CO-Minor-IN/QUEST Improving interpreter-mediated pre-trial interviews with minors

Dr. Heidi Salaets

KU Leuven / Campus Antwerp

University of the Free State, Bloemfontein

Dr. Katalin Balogh

KU Leuven / Campus Antwerp

University of the Free State, Bloemfontein

The CO-Minor-IN/QUEST research project (JUST/2011/JPEN/AG/2961, January 2013 – December 2014) studied the interactional dynamics of interpreter-mediated child interviews during the pre-trial phase in criminal procedures. This automatically involves communication with vulnerable interviewees who need extra support for three main reasons: their age (i.e. under 18), native language and procedural status (as a victim, witness or suspect). An on-line questionnaire, originally distributed in six EU Member States enabled the researchers to map the existing expertise, beliefs and needs of the main actors in the field of pre-trial child interviewing meaning interpreters, police and justice, and child support professionals. In this contribution, we will focus on ImQM (interpreter-mediated questioning of minors) in Belgium through the quantitative analysis of several statements on the role of the interpreter. The narratives then allow for a qualitative analysis to underpin the quantitative results, and paint a more complete picture of the needs in ImQM. Just like an interdisciplinary approach is central to research, teamwork is the keyword in daily ImQM practice.

keywords minors, interpreter-mediated interview, interdisciplinary approach, quantitative analysis, qualitative analysis.

CO-Minor-IN/QUEST: la mejora de las entrevistas con menores a través de intérprete en la etapa anterior al juicio

En el proyecto de investigación CO-Minor-IN/QUEST (JUST/2011/JPEN/AG/2961, enero de 2013-diciembre 2014) estudiamos la dinámica de interacción que se produce en las entrevistas con menores a través de intérpretes durante la etapa anterior al juicio en procedimientos penales. Esas situaciones suponen la comunicación con entrevistados vulnerables que necesitan un apoyo adicional por tres motivos principales: su edad (son menores de 18 años), su idioma y su condición en el proceso (víctimas, testigos o sospechosos). Un cuestionario en línea, distribuido inicialmente en seis Estados Miembros de la UE, les permitió a las investigadoras cartografiar los conocimientos prácticos, las creencias y las necesidades de los participantes principales en el ámbito de las entrevistas a menores en la etapa anterior al juicio, es decir, de los intérpretes, la policía y la justicia, así como de los profesionales del apoyo a menores. En este artículo nos centraremos en los interrogatorios a menores a través de intérprete en Bélgica mediante el análisis cuantitativo de algunas respuestas sobre el papel del intérprete. Esos relatos permiten llevar a cabo un análisis cualitativo que sustenta los resultados cuantitativos y ofrecer una imagen más completa de las necesidades asociadas con ese tipo de entrevistas. La interdisciplinariedad es clave desde el punto de vista de la investigación y el trabajo en equipo lo es desde la perspectiva de la práctica cotidiana de esas entrevistas.

palabras clave menores, entrevista a través de intérprete, enfoque interdisciplinar, análisis cuantitativo, análisis cualitativo.

1. Introduction

1.1. The co-Minor-in/quest Project

The right to interpretation and translation is thoroughly grounded in European legislation. Several Directives aim at safeguarding this right in legal contexts, particularly in criminal proceedings: Directive 2010/64/EU (on the right to interpretation and translation in criminal proceedings) and more recently Directive 2012/29/EU (establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime), which also contains a separate section on the right to interpretation and translation (i.e. article 7). The latter not only devotes particular attention to victims’ rights in general and to interpretation/translation, but also to the support and protection of child victims in criminal proceedings (cf. article 24). Exactly for that reason, this Directive became the starting point for the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST project (JUST/2011/JPEN/AG/2961). This research project, supported by the Criminal Justice Programme of the European Union, runs from January 2013 to December 2014 and hopes to improve interpreter-mediated child interviews in pre-trial settings. It involves partner institutions from six different EU Member states: Belgium (KU Leuven, campus Antwerp; co-ordinator), France (ISIT), Hungary (Eszter Foundation), Italy (Bologna University), the Netherlands (Ministry of Security and Justice) and the United Kingdom (Heriot-Watt University). Through this international collaboration between several member states, researchers and experts from all the different disciplines involved (i.e. interpreting, justice & policing, psychology and child support) are able to share their knowledge and thus strengthen interpreter-mediated child interview practice. What if a teenage girl witnesses a sexual offence in the foreign country where she is on holidays and wants to report this offence to the police? How can all professionals involved ensure that she can give a statement in the right way and guarantee that her testimony fully contributes to truth-finding? How can they make sure that she is interviewed in a child-friendly environment and gets the necessary support? These are some of the questions the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST project tries to answer.

1.2. The Scope of the Project

As the project’s name (Cooperation in Interpreter-mediated Questioning of Minors) reveals, its research topic is limited to investigative interviews with minors, i.e. children under the age of 18. For the purpose of this article however, the term ‘children’ will be used as well, because it is less closely connected to the idea of a particular legal majority age (as is the case for the word ‘minors’). The term ‘children’ also appears in Directive 2012/29/EU,1 the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child-friendly justice: they commonly define children as people under the age of 18. The same age limit serves as a reference point for the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST study. Even though the project’s design covers a fairly extended age span (children from 0 - 17 years old), there is also room for discussing the specific communication needs of various age groups (e.g. very young children as opposed to teenagers) or developmental differences (e.g. mental age that differs from physical age).

The CO-Minor-IN/QUEST project only studies pre-trial interviews with children within the context of criminal cases. The pre-trial phase is an essential part of criminal procedure: any type of inaccuracy incurred during this stage of the investigation will unmistakably have an impact on the rest of the procedure and on the possible trial phase. The very first interview by the police offers the most valuable opportunity for collecting evidence. It must be noted that the actual number of interview instances involving children are often limited as much as possible. Interviews (especially those of child victims and witnesses) are also often recorded for future use in court: if necessary, these recordings can then be used as official evidence so that the child no longer has to appear in person in the courtroom. This factor also adds to the key role played by pre-trial child interviews.

Although the research topic is restricted to interpreter-mediated child interviews in pre-trial contexts, the research team did not impose further limitations with regard to the procedural status of these child interviewees. Directive 2012/29/EU is centred on child victims in particular, but CO-Minor-IN/QUEST widened its scope to child witnesses and suspects as well. It is true that the procedural status of the interviewee will inevitably have an impact on the way the questioning is conducted, but a major point shared by all three types of interviewees (victims, witnesses and suspects) is their vulnerability factor. Any child requires special protection (including appropriate legal protection) ‘by reason of his physical and mental immaturity’, as it was already stated in the UN Declaration of the Rights of the Child (1959). The same idea is also embodied in the proposal of the new Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on procedural safeguards for children suspected or accused in criminal proceedings, drafted in November 2013 (COM/2013/0822), discussed in 2014. The goal is that approval can be ready and signed in the coming months (expected time of approval: Spring 2015).

Moreover, the procedural status of the interviewee may not always be that clear from the start or might even change during the course of the interview (e.g. a child suspect who turns out to be a victim of neglect himself). For the above reasons, the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST study decided to take into account interviews of child victims, witnesses and suspects.

The idea of children’s vulnerability and the corresponding need for protection also appears in several legal sources. There is not only the victims’ Directive (2012/29/EU) – with particular focus on child victims - discussed in the introductory lines of this chapter, but also Directive 2010/64/EU which regulates the provision (art. 2) and quality (art. 5) of interpretation in criminal cases. The right of foreign-speaking interviewees to be provided with high-quality interpreting services when needed is at the heart of the research conducted by the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST partnership.

Another important source is the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, see http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/impact/ia_carried_out/docs/ia_2013/com_2013_0822_en.pdf), which explicitly mentions the right to free assistance of an interpreter, yet only for child offenders (cf. art. 40[2] VI). Other closely related key requirements included in the UNCRC are the right of every child to express their views freely and their right to be heard (cf. art. 12), as well as the overarching priority principle of the best interest of the child (art. 3).

All these sources - evoking the child’s right to interpretation directly or in more general terms (such as the ‘right to be heard’) – form the legal framework at the basis of the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST research project.

When one considers the interview settings studied, the vulnerability of the child interviewees can be identified at three separate levels. Two of these levels have already been discussed earlier in this chapter: age (children under the age of 18 are generally considered to need extra protection) and procedural status (either as victim, witness or suspect). Thirdly, the interviewee’s native language can also be regarded as another vulnerability factor: if the child’s first language differs from the language of the procedure, s/he will also need extra assistance (i.e. linguistic support – interpretation and/or translation) to fully participate in the interview process. Next to this, the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST also devotes special attention to added levels of vulnerability, as is the case for particularly vulnerable children: e.g. children who are deaf or hard of hearing, mentally or physically impaired interviewees, etc.

Because of the inherent vulnerability of young interviewees, a child-sensitive approach is indispensable for any of these interviews.

To create this child-friendly interview approach and to ensure that each child’s needs are met, close cooperation between all professionals who are involved in the interview process is absolutely necessary. For that reason, promoting knowledge exchange between all professional groups concerned is the most important aim of this research, which brings together specialists from several different areas of work (e.g. interpreters, the police, lawyers, judges, psychologists, psychiatrists, behavioural scientists, child-support workers, etc.) so that they can share their expertise. This idea of knowledge exchange also fits within article 25 of Directive 2012/29/EU, which states that practitioners working with children in legal contexts should be properly informed and trained.

1.3. Literature Review

Such interdisciplinary exchanges will undoubtedly further advance research in the field of interpreter-mediated child interviewing in justice. A qualitative literature review in the master dissertation Interpreter-mediated interviews of child witnesses and victims: status quaestionis (Van Schoor, 2013) showed that there were no specific (scientific) sources available on interpreter-mediated child interviews in pre-trial settings in the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST partner countries (i.e. Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom). This might stem from the fact that the subject matter is relatively highly specialized (because of the specific combination of interpreter mediation and a pre-trial context). The author found, however, that even for other more general legal settings only a limited number of sources discussed interpreter-mediated child interviewing in depth. She attributes this lack of readily available information to the highly confidential nature of this type of interview (particularly when children are heard as part of a criminal procedure). Another possible explanation may consist in the mainly internal use of child interview procedures, which are often only known and distributed among the practitioners concerned (police, social workers, psychologists, etc.) (Van Schoor, 2013: 63). Consequently, this information is not always readily available for everyone, including researchers.

Van Schoor’s literature review (2013) therefore included general sources on child interviewing in a legal setting in the first place, such as the UK Guidance on interviewing victims and witnesses,2 which was however not available for every partner country, and also scientific articles discussing children’s reactions and behaviour in legal interview situations, written from a psychological point of view or behavioural perspective (e.g. Guckian & Byrne (2010-2011), Jaskiewicz-Obydzinska & Wach [no date], Lamb et al. (2007), Schollum (2005), Scurich (2013)). Another example connected to the latter category is David La Rooy’s webpage, which focuses on the The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development protocol (NICHD), a frequently used interview protocol for children of all ages (see: http://nichdprotocol.com/the-nichd-protocol/). This website brings together numerous sources on (forensic) interviewing of children (books and other research, research talks, videos and training material). It even contains translated versions of the NICHD protocol in Spanish, Italian or even Chinese, Hebrew and so on.

Next to these general sources on child interviewing, Van Schoor also consulted an article by Matthias & Zaal (2002) which offered another interesting point of reference, although it focuses on interpreting for children in South-African trial settings only. From all the above, it is clear that interpreter-mediated pre-trial child interviews are a relatively unexplored topic in interpreting studies and other fields of research. There is a great need for further study in this area: the two-year CO-Minor-IN/QUEST project constitutes a considerable step forward in that direction.

Finally, the fact that in the questionnaire we dedicated a lot of attention to items that refer to the «role» of the interpreter, is also rooted in research and literature where the role of the interpreter is a frequently discussed topic. An additional reason for selecting this particular item is that the role of the interpreter is one of the key issues in the gradual professionalization of community interpreting. Initially, in ancient times the interpreter’s role was deemed to be much more than a mere translator: he could serve as «a guide, adviser, trader, messenger, spy or negotiator» (Pöchhacker, 2004: 28). Much later, in the middle of the 20th century, if we look at the history of the role of the interpreter (Roy, 1993), the interpreter was seen as rather intrusive in the interaction process, especially in the Deaf community. This is «the interpreter as a helper» model where interpreters took decisions for the Deaf people. As a (re)action to this model, the first normative and prescriptive rules for professional sign language interpreters who wanted to be on the RID (Registry for Interpreters of the Deaf) were based on the «interpreter as machine» metaphor and in a gradual professionalization wave, this was extended to spoken-language community. In this machine-view, ideally the interpreter is a neutral conduit, without any influence on the conversational meanings, practices and context(s).

Since the 1980s, however, studies have shown that the passive conduit role for interpreting is in fact unrealistic (e.g. Roy 1993, Wadensjö 1998; Metzger 1999; Angelelli 2001). Partly in response to these observations, other models were introduced, including the bilingual-bicultural mediator model (cf. Llewellyn-Jones & Lee 2014). They suggest that the role of the interpreter should not be seen as fixed but as flexible and adaptable, developing along with the interaction. In addition, certain authors explored the role of the interpreter as a co-participant (e.g. Roy 2000, Angelelli 2004): they argue that the interpreter is an active participant in the mediated conversation.

Yet, in many codes of conduct formulated by clients, the strong normative expectation of the interpreter’s neutrality largely remains in place. Consequently, not only do interpreters keep struggling with their role(s) and responsibilities (see Valero-Garcés & Martin (2008)), but also «direct users» of interpreters either do not really know what to expect from an interpreter or have wrong expectations, not to mention the fact that research rarely sheds light on the direct user’s expectations and experiences in dealing with an interpreter. In our case the direct users would have been the minors that we couldn’t interview, for obvious reasons, but thanks to the questionnaire we were at least able to listen to the voice of the other interpreter users, namely of the other professionals involved in the questioning next to the interpreter.

Hence, it is not surprising to see that the sometimes polemic debates between the interpreting researchers and the organizations/agencies who offer community interpreting services reflect the divergent opinions on the role of the interpreter, as we will see in the results. This is the case not only among different groups or «stakeholders» ( i.e. interpreter users), but also amongst the interpreters themselves who are constantly torn between their ethical code and the real world experience of interpreting in the community.

2. Overview of the Project’s Structure and Methodology

2.1. Overall Structure

It was stated in the project description from the beginning that a needs analysis of the parties involved in the questioning of children was necessary. It was clear that a questionnaire was the right way of discovering these needs, i.e. by asking «people’s opinions about different issues», while still keeping in mind that «you cannot ascertain whether what they say is true» (Hale and Napier, 2013: 52). Since the absolute «truth» is not what we were looking for, we thought a questionnaire would be the right instrument to ask people about the gaps, problems and needs they are confronted with, not only in a child interview setting in general, but more specifically in a setting where - in addition to the usual challenges inherent to communicating with children - an important linguistic factor is also involved: the child does not speak the language of the interviewer (and/or child support worker, psychologist, lawyer, etc.). We decided to distribute the questionnaire on line, since current tools and technology allow for an easier distribution (especially with the snowball method that was used – see 2.3) and data processing. It turned out to be the right choice, given the number of completed questionnaires that will be discussed later.

Since questionnaire design is extremely important, we decided to organize a round table with experts from the three domains involved, i.e. legal actors (police officers, (youth) lawyers or (youth) judges), child support workers (including psychologists or therapists) and interpreters (both signed and spoken language interpreters), before drawing up the questionnaire. Given the little background research in this domain, we wished to learn more about each other’s expertise. For instance, the child support worker is not always aware of the interview protocol that police officers might use when questioning a child, the interpreter is rarely informed about interview techniques by the police - let alone in child interviewing! - and the police officer generally considers the interpreter as an intruder, just to mention a few stereotypes. A workshop proved to be the ideal way to meet with several experts from all professional areas discussing these stereotypes – why did they exist and what could be done to prevent them? – and to design the most appropriate questionnaire.

From the round table discussion it became clear that the interpreter is the interview participant with whom the others were less acquainted: other professionals either thought that the interpreter was a kind of machine that is only there «to translate» and preferably «to translate literally», and that s/he must be as invisible as possible for the sake of the truth-finding process, or they were convinced that s/he should show enough empathy and in some way ‘help’ to make the interview process easier by pointing out socio-cultural issues that come up during the interview.

Next to that, legal practitioners highlighted the gap between daily practice and the law: so for the project partners it became clear that the questionnaire should focus on daily practice to uncover the exact needs in day-to-day situations. Asking questions about hypothetical or theoretical aspects only would not have helped us to discover the needs in the field and people would probably also be less willing to participate. At that stage, it also became apparent that a clear-cut line between a child witness, suspect or victim was not easy to draw, as was already pointed out before. During the workshop, the legal actors present (but not only them, of course) already learned a lot about the way in which interpreters work. Already at this stage, joint training of all parties involved was brought up as a possible and efficient way of preventing future misunderstandings about the role of the interpreter and by extension of all the professionals involved.

Finally, psychologists shed light on several issues that had to be taken into account when interviewing a child, including the particularities of communication with children, such as trauma awareness, which is crucial for all participants in the conversation. For example, non-verbal communication was stressed as being vital to the course of the interview, as were hesitations, silence or knowing the child’s vocabulary. Police officers, judges, lawyers etc. should consciously select the right language level when interacting with a child, without being patronizing. It became clear that it is not the interpreter’s task to adapt the interviewer’s language to the level of the child or to explain (legal) terminology or words or concepts that go beyond the child’s understanding. Moreover, the following concerns were expressed, all of which point at issues that should be dealt with before and after the interview: thoroughly preparing the interpreter by giving her/him access to the child’s psychological report, a clear and child-friendly introduction on the interpreter’s role during the interview («Who am I? What will I (not) do? What will I (not) tell to others? Can you tell me everything just like you would tell it to the police officer?» etc.), a short discussion on the best possible interpreting mode (consecutive or simultaneous) and so on. Finally, supervision of the interpreter through a psychological follow-up after the interview was also put forward as a possible support mechanism since child interviews in criminal cases can be equally traumatizing for all participants, but especially for the interpreter who normally does not deal with this kind of interview on a regular basis, unlike the expert police officer who is trained to conduct (video-recorded) interviews with children, using a particular interview protocol (e.g. the NICHD protocol see: http://nichdprotocol.com presented by David La Rooy on May 7th 2013 at KU Leuven, campus Antwerp during the workshop for the consortium). This, however, does not mean that professionals who are used to working with traumatized children are all automatically immune to post-traumatic stress disorders. However, it is more probable that support services are already in place for them, while this is not the case for the interpreters working with minors.

2.2. The Questionnaire: design

The questionnaire design was based on the expertise of dr. Szilvia Gyurkó (Eszter Foundation), a criminologist, consultant and research expert for the UNICEF Hungarian National Committee, who has acquired extensive experience in quantitative and qualitative research through many projects for NGOs or Hungarian ministries. The first component of the survey, i.e. the participant information page (Hale and Napier, 2013: 55), had to contain essential information, which would turn out to be of extremely high importance for our research and the analysis afterwards. An introductory text explaining the scope and purpose of the research was complemented by a drop-down menu where the participant had to select the preferred language for the questionnaire (Dutch, English, French, Hungarian or Italian). Next, the respondent was asked to select the country and region s/he works in. For research purposes, respondents were subdivided into four categories according to their area of work: justice and policing, psychology, interpreting and «other relevant professional fields» (like social workers and child support workers, paediatrics and nurses for instance).

Sign language interpreters and spoken language interpreters received a slightly different set of questions, because they operate in different contexts, with different seating arrangements and are faced with different types of vulnerability. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they worked as a spoken language interpreter or sign language interpreter (or both) so that their answers could be stored separately. Interpreters that work both as a spoken and a sign language interpreter were kindly asked to fill in the questionnaire twice: first as a spoken language interpreter, then as a sign language interpreter.

The question about the area of work was followed by information collection on the respondents’ specific job title (since professional categories in the preceding question were only broad categories), on their experience in working with children in their specific domain and its frequency, the age categories of the children they worked with (subdivided according to scientific standards in child development: ages 0-3, 4-6, 7-10, 11-14, 15-18) and the types of cases they were involved in (by means of a checkbox with possible criminal cases , including the option «other» and some room for further explanation). This enabled researchers to check the relevance and validity of the answers based on the respondents’ general level of experience and the number of instances they had worked with children. At the same time, these questions gave respondents the chance to leave the questionnaire if the survey was not applicable to them, even though the introductory text (clearly stating that the questionnaire targeted people involved in interpreter-mediated communication with children) should have prevented them from starting anyway.

All respondents were asked if they had received any training and if this was the case, to specify the kind of training. The first section on experience and training was then concluded by the following key question: Do you have experience with interpreter-mediated encounters with minors? If this was the case, respondents could proceed to both the central and final part of the survey. If not, they were immediately directed to the final demographic section.

At the end of the survey, all respondents were asked for some additional demographic information and were directed to the project website.

Since all factual and behavioural questions (Hale and Napier, 2013: 56) were asked in the participant information section that had to be completed by respondents with or without experience in interpreter-mediated child interviewing, the actual questionnaire items involving attitudinal questions (Hale and Napier, 2013: 55-56) were limited to the central part of the questionnaire. Attitudinal questions were always followed by an open section for comments («other» or «please explain») because it is known that «many respondents will not want to spend extra time writing narrative answers and will leave those blank» (Hale and Napier, 2013: 57). Most questions were closed with checkboxes or required Likert scale answers (with a 1 to 5 range, from «I completely disagree» to «I completely agree»), but most of them included the opportunity for the respondent to provide more detailed answers.

After a general introductory question about the main challenges in working with children in legal settings, the following questions were structured chronologically, and addressed issues arising before, during and after the interview. The questions were adapted to each professional group, as can be seen in the section entitled «before the interview», for instance:

Do you receive a briefing before working with minors? (- for the interpreters)

Do you brief the interpreter before the encounter with minors? (- for legal practitioners, psychologists and other professional groups)

Most issues and challenges regarding the interpreter-mediated questioning of minors were tackled in the «during the interview» section, which seemed to be logical at that stage of the questionnaire design. Yet further research and experience acquired through expert meetings and round tables (in the year following the survey) would demonstrate that the most crucial phase is the preparatory phase before the interview, because adequate preparation is of the utmost importance in avoiding misunderstandings or problems during the interview. Even when this subsequently acquired knowledge was taken into consideration, the actual structure of the questionnaire (with a short component for the «before the interview «and «after the interview» section and a longer part for the «during the interview» section) has not influenced the results in a negative way. The «after the interview»-questions were related to the possibility of debriefing for all professionals (including interpreters).

It is also important to note that both legal and interpreting terminology was localized for each questionnaire: e.g. in Italy a distinction had to be made between interprete (interpreter) and mediatore linguistico-culturale (language and culture «mediator»); for the UK common law terminology (which differs from continental civil law terminology) had to be used instead.

A conclusive question «What do you personally think is needed to improve interpreter-mediated encounters with minors?» offered the respondent the opportunity to address other issues that were not mentioned in the previous questions and to stress (from a personal perspective) urgent needs in interpreter-mediated questioning of minors.

The questionnaire was piloted in Antwerp, with a professional of every group, and slightly adapted before sending it out.3

2.3. The Questionnaire: distribution and analysis

As stated before, the questionnaire was distributed on line: this was done with the Qualtrics on line survey software. The questionnaire was initially launched in six different EU member states in October 2013: Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, UK (Scotland) and the Netherlands, i.e. the countries of the project partners. The questionnaire was consequently distributed according to a non-probabilistic sampling method, i.e. the network or snowballing method (Hale and Napier, 2013:71). The survey was sent to network contacts of the consortium members (legal actors, psychologists, interpreters, child support workers and professional associations of these professional groups).

The method was an unexpected success, which confirmed the researchers’ belief that there is an urgent need for more clarification and support in this unexplored field of research. More than 1000 respondents started the survey. Some probably did not read the introductory text carefully enough and did not finish the questionnaire. Nevertheless, we received 610 completed surveys from all professional groups, mainly in the partner countries but thanks to the snowball effect also from Norway (82 answers), Slovenia, Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, Australia, Greece and Serbia.

Mixed methods were used to analyse the results: a quantitative method was applied through closed questions that restrict respondent’s answers (Likert scale scores, Yes/No answers) and that enable to check statistically the significance of correlations between the data. Subsequently, a qualitative method was used to analyse and categorize the answers to the open ended questions as well as the remarks, comments and observations written down by the respondents for example in the «other» category.

Regarding the quantitative analysis, it was first of all necessary to recode the regions and professions of the respondents. The recoding of the area of work comprised data from all countries. Based on the answers to the open question asking for a specific job title, the researchers could check whether respondents had assigned themselves to the correct professional category. In consultation with the project partners, recoding of the country regions was discussed: for some countries such a recoding was judged to be less useful (e.g. for Hungary or France), for other countries (UK, Italy and Belgium) regions were regrouped.4

For the qualitative part of the analysis, the research coordinators made a translation in English of the narratives to be able to select keywords. To avoid possible subjectivity, the selection of narrative keywords was discussed and triangulated by the coordinating research team. The survey yielded a massive amount of qualitative data since – contrary to what is generally expected from questionnaires – respondents very frequently added extensive narrative responses consisting of one to five sentences or even more. In total, 20 files including the categorized qualitative results from the project partners’ countries were created.

3. Results

3.1. The Quantitative Part

Since an exhaustive presentation of all results of the questionnaire is beyond the scope of this contribution, we limit ourselves first of all to an analysis of the respondent’s information.

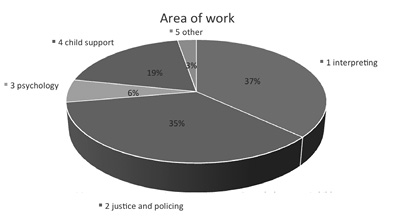

When looking at the area of work (chart 1) we can see that both interpreters and legal actors are equally represented, while child support workers and psychologists were the smallest group of respondents. The only possible explanation is that the snowball method did not reach as many professionals in these groups as expected, although their presence is highly recommended and often part of the standard procedure when questioning children. One could argue that the group of psychologists is by definition smaller in the setting: they are not always present and they are as «psychologists» a homogenous professional group, compared to the professional group of legal actors (who are a more differentiated group), but that argument should rather apply to the interpreters, since an interpreter-mediated encounter with children is more rare than a «regular», monolingual encounter (i.e. where all interview participants speak the same language).

Chart 1: Please select your area of work

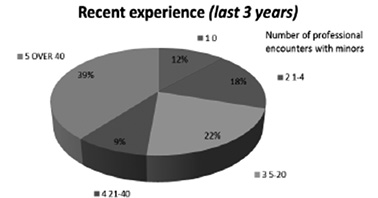

Chart 2: Approximately how many times have you worked with minors in the last 3 years?

Chart 3: How long have you worked with minors in this professional field?

Chart 4: Approximately how many times have you worked with minors in the last 3 years?

Concerning the question on expertise, it has to be mentioned that, after studying the original subdivision of the answers related to the respondents’ recent experience in working with children (Approximately how many times have you worked with minors in the last 3 years?: zero, between 1 and 4, 5 and 20, 21-40, over 40), we decided to merge the results into two categories only: the first one «zero» (including respondents who completed the questionnaire although they have no recent experience in working with minors) and the second one for those respondents who had at least one professional encounter with children in the last 3 years (chart 2). It showed that the vast majority of respondents (88%) did have some experience in working with minors.

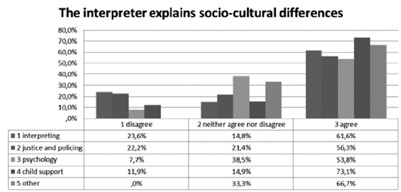

Chart 5 : The interpreter takes the initiative to explain socio-cultural differences

Chart 6 : The interpreter takes the initiative to explain technical terminology

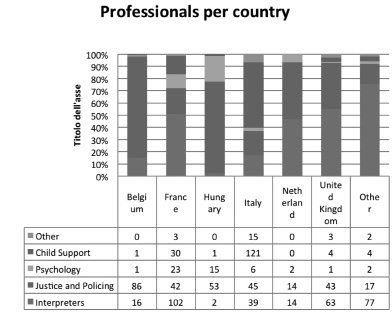

Chart 7: Overview of the respondents per country

The next chart (chart 3), which shows the exact number of the respondents’ years of experience, is very reassuring. The vast majority has many years of experience in working with minors: 56 % has even more than 10 years of experience. Only a small percentage of respondents (less than 1 in 10) has less than 1 year of experience in working with minors. When we subsequently looked at chart 4, this observation was confirmed: almost half of the research population had more than 20 professional encounters with children in the last three years. Only one fifth had very little experience with children (between 1 and 4 of the professional encounters in the last three years), while still another 22% had 5 to 20 encounters with minors during the same period. This means that the representativeness of the respondents is rather high: they have many years of experience in which they have had regular interviews with children, so they are optimally placed to identify problems and needs and to have a clearer idea about possible solutions or recommendations.

Next to the analysis of the information page, we will also discuss two items that were part of the question: «In your view, what is the interpreter’s function when working with minors?», i.e. comments on the following statements: The interpreter takes the initiative to explain socio-cultural differences and The interpreter takes the initiative to explain technical terminology.

Before entering into the details of the data, it has to be mentioned that we merged the 5 point Likert scale answers into 3 point scales to obtain more clear-cut correlations: I disagree (merging I completely disagree and I rather disagree), a kind of middle category that is hard to interpret (indifference? ignorance?) (neither agree nor disagree) and a third category: I agree (merging I rather agree and I completely agree).

After examining the charts, the analysis of the narrative responses provided an extra opportunity to look at the quantitative results in more depth and to add some further qualifications to the quantitative data or correlations.

However, since it is impossible to examine the narrative responses of all participating countries in detail here, we will focus on Belgium, the home country of the project coordinators and authors of this article. After a very brief introduction on the current situation regarding legal interpreting, some additional explanation will be given on the charts. It is important to note that the charts displaying quantitative results cover all respondent groups, while the qualitative analysis will only consider two professional groups in Belgium (i.e. interpreting and justice & policing). We should, however, not forget to mention – see chart 7 – that the number of psychologists, child support workers and «other» professionals who completed the survey is rather low in all the member states of the consortium (except for Italy and France). Since the only respondents in Belgium who also gave narrative answers came from the field of interpreting and justice & policing, further analysis will only consider those two groups. Moreover, these participant groups are in general also the largest ones in all countries, except for Italy (36 interpreters and 45 participants from justice and policing). It is difficult to explain this phenomenon: particularly in Belgium and the Netherlands, the snowball effect did not seem to reach one particular target group, i.e. all those people who are not directly involved in interpreting or justice/policing but who provide direct support to the children. Although the project coordinators are in contact with a large network of Belgian legal interpreters, the response rate in this professional group was rather low: this can be explained by the fact that this group apparently has little or no experience in interpreting (forensic) interviews with children up till now. This in turn can be explained by the fact that in Belgium – except for Antwerp - there is still very little awareness and knowledge of professional legal interpreters (see 3.2.1) , let alone about interpreting for children. Presumably ad-hoc interpreters (family members, friends, neighbours or random people who speak the language of the person who must be heard) are still often recruited.

When considering the results of the charts, it is most surprising to note that both the interpreters and legal practitioners share the opinion that socio-cultural differences and technical terminology should be explained by the interpreter: interpreters usually have a strict code of conduct in which impartiality is strongly emphasized (i.e. no interference, no initiatives by the interpreter). The same goes for the legal practitioners who normally attach great importance to their personal autonomy and their own professional expertise in controlling the interview. They do not want anyone else – especially someone who is not part of the profession – to interfere. The analysis of the narratives will help us to further qualify this observation.

3.2. Results: the narratives

3.2.1. Belgium and lit training

Before discussing the narrative responses, it is necessary to give a quick overview of the situation in Belgium regarding the professional and legal status of Legal Interpreters and Translators (LITs). At the time of writing this contribution (September 2014), the 2010/64/EU Directive has not yet been implemented by Belgium, but the country is running out of time: by October 2014 «the Commission shall submit a report to the European Parliament and to the Council, assessing the extent to which the Member States have taken the necessary measures in order to comply with this Directive, accompanied, if necessary, by legislative proposals» (2010/64/EU, article 10).

When reading Rosiers (2006: 50), we learn from the research carried out by Vanden Bosch almost 15 years ago, that there was no legal protection of the LIT profession, nor any description of norms or quality requirements. Unfortunately, the first gap in the law that Vanden Bosch is referring to is still there: the LIT profession is not protected, which means that anybody can claim to be a professional LIT. Even when they lack the necessary skills, in cases of bad conduct or even of evident criminal behaviour (e.g; an accomplice who acts as interpreter), no legal or disciplinary action can be taken against imposters (ImPLI, final report, 2012, 59-60 & 73-74).

Until 2000, there was no quality control whatsoever with regard to the authenticity of degrees, the linguistic knowledge of the working languages of a LIT candidate, or translation or interpreting skills as such. Candidate LITs were accepted or rejected by the general assembly of the Court of First Instance, and afterwards accepted LITs were invited to come to the court in Antwerp (or elsewhere in Belgium) to be sworn in. As a result, the new LITs did not receive any guidelines or rules on how to behave or which norms to follow. The only legally binding form they received was the one with the rates of pay (Rosiers, 2006: 52).

Fortunately, this second gap concerning quality standards and subsequently training has been filled thanks to the successful implementation of training modules (in line with practice standards) in the academic year 2000-2001 at KU Leuven, campus Antwerp. The training programme – which still exists – is the result of close collaboration between legal actors in Antwerp, i.e. the Court of First Instance (Rechtbank van Eerste Aanleg/Tribunal de Première Instance i.e. a trial court of original or primary jurisdiction), the Antwerp bar association, the Antwerp police and (at that time) Lessius University College, now KU Leuven, Campus Antwerp. Its main aim is not only to train new LITs, but also LITs who were already sworn in before 2000. It is one of the few LIT training programmes that exist in Belgium and definitely the only one offering a 150- hour course with entrance and final exams as evaluation tools. Finally, it must be stressed that the Antwerp Court is the only court in Belgium/ Flanders that requires a certificate (i.e. the LIT certificate of KU Leuven, campus Antwerp) for a candidate to be sworn in. All other courts apply different rules and standards. Without a national register and official standards for inclusion in this register, ad-hoc interpreters can simply offer their «services» to another court. This means that Belgium still has a long way to go when it comes to awareness raising about the importance of using a qualified, professional legal interpreter to guarantee equal access to justice, let alone legal interpreters especially trained in working with children.

To end on a positive note, however, it must be said that next to the legal interpreter training, training of legal actors on how to use interpreters has since also been initiated a few years ago: in the police academy and during workshops or specific training sessions, legal actors (magistrates, lawyers etc.) receive training on how to work with an interpreter and on what (not) to expect from this person that «enters into» the communication process.

3.2.2. Analysis of the Narratives: the interpreters

When reading the additional comments made by respondents (that further illustrate their (dis)agreement with possible initiatives of the interpreter to explain either socio-cultural differences or technical terminology), they clearly confirm what has been stated before in this contribution: interpreters struggle to carry out their professional role against a reality that is much more complex than what a contract stipulates. Interpreters are very careful and try to strike a balance. One interpreter explains (in a sentence full of hedges) why he has chosen the «neither agree nor disagree»- answer:

I gave these two neutral answers because sometimes it is possible to ask the person who is in charge of the interview permission to explain things.

Furthermore, they try to explain that putting theory into practice is «not that simple», again underlining the tight-rope they are on:

Even though it is not allowed, in practice it is sometimes different. Without additional explanation, communication simply becomes impossible!

Or indicate that, without any further explanation from them, the other participant(s) in the interview may think that potential problems are the result of a lack of professionalism on the part of the interpreter:

As an interpreter you sometimes have the feeling that some nuance is necessary, e.g. when an interviewee gives an answer to a different question than the one asked. It then seems as if the interpreter translated the wrong question or answer, or made a translation mistake!

As for the needs expressed by the interpreters, these can be summarised as follows (the comments between inverted commas are again of Belgian interpreters): their first key suggestion is to take more time, especially before the interview by having a thorough briefing because «a thorough briefing improves the interpreting quality»; and also during the interview to be able to «immerse oneself» in the conversational context, to become part of it and get used to the specific characteristics of the children being questioned. Secondly, they plead for training: not only for the interpreters themselves, who should «all take a course in child psychology» for instance, but also for all parties involved because «good agreements in order to know who is doing what and to understand why somebody is doing things in a particular way» are necessary. This again indirectly refers to the need for a briefing before the actual interview starts.

3.2.3. Analysis of the Narratives: the legal practitioners

It is striking – though not surprising – to see that legal practitioners are much more categorical about what an interpreter should (not) do:

The interpreter must translate literally what I say and what the minor says without «interpretation»

or

In Belgium a suspect or victim has the right to ask the police for a verbatim report of a declaration. This must also be possible in an interpreter-mediated context.

From these comments it becomes clear that legal practitioners understand «literal» as meaning «word for word», and are unaware of the fact that there is no one-to-one correspondence between any pair of languages.

Others use a more balanced wording and are aware that interpreting is not an easy machine-like task, but also stress that they want to remaining in charge of the interview:

The interpreter must interpret as literally as possible but the question should also be clear to the minor. The interpreter cannot take initiatives but can make some suggestions to the interviewer. It is the policeman who then decides if he agrees with it or not.

Several legal practitioners suggest that it is possible to discuss socio-cultural issues before questioning, i.e. during the briefing; they are conscious of the fact that the interpreter is more than a mere «translation machine»:

An interpreter is there to enhance communication between the minor and the interviewer. He is allowed to give me some explanations about socio-cultural elements, but NOT during the questioning, he can do this before.

However, they seem to forget that conversations, let alone the attitude or thoughts of a child, are not entirely predictable!

Some legal practitioners are more flexible and think that an interpreter can point things out if some elements have to be clarified and some are even willing to accept that the interpreter may clarify things «concerning both terminology and socio-cultural differences». Some add a condition to the premise that the interpreter can explain «certain things that are different according to the culture»: i.e. the condition that the interpreter must be «from the same culture».

These narratives clearly suggest that the role of the interpreter is not always clear to legal practitioners: it is described in a variety of ways ranging from «translating literally and nothing more», to merely «pointing out socio-cultural or terminological issues«– preferably during the briefing before the actual interview – while still allowing the interviewer to remain in charge, and ultimately to leaving things up to the interpreter’s common sense. They all seem to forget that communication is a complex phenomenon which can even create misunderstandings between people who are speaking the same language in a «standard» conversation. Now imagine the level of complexity in an interpreter-mediated interview of a traumatized child who feels threatened and in addition finds himself in an unfamiliar environment where a «strange» language is spoken.

After analysing the needs expressed by the legal practitioners, we can say that they are manifold: key aspects are 1) the need for more time, 2) a code of ethics, 3) the interpreter’s linguistic knowledge and role boundaries, 4) the interpreter’s professionalism and expertise in working with minors, but most of all 5) the need for training.

The need for more time is illustrated in the following quote:

With regard to the questioning at the police station: more time for the meeting before the interview. Half an hour is too short to brief the interpreter and conduct the entire interview.

It is also suggested that interpreters should have a specific code of ethics for working with children, or that a group of professional interpreters should be created who are «specialized in interpreting for minors, especially for victims and witnesses».

Furthermore, legal practitioner respondents clearly state that interpreters should master the foreign language and Dutch perfectly and that there is a great need to further promote awareness of their role boundaries. This idea is expressed in a very clear and logical way in the following respondent’s statement, where instead of the term «literal» translation such descriptions as «without adding any suggestions» or «translating as correctly as possible» are used:

We should make clear why the interviewer’s questions only need to be translated, without adding any suggestions in the translation because the interpreter thinks that the child will better understand it that way. The interviewer often uses a specific question to be able to ask in-depth questions afterwards, without suggesting anything in the first question. It is a human reaction: the interpreter sometimes can’t help but make things more clear, but it is the task of the interviewer to check if the question is understood or if further clarification is needed. The interviewer will do this. Translating questions and answers as correctly as possible is very important because some nuances can make a difference for the development of the investigation.

This is clearly a plea urging that the interpreter respect the decisions of the interviewer and it is logical that the most important strategy required to meet these needs is training: not only general training for interpreters, but also specialized training in legal terminology. Furthermore, the need for specific training for interpreters about interview techniques and even more specialized training in working with children is very frequently stressed in dozens of narratives. Some examples:

- training in interview techniques:

specific training in interviewing techniques and communication with minors

through the design of training( for interpreters ) about the non-suggestive interview protocol used by the police

instruct interpreters about the techniques of audio-visual questioning - training in working with minors:

Specific training for interpreters who work with minors, since minors (especially victims) are always questioned in an audiovisual interview room

Training about child development (for all ages) in order to better understand their reactions

One comment is very explicit and the respondent was clearly upset by the fact that interpreters lacked the necessary professionalism, when it comes to impartiality and keeping a distance:

Better training of interpreters: nowadays it appears to be enough to have some knowledge of the language. I encountered interpreters who refused to translate what the minors said because it was not ‘decent’ according the personal standards of the interpreter! Another interpreter was biased and translated the words of the minor with a certain contempt. There is often a problem with Roma interpreters: they often know each other and they do not dare to say anything.

The legal actors point out that not only additional training for interpreters would be useful, but also training for themselves in order to learn to work with interpreters:

Best practice exercises for interpreter users: [so that] interviewers are well prepared and trained, know about cultural differences, know how to put the minor at ease and know how to speak through and work with an interpreter.

4. Conclusion

In this contribution only a very small part of the findings have been discussed since introducing a largely unexplored research domain and the related methodological issues would require a more extensive and detailed approach.

Nevertheless, we hope to have raised a certain degree of awareness, or at least taken the first step in that direction. Rome was not built in a day. We have uncovered some – serious – misunderstandings held by service users about the role of the interpreter that must be eliminated. But interpreters themselves also struggle with their role; they find it difficult to reconcile theory and (best) practice.

The first set of guidelines regarding some basic elements in ethics and general behaviour when interviewing children in the presence of an interpreter can be found in the recommendations flyer, all of which were formulated by our project consortium on the basis of the survey results. The five language versions of the flyer (namely English, Dutch, Italian, Hungarian and French) can be found at http://www.arts.kuleuven.be/home/english/rg_interpreting_studies/research-projects/co_minor_in_quest/recommendations. The flyers are freely accessible and every person interested can download and/or print them – and subsequently even translate them into other languages – and distribute them among stakeholders. Important items like the time requirement for professionally conducted interviews with a minor who does not speak the language of the interviewer, the need for a specific code of ethics for interpreters working with children and the importance of a thorough briefing are all elements that can be found in the above-mentioned leaflets.

With regard to further research and the development of best practices, it is also important to note that an overwhelming majority of interpreters and other professionals– at least in Belgium, but also in the other member states, as the research results show – are in favour of more specialized training, in working with minors to gain more insight into specific interviewing techniques (for the first group), or in working with interpreters (for the second group).

This means that there is still a long way to go, but at least the CO-Minor-IN/QUEST consortium has made the first move by starting to think about creating a better and more professional environment for children who find themselves in a threatening and «unfamiliar/strange» setting (e.g. a police station), because they have gone through an even more traumatizing experience before. The high response rate to the questionnaire shows that this area of concern needs further research to attain best practices in child interviewing, through constructive teamwork.

References

Angelelli, C.V. (2001) Deconstructing the invisible interpreter: a critical study of the interpersonal role of the interpreter in a cross-cultural/linguistic communicative event. Unpublished Ph. D. thesis, Stanford University.

Angelelli, C.V. (2004) Revisiting the Interpreter’s Role. A study of conference, court and medical interpreters in Canada, Mexico and the United States. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: J. Benjamins.

Guckian, E., and Byrne, M. (2010-2011). «Best practice for conducting investigative interviews». The Irish Psychologist, 37/2-3, 69-77.

Jaskiewicz-Obydzinska, T., and Wach, E. [no date]. The cognitive interview of children. Kraków: Institute of Forensic Expert Opinions.

Lamb, M.E., Orbach, Y., Hershkowitz, I., Esplin, P.W., & Horowitz, D. (2007). «Structured forensic interview protocols improve the quality and informativeness of investigative interviews with children: A review of research using the NICHD investigative interview protocol». Child Abuse & Neglect, 31/11-12, 1201-1231.

Llewellyn-Jones, P. and Lee, R.G. (2014) Defining the Role of the Community Interpreter: the concept of ‘role-space’. London-New Delhi-New York-Sydney: Bloomsbury.

Hale, S. and Napier, J. (2013) Research Methods in Interpreting. A practical Resource. London-New Delhi-New York-Sydney: Bloomsbury.

Matthias, C., and Zaal, N. (2002). «Hearing only a faint echo? Interpreters and Children in Court». South African Journal on Human Rights, 18/3, 350-371.

Metzger, M. (1999). Sign Language Interpreting: Deconstructing the Myth of Neutrality. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Pöchhacker, F. (2004). Introducing Interpreting Studies. London and New York: Routledge.

Rosiers, A., (2006) «Zoeken naar een oplossing: een proefproject in Antwerpen» In Vanden Bosch (ed.) Recht & Taal. Rechtszekerheid voor de anderstalige rechtzoekende, Antwerpen – Oxford: Intersentia, 49-60.

Roy, C. (1993) ‘The problem with definitions, descriptions and the role metaphor of interpreters’. Journal of Interpretation, 6, 127-153.

Roy, C. B. (2000) Interpreting as a Discourse Process. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schollum, M. (2005). «Investigative interviewing: the literature». Review of investigative interviewing. Wellington: Office of the Commissioner of Police.

Scurich, N. (2013). «Questioning Child Witnesses». The Jury Expert, 25/1, 1-6.

UK Home Office (2000). Achieving best evidence in criminal proceedings: guidance for vulnerable or intimidated witnesses, including children (consultation paper). London: Home Office Communication Directorate.

Valero-Garcés, D. and Martin, A. (eds) (2008) Crossing Borders in Community Interpreting. Definitions and dilemmas. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: J. Benjamins.

Wadensjö, C. (1998) Interpreting as Interaction. London: Longman.

On line resources

Alcalá conference website: http://tisp2014.tucongreso.es/en/presentation [accessed 15-09-2014]

CO-Minor-IN/QUEST leaflets with recommendations: http://www.arts.kuleuven.be/home/english/rg_interpreting_studies/research-projects/co_minor_in_quest/recommentations [accessed 15-09-2014]

Directive 2010/64/EU: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1410463884876&uri=CELEX:32010L0064 [accessed 15-09-2014]

Directive 2012/29/EU: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1410870539096&uri=CELEX:32012L0029 [accessed 15-09-2014]

ImPLI project: http://www.isit-paris.fr/documents/ImPLI/Final_Report.pdf [accessed 15-09-2014]

NICHD protocol: http://nichdprotocol.com [accessed 15-09-2014]

Council of Europe (2011). Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child friendly justice and their explanatory memorandum. [on line] [Accessed: 11 August 2014]: http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/childjustice/Guidelines%20on%20childfriendly%20justice%20and%20their%20explanatory%20memorandum%20_4_.pdf

Council of Europe and European Parliament, IPEX (European Platform for Interparliamentary Exchange) regarding the proposal for Directive on procedural safeguards for children suspected or accused in criminal proceedings (COM/2013/0822): http://www.ipex.eu/IPEXL-WEB/dossier/document/COM20130822.do

United Nations (1959). Declaration of the Rights of the Child. [on line] [Accessed: 11 August 2014: http://www.un.org/cyberschoolbus/humanrights/resources/child.asp

United Nations (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty Series: Treaties and international agreements registered or filed and recorded with the secretariat of the United Nations, vol.1577. [on line] [Accessed: 11 August 2014]: http://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/UNTS/Volume%201577/v1577.pdf

UNCRC . UN Convention on the Right of the Child. FACT SHEET: A summary of the rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child: http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/impact/ia_carried_out/docs/ia_2013/com_2013_0822_en.pdf

UK Ministry of Justice (2011). Achieving best evidence in criminal proceedings: Guidance on interviewing victims and witnesses, and guidance on using special measures. [on line] [Accessed: 11 August 2014]: http://www.cps.gov.uk/publications/docs/best_evidence_in_criminal_proceedings.pdf

Van Schoor, D. (2013). Interpreter-mediated interviews of child witnesses and victims: status quaestionis. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, KU Leuven/Thomas More, Antwerpen. [on line] [Accessed: 11 August 2014]: http://www.arts.kuleuven.be/hub/tolkwetenschap/projecten/co_minor_in_quest/interpreter-mediated-interviews-of-child-witnesses-and-victims-status-quaestionis

1 Directive 2012/29/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime: Article 2(c)

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child: Article 1

Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child friendly justice (2010): Article II (a)

2 Issued by the UK Ministry of Justice (2011). Its earlier version entitled Achieving best evidence in criminal proceedings: guidance for vulnerable or intimidated witnesses, including children was issued by the UK Home Office in 2000.

3 An English version of the complete questionnaire can be consulted on the website of the Interpreting Studies Research Group of KU Leuven, campus Antwerp (http://www.arts.kuleuven.be/home/english/rg_interpreting_studies/research-projects/co_minor_in_quest/questionnaire).

4 The following codes were used: (1) Northern Italy – (2) Central Italy – (3) Southern Italy and islands – (4) England (UK) – (5) Wales (UK) – (6) Scotland (UK) – (7) Northern-Ireland (UK) – (8) Flanders (BE) – (9) Wallonia (BE) – (10) Brussels (BE)