|

|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Private Equity focused on Family Firms & Small and Medium Sized Companies: Review and Science Mapping Analysis of the Recent Scientific Field.

Laura Arteche Buenoa, Camilo Prado Romána*, Antonio Fernandez Portillob

a University Rey Juan Carlos (Spain)

b University of Extremadura. (Spain)

Received 10 August 2018; accepted 19 December 2019

JEL CLASSIFICATION

F21, G11, G24, O16

KEYWORDS

Family involvement; Entrepreneurial Orientation; Product Innovation; Radical Innovation; Incremental Innovation

Abstract Private equity (“PE”) is mostly invested in established firms, of which family firms (“FFs”) are the dominant form. This article reports the recent evolution of the scientific research on the PE focused on FFs and small and medium-sized enterprises (“SMEs” or “the middle-market”). The purpose is to identify the main themes related to the field between 1992 and 2018 and to identify and analyze the major thematic areas throughout the period. The methodology applied is the science mapping analysis, which shows that: (i) published research on the field is concentrated in two main thematic areas: corporate governance-entrepreneurship and innovation-management, and; (ii) there has been an atomization of the research field during the last six years. Throughout this article, the authors develop a more complete understanding of the PE scientific field focused on family owned SMEs and provide suggestions for those looking for alternatives to traditional bank financing.

CÓDIGOS JEL

F21, G11, G24, O16

PALABRAS CLAVE

Implicación familiar; Orientación Emprendedora; Innovación en Productos; Innovación Radical; Innovación Incremental

Capital privado centrado en empresas familiares y pequeñas y medianas empresas: revisión y análisis de mapeo científico del campo científico reciente.

Resumen El capital inversión (private equity) se invierte principalmente en empresas establecidas, de las cuales las empresas familiares son la forma dominante. Este artículo analiza la reciente evolución de la investigación científica sobre private equity centrada en las Empresas Familiares y las pequeñas y medianas empresas (PYME). El propósito es identificar los temas principales relacionados entre 1992 y 2018 y analizar las principales áreas temáticas a lo largo del período. La metodología aplicada es science mapping analysis, que muestra que: 1. la investigación publicada en el campo se concentra en dos áreas temáticas principales: gobierno corporativo-emprendimiento y gestión de la innovación, y; 2. ha habido una atomización del campo de investigación durante los últimos seis años. La investigación realiza un análisis en profundidad para entender la literatura sobre private equity, centrandose en las PYME familiares, ofreciéndose indicaciones para aquellos que buscan alternativas al financiamiento bancario tradicional.

Introduction

The middle-market sector plays an important role in our financial system provided that, and according the European Commission, “SMEs are the backbone of Europe’s economy: they represent 99% of all businesses in the region”. In addition, SMEs have strong difficulties to obtain external funds for growth. The diversification of their financing sources is a key issue to allow room for growth and internationalization today and the PE is, in some cases, the main source of long term financing for them that has lots of advantages against other sources of financing. PE is an effective alternative to traditional financing for private SME as it provides with solid and sustainable business models to better deal with economic cycles. Many FFs are facing succession around the world (Shanker and Astrachan, 1996; Upton and Petty, 2000) and the challenge of ensuring succession of the business is a pressing global phenomenon (PWC, 2012); but PE has largely been ignored as a possible solution (Higashide & Birley, 2002; Howorth, Westhead and Wright, 2004).

FFs are of particular significance for the global economy (IFERA, 2003; Anderson and Reeb, 2003; Morck and Yeung, 2003; Astrachan and Shanker, 2003; Klein, 2000). With more than 14 million family businesses in Europe, their importance to the economy cannot be overestimated. In some countries, they represent anywhere from 55 to 90 percent of all businesses (“European Family Business Barometer”, KPMG and EFB, 2017).

FFs are a heterogeneous group with varying degrees of family influence, differences in size, industry and geography (Chua, Chrisman, Steier and Rau, 2012; Chrisman, Chua, Pearson and Barnett, 2012; Tsang, 2002). Nowadays, ownership and management succession are one of the biggest challenges for FF. However, “many of them do not have the necessary resources and capabilities to grow or to manage generational succession” (Howorth et al., 2004; Shanker and Astrachan, 1996; Sirmon and Hitt, 2003; Upton and Petty, 2000). Succession is the most frequently studied topic in the family business literature (Chua, Chrisman and Sharma, 2003) but the exploration of nonfamily route to succession has not received much attention in the academic literature (Birley and Westhead, 1990; Howorth et al., 2004). According to the PwC Global Family Business Survey 2018, succession and access to financing are between the key challenges for FF over the next two years.

Despite the abovementioned, according to the European Central Bank (November of 2017) “banking products are the main source of financing for European SMEs, while other sources available in the market such as equity (which includes the PE) are hardly considered as a potential source of funds.” But PE represents an alternative source to finance investment opportunities for a wide variety of firms (Martí, Menéndez-Requejo and Rottke, 2013). One possible solution to the succession problems is to open up the family firm’s capital to PE investors (Dawson, 2011).

Several authors like Benavides-Velasco, Quintana-García and Guzmán-Parra (2013) and Voordeckers, Le Breton-Miller and Miller (2014) have shown that finance is not only one of the top areas in family business research but also a growing area. The importance is warrantied since the availability of sufficient financial resources is of critical importance for the FF’s survival and growth (Koropp, Kellermanns, Grichnik and Stanley, 2014).

Simultaneously, the PE activity has become a major focus of study since the late 90s because of the increasing evidence on high performance PE funds, among other reasons. The positive effect generated by PE has been widely studied and demonstrated in the existing literature (Kaplan and Schoar, 2005; Metrick, and Yasuda, 2011; Haro De Rosario, 2013)

Given this evidence, the authors question whether, indeed, PE is a real alternative to bank financing for family owned SMEs and that, in addition, it offers great advantages over other sources of financing.

To solve this question, the authors first consider knowing what the historical evolution of the scientific field of PE focused on this type of companies has been. In order to understand what the most impactful and relevant topics in the field have been in the past and are nowadays, the authors develop in this research paper an empirical analysis of the field through a bibliometric analysis based on the analysis of scientific maps, developing a more complete understanding of the field and discovering current and future research areas relevant to both PEs and family owned SMEs.

This study aims also at making the family owned SMEs aware of the existence and advantages of the use of PE as an alternative to traditional financing and to promote it in the next years. This type of study was suggested by Michiels and Molly (2017).

in their review of Financing Decisions in Family Businesses. As described below, a high level of funds has been raised by middle-market PEs in 2017 and new fundraisings are expected to be closed in 2018, what results in an attractive opportunity for the family owned SMEs looking for speeding up growth in the next years.

Evolution of the scientific PE field focused on FFS and the middle-market between 1992 and 2018

The word “PE” can mean risk capital invested in a wide range of companies and industries: from funds provided to start-ups and privately-owned SMEs to acquisitions of multinational companies and even entire mature publicly-traded companies (Gilligan and Wright, 2010). The scientific study of the PE sector with activity in the FFs SMEs market segment belongs to a relatively recent past: the first article indexed in the Web of Science (“WoS”) appeared in year 1992 and significant volumes of high impact research did not appear until year 2007 (Cumming, Siegel and Wright, 2007; Cumming, 2007; Renneboog, Simons and Wright, 2007). Until then, years 2000 and 2001 were especially productive for the PE due to the boom of both the high-tech and the mergers and acquisitions sectors. Between 2001 and 2006, the European PE houses raised 193,786 million Euros in funds, being 2005 the peak year with 71,771 million Euros raised. The high level of activity of the period occurred in many nations (Wright, Amess, Weir and Girma, 2009a; Strömberg, 2008), culminating in a peak worldwide in 2007.

The onset of the financial crisis from 2008 resulted in a massive fall in deal value worldwide in 2009 as debt markets closed and PE firms set about restructuring troubled and overleveraged portfolio companies. Nevertheless, PE was not just a transitory phenomenon and PE firms have adapted to begin to build a new future (Wright, Jackson and Frobisher, 2010). Since 2010, worldwide PE showed signs of recovery, as the third quarter provided the strongest showing of the market since the financial crisis at an aggregate value of 66.7 billion US$ (Preqin, 2010).

In the following years, there are signs that indicate that fundraising and deal making will be strong in the Europe, the Middle East and Africa region: leading European middle-market PE funds are right now in the process of fundraising. In the last few years fundraising among PE firms has hit record levels and most of surveys suggests this trend is to continue in 2018. The sector is, in addition, under a globalization process.

The methodology: science mapping bibliometrics analysis through scimat software tool

In bibliometrics, science mapping analysis (“SMA”) is designed to display the structural and dynamic aspects of scientific research, to determine the scope of a research field and to quantify and visualize the detected subfields by means of co-word analysis or document co-citation analysis. It is focused on monitoring a scientific field and delimiting research areas to determine its conceptual structure and scientific evolution (Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma, and Herrera, 2011b; Noyons, Moed, and van Rann, 1999b). In this article, the SMA is performed using the software Science Mapping Analysis Software Tool (“SciMAT”) (Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera, 2012b), designed and developed by the SECABA Laboratory at the University of Granada (Spain). SciMAT is based (Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera, 2011a) on a co-word analysis (Callon, Courtial, Turner and Bauin, 1983) and the h-index (Hirsch, 2005), which are applied in a longitudinal framework.

Data Sources

To obtain the publications of the journals and their citations, the bibliographic database WoS (property of Clarivate Analytics) is used. WoS is the world’s leading scholarly literature database in the sciences and social sciences: it is a reference database that provides with the most complete current and retrospective quality coverage in the sciences and social sciences, going back to 1900 (Harzing and van der Wal, 2008). A database with this property is appropriate for developing a rigorous SMA of the PE field focused on SMEs with a longitudinal perspective.

Sample

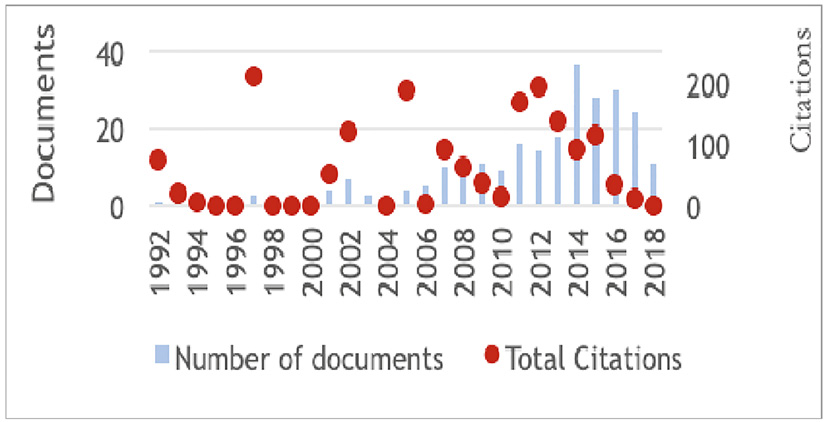

We focus on this analysis on articles dealing with all types of family businesses within the middle-market, meaning that they can imply family involvement in various ways, and can be private or public firms. The sample for this study consists of 252 documents (and their citations) published in the WoS core collection during the 1992–2018 period. It was extracted with an advanced search as follows: (“private equit*” OR “venture capita*”) AND (“small and medium-sized” OR “small and medium sized” OR “SME*” OR “middle market” OR “middle-market”) AND (“family owned” OR “family-owned” OR “FF*” OR “family business*” OR “family compan*” OR “family enterprise*”). The sample includes 186 journals. The distributions of the documents by years, together with their aggregated number of citations and the list of core economic journals are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively. Table 1 shows the year of the first article included in the sample and the aggregated number of citations corresponding to the articles included in the sample. For each document, the complete information provided by the WoS was retrieved, that is, authors, affiliations, title, abstract, keywords, references, citations, source, and so on.

|

Table 1 List of Top 20 Journals in the PE Field within FFs & SMEs between 1992 and 2018. |

||||

|

Journal |

First Year Included |

Nº of Documents Included |

Total Citations |

|

|

Small Business Economics |

1997 |

11 |

296 |

|

|

Journal of Business Venturing |

1992 |

5 |

251 |

|

|

Research Policy |

2003 |

5 |

187 |

|

|

Journal of Management |

2005 |

1 |

171 |

|

|

Organization Science |

2003 |

1 |

129 |

|

|

Academy of Management Perspectives |

2012 |

1 |

98 |

|

|

Journal of Economic Geography |

2002 |

2 |

72 |

|

|

Regional Studies |

2001 |

2 |

60 |

|

|

International Small Business Journal |

2006 |

5 |

55 |

|

|

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice |

2011 |

3 |

55 |

|

|

Corporate Governance - An International Review |

2005 |

4 |

52 |

|

|

Environment and Planning C-Government Policy |

2001 |

4 |

47 |

|

|

Journal of Cleaner Production |

2015 |

1 |

32 |

|

|

Applied Soft Computing |

2013 |

1 |

31 |

|

|

Venture Capital |

2015 |

6 |

21 |

|

|

Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal |

2013 |

1 |

17 |

|

|

Journal of Family Business Strategy |

2012 |

2 |

17 |

|

|

Journal of Small Business Management |

2013 |

4 |

14 |

|

|

Journal of Banking & Finance |

2014 |

1 |

7 |

|

|

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development |

2016 |

4 |

4 |

|

Figure 1 Distribution of documents included in the research by years and aggregated annual number of citations.

Procedure and Sample’s Processing

The documents were downloaded from WoS as plain text and added to SciMAT in ISIWoS format. They are the knowledge base for further SMA. Thus, it contains the bibliographic information stored by WoS per each research document. To improve the data quality, a deduplicating process was applied: the most repeated keywords and words representing the same concept were grouped as unit of analysis. A total of 872 word groups were created: 10 top word groups (“VC“, “SME”, “PE”, “Firm”, “FFs”, “Investments”, “Market”, “Finance”, “Industries” and “Models”) appearing in the majority of the documents were classified as “stop” groups (words with a very broad and general meaning) in the tool. Table 2 shows the top 20 keywords that were not classified as stop groups.

|

Table 2 Top 20 Keywords of the PE Field within FFs & SMEs between 1992 and 2018. |

|||

|

Keywords |

Number of documents |

Keywords |

Number of documents |

|

Performance |

35 |

Ownership Structure |

15 |

|

Innovation |

29 |

IPOs |

13 |

|

Corporate Governance |

27 |

Strategies |

12 |

|

R&D |

18 |

Information |

12 |

|

Growth |

18 |

Financing |

11 |

|

Agency Costs |

17 |

Firm Performance |

10 |

|

Ownership |

17 |

United Kingdom |

10 |

|

Management |

15 |

Start-Up |

9 |

|

Entrepreneurship |

15 |

Investor |

9 |

|

Leveraged Buyouts |

15 |

Management Buyouts |

9 |

Next, using the period manager of SciMAT, the periods of time of the longitudinal analysis were established. The whole time frame (1992–2018) was divided into three consecutive periods of time: 1992–2006, 2007–2012 and 2013–2018. In these periods of time, 33, 71 and 148 documents indexed in the WoS were found, respectively. The first period encompasses a greater number of years compared to the last two periods, but it was decided to make this distribution of years because: (i) in the early years of research there were few documents per year and, in order to detect correctly the themes of a discipline, it is necessary to define more or less homogeneous periods of time with respect to the number of documents (Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera and Herrera-Viedma, 2012a; Cobo et al., 2012b; López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma, Cobo, Martínez, Kou and Shi, 2012), and; (ii) the experience from previous studies of SMA (Cobo, Chiclana, Collop, de Oña, and Herrera-Viedma, In Press, 2014; Cobo et al., 2011a, 2011b, 2012a, 2012b) indicates that an excessive number of periods of time hampers the mapping and interpretation of thematic areas.

The next step is to configure the analysis. To perform it, the following configuration in SciMAT was established: author’s, source’s and added words as the unit of analysis (all with a threshold of 2 times as minimum frequency), co-occurrence analysis as the tool to build the networks (again with an edge value reduction of 2 times as minimum), equivalence index as the similarity measure to normalize the networks, and the simple centers algorithm as the clustering algorithm to detect the clusters or themes (with a network size range of between 3 and 12 times). The bibliometric measures chosen were the h-index and the sum of citations calculated for the documents that were mapped to each theme. Measures used for the longitudinal maps were: (i) the inclusion index to detect conceptual nexus between research themes of different periods of time through the evolution maps, and; (ii) the Jaccard’s Index (Peters and van Raan, 1993), which is a common similarity measure for the normalization process needed in bibliometrics, for the overlapping of the different detected clusters.

SMA’S results through SCIMAT

Detection of Research Themes: The PE Field within the Family Owned SMEs Market Segment

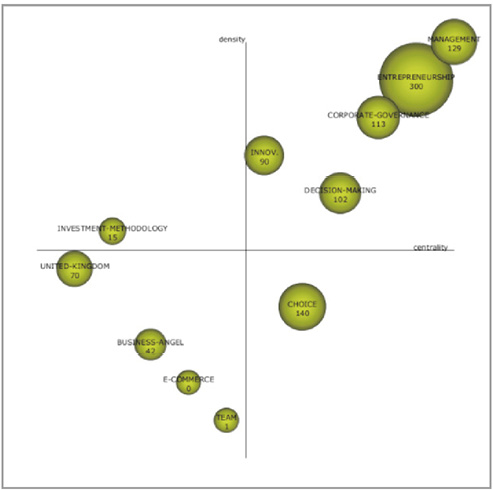

In order to analyze the most highlighted themes of the recent PE field focused on family owned SMEs for each period of time, a strategic diagram is provided. In each diagram, the sphere size is proportional to the number of citations associated with each research theme.

First period (1992-2006).

According to the strategic diagram presented in Figure 2, the PE research activity pivots on 5 themes during this period, with entrepreneurship, corporate governance, management, decision-making and innovation as key motor themes. The performance measures of the motor themes are given in Table 3. Entrepreneurship is the major motor theme in terms of performance measures: 300 citations and h-index 2.

Corporate governance is a system of structures and processes to direct and control the functions of an organization by setting up rules, procedures and formats for managing decisions within an organization (Palaniappan, 2017).

Management of corporate governance was identified together with other themes by Kaplan as one of the main sources for PEs’ value enhancement (Jensen, Kaplan, Ferenbach, Feldberg, Moon and Davis, 2006); it was also suggested as a corner stone in value creation by many studies (e.g., Jensen et al., 2006; Millson and Ward, 2005; Nisar, 2005). It is accepted that, on average, PE backing exerts a positive effect on investee firms. But little attention has been paid in the literature to the effect of PE involvement in FFs. PE financing is regularly promoted to meet the need for finance and, in addition, provide managerial expertise to help businesses overcome some of the challenges associated with growth. However, to retain ownership and control over the family business, owner managers often rely on internally generated funds (Berger and Udell, 1998; Poutziouris, 2001; Romano, Tanewski and Smyrnios, 2001). FFs that avoid external influences may be reluctant to take on any form of external finance, including PE (Poutziouris, 2001; Upton and Petty, 2000) but this could constrain their ability to grow.

In this period, Kellermanns and Eddleston (2006) investigated how generational involvement, willingness to change, and the ability to recognize technological opportunities impact corporate entrepreneurship in FFs. Their findings suggest that willingness to change and technological opportunity recognition are positively related to corporate entrepreneurship in FFs.

Several studies focus on the use of PE and VC by FFs between 1992 and 2006. These sources may be preferred in many cases because of the opportunity it offers to fund the FF transition (Upton and Petty, 2000).

The low use of external equity financing by FFs has been a focus of research in the past. This is usually due to a higher preference for internally generated funds rather than external sources, or debt financing rather than external equity financing. These preferences are linked to approaches done by several theories, like the stewardship theory (Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson, 1997). In FFs, financing has been linked to strategic decisions such as the timing of succession (Kimhi, 1997) and the sale of family business (Bhattacharya and Ravikumar, 2001).

Innovation emerges as a key motor theme yet in this period with studies about the important role in the process of creative destruction of SMEs (Acs, Morck, Shaver and Yeung, 1997), with focus on the international diffusion of SMEs innovations.

|

Table 3 Performance Measures for the Motor Themes (1992-2006). |

|||

|

Motor Themes |

Documents |

Citations |

h-Index |

|

Entrepreneurship |

2 |

300 |

2 |

|

Management |

1 |

129 |

1 |

|

Corporate Governance |

2 |

113 |

2 |

|

Decision-Making |

2 |

102 |

2 |

|

Innovation |

4 |

90 |

1 |

Figure 2 Strategic diagram for the 1992-2006 period.

Second period (2007-2012).

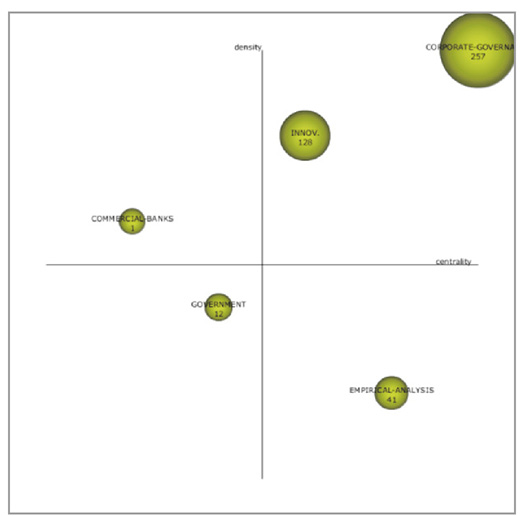

The research was focused on 5 themes (see Figure 3). In this case, 3 major themes can be identified (motor themes plus basic themes): corporate governance, innovation and empirical-analysis. Performance measures of the motor themes are shown in Table 4.

Corporate governance is closely linked to the use of investor funds to change corporate governance arrangements through buyouts of firms by PE firms in this period (Gilligan and Wright, 2010). PE professionals take into account family-specific criteria when selecting FFs to invest in, including human resources and opportunities to reduce agency costs. Furthermore, PE professionals prefer FFs that are already professionalized (Dawson, 2011).

Innovation appears as motor theme in this period. Bruque and Moyano (2007) studied the factors behind the intensity and speed of adoption of information technology in SMEs in which family or cooperative character play an important role. Their results indicate that there are a number of internal factors that influence the success of the adoption decision, on the one hand, and the implementation process, on the other hand. Puig and Perez (2009) studied innovation related to internationalization: the dominant role played by large FFs in the internationalization of the Spanish economy. In contrast with other countries, foreign capital and technology and collective action at regional, national and international levels play a far more important role in the internationalization of large FFs.

Several studies indicate that family involvement appears to result in lower use of external equity. In general, the distance between family businesses and external investors is large, mainly due to the “empathy gap” between owners and investors (Poutziouris, 2011) or because of the preferred retention of control rather than firm’s growth and development (Wu, Chua and Chrisman, 2007).

Studies of the use of PE and VC by FFs in this period suggest that these sources may be preferred in many cases because of the nonfinancial benefits that these types of investors can bring to the family such as managerial support, expertise, and contacts (Tappeiner, Howorth, Achleitner and Schraml, 2012; Martí, Menéndez-Requjo and Rottke, 2013).

In general, FF owners balance financial and non-financial resources of PE with the need to cede control rights: non-financial resources are valued more highly when resolving family issues (Tappeiner et al., 2012).

Figure 3 Strategic diagram for the 2008-2012 period.

|

Table 4 Performance Measures for the Motor Themes (2007-2012). |

|||

|

Motor Themes |

Documents |

Citations |

h-Index |

|

Corporate Governance |

11 |

257 |

8 |

|

Innovation |

9 |

128 |

5 |

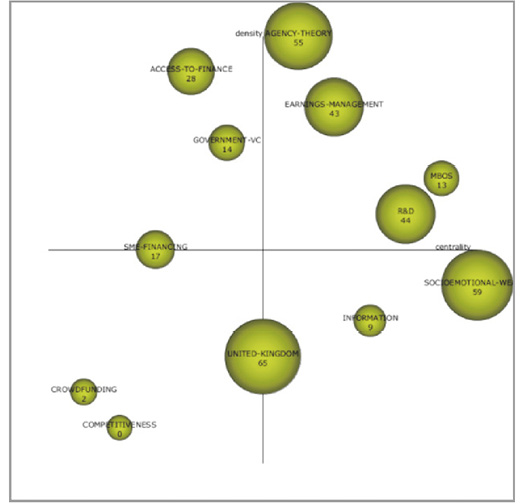

Third period (2013-2018).

The research conducted in this period is distributed in 12 PE themes (see Figure 4), with a clear atomization if compared to previous years. The performance measures of the main motor themes of the period are shown in Table 5.

|

Table 5 Performance Measures for the main Motor Themes (2013-2018). |

|||

|

Motor Themes |

Documents |

Citations |

h-Index |

|

Agency Theory |

12 |

55 |

2 |

|

Research & Development |

9 |

44 |

2 |

|

Earnings-Management |

6 |

43 |

4 |

|

Management Buyouts |

15 |

13 |

2 |

Management buyouts (“MBOs”) are a motor theme when they became phenomena of the 1980s: when no suitable family successor can be identified, FFs’ owners may select an MBO exit route. Some studies suggest that a PE buyout is a governance mechanism that may sustain an entrepreneurial transition by realigning family interests and goals (Di Toma and Montarani, 2017). Secondary buyouts (leveraged sales from one PE fund to another) have been the fastest growing segment of PE deals in last decade and therefore highly studied (Degeorge, Martin and Phalippou, 2016).

Despite more and more FFs open their capital for outside investors, existing studies mainly conclude that family companies are more reluctant that others to hand over control to outside investors. Exploratory evidence from a sample of Belgian FFs is supportive of the hypothesis that family members who identify strongly with their firms are less willing to cede control to outside investors and, if they do cede control, have a stronger preference for investors who may readily identify with FFs, like family offices or high net worth individuals (like business angels), rather than investors who may not fit well with a familial identity, such as PE or VC sponsors (Neckebrouck, Manigart an Meuleman, 2017).

Relevant literature about the PE’s positive effects on corporate governance and value creation has been developed in the last period (Acharya, Gottschalg, Hahn and Kehoe, 2013). The impact of PE on FFs’ performance was studied thought the analysis of the productivity growth in a sample of PE-backed family companies in 2016. The study found that FFs accessing PE showed lower productivity growth before the initial PE round, which was driven by an imbalance between inputs and output, especially in founder-controlled firms. This analysis also confirmed the positive impact of PE involvement on productivity growth in founder-controlled firms (Croce and Martí, 2016).

Figure 4 Strategic diagram for the 2013-2018 period.

Thematic Evolution of the PE Scientific Field focused on FFs & SMEs (1992-2018)

Structural analysis of the evolution of the PE scientific field focused on FFs and SMEs between 1992 and 2018.

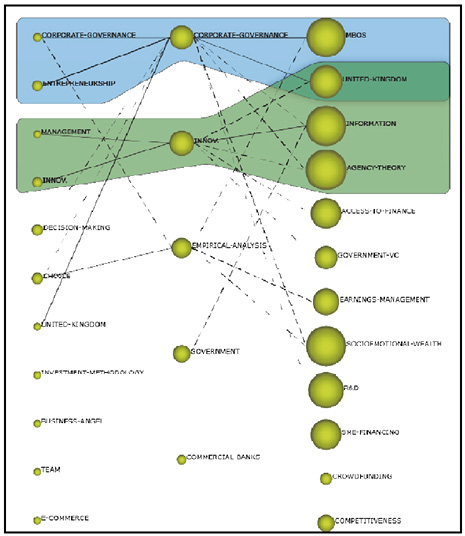

According to Figure 5, the research developed in the PE activity field presents a high cohesion level in the cases of the thematic areas “corporate governance-entrepreneurship” and “innovation-management”.

The two main thematic areas present a growth pattern, because they have been growing in the number of themes discussed since their origin. However, the PE scientific community is dynamic and relatively recent as the number of scientific documents starts growing in the second period, only twelve years ago. MBOs and the UK are new scientific areas that emerge between 2013 and 2018 and that lead to new research areas related to the study of the role of information asymmetries (Dehlen, Zellweger, Kammerlander and Halter, 2014) and the value of FFs for PE investors (Ahlers, Hack and Kelleermanns, 2014), in the case of MBOs.

And also related to the UK market (Mason and Pierrakis, 2013; Mason and Harrison, 2015), in the case of the UK. The two main thematic areas are constant between the first and second periods and then they go through an atomization process since year 2013. Therefore, the scientific communication has resulted in a specialization of the big historical thematic areas in niche research themes that become basic and transversal themes.

Figure 5 Thematic areas and evolution of the PE field focused on FFs & SMEs (1992-2018).

Performance analysis of the evolution of the PE scientific field focused on FFs and SMEs (1992-2018).

In Table 6, performance measures of the main thematic areas are provided. Corporate governance-entrepreneurship area stands out over the rest in terms of citations: 893 citations across the 1992-2018 period. Relevant research in corporate governance started in 2003, with a study of the primary rationalities governing the exchange relationships in family investment decisions during the early stages of new venture creation (Steier, 2003).

In the second period, corporate governance-entrepreneurship has high impact papers about management practices (Bloom, Genakos, Sadun and Van Reenen, 2012), where relevant findings about the relation between ownership and management were done. In the case of entrepreneurship, studies about the internationalization processes (George, Wiklund and Zahra, 2005) and owners’ succession (Wasserman, 2003) are the ones with the highest impact in the first period, with 171 and 129 citations, respectively,

|

Table 6 Performance Measures of the PE Field’s Main Thematic Areas (1992-2018). |

|||

|

Main Thematic Areas |

Documents |

Citations |

h-Index |

|

Corporate Governance - Entrepreneurship |

78 |

893 |

15 |

|

Innovation - Management |

97 |

715 |

14 |

Discussion and applications

This study aims at giving continuity and increase family owned SMEs’ consciousness of the positive effects and the increasing availability of the PE as an alternative to traditional growth funding, which has been widely demonstrated in past scientific research (Paglia and Harjoto, 2014). The coding phase of the analysis led to three interesting findings:

1.The quantity of PE scientific publications within the FFs and SMEs has an exponential increase across the last two decades thought the highest impact articles majority belong to the 1992-2012 period of the analysis. There has been an increase in the number of themes over time and, thus, an emergence of a more diverse and complex PE scientific discipline within field.

2.The thematic evolution analysis performed in this paper shows that corporate governance-entrepreneurship and innovation-management are the two big thematic areas of the recent PE research field. Therefore, it would be recommendable for family owned SMEs to promote corporate governance measures effectively.

3.The PE field presented a continuous, consistent, and cohesive growth, because there are no gaps in the main thematic areas. However, several research themes do not constitute a conceptual nexus with the classical themes and do not belong to any thematic area. Further scientific research on the field can be done for example to measure the PE’s board members contribution to the acquired company’s strategy: the Team Production Theory (Blair and Scout, 2001) shows that members must have knowledge of the firm to make decisions that create value (Kaufman and Englander, 2005).

The research done enables to access and assess key data of the discipline to make decisions in different frameworks:

Family owned SMEs: they might use this analysis to understand and become familiar with PE funds historical activity and the value they can add to their growth plans. In addition, the use of PE to execute internationalization plans can have additional benefits different to the mere financing and performance improvement: recent studies have demonstrated that a high degree of geographic international diversification enables multinational companies to improve its social performance (Aguilera-Caracuel, Guerrero-Villegas and García-Sánchez, 2017).

Private Equity funds focused on the middle-market: in the past decade there has been an increasing role of the PE industry in the financing of enterprises what can boost economic growth. PE funds can identify new market niches within the family owned SMEs segment for their acquisitions.

Academic centers: scientists could identify new and relevant challenges in their field for future research, as well as the emerging themes.

This study opens up new possibilities for discovering important research areas in the PE field within the family owned middle-market. It provides empirical analysis that can benefit from a further development of this subject as a discipline.

Limitations and further research

This research has several limitations, which in turn, reveal the path for future lines of research. The first limitation is related to the scope of our results and their implications. Since the study was performed on a recent sample, the results cannot be transferred to the entire scientific PE field focused on the middle-market. Future research could develop the study defined here: scientific research prior to year 1992 could be analyzed and also a new research with other keywords might result in new findings.

To choose the information sources for our analysis, we have used the WoS database: an alternative selection of databases would likely produce different results. Other limitations relate to our methodology since we use only those documents published in the most important journals indexed in WoS in the PE category. Therefore, we are missing the PE research published primarily outside of those journals that are not indexed in WoS. Other methodological bias was introduced in the co-words analysis: further research could be done by using other bibliometric techniques that complement this study and provide a systematic description of the structure of the field.

References

Acharya, V. V., Gottschalg, O. F., Hahn, M. and Kehoe, C. (2013). “Corporate Governance and Value Creation: Evidence from Private Equity”. Review of financial studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 368-402. doi: 10.1093/rfs/hhs117.

Acs, Z.J., Morck, R., Shaver, J.M., Yeung, B. (1997). “The Internationalization of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises: A Policy Perspective”. Small Business Economics, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 7-20.

Aguilera-Caracuel, J., Guerrero-Villegas, J. and García-Sánchez, E. (2017). “Reputation of multinational companies: Corporate social responsibility and internationalization”. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 329-346. doi: 10.1108/EJMBE-10-2017-019.

Ahlers, O. (2014). FFs and Private Equity: A Collection of Essays on Value Creation, Negotiation, and Soft Factors. Vallendar, Germany: Springer Gabler.

Ahlers, O., Hack, A. and Kellermanns, F.W. (2014). ““Stepping into the buyers’ shoes”: Looking at the value of FFs through the eyes of private equity investors”. Journal of Family Business Strategy, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 384-396. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.04.002.

Anderson, R. C. and Reeb, D. M. (2003). “Founding-Family Ownership and Firm Performance: Evidence from the S&P 500”. Journal of Finance, Vol. 58, No. 3, pp. 1301–1328.

Astrachan, J. H. and Shanker, M. C. (2003). “Family Businesses’ Contribution to the U.S. Economy: A Closer Look”, Family Business Review, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 211–219. doi: 10.1177/08944865030160030601.

Benavides-Velasco, C.A., Quintana-García, C. and Guzmán-Parra, V.F. (2013). “Trends in family business research”. Small Business Economics, Vol. 40, pp- 41-57.

Bengtsson, P., Nagel, R. and Nguyen, A. (2008). Value Creation in Buyouts: value-enhancement practices of private equity firms with a hands-on approach. Jönköping International Business School.

Berger, A. N. and Udell, G. F. (1998). “The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle”. Journal of banking & finance, Vol. 22, No. 6-8, pp. 613-673. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00038-7.

Bhattacharya, U. and Ravikumar, B. (2001). “Capital markets and the evolution of family businesses”. Journal of Business, Vol. 74, pp. 187-219.

Birley, S. and Westhead, P. (1990). “Private business sales environments in the United Kingdom”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 349-373.

Blair, M. and Stout, L.A. (2001). “Director accountability and the mediating role of the corporate board”. Washington University Law Review, Vol. 79, pp. 403-449.

Bonini, S. (2015). “Secondary Buyouts: Operating Performance and Investment Determinants”. Financial Management, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 431-470. doi: 10.1111/fima.12086.

Bruque, S. and Moyano, J. (2007). “Organisational determinants of information technology adoption and implementation in SMEs: The case of family and cooperative firms”. Technovation, Vol. 27, No. 5, pp. 241-253.

Bruton, G. D., Filatochev, I., Chahine, S. and Wright, M. (2010). “Governance, Ownership Structure, and Performance of IPO Firms: The Impact of Different Types of Private Equity Investors and Institutional Environments”. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 31, No. 5, pp. 491-509. doi: 10.1002/smj.822.

Callon, M., Courtial, J. P., Turner, W. A. and Bauin, S. (1983). “From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis”. Social Science Information, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 191–235.

Chrisman, J., Chua, J., Pearson, A. W. and Barnett, T. (2012). “Family involvement, family influence and family-centered non-economic goals in small firms”. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 267–293.

Chua, J.H., Chrisman, J.J. and Sharma, P. (2003). “Succession and non-succession concerns of family firms and agency relationship with non-family managers”. Family Business Review, Vol. 16, pp. 89-107.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., Steier, L. P. and Rau, S. B. (2012). “Sources of Heterogeneity in FFs: An Introduction”. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Vol. 36, No. 6, pp. 1103–1113.

Cobo, M., Chiclana, F., Collop, A., de Oña, J. and Herrera-Viedma, E. (In Press, 2014). “A bibliometric analysis of the intelligent transportation systems research based on science mapping”. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. doi:10.1109/TITS.2013.2284756.

Cobo, M., López-Herrera, A., Herrera-Viedma, E. and Herrera, F. (2011a). “An approach for detection, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field”. Journal of Informetrics, Vol. 5, pp. 146–166. doi:10.106/j.joi2010.10.002.

Cobo, M., López-Herrera, A., Herrera-Viedma, E. and Herrera, F. (2011b). “Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis and cooperative study among tools”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 62, pp. 1382–1402. doi:10.1002/asi.21525.

Cobo, M., López-Herrera, A., Herrera F. and Herrera-Viedma, E. (2012a). “A note on the ITS topic evolution in the period 2000-2009 at T-ITS”. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Vol. 13, pp. 413-420. doi: 10.1109/TITS.2011.2167968.

Cobo, M., López-Herrera, A., Herrera-Viedma, E. and Herrera, F. (2012b). “SciMAT: A new science mapping analysis software tool.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 63, No 8, pp. 1609–1630. doi:10.1002/asi.22688.

Croce, A. and Marti J. (2016). “Productivity Growth in Private-Equity-Backed FFs”. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 657-683. doi: 10.1111/etap.12138.

Cumming, D. (2007). “Government Policy Towards Entrepreneurial Finance: Innovation Investment Funds”. ournal Of Business Venturing, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 193-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.12.002.

Cumming, D., Cole, R. and Li, D. (2016). “Do banks or VCs spur small firm growth?”. Journal of international financial markets, institutions & money, Vol. 41, pp. 60-72. doi: 10.1016/j.intfin.2015.12.005.

Cumming, D., Grilli, L. and Murtinu, S. (2017). “Governmental and independent venture capital investments in Europe: A firm-level performance analysis”. Journal of corporate finance, Vol. 42, pp. 439-459. doi: 10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.10.016.

Cumming, D., Siegel, D. S. and Wright, M. (2007). “Private equity, leveraged buyouts and governance”. Journal of corporate finance, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 439-460. doi: 10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2007.04.008.

Dvid, J.H., Schoorman, F.D. and Donaldson, L. (1997). “Toward a stewardship theory of management”. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22, pp. 20.47.

Dawson, A. (2011). “Private equity investment decisions in FFs: The role of human resources and agency costs”. Journal of business venturing, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 189-199. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.05.004.

Degeorge, F., Martin, J., Phalippou, L. (2016). “On secondary buyouts”. Journal of financial economics, Vol. 120, No. 1, pp. 124-145. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.08.007.

Dehlen, T., Zellwegere, T., Kammerelander, N. and Halter, F. (2014). “The Role Of Information Asymmetry In The Choice Of Entrepreneurial Exit Routes”. Journal Of Business Venturing, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 193-209. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.10.001.

Di Toma, P. and Montanari, S. (2017). “Corporate governance effectiveness along the entrepreneurial process of a FF: the role of private equity”. Journal of Management & Governance, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 1023-1052. doi: 10.1007/s10997-016-9373-1.

Dwyer, B. and Kotey, B. (2015). “Financing SME Growth: The Role of the National Stock Exchange of Australia and Business Advisors”. Australian accounting review, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 114-123. doi: 10.1111/auar.12074.

European Central Bank (November of 2017). External sources of financing and needs of SMEs in the euro area. Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area – April to September 2017. pp. 12-16. Retrieved from http://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/ecb_surveys/safe/html/index.en.html.

European Commission. Entrepreneurship and Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). European Commission. Retrieved from http://www.ec.europa.eu/growth/smes_en.

Fazekas, B. and Becksky-Nagy, P. (2015). “Private equity market in recovery”. Emerging markets queries in finance and business 2014, Vol. 32, pp. 225-231. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01386-6.

Ferrer, M. A., Bertoni, F. and Martí Pellón, J. (2010). Effects of venture capital and private equity on investment-cash flow sensitivity of Spanish firms. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Gilligan, J. and Wright, M. (2010). Private equity demystified. 2nd edition. London: ICAEW.

Grilli, L. and Murtinu, S. (2015). “New technology-based firms in Europe: market penetration, public venture capital, and timing of investment”. Industrial and corporate change, Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 1109-1148. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtu025.

Haro de Rosario, A., Caba Pérez, M. C. and Cazorla Papis, L. (2013). Eficiencia en el sector del capital riesgo y private equity: análisis del caso español (Doctoral thesis). Universidad de Almería. Almería.

Harzing, A. and van der Wal, R. (2008). “Google scholar as a new source for citation analysis”. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, Vol. 8, pp. 61–73. doi: 10.3354/esep0007.

Herrera-Viedma, E., Martínez, M. A., Cobo, M. and Herrera, M. (2015). “Analyzing the Scientific Evolution of Social Work Using Science Mapping”. Research on Social Work Practice 2015, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 257-277.

Higashide, H. and Birley, S. (2002). “The consequences of conflict between the venture capitalist and the entrepreneurial team in the United Kingdom from the perspective of the venture capitalist”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 59-81.

Hirsch, J. (2005). “An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 102, pp. 16569–16572.

Howorth, C., Westhead, P. and Wright, M. (2004). “Buyouts, information asymmetry and the family management dyad”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 509-534.

Hung, Y. D. and Tsai, M. H. (2017). “Value Creation and Value Transfer of Leveraged Buyouts: A Review of Recent Developments and Challenges for Emerging Markets”. Emerging markets finance and trade, Vol. 53, No. 4, pp. 877-917. doi: 10.1080/1540496X.2016.1193000.

IFERA (2003). “Family Businesses Dominate”. Family Business Review, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 235–240.

Jensen, M., Kaplan, S., Ferenbach, C., Feldberg, M., Moon, I. and Davis, C. (2006). “Morgan Stanley Roundtable on Private Equity and Its import for Public Companies”. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 8-37.

Johan, S. and Zhang, M. J. (2016). “Private equity exits in emerging markets”. Emerging markets review, Vol. 29, pp. 133-153. doi: 10.1016/j.ememar.2016.08.016.

Kaplan, S. N., and Schoar, A. (2005). “Private equity performance: Returns, persistence, and capital flows”. Journal of finance, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 1791-1823. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00780.x.

Kaplan, S. N., Martel, F. and Stroberg, P. (2007). “How Do Legal Differences And Experience Affect Financial Contracts?”. Journal of financial intermediation, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 273-311. doi: 10.1016/j.jfi.2007.03.005.

Kaufman, A. and Englander, E. (2005). “A team production model of corporate governance”. Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 19, pp. 9-22.

Kellermanns, FW. and Eddleston, KA. (2006). “Corporate entrepreneurship in family firms: A family perspective”. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 30, No. 6, pp. 809-830.

Kimhi, A. (1997). “Intergenerational succession in small family businesses: Borrowing constraints and optimal timing of succession”. Small Business Economics, Vol. 9, pp. 309-318.

Klein, S. B. (2000). “Family Businesses in Germany: Significance and Structure”. Family Business Review, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 157–181.

Koropp, C., Kellermanns, F.W., Grichnik, D. and Stanley, L. (2014). “Financial decision in FFs: An adaptation of the theory of planned behavior”. Family Business Review, Vol. 27, pp. 307-327.

KPMG and European Family Business (Sixth edition, 2017). European Family Business Barometer. Retrieved from http://www.europeanfamilybusinesses.eu.

Lahmann, A. D. F., Stranz, W. and Velamuri, V. K. (2017). “Value creation in SME private equity buy-outs”. Qualitative research in financial markets, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 2-33. doi: 10.1108/QRFM-01-2016-0004.

López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., Cobo, M. J., Martínez, M. A., Kou, G. and Shi, Y. (2012). “A conceptual snapshot of the first decade (2002-2011) of the international journal of information technology & decision making”. International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making, Vol. 11, pp. 247–270. doi:10.11142/ S021962220124000020.

Martí J., Menéndez-Requejo S. and Rottke O.M. (2013). “The impact of venture capital on family businesses: Evidence from Spain”. Journal of World Business, Vol. 48, pp. 420-430.

Mason, C.M. and Harrison, R.T. (2015). “Business Angel Investment Activity In The Financial Crisis: Uk Evidence And Policy Implications”. Environment And Planning C-government And Policy, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 43-60. doi: 10.1068/c12324b.

Mason, C, and Pierrakis, Y. (2013). “Venture Capital, The Regions And Public Policy: The United Kingdom Since The Post-2000 Technology Crash”. Regional Studies, Vol. 47, No. 7, pp. 1156-1171. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2011.588203.

Metrick, A. and Yasuda, A. (2005). “Venture Capital and Other Private Equity: a Survey”. European Financial Management, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 619-654.

Michiels, A. and Molly, V. (2017). “Financing decision in family businesses: a review and suggestions for developing the field”. Family Business Review, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 369-399. Doi: 10.1177/0894486517736958.

Millson, R. and Ward, M. (2005). “Corporate Governance Criteria as Applied in Private Equity Investments”. South African Journal of Business Management, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 78-83.

Mohnen, P., Palm, F. C., Van Der Loeff, S. S. and Tiwari, A. (2008). “Financial Constraints And Other Obstacles: Are They A Threat To Innovation Activity?”. Economist-Netherlands, Vol. 156, No. 2, pp. 201-214. doi: 10.1007/s10645-008-9089-y.

Morck, R. and Yeung, B. (2003). “Agency Problems in Large Family Business Groups”. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 367–382.

Neckebrouck, J., Manigart, S. and Meuleman, M. (2017). “Attitudes of FFs toward outside investors: the importance of organizational identification”. Venture Capital, Vol. 19, No. 1-2, pp. 29-50. doi: 10.1080/13691066.2016.1255414.

Nisar, M. N. (2005). “Investor Influence on portfolio company growth and development strategy”. Journal of Private Equity, Vol. 9, No. 1, 22-35.

Noyons, E., Moed, H. and Van Rann, A. (1999b). “Integrating research performance analysis and science mapping”. Scientometrics, Vol. 46, pp. 591–604.

Paglia, J.K. and Harjoto, M.A. (2014). “The effects of private equity and venture capital on sales and employment growth in small and medium-sized businesses”. Journal of banking & finance, Vol. 47, pp. 177–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.06.023.

Palaniappan, G. (2017). “Determinants of corporate financial performance relating to board characteristics of corporate governance in Indian manufacturing industry: An empirical study”. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 67-85. doi: 10.1108/EJMBE-07-2017-005.

Peters, H. P. and Van Raan, A. F. (1993). “Co-word-based science maps of chemical engineering. Part I: Representations by direct multidimensional scaling”. Research Policy, Vol. 22, pp. 23–45.

Poutziouris, P.Z. (2001). “The views of family companies on venture capital: Empirical evidence from the UK small to medium-size enterprising economy”. Family Business Review, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 277-291.

Poutziouris, P.Z. (2011). “The financial structure and performance of owner-managed FFs: Evidence from the UK economy”. Universia Business Review, Vol. 32, pp. 70.

Preqin (2010). Q3 2010 private equity data: Private equity has strongest quarter since financial crisis. Preqin. http:// privateequityblogger.com/2010/10/q3-2010-private-equitydata.html.

PWC (2012). Family Firm: A resilient model for the 21st century. From PwC Family Business Survey. Retrieved from: http://www.pwc.com/en_GX/gx/pwc-family-business-survey/assets/pwc-family-business-survey-2012.pdf.

PWC (2018). The values effect. From PwC Family Business Survey 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/family-business-services/assets/pwc-global-family-business-survey-2018.pdf.

Ramón Llorens, M. C. and Hernández Cánovas, G. (2011). Análisis de la actuación del gestor del capital riesgo en la toma de decisiones de participación financiera. Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena.

Renneboog, L., Simons, T. and Wright, M. (2007). “Why Do Public Firms Go Private in the UK? The Impact of Private Equity Investors, Incentive Realignment and Undervaluation”. Journal of corporate finance, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 591-628. doi: 10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2007.04.005.

Robertson, J. (2017). “Emergent new finance: hedge funds and private equity funds in East Asia”. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 626-646. doi: 10.1080/13547860.2017.1349861.

Romano, C.A., Tanewski, G.A. and Smyrnios, K.X. (2003). “Capital structure decision making: a model for family business”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 16, pp. 285-310.

Ruiz Martín, M. (2006). Actividad de las entidades de capital riesgo en España. CNMV.

Sánchez Hernández, M. M., Reverte Maya, C. and Rojo Ramírez, A. A. (2013). La valoración de inversiones por parte de las sociedades de capital riesgo: un estudio empírico aplicado al ámbito europeo. Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena.

Seco Benedicto, M. T., Martí Pellón, J. (2007). La actividad de capital riesgo en el área de Asia-Pacífico: entorno y determinantes. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Shanker, M.C. and Astrachan, J.H. (1996). “Myths and realities: family businesses’ contributions to the US economy”. Family Business Review, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 107-123.

Siegel, D., Wright, M. and Filatotchev, I. (2011). “Private Equity, LBOs, and Corporate Governance: International Evidence”. Corporate Governance: An International Review, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 185–194.

Sirmon, D.G. and Hitt, M.A. (2003). “Managing resources: linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms”. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 339-358.

Small, H. and Amer, J. (1973): “Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents”. Soc. Inf. Sci., Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 265–269.

Steier, L. (2003). “Variants Of Agency Contracts In Family-financed Ventures As A Continuum Of Familial Altruistic And Market Rationalities”. Journal Of Business Venturing, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 597-618. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00012-0.

Strömberg, P. (2008). “The new demography of private equity”. In Lerner, Josh. & Gurung, A. (eds). The Global Impact of Private Equity Report 2008, Globalization of Alternative Investments, Working Papers Vol. 1, World Economic Forum, pp. 3-26.

Tappeiner, F., Howorth, C., Achleitner, A.K. and Schraml, S. (2012). “Demand for private equity minority investments: A study of large FFs”. Journal of family business strategy, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 38-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2012.01.001.

Tresierra Tanaka, A. E., Balboa Ramón, M. and Martí Pellón, J. (2011). Capital structure analysis in Spanish venture capital-backed firms at the expansion stage. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Tsang, E. W. K. (2002). “Learning from overseas venturing experience: The case of Chinese family businesses”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 21–40.

Upton, N. and Petty, W. (2000). “Venture capital investment and US family business”. Venture Capital, Vol. 2, pp. 27-39.

Van Raan, A. F. J. (2005). “Measuring science”. Handbook of Quantitative Science and Technology Research. Dordrecht, The Netherlands. pp. 19–50.

Voordeckers, W., Le Breton-Miller, I. and Miller, D. (2014). “In search of the best of both worlds: Crafting a finance paper for the Family Business Review”. Family Business Review, vol. 27, pp. 281-286.

Wasserman, N. (2003). “Founder-Ceo Succession And The Paradox Of Entrepreneurial Success”. Organization Science, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 149-172. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.2.149.14995.

Winton, A. and Yerramilli, V. (2008). “Entrepreneurial finance: Banks versus venture capital”. Journal of financial economics, Vol. 88, No. 1, pp. 51-79. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.05.004.

Wright, M., Amess, K., Weir, C. and Girma, S. (2009a). “Private equity and corporate governance: Retrospect and prospect”. Corporate Governance: An International Review, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 253–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00744.x.

Wright, M., Jackson, A. and Frobisher, S. (2010). “Private equity in the UK: Building a new future”. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol. 22, pp. 86–95.

Wu, Z., Chua, J.H. and Chrisman, J.J. (2007). “Effects of family ownership and management on small business equity financing”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 22, pp. 875-985.