Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation Vol. 11. No. 1. June 2025 - pp. 134-149 - ISSN: 2444-2925

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.111.2025.20665

Relationship between knowledge, perception of competence and teachers’ performance against cyberbullying

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.1. INTRODUCTION

Cyberbullying is reported as an aggressive, intentional act carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or her-self (Smith et al., 2008). Although the prevalence rate varies from country to country and also depends on the measurement instruments, overall, according to the latest data in the European Union (Cosma et al., 2024), 15% of adolescents (around 1 in 6) have experienced cyberbullying, with the rates closely aligned between boys (15%) and girls (16%). This represents an increase over 2018, from 12% to 15% for boys and 13% to 16% for girls. Although most current studies analyze cyberbullying at the secondary education stage, it has been shown that the roles of cybervictim and cyberbully can arise from the primary education stage, and teacher training and collaboration between families and the school is necessary (Chicote-Beato et al., 2024; Flores et al., 2020).

Of the protective factors identified to decrease the likelihood of cyberbullying include individual factors such as higher self-esteem, strong ties at the family level, a high degree of emotional intelligence, and environmental factors such as residence in safer neighborhoods and a positive school climate including teacher involvement (Kowalski et al., 2019). In this sense, there is a clear gap in the scientific literature when it comes to studying variables that might predict positive teacher involvement in cyberbullying cases. Although studies have been developed that analyse cyberbullying in relation to teachers, most of them focus on studying the perception that teachers have of this phenomenon (Compton et al., 2014; Giménez-Gualdo et al., 2018; Gradinger et al., 2017; Green et al., 2016; Huang & Chou, 2013; Mishna et al., 2020; Monks et al., 2016; Redmond et al., 2018; Samara et al., 2020; Sigal et al., 2012; Yot-Domínguez et al., 2019). To a lesser extent, teacher performance in the face of cyberbullying has been studied (Macaulay et al., 2018; Nappa et al., 2020), teacher knowledge of cyberbullying (Campbell, et al., 2018; Redmond et al., 2020) and even the success of some programmes for teachers to improve coping with cyberbullying has been investigated (Del Rey et al., 2019; Guarini et al., 2019), however, little is known about predictors that might influence teachers’ encouragement to take action when they observe or are alerted to cyberbullying at school. In this regard, some studies that have focused on analysing the victim’s perspective show that not all teachers react to cyberbullying (Chaves et al., 2020; Giménez et al., 2018).

It is now known that school climate is related to cyberbullying, a negative climate, a lower sense of belonging to the school by students, increases the likelihood of participating as a bully (Varela et al., 2018; Williams & Guerra, 2007; Wong et al., 2014). Within the school climate, the teacher-student relationship has also been investigated as a protective factor, positive relationships in schools, including school staff in fostering them, help to build a more protective environment for students, however, an adequate level of knowledge about cyberbullying among teachers is necessary for their support to be effective (Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2019; Varela et al., 2018).

Given this lack of empirical research to understand the importance of the teacher’s role in cases of cyberbullying, some studies have been emerging that shed light on the factors that influence teachers to intervene in these situations. Sardessai et al. (2021), based on the theory of planned behaviour, formulated by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980), find that attitude, understood as the degree of a person’s favourable or unfavourable evaluation of a behaviour, is the variable that best predicts teachers’ intention to intervene. Previously, another study suggested that coping with cyberbullying is positively correlated with high levels of teacher empathy (Olenik- Shemesh et al., 2019). However, other variables that could also predict a teacher’s intention to intervene in a cyberbullying case, such as subject matter knowledge or self-efficacy, remain unexplained (Sardessai et al., 2021).

It has recently been found that positive family involvement in cyberbullying cases can be predicted from the level of knowledge about cyberbullying, perceived competence or self-efficacy, risk adjustment and attribution of responsibility (Gohal et al., 2023; Martín-Criado et al., 2021). Understanding how people behave when faced with a challenge or problem is one of the frequent topics of study in psychology. In this sense, social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977) maintains that expectations of personal efficacy determine whether a coping behaviour will be initiated in the face of a problem, understanding self-efficacy as the beliefs that a person has about his or her abilities to perform an action. Numerous studies point to the self-efficacy variable as a significant predictor of behaviour (De Vries et al., 1988; Holloway & Watson, 2002; Schwarzer & Fuchs, 1996). The recent study by Maurya et al. (2023) aimed to study the relationship between parental self-efficacy, communication and cyber victimization and depression in a sample of youth in India. The results showed that young victims of cyberbullying improved their mental health as communication and parental self-efficacy increased. In this sense, the importance of the sense of self-efficacy in dealing with cyberbullying situations is observed. Similarly, considerable research reveals the important role of risk perception in human behaviour (Arezes & Miguel, 2005). The term risk can be defined as the possibility of an undesirable state of reality occurring because of natural events or human activities (Rohrmann & Renn, 2000) and in the social sciences, people’s views on risk are often referred to as risk perception. Precisely the fear of that perceived risk predisposes people to act, motivating them to seek protective measures, as maintained by the theory of protective motivation (Rogers, 1975). In turn, responsibility, understood as the demand both to others and to oneself of a response to an interpellation (Crespo & Freire, 2014), has been extensively studied by social psychology. Attributing and assuming responsibility are reciprocally related processes, as can be extracted from Heider’s (1958) theory of attribution, all this with the aim of developing coping strategies. Despite the strategies, which in some cases are implemented, most teachers point out the lack of specific training to intervene (Cerezo & Rubio, 2017), and even to detect cyberbullying even when it affects students in their own classrooms (Montoro & Ballesteros, 2016). In this sense, greater involvement, specific training and intervention of teachers is necessary (Bevilacqua et al., 2017), as well as their training and planning to be able to intervene in the face of cyberbullying (Giménez-Gualdo et al., 2018; Nocentini et al., 2015).

1.1. The present study

Although previous research has shown the relationship between cyberbullying and several variables such as the perception of competence and knowledge in families in cyberbullying situations (Ho et al., 2029; Martín-Criado et al., 2021), there are not many studies that study exactly the relationship between cyberbullying and these variables in teachers. Therefore, the present research pursues two objectives: (1) to study the relationship between the variable’s knowledge of cases, perception of competence and teachers’ performance in cases of cyberbullying; and (2) to analyse the predictive capacity of knowledge and perception of competence on performance in cases of cyberbullying in a sample of teachers.

Based on the review of previous research, we expect to find differences in the variables studied. Specifically, a statistically significant relationship is expected to be found between the degree of knowledge and action in cases of cyberbullying (hypothesis 1). With regard to perceived competence, a statistically significant and positive relationship is expected to be found between competence and cyberbullying behaviour (hypothesis 2). Finally, teachers’ knowledge and perceived competence are expected to be significant predictors of cyberbullying performance (hypothesis 3).

2. MATERIAL AND METHOD

2.1. Participants

A total of 295 teachers from different educational levels participated in the study, of which 37 were eliminated due to errors in their responses to the questionnaire, after the use of a non-probabilistic sampling by convenience sampling. Therefore, the final research sample consisted of 258 active teachers in a graduate course in educational technology and digital competencies, using non-probability sampling by accessibility to select the sample. The average age of the teachers ranged from 29 to 65 years (M = 44.61; SD = 12.25) and the gender distribution was 52% female and 48% male. Using the Chi-square Test of Homogeneity of frequencies distribution, it was proved that there were no statistically significant differences among Sex x Age (χ2 = 3.15; p = 0.37). The country of origin of the teachers was as follows: Spain (20.1%), Ecuador (31.8%) and Colombia (42.6%). All teachers work in different educational stages, from Early Childhood Education (0-6 years) to Higher Education (17 years or more), with the Secondary Education stage (12-16 years) being the most numerous (46.1%), followed by Primary Education (6-12 years), representing 26%. Of the total number of teachers in the sample, 68.2% are working for more than 4 years, 47.7% of the teachers have more than 6 years of experience, but there are also teachers who are working between 1 and 3 years (19.4%) and even some less than one year (12.4%).

TABLE 1. Distribution of the number of teachers surveyed according to country of residence and specialisation

| Teaching specialisation | Country of residence | ||||||||

| USA | Peru | Spain | Colombia | Ecuador | Belgium | Switzerland | Chile | Dominican Rep. | |

| Students 0-6 years old | - | - | 11 | 3 | 9 | 2 | - | 1 | - |

| Students 6-12 years old | - | 1 | 27 | 22 | 17 | - | - | - | - |

| Students 12-16 years old | 1 | 2 | 7 | 64 | 42 | - | - | - | 3 |

| Students 17 years and older | - | - | 7 | 21 | 14 | - | - | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 1 | 3 | 52 | 110 | 82 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| % Total Participants | 0.4% | 1.2% | 20.1% | 42.6% | 31.8% | 0.8% | 0.4% | 1.5% | 1.2% |

2.2. Instruments

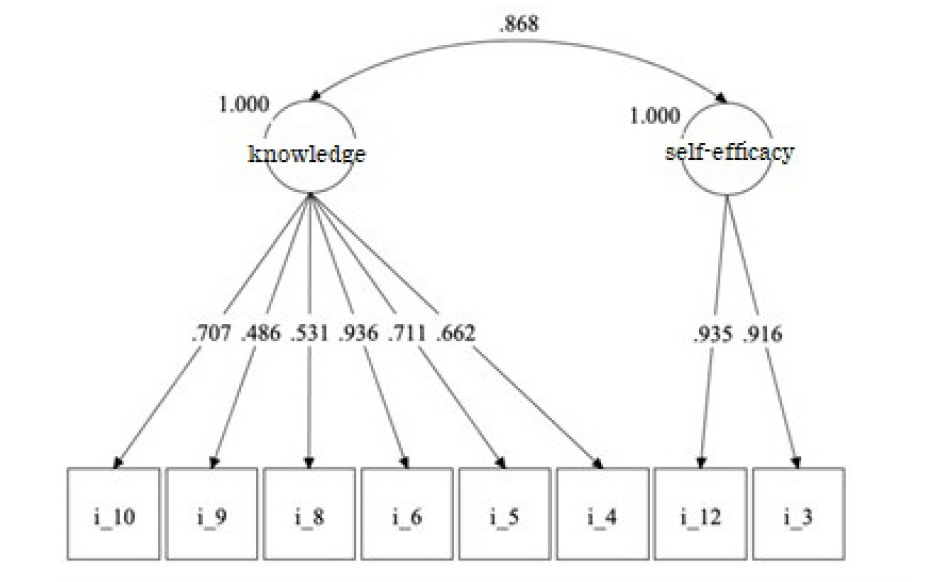

The purpose of the research is to analyse the predictive ability of the variables knowledge and perceived competence of teachers on their performance in cases of cyberbullying. Given that cyberbullying is a relatively recent phenomenon, few measurement instruments have been developed that address teachers’ perceptions, in this sense, an ad hoc questionnaire is designed based on similar research (Li, 2008) to examine the teachers’ perspective on cyberbullying. The questionnaire consists of a total of 8 items relating to the overall construct, although divided into two main dimensions: knowledge about cyberbullying and self-efficacy or competence. The questions referring to the degree of knowledge of cyberbullying were the following: 1: Did you receive training on cyberbullying during your studies? What was involved?, 2: Have you received training on coexistence? What was involved?, 3: Have you received training on cyberbullying at school? What was involved?, 4: Does your school have a Code of Coexistence? What was involved? and 5: Does your school have a protocol against bullying? What was involved?, 6: Does your school have a protocol in case of cyberbullying? What was involved? The two questions referring to perceived competence and self-efficacy were the following: 1: Do you see yourself as needing specific training on cyberbullying? Why?, and 2: Do you know how to deal with cyberbullying in your school? What was involved? The questionnaire has been approved by the Scientific-Ethical Committee of the University with the code PI:035/2021. The questions were formulated in an open-ended manner so as not to condition the answers. These were analysed according to a system of categories developed from the data. The reliability of the category system was determined by the independent scoring of the categories by two judges. The inter-rater reliability of the categories was calculated using the Kappa index of inter-rater reliability (Cohen, 1960), applied to each category. Agreement was quite high on all questions, with means ranging from .84 to .99 in the different categories. It should be noted that the questionnaire was validated by a committee of experts prior to its application. Figure 1 shows the different items.

FIGURE 1. Questionnaire items

2.3. Procedure

Once the sample of teachers had been selected, a meeting was held to inform them of the objectives of the study, ask their permission, explain the evaluation instruments, and thank them for their collaboration in answering the questionnaire, which was completed voluntarily and collectively. Anonymity of study participants was ensured by assigning identification numbers to the answer sheets. Researchers were also available during the tests to clarify any doubts and to confirm the correct administration of the questionnaire. Compliance with the test was ensured, taking an average of 50 minutes to complete the test. This research complies with the ethical principles for the conduct of research involving human subjects according to the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Assembly.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Firstly, an exploratory factor analysis was carried out on the 8 items of the questionnaire applied to the sample of teachers, and it was found that the items were grouped into 2 factors: knowledge about cyberbullying and perception of competence and self-efficacy. Once the model was estimated, confirmatory factor analysis was carried out, which made it possible to assess the validity and reliability of each item of the questionnaire. Once it was verified that the estimated fit function reached the minimum, the quality of the model was analysed. To measure the goodness-of-fit, different indices were calculated, which report the extent to which the structure defined by the model parameters reproduces the covariance matrix of the sample data (CFI = .93, RMSEA = .005, GFI = .90).

For the analysis of the relationship between the categorical variable teacher performance and the rest of the variables, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used, since these, in addition to being categorical variables, do not comply with the assumption of normality (Powers & Xie, 2000). The interpretation of Spearman’s coefficient ranges from -1 to +1, indicating negative or positive associations respectively, 0 zero, meaning no correlation, but not independence. The interpretation of the Spearman correlation coefficient values follows the following criteria (and considering absolute values): between 0 and .10: non-existent correlation; between .10 and .29: weak correlation; between .30 and .50: moderate correlation; and between .50 and 1: strong correlation.

Secondly, a logistic regression analysis was carried out using the forward stepwise procedure following the Wald statistic to assess the predictive capacity of the study variables on acting in the face of cyberbullying. The variable “action against cyberbullying” (yes/no) by teachers was dichotomized based on the answers given to the questions. In this case, the probability of the event occurring (acting against cyberbullying) was analysed using the Odds Ratio (OR), which is interpreted as follows: if the OR is greater than one, for example 2, for every time the event occurs in the presence of the independent variable, it will occur two times if this variable is present. Conversely, if the OR is less than one, e.g. 0.5, the probability of the event occurring in the absence of the independent variable will be greater than in its presence (Aparisi et al., 2021). Nagelkerke’s R² was used to assess the quality of the proposed models and their fit, indicating the percentage of variance explained by the model (Nagelkerke, 1991) and the percentage of cases correctly classified by the model or the predicted effectiveness.

Finally, for the static analysis, we used the program SPSS version 26.0.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Differences in teachers’ knowledge, perceived competence, and performance against cyber-bullying cases

As can be seen in Table 2, there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between the variable teacher performance in cyberbullying cases and knowledge of cyberbullying cases (p < .05), with the intensity of the association between the variables being weak. In addition, there is also a positive and statistically significant relationship between the variable’s teacher performance and perceived competence (p < .05), with a weak association between the variables. Finally, there is also a positive and statistically significant relationship between the variable’s teacher knowledge of the cases and perception of competence, the intensity of the relationship between the variables being moderate.

TABLE 2. Results derived from Spearman’s correlation between the performance variables

| Performance | Knowledge | Perception of competence | |||

| Correlation coefficient | 1 | .21** | .14* | ||

| Performance | Sig. (bilateral) | . | .00 | .02 | |

| N | 258 | 258 | 258 | ||

| Correlation coefficient | .21** | 1 | .36** | ||

| Spearman’s Rho | Knowledge | Sig. (bilateral) | .00 | . | .00 |

| N | 258 | 258 | 258 | ||

| Perception of competence | Correlation coefficient | .14* | .36** | 1 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .02 | .00 | . | ||

| N | 258 | 258 | 258 | ||

Note. **. Correlation is significant at the .01 level. *. Correlation is significant at the .05 level.

3.2. Predictive ability of teachers’ knowledge and perceived competence in cyberbullying behaviour

Two predictive models were obtained from the results of the logistic regression analysis from teachers’ performance in cyberbullying cases based on knowledge and perception of their competence (Table 3), each of them correctly classifying 79.4% of the cases (χ2 = 20.93; p = .00) and 78.2% (χ2 = 12.21; p = .00), respectively. The fit value (R2 Nagelkerke) of both models was .12 and .07, respectively. Odds Ratio (OR) indicate that teachers are 57% more likely to act on cyberbullying cases as their score on the knowledge scale increases by one unit and 3.0 times more likely to act on cyberbullying cases as their score on the perceived competence variable increases by one unit.

TABLE 3. Results derived from binary logistic regression for the probability of acting on cyberbullying cases

| Model | Predictor variable | B | E.T. | Wald | p | OR | I.C. 95% |

| Performance | Knowledge | . 45 | .10 | 19.15 | .00 | 1.57 | 1.28-1.93 |

| Constant | -2.45 | .33 | 53.26 | .00 | .08 | ||

| Perception of competence | 1.09 | .31 | 11.92 | .00 | 3.00 | 1.60-5.60 | |

| Constant | -2.60 | .43 | 36.06 | .00 | .07 |

Note. B = coefficient; S.E. = standard error; p = probability; OR = odds ratio; C.I. = 95% confidence interval

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was twofold. On the one hand, to study the relationship between the variable’s knowledge of cases, perception of competence and teachers’ performance in cases of cyberbullying; and on the other hand, to analyse the predictive capacity of knowledge and perception of competence on performance in cases of cyberbullying in a sample of teachers.

Specifically, a statistically significant relationship is expected to be found between the degree of knowledge and action in cases of cyberbullying (hypothesis 1). With regard to perceived competence, a statistically significant and positive relationship is expected to be found between competence and cyberbullying behaviour (hypothesis 2). Finally, teachers’ knowledge and perceived competence are expected to be significant predictors of cyberbullying performance (hypothesis 3).

The results obtained confirmed the three hypotheses of the study, as a positive and statistically significant relationship was obtained between the variables knowledge of cyberbullying cases, perception of competence and teachers’ performance. Furthermore, teachers’ knowledge of cyberbullying cases and their perceived competence were statistically significant predictors of teachers’ performance in cyberbullying cases. In line with previous studies, the results suggest that perceived competence and knowledge are key aspects of teachers’ performance in dealing with cyberbullying situations. In this regard, the study by Sardessai-Nadkarni et al. (2021) conducted with a sample of 402 teachers in India found that attitude, subjective norms, and perceived control over the situation explained 40.9% of the variance in intentions. Another study with 644 teachers in Israel showed that coping with cyberbullying is positively correlated with high levels of empathy, communication with students and self-efficacy (Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2019). The aim of the research of Hurtubise (2021) was to explore how teachers’ perceptions affected their likelihood of responding to varied cyberbullying scenarios (e.g., whether at home or school). Using multilevel modelling, this study investigated the relationships between teachers’ likelihood of response and key psychological factors and background characteristics, drawing on a convenience sample of 212 new and experienced teachers from England and the United States. Some of these factors include valence (severity of cyberbullying), expectancy (level of teacher self-confidence), and instrumentality (confidence in selected task). Findings show that valence, expectancy, and location of the cyberbullying were statistically significant predictors of teachers’ likelihood of response to situations of cyberbullying.

Regarding teachers’ knowledge about cyberbullying, other research warns, for example, of the importance of educating teachers about the need for cyberbullying prevention programmes (Hirschstein et al., 2007; Stauffer et al., 2012), or about school climate as a preventive variable (Cohen et al., 2009). In this sense, the study by Sidera et al. (2019), with a sample of 220 Pre-school and Primary School teachers, showed that 24.1% felt trained to deal with a situation of cyberbullying or traditional bullying, while the vast majority, 61.7%, were not sure they had the necessary skills and 14.2% admitted not feeling qualified to deal with a case of these characteristics. Consequently, the authors point out the importance of training teachers in the field of cyberbullying in terms of protocols and prevention programmes adapted to the reality of each school. A meta-analysis study of nineteen programs reviewed from 2700 selected articles on cyberaggression and cybervictimization showed that only programs involving interpersonal interactions and stakeholder (including teachers) action demonstrated superior program effectiveness (Lan et al., 2022). Therefore, teacher training should be based on educational programs that allow teachers to improve their understanding of the phenomenon of cyberbullying and be able to participate in the analysis of the causes, the extent of the consequences and the design of educational actions to address it (Barlett, 2017) and combine the implementation of strategies designed by experts with personalized actions according to the characteristics of the students and the school’s own culture (Del Rey et al., 2019). Recent research points to the importance of training teachers in social-emotional skills in the prevention of cyberbullying that impact the sense of self-efficacy when intervening when the problem manifests itself (Llorent & Núñez-Flores, 2024; Schoeps et al., 2018). Teachers with good social and emotional competencies will be able to develop the same competencies more effectively in their students, thereby preventing and reducing youth involvement in cyberbullying. In this sense, the study by Gabarda et al. (2022) concluded, in a sample of 653 university professors, the need for training in teacher competencies as well as the importance of the perception of the problem and the sense of self-efficacy in dealing with cyberbullying situations among students.

According to the third hypothesis of the study, perceived competence and self-efficacy is a significant predictor of the likelihood of cyberbullying intervention (Williford & Depaolis, 2016). According to Klassen and Tze (2014), self-efficacy, in the case of teachers, increases persistence in working with difficult students, influences teaching practices, as well as enthusiasm and commitment. The same is true for students: those who are confident in their competence in cyberbullying situations regulate their behaviour more successfully (Bussey et al., 2020). Teacher apathy, understood as the lack of interest or poor quality of the teacher’s performance, in relation to the phenomena of indiscipline, influences cyberbullying, as the research carried out by Ortega et al. (2013) also concludes. Many studies demonstrate that educators have knowledge of cyberbullying and perceive it as an issue in their schools, yet the majority of them lack the necessary skills and training to deal with it (Çırak & Demirkan, 2023; Eden et al., 2013; Fredrick et al., 2023; Tomczyk & Włoch, 2019).

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study provides relevant information on the phenomenon of cyberbullying and teacher involvement. In this sense, this research confirms the existence of statistically significant differences in teachers’ knowledge, perception of competence and performance in the face of cyberbullying.

In addition, teachers’ knowledge of the cases and perceived competence were statistically significant predictors of cyberbullying behaviour, as teachers with high scores on knowledge and perceived competence were more likely to act on cyberbullying. Developing resilience to cyberbullying involves conducting educational awareness programs (Ng et al., 2022), exercising self-efficacy, and utilizing technological knowledge (Achuthan et al., 2023). Acting effectively against cyberbullying in educational environments requires more digitally competent teachers in knowledge, skills (social and technical) and attitudes, especially as related to digital safety (Torres-Hernández & Gallego-Arrufat (2022). Teachers have a very important role in the education of students, not only at the academic level but also at the personal and emotional level, providing support. Teachers have the responsibility to show strong leadership within the educational system, to improve coexistence and to attend to all issues that occur in the school environment (Epstein & Kazmierczak, 2006). Likewise, educational institutions have the responsibility to prepare future professionals to be more competent in dealing with cyberbullying (Musset, 2010). Continuing education and training of future teachers in the university context will provide a valuable platform to promote school culture and attitudes in hopes of reducing cyberbullying situations.

5.1. Limitations and future lines of research

This research is not without some limitations. Firstly, although the technique used to select the sample guarantees its representativeness, it would be necessary to confirm the results found in this study at other educational levels (for example, in higher or university education). In this sense, it would be interesting to consider future longitudinal studies to verify the relationship between the variables in the long term. It is also worth bearing in mind the possible biases or limitations of teachers’ self-reported data, taking into account the effects of social desirability bias. In this sense, an in-depth qualitative evaluation of the responses would make it possible to control for such limitations. Secondly, it is important to consider the mediating effect of other personal variables (such as self-esteem, emotional intelligence), as well as social and family variables that may influence the relationship between cyberbullying and the variables under study. It would also be interesting to know the differences found in the present study according to the sex of the teachers. In this sense, it has been observed that women have higher scores in empathy, related to the feeling of self-efficacy in the classroom (Goroshit & Hen, 2016). Finally, this research aims to find out the predictive capacity of knowledge and the perception of competence on the performance of teachers in cases of cyberbullying. While it is reasonable to assume that there is an influential relationship between the variables, future research could test this relationship by developing two structural equation models to test the more stable hypothesis or, if so, what is the strength of the relationship in both models.

From a practical point of view, the results of this study highlight the need to design and implement educational intervention programmes aimed at improving teachers’ perceptions of competence. In this sense, self-efficacy beliefs are formed from four sources of information postulated by Bandura (1977): mastery experiences, verbal persuasion, vicarious experience, and affective states. The recent study by Gümüş et al. (2023) concluded that awareness of digital data security predicts sensitivity to cyberbullying.

Secondly, research has shown that teachers who are aware of cyberbullying situations are the ones who can finally do something to prevent or solve these cases. Therefore, it is essential to improve the channels of information and reporting of possible situations of cyberbullying among students. As stated by Romera et al. (2016), teachers and counsellors need clarifying knowledge and action models to manage groupings, work on improving classroom climate, developing social activities, analysing classroom relationships, and establishing interpersonal links. Finally, the collaboration of families and other educational professionals is essential to end this problem and reduce the negative effects on victims (Hellfeldt et al., 2020). In this sense, school and family are the two most important socialisation agents in students’ lives and should cooperate closely by educating empathy (Zhang et al., 2020).

Teachers stated that knowledge about cyberbullying cases and training is essential to increase online self-efficacy. According to previous studies, teachers believe that they lack the necessary resources and that their professional training has not adequately equipped them to handle cyberbullying concerns (Fredrick et al., 2023). This finding can be very useful in creating and improving teacher training in Higher Education. Teachers with higher levels of digital competence are more adept at detecting and acting on cyberbullying cases. To successfully implement digital technologies in the classroom and enhance the quality of teaching, both educational institutions and policymakers need to establish appropriate regulations that encourage teachers to improve their digital skills, actively engage in digital technology education, enhance their perspectives and self-efficacy in its use, and foster the growth of digital competencies (Macaulay et al., 2018). According to some studies, although teachers claim that being trained in cyberbullying knowledge would be effective (Pelfrey & Weber, 2014), they lack confidence in their ability to identify and manage the problem (Barnes et al., 2012). Therefore, both training in improving the detection of possible cases of cyberbullying and improving the sense of self-efficacy through teacher training are two fundamental tools in solving the problem of cyberbullying.

6. REFERENCES

Achuthan, K., Nair, V. K., Kowalski, R., Ramanathan, S., & Raman, R. (2022). Cyberbullying research—Alignment to sustainable development and impact of COVID-19: Bibliometrics and science mapping analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107566

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

Aparisi, D., Delgado, B., Bo, R. M., & Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C. (2021). Relationship between Cyberbullying, Motivation and Learning Strategies, Academic Performance, and the Ability to Adapt to University. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 10646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010646

Arezes, P. M., & Miguel, A. S. (2005). Hearing protection use in industry: The role of risk perception. Safety Science, 43(4), 253-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2005.07.002

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

Barlett, C. P. (2017). From theory to practice: Cyberbullying theory and its application to intervention. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 269-275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.060

Barnes, A., Cross, D., Lester, L., Hearn, L., Epstein, M., & Monks, H. (2012). The invisibility of covert bullying among students: Challenges for school intervention. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 22(2), 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.27

Bevilacqua, L., Shackleton, N., Hale, D., Allen, E., Bond, L., Christie, D., & Viner, R.M. (2017). The role of family and school-level factors in bullying and cyberbullying: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatrics, 17, 160 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0907-8

Bussey, K., Luo, A., Fitzpatrick, S., & Allison, K. (2020). Defending victims of cyberbullying: The role of self-efficacy and moral disengagement. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.006

Campbell, M., Whiteford, C., & Hooijer, J. (2018). Teachers’ and parents’ understanding of traditional and cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 18(3), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2018.1507826

Cerezo, F., y Rubio, F.J. (2017). Medidas relativas al acoso escolar y ciberacoso en la normativa autonómica española. Un estudio comparativo. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 20(1), 113-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/reifop/20.1.253391

Chaves, A. L., Morales, M. E., & Villalobos, M. (2020). Cyberbullying from the students’ perspective: “What we live, see and do”. Revista Electrónica Educare, 24 (1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.24-1.3

Chicote-Beato, M., González-Víllora, S., Bodoque-Osma, A., & Navarro, R. (2024). Cyberbullying intervention and prevention programmes in Primary Education (6 to 12 years): A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 77, 101938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2024.101938

Çırak, Y., & Demirkan, Ö. (2023). Comparison of Teachers’ Online Technologies Self-Efficacy and Cyberbullying Awareness (Cyprus Sample). International Journal of Innovative Approaches in Education, 7, 166-183. https://doi.org/10.29329/ijiape.2023.627.1

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

Cohen, J., McCabe, L., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111(1), 180–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911100108

Compton, L., Campbell, M.A., & Mergler, A. (2014). Teacher, parent and student perceptions of the motives of cyberbullies. Social Psychology of Education, 17, 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9254-x

Cosma, A., Molcho, M., & Pickett, W. (2024). A focus on adolescent peer violence and bullying in Europe, central Asia and Canada. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children international report from the 2021/2022 survey (Vol.2). World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376323

Crespo, E., & Freire, J.C. (2014). The attribution of responsibility: from cognition to the subject. Psicología y Sociedade, 26(2), 271-279. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822014000200004

De Vries, H., Dijkstra, M., & Kuhlman, P. (1988). Self-efficacy: the third factor besides attitude and subjective norm as a predictor of behavioural intentions. Health Education Research, 3(3), 273-282. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1093/her/3.3.273

Del Rey, R. Ortega-Ruiz, R., y Casas, J. A. (2019). Asegúrate: An intervention program against cyberbullying based on teachers’ commitment and on design of its instructional materials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030434

Eden, S., Heiman, T., & Olenik-Shemesh, D. (2013). Teachers’ perceptions, beliefs and concerns about cyberbullying. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(6), 1036-1052. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01363.x

Epstein, A., & Kazmierczak, J. (2006). Cyber bullying: What teachers, social workers, and administrators should know. Illinois Child Welfare, 3(1–2), 41–51.

Flores, R., Miedes, A., y Oliver, M. (2020). Efecto de un programa de prevención de ciberacoso integrado en el currículum escolar de Educación Primaria. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 25(1), 23-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2019.08.001

Fredrick, S. S., Coyle, S., & King, J. A. (2023). Middle and high school teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying prevention and digital citizenship. Psychology in the Schools, 60(6), 1958-1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22844

Gabarda, C., Cuevas, N., Martí, A., López-Agustí, A. I., y Rodríguez-Martí, A. (2022). Percepción del profesorado ante el Cyberbullying y detección de necesidades formativas del perfil competencial docente. REIDOCREA, 11(38), 458-466. http://dx.doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.76395

Giménez, A.M, Arnaiz, P., Cerezo, F., & Prodócimo, E. (2018). Teachers’ and students’ perceptions of cyberbullying. Intervention strategies in primary and secondary school. Comunicar, 56(26), 29-38. https://doi.org/10.3916/C56-2018-03

Giménez-Gualdo, A., Arnaiz-Sánchez, P., Cerezo-Ramírez, F., y Prodócimo, E. (2018). Percepción de docentes y estudiantes sobre el ciberacoso. Estrategias de intervención y afrontamiento en Educación Primaria y Secundaria. Comunicar, 56, 29-38. https://doi.org/10.3916/C56-2018-03

Gohal, G., Alqassim, A., Eltyeb, E., Rayyani, A., Hakami, B., Al Faqih, A., Hakami, A., Qadri, A., & Mahfouz, M. (2023). Prevalence and related risks of cyberbullying and its effects on adolescent. BMC psychiatry, 23(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04542-0

Goroshit, M., & Hen, M. (2016). Teachers’ empathy: can it be predicted by self-efficacy? Teachers and Teaching, 22(7), 805–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1185818

Gradinger, P., Strohmeier, D. & Spiel, C. (2017). Parents’ and Teachers’ Opinions on Bullying and Cyberbullying Prevention: The Relevance of Their Own Children’s or Students’ Involvement. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 225(1), 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000278

Green, V. A., Johnston, M., Mattioni, L., Prior, T., Harcourt, S., & Lynch, T. (2016). Who is responsible for addressing cyberbullying? Perspectives from teachers and senior managers. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 5(2), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1194240

Guarini, A., Menin, D., Menabò L., & Brighi A. (2019). RPC Teacher-Based Program for Improving Coping Strategies to Deal with Cyberbullying. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060948

Gümüş, M. M., Çakır, R., & Korkmaz, Ö. (2023). Investigation of pre-service teachers’ sensitivity to cyberbullying, perceptions of digital ethics and awareness of digital data security. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 14399-14421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11785-7

Heider, F. (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. Wiley.

Hellfeldt, K., López-Romero, L., & Andershed, H. (2020). Cyberbullying and Psychological Well-being in Young Adolescence: The Potential Protective Mediation Efects of Social Support from Family, Friends, and Teachers. International of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010045

Hirschstein, M. K., Edstrom, L.V.S., Frey, K. S., Snell, J. L., & MacKenzie, E. P. (2007). Walking the talk in bullying prevention: Teacher implementation variables related to initial impact of the Steps to Respect program. School Psychology Review, 36(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2007.12087949

Ho, S. S., Lwin, M. O., Yee, A. Z. H., Sng, J. R. H., & Chen, L. (2019). Parents’ responses to cyberbullying effects: how third person perception influences support for legislation and parental mediation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 373 380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.021

Holloway, A., & Watson, H. E. (2002). Role of self-efficacy and behaviour change. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 8, 2, 106-115. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172x.2002.00352.x

Huang, Y.-Y., & Chou, C. (2013). Revisiting cyberbullying: Perspectives from Taiwanese teachers. Computers & Education, 63, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.023

Hurtubise, P. (2021). Teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying: a comparative multilevel modelling approach. Cambridge Educational Research e-Journal, 8, 52-62. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.76201

Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P., & McCord, A. (2019). A developmental approach to cyberbullying: Prevalence and protective factors. Aggress Violent Behav, 45, 20-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.009

Lan, M., Law, N., & Pan, Q. (2022). Effectiveness of anti-cyberbullying educational programs: A socio-ecologically grounded systematic review and meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107200

Li, Qing. (2008). Cyberbullying in schools: An examination of preservice teachers’ perception. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 34. https://doi.org/10.21432/T2DK5G

Llorent, V. J., & Núñez-Flores, M. (2024). Social and emotional competencies of teachers to prevent and reduce cyberbullying. In A. L. C. Fung (Ed.), Cyber and Face-to-Face Aggression and Bullying among Children and Adolescents (pp. 1-14). Routledge.

Macaulay, P., Betts, L., Stiller, J., & Kellezi, B. (2018). Perceptions and responses towards cyberbullying: A systematic review of teachers in the education system. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.08.004

Martín-Criado, J. M., Casas, J. A., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2021). Parental Supervision: Predictive Variables of Positive Involvement in Cyberbullying Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041562

Maurya, C., Muhammad, T., Das, A. Fathah, A., & Dhillon, P. (2023). The role of self-efficacy and parental communication in the association between cyber victimization and depression among adolescents and young adults: a structural equation model. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 337. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04841-6

Mishna, F., Sanders, J. E., McNeil, S., Fearing, G., & Kalenteridis, K. (2020). “If Somebody is Different”: A Critical Analysis of Parents’, Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives on Bullying and Cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105366

Monks, C. P., Mahdavi, J., & Rix, K. (2016). The emergence of cyberbullying in childhood: Parent and teacher perspectives. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.02.002

Montoro, E., y Ballesteros, M. (2016). Competencias docentes para la prevención del ciberacoso y delito de odio en Secundaria. Relatec, 15(1), 131-143. https://doi.org/10.17398/1695-288X.15.1.131

Musset, P. (2010). Initial teacher education and continuing training policies in a comparative perspective. OECD education working papers, 48, 1-50. OECD.

Nagelkerke, N. J. D. (1991). A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika, 78(3), 691–692. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/78.3.691

Nappa, M. R., Palladino, B. E., Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2020). Do the face-to-face actions of adults have an online impact? The effects of parent and teacher responses on cyberbullying among students. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 798–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1860746

Ng, E. D., Chua, J. Y. X., & Shorey, S. (2022). The Effectiveness of Educational Interventions on Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(1), 132–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020933867

Nocentini, A., Zambuto, V., & Menesini, E. (2015). Anti-bullying programs and information and Communication Technologies (ICT): A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 52-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.012

Olenik-Shemesh, D., Heiman, T., y Keshet, N. S. (2019). Factors that affect teachers’ coping with cyberbullying: implications for teacher education programs. Educación Creativa, 10, 3357-3371. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.1013258

Ortega, R., Rey, R. D., y Casas, J. A. (2013). School coexistence: key in the prediction of bullying. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 6(2), 91-102. https://doi.org/10.15366/riee2013.6.2.004

Pelfrey, W., & Weber, N. (2014). Student and School Staff Strategies to Combat Cyberbullying in an Urban Student Population. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 59, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2014.924087

Powers, D. A., & Xie, Y. (2000). Statistical Method for Categorical Data Analysis. Academic Press.

Redmond, P., Lock, J. V., & Smart, V. (2018). Pre-service teachers’ perspectives of cyberbullying. Computers & Education, 119, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.12.004

Redmond, P., Lock, J. V., & Smart, V. (2020). Developing a cyberbullying conceptual framework for educators. Technology in Society, 60, 101223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101223

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change1. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803

Rohrmann, B., & Renn, O. (2000). Risk perception research. En O. Renn, B. & Rohrmann (Eds.). Cross-cultural risk perception, (pp. 11-53). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-4891-8_1

Romera, E. M., Cano, J. J., García, C. M., y Ortega, R. (2016). Cyberbullying: Social Competence, Motivation and Peer Relationships. Comunicar, 48(24), 71-79. https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-07

Samara, M., Da Silva Nascimento, B., El Asam, A., Smith, P., Hammuda, S., Morsi, H. & Al-Muhannadi, H. (2020). Practitioners’ perceptions, attitudes, and challenges around bullying and cyberbullying. International Journal of Emotional Education, 12(2), 8-25.

Sardessai, A.A., Mclaughlin, B., & Sarge, M.A. (2021). Examining teachers’ intentions to intervene: Formative research for school-based cyberbullying interventions in India. Psychology in the Schools, 58 (12), 2328-2344. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22595

Schoeps, K., Villanueva, L., Prado-Gascó, V. J., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2018). Development of Emotional Skills in Adolescents to Prevent Cyberbullying and Improve Subjective Well-Being. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2050. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02050

Schwarzer, R., & Fuchs, R. (1996). Self-efficacy and health behaviors. In M. Conner & P. Norman (Eds.), Predicting health behavior: Research and practice with social cognition models (pp. 163–196). Open University Press.

Sidera, F., Rostan, C., Serrat, E., y Ortiz, R. (2019). Teachers facing situations of bullying and cyberbullying at school. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology INFAD, Revista de Psicología, 3 (1), 421-434. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2019.n1.v3.1515

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

Stauffer, S., Heath, M. A., Coyne, S. M., & Ferrin, S. (2012). High school teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying prevention and intervention strategies. Psychology in the Schools, 49(4), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21603

Tomczyk, L., & Włoch, A. (2019). Cyberbullying in the light of challenges of school-based prevention. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education, 7(3), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.5937/IJCRSEE1903013T

Torres-Hernández, N., & Gallego-Arrufat, M. J. (2022). Indicators to assess preservice teachers’ digital competence in security: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 8583–8602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10978-w

Varela, J. J., Zimmerman, M. A., Ryan, A. M., & Stoddard, S.A. (2018). Cyberbullying Among Chilean Students and the Protective Effects of Positive School Communities. Journal of School Violence, 17(4), 430-442. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1358640

Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2007). Prevalence and Predictors of Internet Bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), 14-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.018

Williford, A., & Depaolis, K. J. (2016). Predictors of cyberbullying intervention among elementary school staff. Psychology in the Schools, 53(10), 1032–1044. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/pits.21973

Wong, D. S. W., Chan, H. C., & Cheng, C. H. K. (2014). Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Children and Youth Services Review, 36, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.11.006

Yot-Domínguez, C., Guzmán Franco, M. D., & Duarte Hueros, A. (2019). Trainee Teachers’ Perceptions on Cyberbullying in Educational Contexts. Social Sciences, 8(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010021

Zhang, X., Han, Z., & Ba, Z. (2020). Cyberbullying Involvement and Psychological Distress among Chinese Adolescents: The Moderating Effects of Family Cohesion and School Cohesion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238938