Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation Vol. 11. No. 2. December 2025 - pp. 82-102 - ISSN: 2444-2925

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.112.2025.21195

Maker Education in Primary School: A Qualitative Study of Guidance and Evaluation of Teacher Training

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, society has undergone social and economic changes, making it crucial to train young people to cope with this new reality. Digital technologies (DT) have transformed all areas of human life (Sánchez-Caballé et al., 2020), requiring continuous reflection on the effectiveness of strategies to develop digital competencies in an evolving information society (Morales et al., 2020; Tomczyk et al., 2023). Digitalisation, which has accelerated in the 21st century, requires citizens to adopt new strategies to face new challenges.

Over the recent years, educational research has significantly influenced teaching practices and perspectives on the learning process (Bautista-Vallejo y Hernández-Carrera, 2020). At the same time, it has evidenced the challenges faced by teacher training institutions in integrating technology into education (Santos et al., 2023). These challenges are especially pronounced when considering the gender digital divide, which has a profound impact, ultimately influencing future decisions regarding access and use of Information and Communication Technology ICT (Morante et al., 2020). Moreover, it is essential to rethink educational models in order to equip students with creative skills, problem-solving abilities, and technical-scientific competencies (Ruiz-Ortiz, 2023).

In this context of change, maker education has emerged as an innovative response that seeks to harness resources and solve everyday problems (Domínguez-González et al., 2018; Spieler et al., 2022). Indeed, creation, experimentation, and the art of making have existed ever since people have needed to develop tools and materials to face new challenges (Martin et al., 2020). In this sense, the teaching-learning process in maker education is based on the creation and modification of artefacts, whose final product aims at responding to a specific problem related to the environment of the educational community in which the project is developed (Blikstein, 2014). Specifically, in recent decades, many primary school teachers have shown interest in integrating maker culture into STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics) in order to motivate pupils to actively participate in the teaching-learning process (Weng et al., 2022).

Parallel to this reality, makerspaces have been built in schools and public spaces (Rodríguez-Calderón y Belmonte-Izquierdo, 2021), where design and digital fabrication processes can be put into practice with digital tools such as 3D printers, laser cutters or cutting plotters. In fact, they are becoming an increasingly significant focus in education (Nikou, 2024). Fundamentally, it is a space where pupils use materials and resources to explore and experiment (Lock et al., 2020) and where they can develop several skills (Domínguez-González et al., 2018). In fact, Quintana-Ordorika et al. (2024) argue that integrating technology into the design and creation of artifacts is key to improving the learning experience. Countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan have already undertaken these initiatives, according to Bevan (2017). Indeed, in the Spanish context, the autonomous community of Catalonia is also working to introduce a maker culture through the FAIG project (Silva et al., 2024) and the integration of maker spaces in schools and high schools.

But, how is maker education defined? Specifically, it is defined as the combination of practice and development of skills, humanities, arts and knowledge (Lin et al., 2021). Fleming (2015) also describes it as a way of turning knowledge into action. Lundberg and Rasmussen (2018), above all, emphasize the importance of the learner creating an artefact in maker projects. However, among all the definitions, one of the most complete is that of Veldhuis et al. (2021), who defines it as “project-based learning through activities that focus on designing, building, modifying and/or reusing material objects with the aim of producing, through traditional craft techniques or digital technologies, some kind of ‘product’ that can be used, interacted with or demonstrated” (Veldhuis et al., 2021, p.1).

In particular, the current trend suggests that the concept of maker education is being introduced in a practical way through STEAM (Lin et al., 2021; Weng et al., 2022), as they complement each other; while the first can offer originality and the more creative part of design and creation, the second focuses on the transversality between these areas. This connection is also because STEAM activities, like maker activities, are related to solving everyday problems (Weng et al., 2022).

Maker education benefits pupils’ holistic development, particularly by fostering creativity (Jia et al., 2021) and enabling the generation of new ideas (Alekh et al., 2018). In fact, it is effective when it promotes exploration and creativity (Spieler et al., 2022) and positively influences pupils’ maker mindset, self-efficacy, motivation and interest (Martínez-Moreno et al., 2021; Hwang, 2017). Learning by doing enhances meaningful knowledge acquisition (Domínguez-González et al., 2018) and engages unmotivated pupils through exploration and experimentation (Otero & Blikstein, 2016). New challenges foster ongoing knowledge growth (Shively et al., 2021). Similarly, teamwork in maker education allows pupils to collaborate across different levels and areas (Torralba, 2019), encouraging mutual support (Forbes et al., 2021).

Since its beginnings, maker education has focused on creating without fear of error (Torralba, 2019). There is a need to communicate that it is positive to learn from mistakes without being afraid to try (Hughes et al., 2021). It is interesting to integrate mistakes as an important part of the teaching-learning process (Hughes et al., 2021), while promoting a safe environment where pupils are encouraged to take risks (Hughes et al., 2021). Frustration is initially an obstacle but it must gradually be transformed into motivation (Domínguez-González et al., 2018). The acceptance of the process of failure in the school is essential for the successful implementation of maker pedagogy. (Stevenson et al., 2019).

Maker education not only enhances cognitive and motivational skills but also addresses pupils’ socio-emotional development (Carrasco & Valls, 2023). Studies show its positive impact on pupils with special educational needs. Lee et al. (2020) found in their cross-case qualitative approach that maker education effectively supported pupils with disabilities and low academic achievement. Similarly, Martin et al. (2020) demonstrated in their mixed methods study that autistic pupils successfully completed projects and improved their communication skills through a maker program. Hughes et al. (2018) highlight that maker education benefits learners with disabilities, learners with scattered attention and those with low motivation, often surprising pupils who typically struggle with academic performance.

Maker education enhances pupils’ problem-solving skills by encouraging real-world solutions (Bevan, 2017; Forbes et al., 2021). Studies confirm significant improvements through maker interventions (Forbes et al., 2021; Stevenson et al., 2019). Given the benefits that maker education brings to pupils, teachers should promote this approach in the classroom. As these are approaches that present unconventional challenges to pupils (Torralba, 2019), teachers need guidance in designing, implementing, and evaluating maker projects (Forbes et al., 2021). For instance, Rodríguez-Calderón y Belmonte-Izquierdo (2021) propose a strategy to support teachers in selecting learning objectives, developing science and engineering activities, supporting planning and time management, and providing specific tools to develop a maker mindset.

However, public schools do not currently have sufficient financial resources to equip themselves with digital tools (Domínguez-González et al., 2018). While the importance of teacher training is recognized, there is a lack of research on both how to effectively prepare primary school teachers (Stevenson et al., 2019) and what the key challenges and opportunities are (Ioannou & Gravel, 2025). However, a clear consensus on its effectiveness in improving K-12 students’ learning outcomes is still lacking (Lu & Zeng, 2025). To address this issue, this article explores in depth how teachers in two schools in the province of Tarragona (Spain) are supported during the integration process of Maker Education into their primary schools. Specifically, the training process is part of an educational project that aims, on the one hand, to provide these schools with digital and technological tools related to Maker Education (3D printers, laser cutters, vinyl cutters, among others) and, on the other hand, to provide pedagogical training to the teachers on how to use all these tools to improve the teaching-learning process of the pupils. In addition, the creation of a makerspace in each institution will be promoted to encourage these maker practices in the educational centres of Catalonia.

Therefore, the main aim of this research is to study the implementation of training for primary school teachers to introduce Maker Education in the classroom. To achieve this, the study focuses on two specific objectives: first (SO1), to determine the key aspects addressed in teacher training for implementing Maker Education, and second (SO2), to identify its strengths and weaknesses from the perspective of primary school teachers. Based on these objectives, the research seeks to answer two central questions: What aspects are covered in the training of primary school teachers for the implementation of Maker Education? What are the strengths and weaknesses of this training according to teachers’ perspectives?

2. MATERIAL AND METHOD

A qualitative methodology was adopted, with an interpretative approach, aimed at making sense of research events and interpreting them from a participating teacher’s perspective, with a view towards deepening in a particular case (Bisquerra, 2009).

The purpose of this design is to understand and identify in depth the aspects involved in the support and training of teachers in two schools in the province of Tarragona, to understand what this training brings to the teachers and the possible ways of improving it.

2.1. Instruments and procedures

In order to address the first specific objective (SO1), observations were made during the training sessions. A total of six sessions were held each month between January and July. The trainers support the whole school staff in the pedagogical application of maker education in their school. Observations make it possible to capture how the training process is implemented in its real context, providing a detailed perspective (Herrera, 2017). To collect this information, a rubric designed by Nadal et al. (2024) is used (Annex 2).

Specifically, this rubric was designed through an iterative process to evaluate the support provided to teachers in implementing maker education in schools. The initial prototype was developed during the TECLA project (2021-2022) and tested with teachers at one school in Barcelona. A Likert scale was used for evaluation, with an additional comments section for qualitative insights. Based on observations and feedback, the rubric underwent revisions, leading to a second prototype with 11 categories, incorporating new sections. The rubric aims to provide a comprehensive tool for assessing teacher training effectiveness in maker education, ensuring a structured and inclusive approach.

In concrete, it is focused on analysing the key aspects that ensure effective and enriching teaching for teachers in the context of educational maker activities. It has a total of 11 items, each divided into 2 to 6 sub-items. Key elements such as the promotion of active pupils’ participation, the appropriate and safe use of tools or the teacher’s ability to adapt resources to the needs and characteristics of the pupils are addressed. Attention is also paid to the management of time and pace of work, or the promotion of creativity and autonomy of pupils, both at individual and group level. Finally, interdisciplinary approaches are also included, such as optimising workspaces or effectively integrating pupils with special needs, prioritising both, equity and diversity, in the classroom.

The rubric consists of 4 evaluation indicators, ranked from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much), which allow a detailed assessment of the teacher’s performance on each item. In particular, the frequency with which each item is performed during the session is assessed. In addition, each indicator includes a comments section, which allows additional observations to be added to complement the analysis and to go into greater depth on the most relevant aspects of the process. Table 1 below provides a brief description of the rubric items:

TABLE 1. Summary of rubric items

| 1. Support in encouraging student participation | Focuses on maintaining engagement, fostering interaction, and promoting motivation while shifting responsibility to pupils. |

| 2. Use of technological tools | Emphasizes the easy introduction of technological tools, promoting curiosity and confidence, and ensuring safety aspects when using machines and tools. |

| 3. Design and session planning | Stresses aligning resources with pupils abilities, age, and curriculum goals. |

| 4. Time management and work pace | Ensures activities fit within time limits and match pupils’ levels. |

| 5. Cognitive work | Planning tasks that pupils can connect to real-world experiences by proposing practical applications. |

| 6. Creativity | Encouraging the development of new ideas to enhance pupils’ work while promoting originality. |

| 7. Autonomy/Group work | Focuses on equitable task distribution and conflict resolution. |

| 8. Project-Based Learning | Integrating multiple disciplines and including effective pupils’ assessment within this framework. |

| 9. Spaces | Optimizing physical environments for maker activities, considering clean/dirty areas. |

| 10. Students with special needs | Ensures inclusion of pupils with special needs and satisfies socio-emotional needs. |

| 11. Equity | Fostering fairness and reducing gender inequalities. |

TABLE 2. Summary of interview questions

| Maker and STEAM | Concept of maker education: Inquires about how teachers understand maker education, their general vision, and how it can contribute to achieve learning competencies and objectives. |

| Interaction with pupils: Explores the advantages and disadvantages of applying maker approach in the classroom, including how it helps promoting pupils interaction and engagement. | |

| STEAM implementation: Focuses on how they apply STEAM in their classroom, and how they integrate it with maker activities. | |

| Project-Based Learning | Methodologies used: Determines what strategies are used in the classroom to implement project-based learning. |

| Integrating maker education: Inquires how teachers integrate maker education into project-based learning. | |

| Pupils motivation: Analyses whether they have evidences of greater motivation, predisposition or interest in learning when working on projects or using technology. | |

| Educational maker project | Knowledge of the project: Asks what teachers know about the project and what they expected from it. |

| Evaluation of support: Assesses the support provided to the schools involved in the project. | |

| Suggestions for improvement: Seeks feedback on areas of improvement in the training process and whether anything was lacking. |

On the other hand, to address the second specific objective (SO2), semi-structured interviews were conducted with 3 teachers from each school participating in the project. One of these participants was the head teacher of the school. The interviews were conducted at the end of the school year, in July 2024, after the training sessions had been completed, with the aim of obtaining an overall view of the training received. Through these interviews, the aim was to analyse how to adapt these practices pedagogically, how to develop the competences and motivation of pupils, or how to identify challenges and opportunities for their effective application in real educational contexts. Annex 1 contains all the interviews conducted, which complement and enrich the analysis presented. The semi-structured interviews were based on three main axes, described in table 2 in previous page.

2.2. Participants

For this study, a non-probabilistic purposive sampling, typical of qualitative research, was used. The participants were, therefore, teachers belonging to schools where maker education was applied, and were already equipped with the tools that the Catalan government offers to schools. The sample participating in this study is a total of 8 primary school teachers from the Autonomous Community of Catalonia (Spain), specifically from two schools in the province of Tarragona.

The schools gave permission to access their classrooms in order to analyse the training process. The training team also gave permission to access the support sessions, which greatly facilitated the data collection process. The selection of these two schools was strategic because, on the one hand, one of them has been integrating technology into its educational practice for a long time and the teaching staff is already trained in the integration of technological resources in the classroom. On the other hand, the other school was chosen because it did not have as much experience in the use of technology in the classroom. This way, a more global and representative view of the impact of maker education in the educational environment can be obtained.

Both schools have two other elements in common. Firstly, they have a similar pupils’ profile. They are complex schools where most of the pupils come from different developing countries. There are very few local pupils. Although one is very central and the other one is on the outskirts of the same city, the neighbourhoods are similar, and both have a very similar family profile. Another common element is their participation in the same Maker Program, which integrates technology and pedagogical innovation into the classroom. The aim of this program is to promote the use of ICT through new methodologies to improve the teaching-learning process for pupils, especially in STEAM areas. The main participants in the Maker Program are 150 public schools throughout Catalonia. The following section describes the characteristics of the program in more detail.

2.3. Maker program

The program has a total duration of 4 academic years. Specifically, the sessions analysed correspond to one year of training. It consists of 6 sessions with a duration of 2 hours each, hence totalling 12 hours all the way through an academic year.

FIGURE 1. Overview of the Training Contents

Firstly, these centres receive an equipment package and are required to set up a makerspace. The space is equipped with advanced technology such as 3D printers, vinyl cutters, laser cutters or digital embroidery machines, among others. The program also includes pedagogical training on how to integrate these technological and digital tools to improve the teaching-learning process of pupils. Hands-on learning is encouraged, and teachers are supported to integrate maker education into their classrooms. To summarise what the training process and support consist of, the following figure (figure 1) shows some of the content covered during training.

This program follows the Framework for Evaluating Making in STEM Education (Marshall & Harron, 2018), which suggests five key sections for assessing maker competence: Ownership/Empowerment, Maker Habits, Production of an Artefact, Collaboration, and STEM Tools. The relationship between training content and the principle of this framework is then established, highlighting how it promotes meaningful and practical learning for teachers:

TABLE 3. Relationship between training content and framework

| Dimension | Relation with teacher training |

| Ownership/ Empowerment | Pedagogical support and practical learning promote teacher’s and pupil’s autonomy, allowing pupils to be the protagonists of their own learning. The training also promotes the integration of maker-based learning for the integral development of the teacher and, in the end, of the pupils. |

| Maker habits | The training process aim to strengthen teachers’ maker skills so that they can transfer these skills to their pupils. The training encourages the acquisition of essential habits such as experimentation, iteration and critical thinking. It also creates a direct link between the activities teachers design and pupils’ everyday experiences, allowing them to integrate the knowledge and skills they acquire in the classroom into their daily lives, enriching their learning beyond the school environment. |

| Production of an Artifact | The program trains teachers to design, implement and evaluate maker activities in the classroom, in some cases with the end goal of creating an artefact. This approach allows teachers to integrate advanced technological tools into projects that promote hands-on and meaningful learning. In addition, each school has a makerspace for the production of these artefacts, giving pupils a dedicated place to realise their projects. Guidance is given on how to integrate transversality into the projects. In short, the aim is for teachers to be able to integrate content from different subjects, especially in STEAM areas, thus promoting interdisciplinary learning. |

| Collaboration | The training process promotes collaboration between teachers, as well as showing how to foster collaboration among pupils in maker projects. It emphasises the importance of taking into account the individual needs of each pupil and how to organise groups fairly to ensure active and equitable participation for all. The pedagogical support also promotes the exchange of experiences and good practices among teachers, enriching their work in the classroom. In fact, during the training process, discussion areas are created among teachers from the same school, but also among other teachers from nearby schools. |

| STEM tools | The training process also focuses on the correct use of advanced STEM tools, such as 3D printers, laser cutters and digital embroidery machines, and provides teachers with indications on their use and pedagogical application. Each centre has a makerspace equipped with these tools, allowing pupils to develop technology projects in a hands-on way. Teachers are also taught how to effectively integrate these technologies into the classroom to enhance pupils’ learning. |

2.4. Data analysis

An analysis of the rubric was conducted to assess the different aspects of teacher training. At the end of the observation process, the completed rubrics were analysed to identify patterns and trends. The analysis focused on determining the most frequently occurring rating for each item across all sessions.

The interviews were transcribed into a text file and then processed using the software ATLAS.ti 24.2.1 (Qualitative Research and Solutions). The analysis was then carried out in the following order: 1. Preparation and import of the interviews; 2. Creation of codes and sub-codes; 3. Analysis of the results and creation of networks. According to Lopezosa et al. (2022), this analysis allows the identification of the most salient aspects of the statements and also helps to identify patterns.

3. RESULTS

The first specific objective (SO1) was to determine which aspects are dealt with during teacher training. Table 4 shows in general terms which aspects the program focuses on. The left column shows the items that were to be observed. These items are the same as those used in the observation rubric by Nadal et al. (2024) in order to understand how the course develops, as well as the main content developed during training.

The second and third columns show the observation results for each item at each school analysed. In the last two columns, each item is rated. Specifically, it is a table of the frequency of actions. This rating starts with the lowest values (Not at all), which means that the content was never dealt with; secondly, the content was dealt with slightly (Slightly); thirdly, the content was dealt with significantly (Moderately); and finally, the content was dealt with a very significant number of times (Considerably). In table 4 (see next page) is a summary of the topics covered in the sessions.

TABLE 4. Sessions content summary

| ITEM | QUALIFICATION SCHOOL 1 | QUALIFICATION SCHOOL 2 |

| 1. Support in encouraging student participation | Slightly | Slightly |

| 2. Use of technological tools | Slightly | Slightly |

| 3. Design and session planning | Moderately | Moderately |

| 4. Time management and work pace | Slightly | Slightly |

| 5. Cognitive work | Considerably | Slightly |

| 6. Creativity | Moderately | Slightly |

| 7. Autonomy/Group work | Slightly | Slightly |

| 8. Project-Based Learning | Moderately | Moderately |

| 9. Spaces | Slightly | Slightly |

| 10. Students with special needs | Slightly | Not at all |

| 11. Equity | Slightly | Slightly |

At first sight it can be seen that in most cases the content is dealt with slightly and moderately. This aspect is considered to be positive as it means that most aspects are covered in the training period. There are, however, some exceptions, e.g. item 10 on pupils with special needs, where very little work is done in the first school and practically none in the second one. In general, it can also be observed that for most of the items both schools treat the content in a similar way.

The items are described and compared between the two schools, highlighting their similarities and differences, to discuss each case or context individually. In the first item, pupils’ participation is not very much encouraged in both schools (1. Support in encouraging pupils’ participation). The same is true for the second item (2. Use of technological tools). In both schools, training in the use and application of tools is provided during one of the sessions, but not specifically during the other sessions.

It is relevant that item 3 (Design and session planning) is moderately addressed in both schools; in this case the trainer puts a lot of emphasis on how to design and plan sessions to introduce maker activities in the classroom. However, item 4 (Time management and work pace) is not fully promoted, with the qualification being slightly in both schools. In item 5 (Cognitive work) there are differences between the two schools. In the first school, there is a strong focus on cognitive work during the training sessions, whereas in the second school there is no focus on these aspects. This may be related to the fact that the second centre, unlike the first one, had already carried out maker activities before, which meant that many activities were already contextualised to the pupils’ environment and their everyday life. Item 6 (Creativity) also shows differences between the two schools, with the first one working more on creativity-related aspects than the second one. On the other hand, items 7 (Autonomy/group work) and 9 (Spaces) are hardly addressed in the training sessions, in contrast to item 8 (Project-based learning) where a stronger focus is observed.

Finally, as a weakness to be pointed out, there is not much emphasis on the promotion of equity among pupils, nor is much attention paid on how to promote the inclusion of pupils with special needs (items 10 and 11). In fact, in the first school, item 10 (Pupils with special needs) is hardly addressed, while in the second school this content is not addressed at all.

In short, it can be concluded that the sessions have a very specific focus on aspects such as design or the use of machines. Based on these results, it can be observed that some elements are transversal over several sessions, such as the interest of pupils (little promoted, but considered over several sessions). On the other hand, aspects such as training in the use of tools, are dealt with intensively in very few sessions.

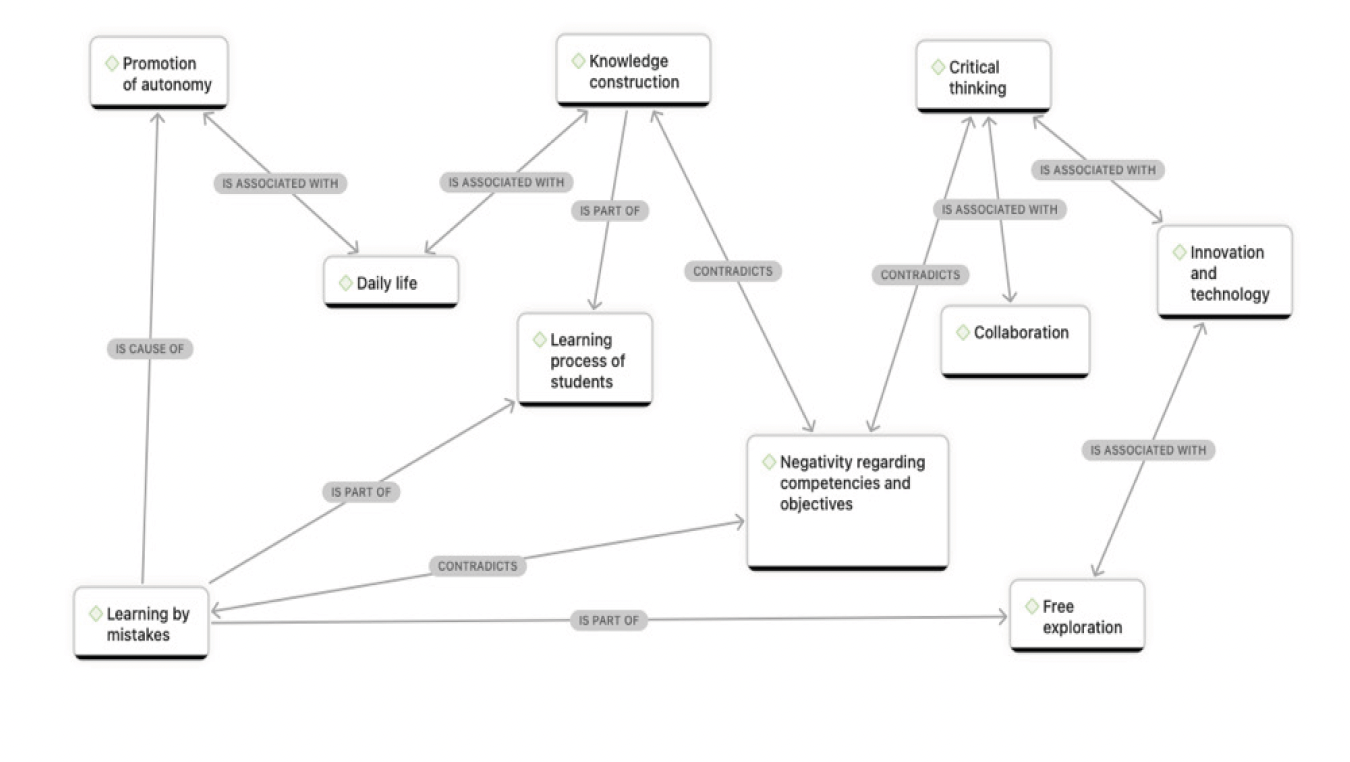

The second specific objective (SO2) was focused on identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the training process, from the perspective of primary school teachers. After the analysis, a total of 388 quotations with a total of 47 codes were selected. The following diagram shows, the groupings into networks, which represent the teachers’ assessment. First, conceptual network 1 (Figure 2) refers to positive outcomes and potential challenges:

FIGURE 2. Positive outcomes and potential challenges

Conceptual network 1 (Figure 2) shows the potential of introducing maker education to pupils. Indeed, teachers admit that simulations have given them some practice in implementing maker activities and getting pupils excited. In addition, they point out that pupils’ interest increases significantly when technology is introduced into the classroom, as it is attractive and generates greater enthusiasm during the sessions:

‘’Yes, for them technology is part of their daily life, much more than for us, and they find it easy and exciting, that’s true.’’ (Teacher 2, School 1)

However, they also confirm some difficulties in the classroom when implementing the activities. In particular, they refer to the diversity of learners with different needs and the personalisation of learning. Overall the teachers confirm that they have acquired a number of skills and knowledge during training, such as the ability to stimulate pupils’ interest or the integration of technology and the promotion of creativity.

FIGURE 3. Pupils’ learning process

Conceptual network 2 (Figure 3) shows the interrelationship between the different benefits for learners and reflects a close link between learning by error and the other elements. It is also seen by teachers as one of the reasons why pupils become more autonomous and learn through exploration. The importance of constructing knowledge based on their interests, often related to their everyday lives, is emphasised, and can lead to more meaningful learning:

“It makes them take it more personally and go deeper into the content because they are the ones really building the knowledge by doing it.” (Teacher 4, School 1)

Similarly, in terms of critical thinking, the interviewees saw it as closely linked to collaboration and aspects of innovation and technology. Some of them have already worked with transversal projects and are now able to give them a new maker approach. In parallel, they state that activities based on real life contexts have had a positive impact, allowing pupils to see the practical application of what they have learned, as opposed to previous approaches that focused on theoretical activities or simulations that had little to do with everyday life.

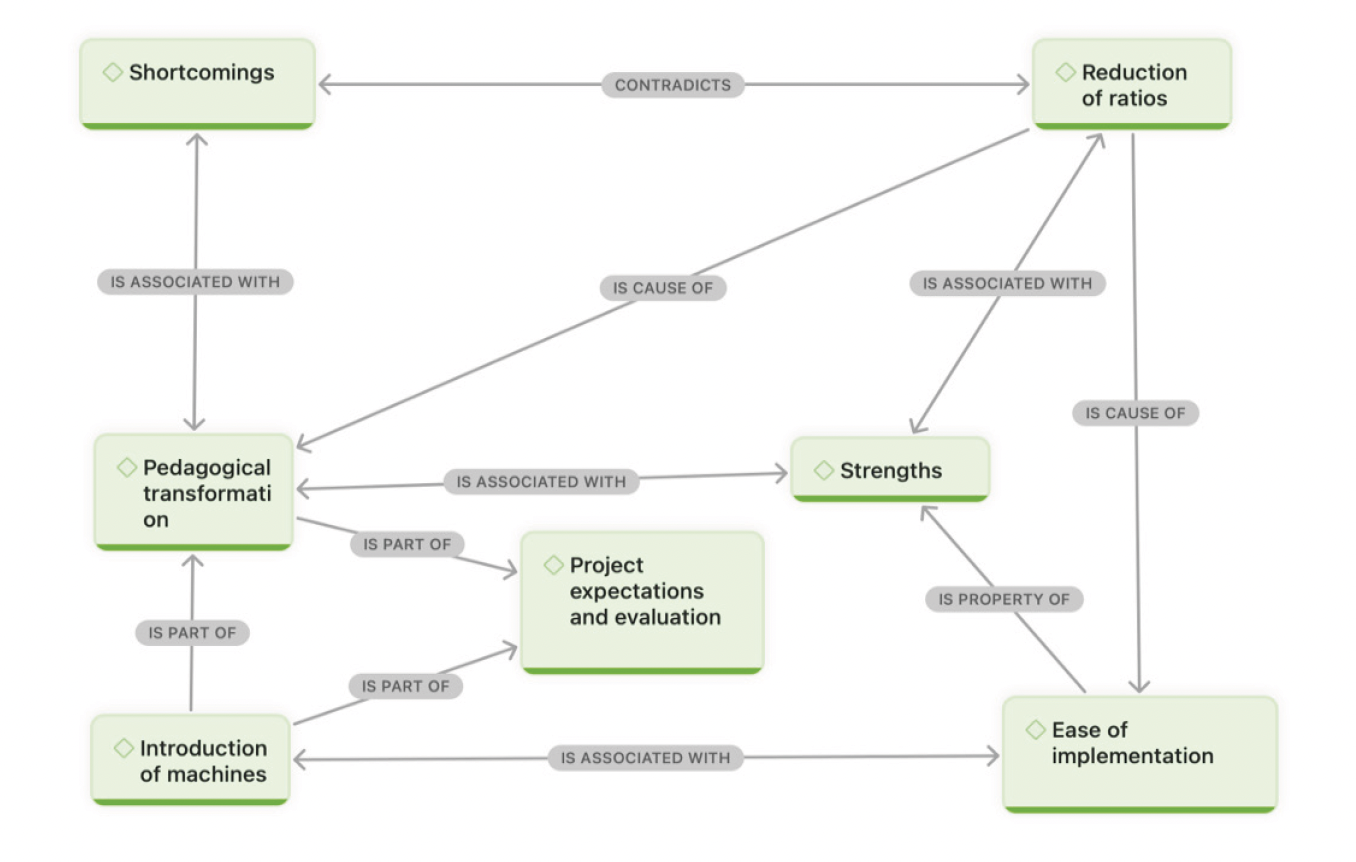

Conceptual network 3 (Figure 4) shows that, after training, teachers consider it key learning by doing and associate it with making, building and project-based work. Some teachers state that, after the training period, they understand the maker philosophy as something that goes beyond the simple act of creating objects and is linked to sustainability, being transferable to their everyday lives:

“I don’t know, with the children we end up getting them to think about being creators of what they need rather than consumers.” (Teacher 5, School 2)

FIGURE 4. Balancing knowledge, competencies and innovation

In relation to conceptual network 4 (Figure 5), they highlight pedagogical transformation as a strength derived from the training received. They emphasise the ease of implementation in the classroom and the gradual introduction of maker education. They also highlight as a strength the sessions designed to share experiences among teachers, as they encourage reflection and exchange of ideas.

FIGURE 5. Project expectations and final opinions

Despite some reluctance at the beginning, as the training sessions progressed, teachers came to appreciate the impact on their pupils’ skills and the learning they had acquired. Among other aspects, they appreciate the strategies and tools provided by the trainer, who accompanies them at all times. Undoubtedly, one of the most important aspects for the teachers is that the training is specifically personalised. Not only is it adapted to their needs, but it also responds to the practices and challenges of implementation in the classroom:

“It’s very tailored to what we need, and very practical ideas for projects are being suggested. That adds a lot of value to the project because rather than being something generalised a more personalised support is being offered”. (Teacher 3, School 1)

Another positive point they highlight is the opportunity to share training with teachers from other schools. This approach encourages the exchange of experiences and allows professionals to share experiences and strategies for overcoming challenges in similar contexts.

Overall, the evaluation of the training was positive but teachers also share some challenges that should be improved in future training implementations. The time commitment of the training sessions is a major challenge. As for the technological support, some teachers confirm that it could be more structured and consistent to fully satisfy their needs. Similarly, the pedagogical adaptation part is quite good, but there is also a shortcoming on which some teachers agree. They say that they feel lost when integrating them into the classroom with younger pupils. Similarly, they identify some difficulties, such as the diversity of needs in the classroom, but suggest reducing ratios and support from other teachers as possible solutions.

Finally, Figure 6 (in next page) shows a summary of all the interviews. The codes represent the relation of the implementation of maker activities after training. This application is characterised by its flexibility, allowing it to be adapted to different contexts and educational levels. Evaluation is something that worries teachers to some extent, although, after the training process, they have been able to gradually improve this point. Teachers also consider the space to be important and are very enthusiastic about the makerspaces that have been created in each of the schools. These are spaces where interdisciplinary work can be carried out with different subjects such as STEAM. Teachers emphasise not only the technical skills acquired, but also the importance of teaching values such as sustainability and DIY (Do It Yourself). In these makerspaces, they confirm that after the training period they are able to include activities for all the pupils:

“They’re working better now; you don’t see anyone being bored. Everybody’s doing something and that’s because we’ve changed the methodology. We had children who weren’t engaged in what was being done in class.’’ (Teacher 5, School 2)

At the same time, they try to promote equity among pupils, as girls feel that they can also pursue technological careers. Finally, they also stress the importance of having a member of staff in charge of the makerspace to guide and support the pupils in carrying out projects. In conclusion, teachers are satisfied with training and affirm that a combination of technical and pedagogical elements is needed for a good implementation. Through these practical spaces and with an interdisciplinary approach, teachers aim to transform education into a creative process adapted to the current educational needs.

FIGURE 6. Synergy of skills and perspectives of the teacher training

4. DISCUSSION

Despite the lack of teacher training in maker education within schools (Gutiérrez-Esteban & Jaramillo-Sánchez, 2022), this training process, developed in the context of primary and secondary schools in Catalonia, highlights the variety of content addressed to teachers during implementation. The responses reflect a clear trend of satisfaction, especially in relation to the support and training received, over and above the provision of material resources. These findings are in line with Forbes et al. (2021) and Torralba (2019), who highlight the importance of providing guidance to teachers during the implementation of such projects, as they often involve unusual challenges. Aligned with these findings, the present study concurs with Domínguez-González (2018), who highlights that the key to effective training is the ability to combine practical knowledge, skills, experiences, and competences of the participants. This fact reinforces the idea that a balance between theory and practice is essential for the successful implementation of educational maker projects.

Another benefit of teacher training is its personalised approach, allowing to adapt to the specific needs of teachers. In addition, key aspects such as the design, implementation and evaluation of maker activities are explored in depth, an approach that is consistent with that of some authors (Rodríguez-Calderón y Belmonte-Izquierdo, 2021; Forbes et al., 2021). In addition, the trainer provides concrete tools that are applicable to each teacher’s context, in line with Rodríguez-Calderón y Belmonte-Izquierdo (2021).

An important aspect of training has been learning through error. From the first sessions there was some reluctance on the part of the teachers to accept change, especially when faced with the idea of adopting new methodologies. However, as the sessions progressed, a gradual change in their perspective was observed, with a more open and receptive attitude to the learning process. Situations of error were used as an opportunity to manage frustration, helping teachers to develop this key skill, which they could then transfer to their classrooms. This approach is in line with the theories of Torralba (2019), who advocates creating without fear of error, and Hughes et al. (2021), who highlight the importance of fostering positive attitudes towards error in a safe environment for making mistakes. Furthermore, training confirmed the findings of Domínguez-González (2018), who suggests that although initial frustration may be perceived as a barrier, with the right support it becomes a motivational driver. In a complementary way, Blikstein’s (2014) ideas on tolerance and frustration are also confirmed. It has been observed in this research that they promote greater perseverance and teaches them how to work in heterogeneous teams. Furthermore, promoting contextualised problem-solving in daily challenges has been observed as a positive approach to optimizing the use of available resources. This approach reinforces the relationship between maker education and the practical connection with the environment, as noted by Spieler et al. (2022) and Martin et al. (2020), who highlight the inherent link between this educational approach, the efficient management of resources and the solution of everyday problems. Domínguez-González et al. (2018) also agree in that while implementing maker education, work is done collaboratively through problem-solving, as promoted during training. Similarly, to foster problem-solving, participants were tasked with creating or repairing an artefact artifact. This approach is in line with the theory of Blikstein (2014), who stated that the teaching-learning process involves the creation and modification of artefacts into end products to respond to a problem related to the environment of the educational community in which the project is developed.

An aspect highlighted by both, teachers and observers, is that one of the main points of the training focuses on how to stimulate pupils’ interest. In this regard, it is observed that when teachers apply what they have learned, pupils demonstrate a high level of engagement and maintain sustained interest in the activities, which supports the theories of various authors (Martínez-Moreno et al., 2021; Hwang, 2017; Lin et al., 2021). This pupils’ engagement is fundamental to the success of maker education. Furthermore, much of the knowledge during training was covered through practical experiences and activities, which is in line with Domínguez-Gonzalez et al. (2018) theory, stating that learning by doing generates meaningful knowledge. This hands-on approach not only enhances the learning process but also fosters a deeper connection between students and the subject matter (Nikou, 2024).

The difficulties pointed out by Domínguez-González (2018), who mentions that public school teachers often face a lack of financial resources to acquire digital rapid prototyping tools, are not reflected in our study. The participating teachers expressed a high level of satisfaction, as all the schools involved were public and the project was supported with European funding. This financial support ensured the provision of the necessary resources and tools, allowing teachers to fully focus on learning and implementing maker education without the usual constraints of lack of technological equipment.

In this study, it is observed that there is a lack of training related to the adaptation of activities for pupils with special educational needs (SEN). Martínez and Bielous (2017) emphasize that, in order to be inclusive and effective, maker education trainings must take into account the specificities of each pupil. At the same time, Gutiérrez-Esteban and Jaramillo-Sánchez (2022) highlight the benefits for pupils with disabilities, as they foster the development of skills that would be difficult to achieve through less hands-on and practical methodologies.This aspect represents an essential area of improvement for future educational initiatives.

Despite this shortcoming, the importance of considering the socio-emotional aspects of pupils in their different contexts has been promoted among teachers. In this sense, we agree with Carrasco and Valls (2023), who emphasise that the teacher should act as a facilitator of learning, also playing the role of a reference and support figure during the educational intervention, as well as a companion in the socio-emotional sphere.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the development of training for primary school teachers to implement Maker Education in the classroom. Overall, once the training program was completed, the interviews and observations confirmed that the centres received good support. It is important to note that training itself has been positively evaluated, partly due to the use of a framework (Marshall & Harron, 2018) that provides clear guidance on the content to be covered. Although not all of the elements in the rubric were covered to the same depth, they were all addressed, some to a greater extent than others. We recommend that frameworks continue to be used as a support in future studies, as they provide a coherent and facilitating structure for the design and delivery of training programs.

Indeed, some contents are treated in a transversal way in several sessions, such as maintaining the pupils’ interest or linking the activities carried out in class with the pupils’ daily life. There are also other aspects, such as designing or evaluating maker activities in the classroom, that are not cross-curricular, but are dealt with in depth in specific sessions. This combination provides a balanced approach to teacher training, as it allows for in-depth exploration of key aspects, while continuously reinforcing essential content that needs to be considered in most sessions of maker activities.

Teachers with more experience in maker education find it easier to link activities to pupils’ everyday lives. However, their prior knowledge can also present challenges, as established practices may need to be re-thought, which can be complex due to the inertia of existing trends. On the other hand, teachers with less experience are more open to incorporating new ideas, as they don’t have to unlearn previous practices. Parallel to that, it is essential that teacher training programs include guidance on adapting Maker Education activities to meet the needs of pupils with SEN. Furthermore, it is vital for teaching staff to develop confidence and proficiency in using technological tools effectively. This will make maker activities easy to use, useful, satisfying, enjoyable, and ultimately motivating for students (Nikou, 2024).

This study contributes to the field of maker education by identifying key points for teacher training, in line with current needs around the lack of information on how to effectively prepare teachers (Ioannou & Gravel, 2025; Stevenson et al., 2019). These findings highlight the importance of further developing training models to support teachers. Ultimately, it is beneficial to also consider hands-on activities that provide a more holistic perspective for both, teachers and pupils. Maker education represents an opportunity for the holistic development of pupils, in line with the demands and challenges of the 21st century.

5.1. Limitations and future lines of research

As a limitation of this study, the analysis has been confined to two schools due to difficulties in obtaining permissions, which limits the generalisability of the results. In addition, the teachers interviewed are part of the team behind the educational project, so the inclusion of other teachers’ perspectives could enrich the findings.

6. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Oriol Nadal, Mireia Usart, Cristina Valls; Data curation: Mireia Usart; Formal analysis: Cristina Valls; Funding acquisition: Mireia Usart, Cristina Valls; Investigation: Oriol Nadal, Mireia Usart, Cristina Valls; Methodology: Mireia Usart; Project administration: Mireia Usart, Cristina Valls; Software: Oriol Nadal; Resources: Oriol Nadal; Supervision: Mireia Usart, Cristina Valls; Validation: Oriol Nadal; Visualization: Oriol Nadal; Writing – original draft: Oriol Nadal; Writing – review & editing: Oriol Nadal, Mireia Usart, Cristina Valls.

7. fUNDING

Two authors are teachers within the Serra Hunter program.

Funding: The research work presented in this paper is the outcome of a project funded by both institutions under the collaboration framework agreement between the Diputació de Tarragona and the Universitat Rovira i Virgili for the period 2020–2023, year 2025, with the reference number 2023/07: “Training of pre-doctoral research staff”.

8. AnneXES

- Nadal, O., Usart, M., Valls, C. (2025), “Questions for Teacher Interviews on the Maker Project”, https://doi.org/10.34810/data1970, CORA.Repositori de Dades de Recerca, DRAFT VERSION

- Nadal, O., Usart, M., Valls, C. (2025), “Maker training evaluation rubric”, https://doi.org/10.34810/data1968, CORA.Repositori de Dades de Recerca, DRAFT VERSION

9. referencEs

Alekh, V., Susmitha, V., Vennila, V., Muraleedharan, A., Nair, R., Alkoyak-Yildiz, M., Akshay, N., & Bhavani, R. R. (2018). Aim for the sky: Fostering a Constructionist learning environment for teaching maker skills to children in India. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Part F1377, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1145/3213818.3213830

Bevan, B. (2017). The promise and the promises of making in science education. Studies in Science Education, 53(1), 75-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2016.1275380

Bautista-Vallejo, J. M., y Hernández-Carrera, R. M. (2020). Aprendizaje basado en el modelo STEM y la clave de la metacognición. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 6(1), 14-25. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2020.v6i1.6719

Bisquerra Alzina, R. (coord.) (2009). Metodología de la Investigación Educativa. Editorial la Muralla.

Blikstein, P. (2014). Digital Fabrication and ‘Making’ in Education. En J. Walter-Herrmann & C. Büching (Eds.), FabLab (pp. 203–222). Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839423820.203

Carrasco, C. H., & Valls-Bautista, C. (2023). Educació maker a les escoles: característiques del procés d’implementació. Universitas Tarraconensis. Revista de Ciències de l’Educació, (1), 9-29. https://doi.org/10.17345/ute.2022.2.3208

Domínguez-González, M., Mocencahua-Mora, D. y Cuevas-Salazar, O. (2018). Taller Docente Maker para la enseñanza de ciencia y tecnología en la educación secundaria. En C. Monte de Oca, J. García y E. Orozco (Eds.), Innovación, Tecnología y Liderazgo en los entornos educativos (pp. 169-179). Humboldt International University.

Fleming, L. (2015). Worlds of making: Best practices for establishing a makerspace for your school. Corwin.

Forbes, A., Falloon, G., Stevenson, M., Hatzigianni, M., & Bower, M. (2021). An Analysis of the Nature of Young Students’ STEM Learning in 3D Technology-Enhanced Makerspaces. EARLY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT, 32(1, SI), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1781325

Gutiérrez-Esteban, P., y Sánchez, G. J. (2022). Por una Educación Maker Inclusiva. Revisión de la Literatura (2016-2021), Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación,(64), 201-234. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.91256

Herrera, J. (2017). La investigación cualitativa. https://juanherrera.files.wordpress.com/2008/05/investigacion-cualitativa.pdf

Hughes, J., Fridman, L., & Robb, J. (2018). Exploring maker cultures and pedagogies to bridge the gaps for students with special needs. In Transforming our World Through Design, Diversity and Education (pp. 393-400). IOS Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-923-2-393

Hughes, J. M., & Kumpulainen, K. (2021, November). Maker education: Opportunities and challenges. In Frontiers in education, 6, e798094. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.798094

Hwang, J. P. (2017). Maker movement influence on students’ learning motivation and learning achievement–a learning style perspective. In Emerging Technologies for Education: Second International Symposium, SETE 2017, Held in Conjunction with ICWL 2017, Cape Town, South Africa, September 20–22, 2017, Revised Selected Papers 2 (pp. 456-462). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71084-6_53

Ioannou, A., & Gravel, B. E. (2024). Trends, tensions, and futures of maker education research: a 2025 vision for STEM+ disciplinary and transdisciplinary spaces for learning through making. Educational technology research and development, 72(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10334-w

Jia, Y., Zhou, B., & Zheng, X. (2021). A Curriculum Integrating STEAM and Maker Education Promotes Pupils’ Learning Motivation, Self-Efficacy, and Interdisciplinary Knowledge Acquisition. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.725525

Lee, C. E., Samuel, N., Israel, M., Arnett, H., Bievenue, L., Ginger, J., & Perry, M. (2020, April). Understanding instructional challenges and approaches to including middle school students with disabilities in makerspace activities: A cross-case analysis. In Proceedings of the FabLearn 2020-9th Annual Conference on Maker Education (pp. 26-33). https://doi.org/10.1145/3386201.3386208

Lin, Y. H., Lin, H. C. K., & Liu, H. L. (2021, November). Using STEAM-6E model in AR/VR maker education teaching activities to improve high school students’ learning motivation and learning activity satisfaction. In Y-M. Huang, C-F. Lai & T. Tocha (Eds.), International Conference on Innovative Technologies and Learning (pp. 111-118). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91540-7_13

Litts, B. K., Widman, S. A., Lui, D. A., Walker, J. T., & Kafai, Y. B. (2019). A Maker Studio Model for High School Classrooms: The Nature and Role of Critique in an Electronic Textiles Design Project. Teachers College Record, 121(9), 1-34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811912100906

Lock, J., Gill, D., Kennedy, T., Piper, S., & Powell, A. (2020). Fostering learning through making: Perspectives from the international maker education network. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education/Revue internationale du e-learning et la formation à distance, 35(1).

Lopezosa, C., Codina, L., y Freixa Font, P. (2022). ATLAS. ti para entrevistas semiestructuradas: guía de uso para un análisis cualitativo eficaz. DigiDoc Research Group (Pompeu Fabra University), DigiDoc Reports, 2022 RTI11/2022

Lundberg, M., & Rasmussen, J. (2018). Foundational Principles and Practices to Consider in Assessing Maker Education. Journal of Educational Technology, 14(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.26634/jet.14.4.13975

Lu, X., & Zheng, X. (2025). Efficacy of maker-centered learning method on K-12 students’ learning outcomes. Educational Technology & Society, 28(1), 60-77. https://doi.org/10.30191/ETS.202501_28(1).RP04

Marshall, J. A., & Harron, J. R. (2018). Making learners: A framework for evaluating making in STEM education. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1749

Martínez Moreno, J., Santos, P., & Hernandez-Leo, D. (2021). Maker Education in Primary Education: Changes in Students’ Maker-Mindset and Gender Differences. In M. Alier & D. Fonseda (Eds.), ACM International Conference Proceeding Series (pp. 120–125). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3486011.3486431

Martínez, Y. M. M., y Bielous, G. D. (2017). El movimiento Maker y los procesos de generación, transferencia y uso del conocimiento. Entreciencias: Diálogos en la sociedad del conocimiento, 5(15). https://doi.org/10.22201/enesl.20078064e.2017.15.62588

Martin, W. B., Yu, J., Wei, X., Vidiksis, R., Patten, K. K., & Riccio, A. (2020). Promoting Science, Technology, and Engineering Self-Efficacy and Knowledge for All With an Autism Inclusion Maker Program. Frontiers in Education, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00075

Morante, M. D. C. F., López, B. C., y Otero, L. C. (2020). Capacitar y motivar a las niñas para su participación futura en el sector TIC: Propuesta de cinco países. Innoeduca: international journal of technology and educational innovation, 6(2), 115-127. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2020.v6i2.6256

Morales, J., Cabrera, A. L. R., Cantabrana, J. L. L., y Cervera, M. G. (2020). ¿Cuánto importa la competencia digital docente?: Análisis de los programas de formación inicial docente en Uruguay. Innoeduca: international journal of technology and educational innovation, 6(2), 128-140. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2020.v6i2.5601

Nadal, O., Rodríguez, M. U., & Bautista, C. V. (2024). Avaluació de l’acompanyament docent en projectes maker: Desenvolupament i aplicació d’una rúbrica. In Transformació Digital de l’Educació a l’Era de la Intel· ligència Artificial: Una Revolució Imparable (pp. 213-222). Dykinson. https://doi.org/10.14679/3551

Nikou, S. A. (2024). Student motivation and engagement in maker activities under the lens of the Activity Theory: A case study in a primary school. Journal of Computers in Education, 11(2), 347-365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-023-00258-y

Otero, N., & Blikstein, P. (2016, June). Barcino, creation of a cross-disciplinary city. In J.C. Read & P. Stenton (Eds.), Proceedings of the The 15th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (pp. 694-700). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2930674.2935996

Quintana-Ordorika, A., Camino-Esturo, E., Portillo-Berasaluce, J., & Garay-Ruiz, U. (2024). Integrating the maker pedagogical approach in teacher training: The acceptance level and motivational attitudes. Education and Information Technologies, 29(1), 815-841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12293-4

Rodríguez-Calderón, R., y Belmonte-Izquierdo, R. (2021). Educational platform for the development of projects using Internet of Things. IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologías del Aprendizaje, 16(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1109/RITA.2021.3122971

Ruiz Ortiz, I. (2023). The Robotics in the Area of Mathematics in Primary Education. A Systematic Review. Edutec, Revista Electrónica De Tecnología Educativa, (84), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2023.84.2889

Sánchez-Caballe, A., Gisbert-Cervera, M., & Esteve-Mon, F. (2020). The digital competence of university students: a systematic literature review. Aloma. Revista De Psicologia I Ciènces De L’educació, 38(1), 63-74. https://doi.org/10.51698/aloma.2020.38.1.63-74

Santos, A. R. P., Pérez-Garcias, A., y Mesquida, A. D. (2023). Formación en competencia digital docente: validación funcional del modelo TEP. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 9(1), 39-52. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2023.v9i1.15191

Shively, K., Stith, K., & DaVia Rubenstein, L. (2021). Ideation to implementation: A 4-year exploration of innovating education through maker pedagogy. The Journal of Educational Research, 114(2), 155-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2021.1872472

Silva, I. R., Vacas, E. A., & Solanas, O. N. (2024). Programa d’innovació FAIG: fent per aprendre, imaginant globalment Programa de innovación FAIG: haciendo para aprender, imaginando globalmente FAIG innovation program: learning by doing, imagining. Revista UTE Teaching & Technology (Universitas Tarraconensis), (3), e4021. https://doi.org/10.17345/ute.2024.4021

Spieler, B., Schifferle, T. M., & Dahinden, M. (2022). Exploring Making in Schools: A Maker-Framework for Teachers in K12. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. https://doi.org/10.1145/3535227.3535234

Stevenson, M., Bower, M., Falloon, G., & Forbes Anne and Hatzigianni, M. (2019). By design: Professional learning ecologies to develop primary school teachers’ makerspaces pedagogical capabilities. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(3), 1260–1274. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12743

Tomczyk, L., Mascia, M. L., Gierszewski, D., & Walker, C. (2023). Barriers to digital inclusion among older people: a intergenerational reflection on the need to develop digital competences for the group with the highest level of digital exclusion. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 9(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2023.v9i1.16433

Torralba, J. (2019). A mixed-methods approach to investigating proportional reasoning understanding in maker-based integrative steam projects. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1145/3311890.3311901

Veldhuis, A., d’Anjou, B., Bekker, T., Garefi, I., Digkoglou, P., Safouri, G., ... & Bouros, M. (2021, June). The connected qualities of design thinking and maker education practices in early education: A narrative review. In fablearn europe/MAKEED 2021-an international conference on computing, design and making in education (pp. 1-10). https://doi.org/10.1145/3466725.3466729

Weng, X., Chiu, T. K. F., & Jong, M. S. Y. (2022). Applying Relatedness to Explain Learning Outcomes of STEM Maker Activities. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800569