Abstract: The 50th year of Picasso’s death affords an opportunity to look again at his approach to art. My article reconsiders his Suite Vollard (1930-37), a series of 100 prints that are habitually described as somehow at odds with modernism, as representative of a legitimately ‘naturalistic’ or ‘traditional style’, and having almost nothing to do with his earlier ‘mode(s)’ of working. As demonstrated, however, the shifting, fragmented and equivocating nature of his print portfolio indicates a far more hybrid form of creativity. It is akin, for example, to the hybridizations of the artist’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and his collages and papiers collés c. 1912. As such, I resist the tendency to view Picasso’s print series through the rather monocular lens of a definitively ‘classical’ or ‘neo-classical’ style’. In trying to unsettle and reframe the languages and constructs that have consistently plagued Picasso’s Suite, I suggest that its 100 plates are part of a wider stratagem to undo the commonplace occurrences that have always defined the histories of art.

Keywords: Classicism; Hybrid; Neoclassicism; Picasso; Suite Vollard.

Resumen: El 50º aniversario de la muerte de Picasso brinda la oportunidad de revisar su enfoque del arte. Mi artículo reconsidera su Suite Vollard (1930-37), una serie de 100 grabados que habitualmente se describen, de alguna manera, como no concordante con la modernidad, como representante de un estilo legítimamente 'naturalista' o 'tradicional', y que no tienen casi nada que ver con su(s) 'modo(s)' anterior(es) de trabajar. Está demostrado, sin embargo, que la naturaleza cambiante, fragmentada y equívoca de su carpeta de grabados indica una forma de creatividad mucho más híbrida. Es similar, por ejemplo, a las hibridaciones de Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) del artista y sus collages y papiers collés c. 1912. De este modo, me resisto a la tendencia a ver la serie de grabados de Picasso a través de la lente más bien monocular de un estilo definitivamente "clásico" o "neoclásico". Al tratar de desestabilizar y reformular los lenguajes y construcciones que han plagado constantemente la Suite de Picasso, sugiero que sus 100 láminas son parte de una estratagema más amplia para deshacer los lugares comunes que siempre han definido las historias del arte.

Palabras clave: Clasicismmo; Híbrido; Neoclasicismo; Picasso; Suite Vollard.

Cómo citar este artículo:

Finlay, J. (2023). Hybrid encounters: reframing Picasso’s Suite Vollard. Revista Eviterna, (14), 51-69 / https://doi.org/ 10.24310/re.14.2023.16737

1. Introduction[1]

Hybrid (hʌɪbrɪd)

a. produced by the union of two distinct species, varieties etc.; produced by cross-fertilization or interbreeding; mongrel; cross-bred; derived from incongruous sources.

n. a mongrel; an animal or plant produced by the union of two distinct species, varieties etc.; one of mixed nationality; a word compounded from different languages; anything composed of heterogeneous parts or elements

(The Concise English Dictionary, 1998)

Great mystery encompasses the commissioning and creation of Picasso’s most famous group of 100 etchings and engravings, the Suite Vollard of 1930-1937 (Coles Costello, 1979). Analysis of the Suite traditionally relies on Hans Bolliger’s rather conservative organisation of the plates at a time when it was put up for sale as a cohesive set in the 1950s, when he first orchestrated this body of work into twenty-seven assorted ‘introductory’ plates, and five loosely thematic ‘chapters’. Five plates are grouped as ‘The Battle of Love’, forty-six as the subject of ‘The Sculptor’s Studio’, four plates as ‘Rembrandt’, eleven classified as ‘Minotaure’, a further four as ‘The Blind Minotaur’ (Bollinger, 2007). Three portraits of Ambroise Vollard, executed in 1937, were later added. It was normal practice for print portfolios to be kept unbound so the Suite’s precise order and the exact events by which it came about remain in principal unknown[2].

In fact the work’s status as a suite was for some time called into question. Even though virtually half of Picasso’s plates have to do with the association between an artist and his creations and between an artist and his life models, the Suite altogether resists any particular reading or explanation. So, although Bolliger’s schema is a useful construction –to the point that scholars are now largely saddled with its classifications– it nonetheless has instigated endless confusion and debate concerning the Suite’s raison d’être.

2. Theoretical framework / objectives

In her book on the artist’s prints of the 1930s, Lisa Florman very forcefully challenged Bolliger’s schematic by contending that Picasso purposely left his Suite open-ended to permit an ongoing chain of associations between the various plates. Her argument is built on the premise that the prints’ ‘classicism’ is very much akin to the construction of ancient myth and that ‘mythological logic governs all of Picasso’s classicizing images.’ This analysis of all the 1930s prints, including the Suite Vollard, interprets it as a type of ‘counter-or anti-classicism’ (Florman, 2000, p. 206)[3]. As Florman argues, once Cubism became widely acknowledged as instigating a move toward flatness and abstraction, ‘Picasso expanded his repertoire to include images done in a ‘classicizing style and whose figures appeared to have the weight and palpable presence of sculpture’ (Florman, 2000, p. 22). The overriding art historical terminology used to describe Picasso’s group of 100 prints essentially involves the Suite taking on a supposed ‘antique cast’, ‘the style of the prints [being] resolutely classical’, and carried out in ‘a style at the furthest remove from modernism.’ Picasso’s Suite is also consistently identified as a type of artistic traditionalism, ‘with few of the prints contain[ing] more than a hint of Cubism or Surrealism’ (Florman, 2000, p. 5; Elliott, 2007, p. 54).

3. Research results

Habitually, this language and line of thinking is brought to bear when tackling Picasso’s notionally ‘classical’ paintings, drawings and prints. The term and construct of the ‘classical’ was up until relatively recently hardly ever challenged in Picasso literature, and in the light of his work being universally subsumed under the rubric of a new analysis of the First World War and its aftermath in France (Buchloh, 1981, pp. 19-68; Silver, 1989; Cowling and Mundy, 1990; Leighten, 1989, pp. 98-106).

This is perturbing given this type of terminology was a distinct anathema to Picasso. «From the beginning Picasso was always wary of aesthetic pronunciamento, always terse and epigrammatic», explains Dore Ashton in her anthology of his statements. Picasso’s comments could at times be deliberately contradictory, but on issues of ‘style’, ‘classification’ and ‘periodization’ in art, he was consistent in endeavouring to modify the status of such terms. As Ashton correspondingly discerns, «in the flow of life’s thought many of these statements would not appear as contraries». With proper context, –«who is asking [and] what are the specific circumstances» (Ashton, 1972, pp. 18-21)– Picasso’s statements are not a chronicle of his artistic ‘reality’, but adversely reflect the many fragmented, hybrid facets of his creativity. ‘Don’t talk to the driver’ was a preferred watchword when pressed for drawnout explanations of his work. His statements on art were always situated in direct opposition to notions of tradition and artistic progress. Likewise, he made every effort to deter approaches that would leave the huge scope and diversity of his creativity open to the yardstick of ‘style’.

Picasso’s sayings routinely reveal an abhorrence of academic of academic ‘canons of beauty’, ‘naturalism’, ‘style’, and historical continuity. As for ‘Cubism’, Picasso insisted that it was equivalent to any other discipline in painting, with similar rudiments and commonalities. He explained this to Marius de Zayas in an interview in 1923: «Drawing, design and color are understood and practised in Cubism in the spirit and manner that they are understood and practiced in all other schools [of painting]» (Ashton, 1972, p. 59).

It goes without saying that there is an enormous disparity here between the prescribed terms ‘Classical’ or ‘Cubist’ and Picasso’s own beliefs about art’s principles. When asked about the artistic fluctuations in his practice, he simply stated: «They are all the same images from different planes [of reality]». As for art requiring alternate modes and means of expression, Picasso reiterated that there were no ‘figurative’, ‘nonfigurative’, ‘abstract’, or «natural work[s] of art». And just to further his argument, neither were there any ‘concrete forms’ of art, but only ‘signs’.

If the subjects I have wanted to express have suggested different ways of expression I have never hesitated to adopt them […]. Whenever I have had something to say, I have said it in the manner in which I felt it ought to be said. Different motives inevitably require different methods of expression (Ashton, 1972, p. 5).

Picasso’s use of the word ‘manner’ is of some significance in relation to set terminologies such as ‘Cubism’ and ‘Classicism’, because it implies that seeing involves circumnavigating a whole host of aesthetic constructs, terminologies and unmitigated patterns of thought. The word ‘Cubism’, indeed, merely gives us something to cling to when looking at this difficult and varied art form, but the term is misrepresentative and throwaway to say the least (Cox, 2000, p. 11). The use of the ‘facet’ as a basic technical element in painting means the ‘cube’ of Cubism is not suitably of the essence, so we could just as well label it ‘Facet-ism’. It is commonly accepted that the provenance of the terms ‘Cubist’ and ‘Cubism’ originate from Matisse’s description of Georges Braque’s Houses at L’Estaque (1908)[4] as composed of ‘little cubes’. What artists saw as an expedient description for their work was thus construed factually by others. But the word ‘Cubism’ itself can never possibly do justice to the highly heterogeneous, inventive, animate, humorous and remarkable thing that is ‘Cubism’. It would be pointless to pick an alternate term regardless, so we are wedded to the ism suffix.

To treat historical works of art in this way is not unfamiliar. Unsurprisingly, the value and predominance of the term ‘Cubism’ was immediately challenged the minute it emerged. Jean Metzinger, in ‘Cubisme et tradition’ (Paris-Journal, 18 August 1911, p. 5), for instance, observed in the work of his fellow painters a fine balancing act between historical artistic traditions and modernist experimentation. «Because they use the [simplest …] and the most complete, and logical forms, they have been made out to be ‘cubists’», he objected. In fact, Picasso told the journalist Charles Cottet in late 1911 (Paris Journal, January 1, 1912) that «There is no Cubism» And as he expressed to Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler in 1913: «The news you’ve given me about the discussions of painting is sad indeed. As for me, I have received Apollinaire’s book on Cubism. I’m quite disappointed with all this chatter» (Antliff & Leighten, 2008, p. 123; Rubin, 1989, p. 416). By 1923, moreover, Picasso had become completely «impatient with the rhetoric that had attached itself to his cubist period and wished to stress that only in the work itself could the aesthetic be divined» (Ashton, 1972, p. 20). At any rate, as one scholar of Cubism has fittingly demonstrated, the artist’s pre-War ‘Cubist’ collage Head (1913)[5], and his painting of Woman in a Chemise Sitting in an Armchair (1913-1914)[6], could just as easily be understood ‘as Surrealist’, and André Breton too wrote of ‘that ridiculous word ‘cubism” in Surrealism and Painting (1928). Breton’s own understanding of Picasso’s ‘Cubist’ work in 1928 directly acknowledged the great grey ‘scaffoldings’ of 1912, the most perfect example of which is Man with Clarinet (1911-1912)[7], whose ‘parallel’ existence must remain a subject for endless meditation[8].

Thinking along these lines might seem like simple pigeonholing when it comes to historical works of art. But if we are to take seriously Picasso’s anti-historicist and antithetical approach to ‘isms’ and art, we must recognise that they apply equally to ‘Classicism’, ‘Cubism’ and ‘Surrealism’, or any other idiom for that matter. As John Berger argued in his watershed Ways of Seeing:

The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Yet when an image is presented as a work, the way people look at it is affected by a whole series of learnt assumptions about art. Assumptions concerning: Beauty // Truth // Genius // Civilization // Form // Status // Taste // […] The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe (1972, pp. 7-8, 11).

Berger’s book completely altered the way art historians think about art analysis, and scholars of modernism have similarly riffed on the difficult ‘communication between what sees and what is seen’, questioning the ‘structures of interpretation that have been developed subsequently in order to make sense of them.’ By directing attention away from Cubism and towards Surrealism, some have sought to disrupt ‘the terms of looking and thinking … [and] ‘bringing to the fore the construct that is our habitual … idea of Cubism.’ Correspondingly, I approach the problem by trying to unsettle and reframe the languages and constructs that have consistently beleaguered Picasso’s Suite, building on the work of those who have suggested that the relationship between seeing and knowing is never stable, and that this «negotiation is never simple […], but always structured or informed by our notions […] of previous interpretative language» (Eluard, 1944, p. 36; Ashton, 1972, p. 23; Cox, 2008, pp. 22-24). Fundamentally, I want to reiterate that all historical constructs have circumscribed limits when engaging with physical works of art, especially those by Picasso.

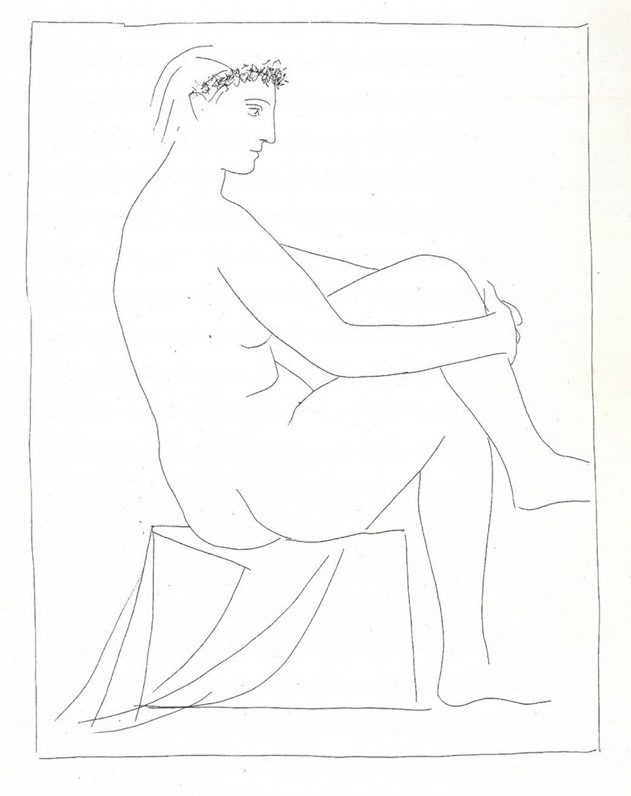

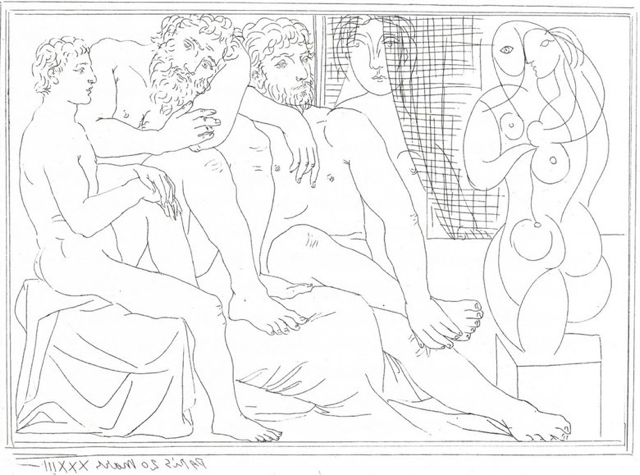

So even going along with the often-repeated notion of the Suite as primarily ‘classicizing’ or as rendered in ‘fairly traditional style’, what are we to make of the persistent oppositions and vacillations, changes, fluctuations and the paradoxical and incongruent characteristics punctuating the Suite? At glance, say, how do we account for the variations of a changed viewpoint of the lower body in Nude Woman Crowned with Flowers? [Fig. 1]. Simultaneously rendered in profile and three-quarters her twisted buttocks present a dual perspective that warps and disorders the architecture of the seat. And do we interpret the line forming the figure’s straightened arm as signifying the missing diagonal elements of the cubed seat? What, moreover, of the gaps or blank spaces used to avoid closed contours, allowing us to fill in the various visual possibilities? This concept of letting things in alternate planes bleed into one another and traditionally termed passage, was not only a key visual constituent of Paul Cézanne’s landscape paintings, but one used in Braque and Picasso’s early Cubist work, described by John Berger as ‘like a silence demanded so that you can hear the echoes’ (Berger, 1980, p. 55). The suppression of strong oblique lines and foreshortening in Nude Woman further creates a shallow relief space for things to nestle. It’s another device derived from Cubist experimentation: one that reinforces the paradoxical sense of sculptural fullness in two-dimensions. The autonomy of the outline as a visual component also helps to lay stress on simple cut out and ‘flat’ shapes arranged in simple semantic relationships. In this way, Nude Woman has echoes of the fragmentary and hybrid nature of collage and construction.

Fig. 1. Pablo Ruiz Picasso. Nude Woman Crowned with Flowers. Suite Vollard, 1. Boisgeloup, 16 September 1930 ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

Here, I want to point up this association not only because the notion of hybridity is in keeping with Picasso’s remarks on art but is likewise intrinsic to the makeup of his Suite. As a point of introductory analysis, we should acknowledge the various hybridisms –both figurative and abstract– that run through this large body of work. The term hybrid carries with it other associations, so it is important to establish a clear and systematic definition of the senses of hybridization, especially if we are to consider the process as an important [new] concept operating throughout Picasso’s Suite. Again, in Nude Woman, there is the sense of having put together the visual elements perceived piecemeal –Picasso’s fragmented aesthetic just one initial type of hybridity–. A second and most obvious sense involves human and animal crossfertilization, Minotaur appearing on 17 occasions alongside other hybrid couplings[9].

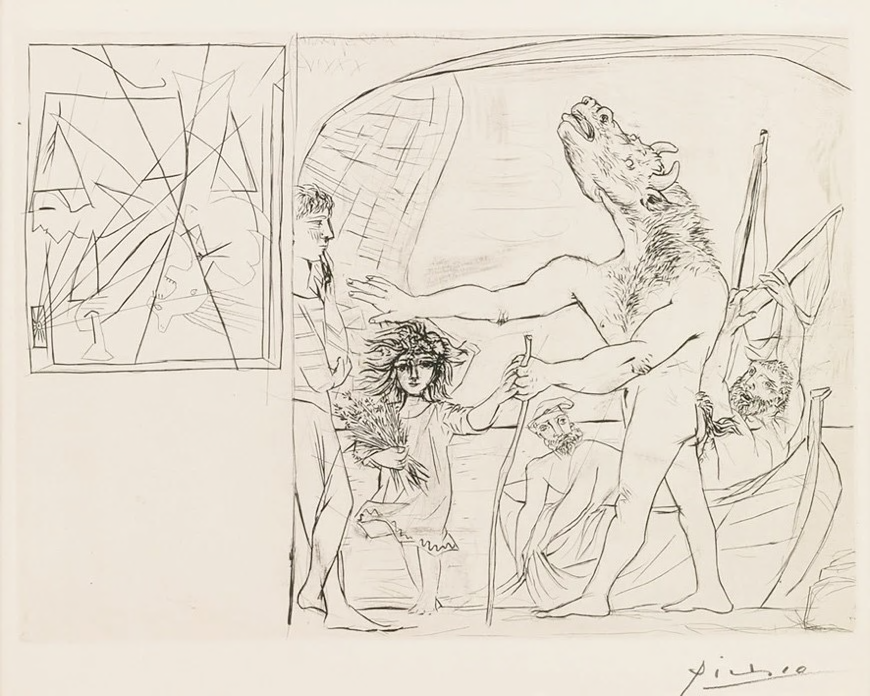

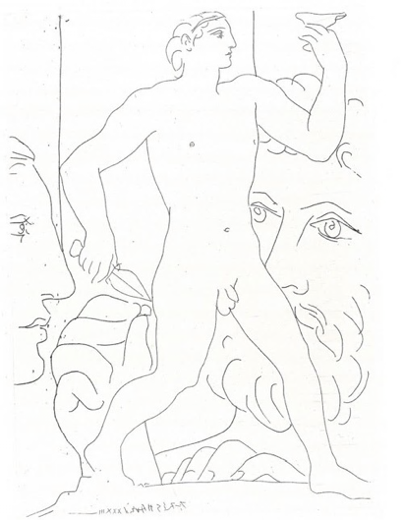

These include Minotaur Attacking an Amazon[10] and the other animalistic interbreeding in the ‘The Battle of Love’[11], the crossing or intersection of figures encouraging further hybridist associations. A less obvious [third] form of hybridization can be attributed to compound printmaking procedures that range from drypoint and burin engraving, etching, classic and sugar-lift acquatint –frequently applied together in a single print– as well as other unpremeditated techniques of an untried nature[12]. A variety of styles from meditative fine line drawings to erratically bitten tones across the plate surface[13] flaunt a fourth hybridism regarding the artist’s printmaking. In Blind Minotaur Led by a Little Girl in the Night (V.S: 97. 3-7 December 1934, or January 1 1935)[14], aquatint, worked with a scraper tool, resembles mezzotint, drypoint and burin engraving. In another plate with the same theme [Fig. 2] the plate juxtaposes an abstracted representation of the Death of Marat in the upper left section, but viewed upside-down and insistently cancelled with a large ‘X’.

Conjured from biomorphic body parts and everyday bric-a-brac, Model with Surrealist Sculpture (VS: 74) manufactures a comparably hybrid creature. Picasso’s Surrealist Sculpture not only embellishes the bricolage nature of his earlier construction and assemblage sculpture, but also pits supposed cultural impurities and syncretisms against idealised form[15]. In the sense of cross-breeding, a fifth hybridist form exists and carries with it unsettling associations of interbreeding, race, species, difference, as well as a variety of incongruous sources and different languages etc. A sixth hybridism worth mentioning is the Suite’s veritable assemblage of characters and motifs, drawn from the etchings of Rembrandt and Goya, Titian and Rubens’ paintings, ancient Greek Kylix pottery and Picasso’s own work. The oddly divorced treatment of its many plates’ two halves frequently stresses hybrid effects regarding the two and three-dimensional in art[16].

Fig. 2. Pablo Picasso. Blind Minotaur Led by a Little Girl in the Night. Suite Vollard, 94. Boisgeloup, 22 September 1934 ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

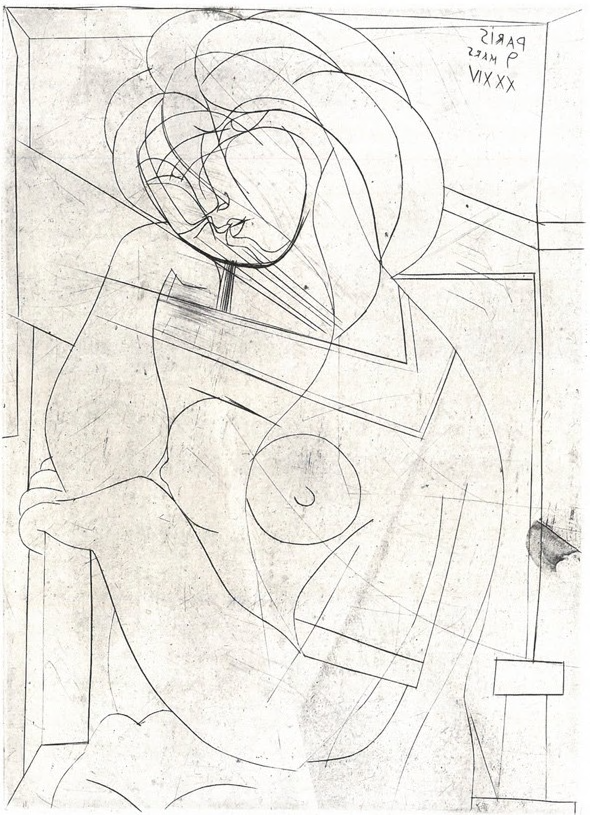

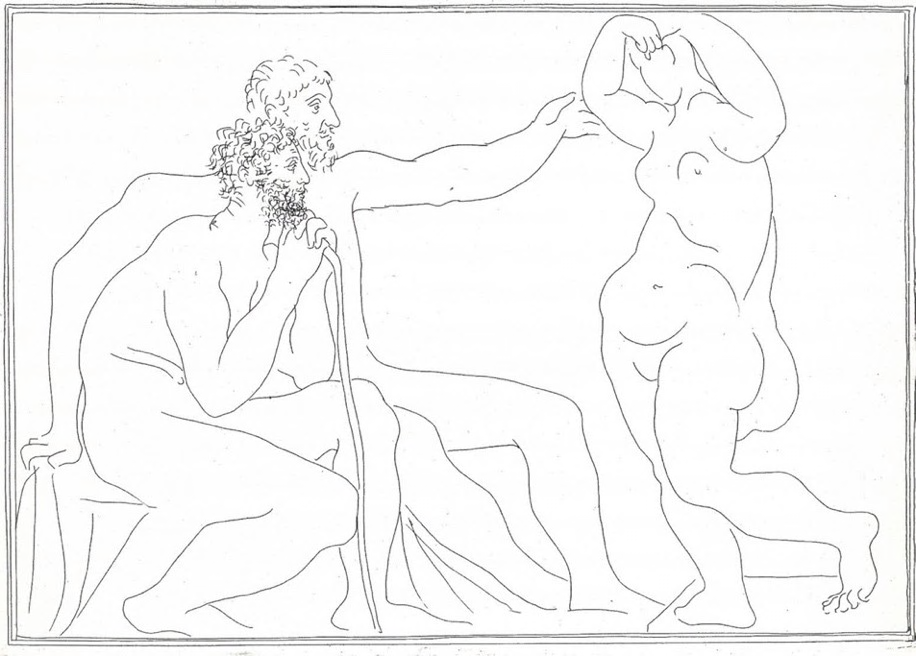

As a consequence, a string of hybrid associations is released across the Suite’s ‘cent estampes original.’ In Seated Nude with her Head Resting on her Hand[17] [Fig. 3], for instance, Picasso combines a feeling of smooth sculptural modelling with a sense of fragmentation and construction. To an extent, Seated Nude evokes the biomorphic and tumescent figures and countenances sculpted at Château de Boisgeloup in the spring of 1931, and of the type in Sculptor and Two Sculpted Heads[18]. The generalization of Picasso’s model’s tied-back hair-bun, the sleekness of her features and form, and right-hand resting meditatively in her head, hint at the tranquillity and self-containment often attributed to both Antique, Greco Roman statues and the French ‘neo-classical’ sculpture of Aristide Maillol (Cowling, 2002, p. 527). In contrast, hard-edged lines, angled and flat architectural forms that interpenetrate the figure’s curvaceous body, evoke the cubistic. Observe how her perfectly spherical left-breast is shifted to the front, while the other is viewed from the side, or how a section of architrave interpenetrates the woman’s neckline, her elbow and left-hand mingling with the armchair. Accordingly, the amalgamation of ‘modes’ recollect two famous pencil drawings, Portrait of Max Jacob (1915)[19] and Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, where Picasso’s self-styled ‘Ingrism(s)’ or ‘classical draughtsmanship’ sits uncomfortably alongside strange anatomical distortion and cubistic perspectival contrivance [Fig. 9]. Alternatively, the seated nude’s features are in particular redolent of the faceted and deeply ridged surfaces in famous Head (Fernande, 1909)[20], the fine lines making-up her face and hair recalling Picasso’s original statement and ‘intention of doing them in wire’ (Penrose, 1968, p. 19).

Fig. 3. Pablo Picasso. Seated Nude with her Head Resting on her Hand. Suite Vollard, 21. Paris, 9 March 1934 ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

At this juncture, we might want to temper our reading of Seated Nude from the perspective of supposedly pre-war ‘Cubist’, ‘neo-classical’, or ‘surrealistic’ forms of representation. Without wanting to disparage the persuasive method that has hitherto governed stylistic appraisals of the Suite, the use of undemanding categories, classifications and histories to describe Picasso’s 100 plates as ‘classical’, has limited critical usefulness regarding the visual analysis of his work. Concepts of ‘style’ and the great ‘classical’ tenets are in actual fact quashed by his pertinent sayings on art. «Down with style! […] Does God have a style? […] He made what doesn’t exist» (Malraux, 1994, p. 18). So did I’, Picasso remarked to André Malraux apropos this slippery concept in art history and connoisseurship. Ought we rule out his altogether sacrosanct statement? Perhaps not, because it was not said in isolation. At the Bateau-Lavoir at 2 a.m., and around the time of the creation of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)[21], the Spaniard loiters outside Max Jacob’s studio window, where the poet’s lamp is continually alight:

Picasso: Hey Max, what are you doing?

Jacob: I’m searching for a style.

Picasso (going off): There is no such thing (Parmelin, 1964, p. 135).

Picasso also expressed his out-and-out rejection regarding the language of academic classicism, something that he explained to Christian Zervos in 1935:

Academic painting is a sham […]. The Beauties of the Parthenon, Venuses, nymphs, Narcissuses, are so many lies. Art is not the application of a canon of beauty but what instinct and the brain can conceive beyond any canon. When we love a woman we don’t start measuring her limbs (Ashton, 1972, p. 11).

Again-and-again Picasso registered his artistic reasoning and informing Marius de Zayas:

The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered as an evolution, or as steps towards an unknown ideal of painting. All I have ever made was made for the present and with the hope that it will always remain in the present (Ashton, 1972, pp. 4-5).

Picasso’s rational confirms that antithetical forms in art were able to coexist, and he had in a way already achieved a similar type of visual incompatibility when he overpainted the faces and bodies of the right-hand figures of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a work from which stemmed many of the key devices of ‘Cubism’. Its huge inconsistencies in style and scale, improbably compressed, warping and solid spaces, and the representation of individual figures viewed from various angles, not to mention the contorted anatomies and primitivising masked faces, function to create a huge pictorial hybrid[22].

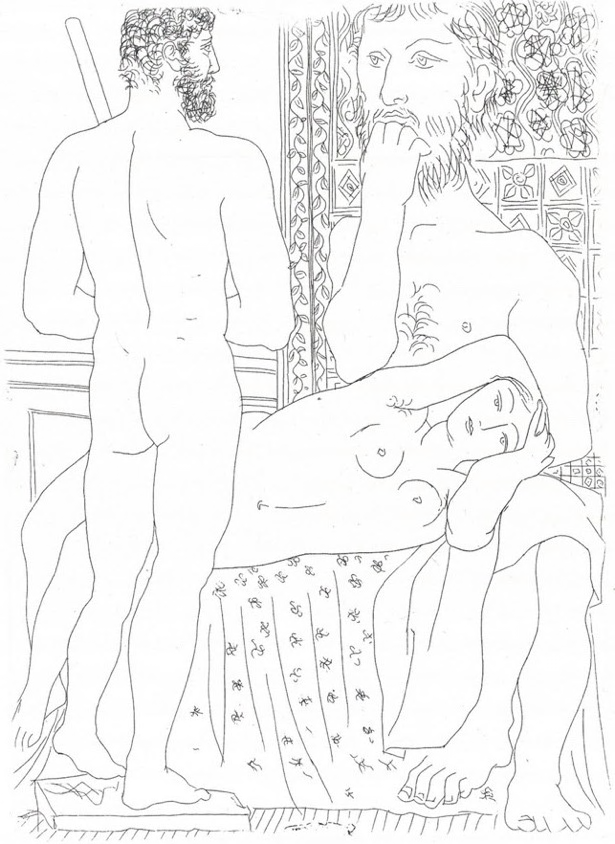

But this is not really my interest here. Rather it is the arrangement of the Suite’s many hybrid spaces and the contrasting scale and shape of its figures that continually draw the eye. In Sculptor, Reclining Model and Sculpture [Fig. 4], the structural squeeze makes the characters appear closer together in space, yet oddly, they do not seem similar in scale. A strange spatial and psychological relationship takes place between figure and spectator, the reclining model etched in such a way as to recall the flat shapes cut out and arranged in collage and construction sculpture. The effect adds to both the compositional compression and visual disruption mid-point in the arrangement. Meanwhile, a thoughtful-looking sculptor scrutinises from the distant background his standing sculpture, positioned to the left and turned away from us slightly. As such, we are encouraged to consider the adverse possibility that it is sculpture that is enamoured of, Pygmalion-like, either his creator or the model. It’s an arrangement that mirrors and ramps-up the compositions’ difficult vacillating relationships.

Similarly, in Sculptors, Models and Sculpture [Fig. 5], Reclining Sculptor in front of a Young Horseman[23] and Sculpture of a Young Man with a Goblet [Fig. 6], one’s perception shifts endlessly between choices as we negotiate the alternate pictorial strategies and are relentlessly called upon to adjust between various spaces, scales and perspectives. The to-and-fro of void and mass, plane and recession, shallowness and depth, horizontal and vertical and so on, bolsters a feeling of a notionally fluctuating harmony and antithesis in the plates. Most strikingly, it’s akin to the hybrid visual strategies of, for example, Picasso’s 1912 Violin[24]. As Rosalind Krauss has vividly demonstrated, the simple cut out papier collé elements operate like a palindrome, extracted from the same section of newsprint, but able to simultaneously suggest opposing terms (Krauss, 1992, pp. 261-286). An important visual lesson that can be derived from Picasso’s new ‘linguistic’ way of picturing, is that the significance of any constituent is innately variable, unstable and originates only from its place within a wider scope of signification. Essentially, Picasso’s visualising in earlier collage indicates something symbolically as opposed to being bound by traditional mimetic processes.

Fig. 4. Pablo Picasso. Sculptor, Reclining Model and Sculpture. Suite Vollard, 37. Paris, 17 March 1933

©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

Fig. 5. Pablo Picasso. Sculptors, Models and Sculpture. Suite Vollard, 41. Paris, 20 March 1933 ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

Fig. 6. Pablo Picasso. Sculpture of a Young Man with a Goblet. Suite Vollard, 70. Paris, 11 April 1933 ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

The effects of earlier ‘modes’ can be found throughout, including the plates Sculptors, Models and Sculpture[25] and Two Sculptors in Front of a Statue [Fig. 7]. Here the options offered by means of strange spatial and figurative arrangements proffer endless conundrums. For instance, what are we to make of the impossibly long arm of the sculptor sliding down the back of his companion in Two Sculptors, and to whom do we ascribe the many arms, legs and feet in this –and other– tightly bound figurative groupings, or make of their askew positionings, overlappings, foreshortenings and countless visual quandaries? In a way, the latter plate looks back to air-filled arms and legs ‘with as many twists as an intestine’ in the drawing Man at a Bar (1914)[26], where the «multiplicity of legs and arms enables the artist to indulge in pictorial counterpoint of utmost complexity, to play negative and positive space off against each other until the eye reels […and] a contrivance to which Picasso will have frequent recourse» (Richardson, 1996, pp. 410-411). With its small and featureless head, bulbous stomach and sagging buttocks thrown round to meet us, Picasso’s modern Venus in Two Sculptors seems to directly challenge the refined anatomical proportions and beautifying line of Ingres and other French nineteenth-century ‘neo-classical’ painters and sculptors. So Picasso’s plate is in total agreement with his belief that art is conceived ‘beyond any canon [of ideality].’

Fig. 7. Pablo Picasso. Two Sculptors in Front of a Statue. Suite Vollard, 7. Boisgeloup (?), 9 July 1931 ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

Akin to the ‘introductory’ plates, those of the ‘Sculptor’s Studio’ require us to fill in the void between contours and to use one’s imagination to transform the many silent passages into fleshy, solid formations. In the process, Picasso employs our creative participation in his Suite. Here the visual to-ing and fro-ing between angles and viewpoints, worlds and pictorial realities, and the strange reimaging of mode, scale, space, configuration and motif, has something of the antithetical nature of Les Demoiselles and later Cubism, where its purpose is to dethrone the cast-iron assurances of our visual certainty. The destabilizing and unruly character of Picasso’s Suite is entirely deliberate, its sense(s) of vacillation conjuring up deep feelings of uncertainty. Hence, like Cubist works, its plates never declare «that there is a correct place from which to see the world», and imply «a constant displacement of position [where] the world slips away from the image [and …] the viewer slips away from the world» (Cox, 2000, p. 129).

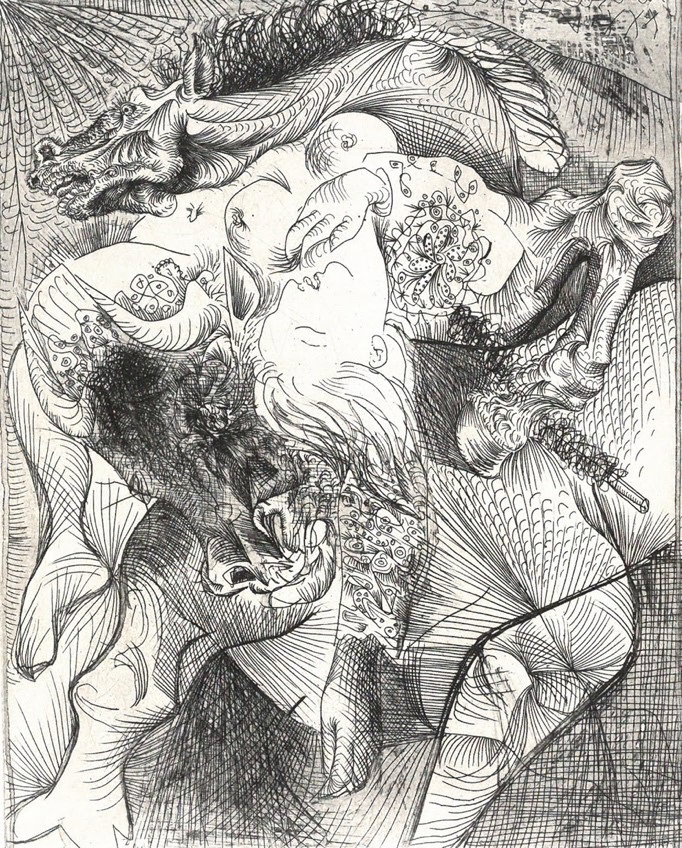

Undeniably,

Picasso’s concerns regarding Cubism in 1908-9 lay not in the language of

‘classical’ harmony and order in painting, but rather in ‘disrupting its

framework to the point of collapse’ (Reff, 1992, pp. 17-43)[27]. And we experience the

sensation of a hypothetically ceaseless point of collapse and counter-collapse

in Female

Bullfighter II [Fig. 8], the strange and indeterminate coupling

knitted into a dreamy air of shifting planes, where any sense of a stable,

unified image or space totally escapes us. Such is the difference here in

perspectives

–the figures simultaneously falling backwards and spilling out of the picture–

that the space between horse and bull snaps opens like a mechanical trap, a

pictorial device strongly evocative of Picasso’s Cottage and Trees (La Rue-des-Bois) (1908)[28].

This sense of vacillation is replicated in Picasso’s life-size Dryad (1908)[29] where, similar to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, «Our vision heaves in and out […] like the pitching of a boat in high seas, or a similitude of sexual energy» (Steinberg, 1988). In addition to this visual oscillation, there is a clear sense of evolving hybridity, the bullfighter’s right shoulder sprouting an equine appendage, her left leg doubling as a flagging arm, the protagonists repeatedly in the act of conjuring up new hybrids. As mentioned, Cubism is a handy term, albeit a preposterous one. However, if we see in Female Bullfighter II the ‘Cubist’, it is only one of many co-existent ‘manners’ and a case of the ‘surreal’ borrowed from the cubistic, or of Picasso ‘surrealising’ his Cubism.

Fig. 8. Pablo Picasso. Female Bullfighter II. Suite Vollard, 22. Paris, 20 June 1934 ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

This musing affords us the opportunity to consider briefly what the Suite‘s hybridity can tell us about Picasso in this particular moment –the shifting–, fragmented and disruptive character of his print portfolio indicating a creative élan way beyond the vagaries of ‘style’, categorization and artistic biography. By rejecting these aesthetic canons and linear narratives, Picasso sought an improved sense of his artistic life as a series of ‘moments’, ‘variations’ and ‘manners’ –all facets of a process that he endlessly re-cycled, re-worked and re-imagined–. Essentially, Picasso’s Suite should be seen as part of a greater interconnected whole with recurrent themes, symmetries and modes stretching over many decades. Moreover, this is a direct challenge to the biographical gambit in Picasso studies, where, alternatively, «the cycles, irruptions and repetitions of artistic vision formed the pattern by which Picasso perceived his life to be lived […] a way of living visually, and living in that element is chaotic, repetitive, fragmented, impulsive and so on» (Cox, 2018, p. 179)[30].

So assuming the hybrid and shifting nature of Picasso’s art, should we discard all categorization of his work in the main? This would be an obvious deduction. However, Picasso’s antipathy towards artistic constructs is best viewed as a tempering of notions with respect to ‘style’, periodization and art historical labelling, and a reinforcement of his belief that art was essentially all ‘the same images in different planes’. What’s more, Picasso’s persistent use of hybridization is bound up with his restless flow of inventiveness, one that allows for disruptive patterns of hyper-productivity to bleed into a larger creative venture. As such, Picasso’s 100 plates run parallel to a radical period of work in the early 1930s, most famously captured by his collage maquette illustrating the half-bull, half-human hybrid for the inaugural cover of Minotaure[31]. As scholars have shown in the context of this Surrealist-orientated periodical, Picasso’s correspondingly unstable and disruptive image of his work reveals that patterns of discontinuity, contradiction, interference and destabilisation are fundamental to his creativity (Cox, 2018; Cowling, 2002; Green, 2005; Florman, 2000). The jarring proximity of collage relays an obvious sense of hybridity, but equally there is a powerful feeling in Picasso’s Suite of a notionally limitless positioning and counter positioning, of things shifting in a continuous play of variation.

This idea brings us back to Lisa Florman’s contention that the seemingly chance development of the Suite is entirely intentional. As she perceptively argues, the multiplicity of its ‘interconnections’ is constantly «meant to scatter the terms and restart the game […] by confounding the suppositions upon which classicism’s very identity is based» (Florman, 2000, p. 93 and p. 205).. If her assessment that the plates ‘can continually be rearranged’ is accurate, and that juggling the prints about creates diverse or conflicting relations between them, its method is representative of shuffling playing cards, moving pieces on a chess board, or throwing dice in a game of chance. In this way, Picasso’s Suite is intimately associated with the ‘jouer’ of collage, particularly the playful overlapping and paradoxical surfaces in Still Life with Chair Caning (1912)[32], and more hybrid papiers collés –pasted papers– including Guitar, Sheet Music, and Wine Glass (1912)[33]. More analytically, collage and papiers collé correspond precisely to the portfolio’s uncanny pictorial language of interbreeding, where «the cross-fertilization of standard structures from one subject to another (head becomes bottle becomes violin)» (Cox, 2002, p. 287), constantly shifts, disturbs and defies classification.

This has major ramifications for any understanding of Picasso’s Suite, for it reiterates that heterodoxy, displacement, fragmentation, disorder, vacillation, recurrence and hybridity are part of an intentional strategy to uncouple the commonplace events that have always demarcated the histories of art. It is precisely this disorderly sense of artistic identity that goes against the Suite’s habitual likening to a ‘diary’, which rejects nebulous historical trajectories, stylistic classification and ‘isms’ with respect to Picasso’s wider oeuvre. Subsequently, the Suite continues a long established artistic pattern, one far more akin to the hybridizations of the 1907 Demoiselles d’Avignon and further hybrid inventions in collage, papier collé and construction sculpture. As Leo Steinberg has argued: «Collage was the first major outgrowth of Picasso’s intuition that discrepant modes of representation can cohabitate, like diverse fruit in a bowl. But the idea of combining un-reconciled elements in one presentation recurs continually in his art» (Steinberg, 1988, p. 61).

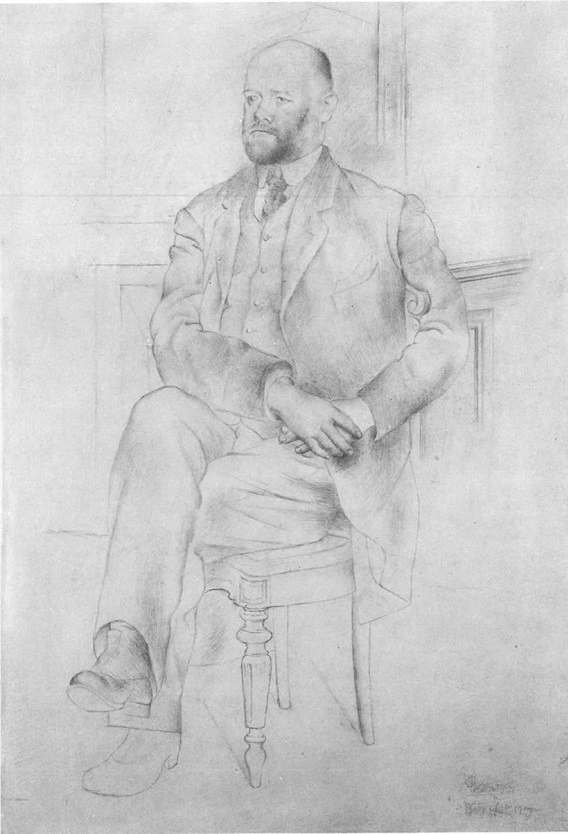

It is repeatedly argued that Cubism’s downfall coincided with Picasso’s various ‘neoclassical’ phases during the post-war rappel à l'ordre –call to order– orthodoxy within avant-garde circles, its further demise brought about by meticulous and ‘Ingres’-esque representation. But as Picasso explained to de Zayas, «Cubism is no different from any other school of painting. The same principles and the same elements are common to all» (Ashton, 1972, p. 59). As the Picasso historian Elizabeth Cowling has perceptively observed of the so-called ‘naturalistic’ Portrait of Ambroise Vollard [Fig. 9], its rigid linear construction often said to evoke the ‘genre Ingres’, has a structural and arbitrary relationship with «the devices of Cubism […] for despite its remarkable accuracy of detail, the drawing is no more ‘life-like’ than Cubist painting, and is just as obviously a construction gradually assembled by the artist on the blank sheet of paper» (Cowling, 1990, p. 206). Far from a straightforward ‘Ingrism’, the vertical and horizontal lines of the background bind the sitter into the surrounding architectural space, a feature not unlike the Suite’s Seated Nude[34]. In this way, the drawing’s iridescent grisaille tone not only evokes the Portrait of Vollard (1910)[35], but also the ‘scaffolding’ of Man with a Clarinet, which Breton claimed belonged equally to Cubism and Surrealism.

Fig. 9. Pablo Picasso. Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1915, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

Other formal anomalies that remind us of the Suite include Vollard’s head seemingly too small for his body, the dealer’s left shoulder and torso impossibly exaggerated, his arms and legs disproportionate and stunted: abnormalities, as we saw, that feature throughout the ‘The Sculptor’s Studio’ plates. Note the attention paid to the jacket sleeve in the pencil drawing, Picasso slyly swapping the transparency, openness or hollowness of the cuff depicted in his 1910 painting for something far more solid-looking[36]. Not only does the floor unnaturally fall away beneath the sitter, but also the shadows formed by the chair’s legs clearly signify –in mock deference to Vollard’s taste perhaps– the cube or facet of Cubism. As Cowling additionally remarks of the Vollard graphite: «The lighting in the drawing also has an arbitrary character which produces a rhythmically dispersed pattern of tone, as does the lighting in analytical Cubist paintings» (Cowling, 1990, p. 206). The final results of the Vollard portrait reveal an obvious lopsidedness to his physique and highlight the out-of-joint aspect of the chair and the surrounding architecture of the room. The drawing completed five years after the Vollard painting essentially underscores the abstracted and structural principles between the two ‘manners’. As Picasso mentioned to the Swedish journalist Arvid Fougstedt, who saw the drawing during a visit to the artist’s studio in 1916 and characterised the graphite work as ‘an Ingres’[37]: «People say I have abandoned Cubism to make this sort of thing; that is not true, you can confirm it yourself» (Seckel, 1994, p. 125)[38]. Likely, Picasso was referring not just to his contemporary work, which swung increasingly between ‘Cubism’ and said ‘naturalistic styles’, but that he sought to underwrite the basic relationships that co-existed in all art.

4. Conclusions

Of course, accounts of Picasso’s Suite all have something to offer us. Yet nearly each and every one neglects to underscore his explanation for the co-existence of the ‘manners’ –‘post cubist’ and ‘neoclassical’ in this case– as identical images in altered planes of reality. Consequently, as Jean-Claude Lebensztejn relatedly identifies,

In Picasso’s work, there is no beginning, and above all, no end, to cubism. It simply unfolds across time, in temporal facets that are labelled ‘periods’…. Cubism is just a word – indeed a ludicrous one. But if that’s what it means to be a cubist, Picasso remained cubist throughout his artistic life (Lebensztejn, 2018, p. 53).

In rejecting «the scholarly compartmentalization of his oeuvre – Blue period followed by Rose period followed by Cubism, first Analytic, then Synthetic, and so forth» (Fraquelli, 2010, p. 90), one can justifiably maintain that there are no ‘Classical’, ‘Cubist’ or ‘Surrealist’ modes of art, but «only forms which are more or less convincing lies» (Ashton, 1972, p. 4). As Picasso warned us: «We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand». In other words, what we see is affected by what we know or what we believe. This idea is entirely in keeping with Picasso’s thinking and his integral aesthetic concept of hybrid encounters.

5. Bibliographic references

Antliff, M. and Leighten, P. (eds.) (2008). A Cubism Reader, 1906-1914. The University of Chicago Press.

Ashton, D. (1972). Picasso on Art: A Selection of Views. Da Capo Press.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. The BBC and Penguin Books Ltd.

Berger, J. (1980). The Success and Failure of Picasso. Writers and Readers Publishing Co-operative [1965], 1980.

Bolliger, H. (2007). Picasso’s Vollard Suite. Thames and Hudson [1956].

Breton, A. (1972). Surrealism and Painting (1928). Trans. Simon Watson Taylor. Harper & Row.

Buchloh, B. (1981). Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression. October, 16.

Clarke, J. A. & McCully, M. (2017). Picasso Encounters. Clarke Institute. Yale University Press.

Coles Costello, A. (1979). Picasso’s Vollard Suite. MIT Press. Ann Arbor. UMI Research Press.

Coppel, S. (2012). Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite. The British Museum.

Cottet, C. (1 January 1912). Paris Journal.

Cottington, D. (1998). Cubism. Tate Gallery Publishing.

Cowling, E. (2002). Picasso: Style and Meaning. Phaidon Press.

Cowling, E. (2016). Picasso Portraits. National Portrait Gallery Publications.

Cowling, E. (March 1985). Proudly we claim him as one of us: Breton, Picasso and the Surrealist Movement. Art History, vol. 8, no. 1.

Cowling, E. & Mundy, J. (eds.) (1990). On Classic Ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism, 1910-1930. Tate Gallery.

Cox, N. (2000). Cubism. Phaidon Press.

Cox. N. (2018). Picasso in his Element? An Autumn of Surrealism. In Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy, Archim Borchardt-Hume and Nancy Ireson (eds.). Tate Publishing.

Cox, N. (2008). Picasso’s ‘Toys for Adults’: Cubism as Surrealism. The Gordon Watson Lecture. National Galleries of Scotland in association with The University of Edinburgh & VARIE.

Elliott, P. (2007). Picasso on Paper. National Galleries of Scotland.

FitzGerald, M. (1996). The Modernists Dilemma: Neoclassicism and the Portrait of Olga Khokhlova. In Rubin, W. (ed.). Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation. The Museum of Modern Art. Thames and Hudson.

Florman, L. (2000). Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930s. MIT Press.

Fraquelli, S. (2010). Picasso’s Retrospective at the Galeries Georges Petit, Paris 1932: A Response to Matisse. In Bezzola, T. (ed.). Picasso: His First Museum Exhibition 1932. exh. cat. Kunsthaus Zurich, Munich.

Green, C. (2005). Picasso: Architecture and Vertigo. Yale University Press.

Kenneth E. Silver, K. E. (1989). Esprit de Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War, 1914-1925. Princeton University Press.

Krauss, R. (1992). Motivation of the Sign. In Rubin, W. and Zelevansky, L. (eds.). Picasso and Braque: A Symposium. Harry N. Abrams.

Lebensztejn, J.-C. (2018). Periods: Cubism in Its Day. In Cubist Picasso. Réunion de Musées Nationaux and Flammarion.

Leighten, P. (1989). Re-Ordering the Universe: Picasso and Anarchism, 1897-1914. Princeton University Press.

Malraux, A. (1994). La Tête d’obsidienne. Gallimard [1974]. Picasso’s Mask. Trans. June Guicharnaud with Jacques Guicharnaud. Da Capo Press.

Metzinger, J. (18 August 1911). Cubisme et tradition. Paris-Journal.

Parmelin, H. (1964). Picasso: Women. Trans. Humphrey Hare, Harry N. Abrams, 1964.

Penrose, R. (1968). The Sculpture of Picasso. MoMA.

Reff, T. (1992). The Reaction against Fauvism: The Case of Braque. In In Rubin, W. and Zelevansky, L. (eds.). Picasso and Braque: A Symposium. Harry N. Abrams.

Richardson, J. (with the collaboration of McCully, M) (1996). A Life of Picasso: volume II, 1907-1917. Random House.

Rosenblum, R. (1960). Cubism and Twentieth-Century Art. Harry N. Abrams.

Rubin, W. (1989). Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. MoMA.

Seckel, H. (1994). Max Jacob and Picasso. Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux.

Steinberg, L. (Spring 1988). The Philosophical Brothel. October, Vol. 44.

Tinterow, G. and Stein, S.A. (eds.) (2010). Picasso in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yale University Press.