of Technology and Educational Innovation Vol. 8. No. 2.

Diciembre 2022 - pp. 58-68 - ISSN: 2444-2925

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2022.v8i2.12655

Perception of TIC conflicts among secondary school students in a private school. School mediation as a response

INTRODUCTION

The concept of school coexistence appears in Spanish pedagogical historiography in the early twentieth century and it is in the nineties that it begins to postulate from a comprehensive perspective in order to propose solutions to the conflict situation that are beginning to be an unpricedented concern at the schools in our country (Luna-Bernal et al., 2017). Currently, school coexistence is going through a problematic time in our environment, and we are witnessing the progression of conflict inside and outside schools (Merma-Molina et al., 2019). That is why in recent decades the number of proposals, projects and programmes that aim to improve the school climate, management and prevention of conflicts between students has increased significantly, leading to a revealing change from the prism of administrative organization, schools and institutes (Andrades-Moya, 2020; Costa et al., 2020). On the other hand, as Toscano et al., (2019) school performance is an inherent element of educational quality and this in turn has the good climate of coexistence existing in the classroom and in the school, since good relations between members of the educational community generate an atmosphere of harmony that positively stimulates the academic performance of students (Carmona et al., 2020). Sometimes, the term “coexistence” has led to some nuance of inaccuracy (Fierro-Evans, & Carbajal-Padilla, 2019).

However, we want to reaffirm the positioning of Uruñuela (2018) to avoid these terminological ambiguities, noting that we should talk about coexistence in positive and non-positive coexistence, since the first, school coexistence in positive, demands a democratic, peaceful and inclusive harmony while respecting human rights (Ascorra et al., 2016). Meanwhile, if we talk about positive coexistence, pedagogical approaches until now that are always behind events prevail and also do not project anything on the educational level. Therefore, living together is to become aware that we are people, which means the implementation of social competences that seek the best coexistence and the positive management of conflicts that arise.

In the school context, the improvement of coexistence requires the participation of an active student as an essential element, capable of understanding conflict situations and transforming them through dialogue (Sánchez et al., 2019). Delors outlined it in his report (1996) as one of the challenges and educational pillars of 21st century education. The report focuses on the process of learning to live together as the determining axis of the education we must provide to young people to avoid, not only conflict but also the early school drop-out of pupils. Pedagogical experiences promoting an education that pursues the holistic development of students are demanded by an increasingly technological society where violence is very common in our schools and where some of the teachers do not capture conflicting gravity in some situations (Rizo, & Picornell, 2017). We consider the school as an engine of change where it is educated for peace and grooming. The fracture of school coexistence is exhibited from various edges: physical punishments, offenses, emotional abuse, gender-based violence, among others (Galtung, & Dietrich, 2013) and with a varied cast of conflicting behaviours. Different authors (Brandoni, 2017; Garaigordobil, 2019; Medina, & Villarreal, 2019; Vizcarra et al., 2018; Zepeda, 2020), in their research exhibit various and varied typologies on school conflicts, which usually have a very negative impact on adolescents who manifest a weak personality and low self-esteem (Ormart, 2019). Violence is a culturally learned behaviour that has directionality and pursues an end: control, impose, manipulate or intimidate (Campos et al., 2015). Abuse of power and inequality are the basis of this school violence (Garaigordobil, & Oñederra, 2010; Torrego, 2019,).

Undesirable behaviours in school environments are often categorised by teachers as structural problems, as the origins of this school violence are due to exogenous multicausal sources of school life (Uruñuela, 2018) and therefore should not be treated as isolated events. These behaviours require peremptory educational strategies that lead to mitigating the bad climate of school coexistence (Osorio, & Alexander, 2018).

We consider that there is a conflict of school, when a conduct or omission of it, intentionally carried out, causes harm to another member of the educational community (Álvarez-García et al., 2008). Conduct that alters peaceful coexistence daily in classrooms could be classified as follows (Dobarro et al. 2016): disruption, physical, direct and indirect violence, verbal, direct and indirect violence, social exclusion, ICT violence and teacher violence towards students.

One of the most frequent and troubling behaviors that occur in the classroom are disruptive behaviors (Jurado et al., 2020). It is behavior considered violent and almost always intentional. The causes of classroom disruption range from sporadic situations to students with significant behavioral disorders. The point is that it is a very toxic behavior since it prevents teachers from teaching and interested peers from interrupting their learning. Getting up without permission, talking or disturbing and interrupting constantly, are examples of disruption (Nieves, & Gutierrez, 2019).

Between students and at certain times and places, there may be some kind of dispute, pushes, kicks, so we talk about direct physical violence. Indirect physical violence also exists when the damage is done to school materials or to the partner's belongings (Campos et al., 2015; Estrada, & Mamani, 2020). Some research concludes that there is this type of violence in primary education levels (Zúñiga et al., 2019), with students between the ages of 10, 11 and 12.

There is also direct and indirect verbal violence at school, which can be verbal or written, nicknames, offenses, rumours or speaking ill of a community member. It can be done in person, we will then talk about direct and non-face-to-face verbal violence, indirect verbal violence (Nieto et al., 2018). The increase in this type of direct and indirect verbal violence is being alarming in gender relations, as some studies point out in this regard, for example Domínguez-Alonso et al. (2019). Direct or indirect verbal violence may be directed towards teachers.

Studies such as Pachter et al. (2010) and Brandoni, (2017) analyse indicators relating to social exclusion. The level of studies of families, the neighbourhood where you live, the nationality of origin, religion, the usual clothing, the physical aspect or nationality are indicators of educational segregation (Rizo, 2019). The data obtained state that these indicators are continuous elements of exclusion and educational segregation. Exclusionary demonstrations may focus not only within the classroom, but also when students gather in gangs or on social networks the exclusion is the order of the day, although those affected do not report these situations (Pérez, 2017).

All these behaviors have negative consequences that affect the development of the teaching-learning process, they have an impact not only on the low academic performance and even the school failure of repeat students.

The use of mobile telephony by our students, can be the source of inappropriate or violent behaviors through virtual means, connecting to social networks on the Internet where the abuse of power is also clearly manifested (Domínguez-Alonso, & Portela, 2020). Such violent behaviors using ICT tools are varied, from sending offensive messages or images on networks using mobile telephony or other electronic means to recording videos of members of the educational community (Dobarro et al., 2016). It has been the case of recording a teacher with the same intention of uploading it to the network so that in a short time they will go viral.

Mediation mean not only positive conflict management strategy where participating students are involved in achieving positive effects. It is also a proactive tool based on the principles of wilfulness of the students involved, as they come to it voluntarily. The neutrality of the student mediators, who must not position themselves for or against the parties. Confidentiality of all those involved in the process, which implies not commenting on what happens during the mediation process. It is based on active listening as a vector of success where students in conflicts come on their own to achieve their interests and needs from their freely made decisions, enhancing the moral development of students as it is a self-confiscating strategic procedure (Boqué, 2018; Caurín et al., 2019; González-Calderón, 2018; Iglesias, & Ortuño, 2018; Iriarte-Redín, & Ibarrola-García, 2018). Experience in school mediation using different models of action is a reality in our Autonomous Communities (Viana, 2019).

The overall objective has been to see what students’ perception of the use of ICT as a tool is used to generate conflicts and we propose peer school mediation as a proactive instrument of positive conflict management peer school mediation.

MATERIAL AND METHODOLOGY

Our research has been carried out using a type of survey methodology based on the administration of the validated school violence questionnaire (CUVE_ESO) to students from a private-concerted center of the province of Malaga in a middle-class area of social stratum medium worker under. The authors of the questionnaire (Dobarro et al., 2016) manage to discover and analyse the students' perception of the frequency of occurrence of different types of conflicts in the classroom, both among themselves and towards teachers. Our research focuses exclusively on the scale of ICT violence between students and students towards teachers. This questionnaire takes the form of a Likert scale consisting of 44 items with 5 answer options, 1 "Never", 2 "Rare Times", 3, "Sometimes", 4 "Many Times" and 5 "Always”. It is therefore a quantitative methodology with a non-experimental design concerning the analysis of the frequency of emergence of ICT violence between students and students towards the teachers of ESO students from 1st to 4th grade.

Once the test was completed, at the same time that the students delivered the completed questionnaire, the teacher checked that all of them had answered all the items or questions raised.

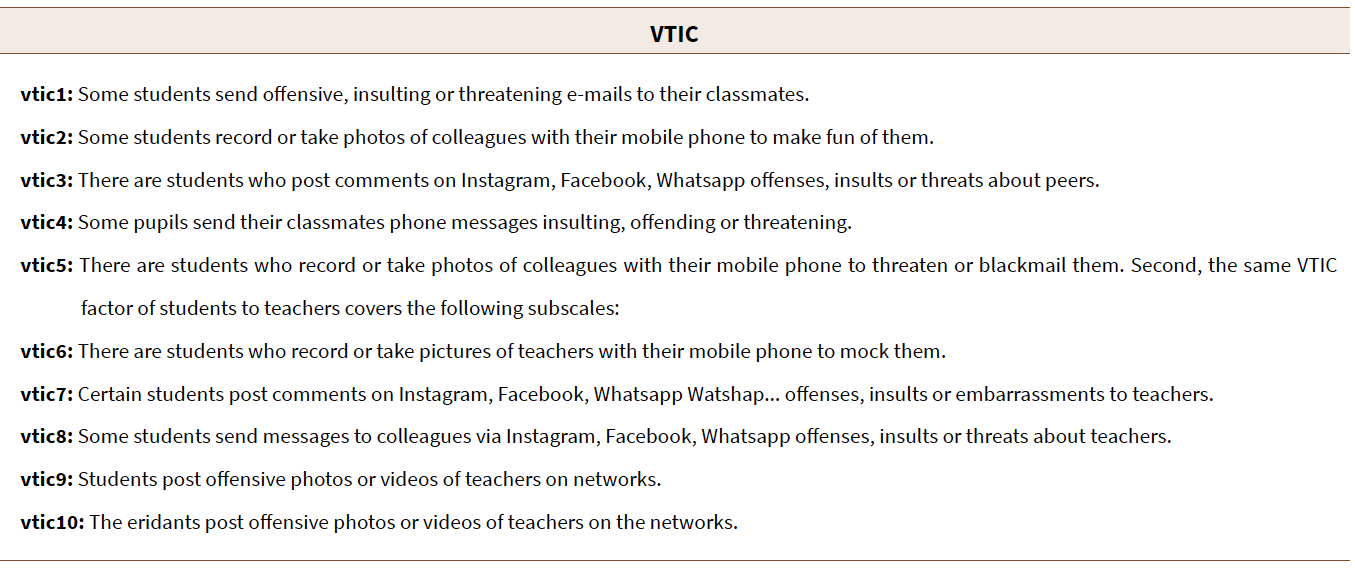

The variable of analysis or scales, school violence through ICTs (SVICT) is composed of the following subscales:

TABLE 1. Description of Subscales

Source: Álvarez-García et al. (2017)

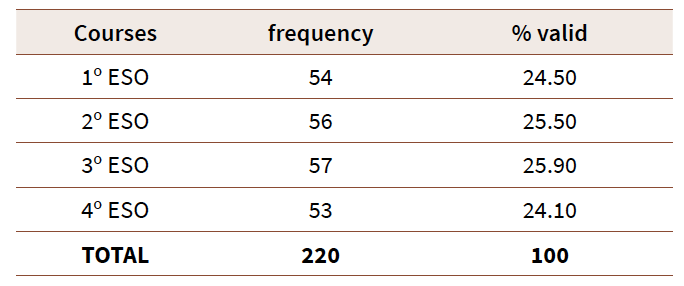

The research was carried out with an incidental sample of 220, 100 students and 120 students, representing 54.50% of students and 45.50% of students. The percentages of distribution of students by course is very homogeneous. Age distribution percentages decrease in 4th year of High School, these courses where older students are located. To carry out our work the questionnaires were applied in June 2019, that is period of the nearly completed course so it could provide information on ICT relations between participating students. Students were motivated to participate in the completion of the questionnaire, explaining what it was and what their objective was, in order to obtain the greatest number of sincere answers (González-Sodis, 2021).

The questionnaire applied to students is answered in about 15 to 20 minutes of an hour of tutoring. It is anticipated that for students who present some difficulty of reading comprehension the teacher in charge can help and increase the time of responses. Table 1 reports the frequency of participation related to the population of interest distributed by course.

TABLE 2. Participation Frequencies

Source: data obtained from the 2019-2020 academic year

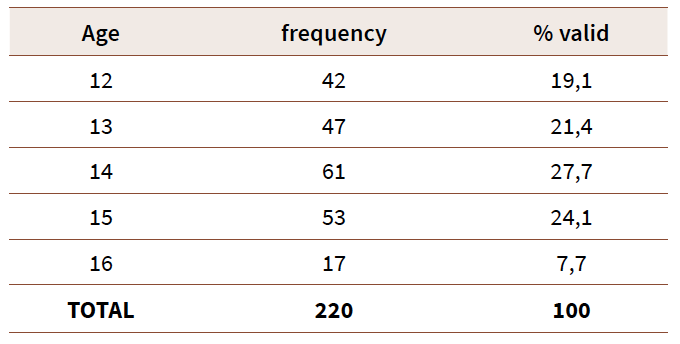

TABLE 3. Age Distribution

Source: data obtained from the 2019-2020 academic year

It proceeded to an analysis of the psychometric properties of the sample distributed by courses and by age (table 2 and table 3), where we obtained the descriptive statistics of the groups and by age. Subsequently, we calculated Cronbach's internal consistency alpha coefficient for the analyzed factor (VTIC) of CUVE3, along with McDonald's Omega coefficient. Similarly, the latent structure of the measurement was confirmed by applying a confirmatory factorial analysis according to the structure of eight factors indicated (Dobarro et al., 2016) to assess the fit of the model, the Chi-square indices were used in relation to their degrees of freedom, RMSEA, SRMR, TLI and CFI (Concrete, 2014; Kaplan, 2009; Shi et al., 2018). Subsequently, each participant's scores for the VTIC factor were calculated, averaging their scores on the items corresponding to those factors. Based on these results, the response profile of participants was analyzed descriptively to analyze the perception of the frequency of this behavior of school violence through ICT, following the objective of study. Finally, the possible existence of differences in the appreciation of the appearance of this violent conduct was explored, depending on the gender and the year level of the participants. For the entire descriptive analysis process as well as reliability and validity analyses, the JASP application (2018) was used.

RESULTS

The internal consistency coefficients for the overall scale were 0.828 for Cronbach's alpha and 0.831 for McDonald's Omega. It can be seen that the values are acceptable for all VTIC subscales.

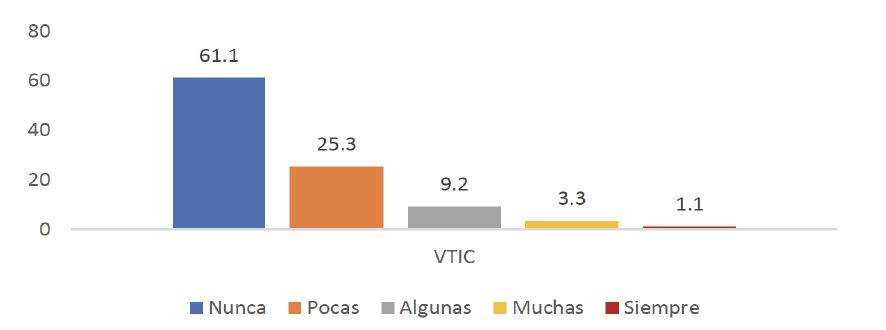

With regard to VTIC, we observe that the average perceived frequency is intermediate (average= 1.58; T.E. Me=0.04), with a positive bias (0.89). VTIC with a not very high frequency is a type of violence carried out outside the classroom and directed at students and to a lesser extent at teachers.. It is concluded that most students have a low level of perception of both student-to-student and student-to-teacher VTIC. In most cases, these behaviours among students are not normalised, they tend to be rare and everyday occurrences, as shown in figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Percentages of the VTIC Factor

The confirmatory factor analysis on a structure of ten subscales in the fit tests yielded a Chi-square value of 166.71 with 35 degrees of freedom, which implies a Chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio of 4.76, and which can be considered as an acceptable fit. The same is true for the fit indices RMSEA=0.131 and SRMR= 0.0767, on the contrary, the indices suggest a low fit. Taking all indices into consideration, a moderate but acceptable fit is assumed.

It can be observed that the frequency of the subscale vtic2 in the classroom or outside it is the highest, "some students record or take pictures of classmates with their mobile phones to make fun" (average of 2.02, standard error of the mean of 0.07). It is noteworthy that the minimum score is 1 and the maximum score is 5 points, showing a slight negative bias (-0.79).

Another aspect to consider is the existence of possible gender differences. Since the distribution of the dimensions cannot be considered normal, the Kruskall-Wallis test was applied. The results showed no significant differences according to the gender of the participants at a 99% confidence level in all subscales except vtc4. A significant difference was therefore obtained at a significance level of 0.05 for the subscales of the VTIC dimension. Therefore, with these results we consider that there is sufficient evidence to consider that there are differences between male and female students.

In the next stage of the analysis process, possible differences between grades were investigated. Here again, no significant differences were found. In vtic1, vtic5 and vtic9, a significant difference was obtained at a significance level of 0.05 for the subscales of the VTIC dimension. Therefore, with these results we consider that there is sufficient evidence to consider that there are differences

To investigate differences in particular, descriptive statistics were calculated for mean (Me), standard deviation (S) by grade and subscales.

These subscale results show a common inverted arc pattern consisting of a lower mean value in the first grade, an increase in the second and third grades, and a decrease again in the fourth grade. The differences are statistically significant, although the effect sizes are relatively low.

It highlights the subclasses of the VTIC factor in Year 3 of ESO, all of which focus on ICT violence among students. So, vtic2, some students record or take photos of classmates with their mobile phones to make fun of them, (with an average of 2.56) vtic3, there are students who post comments on Instagram, Facebook or Whatsapp that offend, insult or threaten classmates, (with an average of 2.95) vtic4, some students send messages to classmates with their mobile phones to make fun of them, (with an average of 2.56) vtic4, some students send messages to classmates with their mobile phones to make fun of them (with an average of 2.56), vtic4, some students send offensive, insulting or threatening mobile phone messages to classmates (with an average of 2.14) and vtic8, some students send offensive, insulting or threatening messages to classmates via Instagram, Facebook or Whatsapp (with an average of 2.26), all of which are close to or above the average value. The minimum score is 1 and the maximum score is 5. In light of the results, it can be concluded that most students have a low level of perception of ICT violence both between students and from students towards teachers. In most cases, these behaviours are not normalised among the student body, so they tend not to be common. With the results obtained in the study, we achieved the initial general objective: to quantitatively analyse the students' perception of ICT violence in compulsory secondary education (ESO) and we have quantified ICTV between students and towards teachers in order to propose school mediation as a positive and proactive conflict resolution strategy. It is significant that without being an alarming conflict, the use of mobile phones and social networks frequented by students is in itself a source and means of conflict, generating spaces of toxic relationships between them. However, the subscales related to teachers vtic6, some students record or take photos of teachers with their mobile phones to make fun of them, vtic7, some students post comments on Instagram, Facebook or Whatsapp with insults or threats to teachers and vtic10, students post offensive photos or videos of teachers on the internet gave insignificant results.

DISCUSSION

The question initially raised focuses on improving coexistence in our schools, given the deterioration that we are gradually seeing occurring in educational environments. Secondary schools are focal points for the reproduction of violence generated in social and family environments. Violence generated in social, family and school contexts has a negative impact on students' academic performance, sometimes being a sufficient cause for early dropout from the education system and consequent school failure (Álvarez-Gómez, 2019; Zepeda, 2020). The findings lead us to consider that although the level of ICT use is increasing, violence caused by electronic media and social networks is not a worrying conflict at our school, although it is not non-existent. Pupils who endure this type of ICT violence have as a result devastating effects on their psychosocial development, as it is violence that can originate at school and continue on social networks, as shown by other studies (González-Carcelen, & Gómez-Mármol, 2019). In the same direction, it has been observed that toxic behaviour with ICT can lead to cyberbullying, a problem that is very difficult to detect (Ortega-Ruíz, & Córdoba-Alcaide, 2017). Like any other type of violence, students exposed to violence through ICTs decrease their ability to integrate into their environment as argued in their study by Sandoval et al, (2017). However, in our study we must highlight the existence of ICT-related violence among students, while that directed towards teachers is not significant or not significant at all. On the other hand, other studies (Domínguez-Alonso, & Portela, 2020) have found a higher incidence in the male gender than in the female gender, with students showing statistically significant differences when they record or take photos with their mobile phones to make fun of their classmates and teachers. Although other studies have not found significant differences between genders when analysing violent behaviour through ICT (Prendes-Espinosa et al., 2020). We can therefore conclude that gender can be considered as a variable to be taken into account when implementing measures to minimise this problem. Violence through ICTs is spreading rapidly among the younger population, possibly due to the amount of time young people spend using technologies and with a greater impact on the female gender (Dominguez-Alonso, & Portela, 2020).

Ortega-Barón et al. (2016), state that violence through ICTs includes actions of abuse of power, discrimination, domination, which can be exercised by both genders and carry risks at the psychological, physical and social level of the individual.

The relationship with the teaching staff, the ICT conflict has not been a conflict that is very much perceived by the pupils, as is shown by the data from our study. A clearly relevant component emerges from the analysis, which is that, contrary to what might seem and what is found in other studies, ICT violence increases in the final years of ESO; the same happens with other types of conflict (Domínguez-Alonso et al., 2019; Medina, & Reverte, 2019). The results are similar to those obtained in other studies (Nieto et al., 2018; Zúñiga et al., 2019) and lead us to reflect that there is a lack of awareness that these behaviours are violent acts towards classmates.

However, school mediation is the right strategy to mitigate school violence. We should use it as a proactive tool that teaches students to discover that in conflict there are possibilities to learn, it is a self-compositive procedure (Arboleda, 2017).

CONCLUSIONS

The proposal for reducing levels of school violence with ICT and positive conflict management, in our opinion, is peer mediation. It requires the involvement of the management team and the educational team as well as the training of students and teachers. Not only does it benefit the victim who has seen his or her rights violated, but the whole group benefits from this procedure as it is an emerging process that applies to new circumstances that arise, except for bullying and cyberbullying.

In our study, we have observed that it is not a conflict that is very much perceived by students. 61% of the students said that they had never perceived it, while 25.3% said that they had perceived it only a few times, i.e. 86.4%. This is a very significant number. This includes both ICT violence among students and violence directed at teachers.

Mediation presupposes a proactive action of inclusion, co-responsibility and participation (Bueno, 2018; Vázquez-Gutiérrez, 2019). Mediation between students has an impact on improving the school environment as it encourages values such as communication, tolerance and self-control (Pérez-Serrano, & Pérez-de-Guzmán, 2011). It encourages dialogue, empathy, commitment and responsibility, which are unquestionable determinants for the improvement of the educational environment; it is a powerful strategy; it results in the improvement of students' social skills. It contributes to greater student involvement in the school and reduces the number of disciplinary proceedings (García-Raga et al., 2019; Torrego, 2018). As in other contexts, peer mediation is based on the principles of voluntariness and free will, equality between the parties, confidentiality and neutrality of the mediating students.

In short, the aim is to actively articulate an active culture of peace based on mediation, conceiving it as an opportunity to promote innovative pedagogical bridges for educational inclusion.

REFERENCES

Álvarez-García, D., Álvarez, L., Nuñez, J. C., González-Pienda, J. A., González-Castro, P., & Rodríguez, C. (2008). Estudio del nivel de violencia escolar en siete centros asturianos de Educación Secundaria. Aula Abierta, 36(1), 89-96. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/2856322.pdf

Álvarez-García, D., Núñez, J. C., & Dobarro, A. (2017, December 14). CUVE3ESO: Manual de referencia [Manual]. https://studylib.es/doc/6031188/manual-de-referencia--versión-2.2----grupo-albor-cohs

Álvarez-Gómez, B. P. (2019). Violencia escolar y el desarrollo socio afectivo de los niños y niñas de la unidad educativa unidad popular periodo 2019 [Proyecto de investigación]. Universidad Técnica de Babahoyo, Babahoyo, Ecuador. http://dspace.utb.edu.ec/handle/49000/7146

Andrades-Moya, J. (2020). Convivencia escolar en Latinoamérica: Una revisión bibliográfica. Revista Electrónica Educare, 24(2), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.24-2.17

Arboleda, A. P. P. (2017). Conciliación, mediación y emociones: Una mirada para la solución de los conflictos de familia. Civilizar: Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 17(33), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.22518/16578953.900

Ascorra, P., López, V., Núñez, C. G., Bilbao, M. Á., Gómez, G., & Morales, M. (2016). Relación entre segregación y convivencia escolar en escuela públicas chilenas. Universitas Psychologica , 15 (1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy15-1.rsce

Boqué, M. C. (2018). La mediación va a la escuela. Hacia un buen plan de convivencia en el centro. Narcea.

Brandoni, F. (2017). Conflictos en la escuela. EDUNTREF. http://eduntref.com.ar/magento/pdf/conflictos-en-la-escuela-digital.pdf

Bueno, A. (2018, June 15). Mediación y menores: mediación escolar [TFM]. Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, España. http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/30759

Campos, J. A., Tass, K. O. M. El, & Cruz, G. de C. (2015). Violência escolar: relações entre bullying e a educação física. Revista Espacios, 36(11), E-1. https://www.revistaespacios.com/a15v36n11/153611E1.html

Carmona, M. A., Castillón, L., & Gutiérrez-Gómez, R. (2020). Los conflictos escolares como factor de riesgo en el rendimiento académico y la deserción escolar. Revista RedCA, 3(7), 82–100. https://convergencia.uaemex.mx/index.php/revistaredca/article/view/14703

Caurín, C., Morales, A. J., & Fontana, M. (2019). Convivencia en el ámbito educativo: aplicación de un programa basado en la empatía, la educación emocional y la resolución de conflictos en un instituto español de enseñanza secundaria. Cuestiones Pedagógicas, 27(27), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.12795/cp.2018.i27.06

Costa, V., Teyes, R., & Zamora, M. (2020). Estudio comparativo entre los programas de prevención de la violencia escolar. In L.M. Reyes, J.A. Durán, J. Carruyo, M. Chirinos, S. Ortega, & D. Plata (Eds). Haciendo ciencia, construimos futuro (pp. 580–591). Universidad de Zulia. https://cutt.ly/pmHrFft

Delors, J. (1996). La educación encierra un tesoro. Informe a la UNESCO de la Comisión internacional sobre la educación para el siglo XXI. Santillana UNESCO

Dobarro, A., Álvarez García, D., & Núñez, J. C. (2016). CUVE3:Instrumentos para evaluar la violencia escolar. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology. Revista INFAD de Psicología., 5(1), 487-492. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2014.n1.v5.710

Domínguez-Alonso, J., & Portela, I. (2020). Violencia a través de las TIC: comportamientos diferenciados por género. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 23(2), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.23.2.25916

Domínguez-Alonso, J., López-Castedo, A., & Nieto-Campos, B. (2019). Violencia escolar: diferencias de género en estudiantes de secundaria. Revista Complutense de Educación, 30(4), 1031–1044. https://doi.org/10.5209/rced.59997

Estrada, E. G., & Mamani, H. J. (2020). Violencia escolar y niveles de logro de aprendizaje en una institución educativa pública de Puerto Maldonado. PURIQ, 2(3), 246–260. https://doi.org/10.37073/puriq.2.3.86

Fierro-Evans, C., & Carbajal-Padilla, P. (2019). Convivencia Escolar: Una revisión del concepto. Psicoperspectivas , 18 (1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol18-Issue1-fulltext-1486

Galtung, J., & Dietrich, F. (2013). Pioneer of Peace Research. Springer.

Garaigordobil, M., & Oñederra, J. A. (2010). La violencia entre iguales. Revisión teórica y estrategias de intervención. Piramide.

Garaigordobil, M. (2019). Prevention of cyberbullying: personal and family predictive variables of cyber-aggression Prevención del cyberbullying: variables personales y familiares predictoras de ciberagresión. Revista de Psicología Clínica Con Niños y Adolescentes, 6(3), 2019–2028. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2019.06.2.1

García-Raga, L., Boqué, M. C., & Grau, R. (2019). Valoración de la mediación escolar a partir de la opinión de alumnado de educación secundaria de Castellón, Valencia y Alicante (España). Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación Del Profesorado, 23(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v23i1.9146

González-Calderón, M. H. (2018). Educar para la paz, una tarea de todos. El Cotidiano, 208(33), 67–77. http://www.elcotidianoenlinea.com.mx/numeros.asp?edi=208

González-Carcelen, C. M., & Gómez-Mármol, A. (2019). Violencia escolar percibida en Educación Secundaria. Escuela Abierta, 23, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.29257/EA23.2020.02

González-Sodis, J.L. (2021). Estudio de la convivencia en un centro educativo concertado: análisis y propuestas pedagógicas para la implementación de la mediación escolar [Tesis Doctoral, Universidad de Málaga]. RIUMA. https://riuma.uma.es/xmlui/handle/10630/23502

Iglesias, E., & Ortuño, E. (2018). Trabajo Social y mediación para la convivencia y el bienestar escolar. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 31(2), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.5209/CUTS.53374

Iriarte-Redín, C., & Ibarrola-García, S. (2018). Capacitación socioafectiva de alumnos y profesores a través de la mediación y la resolución de conflictos. Padres y Maestros / Journal of Parents and Teachers , 373 , 22–27. https://doi.org/10.14422/pym.i373.y2018.003

JASP. (2018). A New Manual for JASP - JASP - Free and User-Friendly Statistical Software. https://jasp-stats.org/2018/09/13/a-new-manual-for-jasp/

Jurado, P., Lafuente, A., & Justiniano, M. D. (2020). Conductas disruptivas en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria: análisis de factores intervinientes. Contextos Educativos. Revista de Educación, 25(25), 219–236. https://doi.org/10.18172/con.3827

Kaplan, D. (2009). Structural equation modeling: foundations and extensions. Segunda edición. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226576.

Luna-Bernal, A. C. A., Mejía-Ceballos, J. C., & Laca-Arocena, F. A. (2017). Conflictos entre Pares en el Aula y Estilos de Manejo de Conflictos en Estudiantes de Bachillerato. Revista Evaluar, 17(1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.35670/1667-4545.v17.n1.17074

Medina, J. A., & Reverte, M. J. (2019). Violencia escolar, rasgos de prevalencia en la victimización individual y grupal en la Educación Obligatoria en España. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias En Educación, 18(37), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.21703/rexe.20191837medina9

Medina, M. A. G., & Villarreal, D. C. T. (2019). Violencia escolar en bachillerato: algunas estrategias para su prevención desde diferentes perspectiva Educación. Teoría de La Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 31(1), 123–147. http://dx.doi.org/10.14201/teri.19616

Merma-Molina, G., Ávalo-Ramos, M. A., & Martínes-Ruiz, M. Á. (2019). ¿Por qué no son eficaces los planes de convivencia escolar en España? Revista de Investigación Educativa, 37(2), 561–579. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/rie.37.2.313561

Nieto, B., Portela, I., López, E., & Domínguez, V. (2018). Violencia verbal en el alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1 (1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.30552/ejihpe.v8i1.221 Violencia

Nieves, Á., & Gutiérrez, A. (2019). Tipos de violencia escolar percibidos por futuros educadores y la relación de las dimensiones de la Inteligencia Emocional. Interacciones Revista de Avances En Psicología, 5(2), e150. https://doi.org/10.24016/2019.v5n2.150

Ormart, E. B. (2019). Violencia escolar y planificación educativa. Nodos y Nudos: Revista de La Red de Calificación de Educadores, 6(46), 25–36.

Ortega-Barón, J., Buelga, S., & Cava, M. J. (2016). The influence of school climate and family climate among adolescents victims of cyberbullying. Comunicar, 24(46), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.3916/C46-2016-06

Ortega-Ruíz, R., & Córdoba-Alcaide, F. (2017). El modelo construir la convivenci para prevenir el acoso y el ciberacoso escolar. Innovación Educativa, 27, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.15304/ie.27.4287

Osorio, V., & Alexander, D. (2018). Actitud y mediación, herramientas fundamentales para la convivencia escolar en el aula de clase [Tesis de Maestría (Magíster en Pedagogía)]. Universidad Católica de Manizales, Manizales, Colombia. http://repositorio.ucm.edu.co:8080/jspui/handle/10839/2141

Pachter, L. M., Bernstein, B. A., Szalacha, L. A., & Coll, C. G. (2010). Perceived racism and discrimination in children and youths: An exploratory study. Health & Social Work , 35 (1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/35.1.61

Pérez-Serrano, G., & Pérez-de-Guzmán, M. V. (2011). Aprender a convivir: El conflicto como oportunidad de crecimiento. Narcea.

Pérez, G. (2017). Manifestaciones y Factores de la Violencia en el Escenario Escolar. Telos: Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinarios En Ciencias Sociales, 19(2), 237–259.

Prendes-Espinosa, M. P., García-Tudela, P. A., & Solano-Fernández, I. M. (2020). Gender equality and ICT in the context of formal education: A systematic review. Comunicar, 28(63), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.3916/C63-2020-01

Rizo, L. J. (2019). Índices de exclusión educativa en el etapa de la ESO en la provincia de Salamanca. Papeles Salmantinos de Educación, 23, 9–29.

Rizo, L. J., & Picornell, A. (2017). Percepciones del Profesorado respecto al bullyingy su relación con la desafección y el fracaso escolar en la Provincia de Salamanca. Prisma Social, 17, 396–414.

Sánchez, A., Alexander, R., López, A., & Patricia, A. (2019). La educación en mediación escolar como escenario de formación ciudadana. Revista Espacios, 40, e21. https://www.revistaespacios.com/a19v40n21/a19v40n21p01.pdf

Sandoval, J., Abril, A., & Leal, H. (2017, March). Violencia en la escuela: creencias y percepciones de docentes y estudiantes [Comunicación]. Actas del Congreso Nacional de investigación Educativa. http://www.comie.org.mx/congreso/memoriaelectronica/v14/doc/1895.pdf

Shi, D., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & DiStefano, C. (2018). The Relationship Between the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual and Model Misspecification in Factor Analysis Models. Multivariate Behavioral Research , 53 (5), 676–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1476221

Torrego, J. C. (2019, May 23). Desde la mediación de conflictos en centros escolares hacia el modelo integrado de mejora de la convivencia. http://diversidad.murciaeduca.es/orientamur/gestion/documentos/articulo_revisado_ceapa_torrego.pdf

Torrego, J. C. (Coord). (2018). Mediación de conflictos en instituciones educativas. Manual para la formación de mediadores. Narcea.

Toscano, D. F., Peña-Nivicela, G. E., & Lucas-Aguilar, G. A. (2019). Convivencia y rendimiento escolar. Revista Metropolitana de Ciencias Aplicadas, 2(2), 62-68. http://remca.umet.edu.ec/index.php/REMCA

Uruñuela, P. M. (2018). Trabajar la convivencia en los centros educativos. Una mirada al bosque de la convivencia. Narcea.

Vázquez-Gutiérrez, R. L. (2019). Objetivos de la Educación para la paz. En R. Cabral, A. I. Arévalo, G. Vilar, & T. Al Najjar (Eds.), Estudios interdiciplinarios: Paz y comunicación. (pp. 378–398). UNESP. https://cutt.ly/pmHyFhp

Viana, M. I. (2019). 25 años de Mediación Escolar en España: 1994-2019. Cuestiones Pedagógicas, 0(27), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.12795/CP.2018.i27.01

Vizcarra, M. . T., Rekalde, I., & Macazaga, A. M. . (2018). La percepción del conflicto escolar en tres comunidades de aprendizaje. Magis. Revista Internacional de Investigación En Educación, 10(21), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.m10-21.pceca

Zepeda, M. Á. C. (2020). Los conflictos escolares como factor de riesgo en el rendimiento académico y la deserción escolar. Revista RedCA, 3(7), 82-100. https://doi.org/10.36677/redca.v3i7.14703

Zúñiga, L. F. S., Rivas, P. L., & Trevizo, J. G. R. (2019). Percepción de la violencia escolar en el último ciclo de educación primaria. Revista Electrónica Cientifica de Investigación Educativa, 4(2), 1349–1360. https://doi.org/10.33010/recie.v4i2.369