:: TRANS 26. MISCELÁNEA. Teoría y generalidades. Págs. 65-85 ::

Simplification in specialized and non-specialized discourse: Broadening CBTS to multi-discourse analysis

-------------------------------------

Virginia Mattioli

Independent Researcher

ORCID: 0000-0001-9895-4416

-------------------------------------

This paper intends to contribute to research on the simplification hypothesis by incorporating a multi-discourse analysis. The study compares non-specialized and academic specialized discourse with the aim of describing their similarities and difference in terms of syntactic and stylistic simplification. Considering two variables (non-specialized/specialized discourse and original/translated texts) allows for examination of which has a greater influence on the tendency towards simplification. According to the adopted corpus-based methodology, four corpora are compiled, including original and translated English texts representing non-specialized and academic discourse. Then, simplification-related features (lexical variety, lexical density, mean sentence length, use of subordination and non-finite sentences) are determined and identified in each corpus. The comparison of the results across different corpora shows signs of simplification in both types of discourse. However, each presents different linguistic features, suggesting that simplification is more related to the type of discourse than to the original or translated nature of the analyzed texts.

KEY WORDS: corpus-based translation studies, translation universals, simplification, academic discourse, multi-discourse analysis.

La tendencia hacia la simplificación en el discurso especializado y no-especializado: ampliando el alcance de los estudios de traducción basados en corpus al análisis multidiscursivo

Este estudio pretende enriquecer la investigación sobre la hipótesis de simplificación analizándola en distintos tipos de discurso. El objetivo principal es identificar semejanzas y diferencias entre discurso no-especializado y especializado académico en cuanto a la tendencia a la simplificación sintáctica y estilística. La introducción de dos variables en el estudio (discurso no-especializado/especializado académico y textos originales/traducidos) permite determinar cuál tiene una mayor influencia en la tendencia a la simplificación. Tras compilar cuatro corpus de textos ingleses que representan el discurso no-especializado y especializado académico en sus versiones originales y traducidas, se determinaron los rasgos lingüísticos relacionados con la simplificación (variedad léxica, densidad léxica, longitud oracional promedio, hipotaxis, oraciones no finitas) y se identificaron en cada conjunto mediante una metodología de corpus. La comparación de los resultados muestra que, si bien ambos tipos de discursos presentan una tendencia hacia la simplificación, cada uno presenta rasgos lingüísticos distintos, lo que sugiere una mayor relación de dicha tendencia con el tipo de discurso que con la naturaleza original o traducida de los textos.

palabras clave: estudios de traducción basados en corpus, universales de traducción, simplificación, discurso académico, análisis multidiscursivo.

-------------------------------------

recibido en octubre de 2021 aceptado en septiembre de 2022

-------------------------------------

1. IntroducTION

Although several studies have been undertaken on simplification across translated and original sets of texts (Laviosa, 1997, 1998a; Xiao, 2010) or across different registers and types of discourses (Biber and Grey, 2010, 2019), studies that join both sets of variables are still rare (Kruger and Rooy, 2012), widening the research focus to incorporate a multi-discourse analysis. To address such a gap, this study looks at simplification from a wider, multi-discourse perspective, by examining the hypothesis of simplification in texts of different natures (original or translated) and different types of discourse (non-specialized and specialized academic discourse). The results will highlight similarities and differences between (un)specialized discourses that will contribute to the knowledge on the simplification hypothesis.

Concretely, this research aims to compare stylistic and syntactic simplification across a set of corpora, compound by original and translated English texts, representing non-specialized and specialized academic discourse (AD). Non-specialized texts analyzed in this study include newspapers and novels. In the attempt to establish the criteria needed to assess L2 fluency, the Dirección General de Educación Básica (1979, p. 15) defined the passive written knowledge of the advanced level as the ability to “quickly read and understand any type of non-specialized text” proposing newspapers and novels as examples of such types of texts. Similarly, Cabré et al. (2010, p. 304) consider texts proceeding from newspapers “plain texts” and contrast them to specialized texts. Actually, neither novels nor newspaper texts present the commonly accepted features (Cabré, 2002) of specialized texts: they do not focus on topics of specialized fields of knowledge; they do not use specific terminology and linguistic features; they do not show stylistic conventions accepted and recognized by a certain, specialized community of experts as characteristic of a specific textual class; and journalists and novel authors are not necessary experts on any specific area of knowledge, an essential characteristic for the production of any specialized texts (Cabré, 2002). As a result, several previous studies (Cabré, 2002; Cabré et al., 2010) used newspaper texts to represent non-specialized discourse. On the contrary, AD presents all the three factors that, according to Gotti (2008), make it a specialized discourse: a specific type of user, namely the academic community; a concrete domain of use or specific setting, represented by the academic environment; and a special application in that setting, that is, its use in the production of academic texts. As a specific discourse, AD operates with its own peculiar, socially-constructed conventions (Flower, 1990) and includes a variety of different context-specific practices that can be specific to a certain discipline or common to all of them (Flower, 1990). Due to these characteristics, AD can be compared to the non-specialized discourse in a multi-discourse analysis in order to study simplification in specialized and non-specialized texts. The introduction of a second variable representing the type of discourse in the study of simplification will also allow for establishing whether this tendency is totally due to the translation process or whether it is influenced by the type of discourse within the texts themselves.

Among the several types of specialized discourse, this study focuses concretely on English AD because, similarly to translation, it seems to tend towards syntactic simplification. Although it is commonly thought of as elaborate and explicit, Biber and Gray (2010) demonstrate that some of the syntactic structures characterizing AD can be considered “simpler” than spoken conversations. The results of their large-scale study comparing the structures of both types of discourse in English show that AD employs fewer subordinate clauses (particularly finite dependent ones), instead preferring condensed structures constituted by phrasal modifiers embedded in noun phrases. Biber and Gray (2010) therefore conclude that AD can be described more faithfully as “structurally ‘compressed’” than as “structurally ‘elaborated’” (Biber and Gray, 2010, p. 2). As for translation, the translation universals (TU) hypothesis of simplification (Baker, 1993) contends that translated texts are simpler than the originals in every respect, including syntactic structures (Xiao and Yue, 2009). Syntactically, translations have simpler clausal relationships, exhibiting more unconnected independent clauses than complex sentences formed by secondary dependent clauses.

In what follows, a theoretical framework is presented, describing the current state of the research on simplification in translation studies, as one of the hypotheses of TU, with a particular emphasis on the proposals for its operationalization and on the attempts of several authors to corroborate it. The section closes by highlighting the importance of such studies to the development of corpus-based translation studies (CBTS), which will be explained further below. Here, the origins of the corpus-based methods are briefly introduced, highlighting their strict relation with the TU hypothesis and, specifically, with simplification. Then, the advantages and disadvantages of this methodology are presented, demonstrating the usefulness of the adopted method for the present research. The paper then describes its objective, hypothesis and research questions and explains the adopted methodology. Finally, the results are presented and discussed. The contribution closes with some final remarks about the outcomes and their implications in the discipline from a theoretical and methodological perspective.

2. Theoretical frame

2.1. Research on simplification in translation studies

One of the most debated topics in translation studies is the hypothesis of translation universals first proposed by Mona Baker (1993) to describe translated language and establish principles with which to predict translation phenomena and behavior (Mattioli, 2018). According to Baker (1993), TU are intrinsic features of translated texts that characterize all translations, independent of their source and target languages, and distinguish them from original texts. Originally, Baker (1993) identified five TU: explicitation, or a translator’s tendency to use an explicit style and to add explanations to the target text (Xiao and Yue, 2009); simplification, that is, the preference for simpler language than that used in the original text (Zanettin, 2013) at any level, whether lexical, syntactic or stylistic (Xiao and Yue, 2009); normalization, referred to a translator’s inclination to conform to target language conventions rather than maintain source language patterns (Zanettin, 2013) —in Venuti’s (1995) terms, a preference for domestication; “levelling out” suggesting that translations that are “less idiosyncratic and more similar to each other than original texts” (Zanettin, 2013, p. 23); and a tendency to avoid repetition found in the source material.

Subsequently, many authors have contributed to the TU hypothesis in an attempt to corroborate the existence of the features proposed by Baker (1993) in different language pairs (Laviosa, 1998a; Mauranen, 2004; Corpas Pastor et al., 2008) and to identify further universals. These efforts led to the formulation of two further hypotheses: interference and the hypothesis of unique items. The former regards the tendency of the translation to bear distinctive traces of the source language; the latter maintains the presence, in translated texts, of less unique items than might be found in original texts produced in the same target language, defining “unique items” as those elements that are “untranslatable” (Zanettin, 2013, p. 23), such as culture-specific elements. In a similar contribution from a different perspective, Chesterman (2004, p. 39) divides TU hypotheses according to the vision of translation as a process or as a product, using “S-Universals” to refer those that characterizes the translation process and are evident from the comparison between source and target text, and “T-Universals” to denote those that arise from the comparison of translations and comparable non-translated texts. Chesterman (2004) situates simplification in the second group.

As for the research on simplification, many authors focus on the hypothesis contending that translations tend to be simpler than original texts. Previous studies have considered and assessed simplification of translated texts from different perspectives, trying to determine specific indicators for the purpose of operationalization. Departing from a lexical perspective, Laviosa (1998a) suggests considering lexical density (or the relationship between lexical and total words of a corpus) and lexical variety (the relationship between the total number of types and tokens of a corpus), which in a translation should be lower than in an original text. Through the same prism, Blum and Levenston (1978, p. 399) define simplification as “the process and/or result of making do with less words” and propose sIX principles under which this kind of simplification would operate:

- Use of hyperonyms to resolve lexical inequivalences.

- Approximation of concepts expressed in the source text.

- Use of common and familiar synonyms.

- Considering the existence, in the target language, of a unique translation-equivalent for each source word.

- Use of circumlocutions instead of precise equivalents to high-level words and expressions.

- Use of paraphrasis instead of conceptual high-level words, particularly translating specific terminology and in cases of cultural gaps between the source and the target languages.

Considering syntactic simplification, Del Rey Quesada (2015) highlights the substitution of non-finite structures with finite ones, Vanderauwera (1985, as cited in Laviosa, 1998b: 288) adds the suppression of suspending periods, while Redelinghuys and Kruger (2015) operationalize simplification by means of readability indexes based on the length of sentences and words.

From a stylistic perspective, translated texts seem to split large sentences and expressions, replace elaborate phraseology with shorter collocations and avoid repetition (Vanderauwera, 1985, as cited in Laviosa, 1998b: 289). The tendency to avoid repetition, originally proposed as a separate TU hypothesis (Baker, 1993), can also be “regarded an aspect of stylistic simplification” (Laviosa, 1998b, p. 289). Further, Toury (1991, p. 188) affirms that this is “one of the most persistent, unbending norms in translation in all languages studied so far”.

Among the indicators of stylistic simplification, Laviosa (2002) adds minor sentence length, a characteristic of translated texts confirmed by Xiao and Yue (2009), who relate it to the stronger punctuation identified in translation by Malmkjaer (1997) that, in their opinion (Xiao and Yue, 2009), is due to the translator’s tendency to split longer and more complex original sentences. Finally, taking style into account from a reception-oriented view, Puurtinen (2003, p. 395) suggests considering the “speakability” of a text as an indicator of a simpler style, defining this as “the ease of reading aloud”.

Other studies analyze corpora of translated texts to corroborate or refute the hypothesis of simplification. Among these, Laviosa (1997, 1998a) and Xiao (2010) corroborate the hypothesis by analyzing a set of translations from English into Italian and into Chinese, respectively, while Corpas Pastor et al. (2008) examine a set of English-Spanish translations with the same aim, but obtaining the opposite results as the original texts appear to be simpler than the corresponding translations.

The majority of previous studies involve a comparison between translated and original texts using a corpus-based methodology. As explained in the next section, corpus-based methodology is particularly fruitful when combined with the new perspectives adopted by translation studies, which promotes the exponential increase of CBTS.

2.2. Corpus-based methodology and previous studies

Corpus-based studies originated in the 1950s, but were first applied to translation studies only in the late 1970s, thanks to improvements in computer science (Mattioli, 2018). However, it was in the 1990s that corpus-based methodology becomes a common method in translation studies. This period marks a deep change in translation studies adopting a new descriptive perspective under the strong influence of the polysystem theory proposed by Even-Zohar (1990) and the hypothesis of the TU advanced by Mona Baker (1993). The productivity of corpus-based methods for the description and analysis of language (Sánchez Pérez, 1995) fostered their application to translation studies in an attempt to examine and describe the behavior of translated language in relation to the new theories.

Among the most frequent objects of study of CBTS, in fact, are topics related to TU. The results obtained by using an electronic method are particularly useful for the comparison of originals and translations as well as to describe the features of translated texts in order to corroborate or refute the TU hypotheses. As a consequence, following Baker’s (1993) proposal that began the debate, the number of CBTS related to the topic has increased exponentially (Kenny, 2001; Laviosa, 2002; Puurtinen, 2003; Pápai, 2004; Mauranen, 2004). The review of the previous research on simplification (Laviosa, 1997; 1998a; Corpas Pastor et al., 2008; Xiao, 2010) presented in the former section demonstrates that corpus-based methodology has been successfully used also for studies related to the object of the present research.

CBTS are useful to identify the regularities of the analyzed language or linguistic variety (Tognini-Bonelli, 2001); to study the translation process, its products, and functions (Xiao and Yue 2009); and to distinguish collocations, specific terminology and syntactic, grammatical and stylistic structures (Gandin, 2009). A further advantage of corpus-based methodology is its electronic nature that allows for the analysis of large amounts of authentic data in a relative short time (Gandin, 2009) and, consequently, facilitates greater representativeness and exhaustion without discarding any of the occurrences present in a corpus (Rojo, 2002). Moreover, Gandin (2009) underlines that the corpus-based methodology seems to be particularly appropriate for the analysis of a specialized language. Actually, corpus-based methods have been adopted in a number of studies about translation of specialized discourse in the last years. Within the field of legal language, Sánchez Ramos (2019) builds a parallel, aligned corpus of English and Spanish judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union to be used as a tool to resolve typical legal translation problems and as a reference for further legal translation, Hernández García (2021) adopts a corpus-based method to contrast the terminology of the “term and conditions” of social networks in English and Spanish, whereas Seghiri and Arce Romeral (2021) analyze a corpus of Irish and Spanish housing purchase and sale agreements. Focusing on different types of discourse, Da Cunha and Montané (2020) examine a corpus of Spanish administrative texts drafted by laymen and addressed to the Public Administration and Chen at al. (2019) analyze the political discourse from a stylistic perspective in a corpus of Hillary Clinton’s and Donald Trumps’ campaign speeches during the general election. Considering more specific types of discourse, Durán-Muñoz (2019) examines the adventure tourism discourse in English and describes the extensive use of adjectives in respect to the general language whereas Ortego Antón (2019) analyzes the very specialized discourse of the agri-food sector by realizing a contrastive study of the dried-meats labels in English and Spanish. As for the corpus-based research about academic language, Yang (2018) analyzes the use of modal verbs in Chines learners’ academic texts drafted in English, Un-udom and Un-udom (2020) investigate the use of reporting verbs in applied linguistics papers and Dang (2022) examines the vocabulary used in conference presentations.

Despite its extensive use for the analysis of the specialized discourse, as any other method, corpus-based methodology has its own limitations. One of the most important disadvantages seems to be the influence of the compilation criteria on the research results. Rojo (2002) highlights the difficulties related to the retrieval, collection and compilation of the material, whereas Malmkjaer (1998) points out the impossibility of generalizing the results to translations as a whole when the analyzed parallel corpus includes only one translation for each original text, suggesting including among the analyzed translations works realized by different translators. However, this solution is hindered by the difficult access to different translations of the same original text into the same language and their limited availability, particularly for non-literary texts (Laviosa, 2002). Kruger and Rooy (2012) proposes a different, apparently more feasible solution, instead: the addition of non-prototypical translations, including the ones realized by non-professional translators or inverse translations to the prototypical translations usually collected in a corpus of a great range. Beyond the limitations related to the compilation, Mattioli (2014) points to the limited number of features that can be analyzed, whereas Rojo (2002) considers the great amount of data resulting from the analysis which complicates the process of retrieval and interpretation of the relevant results. In fact, the interpretation of the results obtained from a corpus-based study is an intensively debated topic. Baker (2004, p. 184) insists in the necessary researcher’ interpretative task as “the computer can help us locate features —textual features—but it cannot explain them.” It seems generally accepted that such interpretative task can be accomplished successfully only by combining corpus-based methods with different, qualitative approaches which allow for relating evidences to the context and draw conclusions which actually impact the discipline and go beyond the analysis of linguistic data from a mere lexical, syntactic and semantic perspective (Olohan, 2002). Additionally, De Sutter and Lefer (2019) highlight the need for such a combination to take into account the several factors involved in the textual production and translation, pointing to the essential role of interdisciplinarity to broaden the perspective of the study.

The usefulness of corpus-based methodology in previous studies, its advantages, and suitability when considering a specific discourse seem to make it the proper method through which to achieve the objectives of this study. It allows for a description of the analyzed types of discourse (non-specific and academic) as per their syntactic and stylistic characteristics related to simplification, departing from a large and varied (and hence representative) sample. Its disadvantages could be limited by following a specific compilation process that considers both qualitative and quantitative representativeness, and by choosing the elements to be analyzed according to the possibilities offered by the currently available corpus tools.

3. Methodological frame

3.1. Objectives, hypotheses, and research questions

The main goal of this research is identifying and describing similarities and differences across corpora of English original and translated texts representing non-specialized and specialized academic discourse, in terms of syntactic and stylistic simplification. Additionally, examining corpora including texts of different types of discourse (non-specialized and specialized academic) and natures (original and translated), the study intends to assess the influence of both variables in the use of simplification. This multi-discourse approach aims to contribute to the knowledge of the simplification hypothesis as well as to broaden the focus of CBTS, usually developed considering a single perspective. The results will provide useful information to deepen the current knowledge about the tendency to simplification in both, translated and academic texts, and about the relationship between simplification and the degree of specificity of the discourse. Even if investigating the translation process is beyond the scope of this paper, the outcomes will allow for developing further studies taking into account the decision-making process and the cross-linguistic and cross-cultural constrains which affect translators’ choices, by combining corpus-based methods with qualitative methodologies. These general objectives can be divided into three more specific goals:

- Determining specific indicators to operationalize syntactic and stylistic simplification

- Identifying such indicators in each corpus under analysis

- Comparing the analysis results obtained from among the different corpora examined

According to the TU hypothesis of simplification, this study departs from the premise that translations are simpler than original texts. Consequently, the initial hypothesis of the study posits that instances of simplification can be identified in translated texts from both non-specialized and specialized academic discourse.

To achieve the determined objectives and corroborate the hypothesis, this research is guided by the following research questions:

- Which features related to syntactic and stylistic simplification can be identified in original and translated texts representing non-specialized and specialized academic discourse?

- Which similarities and differences are present in the non-specialized and specialized academic texts examined in terms of syntactic and stylistic simplification?

- Is the tendency towards simplification more closely related to the nature (original/translated) or to the type of discourse (non-specialized/specialized academic) of the analyzed texts?

3.2. Analyzed Corpora

The analysis focuses on the English language. The analyzed archive of corpora is made up of four different sets of texts published in a span of 20 years between 2000 and 2019:

- Original non-specialized texts (NS_OT): 33,129 types and 1,012,879 tokens

- Translated non-specialized texts (NS_TT): 32,935 types and 1,057,200 tokens

- Original academic texts (AD_OT): 35,477 types and 1,189,596 tokens

- Translated academic texts (AD_TT): 36,375 types and 1,294,770 tokens

The corpora were compiled according to five criteria: quantitative representativeness, including at least one million tokens in each corpus; publication date; inclusion of complete written texts; textual, disciplinary, and linguistic variety that contributes to a greater qualitative representativeness, selecting for each corpus texts from five different academic or general fields and, in the case of translations, proceeding from at least eight unrelated source languages; balance among corpora, in terms of number of tokens and distribution of texts among the different types and fields.

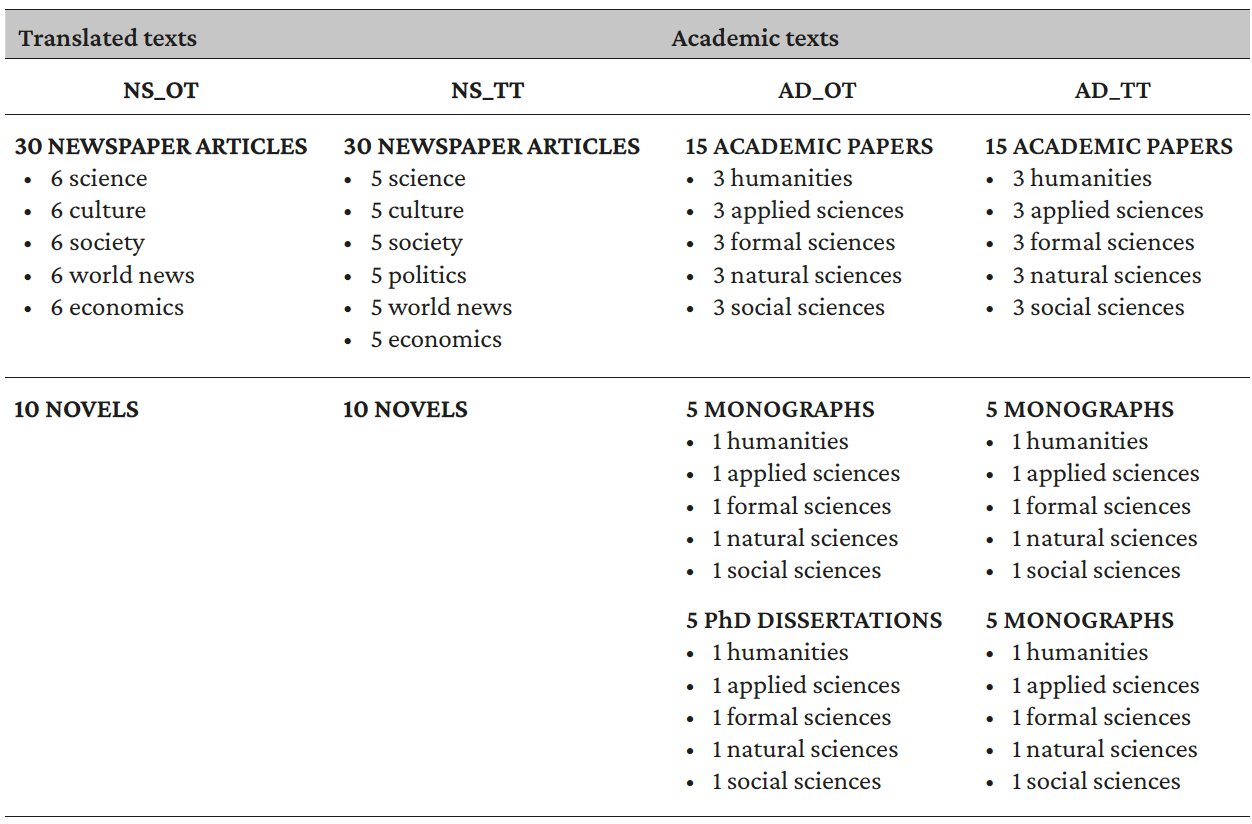

As a result, non-specialized discourse is represented by two comparable corpora: NS_OT (original non-specialized texts) and NS_TT (translated non-specialized texts). Each includes 40 texts of two different genres: 30 newspaper articles and ten novels. The newspaper articles represent five different fields (science, culture, society/politics, economics and world news) in an equal distribution and were selected from international newspapers of different countries. The novels, written by multiple, internationally recognized authors from different countries, represent different topics and subgenres (romantic novels, science fiction, thrillers, etc.). The newspaper articles and the novels included in the translated corpus of non-specialized texts (NS_TT) proceed from nine original languages: French, German, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Portuguese, Slovenian, Spanish and Swedish.

The academic texts are represented by the two comparable corpora: AD_OT (original academic texts) and AD_TT (translated academic texts). Each is composed of 25 texts of different types equally distributed across five academic fields (humanities, applied sciences, formal sciences, natural sciences and social sciences). AD_OT consists of 15 academic papers, five textbooks and five PhD dissertations, equally distributed among the selected fields. AD_TT includes 15 academic papers and ten monographs, also equally distributed among the examined fields, but no PhD dissertations. PhDs are not usually translated, hence they were substituted by an equal number of translated monographs. However, this choice does not affect the comparability between the analyzed corpora. Actually, dissertations are unanimously recognized as a type of academic texts produced within the academic community for research-development process (Pramoolslook, 2009) and, specifically, monographs dissertations, the most frequent forms of dissertations, “adhere closely to the academic genres of the book” (Paré 2017, p. 411). In this sense, dissertations have been often compared to academic books as for their “book-length” (Paré 2017, p. 408) and their level of metatext at chapter distance which, according to Bunton (1999), it is distinctive of both. As for the features which distinguish theses and dissertations from other types of research writing (Paltridge, 2002), they seem to entail primarily external criteria —e.g., communicative purpose, audience, and the requirements to be met (Paltridge, 2002; Pramoolslook, 2009)— or textual structure (Pramoolslook, 2009) but no previous references have been found about formal divergences involving syntax and style. As the objective of the present study is examining simplification from a stylistic and syntactic perspective and only at sentence level, regardless the macrostructure of the texts, PhD dissertations and monographs can be fruitfully compared. Similarly, the two corpora in which they are included are comparable for presenting all the characteristics used to define comparability: representing similar domains and varieties of language, having been produced in the same time span and presenting a comparable length (Baker, 1995). The translated texts collected in AD_TT derive from 11 original languages: Chinese, Czech, Danish, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Korean, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. For the analysis, the index, abstracts in languages other than English, the list of references, and all images were eliminated.

The distribution of the texts among the corpora, the different areas or academic fields included, and the analyzed language pairs are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of the texts among the different corpora

During the compilation process, a balanced number of tokens was preferred to an equal number of texts, which is why non-specialized corpora entail more (shorter) texts than academic ones. This allowed for the compilation of four sets of texts that include at least one million tokens each. Within each type of discourse (academic or non-specialized), translated and original corpora present a balanced internal distribution, both for the types and the fields of the included texts. Moreover, an effort was made to select texts from different topics within each examined field.

Also, some of the source languages of the translated texts differ between the non-specialized and academic corpora. This study departs from the basic premise of the TU hypothesis: TU are inherent to any translated text “simply by virtue of being translations” (Xiao, 2010, p. 8), regardless of the language pair. For this reason, Kruger and Rooy (2012, p. 43) insist that, to generalize the results about the feature of translation, a corpus should be “as inclusively as possible”. Further, considering Chesterman’s (2004) distinction, simplification, as a T-Universal, is a characteristic of the target text, hence a difference that emerges from the comparison of translation with a comparable corpus of non-translated texts. As a consequence, the analysis realized in the present study focuses on comparable (not parallel) corpora, considering only the target texts translated into English, regardless of their source languages. According to authors such as Mauranen and Ventola (1996) or Bennet (2007), academic texts of the same language present specific and identifiable linguistic features, hence, a corpus including exclusively English translations allows for analyzing the linguistic features related to stylistic and syntactic simplification which characterized English AD. However, considering the still debated status of such premises, further studies are encouraged to assess any possible difference between different language pairs, departing from the present research.

3.3. Methodology

A corpus-based methodology was chosen for the research, as it permits the comparison of different sets of texts through systematic analyses replicable for each corpus. This methodology consists of three main steps, related respectively to the three specific objectives of this study:

- Determination of specific indicators to operationalize syntactic and stylistic simplification

- Identification of the determined indicators in each corpus under analysis

- Comparison of the results obtained from the four analyzed corpora

Step 1: Determination of specific indicators to operationalize syntactic and stylistic simplification

According to the previous literature, syntactic simplification seems to be related to the use of simpler clausal relations, specifically the substitution of non-finite structures with finite ones (Del Rey Quesada 2015) and the tendency to use paratactic relations or independent unrelated clauses instead of subordinate ones (Biber and Gray, 2010). In contrast, stylistic simplification is usually related to lesser fluency, a tendency to avoid repetitions and complex collocations, less lexical variety, a preference for shorter sentences, and a lower lexical density (Laviosa, 1998a) that indicates an inferior “informational load” (Xiao and Yue, 2009, p. 253). Taking into consideration all the indicators related to both kinds of simplification, the linguistic features denoting simpler texts considered in this study are:

- Lexical variety

- Lexical density

- Mean sentence length

- Presence of hypotactic structures

- Presence of non-finite clauses

Step 2: Identification of the determined indicators in each corpus under analysis

Once the linguistic features to be analyzed in each corpus are determined, each is assessed through a specific methodology and the corresponding appropriate tools. With this aim, two different programs are used in a complementary manner: WordSmith Tool version 7.0, developed by Scott (2017), and the license-free software AntConc (Anthony, 2014).

Mean sentence length and lexical variety, measured using the STTR (standardized types/token ratio) formula1, are calculated automatically by WordSmith Tool (Scott, 2017), whereas lexical density is obtained by dividing the total number of lexical words by the total number of tokens of the corpus, according to Stubbs’s (1986) proposal. As the adopted corpus-based methodology does not allow for detecting the lexical or functional nature of those items which can play both functions according to the context (e.g., “do” can be a lexical or an auxiliary verb, thus a lexical or a functional item), they are manually separated from the wordlist and not considered in the calculation of lexical density. Manual analysis offers very reliable and detailed results; however, it is extremely time-consuming. Consequently, only the items with a frequency equal to or greater than 50 were revised, considering that their high number of occurrences could have influenced the results.

Concerning the subordinate clauses, they are usually introduced by a conjunction or a relative pronoun; when they do not include an introductory item, they are usually non-finite clauses. As non-finite clauses are one of the determined indicators that will be identified and examined separately in the next phase, here only the subordinate clauses introduced by a conjunction or a relative pronoun are considered. First, an exhaustive list of conjunctions (Several Authors, Mt San Jacinto College, 2020) is adopted and each one sought in the concordance list, allowing for an observation of their context and for the selection of cases in which they are actually used as conjunctions (avoiding those in which they could be prepositions or adverbs). For each conjunction, the number of occurrences is registered, and finally, the occurrences of each conjunction are added. As each conjunction introduces a secondary clause, the total number of conjunctions in the corpus also represents the total number of secondary clauses. An exception has been done with the conjunction “that”. Actually, “that” can play a number of different functions within the sentence (i.e. determiner, demonstrative pronoun, relative pronoun and conjunction to introduce that-clauses) which cannot be distinguished properly with the adopted corpus-based method. As a result, “that” was discarded from the list of subordinate conjunctions and, in this step, it was considered uniquely as a relative pronoun.

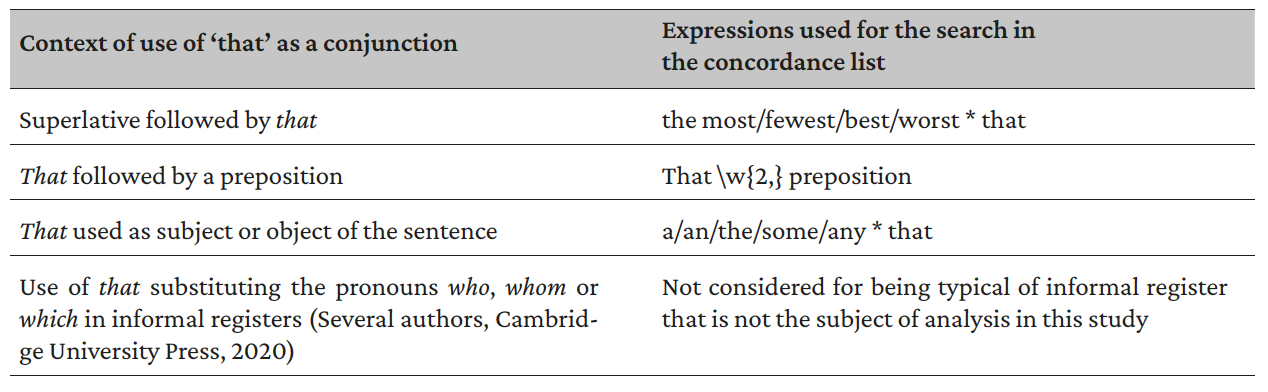

Regarding the subordinate clauses introduced by a relative pronoun, the same procedure is used: each pronoun included in the adopted list (Several Authors, Mt San Jacinto College, 2020) is searched for in the concordance list and, among the results, only those used to introduce a clause are selected. Here, special attention is given to the pronoun “that,” a polysemic word that can play many different roles. According to the Cambridge Dictionary online (Several Authors, Cambridge University Press, 2020), “that” is used as a pronoun introducing a relative clause in the following four specific contexts:

- Superlative followed by that (e.g., The best book that I ever read)

- That followed by a preposition (e.g., The person that you are speaking about)

- That used as subject or object of the sentence (e.g., The toy that I bought for the baby)

- Use of that substituting the pronouns who, whom or which in informal registers (We saw the man that [instead of who] works with your father)

Consequently, some wildcards or regular expressions are used to identify and select only such cases. The expressions used to identify the contexts in which “that” is used as a relative pronoun are presented in Table 2 (where the wildcard * means “any character zero or more times” and the regular expression \w{2,} “two or more words”).

Table 2. Expressions used to identify the occurrences in which “that” is used as pronoun to introduce a relative clause

As in some of the examined conjunctions, various prepositions considered in the structures “that followed by a preposition” can indicate more than one grammatical function and can be used as conjunction, preposition or adverb according to the context (e.g., once, than, yet). In these cases, the search is further detailed in order to limit the results only to conjunctions. For example, consideration is given to the punctuation by which they are accompanied (as in the case of though normally used as a conjunction meaning although or even though whether located between two commas or before the final full stop), their position within the sentence (for example, so is usually employed as a conjunction at the beginning of the sentence, but as an adverb in the middle of a phrase), or the preceding or following elements (e.g., than is a preposition when followed by a noun and a conjunction when followed by a verb).

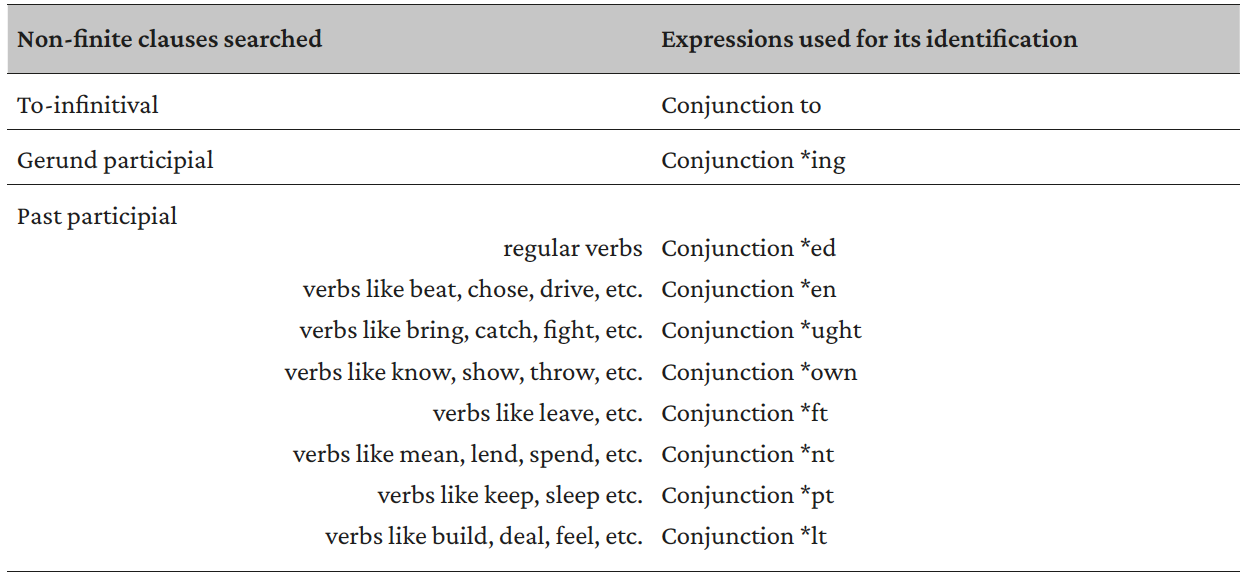

The final indicators identified in the corpus are non-finite clauses. To detect them, firstly, all the possible types of non-finite clauses are considered. According to Huddleston and Pullum (2005), in English four types of non-finite constructions exist: to-infinitival, the preposition to followed by the base form of the verb (to play); bare infinitival, or zero infinitive, that is, the use of the base form alone (play); gerund participial, using the -ing form of the verb (playing); past-participial, including the participle tense of the verb (played). The Cambridge Dictionary online (Several Authors, Cambridge University Press 2020) adds that the bare infinitival is used after modal verbs, as in I must work, and after the verbs let, make and help, as in let’s help your mother. As a consequence, these cases are not proper non-finite clauses, as they include finite verbs (modal or not), hence they are not of interest to this study and are not considered. As for the other three types of non-finite structures, each is sought in the concordance list preceded by each one of the conjunctions included in the considered list (Several Authors, Mt San Jacinto College 2020), using wildcards in order to include any verb. However, whereas the infinitive and the gerundive forms do not change depending on the verb, participle versions assume different forms in case of irregular verbs, changing according to the paradigm. Following an in-depth observation of the list of paradigms, some regular patterns are identified and added to the regular expressions used in the search, in order to include as many verbs as possible in the study. As a result, the complete range of expressions used to identify non-finite clauses is displayed in Table 3 (where the wildcard * means “any element”).

Step 3: Comparison of the results obtained from the four analyzed corpora

Once all the indicators are identified and examined in each corpus, the results are compared, considering any possible combinations of the two analyzed discourses (academic and non-specialized) and the nature of the texts (translated or original). As a result, four different comparisons are realized:

- Original non-specialized texts vs. Original academic texts (NS_OT vs. AD_OT)

- Translated non-specialized texts vs. Translated academic texts (NS_TT vs. AD_TT)

- Original non-specialized texts vs. Translated non-specialized texts (NS_OT vs. NS_TT)

- Original academic texts vs. Translated academic texts (AD_OT vs. AD_TT)

Table 3. Expressions used to identify the non-finite clauses in each analyzed corpus

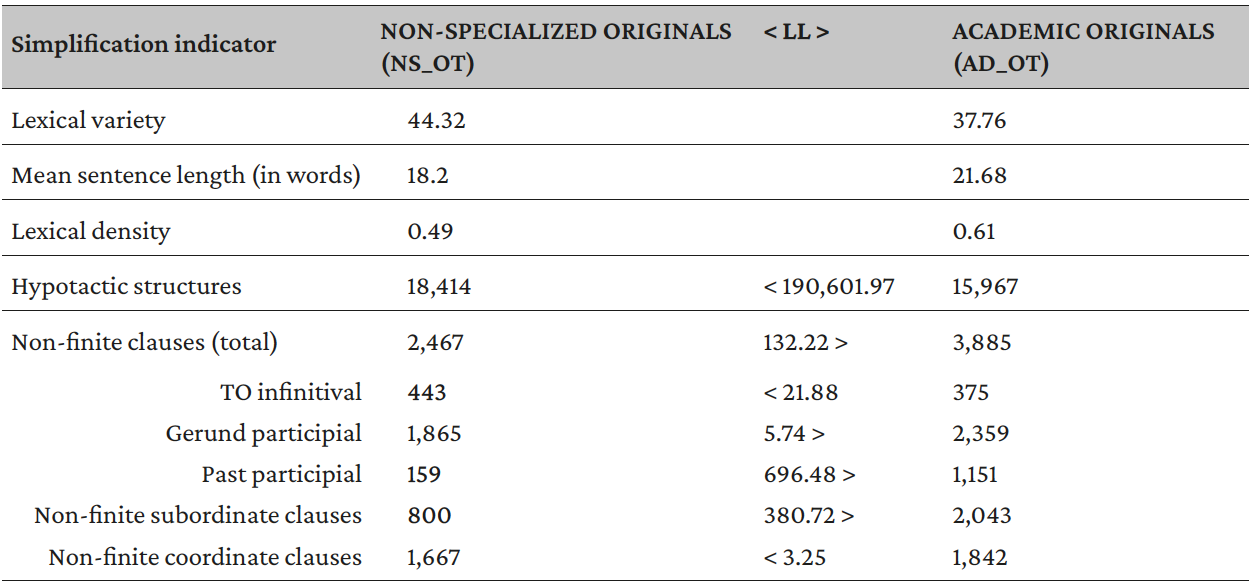

Table 4. Expressions used to identify the non-finite clauses in each analyzed corpus

Although each corpus includes a similar quantity of tokens (between one million and 1,300,000), the statistical significance is calculated to compare across the different corpora those indicators which values do not result from a statistical exam but are obtained by adding specific items: hypotactic structures and non-finite clauses. To do so, the log likelihood (LL) statistical test is used, calculated using the wizard provided by the UCREL Research Group of Lancaster University2. The accepted p value is set at 0.001 and, consequently, only results equal to or higher than the threshold of 6.63 are considered significant. In the tables of the next section, the obtained LL value is shown along with the results expressed in number of occurrences, followed or preceded by a small arrow (< or >) indicating which of the two compared corpora presents an overuse of the examined indicator in respect to the other.

3.4. Results and discussion

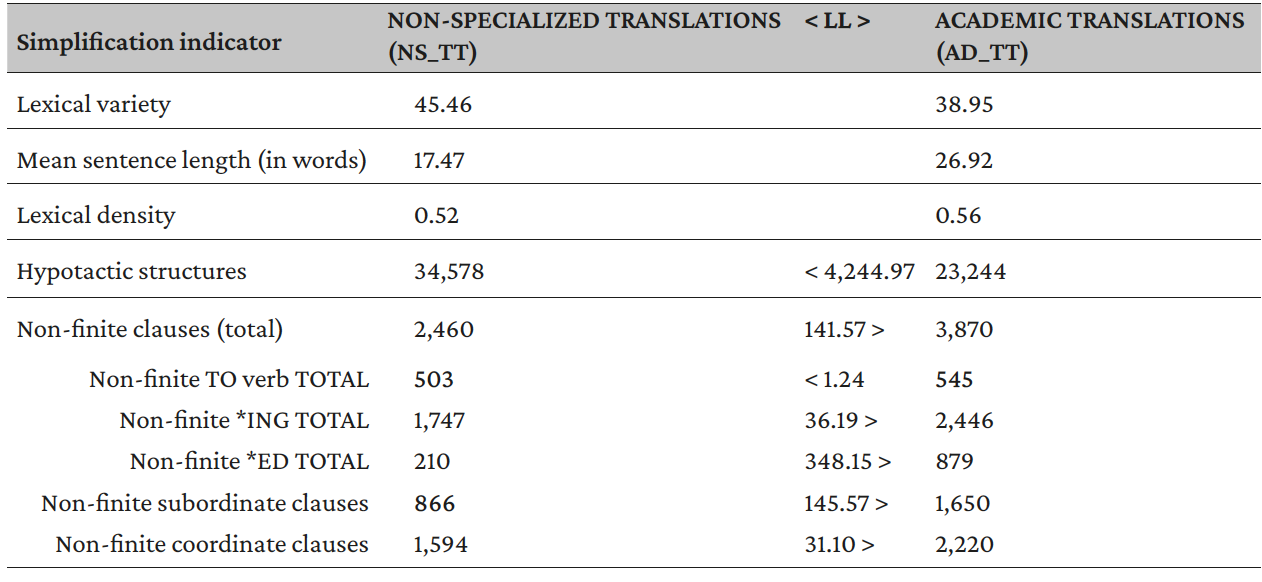

The first comparison realized is that between the two corpora of original texts (NS_OT and AD_OT) and the two corpora of translated texts (NS_TT and AD_TT). The results show that both types of discourse present some of the indicators of simplification considered in the study and thus that simplification affects both types of discourse. Also, the outcomes contribute to the description of the simplification-related features of AD vis-à-vis non-specialized discourse. In both cases, AD presents a lower degree of lexical variety, greater lexical density, longer sentences, fewer hypotactic structures, and a greater quantity of non-finite clauses than general language (see Tables 4 and 5).

Table 5. Results of the comparison between translated non-specialized texts and translated academic texts (NS_TT vs. AD_TT)

These features characterize AD in contrast to non-specialized language in terms of syntactic and stylistic simplification in both original and translated texts. The presence of the same indicators in both original and translated texts suggests that the tendency towards simplification depends more on the type of discourse than on the original or translated nature of the texts. Such conclusions are further underpinned by the data obtained from the comparison between originals and translations of each type of discourse (NS_OT vs. NS_TT and AD_OT vs. AD_TT, presented in Tables 6 and 7 respectively).

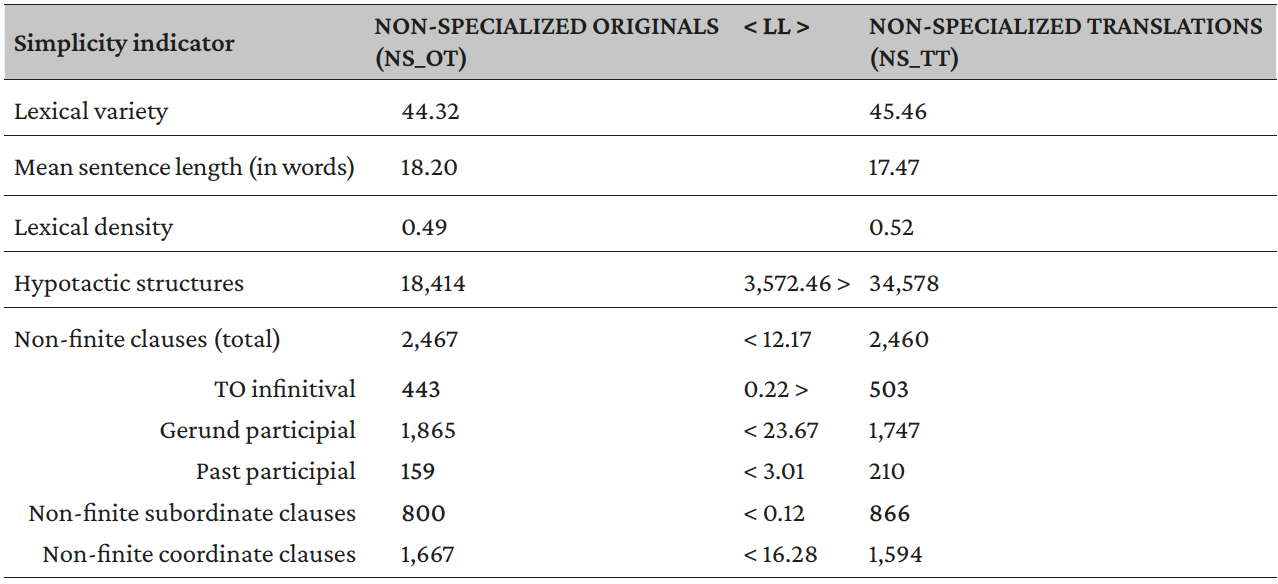

As for non-specialized discourse, the comparison between translated and original texts presented in Table 6 below does not show considerable differences. In both corpora, lexical variety (44.32 in NS_OT and 45.46 in NS_TT), lexical density (0.49 and 0.52 respectively), and mean sentence length (18.20 and 17.47 respectively) present very similar values. Additionally, the greater use of non-finite structures in original texts than in translations (LL: 12.17) is due only to the difference between gerund participial structures (i.e., -ing form) (LL: 23.67) and coordinate clauses (LL: 16.28), the unique ones that are statistically significant. As a result, the only analyzed feature that clearly differs between translated and original non-specialized texts is the greater quantity of hypotactic structures in translations that makes translated texts more complex than originals. These outputs, as well as describing the characteristics of the corpora of non-specialized texts examined in this study, also refute the TU hypothesis of simplification and the initial hypothesis of the present study.

Table 6. Results of the comparison between original and translated non-specialized texts (NS_OT vs. NS_TT)

Table 7. Results of the comparison between original and translated academic texts (AD_OT vs. AD_TT)

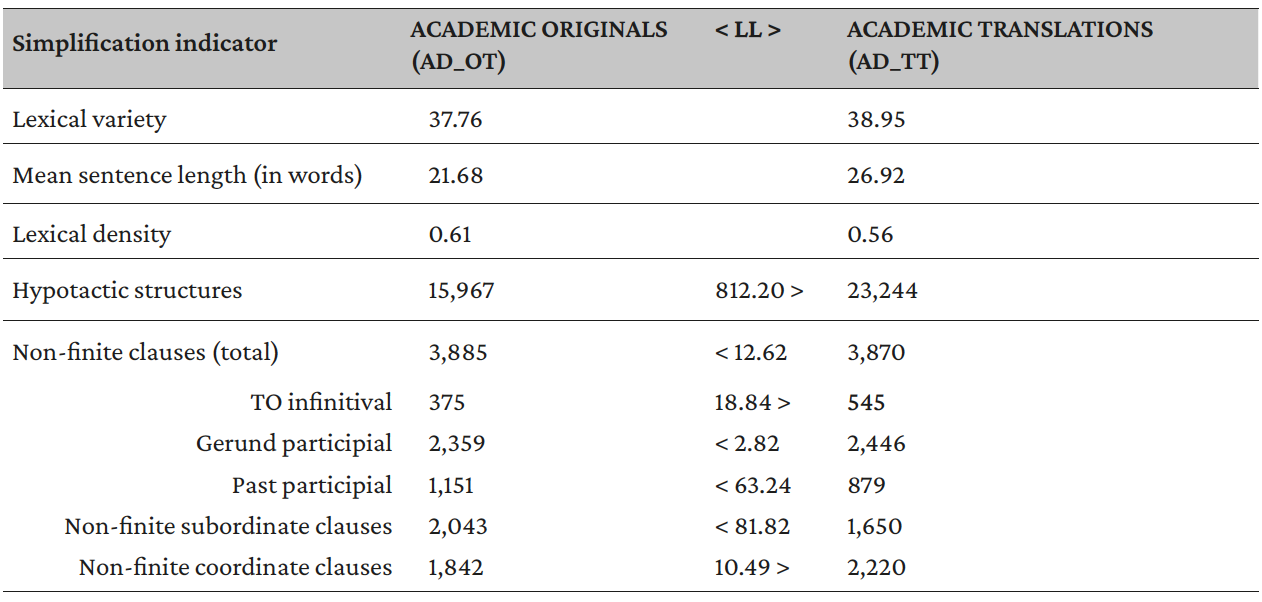

In the corpora representing AD, the difference between translated and original texts is greater than in non-specialized discourse. This appears in almost all the examined indicators, with the exception of lexical density, which does not show any substantial difference between the two corpora (0.56 and 0.61 respectively). In this case, translations seem to be simpler than original texts only in lower quantity of non-finite clauses (LL: 12.62), whereas they are more complex in terms of longer sentences (26.92 vs. 21.68 words), lexical variety (37.76 instead of 38.95) and quantity of hypotactic structures (LL: 812.20). These outcomes are detailed in Table 7.

These results indicate that also within AD, translations seem to be more complex than the original, showing greater values in three out of four simplification indicators. Again, the initial hypothesis of the study is refuted as well as the TU hypothesis of simplification, which seems to be refuted in this particular case (or at least, to be valid only for certain specific indicators).

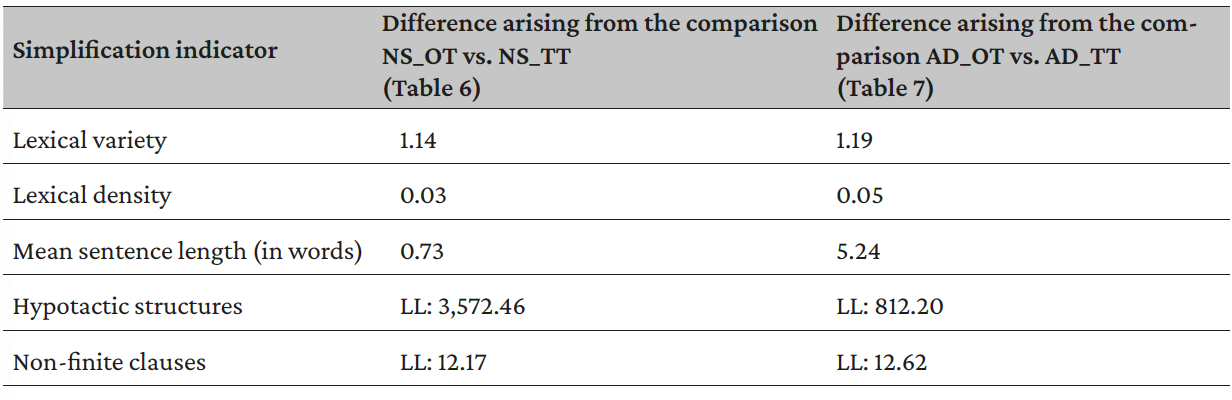

Furthermore, the data show that the difference between the original and the translated corpus of AD (Table 7) is substantially greater than that arising from the comparison of non-specialized texts (Table 6) with respect to almost all the considered simplification indicators.

The dissimilar degrees of difference shown by translations and originals of each analyzed type of discourse (non-specialized and academic) shown in Table 8 and the different indicators of simplification characterizing non-specific and academic translated texts (NS_TT vs. AD_TT, Table 5) argue that a tendency towards simplicity is influenced more greatly by the type of discourse than by the original or translated nature of the texts, supporting the conclusions reached in previous comparisons (NS_OT vs. AD_OT and NS_TT vs. NS_TT; see Tables 4 and 5 respectively).

Table 8. Difference arising from the comparison between original and translated texts of each type of discourse (non-specialized and academic)

4. Final remarks

This paper compared English original and translated texts representing non-specialized and specialized academic discourse, to identify similarities and differences between the two types of discourse in terms of syntactic and stylistic simplification. The study follows an original multi-discourse analysis approach that enriches the research on simplification and broadens the usual focus of CBTS, introducing two different variables in the study of simplification: non-specialized/academic specialized discourse and the original/translated nature of the texts. Such multiple perspectives facilitated examination of the influence of each variable on simplification and assessing which of the two has greater influence.

With these goals in mind, the study departed from the initial hypothesis maintaining that instances of simplification can be identified in translated texts of both non-specialized and specialized academic discourse. In order to corroborate or refute such a hypothesis, four comparable corpora representing academic and non-specialized texts in original and translated versions were compiled and then analyzed according to a three-step corpus-based methodology. First, departing from previous studies, five indicators were selected to operationalize syntactic and stylistic simplification: lexical variety, lexical density, mean sentence length, the presence of hypotactic structures and the presence of non-finite clauses. Second, each indicator was sought separately in each set of texts. Finally, the results were compared across the four sets of texts paired in all possible combinations.

The outcomes refute the initial hypothesis as well as the TU hypothesis of simplification, as in both types of discourse original texts were found to be simpler than translations. As for comparison across the two examined types of discourse, instances of simplification were identified in both non-specialized texts and AD. However, each type of discourse presents different simplification indicators, with non-specialized texts presenting fewer non-finite clauses, lower lexical density and shorter sentences, and AD containing a lower degree of lexical variety and fewer hypotactic structures. Such results added to the outcomes obtained from the comparisons between the original and translated text of each type of discourse (non-specialized and academic) support the conclusion that simplification, in this study, seems to depend more on the type of discourse than on the original or translated nature of the texts. The data obtained in the study also represent a point of departure for further research which combines corpus-based and more qualitative methodologies to go beyond the perspective of translation as a product assumed in this study and deepen the translation process, considering translators’ choices and the linguistic and social constrains which influence them.

Additionally, the results contribute to characterizing stylistic and syntactic simplification more accurately in AD translated texts with respect to translations of non-specialized texts. In future research could be investigated the influence of different language pairs on the results, and hence on the TU hypothesis of simplification.

However, the main asset of the study may be its original focus incorporating a multi-discourse analysis in the CBTS on simplification. Such an approach broadens the reach of CBTS and amplifies the study of the traditional topics of the discipline, proposing new methods and prisms with which to investigate them. From an interdisciplinary perspective, this study encourages further comparisons between translations of different types of texts, expanding translation-specific topics (including simplification) to specialized languages. Finally, from a methodological perspective, the research aims to offer a replicable method to assess the simplicity or complexity of a corpus of texts. This method can be used fruitfully to analyze other sets of texts from different genres, contexts and of different types, or as an inspiration to design further similar corpus-based methodologies to identify semi-automatically different textual features.

References

Anthony, L. (2014). AntConc (Version 3.4.1) (Computer Software). Waseda University. http://www.laurenceanthony.net/

Baker, M. (1993). Corpus Linguistics and Translation Studies: Implications and Applications. In M. Baker, G. Francis, & E. Tognini-Bonelli (Eds.). Text and technology: In Honour of John Sinclair (pp. 233-250). John Benjamins.

Baker, M. (1995). Corpora in translation studies: An overview and some suggestions for future research. Target 7(2), 223-243.

Baker, M. (2004). A corpus-based view of similarity and difference in translation. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 9(2), 167-193.

Bennet, K. (2007). Epistemicide! The tale of a predatory discourse. The Translator 13(2), 151-169.

Biber, D., and Gray, B. (2010). Challenging stereotypes about academic writing: Complexity, elaboration, explicitness. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 9(1), 2-20.

Biber, D., and Gray, B. (2019). Are law reports an ‘agile’ or an ‘uptight’ register?: Tracking patterns of historical change in the use of colloquial and complexity features. In T. Fanego, and p. Rodríguez-Puente (Eds.). Corpus-based Research on Variation in English Legal Discourse (pp. 149-169). John Benjamins.

Blum, S., and Levenston, E. A. (1978). Universals of lexical simplification. Language learning, 28(2), 399-415.

Bunton, D. (1999). The use of higher level metatext in PhD theses. English for Specific Purposes, 18(Supplement 1), S41-S56.

Cabré, M. T. (2002). Textos especializados y unidades de conocimiento: metodología y tipologización. In J. García Palacios, and M. T. Fuentes (Eds.). Texto, terminología y traducción (pp. 15-36). Almar.

Cabré, M. T., Da Cunha, I., Sanjuan, E., Torres-Moreno, J. M., and Vivaldi, J. (2010). Automatic specialized vs. non-specialized texts differentiation: a first approach. Technological innovation in the teaching and processing of LSP, hal-02556652. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02556652

Chen, X., Yan, Y., and Hu, J. (2019). A corpus-based study of Hillary Clinton’s and Donald Trump’s linguistic styles. International Journal of English Linguistics, 9(3), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v9n3p13

Chesterman, A. (2004). Beyond the particular. In A. Mauranen, and p. Kujamäki (Eds.). Translation universals: Do they exist? (pp. 33-49). John Benjamins.

Corpas Pastor, G., Mitkov, R., Afzal, N., and Pekar, V. (2008). Translation universals: do they exist? A corpus-based NLP study of convergence and simplification. In MT at Work. Proceedings of the Eighth Conference of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas (pp. 75-81). Association for Machine Translation in the Americas.

Da Cunha, I., and Montané, M.A. (2020). A corpus-based analysis of textual genres in the administration domain. Discourse Studies, 22(1), 3-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445619887538

Dang, T.N.Y. (2022). A corpus-based study of vocabulary in conference presentations. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 59. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1475158522000649

Del Rey Quesada, S. (2015). Universales de la traducción e historia de la lengua: algunas reflexiones a propósito de las versiones castellanas de los Colloquia de Erasmo. Iberoromania, 81(1), 83-102.

De Sutter, G., and Lefer, M.A. (2019). On the need for a new research agenda for corpus-based translation studies: a multi-methodological, multifactorial and interdisciplinary approach. Perspectives, 28(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1611891

Dirección General de Educación Básica (1979). El lenguaje en la educación preescolar y ciclo preparatorio. Vasco-castellano. Centro de Publicaciones. Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

Durán-Muñoz, I. (2019). Adjectives and their keyness: a corpus-based analysis of tourism discourse in English. Corpora, 14(3), 351-378.

Even-Zohar, I. (1990). Introduction to Polysystem Studies. Poetics Today, 11(1), 1-6.

Flower, L. (1990). Negotiating Academic Discourse. In L. Flower, V. Stein, J. Ackerman, M. Kantz, K. McCormick, and W. C. Peck (Eds.). Reading-to-write: Exploring a cognitive and social process (pp. 222-252). Oxford University Press.

Gandin, S. (2009). Linguistica dei corpora e traduzione: definizioni, criteri di compilazione e implicazioni di ricerca dei corpora paralleli. AnnalSS, 5, 133-152.

Gotti, M. (2008). Investigating specialized discourse. Peter Lang.

Hernández García, V. (2021). Retos de traducción de las terms and conditions de las redes sociales: análisis jurídico y terminológico contrastivo inglés-español basado en corpus. Hikma 20(1), 125-156.

Huddleston, R., and Pullum, J. K. (2005). A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar. Cambridge University Press.

Kenny, D. (2001). Lexis and creativity in translation: A corpus-based approach. St. Jerome.

Kruger, H., and Rooy, B. (2012). Register and the features of translated language. Across Languages and Cultures, 13(1), 33-65.

Laviosa, S. (1997). How comparable can comparable corpora be? Target, 9(2), 289-319.

Laviosa, S. (1998a). Core Patterns of Lexical Use in a Comparable Corpus of English Narrative Prose. META: Translators’ Journal, 43(4), 557-570.

Laviosa, S. (1998b). Universals of Translation. In M. Baker, K. Malmkjaer, and G. Saldanha (Eds.). Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (pp. 288-291). Routledge.

Laviosa, S. (2002). Corpus-based translation studies: Theory, findings, applications. Rodopi.

Malmkjaer, K. (1997). Punctuation in Hans Christian Andersen’s stories and in their translations into English. In F. Poyato (Ed.). Nonverbal communication and translation: New perspectives and challenges in literature, interpretation and the media (pp. 151-162). John Benjamins.

Malmkjaer, K. (1998). Love thy neighbour: Will parallel corpora endear linguists to translators? Meta: Translators’ Journal, 43(4), 534-541.

Mattioli, V. (2014). Identificación y clasificación de culturemas y procedimientos traductores en el archivo de textos literarios LIT_ENIT_ES: un estudio de corpus (Master thesis). Universitat Jaume I. http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/112279/TFM_Mattioli_Virginia.pdf?sequence=4

Mattioli, V. (2018). Los extranjerismos como referentes culturales en la literatura traducida y la literatura de viajes: propuesta metodológica y análisis traductológico basado en corpus (PhD thesis). Universitat Jaume I. https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/587106/2019_Tesis_Mattioli_Virginia.pdf?sequence=1

Mauranen, A. (2004). Corpora, universals, and interference. In A. Mauranen and p. Kujamäki (Eds.). Translation universals: Do they exist? (pp. 65-82). John Benjamins.

Mauranen, A., and Ventola, E. (1996). Academic writing: Intercultural and textual issues. John Benjamins.

Olohan, M. (2002). Corpus linguistics and translation studies: Interaction and reaction. Linguistica Antverpiensia, 1, 419-429.

Ortego Antón, M. T. (2019). La terminología del sector agroalimentario (español-inglés) en los estudios contrastivos y de traducción especializada basados en corpus: los embutidos. Peter Lang.

Paltridge, B. (2002). Thesis and dissertation writing: an examination of published advice and actual practice. English for Specific Purposes, 21(2), 125-143.

Pápai, V. (2004). Explicitation: A universal of translated text? In A. Mauranen & p. Kujamäki (eds) Translation universals: Do they exist? (pp. 143-164). John Benjamins.

Paré A. (2017). Re-thinking the dissertation and doctoral supervision/Reflexiones sobre la tesis doctoral y su supervisión. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 4(3), 407-428.

Pramoolsook, I. (2009). Three fundamental concepts for genre transfer studies: A case of postgraduate dissertation to research article. Suranaree J. Soc. Sci., 3(1), 113-130.

Puurtinen, T. (2003). Genre-specific features of Translationese? Linguistic differences between translated and non-translated Finnish children’s literature. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 18(4), 389-406.

Redelinghuys, K., and Kruger, H. (2015). Using the features of translated language to investigate translation expertise: A corpus-based study. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 20(3), 293-325.

Rojo, G. (2002). Sobre la Lingüística basada en el análisis de corpus. UZEI Hizkuntza-corpusak. Oraina eta geroa (2002-10-24/25). http://uzei.com/Modulos/UsuariosFtp/Conexion/archivos54A.pdf.

Sánchez Pérez, A. (1995). Definición e historia de los corpus. In A. Sánchez, R. Sarmiento, p. Cantos, and J. Simón (Eds.). Cumbre: corpus lingüístico del español contemporáneo: fundamentos, metodología y aplicaciones. SGEL.

Sánchez Ramos, M. M. (2019). Corpus paralelos y traducción especializada: ejemplificación de diseño, compilación y alineación de un corpus paralelo bilingüe (inglés-español) para la traducción jurídica. Lebende Sprachen, 64(2), 269-285. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2019-0015.

Scott, M. (2017). WordSmith Tools version 7. Stroud: Lexical Analysis Software. http://lexically.net/wordsmith/

Seghiri, M., and Arce Romeral, L. (2021). La traducción de contratos de compraventa inmobiliaria: un estudio basado en corpus aplicado a España e Irlanda. Peter Lang.

Several Authors (Cambridge University Press). (2020). English Grammar of Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/british-grammar/.

Several Authors (St Mt San Jacinto College) (2020). Prepositions and conjunctions. https://www.msjc.edu/learningresourcecenter/mvc/mvcwritingcenter/documents/handouts/Prepositions-and-Conjunctions.pdf.

Stubbs, M. (1986). Lexical density: A computational technique and somefindings. In M. Coulthard (Ed.). Talking about text (pp. 27-48). University of Birmingham.

Tognini-Bonelli, E. (2001). Corpus linguistics at work. John Benjamins.

Toury, G. (1991). What are descriptive studies in translation likely to yield apart from isolated description? In K. Leuven-Zwart, T. Naaijkens, A. Bernardus, M. Naaijkens (Eds.). Translation Studies: The State of the Art. Proceedings from the First James S. Holmes Symposium on Translation Studies (pp. 179-192). Rodopi.

Un-udom, S., and Un-udom, N. (2020). A corpus-based study on the use of reporting verbs in applied linguistics articles. English Language Teaching 13(4), 162-169.

Venuti, L. (1995). The Translator’s Invisibility. Routledge.

Xiao, R. (2010). How different is translated Chinese from native Chinese? A corpus-based study of translation universals. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 15(1), 5-35.

Xiao, R., and Yue, M. (2009). Using corpora in translation studies: The state of the art. In p. Baker (Ed.). Contemporary Corpus Linguistics (pp. 237-262). Continuum.

Yang, X. (2018). A corpus-based study of modal verbs in Chinese learners’ academic writing. English Language Teaching, 11(2), 122-130.

Zanettin, F. (2013). Corpus methods for descriptive translation studies. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 95, 20-32.

1 The STTR formula used by the program is a modification of the original TTR (types/token ratio) formula. Following a demonstration of the influence of the corpus size on the results, Scott (2017) proposed this new formula that standardizes the results for any 1,000 words, calculating the TTR for each 1,000 running words and finally averaging the results for the entire text (Redelinghuyis and Kruger, 2015).

2 The calculator wizard and the information about the formula used for the calculation are available at http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/llwizard.html