|

|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Customer Orientation in Family Businesses

Javier Morales Medianoa*,José Luís Ruiz-Alba b, Isolino Pazos Villas c, Raquel Ayestarán c

a Universidad Pontificia Comillas – ICADE, C. Alberto Aguilera, 23, 28015, Madrid, Spain

b University of Westminster, 35 Marylebone Rd., NW1 5LS, London, United Kingdom

c Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, Ctra. Pozuelo a Majadahonda, Km 1.800, 28223, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain

Received 18 July 2019; accepted 28 July 2019

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M30

KEYWORDS

Customer orientation; COSE; family influence; customer experience; HRS

Abstract The purpose of this article is to investigate the customer orientation of service employees (COSE) in family businesses. This study elaborates on the perception and importance of COSE in family-owned companies. The paper also proposes new consequences of COSE in the family business context.

The research is based on a qualitative study comprised of 13 interviews conducted on senior managers in family firms. The results are analysed using NVivo 11.

This investigation confirms the relevance of the COSE construct in family businesses and the role of the family influence over it. New consequences are elicited, including differentiation, customer experience, and customer well-being.

The results show that practitioners consider COSE as a key element for success. This study sheds light on how COSE can be applied in a family business in order to enhance the customer experience.

This study expands on the potential of COSE with the use of family businesses for the first time and introduces new consequences from the original model.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M30

PALABRAS CLAVE

Customer orientation; COSE; family influence; customer experience; HRS

Customer Orientation in Family Businesses

Resumen The purpose of this article is to investigate the customer orientation of service employees (COSE) in family businesses. This study elaborates on the perception and importance of COSE in family-owned companies. The paper also proposes new consequences of COSE in the family business context.

The research is based on a qualitative study comprised of 13 interviews conducted on senior managers in family firms. The results are analysed using NVivo 11.

This investigation confirms the relevance of the COSE construct in family businesses and the role of the family influence over it. New consequences are elicited, including differentiation, customer experience, and customer well-being.

The results show that practitioners consider COSE as a key element for success. This study sheds light on how COSE can be applied in a family business in order to enhance the customer experience.

This study expands on the potential of COSE with the use of family businesses for the first time and introduces new consequences from the original model.

Introduction

The importance of family businesses in today’s economy is significant as shown in developed countries through a number of indicators, such as the percentage of GDP that the businesses represent (Lee, 2006; Aldamiz Echevarría, Idígoras, & Vicente-Molina, 2017). However, despite the economic importance of family firms, academics still wish to investigate these types of companies in the marketing field further (Reuber & Fischer, 2011). Indeed, Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., & Guzmán-Parra (2013) found that there are a limited number of studies on family businesses from a marketing perspective.

Another reason for investigation into family businesses from a marketing perspective is to examine certain characteristics of family businesses, including their complexity, dynamism, and richness in intangible resources (Habbershon & Williams, 1999). Furthermore, researchers wish to understand the ways in which resources and capabilities are used in order to generate these aforementioned characteristics that set family businesses apart from other firms. (Tokarczyc, Hansen, Green, & Down, 2007).

Several resources and capabilities of family-owned companies can be studied (Lee & Le Breton-Miller, 2006). Amongst these, Blocker, Flint, Myers, & Slater (2011) studied customer orientation (CO) and proved it to be an important capability to create higher value for customers. Indeed, CO still attracts the interest of many scholars (Bommaraju, Ahearne, Krause, & Tirunillai, 2019; Mukerjee & Shaikh, 2018). Unfortunately, very little have studied the construct of CO from the perspective of family businesses (González-Porras, Ruiz-Alba, & Guzmán-Parra, 2018). Based on the literature review conducted for this study, no studies have questioned whether the application of CO is different in the context of family companies.

Thus, the overarching aim of this study is to investigate the role of customer orientation in family businesses. The idea behind this aim is explore the construct of CO to assess its importance, applicability, and potential consequences.

As a consequence of the above, the following research questions (RQ) are proposed:

RQ1: What is the consideration of customer orientation in a family business?

RQ2: Which characteristics make an employee to be customer oriented?

RQ3: How does being a family business specifically affect the customer orientation of the employees?

Regarding the article structure, the introduction presents the research justification and the research questions, together with a presentation of the article structure. Then, the literature review reviews the family business academic field, with a particular focus on the construct of CO. Third, this study describes the methodological approach that has been followed. Next, the article offers the results and findings from the qualitative study based on the contributions of 13 senior managers from different family companies. The article closes with a conclusion that includes contributions, potential future research avenues, and limitations.

Literature Review

Marketing in family business

As discussed in the Introduction, despite the potential of family-owned companies to do things differently from companies with alternate ownership structures (Davis, 1983), little research has been published about specific functions of family companies, and even less about their marketing strategies and activities (Clark, Key, Hodis, & Rajaratnam, 2014).

Habbershon & Williams (1999) grouped the main differences of family companies identified in the academic literature. These differences are present in a twofold level, first, their organization, and second, their capabilities. Based on this research, the group of resources that emerge from the family involvement is coined as ‘familiness’. The level of familiness serves to assess the different competitive advantages of family companies. The effects of familial involvement has been studied in a number of researches. For instance, there are studies connecting familiness to internationalization strategies (Segaro, Larimo, & Jones, 2014; Alayo, Maseda, Iturralde, & Arzubiaga, 2019; González-Porras, Ruiz-Alba, Rodríguez-Molina, & Guzmán-Parra, 2019), quality management (Danes, Loy, & Stafford, 2008), and reputation (Craig, Dibrell, & Davis, 2008). However, the field of marketing in family business is largely unexplored and frequently ignored by academics (Sharma, 2004; Reuber & Fischer, 2011).

An exception to this lack of attention from researchers is in the special issue about marketing and family firms published by the journal Family Business Review (Reuber & Fischer, 2011). Four articles were published on this issue; two discussed the perception of family companies in the market (Micelotta & Raynard, 2011; Parmentier, 2011) and two studied marketing practices implemented by family firms (Beck, Janssens, Debruyne, & Lommelen, 2011; Zachary, McKenny, Short, & Payne, 2011). The latter articles gave special attention to the construct of Market Orientation (MO) as Cabrera-Suarez, Déniz-Déniz, & Martín-Santana (2011) also did.

However, as Morales Mediano and Ruiz-Alba (2019a) suggest, it is important to clarify the stance taken by academics when dealing with the constructs of MO and CO. According to these authors, there are three research streams on this regard. The first stream considers MO and CO as synonyms, the second defines CO as part of MO, and the third considers MO and CO as independent constructs. Surprisingly, no study related to MO or CO and family businesses explicitly assumed one of these three streams, instead leaving this interpretation to the reader. Conversely, this study embraces the third research stream and considers CO an individual and behavioural characteristic of employees in front of MO defined as an organizational-level construct (Hennig-Thurau and Thurau, 2003). This stance opens multiple new possibilities to study the individual, behavioural, and independent-to-MO perspective of CO in relation to family-owned companies to start closing this research gap.

Customer orientation

Saxe & Weitz (1982) placed CO at the core of the marketing concept and also empirically measured the construct within salespeople. However, as Shapiro (1988) claimed, there was not yet a clear differentiation between MO and CO. That was why Hennig-Thurau & Thurau (2003) shed light on the concept of CO and treated it separately to MO. Hennig-Thurau (2004) pointed out that the economic success for services companies could be significantly impacted by customer orientation. That association is due to “the intangible nature of services and their high level of customer interaction and integration” (Hennig-Thurau 2004, p.461).

Following that reasoning, Hennig-Thurau & Thurau (2003) developed a theoretical framework of the customer orientation of service employees (COSE) that was proved empirically together with its consequences on a later research (Hennig-Thurau 2004).

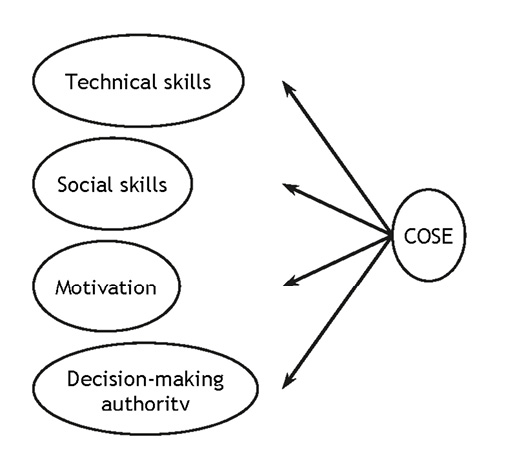

The COSE model, in its version in 2004, consists of four characteristics of service employees, as follows: technical skills, social skills, motivation, and decision-making authority. Technical and social skills are those needed by an employee to respond to the customer’s requirements, motivation is the personal incentive that the service employee requires to fulfil those needs, and decision-making authority is the perceived freedom (by the employee) that he or she has to fulfil customer needs (Hennig-Thurau & Thurau 2003) Figure 1 illustrates the model structure.

Figure 1: Model of COSE dimensions and consequences (Hennig-Thurau 2004).

These four dimensions were proven to impact customer’s satisfaction, commitment, and retention. These three consequences of the COSE construct are considered by Hennig-Thurau (2004) as crucial factors for service companies’ success. The test was carried out through a questionnaire presented to service customers from both travel agencies and media retailers (Hennig-Thurau 2004).

Due to the practical approach of the model, it is possible to extract several implications for management of service companies, from budget allocation for staff training to recruiting strategies. These actions should be aimed at improving the four dimensions considered in the COSE model (Hennig-Thurau 2004).

In fact, the COSE model has been embraced by several authors since it was presented for the first time. Some authors based their research on the original model (Ndubisi, 2012; Jansri & Trakulmaykee, 2016), but did not fully utilise the measurement instrument as originally developed by Hennig-Thurau (2004). Likewise, Kim (2009), Walsh, Ndubisi, & Ibeh (2009), Kim & Ok (2010), Kang & Hyun (2012), and Kuppelwieser, Chiummo, & Grefrath (2012) attempted to go further than the original COSE model, either by introducing new consequences or implementing control variables as Hennig-Thurau (2004) suggested. Other authors focused their studies upon a specific industry, like banking. This was because COSE plays an important role in the banking industry, due to the high competitiveness (Moghadam, 2013), service complexity (Raie, Khadivi, & Khdaie, 2014), the need to understand the customer’s needs to provide an adequate service (Bramulya, Primiana, Febrian, & Sari, 2016), and the high level of interaction and duration of the relationship (Rouholamini & Alizadeh, 2016). Morales Mediano & Ruiz-Alba (2018) took one step further in this regard and studied COSE in the context of private banking. They considered private banking an ideal context for the study of COSE because they believed the industry was what they coined as a highly relational service (HRS).

However, despite the interest gained by the COSE model in recent years (Kuppelwieser, Chiummo, & Grefrath, 2012), it is striking to see the limited research related to this important construct and family businesses. Therefore, due to this gap in the literature, one may wonder whether or not the lack of previous research is due to a mismatch between the purpose and definition of the construct and the characteristics of family. Hence, the following two research questions are proposed:

RQ1: What is the consideration of customer orientation in family business?

RQ2: Which characteristics make an employee to be customer oriented?

Additionally, as it has been presented before, family-owned companies operate differently to other companies (Lee, 2006). This is why it is necessary to study the potential impact family companies on some traditional constructs, such as touched upon by Frank, Kessler, & Korunka (2012), but this has not yet been assessed with CO. Consequently, the following research question is proposed:

RQ3: How does being a family business specifically affect the customer orientation of the employees?

Methodology

Qualitative methodologies are particularly suitable when the purpose of the study is to investigate how practitioners perceive a specific construct (Yin, 2015). There are numerous alternatives amongst the different strategies for data gathering in the qualitative methodologies (Creswell, 2009). Amongst these, qualitative surveys have proven to be a valid and reliable procedure, and they have been extensively accepted and used (Kvale, 1994).

For the purpose of this study, a qualitative questionnaire was first prepared and discussed by four academics. The final version consisted of six questions related to the aim of the research. After minor amendments, the final version was used to interview a total of 13 practitioners out of 25 contacted. The group of practitioners consisted of senior managers working for family-run companies. The sample was considered valid (52% replied out of the 25 contacted) as the following criteria were met (Flick, 2010): (1) the variety of sectors (consumer goods, education, transportation, hospitality, health care), and (2) the depth a detail of the answers gathered.

Table 1 shows the details of the participants.

|

Participant |

Sector |

Company size |

|

P1 |

FMCG |

SME |

|

P2 |

Hospitality |

Large enterprise |

|

P3 |

Hospitality |

Large enterprise |

|

P4 |

Passenger Transport |

Large enterprise |

|

P5 |

Education |

SME |

|

P6 |

Finance |

SME |

|

P7 |

Consulting |

SME |

|

P8 |

FMCG |

Large enterprise |

|

P9 |

Healthcare |

SME |

|

P10 |

Hospitality |

SME |

|

P11 |

Hospitality |

Large enterprise |

|

P12 |

On-line store |

Large enterprise |

|

P13 |

Hospitality |

SME |

Table 1: List of participants (own elaboration).

Each questionnaire was checked for spelling and unclear answers were clarified through an email or phone call with the respondent. Following this, the written answers were loaded in the qualitative data analysis software NVivo 12 in order to obtain the corresponding qualitative analysis. This analysis was comprised of the reading and coding of all the data by two researchers, who simultaneously identified the main codes and themes related to each research question.

Results and Discussion

Research question 1: What is the consideration of customer orientation in family business?

There was a high level of consensus in relation to the consideration of customer orientation in family business. All the respondents agreed that COSE is essential for their business: “in our company it is crucial to be customer oriented” (P1). However, the reasons for this varied between participants.

The first group of five participants justified customer orientation due to the need to focus on the customer. According to these participants, putting effort into the customer is crucial to better know and understand your clients, to improve your service, and to differentiate from your competitors. In the words of P8: “we have been putting the focus on our customer for long years, why? Basically, because we have to give the customers what they want, otherwise our competitors will occupy the first position in their minds”.

A second group comprised of three participants who gave a high importance to the level of COSE due to its effect on the customer experience. In the greatest number of service companies, as expressed by the participants, the service employee is the strong determiner of the customer’s experience, such as in passenger transportation, lodging, or education. According to P3, “companies are working on the customer orientation to improve the customer experience”.

The third and final group of five participants expressed the importance of COSE in terms of its utility to understand and satisfy the customers’ needs, and therefore to create higher value for them. P13 explained this idea as follows: “customer orientation implies the wish to help, serve and satisfy the needs of our customer”.

Research question 2: Which characteristics make an employee to be customer oriented?

The second research question was represented in the interview by means of a question regarding the four dimensions of COSE as presented in the Literature Review. Each dimension was assessed by the participants. This resulted in a qualitative ranking of the four dimensions. Social skills were identified as the most relevant for the participants, followed by motivation, then technical skills, and last the decision authority of the service employee.

Social skills were deemed to be the most important and hence the skill that employees “must have more developed” (P10). The reason for this is that employees possessing adequate social skills will be able to empathize with customers. This empathy will eventually help the employee to listen actively, understand the customer needs and better serve them. P9 expressed this idea in the following particular manner: “social skills are critical to make the customer to feel sheltered”.

The level of motivation ranked second after social skills. Based on the responses, there are three ideas that underpin this importance: (1) the proactivity and adaptability of the employee, (2) a job well done, and (3) the image transmitted to the customer. As explained by P6, P4, and P10 respectively; “proactivity is crucial when delivering a service”; “the best motivation should be a well-done work”; “we have to transmit to our customer the good environment we have in our company”. Nevertheless, there are some particular services where motivation is taken for granted because of the characteristics of the service employees. P9 was the example for this: “this is a purely vocational industry, so motivation is a given”.

Thirdly, technical skills were considered as relatively important for several participants, but not as much as social skills or motivation. Five of the participants referred to technical skills as a requirement, but only based on the employee’s specific position and supported by a previous training. Therefore, technical skills are something the employee may learn or gain through experiences. P10 was clear on the limited impact of the technical skills: “the technical knowledge is something you need to learn and update, but they do not create value, every company has similar knowledges”. However, once again P9 diverged from the main consensus of participants, as according to this respondent, “there are services where technical skills are complex and mandatory by law”.

Lastly, participants placed decision authority as the least important due to the fact that family business are usually more hierarchized. This strong hierarchy means that each employee in the organisation has well-defined responsibilities, and therefore the employee is not expected to assume a high level of decision authority. P13 explained this in the following: “the importance of the decision authority will depend on the level of responsibility of the position as defined by the company”. On this regard, P9 was also in disagreement with the other respondents. In particular services where the judgement of the employee is critical for the service outcome the employee must enjoy complete freedom to take decisions. In the words of P9: “in some positions, having decision authority is a life-or-death matter”.

Research question 3: How does being a family business specifically affect the customer orientation of the employees?

Most of the participants (10 out of 13) did see a difference of the impact of a family company on the level of employee CO. However, the arguments varied from one participant to another. Five of the participants expressed this influence as the flexibility of the organisational structure and the consequent ease to develop the customer orientation of employees. P6 and P8 expressed respectively: “family companies have more flexible structures” which helps “to take decisions and execute them quicker than other companies”.

Five other participants pointed out the direct involvement of the family as the main difference in the customer orientation of service employees. This is due to three factors: (1) the closeness to the employees and their work, and (2) the better working environment that this attitude creates within the company. P11 elaborated this idea as follows: “in our case, the fact that the family uses our services and gives priority to the customers highlights in an exemplary manner how important the customer is”. Another participant expressed a similar idea but added that the imitation effect occurs when this closeness is translated to the customer. P9’s argument was: “The way we treat each other amongst the family is expanded to the rest of employees, so we treat them in a very familiar way. This implies that the way we treat our customers is adopted by our employees by imitation”.

Despite the high consensus showed by the participants on the influence of a family company on COSE, there were three participants that expressed the opposite. According to these participants the level of COSE should not be associated in any case to the type of company the employee works for. Based on these responses, the customer orientation of employees is more linked to the type of service or the company management. In the words of P13: “I believe that customer orientation, as I mentioned before, has to be a essential competence of any employee working in this sector, regardless the company being family-owned or not”.

Conclusion and Future Research

The present study provides significant and original contributions to the academic knowledge. These contributions are also significant for professionals involved in family business companies.

The main academic contribution of this research is that it is the first study of the development of the construct of COSE in family companies. This study serves to confirm the following:

1. Customer orientation of service employees is considered an important behaviour within family companies for three reasons: (1) the level of differentiation attained, (2) the improved customer experience, and (3) the customer well-being.

2. Amongst the four dimensions of COSE, social skills stood out as the most important, followed by motivation, technical skills, and lastly decision-making authority.

3. The structure and characteristics of a family-run company influences the level of customer orientation by means of the organisational flexibility and the familial involvement that creates an increased closeness with the employee and a better working environment. These aspects are indeed part of the family influence construct developed by Astrachan, Klein, & Smyrnios (2002).

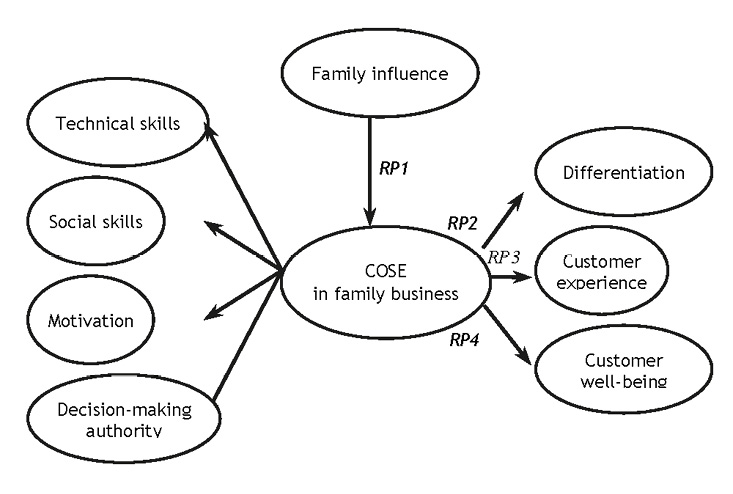

Undoubtedly, the three consequences of COSE in family business are a novelty in the field. Moreover, whereas the different importance of the COSE dimensions was already suggested by Morales Mediano & Ruiz-Alba (2018), no one confirmed this in relation to an empirical study in family business. Finally, the influence of a family company was confirmed. These three contributions open enormous possibilities for further research that should be based on a series of research propositions and a conceptual model, as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Consequences of COSE in family businesses (own elaboration).

This model invites to provide a group of research proposition (RP) that emanates from the answers to the research questions of this article and that can be subject to future investigation:

• RP1: Family influence has a direct impact on COSE in family business.

• RP2: COSE in family business has a direct impact on differentiation.

• RP3: COSE in family business has a direct impact on customer experience.

• RP4: COSE in family business has a direct impact on customer well-being.

Another interesting contribution is related to the responses from one participant (P9) whose company was in the healthcare industry. These results showed some differences with the rest of participants. These responses were primarily related to the characteristics of the service based on a vocational profession and the technical knowledge and judgement of the employees. This supports the conclusions of Morales Mediano & Ruiz-Alba (2019b) in their study about COSE in a highly relation services (HRS).

Practitioners can also benefit from this research. Understanding the influence of familiness on such an important construct as COSE should help professionals working for family companies to better deal with employees when developing their customer orientation, as well as foreseeing the influences of a high level of customer orientation.

As any research, the present study is not free of limitations. One limitation is related to the methodology. Qualitative methodologies are usually criticized for their lack credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Special care has been taken by the authors of this research to overcome these limitations. In particular, the heterogeneity of the sample should allow for the transfer of the conclusions to any other family company. Besides, a robust and structured methodology has been followed in order to eliminate any improvisation, to eliminate the risk of bias, and to ensure the neutral positioning of the researchers (Kvale, 1994).

To conclude, this article offers several future research avenues. The first and most obvious continuation is the complementation of this qualitative study with a quantitative study. The conceptual model and research propositions could be tested in this new research. Additionally, this study could also explore whether or not the four dimensions of COSE have different quantitative importance.

A second possible study would be to include both the management professionals and the employees of family-owned companies. It would also be of great interest to include the perspective of customers in this new research.

A final future research that has been opened tangentially in this paper is related to the definition of HRS (Morales Mediano & Ruiz-Alba, 2019b). As expressed by one participant, there are services, from all types of companies, whose characteristics require a special analysis. A definitive definition of HRS will contribute beyond doubt to the service marketing literature.

References

Alayo, M., Maseda, A., Iturralde, T., & Arzubiaga, U. (2019). Internationalization and entrepreneurial orientation of family SMEs: The influence of the family character. International Business Review, 28(1), 48-59.

Aldamiz-Echevarría, C., Idígoras, I., & Vicente-Molina, M. A. (2017). Gender issues related to choosing the successor in the family business. European Journal of Family Business, 7(1-2), 54-64.

Astrachan, J. H., Klein, S. B., & Smyrnios, K. X. (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem. Family business review, 15(1), 45-58.

Beck, L., Janssens, W., Debruyne, M., & Lommelen, T. (2011). A study of the relationships between generation, market orientation, and innovation in family firms. Family Business Review, 24(3), 252-272.

Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., & Guzmán-Parra, V. F. (2013). Trends in family business research. Small Business Economics, 40(1), 41-57.

Bommaraju, R., Ahearne, M., Krause, R., & Tirunillai, S. (2019). Does a customer on the board of directors affect business-to-business firm performance?. Journal of Marketing, 83(1), 8-23.

Bramulya, R., Primiana, I., Febrian, E., & Sari, D. (2016). Impact of relationship marketing, service quality and customer orientation of service employees on customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions and its impact on customer retention. International journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 4(5), 151-163.

Clark, T., Key, T. M., Hodis, M., & Rajaratnam, D. (2014). The intellectual ecology of mainstream marketing research: an inquiry into the place of marketing in the family of business disciplines. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(3), 223-241.

Craig, J. B., Dibrell, C., & Davis, P. S. (2008). Leveraging family‐based brand identity to enhance firm competitiveness and performance in family businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(3), 351-371.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Danes, S. M., Loy, J. T. C., & Stafford, K. (2008). Business planning practices of family‐owned firms within a quality framework. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(3), 395-421.

Flick, U. (2010). An Introduction to Qualitative Research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

González-Porras, J. L., Ruiz-Alba, J. L., & Guzmán-Parra, V. F. (2018). Customer orientation of service employees in family businesses in the hotel sector. Revista de Estudios Empresariales, segunda época(2), 73-85.

González-Porras, J. L., Ruiz-Alba, J. L., Rodríguez-Molina, M. A., & Guzmán-Parra, V. F. (2019). International management of customer orientation. European Journal of International Management. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1504/EJIM.2020.10022183

Habbershon, T. G. & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1-25.

Hennig-Thurau, T. (2004). Customer orientation of service employees: Its impact on customer satisfaction, commitment, and retention. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(5), 460-478.

Hennig-Thurau, T. & Thurau, C. (2003). Customer orientation of service employees—Toward a conceptual framework of a key relationship marketing construct. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 2(1-2), 23-41.

Jansri, W. and Trakulmaykee, N. (2016). Customer perceived value and customer orientation of salespeople in purchasing luxury natural products. In 7th International Research Symposium in Service Management: Service Imperatives in the New Economy: Approaches to Service Management and Change (pp. 157-169). Nakhonpathom: Service Education, Research and Innovation. Retrieved from: http://www.muic.mahidol.ac.th/conferences/irssm7/wp-content/downloads/IRSSM_7th_Proceedings.pdf

Kang, J. and Hyun, S.S. (2012). Effective communication styles for the customer-oriented service employee: Inducing dedicational behaviours in luxury restaurants patrons. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 772-785.

Kim, W. (2009). Customers’ responses to customer orientation of service employees in full‐service restaurants: a relational benefits perspective. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 10(3), 153-174.

Kim, W. & Ok, C. (2010). Customer orientation of service employees and rapport: influences on service-outcome variables in full-service restaurants. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 34(1), 34-55.

Kuppelwieser, V. G., Chiummo, G. R. and Grefrath, R. S. (2012). A replication and extension of Hennig-Thurau’s concept of COSE. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 11(3), 241-259.

Kvale, S. (1994). Ten standard objections to qualitative research interviews. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 25(2), 147-173.

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Lee, J. (2006). Family firm performance: Further evidence. Family Business Review, 19(2), 103-114.

Micelotta, E. R. & Raynard, M. (2011). Concealing or revealing the family? Corporate brand identity strategies in family firms. Family Business Review, 24(3), 197-216.

Miller, D. & Le Breton‐Miller, I. (2006). Family governance and firm performance: Agency, stewardship, and capabilities. Family Business Review, 19(1), 73-87.

Moghadam, M. (2013). Determinants of customer retention: Offering a model to banking industry. Journal of Applied Business and Finance Researches, 2(3), 76-81.

Morales Mediano, J. & Ruiz-Alba, J. L. (2018). New perspective on Customer Orientation of Service Employees: A conceptual framework. The Service Industries Journal. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1080/02642069.2018.1455830.

Morales Mediano, J. & Ruiz-Alba, J. L. (2019a). The Market Orientation and Customer Orientation Continuum: A Literature Review for Service Marketing. In B. Palacios Florencio (Ed.), XXXIII AEDEM Annual Meeting: Diversidad y talento: Efectos sinérgicos en la gestión (pp. 1786-1794). Seville: AEDEM – European Academy of Management and Business Economics. Retrieved from https://redaedem.org/uploads/congresos/doc/19/Libro%20XXXIII%20AEDEM%20Annual%20Meeting.pdf

Morales Mediano, J. & Ruiz-Alba, J. L. (2019b). Customer orientation in highly relational services. Marketing Intelligence and Planning. Accepted for publication.

Ndubisi, N. O. (2012). Mindfulness, reliability, pre-emptive conflict handling, customer orientation and outcomes in Malaysia’s health sector. Journal of Business Research. 65(4), 537-546.

Parmentier, M. A. (2011). When David met Victoria: Forging a strong family brand. Family Business Review, 24(3), 217-232.

Raie, M., Khadivi, A., and Khdaie, R. (2014). The effect of employees’ customer orientation, customer’s satisfaction and commitment on customer’s sustainability. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (Oman Chapter), 4(1), 109-121.

Reuber, A. R. & Fischer, E. (2011). Marketing (in) the family firm. Family Business Review, 24(3), 193-196.

Rouholamini, M. & Alizadeh, R. (2016). A study of customer orientation in the Iranian banking industry: The case of Mellat Bank. International Journal of Research in Management, Economics and Commerce, 6(6), 50-55.

Saxe, R. & Weitz, B. A. (1982). The SOCO scale: A measure of the customer orientations of salespeople. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(3), 343-351.

Shapiro, B. P. (1988). What the hell is ‘market oriented’? Harvard Business Review, 66(6), 119-125.

Segaro, E. L., Larimo, J., & Jones, M. V. (2014). Internationalisation of family small and medium sized enterprises: The role of stewardship orientation, family commitment culture and top management team. International business review, 23(2), 381-395.

Sharma, P. (2004). An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future. Family business review, 17(1), 1-36.

Walsh, G., Ndubisi, N. O., and Ibeh, K. I. N. (2009). After the horse has left the barn it’s too late to close the door: a study of service firms’ conflict handling ability. In T. Flannery (Ed.), Australia and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference (ANZMAC) Annual Conference. Melbourne: ANZMAC – ANZAM. Retrieved from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/After-the-horse-has-left-the-barn-it’s-too-late-to-Walsh-Ndubisi/cb6249efe2f24e55a8117535600af671fe95bbbc

Yin, R. K. (2015). Qualitative research: from start to finish. New York: Guilford Publications.

Zachary, M. A., McKenny, A., Short, J. C., & Payne, G. T. (2011). Family business and market orientation: Construct validation and comparative analysis. Family Business Review, 24(3), 233-251.