Audio describing the exposition phase of films. Teaching students what to choose

Aline Remael y Gert Vercauteren

University College Antwerp

La audiodescripción se está introduciendo progresivamente en los productos audiovisuales y esto tiene como resultado por una parte la necesidad de formar a los futuros audiodescriptores y, por otra parte, formar a los formadores con unas herramientas adecuadas para enseñar cómo audiodescribir. No cabe la menor que como documento de partida para la formación las guías y normas de audiodescripción existentes son de una gran utilidad, sin embargo, éstas no son perfectas ya que no ofrecen respuestas a algunas cuestiones esenciales como qué es lo que se debe describir cuando no se cuenta con el tiempo suficiente para describir todo lo que sucede. El presente artículo analiza una de las cuestiones que normalmente no responden las guías o normas: qué se debe priorizar. Se demostrará cómo una profundización en la narrativa de películas y una mejor percepción de las pistas visuales que ofrece el director puede ayudar a decidir la información que se recoge. Los fundamentos teóricos expuestos en la primera parte del artículo se aplicarán a la secuencia expositiva de la película Ransom.

Palabras calve: audiodescripción, accesibilidad, traducción audiovisual.

Ever more countries are including audio description (AD) in their audiovisual products, which results on the one hand in a need for training future describers and on the other in a need to provide trainers with adequate tools for teaching. Existing AD guidelines are undoubtedly valuable instruments for beginning audio describers, but they are not perfect in that they do not provide answers to certain essential questions, such as what should be described in situations where it is impossible to describe everything that can be seen. The present article looks at one such situation, the exposition phase of films, and tries to show how a better insight into film narration and a better perception of the many visual clues used by the filmmaker might help audio describers decide on what information to prioritize. The audio description of the expository sequence of the movie Ransom is studied and the principles set forth in the theoretical part are applied to it.

Key words: audiovisual translation, accessibility, audio description, film narration.

0. introduction

In some European countries, i.e., the United Kingdom, Spain and Germany, the practice of audio description (AD) is fairly well established, resulting even in the gradual emergence of national AD traditions (Bourne & Jiménez, forthcoming). In Flanders, by contrast, the practice is still in its infancy, but thanks to the lobbying of groups representing blind people and people with a visual impairment, the first Flemish and Dutch TV programmes and feature films are now being described both for dvd and cinema.1 The Higher Institute for Translation and Interpreting of University College Antwerp2 has decided to support these efforts by integrating AD in the special option in audiovisual translation (AVT) of its new master in translation studies from October 2007. Meanwhile, the department is developing test cases. More particularly: a number of students are describing films which are then presented to small groups of volunteers from the target (blind) audience for feedback. Upon completion of the AD, the finished product is used by these target audiences locally. In other words, the department’s interest in audio description is mainly didactic and aimed at providing students with the tools they need to create adequate descriptions. So far, the students have used the guidelines drawn up by Remael (2005), which are based on different existing guidelines, the author’s participation in AD workshops and limited personal experience. However, none of the existing guidelines is ideal as a didactic tool, and that actually includes ours.

Any translator will always have to find solutions to specific problems while translating. Any subtitler, for instance, who is confronted with conflicting constraints imposed by, say, the rhythm of speech and the syntactic structure of writing, will have to evaluate different solutions based on the context in which a particular utterance occurs. Students, however, are translators to be and they need guidelines or ‘rules’ that help them make decisions and teach them how to evaluate different translation choices. That is why some of the instructions in existing AD guidelines remain too vague or leave too many questions unanswered to be useful from a didactic point of view. In other words, it is up to us, teachers, to hand students a model that can at least serve as a starting point.

In the first instance, we believe that this should be a model that helps students analyse what the central message of the source text3 is, and how it conveys this message. This is in line with well-established approaches in translation studies, such as the translation-oriented text analysis proposed by Nord (1988/91). In the present situation, however, the analysis is not applied to verbal text organization at sentence level or above. The object of analysis is a filmic text consisting of highly organized images in interaction with other sign systems. Therefore, the model should teach students where and how to look for narratively significant visual clues in the formally complex message they are about to translate. In a second stage, these visual clues will indeed have to be rendered aurally if the blind target audience is to enjoy a film originally conceived for a seeing public. Obviously, the didactic model or guidelines we have in mind, need not necessarily be used by professional describers or translators. Ideally, professional describers will apply the strategies they have learnt as students or beginning describers intuitively. Indeed, professional translators in any field work under time pressure and usually have no time for detailed and meticulous analyses. However, as Chaume (2004: 13) writes, discussing models for research-oriented AVT studies:

… if we wish the model to be useful in the teaching of translation, it should be able to a) show translators the tools (translation strategies and techniques) with which they will be able to confront their task, and b) reduce to a minimum the need for improvisation, but not for creativity.

Since more research is needed into the issues that should inform film analysis aiming at the production of adequate audio descriptions, the model discussed below is based only on concepts from film studies and screenwriting manuals focusing on how film narrative works. We believe that students must first be taught how to identify crucial filmic clues meant for the original target public, clues that might be lost on a public of blind people or people with serious visual impairment. Having identified which narratively significant visual clues the film provides, the students should then examine how, when and if these clues can be included in their AD4.

1. existing audio description guidelines

Vercauteren (forthcoming), gives a survey of existing guidelines and the topics they tackle. In his article, which deals with the writing of AD for recorded audiovisual material only, he pinpoints weak and/or ambiguous passages and indicates possibilities for further research, with a view to establishing international standards, eventually. Vercauteren writes:

To counterbalance the wide variety of source material in this category of descriptions, the part of the guideline concerning the practical principles could be further subdivided into two parts, as is also suggested by the English standard [the ITC Guidance on Standards for Audio Description]: one general section dealing with guidelines that are valid for any kind of programme, and a set of modules dealing with rules and problems related to specific categories of programmes (such as musicals, soap operas, children’s programmes, etc.).

As matters stand, all guidelines tackle the following questions to some extent, says Vercauteren:

1) What should be described?

2) When should it be described?

3) How should it be described?

4) How much should be described?

However, even with regard to the first question («what should be described»), there is no full agreement. Contrary to, for instance, the official English Standard and the Flemish guidelines drawn up by Remael, the German guidelines (Benecke, 2004) and the Spanish une standard for audio description do not provide any information on what to do with sounds, or text on screen. All the same, says Vercauteren, it seems self-evident that guidelines should include instructions relating to the description of:

Images: where, when, what, who.

Sounds: sound effects (difficult to identify), song lyrics, other languages than programme’s.

Text on screen: logos, opening titles, cast lists, credits, signs (subtitled).

The problem from a didactic point of view is the lack of agreement on the extent to which all of these elements should effectively be included.

In her article on audio description in the Chinese world, Yeung (forthcoming) describes the reactions of students taking her own innovative audio description course, saying: «One of the major problems students encountered is the selection of material to describe [...]». Indeed, the first discussions with beginning AD students in Antwerp seem to point in the same direction. In some scenes it is impossible to describe all the above-mentioned items and a selection must therefore be made. The existing guidelines all state that it is important to prioritize information, but they offer little or no help when it comes to deciding what information should get priority. Hence, the crucial question: what is most relevant for the production at hand? As many guidelines indicate, genre may offer some help in the decision-making process and the «WHAT» question therefore — in our view — belongs both in general and more specific sections of AD-guidelines. Since today’s film directors love mixing genres, however, genre alone cannot solve all problems. In what follows we shall limit ourselves to questions relating to what should be described in terms of visual narration, because it is prioritized by (technical) filmic narrative techniques.

2. research stages

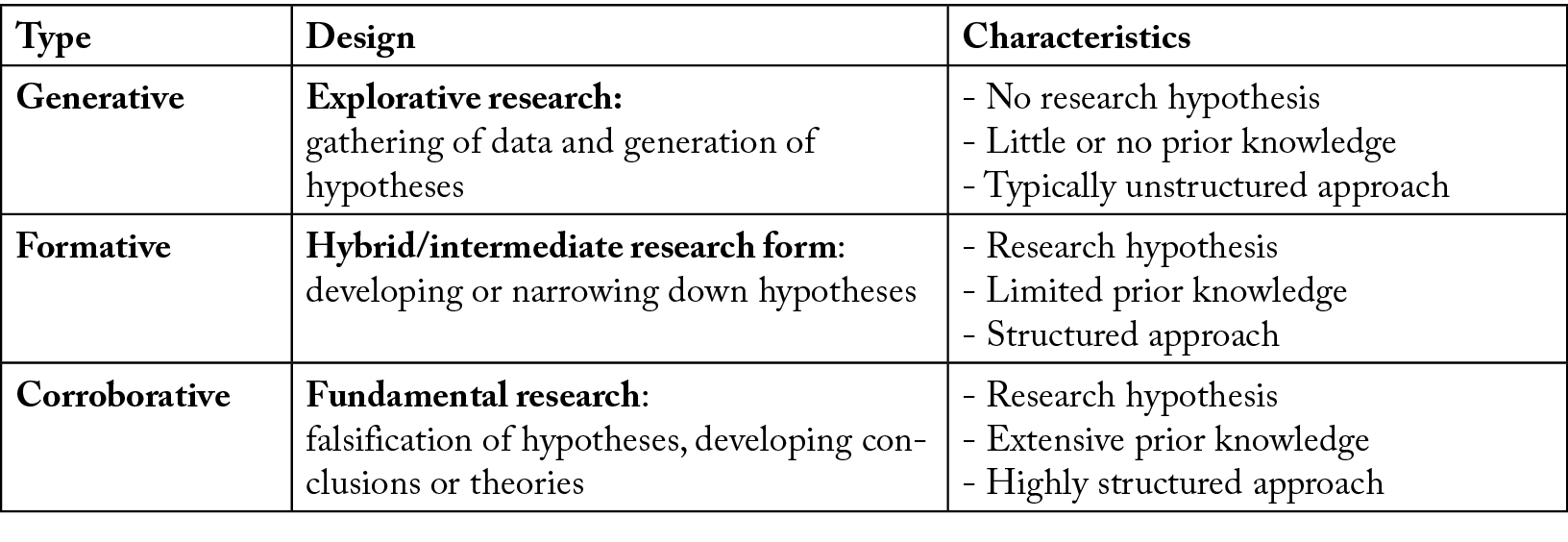

In an article dealing with methodological issues in Community Interpreting, Erik Hertog et al. (forthcoming) suggest a classification of research phases that seems quite useful for research in AVT as well. It might help combat the tendency of some scholars to stick to case studies rather than undertake more fundamental and quantitatively significant research.

We insert it here, because our research into the design of models for the teaching of AD is still at an early stage, i.e. at the stage of «Explorative research».

In order to test our first, intuitive ideas, we decided to try them out on the exposition phase of films because they are so densely packed with information (cf. infra). This means that at this point, we are merely «gathering […] data» and «generating […] hypotheses». In a next stage we hope to be able to narrow them down, in the «formative stage» of our research; and eventually, in the «corroborative stage» we should be able to proceed to the «falsification of hypotheses», as well as the development of «conclusions or theories». At present we are in phase one, and we are therefore doing little more than offering some ideas for discussion, using the detailed analysis of one film by way of example, not by way of ‘proof’.

3. the exposition phase in films

A quick survey of the first 10 minutes of a number of randomly chosen films (10) with AD5 shows that problems relating to the impossibility to describe everything one might want to describe, often occur in the exposition phase. This is why expositions are especially interesting from a didactic point of view, but before we can tackle the issue of how to select information, a word about the way in which film narrative works, is required.

3.1 How (film) narrative works

With respect to narratives generally and film narrative more in particular, Branigan (1992: 4) writes that it

… can be seen as an organisation of experience which draws together many aspects of our spatial, temporal, and causal perception. In a narrative, some person, object or situation undergoes a particular type of change and this change is measured by a sequence of attributions which apply to the thing at different times. Narrative is a way of experiencing a group of sentences or pictures (or gestures or dance movements etc.) which together attribute a beginning, middle, and end to something.

The author states that it is only because the reader or listener/viewer uses clues in the text to establish these attributions that narrative works. The story is constructed by the viewers, readers or listeners on the basis of the plot, or on a lower level, by making use of clues that they pick up, link up and interpret, inferring information that is not explicitly given6. A film narrative, like any narrative, has a beginning, middle and end (even if these are not presented in that order in the plot), but a film is also sequential. As Gulino (2004: 3) writes, films are composed of sequences, segments of 8 to 15 minutes, with their own internal structure. This structure is similar to that of the whole film (with beginning, middle and end), but some issues are only partially resolved and new issues are opened for subsequent sequences to build on. In other words, «big films are made out of little films», and the exposition is one such little film.

The issue at stake with the narrative clues provided by film is, of course, that film is a visual medium par excellence that offers clues for a viewing and hearing public with a specific (if variable) type of experience of the world. Moreover, no narrative is ever re-constructed or interpreted by different readers or viewers in the same way. Somers and Gibson (qtd in Baker, 2006: 71) argue that narratives are «constructed according to evaluative criteria that enable and guide selective appropriation of a set of events or elements from the vast array of open-ended and overlapping events that constitute experience.» This is certainly the case for viewers with an experience of the world that differs fundamentally from that of cinema’s seeing target audience.

All audio describers can therefore hope to do is provide clues that will allow their special target audience to construct a story that makes sense and offers them satisfaction. In order to accomplish this, the describer must allow the blind or visually impaired public to make the necessary inferences from the plot of the film, in order to construct its entire story. In most mainstream cinema, narration is motivated «compositionally» (Bordwell, Staiger & Thompson, 1994 [1985]: 24), that is, it is composed of scenes and sequences that build on each other and are causally linked by the characters’ actions. Still, some film narratives are more communicative than others, meaning that some are more explicit, whereas others require a greater (re)construction effort on the part of the viewer.

In short, narrative ‘clues’ is what the describer should be looking for, and he should be doing this as an ‘informed’ viewer. The describer should not merely be watching the story unfold, but should be on the lookout for the clues that help the story unfold in the light of his or her knowledge of how film works. In a later stage, the audio described film so produced will be a new film with sufficient clues for a non-seeing audience to construct their own version of it.

3.2 The what and how of filmic beginnings

Filmic beginnings: what

Since the exposition phase is one little story within the bigger story of the movie, as we pointed out above, any strategies applied at this stage, will or can also be used elsewhere in any film. Film beginnings are interesting and challenging because they contain a wealth of narratively important clues (visual, verbal, non-verbal aural clues, clues about the film genre and credits).

In classical Hollywood cinema, Bordwell et al. point out, the film’s beginning is where the narrative is most apparent (and where clues accumulate), because of the beginning’s expository functions. Once all required information has been given, narration will recede into the background (Bordwell, Staiger & Thompson, 1994[1985]: 27). This means that AD will more or less automatically be more prominent in the opening scenes as well.

Indeed, identifying what a good filmic opening should do in screenwriting terms, Schellhardt (2003:74) writes the following.

The first ten minutes of every movie determine what an audience expects from the remaining two hours. A story’s set-up determines, in large part, how your story will unfold. And if it doesn’t suggest the movie to come, it should. Here are a few things a strong opening should do:

- Introduce your main character

- Establish a routine or pattern of life

- Suggest a conflict that may break that routine or pattern

- Introduce your subplots and suggest their conflicts

- Set the tone and style of the piece

- Suggest a villain or opposing force in the story

- Suggest something important at risk

- Raise a compelling question.

In other words, an audio describer who can tackle this, can tackle anything.

Filmic beginnings: how

Like any other film sequence, the exposition makes use of all of the semiotic channels available to visual narration. These are summarized by Mehring (1990) as: the static images, filmic time (including e.g., montage), filmic space, elements of motion, imagery (e.g., associative images) and sound. For the purposes of this exploratory paper, we will limit ourselves to visual content as conveyed by means of the twelve strategies discussed by Lucey (1996: 98-106) in an article titled: «Twelve strategies for enhancing visual content».

In his paper, which is also written from a didactic viewpoint, the author describes the main strategies that can help beginning filmmakers to make the story they want to tell stronger and more visual. This obviously means that these strategies can also be used to create strong openings, if they are combined with the what of film openings, detailed above.

The different strategies distinguished by Lucey are: visuals from action, grand images, visual metaphors, symbols, continuity visuals, mood and set-up visuals, wallpapering, walk-and-talk-scenes, business, image systems and settings. It is our contention that if they work for beginning filmmakers, they will also work for beginning audio describers trying to identify relevant visual clues. Having identified what is an essential visual clue, they can then go on to investigate whether there is time and space to include it in their descriptions.

Visuals from action

Some films are driven by character, some by action. The former rely heavily on dialogue, whereas the latter must make use of the exploits of their characters to further the story line (Lucey, 1996: 98). There are almost as many examples of visual narration conveyed through action, or «visuals from action», as there are scenes in action films. One good example occurs in the opening scenes of V for Vendetta. The masked protagonist V, a sci-fi Guy Fawks figure, rescues Evey, the girl who will later become his accomplice, from two covert representatives of the authoritarian government, men who threaten to arrest her because she is disregarding the curfew. He gets rid of Evey’s assailants in a spectacular fight, using daggers to slit his opponents’ throats. The daggers in themselves are part of his unusual appearance (he wears a mask, a large black cape and hat) suggesting he is a figure from a different day and age.

Grand images

«Grand images» are used throughout films. The term refers to beautiful panoramic views, cityscapes, etc. In the exposition phase, such grand opening scenes often serve to show the setting for the action. Both Ransom and Die Hard with a Vengeance, for instance, open with a view of the New York skyline.

Visual metaphors

«Visual metaphors» are visuals that have a thematic value or that are used to suggest character traits. One of the main characters in the Belgian movie Karakter is the implacable bailiff Dreverhaven. The long black coat he always wears, together with the black hat covering part of his face, can be regarded as a visual metaphor for his dark and ruthless nature.

Symbols

«Symbols» are visual elements that represent a need, loss, emotion, or a value that reflects on the story of a character. In Ransom, an electric fire in the basement that will eventually become a temporary prison for the protagonist’s son Sean Mullen, symbolizes the cold, impersonal nature and poverty of the surroundings in which the boy’s kidnappers operate. By way of contrast, the cosy fireplace in the Mullens’ living room (cf. below) suggests the warm family atmosphere reigning at their house.

Continuity visuals

«Continuity visuals» refers to shots that show characters travelling from one location to another, used to «reveal scenery that orients the audience to terrain, architecture, or whatever has interest» (Lucey, 1996: 101-102). In Pretty Woman the protagonist Edward, a rich business man, drives away from a party in Beverly Hills after a phone call. He keeps on driving, without paying much attention to where he is going, and ends up in a rather rundown neighbourhood of LA where he meets Vivian, the prostitute he will fall in love with. As Edward is driving, the camera offers views of different LA neighbourhoods and the viewers register whatever visuals appear on the screen (e.g., prostitutes parading along the street).

Mood and setup visuals

«Mood and setup visuals» are visual elements used to set the stage and prepare the audience for a dramatic scene. A typical example would be the exploration of a haunted house. This kind of visual makes the audience often feel apprehensive before the character is aware of the danger. In Ransom, the exploration of the basement (mentioned above), with the dim staircase, the ill-lit room, the metal bed and the handcuffs hanging from its bars, sets the stage for the kidnapping that is the core event setting off the narrative.

Wallpapering

«Wallpapering» is an innocuous way of using visual details to convey information. In Pretty Woman, we know that Edward is a businessman, but it is the expensive furniture and the grandeur of the hotel penthouse where he takes Vivian after they first meet, that tells us how rich he really is.

Walk-and-talk scenes

As the name suggests, «walk-and-talk scenes» are scenes in which characters talk as they pass through relevant settings. In some cases, the characters can also interact with the background they walk through. This happens in the opening scene of Ransom, discussed in greater detail below. As the guests pass from the balcony into the house, the camera gives the viewer a good idea of the lay-out of the luxurious flat.

Business

«Business» refers to physical activities that characters perform as they converse. These activities too are informative and promote verisimilitude. In the breakfast scene in Derailed, Charles and Deanna are helping their young teenage daughter Amy write a book report. As they are talking over breakfast, Deanna measures Amy’s blood sugar level, fills a syringe and hands it to Amy, who injects it. All this «business» during the conversation suggests that Amy has diabetes.

Settings

When the «settings» of a scene are «skilfully selected, positioned, and lighted, they can offer interesting visual content» (Lucey, 1996: 104). In the exposition phase of Shall we Dance, middle-aged protagonist John Clark drives home by train and we see him sitting at the window of his carriage. From this window he sees a young woman in a dance school (identified by a banner), also framed by a window as she is dancing. The setting, i.e., the train and the school, the fact that both characters are framed by a window and that the woman is dancing, indicates that these two characters will be the protagonists of the film, but also that they probably have very different lives. At the same time the title theme of the movie, dancing, is introduced though action.

Image systems

«Image systems» are recurrent visual motifs that work as a thematic point or metaphoric content. In The Hours, the three women protagonists are connected by the novel one of the protagonists of the film, Virginia Woolf, has written: Mrs Dalloway. The first sentence of this novel goes «Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself» (Woolf, 1925/1976: 5). Not only is the sentence repeated on various occasions in the film, the three women regularly either buy flowers or are given flowers.

Visual triggers

«Visual triggers» are interesting images that move the script forward or create suspense. Often such visual triggers are shown in close up. In the opening scene of Karakter, Dreverhaven’s son Katadreuffe enters his father’s office in a fit of rage and plants a knife in the office desk, right in front of Dreverhaven. The knife is shown in close up and will later turn out to be the weapon that killed Dreverhaven.

The examples given for each of the above methods for visual story-telling were all taken from films that are available on dvd with AD (cf. footnote 5). In the next stage of our research we will investigate to what extent the ADs of the said films indeed incorporate the visual clues thus highlighted. For now, we will demonstrate by way of examples from one film, Ransom, how awareness of filmic story-telling methods can direct beginning audio describers in their search for relevant events to select for description. We do not believe that an intensive course in film studies is required to achieve this. All mainstream films combine the visual story-telling techniques Lucey proposes to accomplish the elliptic story-telling that is so typical of film (i.e., using the «plot» to tell the «story»). More concretely, these devices are therefore used for: introducing new data, maintaining the linear progression of the story (from given data), adding focus, juxtaposing events or characters and/or inserting meaningful repetition. The juxtaposition of events may serve to introduce contrast or suggest similarity, for instance, or to indicate the convergence or divergence of two fictional lives. Repetition can be used to confirm a piece of information, or a character trait introduced at an earlier stage, but it is also part and parcel of the redundancy of film narration. This rather limited number of operations is combined with the visual clues highlighting certain events as described by Lucey, and provides insight in the links between them. Having identified these, the audio describer should (ideally) transpose them to tell his/her new verbal rendering of the mostly visual story that (s)he is helping the target audience construct77.

4. a first example: Ransom

(ron howard 1996)

4.1 The WHAT and HOW of the exposition

The entire expository sequence of Ransom takes approximately eight minutes, but describing all the events of this first sequence of the film is quite impossible. Ideally, the reader should be able to watch it. Ransom is a mixture of action, crime, drama and thriller. Its protagonist is Tom Mullen, an extremely rich airline owner, who lives in uptown Manhattan with his wife Kate and son Sean. The latter is kidnapped and at first Tom is willing to pay the two million dollar ransom the kidnappers are demanding, but when the drop goes wrong, he turns the ransom money into a bounty on the head of the kidnapper8.

The opening scene of the film is a textbook example of «the things a strong opening should do» (Schellhardt, 2003: 74). The main character, Tom Mullen, is introduced and his «pattern of life» as a successful, rich businessman, and happily married father of a young son, is visually conveyed. That this routine will soon be disrupted is suggested by cuts from scenes in the Mullens’ home to parallel action by an anonymous man in a dreary basement, where preparations are being made for what could be a kidnapping (as is suggested by the title of the film Ransom). Towards the end of the eight minute introductory sequence a subplot and additional conflict are introduced when a journalist addresses Tom Mullen (at a party he has organised at his uptown flat), suggesting he may be involved in a bribery scandal. This flaw also makes the protagonist more vulnerable. The title R-A-N-S-O-M which appears on the screen gradually, like the jagged pieces of a puzzle, the different locations in combination with the music (percussion), and the intrigue planted by the journalist, suggest «the style of the piece», whereas they also introduce various «opposing forces». The obvious affection between Tom his son Sean (who knows nothing of his father’s darker dealings), as well as the protagonist’s wealth, indicate that «something important» may be «at risk». The partially ambiguous actions going on in the cellar, «raise a compelling question», which is not ‘if’, but rather ‘how’ and ‘when’ the crisis will develop.

This is, minimally, what must be conveyed to the new target audience. However, again, like any other type of translation, AD is «metonymic» (Tymoczco, 1999); it cannot nor does it need to convey everything the source text conveys. Still, some of the narrative strategies detailed by Lucey (1996), i.e. ‘how’ this story is told, figure prominently in the expository sequence of Ransom and are indicative of ‘what’ is crucial information both from a short-term and from a long-term narrative perspective . Below, a few examples are discussed in detail, the AD figuring on the dvd of the film is examined, and contrasted with an alternative AD.

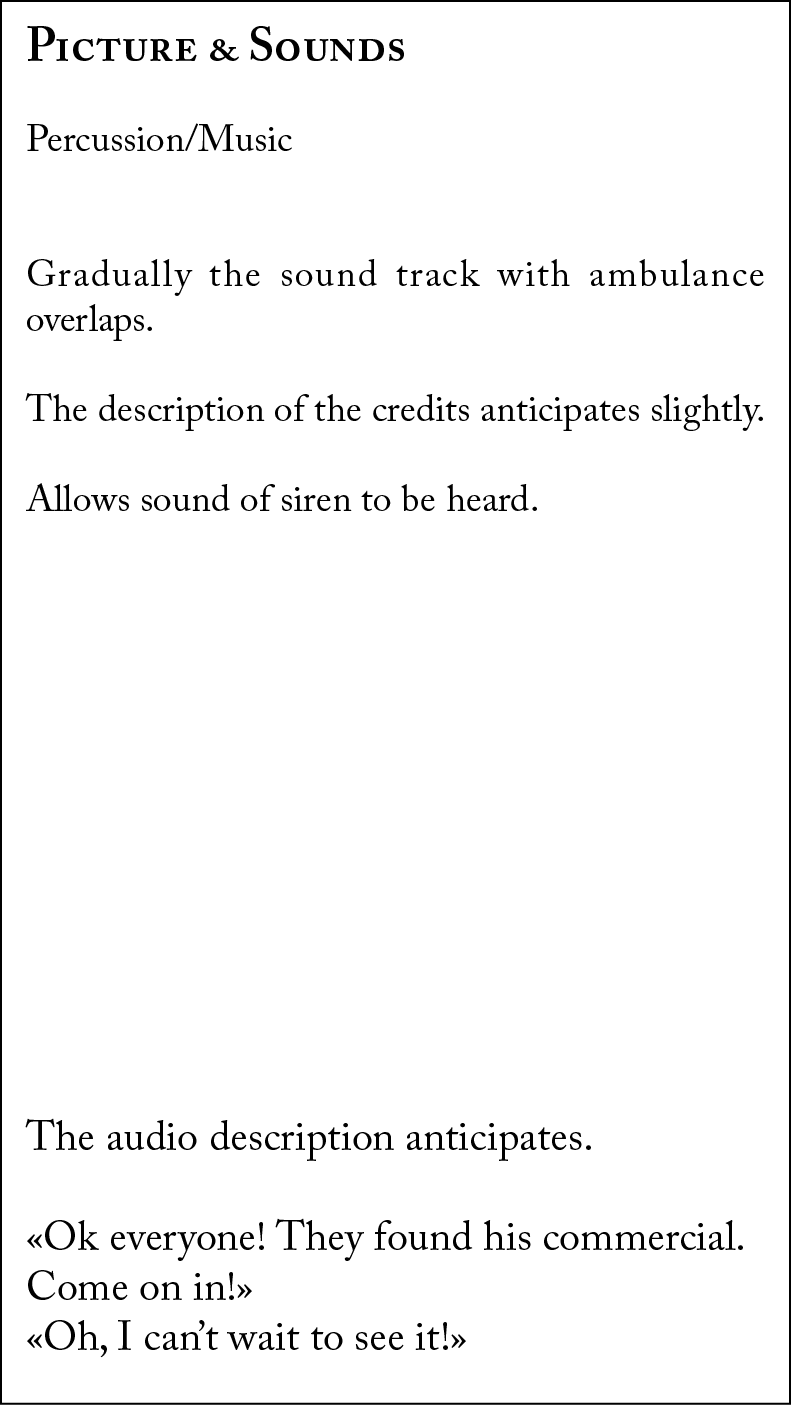

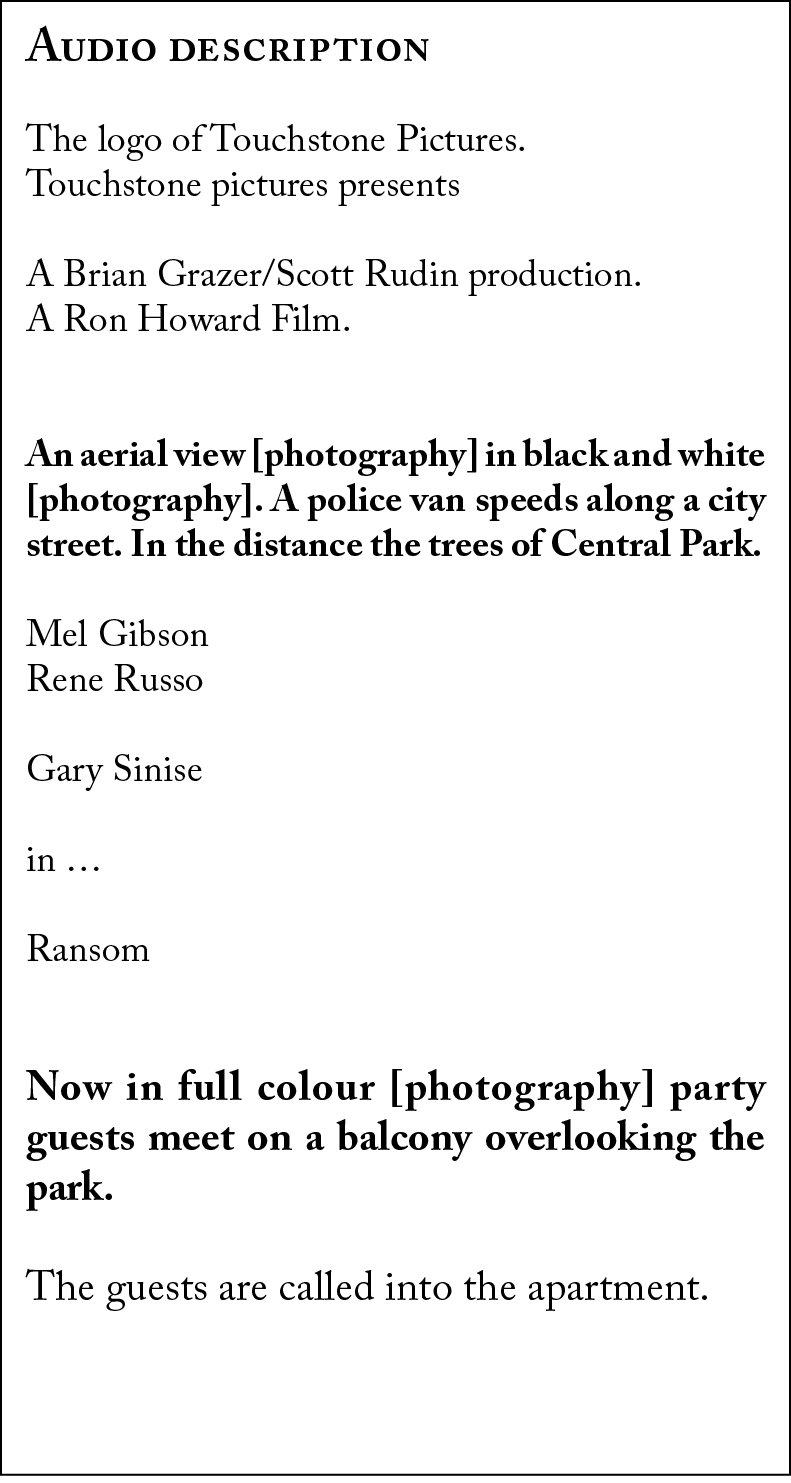

1) Grand images, visual metaphor, walk and talk scene/ linear progression

At the very beginning of the film, slow, rhythm music mixes with city sounds (a siren is prominent), while the Touchstone Pictures logo is still on screen and credits begin to appear. Then follows a shot tracking cars and an ambulance from which the siren comes, speeding along a street along Central Park, NYC. The music gradually gains prominence then recedes as the camera draws attention to the images instead: a long shot of Central Park and surrounding streets. This is uptown NYC, a wealthy neighbourhood. The image gains prominence over the sounds. Like the pieces of a jagged puzzle, the word RANSOM, the title of the film, is assembled on the screen. The photography turns from black and white to colour. Voices suggesting simultaneous conversations between several people are superimposed on the city noises and music as people walk into the picture. There is a party going on at a flat in a building overlooking the park. Some of the guests are on a terrace.

The original AD consists of three parts, one deals with photography (the aerial view, black and white), two with the narrative (i.e. the speeding ambulance and the location). In the alternative AD the reference to «black and white» film has been dropped, but more narrative information has been included. Most importantly, the sentence «A police van speeds along a city street. In the distance the trees of Central Park», now reads « […] an ambulance9 speeding along an uptown Manhattan street near Central Park». The city street is identified as being close to Central Park, which is where the flat of the Mullens’ is located. The trees of Central park are only «in the distance» because the film begins with a grand opening, but this is narratively functional, as all filmic shots in mainstream feature films are. In other words, central park is in the distance because film narration traditionally starts with a long shot and then continues with a closer shot to determine a location (in this case the people on the terrace). This location is important: upper Manhattan, near Central Park serves as a visual metaphor for whoever lives here is rich, as any viewer (or certainly many viewers) raised with American films or TV series would know. This visual piece of information should therefore be conveyed more unambiguously.

The scene continues chronologically, or in a linear fashion (cf. above), going into the details of the party on the balcony as people talk, move around, and reveal more of the local setting in a «walk and talk scene». In this case, it is narratively more important, building on the alternative AD so far, to reveal that «Evening falls. Party guests meet on a balcony overlooking the park», than to refer once again to the photography stating, «Now in full colour party guests meet on a balcony overlooking the park».

2) Business / the sound track

The promotional video that the guests at the Mullens’ party watch allows for a special example of business. This film within the film informs the viewers of Tom’s professional career, advertising Mullen’s success, but while everyone is watching the video, father and son exchange several glances. This too is a form of action. Glances are crucial in cinema, and they are usually supported by shot reverse shot techniques, as is the case here. The silent exchanges between the two characters may indicate that they do not take the video film too seriously, they certainly suggest a good rapport between the two, which is important because it means that something good may be «at risk». Not only does the recorded AD fail to mention this relationship, it does not identify the boy’s presence in the room until much later. That is why «His young son watches, smiling», has been added in the alternative description. Narrative motivation warrants this inclusion and warrants breaking another AD guideline, i.e. that the sound track should be respected whenever possible. At this point, the sound track consists predominantly of party noises which the new target audience has had ample time to identify.

3) Settings / narrative focus through repetition, convergence

The Mullens’ flat has an open-plan kitchen. It is part of the luxurious setting, giving the film extra visual content, while doubling up as a framing device. The kitchen counter allows the camera to connect people as well as to set them apart. Such narratively relevant framing twice involves the young waitress at the party who will later turn out to be one of Sean’s kidnappers and whose own surroundings contrast sharply with the luxurious ones of the Mullens’. The first time, the young woman is framed by a window as the camera films the party from the outside looking in. The second time, she is in the open-plan kitchen preparing trays. She is now filmed in close up and exchanges glances with Sean, without speaking to him. The film thereby focuses on the waitress twice, once inconspicuously with a long shot, then explicitly, connecting her with Sean into the bargain.

The recorded AD duly mentions the waitress twice, but fails to indicate that she is one and the same person, which gives less narrative weight to the character. And yet, the link made by the visual narration can easily be made through the language of the audio description as well. If one replaces the indefinite pronoun «a» in «From the open-plan kitchen a dark-haired young waitress glances across at the boy», by the definite article «the» this indicates a previous mention, and therefore a character we have already met. This is not telling the blind target audience more than the seeing audience, or patronizing them, it is merely rendering an existing visual link verbally. What is more, even if this verbal link were more explicit, this could compensate for others that cannot be rendered. In audio description as in various other forms of AVT, compensation is an important tool. The recorded AD does take visual links into account (e.g. the look the waitress and boy exchange), but it does not do so consistently.

4) Mood and setup visuals, symbols/ juxtaposition ~contrast and convergence

As was pointed out in our discussion of mood and setup visuals, the way the camera scans the basement in which Sean will eventually be locked up, sets the stage and prepares the audience for «a dramatic scene». This is achieved by contrast: the settings at the Mullens’ residence versus the dreary environment of the basement. Moreover, the narrative makes an explicit link between the two through the visual contrast that sets off the electric heating in the basement, symbolizing the cold, impersonal nature and poverty of the surroundings in which the boy’s kidnappers operate, with the cosy open fire in the Mullen’s warm and luxurious living-room. However, the fire and the heater also have something in common: they are sources of (a very different) kind of warmth and therefore also connect the two scenes, underlining the one will have some impact on the other.

In the original AD, the two settings are contrasted, but the link between the fire and the heater is not made. In order to indicate that the narrative has moved from the basement back to the flat, the recorded AD says «Back at the party». The party noises, however, already indicate this, and the alternative AD, «A hand switches on an electric fire.

An open fire place. Tom Mullen speaks to his son Sean», provides the visual connection. This is especially important since it is Sean who is standing next to the open fire, and Sean who will end up in the room with the heater.

5. further research

The recorded AD probably functions well enough, but it certainly could have been more consistent. Occasionally ‘better’ choices could have been made, in the sense of more narratively relevant. The increased focus on visual filmic clues and narrative techniques underlying the production of the alternative AD seems to yield a more adequate result at least in some of the scenes examined and also helps detect flaws in the recorded version. Appendix 2 offers some additional examples.

The recorded dvd of Ransom appears to be a more ‘superficial’ one than the alternative version, at least in those instances where it describes images without taking their underlying function into account. Example 1) shows that preference could have been given to narratively relevant information over concerns related to photography. Example 2) explores the meaning of Lucey’s term business, the relevance of action going on simultaneously with other action, or talk. In 3) settings and the technique of repetition are shown to give focus and provide links that can be rendered verbally and 4) exemplifies how the contrast and convergence conveyed through juxtaposition in combination with Mood and setup visuals, as well as symbols can be captured by exploiting a similar kind of juxtaposition in words.

For further reference we would like to name the second AD a «structural» AD, and oppose it to «surface» ADs, thereby drawing attention to the «understructure» of film, like many a screenwriting manual does (cf. above, e.g. Brady & Lee, 1990). Further research will hopefully indicate how useful an approach focusing on the narrative techniques underlying the pictures, really is. Can it contribute to more consistent and more efficient audio descriptions? Is it a useful method for teaching beginning audio describers what to describe – possibly even how? The use of the exposition sequence of Ransom has certainly shown that filmic beginnings are ideal teaching material, both for analysing existing AD’s and for teaching students what to prioritize. In accordance with our methodological research aims outlined in section 2, however, our first aim must now be to repeat the test carried out for this article on a much larger number of audio described films.

Recibido en diciembre 2006

Aceptado en enero 2007

6. works cited

aenor (2005). Norma une: 153020. Audiodescripción para personas com discapacidad visual. Requisitos para la audiodescripción y elaboración de audioguías, Madrid: aenor.

Baker, M. (2006). Translation and Conflict. A Narrative Account, London & New York: Routledge.

Benecke, B. & Dosch, E. (2004). Wenn aus bildern Worte Werden. Durch Audio-Description zum Hörfilm, München: Bayerischer Rundfunk.

Bordwell, D. & Thompson, K. (1990). Film Art. An Introduction, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bourne, J. & Jiménez, C. (forthcoming). «From the Visual to the Verbal in Two Languages: a Contrastive Analysis of the Audio Description of The Hours in English and Spanish». In: Díaz Cintas, J., Orero, P. & Remael, A. (eds.). Media for All. Accessibility in Audiovisual Translation.

Bordwell, D., Staiger, J. & Thompson, K. (1994 [1985]). The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, London: Routledge.

Brady, B. & Lee, L. (1990). The Understructure of Writing for Film and Television, Austin: University of Texas Press.

Branigan, E. (1992). Narrative Comprehension and Film, London & New York: Routledge.

Chaume, F. (2004). «Film Studies and Translation Studies: Two Disciplines at Stake in Audiovisual Translation». META xlix, 1, pp. 12-24.

Gulino, P. J. (2004). Screenwriting. The Sequence Approach. The Hidden Structure of Successful Screenplays, New York & London: Continuum.

Nord, C. (1988/91). Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis, Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Remael, A. (2005). Audio description for recorded TV, Cinema and dvd. An Experimental stylesheet for teaching purposes (on line), <http://www.hivt.be>.

Hertog, E., Van Gucht, J. & de Bontridder, L. (forthcoming). «Musings on methodology». In: Hertog, E. & van der Veer, B. (eds.), Tacking Stock: Research and Methodology in Community Interpreting. Linguistica Antverpiensia N.S 5/2006.

Lucey, P. (1996). «Twelve Strategies for Enhancing Visual Content». Creative Screenwriting. Writing Independent Film, 3/1, pp. 98-106.

Mehring, M. (1990). The Screenplay. A Blend of Film Form and Content, Boston & London: Focal Press.

Schellhardt, L. (2003). Screenwriting for Dummies, New York: Wiley Publishing.

Tymoczco, M. (1999). Translation in a Postcolonial Context, Manchester: St Jerome.

Vercauteren, G. (forthcoming). «Towards a European Guideline for Audio Description.» In: Díaz Cintas, J., Orero, P. & Remael, A. (eds.). Media for All. Accessibility in Audiovisual Translation.

Woolf, V. (1925/1976). Mrs Dalloway. Frogmore, St Albans: Triad Books.

Yeung, J. (forthcoming). «Audio Description in the Chinese World.» In: Díaz Cintas, J., Orero, P. & Remael, A. (eds.). Media for All. Accessibility in Audiovisual Translation.

appendix 1: ransom (ron howard, 1996), description of the film opening (approx.4 mins.)

Writing credits: Cyril Hume & Richard Maibaum (story)

Screenplay: Richard Price & Alexander Ignon

Slow music mixes with city sounds (a siren) as the Touchstone Pictures logo is still on screen and the credits begin to appear. A tracking shot follows cars and the ambulance10 producing the siren, as they speed along a street bordering on Central Park in Upper Manhattan. The music gradually gains prominence then recedes as the camera draws attention to the images instead: a long shot of Central Park and the surrounding streets. Like the pieces of a jagged puzzle, the word RANSOM, the title of the film, is assembled on the screen. Voices suggesting conversations between several people are superimposed on the city noises and music as several people walk into the picture.

There is a party going on at one of the flats overlooking Central Park: a group of people appears on a terrace. What suggests this is a party, is the noise of conversation, and the first couple of whom we get a good view. The man is wearing a formal suit, the woman a cocktail dress. She is also holding a cocktail glass. Other people in similar stylish and expensive-looking outfits, carrying glasses, cross in front of the camera.

The first verbal exchange comes from inside as a voice calls the people on the terrace in to watch a commercial. Pieces of conversation from an unidentified speaker tease someone referred to as ‘him’, the subject of the commercial video, who also turns out to be the main character. As a hand pushes a video tape into a recorder and people gather in front of a television set, a young, blond boy, the kid of the house, peeks into the living room.

The TV screen showing the commercial now fills the entire screen. A man is talking about his «humble beginnings», and text on screen says : «Tom Mullen. Chairman. Endeavor Airlines». Through images and narration the video commercial tells Mullen’s success story, as the guests make mocking remarks. The fact that they are teasing Mullen is as obvious from the tone of their voices as from what they are actually saying.

The camera alternates between the video tape, and Mullen in ‘real life’ among the guests, as well as his son, who is also moving among the party-goers. Father and son regularly make eye contact, and smile. This is rendered with shot-reverse shots. As some silly scenes from Mullen’s career are shown, the crowd laughs, as does young Mullen. Meanwhile the commercial film continues to tell the success story of Endeavor Airlines and its chairman. In the film, Mullen says «The most important thing to me these days is family», and at this very moment, his wife and son are shown together in a medium-close up, watching the TV screen together. She smiles. In the commercial, Mullen then goes on «Mine. Yours.» The film suggests he is a successful businessman ( who used to be a bit wilder than he is now, which is sympathetic: the audience laughs) and a loving father.

When the viewing is done the guests start moving round again, but the camera returns to Tom Mullen and his son again and again, stressing their good understanding. As his wife walks on screen next to him and teases him, Tom takes her in his arms and kisses her in public. They are the epitome of the successful, rich and happy couple.

As the party continues, the music provides a smooth soft background to a smooth crowd, while a window in the door to the balcony briefly frames a girl who is walking among the crowd , the waitress, holding a platter with snacks.

A rather abrupt cut to a cluttered flight of stairs, that later appears to lead to a basement, is accompanied by an abrupt change in the music, which returns to the percussion of the beginning of the film. In the dreary basement, the camera moves from room to room. One of these rooms is suddenly lit up by a strip light that fills the screen. The camera then turns to the bed below: an iron hospital bed with a bare mattress and handcuffs attached to the railing at the foot and head. On the drum beat the camera focuses on the handcuffs, showing them in close up. A drill in close up is then seen to drill a hole through a wall or wooden panelling and a man, seen obliquely from the back, lights an electric heater: preparations are being made, what for is not clear. The ominous-sounding music is replaced by the voices at the party as the camera cuts from an electric heater in the basement to flames in an open fireplace. Sean Mullen is revealed, playing on a handheld videogame near this fireplace.

The boy looks up and around as the camera moves across the room to the open-plan kitchen where his father is helping some waiters. Tom asks: «Hey, Sean, did you eat something?» From the brief conversation between father and son the camera moves back to the waitress previously shown in long shot, now at work in the kitchen, behind a row of bottles, a makeshift bar. We get a close-up of her face and detect a rather large tattoo half-hidden in her collar. She exchanges a cool glance with Sean, who pulls a face.

From the final shot of Sean, the camera returns to the basement, where a mattress is being moved by a bald man in jeans. The mattress is dropped on to the metal bed. Sound proofing is stapled to a wooden board, a cassette is pushed into a radio, other less easily identifiable buzzing electronic recording equipment is lying on a cluttered table with scissors, wires and a overflowing ashtray. The focus is on the successive preparatory actions more than on the man performing them.

appendix 11: ransom (ron howard, 1996), dvd audio description.

Description of pictures and sounds during the first 4 minutes as they are seen and heard (and understood) by a sighted viewer, with the original audio description and one alternative AD. The passages in bold print are discussed in greater detail in the article.

Interior of the Mullen’s Apartment. Night

Interior of the Mullen’s Apartment. Night

(00:01:12)

Picture & Sounds

A hand puts a video tape into a recorder. The tag on the tape reads «Endeavor Airlines – Tom Mullen» The camera cuts to Sean who is peaking round a corner. The promotional video fills the screen. The camera alternates between video and reactions of people in the room. These can be guessed from the sound track. But not the glances Sean exchanges with his father. The boy is thus connected with the main character in the commercial & the host of the party: Tom Mullen.

The video voice of Tom Mullen tells his life story. But he has not yet been identified aurally in the room, only visually; nor has the blond boy, the only child in the room, and the viewer automatically deduces: the child of the host.

A reverse shot connects their gaze and smiles about the commercial everyone is watching, creating a form of complicity.

At some points in the commercial the audience laughs (e.g. because the passengers of the early flights run by «Endeavor» were animals;

but there is no reference to the visual jokes of the commercial in its promotional narrative)

The blond boys also smiles [no sound] at the antics of the man/host/probably father in the video film. The aural text does convey Tom Mullen’s success as a business man, his drive to be the best, some of his naughtiness as a younger man and: the importance he attaches to family life. As he tells in the video that the most important thing in life is family, we see a blond woman smiling as he says it (his wife?) and the young boy.

The film finishes and applause is heard.

[Other names from the credits are no longer mentioned in the AD]

This provides a tenuous first connection between the man in the video and the host.

A change in the general voice-noise indicates that he enters the room. As he talks to his guests, he again exchanges glances with the blond boy/his son, who smiles.

His wife walks up to him and comments on his so-called shyness. She screams as he pinches her. Then he grabs and kisses her.

The viewer already knows she is his wife from the previous shot.

Audio description

They watch a promotional video.

The guests look round for Tom Mullen, the party’s host.

No AD.

Tom kisses Kate, his attractive blond wife.

One alternative AD

They watch a promotional video featuring their host.

[speak slightly earlier]

The guests look round for their host, Tom Mullen

His young son watches, smiling [go over the party noise]

Tom kisses Kate, his attractive blond wife.

Interior of a basement. Night

(00:02:50)

Interior of the Mullen’s Apartment.Night

(00:03:18)

Interior of the Basement. Night

(00:03:40)

Picture & Sounds

AD allows music change to register.

The camera moves through the basement, away from the staircase and into a dark room, where a light is switched on and we see a metal bed with handcuffs.

The original AD makes no reference to the light being switched on or the type of light that is illuminating the room, even though the sound the tube lamp makes is heard.

In the original AD, there is no reference to the fire place and the relationship between father and son is mentioned only here.

Why not make the visual link through the use of pronouns: ‘the’ young waitress. The AD says nothing about how serious she looks nor about Sean’s his reaction, pulling a face. It does not mention the tattoo either, but there is insufficient time to do this.

AD leaves time for the music to do its work.

This is read in one go: anticipating the sound of the tacking and the sound of the hammering.

Note: the commercial AD is very selective and interprets visuals that are not that clear unless one has some technical know-how.

Audio description

A waitress carries a tray across the brightly lit room.

A dim staircase leading down to an ill-lit basement.

A bleak room, a metal bed, handcuffs.

A drill bit bores a hole.

A hand switches on an electric fire.

Back at the party Tom Mullen speaks to Sean, his young son.

From the open plan kitchen a dark-haired young waitress glances across at the boy.

In the gloomy basement a man with a shaven head heaves a mattress onto the metal bedstead.

He tacks up foam soundproofing and hammers plywood.

He fixes a distorting attachment to a mobile phone.

One alternative AD

A waitress carries a tray across the elegant, brightly lit room.

A dim staircase leading down to an ill-lit basement.

A tube light in a bleak room, a metal bed, handcuffs [sound + photography – visual metaphor]

A drill bit bores a hole.

A hand switches on an electric fire.

An open fire place. [visual narration and contrast]. Tom Mullen speaks to his son Sean.

From the open plan kitchen the dark-haired young waitress glances across at the boy [link made visually in the film]

In the gloomy basement a man with a shaven head heaves a mattress onto the metal bedstead.

He tacks up foam soundproofing and hammers plywood.

He fixes a distorting attachment to a mobile phone.

1 Episodes from TV series: Langs de Kade (AD 1991) & De Kampioenen (AD 2006 by A.Remael). Films: Karakter (AD by students of University College Antwerp, 2006); De Zaak Alzheimer (International Film Festival Ghent, 17 October 2006), AD by De vrienden der blinden/The Friends of the Blind. See Díaz Cintas, J., Orero, P. & Remael, A. (eds.) Media for All. Accessibility in Audiovisual Translation (forthcoming), for more details.

2 Hoger Instituut voor Vertalers en Tolken, is the department of translation and interpreting of Hogeschool Antwerpen.

3 Text is used here in the broadest sense of the term, and refers to film as a semiotic entity consisting of different codes.

4 The authors are aware of the fact that audio describers may also have to identify some sounds, and that sounds will even have an influence on what images must be described. However, the incorporation of such aural factors, which indeed must be considered for the production of audio descriptions, is beyond the scope of this paper.

5 Ransom (Ron Howard, 1996), Die Hard with a Vengeance (John McTiernan, 1995), V for Vendetta (James McTeigue, 2005), The Hours (Stephen Daldry, 2002), Rumor Has it (Rob Reiner, 2005), Karakter (Mike Van Diem, 1997), Pretty Woman (Garry Marshall, 1990), Derailed (Mike Håfström, 2005), The Passion of the Christ (Mel Gibson, 2004), Shall we Dance (Peter Chelsom, 2004).

6 We understand «plot» as «…everything described visibly and audibly present in the film before us», and the «story» of the film as that the narrative elements which go «beyond the plot in suggesting some events which we never witness» (Bordwell & Thompson 1990: 57).

7 Many screenwriting manuals (across decades) have titles that refer to the structure underlying the visible surface story of a film. For instance :The Understructure of Writing for Film and Television, by Ben Brady & Lance Lee (1990); Screenwriting. The Sequence Approach. The Hidden Structure of Successful Screenplays, by Paul Joseph Gulino (2004). They also teach beginning screenwriters how to turn words into images, the reverse operation from audio description: «one of the essentials of story sense is knowing how to tell a story with images rather than dialogue, which can save us from writing movies that end up like illustrated radio» (Lucey, 1996: 98).

8 Appendix 1with this article provides a detailed description of the first four minutes of Ransom, appendix 2 provides the text of the AD featuring on the dvd and one alternative AD.

9 The vehicle is not a police van.

10 The audio description mentions «a police van».