1. Introducción

Today, we can find on the internet a wide range of audiovisual contents subtitled into several languages. The easiness in downloading them and the fact that they are very often free of charge surely plays a major role on the relevancy that such translated texts have been achieving in contemporaneity. It is certainly a plus that, through subtitling, people can watch movies, sitcoms or other programs originally from different regions of the globe rewritten in their mother tongue (for the notion of «rewriting», see Lefevere, 1992: 2). Besides the exchange of cultural products, subtitling contributes for the acknowledgment of the Other as he is, i.e., as he speaks and behaves. It benefits language learning as well: we can learn a foreign language (which we listen to) at the same time we improve our skills in our own language (which we read on the screen). Ultimately, it is a cultural practice and both Portugal and Brazil are two examples of countries where it presents a strong cultural significance: subtitling, rather than dubbing, has been the most usual kind of AVT practiced by the national broadcasters throughout the years, not to mention that it is also the most familiar to the general public (as explained by Sequeira 2019, Sustelo 2016 and Nobre 2013).

Along with the work produced by translators and translational companies operating online, on digital subtitling platforms we can find contents which were rewritten by TV and/or cinema enthusiasts as well. For the aim of this study, I will consider them as non-professional translators: people who are not paid for their translated versions, who do not necessarily have a background in translation and who pursue the task essentially by pleasure, at their homes, with their own technical devices and relying on their personal skills in both the foreign and the target languages —circumstances and characteristics that are generally very different compared to professional contexts. To distinguish both spheres —the professional and the non-professional—, I will assume as one of my references the study that I developed about the Portuguese public broadcaster, RTP (Dias Sousa 2020), in which I had the possibility of interviewing the directors of the translation department and some of the translators integrated in its several subsections. Relevant to this article is, for example, what Aníbal Costa (2016), responsible for the division of media production planning, explained about how the AVT processes usually start: by a previously settled contract between the medium and the entity that holds the legal rights over the contents. Even though there are some exceptions, as part of the negotiation, they are normally made available for translation with a written script in one of the working languages at RTP —at least, in English or in French, especially if the source language is less common in the target context, as, for example, Norwegian or Japanese (Dias Sousa 2020: 476). Teresa Sustelo (2016), former head of the department, confirmed that the access to the source script is rather significant in the whole translational work, to the extent that it can determine the direction followed by each translator and, consequently, the accuracy of their translated versions. Therefore, we may say that the possibility of relying on the source texts, which is significantly higher in professional contexts, is not only a difference, but also a major advantage compared to amateur AVT environments.

Another differentiation can be pointed out in the linguistic particularities of the source texts. Williamson and de Pedro Ricoy (2014: 164) claim that, in subtitling, translators are «faced with recreating complex phenomena», such as wordplay or humour, given that the linguistic features have to be exploited «against a background of culturally shared knowledge». In the case of Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis, we may consider that the complexity involved in the translational work is rather high: the narrative is based on the Ch’ti community’s traits and the humour results from the exaggeration of some of its most peculiar characteristics, namely the dialect spoken by the inhabitants of Lille, in Northern France, which deviates very significantly from the French norm. That is to say that any translator of the film is not only challenged by the reproduction of the humoristic intention, but also with the correct understanding of the characters’ lines and interactions. Subsequently, not even being proficient in French might be enough for an accurate translation of the source content. Most of all, it would imply sensitivity —something that, according to Fernanda Porto and Helena Florêncio (2016), two of the subtitling translators working at RTP, can only be developed through years of practice and experience in the field. To Helena Florêncio, sensitivity is essential whenever what is said by the characters does not make sense in the scene once translated, and, in Fernanda Porto’s opinion, it is the most important attribute of an AVT translator, far more than a «firm hand» («mão firme») to insert the subtitles in the software. As they stated:

Fernanda Porto: In theory, we must appeal considerably to our sensitivity… To me, it is more important the sensitivity than a firm hand, because we can practice our hand… Sometimes, we need to call ‘stone’ to a stick. It happened to me once: ‘ah, why did you call it a ‘stone’?’ ‘Because, in the following line, I was going to play with the word ‘stone’, not with the word ‘stick’. Therefore, that had to be the option. He [the character] was telling a joke and I needed to tell a joke as well! It couldn’t be exactly the same, because we didn’t have an equivalent in our language. Sometimes, it’s complicated. So, bottom line, it all depends on our sensitivity.

Helena Florêncio: This was how I learned… I have an idiom in English, which I may even know, but I look to the narrative and I think: ‘no, that can’t be the translation. It can’t be that’. Thus, I developed the sensitivity to understand: ‘there is something more’… Through the story, sometimes we notice that there isn’t a straight translation. Yet, based on the whole idea, we realize: ‘maybe, this is what they’re saying’. And that’s it! We don’t know everything, but, with time, our experience helps us in our task.

(Porto and Florêncio 2016, my translation).

I am aware that the French comedy Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis has been studied by several researchers – to name a few examples, by Gentile and van Doorslaer (2019), who analysed the reproduction of the North-South cultural representation in the Italian context (namely, in the remake Benvenuti al Sud); by Garcia-Pinos (2017), who studied the Spanish and the Catalan translations both in the form of dubbing and subtitling, reflecting over the construction of a dialect as a translational strategy; by Williamson and Ricoy (2014), who concentrated on the subtitling of wordplay into English; by Rȩbkowska (2011, 2014), who analysed the stereotyped image of the inhabitants of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, as well as the recreation of humourous effects in the Polish translation; not to mention Ellender (2016), who compared the English subtitles of Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis to those created for the comedy Rien à declarer by the same translator —Michael Katims—, focusing on the fact that, in both, humour was linguistically and culturally-oriented (ibid.: 2); besides Reutner (2013), who pondered about the challenges posed by dialects in dubbing, choosing the Spanish context as her case study. In this article, my only intention is to contribute to the acknowledgement of a significantly defiant and interesting object for Translation Studies as it is the comedy about the Ch’tis, especially in what it unveils about translation as a cultural and a social act. I hope to succeed in such an aim by adding a new perspective to what has been presented: on the one hand, by analysing a different linguistic pair (French-Portuguese); on the other hand, by looking to the translation options through a doubly comparative approach: by comparing two linguistic variants (the European Portuguese and the Brazilian Portuguese), as well as two translational environments (professional and non-professional).

The main purpose of this study is to disclose whether AVT processes undertaken in the two environments differed or not in the conveyance of meaning. Can we say that factors such as technical constraints, absence of a source script and/or lack of a background in translation would inevitably condemn an amateur translator to an unsuccessful conveyance of the cultural richness of the Other to the public? And, in what regards translational situations particularly challenging, such as humour and dialects, would the versions created in non-professional contexts be necessarily less efficient, i.e., less capable of reproducing the textual intentions and/or traits presented in the source text? Ultimately, what can we infer from the relationship between the technical conditions in which the rewriting processes are undertaken and the (mis)understanding of the cultural representations presented in the official versions?

Furthermore, this research also intends to understand whether the subtitles of the film available in two linguistic variants of the same language presented or not significant differences, despite having both been apparently produced in non-professional environments. What can we disclose from the translational options taken by the two amateur translators: do they mostly represent a «culturally shared knowledge» in each of the target contexts, thus, being in accordance with the most common way of referring to the circumstances represented in the scenes among each receiving community, or do they seem to be a reflexion of the technical settings, i.e., of how the source text was received, decoded and recoded?

It is relevant to say that, just as it has been analysed by other researchers, both Portugal and Brazil present cultural dichotomies and peculiarities which could be exacerbated in a comedy —for example, in Portugal, there is a clear distinction between those living in the mainland and those from the archipelagos of Azores and Madeira in the pronunciation of words; in Brazil, very similar contrasts are noticeable as well, namely between citizens from the interior regions and those living in coastal areas. Yet, to my knowledge, there has not been so far any interest in an adaptation of Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis into any of the two contexts; rather, the film was transmitted in both countries with the French soundtrack and subtitles in the respective linguistic variant. That is why the focus of this research will be put only on the subtitles. Moreover, the choice of the Portuguese as the target language derives not only from the fact that it is my mother tongue (more precisely, the European Portuguese), but also because there is still a lack of published works about AVT into that language, particularly into the European variant. Finally, in what refers to the sources, since it is my intention to analyse the amateur translational environments available online, the subtitles in European Portuguese (presented on the tables by PT-EU) were found on the website www.legendasdivx.comand those in Brazilian Portuguese (indicated as PT-BR) on www.podnapisi.net.1 Then, the distinction with the professional environments was established by comparing those two sets of subtitles with the ones included in the official home video version of Berri and Seydoux (2014) both in French (FR) and in English (EN).

In order to facilitate the comparison among the several cases, in the content analysis, the examples will be presented in tables, with a different background colour for each of the translational environments (grey symbolizing the two professional versions and white the two non-professional ones). For the benefit of concision, I will only present some of the examples which seemed most representative of how the characters’ lines were differently conveyed. The cases will be organized and described in the following categories: (i) nomenclature, (ii) cultural expressions and linguistic register, and (iii) humour.

2. The non-professionalization of subtitling: a brief perspective

Like any other kind of translation, subtitling is undoubtedly part of contemporaneity. Still, that is particularly noticeable in the audiovisual field, due to the relevancy that television, cinema and the internet have achieved in our lives in the last decades (see Janecová 2012). If globalization has been erasing frontiers and products can circulate widely around the world, AVT has been playing a major role, especially in countries which are traditionally importers of cultural goods, such as Portugal and Brazil. From the viewers’ point of view, the access to subtitles freely available online in platforms whose users are common citizens is beneficial in the sense that they usually have no costs, are available in many languages, are easily found and downloaded, are constantly being updated and regard some of the most recent productions. From the amateur translators’ perspective, it is a work that we can associate to the idea of «home-made» captions, as Łukasz Bogucki defines it (2009: 56). Indeed, the translations are usually pursued in one’s spare time, along with and/or just like other digital, online based tasks, not being mandatory to abide by a specific schedule or editorial guideline (for a thorough acknowledgement of non-professional translation or fansubbing, see Orrego-Carmona and Lee 2017, Lee 2017, Wang 2014, O’Hagan 2009, Díaz-Cintas and Sánchez 2006). However, such translations might pose questions about the quality of what is translated. The «looseness» of the translational act might be noticeable, for instance, in a misalignment of the subtitles on the screen or in a not entirely correct or fluent translated text. According to Jorge Díaz-Cintas (2010: 346), that is a major concern: «[b]ecause of the concurrent presence of the original soundtrack and the subtitles, … subtitling find itself in a particularly vulnerable situation, open to the scrutiny of anyone with the slightest knowledge of the SL» (source language). Moreover, in non-professional contexts, there is no compulsory final scrutinous revision of the text —a process in which some media choose to invest, to assure that there are no errors or mistakes when the content is broadcasted (it is the case of RTP —see Dias Sousa 2020: 481-483). As a result, viewers might eventually disregard «clumsy» versions such as those, questioning the accuracy of what was transmitted. We also must not forget that the process of online available subtitling occurs among pairs, i.e., both the translators and the end viewers are online users. That could foment an informal atmosphere that could be reflected in the translational work. For example, the (simple) rewriting of the source content in the target language, irrespectively of the quality, could be taken as more important than the development of that sensitivity pointed out by Fernanda Porto and Helena Florêncio —a characteristic which essentially helps the translator precisely in his/her aim of conveying the meaning through the best reproduction possible of the linguistic effects and of the cultural elements presented in the source script. Finally, we need to keep in mind that the number of readers of the versions available online is unreachable and exponential. Consequently, the impact of the translated choices will always be necessarily high.

In general, subtitling is a process which presents considerable constraints to translators —smainly, change of mode, spatial and temporal limits, and coherence with the images, as indicated by Williamson and de Pedro Ricoy (2014: 164-165). Most of all, it is fundamental that the translated contents are understood as clearly and as immediately as possible by the great majority of the receivers. That implies exploring the existing linguistic features, in such a way that the source narrative can be expressed and comprehended according to what is culturally shared in the target society. Nonetheless, the translator can only achieve it if he/she decodes the audio correctly. Not as rarely as one would think, even in professional environments translators might need to rely on a listening process of the source audio. For instance, at RTP, besides the specific case of news translation (see Dias Sousa 2020: 485), it happens whenever the initial negotiation does not include an access to the script. Still, the audio is always provided by the foreign company, being a reliable source for the translational work. In turn, in non-professional environments, the audio is often recorded by the translators themselves, namely on their smartphones or in a simple voice recorder during the premières or when visualizing the film at home.2 As an example, basing on a personal recording, it is possible that the translator does not manage to hear a particular word, had someone in the room clapped, coughed, sneezed or laughed when it was pronounced. A foreign word might also be taken by its homophone: the translator might hear «life» instead of «wife», which would lead to a completely different meaning in the target version. To this may concur the translator’s non-proficiency in the source language as well, which could lead him/her to convey the message mistakenly or not entirely, omitting sentences or expressions proper to the sociocultural source context and not usually known by someone who only speaks seldom the language or has just an informal knowledge of it (for further details about errors in amateur subtitling, see Bogucki 2009: 51-55).

All in all, we may say that, in theory, there are several issues which could influence significantly what becomes known —and unknown— of the Other in a certain target context. Yet, we need to analyse such possible interference through translational examples before we may reach to any conclusions.

3. Content analysis

3.1. Nomenclature

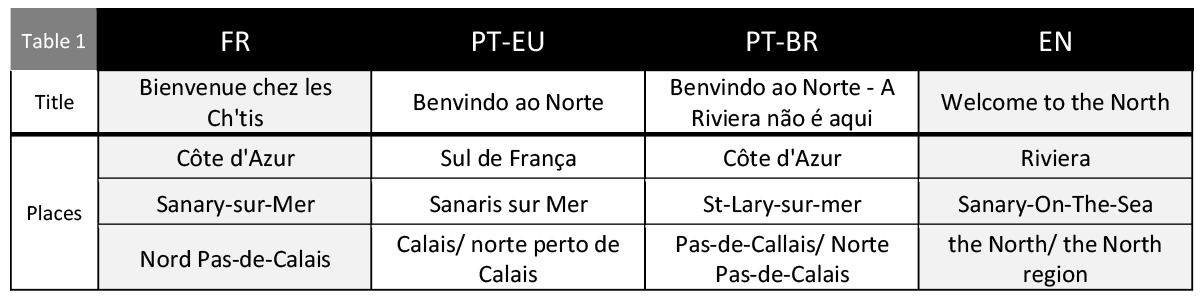

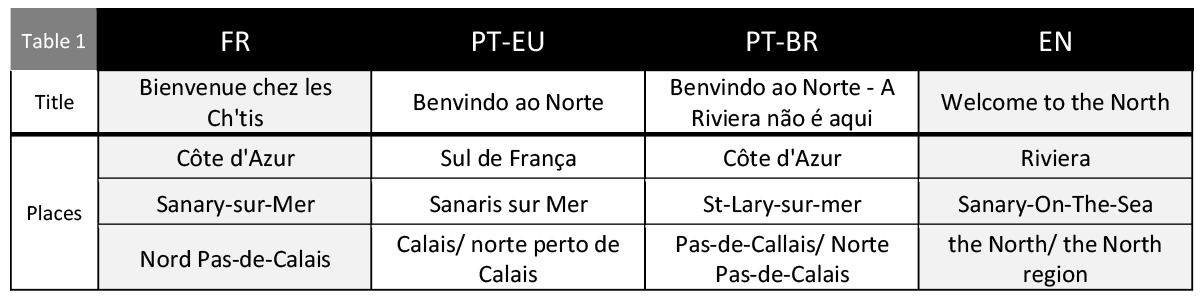

In this subsection, I considered worthy analysing the translations of the title and names of places, since I noticed that they shed some light about the impact of culture over the translators’ choices (table 1).

TABLE 1. Translations of the film’s title and names of places

Starting with the title, in all three target versions (i.e., all but the French text) the direct reference to the source community and to its dialect was lost: the two Portuguese translators, as well as the English preferred to mention the North as the place where the protagonist would be welcomed («Benvindo ao Norte»/ «Welcome to the North»), not mentioning the Ch’tis community at all, as it is indicated in the French version («chez les Ch’tis»). This means that, even though it is a central reference in the film, in all versions besides the French it was given more importance to the geographic factor rather than to the cultural and linguistic one. More precisely, instead of indicating to the public that the action would involve people who spoke the Ch’timi dialect, the translators chose to point out where it would settle —and even so, they indicated a general, vague reference: the North. Therefore, in this example, it is not perceivable an influence of the translators’ cultural background on the solutions presented, nor of the technical environment in which they produced their texts. We must pay attention, though, to the particularity of the Brazilian text: the translator added a second title, inexistent in the source version: «A Riviera não mora aqui» (something like «This is not Riviera»). This is an option that, once associated to the title, clarifies the place where the action would develop. Thus, although the central community of the film is still not mentioned, the contrast between «the North» and «the Riviera» allows viewers to anticipate that the story will take place in France, and, because of that, it is an interesting translational choice: not only does it show a precise difference compared to the other cases, but it also reveals a margin for translational autonomy, irrespectively of the target language, the target context and the mode of translation.

In what concerns the names of places, the influence of culture does seem to have played a role in the translational processes, for the public knowledge appears to have been influent in the choices of the three translators: the Brazilian did not translate «Côte d’Azur», as did his/her English counterpart («Riviera») and the European Portuguese as well («Sul de França», meaning «the South of France»). This leads me to consider that each translator chose the reference that was more familiar for the target context, thus facilitating the viewers’ understanding of the source reference. Ultimately, each of them made justice to the aimed clarity in any AVT process.

In turn, the translations of «Sanary-sur-Mer» unveil a different influence: not cultural, but mostly technical. Essentially, they show how subtitles produced in non-professional contexts might be affected by processual constraints. For instance, if the English translator pursued what we may consider a calque, according to Vinay and Darbelnet (2000: 85), when translating that name by «Sanary-On-The-Sea», what comes out from the two Portuguese versions is the process through which the translators most probably conveyed it: based on a listening process of the character’s line and not on a written version of the source text. Such a consideration arises from the following observations: the European Portuguese translator referred to «Sanaris sur Mer» —an option that presents an incorrect spelling, not being truly a borrowing (ibid.). Most of all, I believe that the translator was influenced by the intonation of the «y». Indeed, to a native European Portuguese individual, the sound «y» in a French word sounds like a plural and, in that linguistic variant, most plurals end in «-s». Therefore, it would not be surprising if a non-proficient translator would rewrite «Sanary» as «Sanaris», since it would be a familiar spelling to a native speaker. The phonetics is also perceivable in the Brazilian version, although in a different manner: the name was translated as «St-Lary-sur-mer» —a solution that seems to have derived from an understanding of the intonation of «Sanary» not as a plural, but as if the original name contained the French word «Saint» (correspondent to the abbreviation «St.») and «Lary» (i.e., «Sanary»-«Saint Lary»). Thus, as if «St. Lary» were a French saint, from whom the name of the place. It is necessary to clarify that the Brazilian linguistic variation differs from the European especially in what concerns the pronunciation of the words. This might explain why the two Portuguese translators did not decode the source text equally. They do seem to share, though, the reliance on listening, which, as claimed, is particularly common in non-professional subtitling environments.

The last example in table 1 shows both a relation with cultural factors regarding the translators and with technical aspects associated to the act of translating. In what concerns the English version, it is noticeable that the translator lost, again, the cultural richness contained in the French text, since he/she kept a preference in a broad reference instead of a specific one: while in French the character talks about «Nord Pas-de-Calais», in the English subtitle it was referred «the North» and «the North region». In both Portuguese cases, the options lead one to think, once more, in listening as the predominant form of decoding the characters’ lines —especially in the European Portuguese. For example, the French word «Nord» has as direct equivalent in the target language («norte») and was translated as such. Yet, the pronunciation of «Pas-de» seems to have been mistakenly heard as «près de», which would correspond in Portuguese to «perto de», as we read in the solution presented in that variant («norte perto de Calais»).

In general, the results obtained in this subsection lead me to consider, first, that the translations pursued in the two contexts defined as non-professional, and, among these, mainly in the European Portuguese, were perpetuated in the midst of technical constraints that were not evident in the English professional translational environment. They seem to point out how the source text was received and decoded: by listening processes. Second, that the translators relied on their personal knowledge of the foreign language and preferred solutions that would sound familiar in the target context. This ultimately benefitted the principle of clarity in AVT; thus, the perception of the source meaning by the viewers.

3.2. Cultural expressions and linguistic register

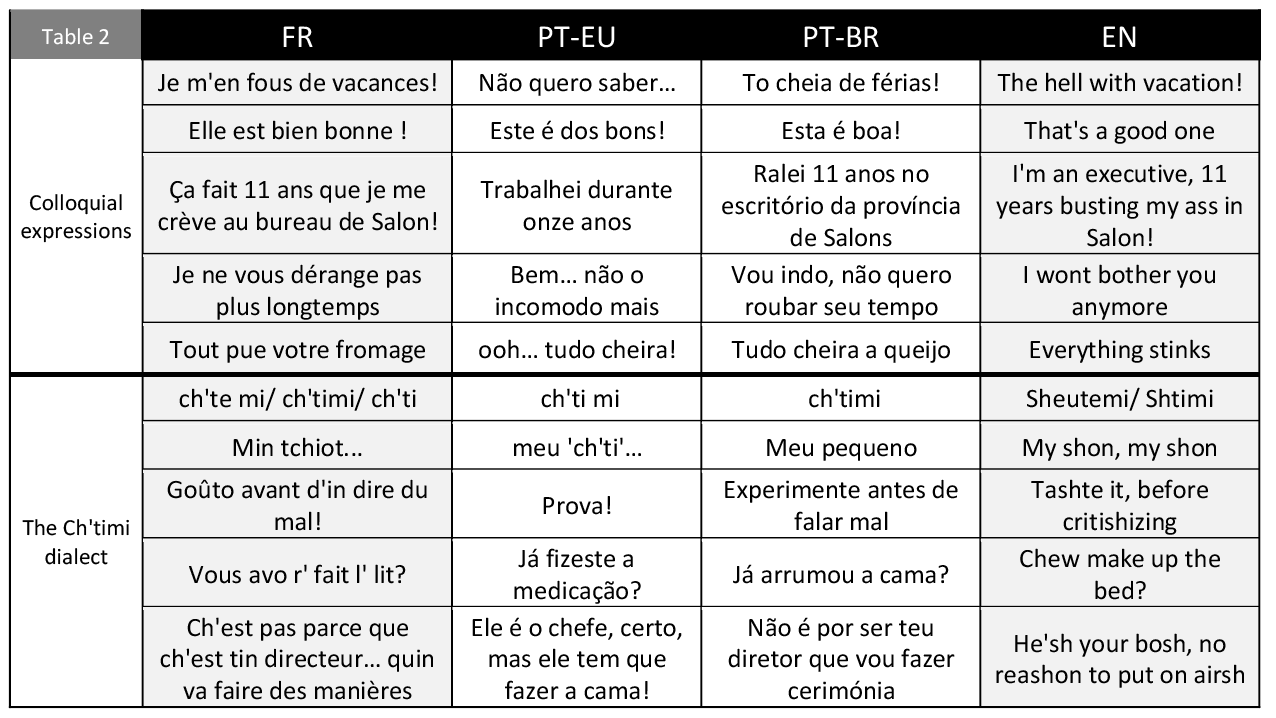

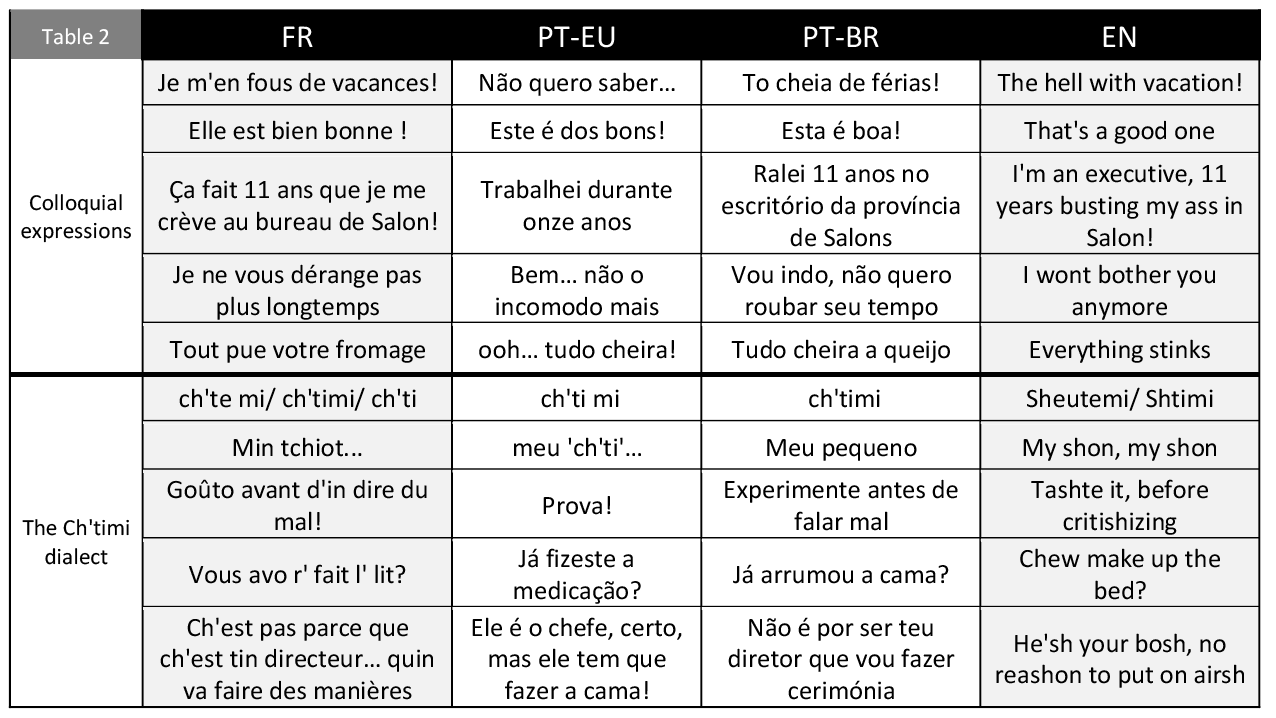

The register of the comedy is markedly colloquial: even the two characters who represent a higher socioeconomic standard —Philippe Abrams and Jean Sabrier, two directors of one of the main companies of France (La Poste)— communicate in an informal discourse, using slang. Because of that, I chose to focus on colloquial expressions (i.e., currently used by native speakers), as well as on the Ch’timi dialect. Fundamentally, I wish that this parameter will allow to shed light, on the one hand, on whether the translators relied (or not) on existing linguistic features in the target contexts, and, on the other hand, whether they managed (or not) to reproduce the textual intentions implied in the characters’ interactions. For the examples, I selected some cases which seemed more representative of the translational choices in the three target versions, compared to the French text (table 2).

In what refers to the colloquial expressions, while the English and the Brazilian translators rewrote «Je m'en fous de vacances!» by a colloquial expression existing in their languages («The hell with vacation!» and «To cheia de férias!», the latter corresponding to «I’m sick and tired of vacations»), the European Portuguese showed a lack of understanding of what was said by the characters, not even presenting a wholly constructed sentence: «Não quero saber…» (something like «I don’t care…»). Because of the suspension points in the end, we may question whether he/she really comprehended the source expression or if he/she just grasped the idea of disregard. To be complete, the subtitle needed to present, for example, «Não quero saber de férias» or, to use a colloquial expression in European Portuguese, «Nem me fales de férias!», similarly to what we read in the former two versions.

TABLE 2. Translations of colloquial expressions and of the Ch’timi dialect

Actually, misunderstanding seems to have prevailed in the European Portuguese subtitles in this category: there is another partial translation in the case of «Ça fait 11 ans que je me crève au bureau de Salon!», which was expanded by the English translator («I'm an executive, 11 years busting my ass in Salon!») and clarified by the Brazilian («Ralei 11 anos no escritório da província de Salons», meaning «da província» to «the county of»). Yet, it was only partially translated in the European Portuguese version: «Trabalhei durante onze anos» (i.e., «I worked for eleven years»). Another example of misunderstanding can be found in «Elle est bien bonne!»: it was translated, again, in both English and Brazilian by a colloquial expression («That's a good one» and «Esta é boa!», respectively); however, the European Portuguese solution «Este é dos bons!» («This is a nice guy») does not reproduce the source meaning. I am led to believe that the translator was probably influenced by what was being presented on the screen, given that it was a moment when one of the characters was talking to a colleague about the protagonist. The translator could have mistakenly attributed the argument to a different character. On the other hand, he/she might not have heard it at all. In that case, it would represent the mentioned constraint posed by listening translation processes in non-professional contexts, which ultimately may lead to incorrect translational options.

In the case of «Je ne vous dérange pas plus longtemps», we can identify very particular choices in all three target versions: in the English, again, a formal correspondence («I won’t bother you anymore», and for «formal correspondence», see Nida 2000); in the Brazilian, also again, a clarification through a reinforcement of the idea of leaving the room (by «vou indo», which in «Vou indo, não quero roubar seu tempo» means something like «I’ll leave you now, I won’t bother you anymore»); and in the European Portuguese «Bem… não o incomodo mais» (which would correspond to «Well… I won’t bother you anymore») —an option that, contrarily of what we have seen in the previous subtitles of this linguistic version, does convey the meaning and does present a formal correspondence, for «não o incomodo mais» is a colloquial expression in that linguistic variant. Nonetheless, in the whole, the subtitle denotes a stronger informality when compared to the other target versions. That seems to corroborate the idea of «looseness» in the translational work, rather more noticeable in the European Portuguese translation among all.

The last example is curious, given that only the English translator managed to deliver a colloquial expression in the target language: «Tout pue votre fromage»-«Everything stinks». Still, he/she has lost an important semantic reference of the source culture: the cheese («votre fromage»). Moreover, the cheese that was presented on the screen was typical of the region and had as one of its most prominent characteristics its particular smell. That same loss is seen in the European Portuguese version, again with a greater degree of informality: especially noticeable in the utterance «ooh» («ooh… tudo cheira!»), not having the translator presented a formal correspondence as did the English. Then, even though the Brazilian version was the only one in which the reference to the cheese was conveyed («Tudo cheira a queijo», i.e., «Everything smells like cheese»), the idea of something that stinks, presented in the French text by the verb «pue», was also lost. It could have been transmitted, had the Brazilian translator presented, for instance,«enjoa» instead (i.e., «stinks», in the place of «smells»-«cheira»).

The differences among the three versions are more evident in the translation of the Ch’timi dialect: in general, the examples presented in table 2 show that the English translator kept quite close to the French text; the Brazilian presented signs of a non-professionally carried out work; nevertheless, he/she did not significantly diverge from the source text, especially not in the conveyance of meaning, as did the European Portuguese. The closeness of the English version to the French text is mostly perceived in the reproduction of the specific sound of the dialect. That is understandable right when we compare the solutions presented for its designation: «ch'ti mi» and «ch'timi» in the Portuguese versions; and «Sheutemi/ Shtimi» in the English —an option that emphasises the «sh» sound, which is precisely the most prominent feature of the dialect. This same emphasis is noticeable in all the other examples presented in that target version: in the translation of «Min tchiot...» by «My shon, my shon». I would argue that the English translator took the liberty of reproducing the source expression by a repetition of what was said, besides introducing a slight semantic change: the meaning of the source expression is «my little boy»; yet, it seems that the translator preferred a word with which he/she could play in order to reproduce, in writing, what was said («my son»-«my shon»), then adding more emphasis by repeating it. In turn, the Portuguese translators did not show that same effort or ability: the European Portuguese translator kept the reference to the inhabitants («meu 'ch'ti'…», i.e., «my ch’ti»), while the Brazilian focused on the general meaning («Meu pequeno», i.e., «my little boy»). A similar situation can be found in the third example: «Goûto avant d'in dire du mal!» was translated with the correct meaning in English by «Tashte it, before critishizing», while we read in the European Portuguese text «Prova!» (or «taste it!»), which essentially represents a reduction and a simplification; and «Experimente antes de falar mal» (or «Taste it before criticizing») in the Brazilian, which, despite not achieving a close reproduction of the phonetics as in the English version, does reproduce the source meaning.

All in all, it seems that the European Portuguese translator was the one who had more trouble in understanding the Ch’timi lines. In truth, some of the subtitles indicate confusion: in what refers to «Vous avo r' fait l' lit?» (which would mean «Have you made the bed?»), while the «sh» sound continued to be emphasised in the English text («Chew make up the bed?») and the focus on the conveyance of the meaning, rather than on the formal correspondence, prevailed in the Brazilian subtitle («Já arrumou a cama?»), the sentence was translated in European Portuguese by «Já fizeste a medicação?» (i.e., «Have you taken your pills?»), which does not have anything to do neither with the French text nor with the action presented on the screen. In what comes to «Ch'est pas parce que ch'est tin directeur… quin va faire des manières» (which we could translate as «Although he is your boss, he must have manners»), the English translator chose to recur, this time, to a different expression and included the notion of someone who feels superior to the others: «He'sh your bosh, no reashon to put on airsh». This could be taken as a sign of difficulty in translating that particular line. Actually, also the Brazilian translator denoted some problems in comprehending it: this is noticeable when he/she turned the speech to the speaker, i.e., instead of delivering the sentence as an argument pronounced by the employee’s mother about her son’s boss (as we read in the source script), he/she presented it as a consideration of the mother about her own behaviour: «Não é por ser teu diretor que vou fazer cerimónia» («It is not because he is your boss that I will feel constrained»). The European Portuguese translator grasped the idea of a dichotomy of social status correctly, despite having introduced another semantic reference: «Ele é o chefe, certo, mas ele tem que fazer a cama!» (which is to say «No question that he is your boss, but he must make his bed!»).

In general, the few examples analysed confirm that the Ch’timi dialect must have been a major translational challenge in the several technical and cultural environments. Particularizing each of them, we may consider that, in terms of the specific linguistic and cultural references presented, the receivers of the English version were able to understand the emphasis and the exacerbation of a very specific trait of the Ch’timi dialect, such as its phonetics, at the same time that they could rely on colloquial solutions available in the target language to grasp the source meaning. Through the Brazilian subtitles, that reproduction of the Ch’timi particularities was not achieved; still, the translator did manage to correctly convey the meaning of the messages. In contrast, the European Portuguese translator evidenced to a greater extend signs of translational problems, arguably due to linguistic unproficiency and/or technical constraints. In the end, who downloaded this version of the film was prevented from acknowledging important cultural references presented in the source text. They might have felt confused at some point of the story as well, especially because of the lack of clarity and coherence between image, sound and text.

3.3. Humour

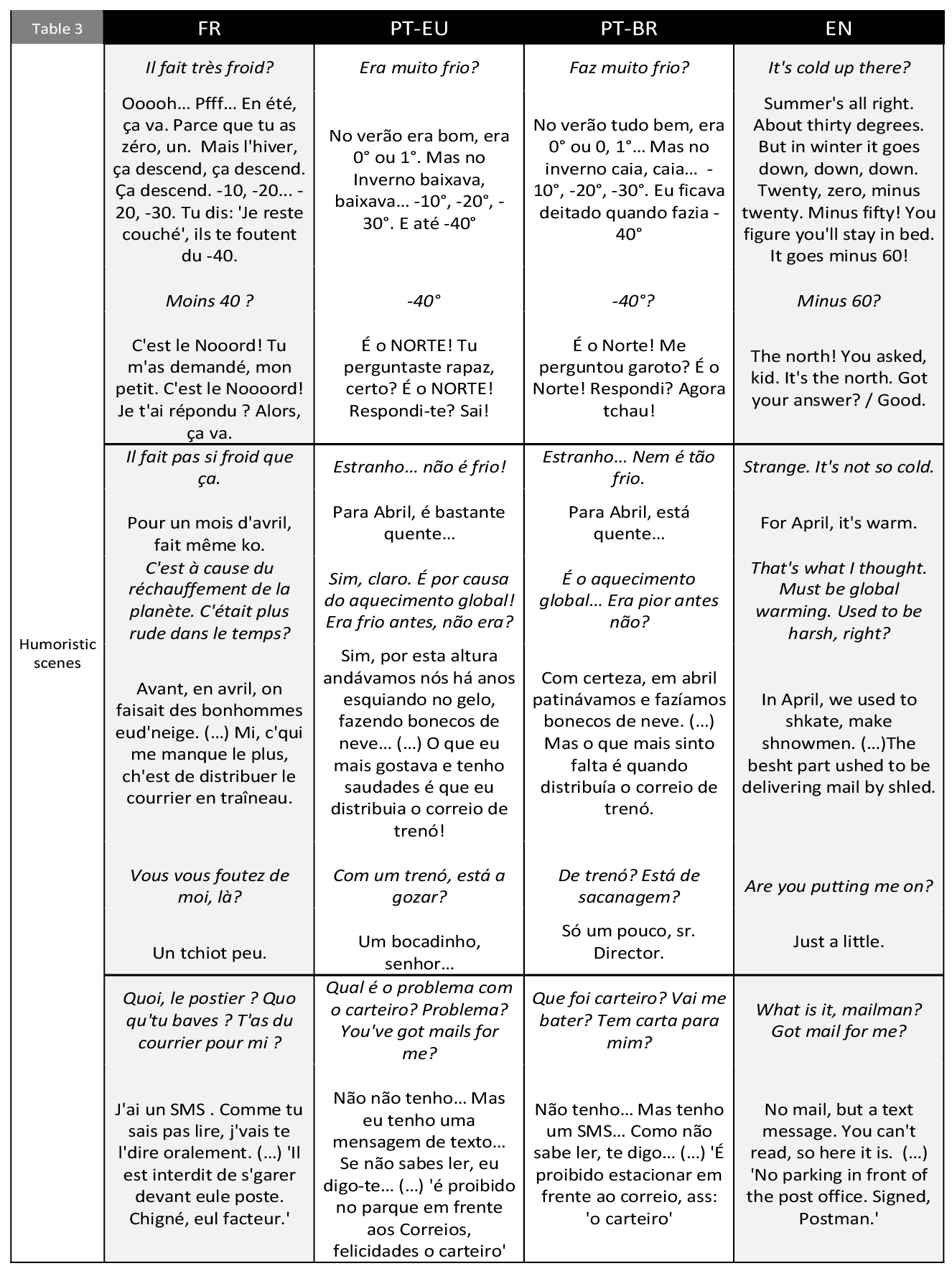

In this subsection, I want to go further and see how translators managed to convey humoristic scenes, so proper to each culture and, consequently, not straightforward translational objects (see Williamson and de Pedro Ricoy 2014: 166-167). Essentially, I hope that I can go deeper in the understanding of the cultural influence among AVT contexts which are technically different.

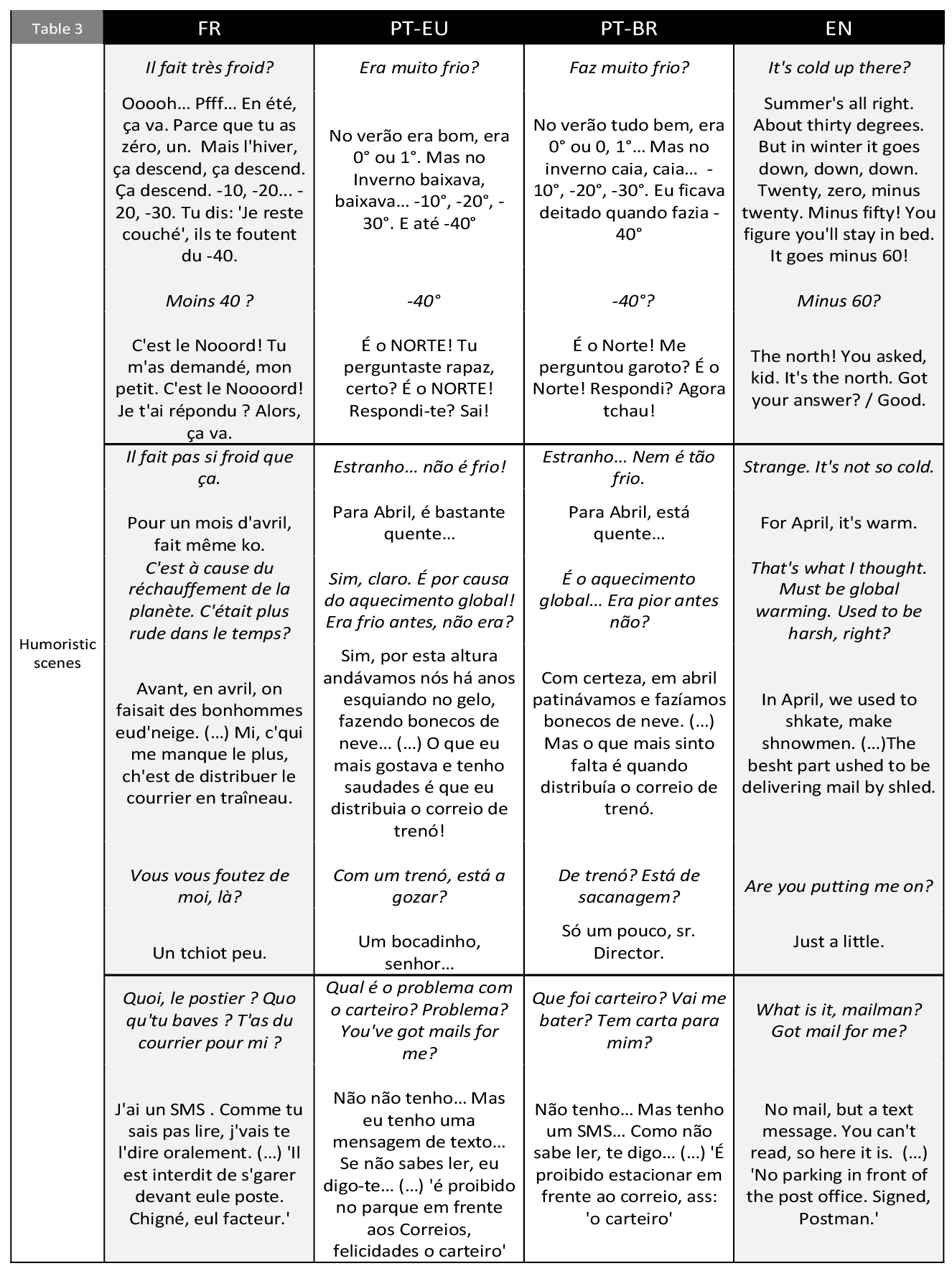

On table 3, there are three sequences of dialogues with translational choices which I thought interesting to discuss considering the research aims. In the first, not all translators managed to reproduce the meaning in its entirety, being noticeable options that, as we have seen before, do not present a tight relation either with the cultural or the technical translational contexts. For instance, none of the translators reproduced the humour presented in the utterances «Ooooh… Pfff…», perhaps because they felt that the character’s facial expression and the sound of the utterance were enough for the teasing attitude represented on the scene, or perhaps because they simply did not consider it an important element to be reproduced in the target texts. Among all, it was the Brazilian translator who kept closer to the French text in terms of meaning conveyance, even though we still identify signs that he/she probably did not had access to the source text, but only to a recorded version of the film. For instance, we see it when, while the Ch’ti character speaks slowly, giving the idea of a rough, terrible situation – when explaining that the temperature during summer used to range from zero and one degrees Celsius («En été, ça va. Parce que tu as zéro, un») –, that information was synthesised in the Brazilian version («era 0° ou 0, 1°…», i.e., «it was 0º or 0º, 1º C»), so reinforcing the tendency for clarification already identified in the analysis of this target version. In the repetition of «ça descend» in the French version («Mais l'hiver, ça descend, ça descend. Ça descend. -10, -20... -30»), we can also perceive signs of a freely pursued translation, rather than a translation based on a source script: «No verão tudo bem, era 0° ou 0, 1°… Mas no inverno caia, caia… -10°, -20°, -30°» (which we could translate as: «During the summer it was okay, we had 0º or 0, 1º C… But in winter it went down, it went down… -10°, -20°, -30°C»). Still, the meaning was conveyed, which also sustains what we have been perceiving about this target version so far. However, in what concerns the translation of the passage «Tu dis: 'Je reste couché', ils te foutent du -40», the idea of an inner dialogue was lost: «Eu ficava deitado quando fazia -40°» (i.e., «I would stay in bed when there were -40ºC»). The reproduction of that idea would demand a different translational choice: for instance, «Tu pensas: ‘Vou ficar na cama’, estão -40º» («You say: ‘I’ll stay in bed’, it’s -40ºC»). Nonetheless, compared to the European Portuguese, the Brazilian translator was by far more successful in conveying the meaning. The European Portuguese translator manifested signs of struggle in both the understanding and the reproduction of what was said, which was noticeable right at the beginning, when he/she translated «Il fait très froid?» by «Era muito frio?» («Did it used to be too cold?») —an option that contradicts the sense of the narrative at that point of the story. The protagonist is asking the other character how usually the weather is like in Lille (an idea that both the Brazilian and the English translators managed to grasp and to convey: «Faz muito frio?»-«Is it too cold?», respectively). Furthermore, the European Portuguese translator did not include the last part of the passage discussed above: «Mas no Inverno baixava, baixava… -10°, -20°, -30°. E até -40°» (meaning «But in winter it went down, it went down… -10°, -20°, -30°C. And even -40ºC»). That is to say that the whole idea of remaining in bed due to the very low temperature outside (-40ºC), which emphasises the terrible weather conditions to which the region of Nord Pas-de-Calais is generally associated to —and which was at the core of the humoristic purpose of the scene—, was completely lost. This we may attribute, once again, to a lack of understanding of the message from the translator’s part.

In the English version, we read in the subtitles the following translational solution for that passage: «Summer's all right. About thirty degrees. But in winter it goes down, down, down. Twenty, zero, minus twenty. Minus fifty! You figure you'll stay in bed. It goes minus 60!». The temperatures were converted from Celsius into Fahrenheit, which is a sign of a cultural influence in the translation process: the translator recurred to the sociocultural conventions existing in the target context. Still, if we would check on an online free converter (as Metric Conversions, available at https://www.metric-conversions.org/pt/temperatura/celsius-em-fahrenheit.htm), we would see that the numbers were readapted —arguably, to reproduce the emphasis already existing in the French text. Indeed, there was an exaggeration of the -40ºC (not -58ºF but -60ºF), which ultimately ought to have benefitted the acknowledgement of the source narrative and culture, i.e., that the protagonist was going to a very (very) unpleasant region, which is in line with the French stereotypes.

TABLE 3. Translations of humoristic scenes

It is surely not my wish to underestimate here the European Portuguese translation. To be fair, there are signs of good translation choices in that version: in the first example on table 3, it was actually the only one in which the emphasis in «Nooord» was reproduced, by means of capital letters («NORTE»). On the second example, the translator managed to deliver the meaning and I must point out that it was a case that included several expressions in the challenging Ch’timi dialect. Nevertheless, it is a fact that it is the version in which I identified more examples of difficulties in the translational work. There is even one case in which the translator opted to translate the source text in another language: that we may see on the third example, where there is an English sentence along with the European Portuguese subtitle («You've got mails for me?»). It is true that it could have resulted from an intentional addition of a teasing effect, since, in that linguistic variant, a sentence pronounced in English in a short dialogue, often involving slang, is commonly used when someone is mocking another. However, we cannot disregard the possibility of being, again, the result of what appears to be a lack of linguistic proficiency. The Ch’timi passage in the whole was not clear cut: «Quoi, le postier? Quo qu'tu baves? T'as du courrier pour mi?». Moreover, even though the translator did seem to understand the meaning of the last sentence (he/she rewrote it correctly in English), the main problem seems to have been fluency. Essentially, it lacked a sensitivity to transpose the whole line in a clear text, in which not only the meaning would be correctly conveyed, but, at the same time, the teasing attitude would be reproduced and the slang would be kept. As it was presented, the European Portuguese text is rather confusing, does not make sense in the target language and shows translational difficulties: «Qual é o problema com o carteiro? Problema? You've got mails for me?» («What’s the matter with the postman? Problem? You've got mails for me?»). A possible solution could have been «Que se passa, ó carteiro? Que ‘tás p’raí a resmungar? Tens correio p’ra mim?» («What’s the matter, postman? What are you mumbling there? Got a letter for me?»). Even so, the truth is that none of the three translated versions managed to deliver the French text as it was presented: only the Brazilian presented a solution for «Quo qu'tu baves?» («What are you mumbling there?»); however, the meaning was changed («Vai me bater?», something like «Are you going to punch me?»). In the English subtitles, the option was very similar: «What is it, mailman? Got mail for me?». Thus, I am led to think that this was another case in which nor cultural nor technical aspects were significantly influent in the translational work. Indeed, in each of the target contexts and languages, and regardless of the way the processes were conducted, both changes and problems are perceivable in the reproduction of the source message.

It is also noticeable that the English translator was not as coherent as he/she was in the previous subsection, namely in what concerns the translation of the dialect: only in the second example presented on table 3 we can see an effort to reproduce the «sh» sound of the Ch’timi («In April, we used to shkate, make shnowmen. (…) The besht part ushed to be delivering mail by shled»). We do not see it in the third example, where, in the translation of «J'ai un SMS. Comme tu sais pas lire, j'vais te l'dire oralement. (…) 'Il est interdit de s'garer devant eule poste. Chigné, eul facteur' (in the French text), we read in the English subtitles«No mail, but a text message. You can't read, so here it is. (…) 'No parking in front of the post office. Signed, Postman.'» In particular, specific words and grammatical choices such as «eule», as well as the informal register, did not present, this time, signs of the meticulous translational effort by the English translator as identified before.

In a general perspective, this subsection added, as I wished, some perspectives to what it was analysed in 3.1. and 3.2. Most of all, I noticed some circumstances which do not allow us to distinguish the translation work pursued in a professional or non-professional environment as clearly as one could have initially thought. It was still noticeable that the English translator did most probably have access to the written version of the French text, which made it possible for him/her to reproduce in his/her language particular elements of the script, namely the phonetics of the dialect. Nonetheless, at some moments, he/she also seemed to disregard such an effort for the sake of other translational concerns, particularly meaning. This ought to have been why he/she has preferred not to translate some lines or not to look for a formal correspondence in the target language, focusing on the clear and correct transfer of the characters’ lines instead, whenever the content was translational more challenging. Then, comparing the two Portuguese versions, in the rewriting of the humoristic scenes we continued to identify clear differences, with the Brazilian translator having been more successful in delivering the meaning of the messages – it continued to be the focus of his/her work – and the European Portuguese presenting, again, signs of a less-proficient work. The solutions presented by each in the third example show it quite clearly: while the latter rewrote «Não não tenho… Mas eu tenho uma mensagem de texto… Se não sabes ler, eu digo-te (…): 'é proibido no parque em frente aos Correios, felicidades o carteiro'» («No, I don’t have it… But I have a text message… If you cannot read, I tell you… ‘it is forbidden in the park before the post office, regards the postman»), the former, besides having been grammatically correct, reproduced both the meaning and the humour in the dialogue by presenting the French text as «Não tenho… Mas tenho um SMS… Como não sabe ler, te digo (…): 'É proibido estacionar em frente ao correio, ass: 'o carteiro'» («No, I don’t… But I have an SMS… Since you cannot read, I’ll read it to you…: ‘It is forbidden to park before the post office, signed: ‘the postman’»). We see that «to park» was mislead in the European Portuguese subtitle by «in the park». Altogether, the options presented in the European Portuguese negatively impact the correct and clear understanding of what was said. Thus, despite the non-professionalization of both versions, the subtitling processes were very different. They seem to have been influenced by more than just technical factors, not being possible to look in equal terms to each of them neither in terms of quality and efficiency.

4. Final remarks

In 2010, Jorge Díaz-Cintas (2010: 347-348) claimed that «digitisation and the availability of free subtitling software on the net have made possible the rise and consolidation of translation practices» developed in amateur environments, which were presenting «an incidental effect on how formal conventions» about AVT were applied. In his view, «[o]nly time [would] tell whether these conventions put forward by the so-called ‘collective intelligence’… are just a mere fleeting fashion or whether they are the prototype for future subtitling» (ibid.: 348). Eleven years later, and according only to what this research allowed me to understand, I believe that the author did have reasons to suspect that the technological evolution and the evermore frequent participation of common citizens in AVT would conduct to a modification of the existing panorama. This research led me to conclude that the easiness surrounding AVT undertaken and available on the internet must make us ponder about the definitions of both translation and translators used so far, for we cannot establish any clear a priori distinction between professional and non-professional environments based only in their most typical characteristics. Neither the probable access of a professional translator to the source script, nor the absence of such a resource from a non-professional showed to be determinant in the end products. Indeed, what this research allowed me to perceive was fundamentally that:

- A translator working on his own, non-professionally, will not necessarily have more translational difficulties than one who has accessed the source text. That was noticed in some English subtitles, in which, despite the closeness to the French source script and the fact that it was a version consulted in the official DVD of the film, there were signs of trouble, especially in some of the most complex lines written in the Ch’timi dialect and associated to humour;

- We cannot presuppose that a non-professional translator would necessarily create a target version poorly efficient in the conveyance of meaning. The best example was the Brazilian version, available online and with indicators of a freely conducted, home-based, non-professional translational process, but in which I identified a consistently correct transfer of the dialogues;

- We cannot put in equal terms two non-professional translated versions of a same text, even if created in the same (broad) language. On the contrary, they might present several disparities, which seem to depend on the translators’ linguistic skills in both the source and the target languages, as well as in a more or less developed sensitivity. In this research, it was rather clear that the European Portuguese translator was the less efficient in transferring meaning, not having been perceivable many signs of closeness with the also non-professional Brazilian translator. This is to say that the technical environment alone cannot be taken as the main influence in amateur AVT processes;

- We also cannot assume the cultural factor as an autonomous variable in the process either. In my opinion, it was the context in the whole —i.e., the translators’ capability of correctly decoding the source text, their ability to rewrite it fluently in the target context, and their facility (and/or willingness) to reproduce important features of the source community, such as the Ch’tis phonetics— which ultimately characterized the target versions.

I hope that, by presenting this study, I managed to not only contribute to the work that has been presented about Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis in Translation Studies, but also to foment a reflection over the processes of rewriting the same content in different translational environments and linguistic variants. Based on the analysis described in this article, I believe that it is possible to confirm that translation plays an important role in the very possibility of acknowledging a foreign reality. That is unquestionably supported and benefitted from the new facilities brought by the internet to the AVT field. However, we need to keep in mind that, at the same time that not all non-professional translations available online will present a negative impact of the constraints implied in the work, in some cases, the translators’ misunderstanding of the source content may definitely prevent viewers from correctly perceiving the Other. Ultimately, I would argue that, when considering the non-professional AVT environment, it is necessary to sustain a broader perspective of the translational process and regard every translated work as the product of a whole context, in which different agents, texts and environments encounter. Therefore, no pre-established consideration should be assumed and every result would surely be worthy in the perpetuation of the path that has been followed in the study of AVT, in general.

Bibliography

Berri, C. and J. Seydoux [2014 (2008)]: Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis [DVD]. Paris, Pathé Films.

Bogucki, Ł. (2009): «Amateur subtitling on the internet», in J. Díaz-Cintas and G. Anderman (eds.): Audiovisual translation: language transfer on screen. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 49-57.

Costa, A. (2016): Personal interview. Lisboa, RTP, December 12.

Dias Sousa, M. (2020): «Por detrás do ecrã: a (história da) tradução na RTP contada por quem sabe» [«Behind the screen: the story of translation on RTP told by who knows it well»], in Gil, I., Lopes, A. and Moniz, M. L. (eds.): Era uma vez a Tradução… [Once Upon a Time There Was Translation…]. Lisboa, Universidade Católica Editora, 467-488.

Díaz-Cintas, J. (2010): «Subtitling», in Gambier, Y. and van Doorslaer, L. (eds.): Handbook of translation studies. Vol. 1. Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 344-349.

Díaz-Cintas, J. and P. M. Sánchez (2006): «Fansubs: audiovisual translation in an amateur environment», The Journal of Specialised Translation, 6, 37-52.

Ellender, C. (2016): «‘On dirait même pas du français’: subtitling amusing instances of linguistic and cultural otherness in Dany Boon’s Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis and rien à declarer», Skase Journal of Translation and Interpretation, 9 (1), 2-25.

Garcia-Pinos, E. (2017): «Humor and linguistic variation in Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis: the Catalan and Spanish case», MonTI, 9, 149-180.

Gambier, Y. (2018): «Translation studies, audiovisual translation and reception», in Di Giovanni, E. and Gambier, Y. (eds.): Reception studies and audiovisual translation. Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 43-66.

Gentile, P. and L. van Doorslaer (2019): «Translating the North–South imagological feature in a movie: Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis and its Italian versions», Perspectives, 27 (6), 797-814, doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2019.1596137.

Lee, Y. (2017): «Non-professional subtitling», in Lee, Y.: The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Translation, 566–79. London/ New York: Routledge, http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781315675725-34

Lefevere, A. (1992): Translation, rewriting, and the manipulation of literary fame. London, Routledge.

Janecová, E. (2012): «Teaching audiovisual translation: theory and practice in the twenty-first century», Çankaya University Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 9 (1), 17–29.

Nida, E. (2000, 1964): «Principles of correspondence», in Venuti, L. (ed.): The translation studies reader. London, Routledge, 126-140.

Nobre, N. M. (2013): «A legendagem no Brasil: interferências linguísticas e culturais nas escolhas tradutórias e o uso de legendas em aulas de língua estrangeira» [«Subtitling in Brazil: linguistic and cultural interferences in translational choices and the use of subtitles when teaching foreign languages»], Revista do Curso de Letras: Artigos de Estudo de Linguagem, 2 (1), http://periodicos.unifap.br/index.php/letras.

O’Hagan, M. (2009): «Evolution of user-generated translation: fansubs, translation hacking and crowdsourcing», The Journal of Internationalization and Localization, 1, 94-121, doi:10.1075/jial.1.04hag.

Orrego-Carmona, D. and Y. Lee (eds.) (2017): Non-professional subtitling. London, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Porto, F. and H. Florêncio (2016): Personal interview. Lisboa, RTP, December 12.

Rȩbkowska, A. (2014): «Bonchoir, biloute! L’hétérolinguisme comme source d’humour dans Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis et dans sa version polonaise», CEJSH: The Central European Journal for Social Sciences and Humanities, 23, 169-188, doi: 10.12797/MOaP.20.2014.23.12.

Rȩbkowska, A. (2011): «Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis: image stéréotypée des habitants du Nord-Pas-de-Calais dans la traduction polonaise de Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis de Dany Boon», Traduire, 225, 49-65.

Reutner, U. (2013): «El dialecto como reto de doblaje: opciones y obstáculos de la traslación de Bienvenue chez les Ch‘tis» [«Dialect as a challenge for dubbing: options and obstacles in the translation of Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis»], Trans, 17, 151-165.

Sequeira, M. (2019): Personal interview. Lisboa, RTP, May 15.

Sustelo, T. (2016): Personal interview. Lisboa, RTP, November 19.

Vinay, J. P. and J. Darbelnet [2000 (1958)]: «A methodology for translation», in Venuti, L. (ed.): The translation studies reader. London, Routledge, 84-93.

Wang, F. (2014): «Similarities and differences between fansub translation and traditional paper-based translation», Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4 (9), 1904-1911.

Williamson, L. and R. P. Ricoy (2014): «The translation of wordplay in interlingual subtitling: a study of Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis and its English subtitles», Babel 60 (2), 164–192, doi:10.1075/babel.60.2.03wil.

1 Both platforms were consulted in November 2014, when I started this study.

2 For reception studies on AVT, see Gambier 2018.