European Journal of Family Business (2020) 10, 35-41

Family business in the health care sector: Past and future

Francisco Reyes-Santíasa, Elena Rivo-Lópeza*, Mónica Villanueva-Villara

a University of Vigo

Received 2019-07-23; accepted 2020-01-21

JEL CLASSIFICATION

G32, I10, M10

KEYWORDS

Family business, socioemotional wealth, private health care, performance, survival

CÓDIGOS JEL

G32, I10, M10

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar, riqueza socioemocional, sanidad privada, rentabilidad, supervivencia

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i1.6683

2444-877X/ © 2020 European Journal of Family Business. Published by Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-SA license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).

*Corresponding author

E-mail: rivo@uvigo.es

Abstract The relevance of family businesses in the world economy has led researchers to study them in various fields and from various perspectives. However, the role played by family businesses in the private health care sector has hardly been analyzed. The objective of this research was to focus on the historical evolution of the family business in the field of private health, attempting to determine the variation in its contribution to the sector during 1995–2018. For this purpose, we constructed a database with the existing private hospitals in Spain, classifying them according to family and non-family ownership for the years 1995 and 2018 and performing a cross-sectional analysis. We observed an almost 60% survival rate for family businesses. We propose implementing the methodology of the case study for future research.

La empresa familiar en el sector sanitario: Evolución y perspectivas futuras

Resumen La relevancia de la empresa familiar en la economía mundial la ha llevado a ser objeto de estudio desde diversos ámbitos y perspectivas. Sin embargo, el papel que juega la empresa familiar en el sector sanitario privado apenas ha sido analizado. El objetivo de este trabajo de investigación se centra en el estudio de la evolución histórica de la empresa familiar en el ámbito de la sanidad privada, intentando conocer la variación de la contribución de la misma al sector durante el periodo 1995-2018. Con este propósito, se construye una base de datos con los hospitales privados existentes en España, clasificándolos en familiares y no familiares para los años 1995 y 2018, realizando un análisis de corte transversal. Se observa un nivel de supervivencia de las empresas familiares de casi un 60%. Se propone implementar la metodología del estudio de casos en investigación futuras.

Introduction

In the ‘90s in Spain, the ownership of private clinics was distributed mainly between families (Dexeus, Barraquer, Domínguez, etc.) and groups of doctors, who were associated with the objective of having a place to work professionally and to generate income (case Povisa, Cosaga, La Rosaleda, etc.). Over time, the picture of the situation has changed a lot. At present, some family clinics have closed and others sold to multinationals, insurers, other family groups, and so on. The novelty of this article is that no investigation has been carried out so far, perhaps due in large part to the difficulty of access to information. The Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare of the Spanish government owns the data of the private entities existing in Spain, but these are not classified according to their ownership (family firm or not), a fundamental issue for our study.

Succession is a critical process in family businesses (Ibrahim et al., 2001; Umans et al., 2019). Depending on how this process is resolved, the company will either survive the next generation in the hands of the same family or be sold or closed for lack of a successor or for not being profitable, regardless of the economic activity developed. The family health sector is no stranger to inheritance problems that may arise due to its family nature. The lack of a successor can lead to the sale or even closing of a company. On the contrary, the long-term vision of family entrepreneurs can lead to expanding activities, differentiating by specialization, or acquiring other companies in the sector. From a theoretical point of view, the socioemotional wealth (SEW) perspective can help us understand this process.

SEW refers to the “non-financial aspects of the company that meet the affective needs of the family” (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007, p. 106). During the last decade, the preservation of SEW has become a good explanation for the economic behavior and dynastic intentions of family-owned businesses (Cleary, Quinn, & Moreno, 2018; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Morgan & Gomez-Mejia, 2014; Nason, Carney, Le Breton-Miller, & Miller, 2019). Maintaining family identity, strong ties between family members, long-term vision, and interest in preserving and transmitting the legacy to the next generation are dimensions of SEW that differentiate family businesses from those that are not. According to Le Breton-Miller and Miller (2009), strong family ties allow the right conditions for ethical behavior within the company. This circumstance also has a positive effect on the reputation of the company (Sorenson et al., 2009). The desire to maintain family identity and reputation for generations, as well as the transmission of knowledge, is a distinctive factor of family businesses, especially within the health sector.

The objective of this paper was to build a database that classifies private Spanish hospitals according to their family ownership or not, for the years 1995 and 2018 (1995 being the first year available in the ministry’s database). We sought to answer questions such as the following: How many hospitals were family owned in 1995? How many were in 2018? How many existing family hospitals closed in 1995? How many changed ownership from 1995 to 2018? Are family-owned hospitals more profitable? What are the future perspectives of the family business in the market health care sector? These are all issues of a descriptive nature that will allow us to propose future lines of research.

To achieve this objective, in the next section, we will talk about the preservation of SEW, especially the transmission of the legacy of knowledge and reputation in family businesses from the SEW perspective. Subsequently, we will explain the methodology used and the way in which the database was built. We will present the results and main conclusions of the work, along with future lines of research in this area.

Literature review

For family businesses, wealth generation is not usually the only driving force behind their behavior. In addition to pursuing financial objectives, family businesses aim to meet their nonfinancial needs, including their social and emotional needs (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). In fact, previous researchers found that SEW is an important reference point for decision-making in family businesses and differentiates these companies from non-family businesses (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). SEW covers “the non-financial aspects of the company that meet the emotional needs of the family” (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007, p. 106), such as family identity, the family’s emotional bond, and the continuity of the family dynasty (Berrone, Cruz, & Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Hauck, Suess-Reyes, Beck, Prügl, & Frank, 2016). From a succession perspective, one of the predominant dimensions of SEW is the renewal of family ties through dynastic succession. This intention of transgenerational succession of the company is defined as the intention to transfer the business to future family generations (Berrone et al., 2012; Hauck et al., 2016). It has been argued that this dimension is fundamental to explain the attitude of a family business toward the selection of a successor and the design of the succession process (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011; Minichilli et al., 2014). Succession is a critical process in family businesses (Ibrahim et al., 2001). To conclude it successfully, family businesses need to plan this process (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004; Sharma et al., 2003). Although there are clear advantages in succession planning, family businesses often postpone it, which may harm the future of the family business (Astrachan and Kolenko, 1994). Recent research on family businesses suggests that the preservation of SEW can serve as an engine for succession planning in a family business.

The commitment and motivation to preserve and perpetuate SEW is a characteristic of many family businesses (Berrone et al., 2012; Gómez-

Mejía et al., 2011; Zellweger et al., 2012). The main logic of SEW is that family businesses often have multiple objectives, not merely financial ones. That is, they give relevance to noneconomic aspects related to emotional issues, such as the perpetuation of the family legacy (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007, 2011) or the reputational factor (Berrone et al., 2010; Deephouse and Jaskewicz, 2013; Dyer and Whetten, 2006; Zellweger et al., 2012). Therefore, family business managers who value SEW are more likely to make long-term strategic decisions that benefit future generations, rather than decisions that only serve their own short-term interests (Strike et al., 2015). Investigation of the succession process indicated that the characteristic of SEW that prevails is the intention of transgenerational succession (Chua et al., 2003; Zellweger et al., 2012) or, expressed differently, the renewal of family ties in the company through dynastic succession (Berrone et al., 2012; Hauck et al., 2016). The legacy of the reputational factor is also important in the process of transfer of values. Reputation is the consideration, opinion, or esteem toward a company perceived by the different interest groups. It indicates how much different stakeholders admire and trust a company in relation to their expectations and compared with other companies (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013). Recent studies suggest that a favorable reputation of the family business may be an important objective linked to the maintenance of SEW (Berrone et al., 2010).

In the health sector, we consider that preserving SEW is very relevant for the survival of the company. The transmission of knowledge and the maintenance of the business and family reputation throughout the generations can be key in this sector.

Methodology

For the preparation of the sample, we used as a starting point the database of the Ministry of Health, Consumption and Welfare of the Government of Spain from 1995 to 2018, identifying 254 privately owned hospitals in 1995. Subsequently, we proceeded to classification of family and non-family businesses, based on their property. This classification was the most complex and laborious part of this research. In the database of the Ministry, there was no information that allowed us to differentiate between family and non-family hospitals. We turned to the SABI (Iberian Balance Analysis System) database for more information. We carried out the classification of family and non-family businesses according to the criteria established in the study published by Corona and Del Sol (2016).

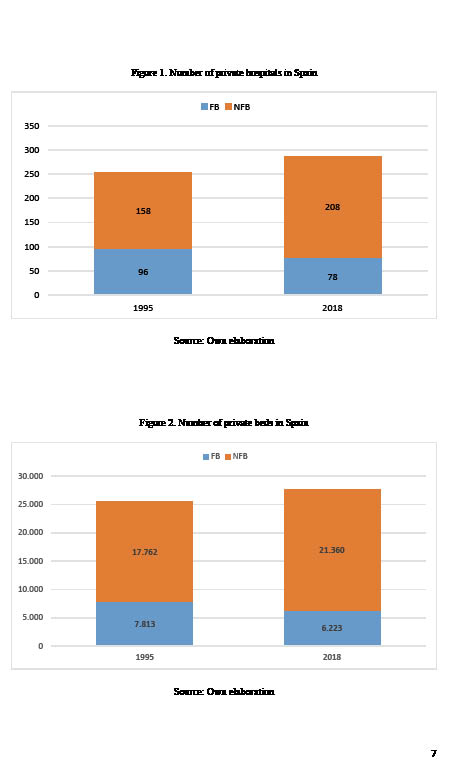

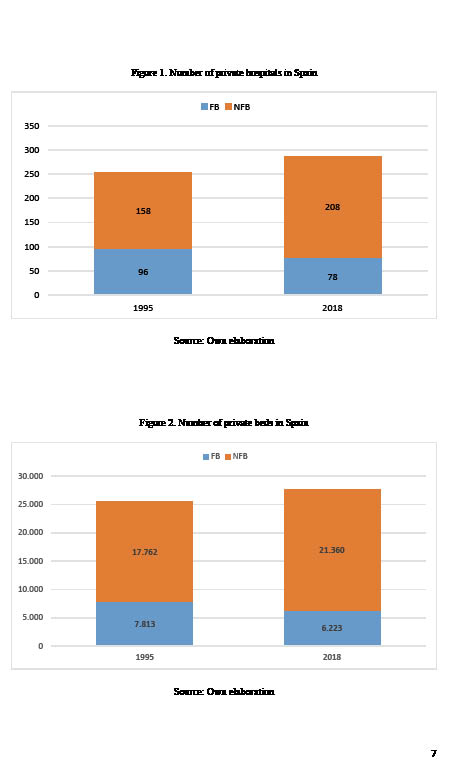

However, this methodology is not perfect either. In the aforementioned database, there is information about the current owners, when the company subsisted in 2018, but not when it disappeared in previous years. In addition, it does not provide information on the previous property, indicating only that there was a change of ownership. Consequently, we had to resort to secondary data sources, such as publications in local press about the closing of the name of the company in particular or web pages on which the history of the company is provided. Given this difficulty, for this work, we performed a cross-sectional analysis, classifying hospitals according to their family character or not, at two different times, in 1995 and 2018. We studied family hospitals existing in 1995 (a total of 96) and in 2018 (a total of 78). We used the number of existing beds as a measure of clinic size (Martín and Ortega-Díaz, 2016).

Evolution of the private health sector in Spain

Based on the data published in the report of the Institute for Health Development and Integration (2019), Spanish private health expenditure reached 28,562 million euros in 2015 (2.7% of GDP). In 2015, private hospitals carried out 29% (1.5 million) of surgical interventions, recorded 23% (1.2 million) of discharges, and treated 23% (6.6 million) of emergencies in the whole national territory.

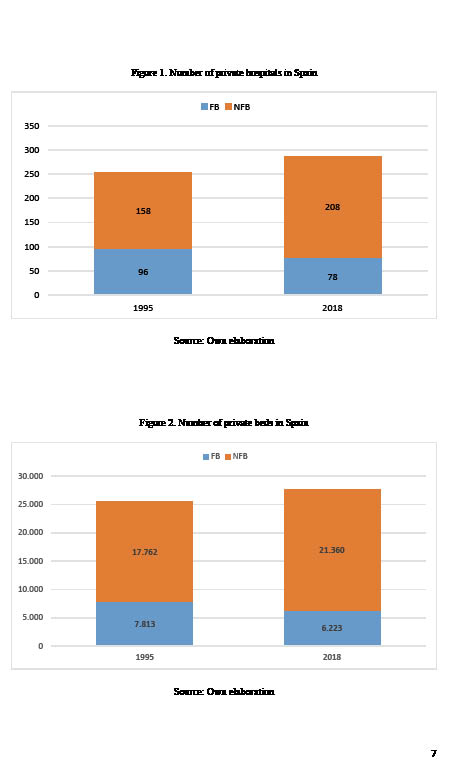

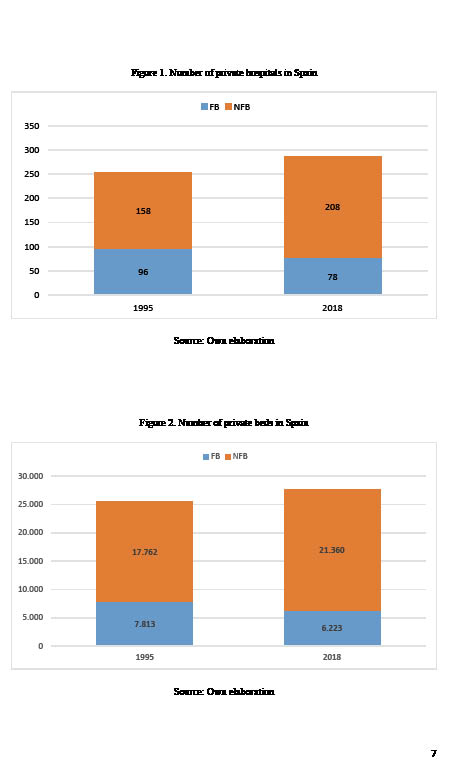

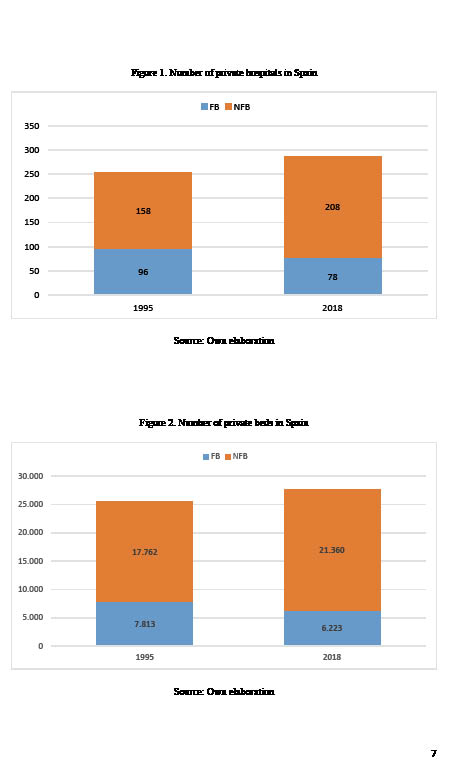

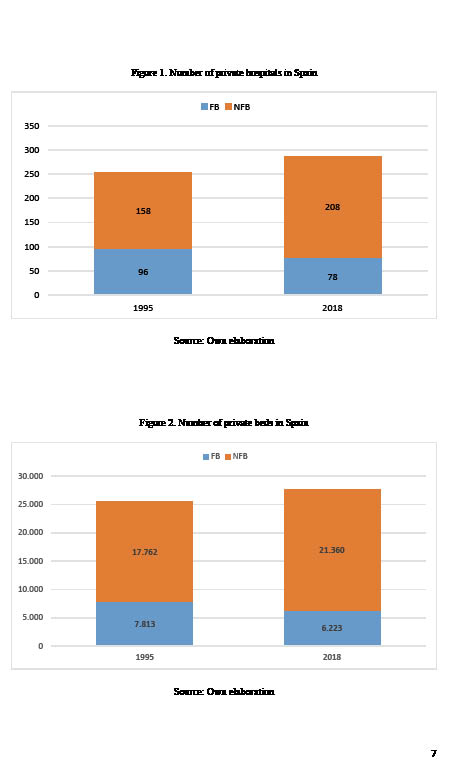

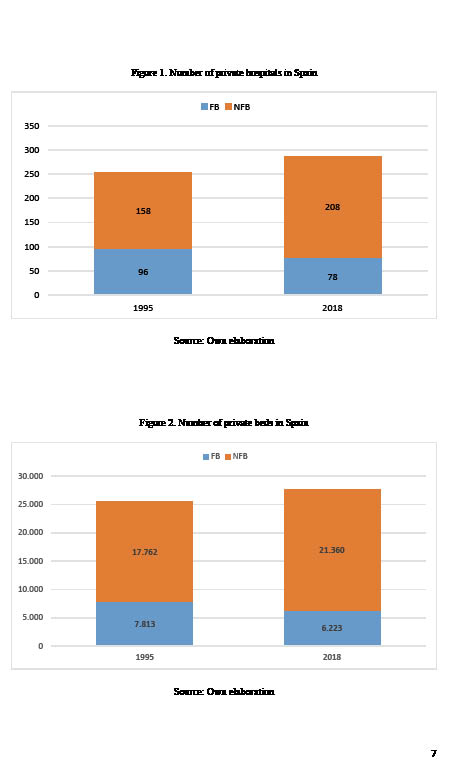

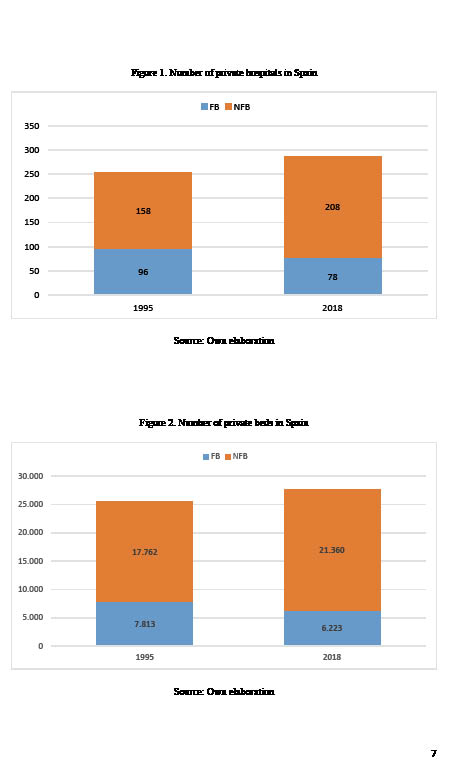

In 2018, the private hospital sector had a total of 467 hospitals in Spain, representing 51% of the total of the hospital centers in the country, with a provision of 51,557 beds, which accounted for 32% of the total beds existing. According to our study, in 1995, private family-owned hospitals in Spain totaled 96 (38% of all hospitals), with 7,813 (31%) beds. In 2018, there were 78 family businesses (27% of the total), providing 6,223 beds (23%; see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Number of private hospitals in Spain

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 2. Number of private beds in Spain

Source: Own elaboration

Analysis of the proportion of hospitals and private family beds over the total number of hospitals and beds indicated significant differences between autonomous communities. In 1995, Catalonia, Galicia, and Andalusia had the highest percentage of private family hospitals over the total number of hospitals, with 8%, 6%, and 6%, respectively (Figure 3). It must be taken into account that in Spain, health management is transferred to the autonomous communities, where the policies and the way of managing can be different. In 2018, the situation changed (Figure 4). The Andalusian community led in the ranking of private family hospitals (7%), followed by Catalonia (4%), Galicia (3%), and Madrid (3%).

Figure 3. Number of private hospitals by autonomous community (1995)

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 4. Number of private hospitals by autonomous community (2018)

Source: Own elaboration

To analyze the survival of family businesses in the health sector, we prepared Figure 5. This shows the evolution of private hospitals closed from 1995 to 2018. The number of family hospitals closed during the period analyzed is less than that of the non-family hospitals; in turn, their size is also smaller.

Figure 5. Number of private hospitals closed

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 6 shows the number of private hospitals created in the same period, where we can also see that family hospitals were established but in smaller numbers than non-family ones. Consequently, it seems clear from the analyzed data that the survival of family businesses is greater than non-family businesses. The long-term vision, transmission of the legacy of knowledge and values, and maintenance of family and business reputation are dimensions of SEW that explain this situation.

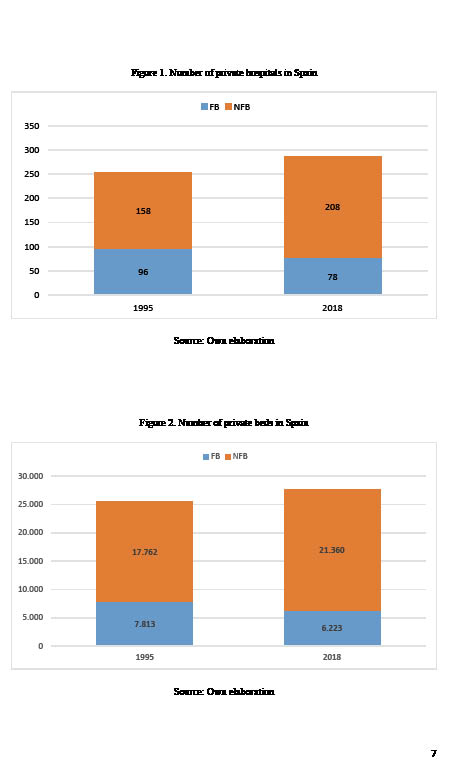

In Figure 7, we can see that in 2018, of the 78 private family clinics, 46 (59%) already existed in 1995, and 6 (8%) changed from non-family to family ownership. A generational continuity of 60% in family hospitals is very high compared to the usual figures in the family business (33% survive the second generation, further reducing the percentages in later generations). In the family hospital sector, it seems that the transmission of the tangible and intangible legacy has a very important influence that increases its survival.

From the SEW perspective, the creation and maintenance of a good reputation may involve short-term costs. However, in the long term, these costs would benefit the reputation and contribute to the prosperity and longevity of the company. In general, good reputation attracts quality resources, with a positive effect on all stakeholders, and very positive consequences for the performance of the family business (Berrone et al., 2010; Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007).

Figure 6. Number of private hospitals created

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 7. Number of family-owned private hospitals in 2018

Source: Own elaboration

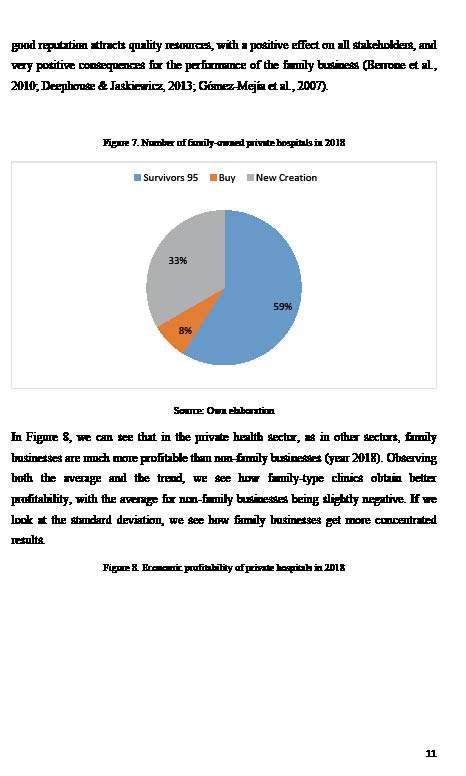

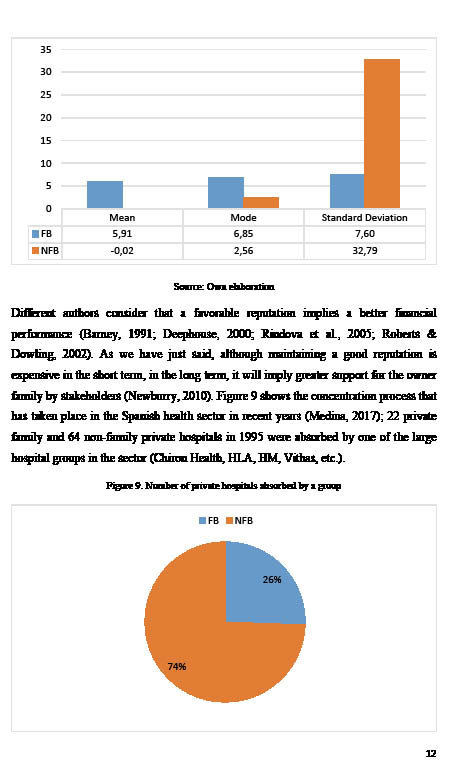

In Figure 8, we can see that in the private health sector, as in other sectors, family businesses are much more profitable than non-family businesses (year 2018). Observing both the average and the trend, we see how family-type clinics obtain better profitability, with the average for non-family businesses being slightly negative. If we look at the standard deviation, we see how family businesses get more concentrated results.

Figure 8. Economic profitability of private hospitals in 2018

Source: Own elaboration

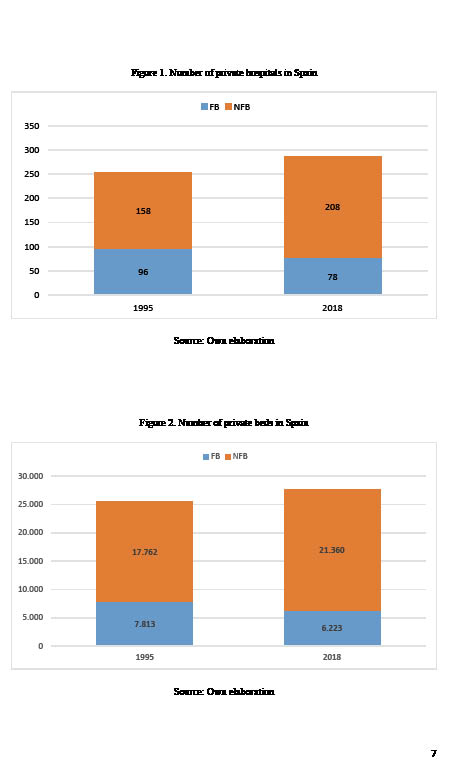

Different authors consider that a favorable reputation implies a better financial performance (Barney, 1991; Deephouse, 2000; Rindova et al., 2005; Roberts and Dowling, 2002). As we have just said, although maintaining a good reputation is expensive in the short term, in the long term, it will imply greater support for the owner family by stakeholders (Newburry, 2010). Figure 9 shows the concentration process that has taken place in the Spanish health sector in recent years (Medina, 2017); 22 private family and 64 non-family private hospitals in 1995 were absorbed by one of the large hospital groups in the sector (Quirón salud, HLA, HM group, Vithas, etc.).

Figure 9. Number of private hospitals absorbed by a group

Source: Own elaboration

Regarding the market share, the 10 main agents in the private hospital sector account for 77% of private hospitals and 83% of private beds. Quirónsalud and VITHAS are the private hospital groups that have the largest number of hospitals and beds. Specifically, Quirónsalud represents 25% of private hospitals and 31% of beds, while VITHAS represents 12% of hospitals and 12% of beds. The first family group would be the HM group, contributing 7% of clinics and private sector beds.

There was a strong dynamism in the private clinic sector in the 2011-2016 period, with many changes in ownership (see Figure 10). The main increase in turnover in the sector has been the increase in the number of patients attended by the clinics. This increase in patients is explained by the increase in the private insurance sector (Fundación MAPFRE, 2019).

Figure 10. Change of ownership in private hospitals (1995-2018)

Source: Own elaboration

5. Conclusions

Family businesses have survived through the generations, maintaining their family character when they have specialized, or converted to companies with advanced technology, offering exclusive services, which allow them to be very profitable.

The survival of 60% of family businesses in the private hospital sector in Spain is one of the most surprising results of this study. However, it is appropriate to soften the positive effect, taking into account that the weight of the family business in the sector fell by 10% between 1995 and 2018. From the SEW perspective, family character implies a long-term vision and the intention to preserve and transmit the family legacy to the next generation. Legacy is not only economic, but also emotional.

In the private hospital sector, it seems that the effect of transmission of intangible values has a greater influence on survival than in other sectors. From the SEW perspective, dimensions such as the identification of the family with the company and the reputational factor to be transmitted to the next generation would explain, the situation of the family business in the Spanish health sector. The identification of family members with an organization makes them perceive the company’s prestige as theirs. Developing adequate business behavior would allow them to maintain the positive image of the company and themselves. Consequently, from the family business, strategic decisions are adopted that enable preservation of the reputational legacy, achieving a high survival in the sector (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2014). Strengthening this idea, Deephouse and Jaskiewicz (2013) considered that high identification motivates family members to pursue a favorable reputation of the company that benefits them, increasing their SEW.

Family businesses that could not invest in technology to remain competitive closed or were acquired by larger groups, some of them family groups. The issues of size, specialization, or the offer of services with cutting-edge technology seem relevant to preserve the family character, observing a great concentration in the sector.

This study makes several contributions. As for the literature on family businesses, it incorporates a study on the health sector, an area where research on “health care organizations” and “family business” is very scarce. Second, it presents new work from the theoretical perspective of SEW. Third, it offers the first database that classifies the private hospital sector according to its family property or not.

This work suffers from certain limitations, especially based on the available information. As mentioned in the methodology, the difficulty in developing this research work was mainly because of the lack of a database that classifies clinics according to family and non-family ownership. Given the laboriousness of the work, we carried out a cross-sectional study exclusively analyzing the years 1995 and 2018. Subsequent investigations could propose a data panel for the 1995-2018 period that includes all the movements of companies in the interim period.

In this study, we were not able to investigate why certain family businesses in the Spanish private health sector in 1995 did not survive in 2018. Future research could raise questions such as the following: Was non-survival an issue related to their family character (lack of successor process planning, lack of successor)? Were issues of an economic nature (percentage of family income dedicated to private medicine spending)? Were issues related to the health sector (such as the development of the public system that has opened more public hospitals)? Questions of location: Is there a difference in the location of private hospitals due to the different levels of purchase of medical care in hospitals outside the Public Health Services among the different Regional Health Systems? Do the private family clinics that survived have differential characteristics? To answer these questions, we propose implementing the case method in future investigations.

The hypothesis we manage is that the sector will continue in the process of concentration, favored by the entry of new investors compared to a traditional clinical model owned by a group of doctors. This process will favor the creation of larger hospital groups and greater professionalization of management. In this process, what role is reserved for the family business?

References

Astrachan, J. H., and Kolenko, T. A. (1994). A neglected factor explaining family business success: Human resource practices. Family Business Review, 7(3), 251-262.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R. and Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82-113.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C. and Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279.

Cabrera-Suárez, M. K., Déniz-Déniz, M. D. and Martín-Santana, J. D. (2014). The setting of non-financial goals in the family firm: The influence of family climate and identification. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(3), 289-299.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., and Sharma, P. (2003). Succession and nonsuccession concerns of family firms and agency relationship with nonfamily managers. Family Business Review, 16(2), 89-107.

Cleary, P., Quinn, M., and Moreno, A. (2018). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: A longitudinal content analysis of corporate disclosures. Journal of Family Business Strategy.

Danco, L. A. (1975). Beyond survival: A business owner’s guide for success. Center for Family Business.

Deephouse, D. L., and Jaskiewicz, P. (2013). Do family firms have better reputations than non‐family firms? An integration of socioemotional wealth and social identity theories. Journal of management Studies, 50(3), 337-360.

Fundación MAPFRE (2019). El Mercado español de seguros en 2018. Servicio de Estudios de MAPFRE.

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., and De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653-707.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., and Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106-137.

Hauck, J., Suess-Reyes, J., Beck, S., Prügl, R., and Frank, H. (2016). Measuring socioemotional wealth in family-owned and-managed firms: A validation and short form of the FIBER scale. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(3), 133-148.

Ibrahim, A. B., Soufani, K., and Lam, J. (2001). A study of succession in a family firm. Family Business Review, 14(3), 245-258.

IDIS (2019). Private healthcare, adding value. Situation analysis 2018.

Intituto de Empresa Familiar (2016). La empresa familiar en España (2015). Instituto de la Empresa Familiar, Barcelona, España.

Le Breton‐Miller, I. L., Miller, D., and Steier, L. P. (2004). Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 305-328.

Le Breton-Miller, I., and Miller, D. (2009). Agency vs. stewardship in public family firms: A social embeddedness reconciliation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(6), 1169-1191.

Martín, J.C., and Ortega-Díaz, Mº I. (2016). Rendimiento hospitalario y benchmarking. Revista de Economía Aplicada, 24 (70),27-51

Medina, P. (2017). The online reputation management of hospital brands: A model proposal. Zer. 22 (43), 53-68.

Minichilli, A., Nordqvist, M., Corbetta, G., and Amore, M. D. (2014). CEO succession mechanisms, organizational context, and performance: A socio‐emotional wealth perspective on family‐controlled firms. Journal of Management Studies, 51(7), 1153-1179.

Morgan, T. J., and Gómez-Mejía, L. R. (2014). Hooked on a feeling: The affective component of socioemotional wealth in family firms. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(3), 280-288.

Nason, R. S., Carney, M., Le Breton-Miller, I., and Miller, D. (2019). Who cares about socioemotional wealth? SEW and rentier perspectives on the one percent wealthiest business households. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 10(2), 144-158.

Newburry, W. (2010). Reputation and supportive behavior: Moderating impacts of foreignness, industry and local exposure. Corporate Reputation Review, 12(4), 388-405.

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., and Chua, J. H. (2003). Succession planning as planned behavior: Some empirical results. Family Business Review, 16(1), 1-15.

Sorenson, R. L., Goodpaster, K. E., Hedberg, P. R., and Yu, A. (2009). The family point of view, family social capital, and firm performance: An exploratory test. Family Business Review, 22(3), 239-253.

Strike, V. M., Berrone, P., Sapp, S. G., and Congiu, L. (2015). A socioemotional wealth approach to CEO career horizons in family firms. Journal of Management Studies, 52(4), 555-583.

Umans, I., Lybaert, N., Steijvers, T., and Voordeckers, W. (2019). The influence of transgenerational succession intentions on the succession planning process: The moderating role of high-quality relationships. Journal of Family Business Strategy. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2018.12.002

Zellweger, T. M., Kellermanns, F. W., Chrisman, J. J., and Chua, J. H. (2012). Family control and family firm valuation by family CEOs: The importance of intentions for transgenerational control. Organization Science, 23(3), 851-868.