|

|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Barriers or motivation? Career progress in the family firm: daughters’ perspective

Anna Akhmedovaa, Rita Cavallottib, Frederic Marimonc,*

a IESE Business School, University of the Navarra, Spain

b Department of Humanities, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain

c Department of Economy and Business Organization, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain

Received 06 september 2018; accepted 12 December 2018

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10; J28; D63

KEYWORDS

Family business; gender; motivation; barriers; position; ethics

Abstract Women are under-represented in high-level management and administrative positions in family businesses. To date, the research on career motivation remains in the shadows of research on gender barriers. By acknowledging the relation between the two, it is proposed to look holistically at the problem and to empirically examine the relation between motivation, barriers, and position of daughters in family business in the family firm. By conducting SEM analysis, it was found that motivation to act ethically is positively associated with high positions and that barriers “specific to family business” are negatively related to high positions. This article validates two scales and makes methodological contributions to the stream of research on daughters in family business that to date relies mainly on qualitative studies.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10; J28; D63

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar; género; motivación; barreras; posición; ética

¿Barreras o motivación? Progreso de la carrera en la empresa familiar: la perspectiva de las hijas

Resumen Las mujeres están subrepresentadas en los puestos directivos y de gestión de alto nivel en las empresas familiares.

Hasta la fecha, la investigación sobre la motivación para la carrera permanece en las sombras de la investigación sobre barreras de género.

Al reconocer la relación entre los dos, se propone mirar holisticamente al problema y examinar empíricamente la relación entre la motivación, las barreras,

y la posición de las hijas en la empresa familiar.

Al realizar el análisis SEM, se encontró que la motivación para actuar éticamente está asociada positivamente con posiciones altas y que las barreras “específicas para las empresas familiares” están relacionadas negativamente con las altas posiciones. Este artículo

valida dos escalas y realiza contribuciones metodológicas a la corriente de investigación sobre hijas en empresas familiares que hasta la fecha se basan principalmente en estudios cualitativos.

Introduction

Women play important implicit and explicit roles in family businesses. However, most of the academic literature and business reports suggest that women are under-represented in high-level management and administrative positions in family businesses (Englisch et al., 2015; Casillas Bueno et al., 2015; Steinbrecher et al., 2016). The under-representation was traditionally explained by the fact that male successors are preferred over female successors due to primogeniture (Dumas 1989; Hollander and Bukowitz, 1990); invisibility (Hollander and Bukowitz, 1990); and role incongruity between a leader role, family role and gender role (Hollander and Bukowitz, 1990; Salganicoff, 1990).

However, recent research indicates that incidents of discriminative practices cannot statistically explain the huge gap between female and male presence in high-level positions in family firms (e.g. Pascual Garcia, 2013; Steinbrecher et al., 2016). With the increased inclusion of women in management roles, daughters in family business might have career aspirations that are not related to the family firm. As Schröder, Schmitt-Rodermund, and Arnaud (2011) suggest, having entrepreneurial parents may foster daughters’ interest in doing business in general, but the specific family business may not be attractive to them. Additionally, some authors suggest that daughters in family businesses are “excluding themselves” from being potential successors by not showing interest (Curimbaba, 2002; Otten-Papas, 2013). Thus, family businesses might be losing important human capital in the case of daughters in family business and their descendants not only due to the presence of gender barriers but also due to the lack of motivation. Therefore, family business incumbents might increase the available stock of human capital by fostering motivation of daughters. This study attempts to revise and update existing knowledge about antecedents of the gender gap in high management positions from an academic point of view.

To address this complexity, it is suggested to look holistically at the problem and to explore both: the role of barriers and the role of motivation. Thus, the goal of this paper is to develop a tool to measure motivation and barriers that daughters in family business face and to empirically examine the relation of different types of motivation and barriers with daughters’ positions in family firms. Results of this study might induce further quantitative investigation of the interrelation between motivation and barriers.

Motivation and barriers of daughters in family business

To date, research on the motivation of daughters in family business remains unsystematic and underexplored. A meta-study by Akhmedova, Cavallotti, and Marimon (2015) that examined articles on the motivation of daughters in family business suggested that career motivation seemed to be guided by a combination of (1) extrinsic motivation such as better remuneration, flexibility of hours, job security, and comfortable lifestyle; (2) intrinsic motivation like autonomy / independence in choosing responsibilities as well as interesting, challenging, and satisfying work; and (3) pro social or transcendent/non-material motivation, for example helping family and giving back to the family. Of special interest was the finding that females reported somewhat more transcendent / non-material motivation (motivation to act ethically towards different stakeholders of the firm) than men.

Following this stream, the article also draws on the anthropological theory (Perez López, 1991, 1993, 1997). This theory is used because it is based on three types of motivation that fit with the description of motivation shown by daughters in family business. The anthropological theory is based on the idea of rational interaction and learning. Positive learning happens when agents consistently react as expected: the climate of trust among organization members improves (Perez Lopez, 1991). Negative learning is also possible, when one feels betrayed by another. As a result, responsible behaviour is always required, since any business decision would affect many people. Thus, leaders who act not only out of extrinsic and intrinsic motives, but also out of ethical considerations (transcendent / non-material motivation), obtain, in the long run, greater recognition by their colleagues and subordinates. Leaders who demonstrate non-selfish motivation will unite subordinates to develop a genuine interest in their business, resulting in more effective and efficient solutions. It can be hypothesized that daughters in family business who act not only out of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation but also out of ethical considerations (transcendent motivation) tend to be promoted to higher leadership positions. This proposition will be discussed and tested further.

Daughter barriers to leadership

Barriers to leadership in family businesses have been discussed during the last several decades as the main factor impeding progress of daughters in family business. Cognitive theories of motivation relate perception of success to motivation (i.e. Bandura, 1997). Therefore, when considering motivation, it is important to take the perception of barriers into account. The review of literature on the next generation in family firms yielded the following types of barriers: (1) barriers specific to family businesses and (2) general gender barriers.

There are several facets under the rubric of gender barriers specific to family businesses: primogeniture, invisibility, role incongruity, and lack of mentoring (Gupta and Levenburg, 2013). First, primogeniture, or “the transfer of leadership from father to the first-born son” (Cole, 1997), was widely discussed in the family business literature, and many authors confirmed that gender can be the main factor when determining a successor, with males being preferred (Keating and Little, 1997) and women being “rarely considered serious candidates” (Martínez Jimenez, 2009, p. 56) and “overlooked as potential successors unless a family crisis creates the opportunity for them” (Dumas, 1989). Still, some owners even “prefer to sell the business rather than putting the daughter in a leadership role” (Dumas, 1992). Conventionally, daughters from families with more brothers are less likely to become successors (Curimbaba, 2002; Haberman and Danes, 2007; Ahrens, Landmann and Woywode, 2015).

Related to primogeniture, daughter invisibility is the next most important issue discussed in family business literature. Being invisible in the family business means being “viewed by others, whether within or outside the business, not similarly as the male members” (Hollander and Bukowitz, 1990; Cole, 1997). Cole (1997) provides a good illustration for this concept, given by one of the daughters in family business in her study: “well, even when customers come here, I think they prefer to deal with my husband. Sometimes I feel like I get the brush off.”

Role incongruity or role conflict refers to the two incompatible roles (family and business) contained in family business relationships (Salganicoff, 1990; Cole, 1997). The father–daughter relationship can be especially vulnerable to the role conflict (Glover, 2014; Deng, 2015). A father might fail to define the daughter’s role in the company and expect her to behave as a businesswoman, while at the same time seeing her as “daddy’s little girl” (Dumas, 1989), making it difficult for her to establish her own sense of identity (Deng, 2015; Hytti, Alsos, Heinonen, Ljunggren, 2017).

This role conflict is exacerbated by the “traditional” conflict between leader and gender roles, consisting in an unfavourable double discrepancy (Eagly and Karau, 2002; Koening et al. 2011; Ely, Ibarra, and Kolb 2011). On the one hand, women are less favourably evaluated because leadership ability is more stereotypical of men than of women. On the other hand, they are less favourably evaluated because agentic behaviour is less desirable in women than in men.

Finally, the lack of mentoring and family support links to the problem of unequal treatment of daughters and sons. Rosenblatt (1985) argued that daughters in family business were not encouraged and supported in the same way as sons. And while identifying key differences between daughters and sons, Iannarelli (1992) points out that “daughters spend less time in business, develop fewer skills and are less frequently encouraged professionally than their male siblings”.

On the other hand, daughters in family business are not exempt from traditional or general gender barriers that are mentioned in the literature on gender leadership, brought on by either (1) macro factors: “old boys network”, lack of role models, work–family balance, hierarchy dominated by males or (2) micro factors: low self-esteem and the perception of a lack of leadership qualities.

The interplay of macro (societal and cultural attitudes) and micro (individual and family-related) factors is not always straightforward (Wang, 2010). Taking the example of the work–life balance, one of the widely discussed topics, this issue will be explained. While some authors believe that family conflict for daughters in family business is less stiff / serious (e.g. Salganicoff, 1990), others come to the opposite conclusion (e.g. Vera and Dean, 2005). Family conflict, when experienced, results in that daughters “advance as fast as men, but not always want to advance” (Cole, 1997). Cole (1997) suggests that the glass ceiling should be better called “mirrored ceiling” – giving women opportunity to reflect on why they want to reach upper management positions, and if needed, return to lesser positions. On the other hand, some authors argue that daughters are often “blind to their opportunities in family business” (Overbeke et al., 2013) due to activation of “automatic processes prescribed by gender roles”, reflecting role congruity theory (Eagly and Karau, 2002) and gender schemas (Bem, 1993). Thus, the division between micro and macro factors is not always clear from the literature.

Self-confidence is a subjective estimation of one’s ability to perform a task – estimation based on previous successes or failures as well as on skills, knowledge, and access to resources (financial, social, etc.). Women’s confidence, in both the belief in their own abilities as well as the capability of communicating confidence, tends to be lower than that of men. As an example, research amongst MBA women shows that while women consider themselves equally capable as their co-workers most men consider themselves more capable than their co-workers (Eagly, 2003).

Women who experience barriers – whether family-related (primogeniture, role incongruity, lack of support), social (“old boys network”, male-dominated organizational hierarchy (McDonald, 2011), or internal (low self-esteem, low confidence) – will face more difficulties in career progression. It is probable that high barriers will lower their career aspirations and demotivate them from taking on challenging tasks.

Hypothesis 1: Perceived barriers have a negative relationship with position.

Extrinsic motivation

In terms of the anthropological theory (Perez López, 1991), extrinsic motivation might be defined as motivation for an activity that is done for an isolated result of an acting person (not inherent satisfaction). This result may be economic and come from the organization directly (a salary or bonus) but may also be non-economic and come from other sources (prestige and social status, which is a recognition from family, friends, or other people). The review of literature on the next generation in family firms yielded the following areas of extrinsic motivation: (1) work–life balance, (2) monetary issues, and (3) easy career.

The work–life balance is the cornerstone of women’s work motivation. According to Cole (1997) and Vera and Dean (2005), combining work with a caretaking role is one of the biggest preoccupations of working females. Salganicoff (1990) found that women in a family business perceive it as a more flexible environment for raising children. Other studies also cite flexible hours, quality of life, being their own boss, and a reasonable schedule as benefits that attract women to family businesses (Dumas et al., 1995; Vera and Dean, 2005).

The role of monetary compensation is important and cited throughout the literature. Although working for a family company does not automatically provide a better salary or warrant other economic benefits, some family business successors assume that a family business might be a good source of financial security and stability, even for an extended family, and provide wonderful quality of life (Dumas et al., 1995, Dumas, 1998). Further, a family business can offer the opportunity to enter the company without formal barriers and to be promoted faster for some daughters in family business. However, “grabbing this opportunity, especially when experiencing difficulties elsewhere” (Dumas, 1998, p. 226) might be a form of nepotism for those who are seeking an easy career.

Daughters’ commitment to family businesses based solely or predominantly on extrinsic motivation is not infrequent, but it might be damaging to the business or at least not desirable for business development. For those of the previous generation who desire to see their company growing and developing after succession, it is natural to search for a successor who has relevant attributes such as skills, motivation and abilities to further develop the company (Sharma, 2004). Thus, daughters who see family businesses only as a good source of financial security and stability, that provide wonderful quality of life and easy career (Dumas et al., 1995, Dumas, 1998) might be facing higher leadership barriers imposed by the previous generation. Curimbaba (2002) states that a certain type of women – invisible heiresses , who view family businesses as a source of accumulated wealth - believe that the income balances out / compensates being invisible in the company. Thus, previous studies point to a seeming trade-off involving extrinsic motivation, barriers and position.

Hypothesis 2: Daughters’ motivation based on extrinsic outcomes is positively associated with perceived leadership barriers.

Hypothesis 3: Daughters’ motivation based on extrinsic outcomes is negatively associated with high positions in management.

Intrinsic motivation

An intrinsically motivated activity is done for the inherent satisfaction of the person acting. It deals with the satisfaction that the person obtains from the work itself. The review of literature on the next generation in family firms yielded the following areas of intrinsic motivation: (1) professional learning, (2) interest, and (3) enjoyment.

Professional development is cited by many sources. Handler (1989) suggests that a successor’s willingness to take over the firm increases if there is alignment with career needs. Dumas (1998) states that the decision to join a family business was partly guided by the expectation of connecting interests and educational training. A family business is also a place where daughters can receive personalized mentoring from their parents through socialization (Dumas, 1998).

Many authors have cited interest in work as a motivation to work in a family business (Handler, 1992; Dumas et al., 1995; Stavrou, 1998). These include the ability to control work tasks, being independent at work, and having interesting and challenging tasks (Dumas et al., 1995; Dumas, 1998).

Finally, working with family members can be enjoyable. Under certain assumptions, being family members means having similar tastes, reactions, sharing philosophy and values. There might be also other reasons, as noted by Constantinidis and Nelson (2009, p. 48): “Those with pull motivations enjoyed working in the family firm and wished to work with their parents.”

Daughters in family business who are intrinsically motivated spend more hours on work, are more proactive and eager to learn. Consequently, they will take on more responsibility as well as more difficult and challenging projects, and will learn more, both personally and professionally. Such an attitude will help them gain the respect of their colleagues. Thus, according to Mathew (2016) strong willingness to leadership and growth orientation may increase daughters’ likelihood of being selected as successor. This is confirmed by previous research. According to Dumas (1998) the individual characteristics of a daughter might affect her career dynamic. Cole (1997) suggested distinguishing between women who cannot advance due to barriers, and women who do not want to advance (p. 366-367). According to Dumas (1998), daughters with proactive or evolving vision of business have better chances of being recognized, promoted and supported by their family, than daughters with reactive vision. There is a big/ substantial amount of literature that supports the relation between personal characteristics (such as proactivity and eagerness to learn) and improved career outcomes, both objective and subjective (Judge, Cable, Boudreau, Bretz, 1994; Seibert, Crant and Kraimer, 1999; Seibert, Kraimer, Crant, 2001). Although, this might be subjected to the family structure (Curimbaba, 2002), there is a greater likelihood that parents will feel more confident to gradually share leadership responsibilities with daughters who are more confident in their business skills (Overbeke et al., 2013) seeing them as viable successors (Sharma, 2004).

Hypothesis 4: Daughters’ motivation based on intrinsic outcomes is negatively associated with perceived barriers to leadership.

Hypothesis 5: Daughters’ motivation based on intrinsic outcomes is positively associated with high positions in management.

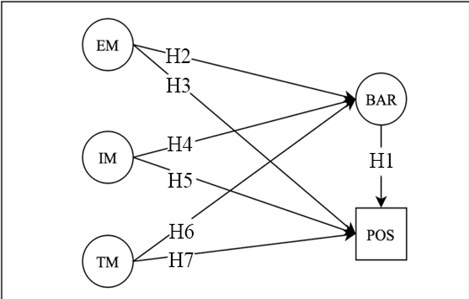

Figure 1 Hypotheses.

EM - Extrinsic motivation, IM – Intrinsic motivation, TM – Ethical motivation, BAR – Barriers, POS – Position

Ethical motivation

The anthropological theory denominates ethical motivation as “transcendent”. This motivation starts and sustains an activity that is done anticipating the reaction of another person, who is related to the company directly or indirectly; and, therefore is an ethical motivation. The review of literature on the next generation in family firms yielded the following areas of ethical motivation: (1) business contribution, (2) family contribution, and (3) social contribution.

Several aspects are included in business contribution. First, employee well-being might seem to be a socially desirable result for a company that has nothing to do with career choice. However, family businesses are often long-term oriented (Ward, 2016, p. 186); investing in employees and treating them as family members is logical. Thus, comparing a family firm to other companies, the next generation might prefer working, for instance, for a smaller but more responsible family company. In a similar vein, relationships with partners and customers are arguably the result of managerial “consistency” in interactions, and good relationships might be an attractive issue to consider. Finally, the ability to improve upon and contribute to the common goal: “family pride”, the product or service, perpetuation of the business in general, – can be motivation enough to enter the family firm (Sharma and Irwing, 2005; Dumas et al., 1995).

Contribution to family is an important issue in family business literature, especially because daughters in family business are often drawn to the business by a desire to help the family (Daspit, Holt, Christman and Long, 2016; Peters, Raich, Märk and Pichler, 2012), continue the family tradition, give back to the family, live the family dream, take care of parents, or create something to pass on to children (Salganicoff, 1990; Dumas, 1998; Vera and Dean, 2005, Murphy and Lambrechts, 2015), with salary being a secondary issue (Overbeke et al., 2013).

Finally, social contribution was rather hypothesized based on the literature about social emotional wealth (SEW) (Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia, 2012). According to this approach, in order to preserve their stock of socioemotional wealth, family business members often increasingly participate in different forms of corporate social responsibility, and in general, take a proactive stand towards external stakeholders of the firm.

Given that the high standards of daughters match that of the family, daughters in family business who are motivated ethically (or transcendently) may come to play a more indispensable role in the company by balancing the interests of the company, employees, clients, and partners. Having internalized family values, they are more likely to be examples of integral leaders, enjoying the respect of family and non-family employees, and so/ thus there is a higher possibility that parents would not impose barriers to leadership and that they will occupy higher positions.

Hypothesis 6: Daughters’ motivation based on ethical motivation is negatively associated with high barriers to leadership.

Hypothesis 7: Daughters’ motivation based on ethical motivation is positively associated with high positions in management.

The hypotheses are presented in figure 1.

Scale development: motivation and barriers

Existing scales of work motivation, such as the motivation at work scale (MAWS, Gagne et al. 2010), the work extrinsic and intrinsic motivation scale (WEIMS, Tremblay, 2009), and the situational motivation scale (SIMS, Guay, Vallerand, and Blanchard, 2000), are based on the self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2010) and therefore do not include ethical (transcendent) or pro social motivation. Neither of these scales is adapted for use within the family business context, which is a rather specific career path.

To be able to proceed, it was necessary to develop and validate measurement tools for motivation and barriers. Content validity (face validity) refers to the extent to which the meanings of a concept are captured by measures (e.g. Haynes, Richard, and Kubany, 1995). There are two basic approaches to item development: (1) using classification prior to data collection and (2) identifying constructs based on individual responses (Hinkin 1995, p. 969). Normally, only one approach is used to develop an item pool. In this research, in order to increase content validity, a two-fold approach was undertaken.

In the first step, the deductive or “classification from above” (Hinkin, 1995) approach was taken by developing theoretical conceptualization based on a literature review of motivational theories and academic literature on the next-generation perspective in family firms. As recommended by acceptable scale development practices (e.g. Churchill, 1979; DeVellis, 1991), an extensive item pool was created, consisting of 36 items for measuring motivation and 12 items for measuring barriers (Appendix 1 and 2). The items and sources are presented in Appendices A and B.

After that, an inductive approach, or “classification from below” (Hunt, 1991), was implemented by refining theoretical conceptualization through a series of in-depth interviews with a heterogeneous sample of daughters in family business. A purposefully formed sample consisting of 11 daughters in family business was used in order to refine, reduce, and transform the items. The sample was heterogeneous and comprised three types of females: (1) daughters in family business who succeeded their fathers as leaders and were actually in charge of the entire business, (2) daughters in family business who were in charge of a department (with the succession already in place or not), and (3) daughters in family business who left the family firm. Semi-structured interviews were conducted. The areas of interest included (1) motivation for and antecedents of/ reasons for entering the family firm, (2) motivation to continue working in the family firm, (3) motivation to take over the family firm (where applicable), and (4) motivation to leave the family firm (where applicable). The preliminary list of items was taken to each interview to monitor which types of motivation were covered by the interviewee. The interviewee was then asked about the items that she had not mentioned. Special attention was paid to how the interviewee formulated her motivation. As a result, it was possible to reduce the number of items measuring motivation from 36 to 21. The number of items measuring barriers remained the same.

Finally, data was collected from a self-selected sample and simplified by means of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Figure 2 shows the logic of procedures for scale development.

Data collection

The non-probability sampling, formed as a convenience sample with the SABI database, was used. We followed prior literature to impose certain restrictions to reach a set that would serve the goals of the study and allow to generalize/ the generalisation of results the results (Arosa et al., 2010; Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2014; Diéguez-Soto et al., 2015; Vandemaele and Vancauteren, 2015). For the purposes of this research, the family firm in this study needed to be managed and owned by at least two generations of family (Astrachan and Shanker, 2003). The database was searched by “region” (Catalonia, Madrid), “year of creation” (before 1965), and “gender” (directors, shareholders, female), and the preliminary number of companies obtained from the database was 2172: 1142 from Catalonia and 1030 from Madrid.

Table 1 sample description – companies.

|

Question |

Options |

(N) |

(%) |

|

Turnover last year available (Euro) |

Less than 1.000.000 |

9 |

11 % |

|

Between 1.000.000 and 5.000.000 |

27 |

36 % |

|

|

Between 5.000.000 and 20.000.000 |

21 |

18 % |

|

|

More than 40.000.000 |

6 |

9 % |

|

|

Mean |

11,266,000 |

||

|

Median |

3,992,000 |

||

|

Number of employees |

Less than 10 |

14 |

21 % |

|

Between 10 and 20 |

13 |

20 % |

|

|

Between 20 and 60 |

21 |

31 % |

|

|

Between 60 and 100 |

9 |

14 % |

|

|

Between 100 and 500 |

9 |

14 % |

|

|

Mean |

57 |

||

|

Median |

22 |

||

|

Generations |

2 |

40 |

60 % |

|

3 |

19 |

29 % |

|

|

4 |

5 |

8 % |

|

|

More than 5 |

2 |

3 % |

|

|

Total |

66 |

100 % |

|

|

Family members working in the company |

1 or 2 |

25 |

42 % |

|

3 or 4 |

21 |

28 % |

|

|

Between 5 and 10 |

19 |

28 % |

|

|

More than 10 |

1 |

2 % |

|

|

Total |

66 |

100 % |

|

|

Education |

University grade |

15 |

23% |

|

Master |

28 |

42% |

|

|

Master MBA |

18 |

27% |

|

|

PhD |

2 |

3% |

|

|

Total |

63 |

95% |

|

|

Years working in family firm |

Less than 5 |

4 |

6% |

|

Between 5 and 10 |

17 |

26% |

|

|

Between 10 and 20 |

32 |

48% |

|

|

More than 20 |

9 |

14% |

|

|

Total |

62 |

94% |

|

|

Position |

Basic level, internship |

0 |

0% |

|

Professional |

8 |

12% |

|

|

Head of Department |

33 |

50% |

|

|

In charge of the whole company |

25 |

38% |

|

|

Total |

66 |

100% |

|

The sample was screened several times in order to delete those in the process of liquidation, those too big (turnover more than 100 million Euro) or too small (turnover less than 200 thousand Euro), or those with a negative return on assets that was too large (less than -10). After adjusting to these criteria, a total number of 397 companies was approached by phone and asked to respond to the survey. During the telephone conversation the aim of the study was explained, so those who agreed to participate also identified themselves as a family business (Westhead and Cowling, 1998; Westhead et al., 2001; Astrachan, Klein, Smyrnios, 2002) and agreed with the fact that at least two generations are currently working in family business (Astrachan and Shanker, 2003).

The survey collected information about the number of generations, family members, and employees, position of the daughter, her level of education and work experience. It was mandatory to name the company. After two months, a total number of 66 responses were collected. (Table 1 and 2).

Questions related to position, barriers and motivation were mandatory, so there was no missing data. Questions were assessed on 1 to 5 Likert scale. All data was collected in one way, using Survey Monkey TM.

In order to validate the measurement tools, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was implemented in SPSS. Data for motivation and for barriers was computed separately.

Table 2 sample description by motivation and barriers.

|

Mean |

St. Dev. |

Median |

Min |

Max |

|

|

Extrinsic Motivation |

2,90 |

0,80 |

2,71 |

1,57 |

5 |

|

Intrinsic Motivation |

3,93 |

0,80 |

4,07 |

1,85 |

5 |

|

Ethical Motivation |

4,01 |

0,75 |

3,42 |

2 |

5 |

|

Barriers |

2,25 |

0,80 |

2,04 |

1,66 |

4,08 |

All variables were measured on 1-5 Likert scale.

EFA Motivation

Method of extraction: principal components analysis, Varimax rotation with Kaiser. Both the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index (0.760) and Bartlett’s test (X2 272.422; gl. 210; Sig. 0.000) indicated that factor analysis was appropriate for this data (Hair et al., 1998). Analysis of principal components indicated that three factors explained the 69.5% of variation in the sample.

The first factor was labelled “intrinsic motivation” (Interest: do interesting tasks; do challenging tasks; professional development: align career interests; develop professionally; enjoyment: do the work that I enjoy), the second “ethical motivation” (family contribution: help family; work for family; social contribution: provide benefit for others; business contribution: mentor employees), and the third “extrinsic motivation” (easy career: enter without barriers; have a reasonable income; monetary: have competitive income).

For samples between 60 and 70, Hair (Hair et al., 1998; Hair, 2010) recommends retaining items with factor loadings over 0.70 to achieve statistically significant results. We used even stricter criteria: all items that loaded less than 0.80 (e.g. poor convergent validity) or loaded simultaneously on two or three components greater than 0.35 (e.g. had poor discriminant validity) were deleted. Table 3 shows the retained items for measuring motivation.

Table 3 Exploratory factor analysis of motivations for joining the family business.

|

Item code |

Factors |

||

|

IM |

TM |

EM |

|

|

MI3 |

.915 |

||

|

MI1 |

.904 |

||

|

MI4 |

.884 |

||

|

MI6 |

.877 |

||

|

MI11 |

.820 |

||

|

MI8 |

.681 |

.384 |

|

|

MI2 |

.427 |

||

|

MT5 |

.896 |

||

|

MT6 |

.866 |

||

|

MT9 |

.827 |

||

|

MT1 |

.792 |

||

|

MT7 |

.777 |

||

|

MT8 |

.324 |

.770 |

|

|

MT2 |

.481 |

||

|

ME9 |

-.339 |

.841 |

|

|

ME10 |

.841 |

||

|

ME1 |

.817 |

||

|

ME8 |

-.324 |

.772 |

|

|

ME11 |

.306 |

.745 |

|

|

ME3 |

.741 |

||

|

ME5 |

.736 |

||

|

% of variation |

36.436 |

19.298 |

13.710 |

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

0.957 |

0.912 |

0.816 |

EM – Extrinsic motivation, IM – Intrinsic motivation, TM – Ethical motivation

EFA barriers

Both the KMO index (0.857) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (X2 482.923; g.l. 66; Sig. 0.000) indicated that factor analysis could be performed with these data. Principal components analysis showed that two factors explain 60% of the variation of the sample, and basically the first factor had the most power. The same criteria were used to retain items. In the two extracted factors, the first was labelled “barriers specific to family business” (role incongruity: family undervalued my ability to assume leadership; invisibility: I was forced in the position where I could not participate in strategic decisions; lack of family support: the family did not support me), and the second “conciliation” (needed to prioritize other areas; had problems reconciling work and family).

Table 4 Exploratory factor analysis of motivations in order to join the family business.

|

Item code |

Factors |

||

|

FB |

C |

||

|

V24 |

.869 |

||

|

V23 |

.851 |

||

|

V32 |

.794 |

.346 |

|

|

V25 |

.722 |

||

|

V22 |

.703 |

||

|

V29 |

.642 |

.309 |

|

|

V26 |

.599 |

.354 |

|

|

V33 |

.821 |

||

|

V28 |

.732 |

||

|

V30 |

.488 |

.671 |

|

|

V31 |

.506 |

.614 |

|

|

V27 |

.386 |

.490 |

|

|

% of variation |

50.724 |

10.462 |

|

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

0.911 |

||

FB – Barriers specific to family business, C – Conciliation

The factor “conciliation” was rejected because (1) it is not recommended to keep factors with less than three items (e.g. Brown, 2014), and (2) because the first factor had five times more explanative power. However, for future research it is recommended to explore this factor further.

Testing for direct causal effects

Structural equation modelling (SEM) is a series of statistical methods that allow complex relationships between one or more independent variables and one or more dependent variables to be identified. To check the initial hypothesis, EQS 6.1 was used, which was the most recent version of this software at the time the analysis was conducted.

Because the Mardia coefficient was high (6.12), the robust maximum likelihood method (ML) was used. CFI was 0.89, NNFI was 0.864, SRMR was 0.125, and RMSEA was 0.107 (90% CI set between 0.078 and 0.132). The Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square was 165.2 based on 95 degrees of freedom, and the probability was also very low at 0.00001, suggesting a suboptimal fit between the model and the data. The global fit was acceptable for an explorative study but not optimal (figure 3).

The Wald test was used in order to improve the model fit by reducing it. The resulting model can be seen in figure 4. The Mardia coefficient was high (8.44), indicating multivariate non-normality. Therefore, the measurement model was estimated with the robust maximum likelihood (ML) method. According to Bentler (2006), this procedure offers more accurate standard errors when data is not normally distributed.

The result showed that the suggested structure was relatively good and much better than the previous model. CFI was 0.94, NNFI was 0.922, SRMR was 0.088, and RMSEA was 0.087 (with CI interval between 0.047 and 0.122). The model fit was very good, taking into consideration, for example, that RMSEA tends to over-reject small samples (N < 250) (Hu and Bentler, 1998).

Two factors, ethical motivation and barriers, were robust in explaining position. The factor “intrinsic motivation” was not robust in explaining position. Further, the factor “ethical motivation” was robust in explaining barriers and “intrinsic motivation” almost met the criteria (t-value -1.698). There was covariance between the factors “ethical motivation” and “intrinsic motivation”.

Discussion

The goal of this paper is to develop an instrument to measure motivation and barriers that daughters face in family business and to empirically examine the relation of motivation and barriers to their position in the family firm. The first part of this article summarized the process of item generation and refinement, data collection, and scale validation. In the process of scale development, special attention was paid to theoretically defining constructs. This resulted in the successful development of motivational scale (Appendix C) and scale to measure barriers specific to family firms (Appendix D). Limitations apart, two scales showed an acceptable fit even for a small sample and could be used for a variety of purposes in future.

In the second part of the article, the theoretical model, based on the direct effect relationships of motivation and barriers on position, was checked by means of SEM. The general fit of factor structure of the original model was not optimal, but somewhat acceptable for an explorative study. It was decided to modify the model in order to improve the fit. By deleting the factor “extrinsic motivation”, the fit of the model significantly improved. Hypotheses 2 and 3 were rejected. Few explanations could be found to that. It could be that in the family firm, the relation between extrinsic motivation and career outcomes as well as barriers, are not straightforward and might be mediated by other types of motivation. On the one hand, the daughter might be motivated both extrinsically and ethically, and in this case, she will be acting rather pragmatically than as an agent and might be achieving high status in the family firm and experience low barriers. On the other hand, she might be motivated only extrinsically, and

behave as an agent. In this case, she might experience problems attaining a high position or prefer to stay in the background, while receiving financial benefits and enjoying a decreased workload.

According to SEM analysis, ethical motivation explained both position and barriers. A negative relationship was found between ethical motivation and barriers, confirming hypothesis 6, and a positive relationship found between ethical motivation and position, confirming hypothesis 7. In this sense, ethical motivation played an important role in determining the experience of a daughter in the family firm, by both reducing perception of barriers and increasing her chances of being promoted. Whilst the design of this study does not permit to suggest specific situations, when this occurs, this study can help orientate future research. We can speculate that when family values go in line with the ethical values of daughters, their contribution becomes noticed and they experience higher / more support from their family and fewer impediments to their career progression.

Ethical motivation (i.e. motivation to help family) might increase daughters’ commitment toward work in the family firm (Daspit et al., 2010; Peters et al., 2012).

Ethical motivation might also moderate the daughter’s relationship with other stakeholders: non-family employees, clients and partners, as her attitude might help her gain their respect as a viable successor, which is often is an issue (Cole, 1997). Thus, acting ethically, might also help daughters to establish their identity, which also seems to be a part of the complexity according to some authors (Deng, 2015; Hytti et al., 2017).

Additionally, the results can be interpreted in a way that variable “barriers” moderate the relation between ethical motivation and position (indirect effect 0.11, total effect 0.63). Indeed, daughters that are moved by the desire to be act in the best interest of external and internal stakeholders, would be more valued and praised. As a result, the surroundings would perceive them as viable successors. This results in daughters facing (or perceiving) fewer barriers and in them occupying a higher position (hypothesis 1).

The relationship between intrinsic motivation and position was not confirmed (hypothesis 5 was rejected), but the relationship between intrinsic motivation and barriers (hypothesis 4) seemed to be “almost robust”. It is probable that in a bigger sample this relationship would have been confirmed. The negative effect of barriers on position (hypothesis 1) was also confirmed. In general, the negative effect of barriers on position is smaller than one would expect (hypothesis 1). There might be several explanations. Given that on average means for barriers were relatively low (table 2), daughters might be refusing to acknowledge unequal treatment, or might justify it (Gherardi and Perrotta, 2016). On the other hand, it might be that barriers are no longer playing an important role in preventing daughters from moving along their career path. In our study we witnessed that motivational effects are quite strong.

Finally, the study has found significant co-variation between intrinsic motivation and ethical motivation. This suggests that when daughters are motivated ethically (transcendently) they are also motivated intrinsically most of the time: coping with interesting and challenging tasks, developing professionally and enjoying their work. And vice versa: when daughters enjoy their work in different ways (autonomy, interest, professional growth, enjoyment), they are also inclined to act in the best interest of others. In general, this goes in line with previous research, that suggests that a synergy between pro-social and intrinsic motivation exists that fosters persistence, performance, creativity and productivity (Grant, 2008; Grant and Berry, 2011). Similarly, as is predicted by self-determination theory, extrinsic motivation seems to be crowding-out intrinsic motivation (Gagne and Deci, 2005).

Collectively, the results of SEM analysis can be summarized in the following way:

1. The position of a daughter in family business is higher when she has (1) high ethical motivation and (2) low perception of barriers.

2. The decreased perception of barriers coincides with (1) increased ethical motivation and (2) increased intrinsic motivation (this link should be the subject of future research).

Thus, daughters in family business who act out of ethical considerations (ethical motivation) obtain, in the long run, greater recognition by their colleagues and subordinates and seem to face fewer barriers. Daughters in family business motivated ethically towards different stakeholders come to play a more indispensable role in the company by balancing the interests of the company, employees, clients, and partners. Having internalized family values, they represent integral leaders who are respected by family and non-family employees.

Limitations

In this paper, researchers took a positivist worldview. The main concern of positivist research is to conduct an unbiased and objective investigation. Despite following established practice procedures, this study is not without limitations:

1. The sample size was somewhat smaller than expected due to the low response rate. This issue created the biggest challenges for researchers. Thus, the low response rate prevented the conducting of the test-retest procedure as is suggested by the best practices for scale development (e.g. DeVellis, 1991).

2. The second concern was the representativeness of the sample. As previously mentioned, this sample was a convenient sample that was skewed towards older companies.

Apart from general limitations, the researchers acknowledge limitations at each step of research.

Limitations of scale development

The scale requires further research to examine the relationship between it and existing instruments and related constructs. Discriminant validity and convergent validity were tested at the stage of exploratory factor analysis. However, stricter research could have been implemented to relate the new scale of motivation to existing scales.

Nomological validity could have been established by testing against conceptually related constructs (e.g. “commitment”). In the process of scale development, the evidence of nomological validity was not established because the area of research is underdeveloped. Unidimensionality was not tested by confirmatory factor analysis.

It should be noted that, as with most measures developed for specific purposes, this tool has its inherent limitations. In the future, the scale may be tested on more general samples, for example females with family business background employed outside the family business or a mixed gender sample employed in a family business. Finally, researchers should also note that the current investigation was undertaken on a national sample and its application on an international sample will probably require some adaptations.

Limitation of structural equation modelling

The limitation of SEM analysis was the small sample size. Bentler and Mooijaart (1989) suggested a 5:1 ratio of sample size to free parameters, which would make a minimum sample size of 155 to test the improved model (which had 31 free parameters). Given that the study complies with less strict recommendations concerning the minimum sample size, which can be found in literature (“rule of 10 observations per variable” Nunnally (1967)), it is suggested to view the results with much caution, considering them as explorative. Further, in the discussion section we reflect upon the mediator effect of barriers on the relation between ethical motivation and position. The goal of the study was not to test this effect; however, for future research, the mediating effect should have been tested by a bootstrapping method.

Contributions and future research

This article makes important contributions to the stream of research on the under-representation of daughters in family business in high-level management positions. The findings have important managerial implications that can be used by family business consultants and leadership coaches in order to develop leadership programs. Theoretically, the article successfully applies the anthropological theory (Pérez López, 1991) to the case of daughters in family business, which can also be considered by other researchers. Methodologically, as a spin-off of this investigation, a scale to measure motivation and barriers specific to family firms was developed and validated. This instrument might open doors to quantitative research in this area that to date relied primarily on qualitative investigation. In general, we encourage future quantitative investigation into the problem of the gender gap in management positions in family business, as to date, most of the studies are based on qualitative studies, with a common limitation of generalizability of studies. Future studies might obviously investigate other areas. In general, antecedents of taking the decision to enter the family firm, instead of taking other career possibilities; antecedents of taking the decision to succeed the family firm, remain obscure. Also, it is not clear how some characteristics of daughters, such as motivation, might affect the transfer of knowledge and social capital between incumbent and the next generation, that usually happens before the succession takes place

References

Ahrens, J. P., Landmann, A., & Woywode, M. (2015). Gender preferences in the CEO successions of family firms: Family characteristics and human capital of the successor. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(2), 86-103.

Akhmedova, A., Cavallotti, R., & Marimon, F. (2015). What Makes a Woman to Choose to Work in a Family Company Instead of a Looking for a Position in the Work Market or Creating Her Own Company?: a Literature Review. European Accounting and Management Review, Vol. 2 (1), 85-106.

Arosa, B., Iturralde, T., & Maseda, A. (2010). Ownership structure and firm performance in non-listed firms: Evidence from Spain. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1(2), 88-96.

Astrachan, J. H., & Shanker, M. C. (2003). Family businesses’ contribution to the US economy: A closer look. Family business review, 16(3), 211-219.

Astrachan, J. H., Klein, S. B., & Smyrnios, K. X. (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem1. Family business review, 15(1), 45-58.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Macmillan.

Bem, S. L. (1993). The lenses of gender: Transforming the debate on sexual inequality. Yale University Press.

Bentler, P. M. (2006). EQS 6 structural equations program manual.

Bentler, P. M., & Mooijaart, A. B. (1989). Choice of structural model via parsimony: a rationale based on precision. Psychological bulletin, 106(2), 315.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279.

Brown, T. A. (2014). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. Guilford Publications.

Cabrera-Suárez, M. K., Déniz-Déniz, M. D. L. C., & Martín-Santana, J. D. (2014). The setting of non-financial goals in the family firm: The influence of family climate and identification. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(3), 289-299.

Casillas Bueno, J. C., López Fernández, M. C., Pons Vigués, A., Baiges Giménez, R., and Meroño Cerdán, Á. (2015). “La empresa familiar en España (2015).” Instituto de la Empresa Familiar. Accessed September 13, 2017. http://www.iefamiliar.com/upload/documentos/ubhiccx9o8nnzc7i.pdf.

Churchill Jr, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of marketing research, 64-73.

Cole, P. M. (1997). Women in family business. Family Business Review, 10(4), 353-371.

Constantinidis, C., & Nelson, T. (2009). Integrating succession and gender issues from the perspective of the daughter of family enterprise: A cross-national investigation. Management international/International Management/Gestiòn Internacional, 14(1), 43-54.

Curimbaba, F. (2002). The dynamics of women’s roles as family business managers. Family Business Review, 15(3), 239-252.

Daspit, J. J., Holt, D. T., Chrisman, J. J., & Long, R. G. (2016). Examining family firm succession from a social exchange perspective: a multiphase, multistakeholder review. Family Business Review, 29(1), 44-64.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Self‐determination. John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

Deng, X. (2015). Father-daughter succession in China: facilitators and challenges. Journal of Family Business Management, 5(1), 38-54.

DeVellis, R. F. (1991). Scale development: Theory and applications (Vol. 26). Sage publications.

Diéguez-Soto, J., López-Delgado, P., & Rojo-Ramírez, A. (2015). Identifying and classifying family businesses. Review of Managerial Science, 9(3), 603-634.

Dumas, C. (1989). Understanding of father-daughter and father-son dyads in family-owned businesses. Family Business Review, 2(1), 31-46.

Dumas, C. (1992). Integrating the daughter into family business management. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 16(4), 41-56.

Dumas, C. (1998). Women’s pathways to participation and leadership in the family-owned firm. Family Business Review, 11(3), 219-228.

Dumas, C., Dupuis, J. P., Richer, F., & St.-Cyr, L. (1995). Factors that influence the next generation’s decision to take over the family farm. Family Business Review, 8(2), 99-120.

Eagly, A. H. (2003). More women at the top: The impact of gender roles and leadership style. In Gender—from Costs to Benefits (pp. 151-169). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological review, 109(3), 573.

Ely, R. J., Ibarra, H., & Kolb, D. M. (2011). Taking gender into account: Theory and design for women’s leadership development programs. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(3), 474-493.

Englisch, P., Hall, C., Burgess, I., and Hara, M. (2015). “Women in Leadership: Family Business Advantage. Special Report Based on a Global Survey of the World’s Largest Family Businesses.” EYGM Limited. Accessed September 13, 2017. http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-women-in-leadership-the-family-business-advantage/$FILE/ey-women-in-leadership-the-family-business-advantage.pdf.

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self‐determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational behavior, 26(4), 331-362.

Gagne, M., Forest, J., Gilbert, M. H., Aubé, C., Morin, E., & Malorni, A. (2010). The Motivation at Work Scale: Validation evidence in two languages. Educational and psychological measurement, 70(4), 628-646.

Gherardi, S., & Perrotta, M. (2016). Daughters taking over the family business: Their justification work within a dual regime of engagement. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 28-47

Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the pro-social fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of applied psychology, 93(1), 48.

Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of management journal, 54(1), 73-96.

Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2000). On the assessment of situational intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motivation and emotion, 24(3), 175-213.

Gupta, V., & Levenburg, N. M. (2013). 16 Women in family business: three generations of research. Handbook of research on family business, 346.

Haberman, H., & Danes, S. M. (2007). Father-daughter and father-son family business management transfer comparison: Family FIRO model application. Family Business Review, 20(2), 163-184.

Hair, J. F. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson College Division. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 207-219). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice hall.

Handler, W. C. (1989). Methodological issues and considerations in studying family businesses. Family business review, 2(3), 257-276.

Haynes, S. N., Richard, D., & Kubany, E. S. (1995). Content validity in psychological assessment: a functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychological assessment, 7(3), 238.

Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of management, 21(5), 967-988.

Hollander, B. S., & Bukowitz, W. R. (1990). Women, family culture, and family business. Family Business Review, 3(2), 139-151.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological methods, 3(4), 424.

Hunt, S. D. (1991). Modern Marketing Theory: Critical Issues in the Philosophy of Marketing Science. South-Western Pub.

Hytti, U., Alsos, G. A., Heinonen, J., & Ljunggren, E. (2017). Navigating the family business: A gendered analysis of identity construction of daughters. International Small Business Journal, 35(6), 665-686.

Iannarelli, C. L. (1992). The Socialization of Leaders: A Study of Gender in Family Business. PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh.

Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Boudreau, J. W., & Bretz Jr, R. D. (1995). An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Personnel psychology, 48(3), 485-519.

Keating, N. C., & Little, H. M. (1997). Choosing the successor in New Zealand family farms. Family Business Review, 10(2), 157-171.

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms.

L. Glover, J. (2014). Gender, power and succession in family farm business. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 276-295.

Martinez Jimenez, R. (2009). Research on women in family firms: Current status and future directions. Family Business Review, 22(1), 53-64.

Mathew, V. (2016). Women and family business succession in Asia-characteristics, challenges and chauvinism. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 27(2-3), 410-424.

McDonald, S. (2011). What’s in the “old boys” network? Accessing social capital in gendered and racialized networks. Social networks, 33(4), 317-330.

Murphy, L., & Lambrechts, F. (2015). Investigating the actual career decisions of the next generation: The impact of family business involvement. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(1), 33-44.

Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric Theory (1st ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Otten-Pappas, D. (2013). The female perspective on family business successor commitment. Journal of Family Business Management, 3(1), 8-23.

Overbeke, K. K., Bilimoria, D., & Perelli, S. (2013). The dearth of daughter successors in family businesses: Gendered norms, blindness to possibility, and invisibility. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 4(3), 201-212.

Pascual García, C. (2013). Empresa familiar: mujer y sucesión.

Pérez López, J. A. (1991). Teoría de la acción humana en las organizaciones: la acción personal (Vol. 6). Ediciones Rialp.

Pérez López, J. A. (1993). Fundamentos de la dirección de empresas (Vol. 31). Ediciones Rialp.

Pérez López, J. A. (1997). Liderazgo. Ediciones Folio.

Peters, M., Raich, M., Märk, S., & Pichler, S. (2012). The role of commitment in the succession of hospitality businesses. Tourism Review, 67(2), 45-60.

Rosenblatt, P. C. (1985). The Family in Business. Jossey-Bass.

Salganicoff, M. (1990). Women in family businesses: Challenges and opportunities. Family Business Review, 3(2), 125-137.

Schröder, E., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., & Arnaud, N. (2011). Career choice intentions of adolescents with a family business background. Family Business Review, 24(4), 305-321.

Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. Journal of applied psychology, 84(3), 416.

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Crant, J. M. (2001). What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel psychology, 54(4), 845-874.

Sharma, P. (2004). An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future. Family business review, 17(1), 1-36.

Sharma, P., & Irving, P. G. (2005). Four bases of family business successor commitment: Antecedents and consequences. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 13-33.

Stavrou, E. T. (1998). A four factor model: A guide to planning next generation involvement in the family firm. Family Business Review, 11(2), 135-142.

Steinbrecher, H., Hyde S., Pound, O., Bokpé, A., Rodwell, S. (2016). PwC Next Generation Survey 2016: The Female Perspective. A special release of the Next Generation Survey. Accessed September 13,2017. http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/family-businessservices/assets/Next_Generation_Survey_ Female_Perspective_Final.pdf.

Tremblay, M. A., Blanchard, C. M., Taylor, S., Pelletier, L. G., & Villeneuve, M. (2009). Work Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation Scale: Its value for organizational psychology research. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 41(4), 213.

Vandemaele, S., & Vancauteren, M. (2015). Nonfinancial goals, governance, and dividend payout in private family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 166-182.

Vera, C. F., & Dean, M. A. (2005). An examination of the challenges daughters face in family business succession. Family Business Review, 18(4), 321-345.

Wang, C. (2010). Daughter exclusion in family business succession: A review of the literature. Journal of family and economic issues, 31(4), 475-484.

Ward, J. (2016). Keeping the family business healthy: How to plan for continuing growth, profitability, and family leadership. Springer.

Westhead, P., & Cowling, M. (1998). Family firm research: The need for a methodological rethink. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(1), 31-56.

Westhead, P., Cowling, M., & Howorth, C. (2001). The development of family companies: Management and ownership imperatives. Family Business Review, 14(4), 369-385.