Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation Vol. 11. No. 2. December 2025 - pp. 59-81 - ISSN: 2444-2925

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.112.2025.20960

An Integrative Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Intentions to Utilize Digital Tools for Instructional Purposes

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.1. INTRODUCTION

Although the integration of digital technologies within learning environments is not itself anything new, the use of these technologies increased rapidly with the COVID-19 outbreak (Pozo et al., 2024). Technological advancements have also significantly impacted upon modern teaching and learning methods, with the rapid and innovative growth of Internet technologies having led to the creation of numerous digital tools and apps, smart devices such as laptop and tablet computers, as well as the ubiquitous smartphone revolution (Ng, 2015). Consequently, scholars and practitioners have explored the various ways in which these technologies may be employed for educational purposes (Taylor et al., 2021).

Technology use in delivering instruction was already prevalent in education for many years; however, almost overnight the pandemic forced the rapid and almost universal adoption of digital tools for the enhancement of education (Paetsch & Drechsel, 2021) in that most face-to-face courses were replaced by online education, which had a profound impact on students. Pandemic distance learning required students to possess a high degree of self-regulation concerning their learning environment and to find new ways of communicating with their peers and instructors. At the same time, the novel situation offered opportunities to experience new educational applications. To learn more about the possible benefits of distance learning, this study examines how the first online semester during the pandemic contributed to pre-service teachers’ intentions to use digital learning materials in the future. Pre-service teachers enrolled in a German university (n = 348. As such, the world has witnessed a paradigm change in recent years, with contemporary students utilizing a diverse range of programs and resources to produce their assignments rather than relying on traditional tools such as pen and paper (Haleem et al., 2022). In light of the many ways digital technologies have enriched education, from facilitating student learning to fostering digital citizenship and promoting lifelong learning (Ng, 2015), it is imperative that future educators are sufficiently prepared to make effective use of these tools in the classroom. On this, Ertmer (1999) defined technology integration barriers as internal and external, with teachers’ technical and pedagogical knowledge having a significant impact on the meaningful integration of technology in education. Furthermore, Hew and Brush’s (2007) pioneering study identified barriers to technology integration, revealing that the technological knowledge and skills of teachers was a factor that affected their use of technology in the classroom.

In earlier research, Inan and Lowther (2010) revealed computer proficiency as an important determinant of teachers’ technology integration, whilst a meta-analysis by Wilson et al. (2020) revealed that courses related to technology integration enhanced preservice teachers’ technological and pedagogical knowledge. In this regard, Ottenbreit-Leftwich et al. (2018) stated that equipping preservice teachers with appropriate knowledge and experience related to technology integration may help them to overcome obstacles in their future classroom teaching. However, whilst technological knowledge and skill are considered major factors for effective technology integration, the perception toward and adoption of technology are also essential issues. The successful utilization of digital resources within educational courses therefore relies significantly on the actions of teachers (Müller & Leyer, 2023). Prior to starting teaching, the assessment of preservice teachers’ technology acceptance levels would help provide institutions with valuable information of interest to various stakeholder groups.

In order to better prepare future educators to deliver benefit from the effective use of digital learning tools in their instruction, teacher preparation programs need to provide student teachers with adequate hands-on experience with the use of digital learning resources in the classroom environment (Paetsch & Drechsel, 2021) in that most face-to-face courses were replaced by online education, which had a profound impact on students. Pandemic distance learning required students to possess a high degree of self-regulation concerning their learning environment and to find new ways of communicating with their peers and instructors. At the same time, the novel situation offered opportunities to experience new educational applications. To learn more about the possible benefits of distance learning, this study examines how the first online semester during the pandemic contributed to pre-service teachers’ intentions to use digital learning materials in the future. Pre-service teachers enrolled in a German university (n = 348. Teachers need to be leaders in technology-supported environments, hence they should adopt and utilize digital tools in their teaching practices (Sharma & Saini, 2022). For this reason, the decisions made by preservice teachers’ on their expected use of these tools require investigation, as well as the factors that could influence their decisions.

Several models exist which may be used to scrutinize technology acceptance such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1986), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1985), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al., 2003), and the Task Technology Fit Theory (TTF) (Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). Several studies have incorporated these models in the investigation of user acceptance. For example, the TAM was used in researching inservice teachers’ acceptance of technology (Hong et al., 2021; Wohlfart & Wagner, 2024), preservice teachers’ acceptance of technology (Teo et al., 2015), preservice teachers’ intentions to use Web 2.0 tools (Şimşek & Ateş, 2022), and preservice teachers’ acceptance of educational robots (Casey et al., 2021). In other studies, the TPB was used in researching preservice teachers’ adoption of technology-enabled learning (Hou et al., 2022) and preservice teachers’ intentions to use technology during their teaching practices (Habibi et al., 2023; Yusop et al., 2021). Additionally, Dahri et al. (2024) employed TTF to investigate factors related to mobile-based teacher training.

Additionally, the adoption of digital tools in teaching has been studied. For example, Sharma and Saini (2022) used the TAM to explore higher education instructors’ intentions to continue integrating electronic resources into instructional practices, and Polly et al. (2022) examined how inservice and preservice teachers perceived digital technology in terms of its importance, usefulness, competency, and interest. During the COVID-19 pandemic, research was conducted to reveal instructors’ inclinations toward teaching online (Aivazidi et al., 2021; Sangeeta & Tandon, 2020), whilst following the pandemic, similar research was conducted separately with inservice (Khong et al., 2022) and preservice teachers (Wang, 2022). The research to date in this area has tended to focus mostly on teachers as participants and the investigation of their technology adoption behaviors. As the success and efficacy of digital technology usage attempts may depend on users’ technology acceptance (Sharma & Saini, 2022), it would be reasonable to determine predictors of digital tools usage during teacher education. Preservice teachers’ intentions regarding the use of digital tools in their future professional teaching career may help serve as a predictor of their actual usage once employed as teachers in the classroom. Thus, the intention of prospective teachers to benefit from digital tools in the classroom is considered a crucial subject to explore.

The current study favored use of the TAM, TPB, and TTF models, which may be used to predict a teacher’s propensity to utilize technology in their future teaching. The TAM was selected for the current study since it is considered a strong model for learning technologies (Granić & Marangunić, 2019) and is employed mainly in research on technology acceptance. However, one important issue related to the TAM is that it neglects to account for subjective beliefs or perceived behavioral control, wherein abilities, resources, and opportunities are deemed essential for forecasting the intention to utilize a technology (King & He, 2006; Mathieson, 1991). Given this limitation, the TPB was considered for the current research since it is also known as a successful theory for the prediction of user intention based on essential variables such as subjective norms and perceived behavioral control. Compared with the TAM, the TPB is considered more independent of content, and its constructs are therefore applicable to any behavior (Ajzen, 2020). Lastly, given the plethora of digital tools available for instructional purposes, it is considered essential to understand their various characteristics and capabilities, as well as their alignment with users’ goals and intended objectives (Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). Consequently, TTF was also integrated into the scope of the current investigation.

According to the literature, there have been various research studies regarding inservice teachers’ or preservice teachers’ adoption of technology. The current study presents one of the first attempts to combine three models to explore digital tools acceptance in the context of preservice teachers. The combining of these three models is expected to shed additional light on preservice teachers’ adoption of digital learning tools for their future instructional practices compared to research reliant upon only a single model. Preservice teachers can gain experience of using digital educational materials and are generally encouraged to utilize technology in their teaching and learning as part of their teacher education (Paetsch & Drechsel, 2021). Thus, prior to the start of their professional teaching career, the use of an integrated model may help to identify both positive and negative factors related to the use of digital tools in teaching. Moreover, the results of the current study are expected to help instructors to use the most appropriate digital tools in the education of preservice teachers.

In light of the aforementioned literature and prior research, the current study examined preservice teachers’ intentions to embrace digital tools for instructional practices through the TAM, TPB, and TTF. Regarding the current study’s significance, the findings are expected to expand upon existing knowledge of the factors driving preservice teachers’ intentions to benefit from digital learning tools by uncovering potential connections between variables. As such, the research outcomes are expected to offer implications pertinent to both teaching practitioners and educational managers.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Digital Learning Tools

Digital technology has significantly impacted the field of education (Wang et al., 2024). The term “digital technologies” includes both software and hardware such as desktop computers, mobile devices, recording devices, smartboards, Web 2.0 tools, and multimedia tools (Ng, 2015). Multiple variants of these technological advancements have spawned new delivery and teaching methods such as online learning and blended learning (Khong et al., 2022)the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19 as well as significantly changing traditional face-to-face classroom teaching methods (Müller & Leyer, 2023). Incorporating these instruments into pedagogical processes has resulted in positive outcomes for students such as increased engagement and motivational development required for 21st-century skills (Taylor et al., 2021). Timotheou et al. (2023) conducted a detailed evaluation of research that examined the effects of digital technology on education. The research findings revealed that the utilization of digital technologies facilitated students’ learning in particular academic disciplines and fostered the growth of their skill sets in areas such as creativity, problem solving, and computational thinking. Additionally, digital technologies have been shown to improve students’ motivation, attitude, and academic confidence.

Several countries and international organizations have developed standards and requirements for educators in the 21st century, including Turkey’s Ministry of National Education (2017), the International Society for Technology in Education (2017), and the European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (European Commission, 2017). These various standards incorporate the design, development, and implementation of effective learning processes and the integration of appropriate technologies within learning environments. Regarding effective technology integration, teachers require both appropriate knowledge and strong beliefs (Ertmer & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010). As such, future educators must acquire proficiency in the utilization of these resources and possess a favorable view of technology integration in the classroom by effectively learning to employ digital tools in conjunction with sound pedagogical practices. In this regard, among the many types of digital technologies currently available, the following were selected within the scope of the current study (Bower, 2016; Bower & Torrington, 2020):

- Online repository tools can be used to store and access instructional documents, presentations, videos, and other electronic files. These tools usually offer organized folder systems where permissions can be set to control who can access and edit files or folders.

- Learning management systems (LMS) enable teachers to manage their course activities and students’ work. Additionally, students can also access their course materials, course activities, and assignments, as well as monitor their own progress. LMS functionality also enables teachers to create assignments and tests, monitor student progress, report and record statistics, and to supervise course administration.

- Online meeting platforms can be used to conduct virtual meetings and classes, with features including video, audio, and chat utilized to facilitate and enhance the instructional process and acquisition of knowledge. Additionally, users can see and hear each other as well as benefit from synchronous features such as screen sharing.

- Presentation tools enable teachers to develop interactive course presentations where they can add text, pictures, tables, graphics, music, and video into slides to create more effective teaching.

- Video tools enable teachers to produce interactive videos for instruction and learning with features that include both video and still images, transitions between elements, and other editing options that help create almost professional standard audiovisual materials.

- Animation platforms enable teachers to create compelling animations to support student learning. These platforms offer templates, drag-drop functionality, and interactive elements as well as the use of multimedia content.

- Infographics, concept maps, and poster tools can be utilized to create visual materials that combine text, charts, and images or icons to promote concept organization, knowledge summarization, and for the visualization of ideas.

- Assessment platforms can be used to create course assessment material and to implement digital exams or quizzes, enabling teachers to create online tests with varied question types, automated feedback and grading functions, and also performance monitoring.

Other emerging tools worthy of note are coding tools, and the use of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) applications which can further help teachers to create a more meaningful and effective teaching and learning experience.

2.2. Teacher Education in Turkey

In Turkey, preservice teachers are required to complete various undergraduate courses based on field knowledge, professional teaching knowledge, general knowledge, as well as various elective courses (Yükseköğretim Kurulu [Turkish Higher Education Council], 2018). Each area includes courses that help these future educators to develop skills in their chosen subject area (e.g., mathematics education, preschool education). One of the professional teaching knowledge courses is on instructional technology, which includes topics such as the conceptual background of instructional technology, instructional materials design, message design principles, instructional technology contemporary tools and approaches, and digital teaching tools. Overall, the course helps preservice teachers to gain both the required academic knowledge and practical expertise in applying various instructional technologies in their teaching practices.

Turkey’s Ministry of National Education (2017) has also created Competencies for the Teaching Profession which comprise three main areas: professional knowledge and skills, attitudes, and values. According to the professional skill competency area, teachers should be able to utilize technology and materials within their teaching practices (Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı [Turkish Ministry of National Education], 2017). The aforementioned instructional technology course is therefore integral to equipping preservice teachers with the necessary knowledge and skills related to technology integration. Historically, the Turkish Ministry of National Education has conducted a number of technology integration initiatives, with the Movement of Enhancing Opportunities and Improving Technology project (known by its Turkish acronym, FATIH) having been in play since 2010 (Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı [Turkish Ministry of National Education], 2010). The project provides both hardware and software infrastructure to classrooms nationwide, as well as focusing on the creation of instructional e-content, integrating information and communication technologies (ICTs) into curricula, the organization of inservice teacher training, and encouraging safe Internet usage by both teachers and students. The FATIH project aims that preservice teachers be prepared to effectively utilize ICTs in education so that they can maximize the benefits for students prior to starting their professional teaching careers.

2.3. Hypothesized Model Development

Regarding technology use in learning environments, supplying ICT tools alone to schools holds no guarantee that teachers and students will benefit from the latest technology-enhanced teaching strategies as opposed to conventional instructional methods. Various factors are known to affect teachers’ adoption and use of technology in their teaching practices (Ursavaş et al., 2019). According to a longitudinal study conducted by Pozo et al. (2024), teachers have generally used digital tools more following the pandemic than they did previously, inferring that teachers accept and adopt such tools after long-term usage (in this case, from emergency online teaching during the pandemic). In an earlier study, Li et al. (2016) explored preservice teachers’ acceptance of technology through two models, the TPB and TAM, and indicated that self-efficacy, attitude, and perceived ease of use were significant predictors. Research by Mei et al. (2018) identified factors affecting preservice teachers’ adoption of Web 2.0 tools for foreign language teaching, in which perceived usefulness, facilitating conditions, and technological pedagogical content knowledge influenced intention. Similar research includes a study by Lee et al. (2022), who explored foreign language teachers’ adoption of online teaching by combining the TAM and TTF models; Wong et al. (2013) who used the UTAUT model to explore predictors of whiteboard usage by preservice teachers; and Tang et al. (2021) who integrated the TPB, TAM, and UTAUT models plus individual factors connected to a mobile technology enhanced teaching platform used by university instructors. As teachers’ technology adoption and utilization is a multifaceted behavior (Ursavaş et al., 2019), it is considered well worth examining this behavior using more than one acceptance model. As such, understanding the predictors of this behavior in terms of preservice teachers may help to better guide the design of teacher education programs to ensure newly qualified teachers can effectively use educational technology in the classroom (Anderson et al., 2011).

The literature on information systems, particularly in terms of the TAM, TPB, and TTF models, has mostly scrutinized users’ intention to utilize certain technologies based on emphasis of their acceptance or adoption of those technologies. The TAM, which is an adaption of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), focuses on predicting and explaining users’ behaviors toward technology (Davis et al., 1989) through the elements of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEU), attitude (AT), and behavioral intention (BI) (Davis et al., 1989). The TPB, which is an extension of TRA (Ajzen, 1985), is a significant and popular theory employed to explain different types of human behavior (Ajzen, 2001). According to the TPB, any human behavior can be identified according to three constructs: attitude (AT), perceived behavioral control (PBC), and subjective norms (SN) (Ajzen, 1985). The TTF model predicts an information system’s success by considering the task-technology fit; i.e., it is the characteristics of tasks and technology that impact the fit between tasks and technology (Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). Within the scope of the current study, the TAM, TPB, and TTF models are proposed as a theoretical framework to effectively assess the behavioral intention of preservice teachers to utilize digital learning tools in their instructional activities.

The TAM, which has gained significant acceptance in the area of instructional technology, was initially introduced by Davis in 1986. The model consists of four variables (PU, PEU, AT, and BI), with relationships between each of these variables: PU and AT predict BI; PEU and PU predict AT; and PEU predicts PU (Davis, 1986). PU is the level to which an individual believes that the adoption of a given system will increase their job efficiency, whereas PEU is how easy they consider the technology would be to use in practice (Davis, 1989).

In the context of digital learning tools’ adoption, Teo (2012) combined the TAM and TPB models for surveying preservice teachers to determine how they planned to utilize technology in their teaching. The study revealed that TAM variables and SN were associated with behavioral intention. Furthermore, it was concluded that favorable attitudes and perceptions regarding the usefulness of technology was a driver for preservice teachers to utilize technology. In a more recent study, Almulla (2022) researched how university instructors intended to utilize digital learning tools during the COVID-19 pandemic via an extended TAM, the results of which confirmed the main propositions of the TAM. Concerning the current study, preservice teachers’ attitudes regarding the potential benefits of incorporating digital technologies into their teaching may impact upon their inclination to utilize these resources in their future teaching practices. Utilizing digital learning tools for different instructional purposes can consequently influence their teaching behaviors and shape perceptions regarding the usefulness of digital learning tools and, as a result, they may be more likely to adopt and utilize digital tools in their future teaching careers. Previous literature has shown significant linkage between PU and BI for technology-rich learning environment acceptance (Parkman et al., 2018) and for teaching intention of Web 2.0 tools (Şimşek & Ateş, 2022). The usefulness of digital tools that preservice teachers perceive may affect their feelings toward these tools, a relationship that was validated by prior research on teachers’ intention to teach online (Bajaj et al., 2021) and technology acceptance of preservice mathematics teachers (Gurer, 2021).

Moreover, preservice teachers’ thoughts with regards to the utilization of digital tools in their future teaching will likely influence their attitudes towards and usefulness of digital tools. In other words, the difficulty or ease of using certain digital learning tools, as experienced directly by preservice teachers, may affect their feelings towards those digital tools and their belief in their usefulness. These PEU–PU and PEU–AT relationships were validated in research by Eksail and Afari (2020), Georgiou et al. (2023), and Islamoglu et al. (2021). Accordingly, the following research hypotheses were formed for the current study based on the existing published literature:

H1: Perceived usefulness of digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ intention to use these tools for instruction.

H2: Perceived ease of use of digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ attitudes toward utilizing these tools for instruction.

H3: Perceived usefulness of digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ attitudes toward utilizing these tools for instruction.

H4: Perceived ease of use of digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ perceived usefulness of these tools for instruction.

The TPB can be used in order to explain factors affecting a set of human behaviors. Accordingly, the behavioral intention of certain actions is influenced by AT, SN, and PBC (Ajzen, 1985), since AT is an underlying inclination to respond positively or negatively to a psychological construct (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010) and SN describes the perceived societal pressure to engage in an action or not to (Ajzen, 1991). As such, these constructs are considered to positively and directly affect the intention of the behavior.

Previous studies have incorporated the TPB and validated proposed relationships among its constructs in several research areas. As an example, Habibi et al. (2023) studied preservice teachers’ technology integration by combining the TPB with technological pedagogical and content knowledge, revealing that all constructs were significantly influential to behavioral intention. Teo and Tan (2012) studied the reasons behind student instructors’ embrace of technology and utilized the TPB to discover significant correlations among the constructs. In subsequent research, Teo et al. (2016) analyzed teachers’ intention to employ technology by extending the TPB. The variables considered were PU, PEU, management expectations, and technical support, and it was revealed that whilst AT and PBC increased technology integration intention, SN did not.

The current study posits that preservice teachers’ positive or negative attitudes toward digital tools can influence their behavioral intentions. Consequently, it is presumed that preservice teachers intend to utilize digital learning tools in their future teaching practices when they possess favorable attitudes toward these tools; a relationship previously validated in the literature (Müller & Leyer, 2023; Teo, 2012).

Understanding the views of preservice teachers’ social circuits might also influence their behavioral intention. In essence, the opinions of significant others such as peers, instructors, and administrators may dominate preservice teachers’ intention to utilize digital tools for instructional purposes. Research by Songkram and Osuwan (2022) on teachers’ intentions of using use digital learning materials corroborated the SN–BI connection, as well as in a study on teachers’ intention to benefit from mobile applications for science teaching by Ateş and Garzón (2022). Moreover, preservice teachers’ perceived control beliefs impact their behavioral intention, which can be explained as the behavior of using digital tools for teaching is affected by their abilities and the environmental resources available when using digital tools in their teaching. Several studies have already proven this relationship, including Hou et al. (2022) and Watson and Rockinson-Szapkiw (2021). Accordingly, the current study formulated the following hypotheses based on the existing literature:

H5: Attitudes toward utilizing digital learning tools influence preservice teachers’ intention to use these tools for instruction.

H6: Subjective norms to utilize digital learning tools influence preservice teachers’ intention to use these tools for instruction.

H7: Perceived behavioral control over utilizing digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ intention to use these tools for instruction.

The TTF model primarily emphasizes how information technology fits the specific demands of various tasks (Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). The predictors of perceived performance are utilization and task technology fit, which are functions of task characteristics and technology characteristics (Goodhue & Thompson, 1995). This model is theorized as information technology is used where the features of a certain information technology are considered a match with the users’ tasks (Lo Presti et al., 2021). The task-technology fit variable, which is defined as “the degree to which a technology assists an individual in performing his or her portfolio of tasks” (Goodhue & Thompson, 1995, p. 216), was therefore selected for use in the current study. In terms of the current research, the TTF relates to the fit between the instructional tasks that preservice teachers desire to carry out and the characteristics of the appropriate digital technologies. Thus, it can be stated that TTF perception affects the adoption of digital learning tools. If preservice teachers have a higher TTF perception, they perceive the tools as easy to use and therefore useful for their teaching, which corroborates empirical research by Pal and Patra (2021) and also Wu and Chen (2017). Therefore, the TTF variable was utilized in the current study to analyze the TAM constructs’ connections, with the following three hypotheses:

H8: Task-technology fit of digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ perceived usefulness of these tools for instruction.

H9: Task-technology fit of digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ perceived ease of using these tools.

H10: Task-technology fit of digital learning tools influences preservice teachers’ intention to use these tools for instruction.

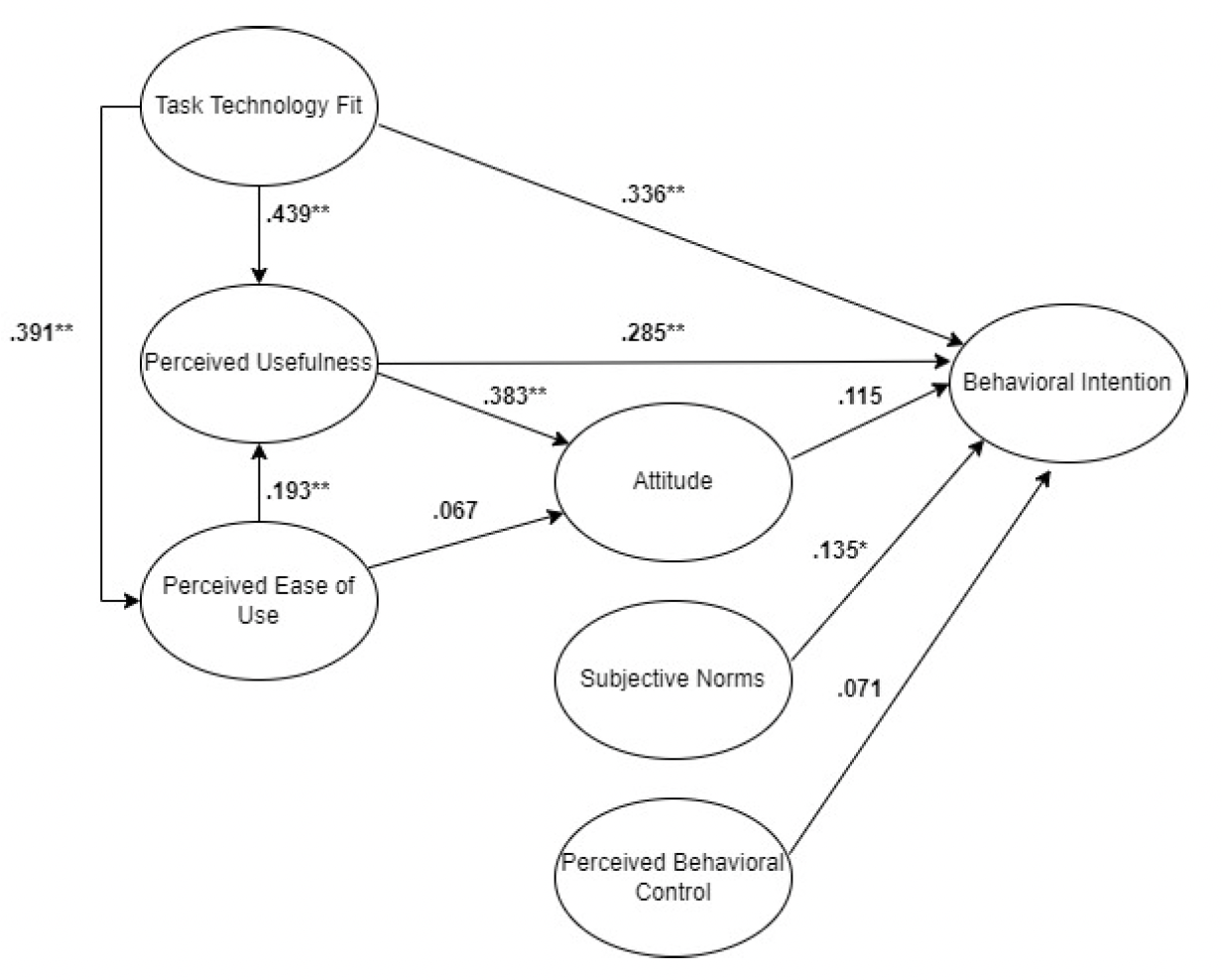

The relationships and the 10 hypotheses formulated in the current study are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Hypothesized model

3. MATERIAL AND METHOD

The study implemented a cross-sectional research design to test the devised hypothetical model. A self-report survey based on the TAM, TPB, and TTF models was administered with the aim of reaching the study’s goal.

3.1. Participants

The sample was selected using the convenience sampling method from a university located in the Aegean region of Turkey. The study group comprised 215 preservice teachers who received an instructional technology course from the university’s faculty of education as part of their undergraduate teacher training program.

Power analysis was performed using G*Power software (Faul et al., 2009) to check the minimum appropriate sample size, with an effect size of .15, error type of .05, and a power setting of .80. The minimum sample size for the study was revealed to be 92, demonstrating that the 215-participant sample was satisfactory. Prior to the survey being administered, the study’s objective was explained to the participants and they were directed to read the study’s consent form and give their consent if they wished to join the study. The participants were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point. The data collection process produced a total of 210 valid cases that were subjected to data analysis, with 81% (n = 170) of the participant preservice teachers identifying as female and 19% (n = 40) as male. The participant preservice teachers were distributed across six teaching departments, with 57 (27.1%) enrolled to the English Language Education department, 56 (26.7%) to Preschool Education, 30 (14.3%) to Guidance and Psychological Counseling, 24 (11.4%) to Science Education, 22 (10.5%) to Elementary Mathematics Education, and 21 (10.0%) to the Turkish Language Education department. The participants averaged 20.8 years old with a 2.68 standard deviation.

3.2. Data Collection Procedure

The self-report survey included questions to collect personal information on the participants’ demographics plus questions regarding theoretical constructs. Previous questionnaires from the existing literature regarding the TAM, TPB, and TTF models were first analyzed prior to creating an initial pool of survey items. Then, those items that were considered to be well suited to each construct based on the study’s purpose were selected and a 7-point, Likert-type scale established to evaluate the PU, PEU, SN, and TTF constructs with three items, while the ATT, PBC, and BI constructs were assessed with four items. The researchers then adjusted the items according to the study’s setting, with adapted items for PU (“Using digital tools improves my teaching performance”) and PEU (“Learning to use digital tools is easy”) from a study by Wu and Yu (2022), for ATT (“Using digital tools would be: (unpleasant / pleasant)”) from Taylor and Todd’s (1995) research, for SN (“People who influence my behavior think that I should use digital tools”) from Teo, Zhou, et al.’s (2019) study, for PBC (“I have the knowledge necessary to use digital tools in teaching”) from Teo, Zhou, et al. (2019), for TTF (“In my opinion digital tools’ functions are enough to help me complete my work for teaching”) from Lu and Yang (2014), and for BI (“I intend to use digital tools for teaching as often as needed”) from the study published by Baber (2021). Two researchers then independently translated each item from English to Turkish, then two specialists fluent in both languages reviewed the materials and made recommendations. Following revision of the items, a Google Forms survey was created and administered to the participant preservice teachers at the end of the teaching semester, since at that point they would be most likely to possess a working knowledge of digital teaching tools and other course-related topics.

3.3. Data Analysis

Partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS–SEM) approach was utilized to scrutinize the study’s 10 formulated hypotheses. The PLS–SEM approach was selected since the current study aimed at prediction rather than theory testing or confirmation and that the proposed model was an extension of the TAM, TPB, and TTF models created to explore key drivers of the dependent construct (Hair et al., 2011) SEM is equivalent to carrying out covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM).

Initially, the collected data were analyzed so as to identify any missing data or outliers. The analytical process was undertaken in two closely related stages, with the measurement and then the structural models. First, the model’s reliability and validity issues were calculated, and where satisfactory, the second stage tested the hypothetical relationships using SmartPLS 3.3.5 software.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Measurement Model

A reliability and validity examination was performed in order to evaluate the appropriateness of the measurement model, the results of which are presented in Table 1 (in next page).

Regarding the model’s reliability, item reliability was assessed based on their factor loadings, which should be higher than .70 according to Hair et al. (2019). The results revealed that all of the items had factor loadings that ranged between .816 and .955. Additionally, composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha values were utilized to fulfill the requirements for internal consistency reliability. Both the CR (Hair et al., 2019) and alpha values (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994) were found to be higher than the minimum acceptable value of .70. Convergent and discriminant validity was then assessed to check whether the proposed model was considered valid. Convergent validity requires that AVE values exceed .50 (Hair et al., 2019). In the current study, the AVE values ranged from .728 to .877, confirming that convergent validity was ensured. Table 2 presents the results of discriminant validity tests.

Discriminant validity values were found to be satisfactory based on the criteria that AVE value square roots should be greater than the related construct correlations (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Overall, the measurement model demonstrated satisfactory levels of reliability and validity to conduct the structural model analysis.

TABLE 1. Measurement model results

| Construct | Item | Factor loading | Composite reliability | Cronbach alpha | Average variance extracted |

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | PU1 | .928 | .955 | .930 | .877 |

| PU2 | .955 | ||||

| PU3 | .926 | ||||

| Perceived ease of use (PEU) | PEU1 | .895 | .897 | .829 | .744 |

| PEU2 | .816 | ||||

| PEU3 | .876 | ||||

| Attitude (ATT) | ATT1 | .902 | .958 | .942 | .850 |

| ATT2 | .926 | ||||

| ATT3 | .940 | ||||

| ATT4 | .920 | ||||

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | PBC1 | .918 | .961 | .945 | .859 |

| PBC2 | .935 | ||||

| PBC3 | .911 | ||||

| PBC4 | .943 | ||||

| Subjective norms (SN) | SN1 | .869 | .904 | .841 | .758 |

| SN2 | .893 | ||||

| SN3 | .850 | ||||

| Task technology fit (TTF) | TTF1 | .825 | .889 | .812 | .728 |

| TTF2 | .895 | ||||

| TTF3 | .837 | ||||

| Behavioral intention (BI) | BI1 | .892 | .947 | .925 | .817 |

TABLE 2. Discriminant validity results

| ATT | BI | PBC | PEU | PU | SN | TTF | |

| ATT | .922 | ||||||

| BI | .441 | .904 | |||||

| PBC | .380 | .459 | .927 | ||||

| PEU | .207 | .379 | .637 | .863 | |||

| PU | .408 | .609 | .378 | .364 | .937 | ||

| SN | .337 | .536 | .472 | .415 | .577 | .871 | |

| TTF | .409 | .632 | .515 | .391 | .514 | .488 | .853 |

| (diagonal values = square root of AVE; off-diagonal values = correlations of paired constructs) | |||||||

4.2. Structural Model

Associations between the proposed model’s components were tested by way of structural model analysis. First, the collinearity issue was measured according to Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values among the model’s constructs. The measured VIF values were found to be lower than the threshold value of 5, indicating that no multicollinearity problem was detectable. The bootstrapping resampling technique was then employed with 5,000 subsamples in order to determine whether or not the path values of the links and the t values for each hypothesis were significant. The model’s prediction accuracy was then confirmed by R2. The outcomes of testing the study’s 10 hypotheses are both illustrated in Figure 2 and also reported in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Results of hypotheses testing

| Hypothesis | Path | VIF | β | t | p | Supported? |

| H1 | PU BI | 1.748 | .285 | 3.415 | .001 | Yes |

| H2 | PEU ATT | 1.153 | .067 | 1.019 | .308 | No |

| H3 | PU ATT | 1.153 | .383 | 6.176 | .000 | Yes |

| H4 | PEU PU | 1.180 | .193 | 2.619 | .009 | Yes |

| H5 | ATT BI | 1.329 | .115 | 1.869 | .062 | No |

| H6 | SN BI | 1.735 | .135 | 2.168 | .030 | Yes |

| H7 | PBC BI | 1.538 | .071 | 1.006 | .315 | No |

| H8 | TTF PU | 1.180 | .439 | 6.457 | .000 | Yes |

| H9 | TTF PEU | 1.000 | .391 | 6.811 | .000 | Yes |

| H10 | TTF BI | 1.711 | .336 | 4.598 | .000 | Yes |

The results indicated that seven of the 10 hypotheses were accepted based on the structural model analysis.

For hypotheses of the TAM model, the perceived usefulness (PU) construct was shown to influence behavioral intention (BI) to use digital learning tools (β = .285, p < .001) and attitude (ATT) towards digital tools (β = .383, p < .001), whilst the perceived ease of use (PEU) construct predicted perceived usefulness (PU) of digital tools (β = .193, p < .01). In contrast, perceived ease of use (PEU) did not significantly affect attitude (ATT) towards digital tools (β = .067, p > .05). Thus, hypotheses H1, H3, and H4 were accepted, while H2 was not supported.

For the TPB model’s hypotheses, subjective norms (SN) significantly predicted behavioral intention (BI) to use digital learning tools (β = .135, p < .05), whereas attitude (ATT, β = .115, p > .05) and perceived behavioral control (PBC, β = .071, p > .05) exhibited no substantial influence on behavioral intention (BI). Therefore, hypothesis H6 was supported, while both H5 and H7 were rejected.

For the TTF model, a significant effect was revealed on perceived usefulness (PU, β = .439, p < .001), perceived ease of use (PEU, β = .391, p < .001), and behavioral intention (BI, β = .336, p < .001). Thus, hypotheses H8, H9, and H10 were all accepted.

The overall variance for the intention to use digital learning tools was 52%, suggesting that the proposed model was moderate in predicting the dependent variable (Chin, 1998).

FIGURE 2. Structural model

* p<.05, ** p<.01

5. DISCUSSION

The study’s results showed that the hypotheses for the TAM and TPB models were partially confirmed, whilst relationships regarding TTF were fully supported in the proposed model. It can therefore be said that the research model had good explanatory power to understand preservice teachers’ acceptance behaviors.

The study proved that the usefulness perception of digital tools significantly predicted preservice teachers’ behavioral intentions to use digital tools in their future teaching practices. This result is consistent with research by Şimşek and Ateş (2022) and Teo, Sang, et al. (2019) on the acceptability of Web 2.0 tools for use in the classroom. This finding points to preservice teachers viewing digital tools as beneficial in classroom instruction and that their use helps to improve their teaching performance through their having received both theoretical and practical knowledge of digital tools and other related issues. It is suggested that this belief is what drives preservice teachers to utilize digital instruments in their future classroom instruction. As a result, it can be stated that perceived usefulness influences the willingness to use these digital tools. Additionally, perceived usefulness was shown to significantly influence attitude, a finding also supported by previous studies in the literature (Eksail & Afari, 2020; Georgiou et al., 2023; Gurer, 2021). Considering this relationship, the perceived benefits that digital tools offer may shape preservice teachers’ feelings towards the use of such tools. Consistent with prior research on this, the current study found that the preservice teachers’ impressions regarding the easiness of using digital tools had a significant impact on their perceptions regarding the tools’ usefulness (Almulla, 2022; Taylor et al., 2021). On the other hand, the perceived ease of using these digital tools did not influence their attitude. Although this result was contrary to that of previous studies by Almulla (2022) and Davis (1989), other research by Luik and Taimalu (2021) and Teo et al. (2018) supported it.

In the current study, the participant preservice teachers were experienced in the use of these digital tools; for example, how to log in, the functions of various menu elements, and how to develop instructional material. Thus, it can said that the preservice teachers’ comfort level in the use of the digital tools may relate to their perception of their usefulness. On the other hand, if the preservice teachers perceived the digital tools to be easy or difficult to use, their feelings about these tools (i.e., their attitude) would not increase or decrease. Instead, the preservice teachers may have considered that digital tools that were easy to use might be seen as useful technology to utilize in their future teaching. To conclude, the assumptions regarding the TAM were partially supported in the current research context.

According to the proposed model, subjective norms were found to be a significant indicator of behavioral intention among the TPB variables, whilst the constructs of attitude and perceived behavioral control were not. Concerning the context of the current study, the participant preservice teachers each have their own social network, consisting primarily of their peers and instructors, and these networks may effectively explain the preservice teachers’ plans to utilize digital tools for instructional purposes. Previous research has shown this to be the case; for example, Kreijns et al. (2013) discovered that teachers’ subjective norms affected their intention to use digital learning materials, whilst Songkram and Osuwan (2022) found that teachers’ behavioral intention to use digital learning platforms was positively correlated with their subjective norms during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, preservice teachers’ control perceptions over digital learning tools were not found to influence their behavioral intentions in the current study. In terms of the prior literature, this finding supports the results reported by Teo and Lee (2010) and also Teo and van Schaik (2012), but contradictory to those of Habibi et al. (2023) and Hou et al. (2022). As Ajzen (1991) put forward, perceived behavioral control (PBC) has an association with the ease or difficulty of carrying out a particular behavior. It can be deduced from the results of the current study that the preservice teachers’ confidence in their use of digital tools and the resources to promote those tools did not have a predictive effect on forming their intention to use them in their future teaching. This finding may be attributable to the limited opportunities that the preservice teachers were provided to engage with digital tools within authentic teaching and learning environments. Without having gained those experiences, it is possible that their intentions to use these tools may not have been influenced by their perceived behavioral control (Hou et al., 2022). Similarly, their attitudes toward digital learning tools did not show any influence on their behavioral intention. The literature contains mixed views regarding this finding; for example, some studies align with this view (e.g., Khong et al., 2022; Teo et al., 2011), while others were contradictory (e.g., Baturay et al., 2017; Müller & Leyer, 2023; Songkram & Osuwan, 2022). This suggests that preservice teachers’ attitudes toward these tools, whether favorable or unfavorable, does not influence their decision to employ them within their future teaching practices. The following explanations are proposed regarding the non-significant influence of attitude. In the current study, preservice teachers learned theoretical and practical knowledge about digital learning tools. However, whilst they were familiar with the tools, they lacked actual experience integrating these digital tools into real-life classes. Furthermore, the preservice teachers’ attitudes may not have been able to form that quickly since their course only covered one semester of the curriculum. Davis et al. (1989) indicated the limited prediction of attitude in behavioral intention; therefore, the preservice teachers’ perceptions of control and their positive or negative feelings regarding these tools may be shaped after having the opportunity to practice using the tools within authentic contexts, and the relationships between attitude and behavioral intention may then be more likely to manifest.

The current study showed TTF to be a significant factor affecting the constructs of behavioral intention, perceived usefulness, and ease of use. The significant links observed, as in TTF–PU and TTF–PEU, have also been confirmed in previous studies (Pal & Patra, 2021; Wu & Chen, 2017). Additionally, the significant link between TTF and BI was also supported by prior research by Kim and Song (2022). If preservice teachers evaluate the appropriate match between task and technology, they tend to utilize digital learning tools in their future teaching practices. Moreover, when preservice teachers perceive that the fit between task and technology is high, they will more likely consider that using the digital tools in question will contribute to their teaching performance and often regard them as requiring minimal effort. In the current study, the characteristics of various digital tools, such as the interface, menu, and the type of material that they can be used to design, were taught to the preservice teachers as part of their teacher training course on instructional technology. Thus, task-technology fit perceptions were shaped; hence, according to this belief, they may consider these tools useful and easy to use and thereby have a desire to continue using them in their future teaching practices.

The following implications are presented based on the results of the current study. The characteristics of digital tools are essential to preservice teachers being able to design and construct learning materials. Thus, teacher training program instructors who aim to equip preservice teachers with subject-matter knowledge and professional teaching knowledge should examine the specific features of any digital tools they propose to include in their lectures and practical teaching. In addition, when digital tools are perceived as being easy to use, preservice teachers will have a tendency to evaluate them as useful for their future teaching practices. As such, instructors should select digital tools based on ease of use criteria and also their tasks and technology fit. Another implication relates to the link between perceived usefulness and behavioral intention. It is considered essential to teach preservice teachers about the various types of instructional tools available, how to integrate them into teaching and learning, and the benefits of such practices, which can affect their overall perceptions of the usefulness of these tools. Additionally, the social circuit of preservice teachers should be considered as a means to encouraging them to utilize and integrate digital tools into their future teaching practices.

6. Conclusions

The proposed model provided valid and reliable results regarding preservice teachers’ intention to benefit from the use of digital tools in their future teaching practices. Task-technology fit was shown to be the best indicator of intention to employ digital tools to facilitate instruction. Attitude and perceived behavioral control were not found to be predictive of behavioral intention, but subjective norms and perceived usefulness were. As a result, the model can be said to have a moderate strength in explaining prospective teachers’ intentions to employ digital tools for classroom learning. The current study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by introducing an integrated approach that combines the TAM, TPB, and TTF models.

6.1. Limitations

The current study presents certain limitations.

First, it may be possible that if the preservice teachers had used digital tools as part of their authentic teaching practice, such as use of the tools, designing materials, and integrating them within courses, their perceptions of control and attitudes could have influenced their behavioral intention. Therefore, future studies could focus on accepting digital tools after long-term usage through longitudinal studies or experimental designs.

Second, the current study opted to include the TAM, TPB, and TTF models, where alternatives such as motivation factors and expectation-confirmation theory could be considered in order to explore different factors that may affect preservice teachers’ digital tools’ acceptance.

Third, future studies of this nature could be conducted with both inservice and preservice teachers, enabling comparisons to be drawn between the two groups.

Fourth, the study employed a cross-sectional research method; however, in order to achieve a deeper understanding of the factors affecting preservice teachers’ intention to use digital tools, qualitative research methods or mixed methods could be implemented in future studies. Moreover, the participant pool was primarily composed of female students. Future research should aim to replicate the study with a more evenly distributed gender representation.

Fifth, a self-report data collection tool was used which had a limitation concerning social desirability. Thus, to enable participants’ actual behaviors and perceptions to be better understood, several tools such as observation forms and lesson plans could be included to examine the factors in play.

Sixth, the current study’s sample consisted of preservice teachers from one university located in the Aegean Region of Turkey, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies could employ alternative sampling techniques with larger samples in Turkey or also in other countries for the purposes of cross-cultural comparison. Finally the collected data were analyzed according to the PLS–SEM method, which was aimed at prediction of the dependent construct. However, this method could be said to present certain limitations such as lacking any measure of goodness of model fit and working with small sample sizes compared to covariance-based SEM (Hair et al., 2011). As such, it may be advisable to conduct future research that analyzes data according to covariance-based SEM.

7. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Erhan Ünal, Ahmet Murat Uzun; Formal analysis: Erhan Ünal; Investigation: Erhan Ünal, Ahmet Murat Uzun; Methodology: Erhan Ünal; Writing – original draft: Erhan Ünal, Ahmet Murat Uzun; Writing – review & editing: Erhan Ünal, Ahmet Murat Uzun.

8. FUNDING

There is no funding.

9. referencEs

Aivazidi, M., Michalakelis, C., Krouska, A., Sgouropoulou, C., & Cristea, A. I. (2021). Exploring primary school teachers’ intention to use e-learning tools during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 11(11), Article 695. https://doi.org/10.3390/EDUCSCI11110695

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11-39). Springer.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 27-58.

Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314-324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

Almulla, M. A. (2022). Using digital technologies for testing online teaching skills and competencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 14(9), Article 5455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095455

Anderson, S., Groulx, J., & Maninger, R. (2011). Relationships among preservice teachers’ technology-related abilities, beliefs, and intentions to use technology in their future classrooms. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 45(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.45.3.d

Ateş, H., & Garzón, J. (2022). Drivers of teachers’ intentions to use mobile applications to teach science. Education and Information Technologies, 27(2), 2521-2542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10671-4

Baber, H. (2021). Modelling the acceptance of e-learning during the pandemic of COVID-19-A study of South Korea. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(2), 100503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100503

Bajaj, P., Khan, A., Tabash, M. I., Anagreh, S., & Koo, A. C. (2021). Teachers’ intention to continue the use of online teaching tools post Covid-19. Cogent Education, 8(1), Article 2002130. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.2002130

Baturay, M. H., Gökçearslan, Ş., & Ke, F. (2017). The relationship among pre-service teachers’ computer competence, attitude towards computer-assisted education, and intention of technology acceptance. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTEL.2017.084084

Bower, M. (2016). Deriving a typology of Web 2.0 learning technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(4), 763-777. https://doi.org/10.1111/BJET.12344

Bower, M., & Torrington, J. (2020). Typology of free web-based learning technologies. Educause. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2020/4/typology-of-free-web-based-learning-technologies

Casey, J. E., Pennington, L. K., & Mireles, S. V. (2021). Technology Acceptance Model: Assessing Preservice Teachers’ Acceptance of Floor-Robots as a Useful Pedagogical Tool. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 26(3), 499-514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09452-8

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Methodology for business and management. Modern methods for business research (pp. 295-336). Erlbaum.

Dahri, N. A., Yahaya, N., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Almogren, A. S., & Vighio, M. S. (2024). Investigating factors affecting teachers’ training through mobile learning: Task technology fit perspective. Education and Information Technologies, 29(12), 14553-14589. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10639-023-12434-9

Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results. [Doctoral dissertation]. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management science, 35(8), 982-1003.

Eksail, F. A. A., & Afari, E. (2020). Factors affecting trainee teachers’ intention to use technology: A structural equation modeling approach. Education and Information Technologies, 25(4), 2681-2697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10086-2

Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Addressing first- and second-order barriers to change: strategies for technology integration. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(4), 47-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02299597

Ertmer, P. A., & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T. (2010). Teacher technology change: How knowledge, confidence, beliefs, and culture intersect. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(3), 255-284. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2010.10782551

European Commission. (2017). DigCompEdu framework. https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/digcompedu/digcompedu-framework_en

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior research methods, 41(4), 1149-1160.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Goodhue, D. L., & Thompson, R. L. (1995). Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 19(2), 213-233. https://doi.org/10.2307/249689

Granić, A., & Marangunić, N. (2019). Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2572-2593. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12864

Georgiou, D., Trikoili, A., & Kester, L. (2023). Rethinking determinants of primary school teachers’ technology acceptance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers and Education Open, 4, 100145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2023.100145

Gurer, M. D. (2021). Examining technology acceptance of pre-service mathematics teachers in Turkey: A structural equation modeling approach. Education and Information Technologies, 26, 4709-4729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10493-4

Habibi, A., Riady, Y., Samed Al-Adwan, A., & Awni Albelbisi, N. (2023). Beliefs and knowledge for pre-service teachers’ technology integration during teaching practice: an extended theory of planned behavior. Computers in the Schools, 40(2), 107-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2022.2124752

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Qadri, M. A., & Suman, R. (2022). Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable Operations and Computers, 3, 275-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004

Hew, K. F., & Brush, T. (2007). Integrating technology into K-12 teaching and learning: Current knowledge gaps and recommendations for future research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 55(3), 223-252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-006-9022-5

Hou, M., Lin, Y., Shen, Y., & Zhou, H. (2022). Explaining pre-service teachers’ intentions to use technology-enabled learning: an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 900806. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2022.900806

Hong, X., Zhang, M., & Liu, Q. (2021). Preschool teachers’ technology acceptance during the COVID-19: an adapted technology acceptance model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.691492

Inan, F. A., & Lowther, D. L. (2010). Factors affecting technology integration in K-12 classrooms: A path model. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(2), 137-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11423-009-9132-Y

International Society for Technology in Education. (2017). ISTE standards: For educators. https://iste.org/standards/educators

Islamoglu, H., Kabakci Yurdakul, I., & Ursavas, O. F. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ acceptance of mobile-technology-supported learning activities. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(2), 1025-1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09973-8

Khong, H., Celik, I., Le, T. T. T., Lai, V. T. T., Nguyen, A., & Bui, H. (2022). Examining teachers’ behavioural intention for online teaching after COVID-19 pandemic: A large-scale survey. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 5999–6026. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10639-022-11417-6

Kim, R., & Song, H.-D. (2022). Examining the influence of teaching presence and task-technology fit on continuance intention to use MOOCs. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 31(4), 395-408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00581-x

King, W. R., & He, J. (2006). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 43(6), 740-755.

Kreijns, K., Van Acker, F., Vermeulen, M., & Van Buuren, H. (2013). What stimulates teachers to integrate ICT in their pedagogical practices? the use of digital learning materials in education. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.008

Li, K., Li, Y., & Franklin, T. (2016). Preservice teachers’ intention to adopt technology in their future classrooms. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 54(7), 946–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633116641694

Lee, H. I., Chiu, S. H., Chen, Y. L., Lin, H. Y., & Lin, T. Y. (2022). Determinants of foreign language teachers’ intention to adopt online teaching: an empirical study by the combined model of TAM and TTF. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series (pp. 249–253). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3568739.3568781

Lo Presti, A., De Rosa, A., & Viceconte, E. (2021), I want to learn more! Integrating technology acceptance and task–technology fit models for predicting behavioural and future learning intentions. Journal of Workplace Learning, 33(8), 591-605. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-11-2020-0179

Lu, H. P., & Yang, Y. W. (2014). Toward an understanding of the behavioral intention to use a social networking site: An extension of task-technology fit to social-technology fit. Computers in Human Behavior, 34, 323-332.

Luik, P., & Taimalu, M. (2021). Predicting the intention to use technology in education among student teachers: A path analysis. Education Sciences, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090564

Mathieson, K. (1991). Predicting user intentions: comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Information Systems Research, 2(3), 173-191.

Mei, B., Brown, G. T. L., & Teo, T. (2018). Toward an understanding of preservice english as a foreign language teachers’ acceptance of computer-assisted language learning 2.0 in the people’s republic of China. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 56(1), 74–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633117700144

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (2010). Fatih Projesi [Fatih Project]. http://fatihprojesi.meb.gov.tr/

Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı (2017). Öğretmenlik mesleği genel yeterlikleri [General competencies for teaching profession. Directorate General for Teacher Training and Development]. https://oygm.meb.gov.tr/dosyalar/StPrg/Ogretmenlik_Meslegi_Genel_Yeterlikleri.pdf

Müller, W., & Leyer, M. (2023). Understanding intention and use of digital elements in higher education teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 15571-15597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11798-2

Ng, W. (2015). Theories underpinning learning with digital technologies. In New Digital Technology in Education. (pp. 73-94). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05822-1_4

Nunnally J. C., Bernstein I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A., Liao, J. Y. C., Sadik, O., & Ertmer, P. (2018). Evolution of Teachers’ Technology Integration Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices: How Can We Support Beginning Teachers Use of Technology? Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 50(4), 282-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2018.1487350

Paetsch, J., & Drechsel, B. (2021). Factors influencing pre-service teachers’ intention to use digital learning materials: a study conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 4953. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2021.733830

Pal, D., & Patra, S. (2021). University Students’ perception of video-based learning in times of COVID-19: A TAM/TTF Perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 37(10), 903-921. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1848164

Parkman, S., Litz, D., & Gromik, N. (2018). Examining pre-service teachers’ acceptance of technology-rich learning environments: A UAE case study. Education and Information Technologies, 23(3), 1253-1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9665-3

Polly, D., Martin, F., & Byker, E. (2022). Examining pre-service and in-service teachers’ perceptions of their readiness to use digital technologies for teaching and learning. Computers in the Schools, 40(1), 22-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2022.2121107

Pozo, J. I., Cabellos, B., & del Puy Pérez Echeverría, M. (2024). Has the educational use of digital technologies changed after the pandemic? A longitudinal study. PLOS ONE, 19(12), Article e0311695. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0311695

Sangeeta, & Tandon, U. (2020). Factors influencing adoption of online teaching by school teachers: A study during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(4), Article e2503. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2503

Sharma, S., & Saini, J. R. (2022). On the role of teachers’ acceptance, continuance intention and self-efficacy in the use of digital technologies in teaching practices. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(6), 721-736. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1998395

Songkram, N., & Osuwan, H. (2022). Applying the technology acceptance model to elucidate k-12 teachers’ use of digital learning platforms in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 14(10), Article 6027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106027

Şimşek, A. S., & Ateş, H. (2022). The extended technology acceptance model for Web 2.0 technologies in teaching. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 8(2), 165-183. https://doi.org/10.24310/INNOEDUCA.2022.V8I2.15413

Tang, K. Y., Hsiao, C. H., Tu, Y. F., Hwang, G. J., & Wang, Y. (2021). Factors influencing university teachers’ use of a mobile technology-enhanced teaching (MTT) platform. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(5), 2705–2728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10032-5

Taylor, M., Fudge, A., Mirriahi, N., & De Laat, M. (2021). Use of digital technology in education: literature review. Centre for Change and Complexity in Learning, The University of South Australia. https://www.education.sa.gov.au/docs/ict/digital-strategy-microsite/c3l-digital-technologies-in-education-literature-review.pdf

Taylor, S., & Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 144-176. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.6.2.144

Teo, T. (2012). Examining the intention to use technology among pre-service teachers: An integration of the Technology Acceptance Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Interactive Learning Environments, 20(1), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494821003714632

Teo, T., Fan, X., & Du, J. (2015). Technology acceptance among pre-service teachers: Does gender matter? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(3), 235-251. https://doi.org/10.14742/AJET.1672

Teo, T., Huang, F., & Hoi, C. K. W. (2018). Explicating the influences that explain intention to use technology among English teachers in China. Interactive Learning Environments, 26(4), 460-475. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2017.1341940

Teo, T., & Lee, C. B. (2010). Explaining the intention to use technology among student teachers An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Campus-Wide Information Systems, 27(2), 60-67. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650741011033035

Teo, T., Sang, G., Mei, B., & Hoi, C. K. W. (2019). Investigating pre-service teachers’ acceptance of Web 2.0 technologies in their future teaching: a Chinese perspective. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(4), 530-546. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1489290

Teo, T., & Tan, L. (2012). The theory of planned behavior (TPB) and pre-service teachers’ technology acceptance: A validation study using structural equation modeling. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 20(1), 89-104.

Teo, T., Ursavaş, Ö. F., & Bahçekapili, E. (2011). Efficiency of the technology acceptance model to explain pre-service teachers’ intention to use technology: A Turkish study. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 28(2), 93-101. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650741111117798

Teo, T., & van Schaik, P. (2012). Understanding the Intention to Use Technology by Preservice Teachers: An Empirical Test of Competing Theoretical Models. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 28(3), 178-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2011.581892

Teo, T., Zhou, M., Fan, A. C. W., & Huang, F. (2019). Factors that influence university students’ intention to use Moodle: A study in Macau. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67, 749-766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09650-x

Teo, T., Zhou, M., & Noyes, J. (2016). Teachers and technology: Development of an extended theory of planned behavior. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64, 1033-1052.

Timotheou, S., Miliou, O., Dimitriadis, Y., Villagrá Sobrino, S., Giannoutsou, N., Cachia, R., Martínez Monés, A., & Ioannou, A. (2023). Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools’ digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 6695-6726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11431-8

Ursavaş, Ö. F., Yalçın, Y., & Bakır, E. (2019). The effect of subjective norms on preservice and in-service teachers’ behavioural intentions to use technology: A multigroup multimodel study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2501–2519. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12834

Valtonen, T., Kukkonen, J., Kontkanen, S., Mäkitalo-Siegl, K., & Sointu, E. (2018). Differences in pre-service teachers’ knowledge and readiness to use ICT in education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(2), 174-182.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 27(3), 425-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Wang, Y. (2022). A comparative study of Chinese and American preservice teachers’ intention to teach online based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 6391-6405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11442-5

Wang, C., Chen, X., Yu, T., Liu, Y., & Jing, Y. (2024). Education reform and change driven by digital technology: a bibliometric study from a global perspective. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11, Article 256. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02717-y

Watson, J. H., & Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. (2021). Predicting preservice teachers’ intention to use technology-enabled learning. Computers & Education, 168, Article 104207. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPEDU.2021.104207

Wilson, M. L., Ritzhaupt, A. D., & Cheng, L. (2020). The impact of teacher education courses for technology integration on pre-service teacher knowledge: A meta-analysis study. Computers & Education, 156, Article 103941. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPEDU.2020.103941

Wohlfart, O., & Wagner, I. (2024). Longitudinal perspectives on technology acceptance: Teachers’ integration of digital tools through the COVID-19 transition. Education and Information Technologies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10639-024-12954-Y

Wong, K. T., Teo, T., & Russo, S. (2013). Interactive Whiteboard acceptance: applicability of the UTAUT model to student teachers. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-012-0001-9

Wu, B., & Chen, X. (2017). Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.028

Wu, R., & Yu, Z. (2022). The Influence of social isolation, technostress, and personality on the acceptance of online meeting platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(17), 3388-3405. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2097779

Yükseköğretim Kurulu. (2018). Yeni öğretmen yetiştirme lisans programları [New teacher training undergraduate programs]. https://n9.cl/e847sm

Yusop, F. D., Habibi, A., & Razak, R. A. (2021). Factors Affecting Indonesian Preservice Teachers’ Use of ICT During Teaching Practices Through Theory of Planned Behavior. SAGE Open, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211027572