Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation Vol. 11. No. 2. December 2025 - pp. 103-121 - ISSN: 2444-2925

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.112.2025.21652

Preschool Teachers’ Intentions to Use Digital Storytelling in Early Childhood Education: An Analysis through the UTAUT2 Model

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.1. INTRODUCTION

The rapid advancement of digital technology has significantly transformed the landscape of education, including early childhood learning environments (Al-khresheh et al., 2024; Bethencourt-Aguilar et al., 2021; López-Marí et al., 2021; Şakir, 2024). One of the emerging pedagogical tools in this context is digital storytelling (DST), which integrates multimedia elements such as text, images, audio, and animation to create engaging and interactive learning experiences (Chang & Chu, 2022). DST supports children’s cognitive, language, and socio-emotional development by fostering creativity, engagement, and a deeper understanding of concepts (Addone et al., 2021). In early childhood education, where storytelling plays a crucial role in learning and development, the integration of DST can enhance traditional teaching methods and provide children with a more dynamic and interactive learning experience (Jalongo, 2021).

Despite these potential benefits, the adoption of DST in preschool education remains limited. Research suggests that teachers’ acceptance and willingness to use technology are key factors in the successful integration of digital tools in classrooms (Ateş & Kölemen, 2025). However, while numerous studies have examined teachers’ technology adoption in general, there is a lack of research specifically focusing on preschool teachers’ intentions to use DST. Moreover, existing studies on DST in education primarily focus on its impact on students’ learning outcomes rather than the factors influencing teachers’ adoption of this tool (Yang et al., 2022). This gap in research suggests that more attention is needed to understand the specific challenges, motivations, and facilitating conditions that influence preschool teachers’ use of DST in their teaching practices.

To address this gap, the present study employs the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2) framework (Venkatesh et al., 2012) to investigate preschool teachers’ intentions to integrate DST into their teaching practices. UTAUT2 is a comprehensive model that explains technology acceptance by examining factors including performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit. While UTAUT2 has been widely applied in higher education and workplace settings, its application in early childhood education—particularly in relation to DST—remains underexplored. By utilizing this model, the study aims to provide a deeper understanding of the factors that encourage or hinder preschool teachers from adopting DST in their classrooms.

This study is particularly significant as it contributes to both theoretical and practical aspects of early childhood education. From a theoretical perspective, it expands the application of UTAUT2 in the context of preschool education, offering empirical evidence on how teachers perceive and adopt DST. By identifying the key factors that influence technology acceptance among preschool teachers, this study provides a nuanced understanding of how DST can be successfully integrated into early childhood curricula. From a practical perspective, the findings can inform teacher training programs, helping educators develop the necessary skills and confidence to use DST effectively. The study also provides valuable insights for policymakers and curriculum developers to design strategies that promote DST as a meaningful pedagogical tool in preschool settings.

Given the increasing emphasis on technology integration in early childhood education, it is essential to explore how teachers perceive DST and what factors influence their willingness to use it. Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following research question: What factors influence preschool teachers’ intention to use DST in their classrooms based on the UTAUT2 model?

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Digital Storytelling in Early Childhood Education

Digital storytelling in early childhood education represents an innovative pedagogical approach that combines traditional narrative techniques with digital media tools to create engaging and meaningful learning experiences for young children (Catalano & Catalano, 2022; Hoa & Minh, 2023). By integrating multimedia elements such as images, text, audio, video, and animation, digital storytelling enriches the narrative experience while also supporting the development of digital literacy skills from an early age (Hartsell, 2017). This method allows educators to tailor stories to children’s interests and cultural contexts, thereby creating a more personalized and relevant learning environment (Catalano & Catalano, 2022; Hoa & Minh, 2023).

Empirical research indicates that digital storytelling can significantly enhance both cognitive and socio-emotional learning. For example, studies conducted in Vietnam have shown that early childhood educators perceive digital storytelling as a means to bridge real-life experiences with curriculum content, fostering active engagement and critical thinking (Hoa & Minh, 2023; Purnama, 2021). Similarly, research from Indonesia highlights that digital storytelling enhances children’s storytelling competence, imagination, and early literacy development (Purnama, 2021; Purnama et al., 2022). Rahiem (2021), in an in-depth case study of a storytelling–art–science club in Indonesia, showed that teachers use DST because it makes storytelling more entertaining, captivating, communicative, and theatrical. Observations with over 70 children revealed that simple digital technologies—combined with traditional storytelling—engaged children more deeply and promoted active participation. Rahiem’s findings underscore the necessity of improving teachers’ technological competencies, enhancing school ICT infrastructure, and updating curricula to integrate DST effectively. Similarly, Catalano and Catalano (2022) found that digital storytelling is increasingly being adopted as a means to promote child-centred pedagogy in kindergartens. Their mixed-methods study involving 160 educators revealed that DST allows teachers to select and design digital stories aligned with children’s unique experiences and interests. The approach fosters opportunities for children to make sense of their own lives and for teachers to better understand their students, thereby enhancing empathy, emotional intelligence, and classroom relationships. The adaptability and novelty of DST also make it highly impactful in both online and onsite learning contexts. From a developmental perspective, the model of “early childhood Imagineering” developed by Jitsupa et al. (2022) provides a structured framework for integrating DST in ECE in Thailand. Their research synthesized and evaluated a four-stage model: Leading to Learn (imagination), Active Learning (design and development), Opinion Sharing (presentation), and Reflective Thinking (improvement and evaluation). The implementation of this model, which incorporates stop-motion animation and collaborative storytelling, was strongly endorsed by educational experts. Their results highlight that DST, when embedded within systematic, creative processes, promotes imagination, self-expression, and reflective thinking—crucial competencies for holistic early childhood development. Direct classroom evidence of DST’s practical benefits has also been documented by Yuksel-Arslan et al. (2016), who employed a phenomenological approach to explore Turkish kindergarten teachers’ experiences with DST after specialized workshops. The study revealed that teachers effectively used DST to enrich learning activities, improve student engagement, and scaffold complex concepts through digital narrative formats. The teachers reported several successes—including heightened motivation, improved collaboration, and enhanced creativity among children—but also highlighted challenges such as technical difficulties, time constraints, and the need for ongoing professional development. These findings suggest that the integration of digital storytelling not only supports academic domains such as reading and language acquisition but also nurtures creativity and socio-cultural awareness (Adara, 2020; Purnama et al., 2022).

An additional benefit of digital storytelling is its ability to promote child-centered learning environments. The adaptability of digital stories enables educators to design narratives that reflect children’s individual experiences, interests, and cultural backgrounds, thus fostering empathy, emotional intelligence, and interpersonal skills (Catalano & Catalano, 2022; Maranatha et al., 2024). In this context, digital storytelling serves as an engaging pedagogical tool that draws on students’ prior knowledge and lived experiences, enabling deeper connections between instructional content and personal learning journeys (Kisno et al., 2022; Maranatha et al., 2024). Furthermore, the interactive nature of digital storytelling encourages active participation and collaboration, which are essential for developing higher-order thinking skills and building a sense of classroom community (Purnama et al., 2022; Sunar et al., 2022).

Digital storytelling also extends classroom learning beyond traditional boundaries by incorporating alternative modes of communication and expression. Educators can utilize digital media to develop stories that are accessible, culturally responsive, and aligned with educational goals, such as enhancing literacy and fostering digital competence (Adara, 2020; Sabari & Hashim, 2023). As children engage with these multimodal narratives, they are exposed to new vocabulary and language structures, while also learning to appreciate diverse storytelling forms and techniques (Losi et al., 2022; Purnama, 2021). Such engagement plays a critical role in laying the foundation for both linguistic and digital literacy development (Hartsell, 2017; Hoa & Minh, 2023).

In summary, digital storytelling in early childhood education is a multifaceted instructional tool that enhances learning by integrating technology with narrative practices. It facilitates content delivery that is connected to children’s lived experiences, supports culturally responsive and child-centered pedagogy, and strengthens language and literacy skills. As an emerging field in early childhood education, digital storytelling presents promising opportunities for fostering creativity, digital fluency, and holistic development among young learners (Hoa & Minh, 2023; Purnama, 2021; Purnama et al., 2022).

2.2. Hypothesis Development

The adoption of digital storytelling (DST) in early childhood education is shaped by psychological, social, and institutional factors. Grounded in the UTAUT2 model (Venkatesh et al., 2012), this study explores seven constructs—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit—as predictors of preschool teachers’ intention to adopt DST (Tang et al., 2025).

Performance expectancy refers to teachers’ beliefs about DST’s effectiveness in enhancing instructional quality and learning outcomes. Prior studies show that tools perceived as beneficial for engagement, comprehension, and skill development are more readily adopted (Hu et al., 2025). DST’s multimodal features support creativity, language development, and digital literacy, increasing its perceived instructional value. Thus, it is hypothesized that performance expectancy positively influences intention to use DST. Effort expectancy captures the perceived ease of learning and applying DST. Teachers are more likely to adopt tools that are intuitive and require minimal training (Ateş & Gündüzalp, 2025). Given preschool teachers’ multifaceted responsibilities, user-friendly interfaces and integration with existing practices can reduce cognitive load and increase adoption likelihood. Social influence reflects the extent to which teachers feel encouraged by peers, administrators, and parents to use DST (Şimşek & Ateş, 2022). In collaborative preschool environments, perceived professional or policy-level support can strengthen adoption intentions. Facilitating conditions, such as access to technology, institutional backing, and training, play a critical role in technology use (Sungur-Gül & Ateş, 2021). Teachers are more likely to adopt DST when they have the tools and support needed to use it confidently. Hedonic motivation refers to the enjoyment teachers derive from using DST. Studies indicate that when digital tools are fun and creatively engaging, educators are more motivated to use them (Berkovich & Hassan, 2024). DST’s narrative and multimedia elements can make the teaching process more personally rewarding. Price value involves the perceived cost-effectiveness of DST, especially in resource-limited settings. Teachers are more inclined to adopt technologies they view as affordable and pedagogically beneficial (Duer & Jenkins, 2023). Open-access platforms and low-cost tools can enhance DST’s appeal. Habit captures the influence of prior experience with digital tools. Teachers with a background in multimedia instruction or frequent use of technology are more likely to integrate DST routinely (Venkatesh et al., 2012; Şimşek & Ateş, 2022). Familiarity reduces resistance and supports long-term engagement.

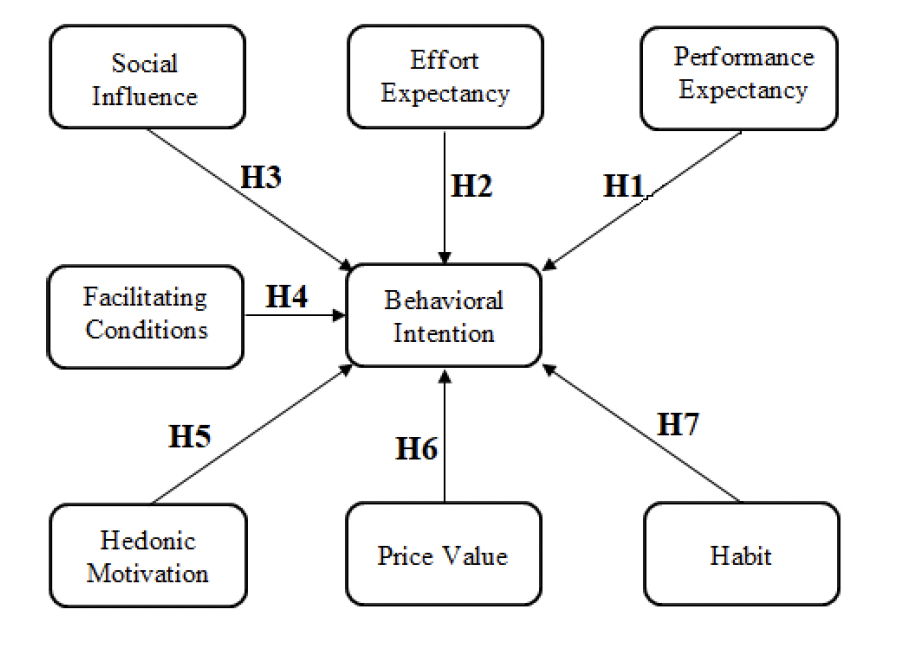

Based on the UTAUT2 framework and its application to preschool teachers’ adoption of DST, the following hypotheses are proposed. The relationships among the constructs are depicted in Figure 1:

H1: Performance expectancy positively influences preschool teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in their classrooms.

H2: Effort expectancy positively influences preschool teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in their classrooms.

H3: Social influence positively influences preschool teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in their classrooms.

H4: Facilitating conditions positively influence preschool teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in their classrooms.

H5: Hedonic motivation positively influences preschool teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in their classrooms.

H6: Price value positively influences preschool teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in their classrooms.

H7: Habit positively influences preschool teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in their classrooms.

FIGURE 1. UTAUT2 Model for Digital Storytelling Adoption.

This figure illustrates the theoretical framework and hypothesized relationships among the seven UTAUT2 constructs and teachers’ intention to use digital storytelling in early childhood education.

3. MATERIAL AND METHOD

3.1. Data Collection Process

To prepare participants for the integration of DST into early childhood education, we first provided an overview highlighting its pedagogical benefits, such as fostering creativity, language development, and digital literacy in preschool settings. Teachers were introduced to the purpose, features, and educational relevance of DST to ensure a clear understanding of its potential.

We then offered a technical introduction to DST tools, including descriptions of software platforms, multimedia integration options, and hardware requirements. Step-by-step user guidelines were developed, supported by visuals and video tutorials, to accommodate varying levels of technological proficiency among teachers.

Hands-on workshops and training sessions were organized to guide teachers through key DST processes, such as storyboarding, multimedia editing, and voice narration. Participants had the opportunity to create digital stories, troubleshoot issues, and explore classroom applications in collaborative settings.

To support ongoing adoption, a help desk, online forums, and regular Q&A sessions were established. Teachers were encouraged to share experiences and seek assistance, fostering a supportive learning community. Feedback was collected through surveys and informal reflections to refine training content and support systems.

Updates on DST technologies were periodically shared, and case studies showcasing successful classroom implementations were included to inspire and motivate participants. This structured approach—combining technical knowledge, practical training, and continuous support—aimed to ensure confident, sustainable integration of DST in preschool education.

3.2. Participants

The participants of this study consisted of in-service preschool teachers actively employed in public and private early childhood education institutions across various metropolitan cities in Turkey. Data collection was conducted through a self-administered questionnaire, distributed at the beginning of the spring semester (January to May 2024). We used convenience sampling to recruit teachers with diverse levels of technological proficiency and teaching experience, ensuring a representative sample for analyzing DST adoption in preschool education.

Before participating, all teachers received informed consent forms outlining the study’s objectives, the voluntary nature of participation, and the confidentiality of their responses. Ethical guidelines were strictly followed to ensure participant autonomy and data protection. The teachers were given adequate time to review the information before proceeding with the survey.

A total of 600 questionnaires were distributed, and 550 completed responses were collected, resulting in a 91.6% response rate. After screening for incomplete or inconsistent answers, all 550 responses were deemed valid for inclusion in the final analysis. According to Kline (2011), a minimum of 10 cases per survey item is necessary for statistical reliability. Given that the questionnaire contained 35 items, a minimum of 350 responses was required; therefore, our sample of 550 participants exceeded this threshold, ensuring robust and reliable data analysis.

The demographic distribution of the participants reflected a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds. Among the teachers, 73% were female and 27% were male, which aligns with the general gender distribution in early childhood education. The majority of participants were between the ages of 30 and 45 (67%), with 64% being married. Regarding educational qualifications, 29% of teachers held postgraduate degrees, indicating a high level of professional development.

In terms of technology experience and DST familiarity, 18% of teachers reported having previously integrated DST into their classroom activities, while an additional 52% expressed interest in using DST for storytelling and instructional purposes. Teachers with prior DST experience reported using it mainly for language development, creative expression, and student engagement, while those new to DST cited the need for additional training and institutional support before full implementation. The remaining 30% of teachers were unfamiliar with DST but were open to exploring its potential benefits in early childhood education.

3.3. Measures

The data collection instruments used in this study were developed through a systematic and rigorous process, beginning with a comprehensive review of literature on UTAUT2 and its application in educational technology adoption (Ateş & Polat, 2025; Venkatesh et al., 2012). The initial scale items were designed based on UTAUT2 constructs, including performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit, ensuring that each construct aligned with the theoretical framework guiding this study. To validate the relevance and clarity of these items, a panel of four experts in early childhood education, educational technology, and psychology evaluated their face and content validity, following the recommendations of Gravetter and Forzano (2012). This evaluation ensured that the items were clearly worded, culturally appropriate, and accurately measured the constructs under investigation.

Following expert validation, a pilot study was conducted with 255 in-service preschool teachers to assess the reliability and validity of the instrument. This preliminary phase allowed for the identification of potential ambiguities, redundancies, and response biases in the measurement scales, ensuring that the final version accurately captured preschool teachers’ perceptions and intentions regarding DST adoption. Considering the Turkish educational context, the questionnaire was translated from English to Turkish using a blind translation-back-translation method, as recommended by Esfandiar et al. (2020). This process was crucial in maintaining semantic and conceptual equivalence, minimizing language-related distortions that could affect the validity of responses.

The final survey instrument was structured around the UTAUT2 model to systematically assess the factors influencing preschool teachers’ adoption of DST. The instrument included eight constructs, each measured with three or four items, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of their influence on teachers’ behavioral intentions.

Performance Expectancy (PE) was measured using three items that assessed teachers’ beliefs regarding the extent to which DST would enhance instructional quality and learning outcomes. Effort Expectancy (EE) included three items evaluating the perceived ease of learning and applying DST in preschool education. Social Influence (SI) was measured through three items capturing the perceived encouragement and expectations from colleagues, school administrators, and other influential figures regarding the use of DST. Facilitating Conditions (FC) consisted of four items assessing access to technological infrastructure, institutional support, training opportunities, and the compatibility of DST with existing teaching tools. Hedonic Motivation (HM) was captured using three items that measured the degree of enjoyment and intrinsic satisfaction teachers derived from using DST. Price Value (PV) was assessed through three items focusing on teachers’ evaluations of the cost-effectiveness and perceived benefits of using DST. Habit (HT) was measured with three items reflecting the frequency and automaticity of technology use in teaching, including the likelihood of DST becoming a routine part of instructional practices. Finally, Behavioral Intention (INT) to use DST was measured using three items that examined teachers’ future intentions, plans, and commitment to integrating DST into their classroom practices.

As seen in Table 1, all 30 items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

TABLE 1. Digital Storytelling Adoption Scale: Constructs and Item-Level Metrics

| Construct | Item Statement | Factor Loading | Mean | SD | AVE | CR | α |

| Performance Expectancy (PE) | Using digital storytelling in my classroom will improve student engagement and learning outcomes. | 0.84 | 5.21 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

| DST helps me teach more effectively. | 0.81 | 5.18 | 0.81 | 0.85 | |||

| DST enhances my productivity in planning and delivering lessons. | 0.85 | 5.09 | 0.85 | 0.85 | |||

| Effort Expectancy (EE) | Learning to use DST in preschool education is easy for me. | 0.82 | 4.88 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.84 |

| The interface of DST tools is user-friendly. | 0.83 | 4.92 | 0.90 | 0.83 | |||

| I can quickly learn how to create digital stories. | 0.85 | 4.85 | 0.86 | 0.85 | |||

| Social Influence (SI) | My colleagues encourage me to use DST in my teaching. | 0.78 | 4.75 | 0.91 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| My school administrators support the use of DST. | 0.81 | 4.80 | 0.87 | 0.81 | |||

| Other teachers whose opinions I value think I should use DST. | 0.80 | 4.85 | 0.85 | 0.80 | |||

| Facilitating Conditions (FC) | My school provides the necessary technology for DST. | 0.84 | 4.61 | 0.94 | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| I have sufficient training to use DST effectively. | 0.81 | 4.55 | 0.89 | 0.81 | |||

| I can receive support when facing problems with DST. | 0.83 | 4.66 | 0.91 | 0.83 | |||

| DST is compatible with the other teaching tools I use. | 0.80 | 4.58 | 0.88 | 0.80 | |||

| Hedonic Motivation (HM) | Using DST in class is enjoyable for me. | 0.85 | 5.02 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| I find DST fun and engaging to work with. | 0.83 | 5.08 | 0.89 | 0.83 | |||

| Creating digital stories makes teaching more enjoyable. | 0.82 | 4.95 | 0.87 | 0.82 | |||

| Price Value (PV) | The educational benefits of DST outweigh its cost. | 0.79 | 4.42 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| DST provides good value for the time and effort invested. | 0.81 | 4.47 | 1.00 | 0.81 | |||

| Habit (HT) | Using digital tools like DST is part of my regular teaching practices. | 0.83 | 4.85 | 0.94 | 0.68 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

| I often use similar technologies, so DST feels familiar. | 0.82 | 4.78 | 0.92 | 0.82 | |||

| I expect to routinely use DST once I begin. | 0.80 | 4.75 | 0.91 | 0.80 | |||

| Intention to Use DST (INT) | I am committed to using DST in future classroom activities. | 0.87 | 5.18 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.88 |

| I will try to integrate DST into my teaching as much as possible. | 0.85 | 5.10 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

3.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis for this study was performed using SPSS version 21 for descriptive statistics and reliability analysis and AMOS version 20 for structural equation modeling (SEM), ensuring a rigorous statistical evaluation of the proposed model based on the UTAUT2. The analytical process followed a multi-step approach to examine the measurement structure, reliability, validity, and structural relationships among the key factors influencing preschool teachers’ adoption of DST in early childhood education.

Initially, descriptive statistics were computed to summarize the means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions of the survey responses. This step provided an overview of general trends regarding teachers’ perceptions, prior experiences, and intentions related to DST. Skewness and kurtosis values were examined to assess the normality of the data, ensuring that parametric statistical tests could be appropriately applied.

To validate the measurement model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS 20. This analysis assessed the factor structure, reliability, and validity of the constructs in the study. Internal consistency was evaluated by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each construct, ensuring that all values met or exceeded the acceptable threshold of 0.70. Additionally, composite reliability (CR) values were calculated to verify the internal consistency of each latent variable.

To establish convergent validity, we examined whether factor loadings (FL) exceeded 0.60, ensuring that each item contributed significantly to its respective construct. The average variance extracted (AVE) was also assessed, with all values exceeding the minimum criterion of 0.50, indicating that the constructs captured sufficient variance from their indicators. Discriminant validity was confirmed by verifying that the square roots of the AVE values for each construct were greater than the inter-construct correlations, as recommended by Byrne (2016) and Fornell and Larcker (1981), and Hair et al. (2010). This test ensured that the constructs in the model were theoretically and statistically distinct from one another.

TABLE 2. Interrelations of UTAUT2 Constructs with Discriminant Validity Indicators

| Constructs | PE | EE | SI | FC | HM | PV | HT | INT |

| PE | 0.83 | |||||||

| EE | 0.45 | 0.84 | ||||||

| SI | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.81 | |||||

| FC | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.82 | ||||

| HM | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.84 | |||

| PV | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.81 | ||

| HT | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.82 | |

| INT | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.87 |

| Note: Bolded diagonal elements indicate the square roots of the AVE values, providing evidence for discriminant validity among the constructs. | ||||||||

The structural model was evaluated through SEM to test the hypothesized relationships between the UTAUT2 constructs and preschool teachers’ intention to use DST. Several model fit indices were examined to determine how well the theoretical model aligned with the observed data. The fit indices included the Chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). All indices met acceptable statistical thresholds, confirming a good model fit and supporting the validity of the theoretical framework used in this study.

The results of these analyses, including detailed factor loadings, reliability coefficients, and model fit statistics, are systematically presented in Tables 1 and 2.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Structural Model Analysis

Following the validation of the CFA, path analysis was conducted using SEM to evaluate the fit indices of the UTAUT2 model applied to preschool teachers’ intentions to use DST in early childhood education. The results indicated that the structural model exhibited an acceptable fit, with all indices meeting the recommended thresholds for model adequacy. The fit indices for the model were as follows: χ²/df = 2.85, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.91, Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.94, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.90, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.94, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.04, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.04. These values indicate that the model achieved a good fit with the observed data, supporting the theoretical structure proposed in this study. Additionally, the explanatory power of the model was assessed through the R² value, which measures the proportion of variance explained by the independent variables. The results demonstrated a strong explanatory power, with an R² value of 0.52, indicating that the UTAUT2 model accounted for 52% of the variance in preschool teachers’ intentions to adopt DST in their classrooms.

4.2. Results of UTAUT2 Model

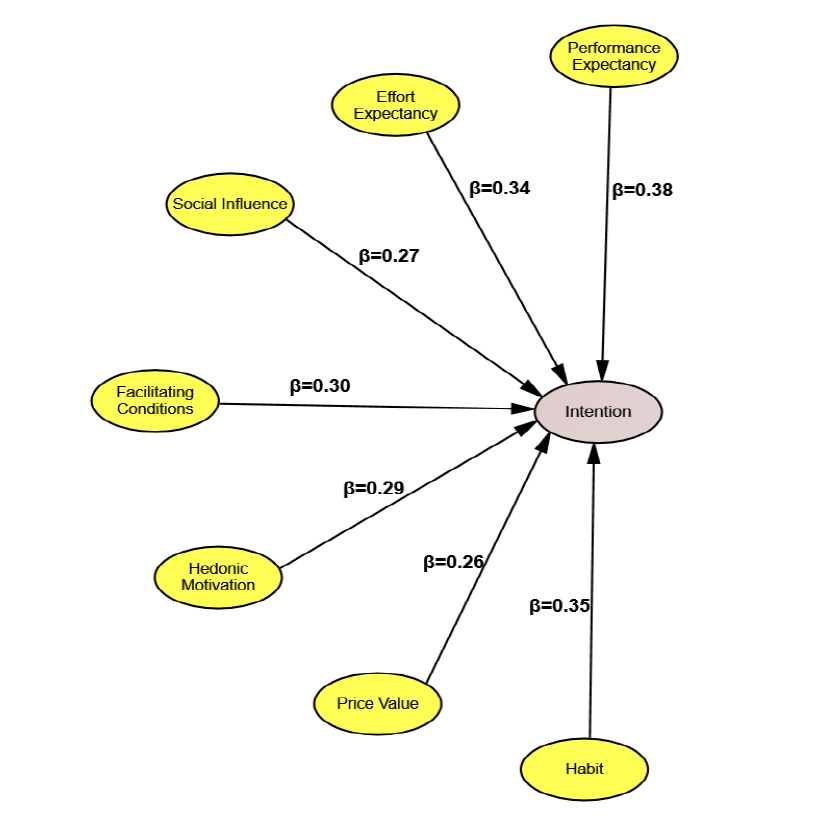

The findings from the structural path analysis provided important insights into the factors that influence preschool teachers’ intentions to DST in early childhood classrooms. The results revealed statistically significant relationships among several UTAUT2 constructs and teachers’ behavioral intentions, as summarized below.

Performance expectancy had a strong, significant positive effect on preschool teachers’ intention to adopt DST (β = 0.38, p < 0.001). This indicates that teachers are more likely to use DST if they perceive it as an effective tool for enhancing student engagement, learning outcomes, and teaching productivity.

Effort Expectancy also emerged as a significant predictor of intention (β = 0.34, p < 0.01), indicating that perceived ease of use plays a central role in teachers’ willingness to adopt DST. Teachers who found DST platforms intuitive and accessible were more likely to report stronger intentions to integrate it into their teaching practices.

Social Influence had a positive and statistically significant relationship with behavioral intention (β = 0.27, p < 0.01). This result suggests that encouragement and support from colleagues, administrators, and other influential stakeholders positively shape teachers’ perceptions and readiness to adopt DST in the classroom.

Facilitating Conditions were also found to significantly influence teachers’ intention to adopt DST (β = 0.30, p < 0.01). Access to necessary infrastructure, training opportunities, and institutional support was critical in supporting preschool teachers’ adoption efforts.

Hedonic Motivation showed a meaningful and positive effect on behavioral intention (β = 0.29, p < 0.05). Teachers who found DST enjoyable and creatively fulfilling were more likely to express intentions to use it in their classrooms. The intrinsic pleasure derived from creating digital stories was an important motiva- tional factor.

Price Value also emerged as a significant factor (β = 0.26, p < 0.05), suggesting that teachers’ perceptions of DST as a cost-effective instructional tool influence their intention to adopt it. When teachers viewed the time, effort, and resources invested in DST as justified by its educational benefits, they were more inclined to adopt it.

Finally, Habit had a strong and statistically significant effect on intention (β = 0.35, p < 0.001). This indicates that teachers who were already familiar with digital tools or regularly engaged with technology-enhanced instruction were more likely to adopt DST as part of their routine teaching practice.

Collectively, these results underscore the multidimensional nature of technology acceptance and highlight the importance of both cognitive evaluations (e.g., usefulness, ease of use) and affective-motivational drivers (e.g., enjoyment, familiarity) in shaping early childhood educators’ adoption of digital storytelling. The detailed standardized path coefficients illustrating these relationships within the UTAUT2 framework are visually presented in Table 3 and Figure 2.

TABLE 3. SEM Results of the UTAUT2 Model

| Hypothesis Number | Path | Standardized Coefficient (β) | t-value | Hypothesis Outcome |

| H1 | Performance Expectancy → Intention | 0.38** | 8.542 | Supported |

| H2 | Effort Expectancy → Intention | 0.34** | 7.926 | Supported |

| H3 | Social Influence → Intention | 0.27* | 5.842 | Supported |

| H4 | Facilitating Conditions → Intention | 0.30* | 6.489 | Supported |

| H5 | Hedonic Motivation → Intention | 0.29* | 6.103 | Supported |

| H6 | Price Value → Intention | 0.26* | 5.774 | Supported |

| H7 | Habit → Intention | 0.35** | 8.321 | Supported |

| Note: p < 0.001, p < 0.0001. | ||||

FIGURE 2. Path Analysis Results of the UTAUT2 Model.

The standardized coefficients indicate the strength and significance of relationships between the constructs based on structural equation modeling.

5. DISCUSSION

This study employed the UTAUT2 model to investigate the factors influencing preschool teachers’ intention to adopt DST in early childhood education. The structural equation modeling results confirmed that all seven constructs—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit—significantly and positively influenced behavioral intention. Among these, performance expectancy and habit were the strongest predictors, indicating that teachers are more likely to adopt DST when they see it as beneficial for teaching and are already familiar with digital tools. Effort expectancy and facilitating conditions also played key roles, suggesting that ease of use and institutional support are important for adoption. Additionally, hedonic motivation and price value contributed to teachers’ intention by highlighting the importance of enjoyment and cost-effectiveness. Overall, the model explained a substantial portion of the variance in adoption intention, offering a validated framework for understanding technology acceptance in early childhood education and practical insights for promoting DST integration in preschool settings.

5.1. Implications

This study makes several important theoretical and practical contributions to the field of educational technology, particularly within the context of early childhood education. By employing UTAUT2 to examine preschool teachers’ intention to adopt DST, the study provides a validated framework that captures how performance-related beliefs, social norms, intrinsic motivations, facilitating conditions, and habitual behaviors influence technology acceptance in a foundational learning environment. This application is especially significant, as research on technology adoption models has primarily focused on secondary or higher education contexts (Al-Adwan & Al-Debei 2024; Ateş & Polat, 2025; Suhail et al., 2014), leaving early childhood education comparatively underexplored.

From a theoretical perspective, this study affirms and extends the validity of UTAUT2 by demonstrating its predictive power in early childhood settings, where pedagogical decisions are heavily influenced by developmentally appropriate practices and resource limitations. All seven hypothesized constructs—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit—were found to significantly influence behavioral intention. This supports earlier studies that found UTAUT2 to be a robust model in educational settings (Ateş & Garzón, 2023; Cabero-Almenara et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2025), while extending its relevance to preschool educators, a group often omitted in mainstream technology acceptance literature (Şakir, 2024). Notably, performance expectancy and habit emerged as the most influential predictors. These findings corroborate Davis’s (1989) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which highlights perceived usefulness as a central determinant of behavioral intention. They also align with recent studies showing that when teachers perceive a tool as enhancing learning outcomes and instruction (e.g., Ateş & Polat, 2025), they are more likely to adopt it. The significance of habit emphasizes the role of prior exposure and routine use of technology, echoing Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior, which suggests that past behavior can strongly inform future intentions. For early childhood educators, who often operate in low-tech environments, the habitual use of digital tools may lower cognitive barriers and increase readiness to integrate DST. The importance of effort expectancy and facilitating conditions further reflects core UTAUT2 assumptions, showing that ease of use and supportive infrastructure are key drivers of technology adoption. These constructs are particularly salient in early childhood settings, where educators may lack consistent access to training or resources. Prior research by Cabellos et al. (2024) and Ogegbo et al. (2024) similarly found that teachers’ technology integration is contingent upon the usability of tools and the availability of institutional support, such as hardware, software, and professional development. This study also advances theoretical understanding by validating the role of hedonic motivation and price value in shaping behavioral intention. The significant influence of hedonic motivation aligns with self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), which emphasizes the importance of intrinsic enjoyment in sustaining engagement. Teachers who find DST enjoyable are more likely to use it—not only for pedagogical utility but also for the personal satisfaction derived from creative teaching. This complements studies by Ateş and Garzón (2022), who highlighted the emotional dimension of digital tool usage as a strong predictor of technology acceptance in education. Moreover, price value, reflecting the perceived trade-off between costs and benefits, reinforces earlier work by Venkatesh (2022), which found that affordability and perceived value strongly influence adoption. In the preschool context, where budgets are often constrained, a tool like DST must demonstrate both low operational cost and high pedagogical payoff to gain teacher acceptance. Collectively, these findings provide empirical support for UTAUT2’s multidimensional structure while demonstrating its adaptability to early childhood education—an area often overlooked in technology acceptance research. This study enriches the literature by showing that technology adoption in early learning environments is influenced not only by rational judgments of utility and support, but also by emotional engagement and habitual practices.

On a practical level, the study offers actionable insights for educators, school leaders, policymakers, and teacher educators aiming to promote the adoption of DST in preschool education. First, professional development programs should focus on demonstrating the pedagogical effectiveness and ease of use of DST tools. Teachers are more likely to adopt such tools when they can clearly see how these resources improve lesson delivery and student engagement. Workshops and hands-on training sessions should include practical examples of classroom integration, highlighting both the instructional benefits and the user-friendly features of DST platforms. Second, institutional support must be enhanced. Schools should ensure that technological infrastructure is readily available, including devices, multimedia resources, and reliable internet access. Moreover, administrators should communicate a clear commitment to supporting innovative teaching practices and provide ongoing technical support and peer mentoring, allowing teachers to adopt DST with confidence and continuity. Additionally, enjoyment and creativity should be emphasized in teacher training, as the study found that hedonic motivation significantly influences adoption intention. Showcasing DST as a playful, expressive, and rewarding experience for teachers—as well as a powerful engagement tool for children—can increase its appeal. Further, cost-related concerns must be addressed. Schools and education departments can facilitate adoption by providing access to free or low-cost DST tools, offering subsidies for software licenses, or integrating DST into broader digital learning strategies. Lastly, policy-level support is essential for scaling DST adoption. Education ministries or local authorities could incorporate DST into early childhood curriculum guidelines, promote best practices through national digital education portals, and support teacher networks that share success stories and resources. Developing these collaborative platforms can foster a culture of innovation, where DST becomes a natural extension of preschool instruction. enhancing both teaching practices and learning experiences in the process.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the factors influencing preschool teachers’ intention to DST in early childhood education through the lens of the UTAUT2. The analysis confirmed that all seven hypothesized constructs—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit—significantly and positively impacted teachers’ behavioral intention to adopt DST. Among these factors, performance expectancy and habit emerged as particularly strong predictors, highlighting the importance of perceived pedagogical value and prior experience with technology in shaping teachers’ intentions. Teachers were more inclined to adopt DST when they recognized its potential to improve student engagement, learning outcomes, and their own teaching efficiency. Similarly, teachers with greater familiarity and comfort with digital tools reported a higher likelihood of integrating DST into their routine practices. Effort expectancy and facilitating conditions were also important, indicating that ease of use and institutional support are essential for successfully implementing DST. Teachers who perceived DST tools as user-friendly and reported access to adequate resources, training, and technical support were more likely to express a strong intention to use them in their classrooms. Moreover, intrinsic enjoyment (hedonic motivation) and perceived cost-effectiveness (price value) were shown to be influential. These findings suggest that both emotional engagement and practical considerations contribute meaningfully to adoption decisions. Overall, the findings highlight the need to develop teacher-centered support systems that address both technical and motivational needs. The study contributes to the theoretical understanding of technology acceptance in early childhood education and offers practical recommendations for designing professional development programs and institutional policies aimed at promoting DST adoption.

6.1. Limitations and future lines of research

While this study provides important insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample consisted only of in-service preschool teachers in Turkey, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other educational contexts or cultural settings. Future research could include comparative studies across different countries or regions to examine potential contextual differences in technology acceptance.

Second, the study relied on self-reported survey data, which may be subject to social desirability bias or inaccuracies in self-assessment. To address this, future studies could incorporate qualitative methods, such as interviews or classroom observations, to enrich the findings and provide a deeper understanding of teachers’ experiences with DST.

Third, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for the examination of changes in intention or behavior over time. Longitudinal research would be valuable for investigating how teachers’ perceptions and use of DST evolve with increased exposure and training.

Additionally, while this study focused on behavioral intention, it did not assess actual usage behavior. Future research could explore the gap between intention and behavior by tracking how frequently and in what ways DST is implemented in real classroom settings.

Finally, this study employed only the UTAUT2 framework. Although comprehensive, UTAUT2 may be complemented by other theoretical models, such as TPACK or TAM3, for a more holistic analysis of digital tool adoption in early childhood education.

Future research could also examine the impact of DST on student learning outcomes and engagement, providing a more complete picture of its effectiveness as a pedagogical innovation. Moreover, exploring how DST can be integrated into specific subject areas—such as language development or social-emotional learning—could further inform best practices in curriculum design and instructional strategy. Importantly, further studies should investigate the practical applications of DST in multicultural classrooms and with students who have diverse educational needs. As interest in inclusive education grows globally, understanding how DST can support engagement and learning among culturally and linguistically diverse students, as well as those with disabilities, represents a valuable direction for future research.

7. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

In accordance with the CRediT taxonomy, all aspects of this study were carried out solely by the author. This includes conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, validation, and visualization. The author also wrote the original draft of the manuscript and completed all review and editing.

8. fUNDING

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

9. referencEs

Adara, R. A. (2020, August). Improving early childhood literacy by training parents to utilize digital storytelling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Early Childhood Education and Parenting 2019 (ECEP 2019) (pp. 199–203). Atlantis Press.

Addone, A., Palmieri, G., & Pellegrino, M. A. (2021, September). Engaging children in digital storytelling. In S. Rodríguez-González et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference in Methodologies and Intelligent Systems for Technology Enhanced Learning (pp. 261–270). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86618-1_26

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Al-Adwan, A. S., & Al-Debei, M. M. (2024). The determinants of Gen Z’s metaverse adoption decisions in higher education: Integrating UTAUT2 with personal innovativeness in IT. Education and Information Technologies, 29(6), 7413-7445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12080-1

Al-khresheh, M. H., Mohamed, A. M., & Shaaban, T. S. (2024). A quasi-experimental study on the effectiveness of augmented reality technology on english vocabulary learning among early childhood pupils with learning disabilities. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 10(2), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.102.2024.17823

Ateş, H., & Garzón, J. (2022). Drivers of teachers’ intentions to use mobile applications to teach science. Education and Information Technologies, 27(2), 2521-2542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10671-4

Ateş, H., & Garzón, J. (2023). An integrated model for examining teachers’ intentions to use augmented reality in science courses. Education and Information Technologies, 28(2), 1299-1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11239-6

Ateş, H., & Gündüzalp, C. (2025). Proposing a conceptual model for the adoption of artificial intelligence by teachers in STEM education. Interactive Learning Environments, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2025.2457350

Ateş, H., & Kölemen, C. Ş. (2025). Integrating theories for insight: an amalgamated model for gamified virtual reality adoption by science teachers. Education and Information Technologies, 30(2), 123–2153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12892-9

Ateş, H., & Polat, M. (2025). Exploring adoption of humanoid robots in education: UTAUT-2 and TOE models for science teachers. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 12765–12806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-025-13344-8

Berkovich, I., & Hassan, T. (2024). Principals’ digital instructional leadership during the pandemic: Impact on teachers’ intrinsic motivation and students’ learning. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(4), 934-954. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432221113411

Bethencourt-Aguilar, A., Fernández Esteban, M. I., González Ruiz, C. J., y Martín-Gómez, S. (2021). Recursos Educativos en Abierto (REA) en Educación Infantil: características tecnológicas, didácticas y socio-comunicativas. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 7(2), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2021.v7i2.12273

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Cabellos, B., Siddiq, F., & Scherer, R. (2024). The moderating role of school facilitating conditions and attitudes towards ICT on teachers’ ICT use and emphasis on developing students’ digital skills. Computers in Human Behavior, 150, 107994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107994

Cabero-Almenara, J., Palacios-Rodríguez, A., Loaiza-Aguirre, M. I., & Andrade-Abarca, P. S. (2024). The impact of pedagogical beliefs on the adoption of generative AI in higher education: predictive model from UTAUT2. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 7, 1497705. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2024.1497705

Catalano, H., & Catalano, C. (2022). Using digital storytelling in early childhood education to promote child centredness. In I. Albulescu & C. Stan (Eds.),Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2021 (Vol. 2, pp. 169–179). European Publisher.https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.16

Chang, C. Y., & Chu, H. C. (2022). Mapping digital storytelling in interactive learning environments. Sustainability, 14(18), 11499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811499

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Duer, J. K., & Jenkins, J. (2023). Paying for preschool: who blends funding in early childhood education? Educational Policy, 37(7), 1857-1885. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 08959048221103804

Esfandiar, K., Dowling, R., Pearce, J., & Goh, E. (2020). Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: an integrated structural model approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(1), 10–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1663203

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/3151312

Gravetter, F. J., & Forzano, L. B. (2012). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

Hartsell, T. (2017). Digital storytelling. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 13(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijicte.2017010107

Hoa, L., & Minh, L. (2023). ‘A double-edged sword?’ Digital storytelling for early childhood education: Vietnamese teachers’ beliefs and practices. Journal of Educational Management and Instruction (JEMIN), 2(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.22515/jemin.v2i2.5465

Hu, L., Wang, H., & Xin, Y. (2025). Factors influencing Chinese pre-service teachers’ adoption of generative AI in teaching: an empirical study based on UTAUT2 and PLS-SEM. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 12609–12631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-025-13353-7

Jalongo, M. R. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 on early childhood education and care: Research and resources for children, families, teachers, and teacher educators. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(5), 763-774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01208-y

Jitsupa, J., Nilsook, P., Songsom, N., Siriprichayakorn, R., & Yakeaw, C. (2022). Early Childhood Imagineering: A Model for Developing Digital Storytelling. International Education Studies, 15(2), 89-101. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v15n2p89

Kisno, K., Wibawa, B., & Khaerudin, K. (2022). Development of digital storytelling based on local wisdom. Wisdom, 4(3), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.24234/wisdom.v4i3.834

Kline, P. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

López Marí, M., Sánchez Cruz, M., y Peirats Chacón, J. (2021). Los recursos educativos digitales en la atención a la diversidad en Educación Infantil. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 7(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2021.v7i2.12256

Losi, R., Tasril, V., Widya, R., & Akbar, M. (2022). Using storytelling to develop English vocabulary on early age children measured by mean length of utterance (MLU). International Journal of English and Applied Linguistics (IJEAL), 2(1), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.47709/ijeal.v2i1.1470

Maranatha, J., Wulandari, H., & Briliany, N. (2024). Early empathy: Impact of digital storytelling, traditional-storytelling, and gender on early childhood. JPUD - Jurnal Pendidikan Usia Dini, 18(1), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.21009/jpud.181.16

Ogegbo, A. A., Penn, M., Ramnarain, U., Pila, O., Van Der Westhuizen, C., Mdlalose, N., ... & Bergamin, P. (2024). Exploring pre-service teachers’ intentions of adopting and using virtual reality classrooms in science education. Education and Information Technologies, 29(15), 20299-20316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12664-5

Purnama, S. (2021). Teacher’s experiences of using digital storytelling in early childhood education in Indonesia: A phenomenological study. Jurnal Pendidikan Islam, 10(2), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.14421/jpi.2021.102.279-298

Purnama, S., Ulfah, M., Ramadani, L., Rahmatullah, B., & Ahmad, I. (2022). Digital storytelling trends in early childhood education in Indonesia: A systematic literature review. JPUD - Jurnal Pendidikan Usia Dini, 16(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.21009/jpud.161.02

Rahiem, M. D. (2021). Storytelling in early childhood education: Time to go digital. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 15(4), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-021-00081-x

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037110003-066X.55.1.68

Sabari, N., & Hashim, H. (2023). Sustaining education with digital storytelling in the English language teaching and learning: A systematic review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(4), 208-224. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v13-i4/16860

Suhail, F., Adel, M., Al-Emran, M., & AlQudah, A. A. (2024). Are students ready for robots in higher education? Examining the adoption of robots by integrating UTAUT2 and TTF using a hybrid SEM-ANN approach. Technology in Society, 77, 102524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102524

Sunar, P., Dahal, N., & Pant, B. (2022). Using digital stories during COVID-19 to enhance early-grade learners’ language skills. Advances in Mobile Learning Educational Research, 3(1), 548–561. https://doi.org/10.25082/amler.2023.01.003

Sungur-Gül, K., & Ateş, H. (2021). Understanding pre-service teachers’ mobile learning readiness using theory of planned behavior. Educational Technology & Society, 24(2), 44-57.

Şakir, A. (2024). Augmented reality in preschool settings: a cross-sectional study on adoption dynamics among educators. Interactive Learning Environments, 33(4), 2954-2977. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2024.2428361

Şimşek, A. S., & Ateş, H. (2022). The extended technology acceptance model for Web 2.0 technologies in teaching. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational İnnovation, 8(2), 165-183. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2022.v8i2.15413

Tang, X., Yuan, Z., & Qu, S. (2025). Factors Influencing University Students’ Behavioural Intention to Use Generative Artificial Intelligence for Educational Purposes Based on a Revised UTAUT2 Model. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 41(1), e13105. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.13105

Venkatesh, V. (2022). Adoption and use of AI tools: a research agenda grounded in UTAUT. Annals of Operations Research, 308(1), 641-652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03918-9

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 157-178. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410412

Yang, Y. T. C., Chen, Y. C., & Hung, H. T. (2022). Digital storytelling as an interdisciplinary project to improve students’ English speaking and creative thinking. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 840-862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1750431

Yuksel-Arslan, P., Yildirim, S., & Robin, B. R. (2016). A phenomenological study: teachers’ experiences of using digital storytelling in early childhood education. Educational Studies, 42(5), 427-445. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2016.1195717

Zheng, H., Han, F., Huang, Y., Wu, Y., & Wu, X. (2025). Factors influencing behavioral intention to use e-learning in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analytic review based on the UTAUT2 model. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 12015–12053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13299-2