:: TRANS 29. ARTÍCULOS. Págs. 85-99 ::

Updating the Training Subbranch of the Translation Studies Map

-------------------------------------

XIANGDONG LI

Xi’an International Studies University

ORCID: 0000-0002-7483-6076

-------------------------------------

The translation studies (TS) map (also known as the Holmes/Toury map) was conceptualized by Holmes (1972/1988) and visually presented to the TS community by Toury (1995). Over the past decades, the map has undergone updates to better represent the recent multidisciplinary development of TS. Despite acknowledgement of its value, for example, as an overall framework of the TS discipline, it has also been criticized for being close-ended and prescriptive. This article, based on a descriptive survey of 68 years of research in the field, aims to update the training subbranch of the TS map. The updated subbranch includes six clusters of areas, specifically, curriculum development and assessment, teacher, students, market and graduation, surrounding issues, and others. Hopefully, the enriched subbranch can provide scholars with a research context to identify research gaps and serve as a didactic tool in educating translators and novice researchers.

KEY WORDS: translation studies, Holmes/Toury map, update of the training subbranch, descriptive survey.

Actualización de la subrama de formación en el mapa de los estudios de traducción

El mapa de estudios de traducción (TS), concebido por Holmes (1972/1988) y presentado visualmente a la comunidad académica por Toury (1995), ha sido actualizado en las últimas décadas para reflejar el desarrollo multidisciplinario reciente de la disciplina. A pesar de su reconocido valor como marco general, ha recibido críticas por ser cerrado y prescriptivo. Este artículo, basado en una encuesta descriptiva de 68 años de investigación, tiene como objetivo actualizar la subrama de formación del mapa de estudios de traducción. La subrama actualizada incluye seis áreas específicas: desarrollo y evaluación curricular, profesores, estudiantes, mercado laboral y gra-

duación, temas relacionados, y otros aspectos. Se espera que esta subrama enriquecida brinde a los académicos un contexto para identificar lagunas de investigación y sirva como herramienta didáctica para la formación de traductores e investigadores noveles.

PALABRAS CLAVE: estudios de traducción, mapa Holmes/Toury, actualización de la subrama de formación, encuesta descriptiva.

-------------------------------------

recibido en octubre de 2024 - aceptado en marzo de 2025

-------------------------------------

1. INTRODUCTION

It has been more than 50 years since Holmes (1972/1988) conceived the translation studies (TS) map and almost 30 years since Toury (1995) introduced the TS map to the TS community. Over the years, the map has been updated by different scholars (Chesterman, 2009; Tarvi, 2008; Vandepitte, 2008; van Doorslaer, 2007). It is believed that the map can be used as an overall framework of the TS discipline, a conceptual model for researchers to identify research gaps, a didactic tool and orientation guide in the teaching of translators and novice researchers, and a framework to review existing research (Brighi, 2024; Hale & Napier, 2013; Munday et al., 2022; Ruokonen et al., 2018; Tarvi, 2008; Toury, 2012; Vandepitte, 2008; van Doorslaer, 2007).

In spite of acknowledgment of its usefulness, scholars also criticize its drawbacks, for example, inconsistent use of criterion in the division and subdivision of research areas, unbalanced development of directions between different areas, blurry boundaries between different divisions, simplicity of relationships, and exclusion of recently developed areas (Brighi, 2024; Chesterman, 2009; Hermans, 1991; Munday et al., 2022; Palumbo, 2009; Pym, 1998; Snell-Hornby, 1991; Vandepitte, 2008; Venuti, 2012).

According to van Doorslaer (2007), despite the pitfalls of mapping the TS discipline, a good map can still be of great value in conceptualizing TS and establishing the interrelationships between concepts. It is supposed to meet two criteria. It should be open, allowing for the displacement of outdated concepts and the addition of emerging concepts. It should be a product of a descriptive inquiry, building on empirical evidence of emerging subbranches generated from a systematic review of existing TS literature, instead of personal theorizing or conceptualizations which can be intuitive, inconsistent, and unreliable. The multidisciplinary developments of TS as a discipline in recent years represent a due update of Holmes’ map (Munday & Vasserman, 2022).

This article aims to update the TS map. Instead of redeveloping the whole map, it aims at updating the training subbranch of the TS map based on the results of a descriptive survey of 68 years of research in the field. In the first section, it reviews the origin, branches, criticism, functions, and recent updates of the TS map. Then the second section elaborates on the evolution and problems of the training subbranch in the map. The third section reports on the background information of a descriptive survey of the literature, based on which the current version of the training subbranch is updated. The last section presents an updated training subbranch and provides examples for each research area.

2. THE TS MAP: ORIGIN, BRANCHES, CRITICISM, FUNCTIONS, AND RECENT UPDATES

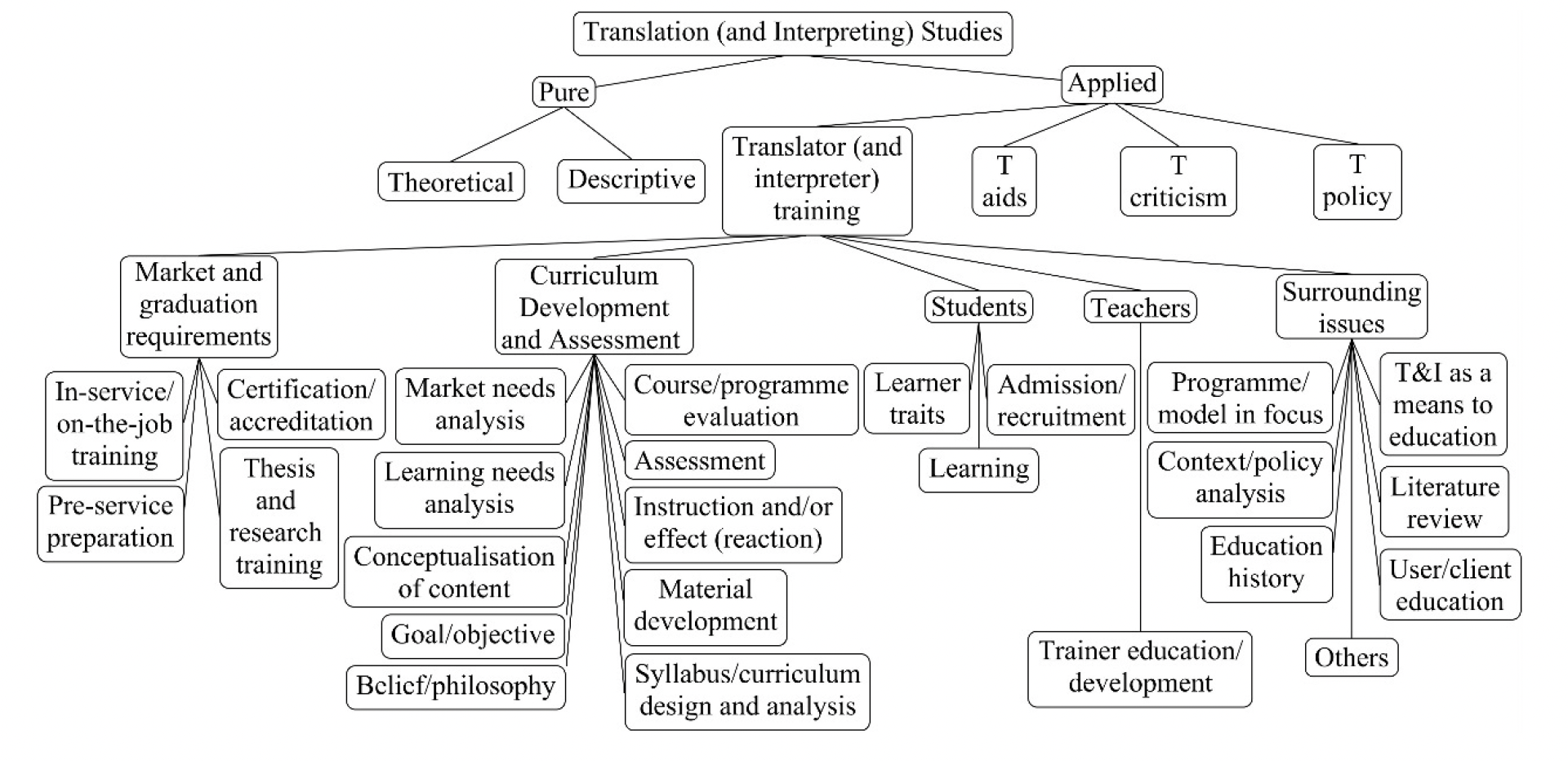

In 1972, James S. Holmes (1924-1986) presented a paper titled “the name and nature of Translation Studies” at the Third International Congress of Applied Linguistics in Copenhagen. In 1988, two years after he passed away, an expanded version of the paper was published in a collection of his works (Holmes, 1972/1988). The ideas presented in this paper are believed as the prototype of the Translation Studies (TS) map. Holmes (1988) proposed a framework for the TS discipline in which the research directions and their purposes were described. As the founding statement of TS as a discipline (Gentzler 2001), it paved the way for the future establishment of TS as an independent discipline when it was still in its infancy as a branch of linguistics. Seven years later, Toury (1995) presented the framework of Holmes (1972/1988) in the form of a tree diagram which was later widely known as the map of TS (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The TS map (Holmes, 1988; Toury, 1995; Chesterman, 2009)

According to the map, TS falls into two broad areas, pure TS and applied TS. Pure TS can further be divided into two directions, theoretical TS and descriptive TS. Theoretical TS aims at developing theories to explain or predict translation phenomena. It deals with either universal theories applying to translation as a whole (general) or theories aiming to address issues concerning the translation of a specific medium, language/culture, linguistic level, text type, or difficulty or translation activities of a certain period (partial). Descriptive TS, by contrast, aims to describe translation phenomena. It focuses on analyses of existing translated texts (product-oriented), cognitive processes of translation (process-oriented), or the function of translations in the target contexts (function-oriented). Different from pure TS, applied TS is divided into four directions, translator training (teaching methods, testing techniques, or curriculum design), translation aids (use of translation instruments), translation criticism (evaluation of translations), and translation policy (the role and place of translation and translators in society).

The current literature indicates that the map is of use in more than one aspect. It provides an overall framework of the TS discipline, informing scholars of what TS covers (Brighi, 2024; Munday et al., 2022; Toury, 2012; Vandepitte, 2008). Moreover, it serves as a conceptual model for researchers to identify research gaps and position their research (Brighi, 2024; Hale & Napier, 2013; Ruokonen et al., 2018). Also, it can be used as a didactic tool and orientation guide in the teaching of translators and novice researchers at the university level (Brighi, 2024; Tarvi, 2008; van Doorslaer, 2007). Last but not least, the map has been used as a framework to review existing research and identify trends and features of research on a given topic in the field, as is the case of Lee (2015), Nouraey and Karimnia (2015), O’Brien (2022), and Zhao and Ma (2019).

Though the impact and significance of the map are widely acknowledged, it has received criticism. The first criticism relates to the inconsistent use of criteria in the division and subdivision of research areas, for example, the use of purpose as the criterion to distinguish between applied and pure TS, as opposed to the use of method as the criterion to subdivide pure TS into different sub-areas (Vandepitte, 2008). The second one concerns the unbalanced development of directions between theoretical TS and descriptive TS and between pure TS and applied TS (Palumbo, 2009; Munday et al., 2022). Another criticism is the blurry boundaries between different divisions and the simplicity of relationships; for example, a theory may fit into more than one restricted category in the theoretical branch, and descriptive and applied TS can be closely related to each other (Brighi, 2024; Hermans, 1991; Munday et al., 2022; Pym, 1998). The most pointed weakness of the map is that it is outdated. It omits several subfields, such as sociological approaches, ethics, interpreting studies, historical studies, and interdisciplinary perspectives, and therefore fails to provide a coherent overview of the field (Chesterman, 2009; Palumbo, 2009; Pym, 1998; Snell-Hornby, 1991; Vandepitte, 2008; Venuti, 2012).

Since Toury’s (1995) presentation of the TS map conceived by Holmes (1972/1988), efforts have been made to revise or complement it. In 2007, van Doorslaer (2007), based on the Translation Studies Bibliography (John Benjamins), proposed an open-ended tree diagram covering four subareas, approaches, theories, research methods, and applied TS. Tarvi (2008) developed a map-matrix to describe TS for pedagogical purposes. Vandepitte (2008), aiming to generate a coherent overview of the field of TS, proposed a TS thesaurus. Chesterman (2009) added three branches (cultural, cognitive, and sociological) to Holmes’ map which he thinks emphasizes too much of the textual dimensions. Since the current article focuses on the translator training subbranch in the applied TS branch, the next section will elaborate on how research themes on translator training have evolved over the years.

3. THE TRAINING SUBBRANCH IN THE TS MAP: EVOLUTION AND PROBLEMS

Training, together with translation aids, translation criticism, and translation policy, belongs to the subbranches of applied TS in the TS map. The translator training subbranch consisted of three directions, teaching methods, testing techniques, and curriculum design (Holmes, 1972/1988; Munday, 2001; Toury, 1995). This version was then updated by Tao (2005) to include a fourth direction of textbook compilation, based on her review of the development of translation textbooks in China. Van Doorslaer (2007) proposed a different version which includes four directions, namely, competence, curriculum, teaching, and exercises. After rounds of updates, this subbranch was expanded to include four areas, namely, teaching methods (exercises), testing techniques, textbook compilation, and curriculum design (van Doorslaer, 2007; Holmes, 1972/1988; Munday, 2001; Tao, 2005; Toury, 1995).

The current version of the training subbranch is problematic in three aspects. The first limitation is the blurry division and the simplicity of relationship. The four areas, though presented as parallel themes, are not comparable to one another because curriculum design is a broad concept covering teaching methods, testing techniques, and textbook compilation. From a curriculum development and assessment (CDA) perspective, a framework in educational studies, curriculum design includes market needs analysis, learning needs analysis, conceptualization of teaching content, objective and goal, philosophy/belief, syllabus/curriculum design and analysis, material development, instructional strategies, assessment, and course/program evaluation. Such a limitation is related to the fact that no definitions have been provided to describe the scope of each area. Consequently, users of the map may find it challenging to interpret each research area.

The second problem lies in its way of generation. It is a product of a prescriptive approach. A descriptive approach is concerned with describing the world as it is through objective observation and analysis of phenomena (facts-driven); in contrast, a prescriptive approach involves making judgements of the world as it should be by proposing norms or theoretical frameworks (Bryman, 2012; Kuhn, 1962). The TS map is a proposed theoretical framework based on personal conceptualizations of the TS areas, instead of a description of what has been researched in TS. Therefore, it results from prescriptive conceptualization. When the map was initially proposed over fifty years ago, adopting a descriptive approach was not feasible, as TS was still in its infancy as a discipline, with only a small number of studies conducted within a narrow range of research areas.

The third problem is that it is out of date, failing to represent emerging research directions in the field. Approached from a CDA perspective, the concept of curriculum encompasses more aspects than the existing four areas (teaching methods, testing techniques, textbook compilation, and curriculum design). Other critical areas, such as needs analysis, teaching beliefs, program evaluation, assessment, and teacher development, have been overlooked.

The above demerits may limit the value of the map when it is used as an overall framework of the TS discipline, a conceptual model for researchers to identify research gaps and position their research, a didactic tool and orientation guide in the teaching of translators and novice researchers, or a framework to review existing research on a given topic in the field, as mentioned previously. For example, when it is used as a framework in a literature review to organize existing research on translator training, reliability could be a problem because two reviewers may have inconsistent findings due to the lack of definitions for each research area. That said, an updated evidence-based version of research directions in the subbranch of translator training is necessary.

4. THE DESCRIPTIVE SURVEY OF 68 YEARS OF RESEARCH IN T&I TRAINING

The training subbranch of the TS map will be updated based on the findings of a descriptive survey of 68 years of interpreter and translator education research. This section reports on the background information of this project.

The project consisted of two phases. In a preliminary study, content analysis was used to analyze the research themes of 967 articles. The articles must meet several specific criteria to be considered for inclusion. First, the publication timeframe was restricted to the years between 2001 and 2022. Second, the sources were journals indexed in two prominent databases: the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI). These journals consisted of TS journals and non-TS journals. For non-TS journals, the selection is limited to those falling under three Web of Science categories: Linguistics, Language and Linguistics, and Educational Research. Due to logistical constraints, book chapters and journal articles published in local journals were excluded, which is a common practice in most literature reviews. Third, only articles were included. Book reviews, editorial materials, and other non-article document types were excluded. Fourth, the focus was solely on applied research related to translator and interpreter training. As outlined by Colina and Angelelli (2016), research in translation and interpreting pedagogy is divided into two main categories: cognitive processing research that indirectly influences learning, and applied research that directly addresses learning, teaching, assessment, and other issues both within and beyond the framework of CDA. Only the latter category is considered in this study.

Both deductive and inductive content analysis were used in the preliminary phase. In deductive content analysis, the CDA framework, a literature-informed construct that clarifies curricular components and their relationship, was used as the prior framework of research themes against which each article was coded. In inductive content analysis, the themes were not covered in the CDA framework but emerged from the coding process. Whenever the themes of articles were beyond those covered in the CDA framework, for example, when new themes concerning students, teachers or surrounding issues emerged, they were added to the CDA framework as separate theme clusters. This preliminary research identified six clusters of themes, CDA (ten themes), teacher (one theme), students (three themes), market and graduation (four themes), surrounding issues (six themes), and others (one theme) (Table 1). More details of the research methodology, the definition of each theme, and discussions of the identified themes will not be reported here due to space limitations (see Li, 2025, p. 3-7, p. 16-22).

Table 1. Themes of interpreter and translator education research 1

| Theme clusters | Themes |

| CDA | 1. Conceptualization of content 2. Market needs analysis 3. Learning needs analysis 4. Goal and objective 5. Belief/philosophy 6. Syllabus/curriculum design and analysis 7. Material development 8. Instruction and/or effect (reaction) 9. Assessment 10. Course/curriculum evaluation |

| Teachers | 11. Trainer education/development |

| Students | 12. Admission/recruitment 13. Learner trait 14. Learning |

| Market and graduation | 15. Thesis and research training 16. Pre-service preparation 17. Certification/accreditation 18. In-service/on-the-job training |

| Surrounding issues | 19. Program/model in focus 20. Context/policy analysis 21. T&I education history 22. User/client education 23. Literature review 24. T&I as a means to education |

| Others | 25. Others |

Based on the preliminary study, the corpus was expanded in the subsequent research phase to include 1,171 articles published in TS and non-TS journals between 1955 and 2022. The same screening criteria mentioned earlier were applied to the newly added articles. The only difference was the expanded timeframe which included the years from 1955 to 2000. The year 1955 was selected as it marked the launch of prominent TS journals such as Babel and Meta: Translators’ Journal. It is believed that the 68-year span from 1955 to 2022 provides a comprehensive representation of the literature on translation and interpreting pedagogy.

With an assumption that the preliminary round of deductive and inductive content analysis of 967 articles (2001-2022) had reached saturation, the point after which no new themes emerged from further analysis, the second research phase employed deductive content analysis. Saturation, a key concept in qualitative data analysis, occurs when additional data analysis fails to generate new themes or patterns (Bloor & Wood, 2006). In this study, saturation means that the review of 967 articles (2001-2022) was sufficient to generate reliable categories of research themes and that including more articles for analysis would not produce new themes. This assumption aligns with the practice of most literature reviews which typically focus on the most recent 10 to 20 years of research when identifying research themes (e.g., Yan et al., 2015). However, additional articles from 1955 to 2000 were included not only to provide further empirical evidence for research themes in interpreter and translator education but also to reveal the frequency of each theme over a longer span of years. Further details regarding the methodology and findings will not be discussed here due to space constraints (see Li, 2024). The two phases of research lay the foundation for the update of the training subbranch of the TS map.

5. UPDATING THE TRAINING SUBBRANCH OF THE TS MAP

Based on the identified research themes in the descriptive survey, the areas under the training subbranch are updated and presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The updated training subbranch in the TS map

Compared with the research areas in the old version, the areas in the updated training subbranch, grouped in clusters, enjoy a more compatible relationship with one another. This can be attributed to the use of a literature-informed construct that clarifies curricular components and their relationship as a conceptual framework when coding the research themes. This measure, plus the composition of definitions for each theme, can avoid a blurry division between themes and ensure a better display of the relationships between themes. The connotations of all themes are defined. For instance, material development encompasses research on the selection of texts or speech for pedagogical purposes, textbook analysis, and other related aspects, such as parallel text analysis or the design of translation task briefs. The connotations of the 24 research themes (e.g., conceptualization of content, market needs analysis) are not easy to perceive and their interpretations depend on knowledge of definitions (see Li, 2025, p. 16-22). For instance, both conceptualization of content and instruction and/or effect are related to translation or interpreting competence. Research under the subbranch of conceptualization of content refers to articles aiming to establish the construct of overall competence or a specific competence component for the design of a curriculum or course. By contrast, instruction and/or effect research is concerned with 1) pedagogical interventions (teaching methods, exercises, resources, or tools) targeting overall translation or interpreting competence or a certain competence component, with or without investigating their effect; or 2) examinations of students’ competence or skill acquisition based on observational data or of factors affecting competence/skill acquisition. Due to space limitations, the lengthy definitions will not be discussed in detail here.

Another advantage of the new version is that the generation of themes is based on a descriptive survey of the existing literature. Since the themes are based on a description of what has been researched in TS, empirical evidence is available to substantiate the update. This is different from the old version which is a product of personal conceptualizations of the TS areas.

All sub-themes of the themes are presented in Table 2. More details of the sub-themes cannot be provided here due to space limitations (see Li 2025, p. 25, p. 307-309).

Table 2. Themes and sub-themes under the updated training subbranch in the TS map 2

| Themes | Sub-themes |

| 1. Conceptualization of content | 1. Expert (professional)-novice (trainee) difference; 2. Description of professionals’ profile and activity; 3. Document analysis; 4. Industry-academia gap; 5. Others. |

| 2. Market needs analysis | 1. Construct of a competence component; 2. Construct of content for a given domain; 3. Construct of overall competence; 4. Construct of content for a specific mode. |

| 3. Learning wneeds analysis | 1. Wants; 2. Lacks. |

| 4. Goal and objective | 1. Formulation of goals and objectives; 2. Prioritization of teaching objectives in course implementation. |

| 5. Belief / philosophy | 1. Conceptualization of beliefs; 2. Belief-behavior consistency; 3. Teaching and learning belief agreement. |

| 6. Syllabus / curriculum design and analysis | 1. Case descriptions on course design rationales or course syllabi; 2. Surveys of course content. |

| 7. Material development | 1. Appropriateness of a given material type; 2. Material development principles; 3. Material content analysis; 4. Status of textbook research. |

| 8. Instruction and/ or effect (reaction) | 1. Instructional strategy; 2. Activity or exercise; 3. Computer- or technology-assisted training; 4. Training model. |

| 9. Assessment | 1. Summative and formative assessment; 2. Rubric and scoring; 3. Assessment instrument development; 4. Feedback; 5. Assessment practice survey; 6. Assessment concept and principle; 7. Assessment literacy; 8. Assessment behavior. |

| 10. Course/curriculum evaluation | 1. Course evaluation; 2. Curriculum evaluation. |

| 11. Trainer education/ development | 1. Trainer education programs or courses; 2. Trainer qualifications; 3. Trainer competence or knowledge; 4. Trainers’ affective characteristics; 5. Trainers’ behaviors. |

| 12. Admission/ recruitment | 1. Construct and content of aptitude tests; 2. Predictive validity of test items (cloze test, recall, paraphrasing, language proficiency, shadowing, emotional stability, motivation, personality traits, learning style, etc.). |

| 13. Learner trait | 1. Autonomy and motivation; 2. Anxiety, burnout, and stress; 3. Self-efficacy; 4. Miscellaneous traits (critical thinking, emotion, ethnicity, identity, ideological orientation, personality, resistance, socialization, etc.). |

| 14. Learning | 1. Learning of procedural knowledge (extra-linguistic, instrumental, linguistic and cultural, and strategic competence); 2. Learning of metacognitive knowledge (psycho-physiological and interpersonal competence); 3. Learning of declarative knowledge (translation knowledge). |

| 15. Thesis and research training | 1. Research training (teaching content, instructional methods, or assessment of research skills); 2. Translation thesis or commentary. |

| 16. Pre-service preparation | 1. Students’ employability evaluation; 2. Pedagogical activity - translation project; 3. Pedagogical activity - interprofessional education; 4. Pedagogical activity - simulation; 5. Pedagogical activity - work placements (internship); 6. Pedagogical activity - mentoring in employing institutions or professional associations; 7. Pedagogical activity - others. |

| 17. Certification/ accreditation | 1. Certification tests or systems (validity, reliability, authenticity, rubrics, etc.); 2. Connections between certification and contextual factors (candidates’ profile, training, policies, employment, etc.). |

| 18. In-service/ on-the-job training | Continuing professional development (pedagogical activities aiming at improving professionals’ knowledge, skills, or qualifications after entering their workplaces. |

| 19. Program/ model in focus | 1. Description of T&I training in a country; 2. Description of T&I training in a region; 3. Description of T&I training in an institution. |

| 20. Context/ policy analysis | Impact of policies on translator and interpreter education; Impact of social or contextual factors on translator and interpreter education. |

| 21. T&I education history | Historical development or longitudinal evolution of translation or interpreting pedagogy in a certain country or region within a given period. |

| 22. User/client education | Pedagogical activities to improve users’ knowledge about, understanding of, and attitudes towards the translation and interpreting profession and service. |

| 23. Literature review | 1. Focused literature review; 2. Systematic literature review; 3. Meta-analysis. |

| 24. T&I as a means to education | 1. T&I as an instructional method to enhance linguistic or cultural competence; 2. T&I as an assessment tool to measure linguistic or cultural competence; 3. Reconceptualization of the validity of translation in language learning; 4. Survey of views on the role of translation in language learning; 5. T&I as an instructional method to develop childhood literacy. |

In Table 3, one case is provided for each research theme under the updated training subbranch in the TS map. It is hoped that the cases may help colleagues to have a tangible understanding of what the research themes represent.

Table 3. Themes and cases

| Themes | Cases |

| 1. Conceptualization of content | Parra-Galiano (2021) conceptualized a framework of translator and reviser competences in legal translation. |

| 2. Market needs analysis | Oziemblewska and Szarkowska (2020) conducted an online survey of professionals to explore the growing demand for subtitler competences in the global market. |

| 3. Learning needs analysis | Vottonen and Kujamäki (2021) probed into students’ learning needs in theoretical knowledge by evaluating if they can justify translation solutions and use metalanguage. |

| 4. Goal and objective | Li (2019) demonstrated how to prioritize learning objectives based on analyses of students’ wants and lacks in translator and interpreter training. |

| 5. Belief/ philosophy | Kiraly (2015), moving a step further from social constructivism, emphasized the role of epistemology in better serving the education of translators. |

| 6. Syllabus/ curriculum design and analysis | Plaza-Lara (2021) described the profile of translation project managers’ competences by conducting a curricular analysis of European Master’s in Translation programs. |

| 7. Material development | Carrasco Flores (2019), responding to the insufficient attention to materials development, conducted a content analysis of the only available textbook devoted to English for Translation and Interpreting in Spain. |

| 8. Instruction and/or effect (reaction) | Bendazzoli and Pérez-Luzardo (2021) investigated students’ perceptions of a public speaking workshop in interpreter education, as reflected in their retrospective feedback. |

| 9. Assessment | Chen et al. (2022) examined how the use of scoring methods in assessing interpreting performance impacts scoring dependability. |

| 10. Course/ curriculum evaluation | Kodura (2022) reported on a case study that aims to evaluate the effectiveness of an online translation technology course during the Covid-19 pandemic. |

| 11. Trainer education/ development | Wu et al. (2021) examined how a novice translator trainer constructed her teacher identity on the job by analyzing her negotiations between identity and emotions. |

| 12. Admission/ recruitment | Blasco Mayor (2015) investigated if listening comprehension proficiency is a predictor of interpreting aptitude. |

| 13. Learner trait | Singer (2021) traced students’ longitudinal changes in their commitment to becoming translators through semi-structured interviews. |

| 14. Learning | Başer and Çetİner (2022), through the use of think-aloud protocols, examined students’ use of translation tools and challenges when translating scientific texts. |

| 15. Thesis and research training | Man et al. (2019) investigated the focus and criteria of examiners when assessing master’s dissertations of translation studies by analyzing their feedback reports. |

| 16. Pre-service preparation | Hirci (2022) investigated if translation work placement contributes to students’ transitioning to professional workplace settings and enhances their employability at a Slovenian university. |

| 17. Certification/ accreditation | Ordóñez-López (2020) examined the accreditation process for sworn translators-interpreters against the professional reality, legal translator competences, and degree programs in Spain. |

| 18. In-service/ on-the-job training | Ruiz Rosendo et al. (2021) investigated the effectiveness of a joint program to train United Nations staff interpreters who were about to assist multilingual communication in field missions. |

| 19. Program/ model in focus | Rueda-Acedo (2021) reported on the development of an undergraduate Spanish translation certificate program at an American university. |

| 20. Context/ policy analysis | Ruiz Rosendo and Conniff (2015) examine the influence of federal and state legislation on the professionalization and education of healthcare interpreters in America. |

| 21. T&I education history | Yao (2019) reported a historical study of the early development of the United Nations Training Program for Interpreters and Translators in Beijing. |

| 22. User/client education | Friedman-Rhodes and Hale (2010) explored the effectiveness of an interventional program to enhance pre-service medical practitioners’ understanding of the complexities of interpreting and perceptions of the roles of interpreters. |

| 23. Literature review | Bobadilla-Pérez and Carballo de Santiago (2022) reviewed the didactic use of audiovisual translation in foreign language classrooms. |

| 24. T&I as a means to education | Huang (2022) examined the effects of video-dubbing tasks on learners’ English-speaking proficiency, public speaking anxiety, and group cohesion. |

6. CONCLUSION

Based on a descriptive survey of 68 years of research in translator and interpreter training, this article has attempted to renew the training subbranch of the TS map. After years of update, the old training subbranch consisted of four areas, namely, teaching methods (exercises), testing techniques, textbook compilation, and curriculum design (van Doorslaer, 2007; Holmes, 1972/1988; Munday, 2001; Tao, 2005; Toury, 1995). The newly updated subbranch includes 25 areas, grouped into six clusters, specifically, curriculum development and assessment (ten themes), teacher (one theme), students (three themes), market and graduation (four themes), surrounding issues (six themes), and others (one theme). It is hoped that the enriched training subbranch can inform scholars of recent developments in interpreter and translator education research, equipping them with a sense of research context to identify research gaps and justify new research and serving as a didactic tool in the education of translators and novice researchers in the field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Table 2 was adapted with permission from Mapping the research landscape of interpreter and translator education: current themes and future directions (p. 25, p.307-309), by Xiangdong Li, 2025 (https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003487494). Copyright © 2025 by Taylor & Francis Group.

REFERENCES

Başer, Z. & Çetİner, C. (2022). Examining translation behavior of Turkish student translators in scientific text translation with think-aloud protocols. Meta, 67(2), 274-296. https://doi.org/10.7202/1096256ar

Bendazzoli, C., & Pérez-Luzardo, J. (2021). Theatrical training in interpreter education: a study of trainees’ perception. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1884425

Blasco Mayor, M. J. (2015). L2 proficiency as predictor of aptitude for interpreting: An empirical study. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 10(1), 108-132. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.10.1.06bla

Bloor, M., & Wood, F. (2006). Keywords in Qualitative Methods. Sage.

Bobadilla-Pérez, M., & Carballo de Santiago, R. J. (2022). Exploring Audiovisual translation as a didactic tool in the Secondary school foreign language classroom. Porta Linguarum, 81-96. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.vi.22307

Brighi, G. (2024). Interdisciplinarity in translation studies: A didactic model for research positioning. Perspectives, online first article. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2024.2316727

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Carrasco Flores, J. A. (2019). Analysing English for Translation and Interpreting materials: skills, sub-competences and types of knowledge. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 15(3), 326-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2019.1647920

Chen, J., Yang, H., & Han, C. (2022). Holistic versus analytic scoring of spoken-language interpreting: a multi-perspectival comparative analysis. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16(4), 558-576. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2022.2084667

Chesterman, A. (2009). The name and nature of translator studies. Hermes, 22(42), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v22i42.96844

Colina, S., & Angelelli, C. V. (2016). Translation and interpreting pedagogy. In C. V. Angelelli & B. J. Baer (Eds.), Researching translation and interpreting (pp. 108-117). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315707280

Friedman-Rhodes, E., & Hale, S. (2010). Teaching medical students to work with interpreters. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 14, 121-144.

Gentzler, E. (2001). Contemporary translation theories (Revised ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Hale, S., & Napier, J. (2013). Research methods in interpreting. Bloomsbury.

Hermans, T. (1991). Translational norms and correct translations. In K. van Leuven-Zwart & T. Naaijkens (Eds.), Translation studies (pp. 155-169). Brill.

Hirci, N. (2022). Translation Work Placement in Slovenia: a key to successful transition to professional workplace settings? Perspectives, 31(5), 900-918. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2022.2055482

Holmes, J. S. (1972/1988). The name and nature of translation studies. In J.S. Holmes (Ed.), Translated! Papers on literary translation and translation studies (pp. 67-80). Rodopi.

Huang, H. T. D. (2022). Investigating the influence of video-dubbing tasks on EFL learning. Language Learning & Technology, 26(1), 1-20. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/73489

Kiraly, D. C. (2015). Occasioning translator competence: Moving beyond social constructivism toward a postmodern alternative to instructionism. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 10(1), 8-32. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.10.1.02kir

Kodura, M. (2022). Evaluating the effectiveness of an online course in translation technology originally developed for a classroom environment. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16(3), 309-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2022.2092830

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lee, H. M. (2015). Mapping translation studies in Korea using the Holmes map of translation studies. Forum, 13(1), 65-86. https://doi.org/10.1075/forum.13.1.04lee

Li, X. (2019). Teaching translation and interpreting courses to students’ lacks and wants: an exploratory case study of prioritizing instructional objectives. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación, 78, 159-192. https://doi.org/10.5209/clac.64377

Li, X. (2024). Research in interpreter and translator education (1955-2022): a state-of-the-art review. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 18(4), 523-545. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2024.2407684

Li, X. (2025). Mapping the research landscape of interpreter and translator education: current themes and future directions. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003487494

Man, D., Xu, Y., Chau, M. H., O’Toole, J. M., & Shunmugam, K. (2019). Assessment feedback in examiner reports on master’s dissertations in translation studies. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 64, 100823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.100823

Munday, J. (2001). Introducing Translation Studies. Theories and Applications. Routledge.

Munday, J., & Vasserman, E. (2022). The name and nature of translation studies: A reappraisal. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 8(2), 101-113. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00089.mun

Munday, J., Ramos Pinto, S., & Blakesley, J. (2022). Introducing translation studies (4th ed.). Routledge.

Nouraey, P., & Karimnia, A. (2015). The map of translation studies in modern Iran: An empirical investigation. Asia Pacific Translation and Intercultural Studies, 2(2), 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/23306343.2015.1059009

O’Brien, S. (2022). Translation technologies: The dark horse of translation? In J. Franco Aixelá & C. Olalla-Soler (Eds.), 50 years later. What have we learnt after Holmes (1972) and where are we now? (pp. 93-104). Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Ordóñez-López, p. (2020). An examination of the accreditation process for sworn translators–interpreters in Spain. Perspectives, 29(6), 900-916. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1849323

Oziemblewska, M., & Szarkowska, A. (2020). The quality of templates in subtitling: A survey on current market practices and changing subtitler competences. Perspectives, 30(3), 432-453. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1791919

Palumbo, G. (2009). Key terms in translation studies. Continuum.

Parra-Galiano, S. (2021). Translators’ and revisers’ competences in legal translation: Revision foci in prototypical scenarios. Target, 33(2), 228-253. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.21065.gal

Plaza-Lara, C. (2021). Competences of translation project managers from the academic perspective: Analysis of EMT programmes. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16(2), 203-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1987085

Pym, A. (1998). Method in translation history. St Jerome.

Rueda-Acedo, A. R. (2021). A successful framework for developing a certificate in Spanish translation through community translation and service-learning. Hispania, 104, 241-258. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpn.2021.0043

Ruiz Rosendo, L., & Conniff, D. (2015). Legislation as backdrop for the professionalisation and training of the healthcare interpreter in the United States. Journal of Specialised Translation, 23, 292-315. https://jostrans.soap2.ch/issue23/art_ruiz.pdf

Ruiz Rosendo, L., Barghout, A., & Martin, C. H. (2021). Interpreting on UN field missions: a training programme. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 15(4), 450-467. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1903736

Ruokonen, M., Salmi, L., & Svahn, E. (2018). Boundaries around, boundaries within: Introduction to the thematic section on the translation profession, translator status and identity. Hermes, 58, 7-17. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb. v0i58.111655

Singer, N. (2021). How committed are you to becoming a translator? Defining translator identity statuses. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16(2), 141-157. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1968158

Snell-Hornby, M. (1991). Translation studies: Art, science or utopia? In K. van Leuven-Zwart and T. Naaijkens (Eds.), Translation studies: The state of the art (pp. 13-23). Rodopi.

Tao, Y. (2005). Translation studies and textbooks. Perspectives, 13(3), 188-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760508668991

Tarvi, L. (2008). Translation studies in tertiary education: The map-matrix meta-model of the field. Mikael, 2, 1-10.

Toury, G. (1995). Descriptive translation studies and beyond (1st ed.). John Benjamins.

Toury, G. (2012). Descriptive translation studies and beyond (revised ed.). John Benjamins.

van Doorslaer, L. (2007). Risking conceptual maps. Target, 19(2), 217-233. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19.2.04van.

Vandepitte, S. (2008). Remapping translation studies: Towards a translation studies ontology. Meta, 53(3), 569-588. https://doi.org/10.7202/019240ar

Venuti, L. (ed.) (2012). The translation studies reader (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Vottonen, E., & Kujamäki, M. (2021). On what grounds? Justifications of student translators for their translation solutions. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 15(3), 306-325. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1891514

Wu, D., Zhang, L. J., & Wei, L. (2021). Becoming a translation teacher. Revista Española De Lingüística Aplicada, 34(1), 311-338. https://doi.org/10.1075/resla.18040.wu

Yan, J. X., Pan, J., & Wang, H. (2015). Studies on translator and interpreter training: a data-driven review of journal articles 2000-12. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 9(3), 263-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2015.1100397

Yao, B. (2019). The origins and early developments of the UN Training Program for Interpreters and Translators in Beijing. Babel, 65(3), 445-464. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00100.yao

Zhao, Y., & Ma, H. (2019). Mapping translation studies in China based on Holmes/Toury map. Forum 17(1), 99-119. https://doi.org/10.1075/forum.17015.zha