|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Family businesses and sustainable tourism, a valuation of multi-stakeholders in Nanacamilpa of Mariano Arista, Tlaxcala. Case study: Sanctuary of the fireflies

Marco Antonio Lara de la Calleja a, Gerardo Zanella-Palaciosb

aDoctorado Planeación Estratégica y Dirección de Tecnología, Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, 17 Sur 901, Barrio de Santiago, C.P. 72410 Puebla, Mexico

b Doctorado Planeación Estratégica y Dirección de Tecnología, Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla, 17 Sur 901, Barrio de Santiago, C.P. 72410 Puebla, Mexico. Economics and Business Administration Phd. Programme at University of Málaga, Spain

Received 26 January 2017; accepted 29 June 2017

Available online 30 june 2018

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M14; M21; Q57

KEYWORDS

Family business, sustainable tourism, multi-stakeholders.

Abstract The objective of the present article is to evaluate the perspective of sustainable tourism in family business through a perspective of multi-stakeholders in the Sanctuary of fireflies of Nanacamilpa of Mariano Arista, Tlaxcala. An assessment was made of the different actors (family businesses, local authorities, civil society) in 4 areas: Environmental and resource management; Economic wellness; Socio-cultural well-being; Public policies and training, to assess the sustainability of the Sanctuary. With the methodology of analysis and evaluation developed, it was found that the family companies present a medium performance of sustainable tourism in the areas of Environmental and resource management, as well as in Public Policies and training. The results are expected to include sustainable tourism in the sanctuary of fireflies, through the participation and integration of stakeholders, to impact the dimensions of sustainability.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M14;M21;Q57

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresas familiares, turismo sustentable, multi-stakeholders

Empresas familiares y el turismo sustentable, una valoración de multi-stakeholders en Nanacamilpa de Mariano Arista, Tlaxcala. Estudio de caso: Santuario de las luciérnagas

Resumen El objetivo del presente artículo es evaluar la perspectiva de turismo sustentable en empresas familiares a través de una perspectiva de multistakeholders en el Santuario de luciérnagas de Nanacamilpa de Mariano Arista, Tlaxcala. Se obtuvo una valoración de los diferentes actores (empresas familiares, autoridades locales, sociedad civil) en 4 áreas: Gestión ambiental y de recursos; Bienestar económico; Bienestar socio-cultural; Políticas públicas y capacitación, para evaluar así la sustentabilidad del Santuario. Con la metodología de análisis y evaluación desarrollada se encontró que las empresas familiares presentan un medio desempeño de turismo sustentable en las áreas de Gestión ambiental y de recursos, asi como en Políticas Públicas y capacitación. Con los resultados se espera la inclusión de un turismo sustentable en el santuario de las luciérnagas, mediante la participación e integración de los stakeholders, para impactar en las dimensiones de la sustentabilidad.

Introduction

Tourism is considered as a tool to achieve economic development and the sustainability of the environment. According to Kimmel, Perlstein, Mortimer, Zhou, and Robertson (2015) in 2014, more than one billion tourists traveled internationally, an increase of 4.4% over the previous year, marking an impressive growth rate taking into account the challenges facing the global economy as a whole (United Nations World Tourism Organization 2015). Tourism represents up to 9% of world GDP and one out of every 12 jobs worldwide (UNWTO, 2013). The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development recognized the importance of tourism in its final document: “We emphasize that well-designed and managed tourism can make a significant contribution to the three dimensions of sustainable development, has strong links with other sectors, can create decent jobs and generate business opportunities. We recognize the need to support sustainable tourism activities and the creation of relevant capacities that promote environmental awareness, conservation and protection of the environment, respect for fauna, flora, biodiversity, ecosystems and cultural diversity; improve the well-being and livelihoods of local communities by supporting their local economies, the human and natural environment as a whole” (United Nations, 2012).

According to the World Tourism Organization (1993), sustainable tourism is one that meets the current needs of tourists, protecting the sites that receive them, thus safeguarding the opportunities for the future to take advantage of those destinations. That is, sustainable tourism results in the integration of a model of economic development that not only guarantees an improvement in the quality of life of the communities where it is carried out, but a sustained conservation of the environment and culture by both the host community and tourists.

Getz and Carlsen (2005) point out that tourism offers many opportunities to family businesses, being able to be vital for the experiences and the satisfaction of the clients, and for the destiny or the community development. The tourism and hospitality industry is dominated by small and family businesses, many of which are initiated or bought by entrepreneurs who are interested in self-employment as a way of life and not only for economic reasons (Getz and Petersen, 2004; Blichfefdt, 2009).

Dreher and Tomio (2004), in a study carried out with family companies of tourist services of Blumenau, observed that most companies do not have professional management, are reactive to market changes and centralize decisions and functions by imposing internal barriers to innovation and competitiveness.Atejevic (2009), revealed that decisions in small tourist businesses are made by one or two people who tend to respond to sudden market opportunities. The authors observed the lack of professionalization of the management, thus running a strong risk for its permanence and development. In addition, rural and peripheral areas are especially influenced by the results of family businesses, which is why research aimed at these configurations should be a priority (Morrison, Carlsen and Weber 2010). Therefore, the present article promotes the participation of diverse actors in the valuation of sustainable tourism, taking into account the point of view of the social sector, business, and government authorities, to generate projects that are beneficial for the region.

García and Makinen (2013) mention that the procedures for evaluating sustainable tourism practices should reflect the complex and dynamic nature of sustainability and tourism, which implies a network of relationships and interactions between multiple stakeholders each with a unique set of specialized knowledge with diverse and divergent points of view (Fennell, 2006; Jamal and Stronza, 2009; Saarinen, 2006). The challenge of the evaluation process then adds the subjective and dynamic meaning of sustainability, which varies between different interest groups.

As a result, the assessment of sustainability in the context of tourism can not only be seen as the implementation of strategies from higher to lower levels, but of the active involvement of the multiple stakeholders around the evaluation, that allows tourism organizations to participate in close collaboration with stakeholders for the sustainability of their day-to-day practices. The latter helps tourism organizations not only to deal constructively with their differences, but also to contribute to the sustainability of their own destinies by defining the sustainability objectives that are in harmony with the interests and perceptions of the various stakeholders (Smith and Duffy, 2003).

The objective of this article is to evaluate the perspective of sustainable tourism in family business through a perspective of multistakeholders in Nanacamilpa of Mariano Arista, Tlaxcala. Case Study: Firefly Sanctuary.

The Sanctuary of the Fireflies in Nanacamilpa of Mariano Arista, Tlaxcala, is a natural attraction that offers to the tourists who visit it the sighting of the fireflies in their period of reproduction, which is recorded on trails in the middle of the forest, mainly when there is a humid climate, with the presence of some light rain, occurs around 20:30 and 21:15 hours, the fireflies are very accurate and the phenomenon is observed for 45 or 50 minutes, although it has been seen that sometimes it gets repeated around one in the morning. It is important to mention that Nanacamilpa and the North Island of New Zealand are the only two sanctuaries in the world where fireflies reproduce in these quantities (Ramírez, 2014). In the Sanctuary of the fireflies of Nanacamilpa there is a tourism of environmental exploitation, causing biological, socio-cultural and economic impacts in the territory, it needs to be studied because to date there is no information to measure the carrying capacity, care and preservation of the environment, as well as sustained economic growth and equity in social participation, which eventually and in the medium term can lead to irreversible damage to the tourist attraction.

In order for people to visit the Sanctuary of fireflies in Nanacamilpa, the municipality currently offers its regional visitors, national and foreign, a shelter that has cabins, campsites, sports courts, children’s games, guided hikes, abseiling, a small dam ideal for fishing and boat rides, horseback riding and practice area for mountain sports. The destination incursion in the tourism “Nature” described by Blanco (2012) as nature tourism, which generates an important economic spill that translates into the contribution of 0.037% to the national GDP (Canseco, 2015), resulting in a moderately representative amount compared to the 3.8% represented by the tourism sector in general for the national GDP in 2015 (INEGI, 2015).

According to a study carried out in 2012 by the Department of Zoology of the Institute of Biology of the UNAM, Nanacamilpa is home to fireflies belonging to the genus Macrolampispalaciosi. This species does not coincide with any of the known species, therefore, it is considered an endemic species of the municipality. The firefly habitat sits in the oak forest of Nanacamilpa, and through the Environmental Services Program, the conservation and protection of the richness of its biodiversity is promoted (ComisiónNacionalForestal, CONAFOR 2013).

Theoretical framework

The company and its environment

Traditionally the company was born as an organization whose function was the accumulation of capital and attempts at social improvement were not considered, since the only interests contemplated were those of the shareholders. In the context of the industrial revolution, the capitalist entrepreneur reinvested most of the surplus generated and carried out his social function, from his pursuit of economic gain. It was not until the level of accumulation was enough, that the owners of the companies joined the philanthropic work. Thus, at the end of the 19th century, a business philosophy was developed, which recognized that the company was based in a certain community and therefore was due to it (Carnegie, 1889).

On the other hand, the economy and the existing industrial conditions demand an increase in the different forms of interaction between the companies and their stakeholders in order to subsist. Issues such as ecological sustainability, transparency and accounting, human rights and labor relations, and corruption are some of the issues faced by global companies on a daily basis.

In addition, specifically for primary stakeholders such as owners, employees, customers and suppliers, an issue of interest is the interaction and action by business leaders on these specific issues. It is also important to consider that thanks to the advance of technology in communication, the internet is today information and organization tool that can help the dissemination of professional practices or have a negative effect if the company does not perform ethically since the information about their business practices can be used against them.

In regard to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), also called Corporate Social Responsibility, is now a trend and a global corporate strategy that is increasingly taking shape within the business sphere, in which each country has developed and adapted the issue in its own way and has imprinted its own cultural nuances. Stakeholder theory asserts that company managers should not only satisfy shareholders but a wide variety of groups that can affect or be affected by the results of the company and without which it would cease to exist (Argandoña, 1998 , Donaldson and Preston, 1995, Freeman and Reed, 1983, Maignan and Ferrell, 2004). The view of this theory has been considered primarily as strategic, since it believes that CSR is capable of increasing the competitive advantage of companies.

Sustainable companies

Organizational sustainability is the link between the physical environment and activities and economic policies, which could be achieved through the adequate performance of companies (Simon, 1989), according to what has been considered as the main dimensions of organizational sustainability (the Triple Baseline), which are social, environmental and economic factors (Hernani and Hamman, 2013). Such conceptualization is fully qualified to incorporate what is necessary to evaluate the impacts of these three dimensions, adopting a popular and common phrase in the business environment: “People, Planet and Utilities” (Hill and Seabrook, 2013), providing the reflection where a company being sustainable protects its personnel, its property and its environment, because that will provide the necessary resources for its performance.

On the other hand, sustainable development has the capacity to develop technologies and products that provide solutions to environmental and social challenges. It can help create new businesses, new markets, new livelihoods and foster economic development. (Instituto de la Empresa Familiar 2011).

Sustainable tourism

Tourism is considered as a significant element for the economic, social, cultural and even environmental development of a specific country or region (Serrano et al., 2010)Tourism that incorporates the community recognizes the importance of the individual by improving their conditions of life. The type of offer revolves around the resources natural resources in the area, and services are community to impact on their economic well-being and Social (Sanchez and Vargas, 2015).

Methodology

For the development of the research we considered the perspective of “Multi-stakeholder thinking” that is a representation of three or more interest groups and their points of view on the processes that encompass their dynamic. This perspective offers in the sustainable tourism, the visualization of multiple perspectives and experiences, which allow to construct knowledge and to develop capacities to reach social and environmental objectives (Hemmati, 2002). In the evaluation of sustainability, the “Multi-stakeholder thinking” minimizes the inconvenience of the simple consideration of one of the interested parties and shows the benefits of a greater inclusion in the evaluation process (Jamal, Stein, y Harper, 2002). In the study of the sanctuary of the fireflies identified the main interest groups, in which sustainable tourism impacts: the public sector, the private sector through family businesses and civil society.

Therefore, using non-probabilistic snowball sampling, people belonging to each stakeholder group were chosen to evaluate their views on sustainability practices at the Firefly Sanctuary, finding practices that need greater attention from policy-makers and sustainable tourism planners. Primary data were obtained through personal interviews by means of questionnaires and field observation. The instrument was evaluated by means of a pilot test applied to a representative of each sector, to verify the clarity of the questions.

To obtain information from the public sector, there were 2 questionnaires applied to personnel of the City Council of the Municipality of Nanacamilpa, with activities related to tourism; of the Private sector, the same number of questionnaires were applied to 2 family companies that provide services in the area of the Sanctuary; in the civil society sector was the same number of questionnaires to maintain the proportion in the data, seeking that the participants of the society had a rooting and leadership in the zone.

The design of the questionnaires was based on the principles and indicators of sustainable tourism development and its impacts on the local environment, adapted from Lei Tin and Rusell (2014), Bui (2000), Choi and Sirakaya (2006), the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (2005). The questions assess the socio-economic, cultural and environmental impact of sustainability practices, in areas of: Environmental and resource management; Economic well-being, Socio-cultural well-being; Public Policies and Training, rating their opinion on a five-point Likert scale (1-strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree). Below are the different areas evaluated, within the framework of “triple-bottom-line” as well as planning and development.

|

Table 1Evaluation in environmental and resource management |

|

Environmental and resourcemanagement |

|

Our operation has been successfully implemented: |

|

EnergySavingMethods |

|

Watersavingmethods |

|

ReforestationPractices |

|

Reduction of garbage in the forest |

|

Practices to protect the species of fireflies |

|

Practices to reduce soil erosion |

|

Actions to encourage reproduction of the species of firefly |

|

Tourism has significantly helped to improve the protection of the environment in the firefly sanctuary |

|

Source: Authors |

|

Table 2 Evaluation in Economic wellness |

|

Economic wellness |

|

Tourism promotes local businesses related to tourism |

|

Tourism promotes other local sectors of the economy (agriculture, food processing, services, etc.) |

|

Most local employees are doing poorly paid jobs |

|

A significant portion of the local population earns income from jobs related to tourism |

|

Tourism creates many jobs, as well as hotels and restaurants |

|

Many food and beverage vendors are from outside this area |

|

Source: Authors |

|

Table 3 Evaluation in Socio-cultural wellness |

|

Socio-cultural wellness |

|

Tourism in this area increases: |

|

Number of poorpeople |

|

Gap between the poor and the rich |

|

Opportunitiesforwomen |

|

EducationOpportunity |

|

Local arts and craft production |

|

Historical and cultural conservation |

|

Theincidence of delinquency |

|

Congestion (in terms of traffic) |

|

Negative impacts on local values of culture and tradition |

|

Effort in the preservation of traditional festivals, social values and cultural diversity |

|

Source: Authors |

|

Table 4 Evaluation in Public policies and training |

|

Publicpolicies and training |

|

The government has clear regulations / guidelines on the protection of the environment |

|

We do not know much about tourism plans in the region |

|

Consultation with various local agencies for tourism planning |

|

We have been involved in tourism planning in the region |

|

The participation of society is not significant in the development of tourism |

|

Local people do not know so much about the development of tourism |

|

Regional development plans for tourism are not published |

|

The participation of society is not effective |

|

We have programs / information to educate visitors on sustainable development |

|

There are programs / information to educate local society on sustainable development |

|

We have training programs in sustainable development for our employees (for the private sector) |

|

Source: Authors |

This research, in addition to considering the “Multi-stakeholder thinking” perspective, adds in a coordinated and consistent way the impacts in the economic, social and environmental levels, not only in its productive activities, but also in defining their policies and actions to achieve sustainable tourism with the participation of family businesses; the description of strategies and the architecture to be designed, respond to the need to generate and deliver satisfactorily a service, without harming the environment. Subsequently the evaluation was obtained through the questionnaire applied to 2 representatives of each sector: Family businesses, local authorities and civil society.

With these amounts, the averages for each sector were calculated for each of the areas, to have a comparison between different stakeholders. Likewise, the scores with higher and lower results are analyzed, to support the possible actions and improvement programs to be carried out.

Results

The following tables 5-8 correspond to the results of the corresponding study areas.

|

Table 5 Results environmental and resource management |

|||||||

|

Environmental and resource management |

Private sector |

Public sector |

NGO-Society |

||||

|

Environmental and resourcemanagement |

|||||||

|

EnergySavingMethods |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

13 |

|

Watersavingmethods |

4 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

16 |

|

ReforestationPractices |

3 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

16 |

|

Reduction of garbage in the forest |

4 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

19 |

|

Practices to protect the species of fireflies |

2 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

|

Practices to reduce soil erosion |

2 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

|

Actions to encourage reproduction of the species of firefly |

2 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

|

Tourism has significantly helped to improve the protection of the environment in the firefly sanctuary. |

2 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

|

21 |

16 |

33 |

13 |

9 |

16 |

||

|

2.625 |

2 |

4.125 |

1.625 |

1.125 |

2.5 |

||

|

2.3 |

2.8 |

1.5 |

|||||

|

In disagreement |

Indifferent |

In disagreement |

|||||

|

Source: Authors |

|||||||

|

Table6ResultsEconomicwellness |

|||||||

|

Economicwellness |

Private sector |

Public sector |

NGO-Society |

||||

|

Tourism promotes local businesses related to tourism |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

19 |

|

Tourism promotes other local sectors of the economy (agriculture, food processing, services, etc.) |

3 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

20 |

|

Most local employees are doing poorly paid jobs |

3 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

22 |

|

A significant portion of the local population earns income from jobs related to tourism |

4 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

21 |

|

Tourism creates many jobs, as well as hotels and restaurants |

4 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

19 |

|

Many food and beverage vendors are from outside this area |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

23 |

|

21 |

21 |

19 |

15 |

27 |

21 |

||

|

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.166 |

2.5 |

4.5 |

23.5 |

||

|

3.5 |

2.83 |

4 |

|||||

|

In disagreement |

Indifferent |

In disagreement |

|||||

|

Source: Authors |

|||||||

|

Table 7 Results Cultural wellness |

|||||||

|

Socio-cultural wellness |

Private sector |

Public sector |

NGO-Society |

||||

|

Tourism in this area increases: |

|||||||

|

Number of poorpeople |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

16 |

|

Gap between the poor and the rich |

3 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

19 |

|

Opportunitiesforwomen |

3 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

21 |

|

EducationOpportunity |

3 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

14 |

|

Local arts and craft production |

4 |

4 |

5 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

23 |

|

Historical and cultural conservation |

3 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

17 |

|

Theincidence of delinquency |

4 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

20 |

|

Congestion (in terms of traffic) |

4 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

26 |

|

Negative impacts on local values of culture and tradition |

3 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

19 |

|

Effort in the preservation of traditional festivals, social values and cultural diversity |

3 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

19 |

|

33 |

36 |

38 |

18 |

36 |

33 |

||

|

3.3 |

3.6 |

3.8 |

1.8 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

||

|

3.45 |

2.8 |

4.5 |

|||||

|

In disagreement |

Indifferent |

In disagreement |

|||||

|

Source: Authors |

|||||||

|

Table 8 Results Public policies and training |

|||||||

|

Publicpolicies and training |

Private sector |

Public sector |

NGO-Society |

||||

|

The government has clear regulations / guidelines on the protection of the environment |

2 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

|

We do not know much about tourism plans in the region |

2 |

5 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

23 |

|

Consultation with various local agencies for tourism planning |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

|

We have been involved in tourism planning in the region |

2 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

|

The participation of society is not significant in the development of tourism |

3 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

|

Local people do not know so much about the development of tourism |

3 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

|

Regional development plans for tourism are not published |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

19 |

|

The participation of society is not effective |

3 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

15 |

|

We have programs / information to educate visitors on sustainable development |

4 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

|

There are programs / information to educate local society on sustainable development |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

|

We have training programs in sustainable development for our employees (for the private sector) |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

30 |

28 |

15 |

28 |

18 |

20 |

||

|

2.72 |

2.5 |

1.5 |

2.8 |

1.8 |

2 |

||

|

2.63 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

|||||

|

In disagreement |

Indifferent |

In disagreement |

|||||

|

Source: Authors |

|||||||

According to the Likert scale established for each of the elements, the averages obtained from the actors evaluated show that the closeness with the value 5, very much agree, rests on a high performance of sustainable tourism, on the contrary a closeness with the value 1, stronglydisagree, values a low performance in the sustainability of tourism in the area. Finding the Following:

Source: Authors

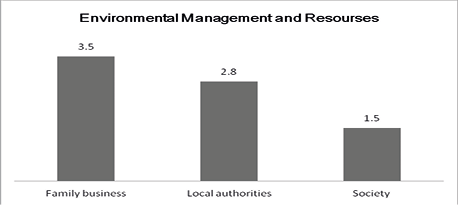

Figure 1 Environmental management and resourses

It was found that the perception of family businesses and society lies in the lack of actions in environmental and resource management, the perspective of local government authorities denotes an average with better results,mentioning that they have already carried out some of the activities aimed at protecting the environment. Therefore, there is concordance in two actors: the perspective of family businessand society, given the perception of a low performance of sustainable tourism in the Sanctuary.

On the other hand, the evaluated stakeholders consider that the actions that have been implemented the most are those related to the reduction of garbage in the forest,methods of saving water and reforestation practices and the lowest qualification obtained are actions to encourage the reproduction of the species of firefly.

Source: Authors

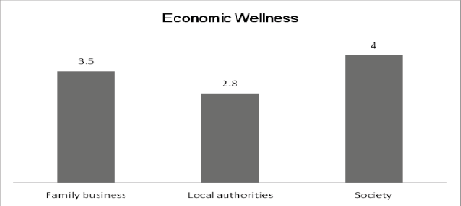

Figure 2 Economic wellness

The valuation of the family and society companies, mention that actions are actually being carried out that improve the economic situation in the area, through the promotion of sources of employment, however, it is the local government’s own perception that it finds itself indifferent to the challenges of promoting the economic wellness of the area and consequently the sanctuary of fireflies.

Likewise, the different actors evaluated agree that many of the food and beverage vendors are from outside the study area and only come during the firefly season, affecting the economy of the family businesses that originate in the study area; also report that most local employees are doing poorly paid jobs.

Source: Authors

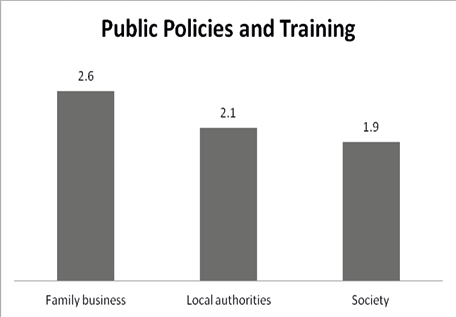

Figure 3 Public policies and training

The three sectors agree that not much is known about tourism plans in the region and that these plans are not published. It is important to highlight that priority areas that are not being considered are identified, such as the lack of participation of local agents in the planning of tourism, the lack of clear regulations and guidelines on the protection of the environment and the need to promote programs to inform and educate local society in sustainable development.

Discussion

According to the obtaining of the averages in each one of the sections can be developed an index of the obtained results where from 0 to 1.6 it is a low performance of the sustainable tourism, of 1.7 to 3.3 is an average performance of the sustainable tourism and of 3.4 to 5 is a high performance. The perceptions of the 2 family companies dedicated to the provision of tourist services, lodging, food and tours in the study area, show that in environmental and resource management with a 2.3 they present an average performance of sustainable tourism activities; in the section of Economic wellness with a 3.5 they present a high performance of the activities of sustainable tourism; in Socio-cultural wellness with a 3.4 show a high sustainability performance in tourism; in Public policies and training with a 2.6 average performance of sustainable tourism. It should be noted that the scores that place family businesses on high performance, are very close to the average valuation,

reason why it is necessary to continue and to assure the execution of activities to maintain and to increase its qualification. It is in the activities of Environmental Management and Public Policy, where it is evident to implement improvement actions, from actions to reduce the environmental impact of family businesses in the area, to the formulation of local government programs, to protect and improve sustainable tourism for family businesses.

Conclusion

The evaluation shows that it is necessary to understand the fundamentals of sustainability, the statutes that govern the care of flora and fauna and all the general principles that are part of tourism, public and private sectors and NGOs, based on the three dimensions of sustainability: social, economic and environmental.

It was found that in Nanacamilpa of Mariano Arista, stakeholders have weaknesses around sustainability, therefore it is not necessarily sustainable tourism, since the actions carried out demonstrate that priority is given to the economic aspect above the social and environmental, and although there are actions to improve the environment, the participation of stakeholders in this regard is still very low.

The proposed strategies refer to the conservation and use of the site, through an adequate application of sustainability, that is, to consider the same size, social, economic and environmental. By incorporating sustainable tourism, it is possible to unify in a structured and proportional way all the activities and to improve the methods and techniques that somehow were being carried out, but in an isolated way.

With the above mentioned, the present research opens the possibility for the accomplishment of later studies that can deepen in the measurements of the evaluations and proposed strategies of the present study.

Argandoña, Antonio. (1998).The Stakeholder Theory and the Common Good, journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 17, N. 9, pp. 1093-1102.

Atejevic, J. (2009)Tourism entrepreneurship and regional development: example from New Zealand. International Journal of EntrepreneurialBehavior&Research 15(3): 282-308

Boletín UNAM. (2014).Descubre universitario nuevo género de luciérnagas. Boletín, UNAM, Departamento de Zoología del Instituto de Biología.

Blanco, R.. (2012).EL TURISMO DE NATURALEZA. Estudios Turísticos, 2, 169. (38). España: Licenciarte.

Bui, T.T. (2000).Tourism dynamics and sustainable tourism development – principles and implications in Southeast Asia (Unpublished doctorate dissertation). NanyangTechnologicalUniversity, Singapore.

Carnegie, Andrew. (1889)The North American Review, Vol. 148, N° 391, pp. 653-664, Cedar Falls

Castañeda, J. (2015).Foro Ambiental. Obtenido de foroambiental.com.mx: http://www.foroambiental.com.mx/descubren-en-mexico-nueva-especie-de-luciernaga/

Canseco, A. (2015). Proyectos integrales con enfoque “Natura” en México. REDALyC, 19.

Chan, E.S.W., & Wong, S.C.K. (2006).Motivations for ISO 14001 in the hotel industry. Tourism Management, 27(3), 481–492.

Choi, H.C., &Sirakaya, E. (2006). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1274–1289.

Collins, A. (1998).Tourism development and natural capital. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 98–109.

CONAFOR. (2013). El bosque de oyamel de Nanacamilpa, hábitat de las luciérnagas. SEMARNAT, Gerencia Estatal Tlaxcala, Tlaxcala.

Conferencia de naciones unidas (2012).El futuro que queremos. Rio de Janeiro. Banki-moon

Donaldson, Thomas y Preston, Lee. (1995).The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, N. 1, pp. 65-91

Dreher, M. T.&Tomio, D. (2004). Gestão de empresas familiares no turismo: a realidade de Blumenau, SC. Revista Eletrônica de Ciência Administrativa (RECADM) 3(2), http://revistas.facecla.com.br/index.php/recadm/ Acesso octubre ٢٠١٧

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., Spurr, R., &Hoque, S. (2010). Estimating the carbon footprint of Australian tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 355–376.

Fennell, D.A. (2006). Tourism ethics. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

Freeman, R. Edward, y Reed, David. L. (1983).”Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance”, California Management Review, Vol. 25, N. 3, p. 88

García, C., Makinen, J. (2013). An integrative framework for sustainability evaluation in tourism: applying the framework to tourism product development in Finnish Lapland. Journal of SustainableTourism, Vol. 21, No. 3, 396–416.

Getz D., and Carlsen, J. (2005).Family business in tourism. State of the art. Annals of tourism research, 32(1),237-258.

Getz, D. & Petersen, T. (2004) “Identifying industry-specific barriers to inheritance in small family businesses.” Family Business Review 7(3): 259-276

Green, H., Hunter, C., & Moore, B. (1990). Assessing the environmental impact of tourism development use of the Delphi technique. Tourism Management, 11, 111–120.

Hemmati, M. (2002). Multi-stakeholder processes for governance and sustainability: Beyond dead-lock and conflict. London: Earthscan.

Hernández, R. Fernández, C & Baptista, P. (2014). Metodología de la Investigación. McGraw Hill. 6º Edición.

Hernani Merino, M. N. y HamannPastorino, A. (2013). Percepción sobre el Desarrollo Sostenible de las MyPE en Perú. Revista de Administración de Empresas, 53(3): 290-302.

Hill, D. y Seabrook, K. (2013).Safety and Sustainability: Understanding the Business Value. Professional Safety: 81-92

Hughes, G. (2002). Environmental indicators. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(2), 457–477

INEGI. (2010). Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Tlaxcala.

INEGI. (2015). Indicadores Trimestrales de la Actividad Turística (ITAT). Obtenido de: http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/cn/itat/default.aspx

Instituto de la Empresa Familiar (2011) Innovando para el desarrollo sustentable. Catedra de la empresa familiar y servicios de estudios IEF España

Jamal, T., &Stronza, A. (2009). Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stake-holders, structuring and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(2), 169–189.

Jamal, T.B., Stein, S.M., y Harper, T.L. (2002). Beyond labels: Pragmatic planning in multi- stakeholder tourism-environmental conflicts. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 22(2), 164–177.

Johnson, D. (2002). Environmentally sustainable cruise tourism: A reality check. Marine Policy, 26, 261–270.

Johnston, C. (2014). Towards a theory of sustainability, sustainable development and sustainable tourism: Beijing’s hutongneighbourhoods and sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2014 Vol. 22, No. 2, 195–213.

Kimmel, C., Perlstein, A., Mortimer, M., Zhou, D., Robertson, D. (2015). Sustainability of Tourism as Development Strategy for Cultural-Landscapes in China: Case study of Ping’an Village. Journal of Rural and Community Development 10, 121-135

Kostić, M &Jovanović-Tončev (2014).Importance of sustainable tourism. SINTEZA 2014 E-Business in tourism and hospitality industry

Lei, T. O. y Russell A. S. (2014). Perception and reality of managing sustainable coastal tourism in emerging destinations: the case of Sihanoukville, Cambodia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 22, No. 2, 256–278.

Mathieson, A. y. (2012). Economic, physical and social impacts. Longman, London/New York. REDALyC, 79.

Moore, S., Smith, A., & Newsome, D. (2003). Environmental performance reporting for natural area tourism: Contributions by visitor impact management frameworks and their indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 11, 348–375.

Morrison, A.,Carlsen, J.,Weber, P. (2010)Small tourism business research change and evolution. International Journal of TourismResearch 12 (6), 739-749

OMT (1999). Código ético mundial para el turismo. Cuadernos de la Organización Mundial del Turismo, Madrid.

Organización Editorial Mexicana. (2015). Emiten recomendaciones para visitantes a Santuario de las Luciérnagas. LA PRENSA.

Orozco, J. & Núñez, P. (2013). Las teorías del desarrollo. En el análisis del turismo sustentable. InterSedes: Revista de las Sedes Regionales, vol. XIV, núm. 27, pp. 144-167

Osorio, M. (2014). Información Geográfica indexada. Clave geoestadística 29021, 17.

Pollard, S, Kemp, R., Crawford, M., Duarte-Davidson, R., Irwin, J., &Yearsley, R. (2004). Characterizing environmental harm: Developments in an approach to strategic risk assessment and risk management. RiskAnalysis, 24(6), 1551–1560.

Ramírez, V. (25 de Mayo de 2014). Silencio en el santuario de las luciérnagas. EL UNIVERSAL.

Roe, P., Hrymaka, V., y Dimanche F. (2014).Assessing environmental sustainability in tourism and recreation areas: a risk assessment based model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 22, No. 2, 319–338.

Rukuižienė, R. (2014). Sustainable tourism development implications to local economy. Regional Formation and development Studies, no. 3

Saarinen, J. (2006). Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Annals of TourismResearch, 33(44), 1121–1140.

Sánchez Valdés, Arlén; Vargas Martínez, Elva Esther (2015) Turismo sustentable. Un acercamiento a su oferta Multiciencias, vol. 15, núm. 3, pp. 347-354

Schianetz, K., Kavanagh, L., &Lockington, D. (2007). Concepts and tools for comprehensive sustainability assessments for tourism destinations: A comparative review. Journal of SustainableTourism, 15(4), 369–388.

SEMARNAT. (Febrero de 2013). Comisión Nacional Forestal. Consultado el 12 de febrero de 2016. Obtenido de http://www.conafor.gob.mx/.

Serrano, R. Et al. (2010).Turismo armónico como estrategia sustentable para una comunidad del Estado de México. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, vol. 19, núm. 6, pp. 970-993

Simon, D. (1989). Sustainable development: theoretical construct or attainable goal? Environmental Conservation, 16(1): 41-48

Smith, M., & Duffy, R. (2003). The ethics of tourism development. London: Routledge.

Stankey, G., Cole, D., Lucas, R., Petersen, M., &Frissell, S. (1985). The limits of acceptable change (LAC) system for wilderness planning. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: General Technical Report INT-176. Obtenido de: http://www.fs.fed.us/r8/boone/documents/ lac/lacsummary.pdf.

Swarbrooke, J. (2000). Turismo sustentável. Conceitos e impacto ambiental. Aleph.

Tarlombani, M. (2005). Turismo y sustentabilidad: Entre el discurso y la acción Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, vol. 14, núm. 3, pp. 222-238

Twining-Ward, L., & Butler, R. (2002). Implementing STD on a small island: Development and use of sustainable tourism development indicators in Samoa. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(5), 363–387.

U.N. World Tourism Organization. (2015). UN world tourism organization annual report 2014. Obtenido de: http://dtxtq4w60xqpw.cloudfront.net/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_annual_report_2014.pdf

U.N. World Tourism Organization. (2013). Sustainable tourism for development. Obtenido de: http://www.unwto.org/ebook/sustainable- tourism-for-development

United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. (1993). Agenda 21: Programme of action for sustainable development. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) & World Tourism Organisation (WTO). (2005).Making tourism more sustainable: A guide for policy maker. Paris/Madrid: Author.

Vargas, E. Castillo, M. &Zizumbo, L. (2011). Turismo y sustentabilidad. Una reflexión espistemológica. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, vol. 20, núm. pp. 706-721

Williams, P.W. (1994).Frameworks for assessing tourism’s environmental impacts. In J.R.B. Ritchie and C.R. Goeldner (Eds.), Travel, tourism and hospitality research: A handbook for managers and researchers (pp. 425–436). New York: Wiley.

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future – The Brundtland report. New York: Oxford University Press.

Warnken, J., & Buckley, R. (1998). Scientific quality of tourism environmental impact assessment. Journal of Applied Ecology, 35, 1–8.

Zografos, C., & Oglethorpe, D. (2004). Multi-criteria analysis in ecotourism: Using goal programming to explore sustainable solutions. CurrentIssues in Tourism, 7(1), 20–43.