subtitler has reformulated it by using the softer word mierda [shit] but followed by the oath te lo juro por Dios [I swear to God]. Since this subtitle remains on screen for 2:22 and uses 28 characters out of some potential 50 characters if the reading speed is assumed to be of 180 wpm, it can be concluded that the deletion of the qualifier might not have been carried out for technical reasons and, arguably, this translational operation could represent a case of censorship or ideological manipulation. In (0206), the sentence «You’re not… die» has been translated very closely to the original though the taboo expression «fucking» that qualifies the verb has been missed out, thereby toning down the TT. As this subtitle lasts 3:13 and makes use of only 25 characters out of potential maximum of 63 characters, the omission may not be technically justifiable.

The phrase «fucking niggers», found in (0496), is a strong insult with a racially abusive load, particularly when the term «nigger» is uttered by white people (Dalzell and Victor, 2008: 457). However, the offensive tone of this expression is not reflected in its Spanish counterpart: par de negros [pair of blacks]. The Spanish substitution can be said to contribute to the neutralisation of the TT and may not have been technically motivated as the subtitle lasts for 2:13 and uses only 35 characters of a potential maximum of 44. In (0497), the clause containing «niggers» has been omitted and the verb «kill» has been faithfully rendered, a way of acting that may be justified by the fact that there is not enough space to include more information as the subtitle has a duration of 2:19 and uses 41 characters out of some possible 48.

5. DISCUSSION

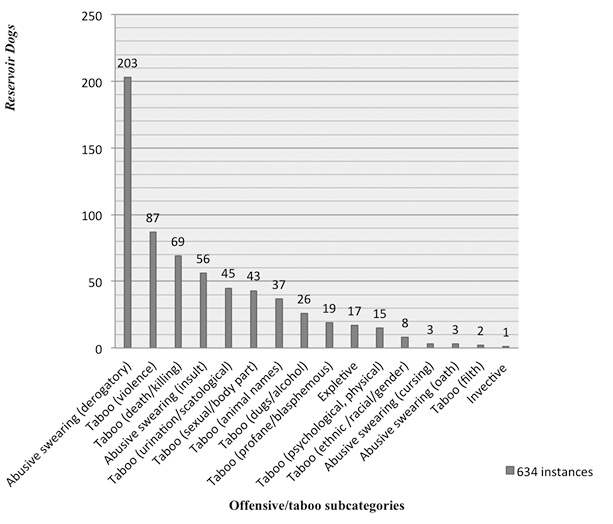

Figure 1 offers a visual representation of the most recurrent offensive/taboo subcategories found in the original English dialogue:

Figure 1. Offensive/taboo subcategories in the original

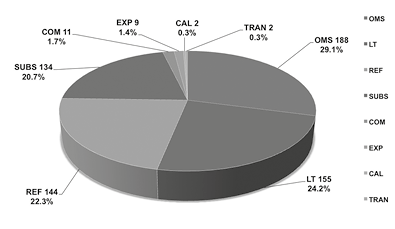

As it can be seen, there are 634 instances of offensive (45%) and taboo (55%) language found in the original dialogue, which have been dealt with by activating eight different translation strategies in Spanish. The translation strategies used by the subtitler are illustrated in figure 2:

Figure 2. Translation strategies used in the subtitles

The most widespread translation strategy is omission (29.1%), literal translation (24.2%) is the second most widely employed strategy, closely followed by reformulation (22.3%).

To verify the overall approach followed by the subtitler when dealing with the transfer of offensive/taboo terms, we examine the number of instances where this type of language has been toned up, maintained, toned down, neutralised or omitted and we also consider whether any (self-)censorship may have influenced the translation. Table 3 offers a summary:

table 3.

offensive/taboo load in the subtitles

|

reservoir dogs |

instances |

percentage |

|

Toned up |

37 |

5.7% |

|

Maintained |

325 |

50.4% |

|

Toned down |

33 |

5.1% |

|

transferred –total |

395 |

61.2% |

|

neutralised |

56 |

8.7% |

|

Omitted |

194 |

30.1% |

|

non-transferred – total |

250 |

38.8% |

|

Grand total |

645 |

100% |

In 395 cases, 61.2%, the offensive/taboo load of the English dialogue has been transferred to the Spanish subtitles. Of these, in only 5.7% of examples the load has been toned up, and in 50.4% it has been maintained, whereas the load has been toned down in 5.1% of the cases. On the other hand, the offensive/taboo load has not been transferred at all from the original dialogue into the subtitles on 38.8% of the occasions, where the subtitler has opted for neutralisation (8.7%) and omission (30.1%).

It has not been possible to locate the subtitler of this film into Spanish for a direct interview to discuss issues of (self-)censorship. After some extensive research, it was revealed that the Spanish subtitles were carried out at the subtitling studio Bandaparte subtítulos, in Madrid. Fernanda Leboreiro, the marketing director of this company, confirmed that they did not keep any records of the translators’ personal details prior to 1999. She also claimed not to know whether there had been any form of censorship or imposition relating to the translation of offensive and/or taboo language by clients and, in her view, this type of imposition was not common at that time. Thus, it could only be concluded that the cases where the offensive/taboo load has been toned down or eliminated might be connected with the operations carried out by the subtitler and/or technician rather than the studio or the client.

When it comes to ascertain whether the implementation of omission and neutralisation can be technically justified by the spatio-temporal constraints present in subtitling, table 4 below offers a synopsis, in which the number of technically unjustifiable cases (77.6%) is over three times higher than those that were conditioned by technical constraints (22.4%):

One of the most far-reaching conclusion can be drawn from taking a look at the total number of instances in which the emotionally charged load of offensive/taboo terms has been retained (61.2%), as it can be seen in figure 3:

Figure 3. Offensive/taboo language in the subtitles

Taking these figures and percentages into consideration, it can be concluded that the general trend in the subtitling into Spanish of the offensive and taboo language found in Reservoir Dogs is far from being quantitatively faithful to the ST. Indeed, based on the results detailed in figure 3, it can be argued that (ideological) manipulation may have occurred in this subtitling process insofar as the TT has not remained close to the ST in a high percentage of instances (30.1%), where there is no apparent technical constraint for the elimination of the offensive terms.

6. CONCLUSION

The use of offensive and taboo language in the form of abusive swearing, expletives, invectives and taboo words is a sensitive, controversial issue that has received little academic attention within AVT and hitherto has been researched more in the case of dubbing than subtitling. Although not socially acceptable in certain contexts, offensive and taboo language is a tool that depicts characters’ linguistic idiosyncrasies, feelings and emotions. The softening or omission of these terms risk jeopardising the intended function that they have in a given dialogue and on a given speaker. In this respect, more research is needed on the way this type of language tends to be subtitled into Peninsular Spanish in order to provide the academic and professional circles with more insights into how best to deal with the subtitling of low register expressions.

Recibido en agosto de 2014

Aceptado en diciembre de 2015

Versión final de noviembre de 2015

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allan, K. and Burridge, K. (1991). Euphemism and Dysphemism: Language Used as Shield and Weapon. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

— (2006). Forbidden Words: Taboo and the Censoring of Language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ávila Cabrera, J. J. (2014). The Subtitling of Offensive and Taboo Language: A Descriptive Study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Madrid. Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia.

Brondeel, H. (1994). «Teaching subtitling routines». [Online] META, 34/1, pp. 26-33. Available from: id.erudit.org/iderudit/002150ar. [Accessed: 10th January 2012].

Chaume, F. (2004). Cine y traducción. Madrid: Cátedra.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd edn). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dalzell, T. and Victor, T. (2008). The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (8th edn). London and New York: Routledge.

Díaz Cintas, J. (2001a). La traducción audiovisual: el subtitulado. Salamanca: Almar.

— (2001b). «Sex, (sub)titles and videotapes». In L. Lorenzo García and A. M. Pereira Rodríguez (eds.), Traducción subordinada II: el subtitulado (inglés – español/galego). Vigo: Universidad de Vigo, pp. 47-67.

— (2012). «Clearing the smoke to see the screen: ideological manipulation in audiovisual translation». [Online] META, 57/2, pp. 279-293. Available from: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013945ar. [Accessed: 17th November 2013].

Díaz Cintas, J. and Remael, A. (2007). Audiovisual Translation: Subtitling. Manchester: St Jerome.

Dooling, R. (1996). Blue Streak: Swearing, Free Speech, and Sexual Harassment. New York: Random House.

D’Ydewalle, G., Van Rensbergen, J. and Pollet, J. (1987). «Reading a message when the same message is available auditorily in another language: the case of subtitling». In J. K. O’Regan and A. Lévy-Schoen (eds.), Eye Movements: From Physiology to Cognition. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, pp. 313-321.

Fernández Fernández, M. J. (2006). «Screen translation. A case study: the translation of swearing in the dubbing of the film South Park into Spanish». [Online] Translation Journal 10/3. Available from: www.bokorlang.com/journal/37swear.htm. [Accessed : 23rd September 2012].

Filmer, D. (2014). «The ‘gook’ goes ‘gay’. Cultural interference in translating offensive language». [Online] Intralinea 15. Available from: www.intralinea.org/archive/article/the_gook_goes_gay. [Accessed: 20th January 2014].

Gentzler, E. (2004). Contemporary Translation Theories. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Hughes, G. (1991/1998). Swearing: A Social History of Foul Language, Oaths and Profanity in English. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

— (2006). An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-Speaking World. New York and London: M.E. Sharpe.

Jay, T. B. (1980). «Sex roles and dirty word usage: a review of the literature and a reply to Haas». [Online] Psychological Bulletin 88/3, pp. 614-621. Available from: www.mcla.edu/Undergraduate/uploads/textWidget/1457.00013/documents/jay2.pdf. [Accessed: 5th May 2013].

— (1992). Cursing in America: A Psycholinguistic Study of Dirty Language in the Courts, in the Movies, in the Schoolyards, and on the Streets. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

— (2009). «The utility and ubiquity of taboo words». Perspectives on Psychological Science 4/2, pp. 153-161.

Lefevere, A. (1984). «The Structure in the Dialect of Men Interpreted». Comparative Criticism 6, pp. 87-100.

— (1992). Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. London and New York: Routledge.

McEnery, T. (2006). Swearing in English. Bad Language, Purity and Power from 1586 to the Present. London and New York: Routledge.

Merino, R. (2007). Traducción y censura en España (1939-1985). Estudios sobre corpus TRACE: cine, narrativa, teatro. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco.

Montagu, A. (1973). The Anatomy of Swearing. London and New York: Macmillan and Collier.

Murray, J., Bradley, H., Craigie, W. and Onions, C. (1884). Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robson, C. (2011). Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings (3rd edn). Chichester: Wiley.

Scandura, G. L. (2004). «Sex, lies and TV: censorship and subtitling». [Online] META, 49/1, pp. 125-134. Available from: id.erudit.org/iderudit/009028ar. [Accessed: 26th December 2012].

Vinay, J-P. and Dalbernet, J. (1958/1995). «A methodology for translation». In L. Venuti (ed.), 2000. The Translation Studies Reader (2nd edn). London and New York: Routledge, pp. 84-93.

Wajnryb, R. (2005). Expletive Deleted: A Good Look at Bad Language. New York: Free Press.

FILMOGRAPHY

Flor de mi secreto, La [Flower of my Secret, The]. (1995) Film. Directed by Pedro Almodóvar. [DVD] Spain: CiBy 2000 and El Deseo S.A.

Gran Torino. (2008) Film. Directed by Clint Eastwood. USA: Matten Productions, Double Nickel Entertainment, Gerber Pictures, Malpaso Productions, Media Magik Entertainment, Village Roadshow Pictures, WV Films IV, and Warner Bros.

Reservoir Dogs. (1992) Film. Directed by Quentin Tarantino. USA: Live Entertainment and Dog Eat Dog Productions Inc.

South Park. Bigger, Longer & Uncut. (1999) Film. Directed by Trey Parker. USA: Comedy Central Films, Comedy Partners, Paramount Pictures, Scott Rudin Productions, and Warner Bros.

1 Motion Picture Association of America. Available from: <www.filmratings.com>. [29 September 2012].

2 Every subtitle number is provided along with its Time Code Reader (hours:minutes:seconds:frames). The strategies employed are abbreviated as: literal translation (LT), substitution (SUBS), transposition (TRAN), omission (OMS), and reformulation (REF).

3 Online Etymology Dictionary. Available from: <www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=jap&searchmode=none>. [3 November 2012].