The Latest Trends in Spanish Cinema. An Analysis of Film Poduction between 2011 and 2022

Tendencias en el cine español más reciente. Análisis de las producciones cinematográficas entre 2011 y 2022

Ernesto Pérez-Morán

Universidad Complutense of Madrid, Spain

Virginia Guarinos

University of Sevilla, Spain

Abstract:

Despite being so close at hand, the past decade of Spanish cinema can now be addressed quantitatively, and specific numerical calculations reveal a synergy between the production of films, both fiction and documentaries, and their exhibition. By generating a database with all the releases from 2011 to 2022, the aim of this research is to provide a detailed analysis and interpretation of the most significant figures. As such, the results obtained by cross-referencing the data provide a panoramic view of the national cinematic landscape, thereby filling a void that is still unexplored. Although many generic studies delve into the synergy between different types of cinema, while others address the recent Spanish cinematic landscape year by year in an individualized way, only a small amount of research on the issue is transversal, yet it builds bridges between production and exhibition, thereby unifying production figures with the subsequent release. The conclusions drawn indicate that this decade has been a period of inertia and stagnation following a much richer inter-millennial period.

Resumen:

La última década del cine español, a pesar de la cercanía de la misma, es un terreno en el que ya es posible introducirse desde un punto de vista cuantitativo, de modo que a través de ciertos números se puedan revelar sinergias entre la producción de filmes, ficción y documental, y la exhibición. Esta investigación ha generado una base de datos con todos los estrenos desde 2011 a 2022 con el objetivo de radiografiar e interpretar las cifras más significativas. Así, el resultado derivado del cruce de datos ha arrojado una visión dinámica del paisaje cinematográfico nacional, cubriendo un hueco aún inexplotado, en tanto que abundan los estudios generales, los que bucean en las sinergias entre los diferentes cines o aquellos que abordan año a año de forma individualizada el panorama cinematográfico español reciente, pero no hay tantos transversales que tiendan puentes entre la producción y la exhibición unificando las cifras de producción con su estreno posterior. Las conclusiones deducidas apuntan a que esta década es un periodo de inercias procedentes de la más rica etapa entremilenios, una etapa de estancamiento.

Keywords: Spanish cinema; Film production and exhibition; Film co-production; Women filmmakers; Fiction films; Documentary films.

Palabras clave: Cine español; producción y exhibición cinematográficas; coproducciones cinematográficas; mujeres cineastas; cine de ficción; documental cinematográfico.

1. Introduction

The evolution of Spanish cinema has experienced several turning points as a result of the social, political, and ideological changes that have taken place in the country in recent years,. Consequently, key moments of change in the development of Spanish filmaking include the period of transition toward democracy, as well as the era in which the social- democratic party governed, and at the beginning of the new millennium as well[1]. Give this context, while the latter was a highly complex period highlighted by the emergence of social issues, topics, and new genres in Spanish cinema (Sánchez Noriega, 2020), the start of the second decade of the 21st century was defined by the consequences of what has been called the perfect storm in the audio-visual sector in Spain. Pérez Rufí describes the situation as follows:

…The change was brought about by the convergence of several factors, including the severe economic recession, the banking crisis, government cutbacks, and the sweeping digital revolution that changed the structures and processes of the media, as well as the consumption habits of audiences, who have now become users of information and communication (2012, p. 158).

In the same year, the FAPAE (Federation of Spanish Audio-visual Producers) warned of several cross-cutting issues, such as the fact that the sector's turnover in 2010 had fallen by 14.67% compared to the previous year, despite the continued upward trend in the number of production companies. It also pointed out that despite a decline of nearly 4% in overall box office revenue in Spain compared to the previous year, ticket sales grew by 23.5% when contrasted with 2010, thanks to the blockbuster film Torrente 4: Lethal Crisis (Santiago Segura, 2011), which was the highest-grossing film with 19.34 million euros in takings in the year it was released. Moreover, although film production fell by 8% in 2011 compared to the previous year, 6.5% more films were released than in 2010 (FAPAE, 2012).

With this voloatile scenario, as 2012 was a critical year of the economic recession, and as the Spanish government of the time was forced to request economic assistance from the European Union in June (the so-called financial rescue), the result was intense cutbacks that especially affected the world of culture, and cinema as well (Rubio Aróstegui and Rius-Ulldemolins, 2018). One of the most serious measures was the increase in value added tax (VAT) in September, which led many members of the sector to announce the effective death of the system of production, distribution and exhibition of Spanish cinema that had been in place up to that time.

Thus, the time frame of this research starts from about the middle of the economic recession. This was a time when the film sector was especially vulnerable, although the figures did not seem to be as catastrophic as expected, and the legal framework was for once in a phase of certain stability. The reason is that the Film Law 55/2007 of 28 December 2007 (BOE, 2007) had laid the foundation of future film policy and was generally praised, especially from a legal standpoint (López-González, 2008; Díaz González, 2016), thanks in part to the person who had orchestrated its creation, Fernando Lara, who was director of ICAA (Instituto de Cinematografía y de las Artes Audiovisuales) [institute of cinematography and the audio-visual arts].

To complete this legal framework, the main legislative developments worth mentioning are the following: the Ministerial Orders that regulated specific aspects of filmmaking, such as Royal Decree-Law 6/2015, of 14 May, which amended Law 55/2007 (BOE, 2015); and Royal Decree 1084/2015, of 4 December, by which Law 55/2007 (BOE, 2015) was also developed.

Subsequently, the Film Law underwent another reform in 2016 in order to comply with EU regulations, a point to which we will return later in this paper. Furthermore, as a new transposition, in the case of EU Directive 2018/1808 on Audio-visual Communication Services, the General Law on Audio-visual Communication (Law 13/2022, of 7 July) (BOE, 2022) was late in emerging, yet it played a key role in boosting the audio-visual sector. Moreover, this law is contained in the Ministry of Economy's project entitled Spain, Europe's Audio-visual Hub[2]. It also contains the Film Law, as well as the Law on Audio-visual Culture, which will be sent to the Spanish Parliament for urgent processing, and is forecasted to be approved before the end of 2024. Theoretically, both laws are expected to alter the legal framework of Spanish cinema known up to the present time.

2. Justification, objectives and methodology

There are few analyses that detail and draw conclusions from statistics (Medina de la Viña and Fernández García, 2014), and even fewer that address a prolonged period, one of which is the most recent decade. Most analyses explore film exhibition within the general framework of the Spanish market, addressing global numbers or highlighting the power of Hollywood in this country (Gil Ruiz et al., 2024; Augros, 2000; Kogen, 2005). Or, conversely, they focus on different aspects of exhibition, such as technological developments (Perales and Marín, 2012), venues (García Santamaría, 2012), or the impediment of attendance due to algorithms (Cuadrado, Ruiz and Montoro, 2013). Some studies have even differentiated between the audience attendance of national and foreign films (Fernández Blanco, 1996), which is related to analyses that approach our field of study and that address the audience's perception of Spanish cinema (Deltell, Clemente and García, 2016; Clemente and García, 2016; García, Reyes and Clemente, 2014).

Some authors, such as Álvarez Monzoncillo and López Villanueva (2006), as well as Monterde (2019), have mapped out production in periods that serve as precedents or reviews of our time frame, while other studies are more specific, whether from the perspective of subsidies (Heredero Díaz and Reyes Sánchez, 2017) or television funding (Pérez, 2015), to cite two of the most common examples.

This article aims to fill an unexplored void and propose a different approach, given that it analyses the different releases diachronically. The difference is, in addition to this transversal vision, it looks at the year of production rather than the year of release in trying to obtain a consolidated snapshot that gives a reliable account of the situation of Spanish cinema according to the year of production and its consequences, and not so much to take a static image from year to year. Although this decision may be debatable due to its being atypical, it attempts to correct a common problem in the figures, which is that production is necessarily separated from release, whereas if the year of production is taken into account to assess the importance of each film, these two phases are merged, allowing for two derivations: the first, to analyse production and its subsequent release dynamically; and the second, to compare the figures obtained with those of the production, distribution and exhibition sectors based on the first approach, the results of which are presented here.

The main objective of this study is to carry out a mostly quantitative outline of the production of Spanish feature films, both fiction and non-fiction, between 2011 and 2022. From the main objective two secondary objectives are proposed as well. The first is to make an initial interpretation of the data prior to a future analysis in progress. From the initial figures, the aim is to draw inferences with regard to the context in which these figures are given, thereby making connections between the production of feature films and their reception, and locating the focal point between production and exhibition toward the side of distribution. The other secondary objective is to interpret the gender gap and the co-production scenario as core features discovered in the course of the present research, especially the former.

For documentary sources, we have used the invaluable reports issued by the main institutions of the audio-visual sector in Spain, which include the following: ICAA; FAPAE; Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Cinematográficas [the academy of arts and cinematic science]; and CIMA (association of women filmakers and audio-visual media]. However, these data sometimes differ slightly in the figures they provide due to the aforementioned strong connection between production and exhibition, along with other aspects that will be explained below.

To carry out the proposal, a complete register of all productions made in Spain between 2011 and 2022 was carried out, noting the following aspects in order to cross-reference the data: title of the film; director; genre; nationality (whether the financing was entirely Spanish or was a co-production, in which case the percentages of participation are indicated); number of spectators; and the year of production. The corpus of analysis reached a total of 2,343 feature films.

In this regard, some preliminary clarifications related to the sample selected should be presented. The first is that the official data provided by the Spanish Ministry of Culture's catalogue[3] was extracted from feature films, not short films, and only from those released in cinemas; in other words, this includes fiction or documentary films with at least one ticket sold, according to the same database. The ICAA even includes unreleased works in its statistics, which may explain the differences in some of the data. Moreover, although such works are not included in the database, they have been used to assess the difference, or gap, between films released and those produced year by year, while taking into account the possible gap between production and year of release. This data is essential, yet the reason for leaving them out of the sample is due to the fact that the audio-visual panorama could be distorted by a fairly high number of feature films that have not obtained other significant figures, as will be seen in the following sections.

Secondly, linked to this situation is the aforementioned aspect of adhering to feature-length films and avoiding short films, due to a decision regarding the design of the research project and the distinct nature of short films, as the latter ascribe to a different business logic. This difference, in the words of De Vega, makes them “an industry within the industry” (2018, p. 430), without a “commercial guarantee” (2018, p. 431), which is the reason for leaving them out of the present analysis insofar as feature-length films are the main focus of our study. Thirdly, the decision to consider spectators rather than box office revenue, as in previous research, is due to audience attendance not being altered by inflation, which is the case with economic figures, as box office estimates are altered over time.

On the other hand, as the category of Director does not show whether this person is male or female, a second database had to be created with this differentiation, which is an essential requirement for analysing gender issues. Finally, the last clarification concerns the Genre category, which in this case is defined as the classification of the films. This is due to the fact that certain inconsistencies have been found in the genres classification of feature films by the reference database of ICAA. Thus, some films are defined as “comedy”, while others are placed in sub-genres such as “black comedy”, “romantic comedy”, or even hybrid classifications such as “dramatic comedy”. Moreover, there are genres that are somewhat undefined, such as “experimental” and “fiction”, which have forced the authors to place any judgement regarding this section between inverted commas. In defence of these inaccuracies in the official data, the long-standing academic debate about genres and their taxonomic indetermination bears mentioning, which has been the subject of countless studies (Altman, 1984; Neale, 1990). In this regard, we assert that the documentary is not a genre, but a format, in order to avoid future confusion, as explained in one of the last approaches to this disquisition by Bernal-Triviño (2023).

Once the pertinent clarifications had been made, it was time to start extracting data in order to outline the scenario of recent Spanish cinema, which we have organised around five core concepts as follows: number of productions; their box office revenue; differences between fictional works and documentaries; divergence between nationally-produced and co-produced works; and an analytical approach to gender (seen in this case as a social role rather than a structural and textual depiction).

3. Number of productions and box office revenue

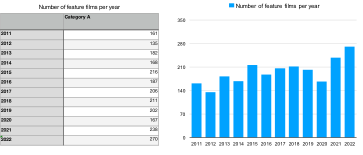

Regarding the films produced in the twelve-year time span of this study, a clear trend can be seen: from 2011 (161 produced) to 2022 (270 produced, the year of greatest production by far), there was an increase which, though not gradual, was nevertheless considerable. Moreover, this trend continued from 2017 onward, which encompassed the entire second half of the period, with the exception of 2020 (167) [F1]. Not in any of the years of the second half was there less than two hundred productions, for a grand total of 2,343 films, which is an average of 195.25 works per year.

F1. Spanish films produced between 2011 and 2022

Source: prepared by the authors from data provided by ICAA.

By delving futher into the number of viewers by blocks, some striking figures emerge: only seven feature films (all fiction) exceeded three million viewers; another seven reached two million spectators; 30 others attained between one and two million filmgoers; the remainder, which comprise 2,299 works, achieved a total of 86,853,170 spectators. Consequently, the top 44 films mentioned above attained far more spectators per film than the rest of the works with a total of 90,015,949 filmgoers, which shows the concentration of the box office in just a few titles. This situation could be described as endemic, given the numbers from previous decades. In Pena's analysis of Spanish cinema in the 1990s, this reality was already evident in that decade, which the author described as “the most disturbing symptom of the Spanish film industry” (Pena, 2002, p. 41).

Another datum reflects the rejection of some works: 387 of the feature films attracted less than 100 spectators (16.5%); the number rises to 1,177 if we count those that did not exceed 1,000 tickets sold (50.23%). In other words, half of the feature films released did not exceed this figure, which makes them completely unviable. Finally, only 263 films sold more than 100,000 tickets (11.22%).

If we take a diachronic view, the box office takings per year [F2] displayed in the graph below are revealing.

F2. Box office revenue per year of the feature films in the corpus

Source: prepared by the authors from data provided by ICAA.

The downward trend is evident, if we consider that in the first six years only 2014 witnessed less than 15 million spectators, yet in the second half of the period, only 2017 comfortably exceeds that amount with 17 million. Moreover, as 2020 and 2021 were heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the figures are highly disturbing, as neither of those years exceeded eight million spectators, the lowest years of all, which only started to improve in 2022 when the figure rose to 13,875,659. For the sake of thoroughness, due to the aforementioned concentration of box office takings in a few titles, it is fitting to analyse the years in which the most successful films were released: Ocho apellidos vascos (Emilio Martínez-Lázaro, 9,397,758 spectators), released in 2014; Lo imposible (Juan Antonio Bayona, 6,129,976), in 2012; Ocho apellidos catalanes (Emilio Martínez-Lázaro, 5,693,198), released at the end of 2015; and Un monstruo viene a verme (Juan Antonio Bayona, 4,613,760), at the end of 2016.

In other words, the four premieres that attracted the largest audiences occurred in the first half of the period studied, so their power to bolster the figures should be considered.

It is possible that this downward trend could have been avoided, as it resulted from the fact that there were no major releases, in addition to the impact of the pandemic. As evidence of this, if we look at the fateful years of 2020 and 2021, the first major release was number 15 of the most successful films, which was Padre no hay más que uno 2: La llegada de la suegra [there’s only one father 2: arrival of the mother-in-law] (2020, 1991. 007). The film was directed by Santiago Segura, who is accustomed to blockbusters that generate this bolstering effect, and two of his films, Padre no hay más que uno (2019) and Torrente (1998), are among the three top films in the history of cinema for 16 to 26-year-olds (AMC, 2021).

Halfway into the timeframe, the 2016 reform of the Film Law went into effecton 1 January 2016. The need for such reform stemmed from the following situation, as explained by Díaz González:

There was a need to update Spanish legislation and adapt it to European regulations on the issue. At this point, a reference should be made to what is known as the “Cinema Communication”. This is the European Commission's Communication on State aid to cinematic and other audio-visual works, which came into force in November of 2013 (Díaz González, 2016, p. 185).

European states had two years to adapt their own legislation to that of the EU, and all the evidence suggests that this reform had no measurable impact on national cinema attendance, except indirectly. Nor can the downward trend be explained without the unquestionable fact of a parallel decline in cinema attendance by the public which, since the 1980s, had continued to fall from 13% to below 5% since 2008 (AIMC, 2020), with the exception of the period from 1998 to 2002.

Finally, one interesting fact is that the gap between films produced and films released [F3] has been a historical indicator of the poor efficiency of the film industry. Unable to absorb endemic overproduction (Fuertes, 1998; Álvarez Monzoncillo and López Villanueva, 2011), the sector steadily decreased from 2011 (134 production) until 2021 (52 works), with a significant upturn in 2023 (75 productions). The upswing in 2023 might have been due to an increase in the number of films released directly to platforms without being screened in cinemas.

The reader can see how the graph below is consistent with the research proposals set forth, as it measures the productions that were or were not released in the same year they were made, or in the following year, thereby unifying both in the cross-reference analysis.

F3. Films produced and released in the period from 2011-2022

Source: prepared by the authors using data provided by ICAA.

4. Differences according to format and co-productions

The tremendous impact of documentaries is striking, as they account for 41% of the productions of the period, with 959 from a total of 2,343. However, this prominence does not correspond proportionally if we look at the total attendance of all these documentaries, which is surprisingly low at 2,358,149 spectators, or 2,459 filmgoers for each production on average. This is even more remarkable if we compare these figures to the total number of spectators of fictional full-length films, which is 181,510,970. Therefore, the percentage of spectators of documentaries is 1.28% (41% of the premieres), out of a total of 183,869,119 total spectators in the period, which is an average of 78,476 filmgoers. These figures have been elevated by fiction, which has an average attendance rate (if we eliminate documentaries) of 131,149 spectators. Lastly, it bears mentioning that we must go down as far as 165th place among the most successful feature films of the period to find the first documentary, which is entitled Eso que tú me das [what you give me] (Ramon Lara and Jordi Évole, 2020), with 218,483 viewers.

For this reason, it is useful to establish differences and calculate not only the average number of viewers for each premiere, but also the median, or central value. The latter reveals an asymmetrical distribution of 984, which indicates that the vast majority of viewers are concentrated in a few titles, as previously mentioned, leaving the average value without much representative power.

Having confirmed the hegemony of fiction over documentaries, we turn our attention to co-productions, which account for 21.6% of the total (506). However, it is striking that only 87 of these co-productions are documentaries (17.20%), with the bulk of the figures concentrated in fiction once again. In other words, only 9% of the documentaries were co-produced.

Of the films that were co-financed by more than one country, Spain's participation was minor on 153 occasions (30.23%); in 13 cases the participation was 50-50 with another country (2.57%); and in the remaining 340 cases the participation was major (67.19%), in which the most common ratio was 80-20, with Spain assuming the first figure. However, in the case of collaboration with France the percentage is usually 90-10, with the majority percentage usually assumed by Spain.

Spain has collaborated with 52 countries in audio-visual productions [F4], with the five most common being France (136), Argentina (100), the United States (49), Mexico (35), and Portugal (32). Spain co-produces films mostly with European and Latin American countries, and occasionally with the following: China, Iraq, Syria, Paraguay, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Lebanon, Mozambique, India, Iceland, Costa Rica, and Guatemala.

F4. The number of co-productions carried out with each country

Source: prepared by the authors based on data from the ICAA.

Regarding the evolution of co-productions [F5] during the years studied, the diachronic view in F5 below shows that the highest percentages are concentrated in the first and last years, with a slight upward trend overall.

F5. Diachronic evolution of co-productions

Source: prepared by the authors based on data provided by ICAA.

5. Gender issues

In terms of authorship by male and female directors, men are still the overwhelming majority. Among films in which there is only one director, 1,720 are directed by a man, and only 361 by a woman. Of all the films with one director, 82.65% are directed by a man, which is one of the most significant findings of this study.

A tally of all choral film signatures yields a curiously similar result, which confirms the existence of inequality. The 262 titles with multiple signatures have a total of 597 participants behind the camera, of which 120 are women and 477 are men [F6], so males also dominate in this category with a very similar figure of 79.90%, slightly lower than the percentage for one-director films. As shown below, this situation has led the authors to extrapolate these figures only for films with a single director.

F6. Comparison of female and male-directed films

Source: prepared by the authors using data provided by ICAA.

Another revealing statistic is the overall number of films directed by male and female filmmakers, which also indicates a gender gap. Excluding co-directed films, the following 22 directors have reached or exceeded five feature films: Carlos Therón (5), Dani de la Orden (8), Daniel Calparsoro (6), David Trueba (5), Emilio Ruiz Barrachina (8), Fernando Colomo (6), Fernando González Molina (6), Fernando León de Aranoa (5), Germán Roda (6), Gonzalo García Pelayo (5), Hernán Zin (7), Isaki Lacuesta (6), Jaume Balagueró (5), Jonás Trueba (6), José María Zavala (5), Pedro Almodóvar (5), Richard Zubelzu (5), Rodrigo Sorogoyen (5), Santiago Segura (7), Ventura Pons (10), Vicente Villanueva (5), and finally, Víctor Matellano (6). Only four women have achieved this goal, which further consolidates the gender gap. The four women include Chus Gutiérrez (6), Icíar Bollaín (6), Isabel Coixet (9) and María Ripoll (5).

Furthermore, the gap is sustained by those who “repeat” the process. A total of 36 men have made four films during the period studied, yet only three women have made four; 58 male directors have made three films, but only 11 women directors have done the same; finally, 187 men have made two films, yet only 49 women have made two. Likewise, leaving the gender issue aside for a moment, the figures of frequency also reveal a worrisome situation: Although 991 of the individually-signed films were made by filmmakers who have produced two or more feature films, 1,090 of the feature films were signed by an individual filmmaker who has only made one film, which indicates that the majority of the industry relies on a single director behind the camera, making it impossible to create long-lasting and stable filmographies.

By cross-referencing the data regarding films made by only one male director, these productions achieved a total of 163,851,869 spectators, or an average of 95,262.7 per film. By contrast, women achieved a much lower total of 13,132,266 spectators, with an average of 36,377.4. This could be due to the fact that women focus more on producing documentaries, which generate less revenue. However, the data do not support this assumption, as the presence of men and women behind the camera in non-fiction productions shows percentages close to the 80-20 ratio observed above: 1,245 documentaries were directed by a man, and 347 by a woman (78.2% vs. 21.8%, respectively).

On the other hand, these findings are consistent with data provided by reports at both the European and national levels. Regarding the former, a report by the European Audio-visual Observatory reveals that “women accounted for 22% of all directors of European feature films who were active between 2015 and 2018” (Fontaine and Simone, 2020). At the national level, similarities can be seen in documents such as “La representatividad de las mujeres en el sector cinematográfico del largometraje español 2021” [the presence of women in the Spanish feature film sector in 2021] (Cuenca Suárez, 2022), and in studies such as those by Coronado Ruiz on the work of the association known as CIMA. This author provides data that clarify the enormous gap, and he offers the following assessment:

In the 35th edition of the Goya Awards (2021), 50% of the prize-winners were women (2022ª, p. 156). Moreover, in 2020, of the 175 feature films produced, 34 were directed by women (19%), while the remaining 141 were directed by men (81%). In grants for feature film projects in 2021, which were mostly aimed at first-time films, 23 projects that were directed exclusively by women received grants, representing 48.94% of the total number of projects. (47) (2022ª, p. 156).

Coronado Ruiz attributes these changes to the Film Law and its successive developments and modifications, and to the work of associations such as CIMA, which for years have been issuing reports that highlight the obstacles encountered by women in consolidating their careers as directors. Moreover, this situation had been observed previously, and it was specifically addressed in another study, also by Coronado Ruiz (2022b, p. 6).

In reference to the classification mentioned above, by establishing differences between men and women according to gender, and insisting on the caution displayed regarding disparity in terms of labelling, some relevant aspects stand out that might explain the imbalance of revenue. Therefore, it is striking that in animation, a genre that grossed 7.5% of the total revenue in the period studied, men were behind the camera in 62 productions, while women were in that position in only five, a discrepancy that increases even more in this clearly male-dominated genre, according to the data. With regard to full-length horror films, 68 productions were shot by men compared to only four by women. In third place is comedy, which also borders on the 90/10 ratio. Moreover, this category is currently, and historically, the highest-grossing genre as reported by the Survey on Cultural Habits and Practices in Spain, 2018-2019 (Ministry of Culture and Sport, 2019). In short, there were 497 films with a man behind the camera, compared to 50 with a woman, yet the latter attained 46.8% of the total audience share, which are figures that in themselves are highly significant.

To finalise the distribution by category, the two main genres are, naturally, the most numerous. While 546 full-length films are dramas (39.45%), 339 feature films are comedies (24.5%), although the aforementioned inconsistencies with regard to dates and classifications of genres, as well as the introduction of different categories, might distort these assessments.

A diachronic reading [F7] with the sole aim of discovering whether the gender gap is narrowing in our cinema speaks for itself, as shown in the following graph.

F7. Diachronic evolution of male and female representation

Source: prepared by the authors based on data from ICAA.

By looking at the bar graph in F7, a minor improvement in the gap can be seen, as women’s numbers rose slightly over time. However, if we look at the table in F7, the gap in the percentage of women per year has remained unchanged at around 20%. When the number of women increases, it is usually because the number of films rises, which does not necessarily imply a reduction in the gap, but a change in production. Nevertheless, the gap has at least become more narrow by slightly more than 10% compared to 2011, although it is still insufficient.

6. Conclusions

With certain exceptions that have failed to halt the upward trend, this study has found a gradual increase in film production over the years, as well as a clear concentration of box office revenue in a few titles. This agglomeration indicates a dependence of the profits on a few releases that “bolster” the rest, in addition to many titles that are so obscure that they are completely unviabile in terms of earnings. On the other hand, a downward trend has been noted in the box office receipts for the period analysed, yet with a slight upturn in recent years, along with a progressive reduction in the gap between films produced and those released.

Although documentaries comprise 41% of the releases, they account for only 1.28% of filmgoers. These lopsided numbers are accompanied by another very low percentage in terms of co-produced documentaries, which are less than one in ten, and ten points below the 21.6% for co-productions on the national scene. The latter figure is due to a percentage formula that is commonly used by Spain and its usual partners in other countries of Europe and Latin America. Moreover, we have found a certain upward trend in the period studied, which is proportional to the percentages of general production, including fiction and documentaries.

Regarding the gender gap, the 80/20 ratio found between men and women occurs in films with one director, as well as those signed by two or more, and even among directors who exceed five films made in the period analysed, which highlights the enhanced difficulty for women in achieving a stable and long-term filmmaking career. Moreover, this issue extends to the total number of films, most of which are directed by filmmakers who never make a second feature film. Considering these obstacles faced by women, it is no surprise that when looking at the data individually, women directors generate less revenue, especially due to the concentration of “gender in the genres”, as men direct more horror, comedy, and animation, which are three of the most successful categories of the period analysed.

In summary, the diachronic assessment reveals that the gender gap is becoming narrower, yet the process is very slow and gradual, a result of the fifth core concept outlined in the introduction section of this article. Moreover, not only does the number of productions seem permanently oversized, but the box office takings reveal inequalities, which are exacerbated by the gap between fictional works and documentaries with regard to the audiences of both, as well as to co-production strategies. The figures for Spanish cinema between 2011 and 2022 were subject to inherent tendencies and reactionary practices, which forbodes an uncertain horizon in the coming years, including a multitude of participants and a change in the legal framework. Undoubtedly, we are going through a period of transition, the duration of which is unpredictable, and its future uncertain. As a closing idea, we leave the reader with the disturbing, though probable future trend, which is that many of the great filmmakers of the decade in question, at least in the second half of the period studied from 2017-2022, have slowly gravitated toward directing fictional series for streaming platforms in Spain, in addition to making films that are released directly onto these platforms as well, without ever going through the traditional and long-standing ritual of being screened in a real cinema.

Bibliographic references

AIMC (2020). Marco General de los Medios en España. https://www.aimc.es/a1mc-c0nt3nt/uploads/2020/01/marco2020.pdf

Altman, R. (1984). A Semantic/Sintactic Approach to Film Genre. Cinema Journal, 23(3), 6-18.

Álvarez Monzoncillo, J. M. y López Villanueva, J. (2006). El audiovisual español: Nuevas oportunidades en el exterior. En Bustamante, E. (Ed.). La situación de la industria cinematográfica española: políticas públicas ante los mercados digitales (pp. 115-131). Fundación Alternativas.

Álvarez Monzoncillo, J. M. y López Villanueva, J. (2011). Informe sobre el estado de la cultura española y su proyección global 2011. Marcial Pons.

AMC Networks (2021). Los españoles y el cine: estudio sobre hábitos y preferencias cinematográficas. https://amcnetworks.es/noticias/amc-networks/la-ciencia-ficcion-y-las-sagas-lideran-las-preferencias-cinematograficas-de-los-espanoles/

Augros, J. (2000). El dinero de Hollywood: Financiación, producción, distribución y nuevos mercados. Paidós Ibérica.

Bernal-Triviño, A. (2023). Aportación del formato talk show y documental en el relato de la violencia machista. La denuncia televisada de Ana Orantes y Rocío Carrasco. Comunicación y Género, 6(2), 101-111.

Clemente Mediavilla, J. y García Fernández, E.C. (2016). Contribución de los sitios web de la industria cinematográfica española a la percepción del Cine Español. ZER, 21(40), 67-83. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.16410

Coronado Ruiz, C. (2022a). Más mujeres en el cine: CIMA y su trabajo en positivo para cambiar lo negativo. Área Abierta, 22(2), 155-171, https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/arab.79078

Coronado Ruiz, C. (2022b). Impulsando el talento femenino. Nuevas directoras en el cine español del siglo XXI. Visual Review, 12 (1), 2-13. https://doi.org/10.37467/revvisual.v9.3708

Cuadrado, M., Ruiz, M.E. y Montoro, J.D. (2013). Factores inhibidores de asistencia a las salas de cine. un análisis regional a través de un algoritmo CHAID. Revista de la Asociación Helénica de Ciencia Regional, 4(1), 55-66.

Cuenca Suárez, S. (2022). "La representatividad de las mujeres en el sector cinematográfico del largometraje español”. Cima. https://cimamujerescineastas.es/informe-cima-2018-la-representatividad-de-las-mujeres-en-el-sector-cinematografico/

Deltell Escolar, L., Clemente Mediavilla, J. y García Fernández, E.C. (2016). Cambio de rumbo. Percepción del cine español en la temporada 2014. Pensar la Publicidad, 10, 77-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/PEPU.53775

De Vega de Unceta, A. (2018). La percepción del cortometraje por los profesionales del cine español. Fotocinema, 17, 429-456. https://doi.org/10.24310/Fotocinema.2018.v0i17.5122

Díaz-González, M. J. (2016): Política cultural y crisis económica: algunas reflexiones a propósito de la reforma de la Ley del Cine. Icono 14, 14 (2), 182-203. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v14i2.975

FAPAE (2012). Memoria Anual 2011. https://blogs.uji.es/rtvv/files/2014/01/MemoriaFapae2011.pdf

Fernández Blanco, V. M. (1996). Documentos de trabajo, 118. Universidad de Oviedo. https://econo.uniovi.es/biblioteca/documentos-trabajo-ccee-ee/1996

Fontaine, G. y Simone, P. (2020). Female directors and screenwriters in European film and audiovisual fiction production. European Audiovisual Observatory.

Fuertes, S. (1998). Entrevista con Enrique González Macho, El País, suplemento Babelia, 4.

García Fernández, E.C., Reyes Moreno, M. y Clemente Mediavilla, J. (2014). Público y cine en España. Problemas de identidad y marca para un cine propio. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 20(2), 695718.

García Santamaría, J. V. (2012). La reinvención de la exhibición cinematográfica: centros comerciales y nuevas audiencias de cine. Zer, 17(32), 107-119.

Gil Ruiz, F., Gil-Alana, L., Hernández-Herrera, M. y Ayestaran Crespo, R. (2024). A Look at the Spanish Film Industry and its Level of Persistence. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11 (66), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02563-4

Heredero Díaz, O. y Reyes Sánchez, F. (2017). Presente y futuro de las subvenciones a la industria cinematográfica española. Fotocinema, 14, 341-363. https://doi.org/10.24310/Fotocinema.2017.v0i14.3604

Kogen, L. (2005). The Spanish Film Industry: New Technologies, New Opportunities. Convergence, 11(1), 68-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/135485650501100106

Ley 13/2022, de 7 de julio, General de Comunicación Audiovisual (2022). Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), 163, 8 de julio. https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2022-11311

Ley 55/2007, de 28 de diciembre, del Cine (2007). Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), 312, 29 de diciembre. https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2007-22439

López-González, J. (2008). Ley del Cine 2007. En C. Padrós, y J. López-Sintas (Dirs.), Estudios sobre Derecho y Economía del cine. Adaptado a la Ley 55/2007 del cine (pp. 177-207). Atelier Libros Jurídicos.

Medina de la Viña, E. y Fernández García, J. (2014). Nuevo cine español: cine, cine, cine, más cine, por favor. Fonseca Journal of Communication, 9, 85-117.

Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte (2019). Encuesta de Hábitos y Prácticas Culturales en España 2018-2019. https://www.cultura.gob.es/dam/jcr:fe7a20bc-a18d-4d1c-9376-77dc684b5dd8/encuesta-de-habitos-y-practicas-culturales-2018-2019.pdf

Monterde, J. E. (2019). La producción cinematográfica. Elementos para la reflexión. En C. F. Heredero (Ed.), Industria del cine y el audiovisual en España. Estado de la cuestión. 2015-2018. Festival de Cine de Málaga e Iniciativas Audiovisuales, 23-114.

Neale, S. (1990). Questions of Genre. En O. Boyd–Barret y Ch. Newbold (Eds.), Approaches to Media: A Reader. Arnold.

Pena, J. (2002). Cine español de los noventa. Hoja de reclamaciones. Secuencias: Revista de historia del cine, 16, 38-53.

Perales Bazo, F. y Marín Montín, J. (2012). La exhibición cinematográfica en el contexto ibérico. Tendencias actuales y futuras. Icono14, 10(1), 94-104. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v10i1.138

Pérez, X. (2015). La convergencia del cine con la televisión: esquemas de producción, financiación por las cadenas privadas, trasvases profesionales. adComunica. Revista Científica de Estrategias, 10, 157-162.

Pérez Rufí, J. P. (2012). La tormenta perfecta del cine español. La situación de la industria cinematográfica en España. Razón y Palabra, 81, 146-162.

Real Decreto-ley, el 6/2015, de 14 de mayo, por el que se modifica la Ley 55/2007, de 28 de diciembre, del Cine (2015). Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), 116, 15 de mayo. https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2015-5368

Real Decreto 1084/2015, de 4 de diciembre, por el que se desarrolla la Ley 55/2007, de 28 de diciembre, del Cine (2015). Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), 291, 5 de diciembre. https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2015-13207

Rubio Arostegui, J. A. y Rius-Ulldemolins, J. (2018). Cultural Policies in the South of Europe after the Global Economic Crisis: Is there a Southern model within the framework of European convergence? International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26 (1), 16-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1429421

Sánchez Noriega, J. L. (Ed). (2020). Cine español en la era digital: Emergencias y Encrucijadas. Laertes.

[1] This research is part of the project New narratives, screens and social realities in Spanish cinema from 2011-2022 (PID2023-148752NB-I00) funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities. This project aims to culminate a fifteen years research and five projects, including this last one, about the study of Spanish cinema as an ideological vehicle, as a constructor of meanings and, in short, as a palimpsest of the last years of national celluloid history. Starting in 2009, the chain of projects has spanned from 1966 to the present, covering a time span that began with late francoism, followed by the democratic transition and continued to address the cinema produced during the first socialist era and the hinge between centuries, culminating with the last decade of our era.

[2] https://spainaudiovisualhub.mineco.gob.es/es/home

[3] https://sede.mcu.gob.es/CatalogoICAA