Resumen: Marina Picasso escribió con respecto a la relación de su abuelo con sus compañeras que «las embrujaba, las digiría, y las plasmaba en sus lienzos» (Picasso, 2001, p. 180). Lo que no tomó en cuenta es el hecho que aquellas mujeres jugaron un papel vital en el proceso creativo del artista, a menudo estimulando grandes cambios en su carrera. Aunque no aprobamos de ninguna manera su comportamiento hacia el sexo opuesto, este artículo se concentra en el impacto crucial que una de sus primeras compañeras, Fernande Olivier, tuvo en su obra mientras Picasso avanzaba hacia el Cubismo. El estilo del artista fue cambiando al inicio de su convivencia con ella en el Bateau-Lavoir, consolidando el conocido Período Rosa. La influencia transformadora de Fernande continuará por algún tiempo, alcanzando puntos críticos durante dos viajes que hicieron juntos a España. Como se sabe, el joven Picasso regresaba a su país de origen cuando se disponía a hacer importantes cambios en su estilo. Éste fue el caso definitivamente durante estas dos visitas a Gósol en 1906 y Horta en 1909. La primera condujo al desarrollo del llamado Periodo Ibérico en el que se centró progresivamente en el uso de máscaras, aplicándolas en un principio al rostro de Fernande. Ella será igualmente un componente esencial durante la segunda estancia en España, cuando Picasso desarrolla en Cubismo Geométrico. Aquí de nuevo, el artista projectó los nuevos descubrimientos en se compañera, intentando integrar pintura y escultura en sus lienzos a través de los rasgos de ella.

Palabras clave: Fernande, Periodo Rosa, Ibérico, Cubismo

Cómo citar este artículo:

Mallen, E. (2023). Fernande Olivier and Pablo Picasso's Advance Towards Cubism. Revista Eviterna, (14), 146-160 / https://doi.org/10.24310/re.14.2023.16641

1. Introduction.

Hearing that a Montmartre studio would become available as Paco Durrio was planning to abandon the Bateau-Lavoir at 13, rue Ravignan –now Place Emile Goudeau– for a larger space in the Maquis, Pablo Picasso and Sebastià Junyer-Vidal took off for Paris on April 12, 1904 (Palau, 1980, p. 370; Unger, 2018, p. 148; Bouvier, 2019, p. 132). Pablo had hoped that Montmartre could serve as his permanent Parisian base (Palau, 1980, p. 371; Richardson, 1991, p. 293)[1]. The Butte had become a haven for bohemian artists, the landlord decided to split the warehouse-sized spaces into smaller units. Because of the neighborhood’s notoriety, rents were low, and those units soon found occupants. In the early nineties tenants included a number of anarchists. It then became a nest of Symbolists. Gauguin, for instance, had been a frequent visitor (1893–1895) after his return from his first stay in Tahiti (Richardson, 1991, p. 296). One sign of his determination to settle there was that he brought along his dog Gat, given to him a few months earlier by Utrillo (Unger, 2018, p. 152). They were only able to move into the Bateau-Lavoir around mid-June (Mahler, 2015, p. 38)[2]. To the locals, the ramshackle building made mostly of wood, zinc, and dirty glass, with stove-pipes sticking up at haphazard was known as the Maison du Trappeur, apparently because its decrepit appearance conformed to their notion of a log cabin in backwoods Alaska.

Picasso may have already spotted Fernande Olivier (1881–1966) coming in and out of the Bateau-Lavoir by the time he saw her at Coco’s, the color merchant on boulevard Clichy (McCully, 1997, p. 43; McCully, 2011, p. 134). She had a mass of reddish hair, and green, almond-shaped eyes (Richardson, 1991, p. 310). The beautiful, tall girl seemed languid, aloof, more voluptuous than the girls Pablo was accustomed to, with strong, vivid features and a contrasting aura of lightness. Born Amélie Lang, she was also known as Fernande Belvallé. She had already been married when she arrived in Paris, running away from her husband, Paul Émile Percheron, who had been abusive and violent (Brocard, 2022, pp. 40–43). By spring of 1900, she could bear it no longer, and fled the house early one morning and caught the first train to Paris, where Laurent Dubienne, an aspiring sculptor living in the place Ravignan, discovered her as she waited outside the employment agency. His actual name might have been Gaston de la Baume. He installed her in his studio at the Bateau-Lavoir and launched her on a career as a model. She would boast of having posed for Cormon, Carolus Duran, Boldini, Henner, Rochegrosse and very briefly –if at all–, Degas (Richardson, 1991, p. 310; Roe, 2015, p. 89). Fernande called those quarters an «intimate» environment. She commented that one could hear everything from one room to another: the creaking mattress, punctuated by passionate groans, songs, cries, the sound of steps. The space between the wooden boards left no one in ignorance of the comings and goings of the neighbors. The doors barely closed (Franck, 2001, pp. 54-55). She had already noticed the malagueño, as she jotted in her journal: «There is a Spanish painter. I keep coming across him, looking at me with big, heavy eyes. I couldn’t say how old he is—his mouth is a nice shape, but he has a deep line from his nose to his mouth, which ages him» (Roe, 2015, pp. 82-83). She thought him a little coarse, but there was something une personnalité émouvante which somehow shone through. Since she lived in the same building, it is no wonder that she often saw him. «Why does he spend all his time on the Place Ravignan?,» she remembered thinking. «Whenever does he work?» Later she learned that he preferred painting at night, so as not to be disturbed (Richardson, 1991, p. 309).

One day, Picasso came face to face with her (Palau, 1980, p. 383; Richardson, 1991, p. 304; Daix, 1992, p. 32; Riedel, 2011, p. 77; Read, 2011, p. 161; Unger, 2018, pp. 168, 193).[3] She wrote that the meeting took place as she was returning to the Bateau-Lavoir:

Yesterday afternoon the atmosphere was really oppressive before the storm. The sky was black, and when the clouds suddenly broke we had to rush for shelter. The Spanish painter had a little kitten in his arms which he held out to me, laughing and preventing me from going past. I laughed with him. He seemed to give off a radiance, an inner fire, and I couldn’t resist his magnetism (Olivier, 2001, p. 139).

He invited her into his studio, and she accepted, although she did not see anything particularly attractive about him at first—rien de très seduisant. As for his outfit, it left quite a lot to be desired. At this time he usually wore the French workingman’s blue cotton jacket with the red Catalan sash, the faixa, under it (O’Brian, 1994, p. 126). She seemed to be more impressed by his work space:

This was my introduction into the world in which I was to live for so long; the world I came to know, love and respect. I was astonished by Picasso’s work. Astonished and fascinated. The morbid side of it certainly perturbed me somewhat, but it delighted me too … Everything there suggested work: but, my God, what chaos! … Easels, canvases of every size and tubes of paint were scattered all over the floor with brushes, oil containers and a bowl for etching fluid (Olivier, 1965, 46)

2. Theoretical framework/objectives.

The theoretical framework is primarily empirical. We review multiple biographical records, that, although they concur for the most part, show certain deviations that prove to be relevant. The objective is to illustrate, through selective artworks, how Picasso’s style changed as he started living with Fernande Olivier, leading to the well-known Rose Period. Her transformative influence would continue and reach high points during their stay together in Gósol and Horta. The first trip underpinned the development of the Iberian period in which Picasso focused on the use of masks, applying them first to portraits of Fernande. Their stay in Horta led to Geometrical Cubism. Here again he projected his discovery onto his companion, as he attempted to merge painting and sculpture in his canvases.

3. Research results.

3.1. First representations of Fernande Olivier.

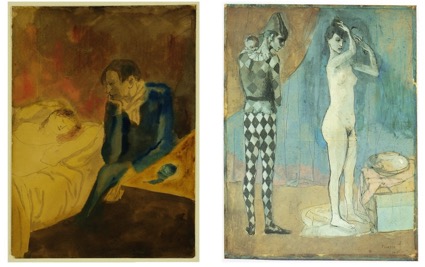

By late autumn, 1904, Fernande started to feature frequently in his work brightening its tonalities; the artist himself often appeared as the observer, as in the watercolors Le nu endormi (Meditation) [Fig. 1a][4], where a beautiful woman with great almond eyes, sleepily sensual, lays at ease with no clothes on. Olivier was remarkably idle. She would lie in bed for hours while he worked. Here he rests his chin on his hand and gazes forward into open space as he «meditates» about their future. Blue tones dominate his half of the picture, a blue that even spills from his tea-cup; the woman, by contrast, is bathed in a golden light with a rosy haze floating above her (O’Brian, 1994, pp. 129, 135). We are confronted with two opposing worlds in a static relationship, with his gaze as a key element. Concentrated thought is juxtaposed to the fragile figure of a sleeper absorbed in her dreams (Varnedoe, 1996, pp. 111-175). Impressive and elegant as she was, he was proud to be seen with her in public. To the penniless little émigré, she was the perfect sex object, without the least inhibition or hang-up. They soon adopted an almost bourgeois routine: no more Spaniards dropping in at odd hours, no more drinking bouts, no more whorehouses (Cabanne, 1979, p. 94). When she spent the night at his studio, he devoured her with his eyes. When she awoke, he would be standing at her bedside, entranced. He begged her to come and live with him. She hesitated, afraid of his jealousy. But when he brought her gifts, she melted. He didn’t have a cent, but still managed to get her books and the perfumes she loved, strong and intoxicating (Franck, 2001, p. 57).

Fig. 1: The early representations. 1a: Le nu endormi (Meditation) [OPP.04:016]. Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York. 1b: La famille d’arlequin [OPP.05:075]. Particular Collection ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

Although the characters in his works presented themselves still as distant, living in a world of their own, they had a serenity and peace about them which seems to reflect the new sense of belonging that Pablo had finally found in his love of la belle Fernande. The pale emaciated forms of famished cripples had been replaced by shapely adolescent figures full of the grace and proud of their physical dexterity (Penrose, 1981, pp. 110-111). Whenever they could afford it, the group went to the circus. Ever since his adolescent affair with Rosita del Oro, this had been his favorite form of entertainment, after the bullring. Moreover, the Cirque Médrano –only a few blocks away from the Bateau-Lavoir– had just launched a major new attraction: the great clown Grock (Carmean, 1980, p. 39; Richardson, 1991, p. 369; Riedel, 2011, p. 77; Roe, 2015, p. 119). Picasso would later recall:

I was really under the spell of the circus. I liked the clowns best of all ... Did you know that it was here at the Médrano that clowns first began to abandon their classic costumes and dress in a more burlesque fashion? It was a real revelation. They could invent their own outfits, their own characters, do anything they fancied (Brassaï, 1966, p. 20)

He made friends with the jugglers and saltimbanques who camped with their families in small spaces set beside the large tents in which they performed under the warm glare of paraffin lamps. Parents with their children, and their trained monkeys, goats and other animals, squatted among the props they used in their acts. Detached from the busy life of the big city, they lived absorbed in rehearsing, proud to show their acquired agility (Penrose, 1981, pp. 110-111).

The acrobat family in works like La famille d’arlequin [Fig. 1b][5] are once again characterized by a thin and slender constitution, a prerequisite of their physical trade, and by a melancholy brought on by their precarious existence. The male figure wears the usual two-cornered hat and checkered costume of the Harlequin; as in other cases, he is depicted as an admiring observer as he looks at his female companion with a gentle and worried facial expression. In Famille d’arlequin,[6] Picasso introduced an air of warmth and family closeness. He again placed them in a warmer indoor setting rather than in a bare, expansive landscape as he had done before. This work differs from the previous one in that the main character plays a even more active role, kissing and caressing the child, while in the other he was more of a passive bystander, temporarily holding the child while the mother is at her toilette. A sense of tenderness and intimacy is amplified by the close interaction of all three members and was probably inspired by the new circumstances in Pablo’s own life, namely his relationship with Fernande, and a newfound domestic happiness. As Cabanne notes, in works like this, «the firmness and authority of blue monochrome gave way to a sort of a multicolored fragility» (Cabanne, 1979, p. 97).

Fernande dated her definitive move into Picasso’s studio at the Bateau-Lavoir on the same day the statue of the Chevalier de la Barre was inaugurated on the Butte. That is September 3, 1905 (Richardson, 1991, p. 314; Daix, 1992, p. 37; Roe, 2015, p. 114; Bouvier, 2019, p. 166)[7]. «Everything seems beautiful, bright and good,» she wrote after one nightlong session. «It’s probably thanks to opium that I’ve discovered the true meaning of the word ‘love,’ love in general. I’ve discovered that at last I understand Pablo, I sense him better. It seems as if I have been waiting all my twenty-three years for him» (Olivier, 1965, p. 156). She jotted in her journal: «With one leap you were outside lugging my trunk ... with another leap you were back home, where you shut me and the trunk up with you while your arms enclosed me» (Richardson, 2015, p. 314). She describes the changes that she saw from one year to the next:

The paintings he’s doing are quite different from those I saw when I first came to the studio last summer, and he’s painting over many of those canvases. The blue figures, reminiscent of El Greco, that I loved so much have been covered with delicate, sensitive paintings of acrobats (Olivier, 2001, p. 162).

The studio was a furnace in summer, and it was not unusual for him to receive visitors half-naked, if not totally so; with just a scarf tied round the waist (Richardson, 1991, 310).

It was already well into autumn when he completed La famille de saltimbanques (Les bateleurs)[8]. The unity of the composition lies in the overall poetic atmosphere rather than in the legible details. A general feeling of restraint is accentuated by the fact that the two figures closest to the viewer are seen from the back. While capturing the marginal existence of the bohemia he still inhabited, the painter realized that he could accomplish his goal of executing a major masterpiece without necessarily including narrative action (FitzGerald, 2017, 155). No matter how closely he tied the different characters together on the surface of the canvas, their interrelationships remained mostly enigmatic (McCully, 1992, 54). Carmean pointed out that the picture appears as «a montage of numerous juxtaposed elements, each individually conceived in its own pictorial space» (Cowling, 2002, 118–131). This brought about a change from the narrative to the symbolic, and from a solidified structure to one where self-sufficient units interact (Carmean, 1980, 50). By leaving everything so open-ended, Picasso evoked an environment that the spectator accepts as magical or poetic, intended to mask, rather than reveal, reality.

3.2. The stay in Gósol in 1906 and the Iberian period

Fernande had been living with Picasso for seven months when he decided to take her to Spain. The opportunity came as Vollard visited him on May 6, 1906, and purchased twenty-seven canvases for a total of 2,000 francs, amounting to twice the annual wage of a laborer. This was a staggering price for the then little known twenty-five-year-old Pablo. It eased his financial burden for the near future (Blier, 2019, pp. 20–21). By May 11, he had gotten the money from Vollard (Rabinow, 2006, p. 107; Baldassari, 2007, p. 334), and with the cash in his pocket, he started making specific plans for the trip home. He would take Fernande first to Barcelona to introduce her to his parents. Then he would look for a quieter place to work. He had heard of Gósol, an isolated village in Upper Catalonia five thousand feet up in the Pyrenees, near the little country of Andorra, through Enric Casanovas, who divided his time between Barcelona and Paris and sometimes spent the summer there. He might have also heard about it from his old friend Jacint Reventós, who used to send his patients to the town to convalesce: «good air, good water, good milk and good meat». In any case, all the arrangements for the trip were made by Casanovas (Richardson, 1991, p. 434; Palau, 1992, p. 76; Daix, 2007, p. 12; McCully, 2011, p. 196; Unger, 2018, p. 276; Bouvier, 2019, p. 212). Such an isolated place could bring about the changes he desired in his work. Surrounded by the bare landscapes and the rustic population, he could refine his style, seeking what Gauguin had found in Tahiti or Pont-Aven: a form of purity, an unpolluted primitivism like the one he had discovered in the Iberian sculptures in the Louvre (Rosenblum, 1996, p. 268; Franck, 2001, p. 88).

Pablo arrived in Gósol in style. With the freshly received 2,000 francs from Vollard in his pocket and accompanied by his stylish girlfriend, la belle Fernande, he was the talk of the town, miles away from the buzzing cosmopolitan metropolis of Barcelona or Paris. They got two rooms at the only inn there was, Cal Tampanada, the house with the sloping roof (Richardson, 1991, p. 438; Unger, 2018, p. 277). As soon as they felt settled, he started to sketch, his imagination set ablaze by the wealth of stimuli he found in this Catalonian haven. During the course of this ten-week Spanish sojourn, he would produce as much work as he had in the previous six months in Paris: seventeen oils, twenty-one gouaches, two boxwood sculptures, and a bas-relief, fourteen watercolors, and 170 drawings –in pencil or ink–, as well as sketches made in another notebook (Richardson, 1991, p. 441; Jaques Pi, 2019, pp. 228-229). «The atmosphere of his own country was essential to him» Fernande recalled of their trip, «and gave him … special inspiration» (Richardson, 1991, pp. 435-436).

The intimate presence of his lover succeeded in transforming Pablo’s life and art. Driving away the angular female and the slender androgyne of earlier periods, she catalyzed a new sensual image with broader hips, fuller breasts, almond-shaped eyes under the delicate and pure double arc of the brows, and a voluptuous mouth drawn in perfect symmetry (Daix, 1965, p. 51). Indeed, her face and figure which now featured prominently in his work, became a field of artistic experimentation. Her sturdy, voluptuous form, and her particular mix of indolence, vanity and languorous sexuality, suited the mood, which was sensual, reassuring, exuding well-being and the promise of plenty. His search for a new formal vocabulary, resting on archaic roots, also bore the mark of Orientalism, that was already prevalent in some of sources like Ingres’s Le bain turc (Bouvier, 2019, p. 230). Indeed, though modeled on his companion, the usual pose of these nudes –arms raised above their head in a gesture that is both self-absorbed and inviting– goes as far back as ancient depictions of Aphrodite (Unger, 2018, pp. 280–281). The woman in profile holding the mirror in the oil discussed above might have escaped from a Greek vase with her straight nose, draped robe and mass of curly hair (Vallentin, 1963, p. 75). Fernande in fact inspired a wide range of art historical paraphrases, paintings and drawings that recreate her in an inventory of guises culled from antiquity through the nineteenth century. In a full-length standing nude whose sculptural presence is belied by the most nuanced fragility of line and hue, she becomes a new version of the Venus de’ Medici, except that «the postural modesty of the classical prototype, who covers her breast with one hand and her sex with the other, is subtly undermined by the unexpected union of this figure’s coupled hands directly over her groin» (Rosenblum, 1996, p. 266).

Fernande had lived with Picasso for almost a year and had known him for twice that long, but it was only at Gósol that her presence really made itself felt in his work. The great diversity of the work done there is seen in a very evident way through the treatment given to her features. In Tête de Fernande[9], Picasso softened her strong neck and full face by accentuating the sultry pout of her lips and her fixed eyes. Rather than portraying his companion frontally, he posed her in three-quarter profile, with the result that her averted gaze encourages the viewer to look directly at the model without reservation. As Palau has noted, the head is given such an earthy quality that it is almost as though it were itself a lump of earth, as if we were dealing with a transubstantiation between woman and landscape (Palau, 1980, p. 455). The many drawings and paintings that he did of Fernande reveal that having her so close and focusing on her as a model helped him develop his approach to this new representation of the body. The pink and reddish palette he used to depict her, mostly nude, began to infiltrate every aspect of the surrounding space and the objects in it (McCully, 2011, p. 198). Her physical features became an area of artistic experimentation. The search for a new formal language rooted in archaic antecedents manifests itself in the largely classical treatment in Nu aux mains jointes.[10] The large-format canvas represents a full body nude in three-quarter profile, whose almond eyes identify her as Fernande. She is standing on brownish soil slightly echoed in the color of her hair. Her slender amber body with sloped shoulders and large square head projects from a very vivid rose background. The uniformity in the colored areas makes the relief appear flat, but despite the large planes underlined by strokes of brown, the rigorous treatment of the composition makes it akin to wood carving, in Valletin’s view (Vallentin, 1963, p. 71). The portrait likeness is diminished in the interest of simplifying the forms: la belle Fernande has become an archetype, her face an expressionless mask, as Bouvier argued (Bouvier, 2019, p. 232). With her monumental body and masklike face, the picture reaffirms his transition to artistic Primitivism (Bouvier, 2019, p. 212). At the same time, the search for the representation of measurable volume, the wish to paint three-dimensionally, was to produce a series of truly sculptural pictures towards the end of the summer (Daix, 1965, pp. 51–53). Progressively, the body proportions became thick-set, the heads shorter and more square, the eyes vacant. The color turned uniformly rose verging on brick-red, with only the woman’s features delineated in brown (Vallentin, 1963, p. 71).

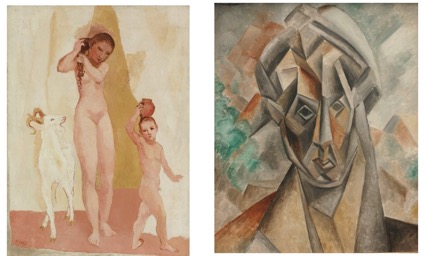

In Le harem[11], he made a recapitulation of his many studies of Fernande. In one of of those depictions of her, La jeune fille à la chèvre [Fig. 2a][12], he placed the nude girl doing her hair at the center. On her left a putto holds a small pot on his head; on her right a frisky white goat looks up at her. The composition might have been drawing on Ingres’s La Source, or his dancer in the background of Le bain turc (Richardson, 1991, p. 447). To develop expressive force, he used distortions, divergences from appearance already practiced by the master (Daix, 1993, pp. 59-60), distilling the abundant presence of female nudes in the original work to four, each of whom offers a variation on his infinite repertory of sensual and languorous poses of nudes as they tend to their toilette (Rosenblum, 1996, pp. 263-266). It signals Picasso’s never-ending infatuation with that painting, freshly topical, thanks to its inclusion in the recent Ingres retrospective at the Salon d’Automne. The artist recreated not only its theme and figural postures but, more subtly, its precariously arranged corner view of an enclosed space confined to sensual delights. Compared with the Frenchman’s fleshy beauties, however, the Spaniard’s girls seem insubstantial, in danger of dissolving into thin air (Richardson, 1991, p. 447). Fascinated by his companion, Picasso had depicted four naked Fernandes in an intimate setting, combing her hair, washing, looking at herself in a mirror and lying down (Daix, 2007, p. 13). The presence of a clothed procuress crouching in the corner transforms the harem into a bordello. Given the artist’s versatility at projecting himself into his own fictional characters, it is tempting to read the anatomically undersexed male giant who contemplates the scene while he grabs his phallic porrón as a self-portrait. It is important to note that the sensuality of the painting is not limited to its subject matter. The artist treated the surface of the canvas with the tenderness of a potter kneading clay using a palette of warm ochres, terracottas, and cool slate (Unger, 2018, p. 281).

3.3. The stay in Horta in 1909 and Geometrical Cubism

Picasso would return to Spain with Fernande in 1909. On the eve of their departure, Vollard had come up once again with the necessary funds, paying him 2,200 francs –in early May, 1909– (Rabinow, 2006, p. 111). With that cash in his pocket, he took off for Barcelona with Fernande on May 11 (Richardson, 1996, p. 123)[13]. After a while they moved on to Horta, where he had stayed back in 1898. Fernande wrote to Toklas on June 5: «we are on our way to the country» (Richardson, 1996, 124). They stopped to rest at an inn in Tortosa, before continuing the following day (Roe, 2015, 263)[14]. Apollinaire provided a picturesque depiction of what she probably saw during the trip: «And then there is the land. A cave in a forest where one felt like leaping about; a passage on mule-back at the edge of a chasm; and the arrival in a village where everything reeked of warm oil and rancid wine» (Baldassari, 2007, p. 123). He also acknowledged Pablo’s intoxication as he immersed in the rural landscape in search for a more primordial, sensual nature. The house where they lodged belonged to Tobias Membrado, the town’s baker. They had the oven where they made the bread, the store where they sold it, and their living quarters all in the same house. The place was located in the Plaza de la Iglesia, by the Hostal del Trompet, opposite the Town Hall. Pablo and Fernande only stayed there a few days, moving immediately to the hostel, the real name of which apparently was Posada Antonio Altés (Cabanne, 1979, 130; Richardson, 1996, 126). Nevertheless, he would continue to use the attic in Membrado’s place as a studio.

Fig. 2: The two stays in Spain. 2a: La jeune fille à la chèvre [OPP.06:019]. Barnes Foundation Collection. 2b: Tête de femme sur fond de montagnes [OPP.09:022]. Particular Collection ©️ Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2023

During the ensuing months, Picasso abandoned the former starkly dramatic chiaroscuro, turning instead to an increasing use of faceting that was no longer dependent on conventional shading, and he proceeded to orchestrate the surface of his paintings by means of a purely intuitive alternation of flat surfaces. The rugged scenery that the artist saw everywhere around him appeared to have encouraged him to introduce even more extensive planar structure in both his landscape and figure compositions (Penrose, 1981, pp. 151-152). The specific variety of Cubism developed in Horta resulted from a fusion of Cézanne’s principle founded on the deconstructive interplay of reserves (blanks) and his own version of photographic hyperrealism (Baldassari, 2007, p. 120). Early during his stay, he had taken several pictures of the Santa Barbara Mountain, named after a Christian martyr who became entrenched in folk culture throughout Europe in the early Middle Ages. Eventually, he would come to associate her namesake mountain with Fernande’s kidney afflictions (Baldassari, 2007, p. 135).

As the sequence of Santa Barbara-Fernandes progressed, Picasso would switch back and forth between long shots and close-ups. Cowling remarks:

within the series as a whole there were mini-series devoted to the head only, the head and shoulders, and the head and torso or three-quarter-length figure … Further variation is introduced through the angle of the head, orientation of the figure, degree of contrapposto in the pose, the hairstyle and clothing, lighting, color and the extent to which the background and its content are subject to the same elaborate faceting (Cowling, 2002, pp. 211-212).

He bifurcated and crenellated her forehead like the ridges of resistant rock; he merged the faceted head/mountain with the faceted sky. As a result, sky, mountain and woman cohere into a single organism. He managed to penetrate beneath the skin, not because of any special interest in anatomical technicalities, but because he wanted to reconcile not just back and front but inside and out (Richardson, 1996, pp. 132-133). It is not that he had abandoned nature, but instead he had tried to harness it to portraiture. Given the association of the mountain with the torture of Santa Barbara, one could say he depicted Fernande’s suffering in terms of the crags in the terrain.

Abandonment of perspective involved the problem of integrating the human figure in space. The background in Femme assise[15] was brought forward until it was on a level with the model in the foreground. Henceforth the human body was built up of geometric planes fitting one into another and almost imperceptibly separated by a border, its relation with space defined by a different coloring and shadowed outlines (Vallentin, 1963, p. 85). Picasso’s working methods had changed: rather than working up sketches and studies toward a single composition that would include some of his latest developments, he produced a series of oils (all ostensibly based on Fernande), whose primary concern was the radical reinterpretation of pictorial form. As Golding has commented:

Picasso had become interested in a sculptural approach to painting because of the physicality of his vision, because he wanted to touch and to mold and to handle his subjects … With the adoption of multi-viewpoint perspective Picasso presented the viewer with a sculptural fullness or completeness on a two-dimensional support (Cowling & Golding, 1994, p. 20).

Sculptural quality is also powerfully present in paintings like Tête de femme sur fond de montagnes [Fig. 2b],[16] particularly in the dramatic rendering of the figure’s elongated neck, the pronounced eyebrows and the reversible cube of her forehead –which can be read as both protruding and receding– and whose V-shape was echoed in her characteristic upturned lips. While these canvases consistently take her image as their motif, Picasso’s attention was centered on representation itself, rather than depicting a specific model. Daix has observed:

painting itself now reigned supreme, blossoming with renewed vitality beyond all inherited assumptions as to its limits, subject only to the geometricizing demands of his refiner’s fire … The portrait is no longer a naturalistic representation but has become everything that painting can appropriate from the model in order to transform it into what only painting can express (Daix, 1996, p. 276).

By the end of his stay in Horta, the artist had evolved in his figure paintings a recognizably advanced state of Cubism, all crags and crevices –the figure of woman as a mountainous landscape, as it were– much like the rugged terrain of the Terra Alta itself. Picasso’s deconstruction of Fernande’s visage would subsequently turn complexly baroque, as he sub-divided planes into smaller and more numerous facets. His paintings for the first time displayed an overall and consistent planar structure. Weiss has noted how these paintings «sustain an impression of manifest weight and depth despite the growing ambiguity of projecting and receding planes […] an increasingly dispersed yet gravity-stricken density of form» (Weiss, 2003, p. 13). The rules of construction, the treatment of colors and composition that had been implemented since the Renaissance were pulverized, leaving the field open to a non-representational, expositional language.

4. Conclusions

Women played an important role in the evolution of Picasso's artistic expression. This is particularly evident in Fernande Olivier’s case as they lived together starting in 1905 bringing about the consolidation of the Rose Period. This would continue as he moved through two other major styles in his earlier career: the Iberian Period and Geometrical Cubism. In both cases, her physical features became an area of artistic experimentation as the search for a new formal language, rooted in archaic antecedents, manifested itself largely in the artist's treatment of his companion's features during their stay both in Gósol in 1906 and Horta in 1909.

5. Bibliographic references

Baldassari, A., E. Cowling, C. Laugier and I. Monod-Fontaine (2002). Chronology. En A. Baldassari et al. (Eds.). Matisse Picasso (pp. 361-390). Tate Publishing.

Baldassari, A., ed. (2007). Cubist Picasso. Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Flammarion.

Blier, S. (2019). Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. Duke University Press Books.

Boeck, W. and J. Sabartés (1955). Picasso. Abrams.

Bouvier, R., ed. (2019). The Early Picasso: Blue and Rose Periods. Riehen / Basel.

Brassaï (aka G. Halász) (1966). Picasso and Company. Doubleday.

Brocard, Y. (2022). Le fils secret de Fernande. En N. Bondil and S. Ooms (Eds.). Fernande Olivier et Pablo Picasso : Dans l'intimité du Bateau-Lavoir (pp. 40-43). In Fine éditions d'art.

Cabanne, P. (1979). Pablo Picasso: His Life and Times. William Morrow and Co.

Carmean, E., Jr. (1980). Picasso, The Saltimbanques. The National Gallery of Art.

Christie’s. (2009). Impressionist and Modern Evening Sale. Auction catalogue 2164, May 6.

Cowling, E. (2002). Picasso: Style and Meaning. Phaidon.

Cowling, E. & J. Golding, eds. (1994). Picasso, Sculptor/Painter. Tate Gallery.

Daemgen, A. (2005). Picasso. Ein Leben. En A. Schneider and A. Daemgen (Eds.). Pablo. Der private Picasso: Le Musée Picasso à Berlin (pp. 14-44). Prestel.

Daix, P. (1965). Picasso. Preager.

Daix, P. (1993). Picasso: Life And Art. Basic Books.

Daix, P. (1996). Portraiture in Picasso’s Primitivism and Cubism. En W. Rubin, et al. (Ed.s). Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation (pp. 255–295). The Museum of Modern Art.

Daix, P. (2007). Pablo Picasso. Tallandier.

Franck, D. (2001). Bohemian Paris: Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, and the Birth of Modern Art. Grove Press.

Gärtner, J. (2011). Im ‘Zentrallabor der Malerei: ’ Das Leben am Montmartre. En T. Kellein and D. Riedel (Eds.) Picasso: 1905 in Paris (pp. 10–35). Hirmer Verlag GmbH.

Golding, J. (1968). Cubism: A History and an Analysis 1907–1914. Harper and Row.

Jaques Pi, J. (2019). The Stay at Gósol. En R. Bouvier (Ed.) The Early Picasso: Blue and Rose Periods (pp. 228–229). Riehen / Basel.

Mahler, L. (2015). Selected Exhibitions, 1910–1967. En A. Temkin and A. Umland (Eds.). Picasso Sculpture (pp. 304-311). The Museum of Modern Art of New York.

Mallen, E. 2023. Online Picasso Project (OPP). Sam Houston State University. http://picasso.shsu.edu.

McCully, M., ed. (1997). Picasso: The Early Years 1892–1906. Yale University Press.

McCully, M. (2011). Picasso’s Discovery of Paris. En M. McCully et al. (Eds.) Picasso in Paris 1900–1907: Eating Fire (pp. 15-34). Mercatorfonds.

Milde, B., ed. (2002). Biografie. En I. Mössinger, B. Ritter and K. Drechsel (Eds.). Picasso et les femmes / Picasso und die Frauen (pp. 396-403). DuMont.

O’Brian, P. (1994). Pablo Picasso. A Biography. W.W. Norton and Company.

Olivier, F. (1965). Picasso and His Friends. Appleton-Century.

Olivier, F. (2001). Loving Picasso: The Private Journal of Fernande Olivier. Harry N. Abrams.

Palau i Fabre, J. (1992). The Gold of Gósol. En M. Ocaña et al. (Eds.) Picasso, 1905–1906. De l’època rosa als ocres de Gósol. (pp. 75-88). Electa.

Penrose, R. (1981). Picasso: His Life and Work. University of California Press.

Picasso, M. (2001). Picasso: My Grandfather. Riverhead Books.

Rabinow, R., et al. (2006). Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard Patron of the Avant-Garde. Yale University Press.

Read, P. (2011). All Fields of Knowledge. En M. McCully et al. (Eds.). Picasso in Paris 1900–1907: Eating Fire (155–176). Mercatorfonds.

Richardson, J. (1991). A Life of Picasso. Volume I: The Prodigy, 1881–1906. Random House.

Richardson, J. (1996). A Life of Picasso. Volume II: The Painter of Modern Life, 1907 1917. Random House.

Riedel, D. (2011). ‘... da war ich Maler! ’ Die Ankunft in Paris. En T. Kellein and D. Riedel (Eds.). Picasso: 1905 in Paris (pp. 64–111). Hirmer Verlag GmbH.

Roe, S. (2015). In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris 1900–1910. Penguin Press.

Rosenblum, R. (1996). Picasso in Gósol: the Calm Before the Storm. En M. McCully et al. (Eds.). Picasso: The Early Years, 1892–1906 (pp. 263-276). The National Gallery of Art.

Sotheby’s. (2007). Impressionist and Modern Art (Evening Sale). Auction catalogue N08314, May 8. New York.

Sotheby’s. (2016). Impressionist & Modern Art (Evening Sale). Auction catalogue L16006, June 21. London.

Sotheby’s. (2018). Impressionist and Modern Art (Evening Sale). Auction catalogue N09860, May 14. New York.

Unger, M. (2018). Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World. Simon and Schuster.

Vallentin, A. (1963). Picasso. Doubleday and Co.

Weiss, J., V. Fletcher and K. Tuma. 2003. Picasso: The Cubist Portraits of Fernande Olivier. Princeton University Press.