Translating culture-specific references into Spanish: The Best a Man Can Get1

Ma PILAR MUR DUEÑAS

Universidad de Zaragoza

Este artículo se centra en el análisis pragmático de la traducción al castellano de las referencias culturales británicas en la novela The Best o Man Can Get. Dichas referencias aparecen clasificadas y etiquetadas así como las estrategias utilizadas por el traductor español. Se han estudiado también las posibles motivaciones de éste a la hora de optar por una estrategia en particular y cómo sus decisiones pueden afectar a la lectura de la novela traducida. Se incluye una entrevista con el traductor español, cuyas respuestas pueden clarificar algunas de sus opciones durante el proceso de traducción y al mismo tiempo apoyar ciertas ideas desarrolladas en el artículo. En general el traductor parece haber combinado estrategias que acercan la cultura de partida al lector meta can otras que mantienen la distancia entre la cultura de partida y la de llegada.

This article focuses on the pragmatic analysis of the translation of British culture-specific references in the novel. The Best a Man Can Get into Spanish. Those references have been classified and labelled as well as the techniques used by the Spanish translator to deal with them. The possible motivations of the translator to opt for a particular technique and how his decisions may affect the reading of the translated novel have also been studied. The article includes an interview with the Spanish translator, whose answers might clarify some of his options throughout the translation process, and support some of the ideas developed in the article. On the whote the translator seems to have combined strategies that bring

the ST clase to the TR with strategies that keep the distance between the source and target cultural worlds.

1 INTRODUCTON

Translation has to be understood as a product, as a process and as an effect. The product in this particular case is the Spanish translation of the novel under study Lo mejor para el hombre -John O’Farrells Tbe Best a Man Can Get-, the process refers to the particular procedures or strategies used by the Spanish translator, Miguel Martínez- Lage, and the effect is what the translated novel, provokes on the TR2, which should be ideally the same as to the one the original novel provoked on the SR. These three concepts will be essential in the course of the description and contrastive analysis of cultural references in the said novel and its Spanish translation.

Translation has to be considered as an act of communication -although of a special nature. The message to be communicated is already there in written form and the translator´s task is to reformulate it in the TL in such a way that it becomes comprehensible for the intended readers. Therefore, throughout the translating process, the translator needs to «take account of the range of knowledge available to his/her target readers and of their expectations [ ... ].» (Baker 1992: 222).

A pragmatic aspect that the translator might find useful throughout the translation process and that is going to be referred to in the analysis of the strategies used to tackle ST culture-specific aspects is the notion of speech acto Austin (1962) explains that when we use language, we do things with it, we act. A speech act has three components: (i) a locutionary act, its prepositional meaning, (ii) an illocutionary act, that is, what we do with those words, and (iii) a perlocutionary act, i.e. the effect caused on the addressee. The translator should aim at producing equivalent speech acts in the TL. Cultural references, then, have to be identified, pragmatically analysed, translated and revised from a pragmatic point of view in order to assess, particular1y, whether the translated cultural item might provoke a response on the TR that is as close as possible to that response the writer intended to provoke on the SR.

The novel selected for study, Tbe Best a Man Can Get, is full of culture-specific aspects. Those considered most relevant have been classified and their translation into Spanish has been analysed. Not all of them have been equally handled by the Spanish translator, so the variety of strategies used to deal with them has been investigated and will be presented. Since the approach taken for the study is of a pragmatic nature, it is important to think of the in tended readership: people in their thirties or forties seeking enjoyment in reading a popular fiction work. Having this specific readership in mind will possibly influence the decisions taken by the translator during the translation process3, It is the aim of this article to explore which strategy or strategies have been used, the possible motivations of the translator to opt for one particular strategy or another and how these options may affect the reading and interpretation of the novel in Spanish. An interview with the translator, which took place once the study was finished, is included in Appendix 3. This interview can cast some light on the translator´s decision-making process.

2 TRANSLATING CULTURE: ASPECTS

In an attempt to investigate how a literary professional translator deals with the SL culture -which is always considered a difficult part of the translation process- and how his decisions may affect the TR responses, three headings have been coined to cover all those aspects in the novel under analysis that have to do some how with the SC, namely, culture-specific artefacts, culture-specific linguistic expressions, and culture-specific situations or habits.

2.I Culture-specific artefacts

This section encompasses those lexical items that have a referent in the SC. They are further subdivided into semantic fields. For each semantic field a few examples are presented, together with the page number in brackets. A thorough list can be found in Appendix 2.

a) Education: researching his PhD (18); She´d foiled French A-level (35); sixty other fifth formers (112).

b) Measures, weights and currencies: An extra couple of quid a week (11); pints of lager (18); a hundred yards later (36); the number of gallons (147); seven pounds, three ounces (280),

c) Food: fish and chips (98); shepherd’s pie (228).

d) Means of communication: ringing Child Line (11); a copy of Hello (33); East Enders (36); the advert for Britisb Telecom (117); on Radio 4 (146); Sky Sports 2 (249).

e) Leisure: playing Tomb Raider (18); watch ing tbe Postman Pat video (33); ‘I want lo watch Barney video’(69).

j) Brands: tbe Mr Gearbox ad (15); a packet of Cheesey Wotsits (51); Beechmans Hot Lemon drinks and Settlers Tums (127); Pringle jumpers (136); his Silk Cut (160); Multi Cheerios (300).

g) Business and commerce: Boots (12); The

Bull and Last (53); The Windmill Inn (167, 179); Somerjield (86); the offlicence (256).

h) Famous people: a real Bavid Bailey (147); some cut-price Oprah Winftey (184).

i) Objects: kettle (10); snooze button (85).

J) Location: in Godalming (16); Kentish Town (27); the Northern Line (55; 153); Hyde Park (63); Picadilly Circus (112); in tbe Home Counties (127); at Embankment (153); St. John’s Wood (155); Holland Park (249); Stockwell (267).

2.2 Culture-specific linguistic expressions

This label refers to more or less fixed expressions that are used in particular contextual situations and that are easily recognised by the SR and certain implied meanings are instantly triggered in their minds. Examples of this manifestation of the SC are: The wheels on the bus go round and round (90); Caution: May contain nuts (107); Mind the gap (107; 153); Disk full (155); Spare some change, please? (245); out of order (257); I dialled 150(278).

2.3 Culture-specific situations or habits

These situations may not make sense to the TR if they are literally translated and no further explanation is provided. Examples of these customs that may cause trouble when translating a literary work are the following: uncarpeted stairs (25); This generally happened to be around 5 Nouember (84); ‘, . that’s getting fish and chips. I don’t want jish and chips’ lndian?’ (98); including some unspent record voucbers I’d had since Christmas (114); doing Ascott, Henley and Wimbledon (156) going to Fleadb, Reading Festival or Glastonbury (156); The only other women with children at the swings are all eighteen years old and only speak fucking Croatian (235).

3 TRANSLATING CULTURE: STRATEGIES

Translators have first to identify the SL cultural references and their intended meaning or relevance in the passage; in that sense, they should be aware that their reading is going to condition all other TL readings: «[el traductor] es el encargado de producir una lectura que condicionará todas las demás» (López Guix 2000: 194). Then, in view of the intentionality of those references, the translator has to opt for the «optimal translation technique to pass on the information with a minimum of disruption if at all possible» (Fawcett 1998:121). In this sense, Malmkjser (1998: 36) defines the translator as «a recogniser of the writer’s intentions to produce responses in a readership, and next as a purveyor of these, via a new medium, to a different readership than any the writer is likely to have had in mind»,

To purvey those writers intentions encoded in the use of the cultural aspects classified above, the Spanish translator has used a variety of strategies. The overall impression is that he has tried to redress the balance between the SC and the TC, by combining «domesticating» approaches with «foreignizing» ones (Venuti 1994), possibly, in an attempt to show the readers that the novel was in fact originally written in English and that the action takes place in Great Britain, but at the same time, helping them to make sense of what they are reading at those points where he judged it necessary4, A more precise analysis of those strategies is presented below. I have not encountered a completely satisfactory taxonomy that covered all those translation techniques used by the translator when dealing with cultural references. Therefore, instead of borrowing labels from different authors to establish a new taxonomy, I have decided to develop my own labelling. Whenever possible, I have included in a footnote the labels used by other authors to refer to similar translation procedures.

3.1. TL cultural cognate

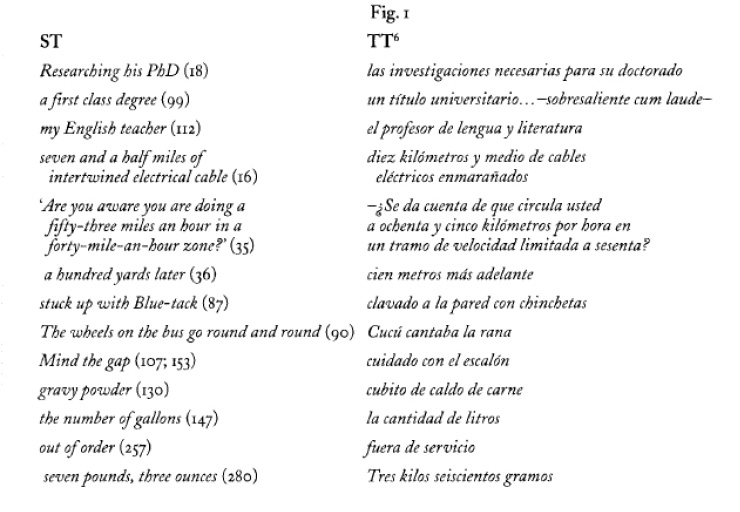

This translation strategy consists in using a cognate lexical item, linguistic expression or concept in the TL so that an equivalent response is intended on the SR5. (Fig. I).

It can be observed that all weights and measures (except pints of lager) have been adapted to the TC as well as most aspects having to do with education. This seems to be a common practice of present-day literary translators:

Existe un consenso general respecto a la adaptación de ciertos elementos, como son los pesos y medidas, la notación musical, los títulos de obras que existen en versión tradu cida o algunas cuestiones relacionadas con el sistema educativo.

(López Guix 2000: 281)

3.2 SL cultural and linguistic borrowing

The translator has left the lexical item(s) in English, probably considering that the co-text or the readers knowledge of the world and/or of the SC can make their meaning clear6.

Newspapers (The Sun), magazines (Helio, Time Out, The New Musical Express), TV channels (BBC2, Sky Sports 2), underground stations (St. John’s Wood, Embankment), many London places and streets (Soho, Big Ben, Canary Whaif, Hyde Park, Kentish Town, Balbam High Road, Berwick Street, etc ... ), that are kept in the SL in the Spanish translation, contribute to set the novel in a British scenery7, No cultural cognates have been used, probably in an attempt not to mix up the two different worlds of reference involved in the translation process.

However, the translator has not been so consistent in the translation of radio channels, childrens characters or pubs8.

Words such as jingle, rijf or snooze button are not lexicalised in Spanish and the translator has preferred to adopt the foreign lexical item instead of using a more complex nominal phrase explaining their meaning, possibly on the grounds that the reader has sufficient contextual information to deduce their meaning and, also, in an attempt to be economical9.

These linguistic borrowings can also perform a ‘marking’ function (Hickey 1998: 220-221), that is, they ‘mark’ the novel as a translation of an English original.

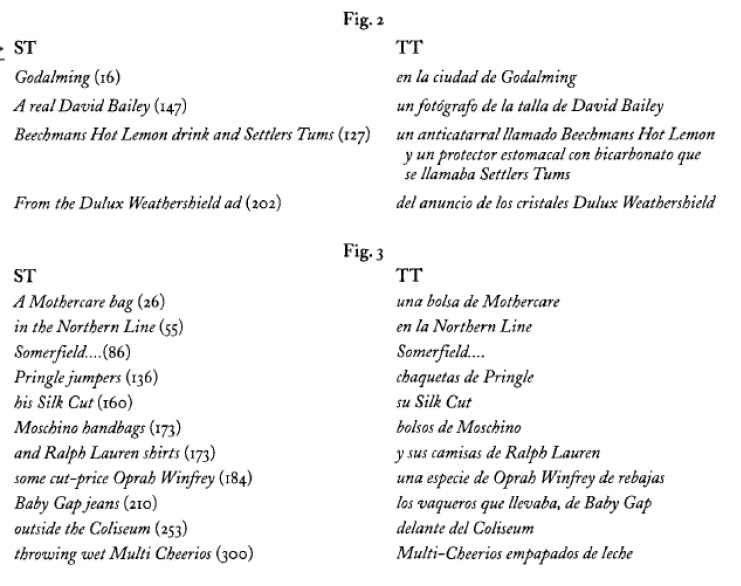

3.3 SL cultural borrowing plus explanation

In other occasions, the translator has decided to intervene by providing his readers with some explicitation so that the text becomes coherent for them. This strategy can be considered a conscious endeavour to «fill gaps in the readers knowledge» (Baker 1992: 250) without leaving out the SL cultural reference.10 (Fig. 2)

During the translating process the translator needs to bear in mind the potential reader-ship´s knowledge as well as the information provided by the co-text in order to decide whether or not to intervene. In the above examples, the translator seems to have considered it necessary to make the cultural references explicit; however, this need has not been fe1t in the following cases, in which no explanation is added:(Fig. 3)

The reader is likely to understand most references thanks to the co-text. For instance, a Spanish reader who encounters the phrase «como si su Silk Cut ... » can figure out that Silk Cut is a brand of cigarettes because the character has puffed a cigarette two lines above; s/he can also get to know that Somer field is a British supermarket because the complete slogan is provided both in the original and the translation: «Somerfield ... y comprar es tan fácil. Sitio para aparcar, y todo a buen precio ... », Much in the same way, s/he can infer that tbe Coliseum is a London theatre because the word «opera» appears in the preceding sentence or that «sus camisas de Ralph Lauren» are high-priced because the novel continues «iban vestidos de un modo tan llamativamente caro ... », which might give the reader the clue that the characters have entered a posh area in London. It is more doubtful, however, that the TR gets to infer what «chaquetas de Pringle» refers too Thus, in sorne cases, cultural references are instantly decoded by a SR while their recognition is delayed in the case of TR.

But some of the implied meanings might go unnoticed for the TR. Although s/he gets to recognise Silk Cut as a brand of cigarettes, s/he probably does not know that it is one of the most expensive ones in England, so the fact that Dirk smokes his Silk Cut says something about his life style. The same happens with Pringle jumpers, which are fine sportswear manufactured in Scotland”, Throughout the passage, there are other indications -which might have been judged revealing enough for the translator- of the kind of people the main character is with at that moment, but these clear emphatic clues that the SR has, are probably missed by the TR. The perlocutionary act then might not have been fully transferred.

It is worth remembering, at this point, the kind of readership this novel is intended for and the kind of literature being translated. The potential TR -people in their thirties or forties

reading for fun- can be thought to have sorne knowledge of the British culture and language, consequently, to be ready to easily understand or even visualise British references. On the other hand, this novel can be considered «easy literature» to be read on the train, on the bus or lying on the beach, and, as a result, readers may not be willing to make an extra effort for the understanding of the text. If this is so, most examples above could be considered too demanding for its readers and might not match their expectations.It has to be said as well that a single decision on the translator´s part regarding the tech nique to be used in translating a cultural item is not relevant; it is only when a certain strategy is more extensively used that it creates a specific effect. In this case the lack of explicitation in rendering culture-specific references into Spanish recurs -whether due to the assumption that it is shared knowledge between the author and the TL readership, or to the assumption that the co-text clarifies the references or to some other reason- and, hence, it produces an effect on the translated product, i.e. the translated novel becomes more demanding for the Spanish readership.

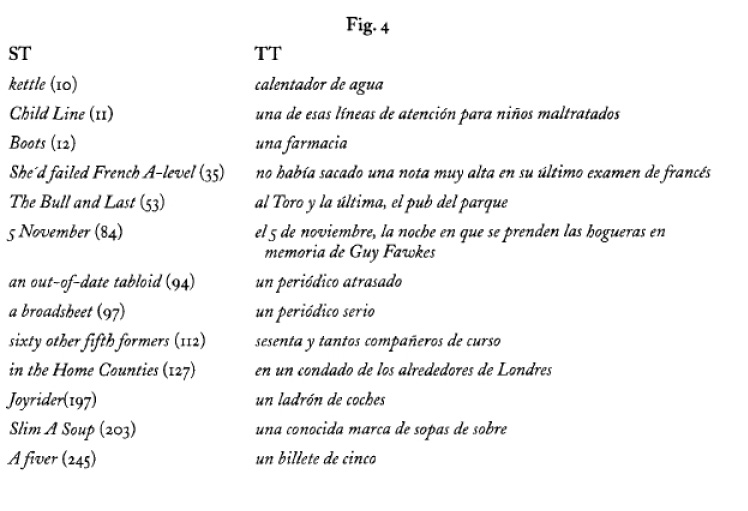

3.4 Replacement of SL cultural reference by explanation

The use of this strategy implies that the translator has intervened as in the previous one but in this case he has also suppressed the cultural linguistic expression11. Fawcett (1998: 121) claims that «if the target audience is assumed not to have access to the presuppositions which will enable them to understand what is being talked about and if the translator decides in consequence that they need to be told» then the most appropriate translation strategy has to be used so that those presuppositions are made accessible for the TR.(Fig. 4)

On a particular point, it can be argued that the difference existing in Britain between tabloids and broadsheets is not complete1y explained for the Spanish reader, who might miss the communicative intention of the novel´s writer, i.e. to depict his characters by means of the kind of press they read.

These examples together with those under the previous labe1 might be considered an attempt on the translator´s part to produce a translated text that reads fluently and is there fore considered acceptable and easily consumed. The translaror´s intention seems to have been that of making the translated novel readable for the new readership12. The translation process can be then considered as «the forcible replacement of the linguistic and cultural difference of the foreign text with a text that will be intelligible to the target-language reader.» (Venuti 1994: 18).

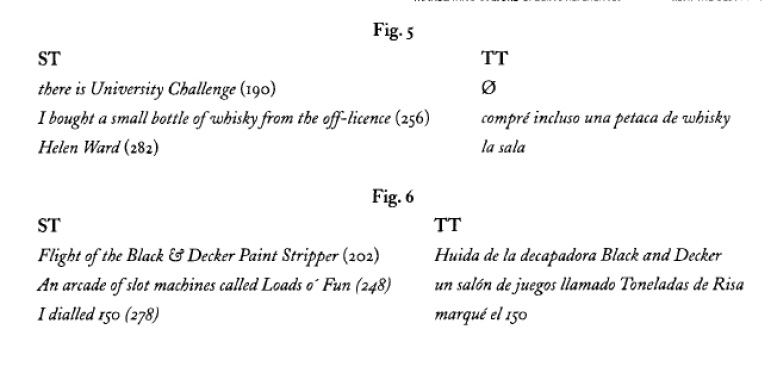

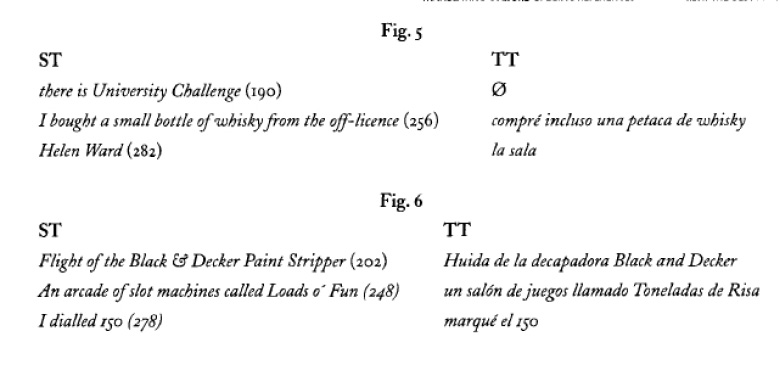

3.5 TL cultural reference suppression

This strategy has been used in very few occasions. The translator may have thought that the cultural reference does not perform a relevant function and that they might even mislead the reader; consequenly, no cultural cognate, explanation whatsoever has been used. On the contrary, cultural references have just been suppressed13. (Fig. 5)

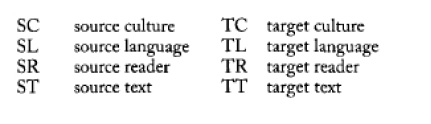

3.6 TL cultural reference literal translation

This procedure could be divided into two groups: on the one hand, those cultural references that are literally translated and whose illocutionary and perlocutionary acts are transferred -what Hickey (2001: 56) calls ‘residual approach’- and, therefore the text is coherent for the readership; and on the other hand, those cultural references that transferred with it and, as a result, the text might not cohere for the reader, who can get puzzled.

Examples of the first group are: (Fig. 6)

In the second example the translation of the arcade is necessary to effectively carry on with the translation of the sentence: «judging by the emotionless grey faces inside it looked as if the sign above the entrance was slightly overstating it». In the case of the third example, the SR will immediately recognise the number as the British phone company customers service phone number, while the TR will probably have to wait to get to know what the protagonist intends to do.

Examples of the second group are: (Fig. 7) When reading some of the examples above the Spanish readership might get puzzled. Some phrases can be meaningless -even senseless- or their original effect may be not perceived by the TRs. A Spanish reader who encounters the term pastel de pastor may think ‘what´s that?’. As Baker puts it: «A proper name or even a reference to a type of food or gadget which is unknown to the reader can disrupt the continuity of the text and obscure the relevance of any statement associated with it» (1992: 230). In order to make sense of Kate´s angry words (jucking Croatian) Spanish readers should know that many British families hire au pairs -most times eighteen-year-old women coming from Eastern Europe- who look after their children. They should also know that it is customary in Britain to buy vouchers at Christmas as presents for one´s relatives in order to make sense of Michael´s new saving technique. Doing Ascott, Henley and Wimbledon is only afforded by a fringe of society, which says something about the people Michael has mingled with. The Sound of Music is the title of a film, which has been proposed as the band name, and has been lite rally translated; its cultural cognate Sonrisas y Lágrimas would probably sound more absurd, since the whole list proposed intends to be absurd and hilarious.

4 CONCLUSIONS

On the whole, the translator seems to have combined strategies that bring the text close to the TC with some others that maintain the distance with that TC, and seems to have assumed a potential readership that is fairly acquainted with the SL culture and who are able and willing to work out certain implicatures from the co-text. This assumption might lead to a harder reading of the translated novel than the original or than the reader might expect.

It can be said that there is a general tendency for weights, measures and terms relating to education to be translated by TL cultural cognates as well as those linguistic expressions whose perlocutionary act prevails over the locutionary one. The names relating to the place where the action is set are left in the SL -unless some kind of explicitation is needed to make sense of what comes later- as well as those of newspapers, magazines etc. that are to be found only in Great Britain, thus making clear the cultural gap between the SC and the TC. To facilitate the reading, the product a brand refers to is normally included even if it do es not appear in the original text; in some cases that extra help has not been provided beca use the information can be inferred from the co-text, but, in such cases, the reader has to make an extra effort to understand the reference. This extra effort has also to be made when a linguistic borrowing has been used; those linguistic borrowings may perform a particular function, that of signalling that the novel has not been originally written in Spanish.

In any case, the translation has to be considered «una acción comunicativa de carácter pragmático» (Carbonell i Cortés 1999: 106). As a result, the potential reader of the translation needs to be always present in the translators mind. Besides, in order to make the appropriate decisions as to how to translate cultural references, certain knowledge of so me pragmatic concepts can be helpful for the translator. The product of the translation has to be checked as to whether what the original text says (its locutionary act), what it does (its illocutionary act), and the effect it has on the TL readers (its per locutionary act) has been kept. If not, that is, if ‘speech act equivalence’ (Hickey 2001: 50) has not been achieved, then the translator needs going back to the process stage and try to find another alternative translating procedure, strategy or technique.

RECIBIDO ENERO DE 2003

WORKSCITED

Austin, J. L. 1962. How to Do Things With Words.

Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Baker, Mona. 1992. In Other Words: A Course on Translation. London: Routledge,

Carbonell I Cortés, Ovidi. 1999. Traducción y Cultura: de la ideología al texto. Biblioteca de Traducción. Ediciones Colegio de España.

Fawcett, Peter. 1998. «Presupposition and Translation». In Hickey, Leo The Pragmatics of Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters: 114-123.

Hickey, Leo. 1998. « Perlocutionary Equivalence:

Marking, Exegesis and Recontextualisation». In Hickey, Leo The Pragmatics of Translation, Clevedon:

Multilingual Matters: 217-232.

-- 2001. «Literary Translation within a Pragmatic Framework». In Eliza Kitis (ed) The Other Within. Vol. 11: Aspects of Language and Culture. Thessaloniki: Athanasios A. Altintzis: 49-62.

López Guix, Gabriel. 2000. Manual de Traducción: inglés-castellano; castellano-inglés.

Malmkjaer, Kristen. 1998. «Cooperation and Literary Translation». In Hickey,

Leo The Pragmatics of’Transiation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters: 25-40.

Newmark, Peter. 1988. A Textbook if Translation.

Prentice Hall International.

O’Farrell, John. 2000. The Best a Man Can Get.

Black Swan

O’Farrell, John. (in press) Lo mejor para el hombre.

Salamandra.

Venuti, Lawrence. 1994. The Translator’s Invisibility:

A History of Translation. London: Routledge.

APPENDIX 1: ABBREVIATIONS

APPENDIX 2: FULL LIST OF CULTURE-SPECIFIC ARTEFACTS

Education: researching his PhD (18); She´d failed French A-level (35); a first class degree (99); sixty other ftfth formers (112); my English teacber (112).

b) Measures, weights and currencies: An extra couple of quid a week (11); seven and a half miles if intertwined electrical cable (16); pints of lager (18); Are you aware you are doing fifty-three miles an hour in a forty-mile-an-hour zane? (35); a hundred yards later (36); the number of gallons (147); seven pounds, three ounces (280).

Food:fish and chips (98); gravy powder (130); shepherd’s pie (228).

d) Means of communication: ringing Child Line (11); on Capital Radio (15; 134); tbe ‘Dear Deirdre’ in tbe Sun (23); a copy of Hello (33); East Enders (36); The Strange Case of Sarab MacIsaac (36); an Open University programme on BBC2 (86); an out-of date tabloid (94); broadsbeet (97); Time Out (109); the advert for British Telecom (117); Tbames Valley FM (I28); on Radio 4 (146); on every channel there is University Challenge or Who Wants to be a Millionaire? (190); Classic FM (201); the New Musical Express (209); Sky Sports 2 (249); Capital Gold (259); BT customer services (278).

Leisure: playing Tomb Raider (18); watching the Postman Pat video (33); drawings of Ratty and Mole (54); ‘I want to watch Barney video’(69); Trivial Pursuit (96); Twister (117) Action Man (176) plastic Power Rangers jigures (289).

f) Brands: the Mr Gearbox ad (15); a Mothercare bag (26); a packet of Cheesey Wotsits (51); tubs of Ben adn Jerry´s ice cream (59); Cheesy Dunkers jingle (lO2); Beecbmans Hot Lemon drinks and Settlers Tums (127); Pringle jumpers (136); his Silk Cut (160); the bottle of Aqua Libre (165); Moschino handbags and Ralph Lauren shirts (173); Flight of the Black & Decker Paint Stripper (202); the Dulux Weathershield ad (202); Slim A Soup (203); Baby Gap jeans (210); a big can of Special Brew (263); Multi Cheerios (300).

Business and commerce: at the Balham Leisure Centre (10); Boots (12); Tbe Bull and Last (53); Toys «R» Us (60); Tbe Windmill Inn; Somerfield (86); an arcade ofs lot machines called Loads o’ Fun (248); outside tbe Coliseum (253); tbe off Iicence (256).

Famous people: a real Bavid Bailey (147); some cutprice Oprah Winfrey (184); Joyrider (197); my personal Sergeant Pepper (200); the Grim Reaper to leap into tbe lift (288).

i) Objects: kettle (10); stuck up with Blue-tack (87); snooze button (85); a fiver (245).

j) Location: in Godalming (16); Balham High Road (18); Berwick Street (24); Soho (14); Kentish Town (27); Bartholomew Close (27); the Houses of Parlia ment ... Big Ben (46); tbe Northern Line (55; 153); Hyde Park (63); Picadilly Circus (112); in tbe Home Counties (127); at Embankment (153); St. John’s Wood (155); Albert Bridge (172); Chelsea (172); Waterloo Bridge ... Canary Wharf ... the City ... The London Eye (219); Holland Park (249); Stockwell (267).

APPENDIX J: INTERVIEW WITH THE SPANISH TRANSLATOR

I must thank Miguel Martínez- Lage for having suggested me to work on this novel and also for his kind acceptance to answer the following questions about his translation of it into Spanish. I interviewed him on the 19th of September 2002, once I had finished writing the article and it was only then that those footnotes that make reference to his answers were added. That talk was recorded and transcribed and what I present here is my own translation into English of his words.

l. What kind of readership did you have in mind when you translated John O’Farrell´s The Best a Man Can Get?

When I was translating this novel 1 thought of read ers who like music: tbe world of pop, rock, blues, but who do not have a close contact with London (although it is true that nowadays most people have been there and have an idea of what the capital of the UK is like). I had in mind a guy like me, but without great knowledge of the English language or culture. A guy of my generation who is able to laugh about such a feverish adventure tbe novel presents.

2. In your opinion, is it important for a translator to have a particular readership in mind?

(To this question Miguel answered by reading the entry devoted to this issue in an unpublíshed dictionary he is working on at the moment, Diccionario de la traducción. Personal índice analítico y razonado de una dedicación profesional. What I present here are some fragments of that entry, leaving out examples and anecdotes.)

It might seem petty to say it, but in tbe same way tbe writer needs to have a reader in mind to whom s/he addresses his/her words -it might be him/herself- the translator needs to speculate and to elucidate «to whom» his/her work is addressed.

The first step to find an answer to this cannot be simpler: I do not translate for my English-to-Spanish-translator colleagues,I euen blush when I give them a copy of my translations.lf tbe book is good, I refer them to tbe original. I don’t translate for those who know more English than me, either; it’d be an affront.

I’m afraid that during my long years of apprenticeship -in the doubtful case that they have come lo an end- I’ve made the terrible mistake lo think that the reader is not as intelligent as or doesn’t know as much as I do; and, sometimes -we shouldn’t generalize- I’ve gone too far in my explanations -surely unnecessary, often pompous- and in that interference -most times hideous- which is the footnote. It is always the inexcusable confession of a deftat.

With time I’ve come to understand that the reader must be intelligenl, that if s/he doesn’t know something s/he’ll look it up anywhere (Internet is of great help for that, at least for those lazy, curious people; encyclopaedias and dictionaries are still necessary): s/he is more intelligent than one might suppose and has to be treated consequentl. for the contrary may be offending.

3. Did you make a conscious attempt to keep separate the two worlds involved in the translation process, for instance, by leaving the name of the magazine Hello in English even though there is a Spanish version of it or, for instance, by including the English cartoons Tbe Postman Pat or Barney instead of searching for a Spanish equivalent?

(Miguel answered to questions 3 and 4 at the same time)

4. When you decided to keep the source cultural reference (e.g. chaquetas de Pringle, una especie de Oprah Winfrey, su Silk Cut etc ... ), did you judge the references could be inferred from the context, did you believe that your potential readers have a certain knowledge of the British culture or was there any other reason not to offer an explanation or to use an equivalent?

Yes, of course. Both worlds must be kept aparto One cannot ‘naturaliza’, one can’t find equivalents. The protagonist has to smoke Silk Cuts, he can’t possibly smoke Marlboro Lights; smoking Silk Cuts is very English, he has to. lt is something that cannot be changed. In the case of chaquetas de Pringle and una especie de Oprah Winfrey, maybe I could. As far as the cartoons are concerned no equivalent can be found, there arent any. Besides, this type of cultural products are also known here in Spain -most people can guess more or less what we are talking about. What is clear is that you could never translate Postman Pat for Pat el Cartero. I think it is best

translated as Postman Pat. As for Hello -Tm not an expert on the matter- but I believe it is not exactly the same magazine as Hola; the characters that appear are not the same. 1 suppose that in Hello Victoria Beckham and her husband appear in most numbers, which does not happen in Hola.

Opting for a thorough naturalization is very risky and it can be done -as my experience proves- one out of a hundred cases. The foreign world has to be maintained, but in such a way that it does not become opaque. That is, sometimes certain explanations or clarijications are needed; these can be very varied, having lo do with the food, the underground -which isn’t exactly tbe same, either-, the parks, etc ... For instance, in relation to Clapham Common I think I included some kind of remark to clarifY what type of park it is because it is precisely a type of park we don’t jind in Spain. If you come across Hyde Park, or Sto James Park, or Creen Park you leave the terms like that because Spanish people identifY them and might have even visited them. The case of Clapham Common isnt, lets say, common, so you have to explain that tbere is a playground, a grove next to it, a few tennis courts in the middle etc ... One tries to depict it by including more details than the autbor has so that the Spanish reader who doesn’t know it gets an idea of it.

5. Was your intention, at any point, to acquaint the TR with the SC?

Yes, necessarily, in every translation. There is a two way movement: on the one hand, you bring the original work to the reader in order to make his/her reading easier, on the other band, you bring the reader closer to an unknown world or al least to a world the reader doesn’t know as well as you do, a world that s/he needs to get his/her bearings within the novel. Ithink this is the reman why it is so difficult to translate novels which are written in English, but that they are set in very far away worlds, such as for instance, Jamaica, Australia ...

6. Was there any special reason for leaving words in English in your translation, such as jingle or snooze button? If you decided to incorpora or those words, why not leaving fish and chips?

The reason for leaving those words in English is very simple: we call them like that, we use the English word. A jingle is a jingle in England, in France, in ltaly and in Spain. It is a jingle, there is no other word for it. You could say música para un anuncio, or use another periphrasis defining it. I think Ido include it at some point so that the reader who doesn’t know what a jingle is understands it. Botón del snooze, there is no other way of saying it, it even appears in a poem by Iñigo Carda Ureta. However, fish and chips has to be translated for pescado con patatas because thats what it is. All this is due to fact that the Anglo-Saxon culture is dominant in tbe world and it imposes some words. «El coche familíar que piensa como un deportivo». Por eso preparé una introducción así como de andar por casa, en plan easy-listening, que luego daba paso a un riff de guitarra eléctrica. What do you do with this? I looked jor the equivalent slogan because there was such an advert in Spain. Así como de andar por casa does not appear in the original but it explains what easy-listening is, a musical gere. Easy-listening and riff are used in Spanish and in any other language. In any case the potential reader of this novel is supposed to baoe certain knowledge of the rock culture and to know what a riff is and if s/he doesn’t, bad luck.

In relation to this, another problem was the translation of the titles of the chapters, for what I had the collaboration of the novel’s author. The Spanish reader has to realise that they are all slogans from ads. Just do it, I bad to leave it in English, 1 didn’t want to, but there was no other solution. It is sometimes unpleasant to have to leave things in English, the case of Nike is an example.

7. Was there any special reason for translating the name of some pubs literally and leaving others in English? (The Bull and Last becomes el Toro y la Última, The Windmill Inn remains the same) This is a slip I made. There must be some consistency when dealing with cultural references and there isn’t

any. I should have translated The Windmill Inn for La Taberna del Molino or something like.

Are there any cultural references that you always handle in the same way in your translations?

You can’t generalize. There isn’t a set of rules that work in all cases. Every context, every author, every kind of novel calls for a specific treatment. This is a carefree translation, with many clarifications, comments because the very style of the novel, its narrative, allows it. Obviously, cultural references have to be handled in a homogeneous way. There must be some kind of internal coherence.

I tend to leave the streets in English when they are real, known; I couldn’t talk of la calle Oxford or how would you translate Circus? However, when the name ofthe street is meaningful, a remark can be added if you believe that the reader has to know why the street is called like that. When a place name is less known or even fictional and its name is relevant regarding what goes on tbere, I normally include an explanation or a translation.

I tend to leave underground stations in English. There are some place names that, although they are meaningful, give flavour to the novel and signal where the action takes place.

I’m in favour of introducing clarifications when needed but never foolnotes because they interrupt tbe reading. The translator has to appear only once, if possible on the cover and in big letters, and then the translator has lo disappear for the rest of the novel, leaving the author and the reader alone, or better, leaving the work and the reader alone. In this sense the translator acts as a Celestina, makes them go to bed together and then vanishes. You cannot interfere in it and a footnote is the greatest interference.

1 I must thank my supervisor Dr. Rosa Lorés Sanz because without her kind assistance this article would have never been written.

2 A list of the abbreviations used and their full forrn is provided in Appendix 1.

3 See Miguel Martínez-Lages answer to question 1 in Appendix 3,

4 See Miguel Martínez-Lages answer to question 4 in Appendix 3.

5 This strategy can be considered similar to Newmarks ‘cultural equivalent’ (1988: 82), Bakers ‘cultural substitution’ (1992: 31) and Hickeys ‘recontextualization’ (1998: 222)

6 The page numbers of the Spanish translation cannot be include since it is still in press.

Newmark (1988: 81) refers to a comparable translation procedure as ‘transference’, Baker (1992: 31) as ‘translation by a loan word’, and Hickey (2001: 56) as ‘incorpora tion’. According to the latter, this approach is «an attempt on the translator´s part to entice the readers to enter imaginatively into the world of the source text».

7 See second and third paragraphs of Miguel Martínez- Lage´s answer to question 7.

8 See first paragraph of Miguel Martínez- Lage´s answer to question 3 and also his answer to question 6 in Appendix 3.

9 See Miguel Marrínez-Lages answer to question 5

10 See second paragraph of Miguel Martínez-Lages answer to question 3 in Appendix 3.

11 To refer to more or less the same procedure New mark (1988: 83) uses the label ‘functional equivalent’, Baker (1992: 40) ‘paraphrase’ and Hickey (2001: 54) ‘exegesis’, which consists In «giving explanation, rather than -or as well as- a mere translation of the original».

12 Miguel Martínez-Lage´s answers to the questions posed in Appendix 3 corroborate it.

13 Only Baker (1992: 40) refers to this strategy as ‘translation by omission’.