:: MISCELÁNEA. Audiovisual. Págs. 349-371 ::

“Reinas unidas jamás serán vencidas”: Drag queens in the Iberian Spanish voice-over of RuPaul’s Drag Race

-------------------------------------

Davide Passa

Sapienza Università di Roma

-------------------------------------

RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009 – present) is an American reality television programme launched by RuPaul Charles, which has turned drag queens into a mainstream phenomenon. After briefly analysing the controversial figure of the drag queen in the light of Judith Butler’s performative turn, as well as drag lingo following Keith Harvey’s framework for identifying camp talk, this research aims at investigating the Iberian Spanish voice-over of Seasons 8 (2016), 9 (2017) and 10 (2018). This work seeks primarily to analyse the choices that are made in the target text to characterise drag queens in the localised Iberian Spanish version available on Netflix. The translation procedures mentioned in this study are partly adapted from Ranzato’s (2015) classification for culture-specific references. The analysis focuses mainly on the creative rendering of (semi-)homophony, drag terms, references to pop culture and grammatical gender.

key words: RuPaul’s Drag Race; voice-over; Queer Linguistics; camp talk; (Queer) Audiovisual Translation Studies; drag queens.

«Reinas unidas jamás serán vencidas»: drag queens en las voces superpuestas en español peninsular de RuPaul’s Drag Queen

RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009 – hoy) es un programa de telerrealidad y competición estadounidense conducido por RuPaul Charles, que ha convertido a las drag queens en un fenómeno mainstream. Después de analizar brevemente la figura controvertida de la drag queen a la luz del concepto de performatividad de Judith Butler, así como el drag lingo en relación al modelo establecido por Keith Harvey para identificar el camp talk, este artículo se centrará en el análisis del voice-over en español ibérico de las temporadas 8 (2016), 9 (2017) y 10 (2018). Se intentará analizar primariamente las decisiones tomadas por lor traductores para caracterizar lingüísticamente a las drag queens en la versión española disponible en Netflix. Las estrategias de traducción mencionadas en este artículo están parcialmente adaptadas a partir de una clasificación de Ranzato (2015) en su estudio sobre la traducción de las referencias culturales, y se centrarán en la reproducción creativa de la (semi-) homofonía, los términos drag, las referencias a la cultura pop y el género gramatical.

PALABRAS CLAVE: RuPaul’s Drag Race; voice-over; Queer Linguistics; camp talk; (Queer) Audiovisual Translation Studies; drag queens.

-------------------------------------

recibido en enero de 2021 aceptado en mayo de 2021

-------------------------------------

1. introduction

Drag lingo is the expression of a marginalised community. With clothes, make-up, wigs and lip-sync battles, drag lingo is one of the means that drag queens have at their disposal to create a shared identity in a society that has always discriminated against them. For historical reasons, drag culture is particularly strong in the USA, and drag lingo, which is an expression of camp talk, is mainly an English-based variety. American drag queens were involved in the Stonewall Riots in 1969 and the consequent Gay Liberation Movement. Their lives have been portrayed in 1990 American documentary film Paris Is Burning, directed by Jennie Livingston and dealing with New York drag ball culture. Today, American drag queens have acquired great visibility thanks to RuPaul’s Drag Race (henceforth RPDR) and inspire many other artists around the world with their professionality, competence and accuracy. RPDR is a reality television series led by RuPaul Charles —allegedly the most popular American drag queen today, who reached stardom in 1993 with her song Supermodel (You Better Work)— in which a group of drag queens compete for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar”. The programme was first launched on the American queer channel Logo TV, and then on Netflix, where it has been provided with subtitles and voice-over in several languages. The show has been exported abroad with glocalised versions, such as Drag Race Thailand (2018-present), The Switch Drag Race (Chile, 2015-present), RuPaul’s Drag Race UK (2019-present), Drag Race Canada (2020), Drag Race Australia (2020); a Brazilian version was announced in 2017, but has not been launched so far. For the time being, Spain is not actively participating in this cultural phenomenon; however, in December 2020 the castings for a Spanish version of the show have been opened and Drag Race España is expected to premiere in Summer 2021, twelve years after the first appearance of the show in the USA. It does not mean that dragqueenism has not existed in Spain in the meantime; it is its social recognition and acceptance to be at a different level when compared to the American phenomenon. Drag queens have a shorter tradition in Spain, which is reflected in the sociolect that is adopted in the voice-over to characterise them. American drag queens are provided with a specific lingo which is the product of decades of history; dictionaries have been published codifying this “secret” variety. As Harvey (1998: 295) maintains, when translating such sociolect “translators need to be aware of the comparable resources of camp in source and target language cultures.” Spanish drag queens do not have specific drag terms at their disposal, and the intertextual nature typical of drag lingo, being it strictly linked with the American culture and society, is difficult to convey in translation.

2. Aim and methodology

This article intends to analyse and comment on the translation choices made to characterise drag queens in the Iberian Spanish voice-over of RPDR, Seasons 8 (2016), 9 (2017) and 10 (2018)1. This study can be considered —to my knowledge— one of the first attempts to discuss drag lingo in a translation context. A similar work has already been published by Villanueva (2015), who compared the Netflix Spanish subtitles and the Venezuelan fansub of RPDR, Season 6, episodes 1 and 2. Further research should be done in order to foster insights on a conceptual and theoretical level.

The first sections of this work will deal with the controversial figure of the drag queen, with particular reference to Judith Butler’s performative vision of gender fluidity, which will turn out to be fundamental to understand certain features of drag lingo, as well as the role that translation has when conveying gender from one culture to another. The social and cultural context of Spanish dragqueenism will be briefly investigated on the basis of interviews made to famous Spanish drag queens. It will provide some context to understand certain translation choices and the difficulty that the translators have to face when dealing with the re-creation of a Spanish drag lingo. This sociolect will be studied mainly on the basis of a framework idealised by Keith Harvey (1998, 2000, 2002) to analyse fictional camp talk, but also on the basis of other linguistic features which depart from camp talk itself and are peculiar to drag lingo only. The main sections of this article, therefore, will focus on the analysis of the Iberian Spanish voice-over, focusing solely on the dialogues where the target text (TT) departs significantly from the source text (ST) in an attempt to characterise drag queens and provide them with a Spanish sociolect. Furthermore, this study seeks to establish how and how much drag lingo has in common with camp talk, and in what ways the former diverges from the latter.

3. Drag queens

The main online English dictionaries —Collins, Merriam-Webster and Oxford English Dictionary— all agree on the definition of who a drag queen is: a usually gay man who dresses like a woman and impersonates female characteristics for public entertainment, especially to caricature stereotypically vampish women. Oostrik (2004) maintains that drag queens’ femininity is a performance of an exaggerated display of gender that ridicules restrictive sex roles and sexual identification. In Workin’ It! (2010: 9), RuPaul declares that “drag queens are essentially making fun of the roles people are playing, [..] and have become experts at parody, satire, and deconstructing social patterns”. Performance and parody, therefore, are two fundamental aspects of drag culture. In Gender Trouble (2006), Judith Butler mentions drag queens as an example to explain gender performativity; in light of her theory, gender is a cultural code that can be performed, imitated and parodied, showing that it lacks a stable nature. She argues that, unlike biological sex, gender identities are not pre-existing attributes of individuals but are created with the repeated actions that an individual performs. Using Butler’s words, “gender is the cultural meanings that the sexed body assumes; [..] what we take to be an internal essence of gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylisation of the body” (Butler, 2006: 9). To put it another way, gender is performative, and behaviour, physical aspect, clothes, manners and language all play a significant role in gender performance. Drag queens do not recognise themselves within the binary, heteronormative sex and gender systems; drag queens are non-binary individuals, in the sense that despite being (mainly) biologically men —even though there are examples of transexual people doing drag, even within RPDR, such as Peppermint (RPDR, S9)—, the gendered stylisations that they make of their bodies do not correspond to “heteronormative men”, nor can they be considered “heteronormative women” just because they act like such. Quite the opposite. Drag queens cannot be classified within the heteronormative system, and their representation of femininity is, itself, inauthentic and exaggerated. No women act, talk, wear clothes and make-up like drag queens do. Peppermint declares that “the entire point of drag is to give the middle finger to rules of gender”. Nevertheless, dragqueenism and heteronormativity are not such distant concepts as one might think; drag queens base their performances on parodying heteronormativity. Thus, as Villanueva (2014: 3) maintains, dragqueenism is the means through which drag queens legitimately gain access to heteronormative space, thus underlying the fact that drag culture implies heteronormativity and vice versa.

3.1. Dragqueenism in Spain

Unlike in the USA, Spanish drag queens’ social condition is considerably different, and the definitions that the main Spanish dictionaries provide is a signal of it. The Spanish dictionary Clave defines the loan word “drag queen” as “travesti que va vestido con ropa que llama mucho la atención2”, whereas in Diccionario de la RAE, the English term “drag queen” has been replaced by the lemma “reinona” —keeping the gender inversion of the terms “queen”, commonly attached to women but used to refer to men among drag queens —and is defined as “hombre, generalmente homosexual, que se disfraza de mujer de una manera muy llamativa3”. Both definitions are considerably naive and reflect the still primitive status of recognition of dragqueenism in Spain. In an interview4 published on Youtube, Spanish drag queen Auriel Rec declares that “España no está preparada todavía. […] si sacamos la cabeza del núcleo, la gente no está preparada5”; Killer Queen– apparently one of the future contestants in Drag Race España (2021) —states that

ser drag queen en España es algo complicado porque todavía no es tan mainstream como en otros lugares. [..] Creo que en el ambiente somos súper queridas […], pero todavía es complicado ir de drag por la calle a la luz del día. [..] Falta dar tiempo para que la gente vaya evolucionando su pensamiento y adaptándolo y que el drag se vaya normalizando6;

Libertad Montero maintains that “la etiqueta drag queen en España está muy denostada, [...] es como lo peor de lo peor7”; to conclude, La Loli affirms that “aún hay mentes muy cerradas de la España profunda que se escandalizarían por nada. Somos un país muy abierto, pero sigue habiendo mucha gente que no acepta al colectivo8”. A more exhaustive definition of drag queen —although still too naive— can be found only in Diccionario gay-lésbico (Rodríguez, 2008), which is, nevertheless, a specialised Spanish dictionary of queer language: “hombre homosexual que viste con ropa de mujer y exagera el rol femenino que siente como propio con fines de entretenimiento. Cuando actúa públicamente, sus representaciones están dirigidas a un auditorio gay y lésbico”.9 This definition goes beyond the mere physical appearance and flamboyance of drag queens, and acknowledges their social and cultural commitment against the heteronormative system.

4. Drag lingo

From a linguistic perspective, Anglophone drag queens share a common sociolect, which defines their social group. Drag queens are members of a speech community, a group whose members are “people who have habitual contact with each other and have developed a shared use of the language, with a common lexicon and language practices” (Ranzato, 2012: 370). Harvey (1998: 305) acknowledges that language —in his study, camp talk— has an active role in the elaboration of gender identity. Citing Meyer (1994), he declares that

contemporary sexual identities ultimately depend on “extrasexual performative gestures”. [..] For, if the fact of sexual activity itself between people of the same gender appears to be the sine qua non for the (self-) attribution of the labels “gay” or “lesbian”, it is also true that such activity is actually absent from view and only present through the work of other extrasexual signifying practices which thereby become linked to it metonymically.

In RPDR, the contestants use their sociolect both when they are in drag and when they are out of drag. Adore Delano (S6E10) makes specific reference to drag lingo, while teaching a straight guy how to act like a drag queen:

-Adore Delano

I’ll beat your face. It’ll be hot.-Straight guy

You’re gonna beat my face?-Adore Delano

Yeah, that’s what we say. “Oh, she’s beating her face” means that she’s doing, like, a good job on doing her makeup. It’s lingo.-Straight guy

“I’m gonna beat your face” means something completely different.

Drag lingo can be considered, in part, an expression of the “umbrella” variety known as camp talk, which, according to Bronski and Core (1984), originated in the late nineteenth century as a secret homosexual code used for communicating among gay people who were forced to mask their, at that time, illegal sexual identity. Likewise, Harvey (2000) maintains that camp talk was one of the means that gay men had at their disposal to create subculture solidarity. Medhurst (1997: 29) has declared that camp “is the way gay men have tried to rationalize, reconcile, ridicule and wreck their own specific relationships to masculinity and femininity”; this controversial mixture of masculine and feminine linguistic features reflects the social and cultural project that drag queens endorse. Barrett (1995) adds that drag queens convey queerness “by skilfully switching between a number of linguistic styles and forms that stereotypically tend to denote other identities” (in Kulick, 2000: 25). In her opinion, drag lingo reflects the juxtaposition of contrasting characteristics that define drag queens themselves. For its fluid nature, camp talk can be compared to Butler’s vision of gender, in that both are unstable, unexpected, and performative. Babuscio (1993: 24) is of the opinion that

if “role” is defined as the appropriate behaviour associated with a given position in society, then gays do not conform to socially expected ways of behaving as men and women. Camp, by focusing on the outward appearances of role, implies that roles, and, in particular, sex roles, are superficial —a matter of style.

As will be shown in the following sections, drag lingo might be considered a mixture of antithetical linguistic features. Keith Harvey (2000) has developed a framework for identifying and analysing camp talk, according to which, it results from four semiotic strategies:

- Paradox, which is based on

- incongruities of register and co-occurrence of explicitness and covertness;

- co-occurrence of high culture and low experience;

- Inversion of

- grammatical gender;

- expected rhetorical routines and established value system;

- Ludicrism, based on

- Puns (co-presence of two meanings) and wordplays;

- double-entendre (co-presence of two meanings, one of which is always sexual);

- Parody, based on

- aristocratic mannerisms

- use of French;

- femininity

- innuendo (indirect and allusive manner);

- hyperbole;

- exclamation;

- vocatives.

Drag lingo, however, departs somewhat from camp talk as it was described by Harvey (2000), to the extent that other linguistic features can be found which specifically define drag lingo. In addition to the features of camp talk, drag queens tend to use expressions coming from:

- drag ball lingo, which became popular with the documentary film Paris Is Burning (1990); this variety has strong Afro-American linguistic features. It is mainly based on the appropriation and re-semantisation of standard words to create a secret code defining the drag community. In the dialogue shown above between Adore Delano and the straight guy, for instance, the standard verb “to beat” has been reconceptualised as a specific drag term meaning “to put make up on”;

- extreme creativity, such as the creation of neologisms based on wordplays with drag queens’ names (e.g. “RuVeal” for “reveal”, “RuSical” for “musical”, “RuPaulogise” for “apologise”, all based on the name RuPaul).

Drag lingo is highly creative, and this creativity reflects drag queens’ “ability to play with language, create inside jokes, catchphrases, and neologisms. […] They create their own vocabulary, one that sets them apart from mainstream English language users” (Libby, 2014: 52). Creativity is also to be found in the invention of witty insults–called “reading” in drag lingo (another instance of a standard term that has been reconceptualised to mean something else in drag lingo)–which is a much-rewarded practice among drag queens. Some of the most common insults in RPDR are “whore” and “bitch”, translated into Spanish as “zorra”, “perraca”, “cerda”, “guarra”, “marrana”, “pendón”, “mamarrachada”, “cacho perra”, “so puta”, “cabrona” y “pedorra”, all belonging to the semantic fields of prostitution, and the pejorative connotation attached to animal species, such as swine; it should be noticed the use of the female grammatical gender in Spanish, which is typical of drag lingo and camp talk in general. Using Brown and Levinson’s (1987) terminology, insults can be considered threats to an individual’s negative face, that is threats to one’s desire to be appreciated and approved of (59-64). A face-threatening act (FTA) is produced when this desire is not attended to, and the speaker does not care about the addressee’s positive self-image. In this respect, Harvey is of the opinion that “ambivalent solidarity” (1998: 301-303) is fundamental in the construction of a shared identity among non-binary people, since both the sender and the receiver of the FTA (generally based on homophobic insults) are reciprocally affected by it. He defines ambivalent solidarity as

a feature of camp interaction in which speaker and addressee paradoxically bond through the mechanism of the face-threat. Specifically, the speaker threatens the addressee’s face in the very area of their shared subcultural difference [..]. Consequently, the face-threat, while effectively targeting the addressee, equally highlights the speaker’s vulnerability to the same threat.

However, negative FTAs among drag queens work in a slightly different way, since they are not to be seen negatively; on the contrary, among drag queens the system politeness/impoliteness is inverted, and the more a drag queen is good at inventing impolite expressions, the more successful and esteemed she will be.

It should be borne in mind that the linguistic variety analysed in this article is a translation of a fictional representation of drag lingo. Audiovisual speech is non-spontaneous and prefabricated; it is inauthentic orality, a mere imitation of spontaneous spoken language (Pavesi, 2015: 7). Even though reality TV series leave much more room for spontaneous language than films, much of what is said during the dialogues between the contestants is partly based on a written canovaccio that they need to follow. Audiovisual speech is an inaccurate imitation of natural conversation, which has been scripted, written and rewritten, censored, polished, rehearsed, and performed. The actual hesitations, repetitions, digressions, grunts, interruptions, and mutterings of everyday speech have either been pruned away, or, if not, deliberately included (Kozloff, 2000: 18).

5. Voice-over and translation procedures

The originality of this work lies in the fact that it can be considered one of the first attempts to apply a methodology belonging to queer linguistics to Audiovisual Translation (AVT) Studies, with particular attention to the rendering of American-based drag lingo into Iberian Spanish. The audiovisual technique used is voice-over, which has been labelled the “ugly duckling” of AVT Studies (Orero, 2006), a “damsel in distress” (Wozniak, 2012: 211), an “orphan child” (Bogucki, 2013: 20). Díaz Cintas and Orero (2006: 477) conceive it as a “technique in which a voice offering a translation in a given target language (TL) is heard simultaneously on top of the source language (SL) voice”, and where “the [SL] volume is reduced to a low level that can still be heard in the background when the translation is being read”; voice-over “usually finishes several seconds before the foreign language speech does, (and) the sound of the original is raised again to a normal volume (so that) the viewer can hear once more the original speech”, and authenticity is enhanced. Unlike dubbing, therefore, lip-synchronisation is not required, which makes voice-over much cheaper, faster, and suitable for the translation of long-lasting TV series. According to Matamala (2019: 72), a leading figure in the study of voice-over,“in Spain, traditionally a dubbing country, documentaries are generally translated using a combination of voice-over [..] and off-screen dubbing”, and she adds that not only is this type of translation used in non-fictional audiovisual texts, but also in reality shows, as is the case of RPDR.

As has been stated earlier, this article approaches AVT Studies from a queer perspective. According to von Flotow et al. (2019: 296-312), questions concerning gender and AVT Studies date back only to the early years of the 2000s. Scholars working in this field are mainly concerned with the translation of Anglo-American audiovisual products into Romance languages, and they generally criticise the inability of the target languages to convey the gender markedness or unmarkedness of the source materials. The study of queer issues in AVT has been carried out mainly by Chagnon, 2014; De Marco, 2009-2016; Lewis, 2010; Ranzato, 2012-2015; Villanueva, 2015. Scholars agree on the fact that Romance languages lack the queer terminology available in English, thus creating weak, if not inexistent translations, where non-binary elements are either omitted or rendered heteronormative. In line with Butler’s performative nature of gender discussed above, translation is a gender-constructing activity. Each culture constructs gender in its own way and with its own means. Bauer (2015: 2) states that “translation serves as a framework for analysing how sexuality travels across linguistic boundaries”, and “offers compelling new insights into how sexual ideas were formed in different contexts via a complex process of cultural negotiation”. If American drag queens create their gender also through their language, then the same is to be done by the translators in the Spanish version, adapting the construction of drag queens’ gender to the Spanish language, culture and society. Harvey (1998: 296) states that the translation of camp talk implies not only close attention to the ST and source culture, but also–among other factors– “the existence, nature and visibility of identities and communities predicated upon same-sex object choice in the target culture; the existence or absence of an established gay literature in the target culture”. It follows that the visibility of drag queens in Spain, as well as the existence of an established literature showing drag lingo are fundamental aspects that the translators have to be aware of. A translation implies a certain degree of localisation, the inevitable addition of localised elements to the TT so that the ST can be easily understood by the target audience. RPDR is a good example of a glocalised product, that is a product that is spreading all over the world–globalised–but that needs to be localised to be consumed.

The analysis of the voice-over is conducted mainly on the basis of Ranzato’s (2015) framework for translating culture specific references (CSRs), which is partly based on a previous taxonomy by Díaz Cintas and Remael (2007). Ranzato’s classification is particularly useful in this study, where it has been adapted to the analysis of the translation of linguistic elements marking drag lingo into Iberian Spanish. The use of Ranzato’s framework, despite being conceived for the investigation of CSRs, has been applied to this study because American drag lingo is permeated by CSRs, which the translator has to face. This article does not intend to investigate the procedures adopted in the voice-over in toto, but only those that are relevant to the characterisation of drag lingo. They are:

- Loan: the unaltered repetition of an element of the ST;

- Lexical recreation: a neologism in the ST is translated with a neologism in the TT;

- Creative addition: Ranzato (2015: 96) states that “this category can be considered typical of dubbing; [..] the fact that the original soundtrack can be heard renders the implementation of this strategy riskier in subtitling and voice-over translation”;

- Official translation: Ranzato (2015: 85) defines it as “a ready-made strategy. It may involve a certain amount of research on the part of the translator to find the established equivalent of an element in the target culture [..] to create an impression of thoroughness in a translation”;

- Explicitation: it is an explanation of a fuzzy element of the ST;

- Generalisation by hypernym: a specific element of the ST is replaced by a hypernym;

- Substitution: replacement of a lesser-known element of the ST with one more popular for the target audience;

- Elimination: an element of the ST is eliminated.

Two further tendencies have been added to Ranzato’s framework, on the basis of the trends found in the voice-over of drag lingo in RPDR:

- Standardisation: a non-standard feature of drag lingo is translated in a standard way;

- Gender rendering.

The analysis of para-verbal features of drag lingo is beyond the scope of this article. Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that a fundamental feature associated with camp talk is the speaker’s voice. Pérez-González (2014: 199-200) has acknowledged the “semiotic potential of the para-verbal”, that is, intonation, accents, rhythm, speed and pausing, but also breathy voice, wide ranges in pitch, extended vowels, and sibilant duration, which, most of the time, seem to index gayness. This work focuses mainly on the creative rendering of (semi-)homophony, drag terms, references to pop culture and grammatical gender.

6. Translation analysis

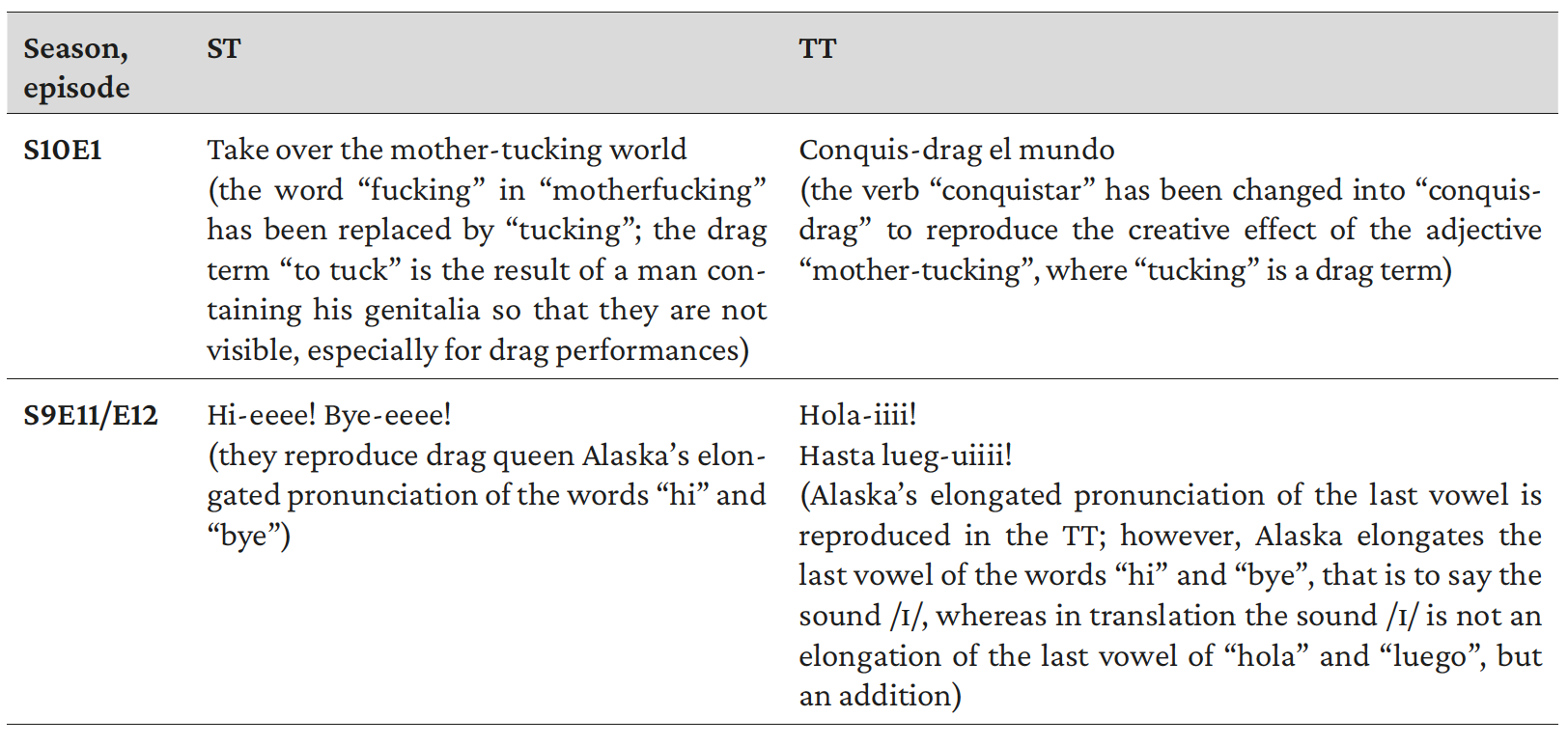

6.1. (Semi-) Homophony

One of the most common linguistic features of RPDR is the creation of new words on the basis of (semi-) homophony. A homophone is a word that is pronounced (almost) the same as another word but differs in meaning and/or spelling. Homophones are often used to create puns and deceive the receiver, or to suggest multiple meanings. Puns and wordplays are particularly common in Anglo-American camp talk, where the multiplicity of linguistic influences affecting English offers considerable complication in spelling, meaning and pronunciation compared with other languages. Unlike camp ludicrism, drag queens tend to make more abundant use of wordplays on the basis of (semi-) homophony, with extremely creative inventions like “Ru-sical” for “musical”, “RuPaul-ogise” for “apologise” which have been mentioned in the previous sections. (Semi-) homophony has been rendered using the following procedures:

- Creative addition: (semi-) homophones are rendered with creative additions, as in “do-nut come for me because I’ll destroy you. Get it, do-nut?” > “si me atacas, te dejaré el culo así. Lo pilláis, no?” (S8E1). While introducing herself, the contestant Kim Chi exalts her “reading” qualities; she speaks with a doughnut in her hands, and creates a wordplay on the basis of the homophonous relationship existing in English between the negative auxiliary “do not” and the noun “donut”. This wordplay does not work in Spanish, and in the voice-over the visual channel is exploited – the drag queen recreates the shape of the doughnut (symbol of the anus) with her fingers – and accompanies it with the word “culo” and the deictic “así”. In the Spanish version, Kim Chi uses a far more explicit reference to the sexual component of the double entendre, thus eliminating its indirect nature. Harvey (2000: 250) states that “double entendres depend on a decoding of an implicit meaning behind the utterance. [..] through the double entendre the speaker can intentionally say something sexually explosive while appearing to say something unremarkable”. In this case, the Spanish translation has relied mainly on the exploitation of the visual channel.

- Loan words: a further common linguistic feature in RPDR is the creation of neologisms on the basis of semi-homophony with the first syllable of the name RuPaul, such as “déjà-Ru” instead of “déjà-vu”, and “Ru-mix” instead of “remix”. The previous terms have been kept as such in the voice-over, and are considered loan words – words that transmigrate from a language into another language without being translated. After all, terms such as “remix” and “déjà vu” are perfectly usable in Spanish, and the wordplay existing in the ST can be maintained also in the TT. Loan words are particularly useful when the translator intends to give the TT a touch of foreignization. Furthermore, according to Harvey (2000), camp talk is characterised by the use of foreign languages. Other loan words in the voice-over are “drag”, “queer” and “sass”, which can be found everywhere in the three seasons under scrutiny.

-

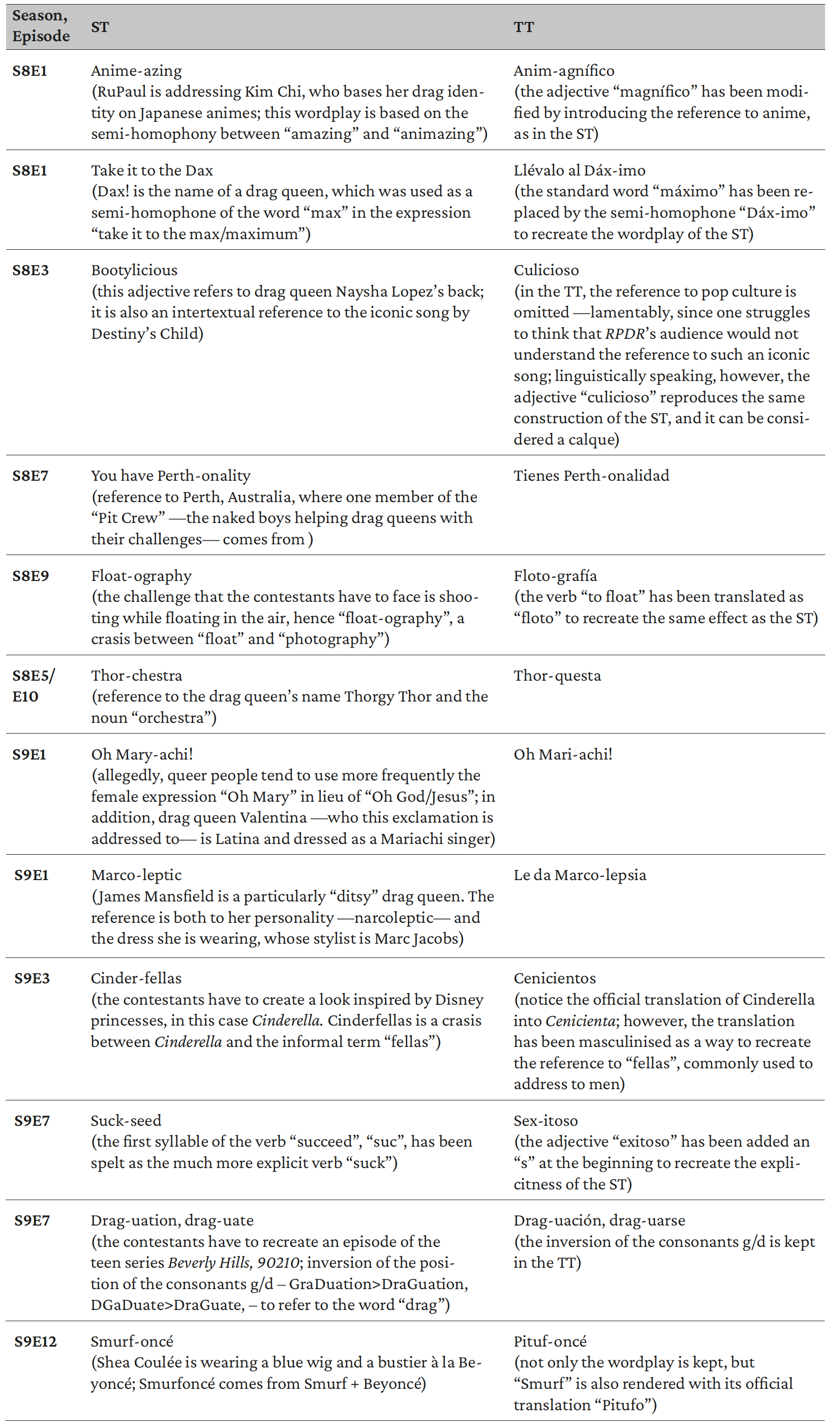

Lexical recreation: the creativity of the (semi-) homophones in the Anglo-American drag lingo has also been rendered in Spanish with the strategy known as lexical recreation, that is the creation of a new word in the TT to convey an invented word in the ST. When at the end of episode 4, Season 10, drag queen Blair St. Clair walks down the catwalk in a black and white striped dress, RuPaul declares “her stripes are vertical and whore-izontal”. The adjective “whore-izontal” is a wordplay based on the homophony between the morpheme “hor-” in “horizontal” and the explicit word “whore”; in the voice-over it was rendered as “zorr-izontales”, which follows the same procedure of the ST and is, for this reason, an example of lexical recreation. The Spanish morpheme “hor” in “horizontales” is replaced by the explicit term “zorra”, following the same procedure as in the ST. More precisely, “zorrizontales” and “horizontales” are not perfectly homophonous, but they keep the explicit reference to prostitution, which is a common term of address among drag queens. Other instances of this technique can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Lexical recreation

- Standardisation: other English homophonous expressions have been translated with a neutral, standard realisation, with the consequent loss of the creativity of the ST, as in “she-lebrities” > “famosillas”, “she-ro” > “heroina”, “her-story” > “historia drag”. In these three cases, the exaggerated gender crossing used by RuPaul, based on the substitution of morphemes that remember male pronouns and adjectives with their female counterparts–“HE-ro” > “SHE-ro”–is lost in translation. The following monologue created by RuPaul (S10E1) is emblematic of this procedure. In the ST, many verbs, adverbs and adjectives have been created by exploiting the names (in italics) of some of the most popular contestants in the show. All the references have been standardised in the TT:

don’t wanna Jinkx you, but Monsoon you’ll BeBe sharing the spotlight with queens that would Raja you were dead. You need to go above and Bianca. For the crown you must vie, or let the other queens steal your thunder. So don’t settle for a Bob. The drag with the best hair is closest to, yes, God! and if at first you don’t succeed, Tyra, Tyra again. So will you be America’s Next Drag Superstar, or the first to Sasha away?

“Monsoon” stands for “soon”, “BeBe” for “be”, “Tyra” for “try”, “Sasha” for “Sashay”. “Sashay away” is usually uttered by RuPaul when eliminating one of the contestants. Its translation in the Iberian Spanish voice-over is “desfila hacia la salida”, which, in this monologue, was chosen to translate also “Sasha away” (Sasha is the name of a drag queen), thus eliminating the wordplay “Sasha/sashay away”. Except for a good rhyme scheme, the TT does not convey the great effort made by RuPaul to create her monologue.

No quiero traerte malasuerte, pero lo que voy a decirte va a dolerte, porque pronto la fama tendrás que compartir con otras reinas que no te dejarán vivir. Sin descanso deberás luchar si la corona te quieres llevar, o puedes abandonar y otras reinas podrán ocupar tu lugar. No te conformes con poca cosa. La drag con el major peinado se ganaría al jurado. Y aunque no ganes una vez, sigue intentándolo otra vez. Serás la próxima Estrella Superstar de América, o la primera en desfilar hacia la salida? - Explicitation: double entendre, according to Harvey, is one of the features of camp talk. Double entendre is based on the co-presence of two meanings, one of which must be of sexual domain (Harvey, 2000: 250). As the word “entendre” suggests, it needs to be implicit to work. What happens in the TT is that it is made explicit, as in “Edgar Allan Hoe” (allusion to the word “whore” in a non-rhotic pronunciation) > “Edgar Allan Puta” (S8E9). The expression refers to the look chosen by Kim Chi, which is inspired on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. Since the double entendre is made explicit, the indirect effect is completely lost in translation.

- Addition: sometimes more information is added to convey a homophonous expression, such as “thanks for Cher-ing” > “gracias por el toque Cher” (S8E9), addressed to Naomi Smalls, where the verb “Chering”, wordplay based on the homophony between Cher (the singer) and the verb “share”, has been rendered by adding more information.

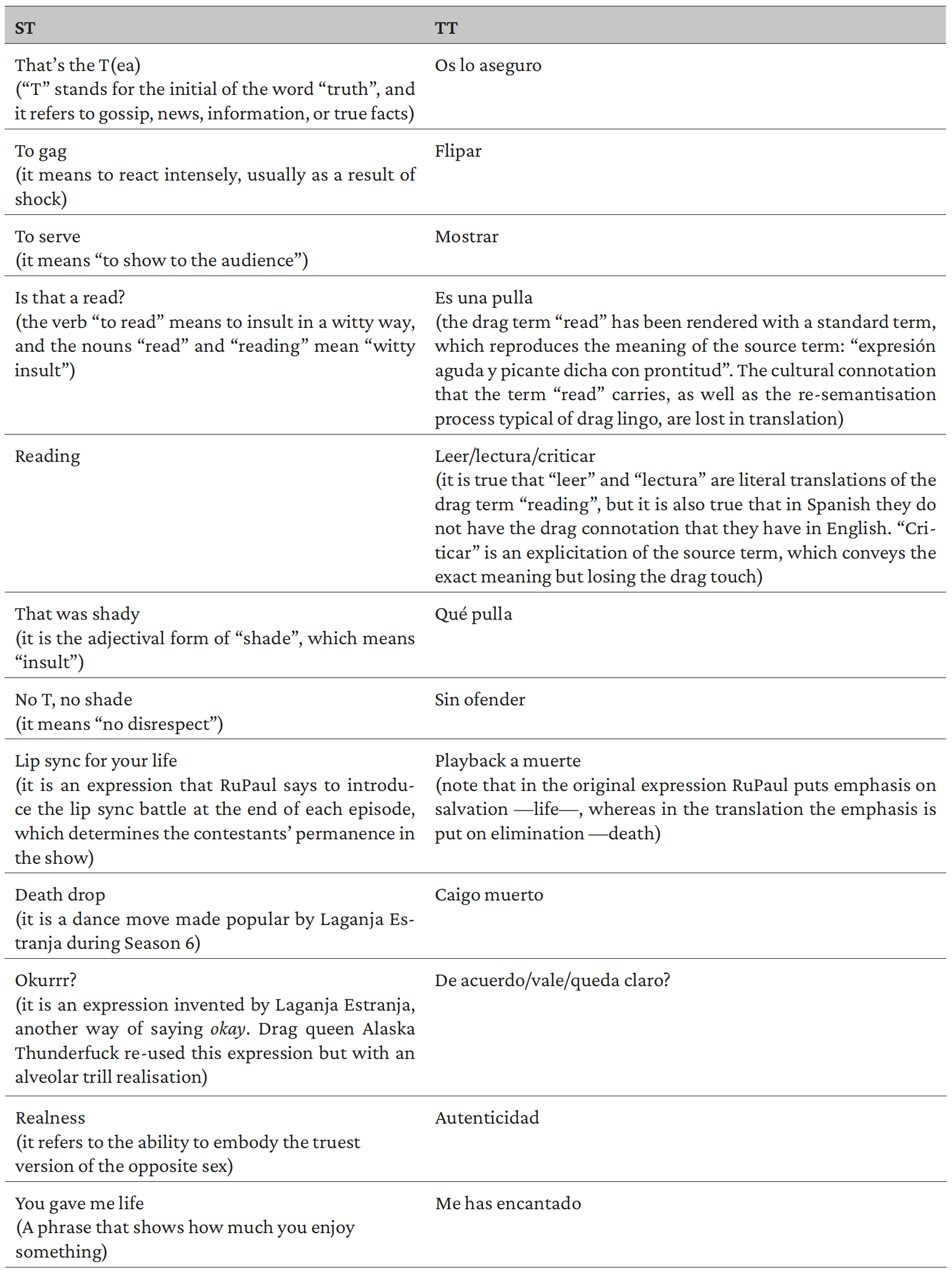

6.2. Gender rendering

Besides homophony, drag queens in RPDR create their identity through gender inversion. They refer to themselves using words, pronouns and adjectives commonly associated with women, which is a typical feature of camp talk (Harvey, 2000). Unlike camp talk, drag lingo takes gender inversion to the extreme by creating words such as herstory or shero, where his in “history” and he in “hero” are inverted as though they were masculine forms. This extreme gender inversion is not to be found in camp talk, but is rather specific to drag lingo. Three different solutions have been found in the translation of gender, as is shown in Tables 2-3-4. It should be borne in mind that English and Spanish are based on two different grammatical gender systems: English is a language showing pronominal gender only in third-person singular pronouns and adjectives (Corbett, 1991), whereas Spanish is a Romance language showing grammatical gender, that is adjectives, articles, past participles, determiners have their own grammatical gender expressed through inflectional morphemes.

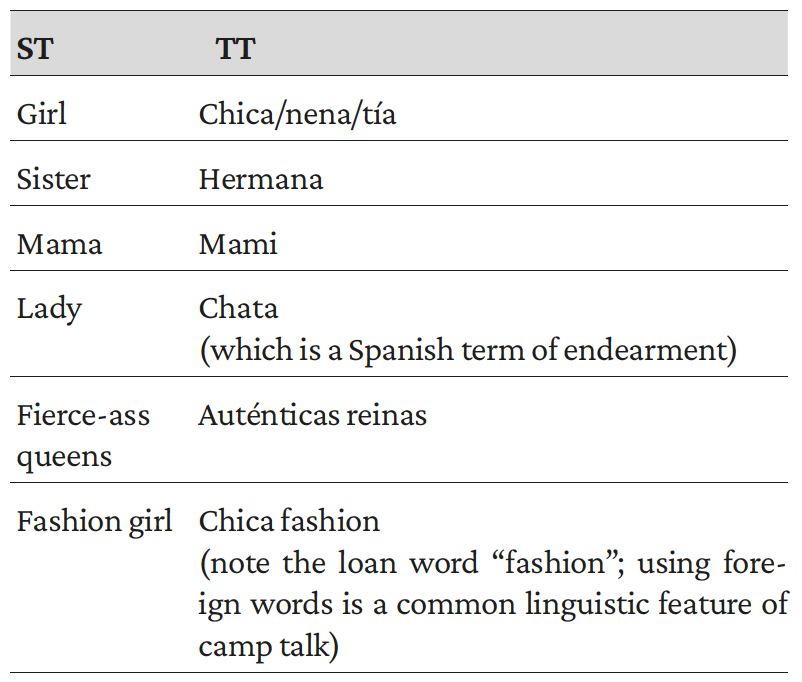

Female > Female

The following expressions, commonly addressed to women in English, have kept the feminine gender in translation (Table 2). These examples can be found everywhere in the three seasons under scrutiny, since they are common terms that drag queens use to address to each other.

Table 2. Gender rendering - female > female

Neutral > Female

In the TT there is a tendency to adopt the female gender for English gender-unmarked adjectives, thus enhancing gender crossing in translation (Table 3). These examples, as for the previous ones, can be found everywhere in the three seasons under scrutiny. They are mainly specific terms of drag lingo. These secret terms are mainly explained in the Spanish translation, thus losing their secretness. The translations listed in Table 3 are mere definitions of what the drag terms mean.

Table 3. Gender rendering - neutral > female

Male > Female

In a few cases, words that in the ST are used to refer to men are feminised in the TT, as is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Gender rendering - male > female

6.3. Drag terms

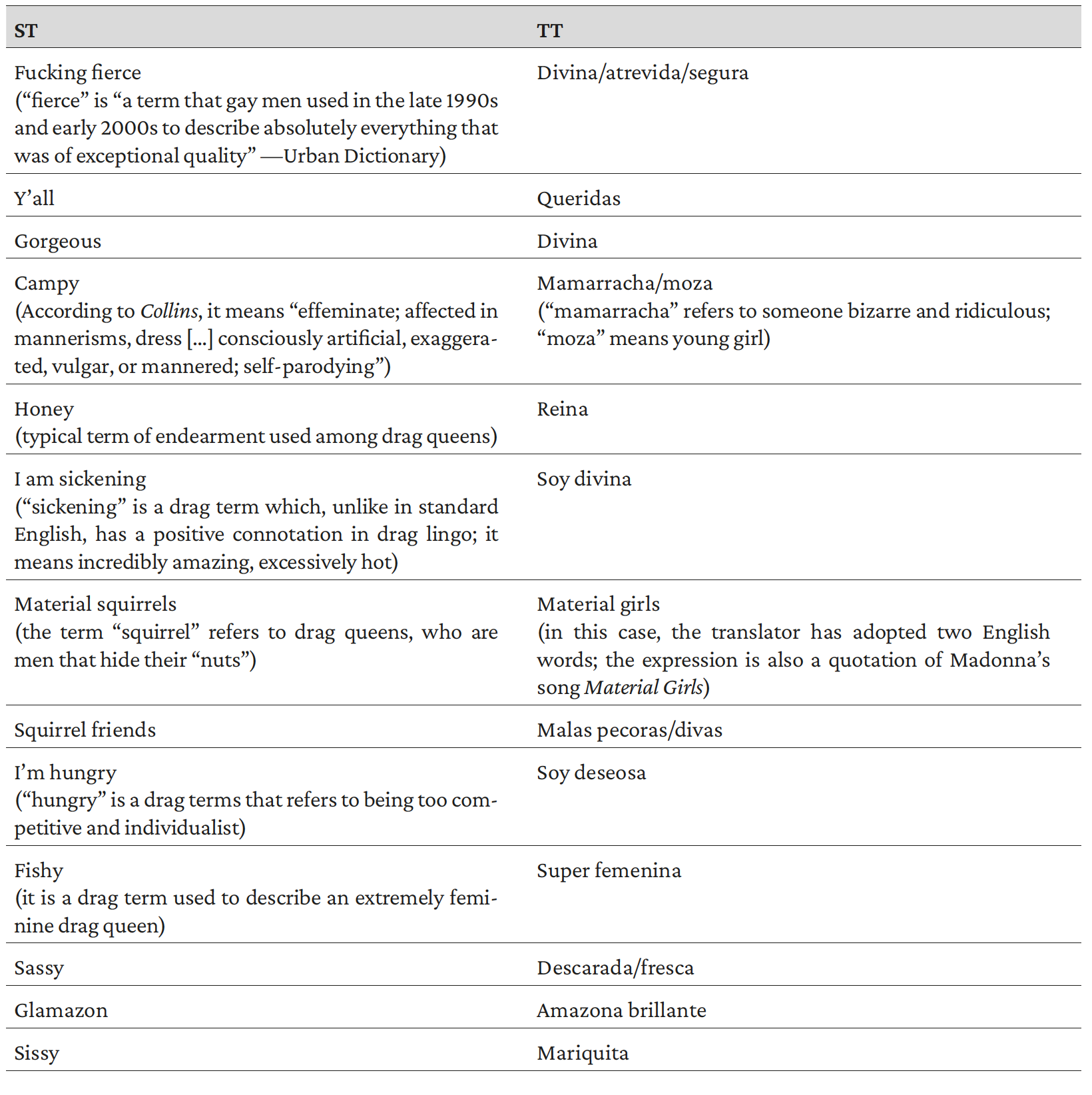

The analysis of Table 3 has anticipated the discussion of drag terms. In this section, they —and their translations— will be investigated more thoroughly, as elements that define drag lingo, and make it partly depart from camp talk as has been defined by Harvey (2000, 2002). “Sickening”, “fierce”, “squirrel friends”, “glamazon”, “fish(y)”, “hungry” are all terms belonging to a long drag tradition in the Anglophone countries. These terms are not to be found in camp talk, but they are rather specific to drag lingo, which reflects the drag ball culture that drag queens have shared and that has become gradually more mainstream thanks to the documentary film Paris Is Burning (1990) and RPDR (2009-present). Spain has not such a strong drag culture and, consequently, translators have not much specific lexicon to use. They have two options at their disposal: lexical recreation (as shown in Table 5) and standardisation (Table 6).

-

Lexical recreation

The Spanish translators, if possible, tend to convey the extreme creativity of drag terms by inventing new Spanish words to reproduce the originality of the ST (lexical recreation, Table 5)

Table 5. Drag terms - Lexical recreation

- Standardisation

The drag terms in Table 6 are frequent in all the episodes of the three seasons. They are consistently repeated and are at the basis of drag lingo. They have been standardised in the TT.

Table 6. Drag terms – Standardisation

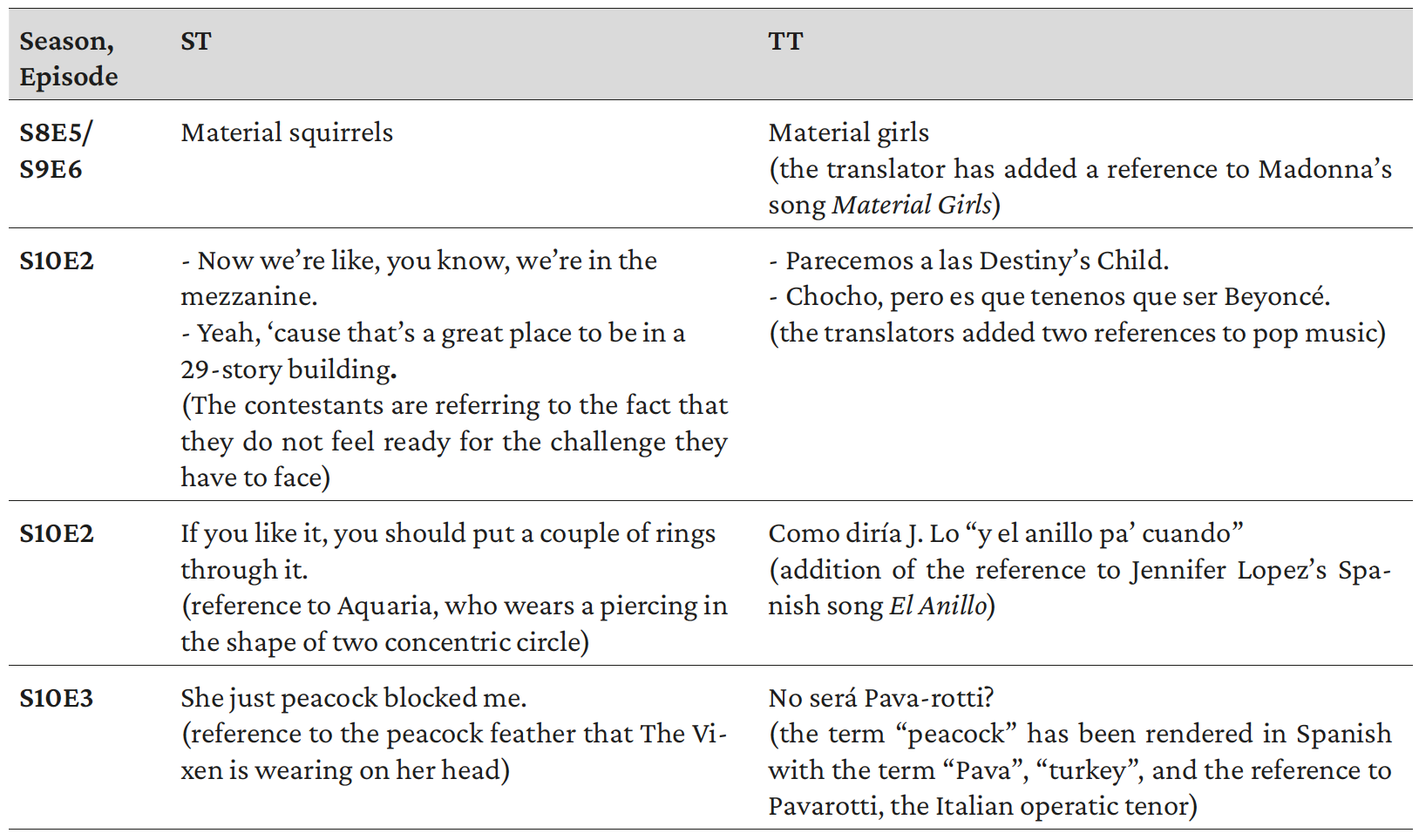

6.4. References to pop culture

Similarly to camp talk, drag lingo is characterised by citationality (Harvey, 2002). However, citationality in camp talk and drag lingo differs mainly in their sources. Harvey (2000) is of the opinion that

camp characters like to describe their experiences —particularly the mundane or seedy— with reference to the culturally enshrined values of great art. Opera, with its vocabulary of grand gesture and highly wrought emotional display, is a favourite source of allusion. (245)

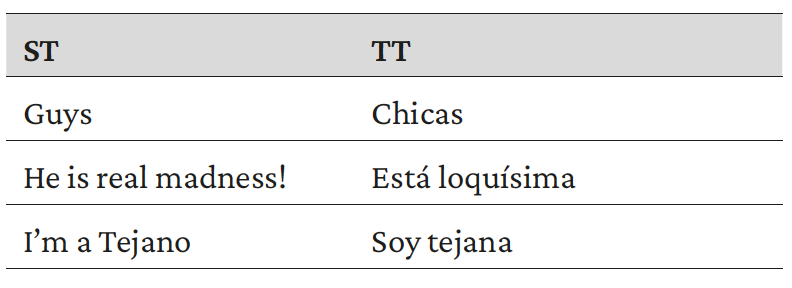

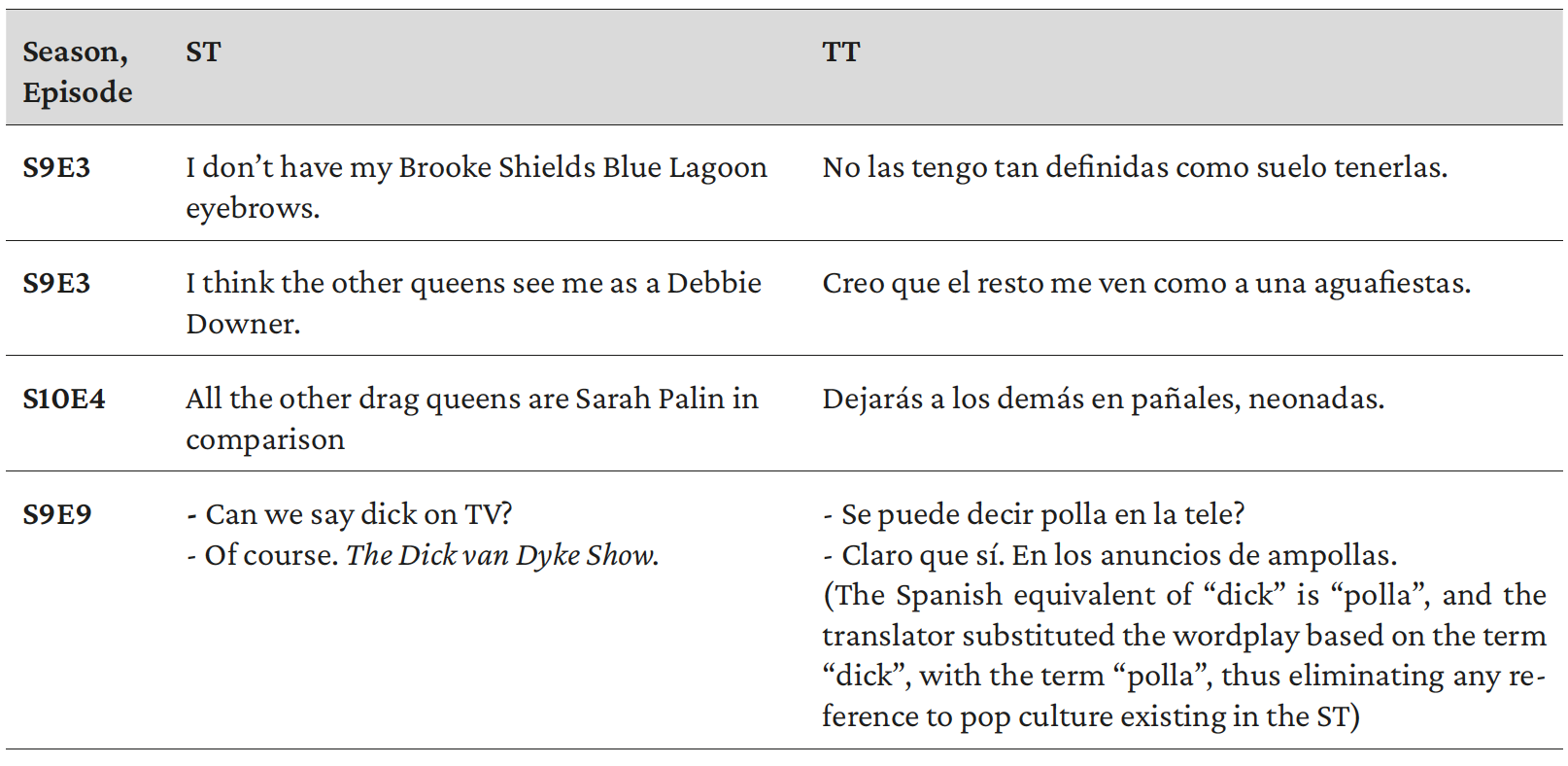

Unlike camp talk, drag lingo tends to prefer citationality from popular culture, mainly pop stars, pop music, series and films. References to pop culture are consistent throughout the seasons, and in the voice-over they are rendered with the following strategies:

-

Official translation (Table 7)

This procedure is particularly fruitful when translating intertextual references since, according to Ranzato (2015: 103-104) “i t usually contributes to create an impression of thoroughness in a translation and favours the prompt response by the target audience to the associations triggered by the element.”

Table 7 Citationality - Official translation

- Addition

References to pop culture sometimes are added (Table 8) in the TT, probably as a means of compensation in the characterisation of drag lingo.

Table 8 Citationality - Addition

-

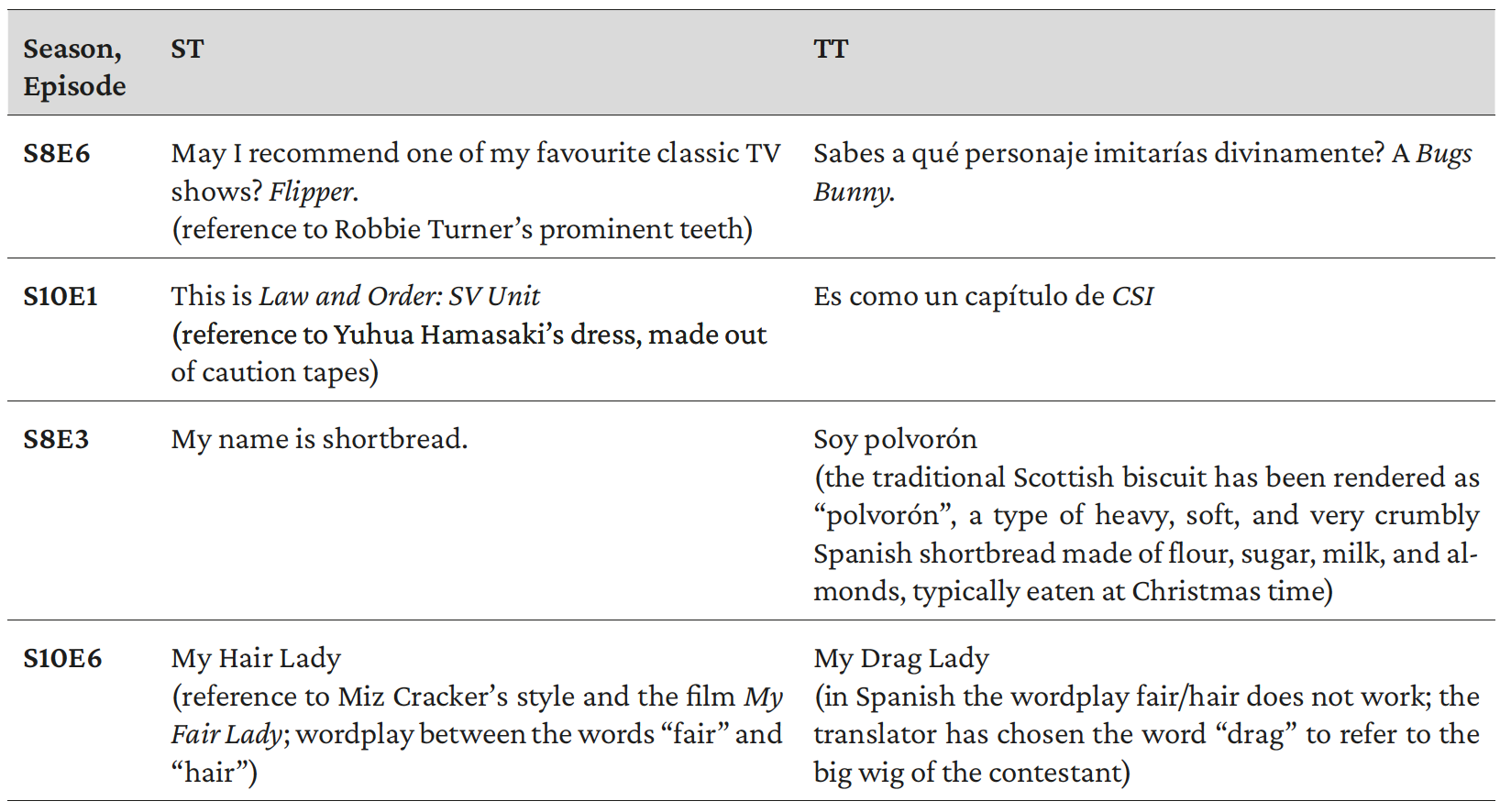

Substitution

Other references to Anglo-American pop culture that are too specific to the American society have been replaced by other pop references, as Table 9 show:

Table 9 Citationality - Substitution

- Generalisation – a specific element that is not easily recognisable in the target culture can be generalised, such as “Judy Jetson” > “Los Supersónicos” (S10E1; Judy Jetson is the protagonist of The Jetsons, which was translated as Los Supersónicos in Spanish);

- Explicitation – a kind of amplification used when the target audience needs more information to understand culture specific references, as in “Annie Oakley” > “Ana de la pradera” (S10E2; Asia O’Hara is wearing a dress inspired on Western films), and “Dominique Deveraux wannabe” > “Te has querido Dominique de La Dinastía” (S8E3);

-

Elimination – when a culture specific element cannot be understood by the target audience, and is irrelevant to the dynamics of the text, the translator can decide to omit it, as in Table 10.

Table 10 Citationality - Elimination

7. Conclusions

This article has sought to bring two different disciplines into relationship, namely Queer linguistics and AVT Studies. This has been possible because of the many similarities that the concepts of gender and translation have in common. The originality of this study lies in the fact that it can be considered one of the first tentatives to discuss drag lingo and its translation in Spanish. As has been mentioned in the initial sections of this article, gender and translation share their performative nature, and following Butler’s theory (1990), both gender and translation are social and cultural constructs. It follows that the TT is not a mere copy of the ST, but it is rather a re-construction of it into another language, culture and society. To put it another way, the TT is a re-writing of the ST, “depending on the historical and social contexts in which the translations and the translators are placed” (De Marco, 2012: 41). For Lefevere (1992: 9), translation is the “most obviously recognizable type of rewriting”, and the translator manipulates the ST due to ideology and the dominant poetics in the target culture.

Anglo-American drag lingo is deeply rooted in the American society and its translation into other languages should take into account the existence (or not) of such sociolect in the target culture, as well as the social conditions and visibility of drag queens in the target society. De Marco (2012: 25) declares that “translation is a socio-political activity that cannot be untied from the ideological constraints of its surroundings and practitioners.” As Spanish drag queens have agreed on, dragqueenism in Spain is at a completely different level of recognition when compared to its American counterpart. It follows that the rendition of drag lingo into Spanish is a major challenge that the translators have to face. Homophones, specific drag terms, references to pop culture and grammatical gender are among the most problematic issues that the translators have to deal with in the production of the Spanish voice-over. Translating such a localised sociolect, therefore, is extremely complicated. It is true that many typical linguistic features of drag lingo have been standardises, generalised or eliminated, many double-entendres have been made explicit, but it is also true that the effort of the Spanish translators to invent (whenever and wherever possible) new words and expressions is to be recognised. Creativity seems to be the general solution adopted by the translators. It is mainly expressed through the procedures of lexical re-creation and creative addition, which seeks to compensate the inevitable losses in the translation of American drag lingo. As Bassnett (2002: 4-5) has it, “the translator is a creative artist, an intercultural mediator and interpreter, a figure whose importance to the continuity and diffusion of culture is immeasurable”, and “it is up to the writer to fix words in an ideal, unchangeable form, and it is the task of the translator to liberate those words from the confines of their source language and allow them to live again in the language into which they are translated”. Double entendres, mainly expressed through the use of (semi-) homophones in the ST, are consistently made more explicit and vulgar. It is the case of “Edgar Allan Hoe”—with the double entendre and homophony “whore/hoe” and the reference to the surname Poe— which is translated as “Edgar Allan Puta”, where the double entendre disappears and the veiled sexual reference is made explicit; the same happens with “whor-izontal” —double entendre based on homophony between “hor-izontal” and the noun “whore”— translated as “zorr-izontales”, where the subtle double entendre (especially in the English spoken language) is made explicit with the use of “zorr-”, which is not homophonous with “hor-izontales”. In addition to this, the visual channel is exploited in the doughnut scene, where the wordplay based on homophony and double entendre between the negative auxiliary verb “do not” and the noun “doughnut” is substituted with an explicit, vulgar reference to the anal orifice, visualised by the doughnut itself. However, not only have the Spanish translators reproduced the typical creativity of Anglo-American drag lingo, but also the linguistic phenomenon called gender crossing, which reflects drag queens’ non-binary condition and parody of heteronormative society. Not only elements that are typically attached to women in the ST have kept the female gender in the TT, but neutral (e.g. adjectives) and male (he/his/him) elements in the ST have been translated as female in the TT. Therefore, there is evidence to say that gender crossing is enhanced in the Spanish version, which could be considered a form of compensation in the characterisation of the Spanish drag queens. References to pop culture, furthermore, have been increased in their quantity in the TT, with a tendency towards references to pop music by gay icons, such as Madonna, Jennifer Lopez, Destiny’s Child and Beyoncé.

A further issue that this study has tried to investigate is how and how much drag lingo diverges from camp talk as has been described by Keith Harvey (1998, 2000, 2002). Despite sharing most of its linguistic features with camp talk, drag lingo tends to intensify some of them. It is the case of gender crossing, which according to Harvey affects proper names and grammatical gender markers, but that in drag lingo tends to regard also morphemes resembling male grammatical elements, such as “he” in “hero”, which becomes “shero”, or “his” in “history”, which becomes “herstory”. Citationality is another feature that drag lingo has in common with camp talk; however, although the latter tends to make intertextual references to high culture —such as opera—, drag lingo seems to prefer popular culture as a source of references, such as pop music and singers, iconic television series and films. Ludicrism is also intensified in drag lingo; wordplays are typical of camp talk, but drag lingo is characterised by such an extreme use of creativity that new words are consistently created replacing morphemes with drag queens’ names (e.g. “RuPaulogise” for “apologise”, wordplay with the name RuPaul) or drag terms (“mother-tucking” for “mother-fucking”). Speaking of which, drag lingo differentiates from camp talk also in the use of drag terms —extensively discussed in the previous sections— coming from American drag ball culture. Finally, the reception of insults is another fundamental difference between camp talk and drag lingo. If insults are generally seen as negative elements in society, their reception is positive in drag lingo. The more drag queens are skilled at “reading” (deliver witty insults), the more they are esteemed by the audience and their colleagues. Face threatening acts —which are avoided in society as a form of respect for the others— are more than welcomed among drag queens.

Further research should be done on drag lingo in translation context. Spanish voice-over might be compared with subtitles; moreover, the Iberian Spanish translation– both voice-over and subtitles–might be compared with their Latin-American counterparts. In addition to this, in the future, it might be worth investigating the forthcoming Spanish version of the show, Drag Race España, and comparing the lingo that real Spanish drag queens speak–if they do speak a specific sociolect–and the “artificial” drag lingo as has been re-created by the translators and discussed in this article.

References

Anderman, Gunilla and Jorge Díaz-Cintas (2009): Audiovisual Translation. Language Transfer on Screen, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Babuscio, Jack (1977): “Camp and the gay sensibility”, in Richard Dyer (ed.), Gays and Film, London: British Film Institute, 40-57.

Baer, Brian James and Klaus Kaindl (2017): Queering Translation, Translating the Queer. Theory, Practice, Activism, New York-London: Routledge.

Barrett, Rusty (1995): “Supermodels of the world unite! Political economy and the language of performance among African-American drag queens”, in W.L. Leap (ed.) Beyond the Lavender Lexicon: Authenticity, Imagination, and Appropriation in Lesbian and Gay Languages, Buffalo-New York: Gordon and Breach, 207-226.

Bassnett, Susan (2002): Translation Studies, London-New York: Routledge.

Bauer, Heike (2015): Sexology and Translation. Cultural and Scientific Encounters Across the Modern World, Philadelphia-Rome-Tokyo: Temple University Press.

Boguzki, Lucasz (2013): Areas and Methods of Audiovisual Translation Research, Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Bronski, Michael (1984): Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility, Boston: South End Press.

Butler, Judith (2006): Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York: Taylor & Francis.

Cameron, Deborah and Don Kulick (2003): Language and Sexuality, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, Deborah and Don Kulick (2006): The Language and Sexuality Reader, London and New York: Routledge.

Chagnon, Karina (2016): Télé, traduction, censure et manipulation: Les enjeux politiques de la reception du discours queer, Presentation at 15e édition de l’Odyssée de la traductologie, Concordia University, Montréal.

Corbett, Greville G. (1991): Gender, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Core, Philip (1984): Camp: The Lie That Tells the Truth, New York: Delilah Books.

De Marco, Marcella (2009): “Gender Portrayal in Dubbed and Subtitled Comedies”, in Jorge Díaz-Cintas (ed), New Trends in Audiovisual Translation, Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 176-196.

De marco, Marcella (2012). Audiovisual Translation through a Gender Lens, Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi.

De Marco, Marcella (2016): “The ‘Engendering’ Approach in Audiovisual Translation”, Target, 28/6, 314-325.

Díaz-Cintas, Jorge and Aline Remael (2007): Audiovisual Translation: Subtitling, Manchester: St. Jerome.

Díaz-Cintas, Jorge and Pilar Orero (2006): “Voice-Over”, in K. Brown (ed), Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics 13, Oxford: Elsevier, 477–479.

Eckert, Penelope and Sally McConnel-Ginet (2003): Language and Gender, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Epstein, B.J. and Robert Gillett (2017): Queer in Translation, Routledge.

Franco, E., Anna Matamala and Pilar Orero (2010): Voice-Over in Translation. An Overview, Bern: Peter Lang.

Harvey, Keith. (1998): “Translating camp talk. Gay identities and cultural transfer”, The Translator, 4/2, 295-320.

Harvey, Keith (2000): “Describing camp talk: language/pragmatics/politics”, Language and Literature, 9, 240-260.

Harvey, Keith (2002): “Camp talk and citationality: a queer tale on authentic and represented utterance”, Journal of Pragmatics, 34, 1145-1165.

Kozloff, Sarah (2000): Overhearing film dialogue. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kulick, Don (2000): “Gay and Lesbian Language”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 29, 243-285.

Lefevere, André (1992): Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame, London, New York: Routledge.

Lewis, E. S. (2010): ‘“This is my Girlfriend, Linda”. Translating Queer Relationships in Film: A Case Study of the Subtitles for Gia and a Proposal for Developing the Field of Queer Translation Studies’, Other Words: The Journal for Literary Translators, 36, 3-22.

Libby, Anthony (2014): “Dragging with an Accent: Linguistic Stereotypes, Language Barriers and Translingualism”, in Jim Daems (ed.), The Makeup of Rupaul’s Drag Race Essays on the Queen of Reality Shows, Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 49-66.

Matamala, Anna. (2019): “Voice-over: practice, research and future prospects”, in Luis Pérez González (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Audiovisual Translation, Milton Park: Routledge, 64-81.

Medhurst, Andy (1997): “Camp”, in Andy Medhurst and Sally R. Munt (eds.), Lesbian and Gay Studies: A Critical Introduction, London-Washington DC: Cassell, 274-293.

Munday, Jeremy (2016): Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications, New York-London: Routledge.

Oostrik, S. E. (2014): Doing Drag: From Subordinate Queers to Fabulous Queens Drag as an Empowerment Strategy for Gay Men, Master Thesis, Utrecht University.

Orero, Pilar (2006): “Voice-over: the Ugly Duckling of Audiovisual Translation”, Proceedings of the Marie Curie Euroconferences MuTra “Audiovisual Translation Scenarios”. Saarbrücken,1-5 May 2006.

Pavesi, Maria, Maikol Formentelli and Elisa Ghia (2015): The Language of Dubbing: Mainstream Audiovisual Translation in Italy, Bern: Peter Lang.

Pérez-González, Luis (2014): Audiovisual Translation: Theories, Methods and Issues, London-New York: Routledge.

Pérez-González, Luis (2019): Routledge Handbook of Audiovisual Translation, New York-London: Routledge.

Ranzato, Irene (2012): “Gayspeak and Gay Subjects in Audiovisual Translation. Strategies in Italian Dubbing”, La Manipulation de la Traduction Audiovisuelle, 57/2, 369-384.

Ranzato, Irene (2015): Translating Culture Specific References on Television, New York- London: Routledge.

Ranzato, Irene and Serenella Zanotti (2018): Linguistic and Cultural Representation in Audiovisual Translation, London and New York: Routledge.

Rodríguez, Félix (2008): Diccionario gay-lésbico, Madrid: Gredos.

Rupaul (2010): Workin’It!: RuPaul’s Guide to Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Style, New York: Harper Collins.

Villanueva-Jordán, Iván (2015): “You Better Work: Camp Representation of RuPaul’s Drag Race in Spanish Subtitles”, Meta, 60/2, 376.

Von Flotow, Luise and Daniel E. Josephy-Hernández (2019): “Gender in audiovisual translation studies. Advocating for gender awareness”, in Luis Pérez-Gonzalez (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Audiovisual Translation, London-New York: Routledge, 296-312.

Wozniak, Monika (2012): “Voice-over or voice-in-between? Some considerations about Voice-over translation of feature films on Polish television”, in Aline Remael, Pilar Orero and Mary Carroll (eds.), Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility at the Crossroads, Amsterdam: Rodopi, 209-228.

Websites

Así es ser DRAG QUEEN en España [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3iCCYECrS8&t=929s>.

Así es ser Drag Queen en España [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<https://codigopublico.com/rompiendo-codigos/asi-es-ser-drag-queen-en-espana/>.

Collins [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<https://www.collinsdictionary.com/it/>.

Diccionario Clave [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<http://clave.smdiccionarios.com/app.php#>.

Diccionario de la Real Academia [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<https://dle.rae.es/>.

Merriam-Webster [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<https://www.merriam-webster.com/>.

Oxford English Dictionary [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<https://www.oed.com/>.

UrbanDictionary [Last accessed 04/01/2021]

<https://www.urbandictionary.com/>.

1 Alejandro Vellaz was the dubbing director in RPDR, Seasons 8-9; Carmen Gambín, in Season 10. Juan Yborra was the translator in Seasons 8-9; Juan María Sánchez, in Seasons 10. Álvaro Méndez was the adaptor in Season 8; Elena Ruíz, in Season 9; Carmen Gambín, in Season 10.

2 Transvestite wearing attention-getting clothes (my translation).

3 Generally homosexual man who dresses up like a very striking woman. (my translation)

4 Así es ser DRAG QUEEN en España: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3iCCYECrS8&t=929s> (Last accessed: 04/01/2021).

5 “Spain is not ready yet. Out of the queer community, people are not ready” (my translation) (“Así es ser drag queen en España” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3iCCYECrS8&t=931s Last accessed 04/01/2021).

6 “Being a drag queen in Spain is hard because it isn’t considered as mainstream as in other places. I think that within our queer community we are super appreciated […], but it is still hard for us to walk along the street in drag. We need time so that people can change their minds and dragqueenism become a normal activity”. (my translation) (“Así es ser drag queen en España” <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3iCCYECrS8&t=931s>. Last accessed 04/01/2021).

7 “The label drag queen in Spain is very much insulted. It is like the worst of the worst”. (my translation) (“Así es ser drag queen en España” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3iCCYECrS8&t=931s. Last accessed 04/01/2021).

8 “In Spain there still are narrow-minded people who get shocked for nothing. We are a very open-minded country, but there still are people that do not accept us”. (my translation) (“Así es ser drag queen en España” <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3iCCYECrS8&t=931s>. Last accessed 04/01/2021).

9 “Homosexual man wearing female clothes and exaggerating the female role that he feels as his own for the sake of entertainment. During his public performances, his shows are addressed to a gay and lesbian audience” (my translation).