Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation Vol. 11. No. 1. June 2025 - pp. 47-73 - ISSN: 2444-2925

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.111.2025.20896

Assessing the Impact of Microsoft Copilot and ChatGPT on EFL Learners’ Interactional Metadiscourse in Argumentative Writing

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.1. INTRODUCTION

The integration of AI (artificial intelligence) into educational systems has brought about significant changes, enhancing both teaching and learning processes. AI-powered tools offer personalized learning experiences, adapting to the unique needs of each student. These tools analyze students’ performance and provide tailored feedback, helping them to overcome specific challenges and improve their skills (LaRue Keeley, 2024). Recent studies (e. g., Lo et al., 2024) have shown that AI-driven educational technologies can improve learning outcomes, increase accessibility, and foster a more inclusive learning environment. By leveraging machine learning algorithms, educational platforms can predict student performance, identify at-risk students, and provide timely interventions to support their academic progress (Sadiku et al., 2022). Thus, the impact of AI on education is profound, transforming traditional educational models and paving the way for innovative pedagogical approaches (Holmes et al., 2022).

This study explores the uncharted territory of how AI-assisted chatbots, specifically ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot, enhance interational metadiscourse markers (IMMs) in EFL learners’ argumentative writing. This research goes beyond theoretical discussions by providing empirical evidence of the effectiveness of these AI tools in improving critical writing skills. By comparing ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot within an educational context, this research showcases their advanced natural language processing capabilities, which allow for more nuanced and context-aware interactions than traditional AI tools. This ability to provide personalized feedback is particularly beneficial for fostering IMMs, which is often lacking in more rigid, rule-based systems. The real-time, adaptive feedback they offer can lead to more engaging and effective learning experiences, thus improving educational outcomes. The continuous updates and improvements in ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot ensure they remain at the forefront of technological advancements, providing cutting-edge solutions that evolve with educational demands. This dynamic nature sets them apart from other AI tools that may not receive regular updates or enhancements, thereby maintaining their relevance and effectiveness in educational contexts.

Lo et al. (2024) ssytematiclly reviewed the appliaction of AI (e.g., ChatGPT) in the English as a second/foreign language education in 70 empirical research studies and found that the majority of the studies (n = 29) had focused on the students’ use of AI tools in writing, including, but not limited to, the generation of ideas in writing, writing organization and structure, and spelling and grammar in writing. Lo et al.’s systematic review highlights the potential benefits of using AI tools to enhance different facets of writing skills. However, there is a growing need to extend this line of research to explore the impact of AI on interactional metadiscourse (IM) in argumentative writing. Investigating how AI tools like ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot can assist learners in effectively using IMMs in their writing provide a deeper understanding of the role of AI in facilitating more nuanced and coherent written communication. This study may contribute to the broader field of language learning and offer practical insights for educators and learners seeking to leverage AI for advanced writing skills development. Therefore, more research studies are needed to help language teachers to gain a better understanding of how these AI-powered chatbots can be safely implemented in language classes to facilitate the teaching/learning process. Against this background, the current research examined how the application of AI chatbots contributes to the employment of IM in argumentative writing abilities of English-as-a-foreign language (EFL) learners.

This research study is innovative in several keyways. Firstly, it provides a comparative analysis of two leading AI models in the context of language teaching and learning, offering valuable insights into their relative strengths and weaknesses. Secondly, the study employs a detailed examination of transformer model architectures and training data updates, shedding light on the underlying causes of performance differences. Finally, this research contributes to the ongoing discourse on AI-assisted education by highlighting the potential of AI tools to enhance specific aspects of academic writing, thereby informing future developments in AI-driven educational technologies. Overall, the combination of advanced language processing, personalized feedback, and continuous improvement make ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot superior options for enhancing EFL learners’ IMMs in argumentative writing. The study provides valuable insights for educators and policymakers aiming to implement effective AI-assisted strategies in their curricula, potentially leading to more effective teaching methods and improved learning outcomes.

The significance of of using AI tools in the realization of IMMs for Iranian EFL learners lies in their capability to enhance their argumentative writing skills. Iranian language learners follow discourse and linguistic patterns in their argumentation, which may differ from those native-English writers use (Pearson & Abdollahzadeh, 2023). Mastering IMMs helps bridge such discoursal differences, making their writing more effective and culturally appropriate. It also improves critical thinking and argumentation skills, which are crucial for presenting ideas clearly, anticipating reader objections, and providing appropriate rebuttals. Lastly, in the globalized world, persuasive English writing is a valuable skill, enabling Iranian EFL learners to engage effectively in academic and professional settings. Highlighting these points underscores the importance of this study for English language education in Iran. Therefore, the following research questions were raised in order to accomplish the purposes.

Are there any significant differences between ChatGPT-based instruction, Microsoft Copilot, and conventional instruction in employing IMMs among Iranian advanced EFL learners while producing argumentative writing?

How do the learners in experimental groups perceive ChatGPT-based instruction and Microsoft Copilot as feedback and learning tools while using IMMs in their argumentative writing skills?

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

In this section, firstly, we explain the theory we have used to base this study on and disucss how it is related to the present study. Next, Hylands’ (2019) model of interactional metadiscourse, as used in the study, is introduced and elaborated on, followed by summaries of the fidnings of the empirical studies on metadiscourse, and the critical evaluation of these studies. Lastly, the role of AI tools in language education, most specifically ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot, is explained, and the research studies using AI in language education are summarised, and their limitations are discussed.

2.1. Theoretical framework of the study

Feedback theory in language learning, which emphasizes the importance of specific, timely, constructive, and informative feedback, significantly enhances learners’ linguistic abilities by helping them identify their progress and areas needing improvement. Studies like those by Nassaji and Kartchava (2024) and Moser (2020) have underscored the role of feedback in fostering engagement, self-regulation, and performance in learners. This process promotes a growth mindset where challenges are viewed as opportunities for development. Meanwhile, GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot as writing assistants offer a practical application of feedback theory by providing immediate, precise, and constructive feedback to writers. GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot aid in idea generation, content creation, editing, and proofreading, thereby not only enhancing efficiency and creativity but also aligning with the principles of effective feedback (Van, 2023). For instance, when GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot suggest improvements or identifies errors, they act as forms of corrective feedback that writers can utilize to refine their work, as a human tutor or an editor does. This immediate feedback loop supports writers in making real-time adjustments, fostering a continuous learning process that mirrors the benefits highlighted in feedback theory (Mackey, 2020). By integrating these feedback mechanisms, GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot help maintain consistency, accuracy, and originality in writing while addressing quality control and ethical considerations. In essence, the synergy between feedback theory and GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot as writing assistants demonstrate how advanced AI tools can operationalize theoretical principles of feedback, providing writers with support and guidance needed to enhance their skills and produce high-quality work (Bautista, 2024). This combined approach underscores the transformative potential of leveraging feedback and AI technology to foster improvement in both language learning and writing processes.

The present research was grounded in feedback theory process (Winstone & Carless (2020) and Barrot’s (2023) ChatGPT speculation, with the objective of employing GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot as tools for providing formative feedback that incorporates both self-assessment and peer-assessment. The conceptual framework for utilizing GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot to improve formative feedback can be examined through two prominent theories. The first is the dialogic feedback model articulated by Winstone and Carless (2020), who contend that feedback characterized by interactive dialogue allows students to clarify their expectations, obtain essential information and guidance, and enhance their learning outcomes. GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot facilitate this interactive process by responding to user inquiries regarding various aspects of writing, providing suggestions as needed, and acting as an accessible support tool. Additionally, it identifies and rectifies errors, thereby enriching the interactive exchange. The second theory is Barrot’s (2023) view of GPT-4 and Microsoft Copilot as reliable writing assistants that offer prompt, context-sensitive, and personalized feedback to students at various stages of their writing endeavors.

The current study followed a comparative study of AI-based assessments (ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot) as feedback tools to help learners realize IMMs and assess their impact on learners’ argumentative writing skills. For this reasosn, we now turn to metadiscourse to explain its princples and summarise the fidnings of previous studies in this area.

2.2. Interactional metadiscourse

Metadiscourse serves an essential function in achieving persuasion in all forms of human communication. Despite the seemingly impersonal nature of academic writing, establishing a suitable connection between the author and the audience is essential for effectively conveying a credible argument (Qiu et al., 2024). In order to achieve this goal, writers must utilize rhetorical strategies that are persuasive to their audience. Metadiscourse is a term frequently utilized in discourse analysis, denoting features of a text that pertain to its structure or substance (Ädel, 2023). Metadiscourse involves the linguistic strategies utilized by writers or speakers to influence how a recipient understands a written or spoken work. Following Hyland’s (2019) interpersonal metadiscourse, the current research shed light on the IMMs (table 1). Regarding argumentative writing, IMMs are crucial to support the writer’s ideas and aid the reader’s understanding (Abdelrahim & Abdelrahim, 2020).

TABLE 1. Interactional metadiscourse in Hyland’s model (Hyland, 2019, p. 58)

| Interactional metadiscourse | Definition | Examples |

| Hedges | refrain from commitment | perhaps; about |

| Boosters | emphasize assurance | certainly; clearly |

| Attitude markers | conveying the writer’s stance | unfortunately; I agree |

| Self-mentions | author mention | I; my |

| Engagement markers | intentionally foster a connection with the reader | consider; note |

IMMs pertain to the methods by which writers engage in interaction through the intrusion and commentary on their own messages (Hyland, 2019). The primary objective for writers is to clarify their perspectives and actively involve readers by inviting them to react to the developing narrative. This process reflects the writer’s distinctive persona recognized within the community, encompassing the manner in which they articulate judgments and explicitly align themselves with their audience. IMMs serve a fundamentally evaluative and participatory role, demonstrating solidarity, anticipating counterarguments, and engaging in a hypothetical dialogue with others (Gordon, 2024). It illustrates the degree to which the writer endeavors to collaboratively construct the text alongside the readers.

To enhance their understanding of metadiscourse, scholars have undertaken investigations in a variety of scholarly genres including research articles (RAs) (Hyland & Jiang, 2022; Li & Xu, 2020; Pearson & Abdollahzadeh, 2023), concluding that metadiscourse has been essential in organizing discourse, involving the audience. The findings of these studies showed that in RAs writers tend to engage with their audience in an impersonal manner rather than a personal tone. This preference for impersonal metadiscourse can be attributed to the characteristics of research article writing, where the primary function of metadiscourse is to facilitate the reading experience by signaling the structure of the discourse and elucidating the relationships and meanings of the propositions presented. Other studies adopted an experimental approach such as the incorporation of learning-oriented language assessment into metadiscourse (Esfandiari & Allaf-Akbary, 2024a), explicit and implicit teaching of IMs (El-Dakhs, et al., 2022), and metadiscourse learning through AI-powered chatbots (Esfandiari & Allaf-Akbary, 2024b), stating that ChatGPT-based instruction was useful in learning and employing IMMs and learners had positive viewpoints towards ChatGPT-based instruction.

Ho and Li (2018) conducted research to analyze 181 argumentative essays written by first-year university students in a timed writing task using the interpersonal model of metadiscourse. The findings showed that low-rated essays had difficulties using metadiscourse to construct convincing arguments compared to high-rated essays. The study suggested that teaching and learning metadiscourse should be implemented in secondary and early tertiary education to help learners effectively use metadiscourse in academic writing.

Esfandiari and Khatibi (2022) analyzed 240 English academic RAs by American and Persian scholars to study IM. Using Hyland’s (2019) interpersonal model, Esfandiari and Khatibi examined common features and different purposes in abstracts, introductions, and conclusions across American and Persian international and national corpora. Similarities were found in metadiscourse preferences between American and Persian academics, but differences in marker utilization featured as well. The results suggested that cross-cultural influences play a significant role in the frequency and utilization of interactional resources.

In their study, Rostami Aboo saeedi et al. (2023) conducted interviews with Iranian EFL graduate students to examine their perspectives on using IMMs in their theses. A total of 20 participants, including 15 females and 5 males, were interviewed. The interviews focused on topics such as general concepts, audience, language support, organization, and attitude. The analysis of the interviews revealed five main themes: general, audience-related, language support, organization, and attitude. Participants expressed a preference for research topics that are engaging and practical. Using attitude markers, engagement markers, and hedges effectively aids expressing viewpoints in theses, as stated by interviewees. They also discussed their challenges with writing coherence and cohesion in their theses, highlighting the importance of using markers to convey their viewpoints effectively.

In another more recent study, Qui et al. (2024) investigated IM, including hedges, boosters, attitude markers, and self-mentions in a corpus of L1-English expert and L1-Chinese student writing in Agricultural Science. Both groups showed differences in the use of these metadiscourse features, with L1-English experts using more hedges and L2 students using more boosters and attitude markers. Despite some similarities in functional subtypes, L1-English experts excelled in stating a goal or purpose in self-mentions. The analysis revealed discipline-related metadiscourse challenges for students. The study suggested the need for improved coding methods and highlights the importance of teaching metadiscourse to discipline-specific writers using relevant corpora.

Despite the significant advancements in understanding metadiscourse within academic contexts, as reviewed above, which underscore the role of impersonal engagement in structuring academic discourse, critical gaps remain that necessitate further investigation, particularly in the context of AI-assisted learning tools. The above-reviewed studies emphasize the structural importance of metadiscourse but have not explored the potential of AI tools to transform these dynamics by providing interactive and personalized engagement. While experimental approaches by Esfandiari and Allaf-Akbary (2024b) have demonstrated the effectiveness of AI in teaching metadiscourse, their study did not compare the benefits of different AI-chatbots. Ho and Li (2018) highlighted the struggle which students face in using metadiscourse effectively to construct convincing arguments, pointing to the need for early education in metadiscourse that the current research seeks to address by evaluating how different AI tools can enhance argumentative writing skills through consistent guidance. By focusing on AI-assisted learning environments, this study addresses the limitations of previous studies that often isolate metadiscourse from its broader communicative context.

Examining the specific impact of two different AI tools on EFL learners’ interactional metadiscourse in argumentative writing, our study aims to provide new insights and practical applications, enhancing metadiscourse learning and usage among EFL learners. Therefore, in the next section, we will explain AI tools and present a critical discussion of the studies in this area.

2.3. AI-powered Chatbots in language education

As new tools continue to emerge with the advancement of technology, one of the most cutting-edge and contemporary technologies is AI. AI encompasses a class of systems which can be mechanized by utilizing technologies such as intelligent retrieval and statistical procedures (Lee et al., 2023). These systems have the capability to assist learners in performing tasks more quickly and accurately than they could on their own (Shneiderman, 2022). The advancement of AI-powered technologies has simplified the process for learners to receive feedback on their written work (Marzuki et al., 2023). The employment of AI chatbots such as ChatGPT to enhance feedback in writing courses is an emerging field that warrants additional research (Barrot, 2023). ChatGPT’s role as a learning aid can be linked to constructivism. The constructivist learning theory asserts that individuals actively build their understanding by interacting with new information, which they then assimilate with their prior knowledge (McCourt, 2023). Allagui (2023) suggests that ChatGPT has the ability to aid learners in their writing by offering suitable guidance on content and structure while they are composing their work. Learners have the opportunity to obtain personalized feedback that is appropriate for their specific requirements. Integrating AI literacy across academic disciplines helps students connect AI knowledge with their field-specific learning, fostering a comprehensive understanding of AI’s impact and developing critical evaluation skills (Kim et al., 2022). To bridge the theoretical gap, we have explained how AI chatbots’ advanced natural language processing capabilities can enhance IMMs. For instance, AI tools can analyze and generate texts with nuanced context awareness, offering learners immediate and contextually appropriate feedback on their use of IMMs. This connection is supported by studies that show how technology-mediated feedback can improve learners’ writing skills by providing targeted guidance and promoting self-regulated learning (Xue, 2024).

Some studies have been conducted to highlight the significance of AI in learning lexical items and language structure (Wang & Guo, 2023), in giving feedback and invaluable data (Dai et al., 2023; Rudolph et al., 2023), promoting learners’ motivation (Ali et al., 2023), in creating fine texts (Gao et al., 2023), in developing learners’ writing skill (Mahapatra, 2021; Yan, 2023), thereby showing learners’ positive attitude towards AI, in personalized language learning (Amirjalili et al., 2024; Esfandiari & Allaf-Akbary, 2024c), in improving EFL speaking practice (Clark, 2024), demonstrating a positive influence on learners’ speaking abilities, encompassing accuracy and fluency. Huang et al. (2023), for example, carried out a comparative analysis to evaluate the academic achievement and learners’ involvement in an AI-enhanced classroom in contrast to a traditional classroom without AI technology. The outcomes demonstrated that learners in the AI-driven classroom revealed better learning results and increased levels of engagement, compared with their counterparts in the non-AI classroom. Huang and Zou (2024) examined the roles of enjoyment and readiness to engage in communication with AI. The results showed a positive and useful impact of AI in enhancing learners’ communication.

Several limitations emerge from the studies conducted on AI writing tools and their impact on EFL learners. For instance, Zhao (2022) critiques the focus of digital writing tools on revising and editing, highlighting a scarcity of support during the actual writing process, which may limit the development of holistic writing skills in learners. Moreover, Marzuki et al. (2023) highlight the positive perceptions of EFL teachers towards various AI writing tools, but they rely on qualitative data from a small sample, which may not fully capture broader trends and efficacy across diverse educational settings. Similarly, Escalante et al. (2023) compare AI-generated feedback with human tutors, finding no significant difference in outcomes, suggesting that a blended approach might be most effective. However, the study does not address the nuances of integrating such feedback seamlessly into traditional teaching methods.

Several other studies, as reviewed in this section, have focused on technology acceptance and its impact on learners. Wu et al. (2024), for example, employ the technology acceptance model and reveal that perceived ease of use significantly influences learners’ attitudes towards AI. However, the study indicates that perceived usefulness did not have a significant predictive value, suggesting potential gaps in aligning AI tool functionalities with learners’ specific needs. Furthermore, Huang et al. (2024) underscore the role of generative AI acceptance and teachers’ enthusiasm in enhancing learners’ well-being and self-efficacy. Nevertheless, the study does not address practical implementation strategies to sustain these positive effects. Additionally, Kim et al. (2024) identify both benefits and challenges in using a ChatGPT-4 integrated system but do not extensively explore long-term impacts on learners’ writing performance and emotional engagement. Boudouaia et al. (2024) demonstrate the effectiveness of ChatGPT-4 in improving EFL writing skills, but the controlled experimental design may not reflect real-world classroom dynamics and potential challenges in AI adoption. Lastly, Mahapatra (2024) reports positive impacts of ChatGPT on ESL students’ writing skills but emphasizes the need for proper training, highlighting a potential gap in resource availability and accessibility for effective AI tool utilization.

3. METHOD

3.1. Population and sample

The current study consisted of 90 advanced male and female EFL learners aged between 25 and 28. Their first language was Turkish. These learners were registered at the academic center for education, culture, and research (ACECR) in Ardabil, Iran. The participants were chosen through convenience sampling from a larger pool of 142 learners, built on their performance in Michigan Test of English Language Proficiency (MTELP) (Lim, 2011). Advanced learners are more capable of engaging deeply with AI tools like ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot, which are designed for high-level language processing and feedback. This proficiency level ensures that the impact of these tools can be more clearly observed and measured. None of the participants had already utilized ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot to enhance their proficiency in writing. Other inclusion criteria involved extensive years of learning experience, and a strong background in academic writing, evidenced by coursework and writing samples. We also considered their professional writing experience, self-assessment of writing skills, recommendations from language instructors, and previous research participation. These comprehensive criteria ensure the participants possess a high level of language competence, enhancing the validity and reliability of our study’s findings in terms of the impact of AI platforms on their interactional metadiscourse in writing.

Before the treatment sessions began, the participants were briefed on the objectives of the research and what was expected of them. In order to guarantee the participants’ proficiency level, all participants were required to take MTELP. Learners scoring above 70 percent were categorized as advanced level language learners (Phakiti, 2003). Ultimately, the participants were randomly assigned into three different groups: 30 participants in the ChatGPT group, 30 in the Microsoft Copilot group, and 30 in the control group. All groups received printed materials on introductory concepts of IMMs and their subcategories. The experimental groups shared 15 personal computers (one for every two participants) connected to the internet. They received 10 prompts per session related to IMMs, using ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot over six sessions, totaling 60 prompts, with a posttest in the final session. Prompts included identifying verbs for ‘Hedges’, providing examples of ‘Hedges’ and ‘Boosters’, and writing paragraphs including IMMs. Both experimental groups used the same prompts and received responses from their respective AI systems.

Prior to the grouping procedures and instructional courses, all participants underwent a metadiscourse pretest. This pretest involved analyzing four samples of TOEFL argumentative writing paragraphs to identify and underline IMMs. Participants who mistakenly underlined words with propositional meaning were randomly assigned to a study group, while those who correctly identified IMMs were not included in the further analysis. Before engaging in the study, the participants provided their consent to confirm that their participation was voluntary. At the outset of the treatment session, the participants received detailed information regarding the specific aims of the research. Treatment intervention lasted for nine sessions (three sessions per week). The first two sessions were to teach how to use AI-powered chatbots (following Mathur & Mahapatra, 2022, advocating the provision of training for students prior to the implementation of a digital tool in educational settings) and introductions of metadiscourse. Each session took two hours.

3.2. Research Instruments

Four assessment instruments were employed in this research: the MTELP, a semi structured interview, a pre-test, and a post-test as explained below.

3.2.1. MTELP

The MTELP is a standardized test designed to assess the English language skills of non-native speakers. It is divided into three sections in a multiple-choice format. This dependable evaluation consists of 40 grammar items presented in a conversational style, 40 vocabulary questions on synonyms or sentence completion, and 20 items aimed at assessing reading comprehension. The entire test administration lasted for 100 minutes. While the MTELP is regarded highly reliable, its reliability was assessed using the KR-21 formula, which yielded a reliability index of .81 in the context of this study.

3.2.2. Semi-structured interview

The next instrument employed was a researcher-developed, semi-structured interview that focused on the participants’ experiences with ChatGPT-based instruction and Microsoft Copilot. The research interview was researcher-made to fit the study’s needs, using a semi-structured format. This approach balanced guided questions with the flexibility to explore emerging topics based on participants’ responses, ensuring comprehensive and relevant data. The questions were specifically tailored to capture the unique perspectives of EFL learners using AI tools such as Microsoft Copilot and ChatGPT, enhancing the study’s reliability and validity. The interview development process followed five stages. Ultimately, three main interview questions were crafted. To ensure the content validity of the interview, two experts in educational psychology were consulted to evaluate the questions. Based on their feedback, the researchers reduced the number of questions from seven to three.

- We employ ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot for the assessment of our writing skills and those of our colleagues. How would you differentiate between the two instruments and characterize your interaction with the instruments?

- ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot provide feedback on multiple elements of the writing, such as five subcategories of IMMs. How are the two instruments different regarding giving feedback?

- What recommendations can you provide to enhance the effectiveness of utilizing ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot in realizing IMMs?

3.2.3. Pretest

Prior to the intervention, a pretest was administered to assess the initial ability of participants to identify and use IMMs in their writing. The pretest included four samples of TOEFL iBT (Test of English as a Foreign Language) argumentative writing paragraphs. Participants were asked to identify and underline IMMs in these samples. This pretest helped to determine the participants’ baseline proficiency in using IMMs. Participants who mistakenly underlined words with propositional meaning were randomly assigned to the study groups, while those who correctly identified IMMs were excluded from further analysis.

3.2.4. Posttest

At the end of the intervention, a posttest was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the instruction provided to each group. The posttest involved writing two argumentative paragraphs on topics taken from the TOEFL iBT. Participants were required to incorporate IMMs in their writing. The posttest assessed the improvement in participants’ use of IMMs after the intervention. Two raters evaluated both the pretest and posttest, and the inter-rater reliability method yielded coefficients of 0.77 for the pretest and 0.81 for the posttest, which tend to be acceptable relaibilty indeces, as explained in Pallant (2020).

3.3. Intervention and Instructional Activities

The study incorporated a structured intervention over nine sessions spanning three weeks, with three sessions per week, each lasting two hours. Participants were divided into three groups: ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, and a control group. In the ChatGPT group, the initial sessions were dedicated to introducing participants to ChatGPT and providing thorough training on how to effectively use its functionalities. This included instructions on accessing the tool, navigating its interface, and understanding how to leverage its capabilities for writing assistance. Following these introductory sessions, participants in ChatGPT group engaged in extensive practice sessions where they wrote paragraphs and focused on improving their use of IMMs with the real-time feedback provided by ChatGPT. These practice sessions allowed participants to submit their paragraphs, receive instant feedback, and refine their use of IMMs, fostering a deeper engagement with the material.

Similarly, the Microsoft Copilot group began with sessions that familiarized participants with Microsoft Copilot’s features and provided training on its use. Participants learned to draft, edit, and enhance their writing with real-time suggestions from Copilot, focusing on the strategic incorporation of IMMs. Throughout the practice sessions, participants wrote paragraphs, submitted them to Copilot, and received detailed recommendations for improving their writing.

Both experimental groups engaged with ten prompts per session, related to IMMs, and utilized their respective AI tools to receive guidance and feedback. In contrast, the control group adhered to conventional instruction methods, with participants practicing writing and receiving feedback from an instructor. These sessions focused on teaching the concepts of IMMs and their application in writing, relying on traditional methods where feedback was provided in subsequent sessions rather than in real-time.

Each group completed a total of nine sessions, with the final session dedicated to the posttest to assess their improved use of IMMs in argumentative writing. The structured approach in each group ensured comprehensive exposure to IMMs, with the experimental groups benefiting from the interactive and personalized feedback provided by the AI tools, while the control group followed a more traditional instructional method.

3.4. Procedure

The rationale for comparing ChatGPT-based instruction and Microsoft Copilot-based instruction is to understand the distinct capabilities and advantages each AI tool brings to language learning, particularly in helping EFL learners use IMMs in their argumentative writing. By evaluating the effectiveness of these tools, the study aims to determine which AI tool enhances learners’ writing skills more effectively. Each chatbot uses different algorithms and feedback mechanisms, which could lead to varying impacts on the learners’ writing. Including conventional instruction as a control allows us to measure the added benefits of AI-driven feedback compared to traditional methods. Additionally, examining learners’ perceptions of ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot provides insights into their usability and acceptance, which helps identify beneficial features and areas for improvement. Overall, this comparison aims to offer a comprehensive understanding of how various AI technologies can be integrated into language instruction to enhance educational.

The present study followed the convergent parallel design (Mackey & Gass, 2023) through which the researchers simultaneously collected and examined both quantitative and qualitative data during the same phase of the study and later combined the two sets of findings to create a comprehensive interpretation. In order to evaluate the writing skills of the participants at the beginning and end of the study, the second researcher instructed students to compose an argumentative essay.

In the next phase, both experimental groups underwent a brief training program focused on utilizing AI-powered chatbots within the writing classroom. Participants in experimental groups (ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot) and control group, each group consisting of thirty participants, were provided with printed files and papers focusing on introductory concepts of IMMs and subcategories of IMMs. Each experimental group benefitted from 15 personal computers (one for two participants) connected to the internet. Each session, the participants in both experimental groups received the same 10 prompts for IMMs realization to use ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot, totaling for 60 prompts in six sessions. The last one session was for the posttest. Five sample prompts were as follows:

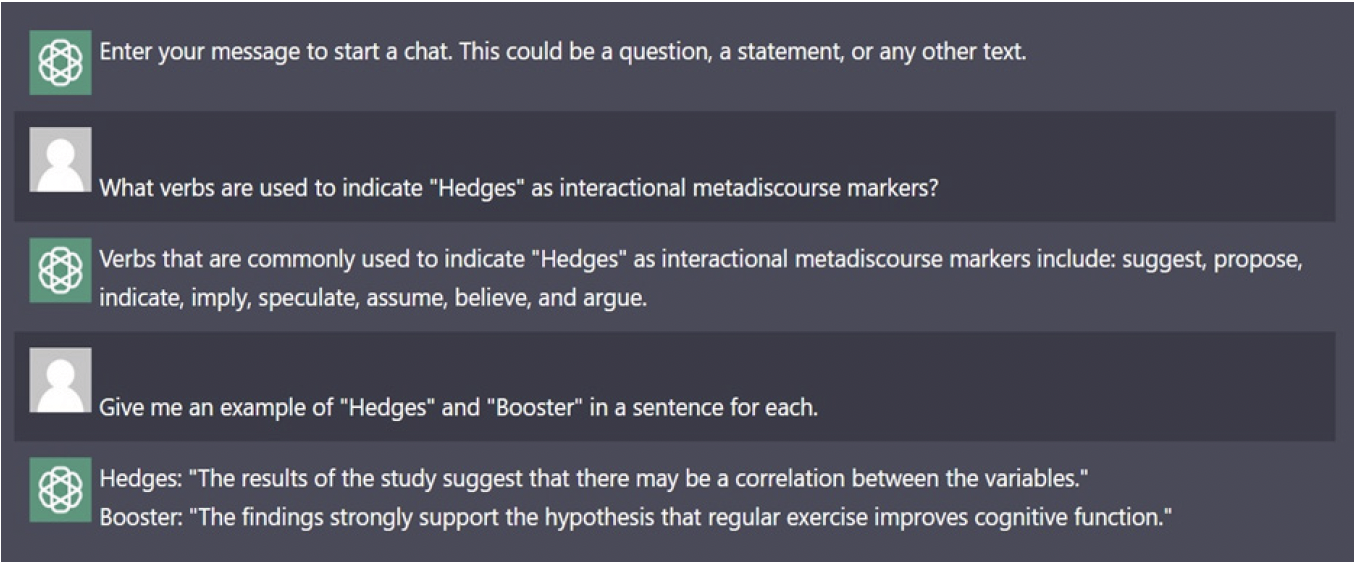

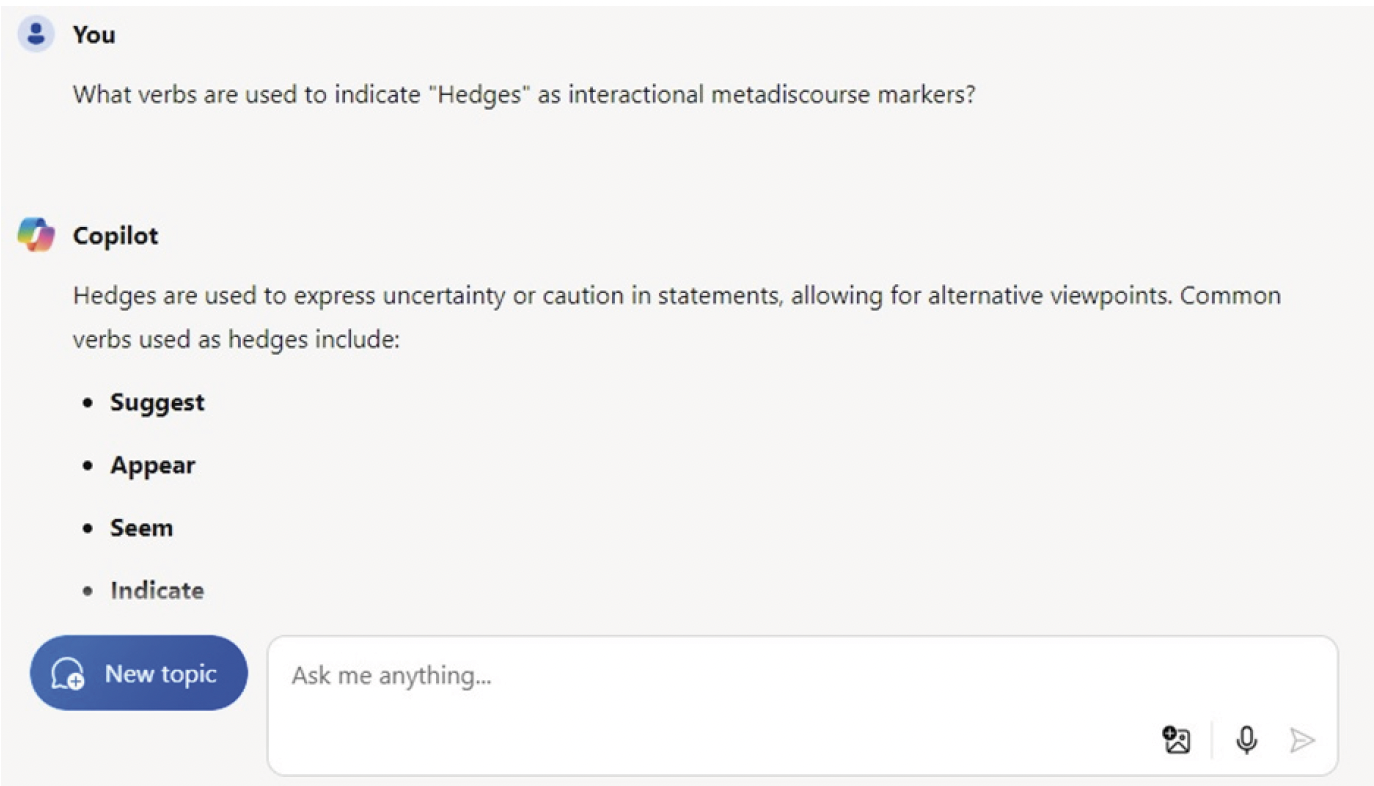

- What verbs are used to indicate “Hedges” as IMMs?

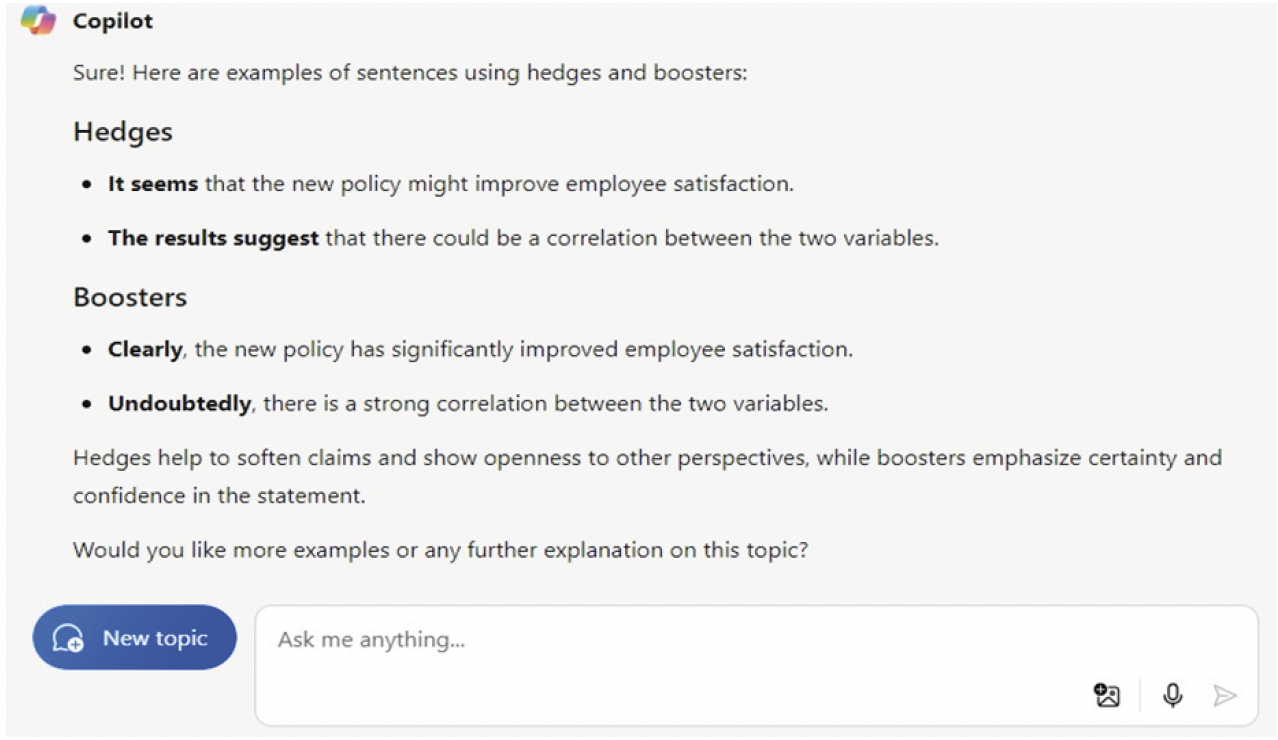

- Give me an example of “Hedges” and “Booster” in a sentence for each.

- What are the most frequent forms of “Attitude markers” as an IMM?

- Provide me with a paragraph including IMMs?

- Determine the IMMs in the following paragraph.

Both ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot groups used the same prompts and began to receive the answers from two AI-powered systems. As an example, Figure 1 shows the prompts and responses from ChatGPT. It should be noted that the teacher of the three groups was the second researcher.

FIGURE 1. ChatGPT response to prompts about IMMs

Accordingly, the same prompts were inserted into the Microsoft Copilot as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

FIGURE 2. Microsoft Copilot response to prompts about IMMs

FIGURE 3. Microsoft Copilot response to prompts about IMMs

The control group received the conventional instruction, meaning that they were given some reading passages to identify IMMs with the help of the teacher. In the posttest, all participants in three groups were required to write two argumentative paragraphs (no more than 250 words each), on the following topics taken from TOEFL iBT.

- Should dogs be allowed inside restaurants and stores?

- Should schools give students money to invest in their futures?

Two raters evaluated both the pretest and post-test. The inter-rater reliability method between the two raters turned out to be 0.77 for the pretest and 0.81 for the post-test of the study. After treatment phase of the study, questions for interview were structured to gather insights from students regarding the use of ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot. Participants in both experimental groups provided their viewpoints and opinions about ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot.

3.5. Data Analysis and Coding Procedure

To answer the first research question, the researchers ran an analysis of covariance (ACNOVA) procedure to detect the variances between groups, due to the use of the pretest as the covatiate. Before running the statistical analysis, we checked the underlying assumptions and ensured they were satisfactorily met, as explained in the results section below.

As for the second research question, five participants were selected from each experimental (ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot) group as volunteers to participate in the follow-up interview. Immediately after the posttest administration, those volunteers sat in a class and the second researcher began to ask them the interview questions, as listed in the research instruments section. The interview responses regarding learners’ perceptions of ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot were thematically analyzed (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was chosen for analyzing interview data in this study as it provides a flexible, data-driven approach that allows themes to naturally emerge from participants’ responses, ensuring an authentic and nuanced understanding of their experiences with AI tools. This method is particularly well-suited for exploring the complex perceptions and interactions of EFL learners, enhancing the credibility and depth of the findings, and aligning well with the exploratory nature of the research questions (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The interviews were audiotaped and then transcribed to be coded.

As shown in Table 2, a comprehensive guide was offered through the six phases of analysis for interview data, complemented by examples to illustrate the process (Braun & Clarke, 2006). It is essential to understand that qualitative analysis guidelines were not rigid rules but flexible principles that should be adapted to suit the specific research questions and data. Additionally, the analysis was not a straightforward progression from one phase to another but rather a recursive process, involving continuous back-and-forth movement through the phases as needed.

TABLE 2. Phases of inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 87)

| Phase | Description of the process | |

| 1. | Familiarizing yourself with your data: | Transcribing data (if necessary), reading and re-reading the data, noting down initial ideas. |

| 2. | Generating initial codes: | Coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set, collating data relevant to each code. |

| 3. | Searching for themes: | Collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. |

| 4. | Reviewing themes: | Checking if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts (Level 1) and the entire data set (Level 2), generating a thematic ‘map’ of the analysis. |

| 5. | Defining and naming themes: | Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story the analysis tells, generating clear definitions and names for each theme. |

| 6. | Producing the report: | The final opportunity for analysis. Selection of vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature, producing a scholarly report of the analysis. |

The coding was done based on Adu’s (2019) coding method. The researchers followed interpretation-focused coding in which they involved in a process of meaning-making, during which the generated codes reflected their comprehension and interpretation of the data. In employing this approach, the researchers drew upon their existing knowledge and experiences to influence the coding process. Given that the primary emphasis of the study was on IMMs, the researchers categorized codes under five subcategories of IMMs—hedges, boosters, engagement markers, attitude markers, and self-mentions. That is, when participants talked about their perceptions of utilization of ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot, they focused on realizing hedges, boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions and engagement markers. Both researchers read the entire data and coded them indepenntly. When they disagreed on a code, a third coder, familiarized with qualitative data analysis and well versed in metadiscourse, was invited in to do the coding. The results of intercoder relaibilty, using Cronbach’s alpha was .91. The rest of the discrepancies were discussed until full agrememnt was reached.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Investigation of the first research question

Regarding this research question, a one-way ANCOVA was performed to differentiate the results of the realization of IMMs in post-test for three groups, namely ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, and control group. Test of normality was conducted and data appeared to be normal for post-test (Pallant, 2020). Sig. value of Kolmogorov-Smirnova for posttest was checked (KS90 = .052, p > .05) (table 3).

TABLE 3. Tests of normality for post-test

| Posttest | Kolmogorov-Smirnova | Shapiro-Wilk | ||||

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |

| .089 | 90 | .076 | .974 | 90 | .065 | |

TABLE 4. Levene’s test of equality of error variancesa

| Dependent Variable: Posttest | |||

| F | df1 | df2 | Sig. |

| 1.217 | 2 | 87 | .301 |

a. Design: Intercept + Pretest + Group

To check for the assumption of equal variances, the data were evaluated. Levene’s test result (F (2,87) = 1.217, p ˃ .05) indicated that this assumption was upheld (Table 4).

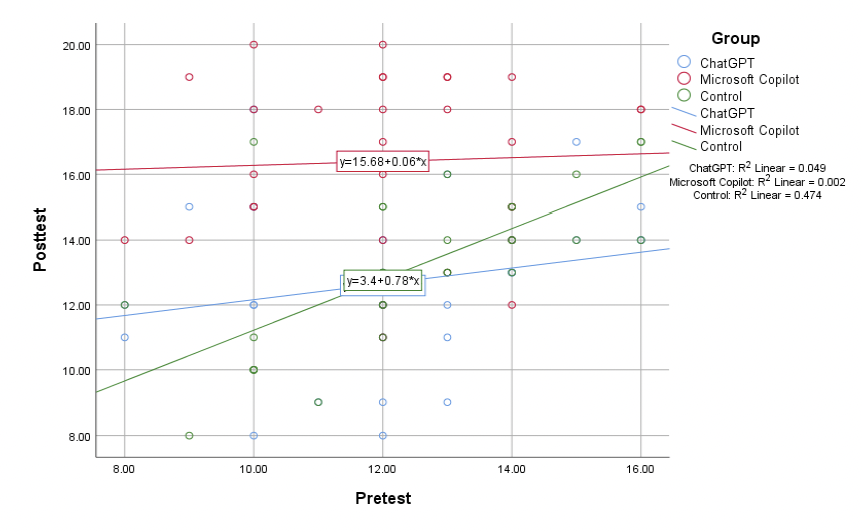

Considering the assumption of linearity, the researchers found that a curvilinear relationship was not proven for each group. Therefore, linearity assumption was met (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Linearity scatterplot for each group

The other assumption, homogeneity of regression slopes, was also satisfied (p > 0.5) (Table 5).

TABLE 5. Tests of between-subjects effects

| Dependent Variable: Posttest | ||||||

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

| Corrected Model | 339.577a | 5 | 67.915 | 12.401 | .000 | .425 |

| Intercept | 236.964 | 1 | 236.964 | 43.270 | .000 | .340 |

| Group | 61.027 | 2 | 30.514 | 5.572 | .005 | .117 |

| Pretest | 51.837 | 1 | 51.837 | 9.465 | .003 | .101 |

| Group * Pretest | 36.473 | 2 | 18.237 | 3.330 | .041 | .073 |

| Error | 460.023 | 84 | 5.476 | |||

| Total | 18608.000 | 90 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 799.600 | 89 | ||||

a. R Squared = .425 (Adjusted R Squared = .390)

Table 6 displays an overview of the descriptive statistics for the scores across the three groups: ChatGPT group (M = 12.70, SD = 2.52), the Microsoft Copilot group (M = 16.40, SD = 2.58), the control group (M = 13.10, SD = 2.45). To decide the significance of these variations in the posttest, ANCOVA was employed.

TABLE 6. Descriptive statistics for IMMs in argumentative writing in the posttest

| Dependent Variable: Posttest | |||

| Group | Mean | Std. Deviation | N |

| ChatGPT | 12.7000 | 2.52095 | 30 |

| Microsoft Copilot | 16.4000 | 2.58110 | 30 |

| Control | 13.1000 | 2.45441 | 30 |

| Total | 14.0667 | 2.99738 | 90 |

The results of ANCOVA (Table 7) indicated that after adjusting for the initial differences on the pretest, statistically significant differences were seen among the groups on the posttest (F(2, 86) = 22.23, p < .05, partial eta squared = .34).

TABLE 7. ANCOVA post-test results on IMMs in argumentative writing across groups

| Dependent Variable: Posttest | ||||||

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

| Corrected Model | 303.103a | 3 | 101.034 | 17.501 | .000 | .379 |

| Intercept | 234.935 | 1 | 234.935 | 40.694 | .000 | .321 |

| Pretest | 55.703 | 1 | 55.703 | 9.649 | .003 | .101 |

| Group | 256.698 | 2 | 128.349 | 22.232 | .000 | .341 |

| Error | 496.497 | 86 | 5.773 | |||

| Total | 18608.000 | 90 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 799.600 | 89 | ||||

a. R Squared = .379 (Adjusted R Squared = .357)

To locate the differences between the three groups, pairwise comparisons were carried out (Table 8) to assess the significant differences in the realization of IMMs in argumentative writing across the three groups. The findings indicated that the difference was statistically significant (p < .05) in employing IMMs between the ChatGPT group and Microsoft Copilot group, with the latter demonstrating superior performance. Furthermore, the difference between ChatGPT group and control group was not statistically significant (p > .05). Overall, Microsoft Copilot group outperformed the other two groups in realizing IMMs in their argumentative writing.

TABLE 8. Pairwise comparisons for post-test scores of IMMs in argumentative writing across groups

| Dependent Variable: Posttest | ||||||

| Tukey HSD | ||||||

| (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Difference (I-J) |

Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| ChatGPT | Microsoft Copilot | -3.70000* | .65049 | .000 | -5.2511 | -2.1489 |

| Control | -.40000 | .65049 | .812 | -1.9511 | 1.1511 | |

| Microsoft Copilot | ChatGPT | 3.70000* | .65049 | .000 | 2.1489 | 5.2511 |

| Control | 3.30000* | .65049 | .000 | 1.7489 | 4.8511 | |

| Control | ChatGPT | .40000 | .65049 | .812 | -1.1511 | 1.9511 |

| Microsoft Copilot | -3.30000* | .65049 | .000 | -4.8511 | -1.7489 | |

*. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

4.2. Investigation of the second research question

Grammarly and teacher feedback were two types of feedback that were given to the students in this study. On the one hand, Grammarly deals with three writing aspects: Diction, Language Use, and Mechanics. On the other hand, teacher feedback may cover the five writing aspects: Content, Organization, Diction, Language Use, and Mechanics. These types of feedbacks were given both in the first and second experimental groups.

The second research question sought to examine the learners’ perception of the effectiveness of utilizing ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot in realizing IMMs. The themes are presented in Table 9. The following two sample extracts show what the leaners in the experimental groups thought about using the chatbots. For example, in Extract 1, one of the language learners in the Microsoft Copilot group (participant 2) expresses his points of view concerning the several advantages Microsoft Copilot can offer and the ways it can be superior to ChatGPT.

Extract 1: The manner in which Microsoft Copilot assisted us in getting necessary information and organizing our thoughts about IMMs was quite remarkable. I had not previously recognized its potential as a metadiscourse learning companion. It’s, in fact, superior to ChatGPT in a manner that it provided different choices, and you can also learn from them other than your own prompts. The best part of Microsoft Copilot was that the response was so clear and comprehensible. It delved into the details regarding the provided prompts.

In the second extract, another language learner in the ChatGPT group (participant 6) explained that although ChatGPT is helpful and supportive, it was not an accurate detector of the IMMs he was looking for.

Extract 2: I felt that it supported our writing and metadiscourse realization. However, the responses to the prompts were incomplete. It provided a short list of IMMs. More explanations were needed. Sometimes, misunderstanding happened. It could not find IMMs in a given paragraph very accurately. No more choices, other than the given prompts, were given through ChatGPT. I think the usual class by a teacher may be better for students to realize IMMs in argumentative writing.

TABLE 9. ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot coded focus group data

| Themes/sub-themes | AI-powered chatbot | Codes |

| Hedges | ChatGPT | Positive perception Creation of a short definition Negative perception Less comprehensible and applicable No clear examples |

| Microsoft Copilot | Positive perception

Providing more ideas on the marker Clear definitions and responses Sensitive to implicit hedges Negative perception None |

|

| Boosters | ChatGPT | Positive perception

Creation of strong examples Negative perception Less creativity in clarifying metadiscourse Examples in isolation not in a context |

| Microsoft Copilot | Positive perception

Introducing a reliable source Finding the marker in complex sentences Appropriate use of marker in a sentence Negative perception Promoting dependency on machine |

|

| Attitude markers | ChatGPT | Positive perception

Good indicator of this marker Negative perception No ability to find the marker in a text Reduction of attention to the marker Lack of a complete concept of the marker |

| Microsoft Copilot | Positive perception Promoting collaboration in realizing the marker Being focused on the marker Providing extra examples and prompts related to the marker Negative perception Giving lots of explanation and sometimes boring |

|

| Self-mentions | ChatGPT | Positive perception

Creation of a clear definition Negative perception Unreliable source of marker detection Creation of confused examples in a sentence |

| Microsoft Copilot | Positive perception

Providing more explanation to make it compressible Being easy to understand the marker Providing argumentative paragraph with this marker Negative perception None |

|

| Engagement markers | ChatGPT | Positive perception Reliable source for this marker Negative perception Inappropriate use of the marker Reduction of attention to the marker Lack of a complete concept of the marker |

| Microsoft Copilot | Positive perception

Promoting motivation in realizing the marker Inspiring exercises Introducing more other prompts related to the marker Negative perception None |

Overall, the results of data taken from interview were in parallel with quantitative data analysis. Microsoft Copilot assisted the learners in employing and realizing IMMs in argumentative writing. Participants in Microsoft Copilot group showed their satisfaction. Participants highlighted the role of Microsoft Copilot in learning metadiscourse in general and IMMs in particular. They asserted that Microsoft Copilot gave them appropriate choices of IMMs in writing argumentative writing to make it convincing.

5. DISCUSSION

This section provides a comprehensive analysis and interpretation of the study’s findings. First, we summarize the key results and their alignment with existing literature on the impact of AI-based tools on writing abilities. Then, we delve into a comparative analysis of ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot, highlighting specific instances where one outperformed the other. We also explore the theoretical frameworks, as discussed in the review of lieterure, that support our findings, including feedback theory. Finally, we discuss the practical implications of our study for educators and learners, addressing the unique advantages and user experiences offered by Microsoft Copilot, and conclude with a consideration of the study’s limitations and suggestions for future research.

While both ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot exhibited enhanced employment of IMMs in writing abilities during the specified timeframe, the participants’ performance in Microsoft Copilot group was markedly superior to that of their ChatGPT counterparts in the evaluation carried out after the treatment. The results align with those observed by scholars investigating the effect of AI-based tools on the writing abilities of university learners (Marzuki et al., 2023; Zhao, 2022). This study showed that Microsoft Copilot was better than ChatGPT in metadiscourse instruction, which is in conflict with Esfandiari and Allaf-Akbary’s (2024b) study, resulting in the contribution of ChatGPT to the learners in realizing IMMs. Esfandiari and Allaf-Akbary found that ChatGPT-based instruction was more beneficial in employing IMMs in argumentative writing. However, it is widely accepted that AI-powered tools can strengthen language learning in terms of writing abilities (Kohnke et al., 2023; Rudolph et al., 2023). For example, learners in the Microsoft Copilot group reported that the feedback provided was detailed and helped them understand their mistakes better, and Microsoft Copilot made it easier to see where they needed to improve their writing. These ponits illustrate the positive perceptions of the tool’s impact on the students’ writing skills. Additionally, we have expanded the comparative analysis between ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot. The detailed comparative analysis now includes specific instances where Microsoft Copilot outperformed ChatGPT, such as providing more contextual suggestions for improving IMMs.

Several factors underscoring the unique advantages and user experience offered by Microsoft Copilot are detected. One of the key aspects is Microsoft Copilot’s seamless integration with Microsoft Office applications like Word and Outlook, providing a familiar and user-friendly interface that students are already accustomed to, which reduces the learning curve and makes the tool more accessible (Scholl, 2024). This familiarity contributes to higher student preference and engagement. Additionally, Microsoft Copilot’s advanced algorithms deliver contextually relevant suggestions and feedback, which help students effectively use IM by suggesting appropriate transitions, hedges, and boosters that enhance the persuasiveness and clarity of their arguments (Esfandiari & Allaf-Akbary, 2024c). This targeted feedback aligns closely with the principles of effective feedback in language learning, as outlined by feedback theory, which emphasizes the importance of specific, timely, constructive, and actionable feedback in improving performance. Another significant advantage of Microsoft Copilot is its ability to provide real-time writing assistance, allowing students to receive immediate suggestions and corrections as they draft their essays. This real-time support is crucial in academic settings where time is often limited, and immediate feedback can significantly enhance the writing process (Campesato, 2024). Moreover, Microsoft Copilot’s customization features enable students to tailor the tool to their specific needs, providing a more personalized and effective writing assistant compared to more generic tools like ChatGPT. The positive user experience with Microsoft Copilot, combined with its ability to provide feedback that meets educational standards and expectations, further solidifies its preference among students. Additionally, Microsoft’s reputation for strong security and data privacy may instill more confidence in students and educational institutions, contributing to its widespread adoption (Miller, 2024).

The outcomes derived from the investigation of interview data revealed a generally favorable perception considering the influence of AI-based tools. This observation aligns with existing literature concerning learners’ viewpoints on the effects of AI-based tools on their writing practices (Yan, 2023). The generally favorable disposition can be attributed to the excitement surrounding the execution of AI chatbots within academic contexts. The results regarding the role of Microsoft Copilot in facilitating content generation are consistent with the claims made by Guo et al. (2022) and Marzuki et al. (2023). The results of our study indicated that a significant number of learners held positive views regarding Microsoft Copilot. This supports the results of Chen et al. (2020), which spotlighted educators’ recognition of the difficulties in learning and their openness to integrating AI-enhanced learning methodologies in their future instructional practices. Microsoft Copilot presents significant advantages for individuals engaged in L2 learning by facilitating the generation of precise and contextually relevant points. Through its provision of instantaneous suggestions and corrections, Microsoft Copilot aid learners in refining their linguistic abilities while deepening their comprehension of grammar and lexicon in a foreign language (Pym & Hao, 2024). Furthermore, the tools can deliver customized recommendations aligned with user preferences, thereby optimizing the learning experience and catering to specific requirements.

As the findings of the study show, Microsoft Copilot stands as a crucial resource for L2 learners aspiring to elevate their language proficiency. Microsoft Copilot serves as a valuable tool for helping EFL leaners learn IMMs in an L2 by delivering immediate suggestions and corrections during the writing process (Pan, 2024). This functionality enables users to broaden their knowledge of IMMs by presenting alternative terms or expressions in the desired language (Khadimally, 2022). Furthermore, Microsoft Copilot can offer metadiscourse recommendations that are contextually pertinent to the material being composed, thereby facilitating the learning of new IMMs within the correct context (Bowen & Watson, 2024). By leveraging the language support capabilities of Copilot, users can refine their metadiscourse realization skills and elevate their overall competence in an L2. Through consideration of prior knowledge and experience, AI can select tasks, activities and plan lesson in language learning (Vurdien & Chambers, 2024).

The fidnings can be explained in terms of feedback theory, which emphasizes the importance of providing specific, timely, and actionable feedback to improve performance. In our study, the AI chatbots, particularly Microsoft Copilot, provided immediate and detailed feedback on the use of IMMs. This immediate feedback acted as a critical support mechanism, helping learners internalize and apply IMMs effectively in their writing. The superior performance of the Microsoft Copilot group can be attributed to its ability to deliver precise and contextually relevant feedback. This aligns with feedback theory, which posits that effective feedback should be clear, specific, and given promptly to facilitate learning and improvement (Nassaji & Kartchava, 2024). The positive perceptions reported in semi-structured interviews suggest that learners found the detailed feedback from Microsoft Copilot highly beneficial, reinforcing their understanding and application of IMMs. The structured feedback helped learners focus on key aspects of their writing, making the necessary adjustments in real-time, thus enhancing their overall writing skills and proficiency in using IMMs.

The observed differences in the effectiveness of IMMs between Microsoft Copilot and Chat-GPT may be attributed to their underlying transformer model architectures. Microsoft Copilot is built on a sophisticated transformer model specifically designed to enhance language understanding and generation, optimized for tasks requiring nuanced language use, such as incorporating IMMs. This model effectively handles long-range dependencies and contextualizes information across sentences, generating coherent and contextually relevant IMMs (Esfandiari & Allaf-Akbary, 2024c). In contrast, ChatGPT, based on the advanced GPT-4 architecture, is a generalist model excelling in generating coherent texts across diverse topics but may not prioritize specific linguistic features like IMMs as effectively as specialized models (Roumeliotis & Tselikas, 2023). The composition of training data and frequency of updates also significantly impact the language generation capabilities of these AI models. Microsoft Copilot benefits from training on datasets rich in academic and argumentative texts, enhancing its ability to generate texts with effective IMMs. In contrast, Chat-GPT’s broader corpus may not prioritize these features as strongly. Additionally, Microsoft Copilot may receive more frequent updates focused on the latest academic and professional writing trends, further refining its capabilities (Minnick, 2025). Algorithmic enhancements, such as advanced techniques for improved contextual understanding and discourse modeling, contribute to Microsoft Copilot’s superior performance. Sophisticated feedback mechanisms within Copilot allow it to learn from user interactions, continuously refining its language generation capabilities over time (Stratton, 2024). These combined factors—model architecture, specialized training data, frequent updates, and algorithmic enhancements—may explain the superior performance of Microsoft Copilot in generating effective and contextually relevant IMMs compared to Chat-GPT.

Overall, the synergy between feedback theory and the practical application of GPT as a writing assistant, as exemplified by Microsoft Copilot, highlights the transformative potential of integrating effective feedback mechanisms with advanced AI tools to enhance language learning and writing processes, ultimately supporting students in achieving their academic goals.

5.1. Implications, Limitations, and Suggestions for Further Research

The results of this study have several implications for future teaching practices, particularly in the context of teaching metadiscourse in argumentative writing. Language educators can integrate AI tools like Microsoft Copilot into their curriculum to provide personalized feedback on the use of IMMs, helping learners understand the importance of these markers in structuring their arguments and engaging their audience. The use of AI in language instruction can also help identify areas where students struggle with metadiscourse and offer targeted interventions to address these challenges. Additionally, the educators should consider providing training to students on how to effectively use AI tools, ensuring that they can fully leverage the benefits of these technologies in their learning process. By incorporating AI-powered feedback, educators can enhance students’ awareness and usage of IMMs, ultimately improving the overall quality of their argumentative writing.

This research posits that AI-driven language learning can serve a vital function in fostering the educational experiences of EFL learners, thereby significantly advancing their language learning processes. These tools provide a more delightful and customized learning environment, which fosters and enthusiasm for ongoing language study. Platforms enhanced by AI, such as Microsoft Copilot, enable learners to apply language abilities at their own convenience and from various locations. This accessibility empowers learners to assume control over their educational trajectories, promoting a feeling of independence and self-control. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the great influence of AI-based language learning within EFL classrooms, particularly their capacity to create personalized and adaptive learning experiences. Interacting with these dynamic AI systems allows learners to receive immediate feedback, constructive assessments, and diverse sentence structures, all of which contribute to continuous improvement and enhance their confidence in using an L2 language.

By offering personalized feedback, these AI tools enable tailored instructional strategies, addressing specific learner needs and fostering critical writing skills through real-time feedback. Additionally, they streamline the assessment process, reducing educators’ workloads and allowing focus on interactive teaching. The integration of AI chatbots creates adaptive learning environments that offer continuous support, improving student motivation and outcomes. Furthermore, AI-driven insights aid educators’ professional development by identifying areas needing improvement, leading to more effective teaching practices. Overall, AI chatbots can revolutionize language instruction through personalized learning, efficient assessment, and continuous professional development.

This study is, however, susceptible to several limitations, including the use of a restricted sample size, the absence of a delayed posttest to assess learners’ understanding of IMMs, and a focus solely on IMMs rather than encompassing interactive metadiscourse as well. Additionally, all participants were drawn from a pool of individuals possessing advanced language proficiency. The research employed an interview to collect data regarding participants’ attitudes towards ChatGPT and Microsoft Copilot. Other methodologies, such as think-aloud protocols, could be employed to obtain more profound insights into learners’ perspectives.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The findings from the present study suggested that Microsoft Copilot may significantly contribute to improving IMMs in writing argumentative paragraphs. The results indicated that Microsoft Copilot group demonstrated higher levels of comprehension of IMMs in the posttest. The notable effects, along with learners’ positive views regarding these tools, can contribute a new dimension to the existing literature on AI-powered chatbots. The findings of the present study enhance and expand upon theories regarding feedback as a dialogic procedure, positioning Microsoft Copilot and ChatGPT as feedback applications that may be seamlessly incorporated into extensive writing courses. The results of the research indicated that the communication enabled by the chatbots throughout the writing process significantly enhance learners’ learning. This engagement positively affects learners’ approaches to seeking feedback, their responsiveness to it, and their ability to enhance their argumentative writing skills.

Based on the findings of the study, learner autonomy is one área AI tools such as copilot paly a key role in developing it. EFL learners can use them at their own pace to learn new language points, ask them to provide individulaised feedback, and adjust their learning following the feedback they receive. These processes will help learners to take resposibilty for their own learning, become accountable, and eventually achieve autonomy in learning. We recommend language teachers encourage language leanrers to use such tools and familairze them with the most frequently used AI tools, because teachers will not always be available to help them. Another área the results of the study may be useful is intelligent data-driven learning (Esfandiari & Allaf-Akbary, 2024c), because AI tools such as copilot are inteligent and based on large language moldes (LLMs) and can be particularly helpful in fostering writing abilities. EFL learners can use these tools to provide them with several authentic senstence examples, discover the rules by analysing such senetnces, and learn how a particular rule is naturally used in real-life sitautions. Language teachers can also utilize such tools to provide learners with sufficient natural input, exposing them to the language native-English speakers actually use.

Declaration of conflicting interest

There is no conflict of interest in this work.

7. FUNDING

This research received no external funding.

8. REFERENCES

Abdelrahim A. A. M., & Abdelrahim, M. A. M. (2020). Teaching and assessing metadiscoursal features in argumentative writing: A professional development training for EFL teachers. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 30, 70-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12264

Ädel, A. (2023). Adopting a ‘move’ rather than a ‘marker’ approach to metadiscourse: A taxonomy for spoken student presentations, English for Specific Purposes, 6(69), 4-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2022.09.001

Adu, P. (2019). A step-by-step guide to qualitative data coding. Taylor & Francis.

Ali, J. K. M., Shamsan, M. A. A., Hezam, T. A., & Mohammed, A. A. Q. (2023). Impact of ChatGPT on learning motivation: Teachers and students’ voices. Journal of English Studies in Arabia Felix, 2(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.56540/jesaf.v2

Allagui, B. (2023). Chatbot Feedback on students’ writing: Typology of comments and effectiveness. In O. Gervasi, B. Murgante, A. M. A. C. Rocha, C. Garau, F. Scorza, Y. Karaca, & C. M. Torre (Eds.), International conference on computational science and its applications (pp. 377–384). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37129-5_31

Amirjalili, F., Neysani, M., & Nikbakht. A. (2024). Exploring the boundaries of authorship: a comparative analysis of AI-generated text and human academic writing in English literature. Frontiers in Education, 9(2), 76-98. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1347421

Barrot, J. S. (2023). Using ChatGPT for second language writing: Pitfalls and potentials. Assessing Writing, 57, 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2023.100745

Bautista, J. (2024). Chat GPT for students: How to become an A+ student using Chat GPT. Benjamin Bautista.

Bowen, J. A., & Watson, C. E. (2024). Teaching with AI: a practical guide to a new era of human learning. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Campesato, O. (2024). GPT-4 for developers. Mercury Learning and Information.

Chen, X., Xie, H., Zou, D., & Hwang, G. (2020). Application and theory gaps during the rise of artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1(4), 100002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100002

Clark, V. E. (2024). First language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Dai, W., Lin, J., Jin, F., Li, T., Tsai, Y., Gasevic, D., & Chen, G. (2023). Can large language models provide feedback to students? A case study on ChatGPT. IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies. https://doi.org/10.35542/osf.io/hcgzj

El-Dakhs, D. A. S., Yahya, N., & Pawlak, M. (2022). Investigating the impact of explicit and implicit instruction on the use of interactional metadiscourse markers. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 44(7), 2-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-022-00175-0

Escalante, J., Pack, A. & Barrett, A. (2023). AI-generated feedback on writing: insights into efficacy and ENL student preference. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20, Article 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00425-2

Esfandiari, R., & Allaf-Akbary, O. (2024a). The role of learning-oriented language assessment in promoting interactional metadiscourse in ectenic and synoptic EFL learners. Journal of Modern Research in English Language Studies, 11(3), 181-206. https://doi:10.30479/jmrels.2024.19777.2305

Esfandiari, R., & Allaf-Akbary, O. (2024b). The role of ChatGPT-based instruction and flipped language learning in metadiscourse use in EFL learners’ argumentative writing and their perceptions of the two instructional methods. Teaching English as a Second Language Quarterly (Formerly Journal of Teaching Language Skills), 43(3), 45-65. https://doi: 10.22099/tesl.2024.49975.3277

Esfandiari, R., & Allaf-Akbary, O. (2024c). Assessing interactional metadiscourse in EFL writing through intelligent data-driven learning: the Microsoft Copilot in the spotlight. Language Testing in Asia, 14, Article 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-024-00326-9

Esfandiari, R., & Khatibi, Z. (2022). A cross-cultural, cross-contextual study of interactional metadiscourse in academic research articles: An interpersonal approach. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 40(2), 227-242, https://doi: 10.2989/16073614.2022.2056064

Gao, C. A., Howard, F. M., Markov, N. S., Dyer, E. C., Ramesh, S., Luo, Y., & Pearson, A. T. (2023). Comparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to original abstracts using an artificial intelligence output detector, plagiarism detector, and blinded human reviewers. NPJ Digital Medicine, 75(6), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00819-6

Gordon, C. (2024). Intertextuality 2.0: Metadiscourse and meaning-making in an online community. Oxford University Press.

Guo, K., Wang, J., & Chu, S. K. W. (2022). Using chatbots to scaffold EFL students’ argumentative writing. Assessing Writing, 54, 100666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2022.100666

Ho, V., & Li, C. (2018). The use of metadiscourse and persuasion: An analysis of first year university students’ timed argumentative essays. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 33(2), 53-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2018.02.001

Holmes, W., Persson, J., Chounta, I. A., Wasson, B., & Dimitrova, V. (2022). Artificial intelligence and education: A critical view through the lens of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Council of Europe.

Huang, A. Y. Q., Lu, O. H. T., & Yang, S. J. H. (2023). Effects of artificial intelligence–enabled personalized recommendations on learners’ learning engagement, motivation, and outcomes in a flipped classroom. Computers & Education, 194(2), 104684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104684

Huang, F., & Zou, B. (2024). English speaking with artificial intelligence (AI): The roles of enjoyment, willingness to communicate with AI, and innovativeness. Computers in Human Behavior, 159(2), 108355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108355

Huang, Q., Liu, Y., Chen, S., & Zhao, M. (2024). Generative AI acceptance, teachers’ enthusiasm, and learners’ self-efficacy: Impact on EFL learners’ well-being. Journal of Language and Education Research, 38, 75-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12770

Hyland, K. (2019). Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing (2nd edition). Continuum.

Hyland, K., & Jiang, F. K. (2022). Metadiscourse choices in EAP: An intra-journal study of JEAP. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 60(3), 101-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101165

Khadimally, S. (2022). Applications of machine learning and artificial intelligence in education. IGI Global.

Kim, J., Lee, H., & Cho, Y. H. (2022). Learning design to support student-AI collaboration: Perspectives of leading teachers for AI in education. Education and Information Technologies, 27(5), 6069–6104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10831-6

Kim, J., Yu, S., Detrick, R., & Li, N. (2024). Exploring students’ perspectives on generative AI-assisted academic writing. Education and Information Technologies, 2(34), 1-36 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12878-7

Kohnke, L., Moorhouse, B. L., & Zou, D. (2023). ChatGPT for language teaching and learning. RELC Journal, 54(2), 537-550. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882231162868

LaRue Keeley, K. (2024). AI Applications and Strategies in Teacher Education. Information Science Reference. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-5443-8

Lee, S. S., Li, N., & Kim, J. (2023). Conceptual model for Mexican teachers’ adoption of learning analytics systems: The integration of the information system success model and the technology acceptance model. Education and Information Technologies, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10639-023-12371-7

Li, Z., & Xu, J. (2020). Reflexive metadiscourse in Chinese and English sociology research article introductions and discussions. Journal of Pragmatics, 159(2), 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.02.003

Lim, G. S. (2011). The development and maintenance of rating quality in performance writing assessment: A longitudinal study of new and experienced raters. Language Testing, 28(4), 543-560.

Lo, C. K., Yu, P. L. H., Xu, S., Ng, D. T. K., & Jong, M. S. Y. (2024). Exploring the application of ChatGPT in ESL/EFL education and related research issues: a systematic review of empirical studies. Smart Learning Environments, 11(50), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00342-5

Mackey, A. (2020). Interaction, feedback and task research in second language learning methods and design. Cambridge University Press.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2023). Current approaches in second language acquisition research: A practical guide. Wiley.

Mahapatra, S. (2024). Impact of ChatGPT on ESL students’ academic writing skills: A mixed methods intervention study. Smart Learning Environment, 11, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00295-9