|

|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Vegetarian Restaurants as a Determining Factor of the Vegetarian Tourist’s Destination Choice

Jesus Molina Gomez a, Maria Ruiz Ruiz a , Pere Mercade Meleb

a Departamento de Economía y Administración de Empresas. Universidad de Málaga (Spain).

b Departamento o de Estadística y Econometría. Universidad de Málaga (Spain).

Received 8 March 2018; accepted 23 April 2018

Available online 30 june 2018

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M1

KEYWORDS

vegetarian tourist, touristic destination,

choice of destination, vegetarian restaurants,

family business

Abstract Spain is a country that welcomes millions of tourists every year; among those travelers there are vegetarians and other individuals who opt for a vegetarian diet during their trips either due to health, religion or other reasons.

The interest from the touristic businesses, especially the food and beverage sector, is constantly moving towards a healthier and more innovative cuisine. In numerous occasions, there is no clear vision of the preferences in certain segments of the market in which aspects such as the present one are considered essential.

It is a sector that is currently developing, but that still has a long road ahead. Understanding the factors that shape the decision of a vegetarian tourist’s destination choice can help us appreciate the importance of this touristic sector with an infrastructure that is vastly (95 %) controlled by family-owned businesses (Fehr, 2016).

The main objective of this research study is to understand the factors that determine the destination choice of the vegetarian tourist; to this end, we have provided a structured survey to 400 participants and obtained concrete conclusions of the problem to be analyzed.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M1

PALABRAS CLAVE

turista vegetariano, destino turístico, elección del destino, restauración vegetariana, empresa familiar

La Restauración Vegetariana como factor determinante en la elección del destino del turista vegetariano.

Resumen España es un país que mueve millones de turistas al año y entre ellos hay vegetarianos o personas que pueden optar por una alimentación vegetariana en sus viajes ya sea por salud, religión u otros motivos.

Día a día crece el interés por parte de las empresas turísticas y concretamente el sector de la restauración por una cocina más saludable e innovadora y en muchas ocasiones no tenemos una visión clara de las preferencias de ciertos segmentos del mercado donde este tipo de aspectos se torna como fundamental.

Es un sector que actualmente se está desarrollando, pero que aún le queda mucho camino por recorrer; ver aquellos factores que ayudan a la toma de decisión de un destino turístico por parte de un turista vegetariano, hará darnos cuenta de la importancia de este sector en el turismo, donde más del 95% de la infraestructura está dominada por la empresa familiar (Fehr, 2016).

El objetivo principal en este trabajo de investigación es conocer los factores determinantes en la elección del destino por parte del turista vegetariano; para ello hemos realizado una encuesta estructurada a 400 personas, obteniendo conclusiones concretas a la problemática analizada.

Introduction

For millions of tourists, nutrition is a secondary element during their trips. It simply covers the biological function of supplying the body with the necessary nutrition for their sustenance. Torres Bernier (2003) argues that there are tourists that “feed themselves” and others that “travel to eat”; the first kind just needs to eat, in other words, food does not motivate them to travel, instead they feed themselves out of necessity. On the other hand, the second kind is indeed interested in enjoying the food, in other words, gastronomic tourism.

In fact, if the data related to the vegetarian sectors is analyzed, it can be observed that there is quite a growing demand and a lack of infrastructure to service it (Saz-Peiro, el Ruste, & Saz-Tejero, 2013).

It can be asserted that a vegetable-based diet is a clear tendency in Spain, where 43 % of Spaniards have reduced their red meat consumption in 2016 (Camargo, 2017). This is the first step towards a process of change that, according to Diaz (2014), has turned 55 % of non-vegetarian individuals into vegetarians and a 10 % of non-vegetarians into vegans.

In the framework of it all, it should not be forgotten that this is a business that generates 4,000 million dollars per year and is growing at a rate of 6 % annually (Veguillas, 2017). During the last 5 years, the number of restaurants has increased and reached a total of 800 in 2016. Based on these numbers it can be affirmed that 95 % of these types of restaurants in Spain are family-owned businesses (Ferh, 2016). Additionally, 6.8 % of the restaurants per million residents in Spain are currently vegetarian.

Regardless of the polemics that surround the nutritional value of the vegetarian diet, there are studies such as the one performed by the American Dietetic Association and the Dietitians of Canada that concluded that a well-elaborated vegetarian diet is adequate during any stage of the life cycle and supplies all the necessary nutrients (Brignardello et al., 2013).

This information helps to obtain more knowledge about the different aspects and behaviors of the target group, acquiring previous knowledge about this group and the problem that surrounds it; consequently, it can be related to the food and beverage sector with the aim of adapting the offer to the growing demand (Malhotra, 2004).

Therefore, this research study focuses on the behavior of the vegetarian tourist, directing its attention to the characteristics that influence the priority they assign to their nutrition when it comes to choosing a touristic destination; factors such as gender, age, nationality and income level could be determining factors.

This research study can be thought of as an analysis that focuses on an opening of information about this group for those public or private institutions that want to use it in order to improve their future perspectives, by including this sector in their business plans.

Theoretical framework

Vegetarian gastronomic tourism

Vegetarianism is considered a nutritional regime based on the consumption of vegetables, including eggs, dairy and honey, among others. It excludes all kinds of meat, poultry and fish (Nelson et al., 1996). The classifications emerge due to the type of animal-based food that is excluded in the nutrition and Cayllante (2014) has defined the type of vegetarians there are. The most popular ones are summarized in the following table.

Table no.1: types of vegetarians

|

Name of the diet |

Food |

|||

|

Meat |

Eggs |

Dairy |

Fish |

|

|

Vegetarian |

NO |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

Strict vegetarian/vegan |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

|

Lacto-ovo vegetarian |

NO |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

Lacto vegetarian |

NO |

NO |

YES |

NO |

|

Ovo vegetarian |

NO |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Fruitarian* |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

|

Raw vegan** |

NO |

NO |

NO |

NO |

Source: developed by authors.

Authors such as Haas (2017) and Camargo (2017) also introduce concepts such as flexitarian (those who consume mean and fish sporadically), pescatarian (those who consume fish and sea food, but not meat) or the term meat reducer. Pescetarianism is considered a more rigorous variant than the previous one because it is limited to the consumption of fish and sea food. In recent years, multiple discussions have emerged since there are many who do not consider it to be a variant of vegetarianism due to the consumption of fish.

Vegetarianism is a current trend preceded by a long journey through history where many authors have been vegetarian and have defined the stance. Since then, an endless amount of philosophers such as Descartes or Kafka have preached this lifestyle (Saz-Peiro, Del Ruste, M. M., & Saz-Tejero, 2013).

Such lifestyle has influenced tourism. The ever present gastronomy surfaced as a phenomenon in the touristic activity around the XXI century when tourists started to search for a way to experience their destinations differently, through their senses, thus emerging the gastronomic tourism (Riley, 2005) and making a clear distinction between tourists who eat out necessity or those who travel to eat (Torres Bernier, 2003).

Gastronomy inspires trips for a large number of tourists (Oliveira, 2011), if this is applied to the gastronomic tourist, the four categories that have been described by Fields (2002) emerge:

• Physical motivation: originates from the need to eat that people experience.

• Cultural motivation: stems from the urge to deeply explore a geographical region or its culture.

• Interpersonal motivation: those who manifest as a reflection of the social functions.

• Status and prestige motivation: determined by the sought after social status.

The correlation that could emerge between gastronomy, tourism and the motivation, would lead to 4 proposals, according to Tikkanen (2007):

• Gastronomy as a touristic product.

• Gastronomy as part of the touristic experience.

• Gastronomy as part of the culture.

• Relation between tourism and food production.

Based on the model created by Quan and Wang (2004) which focuses on the tourists’ motivations (primary and secondary) that originate when they travel, some differences emerge between the actions performed during the trip and their daily routine. These elements can be related in three different ways: by contrast, intensification and extension. The type of motivation, primary or secondary, could be related in the following way:

• Contrast: the tourist chooses a destination where the flavors are completely different to their place of residence.

• Intensification: the traveler chooses a destination where the gastronomy reinforces the diet that is normally consumed.

• Extension: the tourist consumes what they normally consume at home.

Lopez-Guzman and Sanchez Cañizares (2012) state in their research study that gastronomic tourism could promote a destination due to the increasing tourist enthusiasm to get to know the culinary art of each place, regarding it as a main factor or as part of the experience. However, it is not always easy to access delicious and healthy food in every destination (González, 2012), taking into account that every individual has different gastronomical preferences which creates completely different settings in every part of the world.

Choice of touristic destination

Motivation is the main factor when it comes to choosing a touristic destination (Millet, 2010); for the gastronomical tourist these motivations have already been cited (Oliveira, 2011; Fields, 2002). The vegetarian tourist could be considered a gastronomic tourist since they are guided by their type of nutrition (Tikkanen, 2007). The tourist or groups of tourists as the main decision makers of the destination choice look to satisfy their needs. When it is a group, provided that a hierarchical power of some group member is not exerted (Eymann & Ronning, 1997), it is understood that the decision is unanimous. Each individual has different tastes and preferences; therefore, the sought after option is one that maximizes the experience. A satisfied need results into a pleasant and desirable experience. However, an ill-satisfied need could lead to a poor image of the destination, although a second experience in the same destination may not have the same result (Morley, 1994).

A vacation destination is acknowledged depending on the familiarity, reputation, trust and satisfaction factors that are associated with the place (Millet, 2010), projecting an image that will be the main attracting source for the tourist. Each destination focuses their touristic attractions towards a market, keeping the promoted and perceived image as similar as possible (Kotler, Haider & Rein, 1993).

The image that a touristic destination projects is considered to be a source of attraction within the selection process (Andreu, Bigne & Cooper, 2000). The objective of the promoters of a specific touristic destination should be to obtain similarities between the promoted image and the image the potential tourist perceives (Kotler, Haider & Rein, 1993), in order to advertise a truthful image that is attainable (Lawson & Baud-Bovy, 1977). To deceive the tourist could have a devastating cost. Kotler, Haider and Rein (1993) affirm that some touristic destinations exude a positive image and others a negative image. However, most destinations have a mixture of both. It is only when the positive image of the touristic destination exceeds its negative image, that an individual chooses this destination among other available destinations (Beerli & Martin, 2004).

A destination will be more attractive for the gastronomical tourist according on the existing relationship between the cuisine and the deep-rooted culture of the place (Riley, 2005). There are several motivating factors that drive the gastronomical tourist to choose between one place and another. According to Tikkannen (2007), depending on the link established between gastronomy, tourism and motivation, the destination will use the vegetarian gastronomy to attract the vegetarian tourist in the following ways:

• Cultivating factor: the vegetarian cuisine is the most developed factor (gastronomy as part of the touristic product).

• Experience factor: the vegetarian tourist acquires experience and learns about new flavors.

• Cultural factor: the tourist can try vegetarian dishes and learn a little bit about the culture at the same time. Culinary expos are ideal for this purpose.

• Gastronomic- vegetarian routes: a relation between tourism and food production is established.

According to several studies such as “Un análisis de las personas vegetarianas en la Universidad de La Laguna” (an analysis of vegetarians at the University of La Laguna) by Ruben Dominguez Alvarez (2015), a predominantly vegetarian profile among women is accentuated. Also, Diaz Carmona (2012) mentions in her study that women express more concern and empathy towards animals, oppose to animal testing, have a more developed sense of disgust and are less receptive to consume meat. Meat is also associated to the opposing gender as a sign of masculinity and power (Orellana, Sepulveda & Denegri, 2013). This could be a causing factor of the greater implementation of vegetarianism among females than males.

Vegetarian restaurants as an example of a family business

Spain has more than 73,000 restaurants (Fehr, 2016) and is looking for a way to build a niche inside the vegetarian sector. This type of restaurant, categorized as a specialty restaurant, has increased its number of businesses in the recent years. In 2011, 353 vegetarian restaurants were registered in Spain compared to 703 in 2016 (Veguillas, 2017).

According to Fehr (2016), in Spain there are around 1,300 vegetarian and vegan restaurants. This number also includes those that offer vegetarian options.

This type of business is very difficult to analyze due to the privacy of their files, their restricted nature and the fact that they do not share their results (Lansberg, 1994). It can also be affirmed that more than 95 % of the businesses in this sector are family-owned (Fehr, 2016).

A clear example is the first vegetarian restaurant Casa Hiltl which opened its doors in 1903 and is now managed by the fourth family generation. They expect the business to continue to being managed by their future generations (Miller & Le-Breton, 2005).

The assumption of risk is a common denominator for all businesses. However, a family business does not assume as much of a risk as one that is not family-owned since the family’s property wealth is linked to the business (Wright et al., 1996). For this reason, businesses in this sector expand nationally, as no family business with a restaurant chain outside the national boarders has been found (Fehr, 2016). Likewise, since such family businesses are consolidated within the national market, well integrated in the culture and its needs, the international expansion is perceived as a less attractive strategy.

Vegetarian restaurants generate 4,000 million dollars per year and are increasing at a rate of 6 % annually (Veguillas, 2017). There is no concrete data in Spain about the percentage of people who are vegetarian, but the Spanish Agencia de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition) (2011) has presented data about the Encuesta Nacional de Ingesta Dietética Española (National Survey of the Spanish Dietary Intake) (Enide, 2011), which indicates that around 700,000 people in Spain do not consume meat or fish.

In recent years bars and restaurants have adopted certain rules such as the inclusion of information about the ingredients included in certain dishes, commonly called the allergen menu. This menu specifies the vegetarian and vegan dishes, among others. The regulation that enforces such rules is stated below:

·»REGULATION (EU) NO. 1169/2011 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 25th of October of 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers, amending Regulations (EC) no. 1924/2006 and (EC) No. 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No. 608/2004”

Two million Spaniards suffer from some type of food allergy, according to the Spanish Sociedad de Alergología e Inmunología Clínica (Spanish Association of Clinical Allergology and Immunology) (Seaic, 2016).

In other countries such as the U.S.A., vegetarianism is a lot more consolidated (Montalvo, 2010); more research has been performed and for many vegetarian tourists it is a destination where they can visit without having to worry about their nutrition. Spain stands out due to its increase of this type of restaurants. Nevertheless, it is still behind countries such as Austria and the Czech Republic (Molinero, 2016).

In Spain, there is a need that is not being fulfilled (Lilien et al., 1992) and some have seen this as a business opportunity. In fact, in the recent years there has been a noticeable increase in vegetarian restaurants, menu expansions and some cities even stand out due to their abundance of restaurants in this sector. Since it is a very new market that has not experienced a lot of research, there is not as much competition as there is in any other touristic sector. There is still a long road ahead and many innovations to be created.

Jakub (2016) searched for the most vegetarian countries in Europe and created this map by calculating each country’s score by number of vegetarian restaurants per one million residents.

Material and methods

Tools, sampling and data collection

This research study aimed to delve deeper into the vegetarian touristic sector and how it behaves when choosing a touristic destination. To this end, it was essential to provide a questionnaire in order to extract conclusive data that could help add reliability to this model. A structured questionnaire based on the information needed was created. The first part of the survey dealt with descriptive information regarding the target population, while the second gathered the information about the behavior of such population. In order to grant more reliability to the study, these groups were targeted through associations and interest groups both in-person and online. These played an essential role for the spread and collection of the information that was needed in order to obtain as many answers and make this research study more representative.

Table no. 2: No. of vegetarian restaurants per one million residents

(Expressed in percentages)

|

Spain |

6.8% |

Slovenia |

9.7% |

|

|

Portugal |

9.5% |

Czech Republic |

13.7% |

|

|

Andorra |

12.6% |

Croatia |

5.4% |

|

|

France |

2.7% |

Hungry |

5.4% |

|

|

Belgium |

5.8% |

Slovakia |

7.2% |

|

|

Luxemburg |

11.0% |

Poland |

5.3% |

|

|

Switzerland |

9.5% |

Lithuania |

11.5% |

|

|

Italy |

6.4% |

Latvia |

5.8% |

|

|

United Kingdom |

11.3% |

Estonia |

8.3% |

|

|

Ireland |

7.6% |

Finland |

9.7% |

|

|

Netherlands |

8.9% |

Sweden |

11.1% |

|

|

Germany |

7.2% |

Norway |

5.5% |

|

|

Denmark |

6.1% |

Iceland |

24.8% |

|

|

Austria |

13.8% |

|||

Source: http://www.playgroundmag.net/food/queda-mapa-ciudades-vegetarianas-mundo_0_1841815814.html.

The research study was developed between January and August of 2017 and the geographic area encompassed all of Spain. The data was collected through a direct questionnaire with a simple random sample of 400 surveyed, out of the 700,000 vegetarians in Spain, according to the Spanish Agencia Alimentaria y Nutrición (Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition).

Table no. 3: Fact Sheet

|

Geographical area |

Spain |

|

Population |

Vegetarian tourist |

|

Population size |

700,000 |

|

Sample type |

Simple random sample |

|

Sample size |

400 surveyed |

|

Survey type |

In-person and online questionnaire |

|

Field work |

January through August, 2017 |

|

Participation percentage |

100 % |

|

Sampling error |

4.90 %, assuming p=q=0.5 and a confidence level of 95 % |

Source: developed by authors

Table no. 3 shows a summary of the detailed information regarding the technical matters of the

Based on a simple random sampling (s.r.s) for a confidence level of 95 %, the most unfavorable hypothesis (p=q=0.5) and an increase in data error for the estimate of the proportion of 4.90%.

Hypothesis of the research study

This study aimed to examine if there are any differences between the averages of the two independent population groups (Hair et al., 2005); that is to say, if the individuals in one area are different to those in another area.

In this case, the differences in the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling according to gender, age, nationality, income and level of education were analyzed.

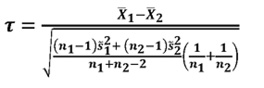

To this end, two hypotheses were analyzed; the first one is called the null hypothesis (H0) which indicates that there are no significant differences between the two populations; and the second hypothesis, called the alternative hypothesis (H1), indicates that there are significant differences between the two target populations. The statistical formula is as follows:

H0: µ1 = µ2

H1: µ1 ≠ µ2

And the test statistic is as follows:

͠ t n1 +n2-2

The contrast is bilateral and it is analyzed if the test statistic value falls inside or outside of the acceptance region. If it falls within the acceptance region, the null hypothesis is accepted, thus, there are no significant differences between the two populations; if it falls outside the acceptance region, in other words, inside the critical region, the null hypothesis is rejected and it can be concluded that there are significant differences between the average of the two populations (Hair et al., 2005).

Therefore, the hypotheses that were performed are as follows:

H0: There are no significant differences in the priority given to nutrition when traveling according to gender, age, nationality, income and level of education.

H1: There are significant differences in the priority given to nutrition when traveling according to gender, age, nationality, income and level of education.

In order to perform a more detailed analysis, the last part of this study analyzed if the nutritional satisfaction exerts a positive effect on the overall image of the destination.

Results analysis

Profile of the vegetarian tourist

The following table no. 4 shows a detailed analysis of the most important characteristics of the analyzed sample, such as age, sex, level of education, employment status and type of vegetarian.

Based on the information shown, a higher percentage of women with a high level of education, a medium income level, being employed and considering herself to be a strict vegetarian/vegan can be observed.

Table no. 4: summary table of the vegetarian tourist profile.

Source: developed by authors

|

Age and gender: vegetarian tourists are between the ages of 18 and 30 years of age (58 %). Regarding the gender, 89 % are female and 11 % are male. |

|

Level of education: the vast majority has a university degree (72.80 %), followed by secondary studies (25.40 %) and primary studies (1.80 %). |

|

Income level: the majority have a medium income level (38.70 %), followed by a medium-low income level (30.70 %). |

|

Employment status: a high percentage of the respondents have a job (53.30 %), and the retirees are found to be the other extreme (1.80 %). |

|

Type of vegetarian: The most abundant tourist is the strict vegetarian/vegan (50.60%), and the lacto-ovo vegetarian is placed at second place (22.07%). |

Analysis of the vegetarian tourist’s characteristics in relation to the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling.

In order to analyze the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling, a five point Likert scale, that rated 1 as nothing and 5 as high, was used. The Likert scale is the most commonly used scale in social research (Sarabia, 1999).

First, a descriptive analysis of people who responded to the following question was performed: “what priority do you assign to nutrition when you travel, according to gender, age, nationality, income level and level of education?”

Nutrition when traveling.

In order to analyze the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling, a five point Likert scale, that rated 1 as nothing and 5 as high, was used. The Likert scale is the most commonly used scale in social research (Sarabia, 1999).

First, a descriptive analysis of people who responded to the following question was performed: “what priority do you assign to nutrition when you travel, according to gender, age, nationality, income level and level of education?”

In order to examine if there are differences between the averages of the two populations, a Student’s t-test was performed. The aim was to perform a test of the hypothesis regarding the parameter of the target population. To contrast the null hypotheses, a difference between two means test (the two populations) was performed. The hypotheses that were contrasted were the H0 (equality of means) and H1 (the alternative, in other words, the means are significantly

Table no. 5: descriptive analysis (mean and standard deviation) of the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling according to gender, age, nationality, income level and level of education.

|

Mean |

Standard deviation |

||

|

Gender |

Male |

4.03 |

1.014 |

|

Female |

4.05 |

0.98 |

|

|

Age |

Young adults (up to 30 years of age) |

3.97 |

0.953 |

|

Adults (over 30 years of age) |

4.17 |

1.012 |

|

|

Nationality |

Spanish |

3.96 |

1.001 |

|

American |

4.23 |

0.925 |

|

|

Income level |

Low/ Medium-low |

3.95 |

0.994 |

|

Medium-high / high |

4.17 |

0.964 |

|

|

Education level |

Basic |

4.15 |

0.906 |

|

Upper studies |

4.02 |

1.011 |

Source: developed by authors

This test is used to observe if the test statistics fall within or outside the acceptance region. Specifically, if the significance is lower than 0.10, then the null hypothesis is rejected; thus, there are differences between the means of the two populations; if the significance is greater than 0.05, then the null hypothesis is accepted; thus, there are no significant differences between the means of the two populations (Hair et al., 2005).

Before this contrast is performed, the variance hypothesis of the two populations is equal for both groups by using a Levene’s test (Levene, 1960). If the significance of the Levene’s test is greater than 0.05, it can be concluded that there is equality between the population variances; that is to say, there is homoscedasticity. On the other hand, if the significance is greater than 0.05, then there are differences between the population variances.

The difference between two means test performed for each target population of this study (gender, age, nationality, income level and level of education) is shown below.

Table no. 6: difference between two means test (t-student) and the Levene’s test regarding the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling according to gender, age, nationality, income level and level of education.

|

Difference between means test |

Levene’s test |

|||

|

t |

Sig. |

Sig. |

||

|

Gender |

-0.15 |

0.881 |

1.14 |

0.286 |

|

Age |

-1.956 |

0.051* |

1.38 |

0.241 |

|

Nationality |

-2.498 |

0.013** |

0.0005 |

0.941 |

|

Income level |

-2.125 |

0.034** |

0.353 |

0.553 |

|

Education level |

1.082 |

0.28 |

0.011 |

0.915 |

Source: developed by authors.

According to table no. 6, there are significant differences between the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling for young adults (up to 30 years of age) and adults (older than 30 years of age) if a significance level of 10 % is taken into account. There are also significant differences between the Spanish population and foreigners with a significance level of 5 %. Finally, there are differences according to the income level, if a significance level of 5 % is taken into account. This analysis shows that older individuals assign more importance to nutrition when they travel compared to younger individuals. In other words, older travelers are more conscientious and aware of their nutrition. Foreigners also seem to be more concerned about their nutrition when they travel, which indicates that their culture is more sensitized about nutrition. Lastly, individuals who have a higher income, and therefore have a higher purchasing power, show a higher priority for their nutrition when they travel. In contrast, based on the available data, there is no empirical evidence that suggests that there is a difference when it comes to nutrition according to gender and level of education.

Image of the destination in relation to restaurants

During the last part of this study, participants were asked about their image of the destination according to their satisfaction level with restaurants. An 83.6 % of the respondents answered that in this case their image of the destination was negative and only 16.4 % maintained a positive image of the destination. Also, for those who responded positively, their priority assigned to nutrition when traveling was a 4.19 over 5 points, while those who responded negatively assigned a priority of 3.42.

Table no. 7: descriptive analysis (mean and standard deviation) of the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling according to the image of the destination if they were satisfied with the food.

|

Mean |

Standard deviation |

||

|

Image |

Negative |

4.19 |

0.912 |

|

Positive |

3.42 |

1.070 |

Source: developed by authors.

This value contrast is significantly different (t-student: 5.12; p-value: 0.000) with a significance level of 1 %.

Table no. 8: difference between two means test (t-student) and Levene’s test of the priority assigned to nutrition when traveling according to image of the destination if they were not satisfied with the food.

|

Difference between means test |

Levene’s test |

|||

|

t |

Sig |

Sig |

||

|

Image |

5.120 |

0.000*** |

6.68 |

0.010 |

Source: developed by authors.

This analysis shows that restaurants should be vigilant with the food they serve, since vegetarian tourists carefully consider it when they travel. Also, authorities must monitor and control the quality of such restaurants, because these tourists’ negative evaluations could cause a harmful opinion of the destination by affecting their loyalty, their feedback and thus, the reputation of the destination (Niininen & Riley, 1998).

If this study is carefully analyzed, it could be concluded that there is a niche inside the vegetarian touristic market that is mostly occupied by family-owned businesses. Considering that the vegetarian tourist’s profile is a foreign individual who is older than 30 years of age with a medium-high income, then these tourists are more likely to assign more importance to their nutrition and choose a restaurant according to their gastronomic offer, which significantly impacts the reputation of such destination.

Conclusions

Considering that Spain is one of the leading touristic destinations, we should advance in certain aspects to improve in the near future, case in point, the adaptation of the infrastructure of the restaurants and the changes taking place due to the new demand. The need for nutrition when traveling is an aspect that many disregard, but for a few specific tourists, especially vegetarians, it is incredibly important and may even motivate their trip.

In order to better understand the vegetarian world, this study delved into its origins, the type of vegetarians there are, how this type of diet influences health and the infrastructure of the vegetarian restaurants which are currently being dominated by family businesses.

Based on the hypotheses posed in this study, we wanted to analyze the difference between the priorities assigned to nutrition when choosing a travel destination, according to gender, age, nationality, income level, level of education, specifically within the vegetarian touristic sector.

This study concluded that both gender and level of education do not yield empirical evidence to affirm that these aspects influence the priority assigned to nutrition when these types of tourists travel.

However, the results of our study contradict those found in the literature, since, according to numerous studies such as the one performed by Alvarez (2015) “Un análisis de las personas vegetarianas en la Universidad de la laguna” (An analysis of vegetarians at the University of La Laguna) a predominantly female vegetarian profile is emphasized. Also, we found that Diaz Carmona (2012) stated in her study that women express more concern an empathy towards animals, are opposed to animal testing, have a more developed sense of disgust and are less receptive to meat consumption, associating meat to the opposite gender as a sign of masculinity and power (Orellana, Sepulveda & Denegri, 2013), which could be a causing factor for a higher implementation of vegetarianism among females than males.

However, we can state that we have indeed found empirical evidence to suggest that aspects such as age, nationality and income level influence the priority given to nutrition when these tourists travel.

Consequently, we can say that the older adults are, the greater their concern on nutrition is when they travel in comparison to younger travelers. Therefore, it can be concluded that older individuals are more aware of their nutrition when they travel than the younger ones.

Likewise, we can affirm that foreigners are more concerned with their nutrition when they travel than Spaniards. This shows their level of awareness about nutrition when they travel and could be due to cultural aspects within their country.

Finally, higher income individuals, thus, those with a higher purchasing power place more importance on their nutrition when they travel than those with a lower income level.

Therefore, creating a profile of our vegetarian tourist and summarizing the findings, we can say that both gender and level of education do not affect the priority that these tourists assign to their nutrition when they travel. However, age, nationality and income level do affect the prioritization that these tourists give nutrition when they travel.

Continuing the line of this study and trying to identify other aspects that could provide information about the destination and nutrition of this type of tourists, the last part of this study to examine the image of the destination if food is satisfactory.

Our analysis concluded that restaurants must be vigilant with their food, because vegetarian tourists carefully bear it in mind when they travel.

Therefore, this information is very valuable, not just for the vegetarian restaurants which are mostly family-owned, but also for the satisfaction level of the touristic destinations. As a matter of fact, if we analyze the literature, it can be found that a place will be more attractive for a gastronomic tourist, depending on the existing relationship between the cuisine and the culture rooted in the place (Riley, 2005), with several factors that motivate a gastronomic tourist to select one place over another.

Also, authorities must monitor and control the quality of such restaurants because if these tourists’ evaluations are negative, they could create a negative image of the destination and, as a consequence, may affect other aspects such as their loyalty, feedback and reputation of the destination (Niininen & Riley, 1998).

The results show that there is a market niche inside the vegetarian touristic sector that is mostly occupied by family-owned businesses. Additionally, if the vegetarian tourist’s profile is a foreign adult over 30 years of age with a medium-high income level, it is likely that they place more importance to their nutrition and choose a restaurant depending on their gastronomic offer, significantly impacting the reputation of such destination.

Limitations and future lines of research

As far as the limitations of our research, we can firstly highlight the amount of analyzed aspects and characteristics regarding the vegetarian tourist, which aimed to obtain a more exact pattern in these types of segments.

Another limitation of our study was that it focused only on nutrition as a determining factor when choosing a destination, because there could be other determining factors when planning their trips. These could yield more complete information about the decisions of this type of tourists.

Regarding future lines of research, other studies could hand out a higher number of surveys in order to generate a greater sampling and increase the representativeness of the study and improve the conclusions.

Since this is a growing sector and, most of all, a current market trend, future studies could focus on better defining the vegetarian tourist, their characteristics and behaviors with the objective of offering more information to restaurants and generate an offer that is more adapted to the needs of the market.

Other future lines of research should focus on performing studies regarding the link between restaurants and the satisfaction of the destination, since, as previously shown, more information regarding this aspect is needed; it could help the loyalty, recommendation and reputation of the destination.

To conclude, we believe that this topic is truly suggestive and significant in order to continue with such line of research, since inside the international touristic sector, it is a trend especially due to the constant and growing changes.

Álvarez, R. D. (٢٠١٥). Un análisis de las personas vegetarianas. Tenerife. España. Universidad de la Laguna.

Andreu, L., Bigné, J. E., y Cooper, C. (2000). Projected and perceived image of Spain as a tourist destination for British travelers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 9(4), 47-67.

Beerli, P.A., y Martin, J.D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image, in: Annals of tourism research, 31 (3), 657-681.

Brignardello, J., Heredia, L., Paz Ocharán, M., y Durán, S. (2013). Conocimientos alimentarios de vegetarianos y veganos chilenos. Revista chilena de nutrición, 40 (2), 129-134.

Camargo, L. M. (2017). Flexitarianos: vegetarianos flexibles inspiran la innovación alimentaria. Revista de tecnología e higiene de los alimentos, 1(480), 34-39.

Cayllante Cayllagua, J. P. (2014). Vegetarianismo. Revista de Actualización Clínica Investiga, 2(42), 2195.

Díaz Carmona, E. M. (2012). Perfil Del Vegano Activista De Protección Animal En España. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 2(139), 175-187.

Díaz, E. (2014). Veganismo y Defensa Animal en España: relaciones complejas entre los animales y heterogeneidad dentro del movimiento. (Tesis doctoral). Universidad Pontifica Comillas – ICADE. Madrid.

ENIDE (2011). Encuesta Nacional de Ingesta Dietética 2009-2010 .Evaluación nutricional de la dieta española. Agencia española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición.

Eymann, A., y Ronning, G. (1997). Microeconometric models of tourists’ destination choice. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 27(6), 735-761.

Federación Española de hostelería - FEHR (2016). Estudio Anual 2016/2017. Los sectores de la Hostelería. Recuperado de: www.fehr.es/documentos/publicaciones/descargas/des-102.pdf

Fields, K. (2002). Demand for the gastronomy tourism product: motivational factors. Tourism and gastronomy, 4 (2), 36-50.

González, A. (2012). 101 secretos para una vida sana. Buenos Aires. Argentina. Asociación Casa Editora Sudamericana.

Haas, L. (2017). Básicos para un estilo de vida vegano: Cómo vivir sin carne y sin productos lácteos. London. England. One Jacked Monkey, LLC

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., y Tatham, R. (2005). Multivariate Data Analysis. New Jersey. Prentice Hall.

Jakub, M. (2016). Map of ‘vegetarian friendliness’ (number of vegetarian restaurants) in Europe by country. [Mensaje en un blog]. Recuperado de: https://jakubmarian.com/map-of-vegetarian-friendliness-number-of-vegetarian-restaurants-in-europe-by-country/

Kotler, P., Haider, D.H., Y Rein, Y. (1993). Marketing places: attracting investment, industry and tourism to cities, states and nations. New York. The free Press.

Lansberg (1994) citado por Gersick, K.E. En Handbook of Family Business Research, 1969-1994. Boston: Mass, Jossey-Bass Publisher, Summer.

Lawson, F. Y., Baud- Body, M. (1977). Tourism and recreational development. London: Architectural Press.

Levene, H. (1960). Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling. Editors: “Ingram Olkin, Harold Hotelling, et alia. Stanford University Press, 278-292.

Lilien G, Kotler P y Moorthy K.S (1992). Marketing Models, Nueva Jersey. Prentice Hall.

López-Guzmán, T., y Sanchez Cañizares, S. M. (2012). La gastronomía como motivación para viajar. Un estudio sobre el turismo culinario en Córdoba. PASOS. Revista de turismo y patrimonio cultural,10 (5), 575 - 848

Malhotra, N. K. (2004). Diseño de la investigación. Investigación de Mercados. Naucalpan de Juarez. México. Pearson educación.

Miller, D. y Le-breton, I. (2005). Managing for the Long Run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Cambridge: Mass. Harvard Business SchoolPress

Millet, O. F. (2010). La imagen de un destino turístico como herramienta de marketing. Málaga. España. Universidad de Málaga.

Morley, C.L (1994). Experimental Destination Choice Anaylsis”, Annals of tourism Research, 21(4) 780-791.

Molinero, R. (2016). Así queda el mapa con las ciudades más y menos vegetarianas del mundo. Playground [Mensaje en un blog]. Recuperado de: www.playgroundmag.net/food/queda-mapa-ciudades-vegetarianas-mundo_0_1841815814.html

Determinación del perfil del consumidor de los restaurantes vegetarianos en la ciudad de Chiclayo (Tesis de pregrado) Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo, Chiclayo, Perú. Recuperado de:http://tesis.usat.edu.pe/bitstream/usat/91/1/TL_Montalvo_Moreno_Luviana.pdf

Morley, C.L (1994). Experimental Destination Choice Anaylsis”, Annals of tourism Research, 21(4) 780-791.

Nelson, J., Moxness, K., Jensen, M. y Gastineau, C. (1996). Dietética y Nutrición. Manual de la Clínica Mayo. Madrid. España. Harcourt Brace.

Niinimen, O. y Riley, M. (1998). Repeat Tourism. Paper presentado en The Australia and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference. Universidad de Otago, Nueva Zelanda.

Oliveira, S. (2011). La gastronomía como atractivo turístico primario de un destino. El turismo gastronómico en Mealhada. Portugal. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, nº 20, 738-752.

Orellana, L. M., Sepúlveda, J. A., y Denegri, M. (2013). Significado psicológico de comer carne, vegetarianismo y alimentación saludable en estudiantes universitarios a partir de redes semánticas naturales. Revista mexicana de trastornos alimentarios, 4(1), 15-22.

Quan, S. y Wang, N. (2004). Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: an illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tourism Management, 3(25), 297-305.

Riley, M. (2005). Food and beverage management: A review of change. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management,17(1), 88-93.

Sarabia, J.F. (1999). Construcción de escalas de medida. Metodología para la Investigación en Marketing y Dirección de Empresas. Madrid. España Pirámide editorial.

Saz-Peiró, P., Del Ruste, M. M., y Saz-Tejero, S. (2013). La dieta vegetariana y su aplicación terapéutica. Medicina Naturista, 7(1), 15-29.

SEAIC (2016). Informe sobre alergología. Sociedad Española de Alergología e Inmunología Clínica. Madrid. España.

Tikkanen, I. (2007). Maslow’s hierarchy and food tourism in Finland: five cases. British food journal, 109(9), 721-734.

Torres Bernier, E. (2003). Del turista que se alimenta al turista que busca comida. Gastronomía y Turismo. Cultura al Plato. Lacanau, G. y Norrild, J.(coordinadoras). CIET, Buenos Aires, 305-316.

Veguillas, E. (2017) The Green Revolution, entendiendo la revolución veggie [Mensaje en Blog] Latern Blog. Recuperado de: www.lantern.es/2017/02/the-green-revolution-entendiendo-la-revolucion-veggie/

Wright, P., Ferris, S.P., Sarin, A., y Awasthi, V. (1996). Impact of corporate insider, blockholder, and institutional equity ownership on firm risk taking, Academy Management Journal, 2(39), 441-463.