|

|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Family firms’ profile: Leiria Region

Ines Lisboaa*

a School of Technology and Management, Centre of Applied Research in Management and Economics, Polytechnic Institute of Leiria (Portugal)

Received 02 february 2019; accepted 11 June 2019

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10, M14

KEYWORDS

Family firms; business profile; family commitment; family identity; Leiria/ Portugal

Abstract Most firms around the world are family firms. Their relevance and contribution to country’s economy is globally recognized. Therefore, understand these companies in detail is crucial. This study aims to design family firms profile using a sample of 233 family firms of Leiria region. Results show that most of respondent firms are exclusively owned and controlled by the family. Moreover, 70% are in the first generation, as 33% are in the business for less than 10 years. In mean, more than two family members actively work in the firm. The family identity is present in the firm, as well as the family culture and commitment. The family is an important influence in the business.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10, M14

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresas Familiares; perfil de negocios; family commitment; identiad familiar; Leiria/ Portugal

Perfil de las Empresas Familiares en la Región de Leiria

Resumen La mayoría de las empresas del mundo son familiares. Su relevancia y contribución a la economía del país es reconocida globalmente. Por lo tanto, entenderlas en detalle es crucial. Este estudio tiene como objetivo diseñar el perfil de estas empresas utilizando una muestra de 233 empresas familiares de la región de Leiria. Los resultados muestran que la mayoría de las empresas encuestadas son propiedad y control exclusivo de la familia. Además, el 70% pertenece a la primera generación, ya que el 33% está en el negocio por menos de 10 años. Es decir, más de dos miembros de la familia trabajan activamente en la empresa. La identidad familiar está presente en la empresa, así como la cultura y el compromiso familiar. La familia es una influencia importante en el negocio.

Introduction

The Portuguese Association of Family Business (APEF – Associação Portuguesa de Empresas Familiares, 2018) estimates that family firms represent around 70% of firms worldwide, making relevant contributions to economic recovery, special after 2007/2008 financial crisis, when diverse economies had some financial problems, and to job and wealth generation (Pimentel, Scholten and Couto, 2017, APEF, 2018). Likewise, it is critical to understand this type of companies, namely its characteristics that may enhance the firm’s value, but can also limit its growth.

This work aims to provide a profile of family firms in Leiria region. Leiria is the 13th largest district in Portugal but is the 3rd regarding the gross domestic product per resident, after Lisbon and Oporto (Pordata, 2018). Thus, Leiria is an important region to Portugal, due to its contribution and to help boosting the economy. Moreover, Lisboa (2018) estimates that family firms are more than 90% of active firms in Leiria. These facts justify the need of this study to better understand family firms.

Information about ownership and governance, executive manager, family members involved in the company and the board, the family generation, and corporate values, commitment and culture are analyzed to characterize family firms in Leiria region and compare it with other regions.

The results show that to most of the respondents, the family totally owns and controls the firm. Male managers are predominant, as well as a single manager rather than a board of directors, which can be justified due to the firm’s dimension. Most firms are in the first generation, but this can explain with the number of years that these firms are in the business (61% are in the business for less than 20 years). More than two family members actively participate in the firm, contributing to the diffusion of family identity. Finally, the family identity, culture and commitment are in the family business, as we show using the factorial analysis. The family is an important factor to the family firm’ success and perpetuation for the future.

This work makes a great contribution to family firms debate, since a characterization of family firms in Leiria region is provided, helping to design a profile of family firms. Moreover, it is analyzed a region where family firms are predominant, and the contribution of firms to the country gross domestic product is greater. The contribution is not only relevant to empirical literature but also to practitioners, specially owners and managers of family firms as they can understand the relevance of this type of firms and how they can use family firms’ characteristics to enhance the firm’s value.

The work structure is the following: after this introduction chapter, chapter 2 reviews literature of family firms, namely concept, and its main characteristics. Chapter 3 explains the sample and methodology. Chapter 4 discusses the main results. The last chapter shows the conclusions of the work.

Literature review

Family firm’s thematic is been debated for decades. The work of Berle and Means (1932) call the attention for the separation of ownership and management. Later, Wortman (1994) argued that family firms’ topic has been studied for more than 30 years. La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer (1999) said that family firms are prevalent all over the world and are the oldest type of firms. More recent, diverse studies confirm that family firms make a vital contribution to overall economy and wealth (e.g. APEF, 2018).

According to Sraer and Thesmar (2007), family firms have singular characteristics, which are different from those of non-family firms. Although, family firm’s topic has not been widely accepted, due to the difficulty to find a unique definition globally recognized (Pimentel et al., 2017). This makes difficult to compare different studies and to make generic conclusions about family firms (Miller, Breton-Miller and Cannella, 2007).

Analyzing diverse concepts of family firms, three fundamental factors are usually present: ownership, management, and perpetuation of the firm. 1) Regarding ownership the family must own at least part of the firm. Some researchers establish a minimum percentage of ownership, as 10% (Braun and Sharma, 2007), 20% (La Porta et al., 1999), 25% (European Family Business, 2018) or more than 50% (Basco, 2013), while others only argued that the family must be the major owner (Miralles-Marcelo, Miralles-Quirós and Lisboa, 2014). 2) Some researchers argue that the family must be in the board of director (Anderson and Reeb, 2003), while others say that must be the executive officer (European Family Business, 2018) or that the executive officer must be the founder or successor (Villalonga and Amit, 2006 and 2008). 3) Finally, a family firm must promote the perpetuation of the firm to future generations (Ward, 1987). Although, this factor is difficult to measure and most studies only see if there are more than one family member working in the firm.

Martín-Reyna and Duran-Encalada (2012) argued that the family firm’s definition dilemma may be explained due to the different cultural and legal contexts, that may lead to different factors to call a firm as family firm. Although, there is a consensus that “family firms are those where a family owner exercises much influence over the firm’s affairs” (Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro, 2011:658).

Astrachan, Klein and Smyrnios (2002) created a scale (F-PEC scale) that includes three subscales (power, experience and culture) to analyze the influence of the family in the business. The power wants to measure the dominance of the firm through ownership, management, and financing. Experience refers to family’s experience in the firm, which can be measured through the family generation in activity. Finally, culture is measured through the values and aims of the firm must be embedded in those of the family. Jaskiewicz González and Schiereck (2005) used the F-PEC scale and created different clusters of family firms attending of the family involvement in the firm. These clusters are: weak, normal and strong.

Meanwhile, there is a consensus that family firms have singular characteristics that make them apart from non-family ones (Kellermanns, Eddleston, Barnett and Pearson, 2008). Gersick, Davis, Hampton and Lansberg (1997) argued that in family firms there are three independent subsystems that can overlap, namely family, ownership, and management. Family members may be owners and/or managers of the firm, managers may be family or non-family members, some family members may own the firm while other no. Therefore, some conflict of interests may arise as the family sees the firm as an extension of their heritage, non-family owners may want to maximize the firm’s return and non-family managers may try to satisfy their self-interests (Gersick et al., 1997).

Family founder has a singular involvement in the firm, not only because he/she created the firms, but also because he/she supports the entrepreneurship. Moreover, the firm is the family’s investment, the source of income and employment, the status and reputation, and the family’ inheritance (Chami, 2001, Gomez-Mejia, Larraza-Kintana and Makri, 2003, Kellermanns et al., 2008).

The family wants to promote the continuity of the firm across future generations (Kellermans et al., 2008). Therefore, family and the firm’ aims are congruent, and the strategy and procedures are consistent over time (Gomez-Mejia, Haynes, Nuñez-Nickel, Jacobson & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007). Trust and long-term relationships between all stakeholders are also established (Anderson and Reeb 2003), communication is simpler, and the decision making is faster (Chami, 2001).

Usually a family’ owner or other family member is the firm’ manager or highly control an external manager. Thus, agency cost between the principal and manager is avoided or at least reduced (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Likewise, La Porta et al. (1999) argued that family ownership acts as a substitute for legal protection of investors.

Investments are also done in a long-term perspective, as the family wants the firm to continue successfully across future generations. Therefore, manager’s myopia of short-term results is avoided, and family investors are known as patient capital (Nieto, Casasola, Fernánde and Usero, 2009).

Despite characteristics that enhance the family firms’ value and entrepreneurial behavior, some singularities of these firms limit their growth and sustainability in the future. The family has difficulty to break with the past and to leave the comfort zone, making difficult to follow the market changes (Martins, 1999). Disinvestments usually are not done or are done too late, leading to risk increasement (Lisboa, 2018). Moreover, conservative investments are made to avoid risks, leading to the stagnation of the firm, and to the opposite of its expectations, it means, to increase risk instead of avoiding it (Burkart, Panunzi and Shleifer, 2003).

When the firm has free cash flows, the family may try to satisfy self-interests, leading to the expropriation of small investors and the firm’s wealth (Barontini and Caprio, 2006). This leads to other type of agency costs (type II): between group of investors, which is enhanced due to the lack of monitorization of family members (Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino and Buchholtz, 2001). This problem is related with the socio-emotional wealth proposed by Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007). Not only the maximization of the firm’ value is an aim of a family firm, but also the maximization of the family private benefits, that enhance the family reputation and wealth. Moreover, misunderstanding between family members that work in the firm and others family members may also occur, leading to another agency problem (Villalonga, Amit, Trujillo and Guzmán, 2015).

Moreover, the family may be in high positions even when they do not have enough knowledge or are prepared to do it. This may lead to inefficient decisions, which may increase the firm risk (Miller et al., 2007). The lack of succession preparation is another problem (Lisboa, 2018). In fact, most firms fail to pass to the second or other generation since the founder usually sustain the firm control and not prepare it. Moreover, more generations involved in the firm may bring more conflicts as there are more persons in charge, making it difficult to find a consensus (Nieto et al., 2009). The firm’ workers may also not be identified with the successor and may be less involved in the firm than before (Lisboa, 2018).

All these peculiarities set family firms apart from non-family counterparts, giving relevance to understand the dynamics of family firms.

Sample and methodology

Sample

This work analyzes family firms in Leiria region. Leiria is the 13th largest region of Portugal but is the 3rd region with the major contribution to the gross domestic product by residence (Pordata, 2018). It includes 16 municipalities, namely: Alcobaça, Alvaiázere, Ansião, Batalha, Bombarral, Caldas da Rainha, Castanheira de Pêra, Figueiró dos Vinhos, Leiria, Marinha Grande, Nazaré, Óbidos, Pedrogão Grande, Peniche, Pombal e Porto de Mós.

Leiria is in the coastal zone, with diverse infrastructures and transports. It has companies from diverse industries: from the extractive industry, to ceramics, cement, plastic, molds, furniture, and glass production. Moreover, tourism is also relevant not only due to the beach, but also because it has two monuments classified as world heritage (JLM Consultores de Gestão, Sargento, Lopes and Fernandes, 2014).

Lisboa (2018) has analyze this region and estimate that family firms represent around 90% of firms in Leiria. Therefore, the choice of this sample was due the relevance of the region, and the importance of family firms in this region.

First a list of firms classified as family firms by SABI database was collected. Sabi listed 11 456 active companies and classified as family ones 10 630. Only 4 700 companies had contact information (diverse companies are micro companies without any contact information, other than address).

For these companies with contact information, an electronic survey was sent to characterize and profile family business. The survey was sent by email and was active from April 2018 till June 2018. The study guarantees the confidentiality of the answers and the collected data. The number of answers was 233, around 5% of the possible sample. All answers are from private-own firms.

Data collection

The survey was design based on the works of Astrachan et al. (2002), namely the items that characterize the F-PEC scale and Pimentel et al. (2017) that have done a similar work to Azorean firms. It was divided into four parts. The first part refers to the firm’s identification, namely name and year of foundation. The name was asked to eliminate duplicate answers. The year of foundation helps to understand how long the firm is in the business.

The second part aims to characterized ownership and management. It was asked information about family ownership, how the firm is managed (by a board of directors or a singular manager), the influence of the family in the firm’s manager, and its gender. This helps to understand the family involvement in the firm.

In the third part firm’s experience is addressed. In which generation is the firm, how many family members are involved in the firm’s manager and work in the firm. The last part of the survey aims to characterize the family’s identity. Nine sentences were asked, and the family respondent should evaluate it on a 5-point scale, where 1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”.

Methodology

Descriptive and graphic analysis are used to describe the sample. The aim is to do a characterization of family firms in Leiria region, and thus these analyses help to reach our purpose. Moreover, we also use a principal component analysis to explore the identity, commitment and culture of the family in the firm.

Results

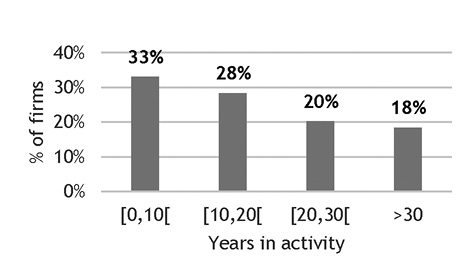

The first part of the survey was designed to make an identification of the firms in the sample. The 233 firms are working in business for different periods. We have firms in the business for more than 40 years, being the older in the business for 77 years, but we also have young firms with 1 year of activity. The mean value is 17 years. More detail can be seen in the following graph.

Figure 1: Years in activity

38% of family firms in Leiria region maintain their activity over 20 years, and 18% for more than 30 years. These percentages are smaller than those of Azorean firms (Pimentel et al., 2017), suggesting more new firms in Leiria region (which was confirmed in the Portuguese Statistics - INE). La Porta et al. (1999) argued that family firms are the oldest type of firms. Although, firms with more than 24 years may be in the second generation, and succession is one of the main reasons of family firms’ failure (Henrique, 2008).

The percentage of new companies in also relevant (33%), and 16% are in the business for less than 3 years. This result can be explained due to the crisis period from 2008 till 2014, since diverse companies went to bankruptcy during crisis (INE), and so some owners may have decided to open a new business after this period.

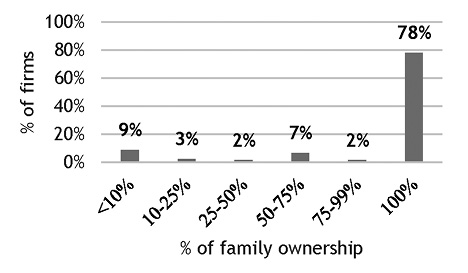

Regarding ownership, diverse studies, as Nieto et al. (2009) and Miralles-Marcelo et al. (2014), argued that family usually want to sustain the firm’ control. This result is also proved in this sample, as it can be observed in the following graph.

Figure 2: Percentage of family ownership

Most of family firms in Leiria region prefer to detain the total ownership (78%), as it helps to control the business. Moreover, as the firms in the sample are small and medium size, they may have few owners, which may explain the results. Moreover, 89% of the firms in the sample detain more than 25% of the firm’s ownership, which is the minimum percentage of ownership establish in some definitions of family firms, as for instance Nieto et al. (2009) and European Family Business (2018). Only a small percentage of firms detain less than 10% of the firm’s ownership.

Family firms with less than 10% of family ownership (9% of the firm in our sample) can be related with SGPS firms (5% of the firms in the sample are SGPS firms), and thus the family control is not directly exercised but through other family firms (pyramidal structure).

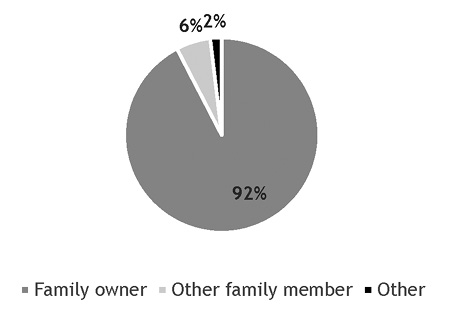

Moreover, 10% of the firms have a board of directors, while 90% are managed by a singular person. This result is justified due to the dimension of most firms. The singular manager is normally the family-owner (92%), as we can see in the following graph.

Figure 3: Type of manager (Percentage of firms)

Comparing with Azores, we can conclude that firms in Leiria region have less firms with board of directors (at least firms that answer to this survey), and more firms are managed by a family owner or other family member (Pimentel et al., 2017). This result goes in line with the idea that a family member manages the firm to avoid agency costs between the principal and manager.

Moreover, 65% of the firm’s managers are the same since the beginning of the firm, and 20% manage the firm for at least half of the firm’s lifetime (and less than total years in activity). Kellermans et al. (2008) argued that family CEO tend to remain much longer in power than those of non-family firms. In fact, the family want to manage the firm not only to avoid agency costs between the principal and manager, but also to assure the family identity and culture in the firm, and due to the difficulty to transmit information to others.

Most of the firm’s managers are male (76%), showing that women still have difficulty to be in the top of the career. Although, this percentage is higher than those of the Fortune 500 in 2018, when only 4.8% of the firms are managed by women.

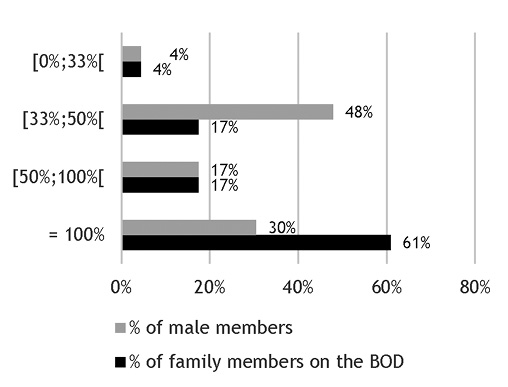

The firms that have a board of director, usually have 3 members on the board (65% of the firms with board of directors). Most of them are family members (61%), as we can observe in the following graph.

Figure 4: Percentage of family and male members on the board of directors (BOD)

The percentage of female in management increase when the firm has a board of directors (the percentage of firms with only male members in the board of directors are 30%), suggesting that personality differences between genders are valorized in these firms.

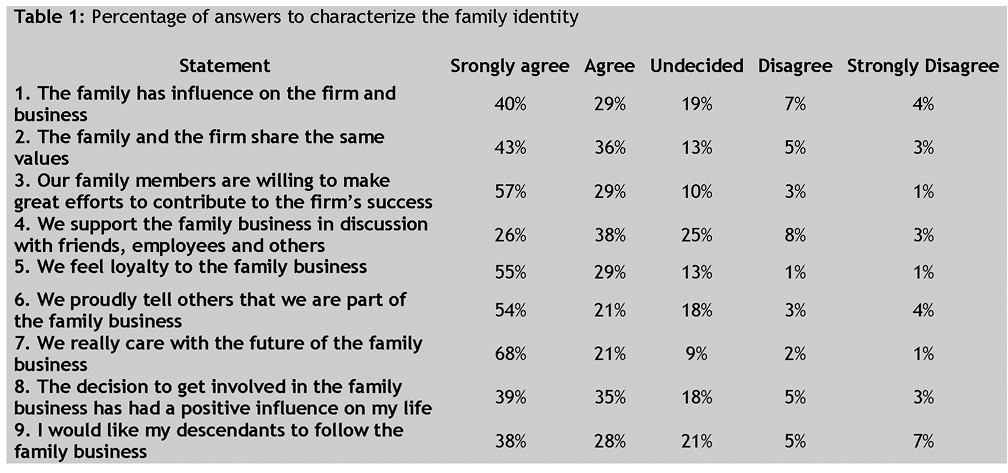

One factor that characterize family firms is its continuity for future generations. The following graph shows in which generation (generations) is the family firm, regarding ownership and management.

Figure 5: Family generation in ownership and management

Most of the firms are owned by the first generation (70%), which can be explained due to the lifetime of the firm. Henrique (2008) argues that firms usually are 24 years in the first generation. As most firms are in the business for less than 30 years, this result is corroborated. 12% of the firms in the sample are owned by the first and second generations, although part of these firms are still managed by the first generation. This result supports the idea that the founder has difficulty to pass information to future generations and decide to sustain the firm’s control. Similar results were found by Pimentel et al. (2017).

Only 16% of the firms that answer the survey in Leiria region are in the second generation, and 2% are owned by both second and the third generations. Finally, only one firm is in the third generation and is own and managed by this generation. The lack of other generations in ownership and control may be justified by the firm’s age, but also by the difficulty of the firm’s succession. According to Associação Empresarial Portuguesa (AEP, 2011 – Portuguese business association) only 50% of family firms survive in the second generation and 20% in the third generation. In Azores there are more firms owned and managed by the third generation, but these firms have a longer lifetime also.

The next graph shows the participation of the family in the firm.

The mean value of family members with active participation in firms located in Leiria region is 2.16, while the number of family members working in the firm is in mean 2.38. These results suggest that most firms have more than 2 family members that decide the firm’s strategy, investment, operational plan, among others. The higher the number of family members, the easier to have the family identity in the business. Moreover, we can see that not all family members are interested in the family business (ate least do not have an active participation on it) or have not opportunity to participate in the business. Similar numbers were found by Pimentel et al. (2017) to Azorean firms.

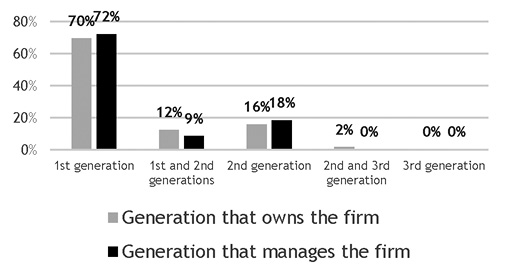

Finally, the last part of the survey aims to identify the family’s identity. Nine sentences were asked to family owners and the respondents should evaluate it on a 5-point scale, where 1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”. The percentage of the answers are in the following table.

Figure 6: Family participation in the firm

Observing the table before we can see that most respondents agree or strongly agree with the sentences. Less than 7% of the respondents disagree with it. These results suggest that the family beliefs, its proud and loyalty to the family business, and the family identity is present in the firm.

The sentence 7 (We really care with the future of the family business) is the one with more percentage of strongly agree (68%). In fact, one factor that characterizes family firms is the firm’s future, not only because the firm is a family’ investment, but also is a source of wealth, employment, and reputation. Although, only 38% of the answers strongly want the descendants to follow the family business (sentence 9). A family firm usually want to pass the firm to future generations. Although, 12% of the answers do not want their descendants to continue with the firm. As there are some new firms, with less than 3 years (16%), the family may have not decided yet the future of the firm, namely who will continue with the firm, if someone will continue. Lisboa (2018) found that diverse firms in Leiria region have not prepared yet the succession of the firm and one of the main reason given was that there is still much time to think about it.

Sentences 3 (Our family members are willing to make great efforts to contribute to the firm’s success), 5 (We feel loyalty to the family business) and 6 (We proudly tell others that we are part of the family business) have more than 50% of the answer: strongly agree. These results suggest that the family see their members as a gain to the firm, contributing to its success, because they see the firm as an extension of the family wealth. Regarding sentence 6 we can see that nowadays family firms are proud to be classified as such. Martins (1999) found that most family firms do not classify themselves as such because they think that family firms are linked to unproductive firms or small firms. The great effort of the media and research to show the benefits of family firms is having results.

Regarding the sentences 1 (The family has influence on the firm and business), and 2 (The family and the firm share the same values) the large majority of the respondents agree or strongly agree with the statement, suggesting that family identity is present in the firm.

More a less 39% of the respondents strongly agree with sentence 8 (The decision to get involved in the family business has had a positive influence on my life). This suggests that not all family owners are really happy with the firm, may be because of the recession period (2008-2014) that have great impact in the firm’s financial situation. Although, only 8% of respondents disagree with the sentence.

Finally, to sentence 4 (We support the family business in discussion with friends, employees and others) most respondents only agree, and 12% disagree. This result suggests that most respondents do not want to speak about the family business may be because the owner wants to sustain the firm’s control and retain its information, leading to the lack of information transparency.

Comparing the answer of this survey with the one done to Azorean firms, we can conclude that the family is less proud and commitment to the firm in Leiria region (Pimentel et al., 2017).

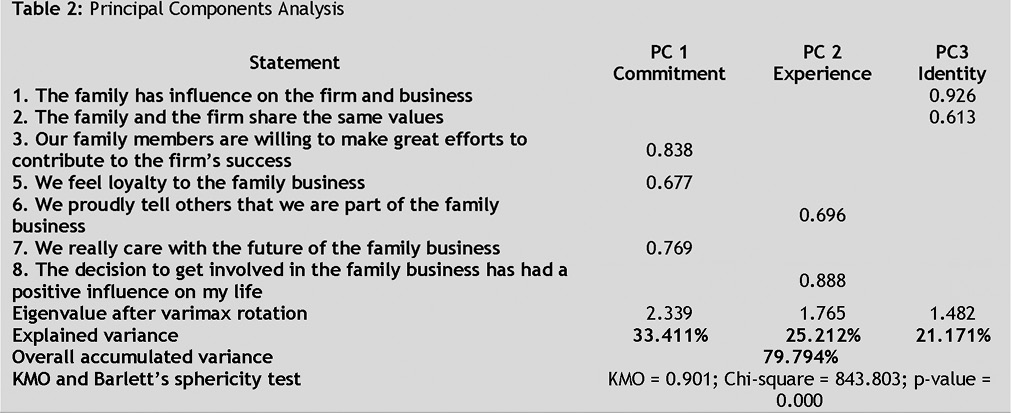

These sentences were factor analyzed using principal component analysis with varimax (orthogonal) rotation. Results are present in the following table.

Sentences 4 and 9 were eliminated from this analysis as these sentences did not have a relevant contribution to explain any principal component.

Three components were proposed and explain 79.8% of the variance for the entire set of variables. The first principal component (PC 1) is explained by the sentences 3, 5 and 7, and express the family commitment in the business. It explains 33.4% of the variance. Sentences 6 and 8 establish the second principal component (PC2), which is related with the family culture. It explains 25.2% of the variance. Finally, the third principal component (PC 3) label family identity links the sentences 1 and 2. The variance explained by this factor is 21.2%.

Conclusion

Family firms are the oldest and more common type of firms all over the world. These firms make an important contribution to the gross domestic product, employment and wealth creation. Therefore, understanding these firms is important. This study aims to design a profile of family firms in Leiria region.

Leiria, even though not been one of the major cities in Portugal, is the third city with higher gross domestic product per residence. Moreover, the percentage of family firms in this region is high, which justifies this study.

Results show that one third of the respondent firms are in the business for less than 10 years, while 38% for more than 20 years. This fact justifies that most of the firms are in the first generation (70%). In the large majority of the respondents, the family owns 100% of the business, and control and manage the firm. Only few companies have a board of directors, normally with three members, and 60% of them are in mean family members. Managers usually are male, but when the firm has a board of directors this has both male and female members. More than two family members actively participate in the firm.

Most respondents agree or strongly agree with the proposed sentences that aim to analyze the family involvement, identity and pride of the family business. We see that the family is involved in the firm and is important for the firm’ success. The family is pride of the family business. The respondents care about the future, but 12% of them do not want their descendants to follow the family business.

Finally, we found three principal components related with family commitment, culture and experience, and these components explain 79.8% of the variance for the set of variables analyzed.

With this study the proposed aims were accomplished. Although, as all the works have some limitations. First, we only have 233 responses, which represent only 5% of the possible answers. This is a major limitation of using surveys. Second, the survey had closed answers and some firms may have given an answer due to a specific situation (for instance, a family without any descendants or impossibility to have descendants may answer that they not agree to pass the firm to future generation). Finally, we analyze only a region. Future researches should focus in other regions to extend results and make comparisons.

References

AEP - Associação Empresarial Portuguesa (2011). Livro Branco da Sucessão Empresarial. O Desafio da Sucessão Empresarial em Portugal. Associação Empresarial de Portugal

Anderson, R., and Reeb, D. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P500. Journal of Finance¸ ٥٨(٣), ١٣٠١-١٣٢٨.

APEF – Associação Portuguesa de Empresas Familiares (2018) retrived from: http://www.empresasfamiliares.pt/.

Astrachan, J., Klein, S., and Smyrnios, K. (2002). The F-PEC Scale of Family Influence: A Proposal for Solving the Family Business Definition Problem. Family Business Review, 15(1), 45-58.

Barontini, R., and Caprio, L. (2006). The effect of family control on firm value and performance: Evidence from Continental Europe. European Financial Management, 12, 689-723.

Basco, R. (2013). The family’s effect on family firm performance: A model testing the demographic and essence approaches. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 4(1), 42–66.

Berle, A., and Means, G. (1932). The Modern Corporation and Private Property, Hancourt, Brace & World, Inc. Copyright, New York (Republished 1968).

Braun, M., and Sharma, A. (2007). Should the CEO also be chair of the board? An empirical examination of family-controlled public firms. Family Business Review, 20(2), 111-126.

Burkart, M., Panunzi, F., and Shleifer, A. (2003). Family Firms. Journal of Finance, 58, 2167–2201.

Chami, R. (2001). What is Different about Family Businesses? Working Paper International Monetary Fund, WP/01/70.

European Family Business (2018). Retrieved from http://www.europeanfamilybusinesses.eu/.

Gersick, K., Davis, J., Hampton, M., and Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts - EUA (1st edition).

Gomez-Mejia, L., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., and De Castro, J. (2011). The Bind that Ties: Socioemotional Wealth Preservation in Family Firms. The Academy of Management Annual, 5:1, 653-707.

Gomez-Mejia, L., Haynes, K., Nuñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K., and Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52, 106-137.

Gomez-Mejia, L., Larraza-Kintana, M., e Makri, M. (2003). The determinants of executive compensation in family-controlled public corporations. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 226-237.

Henrique, C. (2008). A governação nas empresas familiares. Tese de mestrado em Finanças do ISCTE.

INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatísticas – Statistics Portugal. Retrived from https://ine.pt/

Jaskiewicz, P., González, V., Menéndez, S., and Schiereck, D. (2005). Long-run IPO Performance Analysis of German and Spanish Family-Owned Business. Family Business Review, 18(3), 179-202.

Jensen, M., and Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agency Cost and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

JLM Consultores de Gestão, Sargento, A., Lopes, A., and Fernandes, M. (2014). Plano Estratégico - Leiria Região de Excelência. Blue Print Design e Comunicação.

Kellermanns, F., Eddleston, K., Barnett, T., and Pearson, A. (2008). An Exploratory Study of Family Member Characteristics and Involvement: Effects on Entrepreneurial Behavior in the Family Firm. Family Business Review, 21(1), 1–14.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., and Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate Ownership Around the World. Journal of Finance, 54, 471–517.

Lisboa, I. (2018). Sucessão nas empresas familiares e o impacto no endividamento. Evidência para as PME da região de Leiria. Revista de Gestão dos Países de Língua Portuguesa, 17(2), 26-42.

Martins, J. (1999). Empresas Familiares, GEPE -Gabinete de Estudos e Prospectiva Económica do Ministério da Economia, Lisboa – Portugal (1st edition).

Martin-Reyna, J., and J. Duran-Encalada (2012). The Relationship among Family Business, Corporate Governance and Firm Performance: Evidence from the Mexican Stock Exchange. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 3, 106-117.

Miller, D., Breton-Miller, I., Lester, R., and Cannella Jr, A. (2007). Are Family Firms Really Superior Performers? Journal of Corporate Finance, 13, 829-858.

Miralles-Marcelo, J., Miralles-Quirós, M., and Lisboa, I. (2014). The impact of family control on firm performance: Evidence from Portugal and Spain. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(2), 156–168.

Nieto, M., Casasola, M., Fernández, Z. and Usero, B. (2009). Impacto de la Implicación Familiar y de Otros Accionistas de Referencia en la Creación de Valor. Revista de Estudios Empresariales, 2, 5-20.

Pordata (2018). Retrived from: https://www.pordata.pt/.

Pimentel, D., Scholten, M., and Couto, J. (2017). Profiling Family Firms in the Autonomous Region of the Azores. Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, 46, 89-107.

Schulze, W., Lubatkin, M., Dino, R., and Buchholtz, A. (2001). Agency Relationships in Family Firms: Theory and Evidence. Organization Science, 12, 99-116.

Sraer, D., and Thesmar, D. (2007). Performance and Behavior of Family Firms: Evidence from the French Stock Market. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5, 709-751.

Villalonga, B., and Amit, R. (2006). How Do Family Ownership, Control, and Management affect Firm Value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80, 385-417.

Villalonga, B., and Amit, R. (2008). How are U.S. family firms controlled? Review of Financial Studies, 22(8), 3047-3091.

Villalonga, B., Amit, R., Trujillo, M., and Guzmán, A. (2015). Governance of Family Firms. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 7, 635-654.

Ward, H. (1987). Structural Power—A Contradiction in Terms? Political Studies, 35(4), 593-610.

Wortman, M. (1994). Theoretical foundations for family-owned business: A conceptual and research-based paradigm. Family Business Review, 7(1)