European Journal of Family Business (2020) 10, 64-77

How do family responsible ownership practices enhance social responsibility in small and medium sized family firms?

Cristina Aragon-Amonarriza*, Cristina Iturrioz-Landarta

a University of Deusto

Received 2019-09-17; accepted 2020-01-21

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M14

KEYWORDS

Social responsibility, family responsible ownership practices, stewardship theory, small and medium family firms.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M14

PALABRAS CLAVE

Responsabilidad social, practicas de propiedad familiar responsable, teoría de stewarship, pequeñas y medianas empresas familiares.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i1.6688

2444-877X/ © 2020 European Journal of Family Business. Published by Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-SA license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).

*Corresponding author

E-mail: cristina.aragon@deusto.es

Abstract This paper aims to measure the influence of the family responsible ownership practices and the socially responsible vision of families on the socially responsible behaviour of family small and medium firms. To reach this purpose, we define six hypotheses and we apply an empirical testing of an integrative model. Based on a sample of 84 family SMEs, structural equation modelling is applied to test the existence of potential relationships within and between both constructs. This study reveals the relevance of the family responsible ownership practices as a driver that influences socially responsible practices in family SMEs. The results confirmed that positive relationships exist between each of the following three antecedents: a) responsible management succession, b) responsible financial resource allocation and c) professionalism and social responsibility among family SMEs. Additionally, a positive relationship between family responsible ownership practices and family firm social responsibility was found.

¿Cómo potencia la propiedad familiar responsable la responsabilidad social en las

pequeñas y medianas empresas familiares?

Resumen Este documento tiene como objetivo medir la influencia de las prácticas de propiedad familiar responsable y la visión socialmente responsable de las familias sobre el comportamiento socialmente responsable de las pequeñas y medianas empresas familiares (pymes). Para alcanzar este propósito, definimos seis hipótesis y aplicamos una prueba empírica de un modelo integrador. Sobre la base de una muestra de 84 pymes familiares, utilizamos un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales para evaluar posibles relaciones dentro y entre los constructos. Este estudio revela la importancia de las prácticas de propiedad familiar responsable como motor que influye en las prácticas de responsabilidad social en las pymes familiares. Los resultados confirman que existen relaciones positivas entre cada uno de los siguientes tres antecedentes: a) sucesión de gestión responsable, b) asignación responsable de recursos financieros y c) profesionalismo, que afectan a la responsabilidad social de las pymes familiares. Además, se encontró una relación positiva entre las prácticas de propiedad familiar responsable y la responsabilidad social de la pyme familiar.

Introduction

The influence of families on the decision making and operations strongly differentiates family firms (Chrisman et al., 2003b). According to Niehm et al. (2008), family-centred businesses may hold a unique perspective regarding socially responsible business behaviour. The involvement of the owning families in their businesses and their close ties to the community where they are located enhance their socially responsible behaviour. Socially responsible management refers to the activities voluntarily developed by a company concerning social and environmental issues in interactions with stakeholders (Hammann et al., 2009; Maclagan, 1999; Van Marrewijk, 2003). The socially responsible behaviour of firms is decisively driven by the individuals and top managers within an organisation and its perception of the relevance of ethics and social responsibility (SR) in the business arena (Quazi, 2003; Vitell and Ramos, 2006; Swanson, 2008). There are not socially responsible firms without socially responsible managers who are occasionally willing to sacrifice the objectives, interests and needs of their firms in favour of socially responsible actions (Hunt et al., 1990; Wood et al., 1986). However, this attitude of stewardship must be supported by the ethical behaviour of owners to be sustainable. Specifically, in the context of family SMEs, these relevant issues are highly determined by the owning families. In recent years, various authors have noted the lack of studies regarding SR in family firms and the need of expanding the theoretical framework in this field (Debicki et al., 2009; Spence, 2016). However, there is a currently increasing interest in the study of ethical focus, and SR among family firms (Campopiano and De Massis, 2015; Liu et al 2017, Martínez-Ferrero et al., 2016). The primary focus of the literature lied on the comparison between family and non-family enterprises. The differences between both groups were identified and diverse conclusions were obtained (Castejón and López, 2016; Laguir et al., 2016). Some researchers demonstrated that family firms act less ethically than non-family ones (Dyer and Whetten, 2006; Morck and Yeung, 2003). On the contrary, other studies show the higher family firms’ ethical behaviour comparing to non-family enterprises (Castejón and López, 2016; Laguir et al., 2016). Finally, we can find scholars that state that both groups of firms are equally ethical (Adams et al., 1996). As a result, we can conclude that this issue has not reached a clear consensus. Family involvement can be either a driver of good practices in terms of economic, social and environmental issues or conversely, it can undermine the responsible behaviour of a firm if, for example, SR is considered an added cost rather than an opportunity for value creation (Deniz and Cabrera, 2005). More recently, researchers have more closely examined the conditions and mechanisms that influence the ethical focus and social performance of family firms. In this sense, different elements have been analysed as critical antecedents of SR in family firms by different authors using different approaches (such as Aragón-Amonarriz et al., 2019; Bingham et al., 2011; Hammann et al., 2009; O’Boyle et al., 2010; and Sorenson et al., 2009). The values of decision makers are critical drivers of the SR in firms; particularly in family firms, these values must be supported by the family owners themselves. A collaborative dialogue perspective on the systemic nature of a family network (Sorenson et al., 2009) explains how ethical norms are developed in family firms. However, holistic studies of the key antecedents of SR among family firms remain scarce.

In this article, we suggest that understanding SR behaviour in family firms is not possible without analysing family responsible ownership practices (FROP) as the key antecedent of the stewardship attitudes of managers and thus of a firm’s socially responsible behaviour. Furthermore, we propose that critical family ownership practices, such as firm ownership succession, management succession, financial resource allocation and professionalism, which are considered possible facilitators of family and firm relationships (Berent-Braun and Uhlaner, 2012), in addition to the family vision of SR (Quazi and O´Brien, 2000), affect family firm’s socially responsible behaviour. This paper aims to measure the influence that the ownership practices and the SR vision exert on the family enterprises’ SR social responsibility. In order to capture this influence, we apply and empirically test an integrative model. In this model, the SR behaviour of firms is the dependent construct that embraces environmental, economic and social firm behaviours.

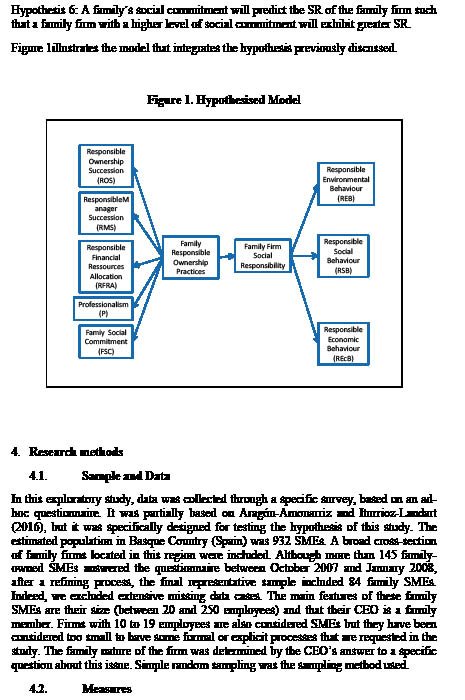

Specifically, as detailed below, we first theorise about the role of firm management in the socially responsible behaviour of firms; second, we present a review of the recent literature on SR in family firms; and, third, we focus on the theoretical development of a set of FROP. These theoretical relationships are summarised in Figure 1. The data source for this exploratory study was an ad-hoc survey. This survey was answered by 84 family SMEs, that constitute a representative sample for testing our hypotheses. Finally, we present the main results and conclusions.

This study’s main contribution is that it caters the family business literature with a framework that describes how family influences a firm’s SR behaviour, from which we derive practical implications for the management of family firms. The results obtained reveal the relevance of the FROP in explaining how family firm owners influence SR, clarifying the components of FROP and the antecedents of SR for family SMEs and illustrate the relationships among responsible ownership succession, responsible management succession, responsible financial resource allocation, professionalism, family social commitment and the SR of family firms.

Family firms’ social responsibility and the role of the owning families

Particularly in family firms understood as “a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families” (Chua et al., 1999, p.25), the owners, that is, the owning families exert a crucial role in SR behaviours.

Following Godos-Diez et al. (2011), corporate SR is defined as the level of firms’ involvement and concern regarding the voluntarily development of social and environmental behaviour. This issue is now an essential topic to both researchers and practitioner, as it addresses social concerns into firm strategy and operations. In this sense, several authors highlight the role of key decision makers, such as CEOs, in establishing ethical norms in a company (Desai and Rittenburg, 1997; Agle et al., 1999; Hemingway and Maclagan, 2004; Godós-Díez et al., 2011). The personal commitment of senior management to ethics is an essential part of what drives organisations to be proactive, socially responsible behaviour (Jones, 1995; Swanson, 1995).

The specificity of family enterprises roots in the integration of business and family (Habbershon and Williams, 1999; Sirmon and Hitt, 2003) and, stewardship is the fundamental ingredient of this integration; as Davis et al. (2010) stated, stewardship is considered the ‘secret sauce’ of family firms because it enables the pursuit of long-term, non-financial objectives (Westhead and Howorth, 2006; Zellweger and Nason, 2008). Stewardship theory is a perspective that deals with the role of top managers in firms given the separation between ownership and control (Davis et al., 1997; Wasserman, 2006; Chrisman et al., 2007) and that proposes the existence of ex-ante conditions that influence managerial thought and practice (Guidice and Mero, 2007). Specifically, the psycho-sociological view of corporate governance adopted by this theory depicts the steward role of managers (Davis et al., 1997). Their behaviour is such that pro-organisational or collectivist conduct yields higher utility than individualistic or selfish conduct (Chrisman et al., 2007); thus, acting cooperatively rather than opportunistically does not imply lack of rationality. Stewards preserve all stakeholders’ over exclusively shareholders’ welfare. In consequence, maximising the long-term value of firms is the main way of reaching stakeholders’ satisfaction, in particular when their interests are competing (Hernández, 2008). This stewardship theoretical framework is particularly relevant in extending the duty of firms beyond shareholders to other stakeholders (Gibson, 2000; Hernández, 2008; Kouzes and Posner, 1993; Manville and Ober, 2003) and thus in understanding the general orientation to socially responsible behaviour. In fact, Godós-Díez et al. (2011) have found that companies whose top managers can be considered ‘stewards’ are prone to develop and implement more ethical and social practices.

Precisely because of the absence of formal governance structures in family SMEs and the relevance of role modelling (Adams et al., 1996) as a means of promoting ethical behaviour in family firms, the SR of a family owner is transferred to the organisation through the family’s responsible behaviours and practices, which are intended to facilitate the family´s relationship with the business (Aronoff and Ward, 2002; Berent-Braun and Uhlaner, 2012; Gersick et al., 1997; Mustakallio et al., 2002; Neubauer and Lank, 1998). In this context, the main antecedents of SR in family firms have been already analysed applying different approaches. Following Deniz and Cabrera (2005), the family owners of firms have been associated with both positive and negative elements of relationships with stakeholders, which can be linked to different orientations towards SR. Their study concludes that a family firm is not a homogeneous group in terms of its orientation towards SR. This descriptive paper does not verify the antecedents of this heterogeneity or identify the reasons for their influence; however, due to the model of Quazi and O’Brien (2000) they employ in their analysis, it is suggested that one of the sources of these differences is the family vision of SR.

Other group of studies have analysed the mechanisms of developing ethics in family firms, such as fair processes (Van der Heyden et al., 2005) and collaborative dialogue within families (Sorenson et al., 2009). Regarding fair processes, Van der Heyden et al. (2005) state that when a family is an influential component of a business system, the application of justice in family firms is typically rendered more complex than in a non-family firm context. The authors defined some fundamental criteria that are essential to the effectiveness of fair processes in family firms and demonstrated how enhancing the use of fair process practices increases the satisfaction of agents who are associated with a firm and its performance. By contrast, Sorenson et al. (2009) focus on specific aspects from a family perspective, such as family point of view, and argue that family point of view is positively related to the presence of ethical norms in family firm owners. However, to be effective fair processes and family point of view must be translated into the professionalization of family governance behaviour and practices.

Other group of studies analyse the relation between issues concerning responsibility or ethics and family involvement (Bingham et al., 2011; O’Boyle et al., 2010). Bingham et al. (2011) highlight important differences in the socially responsible behaviour of family versus non-family firms and argue that a higher level of family or founder involvement in terms of stakeholder identity orientation leads to greater social performance regarding specific stakeholders. Again, this paper does not consider the different types of firms and their levels of family involvement, which may have implications for social performance, nor does it examine the context of privately held firms. O´Boyle et al. (2010) have found family involvement to be the antecedent of an ethical focus among family firms, and they conclude that family involvement affects ethical focus and that ethical focus predicts firm performance. These authors offer a stewardship perspective as a way in which family involvement relates to ethical focus. Thus, these authors acknowledge that the stewardship perspective in which good stewards are always believed to behave ethically should be critically examined in future studies. In addition, the authors strongly encourage future research to explore alternative means of assessing family involvement and family influence.

Therefore, understanding SR in family firms is not only a question of family involvement, family social commitment (Deniz and Cabrera, 2005; Quazi and O´Brien, 2000) and the particular behaviours - the fair processes and family point of view (van den Heyden, 2005; Sorenson et al, 2009)- of the family as owners are needed. In this sense, we consider FOP as the key antecedent of the stewardship attitudes of managers and thus of a family firm’s socially responsible behaviour. For this reason, in this paper, a set of critical FROP are identified, which are understood as an extension of the concept of responsible ownership (Aragon-Amonarriz and Iturrioz-Landart, 2016; Berent-Braun and Uhlaner, 2012; Lambrecht and Uhlaner, 2005; Uhlaner et al., 2007). The influence of FROP in socially responsible behaviours reveals the power of family owners in responsible decisions that are made by top managers and ultimately of the SR of family firms.

Hypothesis 1: FROP will predict the SR behaviour of family firms such that those firms with higher levels of FROP will exhibit greater SR.

The family responsible ownership practices and its influence on family firm social responsibility

Family responsible ownership practices focus on the specific situations in which a family may act re understood as specific firm behaviours on environmental, social and economic issues. Thus, and following other instruments that have been developed to measure SR (ESADE, 2007; Igalens and Gond, 2005) and the recommendations of Thompson and Smith (1991), this study builds the construct of family firm SR based on the commitment rather than perceptions the various stakeholders of firms, such as employees, value chain agents, the local community and society in general.

Additionally and regarding the FROP we identify four key areas: ownership succession and management succession, which represent the critical process of family firmss; financial resource allocation resulting from the main ownership position; professionalism or the prioritisation of a firm over one’s family; and the owning family social commitment.

Responsible management and owner succession

Succession is undoubtedly one of the most critical processes in the life cycle of a family firm (Brockhaus, 2004; Handler, 1994; Sharma, 2004; and Ward, 2004). Evidence suggests that mortality increases after succession has occurred (Bagby, 2004; Sharma et al., 2001), firms become vulnerable during succession periods, and personal goals or needs may be prioritised over the needs of a firm. In fact, succession decisions may be based on family needs rather than business requirements, and such decisions can create serious problems when these needs and requirements are incompatible (Bocatto et al., 2010; Frishkoff, 1994; Goldberg and Woodridge, 1993). The choice of a successor may also be primarily based on a family’s values rather than the capabilities of a chosen successor (Aronoff and Ward, 1992; Frishkoff, 1994). Finally, putting the succession process off is one of the most usual ethical violations (Gallo, 1998).

Although managerial and ownership succession are often considered in a same manner, we distinguish between them in terms of their influence in SR behaviour. First, responsible owner succession entails that owners are selected in consideration of their professional capabilities and values in terms of accomplishing the primary and direct goals of an owner family: to preserve the continuity of a firm under the family’s control (that is, the continuity of the firm and the family in the firm). Even if the family nature of a firm is questioned, the firm’s competitiveness is assured; consequently, succession demands the responsible behaviour of families with regard to their businesses. This decision can be influenced primarily by family interests or by the desire to preserve the continuity of a firm, which enables and reinforces the steward role of management and the SR of family firms.

Finally, responsible manager succession entails that managers are selected by considering their professional capabilities and values, such as formal and cultural competencies (Hall and Nordqvist, 2008), their ability to preserve the continuity of a firm, and a shared view of a firm and its purpose. This selection is a basic condition of ensuring an attitude of stewardship and the SR of family firms (Akhmedova et al., 2019; Cabeza-García et al., 2017).

Hypothesis 2: Responsible ownership succession will predict the SR of family firms such that those firms with higher levels of responsible ownership succession will exhibit greater SR.

Hypothesis 3: Responsible management succession will predict the SR of family firms such that those firms with higher levels of responsible management succession will exhibit greater SR.

Responsible financial resource allocation

The investment of family wealth in a firm may be considered a constraint by family owners. Some owners may primarily focus on receiving dividends or eventually harvesting assets, whereas other family owners may consider their firms to be investments and aim to preserve and increase their assets through the creation of value in their firm.

Following Berent-Braun and Uhlaner (2012), we can distinguish between two profiles. The first type of owner will defend a premature and excessive withdrawal of assets for benefits that include dividend payments and bonuses, which may result from the individual needs of family shareholders or a short-term focus, and may deplete the resources that a firm needs to ensure long-term survival. The second type of owner aims to retain necessary financial capital in a business for a longer period (thus the name ‘patient capital’; Sirmon and Hitt, 2003) and may make financial resources available to finance business development and expansion (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2005; Uhlaner and Berent, 2008).

This allocation of financial resources will substantially affect business competitiveness in the long term and will be a clear model of behaviour for managers, who will perceive such a firm as a source of personal goal satisfaction rather than as a source of stakeholder goal satisfaction. The responsible allocation of financial resources will enable strategic and sustainable investment to support firm competitiveness and to integrate social and environmental goals into the financial decisions of a firm in agreement with a larger vision of the purpose of the firm, thus supporting the stewardship attitude of the management and SR of such firms.

Hypothesis 4: Responsible financial resource allocation will predict the SR of family firms such that those firms with higher levels of responsible financial resource allocation will exhibit greater SR.

Professionalism

Following O´Boyle et al. (2010), we consider professionalism to reflect whether a firm is a ‘business-first’ firm or a ‘family-first’ firm (e.g., Ward, 1997). We propose that a socially responsible family will be professional in its behaviours and that this professionalism will be ‘contagious’ to the manager of such a firm and thus inspire a steward perspective that prioritises the interests of the firm over those of management.

Following Distelberg and Sorenson (2009), in an extreme example of a family-first system, resources move from a business to a family at the cost of the business. In this case, the goal is to use the business as a resource base while optimising the business in the current generation and minimising business growth. The development of the family is favoured over that of the firm, and there is little or no desire to build the business. The family’s control over the firm and prioritisation of its own interests may lead its managers to act similarly in pursuit of their own interests.

Similar to the family-first orientation, resources in business-first firms move from a family to its business but at the cost of the family. If the business is highly successful, then it may provide significant financial resources for the family. Even if this perspective could, in an extreme case, deplete the family’s resources and even destroy the firm (Distelberg and Sorenson, 2009), a socially responsible family aims to prioritise its firm over family interests by considering the family to be merely another stakeholder of the firm. This preference would influence the priorities of managers, who would accordingly prioritise the survival of the firm over their own interests.

Hypothesis 5: A family´s professionalism will predict the SR of its firm such that a family firm with a higher level of professionalism will exhibit greater SR.

Family social commitment

As for certain family owners, the main aim of their enterprises is catering goods and services that lead their enterprises to the profit maximization within the ‘rules of the game’ (regulation). This vision, based on the premise of the maximisation of the efficient use of resources, accords with the neoclassical approaches (Friedman, 1962, 1970). This type of ownership is associated with a narrow vision of social responsibility and eschews any restrictive traditions, ideologies or power relationships (Alvesson and Wilmott, 1992).

On the contrary, other owners try to integrate firm’s and society’s expectations concerning the environment preservation, the community development, and philanthropy. This broader responsibility insight builds sustainable social relationships (Quazi and O’Brien, 2000) and considers the demands of “[...] any group or individual that may affect or be affected by the achievement of business objectives” (Freeman, 1984, p. 25). As a result, a link to the society is built and enterprise’s long-term interests are ensured (Quazi and O’Brien, 2000). Indeed, companies should contribute to the community’s welfare, as its responsibilities extend beyond the short-term profit.

Companies may have different approaches to SR depending on their vision with regard to this issue (narrow or broad) and the results (costs or profits) that they associate with social commitments (Quazi and O’Brien, 2000). A similar conclusion is reached in the context of family firms (Deniz and Cabrera, 2005). In this context, we assume that the social commitment of family owners is shared by managers, who are also family members; thus, this context supports the stewardship attitude of the managers and SR of family firms.

Hypothesis 6: A family´s social commitment will predict the SR of the family firm such that a family firm with a higher level of social commitment will exhibit greater SR.

Figure 1illustrates the model that integrates the hypothesis previously discussed.

Figure 1. Model linking Family Responsible Ownership Practices and Family Firm Social Responsibility Behaviours

Research methods

Sample and data

In this exploratory study, data was collected through a specific survey, based on an ad-hoc questionnaire. It was partially based on Aragón-Amonarriz and Iturrioz-Landart (2016), but it was specifically designed for testing the hypothesis of this study. The estimated population in Basque Country (Spain) was 932 SMEs. A broad cross-section of family firms located in this region were included. Although more than 145 family-owned SMEs answered the questionnaire between October 2007 and January 2008, after a refining process, the final representative sample included 84 family SMEs. Indeed, we excluded extensive missing data cases. The main features of these family SMEs are their size (between 20 and 250 employees) and that their CEO is a family member. Firms with 10 to 19 employees are also considered SMEs but they have been considered too small to have some formal or explicit processes that are requested in the study. The family nature of the firm was determined by the CEO’s answer to a specific question about this issue. Simple random sampling was the sampling method used.

Measures

Testing the hypotheses was possible thanks to structural equation modelling applied to data collected from the beforementioned survey. Along the process of refinement of the initial 50 items, few items were removed from the first stage of the model. Table 1 lists the final 32 items of the measurement model. Table 2 summarises the results of the measurement model and presents the standardised coefficients for each item, the composite reliability, and the variance extracted for each construct. Regarding the tests of the interrelationships, a complete explanation can be found in the Results section.

Responsible ownership succession (ROS). The three items that are included are related to the formalization of the ownership succession process (from the lack of consideration to being completely formalised in a family protocol). These items capture one of the most frequently perceived ethical violations: delaying the succession process (Gallo, 1998) (see Table 1).

Responsible management succession (RMS). The three items that are included are related to the criteria for selecting future managers and are intended to capture whether professional capabilities and values (formal and cultural competences, following Hall and Nordqvist, 2008) are sought and ensured.

Responsible financial resource allocation (RFRA). Two main concepts are included: the abusive use of the financial resources or assets of a family firm and the necessary investments in the strategic needs of such a firm. Three of the four items that are included are related to the abusive use of firm financial resources or assets for the benefit of family members. The fourth item captures whether a family is reluctant to make an investment to maintain or improve the competitiveness of its firm.

Professionalism (P). The two first items describe the decisions between the family-first and firm-first systems (Distelberg and Sorenson, 2009) with regard to issues of leadership, competitiveness and delegation. Finally, an item concerning the level of firm transparency of the firm, which is a criterion of good firm governance, is included.

Family social commitment (FSC). Following Quazi and O’Brien (2000), we associate the SR vision of a family with its social commitment. For this reason, we adapt the scale of commitment by Cook and Wall (1980) and develop four items (see Table 1) to capture the commitment of the family owners with regard to the role of the family firms in society.

In order to capture the SR of family firms ESADE, 2007; Igalens and Gond, 2005.), the main SMEs’ stakeholders (such as workers or the local community, among others) have been considered and a 39-item scale of SR for SMEs has been obtained (Narvaiza et al., 2009). Following Thompson and Smith (1991), the scale designed focuses on behaviour rather than on expectations or feelings. The final scale’s psychometric properties were verified. As a result, we state that its reliability and validity are acceptable and can explain 64.2% of the total variance. This scale measures the three SR constructs included in Figure 1, namely, Responsible environmental behaviour (REB), Responsible social behaviour (RSB) and Responsible economic behaviour (REcB).

Table 1. Items and scales that were used to measure the constructs of the model

|

FAMILY RESPONSIBLE OWNERSHIP PRACTICES (FROP) |

|

|

RESPONSIBLE OWNERSHIP SUCCESSION (ROS) |

|

|

ROS1 |

The firm plans and communicates in a timely manner the ownership succession process when the owners are still active in the firm. |

|

ROS2 |

The owner firm has developed a family shareholder agreement to formalise the ownership succession process. |

|

ROS3 |

Family members are being prepared for future firm ownership and leadership. |

|

RESPONSIBLE MANAGEMENT SUCCESSION (RMS) |

|

|

RMS1 |

Above all, the owners aim to guarantee that the firm management leadership remains within the family in the future regardless of their leadership ability or management issues. |

|

RMS2 |

Above all, the owners aim to guarantee that people have received the necessary training and have adequate abilities in terms of the future management of the firm. |

|

RMS3 |

The professional career of prepared managers has been limited to guaranteeing the presence of owners or family members in the key positions of the firm. |

|

RESPONSIBLE FINANCIAL RESOURCE ALLOCATION (RFRA) |

|

|

RFRA1 |

There is resistance in the family ownership to allocating the necessary financial resources to the business. |

|

RFRA2 |

The family ownership frequently asks for dividend shares above the level that is recommended for business sustainability. |

|

RFRA3 |

The owners or family members typically charge personal expenses to the business. |

|

RFRA4 |

The owners or family members do not use the firm’s assets properly. |

|

PROFESSIONALISM (P) |

|

|

P1 |

Useful channels of communication have been established within the firm to transmit relevant information about the firm periodically. |

|

P2 |

In the daily operations of the firm, the preferential treatment of family owners or family members may occasionally contrast with the interests of the business itself. |

|

P3 |

The firm shares have been distributed among the family heirs independently of their ability to lead the family business. |

|

FAMILY SOCIAL COMMITMENT (FSC) |

|

|

FSC1 |

The firm considers itself an agent of the society in which it operates. |

|

FSC2 |

The firm owners would like to feel that the firm has contributed to society in general or to some of its stakeholders, such as employees and consumers. |

|

FSC3 |

The firm would not cease its contribution to society even in situations in which the benefits for the firm were unclear. |

|

FSC4 |

The firm is committed to society. |

|

RESPONSIBLE ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIOUR (REB) |

|

|

REB1 |

The firm is concerned about environmental issues despite the lack of risk of economic penalties. |

|

REB2 |

The firm has an environmental certificate or is currently obtaining such a certificate. |

|

REB3 |

The firm assigns resources to processes that aim to minimise waste and recycle beyond the legally established minimum. |

|

REB4 |

The firm assigns resources to processes that aim to reduce atmospheric emissions and/or acoustic contamination beyond the legally established minimum. |

|

REB5 |

The firm assigns resources above the legally established minimum to projects that aim to optimise the use of energy and water. |

|

RESPONSIBLE SOCIAL BEHAVIOUR (RSB) |

|

|

RSB1 |

The firm aims to guarantee job stability to its employees, and the firm has achieved rotation rates that are lower than the industry average. |

|

RSB2 |

The firm invests in improving employee satisfaction and has reduced absenteeism to a greater extent than the industry average. |

|

RSB3 |

The firm evaluates the effects of its activity on the local community and participates in the identification of solutions to community problems. |

|

RSB4 |

When hiring new personnel, the firm avoids discrimination based on factors that include gender, age, friendship or family relationships. |

|

RSB5 |

The firm wage increases based on professional performance. |

|

RESPONSIBLE ECONOMIC BEHAVIOUR (REcB) |

|

|

REcB1 |

The firm has a public ethical commitment that it communicates to its customers. |

|

REcB2 |

The firm’s decisions do not always account for market criteria. |

|

REcB3 |

The firm prioritises working with suppliers that ensure the quality, security and environmental friendliness of their products. |

|

REcB4 |

The firm obtains high customer satisfaction rates with regard to its quality, security and environmental friendliness. |

|

REcB5 |

The firm is actively committed to networks and programmes for service and products, promoting collaboration, joint promotional actions, and communication |

Results

A PLS model is analysed and interpreted in two steps. We assessed, firstly, the reliability and validity of the measurement model and, second, the structural model. Only when the quantification of the constructs has been proved as valid and reliable, will conclusions regarding the relationships among the constructs be drawn (Barclay et al., 1995).

Measurement model evaluation

Depending on the nature of the construct (reflective or formative), the evaluation of a measurement model differs. For constructs with reflective indicators (as happens in this research), individual item and construct reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity must be determined.

In order to verify enough level of individual item reliability, item loadings should be not less than 0.707. In our field, 30 items were considered correct, and 2 out of 32 indicators showed a loading value between 0.707 and 0.65. Therefore, we retained all of the items, due to the closeness of their loading values to the limit of 0.707. Finally, we employed 17 items to measure FROP and 15 items to measure FFSR (Table 2).

Table 2. Measurement model evaluation

|

Constructs and measures |

Loading |

Composite reliability |

Average variance extracted (AVE) |

|

FROP |

|||

|

ROS |

0.838 |

0.633 |

|

|

ROS1 |

0.7791 |

||

|

ROS2 |

0.7521 |

||

|

ROS3 |

0.8527 |

||

|

RMS |

0.903 |

0.756 |

|

|

RMS1 |

0.8567 |

||

|

RMS2 |

0.9135 |

||

|

RMS3 |

0.8371 |

||

|

RFRA |

0.906 |

0.710 |

|

|

RFRA1 |

0.9251 |

||

|

RFRA2 |

0.9482 |

||

|

RFRA3 |

0.7815 |

||

|

RFRA4 |

0.6893 |

||

|

P |

0.867 |

0.685 |

|

|

P1 |

0.8094 |

||

|

P2 |

0.8689 |

||

|

P3 |

0.8023 |

||

|

FSC |

0.974 |

0.903 |

|

|

FSC1 |

0.9708 |

||

|

FSC2 |

0.9712 |

||

|

FSC3 |

0.9409 |

||

|

FSC4 |

0.9180 |

||

|

FFSR |

|||

|

REB |

0.920 |

0.700 |

|

|

REB1 |

0.9200 |

||

|

REB2 |

0.6611 |

||

|

REB3 |

0.8717 |

||

|

REB4 |

0.8258 |

||

|

REB5 |

0.8795 |

||

|

SRB |

0.951 |

0.795 |

|

|

RSB1 |

0.8760 |

||

|

RSB2 |

0.8204 |

||

|

RSB3 |

0.8346 |

||

|

RSB4 |

0.9591 |

||

|

RSB5 |

0.9588 |

||

|

REcB |

0.983 |

0.843 |

|

|

REcB1 |

0.8413 |

||

|

REcB2 |

0.7468 |

||

|

REcB3 |

0.8965 |

||

|

REcB4 |

0.9881 |

||

|

REcB5 |

0.9151 |

||

The composite reliability is strong. Professionalism presented the lowest value (0.867), and Economically responsible behaviour, showed the highest value (0.983). The strength of the AVE was high for all of the constructs analysed; with values ranged from 0.633 (Responsible ownership succession) to 0.903 (Family social commitment) (Table 2)

Eventually, the discriminant validity (Table 3) was confirmed as all of the constructs share more variance with their own indicators than they share with the other constructs in the model.

5.2. Structural model evaluation

After guaranteeing the quality of the measurement model, the strength of the research hypotheses and the predictive power of the model, namely, the quality of the structural model was assessed. Therefore, a bootstrap method of analysis is used. Bootstrapping provides a T-value for each relationship of the model, and the R2 value of the endogenous construct provided by the PLS model is the measure of the predictive power of the model, that for an endogenous construct should be not less than 0.10. This value reflects the amount of variance in the construct that is explained by the model. Even if Falk and Miller (1992) argue that lower values of R2 could be statistically significant, such values would provide little information; thus, the predictive power of the hypotheses formulated with respect to the latent variable under analysis is low.

Influence of FROP on FFSR

Table 4 shows the path coefficients that were obtained, their degree of significance (which has been tested by means of bootstrapping techniques), and the contribution of each independent variable to the amount of variance explained for each endogenous construct. This contribution was calculated by multiplying the path coefficient linking the independent variable to the dependent variable by the correlation between the two constructs.

The results indicate that the expected responsible management succession, responsible financial resource allocation and professionalism are the FROPs that exert a significant influence on FFSR. As predicted, increased levels of responsible management succession, responsible financial resource allocation and responsible family firm relations positively affect the SR of FFs. Therefore, H3, H4, H5 are accepted, whereas hypotheses H2 and H6 are rejected.

The total amount of variance that was explained for the three types of SR is high because these values are substantially above the 10% quality threshold that was advocated by Falk and Miller (1992). In fact, the amount of variance that was explained is nearly 36.49% for Environmentally responsible behaviour and is twice that for Economically responsible behaviour (70.93%). The amount of variance that was explained for Socially responsible behaviour is 56.04%.

6. Discussion

This study reveals the relevance of the FROP as a driver that influences SR practices in family SMEs; thus, we confirm the main hypothesis that FROP is positively related to the presence of SR practices in family SMEs. The common absence of ethical codes and even governance structures in family firms renders informal methods, such as the role modelling of expected behaviours, as a critical method of promoting ethical behaviour and SR in such a firm (Adams et al., 1996). The direct relationship between owners and managers can be viewed as a source of socially responsible practices or, on the contrary, as justification for opportunistic behaviour. When family owners act as good owners by behaving professionally, avoiding family practices that are derived from their power status and defending their firm’s competitiveness in various ways, this responsible behaviour is transferred to their businesses in terms of SR. This relationship implies that when FROP is limited, a manager is more likely to follow an agency perspective and thus behave opportunistically and discourage socially responsible practices in his/her family SME. In this study, FROP can be associated with a code of ethics but is primarily available to families as a model of ethical behaviour. In this sense and following Sorenson et al. (2009), the measurement of FROP includes three of the elements of innate morality that were suggested by Haidt and Joseph (2007): concern for others, fairness, and the establishment of order and control in a business.

Second, among the various antecedents of FROP, there are three primary drivers of SR in family SMEs: responsible management succession, responsible financial resource allocation and professionalism. In contrast, responsible ownership succession and family social commitment are not significantly relevant factors of SR in family SMEs. Following the literature on pro-social organisational behaviours, we can distinguish between in-role behaviours and extra-role behaviours (Berent-Braun and Uhlaner, 2012). In-role behaviours are expected behaviours that form part of one´s role obligation. Extra-role behaviours surpass normal expectations (Brief and Motowidlo, 1986). According to the definition of in-role and extra-role behaviours, in-role behaviours motivate SR behaviour in family SMEs. Questions related to ownership issues, such as ownership succession or family vision of SR, are considered extra-role behaviours and do not significantly influence the SR behaviour of family SMEs.

This can be understood from the practical view of SR in family SMEs. When ownership issues are consistent with corporate governance practices, and a family is not viewed as an abusing stakeholder—on the contrary, its decisions are pro-firm and pro-social—family SMEs are concerned about SR. This can be understood because the behaviour of CEOs will be more ethical and socially responsible if they consider organisational effectiveness to be vital (Singhapakdi et al., 2001; Godos-Diez et al., 2011). The desire to assist in ensuring the competitiveness of their firms creates a stewardship relation between family owners and family managers in which the primary risk becomes the abusive behaviour of the main stakeholders (i.e., the family owners).

We identify two main implications of the study. First, and based on the assumption that the influence of the ethical focus on firm performance has been challenged by O´Boyle et al. (2010), SR practices can be considered relevant for survival in family SMEs. Thus, families are concerned about acting as responsible owners to encourage the steward perspective in managers and to promote and support SR in such firms. This study suggests that developing FROP through responsible management succession, responsible financial resource allocation and professionalism may positively affect SR in family SMEs.

Second, public policy can play an important role in providing families with additional incentives to act as good owners. For example, policy initiatives can provide families with economic stability. Income and inheritance tax policies could recognise the contributions of family businesses to both society and the economy. Family firms both provide jobs to their communities and assist in promoting ethical behaviour, which aids in building our society.

Conclusion

This study offers several contributions to the family business literature. The results assist in clarifying the components of FROP and the antecedents of SR for family SMEs. This study reveals the relevance of the FROP in explaining how family firm owners influence SR. Moreover, this research proposes and obtains support for a model that illustrates the relationships among responsible ownership succession, responsible management succession, responsible financial resource allocation, professionalism, family social commitment and the SR of family firms.

These results suggest several potentially fruitful areas for research. First, the analysis of FROP concerning the heterogeneity of family firms (Deniz and Cabrera, 2005). These differences can be related to “familiness” (Habbershon and Williams, 1999; Habbershon et al., 2003), which refers to the idiosyncratic resources and capabilities that are available in family firms that emerge from family involvement and interactions (Chrisman et al., 2003a; Habbershon and Williams, 1999). For this reason, future research could pursue a common perspective using the social capital model of familiness (Pearson et al., 2008).

Second, family businesses may suffer from the same ethical hazards that other businesses encounter. Goodpaster (2007) indicates that unethical conduct frequently occurs when groups become fixated on certain goals without regard for consequences, rationalise their behaviour based on these goals and repeat the process ‘until the protesting consciences of the participants become detached, anesthetized, and silenced’ (p. 3). Business owners may be dominant by imposing their will on other members of the family, or they may exclude the family from business discussions. Thus, FROP cannot be assumed as given in family business. Collaborative dialogue (Sorenson et al., 2009), fair processes (Van den Heyden et al. (2005), and social exchange theory in general can be assessed according to the recommendations of Long (2011).

Third, the stability of FROP depends on family system dynamics and stability. Salvato and Melin (2008) employ family social capital, which is understood as the processes through which family firms access and recombine resources to match the evolving needs of their business activities over time and may assist in understanding the creation of value across generations. This approach could be interesting to adapt to the dynamics of FROP (Aragón-Amonarriz et al., 2019).

Finally, the results of this study lead us to additional questions such as, are the antecedents of FFSR the same in family firms with a non-family CEO? Or, in a firm with a non-family CEO, is responsible ownership succession an antecedent of FFSR? Is FROP homogeneous among family firms? If it is not homogeneous, is it always an antecedent of FFSR? Is it in a similar way? What is the dynamism of FROP? What conditions are necessary to sustain FROP over time?

Despite the presence of hypothesised relationships unveiled, limited research has addressed these relationships, and further empirical inquiry is needed. Given this context, we highlight several limitations of the current research. First, our study observes the family businesses located in a Spanish region, and it could imply relevant cultural bias in the influence identified between FROP and SR. Differences in certain critical topics in different geographical areas, such as families constitution and role, can alter these conclusions (O´Boyle et al., 2010). Second, although confidentiality and anonymity were ensured in the survey, the perception and social expectation bias involved in the answers were unavoidable, and therefore, it should be recommended to triangulate the responses given by the CEO with other stakeholders in future research. In this sense, some constructs such as the FROP or FFSR could be complemented with different family members could be included in the study. Finally, future research could use longitudinal designs and ratings by multiple people to assess changes in FROP and FFSR levels over time.

References

Adams, J. S., Taschian, A. and Shore, T. H. (1996). Ethics in family and non-family owned firms: An exploratory study. Family Business Review, 9(2), 157-170.

Agle, B. R., Mitchell, R. K. and Sonnenfeld, J.A. (1999). Who matters to CEOS? An investigation of stakeholder attributes and salience, corporate performance, and CEO values, Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 507-525.

Akhmedova, A., Cavallotti, R., and Marimon, F. (2019). Barriers or motivation? Career progress in the family firm: daughters’ perspective. European Journal of Family Business, 8(2), 103-115.

Alvesson, M. and Willmott, H. (1992). On the idea of emancipation in management and organization studies, academy of Management Review, 17(3), 432-464.

Aragón-Amonarriz, C., Arredondo, A. M., and Iturrioz-Landart, C. (2019). How can responsible family ownership be sustained across generations? A family social capital approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(1), 161-185.

Aragón Amonarriz, C., and Iturrioz Landart, C. (2016). Responsible family ownership in small‐and medium‐sized family enterprises: an exploratory study. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(1), 75-93.

Aronoff, C. E. and Ward, J.L. (2002). Family Business Ownership: How to Be an Effective Shareholder, Family Enterprise Publishers, Marietta, GA.

Aronoff, C. E. and Ward, J. L. (1992). Is it “worth it” to the family? Family Business Review, 80(8), 208-222.

Bagby, D. R. (2004). Enhancing Succession research in the family firm: A commentary on “Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 28(4), 329-333.

Barclay, D., Higgings, C., and Thompson, R. (1995). The Partial Least Square (PLS) approach to causal modelling: personal computer adoption and use as an illustration, Technology Studies, Special Issue on Research Methodology 2(2), 285-309.

Berent-Braum, M. M. and Uhlaner, L. M. (2012). Responsible ownership behaviors and financial performance in family owned businesses. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(1), 20-38.

Bingham, J .B, Dyer, W. G. Jr, Smith, I., and Adams, G.L. (2011). A stakeholder identity orientation approach to corporate social performance in family firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 99, 565–585.

Bocatto, E., Gispert, C., and Rialp, J. (2010). Family-owned business succession: The influence of pre-performance in the nomination of family and nonfamily members: Evidence from Spanish Firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(4), 497–523.

Brief, A. P. and Motowidlo, S. J. (1986). Prosocial organizational behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 11(4), 710–725.

Brockhaus, R. H. (2004). Family business succession: Suggestions for future research. Family Business Review, 17(2), 165-177.

Cabeza-García, L., Sacristán-Navarro, M., and Gómez-Ansón, S. (2017). Family involvement and corporate social responsibility disclosure. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(2), 109-122.

Campopiano, G., and De Massis, A. (2015). Corporate social responsibility reporting: A content analysis in family and non-family firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(3), 511-534.

Castejón, P. J. M., and López, B. A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility in family SMEs: A comparative study. European Journal of Family Business, 6(1), 21-31.

Chrisman, J., Chua, J. H., Kellermanns, F. and Chang, E. (2007). Are family managers agents or stewards? An exploratory study in privately held family firms. Journal of Business Research, 60(11), 1030–1038.

Chrisman, J. Chua, J. H., and Litz, R. (2003b). Extending the theoretical horizons of family business research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 331-38.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H. and Zahra, S. A. (2003a). Creating wealth in family firms through managing resources: comments and extensions. Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, summer, 359-365.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J. and Sharma, P (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 23(4) 19–39.

Cook J., and Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfilment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53, 39-52.

Davis, J. H., Allen, M. R. and Hayes, H. D. (2010). Is blood thicker than water? A study of stewardship perceptions in family business. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(6) 1093-1116.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., and Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–48.

Debicki, B. J., Matheme, III, C. F, Kellermans, F. W., and Chrisman, J. J. (2009). Family business research in the new millennium: An overview of the who, the where, the what, and the why. Family Business Review, 22(2) 151-66.

Deniz, D. and Cabrera, M. K. (2005). Corporate social responsibility and family business in Spain. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(1), 59–71.

Desai, A. B. and Rittenburg, T. (1997). Global ethics: an integrative framework for MNEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(8), 791-800.

Distelberg, B., and Sorenson, R. L. (2009). Updating systems concepts in family businesses: A focus on values, resource flows, and adaptability. Family Business Review, 22(1), 65-81.

Dyer, W. G. Jr., and Whetten, D. A. (2006). Family firms and social responsibility: Preliminary evidence from the S&P 500. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 30(6), 785-802.

ESADE (2007). Marco catalán de la responsabilidad social de la empresa en las pymes. Instituto de Innovación Social, ESADE Business School, Barcelona, España.

Falk, R., and Miller, N. (1992). A Primer for Soft Modelling, Akron, The University of Akron.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management. A Stakeholder Approach, Pitman/Ballinger, Harper Collins, Boston.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press. Chicago.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York TimesMagazine.

Frishkoff, P. A. (1994). Succession need not tear a family apart. Best’s Review, 95(8), 70-73.

Gallo, M. Á. (1998). La sucesión en la Empresa Familiar. Servicio de Estudios “la Caixa”.

Gallo, M. Á. (2004). The family business and its social responsibilities. Family Business Review, 17(2), 135-149.

García, L. C., Navarro, M. S., and Ansón, S. G. (2014). Propiedad familiar, control y efecto generación y RSC. European Journal Of Family Business, 4(1), 9-20.

Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., Hampton, M. M., and Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Gibson, K. (2000). The Moral basis of stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 6(3), 245–257.

Godos-Díez, J. L., Fernández-Gago, R., and Martínez-Campillo, A. (2011). How important are ceos to csr practices? An analysis of the mediating effect of the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 531–548

Goldberg, S. D., and Woodridge, B. (1993). Self-Confidence and managerial autonomy: successor characteristics critical to succession in family firms. Family Business Review, 6(1), 55-73.

Goodpaster, K. E. (2007). Conscience and corporate culture. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Guidice, R. and Mero, N. (2007). Governing joint ventures: Tension among principals’ dominant logic on human motivation and behavior’. Journal of Management and Governance, 11(3), 261–283.

Habbershon, T. G. and Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1-15.

Habbershon, T. G., Williams, M. L. and MacMillan, I. C. (2003). A Unified Systems Perspective of Family Firm Performance, Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 451– 465.

Haidt, J. and Joseph, C. (2007). The moral mind: How five sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In Carruthers, P. Laurence, S. and Stich, S. (Eds.) The innate mind: Future and foundations (367-392), New York: Oxford University Press.

Hall, A. and Nordqvist, M. (2008). Professional management in family businesses: Toward an extended understanding. Family Business Review, 21(1), 52-69.

Hammann, E. M., Habish, A. and Pechlaner, H. (2009). Values that create value: socially responsible business practices in SMEs – empirical evidence from German companies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 18(1), 37-51.

Handler, W. (1994). Succession in family business: A review of the research. Family Business Review, 7(2), 133–157.

Hemingway, C. A., and Maclagan, P. W. (2004). Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 50(1), 33–44.

Hernaández, M. (2008). Promoting stewardship behavior in organizations: A leadership model. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(1), 121–128.

Igalens, J. and Gond, J. P. (2005). Measuring corporate social performance in France: A critical and empirical analysis of ARESE data. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(2) 131-148.

Jones, T. M. (1995). Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Academy of Management Review, 20, 404-437.

Kouzes, J. M. and Posner, B. Z. (1993). Credibility: how leaders gain and lose it, and why people demand It. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Laguir, I., Laguir, L., and Elbaz, J. (2016). Are family small‐and medium‐sized enterprises more socially responsible than nonfamily small‐and medium‐sized enterprises?. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 23(6), 386-398.

Lambrecht, J., and Uhlaner, L . M. (2005). Responsible Ownership of the Family Business: State-of-the-art, The Family Business Network International, EHSAL, Brussels.

Liu, M., Shi, Y., Wilson, C., and Wu, Z. (2017). Does family involvement explain why corporate social responsibility affects earnings management?, Journal of Business Research, 75, 8-16.

Long, R. (2011). Commentary: Social exchange in building, modeling, and managing family social capital. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(6), 1229–1234.

Maclagan, P. (1999). Corporate social responsibility as a participative process, Business Ethics: A European Review, 8(1), 43–49.

Madison, K., Holt, D. T., Kellermanns, F. W., and Ranft, A. L. (2016). Viewing family firm behavior and governance through the lens of agency and stewardship theories. Family Business Review, 29(1), 65-93.

Madueño, J. H., Jorge, M. L., Sancho, M. P. L., and Martínez-Martínez, D. (2014). Motivaciones hacia la eesponsabilidad social en las Pymes familiares. European Journal Of Family Business, 4(1), 21-44.

Manville, B., and Ober, J. (2003). A company of citizens: what the world’s first democracy teaches leaders about creating great organizations, Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA.

Martínez-Ferrero, J., Rodríguez-Ariza, L., and García-Sánchez, I. M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility as an entrenchment strategy, with a focus on the implications of family ownership. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 760-770.

Miller, D. and Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Mishra, S., and Suar, D. (2010). Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies?. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 571-601.

Morck, R., and Yeung, B. (2003). Agency problems in large family business groups. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 27(4), 367–382.

Mustakallio, M., Autio, E. and Zahra, S.A. (2002). Relational and contractual governance in family firms: Effects on strategic decision making. Family Business Review, 15(3), 205–222.

Narvaiza, L., Ibañez, A., Aragón, C., and Iturrioz, C. (2009). Social responsibility in SME: a proposal for measuring social responsible activities at SME in Aras, G.; Crowther, D.; & Vettori, S. (eds.): Corporate Social Responsibility in SMEs, 61-86, SRRNet, Leicester, UK.

Neubauer, F., and Lank, A. G. (1998). The family business: Its governance for sustainability, London: MacMillan Press Ltd.

Niehm, L. Swinney, J., and Miller, N. J. (2008). Community social responsibility and its consequences for family business performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(3), 331-350.

Oeyono, J., Samy, M., and Bampton, R. (2011). An examination of corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Journal of Global Responsibility 2(1), 100-112.

O’Boyle, Jr., E. H., Rutherford M. W., and Pollack, J. M. (2010). Examining the relation between ethical focus and financial performance in family firms: An exploratory study, Family Business Review, 20(10), 1-17.

Pearson, A. W., Carr, J. C., and Shaw, J. C. (2008). Toward a theory of familiness: A social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(6), 949-969.

Post, J. E. (1993). The greening of the Boston Park Plaza Hotel. Family Business Review, 6(2), 131–48.

Quazi, A. M. (2003). Identifying the determinants of corporate managers perceived social obligations. Management Decision, 41(9), 822–831.

Quazi, A. M., and O’Brien, D. (2000). An empirical test of a cross-national model of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 25, 33-51

Salvato, C. and Melin, L. (2008). Creating value across generations in family-controlled businesses: the role of family social capital. Family Business Review, 11(3), 259-276.

Sharma, P. (2004). An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future. Family Business Review, 27, 1-36.

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., Pablo, A. and Chua, J. H. (2001). Determinants of Initial satisfaction with the succession process in family firms: A conceptual model. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 25(3), 1–19.

Singhapakdi, A., Karande, K., Rao, C. P. and Vitell, S. J. (2001). How important are ethics and social responsibility? A multinational study of marketing professionals. European Journal of Marketing, 35(1/2), 133–152.

Sirmon, D. G., and Hitt, M. A. (2003). Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 27, 339–358.

Sorenson, R. L., Goodpaster, K. E., Hedberg, P. R. and Yu, A. (2009). The family point of Vview, family social capital, and firm performance: An exploratory test, Family Business Review, 22(3), 239-253.

Spence, L. J. (2016). Small business social responsibility: Expanding core CSR theory. Business and Society, 55(1), 23-55.

Swanson, D. L. (2008). Top managers as drivers for corporate social responsibility’, in Crane, A. et al. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Oxford University Press, Norfolk, 227–248.

Swanson, D. L. (1995). Addressing a theoretical problem by reorienting the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review 20(1), 43-64.

Thompson, J. and Smith, H. (1991). Social responsibility and small business: Suggestions for research. Journal of Small Business Management, 29(1), 30-44.

Uhlaner, L. M. and Berent, M. M. (2008). Entrepreneurship and ownership in the closely-held firm, in Burggraaf, W., Flören, R. and Kunst, J. (eds.) The Entrepreneur and The Entrepreneurship Cycle, 326-341. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Uhlaner, L. M., Wright, M. and Huse, M. (2007). Private firms and corporate governance: an integrated economic and management perspective. Small Business Economics, 29(3), 225-241.

Van der Heyden, L., Blondel, C. and Carlock, R.S. (2005). Fair process: Striving for justice in family business. Family Business Review, 18(1), 1-21.

Van Marrewijk, M. (2003). Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics, 44, 95-105.

Vitell, S. J. and Ramos-Hidalgo, E. (2006). The impact of corporate ethical values and enforcement of ethical codes on the perceived importance of ethics in business: A comparison of U.S. and Spanish managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(1), 31–43.

Ward J. L. (2004). Perpetuating the Family business, 50 lessons learned from long-lasting, successful families in business, Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Ward, J. L. (1997). Growing the family business: Special challenges and best practices. Family Business Review, 10(4), 323-337.

Wasserman, N. (2006). Stewards, agents and the founder discount: Executive Compensation in new ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 960–976.

Westhead, P., and Howorth, C. (2006). Ownership and management issues associated with family firm performance and company objectives. Family Business Review, 19(4), 301-16.

Zellweger, T. M., and Nason, R. S. (2008). A stakeholder perspective on family firm performance. Family Business Review, 21(3), 203–216.

Table 3. Measurement model evaluation: discriminant validity

|

ROS |

RMS |

RFRA |

P |

FSC |

REB |

RSB |

REcB |

|

|

ROS |

0.796 |

|||||||

|

RMS |

0.786 |

0.869 |

||||||

|

RFRA |

0.598 |

0.788 |

0.843 |

|||||

|

P |

0.722 |

0.637 |

0.692 |

0.828 |

||||

|

FSC |

0.5 |

0.429 |

0.412 |

0.435 |

0.950 |

|||

|

REB |

0.417 |

0.570 |

0.536 |

0.317 |

0.197 |

0.837 |

||

|

RSB |

0.499 |

0.683 |

0.702 |

0.420 |

0.360 |

0.768 |

0.987 |

|

|

REcB |

0.567 |

0.782 |

0.829 |

0.517 |

0.406 |

0.685 |

0.873 |

0.918 |

Notes: The diagonal elements (values in parentheses) are the square root of the variance shared between the constructs and their measures relative to the amount that results from measurement error (AVE). The off-diagonal elements are the correlations among the constructs. For discriminant validity, the diagonal elements should be larger than the off-diagonal elements.

Table 4. Structural model evaluation: the influence of FROP on FFSR

|

Endogenous construct |

Parameter |

FROP |

Total amount of variance explained (R2) |

|

FFSR |

Path |

0.865*** |

|

|

Correlation |

0.865 |

||

|

Contribution to R2 |

0.748 |

0.748 |

***p<0.001 (based on t499, one-tailed test)

The results shown in Table 4 show that FROP plays a significant effect on FFSR; therefore, H1 is supported. Indeed, the total amount of variance explained by responsible family behaviour is high and represents almost 75% of the variance of the endogenous construct.

Table 5. Structural model evaluation: the influence of FROP on FFSR

|

ROS |

RMS |

RFRA |

P |

FSC |

Total amount of variance explained (R2) |

||

|

REB |

Path |

0.083 |

0.388* |

0.347* |

-0.201* |

-0.067 |

|

|

Correlation |

0.417 |

0.570 |

0.536 |

0.317 |

0.197 |

||

|

Contribution to R2 |

3.46% |

22.12% |

18.60% |

-6.37% |

-1.32% |

36.49% |

|

|

RSB |

Path |

0.033 |

0.35* |

0.533** |

-0.227* |

0.072 |

|

|

Correlation |

0.499 |

0.683 |

0.702 |

0.420 |

0.360 |

||

|

Contribution to R2 |

1.65% |

23.91% |

37.42% |

-9.53% |

2.59% |

56.04% |

|

|

REcB |

Path |

-0.08 |

0.373** |

0.643** |

-0.188* |

0.067 |

|

|

Correlation |

0.567 |

0.782 |

0.829 |

0.517 |

0.406 |

||

|

Contribution to R2 |

-4.54% |

29.17% |

53.30% |

-9.72% |

2.72% |

70.93% |

***p<0.001, **P<0.05, and * p<0.1 (based on t499, one-tailed test)