:: TRANS 29. ARTÍCULOS. Págs. 147-177 ::

The Role of Translation Paratexts in the Representation of the Other: Annotation and Iconographic Aspects in the Spanish Editions of The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon*

-------------------------------------

Alba Serra-Vilella

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

ORCID: 0000-0002-0705-308X

María Teresa Rodríguez Navarro

Universidad de Granada

ORCID: 0000-0002-2417-7826

-------------------------------------

The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon is a classical Japanese text that has been published in Spain in four different translations, three into Spanish and one into Catalan. The paratexts display considerable differences in the presentation of the Other. This paper, therefore, aims to shed light on the images shaped by the translators and publishers. In addition, the factors that may be related to a domesticating or exoticizing image in the corpus of notes are examined. The results show that time and the translator’s degree of expertise and cultural knowledge, as well as their visibility are all factors related to the type of image that is offered.

KEY WORDS: Translation, Japanese literature, cultural images, paratexts, Makura no sōshi.

El papel de los paratextos de las traducciones en la representación del Otro: Notas e iconografia en El libro de la almohada de Sei Shōnagon en España

El libro de la almohada de Sei Shōnagon es un texto clásico japonés que ha sido publicado en España en cuatro traducciones diferentes, tres al español y una al catalán. En los paratextos se observan grandes diferencias en la presentación del Otro, por lo que este estudio pretende mostrar las imágenes que los traductores y editores conforman. Además, se investigan los factores que pueden tener relación con una presentación domesticante o exotizante en un corpus de notas. Los resultados confirman que el paso del tiempo, el nivel de conocimientos culturales y experiencia del traductor y su visibilidad son factores relacionados con la imagen que se ofrece.

PALABRAS CLAVE: traducción, literatura japonesa, imágenes culturales, paratextos, Makura no sōshi.

-------------------------------------

recibido en octubre de 2024 - aceptado en julio de 2025

-------------------------------------

1. IntroducTION

The study of paratexts provides a lot of information about the translation process, and also on the text and its presentation by the different agents (publisher, translator, cover designer...) and their implicit discourses. For this reason, a relatively new field of study has emerged, and a new term has even been coined. “Paratranslation” highlights the importance of paratexts in the process of translation, both those of the source text (ST) and of the Translated Text (TT) (Yuste Frías, 2011).

There were several reasons for our choice of the Makura no sōshi (The Pillow Book) by Sei Shōnagon for our analysis; the fact that it is a book written by a woman, for example, with a large time interval between the ST and TT, and that has several translations and editions for the purposes of comparison. In Spain, four different translations have been published.

The main aim of this paper is to analyse the image of the Japanese Other offered in the paratexts, and the factors related to it, such as time, the translator’s expertise in the Japanese language and culture, and the agents involved (translator, publisher...). The second aim is to analyse the visibility of the translators in the paratexts and to check whether this degree of visibility can be related to some orientation in the presentation of the Other. The third aim is to compare the different paratexts (visual, textual) and verify whether there is harmony or disharmony between them in how they present the Other (Torres-Simón, 2013).

The aim of this paper is not to value which translation or which approach is better, but to analyse and shed light on the subtle mechanisms that define the representation of the Other.

Our hypotheses are related to the aforementioned aims. We consider that newer translations represent the Other in a more meaningful way, avoiding exoticisation, while older ones tend towards excessive domestication or exoticisation, in accordance with the Retranslation Hypothesis (Chesterman, 2011). Hence, the newer translations will show more harmony between the different paratexts and the book content and context. We think that a translator with a deep knowledge of the source culture is more prone to taking a familiarising approach, narrowing the gap between both cultures. Thirdly, we think that a translator whose translation conforms with the TT culture represents the Other as “the same” (erasing the differences) or as extremely different (exotic), and therefore tends to be more visible, while a translator that aims to emphasise the ST culture and therefore make it accessible to the reader tends to be more invisible.

This paper is organised in three main sections. After the theoretical and methodological framework there is a section about the ST, the author, the translated texts and the translators. The next section analyses translator visibility, and the third one delves into paratexts, with three subsections: visual paratexts, textual paratexts and notes.

2. Theoretical and methodological framework

Paratexts are the elements that accompany the main text in a book, such as the title, the cover, prefaces, notes, illustrations… They are “an ‘undefined zone’ between the inside and the outside” of a book (Genette, 1997, p. 2). Paratexts offer a large amount of information on the skopos (Reiss & Vermeer, 1996) of a translation, and may reveal harmony or disharmony with the content of the book (Torres-Simón, 2013), due to the (sometimes unconscious) ideologies of the different agents involved. The main agents are the publisher, who, among other elements, usually decides on the cover design, and the translator, who is the author of the prologues and notes in the corpus of this study. We therefore also consider it relevant to delve into the visibility of the translator (Venuti, 1995).

This essay is mainly focused on paratexts, more precisely the peritexts, those that are attached to the book itself. For the analysis of the image of the Other, we classified peritexts in three categories: visual paratexts, textual paratexts (prologues, backcovers, annexes...) and notes (footnotes or endnotes). Although notes are also textual elements, we deemed it relevant to analyse them separately due to their close relationship with the translated text.

Japanese culture has long been considered distant and exotic, and stereotypes abound in the presentation of the Japanese Other, with many overlaps with the ideas of Orientalism (Said, 1978), as previously mentioned in other studies (Rodríguez Navarro & Beeby, 2010; Rosen, 2000; Serra-Vilella, 2022).

Lawrence Venuti (1998) establishes a difference between an ethics of sameness or ethics of difference, while Carbonell establishes a more detailed proposal, taking into account relations of power and Orientalism. The foreignisation method that Venuti defends aims to visibilise the differences in order to allow a more authentic approach to the Other, avoiding domestication, which would erase the difference. Nevertheless, Ovidi Carbonell (2003, p. 153) does not recommend the foreignisation method for cultures “that fall within the ‘exotic’ category and whose translation tradition has made of foreignisation a basic tool of appropriation and exotic categorisation”. Thus, the contribution of Venuti is valuable in the context of a dominant culture such as English, but it cannot be applied to all cultures.

We used four categories to classify the possibilities of representation of the Other, and its relation with the target culture combining the theories by Venuti (1998) and Carbonell (2004). The latter establishes four possibilities by combining the concepts of “same” and “other”, which were used as our conceptual framework. To analyse the cultural Otherness presented in the notes, we use the following terms:

- Domestication: presenting the Other as “same”, hence erasing the differences.

- Familiarisation (or hybridisation): the Other is presented as different but not so much as to be impossible to understand (also categorised as “not-other” by Carbonell).

- Exoticisation: the Other is shown as strange or exotic (also categorised as “not-same” by Carbonell).

- Emic concept: the Other is completely different and impossible to understand.

We use these categories to analyse the image of the Other in the paratexts, although the emic concept is barely mentioned, as we believe that even a word left in Japanese with no explanation and which the reader cannot understand will have an effect of encountering something “strange and exotic”. Carbonell’s approach was designed for the analysis of translations, and, although we deal mainly with paratexts, we found his categories useful for analysing the image of the Other, since the Japanese culture is one that has often been subject to exoticisation.

Regarding the content of the notes, we used Salvador Peña and María José Hernández’s classification (1994, pp. 37-38):

- Setting notes: references to places or time

- Ethnographic notes: aspects of everyday life of the source community

- Encyclopaedic notes: references to data about the world

- Institutional notes: about conventions and institutions of the source community

- Metalinguistic notes: about wordplays or other uses of the code

- Intertextual notes: references to other texts

- Textological notes: in classical texts, references to different editions of the source text

We chose one note of each type and compared how it is presented in each of the translations (although not all texts include all note types). We noted that ethnographic and intertextual notes are the most common, and among those, the former tend to be longer and contain more subjective statements (depending on the version). For this reason, we compared five more ethnographic notes to analyse how they present the Japanese Other.

Lastly, given that the original work under analysis has undergone multiple translations, it is pertinent to briefly define the term “retranslation” and examine the motivations underlying this practice. As Yves Gambier (1994, p. 413) notes, the term has been employed with different meanings. Some scholars, for instance, use it to refer to translations based on a previous translation—more commonly referred to as “indirect translation”. However, the first definition offered by Gambier describes retranslation as the translation of a text that has already been rendered into the same language. This definition aligns with the concept used by several scholars, including Sharon Deane-Cox (2014) and Andrew Chesterman (2011), among others.

Since retranslation may appear to be a redundant activity, it is worth exploring the motivations that lead to new translations of the same text. It is remarkable in this field the Retranslation Hypothesis, which posits that “later translations of a given text into a given target language tend to be closer to the original” (Chesterman, 2011, p. 69). Although this hypothesis has been contested by numerous authors, as we can see in several case studies included in Enrico Monti and Peter Schneider (2011), this study seeks to assess its applicability to the case at hand.

Susanne Cadera (2017, p. 9) highlights the role of ideology and the cultural values of both the source and target cultures in the retranslation process, beyond purely linguistic considerations. Similarly, Gambier points to the historical dimension inherent in the emergence of new translations: “the times changed” (1994, p. 414). It may be the case that initial translations tended to reduce the “otherness” (and were therefore domesticating) whereas subsequent versions attempt to return to the source text (1994, p. 414).

An additional aspect worth considering is the rationale behind the selection of particular texts for retranslation. As noted by Cadera and Walsh (2017), one such reason may lie in the high literary value attributed to the authors that form part of the generally accepted literary canon. While this may not apply in every case, it appears relevant in the present study, as Sei Shōnagon is widely regarded as one of the most prominent writers of the “golden age” of classical Japanese literature.

3. Source text, author and context

Makura no sōshi (枕草子) is one of the most outstanding works of classical Japanese literature, written by Sei Shōnagon in the 10th century (Heian period). This book is an important source of information on court life during the Heian period, and it is a text of great literary beauty, full of lively anecdotes, intertextuality and comments. It was Sei Shōnagon’s chief work. It seems to be her personal diary, as it was customary to keep such writings under a wooden pillow. This is one of the interpretations on the title of the book, which has been widely translated as “The Pillow Book”.

The work was written in hiragana, a Japanese syllabary, except for names and places, since women were expected to learn only this writing system, while Chinese characters were studied by men (Sei Shōnagon, 2014, pp. 10-11). The most outstanding aspect of her diary is her wise and ironic opinions and comments on many facts and events of life in the Heian court. The original manuscript seems to have disappeared before the end of the Heian period, and there are many successive versions by different scholars (Rubio, 2007; 2021).

Sei Shōnagon is among the greatest writers of prose in the history of Japanese literature. She was the daughter of the poet Kiyohara no Motosuke. Thanks to her father’s high rank in court she entered the Imperial Palace as one of the ladies-in-waiting of Empress Fujiwara no Sadako. When the Empress died, she remained in the court for some years, and therefore became a Buddhist nun (Kato & Sanderson, 1997).

The Heian period (794-1185) began when the Imperial court moved from Nara to Heian-kyo, which means the town of Peace and Calm (modern Kyoto). In those days, life in the court was all about joy, luxury and refinement for the pleasure of aristocrats and emperors. It was also a time of the Chinese culture’s “japanisation”, having entered Japan, along with the Chinese writing system, from the 4th century (Shirane, 2012; Shirane et al., 2016).

4. Target texts

The first translation into English, by Arthur Waley in 1928, was titled The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon, but it was just a selection of fragments from the original text. In 1934, it was translated into French by André Beaujard, and the first complete translation into English was by Ivan Morris in 1967. In this study we analyse the four translations published in Spain in book format, presented in Table 1 (see next page).

Table 1. Summary of basic information of the translations published in Spain

| Title | El libro de la almohada | Quadern de capçalera | El libro de la almohada | El libro de la almohada |

| Translator | Jorge Luis Borges and María Kodama | Xavier Roca-Ferrer | Amalia Sato | Jesús Carlos Álvarez Crespo |

| Publication date | 2004 | 2007 | 2009 (previously in Argentina, in 2001) | 2021 |

| Publisher | Alianza | RBA | Adriana Hidalgo | Satori |

| Country | Spain | Spain | Spain | Spain |

| Language of publication | Spanish | Catalan | Spanish | Spanish |

| Intermediary language (if any) | English | French and English | English | Direct from Japanese |

| Authorship of the notes | Not specified* | Xavier Roca-Ferrer | Amalia Sato | Jesús Carlos Álvarez Crespo |

| Authorship of the prefaces | María Kodama | Xavier Roca-Ferrer | Amalia Sato | Jesús Carlos Álvarez Crespo |

| Reeditions | 2005, 2015 | 2014, 2022 |

*Although the authorship of the notes is not explicitly stated, after comparing them with the mediation translation, we think that they were made by the Spanish translators based on the information contained in the English translation by Morris (Sei Shōnagon, 1971).

Apart from these translations published in Spain, we have knowledge of a direct translation of the entire text published in Peru (Sei Shōnagon, 2002), carried out by Iván Pinto Román and Osvaldo Gavidia Cannon, with the collaboration of Izumi Shimono. There are also two partial translations, one by Jessica Freudenthal, in Bolivia (Sei Shōnagon, 2006), and another by Kazuya Sakai (Sei Shōnagon, 1969), and also two translations that only include certain passages in anthologies of Japanese literature (Henitiuk, 2012), by Mercè Comes (Revon, 2000) and Javier Sologuren (1993).

Regarding the source languages of the translations, the edition by Borges and Kodama does not explicitly reference the ST, but mentions Morris and Waley’s translations into English. Kodama also mentions Borges’ complaints about not knowing the Japanese language (Sei Shōnagon, 2004, p. 18). It is, therefore, clearly an indirect translation. The translation into Catalan by Roca-Ferrer was based on French and English sources (by Beaujard and Morris), and he mentions that he also took into consideration a German translation by Mamoru Watanabe. In the version by Sato there is a preliminary note by the publisher that asserts that Morris’ English version and the intralingual translation into modern Japanese by Satoshi Matsuo and Kazuko Nagai were both used. It therefore seems to fall somewhere between a direct and indirect translation. However, it is our belief that the English version was the main source, due to her assertion that she always needs help to translate from Japanese because she cannot use the Japanese language by herself (Vives, 2006). The only direct translation from Japanese published in Spain is that of Álvarez Crespo, which was based on the edition by Matsuo and Nagai (Sei Shōnagon, 2021, p. 20).

Álvarez Crespo’s translation constitutes a paradigmatic case of retranslation, as its motivations align with the Retranslation Hypothesis, as outlined in the Theoretical Framework. In his preface, the translator demonstrates an awareness of earlier versions and expresses his aim to offer a more complete and authentic rendering of the original, given that previous Spanish editions were mediated through English.

However, regarding Borges and Kodama and Sato translations, it is difficult to determine which one was produced earlier. The first one published in Spain was that by Borges and Kodama (2004), but Sato’s one appeared previously in Argentina, in 2001. However, considering that Borges passed away in 1986, his translation must have been completed well before Sato’s one.

On the other hand, Roca-Ferrer’s translation would not be classified as a retranslation, as it represents the first rendering of the text into the Catalan language.

Of the four translations, the only complete ones are those of Álvarez Crespo and Roca-Ferrer, followed by Sato’s translation, which claims to be complete, but doesn’t include some of the lists (like Morris). The Borges and Kodama translation is a selection of fragments, as stated in the preface (Sei Shōnagon, 2004, p. 18).

The following section contains short presentations of the editions, along with their translators and paratexts, in chronological order based on the year they were first published in Spain.

4.1. Translation by Borges and Kodama

Borges, the Argentinian writer, enjoyed literary translation and had deep interest in Japan. In the 1930s, he reviewed Waley’s version of The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu.

Kodama, born in Buenos Aires to Japanese-German parents, was Borges’s student and subsequently became her personal secretary. They married in 1986. They translated together several works, including Anglo-Saxon and Icelandic literature, and these selected texts from The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon. She was also a university professor and photographer.

The Spanish translations are entitled “El libro de la almohada” (literally “The Pillow Book”), following the English title.

Apart from the cover, this edition’s main paratexts are the introduction and the endnotes (171 in total). Kodama’s introduction refers to the Japanese author’s “internal freedom” and states that Borges was an ideal communicator of Sei Shōnagon’s literature due to his own magnificent poetic prose (Sei Shōnagon, 2004, p. 12).

4.2. Translation into Catalan by Roca-Ferrer

Xavier Roca-Ferrer has a PhD in Classical Philology. He neither speaks Japanese nor is a Japanese specialist, but he has experience translating classical works from Latin, English and German, and also other Japanese Heian literature. He translated Genji Monogatari into Spanish and Catalan (Murasaki Shikibu, 2005; Murasaki Shikibu, 2006) and Diaries of Heian-court Ladies (Murasaki Shikibu et al., 2007).

The Catalan title is not a literal translation of the Spanish or English, but is based on the French edition Notes de chevet and also on a book written by a prominent Catalan author (Quadern gris by Josep Pla), as part of a strategy of intertextuality (Sei Shōnagon, 2007, p. 20).

In the Catalan edition there are a lot of peritexts: a note about the author in the flap, an introduction, “about the translation”, “dramatis personae”, an appendix with six sections (the Heian civilisation, Heian spirituality, Women and marriage, Dolce vita, Women’s literature, the Heian calendar), a one-page note about the translator and also footnotes (295 in total).

4.3. Translation by Sato

Amalia Sato is a professor of Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. She was editor of the literary journal Tokonoma. Traducción y Literatura from 1999-2006. As a translator, she collaborates in journals such as “Suplemento Cultura” in Clarín (Argentina), Japónica (Mexico), etc.

In 2022 a new edition of Sato’s translation was published by A. Hache (a new name of the publisher Adriana Hidalgo) in Buenos Aires, the same publishing house of the first 2001 edition. While the visual paratexts of the latest edition (2022) are quite different to the previous ones, the textual elements are the same: a prologue by the translator, a publisher’s note, the flaps and the footnotes (205 in total). Although epitexts (paratexts outside of the book) are not the object of this study, Sato has her own website which contains interviews and information about her work, including a conference on Heian period literature (Sato, 2020).

4.4. Translation by Álvarez Crespo

Jesús Carlos Álvarez Crespo studied Japanese in Barcelona and has been living in Japan since 1992, working for NHK and the Keio and Seisen universities (Satori, n.d.). He has translated 14 books from Japanese and has edited a Japanese-Spanish dictionary.

His translation was published by Satori (a relatively new publishing house specialised in Japan) and contains a high number of peritexts. There is a prologue which includes eight subsections (biography of Sei Shōnagon, social background of the Heian period, versions of the original text, interpretations on the title, ST for this edition, translations into Spanish, Makura no sōshi emaki, translation guidelines), and a dedication. After the main text, 10 annexes are included (which occupy more than 70 pages and include several illustrations), on the following topics: animals, positions and classes, carriages, colours and attire, time and directions, court ranks, characters, plants, provinces and “vocabulary”. There is also a bionote on the author, an index and a list of other classical literature in the same collection. There are a total of 949 footnotes.

5. Translator’s visibility

On the front covers, the name of the translator appears in Borges and Kodama and Roca-Ferrer’s translations, and in Sato’s 2022 edition. It is not present, however, in the previous editions of Sato’s translation or in the one by Álvarez Crespo. It is worth noting that the two translations closest to the original (one direct and one indirect, but checked alongside the Japanese version) invisibilised the translators, although, in Sato’s case, this changed with time. Translating a classical text directly from Japanese requires a high degree of expertise, and therefore a higher level of acknowledgement would be expected. In the translation by Borges and Kodama, the fame of the former must certainly have influenced the decision to include his name on the cover.

Roca-Ferrer’s edition offers a one-page bionote on the translator inside the book, while the other translations contain no such text. In Borges’ translation, he has no presentation, but the author of the prologue, Kodama, mentions him many times, while she remains invisible and does not explain her role in the translation process.

In the prologues and notes, different degrees of visibility are found. The translator may be visible through commentaries about the translation process, subjective opinions and on the selection of information, among other aspects.

In Borges and Kodama’s translation, the author of the prologue, Kodama, mentions Borges many times (almost in every paragraph), including his motivations for doing this translation. On the other hand, there is no information about Kodama. The fact that the book is a selection of fragments made by the translators, as Kodama explains in the prologue, is a clear sign of their visibility. Translation notes are in the end of the book, while in the other translations footnotes are used. This gives less visibility to the translator and the fact that the text is a translation. This connects with Borges’ idea on translation, which he sees as the creation of a new text, and, according to Sergio Waisman (Friera, 2005), the value of a translation is to produce a creative work rather than being loyal to the ST.

In Roca-Ferrer’s prologue, he talks about the author and the context of the ST, and, though he mentions the process of translation only once, many opinions and subjective commentaries 1 can be found, along with some colloquial expressions 2, thereby giving him strong visibility. He is also highly visible in his translation, in which he is not actually mentioned as translator, but rather as the “author of the version”. The use of the word “version” instead of “translation” could be indicative of the concept of the “impossibility of translation”, which can be also seen in some of his footnotes 3. There is also a footnote that talks about the translators of the source texts (see the textological note in the Appendix). This direct allusion to “the translators” is somewhat unexpected, transporting the reader from the literary text to the work of the translator. There are also commentaries about translation strategies, as in the example of the encyclopaedic note in the appendix, and personal opinions of the translator which are very subjective 4.

In the prologue by Sato, the translator is scarcely visible. She accurately explains the literary context in Japan since the 7th century and especially the writing system changes in the Heian period, life in the court and its values and court ladies that dedicated their lives to literature. Sato also offers a short bionote of the author and some paragraphs on the reception of this book in Japan and worldwide. However, surprisingly she gives no explanation about the translation process, while the “Editor’s note” (Sei Shōnagon, 2014, p. 7) provides information about the ST and the mediation translations.

The prologue, as well as the notes and annexes, by Álvarez Crespo are fairly neutral and objective, including mostly facts rather than personal opinions. The one-page section on “translation guidelines”, focuses on conventions, such as romanisation style, name-surname order, etc., rather than the task of translation 5. Thus, although the translator is visible, the comments regarding his task are somewhat shallow. Overall, his visibility in the paratexts is very limited. Álvarez Crespo remains neutral even in passages of a highly surprising nature, such as in section 294 (Sei Shōnagon, 2021, pp. 309-310), in which a peasant desperately explains that his house has been burnt down, and the court ladies just joke and laugh at him. Here, Roca-Ferrer includes a footnote remarking that “contemporary readers could only be astonished at the total lack of social sensibility that this story reveals. The court ladies of Marie Antoinette would have shown more compassion [...]” [tr. by the authors] (Sei Shōnagon, 2007, p. 280).

To sum up, Borges and Kodama, especially the first, are highly visible on the cover and prologue, but not in the notes. Roca-Ferrer is highly visible in all the paratexts, while Álvarez Crespo and Sato are the opposite, being largely invisible, except for their name in the colophon, and on the cover of the newest edition (2022) and certain commentary on linguistic choices in the former’s section on the translation. Their invisibility may be related to a goal of being objective and perhaps to the idea that a good translation should not appear as a translated text.

6. Analysis of the image of the Other

In the next subsections we explore the images of the Other that are presented or implied in the paratexts, beginning with visual paratexts, then textual paratexts and finally notes.

6.1. Visual paratexts

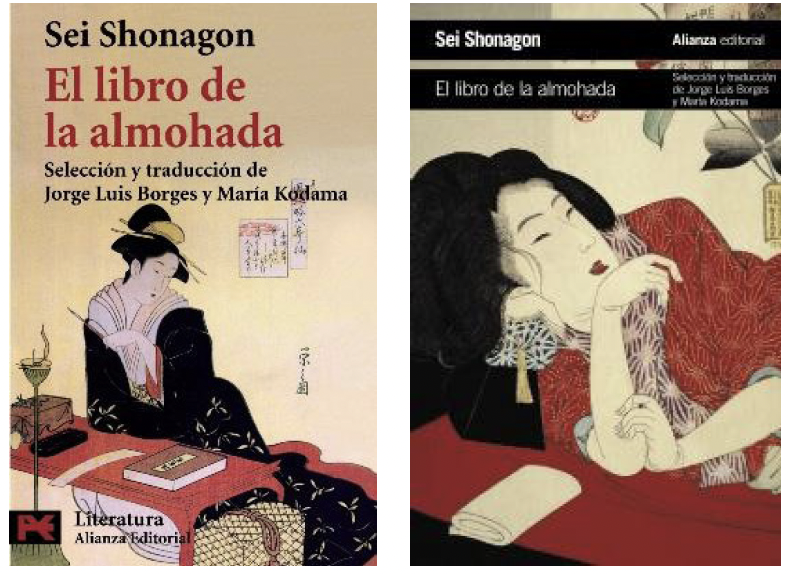

The cover for Borges and Kodama’s first edition (Figure 1) was designed by the publishing house. It reproduces a woodblock print from the Edo period by Chōbusai Eishi and is part of the collection entitled “six immortal poets”. It shows an elegant woman dressed in Edo style, holding a brush. There is a notebook on the table. It is interesting to stress that while the image of the cover depicts a woman writer, there is nothing about it that represents the Heian period. There is a new edition published in 2015 that depicts a woman lying on a sort of pillow, which may partly represent the content of the book. However, again, this woman is from the Edo period, and not the Heian period. Therefore, both covers display a partial disharmony between the cover and the content of the book.

Figure 1. Covers of the translation by Borges and Kodama

(Sei Shōnagon, 2004; 2015)

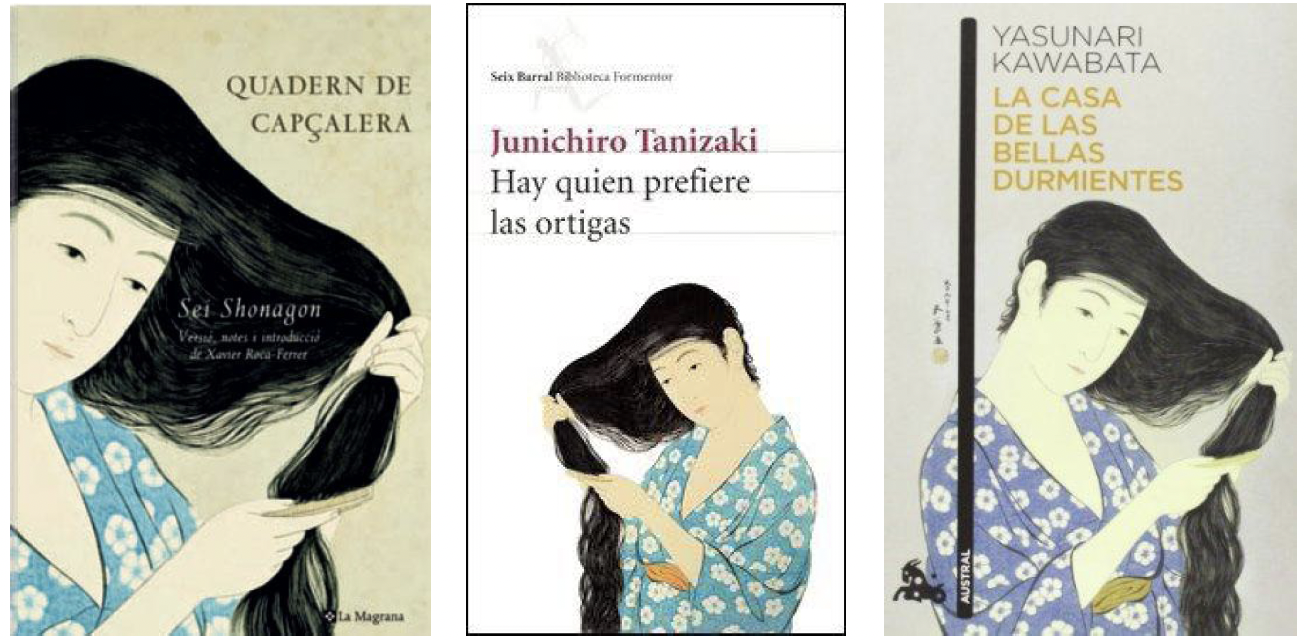

The cover image of Roca-Ferrer’s translation is a shin-hanga 6 by Hashiguchi Goyō: Combing the hair (1920). In the colophon, the creator of this image is not mentioned, only the name of the designer. The image shows a Japanese woman combing her hair. Although there is not a strong association with a time in history, the clothing clearly does not correspond to the time when the book was written. This timeless and idealised image of the Japanese woman could be considered to be an Orientalist presentation and represents a disharmony with the book’s content. What is most interesting is that the same image has been used for the cover of two other Spanish translations of Japanese literature (Figure 2): Some Prefer Nettles (Tanizaki, 2004) and House of the Sleeping Beauties (Kawabata, 2013). The use of the same image in two works of modern literature and one classical work reinforces the idea of its atemporality.

Figure 2. Cover of the Catalan translation by Roca-Ferrer (Sei Shōnagon, 2007)

and other covers with the same illustration (Tanizaki, 2004; Kawabata, 2013)

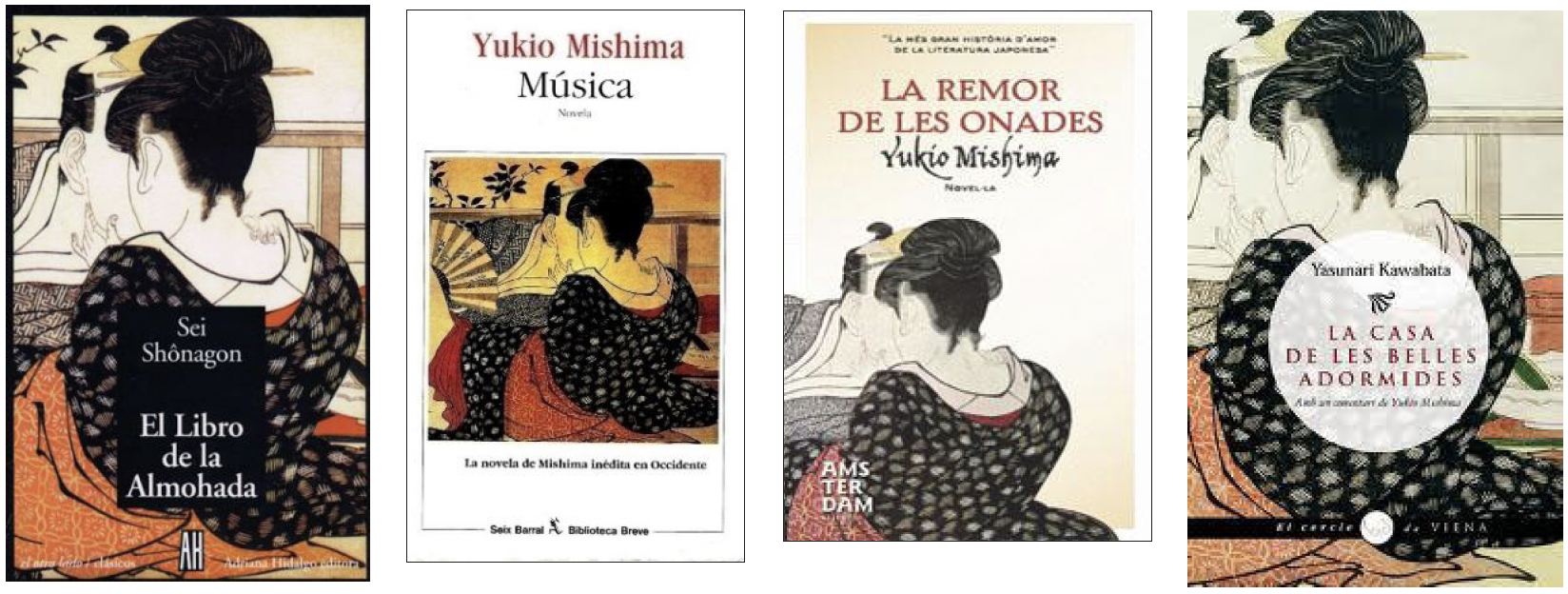

The cover of the first edition (2001) of Sato’s translation, published in Argentina but presumably also distributed in Spain, was designed by Eduardo Stoía and Pablo Hernández and has a fragment of a famous shunga or erotic painting from the Edo period, which shows a couple kissing (Figure 3). The woman is wearing a kimono and is showing the back of her head, her black hair worn up in the style of the Edo period, and the back of her whitened nude neck, a part of a woman’s body considered to be extremely erotic in Japanese culture. It is interesting to notice that this illustration does not represent the Heian period, but rather the Edo period. Furthermore, it is an erotic painting and the theme of this book is not particularly erotic (disharmony with the content). This may be due to the fact that Edo period paintings were more popular in the target community than those from the Heian period, and that the representation of Japanese women as erotic was more appealing to readers than one that portrays them as intellectual. This is an Orientalist image that aligns more closely with the imaginary that, even today, the target community envisages for Japan. It is also interesting to draw a reflection on the difference in the role of the author (Sei Shōnagon), who was an intellectual, and the role of the woman on the cover of this edition.

Figure 3. Cover of the first edition of the translation by Sato (Sei Shōnagon, 2001),

and other books that use the same illustration (Mishima, 1993; 2008; Kawabata, 2007)

The same image is used in three other books (Figure 3), two works by Mishima (Music, 1993, and The sound of Waves, 2008), and the Catalan translation House of the Sleeping Beauties by Kawabata (2007). These are contemporary works of literature, so there is a time gap of several centuries with the publication of Sei Shōnagon’s ST.

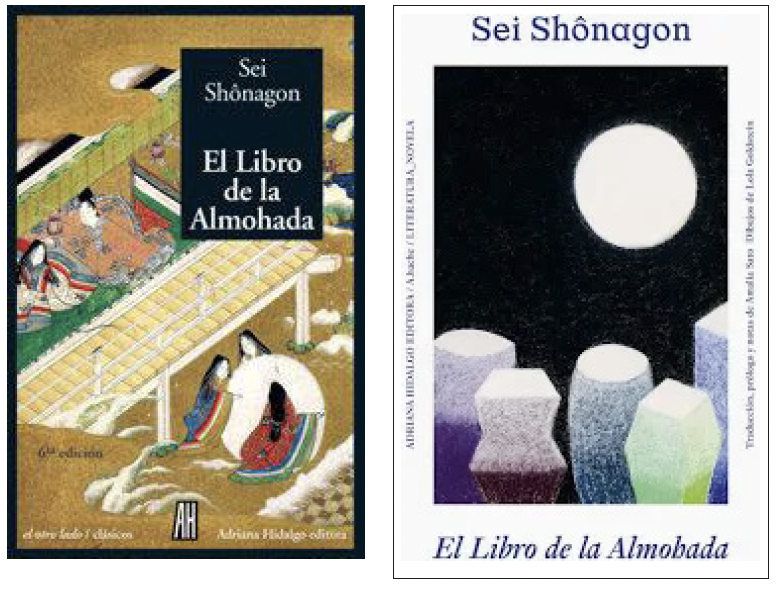

On the cover of the 7th edition in Argentina and 1st and 2nd editions in Spain (2009, reprinted in 2014), we observe a remarkable change (Figure 4). The former has been designed by Gabriela di Giusseppe and represents a print from the Heian period. Here, we can, therefore, attest to a harmony with the book’s content. The cover of the 2022 edition is again quite different to the previous ones. The drawings by Lola Goldstein represent a nighttime landscape, with a bright full moon against a black background, and figures with geometric forms in the bottom section, illuminated by the moon. We can observe that the editor, translator and artist are all very visible, mentioned on the cover, and that they are all women. This edition also includes 20 drawings by Goldstein in between the text, which seem to have more of an artistic than informative function, seemingly reflecting the artist’s free interpretation of the text. In addition, there is a portrait of the author by Gabriel Altamirano on the flaps, along with her biography.

Figure 4. Cover of the 2009/2014 and 2022 editions

of the translation by Sato (Sei Shōnagon, 2014; 2022)

The cover of Álvarez Crespo’s translation (Figure 5) includes an illustration by the Japanese artist Uemura Shōen (1875-1949), the first woman to join the Imperial Art Academy. Her drawings portrayed women in the bijin-ga style. Thus, the illustration is modern, but it represents the content of the book, since it portrays the author in Heian period clothes and a sudare (privacy curtain). Therefore, this cover shows a harmony with the content of the book and it empowers the author of the ST.

Figure 5. Cover of the translation by Álvarez Crespo (Sei Shōnagon, 2021)

Inside the book there are also some visual paratexts. The endsheets are decorated with fullpage paintings of Heian period court scenes, in magenta monochrome. The delicate paintings seem to be made by the same Uemura Shōen, although this is not explicitly stated. There are two grayscale reproductions of ancient paintings, one in the prologue, a part of the Makura no sōshi emaki (Sei Shōnagon, 2021, p. 19), and the other, opposite the author’s bionote, depicting her. The other pictures (29 in total) are included in the annexes. They are black and white drawings by Juan Hernaz, intended to aid a better understanding of the explanations. To sum up, all the visual paratexts included in the inside of the book are relevant, and show a total harmony with its content. Thus, they are not considered to be exoticising, but rather familiarising.

It is interesting to note that most of the cover images were done by male artists, while women were responsible for the images in the newer editions (Satori 2021 and Adriana Hidalgo 2022).

6.2. Textual paratexts

In the prologue of Borges and Kodama’s edition, written by the latter, she compares the book with the Libro de Buen Amor from Spanish literature and with Homer’s catalogues. This approach conveys a point of view based on the TT culture. Besides, Borges’ name appears ten times, while the name of the author, Sei Shōnagon, appears nine times. This paratext, we conclude, is clearly focused on Borges, with several paragraphs that describe the writer’s interest in and appreciation of Japanese literature. This therefore leads us to consider this translation as a domestication.

In Roca-Ferrer’s textual paratexts we can see some familiarisation, but also some exoticising elements. Firstly, there are two mentions of the Kama-Sutra 7. Although he does not establish a direct similarity between the two texts, his reasons for mentioning it are also unclear. Since the only common ground between the two are the fact they are both in the Oriental category, we consider these allusions to be an exoticising element. Another example of exoticisation is the Japan vs West dichotomy, found four times in the prologue 8.

The back cover of Sato’s 2001 translation includes a short introduction of Japanese literature, which highlights the prominent role that women played in cultural life during the Heian period, and in particular, the role of Sei Shōnagon as a pioneer of a Japanese literary genre called zuihitsu.

In the translator’s preface, Sato briefly outlines the historical and geographic context of the ST, which was a golden era for classical Japanese literature, and presents Heian-kyo, with its urban system and aesthetic ideals borrowed from China’s Tang dynasty. She states that by the year 996, the phonetic writing system hiragana had been developed, and consequently, “the center of gravity in literature moved from men to women” (Sei Shōnagon, 2014, p. 11). It is thanks to this development that women came to be the protagonists of the literary world at the time. The translator, therefore, makes a short reference to Sei Shōnagon’s biography and comments on her pride and high intellectual capacity and culture. She is portrayed as a witty woman who enjoyed showing off her intellectual superiority over her peers. Sato comments on the different interpretations of the title “Makura no sōshi”. However, she does not make comments on the translation process and strategies, although she does stress Shōnagon’s outstanding intellectual capacity, highlighting her image as an empowered woman of her time. She draws reflections on the literary context of the ST, while presenting a familiarising image of the Other, trying to narrow the distance between the ST and the target community, but at the same time acknowledging the differences with the remote culture of the ST.

Álvarez Crespo’s prologue, as well as the annexes and notes, can be seen as a familiarisation, i.e., they seem to serve the purpose of bringing the ST culture closer to the reader, often including Japanese words and an explanation of their meaning. One case of domestication was found 9, as well as some examples of parts that lacked the explanations needed for a full understanding, which can be considered as exoticisation, since the referent remains obscure to the reader. For example, there is an image that illustrates Japanese time-telling (Sei Shōnagon, 2021, p. 346) which contains many kanji (Japanese characters) without a translation. This may not be clearly understood and simply appear exotic to the general reader.

Another remarkable point is the fact that in the footnotes and annexes, the translator uses definitions taken from the first Japanese-Spanish dictionary published in 1620 (Sei Shōnagon, 2021, p. 321), marking it with the initials VdJ (“Vocabulario de Japón”). This is certainly an interesting document from a historical standpoint, but when we look at the definitions, their usefulness becomes questionable, leading us to consider whether this is the most suitable source to use today. For example, in Annex 1, the following explanation is offered about the Mandarin duck: “Oshi, oshidori (鴛鴦). Aix galericulata. VdJ: ‘Ave del mar como pato’ [Seabird resembling a duck]” (p. 323). As can be seen, VdJ does not offer a lot of information, only indicating it is a type of duck, which is also understood from the headword. It even contains a mistake, stating that it is a seabird, when actually it lives on rivers and lakes. In addition, this definition omits information that enables a fuller understanding of the deep significance of this bird, which was held in high esteem partly thanks to the male’s beautiful colouring, but, most importantly, due to the fact that it chooses a partner for life, and is therefore a symbol of conjugal happiness. To our mind, a definition that is not helpful and even contains a mistake, but which comes from a prestigious ancient source, is an example of exoticism, where the “distant flavour” prevails over accurate information. Most of the definitions from VdJ seem to be unhelpful and redundant, since the information is contained in the headword or explanation 10. To sum up, we would like to highlight that Álvarez Crespo’s textual paratexts are, as a general rule, familiarising, although there are some elements of exoticisation.

6.3. Notes

As explained in the theoretical and methodological framework, we did not analyse all the notes but rather a selection, with the aim of undertaking a qualitative approach. The total number of notes in the four translations amounts to 1,620, which is too many for the magnitude of our study. To observe a representative sampling, we chose one note from each category as per the classification by Peña and Hernández (1994) from each of the four translations, and we added five more ethnographic notes, as we saw that this category tended to carry a heavier cultural load. We analysed a total of 45 notes, 10-13 from each translation (taking into account that some of the translations lack notes from one of the categories).

Since a detailed explanation and listing of all the notes would be too long, in this section, we have summarised the results found. In the appendix, the complete text of the selected notes can be found, with their English translation and our detailed explanation on each of them in relation to the representation of the Other. All the translations include notes that can be considered examples of domestication, familiarisation and exoticisation. We also found one case that can be considered “emic” 11.

Firstly, we will present an example of each kind of presentation of the Other for a better understanding of the criteria followed. There is a passage where Narimasa talks about a kind of special jacket for page girls, and the court ladies laugh at him. In Borges and Kodama’s edition, there is a note for the word “atuendo” [attire] (Sei Shōnagon, 2004, p. 23) which explains: “He uses the word ‘attire’ because he does not know the name of the garment” (p. 168) 12. While other translations include the Japanese word for a specific item of clothing, be it in the text or in the note, this translation uses a generalisation avoiding the original term and its nuances, which we consider to be a domestication. The approach is similar in Sato’s translation, where the word “accesorios” [accessories] (Sei Shōnagon, 2014, p. 29) is used, and there is no note. The version by Roca-Ferrer uses the expression “xancletes xineses” [Chinese sandals] (Sei Shōnagon, 2007, p. 47) in the text, and the note explains in detail the translator’s choice in the context: “Narimasa gets the wrong word. In search of an equivalent, we have him say sandals instead of jackets, although this is an approximate solution. These jackets were called kara-ginu and were worn over all other clothes”. We consider his approach as familiarising, because he informs the reader about the source culture, enabling them to fully understand the text. On the other hand, the translation by Álvarez Crespo offers the Japanese word “akome” 13 (Sei Shōnagon, 2021, p. 37), and the footnote explains its meaning: “Akome (衵). Jacket, outer garment worn by the page girls”. While this concise note offers all the needed information to grasp the word’s meaning, it lacks the context needed to understand why the court ladies laugh at him. Hence, we consider it exoticising, because the Other is presented from the standpoint of the ST, but the explanation is not enough for a reader to fully understand the situation and a certain amount of mystery remains.

For the “emic” category, we found only one example, in Roca-Ferrer’s translation. The text contains the Japanese word “ushi-hasame” (Sei Shōnagon, 2007, p. 194) without a translation, and a footnote explains that “The translators cannot reach an agreement as to what this may be” 14. Although we generally consider Japanese terms without a clear explanation as exoticising, this is an exception because the translator himself recognises he does not know the meaning of the word, hence he has no other choice but to leave it untranslated and impossible to understand.

Next, we will explain the number of times each approach is found in the selected corpus (Table 2). As explained in the Theoretical Framework, the classification of the strategies for presenting the Other in the notes was established combining the approaches by Venuti (1998) and Carbonell (2004). Even though this cannot be considered a quantitative study due to the limited sample, we considered a table useful to summarise the findings and present an overall view.

Table 2. Strategies for presenting the Other in the selected notes.

| Version* | Domestication | Familiarisation | Exoticisation | Emic | Total |

| Borges & Kodama (2004) | 3 | 4 | 3 | 10 | |

| Roca-Ferrer (2007) | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 12 |

| Sato (2009) | 2 | 7 | 1 | 10 | |

| Álvarez Crespo (2021) | 1 | 8 | 4 | 13 | |

| Total | 45 |

* We indicate here the year of first publication in Spain.

As we can see in Table 2, all the editions show a prevalence of familiarisation over other approaches, hence we can say that all the translators have a strong desire to bring the Other closer to the reader. However, their presentation of the cultural referents is not uniform, and different approaches are found across the translations.

If we look at the familiarising notes (Table 2), we can see that the number increases alongside the degree of expertise of the translator in the Japanese language and culture (the first translators in the table have less knowledge of this field, and the last translator in the list is the most experienced). In short, Borges’ knowledge came from reading translations of Japanese literature, while Roca-Ferrer himself translated other Heian period literature (although not from Japanese). Sato supposedly used a Japanese source alongside an English one, although she recognises her Japanese level is not high enough to translate from this language, as explained previously in the section about the target texts. Álvarez Crespo translated directly from Japanese and has the highest number of familiarising notes.

Looking at the domesticating notes, an inverse relationship can be observed between these and the level of expertise, Borges and Kodama’s edition being the one that includes most, while Álvarez Crespo has only one.

Surprisingly, there is not the same correlation for the exoticising notes, which are similar in number in all editions except for that of Sato, where there is only one. We can link this to her ideology 15, suggesting that exoticisation does not relate to the level of knowledge, but rather to ideology.

If we look at each version, we can see that in Borges and Kodama there is almost the same number of domesticating, familiarising and exoticising notes. In Roca-Ferrer and Álvarez Crespo, there are twice as many familiarising notes as exoticising ones, but the difference is that Roca-Ferrer includes two domesticating notes while Álvarez Crespo only one. In Sato’s version familiarisation prevails, with only two cases of domestication and one of exoticisation.

The findings show a harmony with the trends seen in the other paratexts, although a more in-depth study of the notes would be interesting, as well as, ideally, a larger selection of notes, or all of them.

7. Conclusions

This study confirmed our first hypothesis, that in accordance with the ideas of the Retranslation Hypothesis, a chronological evolution in the presentation of the Other can be seen, especially in the covers (visual or iconographic paratexts). The oldest editions, those translated by Borges and Kodama (2004, 2005, 2015), Roca-Ferrer (2007), and the first edition of Sato’s translation in Argentina (2001), show a higher degree of exoticisation. The covers depict women from different periods, from centuries after the book’s creation. This disharmony reminds us of the concept of atemporality, where the Other is placed out of historical development. The use of sensuality in some of them is also reminiscent of Orientalism. On the other hand, the 2009 edition of Sato’s translation shows a scene from the Heian period, and the last edition (2022) offers modern illustrations that represent elements from that period. Thus, the newer covers show a harmony with the content, and the latter a special inclination towards familiarisation, showing an obvious intention to approach the reality of the book to today’s readers. This is also the case of the most recent translation, by Álvarez Crespo, which also depicts a lady from the Heian period.

Borges and Kodama’s textual paratexts are domesticating, particularly focused on Borges’ interest in and opinions of Japanese literature. Roca-Ferrer’s prologue is partly domesticating, due to his subjective opinions, and partly exoticising due to the recurrent references to the East-West dichotomy and the mention of the Kama-Sutra. In Borges and Kodama, the notes are almost equally familiarising, domesticating and exoticising, and in Roca-Ferrer, familiarisation prevails but half of the notes show other approaches. The most recent translation, by Álvarez Crespo, however, mainly shows a familiarising approach, with only one relevant exoticising element (references to an ancient dictionary). The only exception to this chronological evolution are Sato’s textual paratexts, since her prologue and notes, which are the same in all the editions, are mostly familiarising, even in the first 2001 edition in Argentina, which predates Borges and Kodama’s edition in Spain. This can be explained in relation with our second hypothesis, which stated that a higher degree in expertise would lead to a familiarising approach. Borges and Kodama and Roca-Ferrer were not specialists in Japanese language and culture, and their paratexts show more domesticating and exoticising elements (Roca-Ferrer seems to have some knowledge on the Heian period and his notes have a higher proportion of familiarisation compared to the former). On the other hand, Sato seems to have a deep interest in the Japanese culture and some personal links with its people, and Álvarez Crespo knows the language and is living and working in Japan. This confirms that a higher level of knowledge of the culture is related to an approach based on familiarisation and greater harmony with the content of the book, while a lack of first-hand knowledge is linked with domestication and exoticisation.

As for translator visibility, we saw a difference between the paratexts prepared by the publisher and those written by the translators themselves. Some publishers give visibility to the translator, including their name on the covers and some information about them, while others do not. We did not observe a correlation between this and variables such as time or the image of the Other. Paradoxically, the least visible translator is Álvarez Crespo, who is the translator with the greatest level of expertise of the studied corpus. The visibility of the translators in the paratexts created by themselves presents a different case. There we did observe a correlation between greater visibility (Borges and Roca-Ferrer), comparatively shallower knowledge of the source culture, and a presentation of the Other that swings between domestication and exoticisation. We conclude that as a result of their limited knowledge of the culture, they sometimes tend towards trying to erase differences and fall into stereotypes, although their use of familiarising strategies does also reveal their intention to bring the Other closer to the reader. Translators with a deeper knowledge and more familiarizing approach had lower visibility. This could be interpreted as a sign of the translator’s intention to emphasise the ST culture.

These findings are somewhat contradictory to the theories put forward by Venuti (1995, 1998), who links a greater visibility of the translator and the ST with a more authentic approach. Our findings align more closely with Carbonell’s theory for cultures “that fall within the ‘exotic’ category” (2003, p. 153).

We are aware that our findings may not apply to all translations and translators, but our aim is to contribute to a better understanding of the mechanisms for creating cultural images that are inherent in the translation activity.

The analysis of notes, albeit a narrow selection, reflects a close alignment with the translator’s other paratexts. Furthermore, the comparison of notes of the same passages in different translations has shed light on several discrepancies in the content of the translated texts, as can be seen in the Appendix. A deeper study of the notes would therefore be an interesting topic for future study.

8. References

Cadera, S. & Walsh, A. S. (Eds.) (2017). Literary Retranslation in Context. Peter Lang.

Carbonell i Cortés, O. (2003). Semiotic alteration in translation: Othering, stereotyping and hybridization in contemporary translations from Arabic into Spanish and Catalan. Linguistica antverpiensia, 2, 145-159.

Carbonell i Cortés, O. (2004). Vislumbres de la otredad. Hacia un marco general de la construcción semiótica del Otro en traducción. Vasos Comunicantes, 28, 59-71.

Chesterman, A. (2011). The Significance of Hypotheses. TTR, 24(2), 65-86.

Deane-Cox, S. (2014). Retranslation: Translation, Literature and Reinterpretation. Bloomsbury.

Friera, S. (2005, July 18). La traducción es un acto de resistencia periférica. Página 12. http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/cultura/7-53842-2005-07-18.html

Gambier, Y. (1994). La retraduction, retour et détour. Méta/Translation Journal, 39(3), 413-417.

Genette, G. (1997). Paratexts; Thresholds of interpretation (J. E. Lewin, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

Henitiuk, V. (2012). Worlding Sei Shōnagon: The Pillow Book in Translation. University of Ottawa Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vkcfc.

Kato, S & Sanderson, D. (1997). A History of Japanese Literature. Routledge.

Kawabata, Y. (2007). La casa de les belles adormides (A. Mas-Griera; S. Ruiz Morilla, Trans.). Viena.

Kawabata, Y. (2013). La casa de las bellas durmientes (M. C., Trans.). Emecé.

Mishima, Y. (1993). Música (S. Isisu, Trans.). Seix Barral.

Mishima, Y. (2008). La remor de les onades (J. Pijoan & K. Tazawa, Trans.). Ara Llibres.

Monti, E. & Schneider, p. (Eds.) (2011). Autour de la retraduction. Perspectives littéraires et européennes. Orizons.

Murasaki Shikibu (2005). La novela de Genji: Esplendor (X. Roca-Ferrer, Trans.). Destino.

Murasaki Shikibu (2006). La novel·la de Genji: el príncep resplendent (X. Roca-Ferrer, Trans.). Destino.

Murasaki, Shikibu, Izumi Shikibu & Dama Sarashina. (2007). Diarios de damas de la corte Heian: Izumi Shikibu, Murasaki Shikibu, Diario de Sarashina (X. Roca-Ferrer, Trans.). Destino.

Peña, S. & Hernández, M. J. (1994). Traductología. Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga.

Reiss, K. & Vermeer, H. (1996). Fundamentos para una teoría funcional de la Traducción (C. Martín de León & S. García Reina, Trans.). Akal.

Revon, M. (Ed.). (2000). Antología de la literatura japonesa: desde los orígenes hasta el siglo XX (M. Comes, Trans.). Círculo de Lectores.

Rodríguez Navarro, M. T., & Beeby, A. (2010). Self-censorship and censorship in Nitobe Inazo, Bushido: The soul of Japan, and four translations of the work. TTR, 23(2), 53-88. https://doi.org/10.7202/1009160ar

Rosen, S. L. (2000). Japan as Other: Orientalism and Cultural Conflict. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 2(2), 1-05. https://doi.org/10.36923/jicc.v2i2.378

Rubio, C. (2007). Claves y textos de la literatura japonesa: Una introducción. Cátedra.

Rubio, C. (2021). Mil años de literatura femenina en Japón. Satori.

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Penguin.

Sato, A. (2020). Literatura Cortesana del período Heian. Sitio oficial de Amalia Sato. https://amaliasato.com/literatura-cortesana-del-periodo-heian/

Satori. (n.d.). Autores Sakura. Satori. https://satoriediciones.com/escritor/autores-sakura/

Sei Shōnagon. (1969). El Libro de Almohada (Makura no sōshi) [K. Sakai, Trans.]. Estudios Orientales, 4(1), 49-69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40313860

Sei Shōnagon. (1971). The Pillow book of Sei Shōnagon (I. Morris, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Sei Shōnagon. (2001). El libro de la almohada (A. Sato, Trans.). Adriana Hidalgo.

Sei Shōnagon. (2002). El libro de la almohada de la dama Sei Shōnagon (I. A. Pinto Román & O. Gavidia Cannon, Trans.). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Sei Shōnagon. (2004). El libro de la almohada (J. L. Borges & M. Kodama, Trans.). Alianza Editorial.

Sei Shōnagon. (2006). El libro de la almohada (J. Freudenthal, Trans.). Supplement to La mariposa mundial, 15.

Sei Shōnagon. (2007). Quadern de capçalera (X. Roca-Ferrer, Trans.). La Magrana.

Sei Shōnagon. (2014). El libro de la almohada (A. Sato, Trans.) (2nd ed. in Spain). Adriana Hidalgo.

Sei Shōnagon. (2015). El libro de la almohada (J. L. Borges & M. Kodama, Trans.) (2nd ed.). Alianza Editorial.

Sei Shōnagon. (2021). El libro de la almohada (J. C. Álvarez Crespo, Trans.). Satori.

Sei Shōnagon. (2022). El libro de la almohada (A. Sato, Trans.). A. Hache.

Serra-Vilella, A. 2022. No podía ser más nipón: imagen del otro en las traducciones de Confesiones de una máscara de Mishima. TRANS. Revista de Traductología, 26, 141-159. https://doi.org/10.24310/TRANS.2022.v26i1.14068

Shirane, H. (2012). Traditional Japanese Literature. An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600. Columbia University Press

Shirane, H., Suzuki, T., & Lurie, D. (2016). The Cambridge history of Japanese literature. Cambridge University Press.

Sologuren, J. (Sel.) (1993). El rumor del origen: antología general de la literatura japonesa. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Tanizaki, J. (2004). Hay quien prefiere las ortigas (M. L. Borràs, Trans.). Seix Barral.

Torres-Simón, E. (2013). Translation and Post-Bellum Image Building: Korean translation into the US after the Korean War [Doctoral dissertation, Rovira i Virgili University]. http://hdl.handle.net/10803/145864

Venuti, L. (1995). The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. Routledge.

Venuti, L. (1998). The Scandals of Translation: Towards an ethics of difference. Routledge.

Vives, B. (2006). Japón en situación de lectura: entrevista a Amalia Sato. Sitio oficial de Amalia Sato. https://amaliasato.com/japon-en-situacion-de-lectura-entrevista-a-amalia-sato/

Yuste Frías, J. (2011). Leer e interpretar la imagen para traducir. Trabalhos em Lingüística Aplicada, 50(2), 257-280.

Appendix: Corpus of notes

This appedix includes, firstly, one note of each type, following Peña and Hernández’s classification (1994, pp. 37-38). It then includes five more ethnographic notes. The first column in the table indicates the version, with abbreviations of the translators’ surnames (B&K for Borges and Kodama, R-F. for Roca-Ferrer and A. C. for Álvarez Crespo), with the exception of Sato. The complete references to these editions can be found in the reference list. The next column includes the referent in the text and the page. Most of the editions use footnotes, so the page number is omitted after the note, except in the case of the translation by Borges and Kodama, which uses endnotes, and some notes by Álvarez Crespo that are included in the appendixes. Following the referents and the notes, the English translation is offered by the authors of this paper. For each note we indicate in the last column whether they approach the representation of the Other with strategies of domestication, familiarisation or exoticisation (or emic, which is only in one case). In some cases we considered that one note combines two approaches. It must be noted that our criteria are based upon the translation-note dyad, and further comments about each case can be found in the last row of the tables.

A. Setting note

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | “el último cuarto de la hora del Buey” [the last quarter of the Ox hour] (p. 153) | “Las tres y media de la madrugada” [half past three a.m.] (p. 175) | Familiarisation |

| R-F. | “el darrer quart de l’hora del Bou” [the last quarter of the Ox hour] (p. 277) | “Dos quarts de quatre de la matinada” [half past three a.m.] | Familiarisation |

| Sato | “El Buey, cuarta parte” [The Ox, fourth part] (p. 301) | There is no note. | Exoticisation |

| A. C. | “el cuarto cuarto [sic] de la hora del buey” [the fourth quarter of the Ox hour] (p. 308) | “Sobre las dos y media de la madrugada” [about half past two a.m.] | Familiarisation |

| Comments:

The choice by B&K, R-F. and A. C. is considered familiarising because they bring the old time referent closer to the reader. We consider Sato’s choice not to include an explanation as exoticising, because this will give the reader an imprecise and mysterious nuance. Apart from this, a slight difference is seen in the information conveyed in the notes by B&K and R-F. on the one hand and by A. C. on the other. It seems that the correct one is the latter, and that the other two may be based on Morris’ translation into English, which conveys the same information. |

|||

B. Ethnographic note

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | “la gente arranca la hierba joven que ha nacido bajo la nieve” [people pull up the fresh grass that has sprouted under the snow] (p.14) | There is no note. | Exoticisation |

| R-F. | “els ‘brots tendres’” [the fresh sprouts] (p.40) | “Aquests ‘brots tendres’ (wakana) passaven per tenir especials virtuts medicinals” [These sprouts were thought to have special medicinal properties]. | Familiarisation |

| Sato | “la gente arranca las primeras hierbas que han germinado bajo la nieve” [People pull up the first shoots of grass that have sprouted under the snow] (p. 20) | “[…] siete hierbas […] ingeridas con el fin de proteger la salud durante el año […]” [Seven herbs consumed to preserve health during the year]. | Familiarisation |

| A. C. | “las verduras” [the vegetables] (p. 30) | “Ese día, y también en la actualidad, se tomaban unas gachas con siete tipos de verduras (nanakusa gayu) para evitar enfermedades y asentar el cuerpo tras días de excesos, según una costumbre procedente de China. Las siete hierbas que se utilizan son las siguientes: nazuna (penpengusa), la bolsa de pastor; seri, el enante o perejil; hakobera (hakobe), la pamplina o álsine; gogyō (hahakogusa), Gnaphalium affine; suzushiro (daikon), el nabo japonés; hotokenoza (tabirako), Lapsana apogonoides, Maxim; y suzuna (kabu), el rábano.” [Back then, and still today, they ate a porridge made from seven types of vegetables (nanakusa gayu) in order to avoid illness and let the body rest after several days of excesses, following a tradition that came from China. The seven herbs are: nazuna (penpengusa), shepherd’s purse; seri, Japanese parsley; hakobera (hakobe), chickweed; gogyō (hahakogusa), cudweed; Gnaphalium affine; suzushiro (daikon), radish; hotokenoza (tabirako), Lapsana apogonoides, Maxim, nipplewort; and suzuna (kabu), turnip.] | Domestication/ Familiarisation |

| Comments: In this ethnographic note, we consider B&K’s approach to be exoticising because they do not offer any information, leaving the reader with just an exotic flavor, unable to really understand the referent. R-F. and Sato’s examples are familiarising, because they offer a brief explanation. A. C.’s detailed explanation is a good way to bring Japanese tradition closer to the reader, and can therefore be considered familiarizing. Nevertheless, this translation is also domesticating, because someone who does not read the note will have a partial idea of what is described, and perhaps misleading, since most translations render this referent as “seven herbs”, not “vegetables”, and even this translator uses the term “herbs” later in his explanation. | |||

C. Encyclopedic note

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | “hototoguisu” (p.17) | “Hototoguisu: onomatopeya de su nombre. Es el cuclillo.” [Hototogisu: onomatopeya of his name. It is the cuckoo.] (p. 167) | Domestication |

| R-F. | “cucut” [cuckoo] (p. 43) | “El hototogisu. Se sol traduir per ‘cucut’, però no és exactament el mateix ocell” [The hototogisu. It is usually translated as ‘cuckoo’, but it is not exactly the same bird.] | Familiarisation |

| Sato | “hototogisu” (p. 24) | “(Ornit.) Cuculus poliocephalus, usualmente traducido como cuclillo” (p. 24) [Cuculus poliocephalus, usually translated as cuckoo.] | Familiarisation |

| A. C. | “cuco chico” [lesser cuckoo] (p. 33) | There is not a footpage, but an explanation is included in the annex: “Cuco chico. Hototogisu (郭公、杜鵑). Cuculus poliocephalus. Su gorjeo se asocia con el principio del verano, y con el amor” [Lesser cukcoo. Hototogisu (郭公、杜鵑). Cuculus poliocephalus. Its chirping is associated to the beginning of the summer, and love] (p. 324) | Familiarisation |

| Comments: B&K’s approach is domesticating because of their atypical romanization, which does not follow the standards, by adding a “u” between the “gi” syllable to help Spanish readers pronounce the word correctly, and especially by their explanation, that offers a name of a bird of the same ornithological family as if it were the same bird. The other translators offer a familiarising approach by using a translation, but also explaining that it is not exactly the same bird. | |||

D. Institutional note

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | Fragment not included | - | - |

| R-F. | “servir la gran vestal de Kamo, encara que comporti fer grans pecats” [to serve the great vestal of Kamo, even if it entails great sins] (p. 238) | “Per una devota budista, servir en un santuari xintoista comportava pecar continuament contra la seva autèntica religió [...]. Paradoxes de la vida religiosa japonesa!” [For a Buddhist devotee, to serve a Shinto shrine meant continually sinning against their true religion [...]. Paradoxes of Japanese religious life!] | Exoticisation |

| Sato | Fragment not included | - | - |

| A. C. | “la corte de la alta sacerdotisa de Kamo, aunque supone una ofensa para el budismo” [the court of the high priestess of Kamo, even though it is an offence to Buddhism] (p. 317) | “La alta sacerdotisa de Kamo tenía prohibido participar en cualquier asunto relacionado con el budismo, evidenciando la separación de esta religión con la fe sintoísta” [The high priestess of Kamo was banned from participating in any matter related to Buddhism, demonstrating the division between this religion and the Shinto faith.] | Familiarisation |

| Comments: Institutional notes are scarce. We found an example about religious institutions in R-F. and A. C., but the same passage is not included in the translations by B&K and Sato, which are not based on the full ST. In the case of R-F., we consider it to be an exoticisation due to the last sentence of the note, which is a subjective comment of the translator, which adds no relevant information and instead distances the reader from the Other, presenting the latter as “paradoxical”, in other words, difficult for us to understand. The version by A. C. includes only objective information, thus it is considered to be familiarising. | |||

E. Metalinguistic note

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | “atuendo” [attire] (p.23) | “Usa la palabra atuendo porque no sabe el nombre de la prenda” [He uses the word “attire” because he does not know the name of the garment] (p.168) | Domestication |

| R-F. | xancletes xineses [Chinese sandals] (p. 47) | “Narimasa erra la paraula correcta. Cercant un equivalent, li fem dir xancletes per jaquetes, però és una solució aproximada. Aquestes jaquetes es deien kara-ginu i es portaven a sobre de tot.” [Narimasa gets the wrong word. In search of an equivalent, we have him say sandals instead of jackets, although this is an approximate solution. These jackets were called kara-ginu and were worn over all other clothes] | Familiarisation |

| Sato | “accesorios” [accessories] (p. 29) | There is no note. | Domestication |

| A. C. | “akome” (p. 37) | “Akome (衵). Chaqueta, prenda exterior que llevaban las muchachas pajes.” [Akome (衵). Jacket, outer garment worn by the page girls] | Exoticisation |

Comments:

In this passage, Narimasa talks about a kind of special jacket worn by the page girls, and the court ladies laugh at him. In B&K’s edition, we have the generic word “atuendo” [attire] (p.23) and the note is metalinguistic, because it explains the reason why the court ladies laugh. This translation uses a generalisation, avoiding the original term and its nuances, which we consider to be domesticating. The approach is similar in Sato’s translation, where the word “accesorios” [accessories] is used, without a note. The version by R-F. uses the word “xancletes xineses” [Chinese sandals] (p. 47) in the text, and the note explains in detail the choice of the translator regarding the context of the story. We consider his approach as familiarising, because he informs readers regarding the source culture to aid their full understanding of the text. On the other hand, the translation by A. C. offers the Japanese word “akome”, and the footnote explains its meaning, but it lacks the context needed to understand why the court ladies laugh at him. Hence, we consider it exoticising, because, although the Other is presented from its own point of view, the explanation is not sufficient to fully understand the situation, which remains a mystery.

|

|||

F. Intertextual note

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | Yû Ting-kuo (p. 21) | “Narimasa confunde el nombre de Ting-kuo, el hijo, con el padre, Yû Kung. El padre prevé para su hijo un porvenir brillante y manda construir un gran portón en la casa, a través del cual pasaría la gran escolta de su hijo” [Narimasa mixes up the name of Ting-kuo, the son, with that of his father, Yû Kung. The father foresees a brilliant future for his son and orders a great gate to be built in the house, through which his son’s great escort would pass] (p. 168) | Familiarisation |

| R-F | Yu Ting-Kuo (p. 46) | “Personatge proverbial dins la cultura xinesa. Va ‘viure’ en temps dels Han. En néixer, un endeví va profetitzar al seu pare que el seu fill seria molt afortunat, i el pare va fer bastir una porta grandiosa a casa seva perquè hi pogués passar la immensa fortuna que, segons els astres, guanyaria el seu fill. Ve a ser l’equivalent de la ‘lletera’ a la nostra taula” [Proverbial personality in the Chinese culture. He “lived” during the Han dynasty. When he was born, a fortune-teller predicted to his father that the son would be very fortunate, and the father built a huge gate for their house, to make way for the great fortune that the stars predicted he would earn. It is a kind of equivalent to our “Milkmaid and Her Pail story”] | Domestication |

| Sato | Yû Ting-kuo (p. 27) | “Debía referirse a Yû Ting-kuo. Se trata de una historia de la dinastía Han sobre un padre, que orgulloso de su hijo construye una entrada alta para los séquitos que acompañen a este” [She must have been referring to to Yû Ting-kuo. This is a story from the Han dynasty about a father who, proud of his son, builds a high gate for the entourage that would accompany him] | Familiarisation |

| A. C. | Yu Dingguo (p. 35) | “Uteikoku (宇定国) en japonés. Episodio de un clásico chino según el cual un hombre de la dinastía Han, Yu Gong, encargó que construyeran en su casa una verja excepcionalmente grande para el séquito que creía que algún día tendría su hijo, Yu Dingguo. Y así fue, ya que este consiguió grandes logros. En realidad, pues, la escritora se refiere al padre y no al hijo” [Uteikoku (宇定国) in Japanese. A chapter from a Chinese classical text which talks about a man from the Han dynasty, Yu Gong, who had an exceptionally big fence built for the entourage that he thought his son Yu Dingguo would have some day. And, indeed, his son did achieve great things. The writer, then, is actually alluding to the father, not the son.] | Familiarisation |

| Comments:

In this case, most of the notes are familiarising, offering more or less detailed information about the mentioned personality. The exception is R-F., who adds a comparison with the Western tale about the Milkmaid. A comparison with the reader’s culture could aid their understanding, but, in this case, the example is misleading. The character here presented seems to have been successful, while the Milkmaid in the tale was unsuccessful. Hence, the example leads the reader to misunderstand the referent by comparing it to a different referent of their own culture. For this reason, we considered it to be domesticating.

The diversity in the story’s interpretations should also be noted. Since this is not within the scope of this study, we shall not enter into this in greater detail, but we will briefly mention the differences. Sato suggests that the gate was built after the son’s success, while in the other three versions, it was built in anticipation of it. R-F. suggests that the son wasn’t successful, by comparing it to the Milkmaid’s tale, while A. C. states that he did indeed achieve success. |

|||

G. Textological note (in this case the notes of the different versions are from different passages, since we could not find notes from the same passages in the different versions)

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | Not found | - | - |

| R-F. | “L’ushi-hasame” (p. 194) | “Els traductors no es posen d’acord sobre què pot ser” [The translators cannot reach an agreement as to what this may be] | Emic |

| Sato | Not found | - | - |

| A. C. | “Cosas incómodas y embarazosas” [Uncomfortable and embarrassing things] (p. 166) | “Tras la enumeración de cosas embarazosas, se narra el regreso de la procesión imperial […]. Algunos expertos creen que este episodio podría haber constituido una sección independiente” [After the list of embarrassing things, the return of the imperial procession is narrated [...]. Some experts believe that this story may have been an independent section.] | - |

| Comments: In these examples, we consider that the notes do not represent the Other in one way or another, since they refer to the source text, not to cultural referents. However, the version by R-F. contains a Japanese word without a translation, and the footnote just explains that “The translators are unable to agree on what this may be” (he refers to the translators of the source texts he used, since he did not translate directly from Japanese). Although we generally consider Japanese terms without a clear explanation as exoticising, this is an exception because the translator himself recognizes he does not know the meaning of the word, hence he has no other choice but to leave it untranslated, and he explicitly states the fact that this word has been impossible for him to understand. | |||

Other notes

Ethnographic note – example 2

| Version | Referent in the text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | “festival de Tanabata” (p. 28) | “Se trata del Festival de Tanabata (Festival de la Tejedora). […] De acuerdo con una leyenda china, Tejedora y Pastor, es decir, las estrellas Vega y Altair, eran amantes […]” [Tanabata Festival (the Weaver Festival) […]. According to a Chinese legend, the Weaver and the Herdsman, that is to say the stars Vega and Altair, were lovers)] (p.168-169) | Familiarisation |

| R-F. | “els estels” [the stars] (p.52) | “[…] se celebra la festa dels estels, dedicada a Tanabata (la Teixidora) i el Bover. […] És una festa molt popular entre els japonesos” [the Festival of the Stars is celebrated, dedicated to Tanabata (the Weaver) and the Herdsman. It is a very popular festival for the Japanese.] | Familiarisation |

| Sato | “El Séptimo día del Séptimo mes [...]” [The seventh day of the Seventh month] (p.34) | There is no note. | Domestication |

| A. C. | “El séptimo día de la séptima luna” [The seventh day of the seventh moon] (p. 41) | There is no note. | Exoticisation |

| Comments: In this example, B&K and R-F.’s versions are considered to be familiarising since they explain the referent, while Sato and A. C. do not include a note. The former is considered domesticating because the reference is lost: readers unfamiliar with the Japanese culture would not know why the seventh day of the seventh month is a special day. On the other hand, A. C.’s approach is very similar, but we considered it to be exoticising due to the choice of the word “moon” to refer to the month. This is historically and linguistically accurate, since in ancient Japan the months were based on the moon cycles and the character for “month” is the same as the one for “moon”. However, without further explanation, it simply comes across as an exotic tradition. | |||

Ethnographic note – example 3

| Version | Referent in text | Note | Type of representation |

| B&K | “bolas de hierba” [balls of herbs] (p. 39) | “Para protección de enfermedades y males se colgaban bolsas de algodón o seda en el Festival del Iris y del Crisantemo” [For protection against illness and evils, they hung cotton or silken bags on the Iris and Chrysanthemum Festival] (p. 170) | Familiarisation |