1. Introduction

The family CEO’s intention to retire seems to be critical to triggering the succession process of family business. Gerontocracy, a form of government in which an entity is governed by leaders who are significantly older than the rest of the members, may generate tension between the incumbent and the successor if the expected timing of leaving and taking over the position is not aligned. This misalignment can have important consequences on the wellbeing and motivation of both the incumbent and successor, as well as the sustainability of the business. In the context of an aging population (Royal Geographical Society, 2019), family CEOs seem quite secure in their jobs and may operate with the expectation that they will be in office for a long time. This late retirement syndrome (Kets De Vries, 2003) is frequently observed in parent founders and can be explained as the fear they may experience letting go, which may represent a loss of status, recognition, income, or emotional stress. This may be a significant factor explaining why family businesses frequently stumble in succession (Ward, 2011; Zahra & Sharma, 2004).

The incumbent’s intention to retire and low motivation to transfer power to a successor remain among the main problems affecting the succession process (Marshall et al., 2006; Sharma et al., 2003). Previous research on aging CEOs and the succession process mainly examines the choice of a successor (Bulut et al., 2019). While family CEOs may understand the benefits of succession planning, in most cases, an incumbent has a difficult time envisioning life without a significant leadership role in the family business (Kets de Vries, 2003). Thus, we argue that retirement intentions precede succession planning, which means the incumbent leader of a family business will initiate and control the succession process as long as he/she plans to retire. Thus, our research explores the following question: What factors influence the incumbent’s intention to retire?

Previous literature dealing with family business CEO aging has explored their entrepreneurial behavior and success (Lévesque & Minniti, 2006; Zhao et al., 2021), the impact of age on formal succession and conflict (Marshall et al., 2006), and even the impact on merger and acquisitions (Jenter & Lewellen, 2015). In order to analyze the incumbent’s retirement intention, we should look at their anticipated retirement age (Gagne et al., 2011), although the subject has been poorly understood (Decker et al., 2016; Long & Chrisman, 2014). According to the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the probability that a behavior will occur depends on an individual’s intention to engage in that behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980;). In the family business context, the incumbent leader’s intentions may be good predictors of his/her behavior. If we better understand the antecedents of retirement intention, we may be able to better predict incumbents’ retirement, thus triggering the succession. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to understand the core factors affecting the incumbent’s intended age of retirement from their own perspective using the theory of planned behavior as a theoretical approach.

In this paper, we contribute to extant literature in several dimensions. First, by considering that retirement intentions precede succession planning, we examine the factors explaining the incumbents’ retirement intention from their own perspective, being the first to follow this approach using the information provided by the Successful Transgenerational Enterprise Project (STEP) global database. Second, we extend the use of the theory of planned behavior by using the intended age of retirement as an antecedent for the retirement behavior. Third, we change the attention of the succession phenomenon from a normative to a positive approach by exploring both facts and perceptions at the individual and family business level that affect retirement intentions from the incumbent CEO’s point of view. Finally, we offer empirical evidence using the global STEP database on succession and retirement planning in family businesses, which provides a broader perspective and enhances generalizability.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Retirement age and succession in family business

Most family business scholars agree that succession should be planned to be effective (Corona, 2021; Le Breton-Miller, Miller, & Steier, 2004; Sharma & Rao, 2000), but in practice, this does not always happen (Brown & Coverly, 1999; Kirby & Lee, 1996; Mandelbaum, 1994). In family businesses, the incumbent’s inability to “let go” has been cited as the single largest problem in succession (e.g., Sharma et al., 2003; Zahra & Sharma, 2004). Furthermore, the incumbent typically has enough power and legitimacy within the firm and the family to remain in leadership for as long as they desire. Poza and colleagues (1997) find that compared to other family members, incumbent presidents or CEO parents hold significantly more positive views regarding the length of time they will stay in the leadership position.

The family CEO may be ambivalent about their succession. On the one hand, they may understand the benefits of succession planning, but on the other hand, they may feel reluctant to plan their exit. In most cases, an incumbent has a difficult time envisioning life without a significant leadership role in the family business (Kets de Vries, 1985). An incumbent may fear losing status in the family and the community, as both may be closely intertwined with their role in the family business. Moreover, retirement may be perceived as facing mortality. For a founder to plan succession, they must come to grips with retirement, death, and the passing of their professional life. This is not an easy task for anyone, least for an entrepreneur who has guided their life with the strong belief that they control their destiny (Brockhaus, 1982; Gasse, 1982).

2.2. Theory of planned behavior and incumbents’ intended age of retirement

According to the TPB, the probability that a behavior will occur depends on an individual’s intention to engage in that behavior (Ajzen, 1987; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Behavioral intention is defined as “indications of how hard people are willing to try and how much effort they are planning to exert to perform the behavior” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 181). Intention is molded by the individual’s attitudes (Krueger & Carsrud, 1993). These attitudes include the perceived desirability of the outcomes to the initiator, the acceptability of the outcomes according to the social norms of a reference group, and the perception that the behavior will feasibly lead to the desired outcomes. In other words, attitudes develop intention, which leads to behavior (Ajzen, 1987; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Given that TPB predicts the behavior of individuals by observing their intentions, it is no surprise that the main application of the theory in family business research has been at the individual level (Kuiken, 2015). In the family business context, the incumbent leader’s intentions may predict behavior and provide useful information in advance of the succession event that allows timely decisions to be made. Much has been written about the factors (e.g., situational such as family or business conditions and/or individual-emotional) influencing the intention to carry out succession (De Massis et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2003; Zahra & Sharma, 2004) and the actual implementation of the succession process (Giménez & Novo, 2020; Sharma et al., 2003). Using the theory of planned behavior, De Massis et al. (2016) explored situational and individual antecedents of family business incumbents’ attitudes toward intra-family succession. Their study focused on the effect on attitudes as they are the predecessor of intra-family succession intentions but did not measure the effect of these attitudes on intentions or behavior. Ferrari (2023) investigated each factor of the TPB (attitude, desirability, and feasibility) towards business transmission planning involving both generations (incumbent and successor) using a qualitative approach. According to Ferrari (2023), facing business succession implies forming an explicit, future-oriented plan, so TPB is a suitable approach for investigating business succession as a deliberate process. Sharma et al. (2003) is one of the few papers using the theory of planned behavior that considers the succession decision from the incumbent’s perspective. These scholars state that succession is a planned behavior because the incumbent is initiating the succession. They present evidence that behavioral beliefs do not significantly influence succession planning, but social norms and the likelihood that a trustworthy successor is available do have a strong influence on succession planning. Additional research on succession explores the decision of the next generation on whether to enter the family business or not (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003). It is commonly believed that succession is mainly under the control of the incumbent leader of the family business (Lansberg, 1988). These scholars show how the family’s resources, norms, attitudes, and values influence the recognition of entrepreneurial opportunities that can potentially trigger changes in the family. Moreover, recent research highlights how the identity of the incumbent can better explain their emotions, cognition, and behavior to succession (Li et al., 2023; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021). In summary, retirement intentions precede succession planning, which means the incumbent leader of a family business will initiate and control the succession process. The question remains: what factors influence the incumbent’s intention to retire?

3. Hypotheses Development

Literature on strategic leadership states that CEO succession is driven by several organizational and contextual factors, such as organization performance, organizational characteristics, external environment, and characteristics of the incumbent (Cannella et al., 2009). These authors argue that retirement intention is determined by individual factors such as age, education level, health condition, job satisfaction, retirement attitude, and family factors such as marital status and number of dependents. Moreover, CEO age and past achievements are key determinants in predicting retirement (Bilgili et al., 2020). In the case of family businesses, individual characteristics of the incumbent (such as age, gender, generation) and satisfaction with previous succession have been found to affect the propensity for succession planning and the willingness of the incumbent to step aside (Decker et al., 2016), as these factors influence an incumbent’s goal adjustment capacity (Gagne et al., 2011). Incumbent’s identity also plays a role in explaining emotions, cognition, and behavior during succession (Li et al., 2023; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021). This means that incumbent preparation for retirement impacts their expectations about succession.

According to the theory of planned behavior, the desirability of earlier or later retirement, thus succession, is affected by incumbents’ attitudes toward the behavior (retirement age), the social norms under which they will behave, and their perceived behavioral control. Thus, our proposed research model can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1. TPB model of retirement age

3.1. Incumbents’ attitudes

Incumbents’ attitudes toward retirement age are influenced by beliefs about the likely outcomes of retiring at a certain age and the negative or positive evaluation of these outcomes (Ajzen 1985, cited in Kuiken 2015; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). In this paper, we suggest that incumbents’ attitudes towards retirement depend on the following: (i) individual characteristics such as incumbent tenure and age; (ii) the existence of a retirement plan; and (iii) their perception of the need for governance change in the family business.

CEO age and tenure. As the family CEO ages, they may perceive themselves more critically as a guardian of the family interests and business. They may be motivated to stay to protect and grow the company and willing to forgo retirement to ensure appropriate leadership. The strong role of the founder and their legacy has been studied elsewhere (Salazar, 2021). Leaders motivated to retain positions may have self-serving motives to retain institutional power and privileges.

Alternatively, the incumbent may want to retain influence as they identify with the business and resist early retirement because others may lack the deep knowledge and experience to lead successfully. Here, the incumbent is motivated to continue contributing positively by sharing knowledge, experience, and relationships developed over time for the firm’s best interest. Perceived as a positive outcome, postponing retirement intends to strengthen the business and the future well-being of stakeholders. In summary, as the CEOs age, they perceive themselves as guardians, taking more responsibility for the family and business.

It may also be that the CEO is ambivalent toward their succession, unable to envision life without a leadership role in the family business (Kets de Vries, 1985). The CEO may not want to become irrelevant to the family or business. This feeling may also affect the desirability of earlier retirement and generate attitudes toward postponing retirement.

We expect the desirability of continuing contribution, self-serving desire to retain power, and personal fear about post-retirement life to affect retirement intentions. The longer the CEO tenure and older they are, the more likely incumbents will expect to delay retirement. We propose:

Hypothesis 1a. CEO tenure is positively associated with the intended age of retirement.

Hypothesis 1b. CEO age is positively associated with the intended age of retirement.

Existence of CEO retirement plan and perception of a need for change in governance. A CEO with psychological ownership of the firm and leadership role is more interested in a covenant relationship with the organization than power or authority (Hernandez, 2012). For them, personal power is more important than institutional power (Davis et al., 1997). The CEO will intend to retire if they think their capability to maximize financial and socio-economic wealth has diminished. They would retire if they had a retirement plan to maintain an affective commitment, connection, and identity with the business. Similarly, the CEO will retire earlier if they believe a governance change is in the long-term interest of the business family. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2a. The existence of a CEO retirement plan is negatively associated with the intended age of retirement.

Hypothesis 2b. The perceived need for governance change in the family business is negatively associated with the intended age of retirement.

3.2. Perceived family business support (social norms)

Governance existence in family business. A primary objective of governance in a family business is ensuring continuity and viability through generations (Botero et al., 2021). Governance structures and practices help families manage competing family goals and complex systems (Corona, 2021; Suess, 2014; Suess-Reyes, 2016) and prevent or manage conflicts (Ward, 2011).

Corporate governance mechanisms are important because CEO retirement often triggers succession planning. The board oversees CEO performance and plays an essential role in CEO succession decisions like nomination, appointment, and delegation of a suitable successor (Luan et al., 2018). With this responsibility, corporate governance may motivate the CEO to anticipate retirement, as mechanisms ensure performance and nominate a new CEO if they retire (Boeker & Ellstrand, 1996).

Family business mechanisms facilitate cohesiveness and collective goals (Suess, 2014; Suess-Reyes, 2016), allowing harmony and connection with the business if the CEO retires. They can also help manage emotional challenges and facilitate smoother transitions that influence retirement intentions (Umans et al., 2020).

Formal governance articulates rewards and demands of being part of the family business (Botero et al., 2021). In the TPB context, governance is part of the social norms enabling anticipated behavior. Requiring dialogue and succession policies, family and corporate governance enables anticipating retirement. We expect:

Hypothesis 3a. Family governance existence is negatively associated with the intended age of retirement.

Hypothesis 3b. Corporate governance existence is negatively associated with the intended age of retirement.

CEO predecessor age of retirement. Incumbents tend to think and act backward-looking (Zellweger, 2017). Legacy influences incumbent decisions and behavior, and literature suggests incumbent satisfaction with succession depends on the predecessor’s willingness to step aside (Sharma et al., 2003). From a TPB perspective, past behavior influences intentions (Ajzen, 1991). In family businesses, previous behavior explains family effects and intentions, known as intergenerational influence from children’s socialization (Carr & Sequeira, 2007). Information, beliefs, and resources are transmitted through socialization, influencing attitudes, choices, lifestyles, and roles (Carr & Sequeira, 2007). This impacts succession intentions, like parents’ succession preferences relating to successors’ career intentions (Schröder et al., 2011).

Family businesses may select an insider successor with flexible retirement ages compared to nonfamily firms, as succession often involves transitioning to a family member (Luan et al., 2018). This could impact retirement ages to keep the business in the family based on tradition and the predecessor’s retirement age. CEOs focused on family traditions and goals reflect on successful experiences and lessons learned, which can motivate succession and retirement planning to transfer knowledge (Lu et al., 2022). This reflection and desire to transfer knowledge can raise awareness of approaching retirement. Overall, this suggests that if the predecessor retired late, the incumbent tended to repeat that behavior due to intergenerational influence and tradition. We predict incumbents will retire earlier if satisfied with past succession to maintain legacy through resembling previous processes and therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 4. The intended age of retirement is positively associated with the predecessor’s retirement age.

3.3. Successors feasibility (perceived behavioral control)

Successor characteristics. Factors explaining successor readiness in family businesses include age as an indication of leadership readiness (Kelleci et al., 2018). Age reflects knowledge construction (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2018). It represents years of service, improving post-succession performance (Ahrens et al., 2019). In other words, age means the successor understands the firm and has learned stewardship (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2015), giving confidence for earlier retirement.

Having a family successor may also affect the willingness to transfer control. Family control includes influence in ownership, decisions, and leadership. Family culture includes identification, feeling success is shared, personal meaning, and defining status. Family leadership increases in selecting a family successor (Campopiano et al., 2020), who will likely share the incumbent’s identity and guard family interests.

Feasibility and self-efficacy enable planned behavior (Ajzen, 1987; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993). Without believing a course of action will achieve desired ends, few intentionally pursue it. Resolving succession largely depends on a suitable successor (Sharma et al., 2001). Retirement intentions rely on a willing, able, and trusted family member becoming the leader. Successors’ age and family status indicate succession feasibility and control perceptions. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 5a. The intended age of retirement is negatively related to the successor’s age.

Hypothesis 5b. The intended age of retirement is negatively related to a family member successor.

Successor formal preparation process. An incumbent’s willingness to retire depends on perceived successor capabilities, post-retirement plans, and succession planning (Sharma et al., 2001). Preparing the successor is critical (Corona, 2021; Sharma et al., 2003), ensuring appropriate leadership skills for the next phase (Dyck et al., 2002). Moreover, the incumbent’s role as parents seems to influence successor intentions (Lyons et al., 2023). Formal preparation may enable earlier retirement as risks diminish. The existence of formal preparation indicates feasible succession in TPB. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 5c. The intended age of retirement is negatively associated with the existence of formal successor preparation.

4. Methods

To test the hypotheses described above, we used the STEP 2019 Global Family Business Survey. STEP is an international consortium of scholars who seek to understand how family businesses generate new economic activity and increased performance through venturing and renewal across generations. STEP data has been used in previous research on this topic (e.g., Campopiano et al., 2020). The STEP 2019 Global Family Business Survey, developed along with KPMG, attempted to increase the understanding of family business by answering the following questions: How do changed demographics impact family business succession and governance? How are family business leaders planning their personal retirement plans and the company succession plan? What are the differences across cultures?

A total of 1,833 family business leaders from all over the world completed the STEP survey. Data were collected by 48 STEP affiliate universities from different parts of the world with a net 37% response rate. The STEP survey asked respondents to share their views on changing demographics and how they impact the family business governance, succession, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance. Family business leaders responding to the survey spoke eighteen languages and came from thirty-three countries and across five world regions (Europe & Central Asia, North America, Latin America & Caribbean, Asia & Pacific, and Middle East & Africa). An explanation of the operationalization of the variables examined in this study follow.

4.1. Dependent variable

The Dependent variable for this study was the intended retirement age of the CEO. Like previous research (Post et al., 2013), we used respondents’ self-reports of intended retirement age. Specifically, respondents were asked what age they intended to retire.

4.2. Independent variables

The independent variables are from two different groups: the CEO and those related to the family business. The operationalization of the independent variables used to test the hypotheses of this study are explained below.

4.2.1. CEO characteristics

The primary purpose of this research is to examine CEO characteristics explained by TPB that are expected to drive their intended retirement age. We examined CEO age, retirement plans and perceptions in this study. The operationalization of the variables is explained below.

CEO tenure. CEO respondents to our survey were asked to give the length of time they have been CEO in their family business by indicating which of nine categories they fit. Each of the categories were five-year tenure segments, 1-5 years, 6-10 years and so on, up to 41 years and higher.

CEO age. CEOs were asked to give their age by selecting the age category within which they fit. Categories in our research used those in other studies, beginning with 20 years and lower and went 21-30 years, 31-40 years and so on through 81 years and higher.

Existence of a retirement plan. Respondents were asked if they had a retirement plan. If they answered ‘no’ response was coded 0 and if they answered ‘yes’, the response was coded 1.

CEO perceived need for governance change. Respondents were asked if they perceived the need for a change in the existing family business governance to achieve great growth and performance, and/or family harmony. If they answered ‘no’ their response was coded 0 and if they answered ‘yes’, their response was coded 1.

4.2.2. Family business level

There are family business factors that could affect the intended retirement age of CEOs. We examined family business governance, former CEO retirement and future CEO characteristics. The operationalization of each is explained below.

Family governance structures included formal family councils, formal family meetings and family assemblies. The greater the number of these structures the more formal family business structure existed.

Family business policies include the existence of family protocol or constitution, family mission or vision statement, conflict resolution policy, family employment policy and mandatory retirement age for family members. The greater the number of these governance policies the greater the family relies upon formal regulation to manage their business.

Corporate governance structures are mechanisms typically prescribed in the corporate governance literature such as a board of directors or an advisory board and independent directors. The existence of any of these suggests that more formal ‘corporate’ governance structures are being used within the family business.

Corporate policies include formal by-laws, a formal succession mandates, and mandatory retirement age. The existence of any of these indicates that the family business is using corporate governance prescriptions on their policies.

Former CEO retirement age was determined by asking the respondent to indicate which age category s(he)s(he) was in when they retired. In particular, the survey asked: “To the best of your knowledge, at what age did the former CEO leave his/her position?”

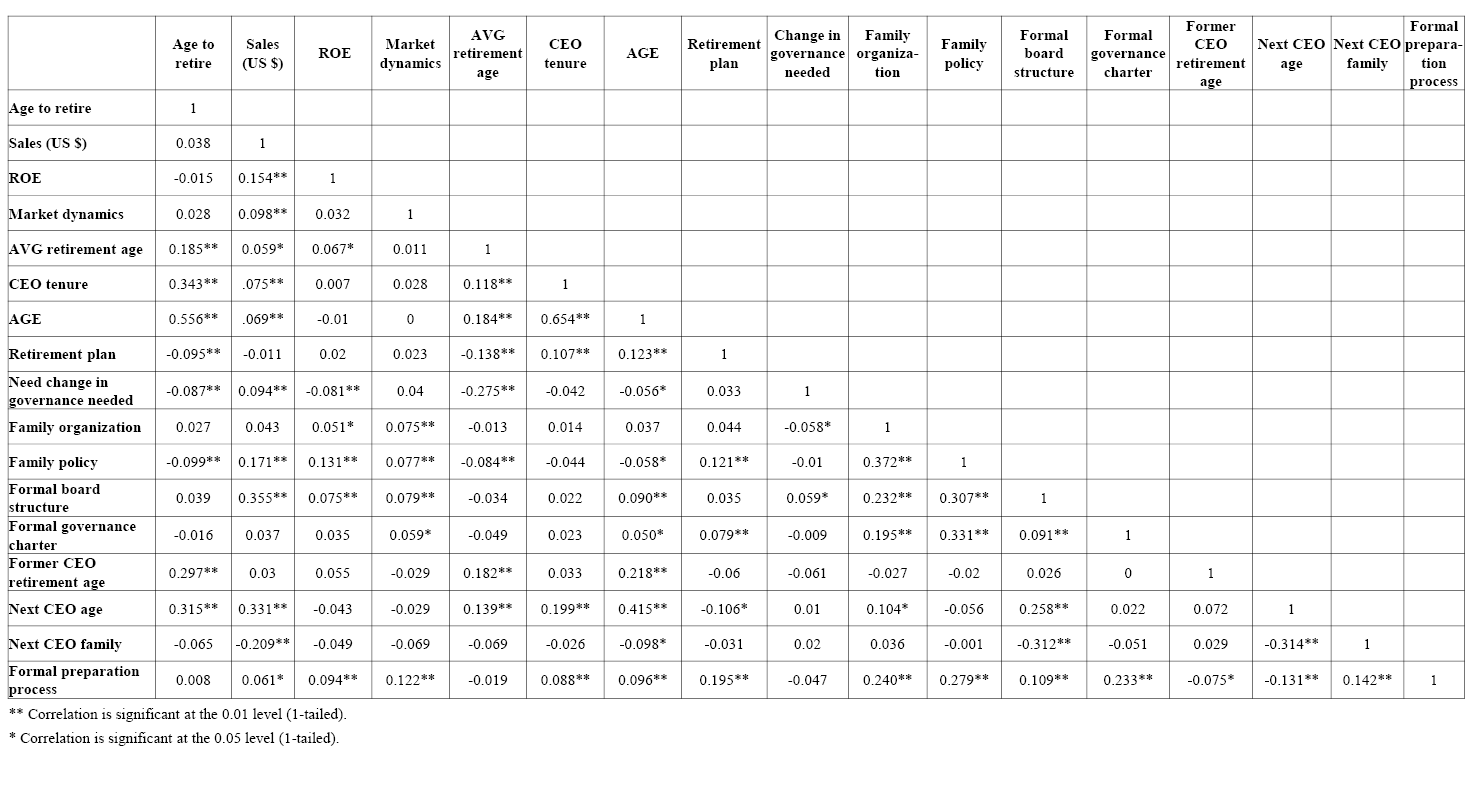

Table 2. Correlation data

The age of the next CEO was asked to determine if the incumbent’s age was a factor in the current CEO’s retirement. In particular, the survey asked: “What is the current age of the identified CEO?”

Next CEO family member. Respondents were asked to indicate if the next CEO is a family member or not. A dichotomous variable was used with ‘0’ indicating the incumbent is not a family member and ‘1’ is a family member.

Formal successor preparation process. Respondents were asked if a formal CEO preparation process existed within their family business. If a formal preparation process existed in the family business, we coded this variable ‘1’ and if not, we coded it ‘0’.

4.2.3. Control variables

This study examines CEO and family business characteristics that explain the CEO’s intended retirement age to determine which has the greatest explanatory power. Previous research has demonstrated that firm size, performance, industry, and country may influence succession in a family business. (e.g., Sharma et al., 2003).

Size. We measured and controlled for firm size by the total annual sales in US dollars.

Firm performance. To control for firm performance, we asked the firm to indicate how their return on equity (ROE) compared to the competition over a three-year period (2016-2017-2018). The subjective measurement of performance became necessary since the family firm in our sample were all closely held and the willingness to report objective data could not be expected (Love et al., 2002). This comparison to similar firms controls for industry effects and has been shown to correlate with objective performance data (Dess & Robinson, 1984; Love et al., 2002; Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1987).

Market dynamics. The market dynamics variable reflects the CEO’s perceptions of the market’s pace of change, the customer’s demand for new products and services, and the volume of product and service variability using a five-point Likert scale.

Country average retirement age. To account for regional and country differences in our sample, we used the average retirement age for countries in our sample (Alonso-Ortiz, 2014). The average country retirement age ranged from 55 in China to 68 years old in the Netherlands and Finland. The mean was 63 years with a standard deviation of 3.3 years.

A summary of all variables can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of variables

|

Variable

|

Type of variable

|

Citation

|

Hypothesis

|

|

CEO intended retirement age

|

Dependent

|

Post et al. (2013)

|

All, H1 to H5

|

|

CEO tenure

|

Independent

|

|

H1a

|

|

CEO age

|

Independent

|

|

H1b

|

|

CEO retirement plan

|

Independent

|

|

H2a

|

|

CEO perceived need for governance change

|

Independent

|

|

H2b

|

|

Family organization

|

Independent

|

Chua et al. (2011)

|

H3a

|

|

Family policy

|

Independent

|

Chua et al. (2011)

|

H3a

|

|

Formal board structure

|

Independent

|

Johnson et al. (1993)

|

H3b

|

|

Formal governance charter

|

Independent

|

Johnson et al. (1993)

|

H3b

|

|

Formal former CEO retirement age

|

Independent

|

|

H4

|

|

Next CEO age

|

Independent

|

|

H5a

|

|

Next CEO family

|

Independent

|

|

H5b

|

|

Formal preparation process

|

Independent

|

|

H5c

|

|

Firm size: Sales

|

Control

|

|

All

|

|

Firm performance: ROE

|

Control

|

Dess & Robinson (1984); Love et al. (2002)

|

All

|

|

Market dynamics

|

Control

|

|

All

|

|

Average country retirement age

|

Control

|

Alonso-Ortiz (2014)

|

All

|

4.3. Method of analysis

Multiple regression analysis using SPSS was used to test the hypotheses outlined above. Control variables entered the equation first, followed by CEO factors and finally family business characteristics. This statistical tool allows the analysis of a single dependent variable and several independent variables. It also allows us to control for variables that might explain the variance in the relationships of interest for this study. The Harman single factor and partial correlations tests found that common method error is not a factor in this research.

5. Results

From the 1,833 family business leaders who completed the survey, we perform our analysis with data from 1,177 family businesses that came from family business CEOs (the focus of our analysis). 81% of respondents were male, and 19% were female. 35% of the sample had four-year college degrees and 30% had master’s degrees. There were 41% first-generation businesses, 40% second-generation, and 19% third-generation or more. Table 2 shows the correlations between all variables. Multicollinearity between independent variables does not appear to be a problem in this sample.

Stepwise multiple regression was used to test the hypotheses of this study. Four control variables entered the analysis first: sales (representing firm size), ROE, market dynamics, and the average retirement age of the respondent’s country of origin. Model 1 in Table 3 shows the results of the testing. Only the average retirement age was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The model explained 4.7% of the variance in CEO intended retirement age.

Table 3. Multiple regression

|

|

Models

|

|

|

Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

|

Dependent variable: CEO intended retirement age

|

Controls

|

CEO

|

Family Business

|

|

(Constant)

|

0.668

|

1.834*

|

- 1.483

|

|

Sales (US $)

|

0.031

|

0.001

|

- 0.051

|

|

ROE

|

- 0.068

|

- 0.028

|

- 0.01

|

|

Market dynamics

|

0.012

|

0.018

|

0.088**

|

|

AVG retirement age

|

0.093***

|

0.024*

|

0.067*

|

|

CEO tenure

|

|

- 0.015

|

0.011

|

|

Age

|

|

0.754***

|

0.521***

|

|

Retirement plan

|

|

- 0.539***

|

- 0.333*

|

|

Need change in governance needed

|

|

- 0.135+

|

- 0.859***

|

|

Family organization

|

|

|

0.062

|

|

Family policy

|

|

|

0.188*

|

|

Formal board structure

|

|

|

- 0.035

|

|

Formal governance charter

|

|

|

- 0.168

|

|

Former CEO retirement age

|

|

|

0.121**

|

|

Next CEO age

|

|

|

0.007

|

|

Next CEO family

|

|

|

0.084

|

|

Formal preparation process

|

|

|

- 0.284+

|

|

|

|

|

|

R-square/Adj R-Square

|

0.037/0.034

|

0.339/0.335

|

0.508/0.459

|

|

*** Correlation is significant at the 0.00 level (1-tailed).

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed).

+ Correlation is significant at the 0.10 level (1-tailed).

|

Incumbents’ attitudes toward retirement. The first set of hypotheses examines the first antecedent in the TPB model of retirement age (Figure 1), the CEO individual level attributes that explain their intended retirement age. The two sets of variables tested in this study are age-related and the CEO’s retirement plans and perceptions. Each group is explained below. Table 3, Model 2 shows the stepwise multiple regression results.

CEO age related. Hypothesis 1a posited that CEO tenure would positively explain intended retirement age. Table 2 shows the correlation between tenure and anticipated age was significant (r = 0.343, p < 0.01); however, the relationship was not significant in the regression with control and other CEO-level variables (Table 3). Hypothesis 1a was not supported.

Hypothesis 1b argued CEO age positively explains intended retirement age. Table 2 shows CEO age and intended retirement age were significantly correlated (r = 0.556, p < 0.01). The regression including controls and individual-level variables supported the hypothesis that CEO age explains intended retirement age (p < 0.001). Hypothesis 1b was supported.

CEO plans and perceptions. Hypothesis 2a argued that a planned CEO retirement predicts a lower intended retirement age. Results show a significantly negative relationship in the correlation (Table 2) and regression (Table 3). This supports that an existing retirement plan is associated with a younger intended retirement age compared to no plan. Follow-up testing revealed CEOs with a plan intended to travel (32%), spend time with family (30%), and advise the business (31%) after retiring.

Hypothesis 2b argued that perceiving a governance change need predicts earlier intended retirement. The variable was in the expected direction, approaching significance (p < 0.10) with CEO-level variables, and was significant in the full model (p < 0.001). The hypothesis was supported, perceiving a governance change need predicts earlier intended retirement.

Three of four CEO characteristics hypothesized to affect anticipated retirement were significant. The CEO-level model explained 34% of variance in intended retirement age. Overall, CEO-level variables explain letting go as hypothesized.

Perceived family business support and successor feasibility. Family business level variables correspond to the second and third antecedents of the TPB model. Perceived family business support is described as governance design and predecessor retirement age. Successor feasibility variables are future CEO characteristics. These are thought to explain the current CEO’s intended retirement age, reviewed below.

Governance design. Hypothesis 3a argued more family governance structures and policies predict earlier CEO retirement. Family structure existence did not explain variance in intended retirement age. Follow-up testing showed 20% of CEOs were also board chairs, 23% directors, 37% owners, and 31% top managers. The structure result fails to support hypothesis 3a.

Greater family policy numbers did predict younger intended retirement, supporting hypothesis 3a for policy. Policies established by the family organization, likely with CEO approval, predict earlier intended retirement. Hypothesis 3b examined whether corporate governance structures and policies affect intended retirement age. While relationships were in the expected direction, neither corporate structures nor policies significantly explained intended retirement age. Hypotheses 3b was not supported.

Former CEO retirement age. Tradition can influence retirement behavior across generations. We hypothesized the previous CEO’s age could positively influence the current CEO’s intended age. The relationship was positive and significant in the full model (Table 3, p < 0.01), supporting that the predecessor’s age influences the current CEO’s intentions. Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Future CEO characteristics. Future CEO characteristics were hypothesized to affect intended retirement age. Hypothesis 5a examined if the successor’s age predicts earlier retirement. While correlated, successor age did not explain retirement in the regression model. The hypothesized effect of successor age was not supported.

Hypothesis 5b proposed a family member successor predicts earlier retirement. While the correlation was negative as expected, it was not significant. The regression was also not significant. Hypothesis 5b was not supported.

Finally, hypothesis 5c argued formal successor preparation enables earlier retirement. The relationship was negative but only approached significance (p < 0.10), below the threshold to support the hypothesis. Hypothesis 5c was not supported.

Only two of eight family business factors were significant – family policy and predecessor retirement age. The full model explained 50.8% (raw) and 45.9% (adjusted) variance. Predecessor age importantly explains additional variance beyond CEO-level factors.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Most prior studies on family business succession examine incumbent behavior during succession (e.g., Sonnenfeld & Spence, 1989), not intentions predicting behavior. However, stronger succession intentions increase the likelihood of actual succession (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Using TPB, we studied factors affecting the incumbent’s intended retirement age as a predictor of actual retirement.

The leader of a tightly held family business has extraordinary power over ‘if’ and ‘when’ they relinquish leadership. Literature does not explain motives behind letting go or staying longer. The CEO may be ambivalent toward succession, making intended retirement age a good measure of letting go willingness. This research investigates drivers of the family CEO’s intended retirement age and their factors affecting retirement. Understanding intended retirement helps researchers and family members gain insight into intentions, motivations, and decision processes, instrumental for promoting long-term success as incumbent decisions significantly impact the business.

Results show both individual and family factors in the TPB model affect intended retirement age, highlighting the prevalence of individual (CEO-level) factors and perceptions over family business factors. These findings confirm the centrality of the incumbent CEO’s role in letting go but do not imply self-serving intentions. The results rebalance factors influencing retirement relative to traditional discussions. Individual factors like CEO age, having a retirement plan, and perceiving a governance change need were significant. Explanations may involve stewardship theory, although we did not test this and suggest it as future research. As CEOs age, they may feel their knowledge, experience, and network remain valuable for success and postpone retirement to strengthen the business and stakeholders’ well-being.

The negative relationships of perceiving a governance change need and having a retirement plan with intended retirement age may involve goal adjustment capacities in succession (Gagne et al., 2011). Perceiving governance change needed, including their own leadership, makes CEOs more willing to step aside. Goal adjustment helps cope with changing conditions and adjust unachievable goals. This behavior aligns with stewardship theory, as CEOs adjust personal goals to preserve family and organizational interests. Essentially, CEOs intend to retire if they feel their capability to maximize wealth has diminished and change is needed. Retirement plans allow maintaining commitment and identity with the business.

Results align with viewing incumbents as backward-looking (Zellweger, 2017). Specifically, the predecessor’s actual retirement age and the incumbent CEO’s age significantly predict retirement intentions, while the successor’s age does not. Other successor factors were also not significant. This suggests the need for more attention to incumbent concerns like finances, status, and identity, preparing the incumbent’s new role should be an explicit succession task. Research should refocus from successors to incumbent and predecessor factors.

We expected governance structures and policies would enable earlier retirement but found support only for family policies, not corporate governance. This seems consistent with the incumbent having enough power and legitimacy that governance bodies do not determine their tenure, viewing CEOs as rational, self-interested actors. However, the lack of evidence for traditional governance structures predicting retirement highlights a stewardship mindset behind CEO intentions, as stewardship governance produces commitment, helping behaviors, and alignment with organizational interests (Davis et al., 1997).

If the family has strong control, we expect later CEO retirement ages, as the powerful, sole decision maker over their tenure anticipates later retirement. Results suggest when firmly in control, leaders intend to retire later.

Gerontocracy in the family business, leaders staying in leadership beyond typical retirement ages, is often viewed negatively because of the increased agency costs associated with strategic stagnation and risk aversion. In this paper, we examine conditions that may lead to gerontocracy and others that do not. Also, we question the negative perception of gerontocracy in the family business (Handler & Kram, 1988; Miller et al., 2004) by explaining the centrality role of the incumbent family CEO in the family business and exploring the psychological factors that affect her/his intentions using the theory of planned behavior. Using a global database on succession and retirement plans in family businesses we offer empirical evidence that supports the prevalence of the incumbent’s perspective on this decision. This result implies that factors leading to gerontocracy rely mainly on the incumbent CEO’s decision, but even if her/his decision turns to gerontocracy, it does not necessarily mean a negative outcome for the business.

6.1. Limitations and future research

This research is not without limitations and several future research avenues are proposed. One of the potential limitations of this work is the concentration of the sample to earlier generations’ family business. In fact, 80% of the sample are firms of either first (founding) or second generation. We think that the assumptions discussed in this paper may better describe the earlier-generation family leaders and opens an avenue of future research to test them with later-generation family business.

The use of global data provides better worldwide context and considered control variables such as market dynamics and the country’s average retirement age to account for country differences. Research may be extended to capture other country/regional distinctive characteristics that can explain differences in retirement intentions. Additionally, we suggest that other variables such as incumbent CEO gender should be studied.

As explained earlier, the age that the former leader retired is significantly related to the anticipated age of retirement for the current leader. If the former leader retired at a certain age, the current leader anticipates doing the same. This suggests that family history and patterns continue to shape the behavior and thinking of leaders in the firm. This begs for additional investigation. How do family legacy and norms affect current family business practices? Legacy and norms have a profound impact for good and bad on family business. This research suggest that they influence succession. Future research is needed to determine other legacy factors and explain how they influence family business. Both theoretical and empirical research is needed.

6.2. Practical implications

The results presented in this paper have important practical implications for family businesses, mainly on the succession planning process. Family and governance conversations in evaluating current governance practices and defining family policies are critical and should clearly include incumbents’ retirement intentions, legacy dimensions, and the role of family CEOs.

The findings indicate that incumbent leaders should reflect on their personal motivations and goals regarding retirement to understand what is driving their intended retirement timing. This self-awareness can help make more intentional retirement decisions, especially regarding issues as the need for governance change and family governance policies.

Family businesses should proactively have discussions with the incumbent leader about their retirement plans and intentions. This can aid succession planning and smooth leadership transitions. Such conversations should promote the creation of family governance that drives agreements between family members by creating policies and a shared vision for the future. This will allow progress to be made in the retirement and succession process and maintain the continuity of the family business since the CEO will perceive that in the face of his retirement there are the necessary conditions for the family to remain united and hopeful for the future.

Formal governance policies established by the family, such as mandatory retirement ages, can encourage incumbent leaders to plan for timely retirement. Implementing these policies can facilitate succession. It is not enough to have corporate governance for retirement to become a reality as it is usually established.

Preparing the incumbent for their transition through retirement planning can enable earlier and smoother retirement. Retirement preparation should be part of the succession process. Moreover, by focusing succession planning on preparing and selecting the successor overlooks incumbent readiness. Attention should be given to factors like the incumbent’s finances, status, identity, and relationships to ease their letting go.

Finally, business families, professionals, and educators must understand that the culture of one’s own family is fundamental in the retirement process. This is reflected in the fact that the history of previous CEOs impacts the future behavior of current CEOs. If the previous CEO retired young, the current CEO will tend to do the same and vice versa. Therefore, practitioners must take this factor into account and facilitate programs in which business families analyze and understand their own history to shape their future.

Ethical statement

The authors confirm that data collection for the research was conducted anonymously and there was no possibility of identifying the participants.

References

Ahrens, J. P., Calabrò, A., Huybrechts, J., & Woywode, M. (2019). The enigma of the family successor–firm performance relationship: a methodological reflection and reconciliation attempt. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(3), 437-474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718816290

Ajzen, I. (1987). Attitudes, traits, and actions: dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 1-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60411-6

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviors. NJ: Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall.

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9

Alonso-Ortiz, J. (2014). Social security and retirement across the OECD. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 47, 300-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2014.07.014

Bilgili, H., Campbell, J. T., O’Leary-Kelly, A., Ellstrand, A. E., & Johnson, J. L. (2020). the final countdown: regulatory focus and the phases of CEO retirement. Academy of Management Review, 45(1), 58-84. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0455

Bommer, W. H., & Ellstrand, A. E. (1996). CEO successor choice, its antecedents and influence on subsequent firm performance: an empirical analysis. Group & Organization Management, 21(1), 105-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601196211006.

Botero, I., Sandoval-Arzaga, F., & Bullock, B. (2021). Understanding governance mechanisms in small and medium family firms in Latin America. Multidisciplinary Business Review, 14(2), 107-120. https://doi.org/10.35692/07183992.14.2.10

Brown, R. B., & Coverly, R. (1999). Succession planning in family businesses: a study of East Anglia, U. K. Journal of Small Business Management, 37(1), 93-97.

Brockhaus, R. H. (1982). The psychology of the entrepreneur. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship. Retrieved at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1497760

Bulut, C., Kahraman, S., Ozeren, E., & Nasir, S. (2019). The nexus of aging in family businesses: decision-making models on preferring a suitable successor. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 34(7), 1257-1269. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-05-2019-0140

Cabrera-Suárez, M. K., García-Almeida, D. J., & De Saá-Pérez, P. (2018). A dynamic network model of the successor’s knowledge construction from the resource- and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 31(2), 178-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518776867

Campopiano, G., Calabrò, A., & Basco, R. (2020). The “most wanted”: the role of family strategic resources and family involvement in CEO succession intention. Family Business Review, 33(3), 284-309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486520927289

Cannella, B., Finkelstein, S., & Hambrick, D. C. (2009). Strategic leadership: theory and research on executives, top management teams, and boards. NY: Strategic Management Series, Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195162073.001.0001

Carr, J. C., & Sequeira, J. M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: a theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of Business Research, 60(10), 1090-1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.016

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., Kellermanns, F., & Wu, Z. (2011). Family involvement and new venture debt financing. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), 472-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.11.002

Corona, J. (2021). Succession in the family business: the great challenge for the family. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 64-70. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12770

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20.

Decker, C., Heinrichs, K., Jaskiewicz, P., & Rau, S. B. (2016). What do we know about succession in family businesses? Mapping current knowledge and unexplored territory. In Kellermanns, F. W., & Hoy, F. (Eds.), The Routledge companion to family business (pp. 45-74). New York, NY: Routledge.

De Massis, A., Sieger, P., Chua, J. H., & Vismara, S. (2016). Incumbents’ attitude toward intrafamily succession: an investigation of its antecedents. Family Business Review, 29(3), 278–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486516656276

Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R. B. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: the case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265-273. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050306

Dyck, B., Mauws, M., Starke, F. A., & Mischke, G. A. (2002). Passing the baton: the importance of sequence, timing, technique, and communication in executive succession. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 143-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00056-2

Ferrari, F. (2023). The postponed succession: an investigation of the obstacles hindering business transmission planning in family firms, Journal of Family Business Management, 13(2), 412-431. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-09-2020-0088

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gagne, M., Wrosch, C., & Brun de Pontet, S. (2011). Retiring from the family business: the role of goal adjustment capacities. Family Business Review, 24(4), 292-304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511410688

Gasse, Y. (1982). Elaborations on the psychology of the entrepreneur. In Kent, C. A., Sexton, D. L., & Vesper, K. H. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 57-71). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Giménez, E. L., & Novo, J. A. (2020). A theory of succession in family firms. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(1), 96-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09646-y

Handler, W. C., & Kram, K. E. (1988). Succession in family firms: the problem of resistance. Family Business Review, 1(4), 361-381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1988.00361.x

Hernandez, M. (2012). Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship. Academy of Management Review, 37(2), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0363

Jenter, D., & Lewellen, K. (2015). CEO preferences and acquisitions. The Journal of Finance, 70(6), 2813-2852. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12283

Johnson, R. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Hitt, M. A. (1993). Board of director involvement in restructuring: the effects of board versus managerial controls and characteristics. Strategic Management Journal, 14(S1), 33-50. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140905

Kelleci, R., Lambrechts, F., Voordeckers, W., & Huybrechts, J. (2018). CEO personality: a different perspective on the nonfamily versus family CEO debate. Family Business Review, 32(1), 31–57.

Kets de Vries, M. (1985). The dark side of entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 63(6), 160-167. https://hbr.org/1985/11/the-dark-side-of-entrepreneurship

Kets de Vries, M. (2003). The retirement syndrome: the psychology of letting go. European Management Journal, 21(6), 707–716.

Kirby, D. A., & Lee, T. J. (1996). Research note: succession management in family firms in Northeast England. Family Business Review, 9(1), 75-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1996.00075.x

Kuiken, A. (2015). Theory of planned behaviour and the family business. In Nordqvist, M., Melin, L., Waldkirch, M., & Kumeto, G. (Eds.), Theoretical perspectives on family businesses (pp. 99-118). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Krueger, N. F., & Carsrud, A. L. (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 5(4), 315-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985629300000020

Lansberg, I. (1988). The succession conspiracy. Family Business Review, 1(2), 119-143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1988.00119.x

Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D., & Steier, L. P. (2004). Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 305–328.

Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2015). Learning stewardship in family firms: for family, by family, across the life cycle. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(3), 386–399. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2014.0131

Lévesque, M., & Minniti, M. (2006). The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 177-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.04.003

Li, W., Wang, Y., & Cao, L. (2023). Identities of the incumbent and the successor in the family business succession: review and prospects. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1062829. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1062829

Long, R. G., & Chrisman, J. J. (2014). Management succession in family business. In Melin, L., Nordqvist, M., & Sharma, P. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of family business (pp. 248-268). London: Sage.

Love. L. G., Priem, R. L., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2002). Explicitly articulated strategy and firm performance under alternative levels of centralization. Journal of Management, 28(5), 611-627. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800503

Lu, F., Kwan, H. K., & Ma, B. (2022). Carry the past into the future: the effects of CEO temporal focus on succession planning in family firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39, 763-804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-020-09748-4

Luan, C. J., Chen, Y. Y., Huang, H. Y., & Wang, K. S. (2018). CEO succession decision in family businesses - A corporate governance perspective. Asia Pacific Management Review, 23(2), 130-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.03.003

Lyons, R., Ahmed, F. U., Clinton, E., O’Gorman, C., & Gillanders, R. (2023). The impact of parental emotional support on the succession intentions of next-generation family business members. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2023.2233460

Mandelbaum, L. (1994). Small business succession: the educational potential. Family Business Review, 7(4), 369-375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1994.00369.x

Marshall, J. P., Sorenson, R., Brigham, K., Wieling, E., Reifman, A., & Wampler, R. S. (2006). The paradox for the family firm CEO: owner age relationship to succession-related processes and plans. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(3), 348–368.

Miller, D., Steier, L., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2003). Lost in time: intergenerational succession, change, and failure in family business. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 513-531. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-9026(03)00058-2

Post, C., Schneer, J. A., Reitman, F., & Ogilvie, D. (2013). Pathways to retirement: a career stage analysis of retirement age expectations. Human Relations, 66(1), 87-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712465657

Poza, E. J., Alfred, T., & Maheshwari, A. (1997). Stakeholder perceptions of culture and management practices in family and family firms - A preliminary report. Family Business Review, 10(2), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1997.00135.x

Radu-Lefebvre, M., Lefebvre, V., Crosina, E., & Hytti, U. (2021). Entrepreneurial identity: a review and research agenda. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(6), 1550-1590. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211013795

Royal Geographical Society (2019). Who wants to live forever? Retrieved at https://www.rgs.org/schools/teaching-resources/who-wants-to-live-forever/why-are-people-living-longer/

Salazar, G. (2022). The archetype of hero in family businesses. European Journal of Family Business, 12(1), 90-95. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v12i1.14630

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., Pablo, A. L., & Chua, J. H. (2001). Determinants of initial satisfaction with the succession process in family firms: a conceptual model. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(3), 17-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870102500302

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., & Chua, J. H. (2003). Succession planning as planned behavior: some empirical results. Family Business Review, 16(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2003.00001.x

Sharma, P., & Rao, A. S. (2000). Successor attributes in Indian and Canadian family firms: a comparative study. Family Business Review, 13(4), 313-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2000.00313

Schröder, E., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., & Arnaud, N. (2011). Career choice intentions of adolescents with a family business background. Family Business Review, 24(4), 305-321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511416977

Sonnenfeld, J. A., & Spence, P. L. (1989). The parting patriarch of a family firm. Family Business Review, 2(4), 355-375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1989.tb00004.x

Suess, J. (2014). Family governance - Literature review and the development of a conceptual model. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(2), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.02.001

Suess-Reyes, J. (2016). Understanding the transgenerational orientation of family businesses: the role of family governance and business family identity. Journal of Business Economics, 87(6), 749–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-016-0835-3

Umans, I., Lybaert, N., Steijvers, T., & Voordeckers, W. (2020). Succession planning in family firms: family governance practices, board of directors, and emotions. Small Business Economics, 54, 189-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0078-5

Venkatraman, N., & Ramanujam, V. (1987). Measurement of business economic performance: an examination of method convergence. Journal of Management, 13(1), 109-122. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638701300109

Ward, J. L. (2011). Keeping the family business healthy: how to plan for continuing growth, profitability, and family leadership. NY: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230116122

Zahra, S. A., & Sharma, P. (2004). Family business research: a strategic reflection. Family Business Review, 17(4), 331-346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00022.x

Zellweger, T. (2017). Managing the family business: theory and practice. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Zhao, H., O’Connor, G., Wu, J., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2021). Age and entrepreneurial career success: a review and a meta-analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(1), 106007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106007