:: TRANS 26. MISCELÁNEA. Didáctica. Págs. 329-347 ::

Public service interpreting and translation: training and useful skills for the labour market

-------------------------------------

Bianca Vitalaru

Universidad de Alcalá

ORCID: 0000-0003-0618-3867

-------------------------------------

Public service interpreting and translation (PSIT) is a subfield of translation and interpreting. Still, it could stand independently due to the variety of subfields it encompasses and, thus, the job possibilities. Despite being considered an under-professionalised field in Spain, hundreds of graduates are interested and trained in PSIT, hoping to enhance their employment chances. However, this field relies on very few studies that focus specifically on employment, the skills that can make students employable or the graduates’ perspectives regarding the usefulness of the education and training received. This paper has three objectives: to explore the most useful skills for the PSIT labour market in Spain from the perspective of the graduates of a specific programme based on a selection of skills, to explore the potential relationship between internships and labour market insertion and to determine differences by language pairs. Results are obtained based on data gathered through a questionnaire sent to this specific training programme graduates. They show essential differences between the perception of the different language pairs in which the programme is taught, which could be correlated with other labour market needs and job opportunities. In turn, these differences also affect the usefulness of the skills that the students develop in the programme. Moreover, despite the variety of the subfields involved in the PSIT field, there is a specific relation between internships and certain jobs, especially for part of the Arabic, Chinese, French, and Russian groups graduates.

KEY WORDS: public service interpreting and translation, labour market, employment, employability, skills.

Traducción e interpretación en los servicios públicos: formación y competencias útiles para el mercado laboral

La traducción e interpretación en los servicios públicos (TISP) es un subcampo de la traducción e interpretación, pero podría considerarse como un campo independiente debido a la variedad de ámbitos que abarca y, por tanto, a las posibilidades de trabajo. A pesar de ser considerado como un campo subprofesionalizado en España, cientos de licenciados se interesan por y se forman en TISP, con la esperanza de mejorar sus oportunidades de empleo. Sin embargo, este ámbito cuenta con muy pocos estudios que se centren específicamente en la empleabilidad, en las competencias que pueden mejorar la empleabilidad de los alumnos o en las perspectivas de los egresados sobre la utilidad de la formación recibida. Este trabajo tiene tres objetivos: explorar las competencias más útiles para el mercado laboral de TISP en España desde la perspectiva de los egresados de un programa a partir de una selección de competencias, explorar la posible relación entre las prácticas y la inserción laboral y determinar las diferencias por combinación lingüística. Los resultados se basan en los datos recogidos mediante una encuesta enviada a los egresados de este programa formativo específico. Estos muestran que existen diferencias importantes entre la percepción de las distintas combinaciones lingüísticas en las que se imparte el programa, que pueden relacionarse con las diferentes necesidades del mercado laboral y las oportunidades de empleo. A su vez, estas diferencias también afectan a la utilidad de las competencias que los alumnos desarrollan en el programa. Por otra parte, a pesar de la variedad de los entornos implicados en el ámbito de la TISP, existe una relación específica entre las prácticas y un determinado tipo de puestos de trabajo, especialmente para una parte de los egresados de los grupos de árabe, chino, francés y ruso.

PALABRAS CLAVE: traducción e interpretación en los servicios públicos, mercado laboral, empleo, empleabilidad, habilidades.

-------------------------------------

recibido en agosto de 2021 aceptado en septiembre de 202

-------------------------------------

1. IntroducTION

Employability is considered critical both by employers and educators worldwide. It refers to several aspects that help an individual ensure and maintain a job (“decent work”), progress “within the enterprise and between jobs”, and be able to face “changing technology and labour market conditions” (ILO, 2004, para. 10). It has been used in the context of ensuring employment to graduates after 2008 (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2010, 2012; EHEA 2015, as cited in Rodríguez de Céspedes, 2017) and is essential in higher education considering that the Bologna process focused on implementing “a quality education system connected with research and lifelong learning to ensure graduates’ employability across Europe” (Rodríguez de Céspedes, 2017, p. 110).

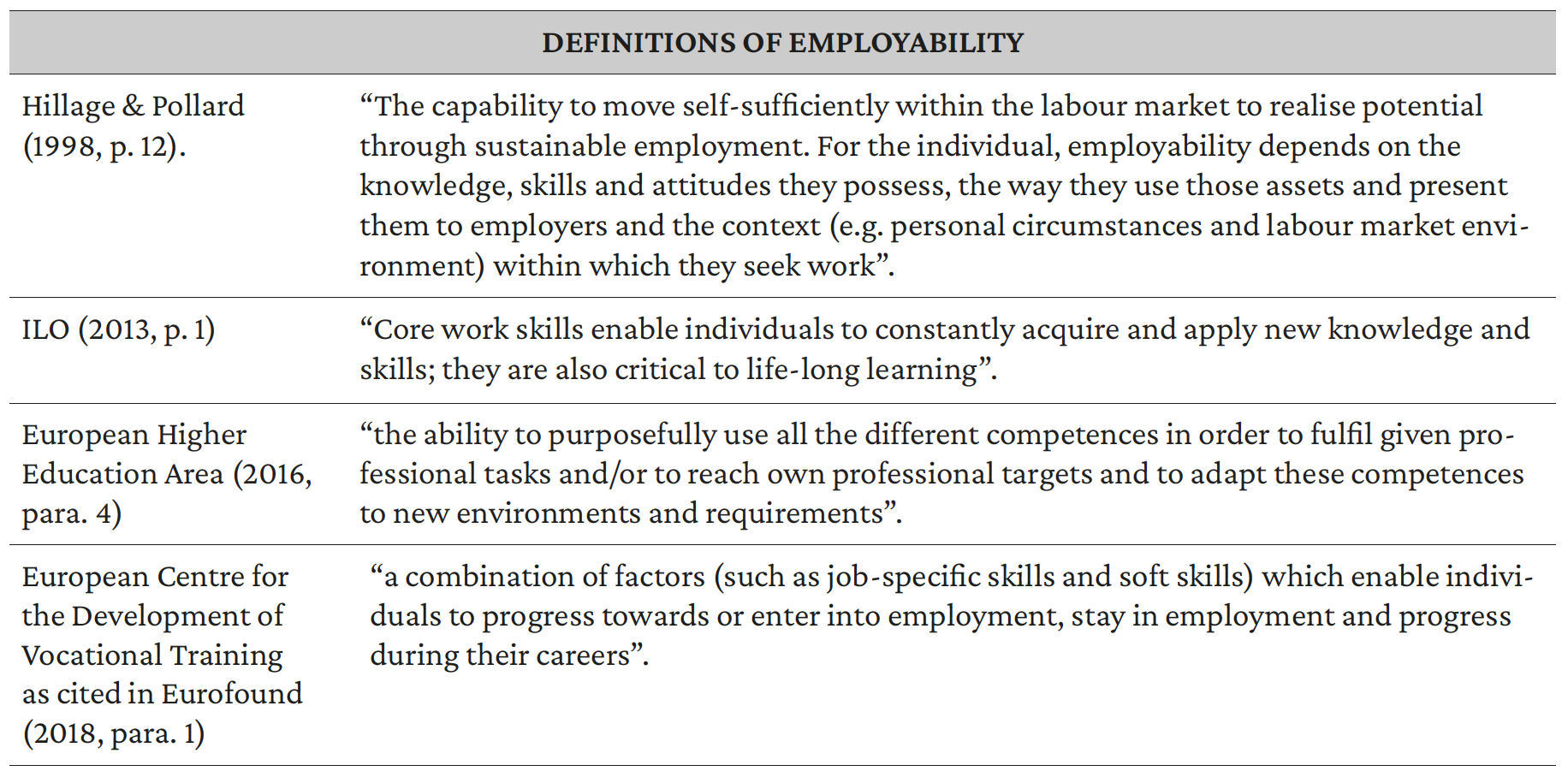

In its 2012 and 2015 communiqués, the Bologna Follow-up Group underlined the development of new competences considering the continuous changes in the labour market during the graduates’ education and training1 period and professional life. Therefore, their employability depends not only on the means they have for finding a job but also on developing several “skills, attitudes and aptitudes that evolve through [their] lives” (Rodríguez de Céspedes, 2017, p. 110). In other words, what employers tend to look for are soft or transferable skills2 or what ILO (2013) calls “core work skills” (p. 1) or “core skills for employability” (p. 3). Several definitions place the individual skills at the core of employability (Table 1 on the next page).

Employability is a fundamental topic of discussion in both the professional and the academic field of Translation & Interpreting (T&I). For example, Rodríguez de Céspedes (2017) proposed good practices for enhancing employability skills based on needs identified because of conversations between HEIs and industry stakeholders, as well as a review of training and developments in the Master’s in Translation Studies (University of Portsmouth, England). Moreover, Galán-Mañas (2017) proposed similar actions at the University of Barcelona (Spain). Furthermore, several studies focused on the employability of Spanish T&I undergraduate studies (Álvarez-Álvarez and Arnáiz-Uzquiza, 2017; Schnell and Rodríguez, 2017; Cifuentes Férez, 2017; Galán-Mañas, 2017 and Vigier, 2018). Lastly, the PACTE group carried out a research project that focused on competence levels in translation and levelling descriptors for “developing a common European framework of reference for translation’s academic and professional arenas” (PACTE, 2018, p. 111).

On the other hand, Public Service Interpreting and Translation (PSIT) is a field that involves several settings: healthcare, social services, education, administration, and legal services (Valero-Garcés, 2014; Sánchez Ramos, 2020). This field is a subfield of T&I (Valero-Garcés, 2014; Valero-Garcés, n.d.), but it could stand on its own due to the variety of fields it encompasses and thus, the job possibilities. Despite being considered an under-professionalised field (Lázaro Gutiérrez & Álvaro Aranda, 2020; Valero-Garcés, n.d.), hundreds of graduates are interested and are trained in PSIT with the hope of enhancing their chances of employability. However, this field relies on very few studies that focus specifically on employment or employability in PSIT. In fact, very few studies consider the skills that can make students employable or even the graduates’ perspectives regarding the applicability of the education and training received for the labour market.

Table 1. Definitions of employability.

This article fills that gap by focusing on the graduates of a graduate programme that teaches PSIT at Universidad de Alcalá in Madrid (Spain). The programme is the only graduate programme in Spain that trains in several PSIT fields. It trains in several language pairs (Spanish-Arabic/Chinese/English/French/Polish/Romanian/Russian) and it has been taught as a programme endorsed by the Spanish regulatory agency, National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA), since 2006. This article has three main objectives. First, to explore the most useful skills for the PSIT labour market in Spain from the graduates’ perspective based on a selection of skills from the ones used in the project ‘Employment and the future of the profession’. This project was carried out by the European Commission Directorate-General of Translation and the European Master’s in Translation Network (2015-2016). Second, to explore the potential relationship between internships and labour market insertion. Third, to determine differences by language pairs. Two research questions will be used to guide the research: 1. What are the most useful skills developed in the programme for the PSIT labour market by language pairs? and 2. Were internships helpful in finding a job?

For these purposes, this study will use data gathered through a questionnaire sent to graduates of this specific PSIT programme.

2. EMPLOYABILITY AND UNIVERSITY TRAINING

2.1. T&I and PSIT job profiles

Since PSIT is a subfield of the T&I field, it not only shares several of its characteristics in terms of work methodology (T&I modalities, techniques, and strategies) but also work opportunities. The possible jobs that PSIT graduates could have access to are listed for T&I undergraduates by the Spanish National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA, 2004) but also include others specific to the diversity of the PSIT field. Based on the information presented in the Application for quality verification of the programme under analysis (2009/2010), Vitalaru (2021, pp. 252-253) classifies them as follows:

a. jobs related explicitly to T&I as well as terminological tasks:

- translator and interpreter specialised in health, legal, or administrative matters.

- interpreter in cultural, economic, or administrative relations in multiple fields (legal, health, educational settings).

- generalist translator and interpreter.

- lexicographer, terminologist, and linguistic project manager.

b. jobs related to mediation and intercultural/interlinguistic communication:

- interlinguistic and intercultural mediator in hospitals and schools.

- specialist in intercultural mediation, an activity that covers a broad spectrum of professional opportunities (specialised tour guide, mediator or economic or political adviser, people who work in the cultural world as agents, publishers, organisers of exhibitions).

c. teaching:

- translation and interpreting teacher.

d. other jobs related to time management, consulting, and proofreading:

- planner and linguistic advisor for various types of companies and the media.

- manager and advisor in international relations.

- reader, editor, proofreader, and reviewer in publishing houses or various institutions or companies.

2.2. Employability: analysis of different perspectives

Regarding employment and Spanish T&I undergraduate degrees, several studies were chosen as representative as they reflect different perspectives on the field. They can be grouped into three categories.

First, three Spanish studies focused explicitly on employability skills, underlining that higher education institutions must focus on developing more specific employability skills and work with practitioners and/or service providers to build a practical and adapted curriculum. Álvarez-Álvarez & Arnáiz-Uzquiza (2017) analysed the implementation of the “practical components” of employability within the Spanish T&I university curricula after the application of the Bologna Process by the Spanish higher education system (p. 139). They compared the perception of three different groups regarding the acquisition of employability skills: employers, undergraduates, and final-year undergraduates. They included significant information regarding the type of training required for undergraduates to be “considered fit-to-work professionals” (p. 139). On the other hand, Schnell & Rodríguez (2017) reflected on employability as one of the main factors that influenced “the quality framework of Higher Education”, taking into account the fact that programmes were analysed considering “the employability rates of their graduates and employers’ satisfaction” (p. 160). They provided the translation service providers’ perspectives regarding the graduates’ employability assets in the Spanish university context. They underlined the need to balance knowledge from academics and practitioners when designing the T&I curriculum and to introduce content that enhanced employability skills. Lastly, Cifuentes Férez (2017) focused on the ten most important employability skills according to three groups: graduates, professors, and translators and interpreters at the University of Murcia (Spain). The results showed that their perspectives had both common elements and differences of opinion regarding their perception of skills essential for employability in the current labour market. Her conclusions underlined some of the skills that should be further worked on, such as the review process, the use of assisted translation programmes, the layout and editing processes, and a higher linguistic level in foreign languages. Moreover, the study showed that the specific competences particularly valued by the labour market were leadership, flexibility, adaptation to new situations, teamwork, and relating to people from the same or different professional fields.

Second, specific actions taken to improve employability and propose possible solutions are also discussed. Galán-Mañas (2017) analysed some of the activities carried out to enhance the employability of graduates in T&I through a specific programme designed to improve employability at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in 2011-12 and 2014-15. It included conferences, workshops, visits to centres, personalised tutorials, curricular internships, Final papers, practical classes based on active methodologies, a competency test, and dissemination of job offers. She concluded by underlining the difficulties encountered when analysing the actual employability of the graduates who attended the programme, the labour insertion of T&I graduates in general due to the variety of tasks performed, and the precariousness of the recent graduates’ jobs (2017). She also pointed out the importance of considering employability not only as a “quantitative indicator, but also (and above all) as a qualitative indicator” (p. 165).

Third, the perspective of translation companies and freelance practitioners is also considered by Rico and Garcia (2016), who discussed the situation of the Spanish translation labour market in 2014-2015, its characteristics, and future trends (2016). They focused on aspects such as the requested language pairs, user needs, business models, pricing strategies or translation expenditure. Some general results highlighted the five language combinations that made up the service offered: English, French, German, Portuguese, and Italian. The conclusions underlined the private company as the most common type of client for both groups, with experience in the industrial, technical fields, pharmaceutical, legal, and tourism fields, as well as high demand for the technological, general, and advertising translation.

2.3. Employability and graduate studies

We found few studies focusing on market needs or employability and graduate university training in T&I and PSIT. Below, we will highlight the findings of the most representative research found, that is, regarding T&I graduates in China, translation graduates of European programmes in England, and PSIT graduates in Spain.

First, Wu & Jiang (2021) analysed the employability of graduates of the Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI) between 2015 and 2020 at one first-tier university in Shanghai. They concluded that a nationwide revision of the MTI curricula was necessary, including “updated syllabuses catering to the employability requirements in China’s workplaces”, considering that the employability requirements had not been wholly met in several industries and professions (p. 1).

Second, studies such as Valero-Garcés & Gambier (2014), Valero-Garcés & Toudic (2014), Krause (2017), Valero-Garcés & Cedillo Corrochano (2018), and Valero-Garcés (2018) discussed the employability of the graduates and included reflections about the future of translation as a profession. They focused on European projects related to the translation market and employability skills through surveys conducted at the European level. Three surveys were presented in these studies to provide an overview of the translation market:

- Optimale (2011-2013), which was created by the Directorate-General for Education and Culture of the EU to “gain a clearer view of the needs of the translation industry in terms of competences” and identify “other competences that employers valued and looked for in their employees” (Valero-Garcés & Toudic, 2014, p. 185), apart from linguistic and translation competences. It addressed language service providers and revolved around five items considered significant to show professional competence: experience versus knowledge, translation-related competences, specialisation, technological competence, project management and customer relations, and marketing competences (Valero-Garcés, 2018; Valero-Garcés & Toudic, 2014).

- Employment and the future of the profession (2015-2016), which was carried out by the European Commission Directorate-General of Translation (DGT) and the European Master’s in Translation Network (EMT). It focused on understanding details about the access graduates who had completed a Master’s from the EMT network had to the job market, employment details, and applicability of competences developed from a list of seventeen. These competences were: linguistic ability in the source language, linguistic ability in the target language, knowledge of other cultures, general culture, proficiency in computer-assisted translation, computer skills, general translation, specialised translation, personal management skills, terminology, information mining, editing skills, postediting, digital editing, project management, synthesis skills, technical writing skills, among others (Valero-Garcés, 2018).

- LSP Network survey (2016-2017), which was carried out every year by the European Union of Associations of Translation Companies (EUATC) and supported by the DGT through the LIND (Language Industry) project and the EMT network. Its aim was to determine the characteristics of the industry by providing a broader perspective. According to the 2016 and 2017 surveys, the most requested services were legal services for translation companies and freelancers. Results vary depending on the year and the type of language service provider for the rest of the services (Valero-Garcés & Cedillo Corrochano, 2018; Valero-Garcés, 2018).

Some essential characteristics of the labour market that can be derived from the results of these surveys are the vital role that machine translation and technology play in the professional reality of the translator, the tendency to outsource linguistics and non-linguistics tasks, the variety of dimensions involved in the technological competence (Valero-Garcés, 2018), the various possibilities of jobs related to terminological work, and the need to adapt translation programmes (Krause, 2017; Valero-Garcés, 2018). Regarding the reflections for the future, the critical role of the cooperation between university and job market/enterprise is underlined (Valero-Garcés & Cedillo Corrochano, 2018; Valero-Garcés, 2018), as well as the responsibility that universities have in assuring their graduates’ awareness regarding “the current and future needs of their potential employers” (Valero-Garcés, 2018). In terms of the competences required for the labour market, theoretical and practical academic training should be combined with external internships and skills should be varied. These skills should include project management, use of CAT tools, and quality control skills, ultimately allowing students to have the multidisciplinary profile that the translation industry is looking for nowadays (Valero-Garcés, 2018).

Moreover, Cuminatto, Baines, & Drugan (2017) showed how the University of East Anglia (England) had embedded employability within its curriculum at master’s and undergraduate levels for several years. They argued that it should be embedded in T&I courses in general. Moreover, they highlighted the importance of real-world tasks, including collaborations while translating for real clients, to address employability in an effective way.

Lastly, Vitalaru (2021) specifically addressed the employability of the PSIT graduates of a Master’s degree at the University of Alcalá (Spain) and compared results by language pairs considering the types of jobs and the fields they worked in as well as the perception regarding the applicability of general skills to the labour market. The study showed that most graduates found jobs related to T&I. However, it also showed the need to consider the labour market of the language pair involved when designing the training offered since the skills perceived as useful by the different language pairs are different.

3. Context and method

3.1. The Master’s Degree in Intercultural Communication, Public Service Interpreting and Translation

The Master’s Degree in Intercultural Communication, Public Service Interpreting and Translation (PSIT programme) at Universidad de Alcalá is a graduate programme taught since 2006 in several language pairs: Spanish-Arabic/Chinese/French/English/Polish/Romanian/Russian3. It aims to train in PSIT, in three main settings: intercultural communication, healthcare and legal-administrative settings; the last one includes asylum and refugee contexts, police and judicial contexts, and social services.

The competences that the programme aims to develop are meant to allow graduates to work autonomously, ultimately enhancing employability. They can be summarised as follows. On the one hand, considering the terminology of the EMT Framework (EMT, 2017), it produces the following competences: T&I competences (including thematic, textual, and information mining skills), linguistic and cultural competence, and technology and service provision in relation the PSIT labour market. On the other hand, it develops soft skills such as time management, problem-solving, working autonomously, knowledge integration and applying complex reasoning to different contexts (Curriculum competences, 2021).

As far as its structure, it includes nine subjects, grouped in five modules (60 ECTS4): 1. Intercultural communication and PSIT techniques and tools; 2. T&I in healthcare settings; 3. T&I in legal and administrative settings; 4. Internship; and 5. Master’s Thesis. SIX of the subjects are taught by language pair, and the rest are common to all language pairs.

The subjects it teaches are varied, and each module has a different objective. The first module introduces intercultural communication, PSIT and PSIT techniques and tools, among which technological and research skills are essential, preparing students for developing the basic skills necessary for the T&I subjects. The second and third modules include intensive on-going practice through two translation-oriented5 and two interpreting-oriented subjects (for healthcare and legal-administrative settings). The fourth module, Internship in institutions and companies, aims to apply the skills developed to the professional field and improve the student’s knowledge of the characteristics of the professional market through hands-on experience. Lastly, the Master’s Thesis aims on developing the research competence and involves working autonomously under the supervision of an advisor (Curriculum, 2022).

3.2. Method

The approach used is descriptive, through the analysis of part of the data gathered through a questionnaire sent to graduates of the PSIT programme in January 2019. The questionnaire was designed as an online survey using an online design tool and was structured into 28 questions. Of them, 26 were close-ended questions, and two were open-ended questions. For this article, only four close-ended questions will be used to address two research questions: 1. What are the most useful skills developed in the programme for the PSIT labour market by language pairs? and 2. Were internships helpful in finding a job?

To answer the first research question, the following question was included in the questionnaire:

14. What were the most useful competences for the labour market in PSIT that you developed during your Master’s training? Please choose the answers that apply: linguistic competence, cultural knowledge, general knowledge, CAT tools, ICT skills, general translation, specialised translation, time management, terminology, information mining, revision, proofreading, postediting, online revision, project management, synthesis, technical writing skills, other.

To answer the second research question, three questions were used:

20. What tasks did you carry out during your internships in companies/institutions while you were a Master’s student? Choose the options that apply: translation, correction, alignment, terminology management, desktop publishing, technical writing, project management, proofreading, editing, or other (please specify).

21. Were internships useful for finding a job? Choose the option that applies: Yes, no, more or less.

23. After completing the Master’s degree (immediately after or later), did you collaborate with or work for the company/institution where you completed the internships for your Master’s degree? Choose the option that applies: Yes, no.

Two hypotheses are considered as a starting point. In the same line as Vitalaru (2021), who showed differences between the language pairs, the first hypothesis is that the different language pairs have different perceptions regarding the usefulness of the selection of skills proposed for the labour market. Moreover, in the context of combining theoretical and practical training and knowledge obtained from external internships (Valero-Garcés, 2018), the second hypothesis is that there is a relationship between internships and finding a job as a PSIT graduate. This can be translated either in the usefulness of the skills developed during the internships or in the collaborations between the graduates and the internship centres after the internships were completed.

Different links to questionnaires by language pairs were emailed to graduates from all the language pairs who had completed the programme between 2006 and 2017. This involved 750 out of a total of 920 graduates, after leaving out email addresses that were no longer available, graduates of the Polish group, whose number of students was deficient compared to the rest of the groups, and students who had not managed to complete the programme. It was available online for two months with information about the objectives and characteristics of the study. Moreover, graduates were adequately informed about their rights regarding participation (anonymous and voluntary) and privacy following the university policy. The information was collected by language pairs to facilitate the comparison of the data obtained.

4. RESULTS

This section includes three subsections, organised as follows: contextual details regarding the language pairs who participated and the employment situation of the participants, results regarding the skills perceived by graduates as beneficial for the labour market, and results related to the perception regarding internships.

4.1. Response rate, groups, and professional aspects

145 graduates from the 2006-2017 academic years answered the questionnaire, with representatives from all the language groups in which the programme had been taught. The response rate by groups (language pairs)6 is as follows: English (37%), Chinese (23%), Russian (17%), French (14%), Arabic (5%), and Romanian groups (4%). The 2016-2017 academic year had the highest response rate (30%).

Some aspects regarding the employment situation of the participants are relevant for this article and will, thus, be briefly summarised. First, 69% of the participants were working full-time, 9% were working part-time, 8% were working and studying, 3% were unemployed, 3% were studying, and 8% indicated other circumstances. Generally, 62% worked in a job related to the language services field, 56% in education, 18% in marketing & media, 17% in healthcare settings, 17% in other areas, 14% in tourism, 11% in logistics, and less than 10% in international aid. Moreover, 73% of the respondents underlined a direct relationship between their job and the T&I field. Most of the respondents had had several jobs when answering the survey, of which one was related to T&I (56%) or PSIT (21%), while 20% had had two jobs related to PSIT.

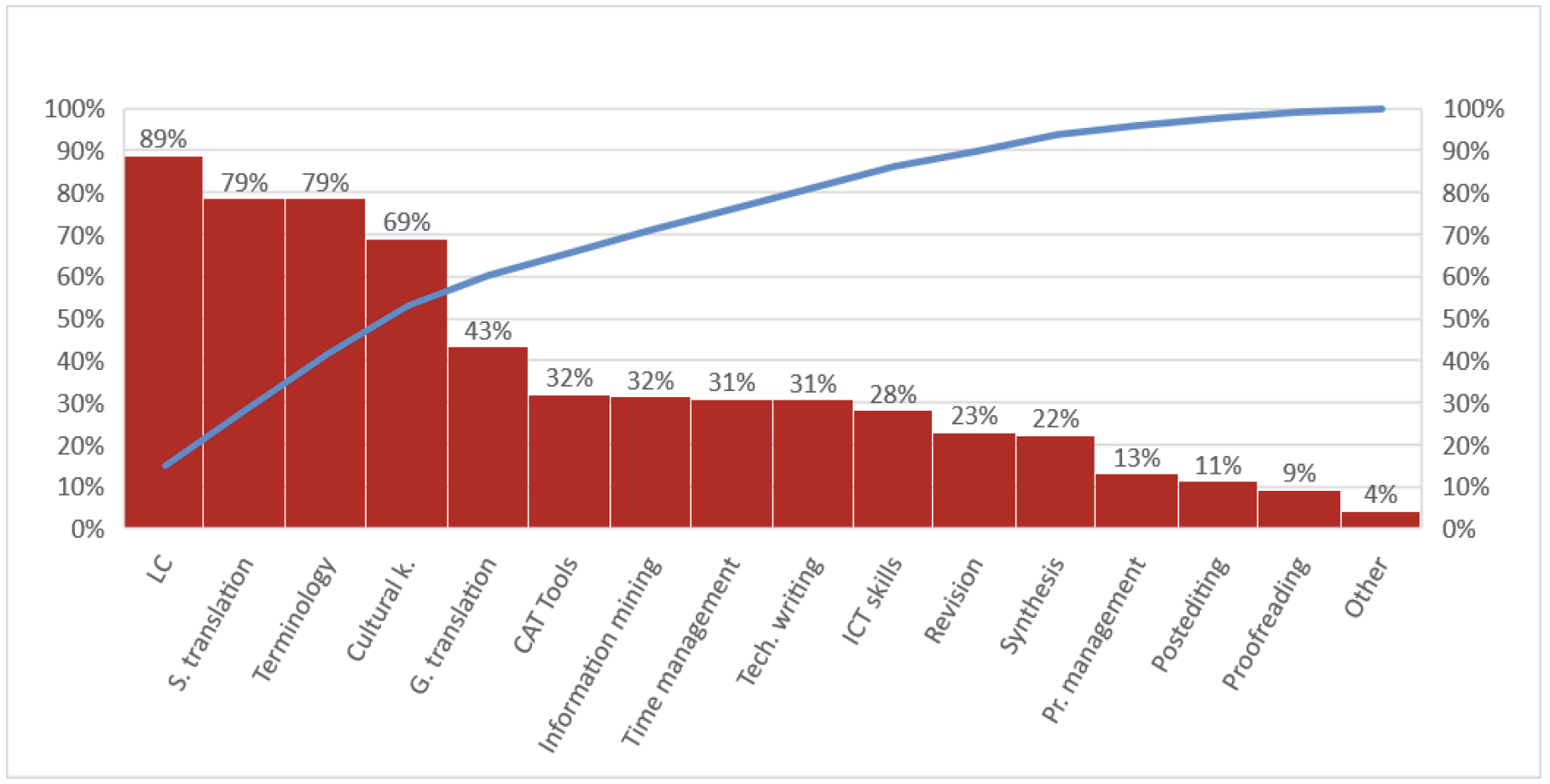

Figure I. The most useful skills.

4.2. Skills and labour market

4.2.1. The most useful skills7 in general

Question 14 of the questionnaire focused on identifying the most useful skills developed in the programme from a selection of aspects from the study conducted by the EC DGT and the EMT Board (2015-2016), precisely, the fifteen that follow: linguistic competence (LC)8, cultural knowledge, CAT tools, ICT skills, general translation, specialised translation, time management, terminology, information mining, proofreading, postediting, project management, synthesis, technical writing skills, and other (Figure 1).

The general results show that the skills perceived as the most useful, considering the training received, were LC (89%), specialised translation (79%), terminology (79%), and cultural knowledge (69%), followed by general translation (43%). Skills such as information mining, CAT tools, technical writing, and time management had lower percentages, between 28% and 32%. Other skills such as revision and synthesis obtained 23% and 22%. The lowest rates were indicated for skills such as project management, postediting, and proofreading, with 13%, 11%, and 9%. 4% of the participants stated the ‘other’ category.

4.2.2. Analysis of a selection of skills I: skills related to the linguistic, cultural, specialised translation, and terminological competences

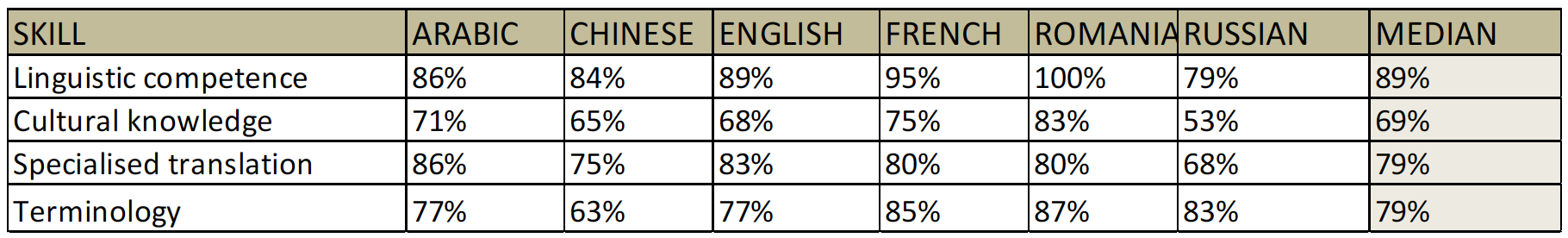

From the EC DGT and the EMT Board’s list of skills, a selection of five skills related to the general and specific competences of the PSIT programme was analysed by language pair. The first, LC, is developed throughout all the subjects of the programme). The second, cultural knowledge, is explicitly designed in one of the introductory subjects, Interlinguistic communication, which is common to all the language pairs, and in two interpreting-related subjects. The third, specialised translation, is developed in the two translation-related subjects taught by language pairs. The fourth, terminology, is introduced in the PSIT techniques and tools subject and applied in the four interpreting and translation-related subjects (Table 2).

We observe that most participants considered these aspects useful for the labour market. For the LC, the percentages are higher than 70% for all the groups and higher than 80% for five of the groups. For specialised translation, four groups obtained between 80% and 86% and one group received 75%, while for terminology, two groups received 77% and three groups obtained between 83% and 87%.

The results considering the aspects that had the highest percentages within each group vary. Thus, most of the Arabic group valued both specialised translation and LC (86%), followed by terminology (77%) and cultural knowledge (71%). Most of the Chinese group valued the LC (84%) and specialised translation (75%), while both cultural knowledge and terminology obtained less than 70% (65% and 63%). Most of the French group valued the LC (95%), terminology (85%), and specialised translation (80%). Its lowest percentage was given to cultural aspects (75%). Most of the English group had the highest values for LC (89%) and specialised translation (83%). Terminology follows (77%), while cultural knowledge obtained 68%. The Russian group received lower percentages in general. Rates were higher for terminology (83%) and LC (79%) and lower for specialised translation (68%) and cultural knowledge (53%). The Romanian group obtained a percentage between 80%-100% for all the elements. The highest rates were given to LC (100%) and terminology (87%).

The analysis by elements shows that the highest percentages for LC were obtained by the Romanian, English, Arabic, and Chinese groups (79%-100%). Moreover, the groups that most valued cultural competence were the Romanian, French, and Arabic groups. Generally, specialised translation obtained high percentages (75%-86%) for all but the Russian group (68%), while terminology obtained high rates (77%-87%) for all but the Chinese group (63%).

4.2.3. Analysis of a selection of skills II: skills related to the technological, service provision, translation, and personal competences

The literature review showed the importance of technological competence, including project management, CAT tools, and quality control skills (Valero-Garcés, 2018) to increase the student’s employment opportunities. Moreover, it also showed that skills such as the review process, the use of assisted translation programmes, and the layout and editing processes should be further worked on (Cifuentes Férez, 2017). On the other hand, the programme under analysis also aims to develop several skills that are part of the translation, technological or service provision competences, as well as several soft or transferable skills such as time management, autonomous work, etc.

Table 2. Skills related to the linguistic, cultural, specialised translation, and terminological competences.

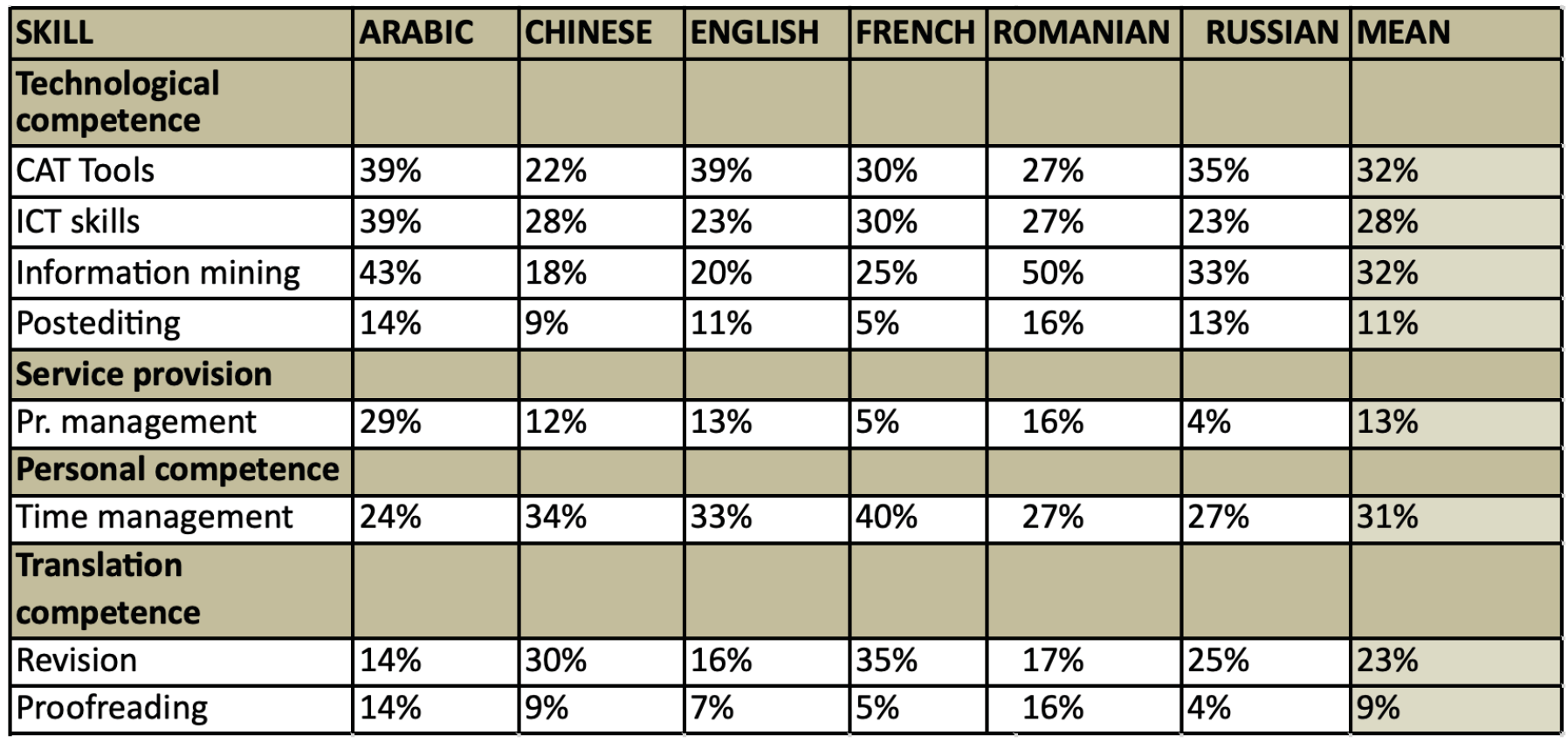

Considering all the previous observations, it would be helpful to know if there are differences in language pairs considering the usefulness of these different components for the labour market. Therefore, we selected from the EC DGT and the EMT Board survey only the following skills: related to technological competence (the use of CAT tools, ICT skills, postediting machine translation), translation competence (proofreading), service provision (project management), and personal skills (time management) (Table 3).

Table 3. Skills related to the technological, service provision, translation, and personal competences.

Considering the results for the technological skills by language pairs (Table 3), all the percentages are lower than those for the first selection of skills (Table 2). Thus, 43% of the Arabic group underlined information mining, followed by CAT tools and ICT skills (39%). The Chinese group highlighted ICT skills (28%) and CAT tools (22%), although with lower percentages than the rest of the groups. For the English and French groups, CAT tools (39%; 30%) and ICT skills (23%; 30%) were more useful, while for the Romanian group, information mining had the highest percentage (50%), followed by ICT skills and CAT tools (27%). CAT tools (35%) and information mining (33%) were the highest for the Russian group. On the other hand, it seems that CAT tools were used more by the Arabic and English groups while ICT skills, by the Arabic and French groups. Information mining was used more by the Romanian and Arabic groups. Postediting had the lowest percentage for this competence, with a general average of 11% and results ranging between 5% (French) and 16% (Romanian); it was used more by the Romanian and the Arabic groups.

Regarding project management (personal competence), the Arabic group obtained the highest percentage (29%), while the rest of the groups obtained between 5% and 16%. Time management varied between 24% (Arabic) and 40% (English).

Regarding the translation competence, the revision skill was more useful for the French (35%) and Chinese (30%) groups, while proofreading had the lowest percentage of the skills proposed. The general average for the latter is 9%, of which the highest scores were obtained by the Romanian (16%) and Arabic (14%) groups; the rest ranged between 4% and 9%.

Generally, the percentages obtained for the second selection of skills (Table 3) are lower (with values between 4% and 50%) than in the case of the first selection of skills (Table 2) (between 53% and 100%).

4.3. Internships

4.3.1. Types of internships tasks

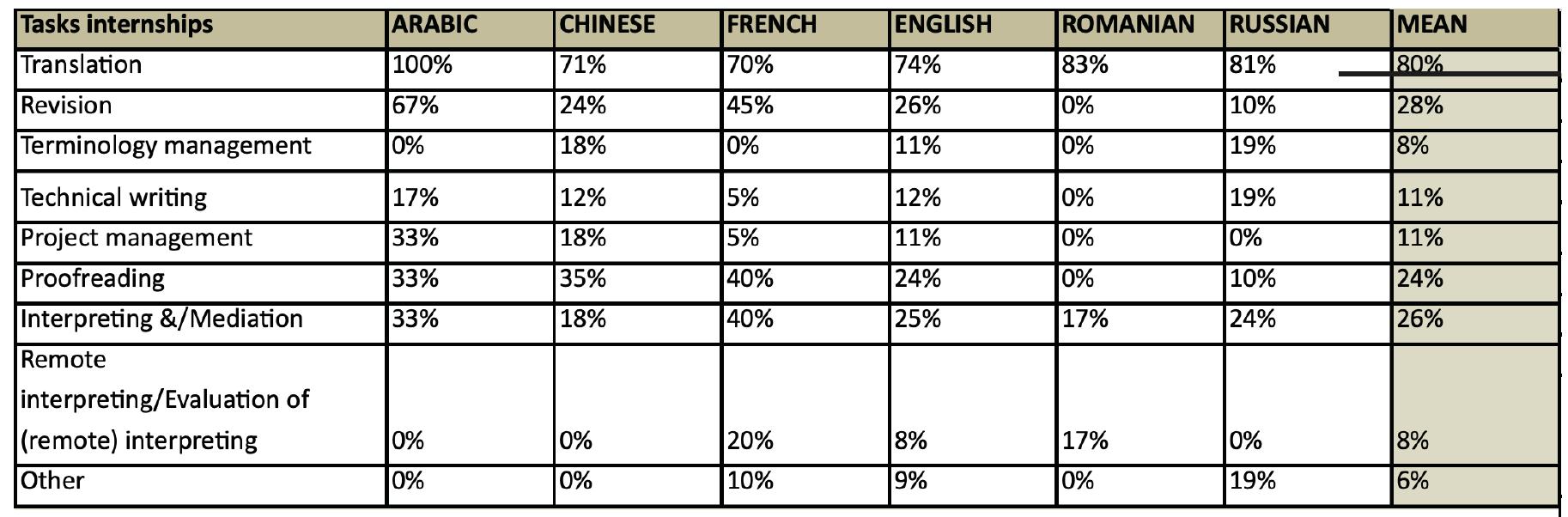

The participants were asked, for contextual purposes, about the types of tasks carried out during the internships based on a list of options considering the characteristics of the programme (question 20) (Table 4).

Table 4. Type of internships tasks.

Results show that most of the participants had performed translation tasks in all the language pairs (71%-100%) and translation-related tasks such as revision (with percentages between 10% and 67% of the participants), proofreading (with rates between 10 and 40%) as well as technical writing (with percentages between 5% and 19%) in all but the Romanian group. Participants from all the groups participated in interpreting and/or mediation tasks, with percentages between 17% and 40% and between 8% and 20% of the participants from the French, English, and Romanian group carried out remote interpreting-related activities9. Only the Russian (19%), Chinese (18%), and English (11%) groups practised with terminology management and all, but the Romanian and Russian groups practised project management (with percentages between 5% and 33%). Between 9% and 19% of the French, English, and Russian participants also mentioned other tasks.

4.3.2. Usefulness of the internships

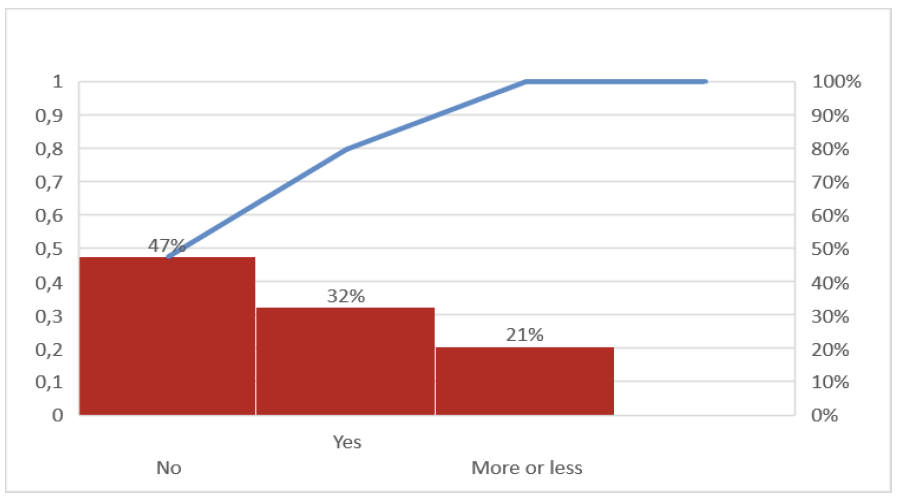

Regarding the usefulness of the internships for finding a job (question 21), 52% of the participants found it helpful, of which 32% indicated full usefulness and 21%, relative usefulness. 47% saw no direct benefit between the two aspects (Figure 2).

Figure II. Relation between internships and finding a job.

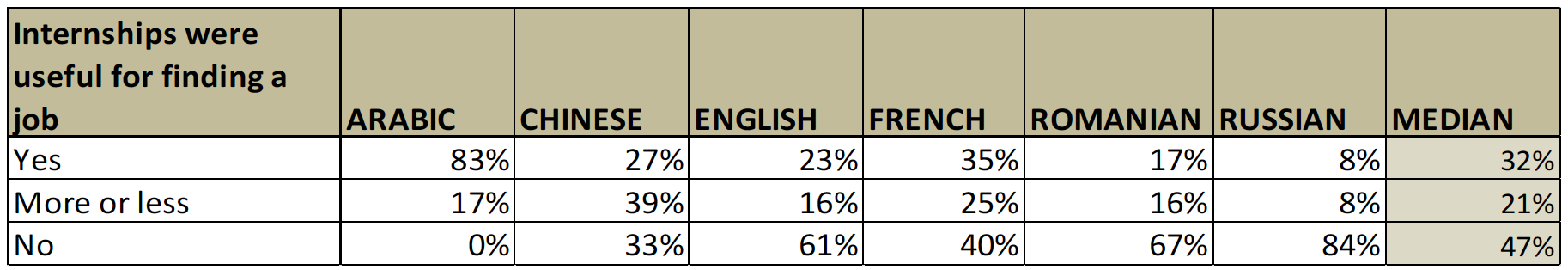

By language pairs (Table 5), all the groups indicated some degree of usefulness by choosing either “yes” or “more or less”. From the Arabic group, all the participants demonstrated usefulness (of which 83% with “yes”), from the Chinese group, 66% (of which 27% with “yes”), from the French group, 60% (of which 35% with “yes”), from the English group, 49% (of which 23% with “yes”), from the Romanian group, 33% (of which 17% with “yes”), and the Russian group, 16% (of which 8% with “yes”).

Table 5. Usefulness of internships.

4.3.3. Internships and employment

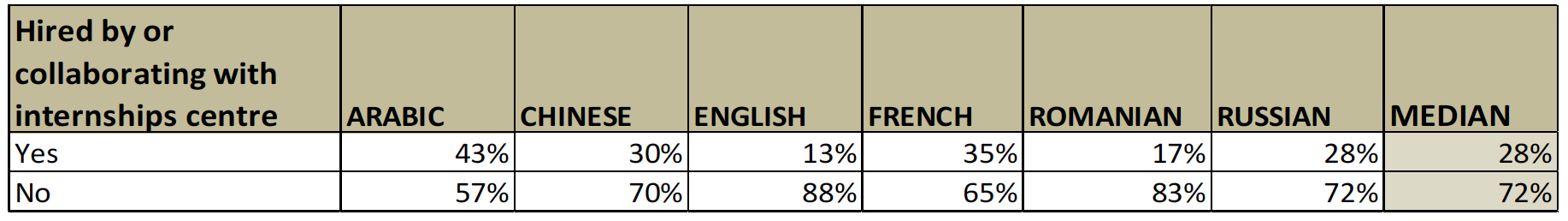

The percentage of participants hired by the same centre where they had carried out their internships or kept collaborating with them as freelancers was another item of the questionnaire (question 23). The results show that 28% of the participants were in this situation when answering the questionnaire. If considered by groups, the Arabic group had a percentage of 43% of the participants hired by the former internships centre, followed by the French (35%), Chinese (30%), Russian (28%), Romanian (17%), and English (13%) groups (Table 6).

Table 6. Percentage of participants hired by/collaborating with internships centres.

5. DISCUSSION

The first objective of this article is to identify the most useful skills for the PSIT labour market in Spain from the graduates’ perspective. Thus, the skills that the participants perceived as the most useful for the labour market from the list of skills proposed are LC, specialised translation, and terminology, for more than half the participants. Cultural knowledge was also useful, although for a slightly lower percentage. General translation was useful for approximately half of the participants. A third of the participants found skills such as information mining, CAT tools, ICT skills, technical writing, and time management useful, while only less than a quarter found skills such as synthesis, project management, proofreading, revision, and postediting useful.

The analysis results by language pairs confirms the first hypothesis and the results obtained by Vitalaru (2021). There are essential differences between the perception of the usefulness of the different skills for the language pairs involved. The analysis revealed essential details that a general analysis of results would not have detected.

First, LC, specialised translation, and terminology tend to be valued by all the groups as well as cultural knowledge, the latter, with a lower percentage than the rest. However, generally, fewer participants from the Russian group tend to find the same skills useful except in the case of terminology. This suggests that a significant part of the labour market for this language pair would require further analysis to identify specific needs. Moreover, terminology and cultural knowledge were found useful only by a little more than half of the Chinese group. This means that at least part of the labour market for this language pair also has different expectations or needs. Generally, considering the high percentages, it seems that these four skills can be regarded as aspects that can contribute to increasing the students’ employability in the PSIT field. However, there is no direct correlation between these two aspects in the questionnaire.

Second, skills related to technological aspects (such as information mining, CAT tools, and ICT skills) were useful for more participants from the Arabic, Romanian, and Russian groups than for the English and French groups. Generally, approximately a third of the participants found them useful, a percentage similar to the one for time management, a soft and transferrable skill. Since technology could be considered a key asset for the labour market, we could speculate regarding some implications. This could mean that some subfields of PSIT in which English and French are used do not necessarily require technology. It could also mean that technology is not used in that particular subfield, such as, for example, asylum and refugee contexts, police settings, healthcare, or social aspects in general (as opposed to translating for a private company) as it involves privacy restrictions, among other reasons. Moreover, it could mean that graduates do not use it frequently or that the training programme should improve the training offered from this point of view to show potential use or application under challenging circumstances. Postediting had the lowest percentage for this competence, which suggests that the graduates who participated did not find machine translation useful for the PSIT labour market or did not use it in their jobs. Proofreading and project management had similar results.

Third, cultural knowledge seems particularly useful for the Romanian, French, and Arabic groups. Apart from the general applicability of understanding cultural aspects and differences for all the language pairs, some reflections could be made considering the languages involved. The cultural distance between the Arabic group10 and European culture could be considered the main reason behind the high percentage regarding the skill’s usefulness. Moreover, the fact that the French group valued this category could also explain the knowledge or use of French by cultures other than the Spanish and French ones. African cultures also speak French, and some of the interpreting classes in the programme highlighted the importance of cultural aspects, intercultural mediation, and their potential for the labour market. In their professional experience, graduates might have also had to act in multicultural settings. However, in the case of the Romanian group, the results are surprising considering that the two cultures involved are European and relatively similar regarding the public services offered and general aspects. The results could be related to differences in the way the public services work and conceptual variations despite the apparent similarities between countries. On the other hand, although this skill was useful for more than half of the participants, it was perceived as useful by fewer participants in two non-European cultures (the Russian and the Chinese groups) as well as by the English group, formed primarily by Spanish students, British and/or American students.

The second hypothesis is that there is a relationship between internships and finding a job as a PSIT graduate, either due to the skills developed during the internships or through collaboration with internship centres after the internships were completed. From this point of view, more than half of the participants found the internships helpful in finding a job. This idea is relevant considering that most participants had carried out translation or interpreting-related tasks. It suggests that, despite the variety of settings involved in the PSIT field, there is a specific relation between internships and at least a particular type of job. If considered by language pairs, while the entire Arabic group and more than 60% of the Chinese and the French groups found the internships helpful, the English and the Romanian groups found them less helpful.

On the other hand, it is essential to underline that, in a small percentage, almost a third of the participants were hired by the same centre where they had carried out their internships or kept collaborating with them. Most of them belonged to the Arabic group, followed by the French, Chinese, and Russian groups. This also suggests the critical relationship between some internships and the labour market. There could be different reasons why some centres hire or collaborate with trained PSIT graduates. First, the increased awareness about the need to rely on a trained translator or interpreter could be a factor, as well as a particular need for that language pair at a certain point due to a social or cultural lack not covered or not fully covered by the centre itself. At the same time, the skills shown by those students during their internships could also be a factor when deciding to extend the collaboration or even create a service within the centre when it did not exist. In any case, if we consider the different social, political, and economic events that affected Spain in the last ten years, we may find more specific and plausible explanations. Unfortunately, this study has not explored the reasons, which could be an interesting future line of research.

Lastly, considering both the perception of the usefulness of internships and the fact that a third of the participants collaborated with the former internship centres, we could state that the experience and skills acquired during the internships can increase the students’ level of employability.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The lack of stability of the labour market in PSIT due to the under-professionalisation of the field in Spain is an aspect that should be considered in any analysis. Moreover, the variety of specialisations it encompasses and the social and economic factors that affect the labour market needs tend to be reflected both through the jobs graduates can access after completing the programme and through the internships provided by the institutions and companies that collaborate with the programme. Despite these aspects that make labour market insertion difficult for PSIT graduates, there are work opportunities for the PSIT and T&I fields.

In this context, this article provided insights into the perception of aspects that could contribute to the students’ employability in the PSIT field. It focused, on the one hand, on certain skills that could affect a graduate’s employability and, on the other hand, on the potential relationship between the programme internships and the graduates’ job opportunities. Moreover, several aspects that can be explored through further research and limitations will be underlined.

First, there are differences between the perception of the different language pairs and the other labour market needs and, thus, job opportunities. In turn, these differences also affect the usefulness of the skills that the students develop in the programme. Therefore, the skills that graduates perceive as the most useful skills developed considering the labour market are linguistic skills, specialised translation, terminology, and cultural knowledge. However, the PSIT market needs for the Chinese or Russian groups could be further researched to gather more information about the details that could help enhance the students’ level of employability within this field. Similarly, technological skills also seem to require further research in general and especially by language pairs in the English, French, and Chinese groups. Moreover, machine translation and postediting, proofreading, and project management do not seem particularly relevant for the PSIT field, or its potential has not been sufficiently explored in the training programme. Finally, time management, a soft skill that tends to be valued by employers (Ena Ventura, 2012), and could be an asset in terms of employability, is indicated by an average of approximately a third of the participants within each language pair. This suggests that more focus should also be placed on this soft skill in the training process. More practice, open discussions, and explicit instruction regarding this skill as an actual asset could have a positive impact on the students’ perception. This could ultimately raise awareness about its importance and contribute to increasing their employability.

Second, despite the variety of settings involved in the PSIT field (healthcare, social services, education, administration, and legal services), there is a specific relation between internships and a particular category of jobs. This is applicable especially for those in the Arabic, Chinese, and French groups participants, who highlighted their usefulness. Although further research is necessary to explore the different factors that affect the relationship between the labour market and internships, this relation is evident in the collaboration with internships centres after the internships were completed, especially in the case of the graduates of the Arabic, Chinese, French, and Russian groups.

Third, results suggest that the job opportunities vary depending on the labour market for each language pair. In fact, some language pairs may require several subfields of public services (healthcare, asylum and refugee contexts, police settings, social services) while others require more private services. We could also say that the need for the language pair itself is a mere reflection of the fact that the different settings of the PSIT field have different market needs. On the other hand, these tendencies can also indicate other social, cultural, and perhaps economic conditions that affect a country’s labour market in a particular period. More research should be carried out to include the perspectives of other groups and factors to clarify more details.

Lastly, considering that the general aim of graduate training programmes is to enhance the employability of their students, these results and reflections may serve as a starting point for future training and research. They can help programme organisers make or adapt training decisions by language pairs and can guide the planning of future internships that prepare for labour market needs.

Some of the limitations of this study are the low response rate and the representativity of the samples for the different language pairs or the potential bias of the participants who found or did not find a PSIT job. To minimise this aspect, the analysis was carried out by language pairs and concerning the number of participants by language pairs.

REFERENCES

Álvarez-Álvarez, S., & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, V. (2017).Translation and interpreting graduates under construction: do Spanish translation and interpreting studies curricula answer the challenges of employability? The interpreter and translator trainer, 11(2-3), 139-159. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1344812

ANECA. (2004). Libro blanco del grado en traducción e interpretación. Universidad de Granada.

Application for quality verification. (2009/10). Memoria para la solicitud de verificación abreviada de títulos oficiales de posgrado. Universidad de Alcalá. https://www.uah.es/export/sites/uah/es/ estudios/.galleries/Archivos-estudios/MU/Unico/AM195_10_1_1_E_MU_COMUNICACION-INTERCULTURAL-INTERPRETACION-Y-TRADUCCION_OK.pdf

Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Training. In Cambridge.org dictionary. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/training

Cifuentes Férez, P. (2017). Las diez competencias fundamentales para la empleabilidad según egresados, profesorado y profesionales de la traducción y la interpretación. Quaderns, 24, 197-216. https://raco.cat/index.php/QuadernsTraduccio/ article/view/321770

Cuminatto, C., Baines, R., & Drugan, J. (2017). Employability as an ethos in translator and interpreter training. Interpreter and translator trainer, 11(2-3), 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1350899

Curriculum. (2022). Planificación de las enseñanzas y profesorado. Máster universitario en CIITSP. Universidad de Alcalá. https://posgrado.uah.es/es/masteres-universitarios/master/Comunicacion-Intercultural-Interpretacion-y-Traduccion-en-los-Servicios-Publicos/

Curriculum Competences. (2021). Competencias. Máster universitario en CIITSP. Universidad de Alcalá. https://www.uah.es/export/sites/uah/es/estudios/.galleries/Archivos-estudios/MU/Unico/AM195_11_1_2_E_Objetivos-y-Competencias_del-master_2021.pdf

Dictionary.com. (n.d.). Education. In Dictionary.com. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/education

Ena Ventura, B. (2012). Operaciones administrativas de recursos humanos. Editorial Paraninfo.

EMT (European Master’s in Translation). (2017). Competence framework. European Commission. https://ec. europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/emt_competence_fwk_2017_en_web.pdf

Eurofound. (2018, June 20). Employability. EurWORK European Observatory of Working Life. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/industrial-relations-dictionary/employability

European Higher Education Area. (2016, May). Employability - introduction. Employability. http://www.ehea.info/cid102524/employability-introduction.html

Galán-Mañas, A. (2017). Programa para la mejora de la empleabilidad de los egresados en traducción e interpretación. Un estudio de caso. Revista conexão letras, 12(17), 153-171. https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/conexaoletras/article/view/75624

Hillage, J., & Pollard, E. (1998). Employability: developing a framework for policy analysis. London Department for education and employment.

ILO. International Labour Office. (2004). Recommendation concerning human resources development: education, training, and lifelong learning. Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID,P12100_LANG_CODE:312533,en:NO

ILO. International Labour Office. (2013). Skills for employment. Policy brief. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_234467.pdf

Krause, A. (2017). Programme designing in translation and interpreting and employability of future degree holders. In C. Valero-Garcés, C. Álvaro Aranda, & M. Ginés Grao (Eds.), Superando límites en traducción e interpretación. Beyond limits in translation and interpreting (pp. 147-158). Editorial Universidad de Alcalá.

Lázaro Gutiérrez, R., & Álvaro Aranda, C. (2020). Public service interpreting and translation in Spain. In M. Štefková, K. Kerremans, & B. Bossaert (Eds.), Training public service interpreters and translators: a European perspective (pp. 71-87). Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave.

PACTE. (2018). Competence levels in translation: working towards a European framework. The interpreter and translator trainer, 12(2), 111-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2018.1466093

Rico, C. & García, A. (2016). Análisis del sector de la traducción. Abacus. Universidad Europea de Madrid. https://abacus.universidadeuropea.es/handle/ 11268/5057

Rodríguez de Céspedes, B. (2017). Addressing employability and enterprise responsibilities in the translation curriculum. The interpreter and translator trainer, 11(2-3), 107-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1344816

Sánchez Ramos, M. M. (2020). Documentación digital y léxico en la traducción e interpretación en los servicios públicos (TISP): fundamentos teóricos y prácticos. Peter Lang.

Schnell, B., & Rodríguez, N. (2017). Ivory tower vs. workplace reality. The interpreter and translator trainer, 11(2-3), 160-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1344920

Valero-Garcés, C. (2014). Communicating across cultures. a coursebook on interpreting and translating in public services and institutions. USA: University Press of America.

Valero-Garcés, C. (2018). Training and employability: what are the LSPs looking for and what can the graduates offer? International journal of innovative research in education, 5(1), 1-10. https://un-pub.eu/ojs/index.php/IJIRE/article/view/3461

Valero-Garcés, C. (n.d.). La traducción e interpretación en los servicios públicos (TISP). Diccionario histórico de la traducción de España. http://phte.upf.edu/traduccion-e-interpretacion-en-los-servicios-publicos/

Valero-Garcés, C., & Gambier, Y. (2014). Mapping translator training in Europe. Turjuman, 23(2), 279-303. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/revista/9864/A/2014

Valero-Garcés, C., & Toudic, D. (2014). Technological innovation and translation. Training translators in the EU for the 21st century. Verbeia, 0. https://journals.ucjc.edu/VREF/article/view/4145

Valero-Garcés, C., & Cedillo Corrochano, C. (2018). Approaches to didactics for technologies in translation and interpreting. Trans-kom, 11(2). http://www.trans-kom.eu/bd11nr02/trans-kom_11_02_01_Valero_ Cedillo_Introduction.20181220.pdf

Vigier, F. (2018). Is translation studies the Cinderella of the Spanish university field, or is it its new milkmaid? Transletters, 1, 167-183. http://helvia.uco.es/xmlui/handle/10396/18406

Vitalaru, B. (2021). Public service interpreting and translation: employability, skills, and perspectives on the labour market in Spain. The interpreter and translator trainer, 16(2). 247-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2021.1984032

Wu, Y., & Jiang, Z. (2021). Educating a multilingual workforce in Chinese universities: employability of master of translation and interpreting graduates. Círculo de lingüística aplicada a la comunicación, 86, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.5209/clac.75491

1 While “education” refers to the process that involves the acquisition of general knowledge and preparing for mature life or a profession through formal education (Dictionary, n.d.) “training” focuses on the development of skills needed to do a particular activity or job (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). In this paper, the word “training” will be used to refer to specialised training that focuses on the development of applied and specific skills.

2 We will use the term “skill” to refer to the “ability to apply knowledge and use know-how to complete tasks and solve problems” and “competence” to refer to the “ability to use knowledge, skills and personal, social and/ or methodological abilities, in work or study situations and in professional and personal development” (EMT, 2017, p. 3).

3 In the French, English, and Romanian groups, most of the students enrolled come from Spain and France (very few from African countries and only in some academic years) or Spain and very few from Great Britain and/or US or from Romania and Spain. In the Arabic, Chinese, and Russian groups, most of the students enrolled come mostly from Arabic countries, China, and Russia; very few from Spain.

4 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System ECTS, approx. 25 hs workload x 1 ECTS; a total of 1500 hours of workload.

5 Until 2021, the programme included three translation subjects and it distinguished between the administrative and legal settings.

6 The language pair considered in all the cases is the group’s language and Spanish.

7 The aspects included in the survey would fall under the types of competences described by the EMT (2017), that is, language and culture, service provision, technology, translation, and personal and interpersonal competence.

8 Although this aspect is worded as a competence, we preferred to keep the word used in the original survey.

9 indicated through the ‘other’ option

10 This group is formed by graduates with different cultural backgrounds having studied or lived in one of the following countries Morocco, Argelia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Spain.