:: MISCELÁNEA. Literaria. Págs. 245-264 ::

Reading Black Female Voices in Spain: Towards a Translation History of African American Women’s Literature*

-------------------------------------

Sandra Llopart Babot

Universitat Pompeu Fabra

-------------------------------------

This paper presents a descriptive approach to the reception of African American women’s literature in Spain through the study of its translation history. In this context, the first part of the paper describes the endeavor of developing AfroBib, a bibliographical tool that compiles exhaustive data about translations of African American women authors published in Spain. The second part of the paper discusses the translation history of African American women’s literature in the target country based on the statistical analysis of the data provided by our main research tool. The results display clear evidence of the increase in the circulation of African American women’s works and illustrate a complex network of social and literary factors that have influenced choices and strategies governing the translation of African American women writers in the country. This study offers unprecedented data, thereby holding out the prospect of encouraging parallel research lines.

palabras clave: African American Women’s Literature, Translation History, AfroBib, Bibliographical Database.

Voces femeninas negras en España: Hacia una historia de la traducción de la literatura afroamericana escrita por mujeres

Este artículo presenta una aproximación descriptiva a la traducción y recepción en España de la literatura afroamericana escrita por mujeres. En este contexto, la primera parte del artículo aborda el desarrollo de AfroBib, una herramienta bibliográfica mediante la cual se han recopilado datos exhaustivos sobre las traducciones de autoras afroamericanas publicadas en España. La segunda parte examina la historia de la traducción de la literatura afroamericana femenina en el contexto meta, tomando como base el análisis estadístico de los datos proporcionados por nuestra principal herramienta de investigación. Los resultados ilustran el aumento progresivo en la circulación de literatura afroamericana femenina y revelan una compleja red de factores sociales y literarios que han influido en las decisiones y estrategias que rigen la traducción de esta literatura en el país. Este estudio ofrece datos sin precedentes, con la esperanza de fomentar líneas de investigación paralelas en el futuro.

key words: Literatura afroamericana femenina, historia de la traducción, AfroBib, base de datos bibliográfica.

-------------------------------------

recibido en julio de 2020 aceptado en marzo de 2021

-------------------------------------

INTRODUCTION

Since the late twentieth century, European countries such as Belgium, Germany and, most prominently, France have produced several attempts at documenting the reception of African American culture and literature at a national level. Indeed, undertakings such as Michel Fabre’s (1995), Heike Raphael-Hernandez’s (2004), Bénédicte Ledent’s (2009) and Mischa Honeck et al.’s (2013) evidence the growing interest of European scholarship in this field of study. However, in Spain, the volume of academic production on this subject matter published to date is considerably reduced. In her seminal volume En el pico del águila (1998), Mireia Sentís laments the country’s deliberate lack of interest in what she regards as one of North America’s most genuine cultures, especially considering the fact that the globalized (literary) market systematically directs its focus towards the United States:

¿Quién conoce realmente la historia, la literatura o el pensamiento afroamericanos? Para que uno de sus autores sea traducido a nuestro idioma, debe alcanzar en su país una difusión muy superior a la media de los escritores normalmente traducidos. Ello provoca que, en terrenos como el del ensayo, apenas existan un par de recopilaciones de textos pertenecientes a la época de la lucha por los derechos civiles, coincidente con el surgimiento del nacionalismo, el orgullo negro y el Black Power. Llevamos, pues, unos cuarenta años de retraso aproximadamente respecto a la realidad cultural afroamericana, o lo que es lo mismo, respecto a la realidad cultural norteamericana. (1998: 7-8)1.

Following this line of argument is Arjun Appadurai’s problematization of the contemporary dynamics between homogenizing and heterogenizing tendencies in the modern era. He, in turn, identifies homogenization with Americanization and capitalism (1996: 32).

As far as literature is concerned, at the round table of the XXVI AEDEAN Congress (2003), Mar Gallego briefly reviewed the translation history of African American literature in Spain, criticizing its absence from anthologies of American literature published during the first decades of the twentieth century. Even if translations proliferated during the second half of the twentieth century and, most prominently, during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, attempts at studying its reception in the country have been scarce. Among such endeavors, we could highlight Robert F. Reid Pharr’s Archives of Flesh: African America, Spain, and Post-Humanist Critique (2016) and the recently published volume Black USA and Spain: Shared Memories in the 20th Century (2020), edited by Rosalía Cornejo-Parriego. While both works study translational exchanges in different cultural manifestations, ranging from artworks to music, travelogues and performances, among others, literary products are of special importance in both cases. In the case of Reid-Pharr, his volume approaches the study of decades of dialogue between black America and Spain from the perspective of post humanist critique, paying special attention to Langston Hughes’s, Chester Himes’s and Richard Wright’s relationship with the target country. Likewise, the works compiled by Cornejo Parriego focus on cultural exchanges produced during the Harlem Renaissance and the Jazz Age, the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship.

Spanish editors, translators and critics such as Carme Manuel and Mireia Sentís have problematized the traditional preference of Spanish publishing houses for classics of universal literature. This trend has inevitably hampered the reception of black women writers who have either not been translated because they are not considered canonical or were not adequately disseminated at a certain point in the past due to socio political constraints and have never been recovered. As a response to this phenomenon, the Biblioteca Afro Americana de Madrid (BAAM) was created in 2011. Its main objective is to provide a panoramic view of black history in the United States by translating unpublished works in the target context in order to enrich the current scarce supply (Biblioteca Afro Americana de Madrid, 2018: n. p.).

In addition, intermedial adaptations of novels written by African American women have emerged since the 1980s. Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple [El color púrpura] (1985), based on Alice Walker’s homonymous novel, was a box office success and it attracted much attention in the international press. Other adaptations such as Beloved (1998), Waiting to Exhale [Esperando un respiro] (1995) or Precious (2009) also enhanced the circulation of African American women’s literature in Spain. Likewise, the international prestige that authors such as Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Angela Davis or Maya Angelou have acquired has become a further determining factor in their canonization and consequent dissemination in the target country. In this regard, Marta Puxan-Oliva highlights “the great cultural and political interest that African American literature has recently aroused in Spain”,2 arguing that it has contributed to the search for a common collective identity that can overcome discrimination, which, she contends, has always been one of the pillars of this literary tradition (2016: 13). Similarly, while discussing the evolution of black studies in Spain Mar Gallego draws attention to gender oriented approaches such as black feminism, black masculinity studies and intersectionality theories as perspectives that have profoundly marked contemporary scholarship in the field (2016: 154).

In this context, this paper draws on the assumption that African American women’s literature constitutes a self-governing unit of analysis when mapping the reception of US literature in Spain, and that its study is thus necessary and indispensable. Considering the reality that no parallel undertakings have been developed within this field of research, this approach to the translation history of black women’s literature is presented as a fundamental first step in the process of examining its reception in the target country. International and national databases such as the UNESCO Index Translationum, the ISBN Database of Books Published in Spain or the catalog of the National Library of Spain present several shortcomings. For instance, the ISBN database is time-limited, as it only considers publications after 1972. Likewise, existing entries in the aforementioned tools do not always disclose all the relevant information about published translations (i.e. references to translators, publishers or collections, among others, are sometimes missing or misleading). These systematic inconsistencies have also been signaled by authors such as Marín Lacarta (2012) and Fernández-Ruiz et al. (2018), as they inevitably hamper the development of accurate studies in the field of our domain.

Taking this as a starting point, during the years 2018 to 2019 the bibliographic database AfroBib was developed by the author of the paper. This open-access resource compiles bibliographical information about works by African American women writers that have been translated and published in Spain; AfroBib is regularly updated on a monthly basis. This digital collection contains specific information about more than 200 publications including currently available works as well as those out of print published since 1968 (first translation of a black woman writer published in Spain) to present day. Data relative to each entry were carefully selected, contrasted and revised before publication, and are fully available at https://afrobib.upf.edu.

METHODOLOGY AND DATABASE DESIGN

Processes of literary reception in a target culture materialize themselves in a wide range of forms and phenomena. According to Andringa (2006: 537), when studying systems of reception of a foreign literature in a target system, the translation history of such literature must be examined as an independent factor before trying to interpret it within a larger framework of analysis. Andringa’s approach is shared by scholars such as Lécrivain and Díaz Narbona (2009), Poupaud et al. (2009), Román (2017) and Fernández Ruiz et al. (2018), among others. Likewise, Brems and Ramos Pinto foreground the relevance of quantitative approaches when studying the intersection between translation and reception studies (2013: 144). Indeed, the study of the translation history of a certain literature makes it possible to observe how a concrete representation of diversity is established, insofar as translations are the fundamental element guiding the acts of reception of the target works. Hence, the core question addressed in this paper is how a specific foreign literature is represented in a target literary system through translation processes. More precisely, we will examine the role of translation in the reception of African American women’s literature in Spain.

Experts in the field such as van Doorslaer (2007), Poupaud et al. (2009), Assis Rosa (2012) and Zanettin et al. (2015) have problematized the endeavor of database construction:

Bibliographies provide a way of surveying the past; we must, however, be aware of possible distortions created by the fact that the concepts and categories we use have been shaped by the same history that we want to trace. In order to integrate this awareness and bring an element of self-reflexivity to this bibliographic study, we draw from anthropological work by Arjun Appadurai and Tim Ingold so as to discuss translation studies as a disciplinary landscape (Appadurai, 1996) and acknowledge our role […] as inhabitants in that landscape (Ingold, 2007) (Zanettin, 2015: 166).

In addition, factors such as the growing multialignment of writers in more than one literary system (Lécrivain, 2015: 237) and the partiality and selectiveness of criteria implied in choices of inclusion / exclusion (Assis Rosa, 2012: 212) also pose a challenge to the undertaking of building and using a solid and reliable tool. In this context, the necessity of drawing up a thorough compilation protocol was manifest. This protocol involved five main stages, namely planning and design, selection of data sources, data collection and classification, publication and distribution and statistical analysis.

Considering Anthony Pym’s discussion of method in translation studies (2014), we should therefore accept that any endeavor to create translation bibliographies, lists or indexes will inevitably be partial and limited. Taking this assumption as a starting point, preliminary specific criteria were established from which to build our particular database. As has been already noted, prior considerations involved acknowledging the fact that AfroBib is partial in scope because it is selective based on specific predefined criteria which inevitably entail some limitations:

- Geographic and cultural scope: From the point of view of the source context, AfroBib considers literature written by US-born or nationalized black women authors. This categorization is self-imposed; that is, the authors included in our database consider themselves African American women writers. Likewise, from the perspective of the target context, AfroBib covers publications in Spain (rather than other Spanish speaking countries).

- Linguistic scope: It is restricted to English as the source language and it considers Spanish as well as co-official languages in Spain (i.e. Basque, Catalan and Galician, in this case) as the target languages. As noted by Assis Rosa (2012: 212), the linguistic criterion is only an assumption derived from the place of publication.

- Thematic scope: It considers assumed translations of assumed literary works by black women authors from the US.

- Chronological scope: It includes all translations of African American women’s works published in Spain up to present date. Consequently, it covers translations from 1968 to 2020.

- Scope in genre: It covers publications from all literary genres, including fiction and non-fiction narrative, poetry, drama and essay. It also includes translations of texts or fragments (e.g. book chapters) published in books, journals and anthologies in the target context.3

- Scope in medium: It considers volumes published in print as well as electronically.

- Availability scope: It includes both available and out of print works.

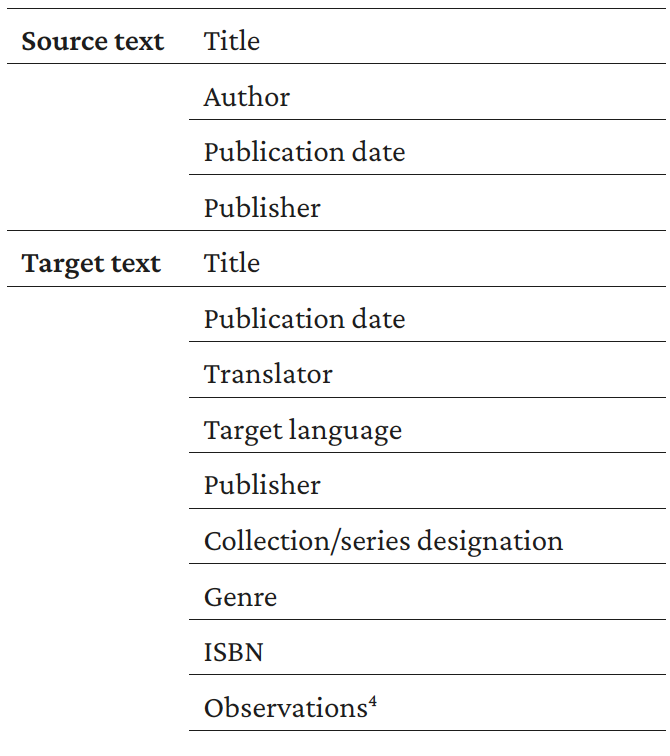

Table 1. AfroBib design criteria and descriptors

Access to footnotes: 4

Anyhow, according to Zanettin, Saldanha and Harding (2015: 167), in order to “occupy” our field of study, classification through a controlled system of categories or descriptors is necessary. Consequently, an important part of the preliminary work for designing the database involved a careful consideration of the entry template to be created, in terms of both inclusions / exclusions of information and order. 1 displays AfroBib’s eleven descriptors, which consider basic information about the source text and specific information about the target text. Following Assis Rosa (2012: 213), data provided about the source texts make reference to the original first edition.5 Once the criteria had been selected, special consideration was devoted to the creation of searchable categories in the online version of the database. These include title of the source text, publication date of the source text, title of the translation, publication date of the translation, author, translator and publisher.

Pym (2014: 51) has discussed the shortcomings of building bibliographies based on one single previous source, as the ideology and criteria of the source will automatically be transferred to the new tool. Thus, bibliographic data for AfroBib were obtained from a number of different physical and online archives, namely the ISBN Database of Books Published in Spain, the National Library of Spain, the UNESCO Index Translationum, the National Library of Catalonia, the University Union Catalogue of Catalonia as well as the catalogs of different Spanish publishing houses and online marketplaces, such as Amazon, IberLibro and AbeBooks. Consulting a wide variety of sources did not only prevent the transference of a particular system of criteria to our research, but it also compensated for the aforementioned lack of complete, systematic records of bibliographical information. Indeed, although these sources may be limited on their own, each provided a list of titles and specific data that could be used to draw up a more comprehensive list.

Thus, information was collected and classified according to our predetermined criteria (see Table 1), and subsequently incorporated into an Excel spreadsheet. This process required laborious and time-consuming manual shifting in order to detect and deal with missing, misclassified or duplicate information. This procedure was of primary importance as it provided us with a final set of data that could be ultimately transformed into a searchable database and used for a more detailed analysis. This data collection process ensured the construction of an exhaustive and reliable tool, which produced solid analyzable data.

Once the information was compiled and duly classified, issues related to the publication and distribution of the bibliography were brought to the fore. Not only because of the example of already existing open access bibliographical tools such as Intercultural Literature in Portugal (translatedliteratureportugal.org) or BDAFRICA (bdafrica.eu), but also because of the incomparable flexibility of navigation, search and update, it was decided that AfroBib would be an electronically searchable open access database fully available online. This decision entailed the additional necessity to design the architecture of the electronic database (as opposed to the original Excel sheet), the interface and content of the website as well as choosing the most suitable categories to use as search criteria. Thus, database entries were exported to MySQL —a specific database management system—to make the data available online at https://afrobib.upf.edu.

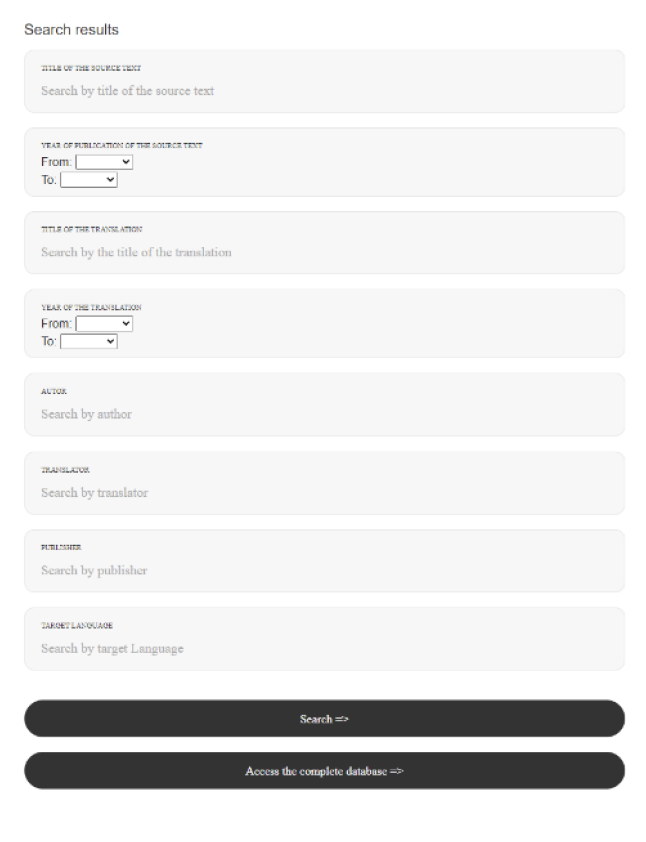

Figure 1. Online search interface

Figure 1 shows the AfroBib search interface, where searches may be run by indicating one or more descriptors, namely title of the translation, title of the source text, author, translator, target language, publication date and publisher. Inevitably, the selection and display of search possibilities in the interface draws attention towards the nature of this tool as a bibliography of translations. However, the site also includes a shortcut that provides access to the complete and unfiltered bibliographical entry list.

DATA ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Our statistical treatment of literary works by African American women authors published in Spain is original and unprecedented, pursuing the ultimate aim of offering a much needed overview within the larger field of Anglo American Studies that will help to identify where these works stand within the Spanish publishing market.

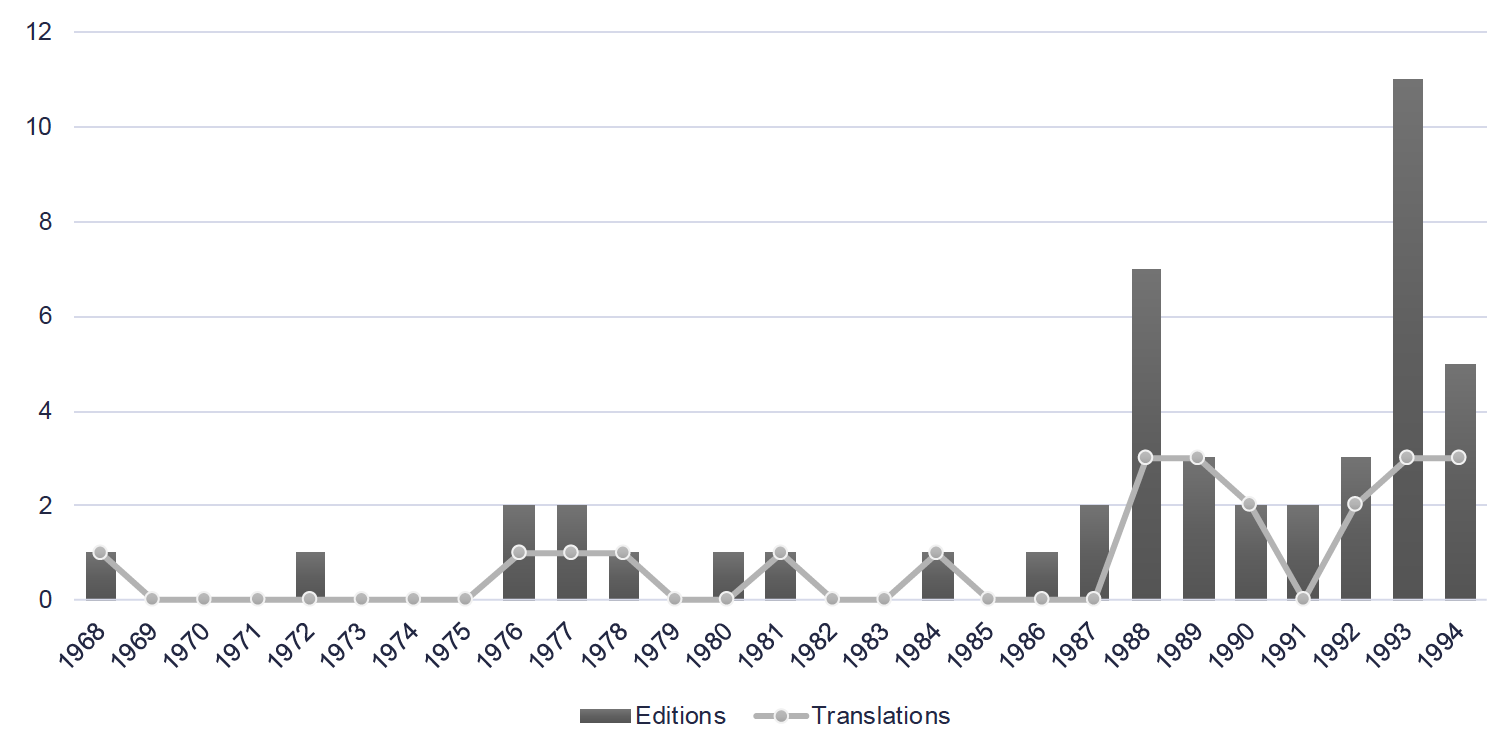

Figure 2. Evolution of the publication of African American women’s literature in Spain from 1968 to 1994

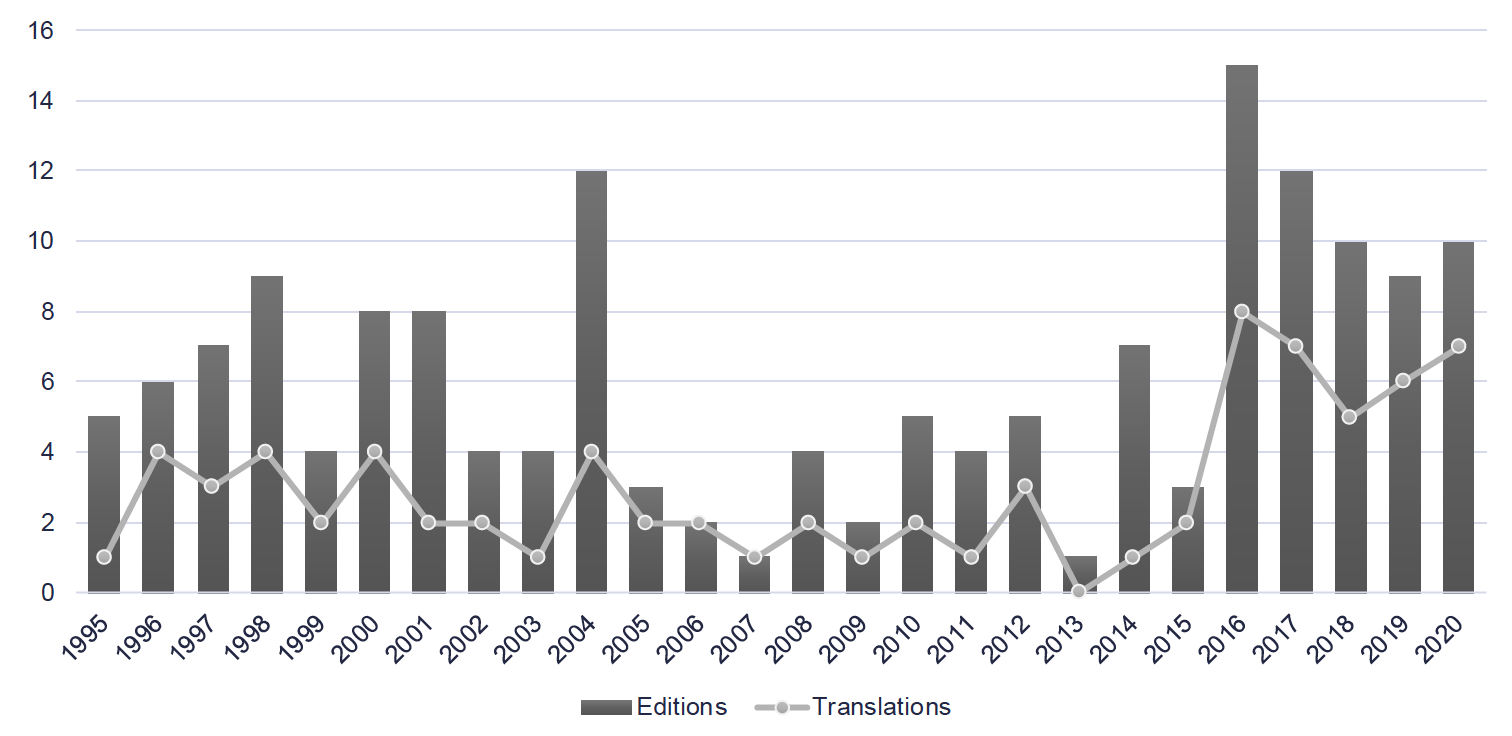

Figure 3. Evolution of the publication of African American women’s literature in Spain from 1994 to 2020

AfroBib includes a total volume of 228 editions and 115 translations of works by African American women published in Spain between 1968 and 2020. 2 and 3 illustrate the evolution in the publication of these works within the aforementioned timespan. Even though an irregular development is displayed, several peaks can be observed which coincide with major landmarks for black women authors, such as the premiere of the movie adaptation of Alice Walker’s masterpiece The Color Purple [El color púrpura] in 1986, the award of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction to Toni Morrison in 1988, and, most notably, the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993. Indeed, during the years following the premiere of Spielberg’s adaptation, six editions of El color púrpura were published in Spain; all of them reprinted the original translation by Ana María de la Fuente. Likewise, the year that Morrison was awarded the Nobel Prize, Ediciones B reedited some of her most notable works, namely Beloved (trans. Iris Menéndez), La canción de Salomón (trans. Carmen Criado), Jazz (trans. Jordi Gubern), La isla de los caballeros (trans. Mireia Bofill) and Sula (trans. Mireia Bofill), for the series “Tiempos Modernos”.6

After the turn of the century, DeBolsillo acquired the rights to publish Toni Morrison’s oeuvre, which had already been introduced into the Spanish literary system by independent publishers such as Argos Vergara, Plaza y Janés or Ediciones B. The dissemination of Morrison’s works by one of the great publishing groups in the country (DeBolsillo is part of the Penguin Random House conglomerate) coincided with the growing interest of independent publishers to incorporate into their catalogues the works of prominent figures of the African American literary landscape: not just Morrison, but also Alice Walker, Angela Davis, Maya Angelou, Audre Lorde and bell hooks were published in Spain during the first years of the new millennium.

Regarding the publication of translations illustrated in 2 and 3, from 1994 to 2000 the relationship between editions and translations oscillated at around 50%. The slight variation in this proportion during the first years of the twenty-first century —the percentual relationship between editions and translations fell to 39% from 2001 to 2005— can be understood in the context of DeBolsillo’s endeavor to reedit Morrison’s works, which were already circulating in the target context.

The year 2016 witnessed the culmination of the outburst of small publishers that had begun right before the onset of the great recession in 2008 (Alós, 2017: n.p. and MCD, 2018: 18 and 54). In this context, during 2016 and 2017, while Penguin Random House and other smaller editorial groups continued translating and publishing the works of bestselling authors —not only in Spanish, but also in other co-official languages—, independent publishers started to incorporate into their catalogues new names within the landscape of African American literature. These were either canonical authors in the source context who had had scarce recognition in the target country (e.g. Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larsen, Ann Petry) or new contemporary voices (e.g. Carol Anderson, Patricia J. Williams, Lisa Jones). Moreover, Morrison’s death in the summer of 2019 renewed interest in her work. Thus, her novels were reedited and some of her most notable non-fiction works, namely Jugando en la oscuridad (trans. Pilar Vázquez †) and La fuente de la autoestima (trans. Carlos Mayor) were posthumously published in translation during 2020.

As a consequence of these events, nearly 30% of the total amount of editions registered in AfroBib was published over the last five years. Considering the volume of translations published during the same time span, this amounts to 37% of the total sum. These figures indicate a growing interest in black women’s literature by Spanish publishers, both in terms of circulating classic works and incorporating new voices to the Spanish publishing market.

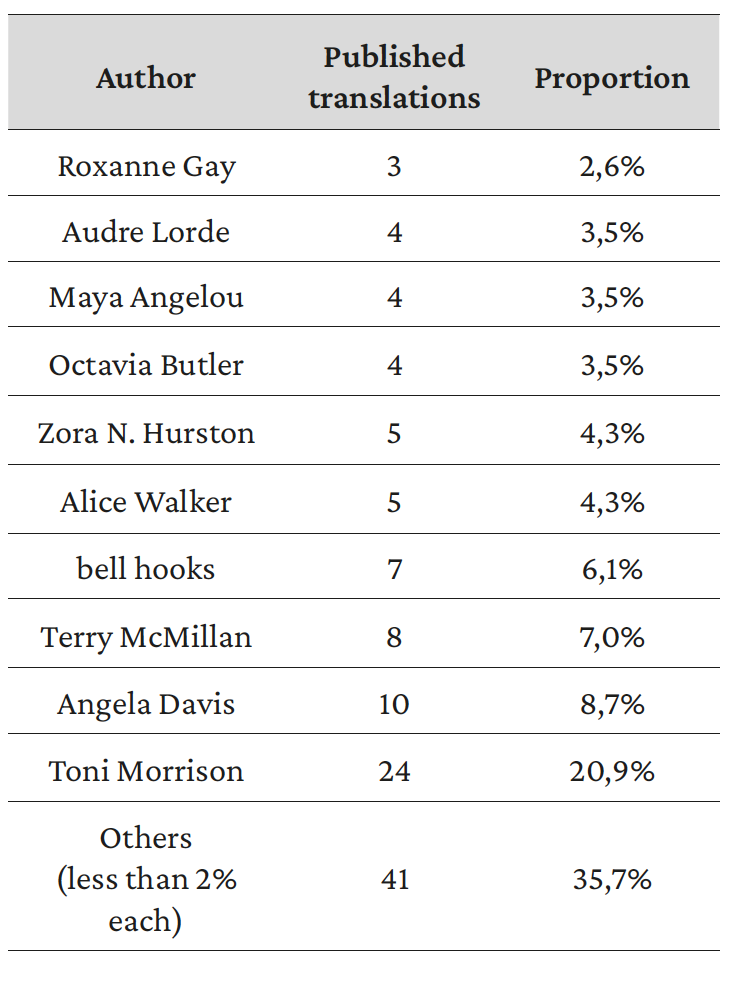

Table 2 and Figure 4 illustrate the number of translations per author that have been published in peninsular languages, and the corresponding proportion with regard to the total amount of translated texts.7 Out of the 42 writers whose works have circulated in the target context, Toni Morrison is the most translated (20,9% of the total amount of translations). Angela Davis and Terry McMillan follow her with 8,7% and 7%, respectively. The table and the chart below also point out the fact that most authors have only had two (8,7%) or one work translated (27%).

Table 2. Published translations per author and proportion out of 100%

Figure 4. Proportion of translations published in Spain per author

As for the translators, 87 agents have taken part in the 115 translations compiled in AfroBib. At a first glance, these numbers reveal a scarce specialization on the part of the translators, and a general lack of interest from the publishers to promote expertise in this type of literature. On this subject, Eleonora Federici and Vanessa Leonardi have argued that “the major scholars in TS [Translation Studies] are underlining the necessity to take into account the ethics of translation and the competence of translators in an era of globalization and massive movements of people around the world. Today, translation means intercultural exchange with a profound awareness of cultural difference and linguistic boundaries.” (2013: 2)

Drawing from these notions, much research has been conducted within the interdisciplinary fields of translation and gender studies —and within the intersection between the two—, problematizing inherent differences between men and women writers and, consequently, men and women translators. Indeed, in recent years research has been carried out around the hypothesis that gender difference interferes or mediates in translation. Among others, the work of Leonardi (2007), Santaemilia (2014), Tzu-Yi Lee (2013), Kim (2015) and Rabeie and Shafiee-Sabet (2011) is of particular interest. Along these lines, José Santaemilia argues:

The idea that there is an écriture féminine or a woman’s sentence (as opposed to a default man’s sentence) [italics in the original] is, undoubtedly, an attractive one, which many feel is justified. It consists of a series of abstract traits that are thought to characterize all women (and all men) and that reinforce the belief that sexual differences are inscribed in language. […] What is especially noteworthy is that this logic leads us to the inescapable fact that there must be differences between women and men writers (2014: 105).

However, unfortunately, research such as the one conducted by Santaemilia is still in its first stages of development, so that scholars in the field have only been able to draw partial conclusions from the results of very concrete case studies. Therefore, generalizations about the influence and consequent relevance of gender difference in translation cannot be drawn yet.

In the case of our database of translators, even if AfroBib compiles significantly more female than male agents —62 against 25, respectively—, numbers here are not conclusive enough to allow generalizations about a certain inclination or preference for women translators. However, further studies following Leonardi’s and Santaemilia’s proposals would definitely be as necessary as fruitful to bring light into this research field.

Moving on from the problematic issue of gender difference in translation, we should also acknowledge the fact that three of the translators registered in AfroBib have been awarded the National Prize for the Work of a Translator [Premio Nacional a la Obra de un Traductor] by the Spanish Ministry of Culture and Sports (MCD), namely Roser Berdagué (2009), Jordi Fibla (2015) and María Dolors Udina (2019). Both Fibla and Udina have translated works by Toni Morrison as well as other Nobel laureates such as J.M. Coetzee or Nadine Gordimer. As for Berdagué, she has translated Nobel Prize Saul Bellow as well as world-famous author Charles Dickens, among others; however, she has also devoted herself to the translation of bestselling authors such as Danielle Steele or Terry McMillan (present in AfroBib).

The case of translator Carme Manuel also deserves special attention. She has translated works by nineteenth century writers Harriet A. Jacobs, Elizabeth Keckley, Harriet Wilson and Pauline E. Hopkins, voices which had never been presented to Spanish audiences in translation. In relation to this, Manuel states:

las editoriales grandes continúan publicando todavía hoy los autores norteamericanos más canónicos, los de siempre, los de toda la vida, los que se tradujeron ya en los años 30, 40, 50 y 60; y no hacen ningún esfuerzo por introducir, dentro de lo que son las colecciones realmente comerciales, nombres nuevos, y rodearlos de un mínimo estudio, una mínima presentación. (2009: n.p.)8.

In this respect, the various publications in which Manuel has collaborated (either as translator or editor) include a critical study of the author and her work complementary to the text per se.

As for the publishing industry, AfroBib reveals that 66 agents have published works by African American women in Spain. In the hypothetical event that the 66 publishers were active in 2020 (which is not the case, as some have disappeared or are currently inactive), this would mean that only around 2,3% of the total amount of Spanish publishers would choose to work with African American women’s literature.

These data reflect the generalized scarce interest in African American women writers shown by publishers in Spain, except for a few individual cases. It is also true, however, that some Spanish editors, writers and translators have tried —and are still trying— to promote the circulation of this literature in the country, even though most times the prevalent criterion to translate and publicize literary works by African American women authors is the success granted by external factors such as the award of internationally prestigious literary prizes or the popularization of certain works through their movie adaptations.

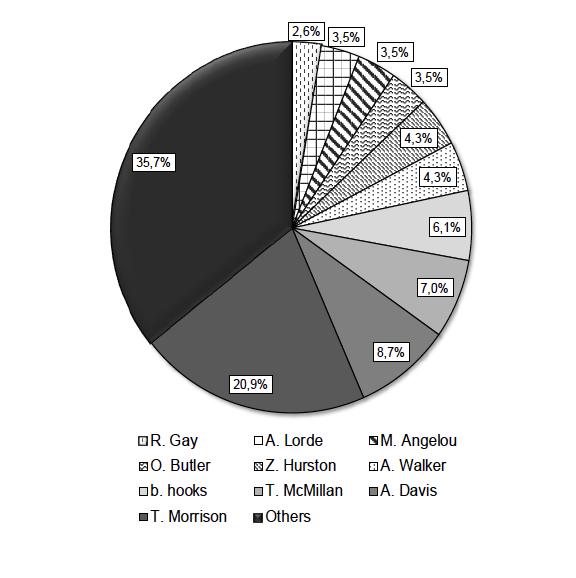

Among the agents that have published works by African American women in Spain we can find big publishing groups, medium and small publishers, as well as university presses. As for the big publishers (i.e. multinational conglomerate corporation Bertelsmann, Planeta and Penguin Random House), most of the authors that have been translated and published in Spain by houses belonging to these conglomerates had already earned international recognition and caught the attention of the mass media before these agents decided to support them and disseminate their works at a national level. In relation to this, translator Carme Manuel points out the scarce willingness shown by the Spanish publishing industry to incorporate new foreign voices to the dominant literary system, which, according to Manuel, is monopolized by an ongoing tradition of promoting and reading the classics (2009: n.p.).

In this context, writers Toni Morrison, Terry McMillan, Alice Walker, Maya Angelou and Zora Neale Hurston have been published by Bertelsmann; Toni Morrison, Terry McMillan, Gloria Naylor, Billie Holiday and Sapphire have been published by Planeta, and Toni Morrison, Alice Walker and Harriet Ann Jacobs have been published by Penguin Random House. In any case, these authors’ works started to circulate in the target country only after they had become international bestsellers or the writers themselves had acquired a certain degree of worldwide literary prestige. The bulk of texts compiled at AfroBib were published by small and independent publishers. These include Anagrama, Capitán Swing, Traficantes de Sueños, Katakrak and Contraseña, among many others, some of which eventually merged with the bigger groups.9

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of publishers involved in the circulation of translated African American women’s literature. While more than half of the texts registered at AfroBib were circulated by independent publishers, among which the works of Capitán Swing, Traficantes de Sueños and Biblioteca Afro Americana de Madrid (published by Ediciones del Oriente y del Mediterráneo) stand out as particularly prolific; 23 works were distributed by Penguin Random House, 19 by Bertelsmann and 11 by Planeta. Other editorial groups such as RBA, Grupo Anaya or Grupo Zeta, among others, published 24 texts altogether, and there are 6 publications registered by different Spanish universities.

Figure 5. Distribution of Spanish publishers of African American women’s literature

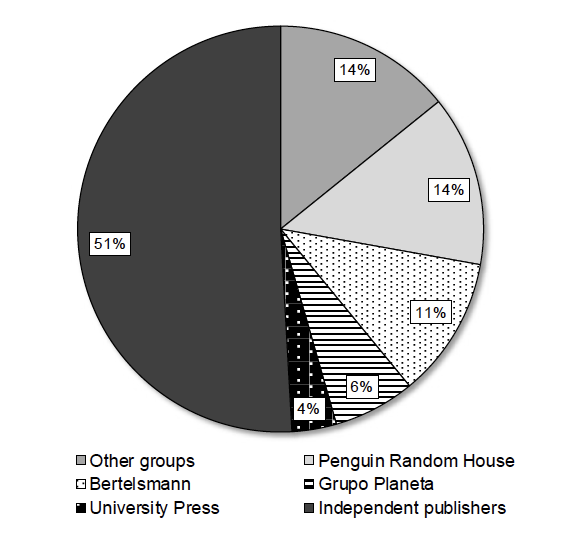

As has already been introduced, AfroBib includes works that have been translated into Spanish and other co-official languages. Thus, even though most translations were published in Spanish, we can also find several Catalan, Basque and Galician titles. Figure 6 displays the proportion of languages of translation as for the works compiled in our database. As illustrated below, nearly 90% of the editions were published in Spanish (203 titles). More than half of the remaining 11% correspond to texts published in Catalan (14 titles), while 4% of the texts were translated into Basque (9 titles). Only 2 texts have been translated into Galician (1%).

Figure 6. Distribution of languages of translation of African American women’s literature in Spain

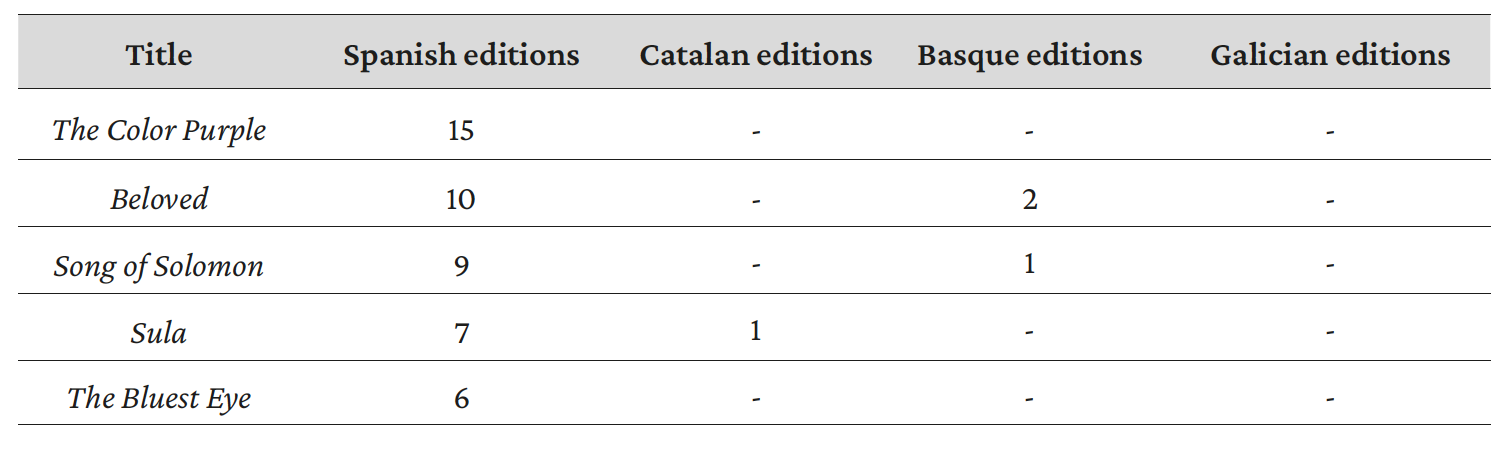

However, if we look at the texts that have been translated into co-official languages and compare them to the most recurrently published volumes, as shown in Table 3, we can see that there is no correspondence between them. Therefore, we can conclude that the success or popularization of a certain work in Spain is not a determinant criterion for translation into co-official languages.

Table 3. Comparison between the five most edited titles in Spain and their editions in co-official languages

One observable difference in the texts selected for translation is that, in the case of Catalan and Basque, the vast majority of authors and works that have been translated belong to the realm of contemporary literature, namely Angela Davis, Claudia Rankine, Sapphire and Terry McMillan in the case of Catalan translations and Angela Davis, Audre Lorde and bell hooks in the case of Basque translations in addition to Toni Morrison, who has been translated into both languages. However, as for Galician, the only two texts that have been published are classics of African American literature, namely Passing and Their Eyes Were Watching God.

At this point we should also consider the fact that the time lapse between the publication of the source text and the two Galician translations is much longer than in the case of the Catalan or Basque translations. Josep Pujol et al.’s reflections on the current status of Catalan translations may bring some light into this matter:

La literatura catalana es hoy receptora habitual de las novedades literarias en otras lenguas, aunque tiene que competir con una industria editorial en castellano de dimensiones mucho mayores. [...] El editor catalán sólo obtiene resultados satisfactorios cuando consigue que la traducción que él publica aparezca antes o al mismo tiempo que la traducción al castellano, y con un precio de venta similar. (2004: 693)10.

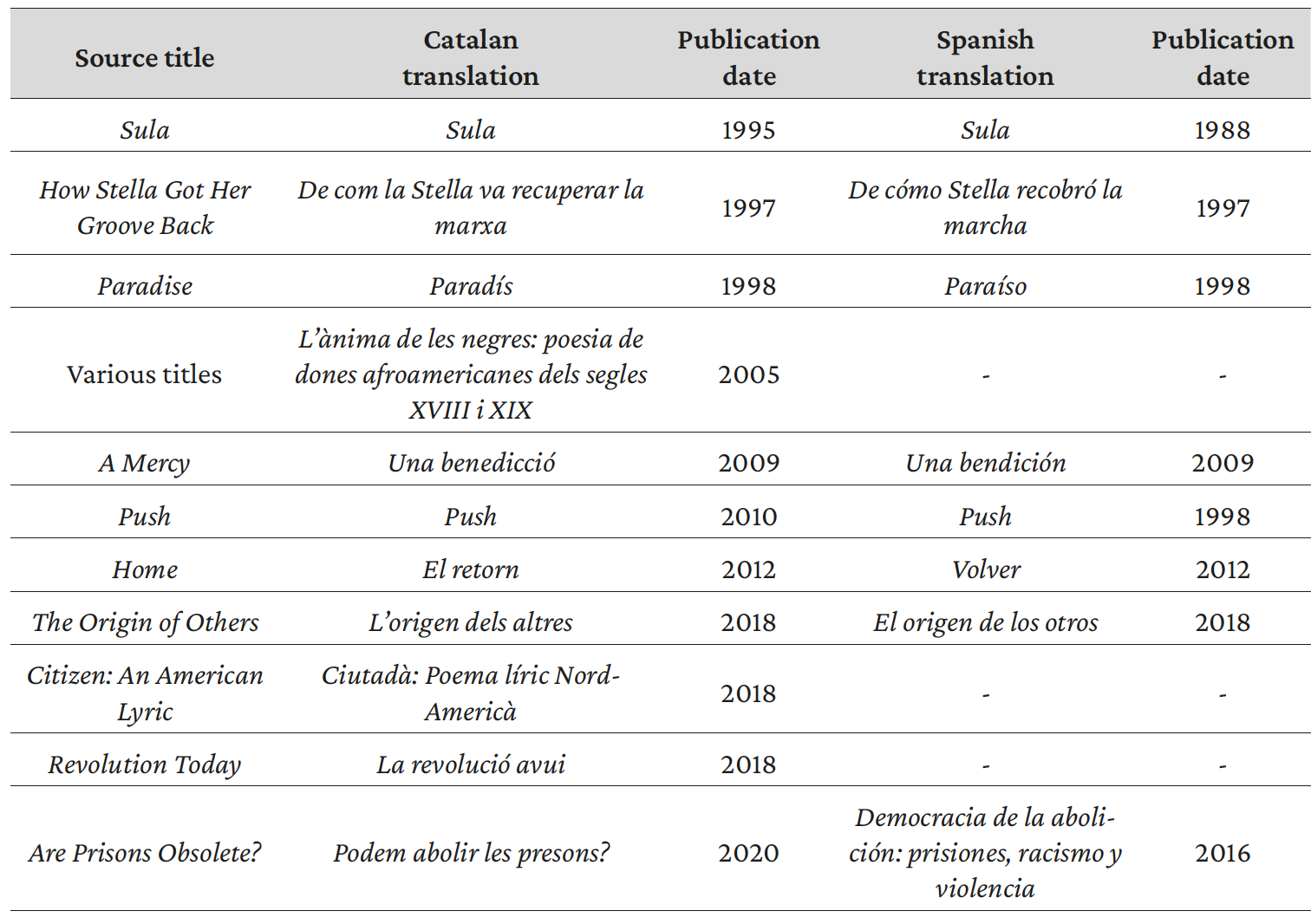

This description in fact coincides with the data summarized in Table 4 below.

Table 4. Overview of the publication dates of the first editions of texts translated into Catalan and/or Spanish

As shown above, most Catalan translations were published shortly after or parallel to the Spanish translations, the only exceptions being Sula (trans. Dolors Ursina), Push (trans. Alícia Mirall) and Podem abolir les presons? (trans. Aurora Ballester i Gassó). In the case of Morrison’s novel, it was the first text written by an African American woman ever translated into Catalan, and it was published a year after Morrison was awarded the Novel Prize for Literature as part of a collection of classics planned by Catalan publisher Columna. Especially relevant here is the fact that in 1991 and 1993 Morrison had given several lectures at the University of Barcelona, so she was already an established presence at least among the Catalan academia even before her works were introduced into this literary system. As for Push, even if the source text was originally published in 1998, the 2010 Catalan translation followed the release of its Hollywood movie adaptation Precious in Spain. The translation of Davis’s volume can be framed within the context of the Catalan independence movement. Indeed, Podem abolir les presons? was published in Catalonia following the events of the trial of Catalan independence leaders, and actually included a foreword by Jordi Cuixart, the president of Catalan association Òmnium Cultural, who was sentenced to nine years’ imprisonment and disqualification after the events of October 1, 2017.

As for the two Galician translations, the earliest of them was carried out by Elvira Souto and published in 1993, a time when the Galician Government was promoting the translation of universal classics within a greater project of linguistic standardization (Noia, 2004: 776). In her overview of translation history in Galicia, Camiño Noia describes Laiovento, the publisher of this early translation, as compromised with the dissemination of texts dealing with linguistic problems, political reflection, or the history of nationalisms (2004: 780), interests very much in line with the issues brought forward in Their Eyes Were Watching God. Regarding the 2017 translation of Nella Larsen’s Passing, it was rendered by Carlos Valdés for a young small independent publishing house, Irmás Cartoné, as part of their catalogue of twenty two universal classics.

In the case of the translations into Basque, it is the only co-official language that has translated Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Beloved (trans. Antton Garikano), in this case for the collection “Literatura Unibertsala” [Universal Literature], which was financed by the Basque Government at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Several works by Angela Davis have also entered the Basque literary system, probably as a result of the writer’s relation with the Basque nationalist politician Arnaldo Otegi. Actually, the four Basque translations of her works date from 2016 and 2017. This fact may be directly linked with the events that occurred in 2016, when Davis met Otegi after he was released from prison,11 and he later wrote the foreword for the 2017 Spanish edition of the black activist’s autobiography, translated by Esther Donato and published by Capitán Swing. A translation of bell hooks’s Feminism Is for Everybody was published by Katakrak (trans. Amaia Apalauza), an independent house that follows a critical and political editorial line (Fillat, 2020: 68). Finally, an anthology of Audre Lorde’s poetry was translated by Danele Sarriugarte and published by Susa in “Munduko Poesia Kaierak” [World Poetry], a series started in 2014 by Beñat Sarasola that edits four poetry anthologies every year. The publishing house, Susa, distributes works of narrative, poetry and drama entirely in Basque. In this context, Lorde was presented as a fundamental contemporary author who had moved from the margins to the center of the literary canon (Sarasola, 2018: n. p.).

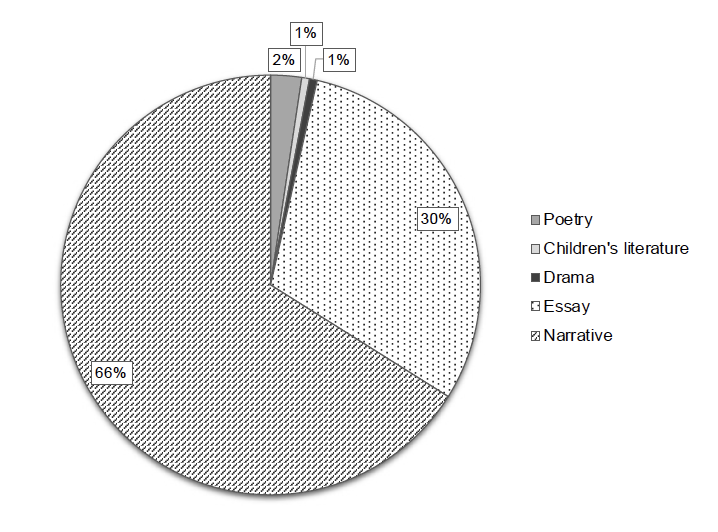

As for the genres that have been translated, AfroBib registers fiction novels mostly, although several instances of other genres in translation can also be found in the bibliography. Results displayed in 7 are supported by the data collected by the MCD throughout the time period studied, which conclude that narrative is by far the most edited literary genre in Spain, as for both local and imported literature.

Figure 7. Proportion of translated works according to genre12.

Taking as an illustrative example data from the Overview of Book Edition in Spain [Panorámica de la edición española de libros] in 2016,13 the MCD’s report registers 11.922 ISBNs classified as narrative, 3.605 classified as poetry, 385 classified as drama and 709 grouped under “other genres”. From these absolute values, the narrative genre has the highest percentage of translated texts (30,2%), followed by drama (16,6%), other genres (13,1%) and poetry, with a scarce 6% of translations. As these numbers evidence, there is a correspondence between the general values of translated literature and African American women’s translations except for the case of the essay, which constitutes the second most translated genre in our data samples.

Looking at the essays by African American women that have been translated into peninsular languages, which represent 30% of the total translated production, data show that the publication of this genre has increased during the last decade, non-fiction being translated not only into Spanish but also Basque and Catalan. A common ground for all these texts is that they share strong sociopolitical imbrications, directly challenging dominant discourses of racism and sexism from the experience of the African American woman writer. It is also worth to mention that nearly one quarter of the essays published in Spain were written by Angela Davis, while the resting 75% introduce the views of diverse authors, spanning from Audre Lorde to Lisa Jones, Michelle Wallace or Jesmyn Ward. In relation to this, the volumes Cuerpo político negro (2017, trans. María Enguix and Malika Embarek) and Esta vez el fuego: Una nueva generación habla de la raza (2020, trans. María Enguix), deserve special attention. Both were published by Ediciones del Oriente y del Mediterráneo as part of the collection Biblioteca Afro Americana de Madrid, and they introduced to Spanish audiences the works of contemporary authors such as Patricia J. Williams, bell hooks, June Jordan, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah or Kiese Laymon —together with those of other African American male writers—, some of whom had never been published in Spain before.

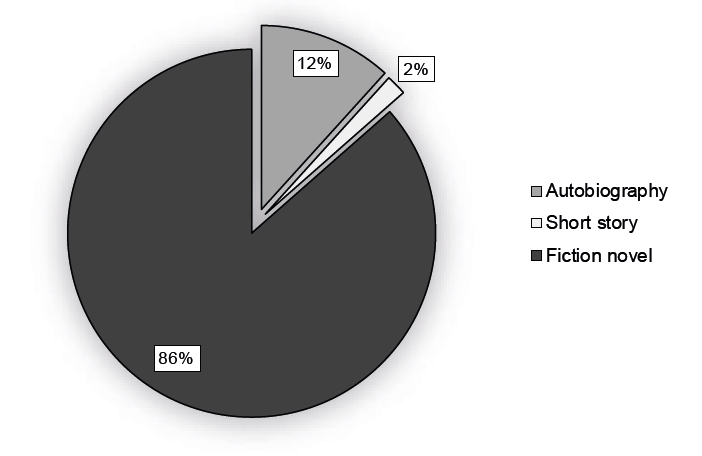

7 evidences the overwhelming dominance of the narrative genre among all African American women’s literature published in Spain, with a 66% of the works belonging to this domain. However, this research suggests a further subdivision within the narrative genre with the aim of obtaining more precise results. Accordingly, Figure 8 illustrates such division into subgenres.

Figure 8. Proportion of subgenres within “narrative”

As Figure 8 reflects, the fiction novel is still the most translated (sub)genre, even though we can also find several translated autobiographies and short stories. As for the short stories, most of them were written by Ann Petry, and were published in the series Los huesos de Louella Brown y otros relatos (trans. Teresa Lanero Ladrón de Guevara) by independent publisher Palabrero Press in 2016 (precisely the same year that the publishing house was founded). The other remaining short story, Morrison’s Recitatif, was published in English by Spanish publisher Pons with a didactic function. Indeed, Recitatif was included in the collection “Read & Listen” for English learners:

En la selección de los relatos nos hemos guiado por varias premisas: en primer lugar, tenían que ser textos sugerentes pero no demasiado complejos; en segundo lugar, tenían que ser clásicos en miniatura, de aquellos que no se olvidan, que deben leerse con cuidado, degustando cada frase, cada palabra, en definitiva, textos sin los cuales la historia de la literatura no sería la misma. (Pons editorial team, 2011: n.p.)14.

Less striking is the fact that 12% of the translated African American women’s narrative consists of autobiographies, taking into account that this has been a prolific (sub)genre for the authors studied here. These comprise from the works of contemporary authors such as Maya Angelou, Angela Davis or Billie Holiday to those dating from the Pre-Civil War era. In the case of The Religious Experience and Journal of Mrs. Jarena Lee, Our Nig, and Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House, the translations of these texts had practically no impact in the target context, the former having been carried out by Esther Sánchez-Pardo for a workshop of North American studies at the University of León and the two latter having been published by a currently extinct independent publishing house and translated by Carme Manuel, who has recurrently shown a deliberate interest in disseminating the works of African American women writers in the country.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The complexities imbricated in processes of reception of a literature permeated by a sociocultural reality so different from that of the target context are numerous and manifold. However, recollecting the backdrop of this study, it is a fact that recent international endeavors are evidencing the growing interest in studying the different forms of circulation of non-dominant literatures in translation.

This research has focused on the study of the translation history of African American women’s literature in Spain so as to explore the different factors involved in decisions governing the translation, publication and circulation of texts in a literary system. The data examined have shown the influence of external factors such as trends in national book markets and literary prizes, among others, on the reception of a foreign literature by a target community. However, our study has also evidenced the fact that agents in the Spanish publishing industry —both independent publishers and experts in the field such as Mireia Sentís or Carme Manuel— are making considerable efforts to rescue indispensable pieces and take a chance on contemporary authors. These new trends will hopefully redress or supplement the traditional biased and partial representation of a fundamental domain within the larger framework of US and universal literature.

However, the approach presented here is still only a rough introduction to the potentials of this field of research, which has yet to be exhaustively explored. Indeed, according to Andringa (2006: 529) tracing the translation history of a certain author or literature is only a first step in the study of their reception in a target culture. Thus, this undertaking may involve further elements of analysis such as critical reception, changes in meaning and representation and frames of reference. Consequently, this research work can only be conceived of as a modest contribution to a much larger field of study, hoping to serve as a springboard for upcoming endeavors within this domain.

In terms of future research directions, the database developed as the basis of this project will continue to be updated, as it is flexible enough to provide accurate representations of multiple data, opening up new frontiers for research into the translation and reception of African American literature. In this sense, some of the potentials of this research tool include expanding its scope to incorporate a) translations of male authors and/or b) secondary sources about African American literature published in Spain. Even if these potential modifications would inevitably complicate the task of building and maintaining a solid and reliable bibliographical tool, they would also open the door to consider further variables in the study of the translation and reception of this literature.

So far, AfroBib has provided unprecedented relevant data about the canon of African American women’s literature that is being shaped within the Spanish historiographical framework. As a research tool, it has proved to facilitate the analysis of the reception of African American women’s literature from the perspective of translation history as well as it has shed light into the relationships among different literary polysystems. These results are expected to map the space of black women’s literature and its reception as well as to encourage research on African American literature in Spain.

WORKS CITED

Alós, Ernest (2017): “Así ha quedado repartido el sector editorial tras ocho años de crisis”, El Periódico, July 13, n.p., <https://www.elperiodico.com/es/ocio-y-cultura/20170713/cifras-mercado-editorial-libro-espana-2016-6165929>.

Andringa, Els (2006): “Penetrating the Dutch Polysystem: The Reception of Virginia Woolf, 1920-2000”, Poetics Today, 27/3, 501-67.

Appadurai, Arjun (1996): Modernity at Large. Cultural dimensions of globalization, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Assis Rosa, Alexandra (2012): “A Long and Winding Road: Mapping Translated Literature in 20th Century Portugal”, Revista Anglo Saxonica, 3, 206-27.

Biblioteca Afro Americana de Madrid –BAAM– (2018): “(I) Colección BAAM –Biblioteca Afro Americana Madrid–” Radio Africa Magazine, June 27, <http://www.radioafricamagazine.com/la-biblioteca-afro-americana-madrid-baam/>.

Brems, Elke and Sara Ramos Pinto (2013): “Reception and Translation”, in Yves Gambier, and Luc van Doorslaer (eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies (Vol. 4), Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Bejamins, 142-47.

Caballero, Fátima (2017): “Arnaldo Otegi se reúne en Barcelona con Angela Davis” elDiario.es, October 10, <https://www.eldiario.es/politica/arlando-otegi-angela-davis-barcelona_1_3137323.html>.

CECC and CEAUL/ULICES (Updated 2019): Intercultural Literature in Portugal 1930 2000: A Critical Bibliography, Open-access database, <http://www.translatedliteratureportugal.org>.

Cornejo-Parriego, Rosalía (2020): Black USA and Spain: Shared Memories in the 20th Century, New York: Routledge.

Daniels, Lee, dir. (2009): Precious, Santa Monica: Lionsgate.

Demme, Jonathan, dir. (1998): Beloved, Burbank, CA: Buena Vista Pictures.

Fabre, Michel (1995): The French Critical Reception of African-American Literature: From the Beginnings to 1970 An Annotated Bibliography, Westport: Greenwood Press.

Federici, Eleonora and Vanessa Leonardi (2013): Bridging the Gap between Theory and Practice in Translation and Gender Studies, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Fernández-Ruiz, María Remedios (Updated 2019): BDÁFRICA, Open-access database, <http://www.bdafrica.eu/>.

Fernández-Ruiz, María Remedios, Gloria Corpas Pastor and Míriam Seghiri (2018): “Accommodating the third space in a fourth society: BDAFRICA, a groundbreaking source for the analysis of African literature reception in Spain”, International Journal of Iberian Studies, 31/2, 97-116.

Fillat, Nerea interviewed by Laura García (2020): “Espacios para el común. Sobre la edición independiente como alternativa de intervención cultural”, Master’s thesis, University of Granada.

Franco Aixelá, Javier (Updated 2020): BITRA (Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation), Open access database, <http://dti.ua.es/en/bitra/introduction.html>.

Gallego, Mar (2016): “Mapping Black Studies in Spain: New Methodologies and Empowering Critical Practices”, The ESSE Messenger, 25/1, 153-63.

Gallego, Mar, Ramón Espejo, Rafael Portillo and Antonio Rodríguez (2003): “Relaciones literarias entre España y el mundo anglosajón: pasado y presente”, in Ignacio Palacios Martínez, María José López Couso, Patricia Fra López, Elena eoane Posse (eds.), Fifty Years of English Studies in Spain (1952-2002): A Commemorative Volume. Actas del XXVI Congreso de AEDEAN, Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, 837-45.

Honeck, Mischa, Martin Klimke and Anne Kuhlmann (eds.) (2013): Germany and the Black Diaspora: Points of Contact, 1250 1914, New York and Oxford: Berghahn.

Kim, Ga-Hee (2015): “Raping Translation in Translating Rape: A Case Study of The Bluest Eye”, The Journal of English Cultural Studies, 8/2, 31-47.

Lécrivain, Claudine (2015): “Modalidades de la recepción en España de la literatura africana francófona (1980–2014)”, in Inmaculada Díaz Narbona (ed.), Literaturas hispanoafricanas: Realidades y contextos, Madrid: Verbum, 236 70.

Lécrivai, Claudine and Inmaculada Díaz Narbona (2009): “L’approche interculturelle d’un projet éditorial: littératures émergentes en espagnol”, Çédille, revista de estudios franceses, 5, 198 214.

Ledent, Bénédicte (2009): “Black British Literature”, in Dinah Birch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 7th ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 16 22.

Leonardi, Vanessa (2007): Gender and Ideology in Translation: Do Women and Men Translate Differently?. A Contrastive Analysis from Italian into English, Bern: Peter Lang.

Llopart Babot, Sandra (Updated 2020): AfroBib: A Bibliographic Database of African American Women’s Literature Published in Spain, Open access database, <http://afrobib.upf.edu/>.

Manuel, Carme interviewed by Hugo Cerdà (2009): “Experta en literatura y cultura norteamericana: Carme Manuel Cuenca”, Técnica industrial, December, <http://www.tecnicaindustrial.es/TIFrontal/a-2959-carme-manuel-cuenca.aspx>.

Marín Lacarta, Maialen (2012): “Mediación, recepción y marginalidad: Las traducciones de literatura china moderna y contemporánea en España”, PhD diss., Autonomous University of Barcelona.

MCD (Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte) (2017): Panorámica de la edición española de libros 2016, Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica. <https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/panoramica-de-la-edicion-de-libros-2016/edicion/21061C>.

MCD (Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte) (2018): El sector del libro en España. Abril 2018, Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica, <https://www.cegal.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/El-Sector-del-Libro-en-Espa%C3%B1a.-Abril-2018.pdf>.

Noia, Camiño (2004): “El ámbito de la cultura gallega”, in Francisco Lafarga and Luis Pegenaute (eds.), Historia de la Traducción en España, Salamanca: Ambos Mundos, 623-720.

Pons editorial team (Updated 2018): “Colección Read & Listen ¿Quiénes somos?”, Pons Idiomas, <https://ponsidiomas.com/categoria-producto/read-and-listen/>.

Poupaud, Sandra, Anthony Pym and Ester Torres Simón (2009): “Finding Translations. On the Use of Bibliographical Databases in Translation History”, Meta. Translators’ Journal, 54/2, 264-78, <https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/meta/2009-v54-n2-meta3238/037680ar/>.

Pujol, Josep, Josep Olervicens, Enric Gallén and Marcel Ortín (2004): “El ámbito de la cultura catalana”, in Francisco Lafarga and Luis Pegenaute (eds.), Historia de la Traducción en España, Salamanca: Ambos Mundos, 623-720.

Puxan-Oliva, Marta (2016): Espacios de fricción en la literatura mundial, Cambridge, MA: Instituto Cervantes at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Harvard University, <http://cervantesobservatorio.fas.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/020_informes_fricciones_literatura_mundial.pdf>.

Pym, Anthony (2014) [1998]: Method in Translation Studies, London and New York: Routledge.

Rabeie, Ati and S. G. Shafiee-Sabet (2011): “The Effect of the Translator’s Gender Ideology on Translating Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights”, Journal of Teaching Language Skills 3/3, 143-58.

Raphael-Hernandez, Heike (ed.) (2004): Blackening Europe: The African American Presence, New York and London: Routledge.

Reid-Pharr, Robert F. (2016): Archives of Flesh: African America, Spain, and Post Humanist Critique, New York: New York University Press.

Román, Blanca (2017): “Difusión y recepción en España de las escritoras africanas (1990-2010)”, PhD diss., University of Cádiz.

Santaemilia, José (2014): “Sex and Translation: On Women, Men and Identities”, Women’s Studies International Forum, 42, 104-10.

Sarasola, Beñat (2019): “Semblanza de la editorial Susa (1983- )”, MHLI-Memoria Histórica en Literaturas Ibéricas, <https://mhli.net/es/artxiboa/susa-arrese-grabatzen/>.

Sentís, Mireia (ed.) (2017): Cuerpo político negro, Madrid: Ediciones del Oriente y del Mediterráneo.

Sentís, Mireia (1998): En el pico del águila. Una introducción a la cultura afroamericana. Madrid: Árdora.

Spielberg, Steven, dir. (1985): The Color Purple, Burbank, CA: Warner Bros.

Tzu-Yi Lee, Elaine (2013): “Woman-Identified Approach in Practice: A Case Study of Four Chinese Translations of The Color Purple”, in Eleonora Federici and Vanessa Leonardi (eds.), Bridging the Gap between Theory and Practice in Translation and Gender Studies, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 75 85.

Van Doorslaer, Luc (2007): “Risking Conceptual Maps: Mapping as a Keywords Related Tool Underlying the Online Translation Studies Bibliography”, Target, 19/2, 217-33.

Whitaker, Forest, dir. (1995): Waiting to Exhale, Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox.

Zanettin, Federico, Gabriela Saldanha and Sue-Ann Harding (2015): “Sketching Landscapes in Translation Studies: A Bibliographic Study”, Perspectives, 23/2, 161-82, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0907676X.2015.1010551>.

* This work was carried out within the framework of the research project Portal digital de Historia de la Traducción en España, PGC2018-095447-B-I00 (MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE).

1 “Who does really know African American history, literature or thought? In order for one of its authors to be translated into our language, he or she must reach a level of dissemination in his or her country much higher than the average for normally translated writers. This means that, regarding genres such as the essay, there are hardly any collections of texts from the time of the civil rights struggle, which coincided with the rise of nationalism, black pride and the Black Power. We are, therefore, some forty years behind the African American cultural reality, or what is the same, the North American cultural reality.”

English translations are provided for all quotations of text originally published in Spanish. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s own.

2 “El gran interés cultural y político que ha despertado últimamente la literatura afroamericana en España.”

3 All the translated texts included in anthologies originally published in the target context (e.g. Cuerpo político negro [2017]) are treated as separate entries in the database. The title of the anthology is always specified next to the title of the target text.

4 These data were obtained from the online catalogues of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/) and the New York Public Library (https://www.nypl.org/).

5 This category was added to include further relevant information which did not fit in any of the selected criteria (e.g. paratextual information).

6 Actually, these volumes were published prior to the announcement of the Nobel laureates in 1993. After the announcement, the Spanish press praised the effort of Silvia Querini —Morrison’s editor in Spain— in promoting the circulation of Morrison’s works in the country precisely the same year that she reached the highest spheres of international recognition.

7 Note that the table, the figure and the subsequent discussion only consider published translations, rather than editions, per author.

8 “Still today, large publishers continue to publish the all-time canonical American authors, those who were already translated in the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s and 1960s; they make no effort to include in commercial collections new names and surround them with some kind of study, some kind of presentation”.

9 At this point it is important to highlight the fact that some publishing houses now belonging to the Planeta or Penguin Random House conglomerates were independent at the time of publication of the works included in AfroBib, so they have been considered as independent publishers for the purpose of our study.

10 “Catalan literature is now a regular recipient of new literary works in other languages, although it has to compete with a much larger Spanish-language publishing industry. [...] Catalan publishers only obtain satisfactory results when they manage to have their translation published before or simultaneous to the Spanish version, and at a similar selling price.”

11 See “Arnaldo Otegi se reúne en Barcelona con Angela Davis” (Caballero, 2017: n.p.).

12 The different genres have been established according to the categories used by the MCD in their Overview of Book Publishing in Spain with the objective of facilitating comparisons between the two sources.

13 Reports published by the MCD do not include information about the percentage of translated works by genre prior to 2013. Taking this as a starting point, we decided to use data from 2016 as a representative sample, as it was the year within the timespan available for analysis with the highest editorial activity as far as African American women’s literature is concerned.

14 “Our selection of stories follows several premises: firstly, they had to be suggestive but not too complex; secondly, they had to be miniature classics, those that are never forgotten, that must be read carefully, savoring every sentence, every word. In short, texts without which the history of literature would not be the same.”