Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation Vol. 11. No. 1. June 2025 - pp. 150-168 - ISSN: 2444-2925

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/ijtei.111.2025.20559

The effect of gamified flipped learning on Malaysian fifth-grade students’ academic achievement and learning experience in science

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.1. INTRODUCTION

Primary school science education plays a critical role in shaping students’ attitudes toward science and building foundational problem-solving skills. Research suggests that interdisciplinary learning, especially with technology integration, positively influences students’ attitudes toward science (Zhou & Lin, 2024). However, many primary school students struggle with science, often perceiving it as difficult, which has led to a search for more engaging and relevant teaching strategies to improve students’ scientific inquiry skills (Ortiz & Aliazas, 2021). Challenges in science education stem from outdated teaching methods (Marcourt et al., 2022), limited exposure to science careers (Kang et al., 2023), and teachers’ limited pedagogical content knowledge, all of which hinder students’ interest in learning science (Solis-Foronda & Marasigan, 2021).

In Malaysia, data from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) study (1999-2019) reveals a concerning decline in students’ science performance, with a drop in the percentage of students meeting advanced benchmarks and average scores falling below the international average (Phang et al., 2021). Despite students’ initial interest in science, their confidence wanes over time due to traditional teaching approaches, assessment issues, and limited opportunities to explore science-related careers. To address these challenges, experts recommend curriculum adaptation (DeBarger et al., 2017), pedagogical innovation (Iwuanyanwu, 2019), and the integration of technology into science education, such as the use of games (Yilmaz, 2023).

Game-based learning (GBL) and flipped learning have been identified as promising solutions to these challenges. A meta-analysis by Lei et al. (2022) of 41 studies comparing GBL to traditional methods found that GBL enhances students’ understanding of complex scientific concepts, increases engagement, and improves academic outcomes in science learning, particularly in quizzes and exams. Fahdiran et al. (2021) observed improved science learning outcomes in 6th-grade students when the flipped classroom approach incorporated active learning strategies.

Gamification, the integration of game elements into non-gaming contexts, has also gained attention in educational research for its potential to enhance student engagement and motivation (Majdoub & Heilporn, 2024; Rodrigues et al., 2022). Studies suggest that gamification can foster positive learning experiences (Klock et al., 2018) and improve social interaction (Gaonkar et al., 2022). However, gamification is not without its challenges; for instance, poorly designed gamified activities can lead to frustration, reduced engagement, or a focus on extrinsic rewards rather than intrinsic learning goals (Buckley & Doyle, 2016).

Integrating gamification into flipped learning addresses these challenges by enhancing engagement during out-of-class activities and improving overall flipped learning effectiveness. For instance, Huang et al. (2018) found that gamification improved engagement and performance in a flipped course, while Lo and Hew (2018) reported that gamified flipped learning enhanced academic performance and cognitive engagement compared to traditional approaches. However, challenges such as designing effective gamified components and overcoming technological barriers remain (Gündüz & Akkoyunlu, 2020).

Recent research, including Mulyanti et al. (2023), demonstrates the effectiveness of gamified flipped learning in improving fifth-grade students’ science achievement. However, their focus on general science leaves gaps in understanding its impact on specific topics, such as Machines, and its applicability in contexts like Malaysia. Additionally, while evidence supports the academic benefits of gamified flipped learning, less is known about its effects on students’ learning experiences.

These findings underscore the potential of flipped learning across diverse subjects and settings. However, integrating digital games into this model remains underexplored. This gap highlights the need for further research on how GBL can complement and enhance flipped learning to improve both academic outcomes and student experiences.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Flipped Learning

The concept of flipped learning, introduced by Bergmann and Sams (2012), has transformed traditional teaching methods by reversing classroom activities. Students complete preparatory tasks outside of class and engage in more interactive, teacher-guided activities during in-class sessions. This approach fosters a student-centred learning culture, encouraging deeper engagement with content. In the digital era, flipped learning incorporates synchronous (live, online, real-time) and asynchronous (delayed, not in real-time) learning tasks to maximise flexibility and accessibility.

Recent studies emphasise the adaptability of flipped learning across disciplines and educational levels (see Table 1). For example, Ranoptri et al. (2022) and Erkan and Duran (2023) demonstrated how inquiry-based, and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM-integrated) flipped models improved science outcomes and creativity in junior high and primary school students. Similarly, Cheng (2023) found gains in critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity through STEM-integrated flipped learning. These studies highlight flipped learning’s potential to develop higher-order thinking skills. However, the extent to which these benefits are sustained across different contexts requires further exploration.

Flipped learning approaches vary in design and outcomes. Da Silva et al. (2022) and Lee et al. (2021) investigated dialogic and cooperative flipped models, respectively, reporting improvements in science achievement and motivation. While these studies showcase the strengths of flipped learning, they focus primarily on its structural elements, neglecting the role of motivational strategies that could enhance engagement in pre-class tasks. This gap is particularly concerning given challenges such as the lack of student participation in at-home activities, as noted by Maxwell (2024).

TABLE 1. Critical analysis of research gaps in Flipped Learning

| No. | Researchers | Samples | Learning Approaches | Findings |

| 1. | Ranoptri et al. (2022) | 7th grade of junior high school students | Inquiry web-based learning multimedia | Improvement of learning outcome in science |

| 2. | Erkan and Duran (2023) | 4th grade of primary school students | STEM activities with flipped learning | STEM activities with flipped learning model improved scientific creativity and perceptions |

| 3. | Cheng (2023) | Primary school | STEM activities with flipped learning | Enhancement of critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity skills |

| 4. | Flores-Gonzales & Flores-Gonzales (2022) | High school students | Virtual learning environment | Enhancement of students’ comprehensive learning process in science with increased completion of activities and higher-grade point averages |

| 5. | Da Silva et al. (2022) | High school students | Flipped learning with dialogic strategies | Promotion of student protagonism in science |

| 6. | Lee et al. (2021) | High school students | Cooperative flipped learning (CFL) | CFL showed higher science achievement and motivation than simple flipped learning |

| 7. | Rudoft (2021) | Secondary school students | Flipped learning with interactive video | Significant improvement in understanding mathematical concepts |

| 8. | Fahdiran et al. (2021) | 6th grade primary students | Flipped classroom approach with active learning | Improvement of learning outcome in science |

2.2. Gamification

Gamification and GBL are increasingly recognised for their potential to enhance student engagement. Unlike GBL, which uses fully immersive games tailored for educational purposes, gamification incorporates game elements such as points, levels, and rewards into traditional educational tasks, fostering motivation without altering the core learning activities (Al-Azawi et al., 2016; Maratou et al., 2023;). This approach has demonstrated success in improving student motivation, engagement, and knowledge retention across various educational contexts (Nipo et al., 2023; Lim et al., 2024). For instance, Nilubol (2023) showed that gamified strategies particularly benefited students with high intrinsic motivation, while Mulyanti et al. (2023) observed enhanced science learning outcomes in fifth-grade students. These findings suggest that gamification could address challenges in flipped learning, such as student disengagement during pre-class tasks, yet successful implementation requires careful alignment of gamified elements with the educational goals (Guerrero-Quinonez et al., 2023).

Yu and Yu’s (2023) meta-analysis of gamified flipped classrooms (GFCs) reveals positive effects on academic achievement, motivation, and satisfaction, especially in Asian and African contexts, where cultural and technological factors amplify the benefits of gamified learning. However, most existing studies have primarily focused on secondary and higher education, leaving a significant gap in understanding the potential of GFCs for primary school students. Integrating gamification into flipped learning combines the principles of flipped classrooms with game design elements to boost student engagement. Gamification addresses the key challenge of engaging students in pre-class activities by providing immediate feedback, rewards, and a sense of progression (Toda et al., 2019). This approach creates a synergy, where flipped learning offers a structured framework for independent and collaborative activities, while gamification enhances engagement and motivation throughout the learning process. Research by Guerrero-Quinonez et al. (2023) and Yu and Yu (2023) highlight the potential of this combined approach, particularly in science education.

Despite its potential, the integration of gamified flipped learning in primary education remains underexplored, as most research treats flipped learning and gamification as separate strategies. This gap is particularly significant in primary education, where gamification has the potential to sustain student motivation and engagement during pre-class activities. The current study seeks to address this gap by examining how gamified flipped learning can enhance primary students’ academic achievement and learning experiences, with a specific focus on the science topic of Machines. According to Sayeski et al. (2015), the effectiveness of flipped learning is often hindered when students fail to engage with pre-class tasks. By incorporating gamification, this study aims to determine whether such integration can address these challenges and improve the overall flipped learning experience. This investigation is crucial, as existing literature provides limited exploration of gamification as a complementary strategy within the flipped learning model, particularly at the primary school level.

3. THEORETICAL UNDERPINNING OF GAMIFIED FLIPPED LEARNING

The theoretical foundation of gamified flipped learning combines the flipped learning model by Bergmann and Sams (2012) and gamification elements by Toda et al. (2019), offering a framework for integrating gamification into flipped classrooms.

3.1. Foundational pillars of flipped learning

Bergmann and Sams (2012) introduced four foundational pillars of flipped learning: flexible environment, learning culture, intentional content, and professional educator.

- Flexible environment: This pillar emphasises both synchronous and asynchronous learning, allowing students to learn at their own pace. In a gamified flipped classroom, this flexibility is enhanced through elements like progress tracking and levels to enable students to navigate their learning journey more dynamically.

- Learning culture: The flipped model promotes a student-centred culture, where learners take responsibility for their education. Gamification supports this by encouraging active participation through points, levels, and rewards to reinforce positive behaviours.

- Intentional content: Educators select content carefully to suit both independent study and collaborative activities. Gamification helps by breaking content into smaller, engaging segments, often linked to levels or progress indicators to keep students motivated.

- Professional educator: Educators play a key role in designing and managing a gamified flipped classroom. They ensure that gamified elements align with learning goals and provide personalised support for students.

By integrating these pillars with gamification, educators can create a more engaging and effective flipped learning environment that addresses the needs of diverse learners.

3.2. Gamification Sub-Elements

Toda et al. (2019) identified several gamification sub-elements that enhance learning engagement and motivation. These elements, when integrated with flipped learning, create a synergistic effect that supports academic achievement and positive learning experiences:

- Acknowledgement: Recognising student achievements through badges, trophies, or medals provides extrinsic motivation and encourages active participation.

- Level: Offering levels or skill hierarchies motivates students to progress through increasingly challenging tasks, which align with the adaptive nature of flipped learning.

- Progress: Progress bars, maps, or steps provide visual feedback on students’ advancement, helping them stay on track in both independent and collaborative activities.

- Points: Assigning points for completed tasks or correct answers gives students immediate feedback and fosters a sense of accomplishment.

- Time pressure: Countdown timers or time-limited challenges encourage focus and efficiency, particularly during in-class activities designed to apply learned concepts.

- Novelty: Introducing surprises or unexpected elements within tasks keeps students engaged and prevents monotony, which is an essential aspect of sustaining attention in flipped learning environments.

- Chance: Incorporating elements of luck, such as random rewards or outcomes, adds excitement and unpredictability that make the learning experience more engaging.

The integration of Bergmann and Sams’ (2012) flipped learning model with the gamification sub-elements proposed by Toda et al. (2019) creates a robust theoretical foundation for gamified flipped learning. This approach not only enhances the structural flexibility and engagement of the flipped classroom but also aligns with modern pedagogical goals, fostering motivation, active learning, and student- centred experiences.

4. RESEARCH CONTEXT, OBJECTIVES, AND QUESTIONS

This study focused on fifth-grade students and investigated the implementation of gamified flipped learning activities to understand their impact on students’ academic achievement and learning experiences. The objectives of this study were as follows:

- To examine the effects of digital gamified flipped learning activities on the academic achievement of Malaysian fifth-grade students.

- To explore the learning experiences of fifth-grade students participating in gamified flipped learning activities.

To achieve these objectives, this study addressed the following research questions:

- What are the effects of digital gamified flipped learning activities on the academic achievement of Malaysian fifth-grade students?

- What are the learning experiences of fifth-grade students participating in gamified flipped learning activities?

5. METHOD

5.1. Research Design

This study utilised a mixed-methods approach, employing a quasi-experimental design for the quantitative component and interviews for qualitative data collection. The quasi-experimental design was chosen for its appropriateness in assessing the effectiveness of a digital game-based flipped classroom approach in enhancing student academic achievement on the topic of Machines, compared to conventional teaching without flipped learning activities. Specifically, a pre-test and post-test control group design was used. Participants in both the treatment and control groups had similar characteristics but were not randomly assigned due to predetermined group allocations by the school.

To control for potential confounding variables, particularly prior knowledge, a pre-test was administered to both groups before the intervention. The Quade-ANCOVA analysis was then employed to evaluate the effect of the pre-test on post-test scores, using the pre-test scores as a covariate. This approach helped address any pre-existing differences in baseline knowledge between the groups.

This study’s data collection process spanned four weeks, comparing a control group and a treatment group in a quasi-experimental design. In Week 1, both groups began with a pre-test to assess their prior knowledge on the science topic of Machines. Following the pre-test, the treatment group engaged in five digital games created using Wordwall, which were hosted on a website designed with Google Sites. These games served as the flipped learning component and allowed students to explore the topic asynchronously during Week 2. The control group, meanwhile, did not participate in these pre-class digital activities.

In Week 3, both groups engaged in in-class teaching and learning activities, led by the same teacher to ensure consistency. After completing the in-class sessions, both groups took a post-test in Week 4 to measure knowledge acquisition on the Machines topic. In addition, the treatment group participated in interviews to discuss their experiences with the gamified flipped learning activities. Figure 1 illustrates the data collection process involving both the treatment and control groups.

FIGURE 1. Data collection process

| Week | Control Group ↓ | Treatment Group ↓ |

| Week 1 | Pre-test ↓ | Pre-test ↓ |

| Week 2 | ↓ | Five Digital Games (Wordwall) ↓ |

| Week 3 | In-class teaching and learning activities ↓ | In-class teaching and learning activities ↓ |

| Week 4 | Post-test | Post-test Interviews |

5.2. Samples

For this study, a school in the Kulai district of Malaysia was purposively selected based on the following criteria:

- The school possessed appropriate technological facilities.

- Accessibility for data collection purposes by the researcher.

- The basic background of the involved students could be identified by the researcher.

The study involved a sample of 40 fifth-grade students, selected through cluster random sampling from two classes at a public primary school in the Kulai district. All participants were learning science, focusing on simple machines and their functions. Class 5b was randomly assigned as the treatment group, which experienced the flipped classroom model incorporating digital GBL, while Class 5a, the control group, followed conventional teaching methods. Both groups were taught by the same Science teacher to ensure consistency in instructional quality. To gain deeper insights into the students’ experiences with the gamified flipped learning approach, six students from the treatment group were randomly selected for interviews, providing a more thorough understanding of their engagement and learning outcomes.

5.3. Research Instruments

The research instruments included pre- and post-test questions adopted by expert teachers from validated exam questions in the Ministry of Education’s Standardised Primary School Evaluation Test, with a focus on the Machines topic. These questions assessed students’ understanding of the functions of simple machines in various devices. The test consisted of 34 identical subjective questions, each worth one point, for a total score of 34 points, and was administered during both the pre-test and post-test phases. Based on the Examination Division of the Ministry of Education, the questions were designed to evaluate academic achievement at Bloom’s Taxonomy levels of understanding, application, and analysis. To ensure scoring objectivity, all responses were graded by the classroom teacher and verified by an independent teacher using the standardised answer scheme validated by the Ministry, achieving an inter-rater agreement of 82.5%.

While the test items were based on Ministry-approved question banks, which have undergone construct validity checks for the Machines topic, additional validation specific to this study’s context would have further enhanced their appropriateness for the target age group and topic. A pilot test was conducted with 10 fifth-grade students to check the appropriateness of the test questions, and content validity was established through reviews by two primary science teachers. Additionally, the reliability of the test was confirmed through a test-retest analysis, yielding a high Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.85.

In addition to the test, individual interviews were conducted by the classroom teacher with students in the treatment group to explore their learning experiences during the gamified flipped learning activities. These interviews followed a structured protocol with open-ended questions aimed at capturing students’ feelings and perceptions about learning through digital games, their preferences for learning activities, and their views on the effectiveness of the games in supporting their learning. Before data collection, the interview protocol was reviewed and validated by two expert primary school teachers to ensure the questions were appropriate for the fifth-grade level.

5.4. In-class Teaching and Learning Activities

The in-class teaching and learning activities covered the same scope as the five gamified learning activities, including subtopics such as simple machines, complex machines, and the importance of creating tools sustainably. The teaching method used in both groups was a tutorial-based approach within a conventional classroom setting. The same teacher who instructed the treatment group also delivered the content to the control group, ensuring consistency in instructional delivery across both groups. The only difference was that the treatment group engaged with the digital games prior to the in-class activities, providing them with a gamified flipped learning experience before interacting with the conventional instructional content.

5.5. Digital Games

Five digital games were developed for this study using the Analyse, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate (ADDIE) instructional design model (Heinich et al., 2002). The process followed these phases:

- Analysis phase: This phase involved analysing the students’ prior knowledge, technological familiarity, and the school’s resources, such as computer facilities and internet speed, to ensure the games were compatible.

- Design and development phase: The games were designed using gamification elements like points, badges, and leaderboards (Toda et al., 2019). After development, an Educational Technology expert reviewed the games for alignment with educational goals.

- Implementation phase: The games were pilot-tested with a small group of three fifth-grade students to check their functionality, usability, and engagement. Any technical issues were addressed before the games were used in the actual experiment.

- Evaluation phase: The final phase involved collecting data from students’ performance and experiences while using the games in the experiment.

Table 2 presents a detailed mapping of the subtopics, digital game elements, learning activities, and technological tools used in the study.

TABLE 2. Mapping of subtopics, digital game elements, learning activities, and technological tools

| Weeks | Subtopics | Gamification Elements (Toda et al., 2019) | Games | Technology Tools |

| 1 | Simple Machines 1 | Progress Point | Digital game ‘Speedy Plane’ | Google Sites Wordwall App |

| 2 | Simple Machines 2 | Acknowledgement Time pressure | Digital game ‘Truth Stage’ | |

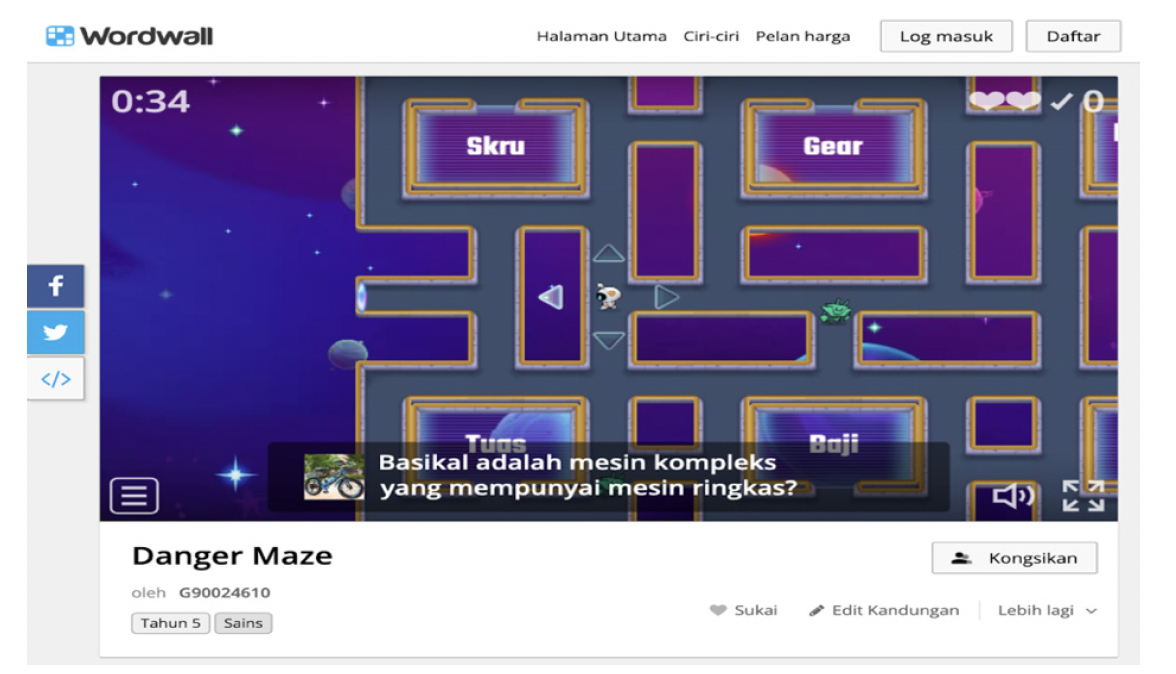

| 3 | Complex Machines 3 | Acknowledgement Novelty | Digital game ‘Danger Maze’ | |

| 4 | Complex Machines 4 | Point Chance Novelty | Digital game ‘Bomb It’ | |

| 5 | The Importance of Sustainable Features in Tool Creation | Point Time pressure | Digital game ‘The Winner’ |

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate examples of the Danger Maze and Bomb It games.

FIGURE 2. Danger Maze

FIGURE 3. Bomb It

5.6. Data Analysis

The data obtained were analysed using descriptive statistical tests, such as the mean and standard deviation, as well as inferential tests, including Quade-ANCOVA. The pre-test was used as a covariate to statistically adjust for initial differences between the treatment and control groups. Given that the data did not follow a normal distribution, Quade-ANCOVA was selected for its robustness against violations of normality assumptions. This method enables comparison of the post-test mean scores between the treatment and control groups while accounting for the effects of the pre-test scores as a covariate.

Additionally, an analysis of student learning experiences in gamified flipped classroom learning was conducted by two expert teachers. This study adapted inductive thematic analysis on the interview data collected, following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase guideline. Since the qualitative data consisted of simple sentences from primary students, themes were identified based on commonalities in the responses provided by the interviewed students. If students expressed similar perspectives regarding the questions asked, those themes were considered stable and significant for highlighting as study findings. The inter-coder reliability between the two teachers was 87.1% agreement.

5.7. Research Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from both the schools and the parents or guardians of the students prior to the study. Participants were assured that their data would remain anonymous, and their privacy would be protected throughout the research process. To ensure that student well-being was not jeopardised, the study was designed with minimal disruption to regular learning activities. Additionally, all participants were informed that their involvement in the study was voluntary, and they could withdraw at any time without consequence. These measures were taken to uphold ethical standards and ensure the safety and privacy of all students involved.

6. RESULT

6.1. The Effects of Gamified Flipped Classroom Learning Activities on the Academic Achievement of Malaysian Fifth-Grade Students

Table 3 shows the pre-test and post-test means and standard deviations for both the control and treatment groups. The control group had a pre-test mean of 12.25 with a standard deviation of 2.12, indicating less variability in scores compared to the treatment group, which had a pre-test mean of 9.3 with a standard deviation of 2.57. This suggests that the control group’s scores were more consistent before the intervention. After the intervention, both groups showed increased variability in their post-test scores, but the treatment group had a slightly lower standard deviation (3.02) compared to the control group (3.12), indicating more consistency in the treatment group’s improvement. The treatment group’s post-test mean was 26.9 out of a maximum score of 34, while the control group’s post-test mean was 17.

TABLE 3. Descriptive analysis of fifth-grade student’s achievement

| Control Group (n = 20) | Treatment Group (n = 20) | Levene’s test (p value) | Shapiro-Wilk Test (p value) | |

| Pre-Test Mean | 12.25 | 9.3 | .010* | - |

| Post-Test Mean | 17 | 26.9 | - | .041** |

| Pre-Test Standard deviation | 2.12 | 2.57 | - | - |

| Post-Test Standard deviation | 3.12 | 3.02 | - | - |

*the homogeneity assumption of the variance did not met **post-test data not normally distributed

The results of Levene’s test indicated that the homogeneity of variance assumption was not met for the pre-test scores, with a p-value of 0.010 (p < 0.05). This suggests that the variance of the pre-test scores differed significantly between the two groups, thereby violating the assumption of equal variances necessary for standard ANCOVA. As a result, the use of a non-parametric alternative, i.e. Quade-ANCOVA, was considered necessary for this analysis.

Additionally, the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality yielded a p-value of 0.041 for the post-test scores (p < 0.05), indicating that the post-test data were not normally distributed. This reinforces the need for a robust statistical method that can handle non-normal data distributions.

Given these violations, Quade-ANCOVA was employed to analyse the significance of the differences in post-test scores between the control and treatment groups. Quade-ANCOVA is a suitable alternative to traditional ANCOVA when the assumption of normality is violated or when variances are unequal between groups, as in this case. Unlike parametric ANCOVA, which assumes normally distributed residuals, Quade-ANCOVA adjusts for covariates while accounting for the non-normality in the data, providing more accurate estimates of treatment effects.

By employing Quade-ANCOVA, the study ensures the validity of its findings despite the violations of homogeneity of variance and normality. This robust approach increases the reliability and validity of the results, making it especially well-suited for educational research, where data often deviate from normality and exhibit heteroscedasticity. Therefore, the use of Quade-ANCOVA enhances the robustness of the study’s conclusions while addressing the issues identified through the Levene’s and Shapiro-Wilk tests.

Based on the Quade-ANCOVA analysis (see Table 4), a significant difference was observed in the mean post-test scores between the treatment and control groups, with a p-value of less than 0.05. The effect size of the treatment on student achievement was substantial, as indicated by an eta squared value of 0.626.

TABLE 4. The Quade-ANCOVA analysis

| Test of Between – Subject Effects | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Unstandard Residual | ||||||

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

| Corrected Model | 3260.472 | 1 | 3260.472 | 63.737 | .000 | .626 |

| Intercept | .000 | 1 | .000 | .000 | 1.000 | .000 |

| Group | 3260.472 | 1 | 3260.472 | 63.737 | .000 | .626 |

| Error | 1943.897 | 38 | 51.155 | |||

| Total | 5204.368 | 40 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 5204.368 | 39 | ||||

*R Squared = .626 (Adjusted R Squared = .617)

6.2. The Learning Experiences of Malaysian Fifth-Grade Students Participating in Gamified Flipped Learning Activities

Based on the thematic analysis of the interview transcripts with students, several learning experiences were identified, as illustrated in Table 5.

TABLE 5. Thematic analysis of interview transcripts

| No. | Interview Questions | Example | Theme |

| 1. | How do you feel when you learn through flipped learning with games, what are your feelings? | S1: “I feel so excited when doing quizzes.” S2: “Happy, later when answering the exam, that question will be easy because I have studied it.” S5: “I feel nervous because games involve competition” | Happy, excited, fun, like it Nervous |

| 2. | Do you like playing digital games on the topic of Machines? | S2: “Like it.” S6: “I love it” | Like it |

| 3. | When do you play digital games on the topic of Machines? | S3: “At night.” S2: “Whenever I’m free” | Anytime |

| 4. | What is your favourite digital game on the topic of Machines? Why? | S2: “Danger Maze because I always play games like that.” S4: “Truth Stage.” | Speedy Plane, Danger Maze, Truth Stage |

| 5. | How many times do you play each digital game? If more, why do you play more than once? | S3: “Speedy Plane three times, quiz four times, the rest just once or twice. S5: “More than five times.” | Many times (more than five times) |

| 6. | Which option do you prefer, continue learning through digital games or using textbooks as usual in class? Why? | S3: “ Digital games made me feel excited.” S4: “Digital games because I like it.” | Digital games Feel excited |

| 7. | Do you think these digital games help you excel as a student? Why? | S6: “It’s easy to learn.” S5: “Not sure. I need to play games for other topics” | Easy Unsure |

7. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of between-subject effects reveals a highly significant relationship between participation in gamified flipped learning and conventional learning, with a statistical outcome of F = 63.737, p < .001 (see Table 4). This significance indicates that the treatment group, engaged in gamified flipped learning activities, experienced notably different learning outcomes compared to the control group. This finding corroborates the studies by Lo and Hew (2018) and Jo et al. (2018), which demonstrated that students in gamified flipped classrooms outperform those in traditional or online independent study settings. Elements of gamification, such as ranking systems and word games, have been shown to increase participation rates, competitive spirit, and interest in online preparation activities (Jo et al., 2018), a trend that is not only evident among higher education students but also among primary school students in this study.

The data analysis further indicates that following the intervention with digital games in flipped learning, students’ knowledge and understanding of the topic of Machines significantly improved compared to their previous levels. The notable increase in scores among the treatment group relative to the control group underscores the effectiveness of integrating flipped learning with digital games. This finding aligns with Gündüz and Akkoyunlu’s (2020) research, which established that gamification in flipped learning environments can enhance achievement.

Additionally, the effect size, measured by partial eta squared (0.626), indicates a large effect (Cohen, 1988), suggesting that 62.6% of the variability in students’ learning experiences can be attributed to their participation in gamified flipped learning activities. This substantial effect size underscores the robust impact of these innovative educational approaches on enhancing student engagement, motivation, and comprehension of the subject matter.

The findings also align with the research conducted by Tsay et al. (2018), which reported similar results among second-year business students regarding learning through gamification. This study expands upon Tsay’s work by demonstrating that these benefits extend to primary school students, indicating that the effectiveness of the gamification approach is applicable across educational levels. Moreover, learning through digital games can enhance motivation and knowledge, even for students who initially lack experience with such games (Divjak and Tomic, 2011). This study enriches the existing research on gamification by illustrating how the integration of flipped learning enhances its impact. The positive effects observed from the gamified approach can be attributed to the use of flipped learning for the topic of Machines.

Students demonstrated remarkable improvement when engaging with gamified flipped learning, as they repeatedly played digital games until achieving their desired scores. They expressed a greater interest in self-paced activities through digital games and consistently allocated time to play games related to the topic of Machines. This enthusiasm may stem from the engaging elements of digital games, which rely on factors such as the gaming environment, game design, visual presentation, and mechanical technology (Lacovides et al., 2011). Additionally, students found the provided digital games easy to understand for each concept they learned. Key factors contributing to this effectiveness include perceived ease of use, usefulness, and satisfaction, as identified by Guo et al. (2020). Previous studies have also indicated that well-designed games can be highly playable, enjoyable, and immersive, with most students quickly familiarising themselves with the game elements (Yue & Wan, 2015).

The findings of this study indicate that students’ experiences with flipped learning, enhanced by digital games, are overwhelmingly positive (see Table 5). Participants expressed feelings of happiness, excitement, and enjoyment while engaging with this approach. This positivity can be attributed to the student-centred nature of flipped learning, which promotes active participation in the learning process (Siegle, 2013). Furthermore, the integration of digital games as educational tools creates an enjoyable learning environment, challenging students to excel in these interactive activities (Thomas & Mahmud, 2021).

Students interviewed articulated a clear preference for the gamified flipped learning approach over traditional textbook-based learning. They eagerly embraced digital game activities, often engaging repeatedly until they achieved their desired scores. This behaviour reflects their eagerness to grasp additional information and ensure they do not miss key insights during the gamified learning activities. Additionally, students demonstrated high levels of motivation, actively seeking opportunities to participate in digital GBL.

However, one student expressed a neutral response, reporting nervousness due to the competitive nature of the games. For this student, the element of competition, while motivating for many, created a sense of pressure that made the learning experience somewhat stressful. This highlights the importance of designing gamified activities that balance competition with collaboration to ensure all students feel supported in their learning journey.

Using digital games, students effectively recalled relevant content, accurately identifying key elements such as simple machines, wheels and axles, levers, pulleys, screws, inclined planes, wedges, and gears. This mastery was achieved through self-directed learning, as students repeatedly engaged with the digital games until they attained high scores. Beyond the classroom, the flipped learning method not only enhanced students’ comprehension of prior knowledge but also reinforced their understanding of new topics through digital games (Du et al., 2014).

In their interviews, students noted that digital games contributed significantly to their academic success and enjoyment of the flipped learning approach. The application of digital GBL methods effectively captured students’ attention, promoting increased engagement and boosting their confidence (Tangkui & Tan, 2020). Overall, students’ learning experiences with the gamified flipped learning approach were decidedly positive. These findings align with research by Aidoo et al. (2022), which also highlighted students’ positive perceptions of the flipped learning method. However, one student expressed uncertainty, stating, “I need to play games for other topics,” suggesting a desire for the broader application of digital games to other subjects. This indicates that while the current approach was engaging, there is potential for further expansion to enhance learning across a wider range of topics.

Moreover, this study builds upon previous research, such as the work by Borit and Stangvaltaite-Mouhat (2020), which found that GBL integrated with flipped classrooms resulted in greater enjoyment, engagement, and perceived learning among students in dental education. This study focuses on learning Science at the primary school level, thus expanding the research conducted by Borit and Stangvaltaite-Mouhat (2020).

In conclusion, the integration of GBL and flipped learning presents a highly effective approach to modern education by enhancing student engagement, motivation, and academic performance. Tools such as Wordwall and Google Sites, along with the development of digital games, provided science educators with innovative resources to diversify their teaching methods. The findings revealed significant improvements in fifth-grade students’ academic performance, evidenced by higher post-test scores and positive attitudes toward gamified flipped learning. By combining the interactive and immersive aspects of GBL with the preparatory advantages of flipped learning, students are better equipped with foundational knowledge prior to class and actively engage in deeper learning during in-person sessions. This synergy not only improves comprehension and confidence but also empowers educators with innovative tools to create dynamic and impactful learning experiences, particularly in science education.

7.1. Limitations and future lines of research

Despite the positive findings of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the research focused specifically on gamified learning related to the topic of Machines among fifth-grade students at a single primary school in Malaysia. This narrow scope may limit the generalisability of the results to other contexts or educational levels. Furthermore, the assessment of student improvement in academic achievement was based solely on performance tests, which may not capture the full spectrum of learning outcomes associated with gamified flipped learning, such as critical thinking, creativity, and collaborative skills.

Future studies should consider several recommendations to address these limitations, including conducting research across various educational institutions and regions to assess the effectiveness of gamified flipped learning in different settings and among diverse student populations, which would enhance the generalisability of the findings. Additionally, it would be beneficial to investigate the effectiveness of different gamification elements—competition, reward systems, or specific game mechanics—to identify which elements most effectively enhance student engagement and learning outcomes.

A broader array of assessment methods should be incorporated, including qualitative measures such as observations, student reflections, and peer evaluations alongside quantitative performance tests, to provide a more holistic understanding of the impact of gamified flipped learning on student learning experiences. Furthermore, implementing longitudinal studies could examine the long-term effects of gamified flipped learning on student academic achievement and learning experiences, offering insights into how these methods influence learners over time. Lastly, research should be expanded to include other subjects beyond science, thereby evaluating the applicability and effectiveness of gamified flipped learning across the curriculum.

8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported/funded by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) Malaysia under Fundamental Research Grant Scheme [FRGS/1/2023/SSI07/UTM/01/2].

9. REFERENCES

Aidoo, B., Tsyawo, J., Quansah, F., & Boateng, S. K. (2022). Students’ learning experiences in a flipped classroom: A case study in Ghana. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 18 (1), 67-85.

Al-Azawi, R., Al-Faliti, F., & Al-Blushi, M. (2016). Educational gamification vs. Game based learning: comparative study. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology, 7(4), 132-136. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijimt.2016.7.4.659

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. International Society for Technology in Education.

Borit, M., & Stangvaltaite-Mouhat, L. (2020). GoDental! Enhancing flipped classroom experience with game-based learning. European Journal of Dental Education, 24(2), 763-772. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12566

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buckley, P., & Doyle, E. (2016). Gamification and student motivation. Interactive Learning Environments, 24, 1162-1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.964263

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Da Silva, J., Felicio, C. M., & Teodoro, P. V. (2022). Flipped classroom and digital technologies: Didactic possibility for science teaching in an active methodology proposal. Brazilian Journal of Education, Technology, and Society, 17, 1386-1401. https://doi.org/10.21723/riaee.v17i2.15807

DeBarger, A. H., Penuel, W. R., Moorthy, S., Beauvineau, Y., Kennedy, C. A., & Boscardin, C. K. (2017). Investigating purposeful science curriculum adaptation as a strategy to improve teaching and learning. Science Teacher Education, 101(1), 66–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21249

Divjak, B., & Tomić, D. (2011). The impact of game-based learning on the achievement of learning goals and motivation for learning mathematics-literature review. Journal of Information and Organizational Sciences, 35(1), 15-30. https://jios.foi.hr/index.php/jios/article/view/182

Du, S. C., Fu, Z. T., & Wang, Y. (2014). The flipped classroom—Advantages and challenges. Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Economic Management and Trade Cooperation (pp. 17–20). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/emtc-14.2014.3

Erkan, H., & Duran, M. (2023). The effects of STEM activities conducted with the flipped learning model on primary school students’ scientific creativity, attitudes and perceptions towards STEM. Science Insights Education Frontiers, 15(1), 2175-2225. https://doi.org/10.15354/sief.23.or115

Fahdiran, R., Serevina, V., & Maha Putra, A. V. (2021). The effect of active learning in the flipped classroom learning model on 6th grade science subjects of elementary school. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2309/1/012072

Flores-González, E., & Flores-González, N. (2022). The flipped classroom as a tool for learning at High School. Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 6(16), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.35429/JCP.2022.16.6.10.18

Gaonkar, S., Khan, D., & Ashish Singh, M. (2022). Impact of gamification on learning and development. Journal of Advances in Education and Philosophy, 6(2), 63-70. https://doi.org/10.36348/jaep.2022.v06i02.003

Guerrero-Quiñonez, A. J., Quiñónez Guagua, O., & Barrera-Proaño, R. G. (2023). Gamified flipped classroom as a pedagogical strategy in higher education: From a systematic vision. Ibero-American Journal of Education & Society Research, 3(1), 238–243. https://doi.org/10.56183/iberoeds.v3i1.622

Gündüz, A. Y., & Akkoyunlu, B. (2020). Effectiveness of gamification in flipped learning. SAGE Open, 10(4), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020979837.

Guo, J.-L.; Hsu, H.-P.; Lin, M.-H.; Lin, C.-Y., & Huang, C.-M. (2020). Testing the usability of digital educational games for encouraging smoking cessation. International Journal Environmental. Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082695

Heinich, R., Molenda, M., Russell, J. D., & Smaldino, S. (2002). Instructional media and technologies for learning (7th ed.). Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Huang, B., Hew, K.F., & Lo, C.K. (2018). Investigating the effects of gamification-enhanced flipped learning on undergraduate students’ behavioral and cognitive engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 27, 1106-1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1495653.

Iwuanyanwu, P. N. (2019). What we teach in science, and what learners learn: A gap that needs bridging. Pedagogical Research, 4(2), em0032. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/5780

Jo, J., Jun, H., & Lim H. (2018). A comparative study on gamification of the flipped classroom in engineering education to enhance the effects of learning. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 26(5), 1626-1640. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.21992

Kang, J., Salonen, A., Tolppanen, S., Scheersoi, A., Hense, J., Rannikmäe, M., Soobard, R., & Keinonen, T. (2023). Effect of embedded careers education in science lessons on students’ interest, awareness, and aspirations. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 21(1), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-021-10238-2

Klock, A. C. T., Ogawa, A. N., Gasparini, I., & Pimenta, M. S. (2018). Does gamification matter? A systematic mapping about the evaluation of gamification in educational environments. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, 2006–2012. https://doi.org/10.1145/3167132.3167347.

Lacovides, I., Aczel, J., Scanlon, E., Taylor, J., & Woods, W. (2011). Motivation, engagement and learning through digital games. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments, 2(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4018/jvple.2011040101

Lee, G. G., Jeon, Y. E., & Hong, H. G. (2021). The effects of cooperative flipped learning on science achievement and motivation in high school students. International Journal of Science Education, 43(9), 1381–1407. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2021.1917788

Lei, H., Chiu, M. M., Wang, D., Wang, C., & Xie, T. (2022). Effects of Game-Based Learning on Students’ Achievement in Science: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 60(6), 1373-1398. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331211064543

Lim, D., Sanmugam, M., Wan Yahaya, W. A. J., & Al Breiki, M. S. (2024). Redesigning Malaysian university students’ player traits from the perspective of game theory: A qualitative study. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 14(4), 552-558. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2024.14.4.2076

Lo, C. K., & Hew, K. F. (2018). A comparison of flipped learning with gamification, traditional learning, and online independent study: the effects on students’ mathematics achievement and cognitive engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(4), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1541910

Majdoub, M., & Heilporn, G. (2024). How does gamified L2 learning enhance motivation and engagement: A literature review. In Z. Çetin Köroğlu & A. Çakır (Eds.), Fostering Foreign Language Teaching and Learning Environments With Contemporary Technologies (pp. 134-173). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-0353-5.ch007

Maratou, V., Ennami, F., Luz, F., Abdullahi, Y., Medeisiene, R. A., Sciukauske, I., Chaliampalias, R., Kameas, A. D., Sousa, C., & Rye, S. (2023). Game-based learning in higher education using analogue games. International Journal of Film and Media Arts, 8(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.24140/ijfma.v8.n1.04

Marcourt, S. R., Aboagye, E., Armoh, E. K., Dougblor, V. V., & Ossei-Anto, T. A. (2022). Teaching method as a critical issue in science education in Ghana. Social Education Research, 4(1), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.4120232058

Maxwell, M. (2024). The effects of a gamified flipped classroom on first-generation low income student motivation and achievement in a Georgia High School Mathematics Class. [Tesis de doctorado, Georgia State University]. https://doi.org/10.57709/36975836

Mulyanti, F., Abidin, Y. D., & Suharto, N. (2023). Pengaruh flipped classroom berbasis gamifikasi dan motivasi belajar terhadap hasil belajar IPA. Pendas: Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Dasar, 8(1), 4207-4219. https://doi.org/10.23969/jp.v8i1.7594

Nilubol, K. (2023). The feasibility of an innovative gamified flipped classroom application for university students in EFL context: An account of autonomous learning. English Language Teaching, 16(8), 24-38. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v16n8p24

Nipo, D., Gadelha, D., Da Silva, M., & Lopes, A. (2023). Game-based learning: possibilities of an instrumental approach to the FEZ game for the teaching of the Orthographic Drawings System Concepts. Journal on Interactive Systems, 14(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5753/jis.2023.3190

Ortiz, A. M. L., & Aliazas, J. V. C. (2021). Multimodal representations strategies in teaching science towards enhancing scientific inquiry skills among grade 4. International Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 3(3), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.54476/iimrj241

Phang F. A., Khamis, N., Nawi, N. D., & Pusppanathan, J. (2021). TIMSS 2019 Science Grade 8: Where is Malaysia standing? Asean Journal of Engineering Education, 4(2), 37-43. https://doi.org/10.11113/ajee2020.4n2.10

Ranoptri, D., Mustaji, M. , & Syaiful Bachri, B. (2022) Development of web bases inquiry learning with the flipped classroom model in science learning for 7th grade of junior high school. Prisma Sains: Journal Pengkajian Ilmu dan Pembelajaran MIPA IKIP Mataram, 10(2), 316-326. https://doi.org/10.33394/j-ps.v10i2.4942

Rodrigues, L., Arndt, D., Palomino, P., Toda, A., Klock, A., Avila-Santos, A., & Isotani, S. (2022). Affective memory in gamified learning: A usability study. Anais do XXXIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Informática na Educação (pp. 585-596). https://doi.org/10.5753/sbie.2022.225748

Rudolf, E. (2021). Student as a performer of flipped learning in mathematics upgraded with interactive video. Natural Science Education, 18(1), 22-28. https://doi.org/10.48127/gu-nse/21.18.22

Sayeski, K. L., Hamilton-Jones, B., & Oh, S. (2015). The Efficacy of IRIS STAR Legacy Modules under different instructional conditions. Teacher Education and Special Education, 38(4), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406415600770

Siegle, D. (2013). Technology: Differentiating instruction by flipping the classroom. Gifted Child Today, 37(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076217513497579

Solis-Foronda, M., & Marasigan, A. C. (2021). Understanding the students’ adversities in the science classroom. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 8(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2021.81.52.58

Tangkui, R., & Tan, C. K. (2020). Digital game-based learning using minecraft: enhacement of pupils’ achievement in fractions? E-Jurnal Penyelidikan dan Inovasi, 7, 75–90.

Thomas, D. S., & Mahmud, M. S. (2021). Digital game-based learning in Mathematics teaching: a literature review. Jurnal Dunia Pendidikan, 3(3), 158-168.

Toda, A.M., Klock, A.C.T., Oliveira, W., Palomino, P. T., Rodrigues, L., Shi, L., Bittencourt, I., Gasparini, I., Isotani, S., & Cristea, A. I. (2019). Analysing gamification elements in educational environments using an existing Gamification taxonomy. Smart Learning Environments, 6(16), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-019-0106-1

Tsay, C. H. H., Kofinas, A., & Luo, J. (2018). Enhancing student learning experience with technology-mediated gamification: An empirical study. Computers & Education, 121, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.009

Cheng, X. (2023). Flipped learning model: An effective approach to primary school STEM education. Science insights education frontiers, 15(1), 2145-2146. https://doi.org/10.15354/sief.23.co044

Yılmaz, Ö. (2023). The role of technology in modern science education. In Ö. Baltacı (Ed.), Current research in education - VI (pp. 35-60). Özgür Publications. https://doi.org/10.58830/ozgur.pub383.c1704

Yu, Q., & Yu, K. (2023). The effects of gamified flipped classroom on student learning: evidence from a meta-analysis. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(9), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2209791

Yue, W. S., & Wan, W. L. (2015). The effectiveness of digital game for introductory programming concepts. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST) (pp. 421–425). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICITST.2015.7412134

Zhou, X., & Lin, X. (2024). A Survey and study on interdisciplinary learning attitudes of primary school students under the STEM education concept. Journal of Higher Vocational Education, 1(3), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.62517/jhve.202416325