1. Introduction

The importance of family businesses is undeniable since a significant part of the world’s gross domestic product (70 % - 90 %) is produced by family businesses, and they create more than 100 million jobs in the private sector. Also, 85% of business start-ups are financed from family business resources (European Family Business, 2020). The comparison between the performance of family and non-family businesses was studied regarding factors such as return on assets (Family Owned Business Institute, 2021), the profitability of assets and sales (Machek & Hnilica, 2015), structure of assets and agency costs Dyer (2021) with better results for family businesses. On the contrary, family businesses typically have to balance the family and business systems, which are substantially different (Jurova, 2016). To align these two systems, family businesses must create an efficient ownership system (Korab et al., 2008). An integral part of the family business is succession. Succession is a complex and complicated process affected by many external and internal factors (Bracci & Vagnoni, 2011). It is recognised as one of the most critical processes because it determines the further survival of a family business and helps to maintain the balance between the family and business systems. If the family business operations are interrupted, it may lead to loss of wealth or jobs, but it can even destroy the family relationships (Lam, 2009). Many researchers have been working on succession models to eliminate the failures of succession transactions. For instance, Lucky et al. (2011) created one of the first succession models focusing on family business continuity. Further, Bracci and Vagnoni (2011) argued that the succession transaction is not only a change from a predecessor to a successor but also includes tacit knowledge and intellectual capital transactions. Another succession model by Michel and Kammerlander (2015) summarises the succession planning findings and synthesises the four phases of the succession transaction - trigger, preparation, selection, and training. Interestingly, the willingness of potential successors to continue in the family business also increases the willingness to participate in future training (Plana-Farran et al., 2022). One of the new models is the theoretical model using the imprinting theory of nurturing successor willingness (Marques et al., 2022). Hence, we can conclude that succession is a long-term process that requires adequate planning. Succession planning should be initiated from the childhood of a potential successor, where appropriate conditions for developing values, skills and behaviour must be prepared. Moreover, all family members must participate to build trust and good relationships within a family firm (Wasim & Almeida, 2022).

Irrespective of how well the predecessor plans the succession process, its success requires engagement and interest in taking over the family business from the future successor. However, regarding succession intention, the GUESSS reports offer alarming findings. The 2015 GUESSS report showed that 3.5 % of university students wanted to become successors in the family business immediately after graduation, while 4.9 % wanted to be successors five years after school and pointed out a 30 % decrease in students’ interest in taking over parents’ business (Zellweger et al., 2015). Furthermore, the latest GUESSS report from 2021 showed another decrease in succession intention. Only 1.9 % of students wanted to become successors immediately after graduation, and 2.5 % preferred this career choice five years after school (Sieger et al., 2021). The researchers explain this negative trend by the increasing attractiveness of other labour market opportunities, but also by more informed considerations of potential successors. Therefore, even with their lower number, the potential future successors can be better prepared and motivated (Zellweger et al., 2015).

From one side, we see that students’ global interest in becoming successors in family firms is declining. On the other side, succession transaction is one of the most important activities to ensure the survival of the business. However, the previous research is mainly focused on the success of succession transactions. Regarding succession intention, the researchers measure the decrease of potential successors, but suggestions on how to motivate potential successors to become successors are missing. Therefore, the main focus of our paper is to study factors behind succession intention among the young generation to understand future potential successors better. Taking into account previous research, we decided to examine the role of working experience using human capital theory (Becker, 1994) and the role of ownership stake based on agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), due to the lack of literature with this concern, especially in East Central Europe. Next, we focus on birth order in pursuance of birth order theory and on the role of sex. Few researchers use GUESSS data in these areas, and former research findings brought many discrepancies, as even the theories employed opposed each other. We closer look at the great man theory (Carlyle, 1840), misfit theory (Hofstede et al., 2004) and push-pull factors theory (Kirkwood, 2009). These theories are not often used when examining the field of family businesses. Thus, they deserve closer examination and could help to understand the offspring’s motivations to become successors in the future.

As for the specific context of Slovakia, with only around three decades of free market economy, the experience of Slovak family businesses with succession is relatively low, while this issue gradually gains importance as more and more family businesses are maturing towards the first generational transition. This is not only the case in Slovakia but, in fact, in most of its fellow former Eastern-bloc countries. Accordingly, the body of knowledge on family business succession in the region is still emerging, which underlines the need for our study. Exploring the succession intention in the Slovak environment can help better prepare for the coming generational transitions and understand potential successors’ motivations, resulting in a positively developing business environment.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we revise the literature on the selected potential factors to explain the theoretical rationale alongside the findings of former related research.

2.1. Working for parents’ business

Previous personal experience working for parents’ businesses is studied for its effect on their offspring’s career choices, especially as not all entrepreneurs tend to engage their children in working for their firms (e.g., Tabares & Cano, 2018). When working for parents’ businesses, children naturally adopt their parents’ behaviour, norms and values. The parent becomes a role model to whom they want to be similar in future (Carr & Sequeira, 2007). However, the impact of closely observing parent entrepreneurs at work on offspring succession decisions might not always be positive. In some cases, observing the reality of being an entrepreneur, which includes frequent obstacles, problems with various stakeholders, personal sacrifice, and risks, might have the opposite effect (Zhang et al., 2014). The perception of offspring’s work by family business employees is important, too. Knowing the future successor is crucial not only within the family but also among the professionals and employees working in the family firm. They should meet and know the future successor, and thus, their work in the firm to be taken over is important (Corona, 2021). Moreover, the active involvement of a potential successor can help build a reputation and recognition as a potential future leader of the family business (Kallmuenzer et al., 2022). However, one of the biggest mistakes is when parents let the offspring choose the position to work on and give them an unlimited space for realisation, especially when they lack the required knowledge or qualification. This leads to a negative perception of the offspring’s work in the family business and decreases the satisfaction of other employees (Andrejcakova, 2022).

As for the working experience as a potential driver of succession intention, Cieślik and Van Stel (2017) found out that young people from family business environments who have been working for their parents’ businesses are more likely to become successors than independent entrepreneurs in the future. Hence, the family business is an incubator affecting the career choice decision between an entrepreneur and a successor (Fairlie & Robb, 2007). Further, working in their parents’ company could help descendants to learn about business and, based on such experience, they are better prepared to make good decisions as future successors. In fact, decision-making will be one of the most crucial tasks in their potential future owner-manager roles, so such a working experience is indispensable (Danihel, 2022). However, some authors argue that it is important to differentiate between the types of work which an offspring performs in the family business, which typically relates to their age and education (Ashraf et al., 2019). According to human capital theory, a person can build own capital due to education and experience. In some situations, experience is a more powerful learning tool than education. Human capital attributed to experience can be crucial for entrepreneurial success (Becker, 1994). In the context of succession, previous working experience in family business can increase descendants’ motivation to become successors. Therefore, we propose a hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). There is a positive relationship between students’ work experience in the family business and their succession intention.

2.2. The role of birth order

From a family perspective, choosing the successor is based on the cultural norms which are differentiated from country to country. The factors linked with family relationships, such as birth order, blood relations or sex, are more likely to be influenced by cultural norms. These factors have an impact on the early phases of the succession process (Daspit et al., 2016). However, more and more family businesses try to eliminate the influence of cultural norms, including birth order.

From a potential successor perspective, there are four categories of motives that Sharma and Irving (2005) called commitments. First is the affective commitment, which is based on personal desirability. Second is the normative commitment, which is based on the perceived duty. Third is the calculated commitment, which is based on perceived opportunity cost, and fourth is the imperative commitment, based on the perceived need of the family business. The relationship between the birth order and the succession intention is related especially to normative commitment. This is why the firstborn children (especially sons) are more likely inclined to the successor role in a family business. We see some similarities with birth order theory (Robinson & Hunt, 1992), which explains that the birth order of children can lead to different personality traits, different behaviours and different experiences. First-born children can receive more attention from their parents but also experience more pressure to succeed or to follow their path. Regarding different behaviours among siblings, Sulloway (2001) studied the relationship between the birth order and the personal development of offspring. The study showed personal differences between first-born and later-born children, mainly because of different interpretations of childhood memories. The firstborn children may be motivated to succeed by playing by the rules dictated by the parents, while the later-born children tend to fight against their parents’ rules. They try to modify the rules against the firstborn child because they want to show that they are unconventional and risk-tolerant. Therefore, the firstborn successors may become the leaders who follow the parents’ model business. However, the later-born successor may become innovative leaders, which can lead to new opportunities but risks as well (Nicholson, 2008).

The rivalry among siblings occurs in the succession process quite frequently. It appears especially when the selection process is omitted, and the successor is chosen in advance. The conflict among siblings escalates when one of them is preferred. Therefore, it is crucial to make the selection process among descendants. Thanks to the selection process, conflicts and rivalry among siblings are eliminated. Moreover, the decision about the future successor is more accepted by employees when the choice is made according to a certain approach (Filser et al., 2013). A completely different approach to forming a family business succession can be based on the shared leadership principle, where there is not only one successor but a team of siblings who share the role of successor (Cisneros et al., 2022).

The role of birth order in family business succession has already been studied in family business research. For example, Aldamiz-Echevarria et al. (2017) found out that successor choice in family businesses is influenced by the birth order, then the experience and skills often linked with age and the level of compatibility with family expectations. Furthermore, they argue that the birth order plays a greater role when the successor is a son. As they explain, this is caused not only by parents’ decisions but also because many women decide to leave the family business. A similar finding was provided by Cavicchioli et al. (2018), who examined the succession intention of a sample of Italian farmers, concluding that the highest succession intention was shown by their firstborn sons. On the other hand, Schlepphorst and Moog (2014) claimed that the major factor affecting the choice of the potential successor is personality, which was found to be more important than sex or birth order. Based on previous research, we propose a hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). There is a significant relationship between birth order and succession intention.

2.3. The role of sex

Zellweger et al. (2015) identified a lower succession intention among daughters than among sons. Of course, this relationship changes from country to country. The biggest sex gap in succession intention was found in France, Columbia and Canada. On the contrary, higher succession intention among daughters than among sons was discovered in Germany, Finland, Malaysia and Lichtenstein. Many factors are considered when trying to explain the sex gap in family business succession. Traditionally, it is explained by social roles defined according to sex. For example, Hofstede’s masculinity dimension describes the impact of the masculinity level on society. The higher the masculinity is in the country, the bigger the sex gap in terms of succession intention in the country (Hofstede, 2001). Further, Belda and Cabrer-Borrasa (2018) found that women from South Europe are motivated to become successors when they acknowledge university education, and the family business compiles a succession plan. Also, daughters see many positives in a successor role, such as a pride to continue in the family business, comfort in the workplace, shared family values, more time spent with family or flexible working time (Vera & Dean, 2005).

Further, the sex of parents also impacts the career choices of male and female offspring. As there are typically more male than female entrepreneurs, the sons have more opportunities to observe fathers’ work in business (Shinnar et al., 2018). While daughters can be inspired by their fathers’ work too, the influence of mothers’ work was found to be stronger. Similarly, sons are more influenced by the work of their fathers than mothers (Hoffmann et al., 2015). Furthermore, as fathers often encounter challenges in managing their family roles and business ownership, they tend to spare daughters from family businesses (Vera & Dean, 2005). When it comes to a succession process, fathers hesitate to include daughters in everyday business matters or allow them to monitor the business processes (Glover, 2014). Despite the fathers’ hesitation to include daughters in family business operations, the daughters can value the fathers’ work more than sons. However, this is still insufficient to consider the successor career path (Humphreys, 2013). In fact, young men whose parents are entrepreneurs are almost twice as likely to pursue an entrepreneurial career than young women with parents entrepreneurs (Bloemen-Bekx et al., 2019).

Finally, the successor’s sex also seems related to other factors influencing succession intention. First, as for the birth order, as we already mentioned above, the firstborn sons are most often chosen as the successors. Interestingly, when descendants do not have any siblings, the difference between daughters’ and sons’ succession intentions is lower (Zellweger et al., 2015). Further, Ahmed et al. (2021) studied the influence of several factors on succession intention in an early phase of career choices or even before the career. Their results indicate that parents’ support and working experience in parents’ businesses have a moderate positive impact on succession intention among daughters. Next, the role of parents and the influence of social groups also show a moderate positive impact. And finally, working for parents’ businesses strongly predicted succession intention in countries with a lower sex gap (Ahmed et al., 2021).

Regarding theories, no theory confirms that men are better entrepreneurs/successors than women, except the great man theory (Carlyle, 1840). However, the great man theory is highly criticised, as it suggests that the role of leader, manager or someone in charge with power (in our case future owner of a family business) requires characteristics such as charisma and excellent rhetoric skills, and it considers a man to be born as a great leader who is more likely to possess these characteristics compared to women. Contrarywise, the misfit theory (Hofstede et al., 2004) explains that the people who do not see fairness in working conditions in the labour market become entrepreneurs (or successors). This can involve women, immigrants or different minorities. Finally, the push-pull factors theory (Kirkwood, 2009) examines that more important than sex is the right motivation for men and women. This means that both men and women can be entrepreneurs or successors when they are motivated properly. Based on the literature review, therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). There is a significant relationship between sex and succession intention.

2.4. The personal ownership stake in the family business

Only a few studies examined the relationship between succession intention and personal ownership stake in family businesses. The study of Sharma et al. (2001) found out a positive relationship between expected payable dividends and the tendency of successors to continue in the family business. The more dividend is paid, the higher the succession intention. A similar study examined the impact of the ownership stake on the managers, confirming that the greater ownership stake of family managers is positively related to improved performance, measured by ROA (return on assets). The authors argue that managers are aware that higher performance will be rewarded by higher financial compensation (Amran & Ahmad, 2010). On the other hand, the role of ownership stake might be also influenced by the cultural context. For example, in China, all descendants typically inherit the same ownership stake, irrespective of their sex or age, to ensure continuity in their involvement in the family business. Moreover, equal ownership stakes eliminate sibling rivalry and increase the chosen successor’s acceptance. In this context, the ownership stake does not influence the succession intention, because the stakes among all siblings are the same (Yan & Sorenson, 2006).

In family business literature, the ownership stake is often studied for its influence on the organisation and performance of family businesses. For example, the F-PEC model (P - Power, E – Experience, C – Culture) emphasises the role of power as a significant factor. The power is based on the proportion of shares owned by the family, the number of managers from among family members, and the number of members of the Board of Directors belonging to the family (Astrachan et al., 2002). Further, the ownership issue is often related to the agency theory, which is used when the interests of business owners and managers–agents differ (Fama & Jensen, 1983). These differences are solved by offering the ownership stakes in family businesses to agents. Also, agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) states that managers’ interest is improved when they get a stake in a business. Moreover, there is a positive relationship between the managers’ ownership stake and the company’s future revenues (Nyberg et al., 2010). Thus, we can assume that when children get an ownership stake in a family business it can lead to higher interest in this business and, in turn, that can lead to a higher succession intention. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The offspring with personal ownership stake in the family business have higher succession intention than those with no ownership stake.

3. Research Methodology

Our analysis is based on the GUESSS (Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students´ Survey) project data collected in 2021 from the population of students at universities in Slovakia. The GUESSS 2021 Slovak sample comprised 5,754 students, 1,819 of them (31.6%) having parents entrepreneurs (either one of the parents being self-employed or majority owner of a business). Among these, 575 considered their parents’ business as a family business, thus representing the main sample of our study. This sample comprised 386 female and 188 male students (one respondent did not indicate their sex) with a mean age of 22.97 years.

The dependent variable of our analysis is succession intention. The respondents were instructed to indicate their level of agreement on a Likert-type scale from 1 (fully disagree) to 7 (fully agree) with the following statements:

— I am ready to do anything to take over my parents’ business.

— My professional goal is to become a successor in my parents’ business.

— I will make every effort to become a successor in my parents’ business.

— I am determined to become a successor in my parents’ business in the future.

— I have very seriously thought of taking over my parents’ business.

— I have a strong intention to become a successor in my parents’ business one day.

The statements are derived from the entrepreneurial intention questionnaire developed by Liñan and Chen (2009), while the items were modified to refer to the respondents’ succession intention in the business run by their parents. To determine the value of the succession intention, we used the average score of the six items listed above. These items exhibited a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.978, reflecting high internal consistency. To bolster the robustness of our analysis, we also employed composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) as indicators of the latent construct’s internal consistency and convergent validity. Notably, our results yielded a CR value of 0.983 and an AVE value of 0.919, both of which are exceptionally high, affirming the remarkable reliability of the indicators used to assess our latent construct. These findings underscore that the observed variables offer a consistently accurate representation of the underlying construct.

The independent variables in our research are:

— Working experience in parents’ business: respondents indicated whether they have been working for their parents’ business (yes = 1, no = 0).

— Birth order: recalculated from the respondents’ answer to the item ‘How many older siblings do you have?’. When respondents answered ‘zero’, they were considered as a firstborn child (firstborn = 1, otherwise 0).

— Sex: respondents were asked to indicate their sex (male = 0, female = 1, other = 2).

— Ownership stake: respondents indicated whether they have a personal ownership stake in their parents’ business (yes = 1, no = 0).

We used the Mann-Whitney U test and the Multiple Linear Regression to analyse the relationship between the selected factors and the succession intention. In particular, the nonparametric independent samples Mann-Whitney U Test was used to compare two types of variables: dichotomic (variable with two values - two populations, for example, populations of students working in their parent’s business, and those not working in their parent’s business) or ordinal variable which does not have the normal distribution. The null hypothesis is formulated formally. The hypotheses that we formulated are the alternative hypotheses (H1). Therefore, when rejecting the null hypothesis, we confirm the statistical significance of the assumed relationship (Bolekova et al., 2017). Multiple Linear Regression was used to examine the relationship between the dependent variable – succession intention, and a group of independent variables – sex, birth order, working in parents’ business and personal ownership stake in parents’ business. The analysis identified how the group of independent variables influences the dependent variable. In our analysis, we have employed IBM SPSS v.25 statistical package for hypothesis testing, MS Excel for the presentation of data in graphs and tables, and Wolfram Mathematica for calculating the relationship of Multiple Linear Regression.

4. Results

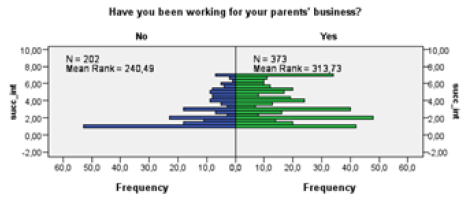

Based on the Mann-Whitney U test results, we reject the formal null hypothesis and confirm hypothesis 1 that a positive relationship exists between students’ work experience in the family business and their succession intention. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of responses. The left side presents the responses of students who have not been working in their parents’ businesses (202 students from our sample), while the right side displays those with work experience in their family businesses (373 students). The mean rank shows a level of succession intention. The higher the mean rank value, the higher the succession intention. Thus, the students who have been working in their parents’ businesses show higher succession intention (313.73) compared to their counterparts with no such involvement in their family firm (240.49).

Figure 1. Mann-Whitney U Test H1

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

Table 1. Mann-Whitney U Test H1

|

Total N

|

575

|

|

Mann-Whitney U

|

47 269.500

|

|

Wilcoxon W

|

117 020.500

|

|

Asymptotic Sig. (2-sided test)

|

0.000

|

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

Table 1 shows the value of testing criteria (U=47 269.5) and the two-sided significance (p < 0.001), which is two-sided because H1 is two-sided as well. The relationship is significant when the p-value is smaller than alfa (in this scenario alfa = 0.05). Therefore, the test results confirmed that the succession intention is significantly higher among the students who have been working in their parents’ businesses.

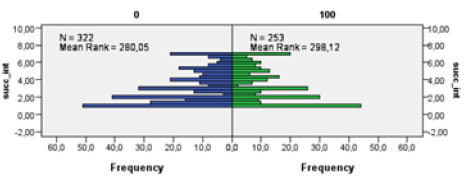

Mann-Whitney U Test did not confirm the statistical significance of the relationship between the birth order and the succession intention (U = 43 293; p = 0.194) (Figure 2 and Table 2). Therefore, H2 was rejected. Thus, surprisingly, among Slovak students, the succession intention is higher among the later-born descendants (298.12) than among the first-born descendants (280.05). However, as the p-value (p = 0.194) is bigger than alfa (0.05), this relationship is only on a level of coincidence. Our sample consisted of 322 students born as a first child and 253 students born after their oldest sibling.

Figure 2. Mann-Whitney U Test H2

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

Table 2. Mann-Whitney U Test H2

|

Total N

|

575

|

|

Mann-Whitney U

|

43 293.000

|

|

Wilcoxon W

|

75 424.000

|

|

Asymptotic Sig. (2-sided test)

|

0.194

|

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

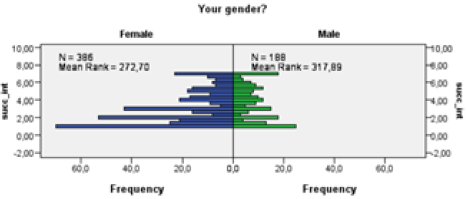

Results showed a significant relationship between sex and succession intention. Mann-Whitney U Test confirmed a statistically significant difference between sons and daughters (U = 30 571.000; p = 0.002). In Figure 3, we can see that our sample comprised 386 daughters and 188 sons. The mean rank of succession intention was found to be higher among sons (317.89) than among daughters (270.70).

Figure 3. Mann-Whitney U Test H3

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

Table 3. Mann-Whitney U Test H3

|

Total N

|

574

|

|

Mann-Whitney U

|

30 571.000

|

|

Wilcoxon W

|

105 262.000

|

|

Asymptotic Sig. (2-sided test)

|

0.002

|

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

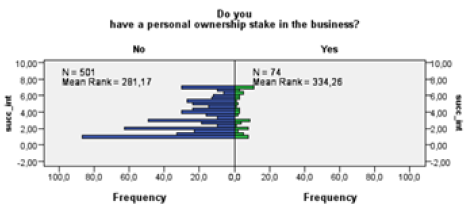

We tested the level of succession intention among students who have a personal ownership stake in the family business (74 students) and those who do not have a personal ownership stake in the family business (501 students). The Mann-Whitney U Test indicated that the difference was significant between the compared groups. The students with a personal ownership stake in family business exhibited a higher mean rank of succession intention (334.26) than those without an ownership stake (281.17). Based on this finding we confirm the H4 (U = 21 960; p = 0.010).

Figure 4. Mann-Whitney U Test H4

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

Table 4. Mann-Whitney U Test H4

|

Total N

|

575

|

|

Mann-Whitney U

|

21 960.000

|

|

Wilcoxon W

|

24 735.000

|

|

Asymptotic Sig. (2-sided test)

|

0.010

|

Source: Own elaboration based on GUESSS 2021 data

Further, we used regression analysis in order to address how sex, birth order, working experience and ownership stake in parents’ businesses influence the succession intention in family businesses. We performed an ANOVA test over the group of independent variables, i.e., sex, birth order, working in parents’ business and ownership stake. The results of the regression analysis are demonstrated in Table 5.

Table 5. Regression analysis results

|

|

F value

|

df

|

Sig

|

|

Sex

|

6.1331

|

1

|

0.014*

|

|

First-born

|

1.3001

|

1

|

0.255

|

|

Working in parents' business

|

19.2694

|

1

|

0.000***

|

|

Ownership stake

|

8.5252

|

1

|

0.004**

|

Source: Test in Wolfram Mathematica based on GUESSS data 2021

Before we analyse the results, we discuss the potential multicollinearity of our data, which was analysed through the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The outcome of the test is shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Variance inflation factor

|

Sex

|

First-born

|

Working in parents' business

|

Ownership stake

|

|

1.001

|

1.010

|

1.020

|

1.016

|

Source: Test in Wolfram Mathematica based on GUESSS data 2021

The level of VIF is low so no major multicollinearity in data is present. Our results show a significant influence in the case of all independent variables except the ‘first-born’ variable. It means that first-born offspring in our sample do not exhibit higher succession intention. This result is in line with the result of testing hypothesis H2. The sex shows moderate significance (as the p-value is less than 0.05), while the ownership stake shows strong significance (the p-value is less than 0.01) and working experience in parents’ business shows the strongest significance among the independent variables (the p-value is less than 0.001). The value of the determination coefficient (Rsq = 0,0637) shows that almost 7% of the variance in succession intention could be explained by this relationship. Specifically, in the case of 7% of the students considering their parents’ business as a family business, the succession intention is influenced by sex, working in parents’ business and by ownership stake.

5. Discussion

This paper aimed to examine the influence of sex, birth order, ownership stake and working experience in parents’ businesses on succession intention among Slovak students who consider their parents’ business as a family business. The paper offers a better understanding of succession intention, which shows an overall decreasing tendency over the last few years. Based on the Mann-Whitney U Test results, we tested the relationship between succession intention and particular independent variables, which we describe below. Further, we compare the strength of the relationship between the succession intention and the examined variables (sex, birth order, working experience in parents’ business and ownership stake influence) in linear regression analysis. Our findings suggest that working in parents’ businesses has the most significant impact on succession intention, followed by having a personal ownership stake in parents’ businesses. The descendant’s sex shows a medium significance in relation to the succession intention. Finally, the birth order was found to have no significant influence.

We hypothesised a positive relationship between working involvement and succession intention based on previous research (Carr & Sequeira, 2007; Cieślik and Van Stel, 2017) and human capital theory (Becker, 1994), which was confirmed. We can conclude that successors build their capital through working experience in family business. Working experience can eliminate the fear of the future, help to build relationships with business networks (Corona, 2021) and help to build a reputation in family business advance (Kallmuenzer et al., 2022).

Surprisingly, our findings do not confirm the significant relationship between birth order and succession intention. The majority of literature indicates that the succession intention of first-born children is higher compared to their siblings who were born later (Aldamiz-Echevarría et al., 2017; Cavicchioli et al.., 2018; Schenkel et al., 2016). Still, the former evidence remains ambiguous, as certain studies argue that the birth order does not have an impact on succession intention, or that the succession intention between first-born and later-born children differs only right after studies but remains similar in the longer term (Holienka et.al., 2019). The absence of a significant relationship in our results could be explained by relatively lower levels of normative commitments among the first-born offspring. The normative commitments are based on social expectations, which, according to Sharma and Irving (2005) explain why the first-born children could have higher succession intentions compared to their later-born siblings. However, it seems that the current generation of first-born successors might not consider social expectations as a strong enough factor to determine their succession aspirations. Referring to birth order theory (Robinson & Hunt, 1992), it seems that Slovak first-born children do not want to follow the same career path as their parents or are interested in their own decisions despite the potential conflict with parents.

Next, our results propose that male offspring exhibit significantly higher succession intention in family businesses compared to their female counterparts. This sex gap has already been identified by several studies (Hoffmann et al., 2015; Holienka et al., 2019; Shinnar et al., 2018; Zellweger et al., 2015), so our findings further add to its validity. Regarding the theories concerned, we see the best fit with our findings with the push-pull factors theory (Kirkwood, 2009), where the appropriate motivators are more important than the sex factor. Finding the right motivators can improve succession intention among both sons and daughters, reducing the sex gap.

Further, we confirmed that the students with personal ownership stakes in family businesses have higher succession intentions. So far, only a few studies have been dedicated to studying the influence of this factor (Sharma et al., 2001; Yan & Sorenson, 2006). Following the agency theory (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen & Meckling, 1976), we can compare situations when managers are motivated by the ownership stake in the companies they manage and when potential successors can be motivated by ownership stake to become future successors of the family business.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The theoretical implications of our study lie especially in demonstrating the application of the considered theories in the context of potential family business successors in Slovakia. By doing so, we demonstrate their validity in this specific context to address the expected relationships therein with further research. In particular, the results on the relationship between the work experience in family business and succession intention are in line with the human capital theory (as developing the relevant human capital through working experience could contribute to fostering offspring’s interest in succession) and the imprinting theory (as the work experience might represent one of the channels to imprint the family business-related values and beliefs). Regarding ownership stake and succession intention, our findings agreed with the agency theory, as the ownership stake can increase overall interest in business and the higher interest can lead to a higher probability of becoming a successor. On the other hand, we see also contradictions between theories and our findings. While the birth order theory explains that firstborn children tend to become successors more often than later-born children, mainly because of their subconscious effort to please their parents’ expectations, our findings show that the current generation of potential successors might not perceive the parents’ expectations as a significant factor to form their succession intention. When it comes to the relationship between sex and succession intention, results show higher succession intention among sons than among daughters. This can mean that women perceive many opportunities in the labour market and do not consider themselves disadvantaged, as the misfit theory may propose. More working opportunities might decrease entrepreneurial and succession intention. In line with the practical implication presented below and in the context of all our findings, we see the best fit with push-pull theory, where more important than sex is the right motivation of successors.

5.2. Practical implications

Based on the results from our study, we come with the following practical implications. Firstly, working in the parents’ business allows potential successors to understand the business processes and the industry, but also to meet the employees working in the family firm. The working experience also gives one a better view of the successor’s future role in the business and enables their better preparation for the role. Involvement in a family business can help build confidence that potential successors possess the required skills and knowledge in order to run the family business.

Secondly, based on our findings, we recommend parents to incentivise the succession intention among potential successors by giving them a personal ownership stake in the family firm. Owning a stake in the family business enables one to feel like a part of it, and team members typically want to contribute to the best possible performance of the business. Moreover, thanks to their ownership stake, the descendants could feel motivated to cooperate in business activities.

Thirdly, the recommendations on how to eliminate the sex gap and encourage young women to take the role of potential successors involve mainly the domain of education and training. More particular, they shall contribute to building self-confidence among family business owners’ daughters that they have sufficient skills and knowledge to manage the role of a successor. Moreover, the existence of a succession plan in parents’ business increases the succession intention among daughters. Former research already indicated that in countries with higher education levels and companies with an established succession plan, the sex gaps in succession intention are lower (Belda & Cabrer-Borrása, 2018). It would also be beneficial if all children, no matter the sex, had a chance to work in their families’ businesses. Further, it is necessary to eliminate the stereotyping of the social roles of men and women (Zellweger et al., 2015) in relation to entrepreneurship and beyond. Last but not least, we recommend parents offer equal opportunities to daughters and sons, as they are often inclined to subconsciously save the daughters from the demanding life of running a family business (Vera & Dean, 2005).

5.3. Limitations

Our research is not exempt from limitations. The main limitation lies in the cross-sectional nature of the data and the subjectivity of respondents’ indication of their succession intention. Also, the respondents could tend to choose the medium value in the case of the items measured on a scale. However, the sample was sufficient in size and reliability in order to respond to these limitations. Next, the geographical area can also be seen as a limitation because Slovak students’ research sample has certain specific, which can differ from other geographic areas. Therefore, the extent to which the findings can be generalized is limited, and replication of this study is encouraged in other countries and regions.

5.4. Future research

Finally, our study also raises several implications for future research. While the succession intention is a frequently discussed topic in academic literature and family business practice, there are still areas that require further examination. For example, researchers have not yet dedicated sufficient attention to the study of the relationship between the ownership stake and succession intention in detail. As our results propose that this factor plays a significant role, this area deserves a closer look. Also, as we have indicated the significant role of work experience in the parent’s business, we encourage further research to examine with closer attention the mechanisms of interactions between the parent, the offspring, the aspects of the company and the character of this work engagement, in terms of their relation to the family business succession intention. Furthermore, in response to the decreasing interest among the young generation to take over the family business, we assume that the future research shall also address the factors negatively influencing these interests as well as the “dark side” of family business succession and the related coping strategies. Overall, we also anticipate that the area of succession intention research will remain a highly debated topic in the former Eastern-bloc countries, particularly due to the upcoming wave of necessary succession transactions among the family businesses with aging generation of founders.

6. Conclusion

We can conclude that working in parents’ businesses, a personal ownership stake in parents’ businesses and sex significantly impact succession intention, unlike birth order, which was not found to significantly influence succession intention. However, the factors differ in their intensity. The most significant factor in our study is the working experience in parents’ businesses. The ownership stake shows strong significance, while sex shows moderate significance. Based on the results we suggest that family business owners involve their children in family businesses, so descendants can feel more prepared for future roles as successors. Then, giving a potential successor personal ownership stake in the family business can improve their overall interest in their parents’ businesses and increase their motivation to become successors in future.

Ethical statemet

The authors confirm that data collection for the research was conducted anonymously and there was no possibility of identiying the participants.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the Contract no. APVV-19-0581. This paper is based on data from the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey - GUESSS. Comenius University Bratislava, Faculty of Management is the national GUESSS coordinator in Slovakia.

Author Contributions

Diana Suchankova: literature research, writing – original draft. Marian Holienka: supervision, data collection, hypotheses testing, writing – review & editing. Peter Pšenák: regression analysis, methodology research.

References

Ahmed, F. U., O’Gorman, C., Lyons, R., & Clinton, E. (2021). Exploring the role of national gender inequality in female family business succession intentions. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1, 13906. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2021.103

Aldamiz-Echevarría, C., Idígoras, I., & Vicente-Molina, M. A. (2017). Gender issues related to choosing the successor in the family business. European Journal of Family Business, 7(1-2), 54-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejfb.2017.10.002

Amran, N. A., & Ahmad, A. C. (2010). Family succession and firm performance among Malaysian companies. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 1(2), 193-203. Retrieved from https://lnk.sk/uxb7

Andrejčáková, E. (2022). Generačné konflikty v rodinných firmách sú časté, biznis môže rodinu zničiť. Index.sme.sk, January 5th. Retrieved from https://index.sme.sk/c/22801594/erika-matwij-ako-si-ma-majitel-firmy-vybrat-nastupcu-z-rodiny.html?ref=tab

Ashraf, S. F., Li, C., Butt, R. S., Naz, S., & Zafar, Z. (2019). Education as moderator: integrative effect towards succession planning process of small family businesses. Pacific Business Review International, 11(12), 107-123. Retrieved from http://www.pbr.co.in/2019/2019_month/June/10.pdf

Astrachan, J. H., Klein, S. B., & Smyrnios, K. X. (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem1. Family Business Review, 15(1), 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2002.00045.x

Becker, G. S. (1994). Human capital revisited. In Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education (3rd Edition) (pp. 15-28). The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11229

Belda, P. R., & Cabrer-Borrás, B. (2018). Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs: Survival factors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14, 249-264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0504-9

Bloemen-Bekx, M., Voordeckers, W., Remery, C., & Schippers, J. (2019). Following in parental footsteps? The influence of gender and learning experiences on entrepreneurial intentions. International Small Business Journal, 37(6), 642-663. https://doi.org/10.1177/026624261983893

Boleková, V., Košecká, D., & Ritomský, A. (2017). Spracovanie Kvantitativnych dát o obetiach násila pomocou SPSS.Bratislava: IRIS – Vydavateľstvo a tlač, s.r.o.

Bracci, E., & Vagnoni, E. (2011). Understanding small family business succession in a knowledge management perspective. IUP Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(1), 7-36. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1776593

Carlyle, T. (1840). On heroes, hero-worship and the heroic in History. London: Chapman and Hall. Retrieved from https://test.tomat0.me/resources/references/carlyle_on-heroes.pdf

Carr, J. C., & Sequeira, J. M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: a theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of Business Research, 60(10), 1090-1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.016

Cavicchioli, D., Bertoni, D., & Pretolani, R. (2018). Farm succession at a crossroads: the interaction among farm characteristics, labour market conditions, and gender and birth order effects. Journal of Rural Studies, 61, 73-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.06.002

Cieślik, J., & Van Stel, A. (2017). Explaining university students’ career path intentions from their current entrepreneurial exposure. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(2), 313-332. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2016-0143

Cisneros, L., Deschamps, B., Chirita, G. M., & Geindre, S. (2022). Successful family firm succession: Transferring external social capital to a shared-leadership team of siblings. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 13(3), 100467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2021.100467

Corona, J. (2021). Succession in the family business: the great challenge for the family. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 64-70. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12770

Danihel, P. (2022). Vplyv pomerových ukazovateľov na rozhodovací proces spoločnosti. Journal of Corporate Management and Economics, 14(1), 5-14. Retrieved from http://www.maneko.sk/casopis/pdf/1_2022.pdf

Daspit, J. J., Holt, D. T., Chrisman, J. J., & Long, R. G. (2016). Examining family firm succession from a social exchange perspective: a multiphase, multistakeholder review. Family Business Review, 29(1), 44-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515599688

Dyer, W. G. J. (2021). My forty years in studying and helping family businesses. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 56-63. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12768

European Family Businesses (2020). Facts & Figures. Retrieved from https://europeanfamilybusinesses.eu/

Fairlie, R. W., & Robb, A. (2007). Families, human capital, and small business: Evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. ILR Review, 60(2), 225-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390706000204

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(6), 301-326. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037

Family Owned Business Institute. (2021) Grand Valley State University. Family Firm Facts, February 12th. Retrieved from https://www.gvsu.edu/fobi/family-firm-facts-5.htm

Filser, M., Kraus, S., & Märk, S. (2013). Psychological aspects of succession in family business management. Management Research Review, 36(3), 256-277. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171311306409

Glover, J. L. (2014). Gender, power and succession in family farm business. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 276-295. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-01-2012-0006

Hoffmann, A., Junge, M., & Malchow-Møller, N. (2015). Running in the family: parental role models in entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 44, 79-104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9586-0

Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. SAGE Publication.

Hofstede, G., Noorderhaven, N. G., Thurik, A. R., Uhlaner, L. M., Wennekers, A. R., & Wildeman, R. E. (2004). Culture’s role in entrepreneurship: self-employment out of dissatisfaction. In Brown, T. E., & Ulijn, J. (Eds.), Innovation, entrepreneurship and culture: the interaction between technology, progress and economic growth (pp. 162-203). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Holienka, M., Gál, P., & Pilková, A. (2019). GUESSS 2018 Slovensko. Študenti vysokých škôl a podnikanie. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave. Retrieved from https://www.guesssurvey.org/resources/nat_2018/GUESSS_Report_2018_Slovakia.pdf

Humphreys, M. M. (2013). Daughter succession: a predominance of human issues. Journal of Family Business Management, 3(1), 24-44. https://doi.org/10.1108/20436231311326472

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Jurova, M. (2016). Výrobní a logistické procesy v podnikání. Praha: Grada Publishing.

Kallmuenzer, A., Tajeddini, K., Gamage, T. C., Lorenzo, D., Rojas, A., & Schallner, M. J. A. (2022). Family firm succession in tourism and hospitality: an ethnographic case study approach. Journal of Family Business Management, 12(3), 393-413. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-07-2021-0072

Kirkwood, J. (2009). Motivational factors in a push‐pull theory of entrepreneurship. Gender in Management, 24(5), 346-364. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410910968805

Korab, V., Hanzelkova, A., Mihalisko. M. (2008). Rodinné podnikání: způsoby financování rodinných firem, řízení rodinných podniků, úspěšné předání následnictví. Brno: Computer Press.

Lam, J. (2009). Succession process in a large Canadian family business: a longitudinal case study of the Molson family business: 1786-2007 (Doctoral dissertation, Concordia University). Retrieved from https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/976205/1/NR63434.pdf

Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593-617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318

Lucky, E. O. I., Minai, M. S., & Adebayo, O. I. (2011). A conceptual framework of family business succession: bane of family business continuity. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(18), 106-113.

Machek, O., & Hnilica, J. (2015). Hodnocení vlivu zastoupení rodiny ve vlastnické a řídící struktuře firem na jejich finanční výkonnost pomocí metody zkoumání shody párů. Politická ekonomie, 63(3), 347-362. Retrieved from http://polek.vse.cz/pdfs/pol/2015/03/05.pdf

Marques, P., Bikfalvi, A., & Busquet, F. (2022). A family imprinting approach to nurturing willing successors: evidence from centennial family firms. Family Business Review, 35(3), 246-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486522109

Michel, A., & Kammerlander, N. (2015). Trusted advisors in a family business’s succession-planning process — An agency perspective. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(1), 45-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.10.005

Nicholson, N. (2008). Evolutionary psychology and family business: a new synthesis for theory, research, and practice. Family Business Review, 21(1), 103-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00111.x

Nyberg, A. J., Fulmer, I. S., Gerhart, B., & Carpenter, M. A. (2010). Agency theory revisited: CEO return and shareholder interest alignment. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 1029-1049. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.54533188

Plana-Farran, M., Arzubiaga, U., & Blanch, A. (2022). Successors’ future training in family farms: the impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-01046-2

Robinson, P. B., & Hunt, H. K. (1992). Entrepreneurship and birth order: fact or folklore. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 4(3), 287-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985629200000017

Schenkel, M. T., Yoo, S. S., & Kim, J. (2016). Not all created equal: Examining the impact of birth order and role identity among descendant CEO sons on family firm performance. Family Business Review, 29(4), 380-400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486516659

Schlepphorst, S., & Moog, P. (2014). Left in the dark: family successors’ requirement profiles in the family business succession process. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(4), 358-371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.08.004

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., Pablo, A. L., & Chua, J. H. (2001). Determinants of initial satisfaction with the succession process in family firms: a conceptual model. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(3), 17-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870102500302

Sharma, P., & Irving, P. G. (2005). Four bases of family business successor commitment: Antecedents and consequences. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 13-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00067.x

Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., Powell, B. C., & Zhou, H. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: are women or men more likely to enact their intentions?. International Small Business Journal, 36(1), 60-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617704277

Sieger, P., Zellweger, T., Fueglistaller, U., & Hatak, I. (2021). Global student entrepreneurship 2021: insights from 58 countries (2021 GUESSS Global report). Retrieved from https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/265333/1/GUESSS_2021_Global_Report.pdf

Sulloway, F. J. (2001). Birth order, sibling competition, and human behavior. In: Holcomb, H. R. (Ed.), Conceptual challenges in evolutionary psychology: innovative research strategies (pp. 39-83). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0618-7_3

Tabares, A., & Cano, J. A. (2018). University students’ succession intention: GUESSS Colombia study evidence. Revista ESPACIOS, 39(35), 21. Retrieved from https://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n35/18393521.html

Vera, C. F., & Dean, M. A. (2005). An examination of the challenges daughters face in family business succession. Family Business Review, 18(4), 321-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2005.00051

Wasim, J., & Almeida, F. (2022). Bringing a horse to water: the shaping of a child successor in family business succession. European Journal of Family Business, 12(2), 156-172. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v12i2.14631

Yan, J., & Sorenson, R. (2006). The effect of Confucian values on succession in family business. Family Business Review, 19(3), 235-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00072.x

Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Englisch, P. (2012). Coming home or breaking free. Career choice intentions of the next generation in family businesses. Ernst & Young. Retrieved from https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/244886/1/Coming%20home%20or%20breaking%20free_II_final.pdf

Zhang, Y., Duysters, G., & Cloodt, M. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10, 623-641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0246-z