|

|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Revisiting Internal Market Orientation in family firms

Sergey Kazakovab,*

a Programa de Doctorado en Economía y Empresa Universidad de Málaga (Economics and Business Administration Phd. Programme at University of Málaga, Spain)

b Associate Professor NRU HSE – Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russian Federation

Received 08 January 2019; accepted 29 November 2018

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M310

KEYWORDS

Internal Market Orientation, Job Satisfaction; Employee Commitment; Business Performance; Family Business

Abstract The present conceptual paper depicts Internal Market Orientation (IMO) theory development conceptualisation with a contemplation of new conditions, realities and technologies available to modern businesses in service industries. Based on the results of a conceptual study, this study proposes a novel IMO framework which reflects the noted global changes that affects family businesses.

The denoted model introduces novelty variables including Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) and Outsourced Personnel structural constructs. They avail to measure the effect of IMO implementation on job satisfaction and employee commitment that, in their turn, exhibit a positive impact on business performance in service industries.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M310

PALABRAS CLAVE

Internal Market Orientation, Job Satisfaction; Employee Commitment; Business Performance; Family Business

Revisiting Internal Market Orientation in family firms

Resumen The present conceptual paper depicts Internal Market Orientation (IMO) theory development conceptualisation with a contemplation of new conditions, realities and technologies available to modern businesses in service industries. Based on the results of a conceptual study, this study proposes a novel IMO framework which reflects the noted global changes that affects family businesses.

The denoted model introduces novelty variables including Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) and Outsourced Personnel structural constructs. They avail to measure the effect of IMO implementation on job satisfaction and employee commitment that, in their turn, exhibit a positive impact on business performance in service industries.

Introduction

The effects of marketing concept implementation in family businesses is a perspective research topic which has been underestimated by academia to date (Zainal et al., 2018). The marketing concept is about a customer centred business paradigm, which emphasises the development and promotion of products and services demanded by consumers (Zhou et al., 2009). The firm that delivers products and services with higher quality to consumer markets usually receives higher levels of customer satisfaction and loyalty resulting in higher revenues for the firm (Narver and Slater, 1990; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990). In other words, the key to success in business is value creation and its delivery to customers (AMA, 2007). Such lemma has been agreed by both academic and business communities. However, there is an issue of the proper marketing concept execution (Kazakov, 2016). This is a matter of common management concern particularly in the context of the family business (Brück et al., 2018) because family business is considered as an important contributor to the national economy (Zainal et al., 2018). Although the marketing paradigm per se is known as a philosophical foundation for business execution in a competitive world, nevertheless, it is noted as something not specific and tangible. Hence, there is a necessity to support the marketing paradigm with a certain way of proper application (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990).

To tackle this challenge, the notion of Market Orientation (MO) was conceptualised by scholars and accepted by practitioners more than thirty years ago as a result of seeking the new marketing concept. It was expected to equip businesses with the tools to achieve greater customer satisfaction that would ultimately lead to better business performance. To date, Market Orientation (MO) is a renowned and profoundly studied yet developed concept in the modern marketing management (see Narver and Slater, 1990, 2000; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990, Kohli et al., 1993; Eccles, 1991; Deshpande et al., 1993; Day, 1994; Farrel and Ozckowski, 1997; Pelham, 2000; Kara et al., 2005; Kirca et al., 2005; Kazakov, 2012, 2016).

MO was later rethought as an integral construct of two basic constituents inclusive of External Market Orientation (EMO) and Internal Market Orientation (IMO). From the enterprise perspective, IMO implements marketing tools and techniques targeted at the organisation employees whilst EMO focuses on the external marketing actors (Lings and Greenley, 2009). IMO received some attention from academia recently but to date, this stream of research is in a paucity. There are certain imperfections in the current state of IMO theory that become visible from the angle of the new economic conditions and business realities currently faced by the family firms. Until most recently, most IMO studies have been aimed to determine its antecedents rather than attempted to measure the impact of IMO implementation on business performance (Gounaris et al., 2009; Lings and Greenley, 2009; Ordanini and Maglio, 2009; Rodrigues and Carlos Piñho, 2012; Edo et al., 2015). Only a limited number of studies concentrated on gauging IMO consequences including employee job commitment, job satisfaction and loyalty, service quality and customer satisfaction (Tortosa et al., 2009; Tortosa-Edo et al., 2010; Ruizalba et al., 2014) but did not consider the actual business performance metrics of sales and revenue numbers, customer retention or churn rates. Similarly, accumulated research has been monotonously experiencing generalisation issues. It was usually applied to the contexts other than family businesses. Furthermore, a common business practice of third-party contracted or ‘outsourced’ manpower wide utilisation has not been yet considered in IMO studies but this practice has certain implications on family, non-family businesses and their employees as literature witnesses (Velocci, 2002; Munch, 2010; Seklecka et al., 2013; Gilani et al., 2016; Imm et al., 2016). Finally, as the emerging and rapidly developing Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) demonstrate a great impact on all facets of human life and activities (Buhalis and Law, 2008; Mittas et al., 2011), their vast expansion and impact should be both measured in IMO contexts. As Kohli and Jaworski (2017) point out, efficient MO conceptual framework should possess what they call a ‘red thread’ which “(a)… ties the entire concept together and (b) put boundaries on the concept” (2017: 3). We believe that ICT can be deemed precisely as such ‘red thread’ in the development of the IMO framework under this study.

Along with the unveiled imperfections of the general IMO theory, there is a scant array of extant research in the context of the family firms. Marketing is often examined as a business paradigm in the domain of big corporations through its better efficacy and valence are demonstrated by family firms as well (Miller and Le Breton‐Miller, 2006; Micelotta and Raynard, 2011). IMO has been mainly investigated in the context of big companies too with only a few exceptions (Ruizalba et al., 2014; 2015; 2016). These studies, however, investigated only some discrete IMO constructs in family firms environment. The verification of the complete IMO framework elements and their direct effects on the business performance metrics for the family firms is still pending. Then, the comparative family vs. non-family firms studies relevant to IMO are not present in the extant literature. These noted imperfections lead to a vocal demand reconcile IMO model framework, to gauge the antecedents and effects of IMO application in family firms and to posit four research questions of our study, as follows:

RQ1: What organisational behaviour elements, that are adequate to the challenges of the modern digital era, constitute IMO in the context of the family firms?

RQ2: Does IMO positively influence the business performance metrics of the family firms?

RQ3: Is there a difference in IMO concept implementation and its effects in the domains of family and non-family businesses?

RQ4: Do family firms, that have a higher level of IMO implementation, have better business performance metrics than family firms with a lower level of IMO implementation?

These research questions determine the purpose of the study which is threefold. First, we develop a novel IMO conceptual framework under this study which addresses the noted issues in IMO theory. We build a model that incorporates ICT as a cementing ‘red-thread’ heeding the recommendations of MO founders (Kohli and Jaworski 2017). This paper posits ICT as an element that links all the components of the modernistic IMO concept together. Based on the accumulated literature, we revisit the most recent advancements in IMO theory and justify the manifested propositions for IMO conceptual framework improvement. Second, we introduce additional business performance metrics as an ultimate and desired consequence of IMO implementation in family businesses and also consider additional covariate variables including outsourced personnel as many family business organisations face this reality in their routine. Finally, we develop a research methodology and design for an adjacent study that will help to secure empirical evidence for the posited IMO conceptual model resulting from this study.

In order to accommodate the accomplishment of these research objectives, we lean on the literature pertinent to ‘roots’ studies and most notable contemporary IMO themed papers. We also encompass extant literature from other academic areas, those that examine ICTs influence on business organisations. Research stream relevant to the studies of how outsourced employees influence the working environment in business organisations is also on our agenda. In order to develop a novel IMO model framework, we also employ scientific methods of induction and deduction using the data obtained following the meetings, conversations, and observations relevant to practical businesses. This data aids to accumulate knowledge and understanding of the modern family firms business realities resulting in consideration and inclusion of certain proposed concept elements.

This research is important to both general marketing and family firms literature. It contributes to the general IMO theory by the introduction of new variables. Incorporation of outsourced personnel variable will demonstrate if the job satisfaction of regular employees is affected by it. Then, the paper determines the effects that ICTs produce on every aspect of IMO implementation in the family firms context. This research is significant for the literature pertinent to family businesses because it outlines the empirical study aimed to build evidence that family business organisations are more prone to IMO deployment than non-family firms. This research possesses interest for both academia and practitioners as it affirms the positive IMO outcomes for the business performance of the family businesses. Completed research results and findings will generate, in our belief, the interest for business practitioners who can successfully apply IMO practices in their firms and furthermore effectively fine-tune internal marketing management to the present-day realities.

The rest of this paper is organised in three sections. In the literature review, we analyse the current state of MO general science and bridge it to the analysis of the available research relevant to the most notable papers relevant to IMO studies. Like common academic logic, literature review and completed research analysis ground an origin for hypotheses formalisation that will then follow in this paper. We resume with a proposition and justification of the conceptual framework that we named iIMO accompanied by the research methodology and design for the next research empirical phase where our assumptions will be hopefully validated. We conclude the paper by presenting theoretical contribution at this point of research supplemented by a discussion of possible limitations and concerns that may arise following the execution of the study.

Market Orientation roots. External and Internal Market Orientation

The core MO philosophy signifies its external vector and mainly targets outer marketing environmental actors including competitors and customers. Nevertheless, the earliest approaches to MO already contained internal business components that were deemed crucial for the successful implementation of MO in practice too. MO was initially conceptualised as a combination of a number of both internal external organisational behavioural components in MKTOR (Narver and Slater, 1990) and MARKOR

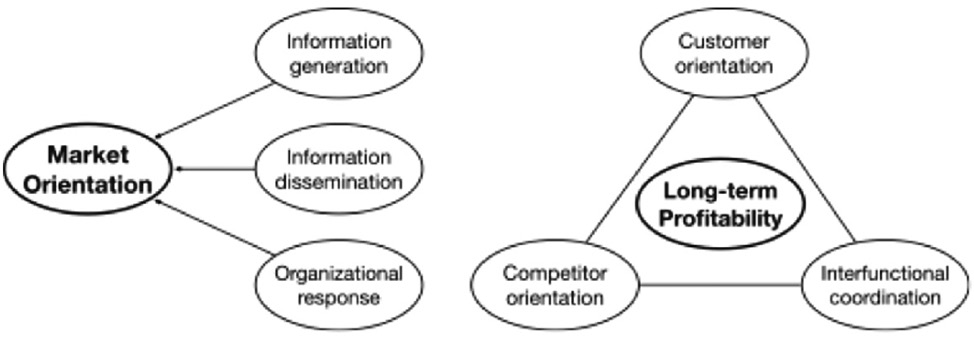

Fig.1. MARKOR (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990) (left) and MKTOR (Narver and Slater, 1990) (right) Market Orientation Models

(Kohli et al., 1993) models (Fig.1). Until recently, both MKTOR and MARKOR models have been profusely referred and cited in the academic literature dedicated to the numerous MO research questions.

Whilst both MARKOR and MKTOR models incorporate internal behavioural components of the organisation, they diverge in organisational focus. MARKOR concept is generally about how well the firm manages the data and how accurately the decisions are made based on thorough data analysis (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990). In contemporary marketing management concept, it is often noted as ‘data-driven marketing’ (Jeffery, 2010). MARKOR model received some criticism recently because of its solitary focus on antecedents of MO, rather than on its consequences and benefits that can be yielded by business organisations as well as due to its complexity (Pelham, 1993; Gabel, 1995). In MKTOR model, the emphasis is made on the internal organisational alignment amid various departments with a focus of impact on external market actors (Narver and Slater, 1990). Unlike the concept of MARKOR, this particular model features ‘Long-term Profitability’ as an ultimate goal for MKTOR implementation as its anticipated consequence. MKTOR model received less critique in the literature so far, though some researchers noted that it has less predictive power and thus less useful for gauging the levels of MO in the organisation (Rojas-Méndez and Michel, 2013).

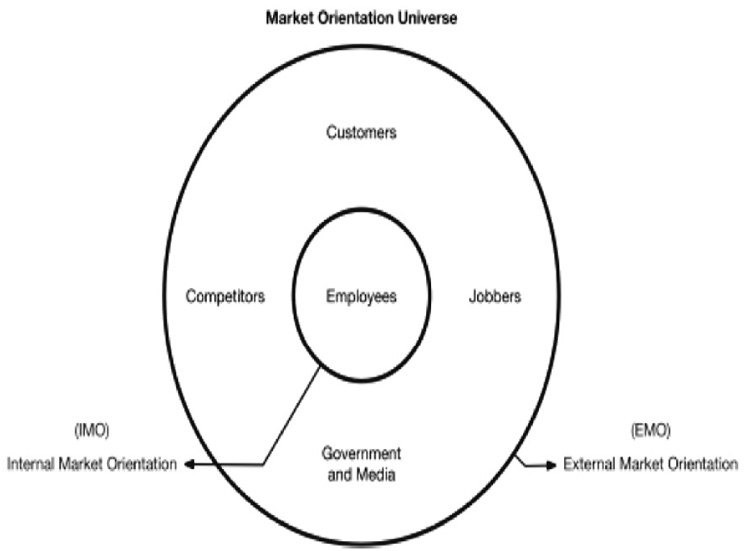

MARKOR and MKTOR together take the onset from the internal environment of the organisation but are mostly headed towards the external marketing environment actors, namely competitors and customers. Although ‘Organisational Response’ construct found in MARKOR model can also be discerned for internal marketing purposes, but according to the context of the Kohli and Jaworski (1990) it had an unambiguous external essence. Hence, the necessity to distinguish MO concept based on its focus arose shortly in academia. This call was described later by succeeding scholars who posited the bifurcation of MO universe into External Market Orientation (EMO) and Internal Market Orientation (IMO) (Fig.2).

From the perspective of the business organisation EMO is deemed as a powerful mean of value exchange with external entities including customers, intermediaries, service companies and other engaged market environmental actors (Kara et al., 2005). Conversely, IMO focuses on marketing actors within enterprise borders by the implementation of the marketing tools and techniques primarily targeted at those actors, namely organisation employees (Gounaris, 2006; Lings and Greenley, 2009). Within the remaining paragraphs of the literature analysis, we will solely contemplate the essence and extant studies in the domain of IMO, which is a scope of the present study.

Internal Marketing or Internal Market Orientation?

Internal marketing (IM) is noted as a predecessor of IMO and was often examined apart from the EMO framework and general MO paradigm in the past (Sasser and Albeit, 1976; Berry, 1981; George, 1990; Piercy, 1995; Gummesson, 1997). Since the general MO concept has received broad recognition and acceptance in the academia, the notions of IM and its réplicas such as ‘Internal Customer Orientation’ were adopted and upgraded to a broader IMO framework to exhibit the close chained links with the paradigm of MO (Lings, 2004). It does not mean, however, that the notion of IM completely disappeared from the academic domain.

Fig.2. Market Orientation Universe constituents of Internal Market Orientation and External Market Orientation

Some scholars still insist on IM in their respective studies and use to examine it alone and isolated from the organisation’s outward marketing according to the research objectives set for their researches (Hernandez-Diaz et al., 2017). Moreover, literature unveils that IMO is often studied through two basic perspectives that approach IMO either as corporate culture or consider it as organisational behavior (Domínguez-Falcón et al., 2017).

Synopsis of the recent Internal Market Orientation key studies

Recent IMO studies tended to concentrate on its antecedents, conceptual elements, and operationalisation. The latter typically pertained to an array of activities that enable and enforce IMO implementation in the business routine. The modelling of IMO constructs relied on many recognisable attributes inherited from classical Narver and Slater’s MKTOR and Kohli and Jaworski’s MARKOR approaches to MO. These transferred MO→IMO grounds, however, received different names and sometimes meanings once applied to IMO due to scholars’ willingness to reflect a divergent nature of IMO.

Thanks to this, IMO has been recently manifested as a separate framework with its unique compounds but at the same time, it is posited as an antecedent of EMO thus appears to be an integral part of MO, as literature suggests (Grönroos, 1997; Varey and Lewis, 1999; Conduit and Mavondo, 2001; Gounaris, 2006). This was made in order to retain the basic conceptual idea of MO in application to IMO to keep the integrity of MO theory as well as to omit the possible misguiding theoretical offsets.

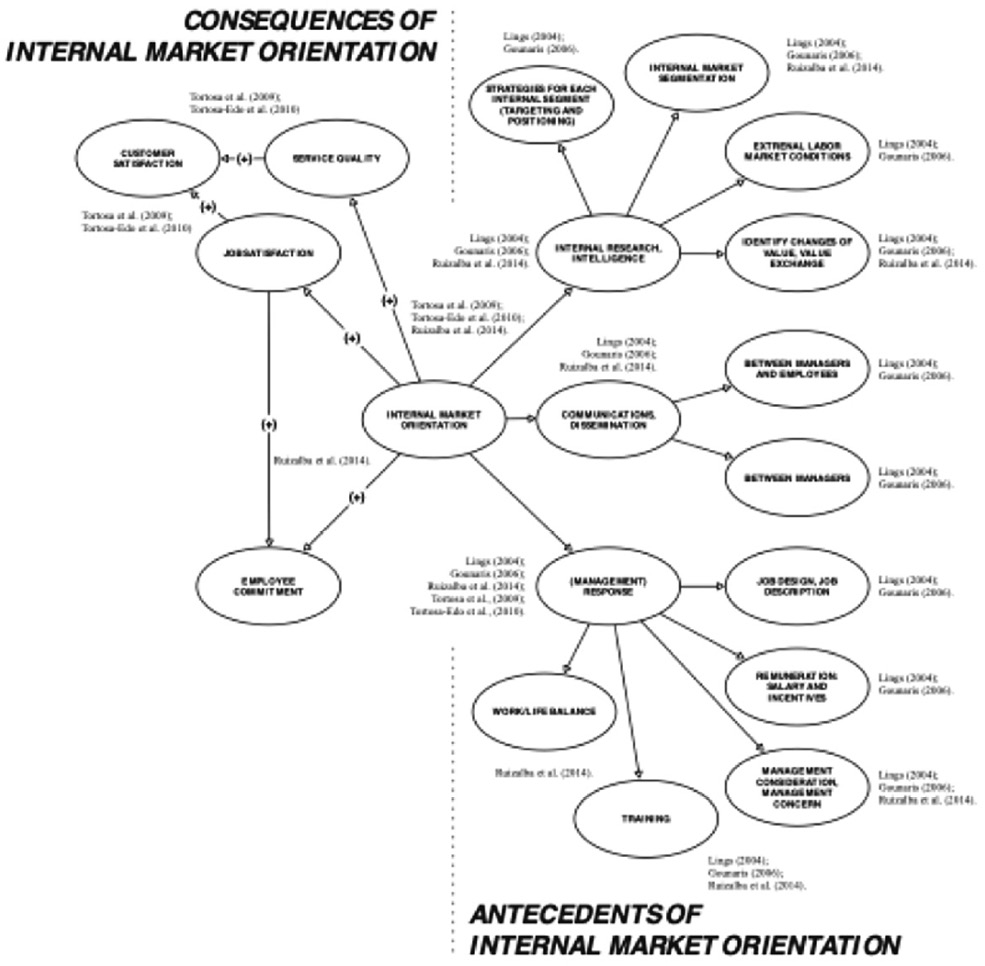

Extant IMO conceptual model frameworks, found in the literature, are inclined to follow the logic of MARKOR concept (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990) applied to the internal organisation environment context. However, they vary one from another as literature unveils (Fig.3). The antecedents of IMO, or organisation behavioural activities, typically contain three theoretical constructs and are inclusive of (1) Internal Market Research (Lings, 2004) also referred as Internal Intelligence Generation (Gounaris, 2006) or Intelligence Generation (Ruizalba et al., 2014), (2) Communications (Lings, 2004) or Internal-Intelligence Dissemination (Gounaris, 2006), Internal Communication (Ruizalba et al., 2014), or Dissemination (Tortosa-Edo et al., 2010) that both also can be formal or informal (Links and Greenly; 2010; Tortosa et al., 2009); and, finally, (3) Response (Lings, 2004; Tortosa et al., 2009; Tortosa-Edo et al., 2010), Response to Internal Intelligence (Gounaris, 2006) or Response to Intelligence (Ruizalba et al., 2014).

These and other MO studies per se mainly had commitments to scrutiny solely a set of IMO determinants, whilst some studies were extended to measure IMO constructs associations with the ultimate output dependable variables, e.g., customer satisfaction and covariances between IMO factors. Furthermore, scholars’ interest in the IMO research surged in the first decade of the XXI century but then gradually declined. Hence, the IMO paradigm may need a re-thinking given an obvious need for a new era specifics consideration because these changes are impacting businesses, economies, and societies on the globe. This would deliver a cutting edge to the concept of IMO. Then, new technologies, globalisation and opposing isolationism, apparent changes in experience economy (Pine and Gilmore, 1998) followed by adopted labor legislation, prosumerism phenomenon as an advance in consumer behavior and their amalgamated effect on social well-being, emerging issues of work-life balance, visibly expanding utilisation of outsourced and out-staffed manpower in service organisations all together should be examined and addressed as construct and moderating variables in IMO model developed under the proposed study. The vast expansion if ICTs technologies and their effects on IMO should also be considered in the form of a ‘red thread’ which help to merge all IMO conceptual model components.

Fig. 3. Aggregated IMO ‘big picture’ conceptual model based on extant literature

Therefore, in a context of the family firms:

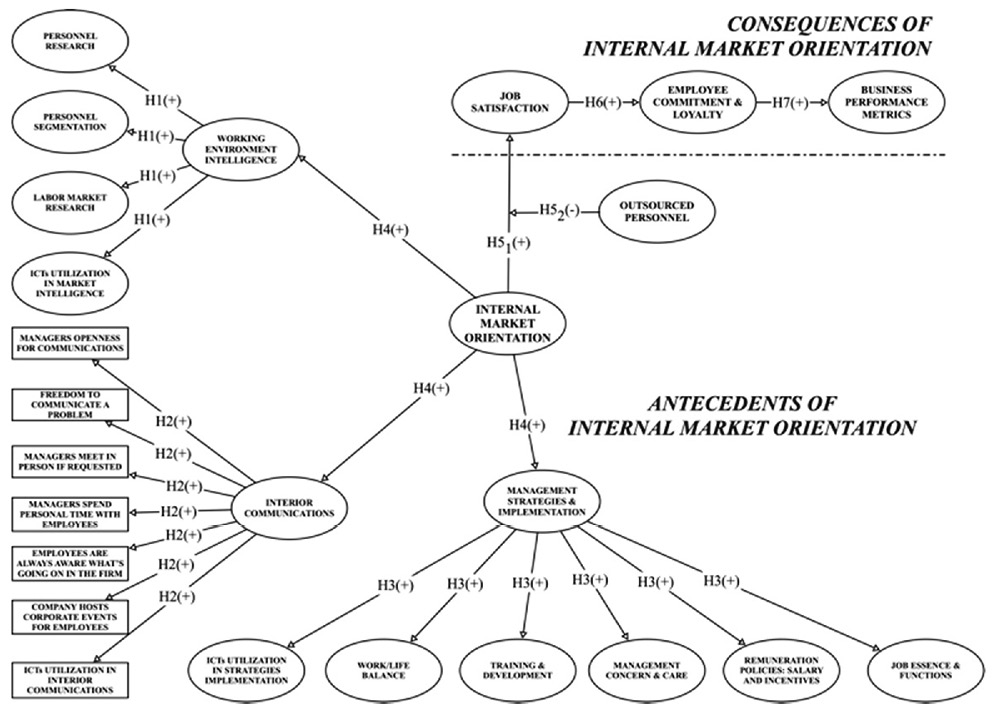

H1: Personnel research and segmentation, external labor market research all together reinforced by ICTs application are sub-measurements of Working Environment Intelligence creation;

H2: Internal communications between managers, between managers and employees, between employees, between the HR department and employees, all together reinforced by ICTs application are sub-measurements of Corporate Interior Communications;

H3: Job essence and functions, remuneration policies, management concern and care, training and development, work/life balance all together reinforced by ICTs application are sub-measurements of Management Strategies and their Implementation;

H4: Working Environment Intelligence, Interior Communications, Management Strategies, and Implementation are integral constructs of Internal Market Orientation.

Internal Market Orientation in the context of family firms

IMO has a complicated essence in the family firms business. Some family firms employ solely family members whilst others may also have personnel who are not the members of the family owning the business. In family firms, there is an overlay of professional and family belonging positions (Ruizalba et al., 2016). Internal relationship between relatives, family events and resulted emotions may impact the working environment of the family business. Non-family employees may be mentally impaired if these emotions are not controlled. Rational economic decisions in family firms may be affected by social and emotional valence of family members (Brück et al., 2018).

Researchers point out that family members are expected to demonstrate a higher commitment to the business than other employees (Distelberg and Sorenson, 2009). At the same time, family members may enjoy more privileges in comparison with contracted professionals employed by the same organisation. This may cause egocentric conduct from an employee belonging to the family who owns the business (Prencipe et al., 2014). Family members also have more flexibility in the working environment but at the same time have more difficulty to isolate their family life from the work (Stafford and Tews, 2009). These noted peculiarities depicting the nature of the internal environment in this type of business organisations should be considered by the IMO studies in the context in the family firms.

Some amount of IMO implementation in family firms research can be found in extant literature. A number of studies examined Work-Life-Balance (WFB) effects on employees job satisfaction and work commitment. One study, in this respect, determined a medium level of WFB presence in family firms. It found the positive influence of WFB on job satisfaction and employee job commitment. Consequently, the medium WFB scores explained the medium output values of the employees’ perception of satisfaction and commitment to their jobs. This study also defined the uneven level of WFB implementation in family firms. Researchers determined three distinct clusters low, mid and high WFB presence in this respect. Higher WFB scoring firms had higher job satisfaction and employee commitment, as the study demonstrated (Ruizalba et al., 2016).

Other studies unveil a broader picture by gauging the effects of more complex IMO structures referred as strategic assets pertaining to family businesses. Strategic assets of HR policies and internal organisational capabilities are relevant to Management Strategies in the IMO framework (Fig. 3). They significantly improve the business performance of the family firms according to these studies (Thrassou et al., 2018; Zainal et al., 2018). IMO is repeatedly underestimated by family business organisations but possesses great potential for business performance metrics improvements of the family firms (Papilaya et al., 2015). Researchers noted that this potential is conditioned by better information dissemination, mutual commitment and the speed of response to changes in the family firms (Zainal et al., 2018). These organisational behaviours are common to this kind of firms because of their family nature and size nevertheless that family firms may not be necessarily small organisations (Thrassou et al., 2018).

Following the review of IMO studies in the context of the family firms, it becomes obvious that a number of publications relevant to IMO and family businesses is scant. The accumulated research is noted to be fragmented as it has examined just a number of separated IMO elements. It also measured the consequences following their application whilst omitting the entire IMO conceptual framework. To address these imperfections, in our belief, the consequences of IMO implementation for the family firms have to be measured and thoroughly explained. As noted above, some recent studies (Ruizalba et al., 2016) measured some of the IMO elements (WLB) effects on family firms business performance. We need to shed more light on it and to assert the significance of entire IMO concept implementation outputs to the family business performance and its improvement. IMO implementation produces a domino effect where the utter financial business performance metrics (e.g., sale volume, etc.) are mediated by transitional dependent variables. As previous studies pointed out, those transitional variables in the IMO domain are job satisfaction and employee commitment (Rodrigues and Carlos Piñho, 2012, Edo et al., 2015). Consequently, it would be beneficial for the IMO theory to measure the first-order effects of IMO implementation. Hence, we posit the next research hypotheses as follows:

H51: Internal Market Orientation delivers a positive effect on Employee Job Satisfaction.

It was noted in the extant literature, that commonly extensive usage of third-party contracted or outsourced manpower utilised by family firms, has not been considered in IMO studies to date. According to the literature, this practice has certain implications on businesses and employees (Velocci, 2002; Munch, 2010; Seklecka et al., 2013). Outsourced personnel is perceived as a potential threat to regular employees, who fear the possible replacement of their function or position (Gilani et al., 2016). These fears grow substantially as family firms will use more outsourced manpower in the future (Imm et al., 2016). Outsourced employment might result in a reduction of regular employee job satisfaction in the family firms. We need to confirm it and thus posit a following hypothesis:

H52: Outsourced Personnel contracting reduces the positive effect of Internal Market Orientation on Employee Job Satisfaction.

A stream of recent studies have investigated the IMO impact on a limited number of its consequences. In this regard, Employee Job Commitment was often gauged as such consequence in an array of publications (Lings and Greenley, 2009; Ordanini and Maglio, 2009; Gounaris et al., 2009; Rodrigues and Carlos Pinho, 2012; Edo et al, 2015). Nevertheless, these effects were not determined in the context of family firms, thus:

H6: Employee Job Satisfaction produces a positive impact on Employee Job Commitment and Loyalty in family business organisations.

Moreover, IMO impact on the ultimate business performance metrics, namely company sales, profit, customer churns and customer base increase has been studied neither in the context of the family firms nor in the context of the general IMO theory. However, this research was completed in the domain of the External Market Orientation (EMO) (Kazakov, 2012, 2016). In thus study, we propose to investigate whether IMO implementation may improve business performance , thus:

H7: Employee Job Commitment and Loyalty delivers a positive effect on the business performance of the family firms.

The specifics and the nature of family business both require a different approach to the IMO implementation than in non-family firms. Until most recently, non-family firms have received more attention from the IMO researchers. The extant literature is amassed by the studies that were accomplished in the context of the regular middle and big size service companies (Lings, 2004: Gounaris, 2006). Extant IMO theory is built around this kind of organisations. Existing IMO frameworks currently are relevant to non-family businesses. Family firms are a big and important constituent of the global economy (Astrachan and Shanker, 2003). They have an internal environment that varies from non-family firms (Ruizalba et al., 2016). Thus, it would be beneficial for the IMO theory development to investigate the differences in IMO implementation and its outputs between family and non-family firms. Consequently, the following hypothesis can be posited:

H8: There is a difference in IMO concept implementation and its effects in the domains of family and non-family businesses.

Research methodology proposition

Following the literature review and detected gaps in the extant IMO theory, the need for its further development is evident. Firstly, IMO theory assets have to be re-evaluated in accordance with the practicalities pertaining to the modern era. The established IMO theoretical framework and its structural constructs namely Internal Market Research, Information Dissemination and Management Response should receive a ‘sync’ or revitalisation. This will allow to revamp IMO theory in order to make it more adequate and aligned to the modern state of the family firms. Secondly, we expect to contribute to IMO theory by an amalgamation of revamped and enriched IMO sub-constructs into a single IMO framework. IMO impact on business performance factors will be hypothesised and tested in three ways: (a) direct effects; (b) sequential model where Job Satisfaction and Employee Loyalty (Commitment) are deemed as moderating variables of the IMO influence on Business Performance; and (c) consideration of the variable accounting the outsourced or labor utilisation that might produce effects on the results of IMO implementation in the family firms.

The consideration of the MO moderating variables was initially suggested by the earliest MO studies and were referred as ‘supplier side moderator’ effects on Market Orientation (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990) but later this call remained forsaken in the following research. While the process of hypothesised IMO model development under the present study we also will follow the counsel of the MO founders to keep the framework as parsimonious as possible with a utilisation of the fewer components where possible (Jaworski and Kohli, 2017).

iIMO theoretical framework

Based on the literature review, research purpose and objectives we now can point the iIMO conceptual framework. iIMO is grounded on the preceding and recognised contributions in the recent research made by Lings (2004), Gounaris (2008), Gounaris and Greenley (2009), Tortosa et al., (2009); Tortosa-Edo et al., (2010), and Ruizalba et al., 2014 with a suggestion of additional exogenous (antecedents) and endogenous (consequences) variables supposed to attain an empirical evidence following the results of the data analysis (Fig.4).

The manifested iIMO model contains several novelties expected to initiate the academic discourse and to be accepted as the author’s contribution to the theory of IMO. First, as recommended by Jaworski and Kohli (2017), the model bears a ‘red thread’ (Jaworski and Kohli, 2017: 3), e.g. a common conceptual element which ‘runs through the components’ (Jaworski and Kohli, 2017: 3) or all other iIMO constructs in the proposed structural model. In our case, it is about the Information and Communication Technologies or ICT. A number of recent studies emphasised ICT deployment and utilisation in personnel management resulting in improvements of processes and business performance (Aksin et al., 2007; Mithas et al., 2011; Palacios-Marqués et al., 2015; Popa and Soto-Acosta, 2016; Bondarouk et al., 2017). The existing literature provides scant references to ICT utilisation in IMO concept implementation thus ICTs should be addressed and examined as a proxy iIMO ‘red thread’ component in the conceptual model proposed under the present study. This is the reason why the posited iIMO conceptual framework received an ‘i’ prefix as it reflects its technological nature determined by our vision of heavy ICT utilisation in the contemporary internal market orientation.

Fig.4. Theoretical Internal Market Orientation (iIMO) measurement and structural model framework including developed research hypotheses

Second, it is intended to examine the mediating effect of outsourced manpower and on job satisfaction perceived by the full-time employees in small and family service business organisations. Part-time and outsourced employees have become an important factor in service industries (Gilani et al., 2016) as businesses strive for efficiency increase by personnel costs optimisation (Favreau et al., 2007). Scholars point to tension between part and full-time employees which may emerge following the onset of outsourced manpower utilisation in the family firms (Velocci, 2002) that lead to reduction in job satisfaction (Munch, 2010; Seklecka et al., 2013; Imm et al., 2016) whilst other scholars insist on full-time employees job satisfaction increase (Walker et al., 2009). Hence, this problem should be addressed by a proposed study.

Third, it is important to focus on business performance metrics as output and consequence of the IMO implementation in the context of small and family service businesses. Previous studies in the commonly used lean approach to IMO modelling resulting in quite parsimonious frameworks. They mainly were limited to the IMO conceptualisation and were not targeted to measure its effects or expose its connotations except one study in the literature review that measured the impact of IMO operationalisation on job performance and employee commitment (Ruizalba et al., 2014). Other studies addressed the customer satisfaction as an outcome of IMO (Tortosa et al., 2009) or intrinsic organisational and job performance (Tortosa et al., 2009; Fang et al., 2014; Gyepi-Garbrah and Asamoah, 2015; Babu and Kang, 2016) which is scantly linked to the specific business performance metrics. The proposed framework is deemed to fill this gap in IMO theory.

Finally, we speculate on the realignment of some causal paths between certain outcomes within the suggested iIMO model. Ruizalba et al. (2014) suggested that Employee Commitment is directly resulted by IMO operationalisation and grounded this finding based on Gounaris (2006), Lings (2004), Lam and Ozorio (2012). This can be certainly accepted but, however, the array of studies dedicated to holistic MO paradigm and ‘satisfaction-loyalty’ marketing academic literature posit that satisfaction is a prime consequence of MO that consequently drives loyalty (Fornell et al., 1996, Hult et al., 2017; Sleep et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2015) or, in other words, satisfaction is a prerequisite of the customer ‘future loyalty’ (Hult et al., 2017:38). The renowned customer satisfaction and loyalty ACSI (American Customer Satisfaction Index) concept is built around the same idea (Fornell et al., 1996). The present study will examine the feasibility and relevance of ‘customer satisfaction → customer loyalty’ approach transfer to ‘employee job satisfaction → employee commitment’. Under this cover, we speculate that job satisfaction is a mediating variable between the iIMO effect on employee loyalty to the family firm. This study, if accomplished, will provide a sophisticated rationale for each and every suggested hypothesis grounded on the relevant literature. Further data collection and analysis will aid in the verification of the proposed hypotheses.

Data collection and analysis design

In short, the empirical research process will roughly consist of three key stages: (A) qualitative interviews with industry experts, family business owners and managers to validate the established and hypothesised model variables with an estimated number of 20 in-depth interviews in a research setting small and family service business sector in Russian Federation on behalf of proposed iIMO framework, its variables, questionnaire and other research tools fine-tuning and rectification; (B) empirical quantitative study in small or family businesses in a form of personal survey using the convenience sampling of 400 participants in a research setting of the family firms in Russian Federation for data collection; and (C) data analysis aimed at obtaining an empirical evidence for the proposed iIMO model and concept.

(A) Qualitative stage of the study will be plotted with a prime target to meet the following interim research project objectives:

(Ai) In-depth 45-60-minute interviews with 10 industry experts, e.g. representatives of the family business owners and managers with an equal quota for a qualitative study with utilisation of the interview guide elaborated in advance;

(Aii) in-depth 45-60-minute interviews with 10 academicians who pertain to Russian or foreign academic research and teaching institutions and who also specialise and have publications in the field of MO, IMO or relevant research areas with an utilisation of the interview guide elaborated in advance.

The qualitative phase of the proposed research project pursues attaining a dyadic goal. First, in a sub-phase (Ai) it will seek for an acknowledgement of managerial implications, confirm a general interest in research results implementation in routine practice and possibly deliver some interesting industry-related insights that can represent a value for the research project. Second, sub-phase (Aii) will help to verify the research methodology including but not limited to research question, objectives, expected results and limitations, hypotheses and the wording of their statements; variables used in both measurement and structural models; regression paths, variables mediation or/and moderation; research tools, sampling technique, data collection and analysis methods. Aii sub-phase is expected to result in shaping the final overall approach to the research project and its methodology thus appears as an important step in the research and in the entire doctoral thesis preparation.

In the qualitative study the interviewees will be reached and recruited according to the following selection approaches:

Ai → a convenience sampling (Hultsch et al., 2002) method will be exploited by approaching 60 random family firms in Russia (SPARK and RBC databases, 2018); with 10 arrangements for the interview, it is expected to yield a response rate of 17% which lies in acceptable threshold values between 15% and 20% for response rates in the sampling recruiting for the social studies (Mennon, et al., 1996);

Aii → a census sampling method will be applied for in-depth structured qualitative surveying of scholars (Geronimus and Bound, 1998) as the number of academia specialised in MO, IMO and EMO is rather limited to date and thus there will be no apparent necessity to run random sampling procedures by scholar sample extraction from the broader academic community.

The information retrieved following the accomplishment of the qualitative stage (A) of the proposed study is supposed to be a cornerstone for the entire research project. It will facilitate the confirmation of the research methodology hence provide a justification for the research direction as well as (A) will be considered as a powerful proxy for the consecutive stage of the proposed study incorporating quantitative research methods.

(B) Quantitative stage of the research will imply the straightforward methodological process inclusive of the following research activities:

(Bi) survey questionnaire production including both offline and online forms; the questionnaire will be based on the mockup sheet by Ruizalba et al. (2014) with an add-ons of supplementary questions reflecting novelty iIMO assigned variables that are proposed following the literature review or their alternative forms if the qualitative stage will result in a demand to make certain changes; job satisfaction will be measured based on the approach and scale by Hartline and Ferrell (1996) and employee loyalty measurement will be evaluated on a scale suggested by Rusbult et al. (1988); business performance metrics will be gauged partially based on the calibration approach of Kazakov (2012, 2016) and will imply the study participating employees perception and assessment of sales increase/reduction, customer base loss/retention/growth, business profitability dynamics in their respective organisation within the last fiscal year;

(Bii) the choice of Likert-type 7-point ordinal metric scale validation and justification vs. 3,5,10 point scales (Dawes, 2008; Ruizalba et al., 2014);

(Biii) the pilot run of offline survey engaging 10 dummy participants in order to confirm the overall questionnaire logic, single surveying length, understandability of the utilised questions wording and 1~7 scale answer keys (e.g.,’1~2: completely does not comply with reality ~ 3~5: partly complies with reality ~ 6~7: fully complies with reality) preciseness;

(Biv) determination of the population (universe) in a research setting of Moscow region, Russian Federation with utilisation of SPARK, RBC, 2GIS and other available databases all together keeping a record of 30,000 family businesses (SPARK, 2018);

(Bv) extraction of elements, e.g. descriptive nominal and ordinal variables, pertaining to the general population that will guide the sampling procedure for the quantitative study; at the point of the research planning process to date these sample recruitment factors are deemed to embody both genders, all age groups, all terms of employment and all job positions within the respective family business organisations;

(Bvi) quantitative study sampling procedure will comprise the approach to potential survey participants via employers who will be contacted with a proposition of either sharing the research results or offering a diagnostic pragmatic study aimed at employees’ job satisfaction and loyalty measurement in the specific organisation which may accompany the proposed study and can be built on the same methodology and research tools;

(Bvii) the combination of quota (probability) (Kothari, 2004) and convenience (non-probability) (Mennon et al., 1996) sampling techniques will be employed on behalf of the empirical quantitative study in order to obtain the even data distribution; the first step implies the attainment the commitment of 20 family and 20 non-family firms to participate in the study with assigned quota of 10 ordinary non-management employees per organisation as participants since line employees are considered a prime object of IMO (Tortosa et al., 2009); then, the employer will release an internal announcement about the study and the first 20 employees willing to participate will be selected and interviewed either offline or online according to the expressed preference;

(Bviii) the margin error resulting from the sample size of 400 employees equals 5% according to the formulae (Hazewinkel, 2001); the margin error value of 5% remains in the acceptable threshold and is the most commonly selected by the researchers (Barlett et al., 2001).

As a result of the quantitative stage accomplishment, the undergoing research will be enriched with a data necessary for hypotheses verification and, more importantly, for securing empirical evidence for the proposed iIMO conceptual framework.

(C) This sequential research project stage comprises the data triangulation, validation and analysis utilising appropriate and justified econometric methods available in the specialised computer software SPSS 25.0, Stata 15.0, Lisrel 8.8 and other industry standard packages delivering the worthy capabilities to meet the objectives of the present study.

Data analysis will be accomplished according to the following logic:

(Ci) descriptive statistics and data distribution analysis inclusive of scaled response scores will check the data distribution normality and its goodness of fit exhibiting the acceptable values of kurtosis and skewness (Gujarati, 2002: 147-148) which in return will secure the grounds for the statistical techniques application including SEM partial least squares path analysis (PLSPA) and confirmatory path analysis CFA (Westland, 2015);

(Ci) premature analysis of linkages between iIMO model variables by running two-way Spearman correlation suitable for ordinal metric scales used in the questionnaire, and χ2 (Greenwood and Nikulin, 1996) to test the primitive construct validity;

(Cii) running iIMO model computation using the SEM approach by exploiting the available capability of Stata 15.0 and additional screening computation of the same model in LISREL 8.8;

(Ciii) iIMO model construct reliability verification using the measurements of Cronbach α and Composite Reliability (CR) index, convergent validity verification by Average Variance Extracted (AVE) evaluation; discriminant validity testing done by the gauging of Maximum Shared Squared Variance (MSV) and Average Shared Square Variance (ASV) (Fornelland and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 1998);

(Civ) iIMO model goodness of fit statistics value thresholds evaluation including p-value, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Root Mean Square Residual (RMR), Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) and Normed Fit Index (NFI) ( Hair et al., 1998; Hu and Bentler, 1999);

(Cv) if needed, modification indices will be applied to the iIMO model as this may deliver an improvement to the overall goodness of fit and its statistics.

The data analysis phase of the research project will result in the receipt of the rationale for the hypotheses verification and for generating the base for empirical evidence to the manifested theoretical propositions of the proposed study.

Research methodology delineated hereinabove, in our belief, is quite capable to ensure the smooth and effective research process facilitating designated contributions into IMO theory and development of recommendations mix helpful for business owners and managers in their aspiration for improvements in the business performance of their respective business organisations.

Theoretical contribution and implications for family businesses

The intended study will be accomplished in order to revisit the Internal Market Orientation paradigm in the setting of the contemporary digital era. It will examine how IMO is shaped in the context of the family businesses. This paper has certain theoretical and methodological contributions, and they can be depicted as follows:

1. this study posits a contribution by fostering, advancing and improving the MO and IMO theory and its compliance with the current level of global economic and social development;

2. the results of this study will deliver an enrichment of the IMO model framework by the establishment of its impact on the family firms ultimate business performance metrics via the initial influence of IMO on job satisfaction and employee commitment and loyalty as such sophisticated subjections were not addressed in academic literature before;

3. this paper introduces the novelty factors into the IMO model framework including ICTs and Outsourced Personnel Contracting that exhibit a moderating role in the IMO impact on endogenous variables of Job Satisfaction, Employee Commitment and Loyalty and, ultimately, Business Performance of the organisation. As the essence of IMO effects on business performance is the most important research question in terms of implications for business, this issue is addressed further by this paper;

4. the present conceptual research contributes to the generalisation of the IMO theory as it is substantiated in a setting of the emerging economy;

5. the present paper outlines the methodology for another adjacent study which will have definite implications for small and family service businesses. The adjacent study is expected to deliver empirical evidence for better business performance demonstrated by internal market-oriented organisations in comparison with non-oriented organisations.

Our research has certain implications relevant for family firms. Family businesses need an effective and affordable solution to increase their organisational and business performance. The proposed study will provide evidence to the iIMO efficacy. It will demonstrate how iIMO can improve employee job satisfaction and work commitment. The study will also attribute these organisational performance variables to the ultimate metrics of family firms business performance. Thus, the intended study is important for the family firms owners, managers and HR specialists.

The study will also suggest a set of recommendations for iIMO implementation, including its deployment and improvement. iIMO application will lead to personnel-related costs reduction and to enhancements in the organisational and business performance. The results of the study will also bear importance for employees of the family firms. It is anticipated that the study results will demonstrate what IMO elements improve employee well-being in the working environment. This information may encourage employees of the family firms to discuss the areas of improvement with their management. As a result, it can make employees be more effective at the working place. The study is also beneficial for customers who buy products or service from family firms. When family firms implement iIMO in their working routine it is expected that customer satisfaction may also increase as a consequence of such implementation as demonstrated by previous studies (Tortosa-Edo et al., 2010).

Limitations of the study and avenues for future research

The proposed study will be not without a number of anticipated limitations. First, it will be completed in the context of one country, namely, Russian Federation. It is noted in some studies that Russians tend to be suspicious and reluctant when participating even in anonymous surveys (Diligensky and Chugrov, 2000). They are also noted to deliver socially desirable responses in polls or surveys (Gorshkov, 2010). Second, this context pertains to an environment of the emerging economy. Hence, iIMO measurements may be impacted by the local specifics and thus may produce a certain bias of the research results and reduce overall generalisability of the study.

As noted in the research methodology above, convenience method will be favoured for the sample recruitment within the family firms for data collection. Convenience sampling technique is chosen due to its better suitability for social studies and overall simplicity (Mennon et al., 1996). However, it is noted to possess the disadvantages that are typical for non-probability sampling techniques as the random sample recruitment is not secured in such cases (Etikan et al., 2016). At the point of preparing this conceptual paper for publication, we are unaware of how well the descriptive statistics will be distributed in the sample. The matter of how good the sample will represent the family firms in Russia is a question now too. The offset of the normal data distribution will certainly lead to clear limitations in the usage of designated SEM data analysis technique.

The proposed study is also expected to deliver insights into a sequential series of the studies with respect to identification of IMO antecedents and gauging its consequences for organisational and business performance in the domain of the family business. The future research may be focused on contributions to generalise the findings of the present study based on the research in different countries setting. IMO theory can benefit from comparative country-to-country or industry-to-industry kind of studies in this respect. Successor researchers may be interested in incorporating and testing the additional iIMO model elements, e.g., corporate culture or employer brand. Finally, iIMO elements value dynamics is another interesting topic to consider thus would require longitudinal research of the same sample using a time series study method.

Conclusion

This study fills the paucity in IMO studies in the context of family firms which was determined following the literature review. Preceding studies gave roots to the concept and determined the organisational behavioural components, known as IMO antecedents, that altogether constitute IMO (Lings, 2004; Gounaris, 2006). They also unveiled an important finding that HR management may be successfully carried out by the utilisation of Market Orientation paradigm applied to the internal environment. IMO shifts the Market Orientation focus from external ‘regular’ customers to internal customers or employees. Hence, nevertheless to the apparent differences, employees can benefit from the powers of Market Orientation too in a way how ‘regular’ customers are treated.

Early studies formed a basis and institutionalised IMO concept in the literature. This theoretical foundation is noted as classic and is accepted by academia. Nevertheless, given a speed of changes in the business environment, working relationships, and technological advancements, the classic IMO concept seems partly to erode its adequacy to modernity along with Market Orientation paradigm (Jaworski and Kohli, 2017). This study tackles this challenge by the introduction of ICT as a new exogenous variable and measurement of ICT factor loading in every IMO model construct. It is in line with the most recent studies that found improvements in processes and employee performance after ICT deployment in various organisations (Palacios-Marqués et al., 2015; Popa and Soto-Acosta, 2016). Although ICTs are an important tool to increase operational efficiency for most business organisations, their utilisation is crucial for usually low staffed family firms for processes automation (Consoli, 2012). IMO implementation can be also reckoned as a business process in family firms, hence, it is not an exception in this respect. Thus, our research bridges the existing gap in the theory by examination if ICTs can be a prerequisite to the IMO application.

The most recent stream of research built empirical evidence of IMO sheer effects on organisational and business performance. As extant literature witnesses, IMO improves service quality(Tortosa et al., 2009) and customer satisfaction (Tortosa-Edo et al., 2010). This is done by an increase in job satisfaction and employee commitment following the IMO implementation (Ruizalba et al., 2014). Our research is aligned with this establishment. However, unlike recent studies, this research also examines the mediation of outsourced personnel on job satisfaction in family businesses. It is worth the examination due to the growing utilisation of outsourced and third-party contracted workforce is a noted practice of family businesses(Amit et al., 2008). This may create tension in the relationship between regular and outsourced non-staff employees (Grimshaw and Miozzo, 2009).

Furthermore, we noted a paucity in business performance metrics used to gauge the IMO outputs as a characteristic of the extant literature. Employee job satisfaction, work commitment, and even customer satisfaction tend to be a cogent but still more qualitative type of metrics to depict family business performance. They also are more relevant to organisational performance rather than demonstrate the actual business results in the IMO aftermath. A number of studies were themed with an introduction of more profound business performance metrics but those were relevant to the gauging of general Market Orientation consequences (Kazakov, 2016). Our study addresses this theoretical imperfection and introduces three business performance outputs for iIMO implementation. Being solely quantitative, these metrics, namely dynamics of sales turnover, revenue and number of family firms customers, deliver more plausible information about IMO implementation results.

Organisational and business performance of family and non-family firms have been addressed in a number of previous studies. The literature witnesses that family firms often demonstrate better business performance than non-family businesses (Miller and Le Breton‐Miller, 2006). Researchers explain this finding by a higher grade of commitment and long-term orientation of family firms stakeholders (Allouche et al., 2008). It is noted, however, that most of the previous studies of this topic used solely financial indicators of business performance. We also utilise metrics in our study to gauge financial performance. Additionally, our study employs a customer quantity as a supplementary measurement that depicts how well businesses perform from the marketing perspective. Furthermore, this study is aimed to exhibit a mediating role of IMO implementation in business performance. A bunch of questions arises in relation to it. Does IMO further improve family firms business performance and extends a gap between family and non-family business organisations even if the latter implement IMO too? Or, can IMO implementation by the non-family firms compensate the posited lagging or even equalise business performance if family firms do not execute IMO, etc. By addressing these questions, findings of the proposed study will hopefully feed the discussion around the comparison of family and non-family businesses performance in the relevant literature.

References

Aksin, Z., Armony, M., Mehrotra, V. (2007). The modern call center: A multi‐disciplinary perspective on operations management research. Production and operations management, 16(6), 665-688.

Allouche, J., Amann, B., Jaussaud, J., & Kurashina, T. (2008). The impact of family control on the performance and financial characteristics of family versus nonfamily businesses in Japan: A matched-pair investigation. Family Business Review, 21(4), 315-330.

Amit, R., Liechtenstein, H., Prats, M. J., Millay, T., Pendleton, L. P. (2008). Single family offices: Private wealth management in the family context. Tàpies J. and Ward JL (2008)(eds.), Family Values and Value Creation. The Fostering of Enduring Values Within Family-Owned Business, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Babu, M. M., Kang, J. (2016). Assessing the Impact of Internal Marketing Orientation on an Organization’s Performance. In Rediscovering the Essentiality of Marketing (pp. 429-430). Springer International Publishing.

Barlett, J. E., Kotrlik, J. W., Higgins, C. C. (2001). Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Information technology, learning, and performance journal, 19(1), 43.

Bondarouk, T., Harms, R., Lepak, D. (2017). Does e-HRM lead to better HRM service?. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(9), 1332-1362.

Brück, C., Ludwig, J., Schwering, A. (2018). The use of value-based management in family firms. Journal of Management Control, 28(4), 383-416.

Buhalis, D., Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism management, 29(4), 609-623.

Consoli, D. (2012). Literature analysis on determinant factors and the impact of ICT in SMEs. Procedia-social and behavioral sciences, 62, 93-97.

Dawes, J. (2008). Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used. International journal of market research, 50(1), 61-77.

Day, G.S. (1994). The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), pp. 37-52.

Deshpande, R., Farley, J. U., Webster, F. E. Jr. (1993). Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), pp. 23-37.

Diligensky, G., Chugrov, S. (2000). The West” in Russian Mentality. Office for Information and Press, Brussels Institute of World Economy and International Relations, Moscow, 10-11.

Distelberg, B., Sorenson, R. L. (2009). Updating systems concepts in family businesses: A focus on values, resource flows, and adaptability. Family Business Review, 22(1), 65-81.

Eccles, R.G., Jr. (1991). The Performance Measurement Manifesto. Harvard Business Review. 69(1), pp. 131-137.

Edo, V. T., Llorens-Monzonís, J., Moliner-Tena, M. Á., Sánchez-García, J. (2015). The influence of internal market orientation on external outcomes: The mediating role of employees’ attitudes. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 25(4), pp. 486-523.

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American journal of theoretical and applied statistics, 5(1), 1-4.

Fang, S. R., Chang, E., Ou, C. C., Chou, C. H. (2014). Internal market orientation, market capabilities and learning orientation. European journal of marketing, 48(1/2), pp. 170-192.

Farrell, M.A., Oczkowski, E. (1997). An analysis of the MKTOR and MARKOR measures of market orientation: an Australian perspective. Marketing Bulletin - Department of Marketing Massey University, 8, pp.30-40.

Favreau, M., Miles, M., Hatch, N., Hawks, V. (2007). Outsourcing relationships between American and Chinese companies. In Electrical Insulation Conference and Electrical Manufacturing Expo, 2007 (pp. 348-351). IEEE.

Fornell, C., Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 39-50.

Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., and Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), pp. 7–18.

Gabel T.G. (1995). Market orientation: theoretical and methodological concerns. In Barbara B Stern and George M Zinkhan (eds.). Proceedings of the American Marketing Association Summer Educators’ Conference, Chicago, Il: American Marketing Association, 368-375.

Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J. (1998). Use of census-based aggregate variables to proxy for socioeconomic group: evidence from national samples. American Journal of Epidemiology, 148(5), 475-486.

Gilani, H., Gilani, H., Jamshed, S., Jamshed, S. (2016). An exploratory study on the impact of recruitment process outsourcing on employer branding of an organisation. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 9(3), 303-323.

Gorshkov, M. K. (2010). The sociological measurement of the Russian mentality. Russian Social Science Review, 51(2), 32-57.

Gounaris, S. (2006). Internal-market orientation and its measurement. Journal of Business Research, 59, pp. 432–448.

Gounaris, S., Vassilikopoulou, A., Chatzipanagiotou, K. (2010) Internal-market orientation: a misconceived aspect of marketing theory. European Journal of Marketing, 44 (11/12), pp. 1667-1699.

Greenwood, P. E., Nikulin, M. S. (1996). A guide to chi-squared testing (Vol. 280). John Wiley and Sons.

Grimshaw, D., Miozzo, M. (2009). New human resource management practices in knowledge-intensive business services firms: the case of outsourcing with staff transfer. Human Relations, 62(10), 1521-1550.

Gujarati, D. N. (2002). Basic Econometrics (Fourth ed.). McGraw Hill.

Gyepi-Garbrah, T. F., Asamoah, E. S. (2015). Towards a holistic internal market orientation measurement scale. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 23(3), pp. 273-284.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 207-219). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice hall.

Hartline, M., Ferrel, O.C.(1996). The management of customer contact service employees: an empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing, 60, 52–72.

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], Errors, theory of. Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hu, L. T., Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Hult, G. T. M., Morgeson, F. V., Morgan, N. A., Mithas, S., Fornell, C. (2017). Do managers know what their customers think and why? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(1), pp. 37-54.

Hultsch, D. F., MacDonald, S. W., Hunter, M. A., Maitland, S. B., and Dixon, R. A. (2002). Sampling and generalisability in developmental research: Comparison of random and convenience samples of older adults. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(4), 345-359.

Imm, N. S., Sambasivan, M., and Perumal, S. (2016). Cultural Changes in Total IT Outsourcing: Dutch-American and Dutch-German. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities.

Jeffery, M. (2010). Data-driven marketing: the 15 metrics everyone in marketing should know. John Wiley and Sons.

Jaworski, B. J., Kohli, A. K. (2017). Conducting field-based, discovery-oriented research: Lessons from our market orientation research experience. AMS Review, 1-9.

Kara, A., Spillan, J.E., DeShields, O.W. Jr. (2005). The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Performance: A Study of Small-Sized Service Retailers Using MARKOR Scale. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(2), pp. 105–118.

Kazakov, S. (2012). Market orientation as an effective approach to marketing in service organizations. Marketing and Marketing Research [Rynochnaya Orientatsia kak effectivniy podkhod k organizatsii marketinga na predpriatyiah spheryi uslug. Marketing i marketingovyie issledovania], 91(1), pp. 42-55.

Kazakov, S. (2016). The impact of market orientation levels on business performance results: The case of the service industry in Russia. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 8(3), 296-309.

Kirca, A.H., Jayachandran, S., Bearden, W.O. (2005). Market orientation: a meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing, 69 (2), pp. 24-41.

Kohli, A.K., Jaworski, B.J. (1990). Market Orientation - the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing. 54(2), pp: 1-18.

Kohli, A.K., Jaworski, B.J., Kumar, A. (1993). MARKOR: A measure of market Orientation. Journal of Marketing Research. 30(4), pp. 467-477.

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International.

Lam, D., Ozorio, B. (2012). Linking employee’s personalities to job loyalty. Annals of Tourism Research, 39 (4), pp. 2203–2206.

Lings, I.N. (2004). Internal market orientation: constructs and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 57 (4), 405–413.

Lings, I. N., Greenley, G. E. (2009). The impact of internal and external market orientations on firm performance. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 17(1), pp. 41-53.

Mennon, A., Bharadwaj, S.G., Howell, R. (1996). The quality and effectiveness of marketing strategy: effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict in intraorganizational relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24(4) pp. 299–313.

Micelotta, E. R., Raynard, M. (2011). Concealing or revealing the family? Corporate brand identity strategies in family firms. Family Business Review, 24(3), 197-216.

Miller, D., Le Breton‐Miller, I. (2006). Family governance and firm performance: Agency, stewardship, and capabilities. Family business review, 19(1), 73-87.

Mithas, S., Ramasubbu, N., Sambamurthy, V. (2011). How information management capability influences firm performance. MIS quarterly, 237-256.

Munch, J. R. (2010). Whose job goes abroad? International outsourcing and individual job separations. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 112(2), pp. 339-360.

Narver, J.C., Slater, S.F. (1990). The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability. Journal of Marketing, 54(4), pp. 20-35.

Narver, J.C., Slater, S.F. (2000). The Positive Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability: A Balanced Replication. Journal of Business Research, 48, pp. 69–73.

Ordanini, A., Maglio, P. P. (2009). Market Orientation, Internal Process, and External Network: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Key Decisional Alternatives in the New Service Development. Decision Sciences, 40, pp. 601–625.

Palacios-Marqués, D., Soto-Acosta, P., Merigó, J. M. (2015). Analyzing the effects of technological, organizational and competition factors on Web knowledge exchange in SMEs. Telematics and Informatics, 32(1), pp. 23-32.

Papilaya, J., Soisa, T.R., Akib, H. (2015). The influence of implementing the strategic policy in creating business climate, business environment and providing support facilities towards business empowerment on small medium craft enterprises in Ambon Indonesia. International Review of Management and Marketing, 5(2), 85-93.

Pelham A.M. (1993). Mediating and moderating influences on the relationship between market orientation and performance. Doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University.

Pine 2nd., B. J., Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), pp. 97-105.

Popa, S., Soto-Acosta, P. (2016). Social web Knowledge Sharing and Innovation Performance in Knowledge-Intensive Manufacturing SMEs. In European Conference on Knowledge Management (p. 733). Academic Conferences International Limited.

Prencipe, A., Sasson, B. Y., & Dekker, H. C. (2014). Accounting research in family firms: Theoretical and empirical challenges. European Accounting Review, 23(3), 361–385.

Rodrigues, A. P., Carlos Pinho, J. (2012). The impact of internal and external market orientation on performance in local public organizations. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 30(3), pp. 284-306.

Rojas-Méndez, J.I., Michel, R. (2013). Chilean wine producer market orientation: Comparing MKTOR versus MARKOR. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 25(1), 27-49.

Ruizalba, J.L., Bermúdez G., Rodríguez M., Blanca, M.J. (2014). Internal market orientation: An empirical research in hotel sector. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 38, pp. 11–19.

Ruizalba, J., Arán, M.V., Porras, J.L.G. (2015). Analysis of corporate volunteering in internal market orientation and its effect on job satisfaction. Tourism & Management Studies, 11(1), pp.173-181.

Ruizalba, J., Soares, A., Arán, M.V., Porras, J.L.G., (2016). Internal market orientation and work-family balance in family businesses. European Journal of Family Business, 6(1), pp.46-53.

Rusbult, C. E., Farrell, D., Rogers, G., Mainous, A. G. (1988). Impact of exchange variables on exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect: An integrative model of responses to declining job satisfaction. Academy of Management journal, 31(3), 599-627.

Seklecka, L., Marek, T., Lacala, Z. (2013). Work Satisfaction, Causes, and Sources of Job Stress and Specific Ways of Coping: A Case Study of White‐Collar Outsourcing Service Employees. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries, 23(6), pp. 590-600.

Sleep, S., Bharadwaj, S., Lam, S. K. (2015). Walking a tightrope: the joint impact of customer and within-firm boundary spanning activities and perceived customer satisfaction and team performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(4), pp. 472–489.

Stafford, K., Tews, M. J. (2009). Enhancing Work—Family Balance Research in Family Businesses. Family Business Review, 22(3), 235-238.

Thrassou, A., Vrontis, D., Bresciani, S. (2018). The agile innovation pendulum: A strategic marketing multicultural model for family businesses. International Studies of Management & Organization, 48(1), 105-120.

Tortosa, V., Moliner, M. A., Sánchez, J. (2009). Internal market orientation and its influence on organisational performance. European Journal of Marketing, 43(11/12), 1435-1456.

Velocci, A. L. (2002). Employees creatively fight outsourcing. Aviation Week and Space Technology, 157(8), 48-48.

Walker, M., Sartore, M., Taylor, R. (2009). Outsourced marketing: it’s the communication that matters. Management Decision, 47(6), pp. 895-918.

Watson, G. F., Beck, J. T., Henderson, C. M., Palmatier, R. W. (2015). Building, measuring, and profiting from customer loyalty. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(6), 790–825.

Westland, J. C. (2015). Structural equation models: From paths to networks. (Vol. 22). Springer.

Zainal, H., Parinsi, K., Hasan, M., Said, F., & Akib, H. (2018). THE INFLUENCE OF STRATEGIC ASSETS AND MARKET ORIENTATION TO THE PERFORMANCE OF FAMILY BUSINESS IN MAKASSAR CITY, INDONESIA. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 17(6).

Zhou, Y., Chao, P., Huang, G. (2009). Modeling market orientation and organizational antecedents in a social marketing context: Evidence from China. International Marketing Review, 26 (3), pp. 256-274.