:: MISCELÁNEA. Interpretación. Págs. 395-412 ::

“I Don’t Know, I’m Just the Interpreter”: A first approach to the role of healthcare interpreters beyond bilingual medical encounters

-------------------------------------

Cristina Álvaro Aranda

University of Alcalá

FITISPos-UAH Research Group

-------------------------------------

Research on role in healthcare interpreting has always been a recurrent theme in the literature, with a particular focus on the very act of the medical consultation. Consequently, the role that interpreters enact in other activities in which they also participate (e.g. accompanying patients) has comparatively received scant attention. This paper aims to contribute to a better understanding of the interpreter’s role in these areas. Drawing on participant observation, we examined the roles enacted by five healthcare interpreters in activities different to provider-patient consultations involving an interpreter that occurred over a period of five months in a Madrilenian hospital (Spain). Thematic analysis allowed for the identification of five emerging roles: mediator, patient advocate, institutional navigator, healthcare ambassador and conversation partner. A key finding is that most events in which interpreters of the sample participate take place outside consultations rooms, which makes it essential to shift the attention to the roles they play in these alternative events. Examining the role of interpreters in different activities within the realm of healthcare provision is essential to construct an accurate vision of what being just an interpreter really means.

palabras clave: healthcare interpreting, interpreter-mediated events, role, participant observation, thematic analysis.

«No lo sé, yo solo soy la intérprete»: primera aproximación al papel de los intérpretes sanitarios más allá de encuentros médicos bilingües

La investigación en torno al papel del intérprete sanitario siempre ha sido un tema recurrente en la bibliografía especializada, con especial énfasis en el marco de consultas médicas. Consecuentemente, se ha prestado una menor atención a su papel en otras actividades en las que también participan (p. ej. acompañamiento a pacientes). Este trabajo pretende contribuir a mejorar la comprensión sobre el papel del intérprete en dichas áreas. Mediante observación participante, se examinaron los papeles adoptados por cinco intérpretes sanitarios en actividades distintas a consultas interpretadas entre médico y paciente, que tuvieron lugar en un hospital madrileño a lo largo de cinco meses. El análisis temático permitió identificar cinco papeles emergentes: mediador, defensor del paciente, navegador institucional, embajador de la salud y compañero conversacional. Un resultado importante es que la mayor parte de las actividades con participación de intérpretes sanitarios de la muestra tienen lugar fuera de las salas de consulta, por lo que es esencial indagar en los papeles que desempeñan en estos espacios alternativos. Examinar el papel de los intérpretes en distintas actividades en el marco de la asistencia sanitaria es crucial para obtener una visión precisa de lo que verdaderamente significa ser solo un intérprete.

key words: interpretación sanitaria, actividades mediadas por intérprete, papel, observación participante, análisis temático.

-------------------------------------

recibido en abril de 2021 aceptado en noviembre de 2021

-------------------------------------

1. Introduction

A female healthcare interpreter accompanies a nineteen year old Burkinabé male patient to get an ultrasound done. She enters the patient’s number in the self-registration kiosk and prints out an appointment ticket. Afterwards, the interpreter waits with the patient until the appointment number is displayed on the screen. When they walk into the ultrasound room, the sonographer instructs the patient to lie down and asks the interpreter where his schistosomiasis is. To the provider’s astonishment, the interpreter cannot offer an answer and states: “I don’t know, I’m just the interpreter.” However, this reply does not seem to be clarifying enough. The sonographer frowns and inquires further: “Don’t you know anything about his medical history? So you’re just accompanying him? I thought we were going to have interpreters!” Extracted from a real dataset of interpreter-mediated interactions (Álvaro Aranda, 2020), this situation raises a much-needed, yet complex question: What does it mean to be just an interpreter?

Despite ever-increasing efforts to conceptualize the healthcare interpreter’s professional role(s), to date there is no consensus among stakeholders (Sleptsova et al., 2014). Inherently intertwined with the notion of (in)visibility (Shaffer, 2020), this debate commonly revolves around the existing tension between the role ascribed to interpreters in training, protocols and guidelines, and their behaviour in practice as involved participants deploying agency (Angelelli, 2020; Li et al., 2017; Martínez Gómez, 2015). As reported elsewhere (Álvaro Aranda, in press a), most research directly or tangentially addressing the issue of role focuses on the very act of interpreting in consultations in one or more medical specialties (Bridges et al., 2011; Butow et al., 2011; Gavioli, 2015; Penn et al., 2010; Simon et al., 2013; Zhan and Zeng, 2017; Roger and Code, 2018). In contrast, the interpreters’ role(s) beyond the recurrent discussions framed in these interactional spaces has somewhat been overlooked, but interpreters play indeed several roles outside consultation rooms that must be considered (Hsieh, 2007; Leanza et al., 2014; Parenzo and Schuster, 2019; Shaffer, 2020). This is particularly relevant in the light of specific employment contexts, task assignments and job descriptions requiring healthcare interpreters to perform tasks exceeding interpretation in medical consultations, such as guiding and accompanying patients and managing administrative procedures on their behalf (Angelelli, 2019; Bischoff et al., 2012; Martínez Ferrando, 2015; Swabey et al., 2016).

The present paper aims to investigate the roles played by healthcare interpreters in activities beyond interpretation in consultation rooms. Data come from participant observation of events involving a sample of five interpreters in a public hospital in Madrid, Spain. Section 2 addresses the concept of role as a theoretical background of the research, to subsequently describe some existing conceptualizations in the field of healthcare interpreting. Section 3 introduces the methodological framework, including a description of the participants and the procedure for analysis. After establishing different activities in which interpreters of the sample take part, thematic analysis (Pope et al., 2007; Braun and Clarke, 2021) allowed designing a classification tool involving five umbrella categories illustrating salient roles beyond medical consultations, which is subsequently used to organise data. Preliminary findings are described in Section 4 by means of pertinent examples. Lastly, the interpretation of the significant findings is provided in Section 5, whilst Section 6 briefly addresses the main conclusions.

2. A brief reflection on the role of the healthcare interpreter

A role is defined as “a set of behaviours that have some socially agreed upon function and for which there is an accepted code of norms” (Christiansen and Baum, 1997: 603). This implies that occupational roles are influenced by both individuals enacting them and external social expectations of their performance, which may change progressively with fluctuating skills, circumstances, and experiences (Turpin and Iwama, 2011). Thus, roles establish a combination of duties and privileges socially validated and understood: failure to meet these expectations entails an external perception of inadequacy for a specific role, whereas meeting them results in both validation and legitimisation in the eyes of society (Thomas and Wolfensberger, 1999). When established roles exist, they organise occupational behaviour and influence the activities comprising role performance routines (Reed and Nelson Sanderson, 1999), as defined roles serve as normative behavioural models for individuals in specific social interactions (Blesedell Crepeau et al., 2009).

As stated earlier, the construct of role in healthcare interpreting is still a highly controversial topic. In general terms, the healthcare interpreter’s role is to facilitate successful communication in linguistic and cultural discordant care. However, healthcare providers, patients, institutional bodies, healthcare entities, professional associations, and interpreters themselves have not reached an agreement regarding the tasks that such a process entails. This translates into a lack of socially shared expectations and definitions for the interpreter’s role that usually includes their level of (in)visibility (or (un)involvement). As Lázaro Gutiérrez (2014) indicates, better established sectors of the interpreting field (i.e. conference interpreting) favour impartiality and fidelity to the source message, but individuals benefiting from interpreting services may seek other solutions requiring a more active involvement. Unclear roles sometimes involve ambiguities and originate conflicts in work contexts (Jackson and Schuler, 1985). Whilst role ambiguity entails uncertainty with regard to formal roles, professional duties and appropriate behaviours (Bowling, 2017), role conflict occurs when incompatible demands are placed on individuals occupying more than one role at the same time (Kendall, 2007; Lauffer, 2011). In a similar direction, patient and provider expectations or requests may lead to deviations from what healthcare interpreting standards deem adequate professional practice (Lor et al., 2019), revealing a disconnect between theory/research and practice (Angelelli, 2020).

Empirical research shows professional (trained) and ad hoc interpreters performing tasks beyond interpretation. Although workplace expectations and restrictions influence the behaviour of interpreters, it is important to underline that they also need to accommodate interactional needs. Healthcare interpreters meet patients and providers coming from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds that interact with one another in asymmetric relationships. This power imbalance manifests itself in several dimensions, including expert and institutional knowledge, registers, use of language, and understanding of social and cultural norms (Álvaro Aranda, in press b). In such a context, merely transmitting utterances may not be enough to enable effective communication between participants and interpreters must often surpass their default role as language processors. Thus, they often expand their discretionary power to support the bilingual conversation by using strategies beyond their assignment (Granhagen Jungner et al., 2019). As institutional constraints and participants’ needs shift, interpreters adopt different roles that may become more or less critical to attain the desired outcomes. In this context, some authors consider the interpreter’s role to be dynamic and bound to change within the same interpreted event to cater for its specific demands (Bolden, 2020; Kilian et al. 2021; Major and Napier, 2019).

To cite some illustrative examples, healthcare interpreters may need to clarify cultural differences (Rosembaum et al., 2020) and institutional norms and/or procedures (Álvaro Aranda, 2020) that can hinder communication and delivery of care. In some cases, interpreters filter out messages when confronted with messages reflecting negative judgements of one of the participants (Seale et al., 2013). When acting as patient empowerers, healthcare interpreters elaborate on comments to improve understanding of medical procedures (Hsieh, 2013), whilst patient advocacy involves activities seeking the patient’s best interests, such as specifying their needs and preferences (Krystallidou et al., 2017), supervising their level of health literacy (Espinoza Suarez et al. 2020), or providing emotional support (Lara-Otero et al., 2019). In addition, interpreters serve as representatives for the public service (Parrilla Gómez, 2019) and may collaborate with clinicians by assisting them in history-taking (Davitti, 2019), attempting to (re)direct the patient’s responses towards the session’s goal (Mirza et al., 2017) or exploring ambiguous answers (Baraldi and Gavioli, 2018).

Role enactment is usually studied in the context of language-discordant medical consultations in primary and secondary care where all participants of the triad are normally present in the same physical space (e.g. Bridges et al., 2011; Butow et al., 2011; Gavioli, 2015; Penn et al., 2010; Seale et al., 2013; Simon et al., 2013; Zhan and Zeng, 2017; Roger and Code, 2018). Exceptions to this dominant trend in the literature are typically observed moments before doctors come in the consultation room or when the encounter has just finished. In this direction, and inspired by the notion of the in-between (Shaffer, 2020), we examined how interpreters conduct themselves before, during and after consultations when physicians are not present, which led to the establishment of different roles, such as advocate for the profession and confidant (Álvaro Aranda, in press a). For his part, Leanza (2005) noted that healthcare interpreters act as “welcoming” agents by performing greeting rituals culturally appropriate for families whilst they wait for the providers to arrive. In the context of bad-news consultations, interpreters may provide emotional support to patients once doctors have left the room (McDowell et al., 2011). Additionally, Hsieh (2013) reports another interesting scenario in which interpreters teach patients to request services available in the healthcare facility where they receive care.

Despite providing some insight into the role of the interpreter in scenarios leading to dyadic interaction with patients, these studies are mainly contextualised in medical encounters. However, research on healthcare workplaces illustrates how interpreters are involved in tasks different to medical consultations, including accompanying and guiding patients, or assisting them to complete administrative procedures (Álvaro Aranda, 2020; Angelelli, 2019; Bischoff et al., 2012; Martínez Ferrando, 2015; Swabey et al., 2016).

3. Methods

This paper aims to lend insight into the role(s) played by interpreters beyond the traditional discussions on the very act of the interpreted medical consultation. To approach this rather unaddressed area we adopted an exploratory and descriptive methodological framework intending to be a first approach to our object of study, which can be used as a point of departure for future studies involving a larger sample of participants and events.

3.1. Collection of data

All the data included in this paper are part of a doctoral research project examining potential differences in the performance of a sample of interpreters with varying levels of specialised training and professional experience in healthcare interpreting (Álvaro Aranda, 2020). Questionnaires, post-encounter interviews and fieldnotes were complemented with participant observation of interpreted events following a structured protocol specifically designed to capture nuances in behaviour in a descriptive manner. Prior to beginning the study, participants were informed about the research aims, the confidentiality of the data and their right to refuse or withdraw from participation at any given time. Consent was routinely obtained and conveniently registered. Given the highly sensitive nature of the setting in which the research was conducted, no audio or video footage could be obtained. Notwithstanding this, relevant excerpts could be gathered for analysis by means of manually written fieldnotes.

3.2. Participants and sample

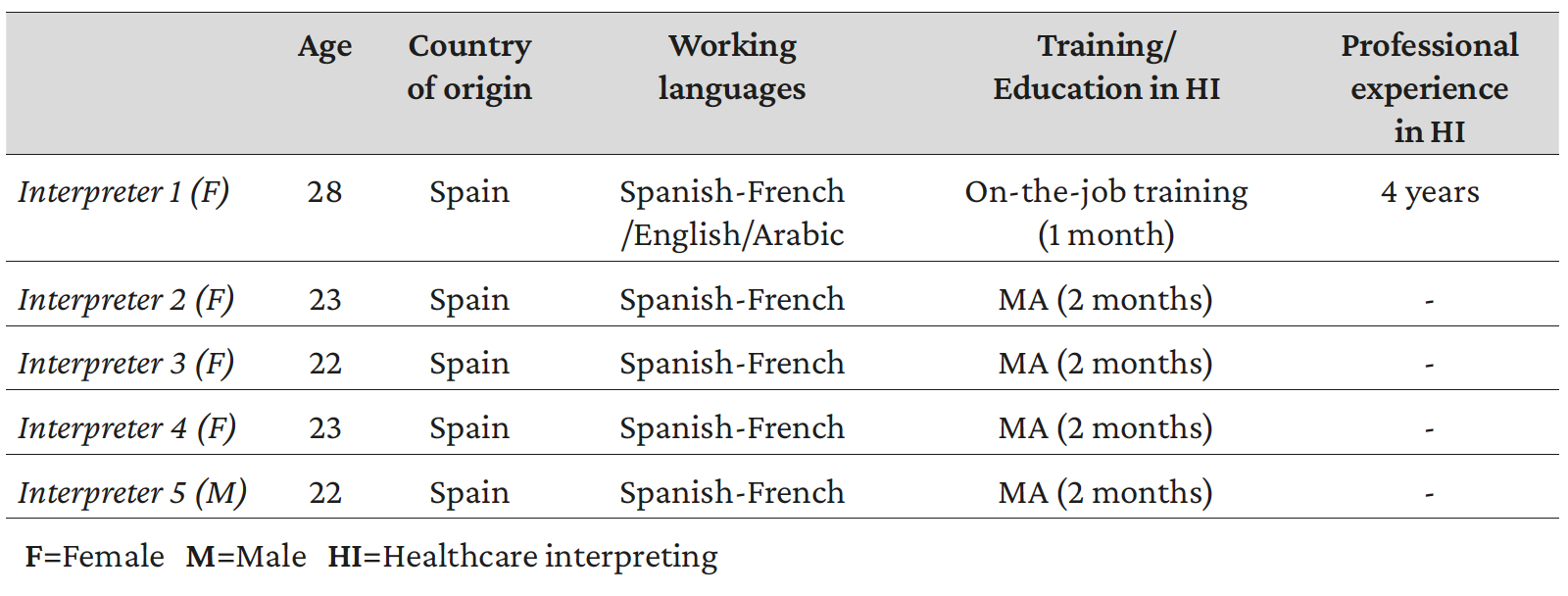

Data presented in this paper come from the observation, collection and organization of the activity of five interpreters. Table 1 shows information concerning their sociodemographic profile. Interpreter 1 was hired as a staff interpreter for the hospital where the study takes place, in which she worked for four years. To enhance her undergraduate education in translation and interpreting, she took on-the-job training on healthcare interpreting and intercultural mediation, Spanish bureaucracy and healthcare at national and local levels, ethical dilemmas and specialised terminology. Interpreters 2, 3, 4 and 5 were enrolled in the MA’s in Intercultural Communication, Interpreting and Translation in Public Services at the University of Alcalá (Madrid, Spain). All students compulsorily complete a specialised module in healthcare interpreting, in which they are introduced to medical terminology in specific fields, intercultural mediation, note-taking, modes of interpreting, ethical codes, etc. Students must participate in an internship programme lasting roughly 125 hours. Depending on their personal interests and prospective career path, they choose among different types of centres, such as hospitals, NGOs, police stations, courts, telephone interpreting companies, etc. Following the internship description, responsibilities of interns partaking in this study include interpreting in medical consultations and healthcare promotion workshops and, less frequently, translating informative materials. Since Interpreters 2, 3, 4 and 5 have no professional experience in healthcare interpreting, the internship allows them to build skills and gain practical knowledge before they enter the professional market.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Patients partaking in the study were predominantly male, Sub-Saharan economic immigrants (92.65%). Most participants aged between 15-30 years (58.82%) and were native speakers of African languages, but French was used as a lingua franca in most interpreted encounters. This is because French is spoken by all interpreters of the sample and the vast majority of patients, since their countries of origin used to be French colonies and this language enjoys official status. Regarding hospital staff, healthcare interpreters interact with two main groups: a first group of healthcare providers (i.e. nurses, consultants, resident physicians, laboratory assistants, and x-ray and ultrasound technicians) and a second group of staff members that are not directly involved in healthcare provision (e.g. administrative clerks, janitors, etc.). No sociodemographic information was collected in the case of hospital personnel.

3.3. Daily routine for healthcare interpreters

Patients generally arrive to the ward Tropical Medicine either alone or accompanied by an NGO worker. They hand in an appointment slip at the reception and then sit in the waiting area or stay in the corridor. If the appointment is scheduled in Tropical Medicine, providers usually approach the interpreters’ office to ask for help. When appointments require moving to another ward or building within the hospital complex, the secretary informs interpreters so at least one of them can meet the patient in the waiting area and accompany them to make sure they navigate the hospital without difficulty. Usually, interpreters also accompany patients to their appointments and assist them with administrative procedures. More precisely, they hand in appointment slips on behalf of patients, wait with them and walk them to the exit. To keep track of all interpreted sessions, interpreters must complete a form for every interpreted event, which reflects information about the patient’s sociodemographic profile, the provider’s familiarity with interpreting services and the activities performed. Lastly, both patients and healthcare providers are also asked to rate the interpreter’s level of performance.

3.4. Data analysis

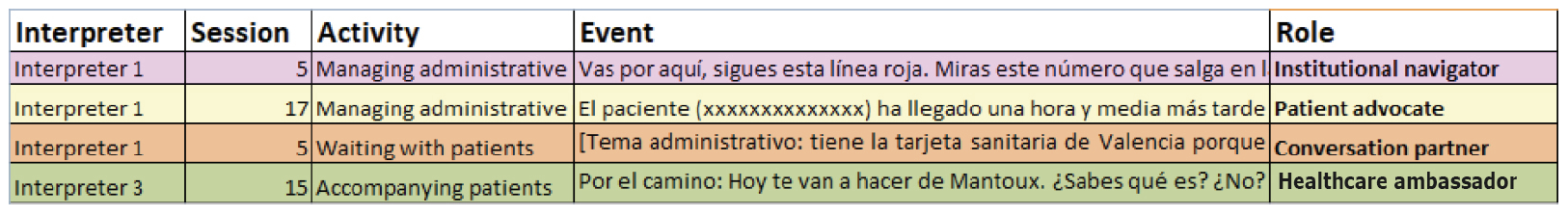

Written observational data were computerized using a text processing tool and a spreadsheet programme. As our object of study is a relatively unexplored area, our main focus was to identify meaningful patterned themes and structures to facilitate data organisation and subsequent analysis. For this reason, we followed the principles of thematic analysis (Pope et al., 2007; Braun and Clarke, 2021) to approach data, which allowed designing a coding scheme to 1) assemble tasks performed by interpreters beyond doctor/nurse- patient encounters and to 2) identify salient roles enacted by interpreters when carrying out these activities. These roles were examined and compared to results emerging from other studies previously described in Section 2. Closely related to the roles interpreters enact prior, mid and end of consultations as reported elsewhere (Álvaro Aranda, in press a), five major roles were identified in this study: institutional navigator, conversation partner, healthcare ambassador, mediator and patient advocate. In a subsequent phase, events were transferred to one of the roles proposed. It is important to underline that a fair number of examples sometimes presented areas of overlap and emerged concurrently, as interpreters were fulfilling several simultaneous roles. In such cases, we combined overlapping events into a single, dominant role according to their main association or the purpose the healthcare interpreter seemed to pursue. An example of data organisation and codification can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Data analysis and codification

4. Results

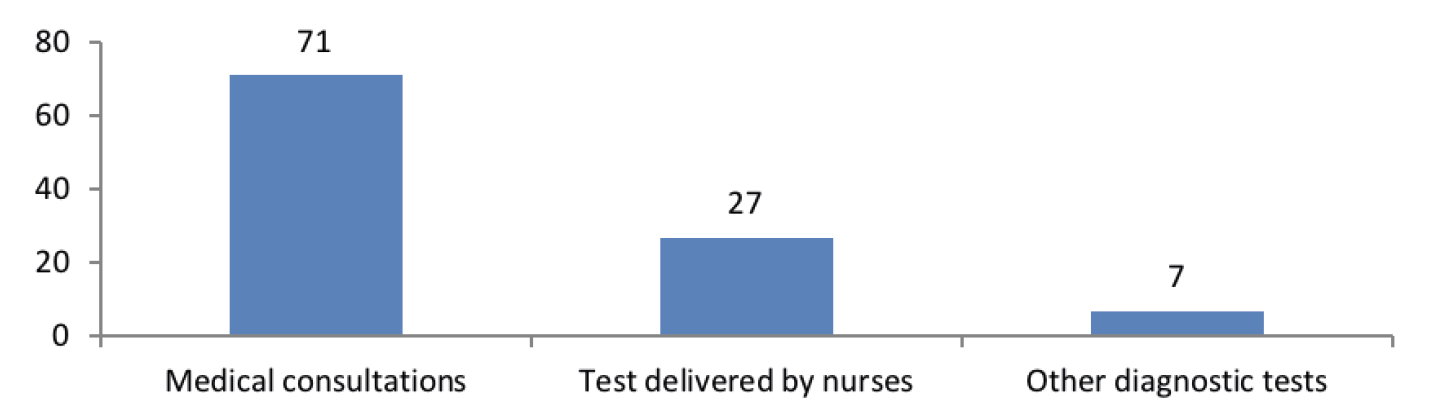

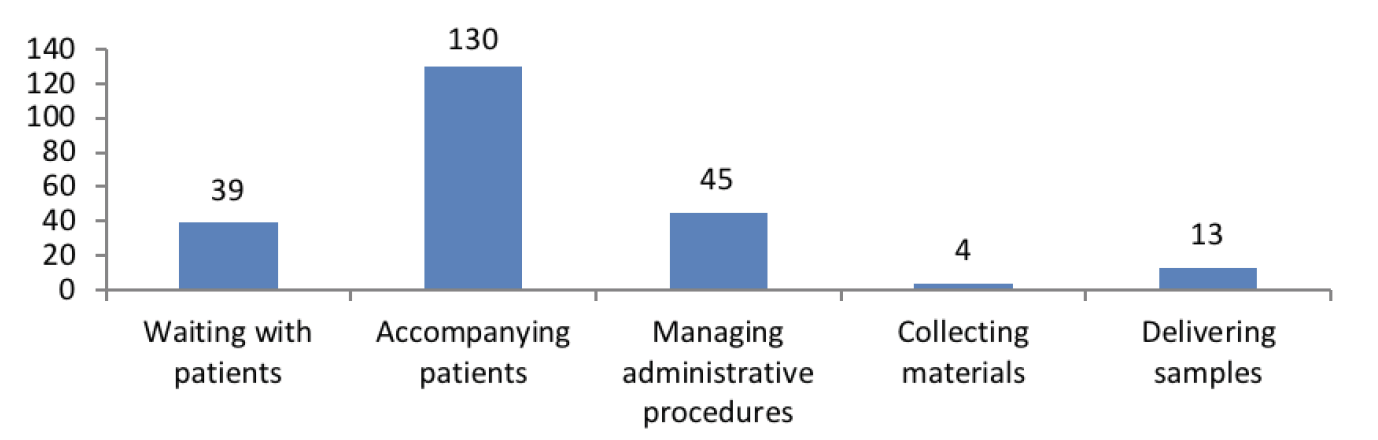

Healthcare interpreters of the sample took part in 336 events. As shown in Figure 2, 105 events (31.25%) involved interpreter-mediated interactions between non-Spanish speaking patients and Spanish-speaking doctors, nurses or other healthcare providers. Interpreters also participated in 231 events (68.75%) beyond medical consultations and diagnostic tests, as revealed in Figure 3. These activities include accompanying patients, waiting with patients, managing administrative procedures, delivering stool and/or urine samples and requesting stool and/or urine collection containers. A preliminary observation that can be drawn from our data is that most events in which interpreters participate occur outside consultation rooms, which calls for more focused research on the healthcare interpreter’s role outside medical encounters.

Figure 2. Interpreter-mediated interactions between patients-doctors/nurses/other HCPs* (n=105)

* HCP = Healthcare provider

Figure 3. Activities performed by healthcare interpreters different to medical consultations (n=231)

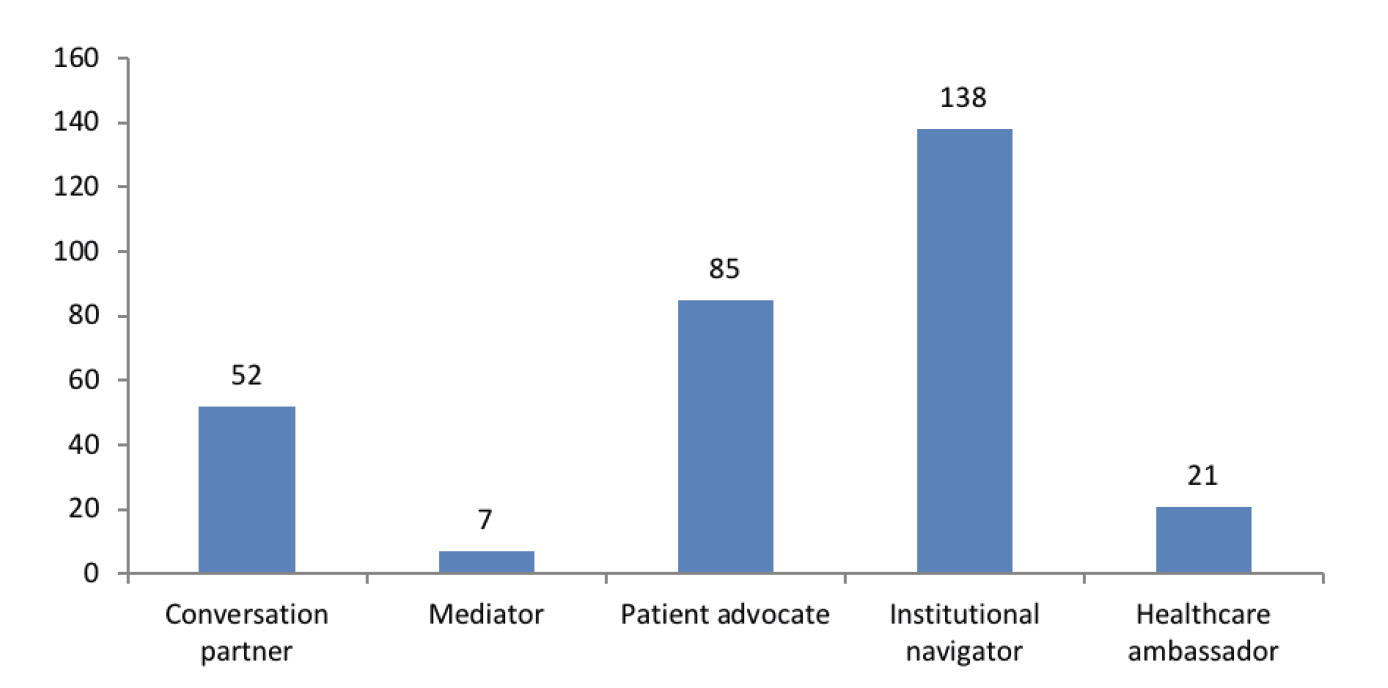

Following our aims, we examined the roles enacted by interpreters in the events shown in Figure 3. As previously described in Section 3.4., individual excerpts were first isolated and then coded and classified using thematic analysis, which allowed identifying salient roles different to the conduit role. The categories are as follows: institutional navigator (45.54%), conversation partner (17.16%), patient advocate (28.05%), healthcare ambassador (6.93%) and mediator (2.31%) (Figure 4). In line with the literature review, interpreters of the study sometimes shifted between two or more roles within the same communicative event. As stated earlier in the paper, overlapping cases are examined in relation to one role or another based on the main reason triggering the adoption of a specific role by interpreters, which concurs with the function intended to be illustrated. Selection of examples in the following sections is based on their relevance to the roles proposed and their potential to represent them. For reasons of clarity, excerpts will be translated into English.

Figure 4. Roles enacted by healthcare interpreters beyond consultation rooms (n=303)

4.1. The healthcare interpreter as a mediator

Patients attending healthcare facilities generally seek solutions to health concerns and experience different emotions, including uncertainty, fear, impatience, discouragement and anxiety. These feelings may trigger negative behavioural responses that are accentuated when the patient’s linguistic and cultural background comes into conflict with the norms governing the host health system. As culture influences how individuals perceive the world around them and interact with each other, interpreters commonly bridge cultural gaps that may prevent successful healthcare delivery, originate distrust among participants or lead to conflict. A particular example is provided in Excerpt 1:

Excerpt 1:

Interpreter 4: Regarde, c’est normal. Tout le monde le fait. Chaque tube va dans un laboratoire. Ils mesurent tes niveaux de sucre et d'autres substances et ça sert à détecter les maladies. Ton corps régénère le sang quand tu manges.

[Look, this is normal. Everyone does it. Each tube goes to a laboratory. They measure your levels of sugar and other substances and it serves to detect illnesses. Your body regenerates the blood when you eat]

Patient: Ce n'est pas normal. Aux États-Unis, en Amérique, ils n'en ont pris qu'un peu. Ce n'est pas normal, ce n'est pas normal, ce n'est pas normal…

[This is not normal. In the United States, in America, they only took a little bit. This is not normal, this is not normal, this is not normal…]

Interpreter 4: Ne t’inquiète pas. Ici, nous prenons soin de vous [the patients].

[Don’t worry. Here we take care of you]

Patient: Mais ils m'ont dit que je n'avais rien!

[But they told me I have nothing!]

Interpreter 4: Je sais. Mais certaines maladies se cachent et elles ne sont pas détectées avec un seul test. Il faut verifier.

[I know. But some illnesses conceal themselves and they are not detected with just a single test. It needs to be verified]

Excerpt 1 constitutes a clear example of intercultural mediation. Interpreter 4 accompanies an Ivorian male patient to have a blood test done. As blood is believed to have magical properties in Sub-Saharan cultures, the patient shows reluctance and even anger whilst they walk. This emotionally negative state is further accentuated by myths regarding blood collection in Western societies (e.g. illegal sale of blood). By acting as an intercultural mediator, the interpreter explains why several blood tests are sometimes requested to diagnose and rule out illnesses. In this case, it is also pertinent to note that Interpreter 4 aligns herself with the hospital and even the local health system outside the medical consultation (i.e. institutional use of we). This process of intercultural mediation allows the healthcare interpreter to explain how the Spanish health system works, which in turn serves to relax the patient and relieve his anxiety. Recognising and assuaging the patient’s negative emotions before the medical encounter may facilitate the provider’s work, since the healthcare interpreter has already addressed culturally-related concerns that can potentially complicate an adequate provision of care or the healthcare provider’s work.

Cultural gaps are not the only source of tension leading to mediation by healthcare interpreters. Other examples assembled in this category illustrate a different type of mediation. In line with findings reported by Seale et al. (2013) in diabetes review consultations, but this time outside medical encounters, interpreters sometimes face situations in which individuals voice negative judgements. These comments are uttered by providers or Spanish-speaking patients that happen to be in the same area as the patient and the interpreter. When enacting the role of moral mediator, interpreters soften the message or omit it completely to avoid conflicts and save the provider’s face. Excerpt 2 shows an interesting situation:

Excerpt 2:

Spanish-speaking patient 1: Este chico viene con ellas que serán de [xxxxxx] y yo esperando que soy diabética y van y le pasan antes. ¡Qué vergüenza! Tanto médico, tanta enfermera… ¿Qué pasa? Y yo soy mayor y diabética y no puedo más.

[This boy comes with them [the interpreter and the researcher] who must work for [xxxxxx] and I’m waiting and I’m diabetic and they go and see him first. How embarrassing! All these doctors, all these nurses… What’s going on? And I’m old and diabetic and I can’t take it any longer!]

Spanish-speaking patient 2: Tiene usted razón, señora.

[You’re right, madam]

[The interpreter omits the comment]

Excerpt 2 is framed in the first hospital visit of a young Ivorian male patient. Interpreter 2 accompanies the patient to the Admissions office so he can book his next appointment. When they arrive to the entrance, a Spanish speaking patient faints in the corridor. The person accompanying the patient screams for help and two nurses rush in to help. This situation negatively affects the patient’s emotional state and he bursts into tears. Interpreter 2 touches his arm reassuringly and asks him if he is okay. Afterwards, both approach the reception desk, where they are given a preference number. As a consequence, they approach another desk in virtually no waiting time. A Spanish-speaking female patient who allegedly has been waiting for some time complains out loud, causing another male patient to also manifest his discontent. Although the patient turns to the interpreter questioningly, she refuses to render these negative comments. Instead, she turns to the hospital administrative clerk who is going to schedule the patient’s appointment. Interpreter 2 explains in a post-encounter interview that she decided to omit the negative comment to avoid increasing the patient’s anxiety or hurting his feelings. However, and as noted by Seale et al. (2013), moral mediation may be problematic and does not come without risk. In this particular case, non-rendition of statements may cause the patient to feel out of the loop and also disempowered, as he cannot replicate.

4.2. The healthcare interpreter as a patient advocate

In this study, patient advocacy was associated to four main areas: adequate access to healthcare, fair use of healthcare resources, fulfilment of the patient’s rights and the (moral) duty to pursue the patient’s best interests. Examples of patient advocacy are particularly recurrent when healthcare interpreters accompany patients to deliver samples, request containers for stool and/or urine collection, or manage administrative procedures on their behalf. When advocating for patients, interpreters make sure patients receive free care or get urgent care appointments when referred by doctors. Other examples of patient advocacy include avoiding time conflicts between personal commitments and different medical appointments, and ensuring the latter are scheduled considering the healthcare interpreters’ working hours so the patient receives assistance to communicate with providers. In other cases, interpreters request documents needed for future visits (e.g. identification labels) and written instructions about medical tests or procedures in a language the patient can understand. This role is readily illustrated in Excerpt 3:

Excerpt 3:

Interpreter 1: Hola, vengo con este paciente. Ha llegado tarde por varios motivos y me preguntaba si le podéis pasar hoy.

[Hello. I come here with this patient. He’s arrived late for a series of reasons and I was wondering if he could be seen today]

Administrative staff: Sí, vale, le pasamos, pero tenéis que esperar.

[Yeah, okay, we will see him, but you need to wait]

Interpreter 1: Vale.

[Okay]

In Excerpt 3, Interpreter 1 must accompany a male patient to a Urology appointment. Since the patient arrives to the hospital an hour and a half late, the interpreter approaches the front desk and explains the situation to the administrative clerk. Instead of waiting for the patient to ask himself, she takes the initiative and makes sure that he can be seen by the doctor on the same day. Consequently, the appointment does not need to be rescheduled to a later date.

4.3. The interpreter as an institutional navigator

Increasingly complicated healthcare bureaucracies can create insurmountable barriers for (undocumented) immigrant patients and providers wanting to provide care for them (Hacker et al., 2015). In response to these difficulties, interpreters play a multifaceted role to help patients navigate bureaucratic mazes at both local and national level. When acting as institutional navigators, interpreters help patients understand the host society, which is represented by the hospital, and also make them norm-aware participants. This role is generally observed in patient accompaniment stages. Some examples of institutional navigation include welcoming patients and guiding them to different hospital wards and areas, such as the Admissions Office. Furthermore, interpreters inform patients about the location of specific wards in the hospital complex and the administrative procedures to be followed before receiving medical care (e.g. printing out appointment tickets using self-service hospital kiosks for patient check-in). In addition, interpreters provide explanations concerning internal rules of procedure and fixed sequences that must be strictly followed (e.g. bringing identification labels to appointments). As institutional navigators, interpreters teach patients how to get to the hospital using public transport and instruct them to perform specific activities for future visits, such as handing documents to the nurse. Excerpt 4 shows an illustrative example:

Excerpt 4:

Interpreter 1: Tu dois venir toujours avec tes autocollants ou ils ne te verront pas dans certaines consultations. (…) Maintenant, je vais imprimer ton papier pour la radiographie. Je te dirai où tu peux acheter de la nourriture et où aller pour que tu puisses y aller tout seul. (…) Tu viens par ici, tu suis la ligne rouge. Tu regardes ce numéro qui sera sur l'écran et quand tu le vois, tu entres dans la salle (…) et après tu as le prochain rendez-vous. Pour cela, tu suis la ligne blanche et c'est la même chose (…)

[You always need to come with your identification labels or they won’t see you in some consultations. (…) Now I’m gonna print out your document for the X-Ray. I’ll tell you where to buy food and where to go so you can go on your own. (…) You come this way, you follow the red line. You look at this number which will be on the screen and when you see it you go into the room (…) and then you have your next appointment. For this you follow the white line and it’s the same thing (…)]

In Excerpt 4, Interpreter 1 accompanies a Nigerian male patient to get an electrocardiogram done. He has not brought his identification labels, which are requested by the administrative clerk at the desk. The interpreter informs the staff that they will be back shortly and accompanies the patient to a different ward to print them. In the meantime, Interpreter 1 also explains to the patient that he always needs to bring his identification labels, as these are needed to identify him throughout his entire hospital experience. Once the test is done, the healthcare interpreter accompanies him to a different area and points out the steps he needs to follow in his next appointments, providing him with the necessary knowledge to navigate the hospital alone. In so doing, the healthcare interpreter is empowering the patient and also building up his self-trust to navigate administrative procedures, which in turn will favour his integration in the host society.

4.4. The interpreter as a healthcare ambassador

Low levels of health literacy may affect the patient’s level of understanding of medical terms, tests, procedures and instructions for treatment. This situation can be accentuated by cultural differences involving communication styles, attitudes towards medical care and expectations. When acting as healthcare ambassadors, interpreters facilitate medical information (e.g. what the tuberculin test is and the purpose of the test), provide specific instructions (e.g. fasting before a blood test), and also check the patient’s level of understanding by using the teach-back method (e.g. asking the patient a series of questions about the main points covered in a medical consultation to make sure there is no confusion or misunderstanding). In this sense, the role of healthcare ambassador includes role overlap between healthcare interpreters and providers, as both professionals strive to ensure that patients fully understand their condition and treatment plan. This is clearly seen in Excerpt 5:

Excerpt 5:

Interpreter 3: Dis-moi, à quelle heure tu te lèves?

[Tell me, when do you get up?]

Patient: Ben… cela dépend des jours.

[Well…It depends on the day]

Interpreter 3: Ok, disons 7h. Et tu dois faire pipi dedans, d'accord?

[OK, let's say seven o'clock. And you have to pee inside, okay?]

(...)

Interpreter 3: Alors, dis-moi, que feras-tu le 6 quand tu te lèveras le matin?

[So, tell me, what are you going to do on the 6th when you get up in the morning?]

(…)

Interpreter 3 accompanies a Burkinabe male patient to request a special container for a 24-hour urine collection test to assess his kidney function. An auxiliary nurse gives the patient a container and explains to him how to collect and store the sample. She also gives the patient an illustrated instruction sheet written in French. Pointing out the pictures to the patient, the interpreter uses the sheet to provide him with more detailed instructions whilst she walks him to the exit. To verify whether the patient has understood the information fully, Interpreter 3 asks him to explain to her what he is going to do and how he must do it to avoid contamination during the collection process, simultaneously creating an opportunity for the patient to ask questions about unclear points.

4.5. The interpreter as a conversation partner

Accompanying patients and waiting with them before their appointments gives patients and interpreters a chance to interact with each other. More precisely, interpreters deploy several strategies to make patients feel comfortable and establish a climate of trust. In this direction, interpreters of the sample participate in small talk, co-construct humour, and actively listen to the patient’s personal stories and concerns, including their migratory journey, traditional food, and cultural practices in their home country. Interpreters can also provide a certain degree of emotional and psychological support, as seen in the stages preceding Excerpt 2. Functioning as conversation partners, interpreters may (un)intentionally obtain medical information that patients may be initially reluctant to share with providers. In this sense, it is interesting to note that building rapport with patients may positively influence subsequent interpreted consultations (e.g. facilitating history taking in collaboration with the doctor). Nonetheless, this is not exempt from risk. More precisely, the role of conversation partner can lead patients to build unrealistic expectations about the interpreter’s role and their professional boundaries (Álvaro Aranda, in press a). This role is clearly illustrated in Excerpt 6:

Excerpt 6:

Patient: Quel âge as-tu ?

[How old are you?]

Interpreter 4: Vingt-trois ans.

[I’m twenty-three years old]

Patient: Et as-tu des enfants ?

[Do you have children?]

Interpreter 4: Non.

[No]

Patient: Pourquoi ?

[Why?]

Interpreter 4: Je suis très jeune.

[I’m very young]

[The patient laughs]

Patient: En Afrique, vous auriez déjà des enfants.

[You would already have children in Africa]

(...)

Patient: L'Afrique est très belle. Il y a beaucoup de richesses et les gens les exploitent. Je veux y retourner quand j'aurai assez d'argent.

[Africa is really beautiful. It has a lot of wealth and people exploit it. I want to go back there when I have enough money]

Interpreter 4 accompanies a male Guinean patient to get a blood test done. However, when they arrive to the cubicle in which blood is drawn, they are informed that the nurses are taking a rest break. As they need to wait, both patient and interpreter take a seat in the waiting room and engage in small talk to pass time. The patient explains African cultural traditions concerning motherhood to the interpreter and also shares his goals for the future.

5. Discussion of findings

Following previous research indicating that healthcare interpreters participate in activities beyond medical consultations (Álvaro Aranda, 2020; Angelelli, 2019; Bischoff et al., 2012; Martínez Ferrando, 2015; Swabey et al., 2016, etc.), this paper focuses on the concept of role beyond the common discussions of triadic interactions between doctors, patients and interpreters. With this aim, we used an exploratory approach to examine the behaviour of five interpreters in activities different to interpreted consultations observed in a Madrilenian hospital (Spain) over five months.

Our analysis reveals that facilitating communication in language-discordant medical consultations is only a small part of the activities performed by interpreters in this study, as they participated in 68.75% events other than consultations and diagnostic tests. These include delivering stool and/or urine samples, requesting stool and/or urine collection containers, managing administrative procedures, accompanying patients and waiting with them (Figure 3). In the context of the present study, this means that the healthcare interpreter’s assignment does not end when a consultation is finished and, as a consequence, greater attention should be paid to the issue of role in other professional activities also occurring in multicultural and multilingual healthcare settings.

Drawing on thematic analysis, we identified five roles different to the conduit role in these events: institutional navigator (45.54%), conversation partner (17.16%), patient advocate (28.05%), healthcare ambassador (6.93%) and mediator (2.31%). Nonetheless, these categories are not necessarily uniform, as healthcare interpreters of the sample adopt several (and overlapping) roles within the same communicative event to accommodate interactional and participants’ needs, institutional constraints, and workplace expectations that may bring them out of the invisible role some interpreting circles still prescribe. This supports the literature on “role changeability”, which suggests that choice of role is changeable, dynamic and contextually-bound (Bolden, 2020; Kilian et al. 2021; Major and Napier, 2019, etc.). Our findings also serve to broaden these previous studies, since interpreters of the sample also move back and forth between different roles depending on the needs of unfolding interactions outside consultations.

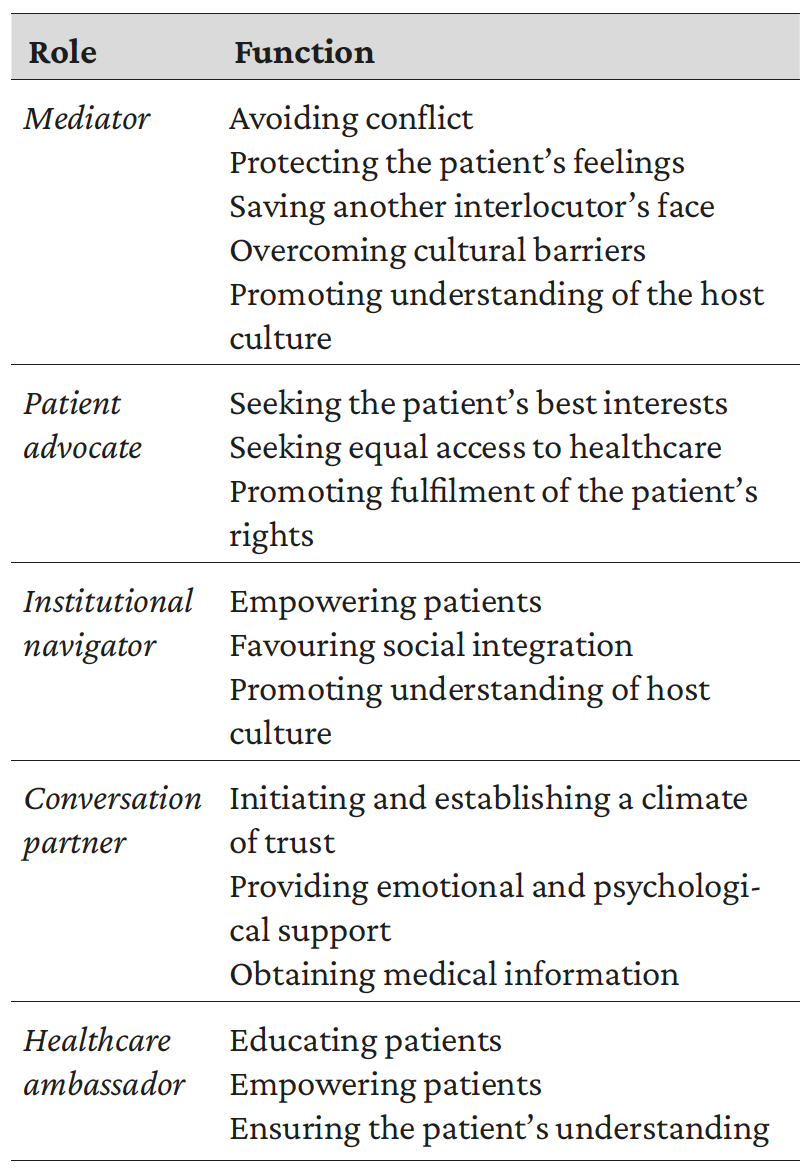

In addition, the roles observed in this study resonate with existing findings tangentially addressing events outside medical consultations, in which interpreters facilitate medical information, provide emotional support, favour social integration and empower patients in different ways (e.g. Hsieh, 2013; Leanza, 2005; McDowell et al., 2011). More interestingly, the proposed categories also apply to research focusing on the interpreter’s role in the course of medical consultations. For instance, the role of mediator encompasses both moral (Seale et al., 2013) and intercultural mediation (Rosenbaum et al., 2020; Sleptsova et al., 2014). On the other hand, examples of patient advocacy as understood in the present paper are equally reported in Hsieh (2013) and Krystallidou et al. (2017), whereas the role of healthcare ambassador covers strategies also observed by Espinoza Suarez et al. (2020). Examples of emotional support observed under the category of conversation partner coincide with results obtained by Lara-Otero et al. (2019), whilst the role of institutional navigator is also seen midconsultation (Álvaro Aranda, 2020). In summary, shifting attention from the traditional focus on consultations to a different repertoire of tasks performed by interpreters, our findings reveal that they perform important functions beyond interpretation that are summarised in Table 2. It is interesting to indicate that these roles are generally observed in dyadic interaction between patients and interpreters. Consequently, they might be labelled as patient-oriented roles.

Table 2. Roles and functions beyond interpreter-mediated medical consultations

Our research is not without limitations. The results are only preliminary because they are based on a small interpreter population given the exploratory nature of the study. As a consequence, it is necessary to enrol more participants in prospective research to confirm our findings. Furthermore, we only focused in depth on a specific healthcare facility in a given country. This irremeably implies that roles frequently observed in this paper may be anecdotic or irrelevant in different contexts. As stated earlier, the interpreter’s role(s) is shaped and constrained by the institutional and interactional context in which the activity is embedded. For this reason, future research should be conducted in other countries and institutions, ideally involving patients and interpreters with varying origins and cultural roots. In addition, complementary research is needed to shed light on potentially conflictive aspects that may have an influence both in and beyond consultations (see Excerpt 2).

6. Conclusions

This paper started with a reflection about what being just an interpreter means. To this date, there is still no agreement concerning the role that healthcare interpreters need (or are expected) to play in their professional life. However, what seems to be clear from our findings is that the set of problems that they need to solve in their daily practice goes beyond facilitating communication in medical consultations. Thus, complementary research on the issue of role in these other activities is needed to advance knowledge on how interpreters behave and build their professional identity in the wide array of situations and activities occurring in healthcare settings.

REFERENCES

Álvaro Aranda, Cristina (2020): Formación y experiencia profesional como diferenciadores en la actuación de intérpretes sanitarios: un estudio de caso desde la sociología de las profesiones. Unpublished PhD dissertation: University of Alcalá.

Álvaro Aranda, Cristina (in press a): “Beyond Medical Consultations: Examining the (In)visible Role of Healthcare Interpreters in the ‘In-Between’.”

Álvaro Aranda, Cristina (in press b): “Humour Functions and Transmission in Interpreted Healthcare Consultations: An Exploratory Study.” Resla. Revista Española de Lingüística Española/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics.

Angelelli, Claudia (2020): “Community/Public-Service Interpreting as a Communicative Event. A Call for Shifting Teaching and Learning Foci”, Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 6/2, 114-130. doi: 10.1075/ttmc.00048.ang.

Angelelli, Claudia V. (2019): Healthcare interpreting explained, Oxon and Nueva York: Routledge.

Baraldi Claudio, and Laura Gavioli (2018): “Managing Uncertainty in Healthcare Interpreter-Mediated Interaction: On Rendering Question-Answer Sequences”, Communication and Medicine, 15/2, 150-164. doi: 10.1558/cam.38677.

Bischoff, Alexander, Elisabeth Kurth, and Alix Henley (2012): “Staying in the Middle. A Qualitative Study of Health Care Interpreters’ Perceptions of their Work”, Interpreting, 14/1: 1-22. doi: 10.1075/intp.14.1.01bis.

Blesedell Crepeau, Elisabeth, Ellen S. Cohn, and Barbara A. Boyt Schell (2009): Willard’s & Spackman’s Occupational Therapy. 11th Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Bolden, Galina B. (2020): “Understanding Interpreters’ Actions in Context”, Communication and Medicine, 15/2, 135-149. doi: 10.1558/cam.38678.

Bowling, Nathan (2017): “Role Conflict”, in Steven G Rogelberg (ed.), The Sage Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke (2021): Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Doing, Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Bridges, Susan M., Cynthia K. Y. Yiu, and Colman P. McGarth (2011): “Multilingual Interactions in Clinical Dental Education: A Focus on Mediated Interpreting”, Communication & Medicine, 8/3, 197-210. doi: 10.1558/cam.v8i3.197.

Butow, Phyllis, Melanie Bell, David Goldstein, Ming Sze, Lynley Aldridge, Sarah Abdo, Michelle Mikhall, Skye Dong, Rick Iedema, Ray Ashgari, Rina Hui and Maurice Eisenbruch (2011): “Grappling with Cultural Differences; Communication between Oncologists and Immigrant Cancer Patients with and without Interpreters”, Patient Educ Couns, 84/3, 398-405. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.035.

Christiansen, Charles, and Caroly Baum (eds.) (1997): Occupational Therapy: Enabling Function and Well-Being. Thorofare: Slack.

Davitti, Elena (2019): “Healthcare Interpreting”, in Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha (eds.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. 3rd edition. Abingdon: Routledge.

Espinoza Suarez, Nataly, Meritxell Urtecho, Samira Jubran, Mei-Ean Yeow, Michael E. Wilson, Kasey R. Boehmer, and Amelia K. Barwise (2020): “The Roles of Medical Interpreters in Intensive Care Unit Communication: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22/2, 1100-1108 <doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.10.018>.

Gavioli, Laura (2015): “On the Distribution of Responsibilities in Treating Critical Issues in Interpreter-Mediated Medical Consultations: The Case of ‘Le Spieghi(amo)’”, Journal of Pragmatics, 76, 169-180. <http://hdl.handle.net/11380/1061241>.

Granhagen Jungner, Johanna, Elisabet Tiselius, Klas Blomgren, Kim Lützén, and Pernilla Pergerta (2019): “The Interpreter’s Voice: Carrying the Bilingual Conversation in Interpreter-Mediated Consultations in Pediatric Oncology Care”, Patient Education Counselling, 102/4, 656-662. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.029.

Hacker, Karen, Maria Anies, Barbara L. Folb, and Leah Zallman (2015): “Barriers to Health Care for Undocumented Immigrants: A Literature Review”, Risk Management Healthcare Policy, 8, 175-183. doi: 10.1177/1363461520933768.

Hsieh, Elaine (2007): “Interpreters as Co-Diagnosticians: Overlapping Roles and Services between Providers and Interpreters”, Social Science & Medicine, 64/4, 924-937. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.015.

Hsieh, Elaine (2013): “Health Literacy and Patient Empowerment: The Role of Medical Interpreters in Bilingual Health Care”, in Mohan J. Dutta, and Gary L. Kreps (eds.): Reducing health disparities: communication intervention, New York: Peter Lang, 35-58.

Jackson, Susan E., and Randall S. Schuler (1985): “A Meta-Analysis and Conceptual Critique of Research on Role Ambiguity and Role Conflict in Work Settings”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36/1, 16–78. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(85)90020-2.

Kendall, Diana (2007): Sociology in Our Times: The Essentials, Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Kilian, Sanja, Leslie Swartz, Xanthe Hunt, Ereshia Benjamin, and Bonginkosi Chiliza (2021): “When Roles within Interpreter-Mediated Psychiatric Consultations Speak Louder than Words”, Transcultural Psychiatry, 58/1, 27-37. doi: 10.1177/1363461520933768.

Krystallidou, Demi, Ignaas Devish, Dominique Van de Velde, and Peter Pype (2017): “Understanding Patient Needs without Understanding the Patient: The Need for Complementary Use of Professional Interpreters in End-of-Life Care”, Medicine Health Care and Philosophy, 20/4, 477-481. doi: 10.1007/s11019-017-9769-y.

Lara-Otero, Karlena, Jon Weil, Claudia Guerra, Janice Ka Yan Cheng, Janey Youngblom, and Galen Joseph (2019): “Genetic Counselor and Healthcare Interpreter Perspectives on the Role of Interpreters in Cancer Genetic Counseling”, Health Communication, 34/13, 1608-1618. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1514684.

Lauffer, Armand (2011): Understanding your social agency, Thousand Oaks and London: Sage.

Lázaro Gutiérrez, Raquel (2014): “Use and Abuse of an Interpreter”, in Carmen Valero Garcés, Bianca Vitalaru, and Esperanza Mojica López (eds.): (Re)considerando ética e ideología en situaciones de conflicto=(Re)visiting ethics and ideology in situations of conflict, Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá, 214-221.

Leanza, Yvan (2005): “Roles of Community Interpreters in Pediatrics as Seen by Interpreters, Physicians and Researchers”, Interpreting, 7/2, 167-192. doi: <10.1075/intp.7.2.03lea>.

Leanza, Yvan, Alessandra Miklavcic, Isabelle Boivin, and Ellen Rosenberg (2014): “Working with Interpreters”, in Laurence Kirmayer, Jaswant Guzder, and Cécile Rousseau (eds.), International and cultural psychology. Cultural consultation: Encountering the other in mental health care, Springer Science + Business Media, 89-114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7615-3_5.

Li, Shuangyu, Jennifer Gerwing, Demi Krystallidou, Angela Rowlands, Antoon Cox, and Peter Pype (2017): “Interaction-A Missing Piece of the Jigsaw in Interpreter-Mediated Medical Consultation Models”, Patient Education and Counseling, 100/9, 1769-1771. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.04.021.

Lor, Maichou, Barbara J. Bowers, and Elizabeth A. Jacobs (2019): “Navigating Challenges of Medical Interpreting Standards and Expectations of Patients and Health Care Professionals: The Interpreter Perspective”, Qualitative Health Research, 29/6, 820-832. doi: 10.1177/1049732318806314.

Major, George, and Jemina Napier (2019): “'I'm There Sometimes as a Just in Case'”: Examining Role Fluidity in Healthcare Interpreting”, in Meng Ji, Mustapha Taibí, and Ineke H. M. Cracee Multicultural Health Translation, Interpreting and Communication. London and New York: Routledge, 183-204. doi: <10.4324/9781351000390>.

Martínez Ferrando, Cristina (2015): Interpretación médica: de la teoría a la práctica a partir de estudios de caso. (Masters’ Dissertation. Universitat d’Alacant) < http://hdl.handle.net/10045/62008>.

Martínez Gómez, Aída (2015): “Invisible, Visible or Everywhere in Between? Perceptions and Actual Behaviors of Non-Professional Interpreters and Interpreting Users”, The Interpreters' Newsletter, 20, 175-194. < https://www.openstarts.units.it/handle/10077/11859>.

McDowell, Liz, DeAnne K. Hilfinger Messias, and Robin Dawson Estrada (2011): “The Work of Language Interpretation in Health Care: Complex, Challenging, Exhausting, and Often Invisible”, Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22/2, 137-147. doi: 10.1177/1043659610395773.

Mirza, Mansha, Elizabeth A. Harrison, Hui-Ching Chang, Corrina D. Salo, and Dina Birman (2017): “Making sense of three-way conversations: A qualitative study of cross-cultural counseling with refugee men”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 56, 52-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.12.002.

Parenzo, Sarah, and Michal Schuster (2019): “The Mental Health Interpreter: The “Third Space” between Transference and Counter-Transference”, in Izabel E.T. de V. Souza, and Effrossyni Fragkou (eds.), Handbook of Research on Medical Interpreting, Hershey: IGI GLOBAL, 276-289.

Parrilla Gómez, Laura (2019): La interpretación en el contexto sanitario: aspectos metodológicos y análisis de interacción del intérprete con el usuario. Berlin: Peter Lang.

Penn, Claire, Jennifer Watermeyer, Tom Koole, Janet de Picciotto, Dale Ogilvy, and Mandy Fisch (2010): “Cultural Brokerage in Mediated Health Consultations: An Analysis of Interactional Features and Participant Perceptions in an Audiology Context”, JIRCD Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders, 1, 135-156.

Pope, Catherine, Nicholas Mays, and Jennie Popay (2007): Synthesizing Qualitative and Quantitative Health Evidence. A Guide to Methods, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Reed, Kathlyn L., and Sharon Nelson Sanderson (1999): Concepts of Occupational Therapy. 4th edition. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Roger, Peter, and Chris Code (2018): “Interpreter-Mediated Aphasia Assessments: Mismatches in Frames and Professional Orientations”, Communication & Medicine, 15/2, 233-244. doi: 10.1558/cam.38680.

Rosenbaum, Marc, Richard Dineen, Karen Schmitz, Jessica Stoll, Melissa Hsu, and Priscila D. Hodges (2020): “Interpreters’ Perceptions of Culture Bumps in Genetic Counseling”, Journal of Genetic Counseling, 29.3. 352-364. <doi: 0.1002/jgc4.1246>.

Seale, Clive, Carol Rivas, Hela Al-Sarraj, Sarah Webb, and Moira Kelly (2013): “Moral Mediation in Interpreted Health Care Consultations”, Social Science and Medicine, 98, 141-148. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.014.

Shaffer, Laurie (2020): “In-between: An Exploration of Visibility in Healthcare Interpreting”, in Izabel E.T. de V. Souza, and Effrossyni Fragkou (eds.), Handbook of Research on Medical Interpreting, Hershey: IGI GLOBAL, 188-208.

Simon, Melissa A., Daiva M. Ragas, Narissa J. Nonzee, Ava M. Phisuthikul, Thanh Ha Luu, and XinQi Dong (2013): “Perceptions of Patient-Provider Communication in Breast and Cervical Cancer-Related Care: A Qualitative Study of Low-Income English- and Spanish-Speaking Women”, Journal of Community Health, 38/4, 707–715. doi: <10.1007/s10900-013-9668-y>.

Sleptsova, M., Gertrud Hofer, Naser Morima, and Wolf Langewitz (2014): “The Role of the Health Care Interpreter in a Clinical Setting-A Narrative Review”, Journal of Community Health Nursing, 31/3, 167-184. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2014.926682.

Swabey, Laurie, Todd S. K. Agan, Christopher J. Moreland, and Andrea M. Olson (2016): “Understanding the Work of Designated Healthcare Interpreters”, International Journal of Interpreter Education, 8/1, 40-56. <https://www.cit-asl.org/>.

Thomas, Susan, and Wolf Wolfensberger (1999): “An Overview of Social Role Valorization”, in Robert J. Flynn and Raymond A. Lemay (eds.), A Quarter-century of Normalization and Social Role Valorization: Evolution and Impact, Otawa: University of Ottawa Press, 125-160.

Turpin, Merrill, and Michael K. Iwama (2011): Using Occupational Therapy Models in Practice. A Field Guide. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone. Elsevier.

Zhan, Cheng, and Lishan Zeng (2017): “Chinese Medical Interpreters’ Visibility through Text Ownership. An Empirical Study on Interpreted Dialogues at a Hospital in Guangzhou”, Interpreting, 19/1, 97-117, doi: 10.1075/intp.19.1.05zha.