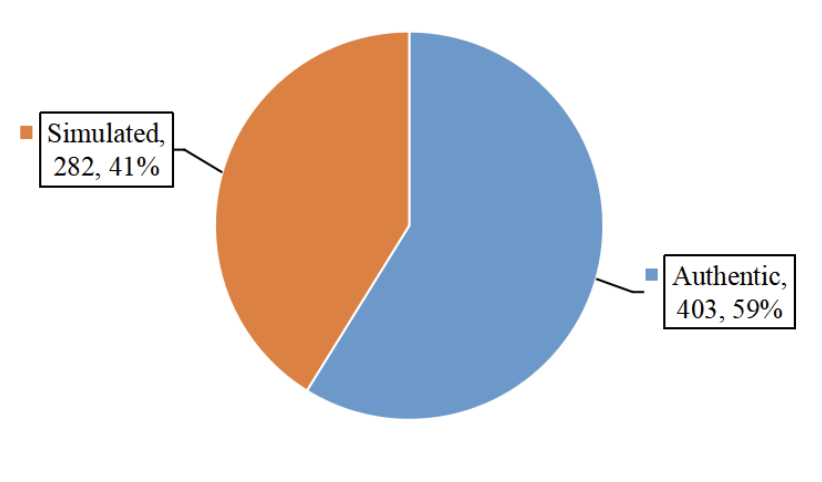

Figure 1. The authenticity of interpreting practice.

:: TRANS 28. DOSIER. Investigación en didáctica de la interpretación. Págs. 179-195 ::

-------------------------------------

Jiachen Wen

Xi’an International Studies University

ORCID: 0009-0002-7477-1476

Xiangdong Li

Xi’an International Studies University

ORCID: 0000-0002-7483-6076

-------------------------------------

Practice reports where students reflect on and learn from interpreting experiences are the most widely chosen form of graduation thesis among Master of Interpreting students in China. Though seemingly less demanding than traditional thesis, it poses different challenges for students. So far, limited research has been conducted to explore this unique form of graduation requirement. This survey aims to describe the features of Master of Interpreting (MI) students’ practice reports. A purposive sample of 685 interpreting practice reports (2015-2021) were analyzed through content analysis against a literature-informed coding scheme. The results reveal the diversified features of MI graduates’ interpreting practice and point to the lack of agreed norms on report writing. This survey informs trainers and students of the most common problems, strategies, and theoretical frameworks in problem analysis and strategy justification. Hopefully, the findings can provide pedagogical insights for trainers and students in institutions where a similar thesis form is practiced.

KEY WORDS: practice report, survey, interpreting practice features, writing norms, problems and strategies.

Los informes de práctica como trabajo fin de máster para estudiantes de interpretación: una encuesta descriptiva

Los informes de práctica, en los que los estudiantes reflexionan y aprenden de las experiencias de interpretación, son en China la forma de trabajo fin de máster más elegida entre los estudiantes de Máster en Interpretación. Aunque aparentemente menos exigente que la tesis tradicional, plantea desafíos diferentes para los estudiantes. Hasta ahora, se ha realizado un número limitado de investigaciones para explorar esta forma única de requisito de graduación. Esta encuesta tiene como objetivo describir las características de los informes de práctica entre los estudiantes de Máster en Interpretación (MI). Se analizó una muestra intencionada de 685 informes de práctica en interpretación

(2015-2021) mediante análisis de contenido frente a un esquema de codificación basado en la literatura. Los resultados revelan las características diversificadas de la práctica de interpretación entre los graduados de MI, y señalan la falta de normas acordadas sobre la redacción de informes. Esta encuesta informa a instructores y estudiantes sobre los problemas, estrategias y marcos teóricos más comunes en el análisis de problemas y la justificación de estrategias. Con suerte, los hallazgos pueden proporcionar conocimiento pedagógico para instructores y estudiantes en instituciones donde se practica una forma de tesis similar.

PALABRAS CLAVE: informe de práctica, encuesta, características de práctica en interpretación, normas de redacción, problemas y estrategias.

-------------------------------------

recibido en febrero de 2024 aceptado en abril de 2024

-------------------------------------

1. IntroducTION

The MTI (Master of Translation and Interpreting) program was established in China in 2007 to cultivate qualified translators (Master of Translation) and interpreters (Master of Interpreting). As of 2022, the number of universities with Master of Interpreting (MI) programs has reached 89. The official websites of some of the universities concerned indicate that the aver-age number of MI students enrolled each year is about 20.

The Guideline for Master of Translation and Interpreting released by China National Committee for Graduate Education of Translation and Interpreting stipulates that, to earn a degree, MI students must complete a minimum of 38 credits, a semester-long internship, a portfolio of 400-hour interpreting prac-tice recordings, and a graduation thesis.

Compared with the thesis requirement for traditional MA programs, that for MI programs is more inclusive. Traditional thesis is criticized as non-practical and cannot help students address and reflect on problems encountered in translation and interpreting practice (Mu & Li, 2019). Out of the concern to cultivate high-level professional interpreters (Mu, Zou & Yang, 2012; Sun & Ren, 2019), students are allowed to select from a wide range of options, including experimental studies, surveys, practice reports, and internship reports (Mu, 2011; Mu & Zou, 2011; Mu & Li, 2019). Of those, practice report is the most popular one. More than 85% of students tend to choose practice reports as their graduation theses (Guo, 2019; Mu & Zou, 2011; Mu & Li, 2019; Xu et al., 2020). Practice report, also called commented translation (or interpreting), is a type of self-assessment by students to reflect on their translation or interpreting process and gain professional awareness (Shih, 2018). For students who are determined to work in the translation or interpreting industry, reflecting on the problems encountered in their translation or interpreting practice is a good way to identify and fill in the knowledge gap that they may encounter in real tasks in the future.

Writing a practice report can be challenging. One reason is that there has been a lack of consensus regarding its structure and content. According to Shih (2018), practice report, as a hybrid between a reflective narrative and an academic essay, is supposed to include two sections, one devoted to theoretical issues (skopos, text types, background research, and terminology research) and the other to reflections (problems and solutions). Mu, Zou, and Yang (2012) proposed a formula consisting of six parts: task description, process description (pre-task preparation, in-task process, and post-task conclusion), case analysis (problems encountered during the practice, theories, and proposed strategies), conclusion, reference, and appendix. Given the lack of a guiding norm, the content and structure of practice reports vary from university to university. For example, as discussed in the following texts, practice reports collected from some universities are written in English while others are written in Chinese. As for structure, practice reports collected from some universities include a section devoted to literature review which is absent in reports col-lected from other universities. Research indicates that 84.9% of students believe that writing a practice report is difficult due to the absence of guiding principles (Lei, 2014; Wang, 2020). Students’ inability to generalize from details to concepts also poses problems for report writing (Shei, 2005). In spite of its popularity among students and its challenges, descriptive research on the status quo of interpreting practice reports has been rare so far.

Against such a background, this study aims to describe the profile of interpreting practice reports through content analysis of a purposive sample of 685 interpreting practice reports (2015-2021) by interpreting graduates from eight well-known universities in China against a liter-ature-informed coding scheme. Specifically, it describes the features of interpreting practice on which the practice reports are based (authenticity, modes, domains, and directions), the norms of interpreting practice reports (language, literature review, and theoretical framework), and the most common problems, strategies, and theories for problem analysis and strategy justification. It is hoped that the results can offer stakeholders a panoramic view of the features of MI students’ interpreting practice, reveal the current norm of practice report writing, and provide pedagogical insights for interpreter training. It is also hoped that colleagues beyond the Chinese context of interpreter training may find the findings applicable to their own educational contexts.

2. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This survey aims to answer three questions:

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Content analysis

This section describes the research method, which is a 10-step content analysis. Qualitative content analysis is a research method used in a wide range of disciplines, including sociology, psychology, education, business, journalism, art, and political science (Lune & Berg, 2017). It can be applied to analyze narrative responses, open-ended survey questions, interviews or focus group transcripts, textbooks, diaries, websites, advertisements, and many other verbal or visual forms (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Schreier, 2012). Lai and To (2015, p. 140) proposed ten steps as the general procedures of content analysis for researchers to follow:

Step 1: Selecting a topic

Based on the current knowledge gap in the literature review on interpreting practice reports and out of the researchers’ interest, this article aims to describe the features of MI students’ interpreting practice, the norms of MI practice reports, and the most reported problems, strategies, and theories.

Step 2: Deciding on the sample

Qualitative research usually uses non-probability sampling where units are deliberately selected to reflect particular features of the sampled population (Ritchie & Lewis, 2003). Given the attribute of this survey, purposive sampling was used (Rai & Thapa, 2015). It refers to the deliberate choice of samples representing particular characteristics (Etikan et al., 2016; Rai & Thapa, 2015). CNKI, the largest database in China containing more than three million Master theses, was used as the data source.

Step 3: Defining concepts or units of analysis

Coding units refer to the units distinguished for separate description, transcription, recording, or coding (Krippendorff, 2004). Given the purpose of the current survey, each single interpreting practice report was the unit of analysis.

Step 4: Constructing coding categories.

Creating coding categories aims to compress a large number of texts into fewer content-related categories. Both deductive and inductive category development were used to construct categories (Cho & Lee, 2014). In deductive category development, categories concerning MI students’ interpreting practice and report were formulated based on relevant literature (Gile, 2009, p. 191; Pöchhacker, 2016, pp. 23, 28; Xu, 2015, p. 288; Setton & Dawrant, 2016, p. 21; Yang & Li, 2022, p. 172; Li, 2024, p. 3). In inductive category development, new categories were added during the coding process if they were not mentioned in the literature. Due to space limitations, the five coding categories for interpreting practice features, practice report norms, problems, strategies, and theories are not presented here. They are reported in the results and discussion section (interpreting practice features: Figures 1 to 4; practice report norms: Figures 5 to 7; problems: Table 2; strategies: Table 3; and theories: Table 4). The categories of common problems encountered in students’ interpreting practice are based on Arumí Ribas (2012), Gile (2009), and Vargas Urpi (2016). The interpreting strategies reported can be found in Gile (2009), Kader and Seubert (2015), Li (2015b), and Riccardi (2005). The theory categories are based on the work of Yang and Li (2022). Some of the most important ones include effort models (Gile, 2009), interpretive theory (Lederer, 2015), skopos theory (Nord, 2018; Pöchhacker, 1995), interpreter’s role (Pöllabauer, 2015), and interpreter’s subjectivity (Leal, 2014), to name a few.

Step 5: Creating coding forms

Each practice report was coded using Microsoft Excel 2019 against the coding categories. For example, when analyzing a practice report against the inclusion of a section devoted to literature review (one of the coding categories for practice report norms), the report was coded in the Excel form as either “1” or “0”, which respectively stands for “present” or “absent”. If the literature review section was present in the report, “1” was recorded in the Excel form, otherwise “0” was recorded.

Step 6: Training coders

In content analysis, coders formulate coding categories and receive training before formal analysis to ensure reliability (Lai & To, 2015; Mayring, 2014). One of the researchers analyzed 70 reports to check the deficiencies of the coding categories for revision and amendment. After the analysis, several inappropriate classifications were revised, including inappropriate classification of interpreting fields, problems, and strategies.

Step 7: Collecting data

685 interpreting practice reports available in the CNKI database between 2015 and 2021 from eight foreign language universities were sampled. Such a purposive sample size was supposed to be adequate to reach saturation (Etikan et al., 2016). Saturation refers to the point in data analysis when no new insights are identified and further data collection and analysis are redundant (Hennink & Kaiser, 2022). More detailed descriptions of the practice reports are reported in the next section devoted to the corpus.

Step 8: Determining reliability

Reliability is important for content analysis. Schreier (2012) stated that there are two strategies to ensure the reliability of a coding framework, namely, comparisons across researchers (inter-rater reliability) and comparisons across time (intra-rater reliability). Regarding the number of units for pilot coding, 10% to 20% of the total constitute a reasonable trade-off. In this survey, Krippendorff’s alpha test was used to calculate the overall intra-coder reliability. Seventy reports (about 10% of the total) were analyzed and the frequencies of each code were recorded. Four weeks later, when the memory of the first round of coding was impossible to exert any impact, the same reports were reanalyzed. Intra-coder reliability indicates the agreement between the two rounds of analyses. The Krippendorff’s alpha (α) value was .9998, indicating very high reliability (.80 is usually considered the threshold for reliability in social sciences, Krippendorff, 2004, p. 242). Such a high agreement may be attributed to the fact that the content for analysis in the current survey is straightforward and requires few inferences.

Step 9: Analyzing data

The main analysis phase was done in this step where all the 685 practice reports were analyzed against the coding categories and the frequency of each code was counted.

Step 10: Reporting results

Trends and findings regarding the research questions were reported.

3.2. Corpus

All accessible interpreting practice reports (685) in the CNKI database between 2015 and 2021 were included. They were sampled from eight foreign language universities (BFSU = Beijing Foreign Studies University, SISU = Shanghai International Studies University, GDUFS = Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, XISU = Xi’an International Studies University, SISU = Sichuan International Studies University, BISU = Beijing International Studies University, DFSU = Dalian Foreign Studies University, and TFSU = Tianjin Foreign Studies University). Due to the delay between the date when a report was completed and the date when it was indexed in CNKI, reports in 2022 and 2023 were not available. All reports were named “author name + publication year”. Table 1 presents the number of practice reports in each year.

Table 1. The distribution of practice reports in each year (2015-2021).

| Year | Frequency | Percentage |

| 2015 | 34 | 5% |

| 2016 | 56 | 8.2% |

| 2017 | 71 | 10.4% |

| 2018 | 123 | 18% |

| 2019 | 138 | 20.1% |

| 2020 | 142 | 20.7% |

| 2021 | 121 | 17.7% |

| Total | 685 | 100% |

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Features of interpreting practice in the reports

The first research question is concerned with the features of interpreting practice on which MI students’ practice reports are based (authenticity, modes, domains, and directions).

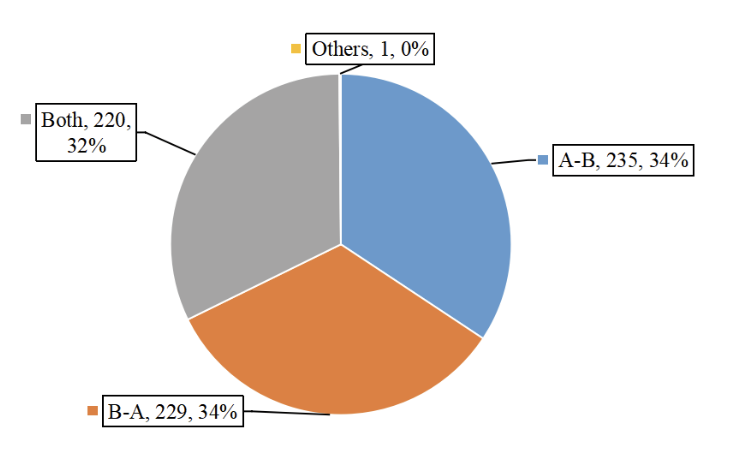

Figure 1. The authenticity of interpreting practice.

As can be seen in Figure 1, of the 685 practice reports, while 59% (403) are based on authentic interpreting practice, 41% (282) are based on simulated interpreting practice. Authentic interpreting task is an efficient pre-service training for students to establish connections with the market. However, due to the limited connection of training institutions with the market and a large number of enrolled students, not all MI students have chances to interpret in authentic working settings. Since accreditation is not part of graduation requirements and enrolled students have diversified interpreting proficiency, not all students can take the challenge of real interpreting assignments, in particular conference interpreting tasks. As a compromise, most universities organize simulated events for students who cannot find opportunities to interpret conferences that match their proficiency levels. Research indicates that, as a situated learning approach, simulations are appreciated by students as good, beneficial, and stimulating experiences, and if appropriately organized and staged, can equip students with psychological competence, strategic competence, and professionalism (Defrancq, Delputte, & Baudewijn, 2022; Li, 2015a).

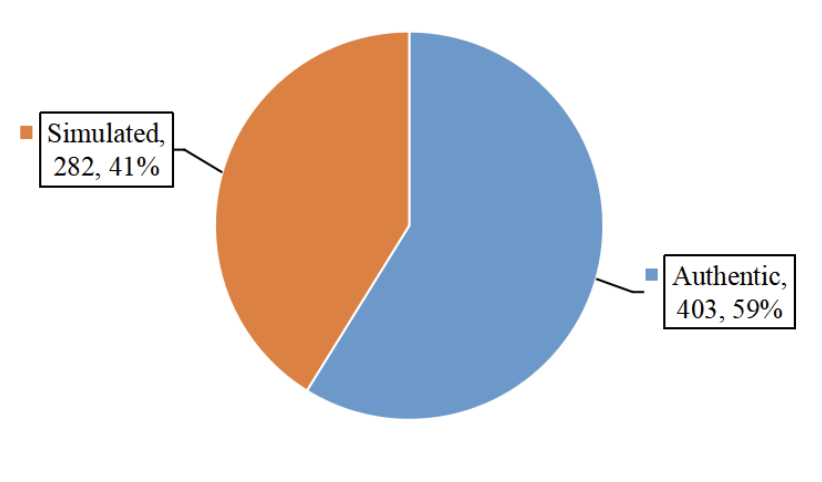

As for the interpreting modes (Figure 2), 86.9% (595) of the reports are based on consecutive interpreting and 8.9% (61) on simultaneous interpreting. This is consistent with the finding of Xu (2015) that the majority of students prefer consecutive interpreting to simultaneous interpreting. This might be due to the fact that recorded consecutive interpreting per- formances are easier for students to transcribe and analyze for self-reflections. Another possibility is that more students have consecutive interpreting experiences than simultaneous interpreting experiences.

Figure 2. The modes of interpreting practice.

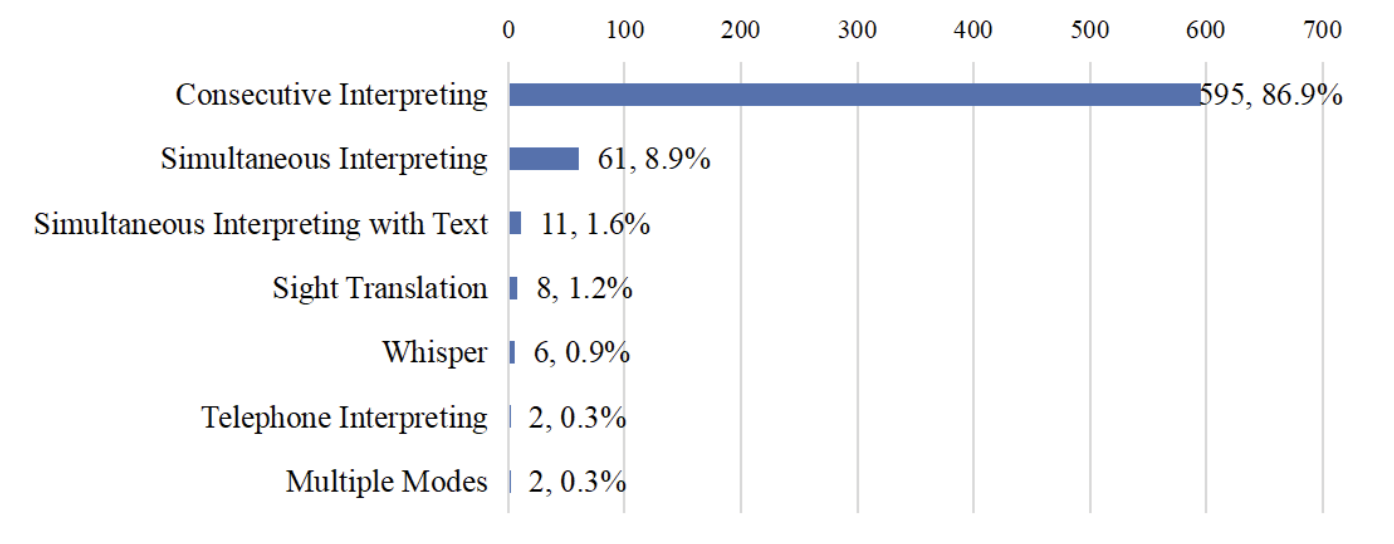

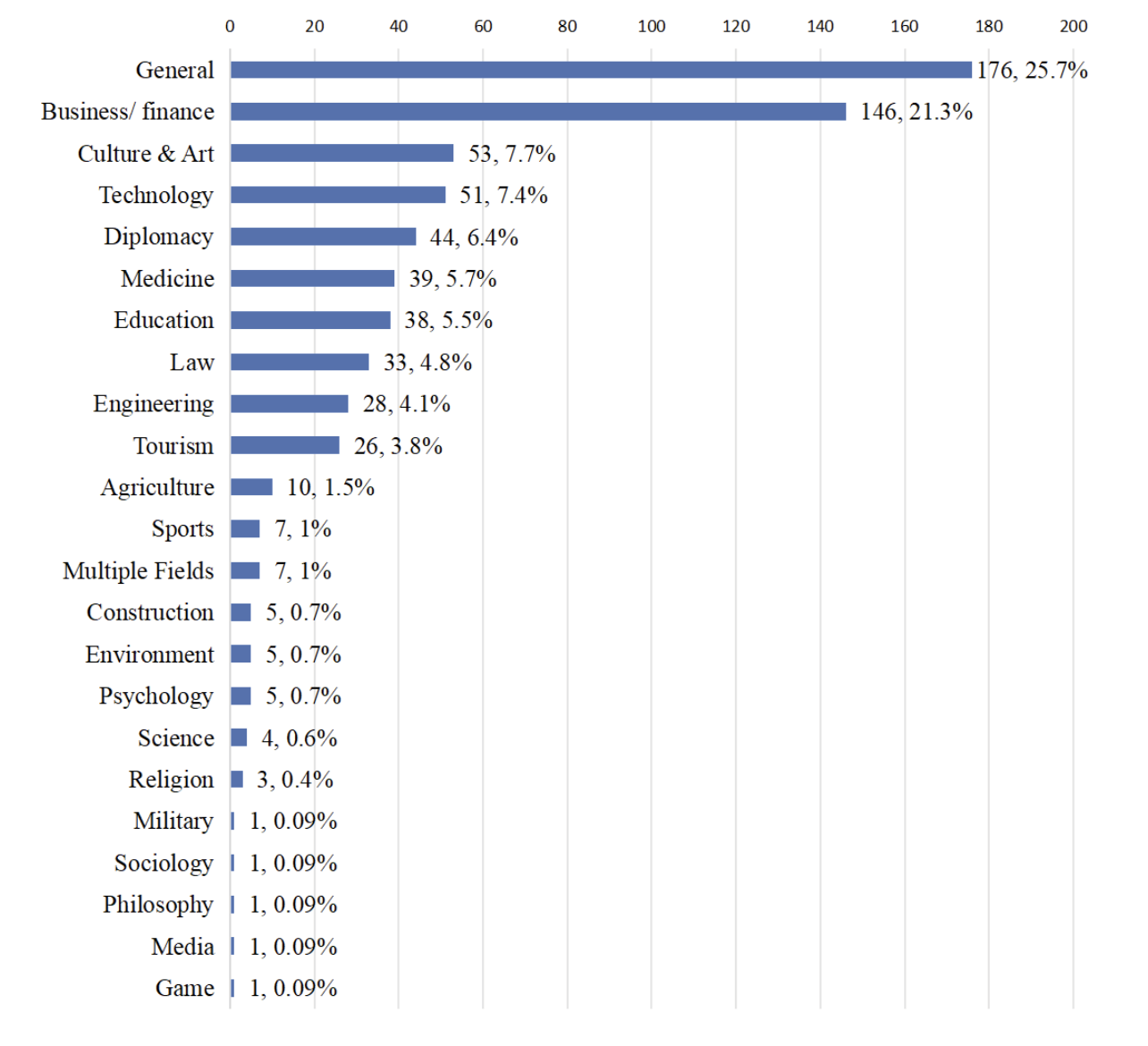

In terms of domains, the top ten areas are non-specialized or general (176 or 25.7%), business or finance (146 or 21.3%), culture and art (53 or 7.7%), technology (51 or 7.4%), diplomacy (44 or 6.4%), medicine (39 or 5.7%), education (38 or 5.5%), law (33 or 4.8%), engineering (28 or 4.1%), and tourism (26 or 3.8%). The details are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The domains of interpreting practice.

Figure 4 (see next page) shows the results concerning interpreting directions mentioned in the 685 practice reports. The frequencies for A (Chinese) – B (English) interpreting, B (En-glish) – A (Chinese) interpreting, and both directions are 235 (34%), 229 (34%), and 220 (32%) respectively.

Fig 4. The directions of interpreting practice.

4.2. Norms of interpreting practice reports

Results concerning the second research question, the norms of the sampled practice reports, will be presented from three perspectives, namely, language of presentation, literature review, and theoretical framework.

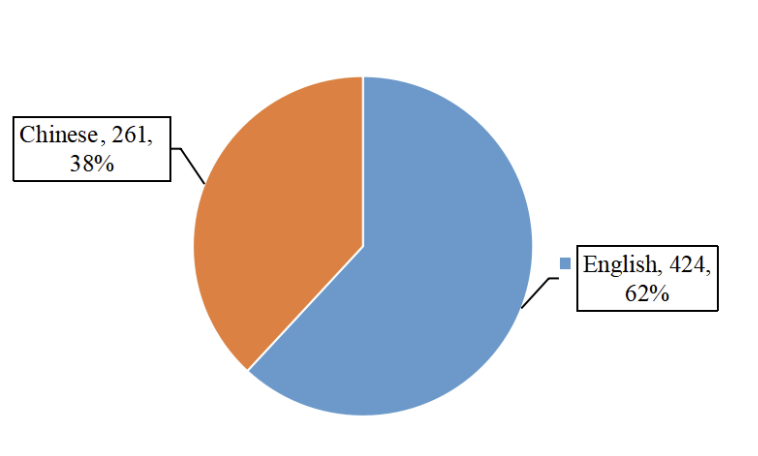

The languages of the practice reports can be seen in Figure 5. Of the 685 practice reports, while 62% (424) are written in English, 38% (261) are in Chinese. Specifically, practice reports from GDUFS, BISU, SISU (Sichuan), TFSU, and XISU are written in English, while those from DUFL are written in Chinese. Such a result indicates that the Chinese MI community have not reached an agreement as for in which language practice reports should be presented.

Fig 5. The use of writing language.

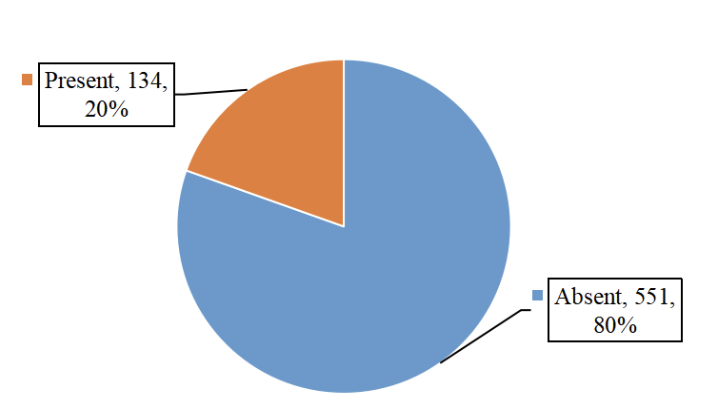

Such a lack of agreement is also reflected in the presence of literature reviews. As illustrated in Figure 6, literature review is included in 20% (134) of the practice reports, while it is absent in 80% (551) of the reports. For instance, practice reports from BISU, DUFL, and TFSU do not include a section for literature review; by contrast, literature review stands as a separate section in the reports from XISU. For the rest universities, for example, BFSU, SISU (Shanghai), GDUFS, and SISU (Sichuan), each is divided as for whether literature review should be a section of practice reports. Such disagreement may be related to the nature of practice reports, a hybrid between a reflective narrative and an academic essay. MA thesis is supposed to include a section devoted to literature review because students are supposed to synthesize the accumulated knowledge of a given topic and identify the research gaps, which serves as the foundation of advancing new knowledge in the field. Unlike traditional thesis, practice report is considered by some colleagues as a self-reflection. The purpose is for students to reflect on their practices, analyze encountered problems, and justify the use of strategies, instead of advancing new knowledge. For this reason, it seems that there is no need to review the literature. However, an alternative belief is that reviewing the literature is good for students because it helps students make rational decisions in their reflections and familiarize themselves with the basic academic standards (Mu, Zou, & Yang, 2012).

Fig 6. The presence of literature review.

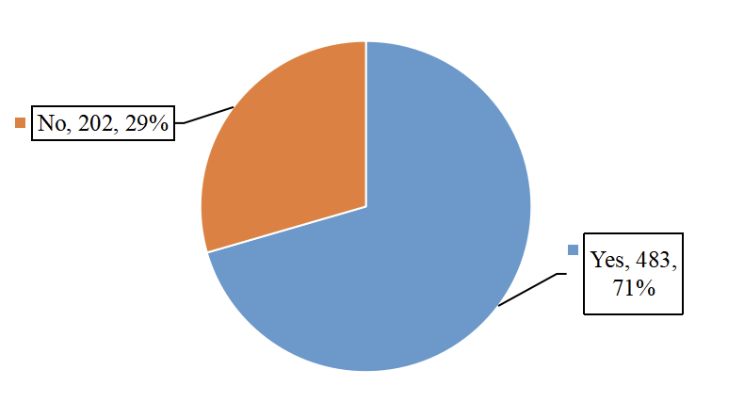

The lack of universal norms can also be seen in the inclusion of theoretical frameworks. Of the 685 practice reports, 71% (483) consist of a section devoted to theoretical frameworks and 29% (202) do not include such a section (Figure 7). For example, the practice reports from BISU, SISU (Sichuan), and TFSU all clearly list their theoretical frameworks. However, those from the rest universities are divided in this regard. This is generally consistent with the observation of Mu and Zou (2011) that about half of practice reports do not include a theoretical framework. This inadequacy may have consequences because the exclusion of theoretical frameworks in practice reports may affect students’ development of a theoretical awareness which scaffolds their self-reflection (Han & Hou, 2022).

Fig 7. The inclusion of theoretical framework.

The purpose of practice reports is to reflect on and analyze problems and justify strategic options in the interpreting process. To achieve this goal, students need to defend themselves with certain standards. Two options are possible: one is to explain problems and defend strategies using personal experiences (no theories are included in reports) and the other involves the use of established theories or theoretical frameworks in the literature (theories are included in their reports). Compared with personal experiences which may be biased or limited in one way or another due to the lack of public verification and criticism, established theories are critically reviewed by peers or empirically validated. Therefore, the inclusion of theories may better convince the readers about students’ problem analysis and strategy justification than using personal experiences.

One disadvantage of the lack of standardization or guiding norms concerning the writing language, literature review, and theoretical framework is that it is difficult to compare the content and quality of practice reports across space and time.

4.3. The most common problems, strategies, and theories

This section is devoted to the results concerning the third research question, the most reported problems, strategies, and theories in MI students’ interpreting practice reports.

As displayed in Table 2, comprehension problem triggers – linguistic ones (1073, 44.3%), are the most frequently encountered problems by MI students during interpreting practice, followed by comprehension problem triggers – extra-linguistic ones (542, 22.4%), reformulation problems triggers (225, 9.3%), note-taking and reading problem triggers (203, 8.4%), psychological status (131, 5.4%), and working environment-related problem triggers (87, 3.6%). The category of “not clearly stated” indicates that there are 35 interpreting practice reports that do not mention any problems, violating the essence of practice report which is to identify problems, analyze their causes, and propose strategies (Ren & Sun, 2019).

Table 2. Problems*

| Codes | Sub-codes | Frequency | |

| Comprehension (input) problem triggers: Linguistic ones | Unfamiliar terms, acronyms, set expressions | 242 (10.0%) | 1073 (44.3%) |

| Poor speech delivery (low voice, halting delivery, unclear pronunciation, mispronunciation, redundancy/false start etc.) | 150 (6.2%) | ||

| Strong accents | 139 (5.7%) | ||

| Fast delivery | 119 (4.9%) | ||

| Long and complex sentences | 113 (4.7%) | ||

| Difference in syntactic structures between working languages (asymmetrical structures) | 68 (2.8%) | ||

| Unfamiliar words | 66 (2.7%) | ||

| Numbers | 64 (2.6%) | ||

| Non-standard grammar (use of interlanguage varieties) | 39 (1.6%) | ||

| Difference in word perception between working languages (different distribution of content words, different degrees of morphological and phonological redundancy, different rate of homophony, etc.) | 37 (1.5%) | ||

| Unusual language or rhetorical style | 21 (0.9%) | ||

| Sound perception failure (due to liaison, weak form, elision, assimilation, etc.) | 15 (0.6%) | ||

| Comprehension (input) problem triggers: Extra-linguistic ones | Lack of subject-specific knowledge | 174 (7.2%) | 542 (22.4%) |

| Cultural elements (e.g., culture-loaded words, jokes, figures of speech, idioms, proverbs, etc.) (apply to both SI and CI but should be tackled through different strategies) | 110 (4.5%) | ||

| High or low information density (low or high redundancy) | 110 (4.5 %) | ||

| Eccentric reasoning patterns | 45 (1.9%) | ||

| Lack of world knowledge (common sense) | 34 (1.4%) | ||

| Lack of coherence (poor organization of ideas) | 34 (1.4%) | ||

| Lack of cohesion (lack of connective devices) | 28 (1.2%) | ||

| Unfamiliarity with the culture-specific genre or rhetorical conventions of the source speech (deliberate ambiguity and implicit way of rejection in Japan) | 7 (0.3%) | ||

| Reformulation (output) problem triggers | Slow or no access to correspondent equivalents of the SL (semantic retrieval problem) | 91 (3.8%) | 225 (9.3%) |

| Lack of equivalents between working languages (culture-loaded words) | 33 (1.4%) | ||

| No awareness of self-monitoring | 30 (1.2%) | ||

| Interference from the source language | 27 (1.1%) | ||

| Lack of awareness of register and style | 20 (0.8%) | ||

| Failure to transcode less-contextualized elements (terms, pat phrases, numbers, etc.) | 14 (0.6%) | ||

| Inadequate linguistic resources for idiomatic expression | 10 (0.4%) | ||

| Note-taking and reading problem triggers | Difficulties in understanding notes | 77 (3.2%) | 203 (8.4%) |

| Unclear notes | 59 (2.4%) | ||

| Difficulties in what to note (more than necessary, failure to note connectors, etc.) | 39 (1.6%) | ||

| Difficulties in how to note (not economical, too many signs, etc.) | 28 (1.2%) | ||

| Psychological status | Nervousness | 61 (2.5%) | 131 (5.4%) |

| High pressure | 36 (1.5%) | ||

| Lack of concentration (attention lapse) | 17 (0.7%) | ||

| Lack in confidence | 17 (0.7%) | ||

| Working environment-related problem triggers | Poor sound quality | 54 (2.2%) | 87 (3.6%) |

| Equipment/technology problems | 28 (1.2%) | ||

| No access to communicative context (in remote interpreting) | 5 (0.2%) | ||

| Attention splitting and coordination | Inappropriate division of attention between listening, memorizing and note-taking (specific to CI) | 54 (2.2%) | 64 (2.6%) |

| Inappropriate division of attention between listening and production (specific to SI) | 10 (0.4%) | ||

| Others (specify) | 45 (1.9%) | 45 (1.9%) | |

| Not clearly stated | 35 (1.4%) | 35 (1.4%) | |

| Memory failure | Memory overload due to a long segment of source speech (CI) | 12 (0.5%) | 19 (0.8%) |

| Failure to recall information due to attention lapse | 7 (0.3%) | ||

*Note: different from the results reported previously, the categories of problems are not mutually exclusive; in other words, one report may mention several problems. Therefore, the frequencies can be larger than 685.

Specifically, unfamiliar terms/acronyms/set expressions (242, 10.0%) are the most frequently encountered problem. Other frequently mentioned problems are lack of subject-specific knowledge (174, 7.2%), poor speech delivery (150, 6.2%), strong accents (139, 5.7%), fast delivery (119, 4.9%), long and complex sentences (113, 4.7%), cultural elements (110, 4.5%), high or low information density (110, 4.5%), slow or no access to correspondent equivalents of the SL (91, 3.8%), and difficulties in understanding notes (77, 3.2%).

Table 3. Strategies

| Codes | Sub-codes | Frequency | |

| Reformulation strategies | Omission | 316 (14.1%) | 1381 (61.6%) |

| Addition | 311 (13.9%) | ||

| Paraphrasing | 162 (7.2%) | ||

| Compression | 131 (5.8%) | ||

| Generalization | 99 (4.4%) | ||

| Morpho-syntactic transformation | 70 (3.1%) | ||

| Adaptation | 42 (1.9%) | ||

| Simplification | 38 (1.7%) | ||

| Reproduction | 36 (1.6%) | ||

| Repair | 33 (1.5%) | ||

| Repetition | 27 (1.2%) | ||

| Transcodage | 21 (0.9%) | ||

| Attenuation/softening | 21 (0.9%) | ||

| Substitution | 20 (0.9%) | ||

| Consulting resources in the booth | 12 (0.5%) | ||

| Approximation | 11 (0.5%) | ||

| Nonverbal communication/using body language | 10 (0.4%) | ||

| Referring listeners to an information source | 6 (0.3%) | ||

| Transfer/instant naturalization | 5 (0.2%) | ||

| Completion | 5 (0.2%) | ||

| Stylistic adjustment | 5 (0.2%) | ||

| Preventative strategies | Off-line strategies | 256 (11.4%) | 517 (23.1%) |

| Restructuring | 129 (5.8%) | ||

| Chunking/salami | 86 (3.8%) | ||

| Taking notes | 20 (0.9%) | ||

| Visualization | 17 (0.8%) | ||

| Décalage/time lag/extending or narrowing EVS | 9 (0.4%) | ||

| Comprehension strategies | Asking the speaker for clarification | 104 (4.6%) | 238 (10.6%) |

| Anticipation | 49 (2.2%) | ||

| Inferencing | 35 (1.6%) | ||

| Waiting/delaying response | 23 (1.0%) | ||

| Personal involvement | 15 (0.7%) | ||

| Stalling | 6 (0.3%) | ||

| Resorting to world knowledge | 6 (0.3%) | ||

| Translation strategies | 47 (2.1%) | 47 (2.1%) | |

| Not clearly stated | 40 (1.8%) | 40 (1.8%) | |

| Others (specify) | 19 | 19 (0.8%) | |

As for strategies, as shown in Table 3, the most mentioned category of strategies is reformulation strategies (1381, 61.6%), followed by preventive strategies (517, 23.1%) and comprehension strategies (238, 10.6%). Of the 685 interpreting practice reports, 40 reports did not clearly mention strategies. Some only analyzed the problems and difficulties encountered in the interpreting process without proposing specific strategies to solve them. Since the essence of an MTI practice report is to point out and analyze problems encountered during interpreting practice and propose strategies (Sun & Ren, 2019), it seems that some MI students do not have such an awareness.

The most popular strategies proposed in students’ interpreting practice reports are omission (316, 14.1%), addition (311, 13.9%), off-line strategies (256, 11.1%), paraphrasing (162, 7.2%), compression (131, 5.8%), restructuring (129, 5.8%), and asking the speaker for clarification (104, 4.6%), generalization (99, 4.4%), chunking/salami (86, 3.8%), and morpho-syntactic transformation (70, 3.1%). It is generally consistent with Li’s (2013) finding that omission (85, 21%) is the most sought-after interpreting strategy among students.

One noticeable trend that deserves mentioning is the category of “off-line strategies”. Off-line strategies are mentioned in 256 of the 685 interpreting practice reports. Different from on-site strategies that could have been used in the interpreting process to prevent or solve problems, offline strategies refer to strategies that can be used in future interpreting practice, e.g., preparation, enhancement of language or note-taking skills, etc. Since offline strategies do not help interpreters to reflect on their interpreting practice but point to future practices, they are not strongly recommended by trainers.

As presented in Table 4, 83 theories are mentioned in the 685 practice reports. The most frequent theories are effort models (82, 11.5%), interpretive theory (74, 10.4%), skopos theory (44, 6.2%), interpreter’s role (40, 5.6%), and interpreter’s subjectivity (28, 3.9%). This is consistent with the observations of Zhang (2020) who stated that the most frequently cited theories in MTI students’ reports are effort models, interpretive theory, and skopos theory. It is also consistent with the finding of Xu (2014) who concluded that the most frequently mentioned theories in journal articles in China are the interpretive theory and effort models.

Table 4. The frequency of theories

Theories |

Frequency |

| No theoretical framework | 202 (28.5%) |

| Effort models | 82 (11.5%) |

| Interpretive theory | 74 (10.4%) |

| Skopos theory | 44 (6.2%) |

| Interpreter’s role | 40 (5.6%) |

| Interpreter’s subjectivity | 28 (3.9%) |

| Redundancy | 22 (3.1%) |

| Relevance theory | 17 (2.4%) |

| Disfluency | 17 (2.4%) |

| Schema theory | 16 (2.3%) |

| Explicitation | 11 (1.5%) |

| Interpreter’s visibility | 11 (1.5%) |

| Cooperative principle | 10 (1.4%) |

| Self-repair | 9 (1.3%) |

| Cohesion and coherence | 8 (1.1%) |

| Interpreting quality assessment | 7 (1.0%) |

| Error analysis | 7 (1.0%) |

| Turn-taking | 7 (1.0%) |

| Understanding, memorizing, expression and emergency response framework of interpretation analysis | 6 (0.8%) |

| Participation framework | 5 (0.7%) |

| Adaptation theory | 5 (0.7%) |

| Others (specify) | 82 (11.5%) |

5. CONCLUSIONS

This survey aims to describe the features of Master of Interpreting (MI) students’ practice reports, namely the features of their interpreting practice, the norms of their practice reports, and the most reported problems, strategies, and theories.

Results indicate that 403 (59%) of the practice reports are based on authentic interpreting practice while 282 (41%) are based on simulated interpreting. Consecutive interpreting (595, 86.9%) is the dominant mode of interpreting practice, compared with simultaneous interpreting (61, 8.9%), simultaneous interpreting with text (11, 1.6%), and sight translation (8, 1.2%). As for domains, 22 domains were identified in the 685 practice reports, among which general (176, 25.7%), business or finance (146, 21.3%), culture and art (53, 7.7%), technology (51, 7.4%), and diplomacy (44, 6.4%) are among the top five areas. The interpreting directions are evenly distributed, Chinese-English (235, 34%), English-Chinese (229, 34%), and both (220, 32%).

There is a lack of a standardized norm to guide the writing of practice reports. The results indicate that the choice of writing language varies. While 62% (424) are written in English, 38% (261) are in Chinese. A similar problem exists as for the inclusion of literature reviews and theoretical frameworks. While some reports included literature reviews and theoretical frameworks (134, 20%; 483, 71%), others excluded both.

As for the most common problems, strategies, and theories, comprehension problems, specifically, linguistic and extra-linguistic triggers, are the most frequently encountered problem triggers by MI students during interpreting practice. The most frequent linguistic problems include unfamiliar terms, acronyms, set expressions, poor speech delivery (low voice, halting delivery, unclear pronunciation, mispronunciation, redundancy/false start etc.), strong accents, fast delivery, and long and complex sentences. The most common extra-linguistic triggers are lack of subject-specific knowledge, cultural elements, and high information density. Generally, more reformulation strategies are proposed in students’ interpreting practice reports than preventative and comprehension strategies. Specifically, the most common strategies include omission, addition, paraphrasing, compression, off-line strategies, restructuring, asking the speaker for clarification, generalization, and chunking. The top five most common theories are effort models, interpretive theory, skopos theory, interpreter’s role, and interpreter’s subjectivity.

By exploring the status quo of interpreting practice reports, this survey provides a panoramic view of interpreting practice reports as a form of graduation thesis among MI students in China. It is hoped that the findings can provide insights for the writing of interpreting practice reports and call for community actions to reach a consensus on the norms of practice reports. The findings concerning the reported problems, strategies, and theories may inform the curricular renewal of MI programs to meet students’ learning needs.

One limitation of this survey lies in the sampling strategy. As qualitative research, it collected a large convenience sample of 685 practice reports. However, like all other qualitative research, caution should be taken when efforts are made to generalize the findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful for the insightful comments from the editor and reviewers. This article is based on part of the first author’s unpublished thesis submitted to Xi’an International Studies University. The second author is the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

Arumí Ribas, M. (2012). Problems and strategies in consecutive interpreting: A pilot study at two different stages of interpreter training. Meta, 57(3), 812-835. https://doi.org/10.7202/1017092ar

Cho, J. Y., & Lee, E. (2014). Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. The Qualitative Report, 19(32), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1028

Defrancq, B., Delputte, S., & Baudewijn, T. (2022). Interprofessional training for student conference interpreters and students of political science through joint mock conferences: An assessment. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16(1), 39-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2021.1919975

Dong, Y., Li, Y., & Zhao, N. (2019). Acquisition of interpreting strategies by student interpreters. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 13(4), 408-425. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2019.1617653

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (Revised ed). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.8

Guo, S. (2019). A survey of the status quo of MTI degree theses in universities in Shaanxi Province [陕西省高校MTI专业学位毕业论文现状调研]. Innovative Research on Foreign Language Education and Translation Development [外语教育与翻译发展创新研究], 8, 182-187.

Han, Z., & Hou, X. (2022). Theoretical frameworks in translation practice reports of MTI students [MTI翻译实践报告写作中的理论框架问题]. Technology-assisted Foreign Languages Education [外语电化教学], 5, 25-30.

Hennink, M. & Kaiser, B. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292(6), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523.

Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Kader, S., & Seubert, S. (2015). Anticipation, segmentation…stalling? How to teach interpreting strategies. In D. Andres & M. Behr (Eds.), To know how to suggest…: Approaches to teaching conference interpreting (pp. 125-144). Frank & Timme.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428108324513

Lai, L. & To, W. (2015). Social media content analysis: A grounded approach. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 16(2), 138-152. http://www.jecr.org/sites/default/files/16_2_p05.pdf

Leal, A. (2014). Truth in translation: Interpreters’ subjectivity in the truth and reconciliation hearings in South Africa. In K. Kaindl & K. Spitzl (Eds.), Transfiction: Research into the realities of translation fiction (pp. 233-246). John Bejamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.110.16lea

Lederer, M. (2015). Interpretive theory. In F. Pöchhacker (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of interpreting studies (pp. 206-208). Routledge.

Lei, B. (2014). Situation of MTI interpreting dissertation writing: A survey in 10 universities in China [master’s thesis]. Guangdong University of Foreign Studies.

Li, X. (2013). Are interpreting strategies teachable? Correlating trainees’ strategy use with trainers’ training in the consecutive interpreting classroom. The Interpreters Newsletter, 18(9), 105-128. http://hdl.handle.net/10077/9754

Li, X. (2015a). Mock conference as a situated learning activity in interpreter training: A case study of its design and effect as perceived by trainee interpreters. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 9(3), 323-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2015.1100399

Li, X. (2015b). Putting interpreting strategies in their place: Justifications for teaching strategies in interpreter training. Babel, 61(2), 170-192. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.61.2.02li

Li, X. (2024). Towards a set of theoretical frameworks to scaffold students’ reflections in interpreter training [Manuscript submitted for publication]. School of Translation Studies, Xi’an International Studies University.

Lian, J. K. M., Foo, Z. Y., & Ling, F. Y. Y. (2018). Value of internships for professional careers in the built environment sector in Singapore. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 25(1), 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-09-2015-0133

Lune, H., & Berg, B., L. (2017). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (9th ed.). Pearson.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt.

Monique H. M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292(C), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Mu, L. (2011). Exploring the modes of MTI degree thesis [翻译硕士专业学位论文模式探讨]. Foreign Language Learning Theory and Practice [外语教学理论与实践], 1, 77-82.

Mu, L., & Li, W. (2019). Rethinking the writing norms of MTI graduation theses: An analysis based on 704 graduation theses [翻译硕士专业学位论文写作模式的再思考:基于704篇学位论文的分析]. Academic Degrees & Graduates Education [学位与研究生教育], 11, 33-39.

Mu, L., & Zou, B. (2011). A survey of MTI graduation theses and writing [翻译硕士专业学位毕业论文调研与写作探索]. Chinese Translators Journal [中国翻译], 5, 40-45.

Mu, L., Zou, B., & Yang, D. (2012). Exploring the writing norms of MTI graduation theses [翻译硕士专业学位论文参考模板探讨]. Academic Degrees & Graduates Education [学位与研究生教育], 3, 24-30.

Nord, C. (2018). Translating as a purposeful activity: Functionalist approaches explained (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351189354

Pöchhacker, F. (1995). Simultaneous interpreting: A functionalist perspective. Hermes: Journal of Language and Communication Studies, 14, 31-53. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v8i14.25094

Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/ 9781315649573

Pöllabauer, S. (2015). Role. In F. Pöchhacker (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of interpreting studies (pp. 355-359). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/ 9781315678467

Prescott, P., Gjerde, K. P., & Rice, J. L. (2021). Analyzing mandatory college internships: Academic effects and implications for curricular design. Studies in Higher Education, 46(11), 2444-2459. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1723531

Rai, N., & Thapa, B. (2015). A study on purposive sampling method in research. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Parthiban_Govindasamy/post/

Riccardi, A. (2005). On the evolution of interpreting strategies in simultaneous interpreting. Meta, 50(2), 754-767. https://doi.org/10.7202/011016ar

Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage.

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage.

Setton, R., & Dawrant, A. (2016). Conference interpreting: A complete course. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.120

Shei, C. C. (2005). Translation commentary: A happy medium between translation curriculum and EAP. System, 33(2), 309-325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2005.01.004

Shih, C. Y. (2018). Translation commentary re-examined in the eyes of translator educators at British universities. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 30, 291-311. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10055523

Sun, S., & Ren, W. (2019). Exploring the modes of MTI degree thesis [翻译硕士学位论文模式探究]. Chinese Translators Journal [中国翻译], 4, 33-39.

Vargas Urpi, M. (2016). Problems and strategies in public service interpreting as perceived by a sample of Chinese-Catalan/Spanish interpreters. Perspectives, 24(4), 666-678. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2015.1069861

Wang, F. (2020). A survey on the status of MTI dissertation writing and its implications for teaching: A case study of a university in southwest China [翻译硕士(MTI)论文写作状况调查及对教学的启示: 以西南某高校为例]. English Square [英语广场], 118, 50-55.

Xu, M., Zhao, T., & Zong, W. (2020). On translator training in industry-specific universities in China: A case study of 16 MTI programs. Lebende Sprachen, 65(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2020-0001

Xu, Z. (2015). Doctoral dissertations in Chinese interpreting studies: A scientometric survey using topic modeling. Forum, 13(1), 115-117. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.1277v1

Xu, Z. (2015). The past, present and future of Chinese MA theses in interpreting studies: A scientometric survey. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 23(2), 284-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2015.1011175

Xu, Z., & Pekelis, L. (2015). Chinese interpreting studies: A data-driven analysis of a dynamic field of enquiry. PeerJ, 3, e1249. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1249

Yang, Y., & Li, X. (2022). Which theories are taught to students and how they are taught: A content analysis of interpreting textbooks. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación, 92, 167-185. https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/clac.78327

Zhang, L. (2020). A survey report of MI theses in three foreign studies universities in China (2009-2019) [master’s Guangdong University of Foreign Studies.