European Journal of Family Business (2020) 10, 82-91

The Total Compensation Model in Family Business

as a Key Tool for Success

Santiago Almadana-Abona*, Jesus Molina-Gomezb, Pere Mercade-Melec,

Jaime Delgado-Centenoa

aUniversidad de Málaga / Departamento de Economía y Administración de Empresas. Plaza del Ejido s/n - 29071 Málaga. España

bUniversidad de Málaga / Departamento de Estadística. Plaza del Ejido s/n - 29071 Málaga. España

Received 2019-10-03; accepted 2020-10-01

JEL CLASSIFICATION M52

KEYWORDSTotal compensation, Family business, Human resources management, Organisational behaviour, Strategic management

CÓDIGOS JEL M52

PALABRAS CLAVE Compensación total, Empresa Familiar, Gestión de recursos humanos, Comportamiento organizacional, Gestión estratégica

Abstract The purpose of this research study is to examine the importance of the total compensation model in family business as an essential element for human resources management, in line with the organisation’s strategic management, in order to optimise organisational behaviour. This is based on the useful and efficient use of different compensation tools and methods, taking into consideration both the differences and common aspects of family businesses with regard to other type of companies, as well as their size.

El modelo de compensación total en la empresa familiar como herramienta clave para el éxito

Resumen El objetivo de esta investigación es examinar la importancia del modelo de compensación total en la empresa familiar como elemento esencial para la gestión de los recursos humanos, en línea con la gestión estratégica de la organización, para optimizar el comportamiento organizacional. Esto se basa en el uso útil y eficiente de diferentes herramientas y métodos de compensación, teniendo en cuenta tanto las diferencias y aspectos comunes de la empresa familiar con respecto a otro tipo de empresas, como su tamaño.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i2.6811

Copyright and Licences: European Journal of Family Business (ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X) is an Open Access research e-journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial.

Except where otherwise noted, contents publish on this research e-journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

*Corresponding author

E-mail: santiago.almadana@uma.es

1. Introduction

A company’s success depends on its ability to maintain stability while managing change with regard to internal and external pressures. Although all organisations have some difficulties to adapt to changing conditions, family businesses present specific and unique issues and problems (Beckhard & Dyer Jr., 1983).

Studying the problematic differences that affect family businesses is becoming more and more relevant in the management field (Sánchez Carrasco & Madera, 2010). This is a consequence of the significant importance of family business’s activity on the economy of developed countries (Gallo et al., 2004).

The interdependence between ownership and management in these companies creates strengths that tend to make executive and strategic decisions more complex and subjective (Beckhard & Dyer Jr, 1983). One of the main challenges that family businesses often have to face relates to worries regarding human resources (Heneman et al., 2000; McCann et al., 2001).

Various authors highlight that one of the main aspects to consider when designing a family business nowadays is the compensation system (Cardon & Stevens, 2004; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2003; Rutherford et al., 2003). Likewise, a key factor is the total compensation system, which consists of both a financial and non-financial extrinsic rewards and an intrinsic reward (Delgado-Planas 2004; Saqib et al., 2015). This system constitutes a normal practice in the business dynamic and is an invaluable management tool, since it can be used to attract, keep, motivate and satisfy workers (World at Work, 2000).

People and organisations should not be understood as repaired entities. Their interaction produces joint behaviour, known as organisational behaviour, which introduces the study of the activities which are being carried out by people in an organisation and the implications on the performance of the business itself (Robbins, 1992).

It is assumed that each person presents a unique condition, an idiosyncrasy that influences the need to generate and analyse a contingency structure of organisational behaviour on the basis of the use of situational variables that moderate cause-effect relationships (Robbins, 1992).

This diverse and conditional essence is also directly influenced by the organisation’s nature, from which it is ultimately deduced that the compensation strategies are different, as is the case of all organisations (Murlis, 1996).

From a strategic perspective, family businesses build their mission, prioritising the family link itself. Firstly, because in order to maintain interest and business involvement they must feel a family purpose, and the second reason is the need for a sense of cohesion and pride that will make people want to overcome problems (Ward, 2016). Likewise, compensation practices must be aligned with both the business objectives and employees’ values (Brown, 2001), so that the sense of family proves to be the context through which the strategy should be understood.

Therefore, human resources management in family businesses is a complex task in an environment in which the relationships between owners, managers, employees and family are not clearly defined in terms of authority and responsibilities (Leon-Guerrero et al., 1998; Reid & Adams, 2001).

The adoption of formal compensation practices in family businesses could be important in at least two ways (Anneleen, 2017). Firstly, the compensation system may be an important communication device to encourage business activities and highlight the legitimacy to external parties involved (Cardon & Stevens, 2004; Graham et al., 2002). Secondly, family businesses are recently beginning to recognise the benefits that the implementation of formal human resources management practices may bring (Sheehan, 2014), given that the implementation of best human resources management practices generally leads to an improvement in business performance (Carlson et al., 2006; Sheehan, 2014). Thus, adopting more formal compensation practices could be a sign of professionalisation, and, therefore, making the business more attractive to possible applicants.

On the other hand, the introduction of formalised compensation practices may also have disadvantages for family businesses. For example, the high cost associated with these practices for businesses with limited resources; it could limit the possibility of employees negotiating with regard to their salary and benefits, which could consequently lower their motivation (Marlow & Patton, 2002). Moreover, formalising compensation could undercut the advantages of having an informal business culture.

If a deductive method is assumed, it is revealed that one of the essential aspects of the compensation strategy is the application of a compensation policy, which is presented as a set of principles and guidelines reflecting the business’ orientation and philosophy regarding workers’ remuneration (Chiavenato, 1993).

Accordingly, the need of a specific study on total compensation in family businesses is apparent. This study aims to respond to a series of questions: What are the differences in the various compensation policies between family businesses and other types of businesses? How does the size of a business influence on this difference? How do the employees of family businesses value financial and non-financial elements?

The criteria to be considered are:

- Human resources professionals in family businesses are familiarised with the functions of human resources management, specifically with the total compensation model.

- With the alignment existing between human resources management and strategic management in family businesses, compensation, in general terms, is fundamental not only for the human resources strategy, but also for the organisation as a whole.

2. Theoretical Framework: Total Compensation

Over time, the study of family businesses has proven to be an increasingly valued topic (Catry & Buff, 1996), since it always appears to be linked to some specific dynamics that require qualitative and quantitative analysis separate from other possible business paradigms.

Strategic planning in family businesses is different from planning in other types of businesses, mainly because family problems must be included in the planning (Ward, 1988).

In the family business model a situation with three main components arises: ownership, management and family, the latter representing the unique part of its nature and becoming in many cases the fundamental pillar on which the business dynamic is driven (Walsh, 2011).

The interaction of these three component results in both unique challenges and opportunities. The benefits deriving from belonging to a family business vary depending on its size and state of evolution. Likewise, this aspect provides an interesting perspective to consider when developing human resources strategies for the construction of the appropriate structures shaping each family business, lastly being reflected in the total compensation system (Walsh, 2011).

In the study of the people’s behaviour in organisations, there is a relationship which feedbacks from the interaction of both parties. This study raises unique questions under the family environment spectrum. It is based on pillars that differ from other types of companies, insofar as the dynamics of this sector directly and indirectly influence organisational behaviour, more specifically, in the direction of three fundamental discrepancies that completely separate family businesses in the scope of organisational behaviour: the control of capital by the family, their participation in business management and the intimate link between family and business (Catry & Bluff, 1996).

This model is understood as a fusion of two systems or institutions, with the family system being deeply emotional and the business system being based on labour. Both systems overlap and may become independent, since they are often opposites, with dissimilar objectives and priorities (Steckerl, 2011).

Generally, empirical evidence highlights that human resources practices in family businesses are significantly less professional than those in non-family businesses. In terms of agency, these less formal and professional human resources practices are explained by the high alignment of principal-agent interests and the altruism of those linked to family businesses (Chua et al., 2009; Schulze et al., 2001).

Some studies found that family businesses have less probabilities of adopting formal human resources management practices than their non-family counterparts (Astrachan & Kolenko, 1994; de Kok et al., 2006; Reid & Adams, 2001). Others found that family ownership had no significant influence on the use of formal human resources management practices (Newman & Sheikh, 2014; Wu et al., 2014).

The situation posed encourages to think about these specific qualities of family organisations that govern certain patterns to which the behaviour determining the total compensation model must conform.

On the other hand, the total compensation system consists of the addition of variable and fixed rewards. These integrate what is known as direct rewards, to which indirect financial and non-financial reward is added, resulting in extrinsic reward. Likewise, intrinsic compensation is also taking into account, forming a total adhesion known as total remuneration or total compensation. Problems relating to compensation are considered to be one of the main challenges faced by family businesses (Michiels et al., 2017).

Generally, compensation is understood as the process of planning the factors to be included in the salary system, coordinating, organising, communicating, applying, controlling and evaluating them (Morales & Velandia, 1999). For this reason, it is evident its weight on organisational behaviour in these kinds of businesses, given that, moreover, the business’s values, objectives and culture are taken into account (Lawler, 1990).

The essence of the family shapes this nature and provides a perspective which impacts on behaviour, since compensation systems are part of the process which helps employees to achieve their objectives (Cummings & Worley, 2001). This is, in turn, a key objective of total compensation, since keeping in mind that measures lead to behaviour is considered as a key element in businesses. Likewise, rewarding appropriate behaviour leads to obtain the desired results are obtained (Bussin, 2009). This emphasises the fact that a total compensation system directed towards the desired organisational behaviour of every generation of employees may be essential (Van Rooy, 2014).

Another sense which gains importance in the developed analysis is that compensation is understood as a set of rules and procedures used to established or maintain equal and fair salary structures in the organisation (Chiavenato, 2002).

The salary structure is based on the following main pillars:

- Fixed remuneration: formed by the agreed salary, called basic salary, and the voluntary salary, which can be presented under personal bonus payments, due to job position, and extraordinary bonuses.

- Variable remuneration: section of payments which are not guaranteed, since the employee’s benefits are directly linked to a framework of work effectiveness, whether this is in the short term or long term, made up of bonuses, incentives, prizes for business objectives and awards.

Total compensation is the result of the addition of fixed and variable remuneration, as well as indirect fringe benefits, payment in kind, and certain goods or products belonging to the business, such as cars, tax benefits, business services, as well as anything that consists of non-financial and intangible elements which conform to the attributes that workers receive, transcending the concept of monetary remuneration; for example, the business’ organisational culture, personal development and the family business environment.

This is based on the deductive method, using the family environment as a starting point to study the behaviour of the people which results in the total compensation method, in order to pose three specific hypotheses which support the objectives of the exploratory study:

Regarding the first hypothesis and once the different types of remuneration making up total compensation are proposed, direct financial extrinsic reward, which is fixed, provides more positive results than the rest, since it is the most valued; as a result, it conditions variables depending on organisational behaviour:

Hypothesis 1: Direct financial extrinsic reward, which is fixed, provides more positive results than the rest.

In accordance with the second hypothesis, a positive correlation arises between human resources professionals and their impact on effective compensation policy development management, as well as the operation of total compensation. This is based on the fact that organisational behaviour is responsible for studying people within an organisation and how their behaviour influences performance:

Hypothesis 2: A positive correlation arises between human resources professionals and their impact on effective compensation policy development management, as well as the operation of total compensation.

By focusing on the third hypothesis, independent variables of absenteeism, rotation and productivity appear, conditioning organisational behaviour. The model presented by Robbins is used as a reference point for this approach, assuming as dependent variables at individual, group and organisation level, those conditioning the behaviour of people in the organisation, even though other independent conditioning factors are present, being integrated by the variables initially stated: rotation, absenteeism and productivity (Bowie-McCoy et al., 1993; Kruse, 1993; Peterson & Luthans, 2006; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1997):

Hypothesis 3: Independent variables of absenteeism, rotation and productivity appear, conditioning organisational behaviour.

3. Materials and Methods

The approach of this research is empirical-analytical and is considered to be an exploratory study, since it is based on the theory to cover and explain the behaviour of a particular phenomenon: total compensation in family businesses. The study is descriptive and transversal, as it aims to characterise the analysis’ dimensions: family organisations, the people in said organisation, the compensation strategy and total compensation.

For that purpose, independent variables of organisational behaviour (Robbins, 1992) are analysed aiming at proving their importance and repercussion on the organisation’s dependent variables: the influence of strategic management and the adoption of certain compensation policies, as well as other with a transversal impact on the management of the family business and its members.

The survey population is made up of human resources professionals from a family business in the province of Malaga, Spain.

Table 1. Population, sample and participants

|

No. businesses |

Population% |

Sample% |

|

|

Population |

631 |

100% |

|

|

Sample |

105 |

17% |

100% |

|

Participants |

40 |

6% |

38% |

Source: authors of the paper

Table 2. Business sector of organisations

|

Sector |

No. businesses |

% |

|

Hospitality |

6 |

15.00% |

|

Business and Services |

8 |

20.00% |

|

Metal Industry |

9 |

22.50% |

|

IT and Engineering |

6 |

15.00% |

|

Others |

11 |

27.50% |

Source: authors of the paper

Table 3. Organisation staff

|

No. of workers |

No. |

% |

|

From 1 to 49 |

8 |

20.00% |

|

From 50 to 250 |

16 |

40.00% |

|

More than 250 |

16 |

40.00% |

Source: authors of the paper

The method used for the research analysis is a questionnaire-style tool (Arribas, 2004; Murillo, 2006). The development, design planning and subsequent preparation is based on previous works linked to the analysis of independent variables of organisational behaviour and the state of the company itself (Bussin & Rooy, 2014; Nienaber, 2011), without forgetting previous studies on compensation practices (Hatice, 2012; Machorro et al., 2008; Madero, 2012; Sánchez-Alcaraz & Parra, 2013).

The questionnaire is designed on the basis of previous tools, such as “scales on compensation practices PRG-13 and PRE-21” (Boada-Grau et al., 2012) for the elaboration of the structure and development process of items relating to the subject of the study and, finally, the “Measure of human resource practices: psychometric properties and factorial structure of the questionnaire PRH-33” (Boada-Grau & Gil-Ripoll, 2011). A Likert scale is used to measure the items, with 1 meaning “strongly disagree” and 5 meaning “strongly agree”, which is very useful for studying peoples’ behaviour (Mercadé et al. 2017, 2018, 2019).

4. Results

The results regarding human resources professionals are considerably positive in general terms, taking into account that these professionals are part of the management of the family organisation and bear in mind their capacity to influence the family business on the basis of remuneration policies aligned with the strategic management. In accordance with the hypothesis two, it is therefore deduced that, effectively, human resources professionals influence the organisation. This fact favours the development and subsequent application of the practices studied under the total compensation model in family businesses, positively impacting them. Since most of the human resources professionals are part of management committees and influence the organisation, combined with the fact that compensation is aligned with the organisation’s strategy, the hypothesis is verified

Table 4. Are they a member of the Management Committee?

|

Answer |

No. |

% |

|

Yes |

24 |

60.00% |

|

No |

16 |

40.00% |

Source: authors of the paper

Table 5. Do they have the ability to influence the Management Committee?

|

Answer |

No. |

% |

|

Yes |

29 |

72.50% |

|

No |

11 |

27.50% |

Source: authors of the paper

Table 6. Are the HR policies aligned with the organisation’s strategy?

|

Answer |

No. |

% |

|

Yes |

24 |

60.00% |

|

No |

16 |

40.00% |

Source: authors of the paper

On the other hand, when it comes to evaluating the results regarding the importance of dependent variables that condition organisational behaviour, as well as its correlation with the compensation policy, interesting data are gathered. These data refer to motivation, leadership and culture, based on a qualitative item.

It is concluded that, regarding the conclusions on organisational behaviour following Robbins’s model, positive dimensions of the analysed dependent variables mentioned are obtained, thus verifying the third hypothesis (as an individual through motivation, as a group through leadership and, lastly, as an organisation through culture), and its weight in order to achieve internal variables.

Table 7. In general, which factors do you think condition staff behaviour in your organisation (rotation, satisfaction, absenteeism, etc.)?

|

Aspect |

% |

|

Job stability |

40.00% |

|

Importance of human capital and the sense of belonging to the group |

20.00% |

|

Flexibility of hours and days, work-life balance |

20.00% |

|

Motivation |

15.00% |

|

Others (professional career, quality, etc.) |

15.00% |

Source: authors of the paper

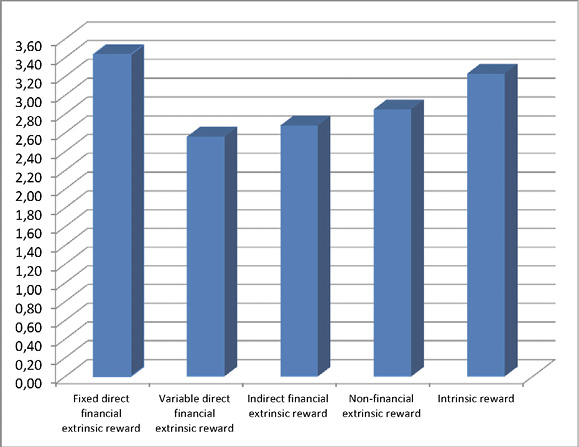

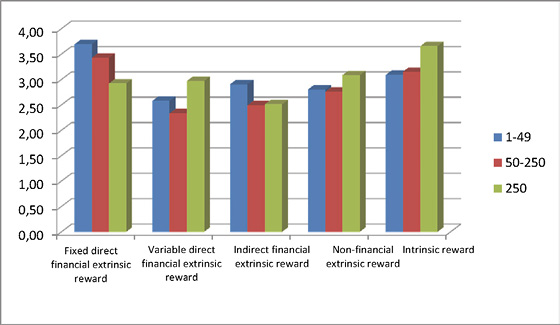

Lastly, with regards to the first hypothesis, it is considered relevant to devote a section in which the results obtained are presented in more depth, given that, although the empirical evidence is enough to conclude that fixed direct financial extrinsic reward is more valued and conditions dependent variables of organisational behaviour—as stated before—other approaches presented are also fulfilled; that is to say, the analysis allowed to detect that the size of the family business, in turn, influences the determination of the preferred compensation model, since in the case of organisations with more than two hundred and fifty people, intrinsic reward is more valued than other types, thus shedding light on a new divergence in the study of this matter. As a result, the hypothesis proposed is verified following the approaches in the literature consulted before this study was conducted.

Accordingly, although the new compensation models, which are linked to this new industrial revolution formulated on massive amounts of information, lead to a commitment to human capital and the retention of talent, as they provide better results both in non-financial and intrinsic remuneration, it is deduced that these new concepts seem to go against professionals’ current valuation. This is due to the fact that although organisations are increasingly supporting total compensation, there is still an important point of reference towards fixed remuneration. As a result, the first hypothesis is verified.

Figure 1. Remuneration levels in total compensation

Source: authors of the paper

If data are crossed with the size of the organisations, the fixed direct financial extrinsic reward is higher in organisations with 1-49 employees, where intrinsic reward exceeds them.

Figure 2. Reward levels in total compensation according to the organisation’s size

Source: authors of the paper

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Firstly, based on the results, it can be stated that family businesses consider total compensation to be an interesting model, although they indicate a clear preference for fixed reward. An exception is found for businesses with more than 250 employees, where the focal point is more inclined to intrinsic reward.

In some studies (Carrasco & Sánchez, 2014; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2003) it has been discovered which characteristics define the compensation practices of family businesses compared to non-family businesses.

In general, employees’ remuneration in family businesses is mainly fixed, while variable remuneration barely exists. However, it should be stated that directors who are not part of the family receive more fixed remuneration instead of variable or in kind compensation in comparison to family members. Nevertheless, it should be noted that some types of businesses design systems which are more orientated towards performance. In this sense, it can be concluded that Directors, both family members and non-family members, are compensated more adequately –less fixed salary and more variable remuneration (annual bonus) in companies with a higher average seniority and belonging to the industrial sector and other services. Therefore, there are no significant differences in treatment with regard to the existence or non-existence of a family link. Other employees are compensated to a greater extent on the basis of bonuses or incentives—whether in the short or long term—by family businesses with mixed management and larger size which belong to the industrial section (Carrasco & Sánchez, 2014).

Moreover, regarding family businesses, there are also studies which find differences between types of employees. For example, incentives usually have less weight on the total salary for family employees compared to non-family employees (Pérez et al., 2007) and the opposite with regards to fixed salaries. Additionally, if they are not the business owner, extra compensation given to family members are often fixed by emotional and altruistic criteria rather than their efficiency at their job. Family owners and entrepreneurs understand that this path is a way of helping family members with less resources.

Thus, one of the most significant risks of family businesses is that, with the aim of strengthening emotional and family ties, the business management considers making special compensation packages for employees who are family members, using indirect remuneration; that is, compensating family members using specific goods such as company cars, mobiles, trips, etc. This has a devastating effect on the rest of the employees’ perception of equality and supposes a reason for high dissatisfaction and work disputes that damage the business’s efficiency.

If family businesses are able to achieve balance, equality and professionalism when compensating their employees, regardless of their family ties, whose compensation will come through ownership shares, they will undoubtedly obtain an advantage with regards to employee satisfaction and business productivity (Carrasco & Sánchez, 2014). Non-managerial employees’ salary of family owned and managed businesses is lower and have a higher fixed amount in comparison to employees working for a professionalised family business (Sánchez-Marín et al., 2010).

Secondly, a positive correlation appears between compensation and the organisation’s strategy, as well as its evaluation and correction in accordance with the modifications in the business’s structures and systems, as well as processes, technology and new demands that arise as a result of these changes.

Some studies highlight that one of the main aspects that should be considered when designing a current family business is its employees’ compensation system, since aligning the business’s performance and results with workers’ needs and compensations represents a challenge (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2003).

Family businesses are characterised by having few managers and, therefore, an operating base of employees that is considerably larger in comparison to non-family businesses (Van Steel & Stunnenberg, 2006). Consequently, non-managerial employees’ compensations acquire even more relevance (Carrasco & Sánchez, 2014), since both in terms of cost—which may amount to 80% of operative costs—and motivation, they are more representative of the business’reality in the design of compensation than those relating to management staff.

Finally, human resources professionals mainly form part of the organisations’ management committees and have the necessary influence to decide the convenience of the application and development of compensation practices through them, with a clearly positive influence on the strategic dynamic of family businesses.

Studies on human resources practices in family businesses are particularly important if they also consider the particularities of these organisations. Generally, the orientation of said practices is conditioned by the complexity of relationships between family members, non-family members and the business (Pérez et al., 2007).

Despite the importance of human resources for the business’s competitiveness, few studies have focused on the analysis of the best management practices to attract, keep and motivate the most efficient employees for family businesses (Carrasco & Sánchez, 2014). Research has been mainly carried out for large businesses and to a lesser extent for SMEs (De Kok et al., 2006); however, barely any studies are found on human capital management in family businesses, even though the importance of human resources and its management in these types of organisations are continuously highlighted (Astrachan & Kolenko, 1994; Reid & Adams, 2001). Hence, the purpose and importance of this article to discover and analyse the development of human resources in family businesses, characterising the compensation practices used in these businesses.

Ultimately, despite the improvements required—particularly by family businesses and smaller businesses, and generally by all businesses regarding compensation policies—it can be stated that the family businesses analysed show an efficient orientation in the use of their human resources (Ashtrachan & Kolenko, 1994).

As stated at the beginning of this paper, the study of total compensation in family businesses is not only of great interest, as supported by the literature discussed, but it also allows to cover small gaps that have not been filled yet and focuses on the unique problem present in this type of business with an outstanding relevant weight in the international market.

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Investigation

As in any study of this kind, a series of limitations are found in different aspects of the analysis which must be considered:

a) With regards to the method, the information outlined in the survey carried out does not encompass the maximum that such a broad and interesting topic may cover. Likewise, it is important to highlight that more research of greater analytical-statistical rigour on this topic must be proposed to complement the data presented in this study.

b) As for the sample, it is carried out on professionals in human resources departments in organisations in the city of Malaga; as a result the sample constitutes a limited sample in geographical terms. The aforementioned respondents are in charge of different functions in their respective businesses which also gives certain heterogeneity to the sample. Lastly, it is also considered relevant to highlight that it does not cover the wide range of functions involved in human resources, thus the sample does not have all of the desired perspectives on the subject.

c) Lastly, based on the sample’s limitations, it would be a mistake to extrapolate the information provided by the study without considering the essential difference to be considered in different contexts. It is also essential to remember the need to pay attention and promote future studies in an increasingly changing and disruptive environment.

As a result of all of the above, future lines of investigation are proposed which serve as an addition to the conclusions and results obtained in the study conducted.

Firstly, since the family businesses’ size was the main discriminatory variable regarding results, to observe the potential changes in preferences and the level of importance of the compensation package, it would be interesting to propose in the analysis a discrimination focused on more demographic terms, as for example, the worker’s gender, in order to consult any possible discrepancies to be taken into account. With the importance of the incorporation of women into the business world, and specifically, to the family business, this seems to be quite topical.

Furthermore, in order to understand to what extent these specific results are transferable to other cities, it would be essential to broaden and repeat this study in other areas. In this case, the different ways of understanding total compensation would be revealed, whether on a purely cultural level or based on other determining factors.

Lastly, the examination of the underlying differences between family businesses and other business models, as regards of human resources, beyond total compensation, also generates and proposes debates and questions which may be quite attractive for future research, such as employee training in family businesses, on-site organisational behaviour or the approach of the promotion strategy.

References

Anneleen, M. (2017). Formal compensation practices in family SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(1), 88-104. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-12-2015-0173

Arribas, J. (2004). Diseño y validación de cuestionarios. Matronas Profesión, 5(17), 23-29.

Astrachan, J. & Kolenko, T. (1994). A neglected factor explaining family business success: Human resource practices. Family Business Review, 7, 251-262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1994.00251.x

Beckhard, R. & Dyer JR, W. G. (1983). SMR forum: Managing change in the family firm-Issues and strategies. Sloan Management Review, 24(3), 59-66.

Boada-Grau, J., Costa-Solé, J., Gil-Ripoll, C., & Vigil-Colet, A. (2012). Desarrollo y validación de dos escalas sobre las prácticas de retribución: PRG-13 y PRE-21. Psicothema, 24(3), 461-469.

Boada Grau, J. B. & Ripoll, C. G. (2011). Medida de las prácticas de recursos humanos: Propiedades psicométricas y estructura factorial del cuestionario PRH-33. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 27(2), 527-535.

Bowie-McCoy, S. W., Wendt, A. C., & Chope, R. (1993). Gainsharing in public accounting: Working smarter and harder. Industrial Relations, 32, 1432–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.1993.tb01058.x

Brown, D. (2001). Reward strategies: From intent to impact. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Bussin, M. (2009). Exploring the link between incentives and motivation. Johannesburg: 21st century pay solutions group. Available at: http://www.21century.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=64:exploring-the-link-between-incentives-and-motivation&catid=61:articles&Itemid=55

Bussin, M. & Rooy, D. J. (2014). Total rewards strategy for a multi-generational workforce in a financial institution. Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v12i1.606

Carrasco, A. & Sánchez, G. (2014). El capital humano en la empresa familiar: Un análisis exploratorio en empresas españolas. Revista FIR, FAEDPYME International Review, 3(5), 19-29. https://doi.org/10.15558/fir.v3i5.79

Cardon, M. S. & Stevens, C. E. (2004). Managing human resources in small organizations: What do we know? Human Resource Management Review, 14(3), 295-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2004.06.001

Carlson, D. S., Upton, N., & Seaman, S. (2006). The impact of human resource practices and compensation design on performance: An analysis of family‐owned SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(4), 531-543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2006.00188.x

Catry, B. & Buff, A. (1996). Le gouvernement de l’entreprise familiale. Publi-union Editions.

Chiaveneto, I. (1993). Teoria geral da administração. São Paulo: McGraw-Hill.

Chiavenato, I. (2002). Gestión del talento humano. Bogotá: Mc Graw Hill.

Cummings, T. G. & Worley, G. G. (2001). Essentials of organisational development and change. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Publishing.

De Kok, J., Uhlaner, L., & Thurik, A. (2006). Professional HRM practices in family owned-managed enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management, 44, 441-460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2006.00181.x

Delgado-Planás, C. (2004). La compensación total flexible: Conquistar el talento en el siglo XXI. Tesis doctoral. Universitat Abat Oliba CEU, Barcelona.

Gallo, M. A., Tàpies, J., & Cappuyns, K. (2004). Comparison of family and nonfamily business: Financial logic and personal preferences. Family Busines Review, 17(4), 303-318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00020.x

Gómez-Mejia, L. R., Larraza, M., & Makri. M. (2003). The determinants of CEO compensation in family-controlled public corporations. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 226–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040616

Graham, M. E., Murray, B., & Amuso, L. (2002). Stock-related rewards, social identity, and the attraction and retention of employees in entrepreneurial SMEs. En J. A. Katz & T. M. Welbourne (Eds.) Managing People in Entrepreneurial Organizations. Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth, vol. 5 (pp. 107-145). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1074-7540(02)05006-7

Hatice, O. (2012). The influence of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards on employee results: An empirical analysis in Turkish manufacturing industry. Business and Economics Research Journal, 3(3), 29-48.

Heneman, R. L., Tansky, J. W., & Camp, S. M. (2000). Human resource management practices in small and medium-sized enterprises: Unanswered questions and future research perspectives. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(1), 11-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870002500103

Kruse, D. L. (1993). Profit sharing: Does it make a difference? Kalamazoo, MI: W. E. Upjohn Institute. https://doi.org/10.17848/9780585261614

Lawler, E. E. (1990). Strategic pay, aligning organizational strategies and pay systems. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Leon-Guerrero, A. Y., Mc Cann, J. E., & Haley, Jr, J. D. (1998). A study of practice utilization in family businesses. Family Business Review, 11(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1998.00107.x

Machorro, F., Rosado, M., & Romero, M. V. (2008). Diseño de un instrumento para evaluar el clima organizacional en un complejo petroquímico del Estado de Veracruz. Universidad Autónoma Estado de México.

Madero, S. M. (2012). Análisis de los procesos de recursos humanos y su influencia en los bonos y prestaciones. Cuadernos de Administración, 28(48), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.25100/cdea.v28i48.453

Marlow, S. & Patton, D. (2002). Minding the gap between employers and employees. Employee Relations, 24(5), 523-539. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450210443294

McCann, J. E., Leon Guerrero, A. Y., & Haley Jr, J. D. (2001). Strategic goals and practices of innovative family businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(1), 50-59. https://doi.org/10.1111/0447-2778.00005

Mercadé-Melé, P., Molinillo, S., & Fernández-Morales, A. (2017). The influence of the types of media on the formation of perceived CSR. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 21, 54-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjme.2017.04.003

Mercadé-Melé, P., Molinillo, S., Fernández-Morales, A., & Porcu, L. (2018). CSR activities and consumer loyalty: The effect of the type of publicizing medium. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 19(3), 431-455. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2018.5203

Mercadé-Melé, P., Molina-Gómez, J., & Garay, L. (2019). To green or not to green: The influence of Green Marketing on consumer behaviour in the hotel industry. Sustainability, 11, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174623

Michiels, A., Voorderckers, W., Lybaert, N., & Steijvers, T. (2017). Compensation policies in family and non-family SMEs: Survey evidence from Flanders. Accountancy & Bedrijfskunde, 2017(4), 3-18.

Morales, J. & Velandia, N. (1999). Salarios: Estrategia y sistema salarial o de compensaciones. Mc Graw Hill.

Murillo, J. (2006). Cuestionarios y escalas de actitudes. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Facultad de Formación de Profesorado y Educación.

Murlis, H. (1996). Pay at the Crossroads. London: Institute of Personnel and Develop.

Newman, A. & Sheikh, A. Z. (2014). Determinants of best HR practices in Chinese SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21(3), 414-430. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-05-2014-0082

Nienaber, R. (2011). The relationship between personality types and reward preferences. Acta Commercii, 11(2), 56-79. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v11i2.153

Peterson, S. J. & Luthans, F. (2006). The impact of financial and nonfinancial incentives on business-unit outcomes over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.156

Pérez, M. J., Basco, R., García-Tenorio, J., Giménez, J., & Sánchez, I. (2007). Fundamentos en la dirección de la empresa familiar. Madrid: Thomson.

Reid, R. & Adams, J. (2001). HRM - A survey of practices within family and non-family firms. Journal of European Industrial Training, 6, 310-320. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590110401782

Robbins, S. P. (1992). Comportamiento organizacional. 10ª Ed: Pearson Education.

Rutherford, M. W., Buller, P. F., & McMullen, P. R. (2003). Human resource management problems over the life cycle of small to medium‐sized firms. Human Resource Management, 42(4), 321-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.10093

Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. J. & Parra, M. C. (2013). Diseño y validación de un cuestionario de satisfacción laboral para técnicos deportivos (CSLTD) Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 8(23), 119-127. https://doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v8i23.296

Sánchez, G., Carrasco, A. J., & Madero, S. M. (2010). Retribución de los empleados en la empresa familiar: Un análisis comparativo regional España-México. Cuadernos de Administración, 23(41), 37-59.

Saquib, S., Abrar, M., Sabir, H. M., Bashir, M., & Baig, S. A. (2015). Impact of tangible and intangible rewards on organizational commitment: Evidence from the textile Sector of Pakistan. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 5, 138-147. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2015.53015

Sheehan, M. (2014). Human resource management and performance: Evidence from small and medium-sized firms. International Small Business Journal, 32(5), 545-570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242612465454

Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., Dino, R. N., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2001). Agency relationships in family firms: Theory and evidence. Organization Science, 12(2), 99-116. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.2.99.10114

Stajkovic, A. D. & Luthans, F. (1997). A meta-analysis of the effects of organizational behavior modification on task performance 1975–1995. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 1122–1149. https://doi.org/10.2307/256929

Steckerl, V. (2011). Modelo explicativo de una empresa familiar que relaciona valores del fundador, cultura organizacional y orientación al mercado. Pensamiento y Gestión, 20, 194-215.

Van Steel, A. & Stunnenberg, V. (2006). Linking business ownership and perceived administrative complexity. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13, 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000610645270

Ward, J. (2016). Perpetuating the family business: 50 lessons learned from long lasting, successful families in business (pp. 132-133). Springer.

Ward, J. L. (1988). The special role of strategic planning for family businesses. Family Business Review, 1(2), 105-117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1988.00105.x

Walsh, G. (2011). Family business succession: Managing the all-important family component. KPMG Enterprise.

Worldatwork (2000). Total rewards: From strategy to implementation. WorldatWork, Scottsdale, AZ.

Wu, N., Bacon, N., & Hoque, K. (2014). The adoption of high performance work practices in small businesses: The influence of markets, business characteristics and HR expertise. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(8), 1149-1169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.816865

Thank you to our peer reviewers 2020

A peer-reviewed journal would not survive without the generous time and insightful comments of the reviewers, whose efforts often go unrecognized. Although final decisions are always editorial, they are greatly facilitated by the deeper technical knowledge, scientific insights, understanding of social consequences, and passion that reviewers bring to our deliberations. For these reasons, the editors and staff of European Journal of Family Business would like to publicly acknowledge our peer reviewers.

Francisco José Acedo González, University of Seville, Spain

Mikel Alayo Anasagasti, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Spain

Cristina Alvarado Álvarez, University of Barcelona, Spain

FernandoÁlvarez Gómez, University Oberta of Catalunya, Spain

Gloria Aparicio de Castro, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Spain

Lujain Bayo Baitalmal, University of Málaga, Spain

Myriam Cano Rubio, University of Jaén, Spain

José Carlos Casillas Bueno, University of Seville, Spain

Julio Diéguez Soto, University of Málaga, Spain

Manuel Ángel Fernández Gámez, University of Málaga, Spain

Gema García Piqueres, University of Cantabria, Spain

Marc García Alias, University of Lleida, Spain

María Elena Gómez-Miranda, University of Granada, Spain

Remedios Hernández Linares, University of Extremadura, Spain

Paula María Infantes Sánchez, Esade Business School, Spain

Txomin Iturralde Jainaga, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Spain

Inés Lisboa, Polytechnic of Leiria, Portugal

Abel Lucena, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Montserrat Manzaneque Lizano, University of Castilla La Mancha, Spain

Mercedes Mareque Álvarez-Santullano, University of Vigo, Spain

Maria del Pilar Martín Zamora, University of Huelva, Spain

Ángel Meroño Cerdán, University of Murcia, Spain

Francisco Manuel Morales Rodríguez, University of Granada, Spain

Joaquín Monreal Pérez, University of Murcia, Spain

Ana María Moreno Menéndez, University of Seville, Spain

Francisca Parra Guerrero, University of Malaga, Spain

Elena Rivo López, University of Vigo, Spain

Alexander Rosado-Serrano, University of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico

Dolores Tous Zamora, University of Málaga, Spain

Mónica Villanueva Villar, University of Vigo, Spain