Visual archives towards the recovery and reactivation of artistic and pedagogical heritage at the School of Fine Arts in Porto

Los archivos visuales en la recuperación y reactivación del patrimonio artístico y pedagógico en la Escuela de Bellas Artes de Oporto

Cláudia Lima

Universidade Lusófona do Porto, Portugal

claudiaraquellima@gmail.com

Susana Barreto

Faculdad de Bellas Artes, Universidad Porto, Portugal

susanaxbarreto@gmail.com

Eliana Penedos-Santiago

Escola Superior de Artes e Design, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, Portugal

elianapenedossantiago@gmail.com

Abstract:

This article reviews the development of a visual archive within the scope of a funded project Wisdom Transfer that was realised at the Faculty of Fine Arts (FBAUP), University of Porto, in Portugal from 2018 to 2021. The project’s directional objective was to research on the pedagogic environment at the faculty during key years preceding the Revolution of 25 April 1974, towards recovering and reactivating the connected historical, empirical, and technical heritage – which had had a pivotal influence on the maturation of the faculty’s now distinctive cultural identity.

The visual archive was based on photographic and audio-visual materials gathered through a series of interview-based sessions with noted artists who were associated with the faculty during the indicated period as either teachers or students.

The photographic materials included both original imageries belonging to the period, and contextual pictures taken during the project period, and became generative resources for both the reconstruction of pedagogic histories, and their reinterpretation in contemporary contexts of creative education. The article, thereby, concatenates the methodological elements that were instrumental in the articulation of the visual archive, alongside a number of key project outputs towards highlighting the efficacy of photographs and photography in conducting social research.

Keywords:

Photographic archive; Image analysis; Photography and Visual History; Porto School of Fine Arts; Life stories.

Resumen:

Este artículo aborda un conjunto de metodologías de análisis visual utilizadas para la recuperación y reactivación de las prácticas artísticas y pedagógicas que han marcado la Escuela Superior de Bellas Artes de Oporto (ESBAP) a lo largo de las décadas de 1960 y 1970, período señalado por la Revolución política, social y cultural del 25 de abril de 1974.

Las metodologías de investigación aquí presentadas han sido introducidas en el ámbito del proyecto de investigación Transferencia de Sabiduría: hacia la inscripción científica de los legados individuales en contextos de reforma de la educación superior y de la investigación en arte y diseño, desarrollado entre julio de 2018 y enero de 2021. Este proyecto tuvo como objetivo establecer las bases para el reconocimiento, comunicación y activación de contribuciones a la cultura y sociedad de artistas y profesores de arte y diseño portugueses, titulados en ESBAP, y actualmente jubilados, a partir de sus conocimientos y experiencia. Este estudio se basa en tres ejes esenciales: (i) el hecho de que el período estudiado fue especialmente importante para la Escuela, ya que en esta época se definió una vocación y una orientación pedagógica particular que dio lugar a lo que hoy se reconoce como una identidad propia, un factor de distinción con respecto a otras escuelas de arte en Portugal; (ii) el hecho de que no existe un registro documental de este notable periodo de ESBAP, escrito y pictórico, con el conocimiento y patrimonio visual que caracterizó a este período a punto de desaparecer considerando la mayor edad de los protagonistas de esta historia; (iii) el deseo de recuperar las prácticas pedagógicas del citado período y experimentarlas en contextos pedagógicos actuales (Alvelos, Barreto, Chatterjee, & Penedos-Santiago, 2019).

Las aportaciones se obtuvieron mediante entrevistas etnográficas realizadas a 43 artistas, alumnos de ESBAP en este periodo. Estas entrevistas se realizaron mayoritariamente en sus casas o estudios, lo cual nos permitió: aplicar métodos de observación directa e indirecta; obtener un conjunto de observaciones únicas en las declaraciones de los entrevistados; y presenciar de primera mano las prácticas que caracterizaban el proceso creativo de estos entrevistados constituyendo una parte integral de las metodologías que utilizaban en el ámbito académico como profesores. Todo el proceso de entrevistas se documentó mediante fotografías y registros de vídeo para su posterior análisis. Estos materiales fueron esenciales, no sólo para el proceso de investigación, sino para su futuro empleo en talleres y documentos creados con el objetivo de recuperar y reactivar las prácticas pedagógicas de las décadas estudiadas y realizar la transferencia de conocimientos entre la generación estudiada y las actuales generaciones de estudiantes de arte y diseño.

También se recopilaron y analizaron imágenes fotográficas de los álbumes privados de los entrevistados y de los familiares de los artistas que tuvieron un papel destacado en este periodo pero que ya han fallecido. Estas imágenes ayudaron al entrevistado a describir eventos pasados, registrados en fotografía, activando otros recuerdos espontáneos y el recuerdo de hechos asociados.

Todos los materiales visuales y audiovisuales recogidos y producidos se reunieron, dando lugar a dos archivos distintos: el primer archivo se basó en la recopilación de imágenes de los años sesenta y setenta; el segundo archivo se compuso de imágenes actuales obtenidas durante las entrevistas. Los dos archivos se proponen preservar un patrimonio individual, material e inmaterial, de estos artistas y diseñadores que “han marcado” la historia del arte y el diseño local, y su utilización en nuevos enfoques exploratorios de investigación que conduzcan a la inscripción de su legado.

A continuación se transcribieron y analizaron las entrevistas, y los testimonios de los entrevistados se organizaron en función del periodo de asistencia a la ESBAP y de un conjunto de temas abordados, entre ellos: el entorno educativo, fuentes de inspiración en la época, vínculo entre profesores y alumnos, cuestiones de género, actividades y eventos extracurriculares, viajes de estudio en el contexto escolar (dentro y fuera del país), talleres extracurriculares en la ESBAP, reuniones de la comunidad académica en cafeterías y estudios de profesores, primeras experiencias pedagógicas en el área de Diseño, formación del curso de Diseño (Arte Gráfico).

Las imágenes de los dos archivos se analizaron y organizaron según estos temas para una mejor contextualización. En una primera fase, se crearon moodboards con grupos de imágenes representativas de estos temas, permitiendo un análisis preliminar de las imágenes, en forma colectiva e individual, al que siguió un análisis más detallado de la narrativa interna, es decir, del contenido de cada fotografía. Siempre que posible, se analizó además la narrativa externa de estas imágenes, intentando determinar el periodo de su registro, por quién y por qué, un análisis que ha resultado más difícil ya que muchos de los autores de las imágenes han fallecido y las respectivas imágenes fueron facilitadas por sus familiares, que desconocen las historias que se ocultan tras los registros.

Los resultados del análisis de las imágenes se cruzaron con los resultados obtenidos en las entrevistas. Esta combinación de métodos permitió recuperar un conjunto de historias vividas en ESBAP en los años 60 y 70, fundamentales a la construcción de la historia local del Arte y del Diseño. La construcción de los dos archivos resultó en una parte fundamental del proyecto Transferencia de Sabiduría, crucial para la consecución de los objetivos propuestos: ayudó a recuperar las historias de estos artistas y diseñadores; fue una herramienta auxiliar para la difusión de los resultados del proyecto en conferencias y publicaciones nacionales e internacionales; contribuyó para el registro, la inscripción y la perpetuación de las historias locales del arte y diseño; aportó un soporte esencial para la realización de talleres desarrollados con el objetivo de realizar la transferencia de conocimiento de una generación marcada por el período revolucionario, a las actuales (y futuras) generaciones de artistas y diseñadores.

Este artículo reúne los elementos metodológicos fundamentales para la articulación del archivo visual, junto con una serie de resultados clave del proyecto, a fin de evidenciar la eficacia de las imágenes y la fotografía en el desarrollo de investigaciones en Ciencias Sociales.

Palabras clave: Archivo fotográfico; Análisis de imágenes; Fotografía e historia visual; Escuela de Bellas Artes de Oporto; Historias de vida.

1. Introduction

A photograph is for me the simultaneous recognition in a fraction of a second, on the one hand of the meaning of a fact, and, on the other, of a rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that express this fact. (Cartier-Bresson, 2015, p. 29).

This article analyses a specific set of research methodologies that have contributed to the recovery of artistic and pedagogical histories and practices connected with the School of Fine Arts (Escola Superior de Belas Artes do Porto/ESBAP) in Porto, Portugal, that were prevalent during the 1960s and 1970s – an era which preceded and culminated in the political and sociocultural Revolution of 25 April, 1974. This pre-revolution period was marked by a dictatorial and politically repressive regime, and in the context of the school, and of art education in general, these were times when less conventional artistic practices such as forms of abstract art were not encouraged, and despite a few foreign influences, the access to art materials and bibliography was critically limited, with the few accessible resources generally being of poor quality (Lima et al., 2020a).

In conjunction, the research methodologies that were used to retrieve the connected histories and practices of the era were introduced in the context of the funded project Wisdom Transfer: Towards the scientific inscription of individual legacies in contexts of retirement from art and design higher education and research that was developed by the authors at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto between July 2018 and January 2021. The project’s main objective was to establish a basis for the recognition, communication, and activation of contributions to culture and society, in accordance with the knowledge and experience of retired Portuguese artists and teachers of art and design from ESBAP (Alvelos et al., 2019). This investigation was anchored in three essential axes:

· the fact that the period in question had been particularly important for the school, since it was at this time that a vocation and a particular pedagogical orientation was defined which subsequently led to what became the school’s individual identity, a distinguishing factor from other art schools in Portugal;

· the fact that there was no previously written or visual documentation of this key period for ESBAP, and that the knowledge and practical and visual heritage that marked this period was on the verge of disappearing in light of the advanced age of those who played a leading role in this particular History;

· and the researchers’ intention to recover certain unique but superannuated pedagogical practices belonging to the school during this period and reinterpret them for contemporary pedagogical contexts (Alvelos et al., 2019).

The research also put particular emphasis on key methods relating to:

1. the analysis of existing photographic images from the private archives of the interviewees and/or their family members;

2. and the production of context predicated imagery as a complementary means of meaning-making in the research process.

2. Photography as an important tool in social research

From the time of its inception, photography has played a crucial role in social research, becoming a key component of evidence-based documentation procedures. Abbott (2013) describes it as “one of the principal mediums of interpretation” of reality, highlighting the importance of photographic archives as documental accounts of historical events (p. 201). Marques (2018) sees it as a “way of inscribing the visual memory of the past for its forced interpretation in the present” (p. 25).

As a reflection of contemporaneity, photography provides an approach to producing an iconographic inventory of what exists and what existed (Marques, 2018; Sontag, 2012), thereby establishing a substantive link to reality. The capturing of singular moments condenses history in imagery and perpetuates its significance for future observers (Barthes, 2015; Sontag, 2015). In this way, it signifies much more than a statement of fact because the recorded image appeals to observers’ individual sensibilities, and thus, can stimulate interpretation. According to Barthes (2015), photography reveals to us “details that constitute the very material of ethnological knowledge” (p. 37), as through it we can understand, for example, the traditional attire of a certain culture in history.

Hine further observes (2013) that “the picture is the language of all nationalities and all ages” (p. 125), and as such, it may be considered universal. Even if individual memories disappear with the passing of those who carried them, photographs can still certify that certain events took place, and ensure their recollection. Sontag (2015), in this case, notes that “to remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture” (p. 88), because the images of specific moments are the ones that tell and perpetuate history. If memory preserves meaningful images, photography preserves the appearance of these images, contributing to, and fomenting, the memory of events, or of a lived context with meaning (Berger, 2013). Bauret (2018) correspondingly notes that photography not only fixates a specific moment of the event but can be suggestive of what happens before, and what happens after, contributing, thus, to the reconstruction of history. This perception aligns with Berger’s (2013) view that photography is a fragment of a continuum which isolates and affords continuity to a specific moment of an ongoing action or event. Berger subsequently defines photography as an exact record of what has happened and explains that it communicates through “a language of events” whose references are external to itself because they refer to the instances that predated or succeeded the moment portrayed – hence it is a part of a continuum. The power of the photographer resides, then, in the decision to isolate, record, and thus, perpetuate a vista of a specific event/moment, bearing in mind that photography also “invokes what is not shown”[1] (Berger, 2013, p. 20) and, therefore, it tells much more than just what is literally depicted on the image. Thus, Berger (2013) concludes that “every photograph is in fact a means of testing, confirming and constructing a total view of reality” (p. 21). In addition to these observations, the author asserts that photography can also become ambiguous, since “all photographs have been taken out of a continuity” (p. 65), making it necessary to include a caption, or an account of the event for a full comprehension of the story. Therefore, Berger considers photography an irrefutable testimony of an event, but fragile in its meaning, which can be strengthened and complemented by words describing the events. Words and the image then together become the building blocks of a cohesive narrative.

For Barthes (1977), in photography, meaning is primarily presented in two ways: denotative, which corresponds to the literal and explicit meaning in the image; and connotative, which corresponds to the meaning attributed according to cultural associations and symbolic senses, that is, it concerns the way in which society understands and communicates the image. In conformity, Tinkler (2013) states that for understanding the meaning of an image it becomes essential to reflect upon it from different perspectives, including reviewing the explicit and implicit contents of the image wherein the analysis of the implicit requires a spatial and temporal contextualization of the photograph. In this case, the portrayed subjects can supply important testimonies for the interpretation of the image.

In these theoretical insights, the relevance of photography as a means for a (re)construction of history in social research is underlined, grounded in which a set of methodologies that lay emphasis on harnessing the full potential of the discipline as a research mechanism were put into practice to meet key objectives of the project Wisdom Transfer.

3. Methodological approach

Wisdom Transfer, the research in question, relied mainly on ethnographic means to collect relevant data, including related imagery and oral histories. A series of semi-structured interviews were conducted with the artists who attended ESBAP during the 1960s and 70s either as students or professors. Between December 2018 and October 2020, 43 interview sessions were held mainly with former students of Painting and Sculpture, and with students who had attended the starting years of the Design (Graphic Art) course, the first in this area in Portuguese higher education[2]. Many of these interviewees later became teachers at ESBAP, and led several decades of pedagogical activities at the school including during the era in focus (Lima et al., 2022a).

As stated earlier, the interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview script with open-ended questions (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Quivy & Campenhoudt, 2008; Weller et al., 2018), that sought to gain insights on the experience of the artists as students and as teachers; their curricular and interpersonal relationships; their connections with art related entities and art based movements in other countries; influences and impacts of the political scenario in their work; and regarding the first pedagogical practices in the scope of Design at ESBAP (Lima et al., 2020a).

When possible, the interviews took place in personal spaces of the artists, such as their homes or studios, which allowed the researchers to apply direct and indirect observation methods (Quivy & Campenhoudt, 2008); to obtain a set of exclusive observations in the context of the interviewees’ statements; and to witness, first hand, practices that had “characterized their creative processes” which “were integral to the methodologies” they used in teaching (Lima et al., 2020a). The interview format also allowed a comfortable narrative flow to be maintained with the interviewees, encouraging spontaneous readings and interpretations of situations that were relatively personal and, at times, of a sensitive nature.

The interviews were recorded on video and supplementary pictures were taken of the interview process, alongside the artists’ studio spaces, their materials and their produced works. For this purpose, permissions were attained from the interviewees beforehand by means of a formal consent form which explained the objectives of the research and the purpose of the recorded materials, with the results later shared with the participants (Banks & Zeitlyn, 2015; Pink, 2021). These photographic images and videos became instrumental in the creation of tools for acknowledging pedagogical heritage and enabled a systematic documentation of the ongoing research (Tinkler, 2013). They were also used as generative resources in workshops later which the project organised with current art and design students, and wherein the aim was to reactivate pedagogical practices from the decades under study and effectuate a transfer of empirical wisdom from past generations to present (Lima et al., 2020a, 2022b).

The recovery of photographic evidence proved particularly challenging for the research since many interviewees did not own a camera during the period in question, or even if they did, many had misplaced the taken photographs over the years. The project, in response, contacted members of family of the interviewed individuals alongside their former students to obtain a critical mass of period-specific photographs.

Correspondingly, the collated image bank consisted of two main categories, the first being the pictures taken during the interview sessions – of artist spaces, materials, and productions; and the second being the old photographs that originally belonged to the specified period. The image bank which would later be developed into an archive, therefore, represented an evidence base, and consequently, an opportunity to inscribe the aesthetic, technical, and sociocultural legacies of the studied generation, towards informing further explorations in art and design research and pedagogy.

The interviews were subsequently transcribed and analysed. The testimonies were organised chronologically in accordance with the interviewees’ respective periods of attending ESBAP as students and/or teachers. The analysis of the discussions revealed insightful patterns relating to topics such as the evolving dynamics between students and teachers, gender issues, and interdisciplinary exchanges with individuals from other fields of knowledge. In addition, key details also emerged concerning curricular and extracurricular happenings such as events, study trips, and informal meetups in community cafés and artist studios. As would become apparent to the research going forward, a significant number of these proceedings bore influence on the conceptualisation and development of Portugal’s first design course.

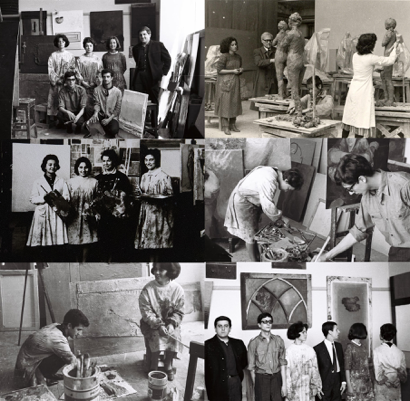

During the analysis phase that followed, the images were further classified into thematic clusters (F1) for cross-referencing with the interviews (Pink, 2021) with a view to establish potential inter-connections and/or emerging narratives.

F1. Mood board with photographes taken in the classroom. Photos from the archives of João Dixo, Gustavo Bastos and Elvira Leite.

Concurrently, an interpretative analysis of the imagery, both at individual and cluster level, was carried out to study and derive meaningful information from the content of the photographs (Banks & Zeitlyn, 2015). Particularly in the case of the old photographs, this information was supplemented, as where possible, by establishing external narratives, such as determining when, where, by whom, and in what context these images were taken.

These narratives were then compared with the anecdotal evidence recorded from the interviews. The blending of the two methods consecutively lead to an interweaving of oral and pictorial histories that afforded a detailed retrospective into the then prevailing learning environment at the school. This would, in turn, help establish a contextual basis for critically evaluating the pedagogical approaches of the era and comprehending the reasons behind what made them distinctive and effective.

4. Visual analysis of images collected

4.1. Archives from the 1960s-1970s

Private photographs, (...) which sacralise the instants of life that are archived in them, allow us to review the dimension of photographic time and the multiplicity and inconstancy of its duration. (...) They are, in themselves, the main reason to ask ourselves what history is made from them. (Marques, 2018, p. 37).

As mentioned before, the images collected from the interviewees were organised and classified according to certain key themes discussed during the interviews: classroom happenings; moments of conviviality particularly in the gardens of the ESBAP campus; and extracurricular events linked to ESBAP, such as field trips, get-togethers, and celebrations of traditional festivals such as Magusto[3]. In this period, photographic recording of daily activities was not common: few students had a camera, and photo processing had a relatively high cost, and thus, it was not accessible for most students. As Rute Dixo, the daughter of artist João Dixo[4], revealed, “my father had a camera, which was unusual for students and, therefore, (some of) these moments were recorded (as a thing of novelty)” (personal communication, February 13, 2021).

Hence, most of the collected photographs portrayed moments exceptionally captured by a small group of people connected to ESBAP, considered, either by those who photographed them or by the subjects portrayed, as instances worthy of photographic record, such as academic tours and trips, celebrations, and Magustos (local festivities).

Other photographic themes included students usually from the same class posing in groups. Some of these images showed teaching exercises in progress; another set of photographs, particularly from artist João Dixo’s archive, depicted convivial moments clearly staged for the camera, involving both students and teachers (F2). According to Rute Dixo (personal communication, February 13, 2021), several of these images that pictured conviviality would later serve as the basis for paintings by João Dixo.

F2. Photograph taken at ESBAP’s garden: Teresa Messeder, João Dixo, Henrique Pichel, Helena Ribeiro Pinto, Helena Almeida Santos. Source: João Dixo’s archive.

From the group of images captured inside classrooms, it was possible to observe and establish a set of period-specific particularities that were also reported in several interviews. One of these particularities was related to the arrangement of the workspaces and materials in the classrooms – the ambience of these rooms resembled artists’ studios, moving away from a conventional more sterile concept of a university classroom. The images revealed workspaces in motion, for example, in painting classes, it was possible to observe finished and unfinished canvases leaning against walls or placed in easels, surrounded by painting paraphernalia such as paint brushes, cans and palettes. In the sculpture rooms, supports on worktables held clay pieces to be sculpted – usually a human figure – and in several areas lay small piles of clay and the tools necessary. The inherent dynamism of the moments within these rooms came to the fore through these pictures, not only because of the predominant presence of the art materials, but also due to subtle and yet divulging details such as traces of paint or clay residues on chairs, floors, and clothing, as previously shown in Figure 1.

The classroom pictures also revealed information regarding clothing, such as a prevalent use of gowns in-class by female students. The regular attire for male teachers and students was suite and tie, with the occasional use of a gown, a practice reported and confirmed by several interviewees.

Additionally, it was also possible to observe some work techniques that correlated with the accounts of the interviewees. A particular example in this regard was when students posed to help their colleagues draw certain parts of the human body, such as hands, which was otherwise difficult to do as expressed by several interviewees (F3).

F3. Photograph taken during a Decorative Painting class: Teresa Messeder poses for Henrique Pichel. Source: João Dixo’s Archive.

Another key thematic area, as briefly discussed earlier, concerned moments of conviviality, especially in the ESBAP garden. Many of these images depicted staged poses and appearances, with a focus on the subjects and not necessarily the background.

Relatedly, photographs of extracurricular activities and events portray instances of leisure, rest, and socialising, as derived primarily from the personal archives of artists Elvira Leite and Alexandre Falcão, both of whom were students at ESBAP during the period. Their images depict jovial instances of singing and dancing, of outdoor walks and occasional outdoor painting sessions, and of Magustos or traditional festivals that were celebrated in-campus at the beginning of the school year, and which contributed to the integration of new students into the ESBAP community. Often, such convivial moments would extend beyond the school walls to cafés and other popular locations around the city, and even to the artists’ personal studios. These instances would additionally provide opportunities conducive to discussing less conventional art forms and having debates on polity which were otherwise curbed under the then prevailing dictatorship.

The pictures further reveal a strong bond existing between students which also, at times, extended to teachers, such as the case of artist and professor Armando Alves posing playfully with students in images derived from João Dixo’s archive. However, the overall relationship between teachers and students was moderately ambiguous. There existed a systemic hierarchy based on the notion of Master and Disciple, thereby, effecting a certain distance between teachers and students (F4). Despite that, in some cases students would frequent cafés with their teachers, and even at times practice in their studios while maintaining the master-student dynamic. Most students, though, would not involve in or benefit from any proximity with their teachers, and some even admitted feeling left out.

Another aspect highlighted by the images is a strong female presence in the student community. ESBAP, at the time, was a school generally considered by parents as inappropriate for girls and, therefore, many potential students were unable to attend (Helena Cardoso, personal communication, May 13, 2021). The primary objection of the parents was regarding the practice of drawing nude models, which went against the time’s conventional family values (Angélica Lima Cruz, personal communication, May 13, 2021). Abetting the situation was a public sentiment that did not view being an artist as a viable profession either for men or women. On this, Rute Dixo recalls that her father “had to face his family to go to [the school of] Fine Arts” since for her family, Painting “was not a course for men... With his intelligence, [João Dixo] should go to medicine or engineering” (personal communication, February 13, 2021).

F4. Photograph taken during a sculpture class held by Master Gustavo Bastos (second, from the left; remaining students unidentified). Source: Gustavo Bastos’ Archive.

The data from the images and interviews, however, indicated significant female interest and involvement in ESBAP, and in certain classes, their numbers were higher than that of male students. Albeit the interviewees’ accounts revealed that many of these students did not eventually complete the 5th year of the course, either because they did not attain the minimum average grade to attend the last year, or because of family commitments they had to withdraw. It is also worth noting that at this time there were no female teachers, and there were several interviewees who mentioned the existence of a prejudice on the part of certain male teachers regarding the presence of women in the school. One of the interviewees recalled a comment from one of her teachers which implied that “…Women are fine to go home to sew socks!” Another interviewee never understood why she was not invited to teach at ESBAP, as she had as good or better grades than the men who were invited.

Although several female interviewees reported situations like these, not all perceived the situation as of prejudice.

It was only after the Revolution of 25 April 1974 that ESBAP began to integrate female teachers into the faculty, however, even today, after more than 40 years, the continued underrepresentation of women in the school’s faculty is yet to be addressed.

4.2. Production of visual records

Photographing the artists in their studios during the interview sessions provided an opportunity for taking portraits that were spontaneous and unprompted, and abounding in meaning laden expressions, gestures, emotions, and other non-verbal means of communicating which was of value to the research. In line with Cartier-Bresson’s method (2006) of depicting subjects un-staged and in their natural settings, the images captured an intimate side of the interviewees’ personalities as they candidly spoke of their life stories and provided a glimpse into their unique thought processes.

The process of gaining trust and consent was not particularly straightforward. Four of the participants did not want to be filmed, and one of them also did not agree to be photographed, or to making notes during the interview, but authorised the reproduction of photographs shown. Another participant allowed notetaking and the production of photographic images of a set of works from his portfolio but did not agree to the photographic documentation of the interview. The other two participants, despite not allowing filming, agreed to the production of photographic images and audio recording during the interview.

And although most interviewees did not raise any objections to being recorded or photographed, in a few cases the project only received partial consent. Among those who did authorize the recording of images and sound, some raised queries on the purpose and future of the collected materials and asked to verify them before making public. Other concerns raised were with respect to storage and ownership, and the publication of images on social media, since regarding particularly the latter, a few had had disconcerting experiences previously. In certain other cases, in order to maintain a natural flow of conversation, and to avoid potential distraction, the researchers paused the photography process as and when required, if any hesitancy on part of the interviewees was detected.

From a technical standpoint, the photographs were captured without flash and in natural or indoor lighting scenarios. Several shot sizes (long shot, medium shot, medium close-up and close-up) and angles (eye level shot, shoulder level, high angle, and low angle) were explored to document the interview process while placing careful consideration to not interfering with the course of conversation.

Keen attention was also given to the home or studio spaces of the artists, where the interviews took place. Elements of these spaces, such as the décor, artefacts, book libraries, work materials, and artworks that were either their own productions or by others whom they admired, together represented references of the artists’ creative provenance, and as such represented valued sources of empiric information for the project. In some cases, a closer inspection of their self-authored works during the interviews, some of which were produced in the relevant era (F5), lead to a rekindling of specific memories that enriched the conversations and provided further insights on connected processual and contextual aspects.

The images consented for publication were eventually reproduced in Wisdom Transfer’s academic and public communications such as in journal and conference articles, project books and website[5], and in its social media page[6] which followed the project’s progress. It was interesting to note that the publications of the images in the social media page derived particular attention and curiosity from the interviewees. Several individuals during their interviews dedicated time to view what was already published on the project’s social media page and commented on their memory of shared instances with the artists that were highlighted.

F5. Photograph taken during the interview with Carlos Barreira, on January 8, 2019: sculpture created by the artist for the Aggregation Exam at ESBAP. Source: Cláudia Lima.

According to Banks and Zeitlyn (2015), photographic contents always tend to provide reasons for conversation, thus, it was natural for these images to trigger memories that complemented the ongoing discourse.

It was also observed during the research that several participants took initiative in referring to certain images from their personal archives that illustrated their life stories. These images not only functioned as an aid to their memory but were also instrumental in spurring further sets of memories of connected personas and events that were not necessarily portrayed in the images.

This conforms with Bauret’s (2018) view on how photographs in a typically chronologically organised family album allow a reliving of the past and become “painfully aware of the distance that separates the times”. Hence, the reading of these old photographs with/of old colleagues and classmates left some of the interviewees with mixed feelings teetering between felicity and wistfulness.

For filming the sessions, a medium shot centred on the interviewee was preferred with a single camera angle maintained to streamline the process and make it less distracting. This approach was based on Margaret Mead’s theory (cit. in Banks & Zeitlyn 2015, p. 106) that “If a tape recorder, camera or video is set up and left in place, large batches of material can be collected without the intervention of the filmmaker or ethnographer and without the continuous consciousness (and possible inhibition) of those who are observed being”. The apparatus hence became a part of the environment, and did not draw any particular attention, and thus allowed for an unhindered flow of communication. In the instances where some of the interviewees became unmindful of the recording in progress, and addressed sensitive subjects, they were intimated, and on their request, these sections were removed during editing.

All edited footage and photographs were integrated into Wisdom Transfer’s visual archive, which became a repertoire of categorical and allegorical evidence that held the collective memories of ESBAP as an institution of eminence during a significant phase in its history – a phase that made a critical contribution to the construction of its now distinctive identity.

5. The applicability of the visual archives

The photographic and audio-visual materials gathered during the project resulted in a bifurcated visual archive, wherein one section of it was dedicated to relevant pictures originally taken during the period in question (1960s and 1970s), and the other consolidated materials produced during the recording of the oral histories.

The archive, during the project period, also acted as a framework for aiding the recollection of period-specific memories and was, thus, often referred to in-situ during active research. However, its main more significant purpose was to document, preserve and activate heritage – the artistic legacy of a generation of creatives and their endowment to the regional social and cultural fabric that was essentially unacknowledged in local contemporary discourses, to an extent that the current generations of art and design students at the school had limited or no knowledge of their existence or contributions (Lima et al., 2020a, 2022b). The archive, thus, provided a basis for safeguarding these legacies for future reference and towards dynamic reinterpretation in contexts of exploratory research and practice by future generations. In it, lay its primary contribution towards inscribing the value of such unparalleled legacies. Despite the Wisdom Transfer project concluding in January 2021, the augmentation of this archive remains a work in motion – primarily due to the reason that the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University Porto (previously ESBAP) did not have provisions for hosting an archive of such nature previously, and at the time writing, the logistics behind instituting it is still under discussion. Also, and as a consequence of the snowball sampling method (Morgan, 2008) that was initially employed during the project period, a further set of details are emerging on an ongoing basis through more individuals indicating willingness to participate, and through the reporting of previously undocumented photographs and recollections by those already interviewed.

In terms of theoretical contributions of the research, key inferences were derived and published on: pedagogical practices at ESBAP in the pre-revolutionary period (Lima, Alvelos, Barreto, & Penedos-Santiago, 2019b; Lima et al., 2020a); the impact of travels abroad on the artistic activity of a generation of students in a dictatorial period (Lima, Alvelos, Barreto, & Santiago, 2019; Lima, Alvelos, Barreto, Penedos-Santiago, & Martins, 2020b); first pedagogical practices in Design in Higher Education (Lima, Alvelos, Barreto, Penedos-Santiago, & Martins, 2021, 2022a); and monographs by Portuguese artists-designers (Lima, Alvelos, Barreto, Penedos-Santiago, & Martins, 2021a; Lima & Barreto, 2019, 2020; Penedos-Santiago & Martins, 2020; Santiago, Alvelos, Barreto, & Lima, 2019). In this domain, the archives have also proved resourceful towards illustrating and complementing presentations made at conferences (Lima et al., 2020a; Lima et al., 2020; Lima, Alvelos, Barreto, & Penedos-Santiago, 2019a, 2019b; Lima, Barreto, & Penedos-Santiago, 2021). The research also had implications towards intergenerational transfer of knowledge, between the generation under study and the current art and design students (Lima et al., 2022b). In this regard, the project organised workshops in two higher education institutions:

· The workshop titled “The narrative possibilities of illustration in transgenerational dialogue” with students from Communication Design, Illustration, and Graphic and Editorial Design courses. The main task was to research and create illustrated narratives of the artists, wherein each student was assigned one artist and had to draw a portrait and develop a graphic novel (Santos, 2020). The students’ research process in this regard included consulting the archive and making a detailed study of their artist subjects’ personality before building an original narrative for the graphic novel (Lima et al., 2022b).

· Another workshop, entitled “Typographic essays as a contribution to the transgenerational transfer of knowledge”, was developed at Universidade Lusófona do Porto with students from the 2nd and 3rd year of the Degree in Communication Design. Here, the students were proposed to develop typographic essays, either digital or manual, based on one or more quotes from the artists’ interviews. Hence, videos were the primary source of sources of information, however, several students also found it pertinent to consult the photographs in order to learn more about the artists’ signature styles and personality and work traits, in order to take more informed and applicable design decisions (Lima et al., 2022b).

Research and dissemination activities under the scope of the Wisdom Transfer project also extended to the public domain, wherein too the archive of photographed images played a central role. The project organised a public exhibition titled “Threads of a Legacy: Towards a pedagogical heritage in Art and Design – the Porto School of Fine Arts, 1956/84” at the University of Porto rectorate in May 2021 where key photographs and visual design productions by the project were presented, including a series of portraits of the artists titled “Retratos Contados” (narrated portraits). The event also provided an occasion to formally present and re-acknowledge the artists and their contributions.

Images from the project’s archive were also published in Threads of a Legacy: Towards a pedagogical heritage in Art and Design - the Porto School of Fine Arts, 1956/84 (Barreto et al., 2021), a book that was launched at the exhibition.

Additionally, another book that compiles and disseminates meaningful and actionable insights from the collected testimonies is being produced, which also refers to the photographic evidence as a means to scaffold, and thus help reconstitute the artists’ oral histories.

These two publications, along with the photographic and video archives, are lodged at the Digital Art Library of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Thematic Repository, University of Porto. This space is a place for the dissemination and preservation of these materials, ensuring access to documentation, consistency in the description of meta-information, and integrated research. We understand that the knowledge potential acquired with this integration is immense, such as the re-writing of history, technological strategies and pedagogical practices of the past.

F6. Photograph taken during the opening of the exhibition of photographic works “Retratos Contados”, at the University of Porto rectorate, on May 17, 2021. Source: Cláudia Lima.

Therefore, to iterate, despite officially concluding in January 2021, the project Wisdom Transfer’s research outcomes, including its visual archive, continue to generate value, and inform further scientific, artistic and pedagogical productions. Going forward, the main aims of the research team are:

· To disseminate the local art and design histories and develop a further set of means to inscribe them in contemporary curricula;

· To further disseminate the research methods and curricular resources created, and promote knowledge and interest among younger generations towards their local creative and cultural heritage;

· To foster a global network of interventions dedicated to the preservation of local art and design narratives.

6. Conclusions

The visual archives created within the project Wisdom Transfer proved to be a fundamental tool to complement the accounts of the interviewees and to understand several aspects related to ESBAP at the time under study such as the environment of the school, materials and work techniques, and evolving dynamics between faculty and students. These images collected from the artists under study and their families as well as those produced during the interview process not only helped in the recovery of the artists’ life stories, but also became essential for the dissemination of the Wisdom Transfer’s outcomes in conferences, publications and exhibitions contributing to the inscription of local histories of art and design, in academic and in public spheres.

Though the project has ended in January 2021, the outcomes are still being disseminated. The workshop model that was created aimed at the transgenerational transfer of knowledge is now being used to disseminate stories of artists from Portugal and abroad in Portuguese universities with art and design courses. Also, partnerships between foreign universities and the researchers of this project are being established under the Erasmus+ Teacher Mobility Grant for Teaching or Training Missions in Europe with the aim of implementing these workshop models abroad and disseminating a further set of local art and design histories. These partnerships began in 2022 and, although some of them have already been implemented, namely in the Strzemiński Academy of Art Łódź in Poland, the possibility of new partnerships is open. Thus, institutions or individuals are invited to contact the authors of this article, if interested towards forming a part of an emerging international network of local art and design histories.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) for funding the project Wisdom Transfer (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-029038), implemented between July 2018 and January 2021.

This article is funded by national funds through FCT, I.P., in the context of the project UIDB/04057/2020.

We thank the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto, for the support and materials made available during the research.

A special acknowledgement to all those who agreed to share their life stories with us, fundamental for the achievement of the objectives of the Wisdom Transfer project, and for the photographic images made available by: Alexandre Falcão Archive, Elvira Leite Archive, Gustavo Bastos Archive, João Dixo Archive.

References

Abbott, B. (2013). A fotografia na encruzilhada. In A. Trachtenberg (org.), Ensaios sobre fotografia, de Niépce a Krauss (pp. 197–202). Orfeu Negro.

Alvelos, H., Barreto, S., Chatterjee, A., & Penedos-Santiago, E. (2020). On the brink of dissipation: The reactivation of narrative heritage and material craftsmanship through design research. In R. Almendra, & J. Ferreira (Eds.), Research & Education in Design: People & Processes & Products & Philosophy: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Education in Design (REDES 2019) (pp. 184–196), Lisbon, Portugal.

Banks, M., & Zeitlyn, D. (2015). Visual Methods in Social Research. SAGE Publications

Barthes, R. (1977). Image Music Text. Fontana Press.

Barthes, R. (2015). A câmara clara. Edições 70.

Barreto, S., Alvelos, H., Penedos-Santiago, E., Lima, C., Amado, P., Santos, R., Martins, N., & Pereira, J. (Ed.) (2021). Threads of a Legacy: Towards a pedagogical heritage in art and design: the Porto School of Fine Arts, 1956-1984. Porto: ID+ Instituto de Investigação em Design, Media e Cultura.

Bauret, Gabriel (1992/2018). A Fotografia. Edições 70.

Berger, John (2013). Understanding a Photograph. Penguin Books.

Cartier-Bresson, Henri (2006). Um silêncio interior: Os retratos de Henri Cartier-Bresson. Dinalivro

Cartier-Bresson, Henry (2015). O imaginário segundo a natureza. Gustavo Gili.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approach. Sage publications.

Hine, Lewis (1909/2013). A fotografia social. In A. Trachtenberg (org.), Ensaios sobre fotografia, de Niépce a Krauss (pp. 123–127). Orfeu Negro.

Lima, C., Barreto, S., Alvelos, H., & Penedos-Santiago, E. (2019b). Contributions of past generations in the current context of arts education. IAFOR - The European Conference on Arts & Humanities 2019: Official Conference Proceedings, 101. https://papers.iafor.org/submission51522/

Lima, C., Alvelos, H., Barreto, S., Penedos-Santiago, E., & Martins, N. (2020a). Learning Ecologies: From Past Generations to Current Higher Education. The IAFOR International Conference on Education – Hawaii 2020 Official Conference Proceedings. https://papers.iafor.org/submission53942/

Lima, C., Alvelos, H., Barreto, S., Penedos-Santiago, E., & Martins, N. (2020b). Traveling as a source of inspiration for artistic practice. Tsantsa. Revista de Investigaciones Artísticas, 8, 25–33. https://publicaciones.ucuenca.edu.ec/ojs/index.php/tsantsa/article/view/3077

Lima, C., Alvelos H., Barreto S., Penedos-Santiago E., & Martins N. (2021a). From Painting to Graphic Arts: The Unique Legacy of Armando Alves. In N. Martins, D. Brandão, & D. Raposo (Eds), Perspectives on Design and Digital Communication. Springer Series in Design and Innovation, vol 8. Springer, Cham. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49647-0_1

Lima, C., Alvelos H., Barreto S., Penedos-Santiago E., & Martins N. (2021b). The Rise of the First Design Course at the School of Fine Arts of Porto. In D. Raposo, J. Neves, J. Silva, L. Correia Castilho, & R. Dias (Eds), Advances in Design, Music and Arts. EIMAD 2020. Springer Series in Design and Innovation, vol 9. Springer, Cham. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55700-3_11

Lima, C., Alvelos, H., Barreto, S., Penedos-Santiago, E., & Martins, N. (2022a). The birth of graphic design in a school of fine arts: how the specificity of a learning environment determined a course’s vocation. In D. Raposo, J. Neves, & J. Silva (Eds), Perspectives on Design II. Springer Series in Design and Innovation, vol 16. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79879-6_4

Lima, C., Alvelos, H., Barreto, S., Penedos-Santiago, E., Santos, S. & Martins, N. (2022b). Case Studies of a Trans-Generational Pedagogy of Art and Design. The International Journal of Design in Society 16 (1), 113-129. https://doi:10.18848/2325-1328/CGP/v16i01/113-129

Lima, C., Alvelos, H, Barreto, S., & Santiago, E. (2019). O momento criativo: a mais-valia pedagógica de testemunhos biográficos de artistas portugueses. Tsantsa. Revista De Investigaciones Artísticas, 7, 43–51. https://publicaciones.ucuenca.edu.ec/ojs/index.php/tsantsa/article/view/2907

Lima, C., & Barreto, S. (2019). Caminhos cruzados de Armando Alves. Revista Gama, Estudos Artísticos 7(13), 108–117. http://gama.belasartes.ulisboa.pt/arquivo.htm

Lima, C., & Barreto, S. C. (2020). O designer escultor João Machado. Revista Gama, Estudos Artísticos. 8(16), 257–266.

Lima, C., Barreto, S., Alvelos, H., Penedos-Santiago, E., Martins, N., Santos, R., & Amado, P. (2020, maio). Pedagogical practices for the appropriation and activation of transgenerational knowledge in art and design. Paper presented at Asian Conference on Arts and Humanities (ACAH2020 11th), Tokyo. Abstract retrieved from https://issuu.com/iafor/docs/acah-programme-2020

Lima, C., Barreto, & Penedos-Santiago, E. (2021, outubro). Arquivos de imagens na recuperação e reativação de práticas artísticas e pedagógicas da Escola Superior de Belas Artes do Porto. Paper presented at I Congresso Internacional Fotocinema: Cultura, memoria y recuerdos visuales, Malaga, Espanha.

Marques, Susana Lourenço (2018). Ether/ Vale tudo menos tirar os olhos (1982-1994): Um laboratório de fotografia e história. Dafne Editora/Pierrot Le Fou.

Morgan, David L. (2008). Snowball Sampling. In L. M. Given (Eds.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (pp. 815–816). SAGE Publications

Pink, Sarah (2021). Doing Visual Ethnography. Sage Publications.

Penedos-Santiago, E., Martins, N. (2020). Curiosidade e inquietude: a ponte entre a ditadura e a liberdade na obra de João Nunes. Revista Estúdio, Artistas sobre outras Obras, 11(31), (pp. 62-70) . Lisbon, Portugal: Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa e Centro de Investigação e Estudos em Belas-Artes (FBAUL/CIEBA). http://estudio.belasartes.ulisboa.pt/E_v11_iss31.pdf

Quivy, R., & Campenhoudt, L. V. (2008). Manual de Investigação em Ciências Sociais. Gradiva.

Santiago, E., Alvelos, H., Barreto, S., & Lima, C. (2019). O Digital é de Ontem: Entrevista a Elvira Leite. Interact: Revista Online de Arte, Cultura e Tecnologia 30. https://interact.com.pt/30-31/o-digital-e-de-ontem-entrevista-a-elvira-leite/

Santos, R. (2020). The Visual Storytelling as a Way to Create Knowledge and Empathy Between Generations in Academic Institutions. The Barcelona Conference on Arts, Media & Culture 2020: Official Conference Proceedings. https://papers.iafor.org/proceedings/conference-proceedings-bamc2020/

Sontag, Susan (2012). Ensaios sobre fotografia. Lisboa: Quentzal Editores.

Sontag, Susan (2015). Olhando o sofrimento dos outros. Quentzal Editores.

Tinkler, Penny (2013). Using Photographs in Social and Historical Research. Sage Publications.

Weller, S. C., Vickers, B., Bernard, H. R., Blackburn, A. M., Borgatti, S., Gravlee, C. C., & Johnson, J. C. (2018). Open-ended Interview Questions and Saturation. PLoS ONE 13(6): e0198606. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198606

[1] Italics from the original version.

[2] This course was created in 1974, following the Revolution of 25 April, alongside the Product Design and the Communication Design courses at the School of Fine Arts in Lisbon (Escola Superior de Belas Artes de Lisboa).

[3] Traditional autumn festivities in Portugal with roasted chestnuts.

[4] João Dixo (1941-2012) graduated in Painting at ESBAP in 1967. His daughter Rute Dixo contributed with several images from her father's archive for this study.

[5] https://wisdomtransfer.fba.up.pt

[6] https://www.facebook.com/wisdomtransfer