|

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS |

|

Internationalization of Family Business Groups: Content Analysis of the Literature and a Synthesis Model

Özlem Yildirim-Öktem a,*,Nisan Selekler-Goksen

a Bogazici University. Department of International Trade Hisar Campus, 34340 Bebek/Istanbul

Received 2 February 2018; accepted 29 April 2018

Available online 30 june 2018

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M1

KEYWORDS

Family business, Family business groups, internationalization, content analysis, literature review, emerging economies.

Abstract Family business groups are dominant economic actors in emerging economies and play an important role in economic development and globalization efforts of their countries. This study reviews the literature on internationalization of family business groups by conducting a content analysis on 80 articles published in selected categories of SSCI journals between 2000 and 2015. Each article was coded along six dimensions and a model synthesizing the past findings was developed. Gaps in the literature were identified and avenues for further research were proposed, pointing out to variables and theories that may be considered.

CÓDIGOS JEL

M1

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresas familiares, grupos de empresas familiares, internacionalización, análisis de contenido, revisión de la literatura, economías emergentes.

Internacionalización de los grupos de empresas familiares: análisis dela literatura y modelo sintético

Resumen Los grupos de empresas familiares son los actores dominantes dentro de la economías emergentes y juegan un importante papel dentro del funcionamiento de la economía y del esfuerzo globalizador de sus países. Este trabajo analiza la literatura sobre internacionalización en grupos de empresas familiares mediante el análisis de contenido de 80 artículos publicados in categoría seleccionadas del SSCI entre los años 2000 y 2015. Cada artículo ha sido codificado en 6 dimensiones y un modelo que sintetiza los hallazgos pasados y su desarrollo. Se identificaron lagunas en la literatura y se proponen vías para futuras investigaciones, señalando las variables y teorías que pueden considerarse.

Introduction

Family firms play key roles in economies of both developed and developing countries (Schulze & Gedajlovic, 2010). They are not only currently predominant in Asia, Latin America, Europe and the US but also expected to remain an important feature of global capitalism for the foreseeable future (Aguilera & Crespi-Cladera, 2016). They have also drawn much scholar attention in pioneering journals (Short, Pramodita, Lumpkin & Pearson, 2016). Much of this attention has been directed to family firms of small and medium size although conglomerate-like family firms are relatively neglected. As a variant of the form named as business groups (BGs), family business groups (FBGs) emerge as the dominant form of organizing in many emerging economies (Khanna & Rivkin, 2001).

A BG can be defined as “collections of legally independent firms, operating in multiple (often unrelated) industries, which are bound together by persistent formal (e.g. equity) and informal (e.g. family) ties’ (Khanna& Yafeh, 2007, p. 331). A variant but widely prevalent type of this form is family business groups (FBGs). Different from typical stand-alone family firms, FBGs are large and unrelatedly diversified through legally separate firms. Families maintain control over the FBG through centralized management structures, cross-shareholdings, multiple directorates and key management positions within the group, social integration based on family ties as well as by grooming sons and daughters to succeed the founding patriarchs (Granovetter, 1995; Lin, 2003; Wailerdsak, 2008). Additionally, they are characterized by pyramidal ownership structures that lead to disparity between ownership and control rights. Pyramidal structures also enable families to control firms in which they have minority stakes through their majority ownership in the controlling center of the group, a flagship company, or intermediary firms (Chung and Mahmood, 2010; Sarkar, 2010).

FBGs can be exemplified by Korean chaebols, Indian business houses, Latin American grupos, Taiwanese qiyejituan, and Turkish holding companies (Guillen, 2000). They have been the driving force of their countries’ economic development (Wailerdsak and Suehiro, 2010) and despite significant changes in the economic and institutional environments of these countries, they have been persistent and resilient (Kim, 2010). The largest FBGs account for a significant percentage of their country’s total output; majority of the largest firms are their affiliates, and a significant percentage of the total labor force is employed by these groups (Chung & Mahmood, 2010; Colpan, 2010; Kim, 2010; Sarkar, 2010). For example, while 54% of the total market capitalization in Indonesia is held by firms that belong to FBGs (OECD, 2012), 50 percent of the largest companies in both Turkey and Mexico are either FBGs or their affiliates (Hoshino, 2010; ISO, 2016).

As key economic actors in their contexts, internationalization of FBGs can be expected to play an important role in economic development of their countries. Over the last two decades, a key change in many of these markets has been a clear transition to a more liberal regulatory regime which encourages competition, especially from foreign firms (Elango & Pattnaik, 2011). Moreover, as emerging country multinationals, FBGs’ share in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows and cross-border acquisitions has expanded (Guillen & Garcia-Canal, 2009). Home countries of FBGs such as South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia and Chile are among the top 20 countries in terms of outward FDI flows (UNCTAD, 2015). Given these developments, time is ripe for a literature review on internationalization of FBGs.

Although the topic of internationalization is receiving increased attention in family business research (Casillas, & Moreno-Menendez, 2017; Pukall & Calabro, 2014), the extent to which research on stand-alone family businesses is generalizable to FBGs is questionable due to the particularities of FBG as an organizational form. Financial constraints, inadequate level of technology, and managerial expertise, which are stated as some of the impediments for internationalization of stand-alone family businesses (Gallo & Pont, 1996), do not characterize FBGs, rather their richness in such resources creates opportunities for them. As conglomerates with strong internal capital markets, FBGs are shielded from the financial constraints that most stand-alone family firms face. In addition, sharing a common managerial pool enables each constituent firm to benefit from the technological and marketing capabilities of other group members and facilitate foreign expansion (Kim, 2010). In countries with scarce qualified human resources, attracting and sharing talented personnel within a group provides substantial competitive advantages for FBGs vis-a-vis stand-alones. Moreover, as having grown through unrelated diversification, FBGs are more used to establishing alliances with third parties such as the state, multinationals, or other domestic companies in comparison to stand-alone family firms in developed or developing countries. Finally, most FBGs can often replicate group-level resource advantages in foreign markets (Guillen, 2002). When a group firm enters a foreign market, sister-affiliates in that market may constitute reliable partners to do business with and learn from about the local environment. Additionally, newcomers can benefit from the reputation of earlier entrants of the FBG (Kim, 2010). Thus, sister affiliates can lower entry barriers for one another (Guillen, 2003). These differences between FBGs and stand-alone family firms merit a separate literature review on the internationalization of the former.

The main contributions of this paper are twofold. First of all, this literature review draws attention to a neglected form of family business, FBGs. As the family business field has been reaching its maturity, studying FBGs from a family perspective may provide a potential venue for future family business research. Second, the paper synthesizes the literature on internationalization of FBGs by proposing a model, pointing out the gaps in the literature, and providing suggestions for future research.

The structure of the paper is as follows: The following section provides a description of the review methods. The third section discusses the results of the content analysis while the fourth synthesizes the literature by proposing a model. The fifth section identifies the gaps in the literature and discusses future research directions. Finally, the sixth section concludes.

Research Methodology

Selection of the Reviewed Articles

The articles in the sample were chosen from the journals categorized under “Business”, “Business Finance” “Economics”, “Management”, “Social sciences – Interdisciplinary” and “Sociology” fields by the Web of Science database. In the first step, in order to identify articles on business groups, the following key words, which were previously adopted by Carney, Gedajlovic, Heugens, Van Essen and Van Oosterhout (2011) were used: “business groups”, “chaebols”, “keiretsu”, “grupos”, “business houses”, “pyramids”, “oligarchs”, “quanxiqiye” and “qiye jituan”. Among them, only the articles written in English were chosen.

The time-frame of the articles in the sample is 2000-2015 as internationalization efforts of FBGs in most emerging economies picked up in late 1990s. For example, many East Asian governments removed restrictions on both inward and outward trade and investment after the 1997 financial crises as they became aware of their significance for fueling economic growth (Chung & Mahmood, 2010; Wailerdsak & Suehiro, 2010).

Between 2000 and 2015, there were 558 articles on business groups. The authors read their abstracts and scanned the articles in order to choose those related to internationalization. In this study, internationalization includes both outward and inward internationalization. Although literature’s focus has traditionally been on outward internationalization (Korhonen et al., 1996), inward internationalization may precede and enhance outward internationalization (Welch & Luostarinen, 1988). While choosing the articles, the following key words were used:“international”, “export”, “global”, “international sales”, “foreign shareholder”, “foreign investor”, “foreign ownership”, “foreign subsidiary”, “mode of entry”, “location choice”, “foreign direct investment”, “foreign portfolio investment”, and “international commitment”. These included the key words previously used by Pukall and Calabro (2014) in their review of internationalization of family businesses. Among the pool of 214 articles established at this stage, 88 were eliminated as internationalization was not their main topic and variables related to internationalization were only used as control variables. Among the remaining 126 articles, the hypothetical-deductive papers had at least one hypothesis related to internationalization of BGs while conceptual papers or case studies had at least one sub-title reserved for internationalization (e.g. Chu, 2009; Pananond, 2007). Finally, 46 articles were eliminated because they were about Japanese, Chinese or Russian business groups which are not family-owned and -controlled. Eliminations were done by the consent of both authors at all stages. The final sample was composed of 80 articles.

The 80 articles were from 39 different journals majority of which were under “Business” and “Management” categories of Web of Science. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Journal of International Management and International Business Review were the top three outlets in terms of publishing internationalization of FBG articles; each had published six articles between 2000 and 2015. These three journals were also manually scrutinized for the research period to ensure that no relevant article was missed. Additionally, two SSCI journals with “family business” in their names, Journal of Family Business Strategy and Family Business Review, were also manually checked for articles on FBGs for the research period. The search led to identification of six articles, none of which was about internationalization.

Content Analysis

In order to review the literature systematically, a content analysis was conducted. Each article was coded along six dimensions; theme/category, findings/insights, research context, type of study, theory and family-related variables (see Appendix 1). Coding was done by both authors.

The first dimension regards the theme/category of the study in order to reveal the most frequently studied topics in internationalization of FBGs, to identify how the topics of interests have changed over time, to point out the neglected areas of study and to suggest potential avenues for future research on internationalization of family businesses. The initial coding scheme included one pre-determined theme “Globalization of FBGs” and three categories under this theme, namely, antecedents, processes, and consequences of globalization. A new theme/category was created when an article could not be coded under existing themes/categories. During the coding process, two new themes emerged.

The first emergent theme was labeled as “internationalization and corporate governance” and included articles that were at the intersection of internationalization and topics related to corporate governance. Two categories were created under this theme. The first one is called as the “impact of corporate governance” and it includes articles mainly on the role of good governance structure in attracting foreign investment. The second category of articles under this theme investigates the impact of foreign ownership on various firm characteristics and performance, and was labeled as “impact of foreign investors”.

The second emergent theme was labeled as “Impact of FBG as an organizational form on internationalization”. Initially, four different categories were created under this theme. The first category included articles related to the impact of FBG affiliation on internationalization, while the three other categories were comparative in nature, comparing FBG affiliates with stand-alone firms or sister affiliates, or subsidiaries of developed country multinationals along various aspects of internationalization. However, there were only a few articles that compared affiliates within the same FBG, and affiliates of FBGs with subsidiaries of developed country MNEs. Therefore, the categories that were comparative in nature were merged into one category. In the final coding scheme, the third theme has two categories; namely, “Impact of FBG as an organizational form” and “Comparative studies on FBG affiliates”.

The second dimension in the content analysis synthesizes the findings/insights related to internationalization of FBGs with respect to each theme/category. The third dimension focused on the context of the study to reveal the settings that have taken utmost attention by the scholars in the field throughout the research period as well as understudied or up-and-coming research contexts for studying FBG internationalization. The fourth dimension probed the type of study. Articles were coded as conceptual papers, empirical papers, case studies, and papers based on theoretical models. For empirical papers in the sample, main variables were also coded in order to arrive at a synthesis model of the literature. The fifth dimension concentrated on the theories used in order to see which theories are most commonly used to study internationalization of FBGs and how these theories form basis for different topics in the literature on internationalization of FBGs. The sixth dimension aimed to identify the family-related variables used in relation to internationalization efforts of FBGs.

Results of the content analysis

Themes and Findings

In this section, findings are synthesized in line with the themes in the content analysis, namely (1) Globalization of FBGs, (2) Internationalization and corporate governance, and (3) Impact of FBG as an organizational form on internationalization.

Globalization of FBGs

The first theme, globalization of FBGs, includes three categories, namely, antecedents, processes, and consequences of globalization. Papers analyzing the antecedents of internationalization focus either on country- or FBG-level variables. Both groups of articles, however, commonly make references to the institutional environments in which FBGs are embedded, with a particular attention paid to the role of the state. At the macro level, internal and external liberalization efforts of governments and changes in the domestic market pushed FBGs to internationalize (e.g. Chu, 2009; Gökşen & Üsdiken, 2001; Stucchi, Pedersen, & Kumar, 2015). The group-level effects, on the other hand, can emerge either from family ownership and management or group-specific characteristics such as technical capabilities and, age, size and prior international experience of the group. While influence of the family tends to be positive (e.g. Chung, 2014; Lin, 2014; Singh and Gaur, 2013), group resources also emerge as significant (Kim & Lee, 2001; Kumar et al., 2012). Findings also draw attention to the effect of family’s ties both with the state and within the group on internationalization success (Chen and Jaw, 2014; Rugman and Oh, 2008; Siegel, 2007). Pananond (2007), however, finds an increasing significance of technological capabilities vis-a-vis personalized networks as a determinant of internationalization success as a result of institutional changes following the East Asian crisis.

Papers focusing on the process of internationalization probe either how FBGs internationalize over time or the strategic choices made during their internationalization processes. This category of papers reveals that in many countries or regions, such as South Africa (Chabane et al., 2006), Italy and Spain (Binda & Colli, 2011), and Indonesia (Carney & Dieleman, 2011), FBGs’ level of internationalization has increased. However, similar to MNEs in developing countries (Rugman and Oh, 2008), they have mostly internationalized in their own regions the institutional and cultural environments of which they are familiar with (e.g. Borda-Reyes, 2012; Carney, 2005a). Articles focusing on strategic decisions made by FBGs throughout the internationalization process suggest that the gradual process of learning and commitment model does not apply to emerging economy MNEs; rather the roles of networks, acquisitions, big step commitments, availability of human resources, institutional environment of the home country and possible managerial biases should be taken into account (Elango & Pattnaik, 2011; Meyer & Thainjongrak, 2013). Impacts of FBG-level international experience and intra-group learning have also been studied, drawing attention to their effect on modes and timing of affiliates’ foreign market entry.

The relatively smaller number of papers on consequences of internationalization draws attention mainly to its positive impact on innovation (e.g. Chittoor, Aulakh, & Ray, 2015), complexity of firm’s technological capabilities (Lamin & Dunlap, 2011) and innovativeness under certain group characteristics (Mahmood & Zheng, 2009).

Internationalization and Corporate Governance

This theme has two categories: the impact of corporate governance in attracting foreign investment and effects of foreign investors on FBGs. Papers which analyze the impact of firm governance on attracting foreigners as joint venture partners or institutional investors almost exclusively emphasize the negative effect of disparity between family ownership and control, which is a characteristic of emerging country FBGs. Foreign equity ownership is generally higher for FBG firms than stand-alone firms (Baek et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2013). However, excessive ownership-control disparity has a negative influence on the FBGs’ ability to attract both foreign portfolio investment (Kim et al., 2011) and being chosen as a JV partner (Choi et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2009). It emerges as a problem particularly in attracting foreign industrial, vis-a-vis foreign financial, investors (Choi et al., 2014) and investors from countries with low ownership-control disparity (Luo et al., 2009). In emergence of different foreign equity configurations, articles in this category highlight the role of governance model in the foreign investor’s home country, type of foreign investor, and governance structure of the domestic firm.

Articles focusing on the effects of foreign involvement on FBGs find that entry of foreigners as portfolio investors or IJV partners has an impact on firm’s performance, strategic decisions, and governance. Foreign ownership improves firm performance (Baek et al., 2004; George & Kabir, 2012). It also affects FBG strategies by accelerating group divesture (Chung and Luo, 2008), decreasing the tendency for asset reduction (Park and Kim, 2008), and facilitating outward FDI (Bhaumik et al.,2010). Involvement of foreigners, particularly institutional investors, seems to enhance corporate governance by playing the important role of monitoring (Bae & Jeong, 2007; Choi et al., 2013, Kim, 2011). However, partnering with a foreign firm does not necessarily lead to a change in terms of professionalization of the board (Yildirim-Öktem & Üsdiken, 2010). Board composition of the IJV varies with different foreign equity configurations (Ertuna &Yamak, 2011) and the performance premium depends on the alignment between the governance structure and the social context (Chung & Luo, 2013; Yamak et al., 2015). In examining the impact of foreign ownership, articles in this category draw attention to the need to differentiate between different types of foreign investors (portfolio versus institutional), their origins (home countries with shareholder- versus stakeholder-based corporate governance systems), and the importance of fit between structure and context.

Impact of FBG as an Organizational Form on Internationalization

The third theme has two categories, respectively named, impact of FBG affiliation on internationalization and comparative studies on FBG affiliates. The first category of articles investigates the effects of intra-group interaction on internationalization and points out that the unique group structure not only helps to overcome institutional failures in emerging countries but also provides benefits to affiliated firms in deregulated, globally competitive markets on an ongoing basis. Group affiliation helps the member firms to internationalize more rapidly, and reduce the chances of making mistakes due to liabilities of foreignness. Coordinative knowledge-sharing (Lee & MacMillan, 2008) and vertical integration among affiliates (Le & He, 2009) provide mutual support and enhance foreign subsidiary performance. Affiliate firms benefit from other group members’ resource bases such as knowledge, connections, skills and experiences in foreign markets (Guillen, 2002; Elango & Pattnaik, 2007; Lamin, 2013; Lee & MacMillan, 2008) while their parent firms create buffers against the risks they may face in international markets (Becker-Ritterspach & Bruche, 2012). However, resources available within FBGs have limits to be exploited. First, there is heterogeneity among group affiliated firms in terms of the attention and support received from the parent for internationalization (Gubbi, Aulakh, & Ray 2015). Second, group resources are mostly region-bound and do not provide benefit in institutionally different contexts (Borda-Reyes, 2012).

Most of the articles in the second category of the third theme compare FBG affiliates and stand-alone firms on the basis of internationalization strategies and/or performance. While there is more consensus on that FBG affiliates are advantaged in attracting foreign ownership (Kim, 2012; Sarkar & Sarkar, 2008), whether they have a greater tendency to be local (Carney et al., 2011; Chari, 2013) or foreign market-oriented (Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray, &Aulakh, 2009) vis-à-vis stand-alone firms is open to dispute. Findings are also equivocal regarding the moderating effect of BG affiliation on the internationalization - firm performance relationship (Gaur and Kumar, 2009; Singla and George, 2013). A smaller group of articles in this category compares FBG affiliates with other affiliates in the same group or affiliates of other groups or MNC subsidiaries, focusing on learning and knowledge transfer patterns (Banerjee, Prabhu & Chandy, 2015; Lee, Park, Gauri, & Park, 2014a).

Research context and type of study

The literature survey shows that internationalization of Korean chaebol and Indian business houses drew more attention than that of FBGs from other contexts. They establish more than sixty percent of the sample. In the first half of 2000s, Koran chaebol is the only FBG which drew scholarly attention. This is understandable as Korean industrialization efforts and internationalization preceded other late industrializing economies. Indian business houses, on the other hand, take scholarly attention only after 2008, but establish almost seventy five percent of the articles in the last five years of the research period. Studies on internationalization of FBGs from countries other than those from South East Asia (e.g. Latin American grupos and Turkish family holdings) are very rare. This is probably because of the pioneering role of South East Asian FBGs in emerging economies’ internationalization efforts.

Empirical studies establish more than three fourths of the articles included in the study. They are particularly dominant in the last five years of the research period (2011-2015). Case study methodology, on the other hand, is mostly adopted when analyzing antecedents, processes and consequences of internationalization. They include single or multiple cases at the country- or FBG-level. There are also a few conceptual papers all of which are about the process of internationalization.

Theories

Institutional theory emerges as the dominant theoretical paradigm independent of the themes/categories. Almost half of the articles in the sample use institutional theory alone or together with another theory. This tendency can be attributed to the need to explain the distinctive characteristics of the organizational form by referring to the idiosyncrasies of the context shaping the form. Articles use institutional theory to investigate the impact of (i) institutional changes in FBGs’ home markets on internationalization efforts and mode of entry, (ii) similarities/differences in institutional environments between home and host markets on location, mode choice and performance, (iii) institutional development in shaping the consequences of internationalization as well as (iv) both formal and informal institutions with a focus on the role of the state. However, mainstream family business internationalization literature neglects the context to some extent and thus makes less use of institutional theory (Pukall & Calabro, 2014).

Agency theory emerges as the second most frequently used theory and pervades articles related to internationalization and corporate governance (Theme 2). Mainstream use of agency theory in corporate governance literature draws attention to the conflict between owners and managers, as the theory emerged from Anglo-Saxon economies where there is a separation of ownership and control. In emerging economies, on the other hand, the main agency conflict emerges between large and small shareholders due to the ownership-control disparity. In comparison to stand-alone family businesses, the problem of ownership-control disparity is particularly severe in FBGs due to the pyramidal ownership structure of the former. Therefore, the agency problem is converted to a principal-principal conflict rather than a principal-agent one, changing the dynamics of the corporate governance process in the absence of strong protection of minority shareholder rights (Young, Peng, Ahlstom& Bruton, 2008). This, in turn, is reflected to the use of agency theory in FBG internationalization literature by changing the nature of agency conflict taken into consideration. The contextual differences also lead to use of agency theory in combination with institutional theory in many cases.

Another commonly used theoretical framework is resource-based perspectives, such as and typically the RBV. As in the mainstream international business literature (e.g. Beleska-Spasova, Glaister & Stride, 2012; Pehrsson, 2015; Stoian, Rialp & Rialp, 2011), RBV is particularly common in analyzing antecedents and processes of globalization. It has a tendency to be used in combination with other theories in general and with institutional theory in particular. Social capital is regarded as the most significant resource for FBG internationalization and in a parallel manner, personal network of the family, ethnic ties, and political ties also draw attention. Additionally, past experience of the group firms and technological and marketing resources available to the group are also considered significant. This draws attention to the afore-mentioned (Carney, 2005b; Guillen, 2000) vitality of social capital in emerging economies. Contrary to the FBG literature where familial ties with external stakeholders primarily the bureaucrats and politicians in power are more critical sources of social capital, family business literature has traditionally an internal focus (e.g. Pearson, Carr & Shaw, 2008) although the significance of familial connections with external stakeholders have been more recently emphasized (Miller & Le Breton Miller, 2005, Sharma, 2008, Ward 2004).

Although no other theory emerges as a dominant paradigm, references are also made to network, learning and knowledge literatures (e.g. Lee et al, 2014a; Lee, Ryu, & Kang, 2014b; Lee and MacMillan, 2008; Mursitama, 2006). As seen in Appendix 1, approaches widely used in traditional international business literature are not used as frequently as institutional theory and agency theory. For example, Meyer & Thaijongrak (2013) do not see the Uppsala Model as applicable to FBGs. This, in turn, is understandable given that FBGs started their internationalization processes as already large enterprises which are capable of making FDI through acquisitions. Therefore, the springboard perspective is seen more applicable to them (e.g. Elango & Pattnaik 2011; Popli & Sinha, 2014). In the few articles OLI paradigm is used, attention is drawn to that ownership advantages of FBGs are geographically-bound; they are likely to provide advantages in international efforts oriented towards neighboring countries.

Family Dimension

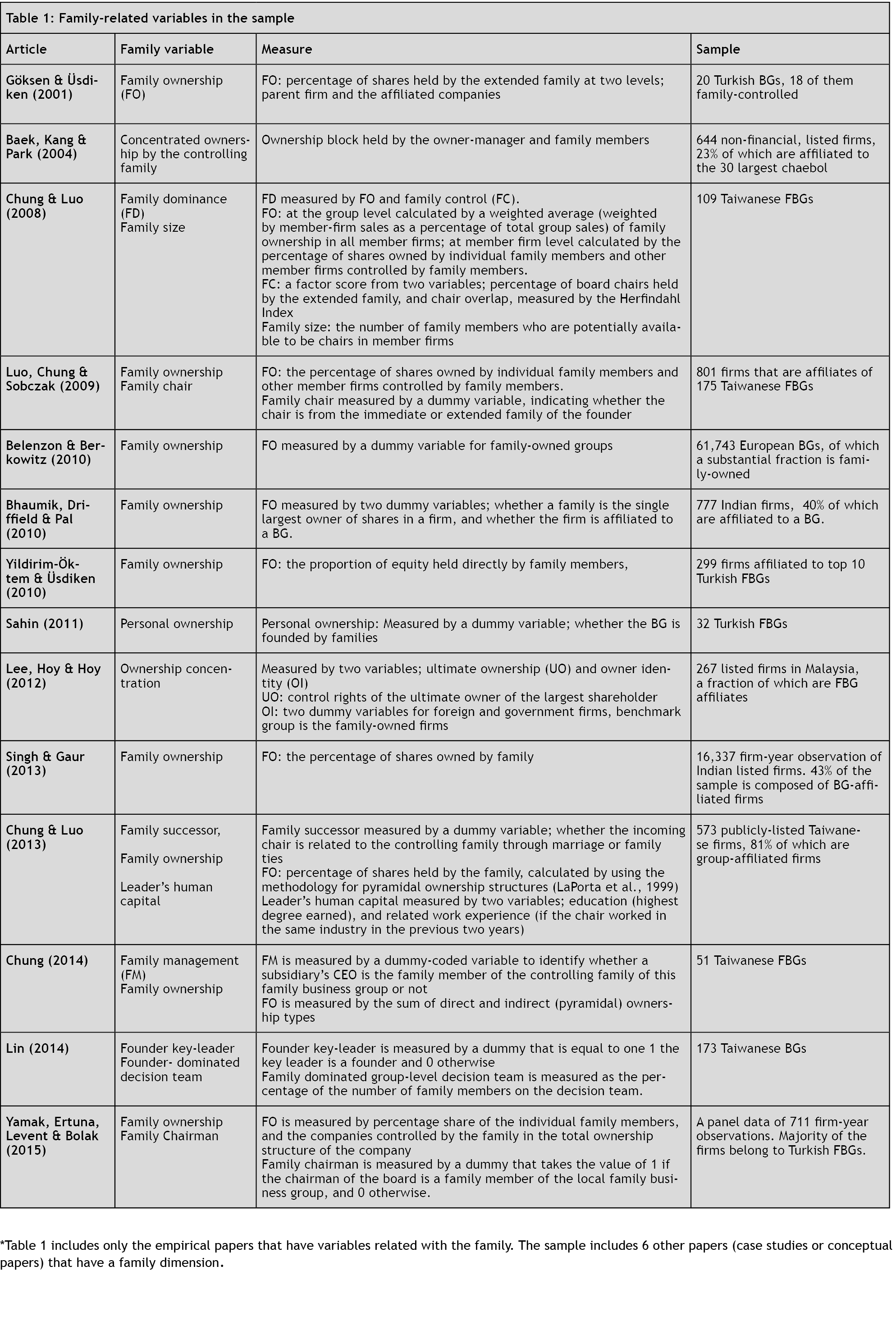

Among the 80 articles in the sample, there are only 19 articles that include a family dimension. In some of these, family variables are not central to the study, but they are used as control variables or to develop alternate hypothesis (e.g. Belenzon and Berkowitz, 2010). This, alone, shows the negligence of the family dimension in studying internationalization of FBGs. As can be seen in Table 1, variables used in these studies are mostly limited to family control through ownership and management. In the sample, there is only one empirical study (Chung & Luo, 2013) that went beyond and took leader’s human capital into consideration.

Family control in FBGs is measured differently than it is in the mainstream stand-alone Family business literature due to the distinctiveness of the organizational form. As FBGs’ ownership structure is pyramidal, the sum of family’s direct and indirect shares at both parent company and affiliated-firm level is calculated to measure family ownership. Similarly, board or executive positions held by family members at both parent- and affiliated-firm levels as well as family domination in the “inner circle” are typical measures to assess the managerial control of the family.

In some of the studies in Table 1, family-related variables are not used to hypothesize a relationship with internationalization, but to develop hypothesis on complementary perspectives used in the paper (e.g. Göksen & Üsdiken, 2001; Lee, Hoy, & Hoy, 2012). The limited number of empirical articles provides mix results about the family’s influence on internationalization. A few studies found detrimental impact of concentrated family ownership (Bhaumik et al., 2010) and family domination in the group’s decision team (Lin, 2014) on outward expansion. Some studies, on the other hand, found a positive influence of family management and pyramidal ownership (Chung, 2014), and presence of a founder-key leader (Lin, 2014) on internationalization. Family ownership was also found to positively moderate the relationship between R&D intensity and amount of foreign investment (Singh and Gaur, 2013).

Conceptual papers and case studies with a family dimension mostly attribute regional concentration of FBGs to family ownership and control. Trust and solidarity based on family and kinship ties act as social mechanisms of integration in the group through which affiliated firms benefit from favorable access to resources, protected from international competition or protect themselves from investment risks in internationalization process (Becker-Ritterspach & Bruche, 2012). However, FBGs remain regionally concentrated because i) entrepreneur’s social capital is geographically more constrained than organizational social capital and FBG’s social capital inheres in the entrepreneur, not in the organization (Carney, 2005a), ii) risk aversion and a desire among family management to retain close control constrain family firms’ international opportunities (Carney & Dieleman, 2011), and iii) families tend to limit participation in the senior management team to a small number of trusted insiders, and are not inclined to recruit professional managers with detailed knowledge of international markets (Carney & Dieleman, 2011). On the other hand, when informal institutions such as familial networks act as substitutes for ineffective formal institutions in an emerging economy, they become critical in creating corporate governance mechanisms that attract foreign investment (Estrin & Prevezer, 2011).

Synthesis of the Literature

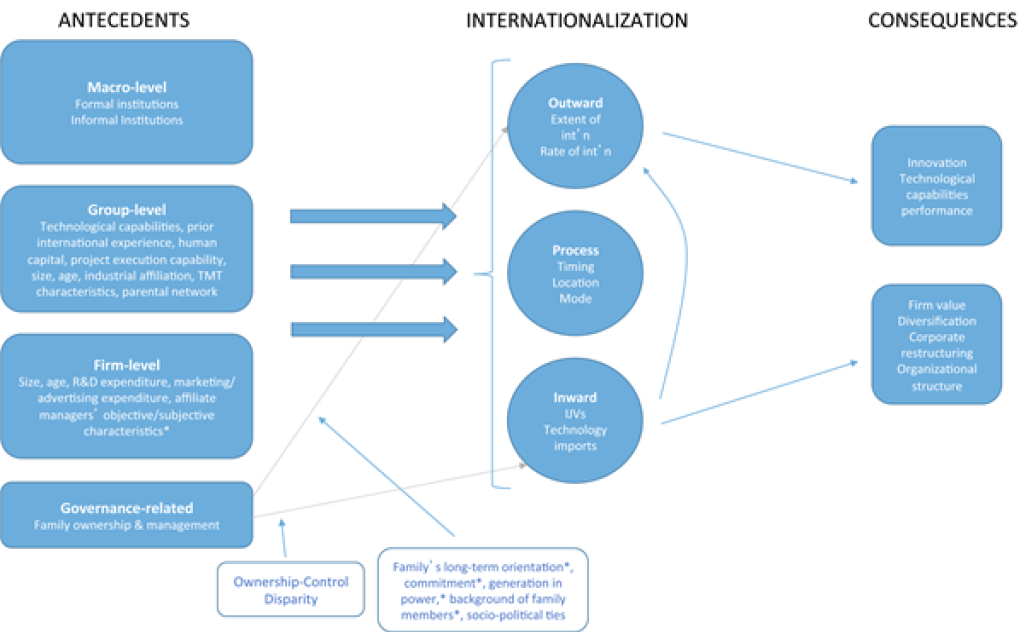

Figure 1 maps a model that synthesizes the previous literature and also proposes new dimensions and relationships that can be taken into consideration in future research. This section also provides guidelines regarding how the top management team of the affiliates and owner families can be incorporated to future studies in this area.

Potential antecedents of internationalization that have been taken into consideration for FBGs in the past studies can be categorized at three levels as institutional-, group- and firm-level. Both formal and informal institutions influence the extent and modes of internationalization. As the state remains to be a key actor in economies of emerging countries, changes in its policies significantly shape both the level and modes of internationalization. Although inward-oriented liberalization policies seem to intensify competition in the home market, they are also likely to be beneficial for FBGs since developed country-based MNCs choose them as partners in the IJVs they establish. FBGs also benefit more from outward-oriented liberalization policies as large enterprises with rich market and non-market resources as well as strong ties to the state. On the other hand, informal institutions such as familial and ethnic ties are also influential in mode and location choice such that FBGs prefer to invest in countries and establish partnerships in countries where they have informal ties. This, in turn, limits the geographical scope of FBGs internationalization.

Group-level characteristics also influence the extent and patterns of internationalization for both the entire group and individual affiliates. Younger and larger groups that operate in more high-tech industries are more likely to internationalize. Different from stand-alone family firms, affiliates within an FBG learn from the accumulated experience, networks and resources of both the parent company and the sister affiliates. Previous choices made by sister affiliates regarding location and mode of investment are likely to affect subsequent decisions made by other affiliates within the same FBG. Expanding into the same country enables utilization of the reputation, knowledge, and network ties of the sister affiliate. Mode of entry choice, on the other hand, tends to diffuse across the FBG due both to mimetic tendencies and experience accumulated in the FBG regarding the difficulties and advantages of a particular mode throughout the process of implementation. However, affiliates benefit from group resources at varying degrees. Those affiliates that have a prominent position in the group as they are the core firm, the first firms around which group has grown over time, or the main firm in the flagship industry of the group are more likely to draw the necessary attention, resources and support for internationalization.

As is the case for mainstream internationalization literature, the technological and marketing capabilities of individual affiliates, their experience in certain locations and with certain modes of foreign market entry, size and age are potential antecedents of internationalization at firm-level. However, characteristics of affiliates’ top management teams are neglected to a significant extent and how they can be integrated to the model will later be further discussed.

Governance-related characteristics of the FBGs influence both outward and inward internationalization. The impact of family ownership and management on the extent of outward internationalization is likely to depend on family characteristics because an important strategic decision such as internationalization is very likely to be made by the family and the inner circle insiders. Additionally, FBGs, as dominant economic actors in their countries with well-established reputation, as well as business and political ties, are likely to attract more foreign direct investment than stand-alone firms. However, the governance structure of the group and the affiliate may act as a moderating variable. Existence of severe ownership-control disparity has the potential to negatively influence the ability to attract foreign investors, especially those from contexts where such disparity does not exist.

Finally, as can be seen in the model, inward internationalization of an affiliate influences its strategy, organizational and governance structure and performance. It increases transparency and accountability, creates a tendency for higher performance and decreases unrelated diversification. It also fosters outward internationalization which, in turn, improves innovativeness and technological capabilities.

Figure 1: Synthesis Model of the Literature

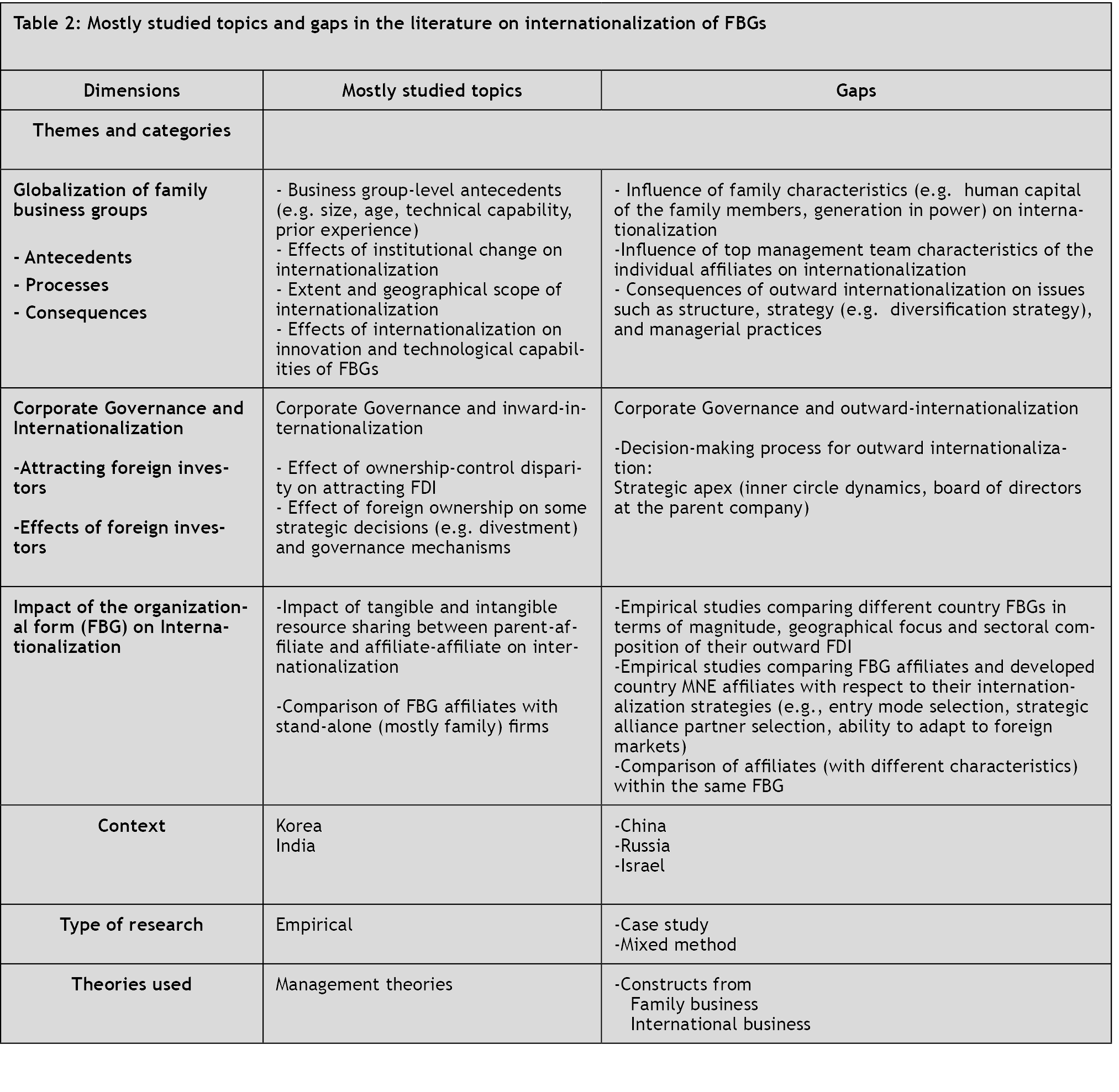

Gaps in the Literature and Suggestions for Further Research

As can be seen in Table 2, although antecedents of internationalization have been intensely studied at the group-level, influence of family characteristics on internationalization is largely ignored. As it was discussed in the previous section, only a small percentage of articles in the sample include variables about the family and most of them are limited to ownership and control variables. However, an important strategic decision such as internationalization is very likely to be influenced by the characteristics of the family since it is the key decision-maker as the most important actor in the ownership and management of the group. Additionally, firm-level antecedents were also neglected in FBG internationalization literature although this, naturally, is the core of mainstream family business internationalization literature.

Further studies on FBGs’ internationalization can incorporate objective and subjective characteristics of affiliate’s top management team (e.g. education, international experience and orientation, propensity to take risks as well as commitment to internationalization) which are widely studied in international business literature (e.g. Leonidou, Katsikeas & Coudounaris, 2010; Wheeler, Ibeh & Dimitratos, 2008). Thus, the proposed model incorporates top management team characteristics of individual firms.

Families’ longer-term horizon and commitment to the persistence and proliferation of their group are likely to have a positive impact on their willingness to make investment in foreign countries, leading to a positive relationship between family ownership and management on the one hand, and extent of outward internationalization on the other. Generation in power is also likely to be an influential characteristic for internationalization. International business literature points out that younger and more educated managers who have more international exposure have a greater tendency to be open to internationalization. Therefore, succession to younger generations who have been groomed to overtake management from the founding patriarch is likely to enhance the extent of internationalization. The model proposes family characteristics as potential variables that moderate the relationship between governance-related characteristics and both extent and scope of internationalization.

Consequences of internationalization began to take attention only in the last years of the research period and are studied mostly with regard to innovation and technological capabilities. However, consequences of outward expansion on issues such as structure, managerial practices, and strategy (e.g. diversification strategy) of FBGs is largely missing. Expansion into foreign markets increases exposure to different structural models and managerial practices, of which parent companies become aware through the knowledge transfer from foreign subsidiaries. This in turn may influence the way of doing things in affiliated firms in the domestic market.

Intersection of literatures on corporate governance and internationalization of FBGs has a focus on inward internationalization and provides insights on the importance of corporate governance in attracting foreign investment. Conversely, literature on corporate governance of FBGs and outward internationalization is largely missing. Dynamics in the strategic apex of the FBG and decision-making processes among the small cadre of inner circle family/managers remain to be a gap as well.

Impact of parent-affiliate and affiliate-affiliate tangible and intangible resource sharing on internationalization and comparison of FBG affiliates with stand-alone (mostly family) firms have also been studied intensely. However, large-scale empirical studies comparing different country FBGs in terms of magnitude, geographical focus and sectoral composition of their FDI is missing. Another gap in this theme is the dearth of empirical studies comparing FBG affiliates and developed country MNE subsidiaries with respect to their internationalization strategies. Such studies may contribute to the discussions on the convergence/divergence of organizational forms on a global basis.

This literature survey also shows that internationalization of FBGs is analyzed in the context of a few countries. Literature needs to be broadened to include FBGs from newly industrializing and/or internationalizing countries since there may be precursors of new variants of multinational companies. For example, as their privatization process continues and percentage of family shares increases in their ownership structure, China is likely to provide an interesting setting for family business research. In order to broaden and deepen the understanding of FBG internationalization, there is need for more case-studies and studies using mixed-method design. Direct contact with the decision-makers would decrease the need to rely on archival data, which may not be complete and/or rigorous in developing countries. Finally, there is a need to go beyond the mainstream theories of management to include constructs developed by both family business and international business literatures.

Conclusion

This study enriches reviews on internationalization of family firms by focusing on FBGs, which differ from small- and medium-sized family firms. Building on past reviews (e.g. Casillas, & Moreno-Menendez, 2017; Pukall & Calabro, 2014), a content analysis was conducted along six dimensions; theme/category, findings/insights, research context, type of study, theory, and family dimension. The results of the content analysis revealed that FBG internationalization literature has both differences and commonalities with the literature on family business internationalization. While certain themes such as process of internationalization and impact of governance on internationalization are widely studied in both streams, research contexts and the theories used differ significantly. Moreover, the family dimension is largely missing in the FBG literature and this, in turn, creates a wide gap.

There are two main neglected issues, namely, the impact of family and affiliate management characteristics on internationalization. The significance of these characteristics is widely recognized in international business literature and they need to be integrated to the FBG internationalization literature as well. Impact of family on internationalization can be studied through socio-emotional wealth approach (SEW) and the RBV. SEW, which is based on behavioral agency theory, suggests that family firms do not opt for international diversification (Gomez-Mejia, Makri and Kintana, 2010) since families are unlikely to make strategic choices that will cause SEW losses (Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia, 2012). As international diversification requires external funding and involvement of external managerial talent expertise that may not be available among family members, it may lead to loss of family control. However, in the case of FBGs, which have already grown through unrelated diversification and yet still preserved the family dynasty through the parent company, pyramidal ownership, dynastic succession, interlocking directorates, and grooming the new generations for the family business, international diversification may not create high extents of loss aversion. On the other hand, from an RBV perspective, family is a source of human (e.g. education, international exposure) and organizational (e.g. internal and external social capital) resources. In countries where elite education and international business experience are scarce resources, younger generations of these family dynasties who are groomed for overtaking the business, are endowed with these resources. Additionally, in case of emerging economies, state-business relations, which can be pivotal for success, are usually carried out by the family members. On the other hand, contributions of non-family managers in the inner circle can be analyzed through a stewardship perspective. Professional managers with elite education and long tenure can join the inner circle if they display commitment to the family and act as stewards of the family’s and group’s well-being. Knowledge and experience of these managers can also be seen as valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable resources, as is usually done in international business studies based on an RBV framework.

Finally, literature on internationalization of FBGs remains to be a promising research area which can benefit from family business and top management team literatures. On the other hand, research in this area can also contribute to a better understanding of family firms of different context and organizational forms.

References

Aguilera, R.V., & Crespi-Cladera, R. (2016). Global corporate governance: On the relevance of firms’ ownership structure. Journal of World Business, 51, 50–57

Astrachan, J.H., Klein, S.B. & Smyrnios, (2006). The F-PEC scale of family influence: a proposal for solving the family business definition problem. In P.Z. Poutziouris, K.X. Smyrnios, & S.B. Klein (Eds), Handbook of Research in Family Business (pp. 167-180). Northhampton: Edward-Elgar.

Bae, K. H., & Jeong, S. W. (2007). The Value‐relevance of earnings and book value,

ownership structure, and business group affiliation: Evidence from Korean

business groups. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 34(5‐6), 740-766.

Bae, K. H., & Goyal, V. K. (2010). Equity market liberalization and corporate governance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(5), 609-621.

Baek, J. S., Kang, J. K., & Park, K. S. (2004). Corporate governance and firm value: Evidence from the Korean financial crisis. Journal of Financial economics, 71(2), 265-313.

Banerjee, S., Prabhu, J. C., & Chandy, R. K. (2015). Indirect learning: how emerging-market firms grow in developed markets. Journal of Marketing, 79(1), 10-28.

Becker-Ritterspach, F., & Bruche, G. (2012). Capability creation and internationalization with business group embeddedness–the case of Tata Motors in passenger cars. European Management Journal, 30(3), 232-247.

Belenzon, S., & Berkovitz, T. (2010). Innovation in business groups. Management Science, 56(3), 519-535.

Beleska-Spasova, E., Glaister, K.W. & Stride, C. (2012). Resource determinants of strategy and performance: the case of British exporters. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 635–647.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research.Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279.

Bhaumik, S. K., Driffield, N., & Pal, S. (2010). Does ownership structure of emerging-market firms affect their outward FDI? The case of the Indian automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3), 437-450.

Binda, V., & Colli, A. (2011). Changing big business in Italy and Spain, 1973–2003: Strategic responses to a new context. Business History, 53(1), 14-39.

Borda-Reyes, A. (2012). The impact of business group diversification on emerging market multinationals: Evidence from Latin America. Innovar, 22(45), 97-110.

Cardenas, J. (2015). Are Latin America’s corporate elites transnationally interconnected? A network analysis of interlocking directorates. Global Networks, 15(4), 424-445.

Carney, M. (2005a). Globalization and the renewal of Asian business networks. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 22(4), 337-354.

Carney, M. (2005b). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249-265.

Carney, M., & Dieleman, M. (2011). Indonesia’s missing multinationals: Business groups and outward direct investment. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 47(1), 105-126.

Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E. R., Heugens, P. P., Van Essen, M., & Van Oosterhout, J. H. (2011). Business group affiliation, performance, context, and strategy: A meta-

analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 437-460.

Casillas, J.C., Moreno-Merendez, A.M. (2017). International business & family business: Potential dialogue between disciplines. European Journal of Family Business, 7, 25-40.

Castañeda, G. (2007). Business groups and internal capital markets: the recovery of the Mexican economy in the aftermath of the 1995 crisis. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(3), 427-454.

Chabane, N., Roberts, S., & Goldstein, A. (2006). The changing face and strategies of big business in South Africa: more than a decade of political democracy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 15(3), 549-577.

Chari, M. D. (2013). Business groups and foreign direct investments by developing country firms: An empirical test in India. Journal of World Business, 48(3), 349-359.

Chen, Y.Y., & Jaw, Y.L. (2014). How do business groups’ small world networks effect diversification, innovation, and internationalization?. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31, 1019–1044.

Chittoor, R., Sarkar, M. B., Ray, S., & Aulakh, P. S. (2009). Third-world copycats toemerging multinationals: Institutional changes and organizational transformation in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Organization Science, 20(1), 187-205.

Chittoor, R., Aulakh, P. S., & Ray, S. (2015). Accumulative and assimilative learning,institutional infrastructure, and innovation orientation of developing economy firms. Global Strategy Journal, 5(2), 133-153.

Choi, B. B., Lee, D., & Park, Y. (2013). Corporate social responsibility, corporate governance and earnings quality: Evidence from Korea. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 21(5), 447-467.

Choi, H. M., Cho, Y. G., & Sul, W. (2014). Ownership-Control Disparity and ForeignInvestors’ Ownership: Evidence from the Korean Stock Market. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 50(1), 178-193.

Chrisman, J.J., Chua, J.H., & Steier, L. (2005). Sources and consequences of distinctive familiness: An introduction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 237-247.

Chu, W. W. (2009). Can Taiwan’s second movers upgrade via branding? Research Policy,38(6), 1054-1065.

Chung, C. N., & Luo, X. (2008). Institutional logics or agency costs: The influence of corporate governance models on business group restructuring in emerging economies. Organization Science, 19(5), 766-784.

Chung, C. N., & Luo, X. R. (2013). Leadership succession and firm performance in anemerging economy: Successor origin, relational embeddedness, and legitimacy. Strategic Management Journal, 34(3), 338-357.

Chung, C.N. & Mahmood, I.P. (2010). Business Groups in Taiwan. In A.M. Colpan, T. Hikino, & J.R. Lincoln (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Groups (pp. 180-209). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chung, H. M. (2014). The role of family management and ownership on semi-globalization pattern of globalization: The case of family business groups. International Business Review, 23(1), 260-271.

Colpan, A.M. (2010). Business Groups in Turkey. In A.M. Colpan, T. Hikino, & J.R. Lincoln (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Groups (pp. 486-525). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dieleman, M. & Sachs, W.M. (2008). Economies of connectedness: Concept and application. Journal of International Management, 14(3), 270-285.

Elango, B., & Pattnaik, C. (2007). Building capabilities for international operations through networks: a study of Indian firms. Journal of international business studies, 38(4), 541-555.

Elango, B., & Pattnaik, C. (2011). Learning before making the big leap. Management International Review, 51(4), 461.

Ertuna, B., & Yamak, S. (2011). Foreign equity configurations in an emerging country. European Management Journal, 29, 117-128.

Estrin, S., & Prevezer, M. (2011). The role of informal institutions in corporate governance: Brazil, Russia, India, and China compared. Asia Pacific journal of management, 28(1), 41-67.

Gallo, M.A., & Pont, C.G. (1996). Important Factors in Family Business Internationalization. Family Business Review, 9 (1), 45-59.

Garg, M., & Delios, A. (2007). Survival of the foreign subsidiaries of TMNCs: The influence of business group affiliation. Journal of International Management, 13(3), 278-295.

Gaur, A. S., & Kumar, V. (2009). International diversification, business group affiliation and firm performance: Empirical evidence from India. British Journal of Management, 20(2), 172-186.

Gaur, A.S, Kumar, V., & Singh, D.A. (2014). Institutions, resources, and internationalization of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business. 49, 12-20.

George, R., & Kabir, R. (2012). Heterogeneity in business groups and the corporate diversification–firm performance relationship. Journal of business research, 65(3),

412-420.

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653-707.

Gökşen, N. S., & Üsdiken, B. (2001). Uniformity and diversity in Turkish business groups: Effects of scale and time of founding. British Journal of Management, 12(4), 325-340.

Granovetter, M. (1995). Coase revisited: Business groups in the modern economy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 4(1), 93-130.

Gubbi, S. R., Aulakh, P. S., & Ray, S. (2015). International search behavior of business group affiliated firms: Scope of institutional changes and intragroup heterogeneity. Organization Science, 26(5), 1485-1501.

Guillen, M. F. (2000). Business groups in emerging economies: A resource-based view. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 362-380.

Guillén, M. F. (2002). Structural inertia, imitation, and foreign expansion: South Korean firms and business groups in China, 1987–1995. Academy of Management Journal, 45(3), 509-525.

Guillén, M. F. (2003). Experience, imitation, and the sequence of foreign entry:Wholly owned and joint-venture manufacturing by South Korean firms and business groups in China, 1987–1995. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(2), 185-198.

Guillén, M. F., & García-Canal, E. (2009). The American model of the multinational firm and the “new” multinationals from emerging economies. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(2), 23-35.

Hoshino, T. (2010). Business Groups in Mexico. In A.M. Colpan, T. Hikino, & J.R. Lincoln (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Groups (pp. 424-457). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Istanbul Chamber of Industry (2016). Turkey’s top 500 industrial enterprises-2016. www.iso.org.tr

Jean, R. J. B., Tan, D., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2011). Ethnic ties, location choice, and firm performance in foreign direct investment: A study of Taiwanese business groups FDI in China. International Business Review, 20(6), 627-635.

Khanna, T., & Rivkin, J. W. (2001). Estimating the performance effects of business groups in emerging markets. Strategic Management Journal, 45-74.

Khanna, T., & Yafeh, Y. (2007). Business groups in emerging markets: Paragons or

parasites? Journal of Economic Literature, 45(2), 331-372.

Kim, B., & Lee, Y. (2001). Global capacity expansion strategies: lessons learned from two Korean carmakers. Long range planning, 34(3), 309-333.

Kim, B. (2011). Do foreign investors encourage value-enhancing corporate risk taking? Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 47(3), 88-110.

Kim, C. S. (2012). Is Business Group Structure Inefficient? A Long‐Term Perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 41(3), 258-285.

Kim, H. (2010). Business Groups in South Korea. In A.M. Colpan, T. Hikino, & J.R. Lincoln (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Groups (pp. 157-179). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kim, H., Kim, H., Hoskisson, R.E. (2010). Does market-oriented institutional change in an emerging economy make business-group-affiliated multinationals perform better? An institution-based view. Journal of International Business, 41, 1141-1160.

Kim, W., Sung, T., & Wei, S. J. (2011). Does corporate governance risk at home affect investment choices abroad? Journal of International Economics, 85(1), 25-41.

Klein, S.B.., Astrachan, J.H., Smyrnios, K.X. (2005). The F-PEC Scale of Family Influence: Construction, Validation, and Further Implication for Theory. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 321-329.

Korhonen, H., Luostarinen, R., & and Welch, L. (1996). Internationalization of SMEs: Inward-outward patterns and government policy. Management International Review, 315-329.

Kumar, V., Gaur, A. S., & Pattnaik, C. (2012). Product diversification and international expansion of business groups. Management International Review, 52(2), 175-192.

Lamin, A., & Dunlap, D. (2011). Complex technological capabilities in emerging economy firms: The role of organizational relationships. Journal of International Management, 17(3), 211-228.

Lamin, A. (2013). The business group as an information resource: An investigation ofbusiness group affiliation in the Indian software services industry. Academy of

Management Journal, 56(5), 1487-1509.

Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D. (2006). Why Do Some Family Businesses Out-Compete? Governance, Long-Term Orientations, and Sustainable Capability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 30 (6), 731-746.

Lee, H., Oh, S., & Park, K. (2014). How Do Capital Structure Policies of Emerging Markets Differ from Those of Developed Economies? Survey Evidence from Korea. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 50(2), 34-72.

Lee, J. Y., & MacMillan, I. C. (2008). Managerial knowledge-sharing in chaebols and its impact on the performance of their foreign subsidiaries. International Business Review, 17(5), 533-545.

Lee, J. Y., Park, Y. R., Ghauri, P. N., & Park, B. I. (2014a). Innovative knowledge transfer patterns of group-affiliated companies: The effects on the performance of foreign subsidiaries. Journal of International Management, 20(2), 107-123.

Lee, J. Y., Ryu, S., & Kang, J. (2014b). Transnational HR network learning in Korean subsidiaries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(4), 588-608.

Lee, K., & He, X. (2009). The capability of the Samsung group in project execution and vertical integration: Created in Korea, replicated in China. Asian Business &mManagement, 8(3), 277-299.

Lee, K. T., Hooy, C. W., & Hooy, G. K. (2012). The value impact of international andindustrial diversifications on public‐listed firms in Malaysia. Emerging Markets Review, 13(3), 366-380.

Leonidou, L. C., Katsikeas, C. S., & Coudounaris, D. N. (2010). Five decades of business research into exporting: A bibliographic analysis. Journal of International Management, 16(1), 78-91.

Liao, T. J. (2015). Local clusters of SOEs, POEs, and FIEs, international experience, and the performance of foreign firms operating in emerging economies. International Business Review, 24(1), 66-76.

Lin, K. V. (2003). Equity ownership and firm value in emerging markets. Journal of

Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 38(01), 159-184.

Lin, W. T. (2014). Founder-key leaders, group-level decision teams, and the international expansion of business groups: Evidence from Taiwan. International Marketing Review, 31(2), 129-154.

Luo, X., Chung, C. N., & Sobczak, M. (2009). How do corporate governance model differences affect foreign direct investment in emerging economies? Journal of International Business Studies, 40(3), 444-467.

Mahmood, I. P., & Zheng, W. (2009). Whether and how: Effects of international joint ventures on local innovation in an emerging economy. Research Policy, 38(9), 1489-150

Meyer, K. E., & Thaijongrak, O. (2013). The dynamics of emerging economy MNEs: How the internationalization process model can guide future research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(4), 1125-1153.

Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Harvard Business Press.

Mursitama, T. N. (2006). Creating relational rents: The effect of business groups on affiliated firms’ performance in Indonesia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(4), 537-557.

OECD (2012). Board Member Nomination and Election, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264179356-en.

Pananond, P. (2007). The changing dynamics of Thai multinationals after the Asian economic crisis. Journal of international management, 13(3), 356-375.

Park, C., & Kim, S. (2008). Corporate governance, regulatory changes, and corporate

restructuring in Korea, 1993–2004. Journal of World Business, 43(1), 66-84.

Park, Y. R., Lee, J. Y., & Hong, S. (2011a). Effects of international entry-order strategies on foreign subsidiary exit: The case of Korean chaebols. Management Decision, 49(9), 1471-1488.

Park, Y. R., Lee, J. Y., & Hong, S. (2011b). Location decision of Korean manufacturing FDI: A comparison between Korean chaebols and non-chaebols. Global Economic Review, 40(1), 123-138.

Pearson, A. W., Carr, J. C., & Shaw, J. C. (2008). Toward a theory of familiness: A social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(6), 949-969.

Perkins, S., Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2014). Innocents abroad: the hazards of international joint ventures with pyramidal group firms. Global Strategy Journal, 4(4), 310-330.

Pehrsson, T. (2015). Market entry mode and performance: capability alignment and institutional moderation. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 15(4), 508–527.

Popli, M., & Sinha, A. K. (2014). Determinants of early movers in cross-border merger and acquisition wave in an emerging market: A study of Indian firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(4), 1075-1099.

Pukall, T. J., & Calabrò, A. (2014). The internationalization of family firms: A critical review and integrative model. Family Business Review, 27(2), 103-125.

Rugman, A. M., & Oh, C. H. (2008). Korea’s multinationals in a regional world. Journal of World Business, 43(1), 5-15.

Sahin, K. (2011). An investigation into why Turkish business groups resist the adoption of M-form in post-liberalization. African Journal of Business Management, 5(34), 3330-3343.

Sarkar, J. (2010). Business Groups in India. In A.M. Colpan, T. Hikino, & J.R. Lincoln (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Groups (pp. 294-323). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sarkar, J., & Sarkar, S. (2008). Debt and corporate governance in emerging economies

Evidence from India. Economics of Transition, 16(2), 293-334.

Schulze, W. S., & Gedajlovic, E. R. (2010). Whither family business? Journal of

Management Studies, 47(2), 191-204.

Sharma, P. (2008). Commentary: Familiness: Capital Stocks and Flows Between Family and Business. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 32 (6), 971-977.

Short, J.C., Pramodita, S., Lumpkin G.T., & Pearson, W.A. (2016). Oh, the places we’ll go! Reviewing past, present, and future possibilities in Family Business Research. Family Business Review, 29 (1), 11-16.

Siegel, J. (2007). Contingent political capital and international alliances: Evidence from South Korea. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(4), 621-666.

Singh, D. A. (2009). Export performance of emerging market firms. International Business Review, 18(4), 321-330.

Singh, D. A., & Gaur, A. S. (2013). Governance structure, innovation and

internationalization: evidence from India. Journal of International Management,19(3), 300-309.

Singla, C., & George, R. (2013). Internationalization and performance: A contextual analysis of Indian firms. Journal of Business Research, 66(12), 2500-2506.

Stoian, M.C., Rialp, A. and Rialp, J. (2011). Export performance under the microscope: a glance through Spanish lenses. International Business Review, 20(2), 117–135.

Stucchi, T., Pedersen, T., & Kumar, V. (2015). The Effect of Institutional Evolution on Indian Firms’ Internationalization: Disentangling Inward-and Outward-Oriented Effects. Long Range Planning, 48(5), 346-359.

Tan, D., & Meyer, K. E. (2010). Business groups’ outward FDI: A managerial resources perspective. Journal of International Management, 16(2), 154-164.

United Nations Conferences on Trade and Development (2015). World Investment Report 2015: Reforming International Investment Governance. UN.

Ward, J.L. (2004). Perpetuating the family business: 50 lessons learned from long-lasting successful families in business. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Wailerdsak, N. (2008). Women Executives in Thai Family Business. In V. Gupta, N. Levenburg, M. Lynda, M. Jaideep, & S. Thomas (Eds), Culturally Sensitive Models of Gender in Family Business (pp. 19-39). Hyderabad: ICFAI University Press.

Wailerdsak, N. & Suehiro, A. (2010). Business Groups in Thailand. In A.M. Colpan, T. Hikino, & J.R. Lincoln (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Groups (pp. 237-265). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Welch, L.S., & Luostarinen, R. (1988). Internationalization: Evolution of a concept. Journal of General Management, 14(2), 34-55.

Wheeler, C., Ibeh, K., & Dimitratos, P. (2008). UK export performance research: review and implications. International Small Business Journal, 26(2), 207-239.

Winters, M. S. (2007). Market Access or Efficient Production: Why Did South Korean Outward Direct Investment Persist After the Crisis? Asian Business & Management, 6(3), 265-284.

Yamak, S., Ertuna, B., Levent, H., & Bolak, M. (2015). Collaboration of foreign investors with local family business groups in Turkey: implications on firm performance.European Journal of International Management, 9(2), 263-281.

Young, Peng, Ahlstom & Bruton, (2008). Corporate Governance in Emerging Economies: A Review of the Principal–Principal Perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 196-220.

Yildirim & -Öktem, Ö., & Üsdiken, B. (2010). Contingencies versus external pressure: professionalization in boards of firms affiliated to family business groups in late-industrializing countries. British Journal of Management, 21(1), 115-130.

|

APPENDIX 1 |

|||||

|

THEME 1A / GLOBALIZATION OF FBGs – ANTECEDENTS |

|||||

|

Article |

Context |

Type of study |

Theory/Approach |

Family dimension |

Findings/insights related to internationalization1 |

|

Kim & Lee (2001) |

Korea |

Case study |

Learning propensity model |

No |

Despite their similar structures, FBGs from the same country (Daewoo and Hyundai) may choose very different internationalization strategies. This selection, in turn, may be influenced by their competitive advantages vis-à-vis each other. |

|

Goksen & Usdiken (2001) |

Turkey |

Empirical |

Institutional theory, Contingency theory |

Yes |

FBGs established in different institutional settings may pursue different internationalization strategies. While FBGs established before liberalization have more international joint ventures and higher export orientation, those established after liberalization have a greater tendency to be engaged in FDI. |

|

Pananond (2007) |

Thai multinationals |

Case study |

None |

No |

There was a shift in the dynamic of Thai multinationals international expansion after the Asian financial crisis. While pre-crisis expansion relied more on network capabilities, the post-crisis strategy placed more emphasis on industry-specific technological capabilities and transforming personalized networks to formal ties. |

|

Siegel (2007) |

Korea |

Empirical |

None |

No |

In Korea, ties through elite sociopolitical networks to the regime in power increased the rate of forming cross-border strategic alliances but being tied through elite sociopolitical networks to the political enemies of the regime in power significantly decreased that rate. Political network ties can be both assets and liabilities. |

|

Winters (2007) |

Korea |

Empirical |

None |

No |

There is not a single explanation for the persistence of outward FDI by Korean FBGs following the financial crisis. For the five biggest Korean FBGs, foreign investment was a way to compensate for declining sales at home whereas other firms used foreign investment to take advantage of production efficiencies. |

|

Dieleman & Sachs (2008) |

Indonesia |

Case study |

Institutional theory* |

No |

The extent to which companies create value through economies of connectedness depends on the institutional environment. In a weak institutional environment, economies of connectedness enhance diversification. |

|

Rugman & Oh (2008) |

Korean chaebols in their region |

Empirical |

OLI* Double diamond framework |

No |

Korean FBGs have home-region oriented advantages coming from business-government relations, knowledge-based capabilities and group benefits. They use firm-specific advantages to operate on a home-region basis like other MNEs. |

|

Singh (2009) |

India |

Empirical |

RBV |

No |

Domestic and export sales are interdependent. R&D expenditure and FBG affiliation positively and advertising expenditure negatively affect export sales. |

|

Tan & Meyer (2010) |

Taiwan |

Empirical |

RBV Institutional theory |

No |

International work experience of executives favors internationalization while international education does not. Domestic institutional resources distract from internationalization, presumably because they are not transferable into other institutional contexts and thus favor other types of growth. |

|

Kumar et al. (2012) |

India |

Empirical |

RBV, Transaction cost economics and Institutional theory |

No |

The inherent trade-off that exists between strategies of product diversification and international expansion holds for emerging market FBGs. Those FBGs that can effectively employ their learning from prior international exposure and their technical competences are better placed to simultaneously pursue both strategies. |

|

Singh & Gaur (2013) |

India |

Empirical |

Agency theory Institutional theory* |

Yes |

While family ownership and BG affiliation have positive impact on R&D intensity and new foreign investments, institutional ownership positively affects new foreign investments. R&D intensity interacts with family ownership, institutional ownership and BG affiliation in affecting new foreign investments. |

|

Chen & Jaw (2014) |

Taiwan |

Empirical |

Embededness and Social network perspectives |

No |

A stronger small world group structure positively relates to a group’s core firm’s degree of internationalization. A core firm located at a preferential structural position in a group may acquire idiosyncratic or complementary resources more efficiently than other affiliates can. BG diversification mediates the relationship between a small world group structure and a group’s degree of internationalization. |

|

Chung (2014) |

Taiwan |

Empirical |

Agency theory, RBV, Transaction cost theory |

Yes |

Both family management and higher degree of pyramidal ownership in the subsidiary of an FBG increases the likelihood that it will choose to engage in host regions rather than the regions the FBG originates from. Family management and pyramidal ownership are also positively related to the choice to engage in a higher difference region instead of a lower difference region. |

|

Lin (2014) |

Taiwan |

Empirical |

Dynamic managerial-capacities perspective |

Yes |

Presence of a founder-key leader and strong-tie group-level decision teams in a BG positively and family-dominated group-level decision teams negatively affect the internationalization of BGs. |

|

Stucchi et al. (2015) |

India |

Empirical |

Institutional theory |

No |

Both inward- and outward–oriented institutional change improve internationalization. Affiliation with a domestic FBG has a buffering effect during periods of institutional evolution only in cases of inward-oriented institutional change. |

|

THEME 1B / GLOBALIZATION OF FBGs - PROCESSES |

|||||

|

Guillen (2003) |

Korean firms in China |

Empirical |

Staged expansion theory, Transaction cost theory and Institutional theory |

No |

Over time technology-intensive firms are more likely to abandon JV entry modes due to contractual hazards. Firms in the same BG imitate each others’ choice of JVs and wholly-owned plants. Firms in the same industry mimic each others’ choice of wholly-owned plants, though not of JVs. |

|

Carney (2005) |

China and ASEAN |

Conceptual |

Agency theory, Institutional theory |

Yes |

FBGs remain regionally concentrated and their new business ventures gravitate to locations (less developed states, characterized by institutional voids) where their attributes offer an advantage. |

|

Chabane et al. (2006) |

South Africa |

Conceptual |

None |

No |

Private investment and inward FDI have remained poor in the last decade in South Africa while outward FDI by South African conglomerates exceeded inward FDI in half of the last decade. |

|

Chu (2009) |

Comparison of Taiwan with Korea and China |

Conceptual |

Institutional theory |

No |

Taiwan’s most successful second movers are brandless subcontractors because the government did not promote national champions from the early days of postwar development. The national system supports upgrading efforts along the subcontracting route, but offers few risk-sharing mechanisms to allow firms to pursue own-brand strategies. |

|

Guillen & Garcia-Canal (2009) |

emerging economies |

Conceptual |

RBV* |

No |

The new MNEs developed at a time of market globalization in which global reach and global scale are crucial. They are the result of both imitation of established MNEs from the rich countries and innovation in response to peculiar characteristics of emerging and developing countries. Established MNEs also adopted some of the behaviors of the new multinationals. |

|

Carney & Dieleman (2011) |

Indonesia |

Case study |

Institutional theory |

Yes |

Very few large Indonesian BGs can be characterized as MNEs; most either are active only in the domestic market or display limited internationalization. This apparent absence of Indonesian MNEs can be attributed to an accounting error, because firms’ outward investment is under-reported in official statistics. However, it may also be a result of a combination of institutional and firm-level factors that avoid the internationalization of all but the largest firms. |

|

Binda & Colli (2011) |

Italy and Spain |

Case study |

None |

Yes |

Even though the home market remained very important, the level of internationalization of the BGs, most of which are FBGs, in both Italy and Spain grew. In both of the countries, the most diversified companies were also the most internationalized ones. Additionally, the more internationalized firms very often chose to adopt the holding or the multi-divisional structure. |

|

Jean et al. (2011) |

Taiwan |

Empirical |

Social network theory |

No |

Taiwanese BGs are more likely to invest in China when they have strong managerial ethnic ties. Ethnic ties of Taiwanese BGs do not help to improve firm performance in China. The impact of managerial ethnic ties decreases with the BGs’ R&D capabilities. |