1. Introduction

Due to environmental volatility, technological advancement and globalization, business dynamic forces are shifting rapidly and continuously influencing business’s sustainability (Tahir & Sabir, 2015). The established business model empowers the business sustainability strength through resource distribution, which justifies a significant part in the marketplace. Miller (2011) stated that measuring sustainability is problematic and challenging due to the long-standing landscape. Moreover, they indicated that businesses might be affected by numerous environmental changes and competitive threats. Geissdoerfer et al. (2018) explored that the capability of prediction could swiftly facilitate the business model changes, which drives continuous advantages for the sustainable position of family firms.

Sustainability encourages firm economic growth without harming the environment. The actions of the firm impact the external environment. The rapid forces of competition and globalization force firms to follow ethical ways to attain long-term sustainable objectives (Curado & Mota, 2021). Previous researchers have argued that sustainable income and gains are significant indicators of a firm’s sustainable performance (Well & Easman, 1979, cited in Easman et al., 1979). In the bible of corporate virtues, the firm’s growth resides only on profits. Another study by Chandler and Williamsons (1962), cited in Whittington (2008), indicates that multi-dimensional organizations measure a firm’s sustainable performance through the annual rate of return on stockholders’ equity (Armour & Teece, 1978).

Vekataran and Varadarajan (2011), cited in Tipape and Jagongo (2019), stated that the firm’s financial performance ensures its ability to operate effectively and efficiently to achieve more profitable growth and continue the business for a long period of time. Research on large firms has concentrated on financial performance’s objective measures, such as costs, growth and profitability (Damanpour et al., 2012; Geringer& Hebert, 1991). Research related to management prefers to use accounting variables like return on asset (ROA), return on investment (ROI), return on equity (ROE), interest margin (P/E ratio NIM), and earning per shares (EPS) (Wamiori et al., 2016). The present study veiled the financial performance aspects of the family-owned business, mostly explored in terms of profitability in-depth as return on investment (Basco, 2013; Mazzi, 2011).

In recent years, family business research has gained more attention (Chrisman et al., 2010; De Massis et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2012). Previous family-owned firms operated with the central tenant of earning profitability (Kumar et al., 2020). In European countries like Spain and Italy, the family business amounts to about 95% of total gross domestic product (GDP) (Kumar et al., 2020). Similarly, in other European countries, like Germany or France, family-owned business accounts for 60 to 70 percent of the total gross domestic product of the country and the same ratio for United States (De Vries et al., 2007). Research indicate that family firms are different in governance mechanisms and these differences explain family firm’s innovative behaviors (Kampouri & Hajidimitriou, 2023). The survival of a family-owned business depends on many variables like managerial competencies, family involvement, succession planning and lack of interest, etc. (Boyatziz & Soler, 2012; Braji, 2021; Mokhber et al., 2017). In addition, many researchers have explored the effect of competencies on family-owned business performance and found that competencies positively affect the business performance of family firms (Aslan & Pamukcu, 2017; Neff & Dahm, 2015).

Family involvement is an important determinant to consider a firm as a family firm (Litz, 1995). For example, a family desire to transfer ownership through succession is often considered a unique attribute of each family firm. By adopting these approaches, family firms possess some strategic control over the firm’s resources and processes (Soleimanof et al., 2018). Family involvement in business has both positive and negative impacts on a firm´s production. For example, family firms prefer to use internal financial rather than external resources (Soleimanof et al., 2018). Family firms are often interested in innovation opportunities linked to capital enhancement (Hillebrand, 2018). They enhance their capital by efficiently using their resources that drive firm innovation.

Past research has emphasized on the pertinent role of resources (Mosakowski, 2017). Resource contribution may swap by the passage of time, but they always play an important role in improving each firm’s performance. Previous organizations considered land, labor, and capital as the resources of production. Overtime, the role of resources has evolved. In the 1990s, Barney (1991) made significant contributions. Barney (1991) propounded the resource-based view (RBV), which regard a firm as a bucket of resources, classified as tangible and intangible resources. Those resources, which have VRIN features, facilitate firms in catering competitive advantage inside the business market (Barney, 1996). RBV focuses on resource diversity. Another view propounds like knowledge-based view (KBV), which believes knowledge is the strategically sound resource for the firm (Grant, 1996). The central tenet of KBV is the knowledge as the sound resource supports to cater firm competitiveness.

Furthermore, Barney (1996) classified resources into physical, human and organization resources. Resource advantage theory (R-A) expands the view of Barney and additionally categorizes resources into physical, organizational, financial, informational, legal and relational terms (Hunt & Madhavaram, 2020). Later, the R-A theory categorized resources by proposing a hierarchy of resources in basic and higher-order resources (Hunt & Lambe, 2000). These higher-order resources drive firm competitive performance (Teece et al., 2021). Another logic proposed by Vargo and Lusch (2004) is called service-dominant logic (S-D), categorizing resources as operant and operand. S-D logic emphasizes the primacy of operant resources upon operand resources (Vargo & Lusch, 2016). Operant resources are intangible, whereas operand resources are tangible and hard. The volatility of operant resources facilitates firms in developing sound and fierce position in the business world (Abongo et al., 2019). Thus, categorizing operant resources is the least explored area of literature (Abongo et al., 2019). Recent research proposed the details about employee’s and customers’ operant resources (Waheed & Kausar, 2020) and indicated the gap of other actor’s operant resources as the least discussed area of research. The present article focuses on the conception of operant resources and propose that family firm owner’s operant resources support firm profitability.

The philosophy of agile is based on capabilities because agility facilitates quicker response and environmental compatibility, allowing organizations to improve their strategic orientation (Yeganegi & Azar, 2012). Agility denotes the skills to think and respond efficiently. Agile operant resources provide the ability to scan the environment and react quickly. Moreover, agility relies on operant resources based on the competencies that facilitate the organization’s strategic solid orientation (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2003). A firm’s capability to react proactively against surprising environmental changes can be increased through agility (Sune& Gibb, 2015). The evidence shows that role of agile operant resources as antecedent of firm’s performance need to be explored in the context of family-owned business in Pakistan. Hence, this study aims to ascertain the concealed role of agile operant resources grounded on the agile abilities of family-owned businesses’ (FOBs) owners that facilitate firms in catering profitability, which drives firm sustainable performance. However, sustainable firm performance is a broader phenomenon that has multiple indicators. Therefore, this research focuses only on those intangible resources that support profitability and act as an indicator to drive sustainable performance. The following two research questions are highlighted and addressed through this research:

RQ1. How do agile operant resources of FOB owners encourage a firm’s sustainable performance?

RQ2. How do FOB owners’ agile operant resources support firm profitability?

The introduction of this study resides in research objectives and research questions. The second section of the study shows conceptual and empirical evidence based on past studies. The third section comprises research methodology findings concerning data structures and propositions. The last section comprises the discussion, conclusion, proposed conceptual framework, research implications and future avenues.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainable firm performance

The foundation of business success and survival has shifted toward uncertainty, volatility, dynamism, and imperative environmental conditions (Parmar et al., 2010). While locating these challenges, the parameters of determining firm performance have also changed. Performance is a multidimensional phenomenon used to define business success by achieving the objectives of the business. These objectives can be long-term such as improving efficiency, reducing turnover rates, increasing market shares, having goodwill and increasing profitability. Organizations adopt two criteria for sustainable performance measurement, i.e., financial measurement and market measurement criteria. These measurement criteria are classified in terms of ROI, market share, profit margin of sales, the growth rate of ROI, increase in sales and the firm competitive position in the market.

Assets and skills support the firm’s sustainable performance (Aaker, 1989). Research claims that homogeneous top management groups interact efficiently in intense competition; whereas heterogeneous groups would better facilitate adaptation when environmental changes occur. Therefore, top management group composition is considered as the source of firm sustainable performance (Murray, 1989). Sustainability can be generated through the potential of competitiveness and the best way of managing it in the long run (Buckley et al., 1988). In the literature, extensive research indicates entrepreneurial orientation and its impacts on firm sustainable performance through strategic orientation (Wiklund, 1999). Firms are closely interconnected through social, economic, and environmental factors, which play a critical role in achieving sustainability in terms of growth (Tyteca, 1998). Role of intangibles in which intellectual capital, business relationships, human competencies, and social capital is crucial in determining firm sustainable performance (Allee et al., 2000, cited in Venezia et al., 2018). Firms with high information technology (IT) capability resources can cater to long term sustainable development. These IT capabilities comprise IT infrastructures, human IT resources and IT-enabled intangibles. These resources’ effective and efficient use support firm sustainable development (Bharadwaj et al., 2013). Business intelligent systems contribute to firm sustainability management. It supports monitoring sustainable practices. As the business world is changing rapidly, aligning managerial practices with business strategy become the focal point of sustainable development. Previous researchers proposed that market, entrepreneurial and learning organizations play a significant role in firm sustainable development. Each orientation enhances corporate success, but its potential cannot be determined in isolation. Findings suggest that market, entrepreneurial and learning organization enhances firm performance (Alegre & Chiva, 2013). Sustainability creates an impact through present actions on the ecosystems, societies and future environment. These impacts should be incorporated and must be reflected in corporate strategic planning. Research suggests that organizational innovation capability depends on several types of innovation in which technological capabilities in products and processes favor the development of firm’s sustainable performance (Yu et al., 2017). Corporate culture is based on collective corporate behaviors of employees and top management that drive a firm’s sustainable performance. These companies adopt environmental and social policies to thrive as a highly sustainable firm. An organization’s top management often play an integral part in sustainable development by encouraging the role of executive incentives and organizing transparent procedures for stakeholder engagement. Therefore, this research considered profitability as the one indicator of sustainable performance and the study highlights those agile operant resources which support family firms in achieving profitability.

2.1.1. Profitability and firm intangible resources

Organizational growth is measured in the context of firm capacity to earn profit. Therefore, profitability always remains a prime concern, but the paths to achieve and maintain profitability are changing rapidly (Heikkilä et al., 2017). Usually, profitability comes from increased revenues and decreased costs (Pearson & Ryley, 2015, cited in Al Amin & Maina, 2020). Firm downsizing, de-layering, re-engineering, consolidation, mergers and in-depth focus on quality have re-directed firm’s attention toward performing more by using fewer resources and becoming more efficient and cost-efficient to improve earning and profitability (Al Amin & Maina, 2020). Companies are trying different initiatives for the reduction of cost, such as decentralization, cost analysis, cycle time, downsizing, empowerment, variable pay, workout, leadership development, rewards, recognition and economic value added (EVA) that are focused on cost elements and lead to maximization of profit (Pearson & Ryley, 2015, cited in Al Amin & Maina, 2020). These functions are designed to reduce the costs of people, processes or other business expenses. On the other side, executives are continuously re-discovering the second dimension of the profit equation: revenue growth. The point is to experience profitable growth (Al Amin & Maina, 2020).

Intangible/operant resources play a significant role in the creation of company value and increase in revenues. Recent research focuses on managing its value (Vargo et al., 2017). Intangible assets comprise on intellectual property (e.g., patents, trademarks, etc.) brand and customer loyalty (Abdikeev, 2018). Hall (1993) has proposed that corporate identity as an intangible asset for the firm supports sustainable positional advantage (Lin et al., 2021). Corporate reputation is regarded as a valuable intangible resource that supports in driving firm profitability. Fombrun and Shanley (1990) posit that reputation reflects a firm’s values, which establish social status (cited in Pérez-Cornejo et al., 2020). It reflects the public image and upholds the trust in the industry. Reputation attracts investors, which enhance firm investment and profitability (Lin et al., 2021). A strong reputation has an indirect impact on equity, market evaluation on consumers and ultimately builds trust for the product quality and premium prices. Quantitative research has shown evidence of strong relationships among reputational strength and return on sales. Reputation depicts how favorably equity markets evaluate a firm’s performance (Pearson & Ryley, 2015, cited in Al Amin & Maina, 2020). Organizational positive reputation improves operational performance, depicting a positive frame for interpreting firm events and shareholder trust (Lin et al., 2021). Potential shareholders show interest in firms with consistency and good reputations compared to high profit figures.

Financial reputation acts as the general evaluation of a firm’s financial prospects. This general evaluation is based on the expectations of profitability, stability and growth (Fombrun & Shanely, 1996, cited in Pérez-Cornejo et al., 2020). Those firms that possess favorable financial reputations have long term financial performance. These companies prove to be more attractive for potential exchange partners. These relationships are more durable and compensatory. Partners emphasize higher quality or less favorable terms of exchange which in turn enhance performance (Pérez-Cornejo et al., 2020). A growing body of literature asserts that good reputations have value and significantly impact a firm’s overall financial performance. Corporate reputation is a critical resource with the potential of value creation inhabiting intangible characters of imitation (Brandtzæg, 2014).

RBV proposed that the firm’s resources and capabilities support it to attain superior firm performance (Barney, 1991, cited in Nwankpa & Roumani, 2016). Firms’ operant resources support to cater firm’s sustainable performance outcomes, due to characteristics of resource imitations and non-substitutability (Deephouse, 1997, cited in Doan et al., 2020). RBV highlights the importance of intangible resources and capabilities because they have potential of value creation and is not easy to imitate, ; therefore, it supports firm’s sustainable performance (Hall, 1991, cited in França & Rua, 2018). Two resources gain prominence in the literature i.e. organizational culture and firmly embedded knowledge (Teece et al., 2021). These two intangible resources are strategically significant. Intangible resources help in developing a firm corporate reputation, which drives firm growth and superior financial performance (Dowling et al., 1994, cited in Truong et al., 2017) because these resources have a high level of ambiguities, non-substitutability and non-imitability (Barney, 1991, cited in Nwankpa & Roumani, 2016). Corporate reputation follows the long-term and gradual way-out, but once it establishes it increases profitability and growth opportunities. For example, Aaker (1991) posits through a marketing perspective a strong link between the brand name and firm value (cited in Tanveer & Lodhi, 2016). In finance, investors give value to intangible resources. In each discipline, operant resources are pertinent in ensuring sustainable firm performance (Wernerfelt, 1984, cited in Zhang et al., 2021).

Four types of intangible resources drive four distinct capability differentials that lead toward sustainable competitive advantage (Hall, 2009). Research classifies two types of resources i.e. assets and skills. Intangible and operant resources comprise of patents, copyrights, contracts, registered designs, formulas, trade secrets etc. (Brown & Ulgiati, 1997). It lays the basis of regulations. The second type of resources based on the firm’s reputation are databases, internal and external networks and positional differentials. Two types of intangible/operant skills, i.e., know-how of employees and distributors are treated as the functional differential (Helms, 2016). The second type of resource is organizational culture comprises people attitudes and behaviors, perception of quality services and ability to manage change within an organization known as cultural differential (Omil et al., 2011). Company reputation, product reputation, employee know-how (knowledge), organizational culture and social networks all intangible/operant resources significantly impact firm financial performance, leading to sustainable competitive advantage (Dierickx & Cool, 1989, cited in Barney, 2012).

Firms attain profitability through maximizing resource productivity (Pearson et al., 2015a). Resources alone are not sufficient until they permit firms to enact productive work within specific business markets. Intangible resources play an important role in creating value (Porter, 1980; Barney, 1991). These resources are the inputs of the production process and drive advantage for firms (Grant, 1991). Resources provide a competitive advantage but SCA is achieved through resources that are scarce, unique, non-tradable, inimitable, durable, idiosyncratic and non-substitutable (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993). In economic literature, the main concern of a company is profitability. Potential resides on the firm’s internal resources and its role proves as a determinant of difference in profitability among firms (Peteraf, 1993; Teece, 1981, cited in Katkalo et al., 2010). RBV proposed that firm can boost potential by efficiently managing intangibles (Fleisher, 2002, cited in Omil et al., 2011). An organization can attain excellence by managing business practices and resources (Mankins & Steele, 2005).

During the last several years, Pakistan has gained exceptional economic development in unlisted enterprises, notably FOBs. Small FOBs often become limited liability corporations (Jahiu, 2020). These FOBs have become the backbone of the economy of Pakistan (Qureshi et al., 2013). The rapid expansion of SME fuels the development of Pakistan’s private sector. Family owners possess unique agile operant resources that enhance the firm’s profit. This study focuses on how a FOBs’ agile operant resources support to enhance the firm’s profit.

2.2. Role of operant resources in family-owned businesses

Generally, a FOB is defined as an organization operated and owned by family members with self-ownership and management (Feldman et al., 2016; Villalonga & Amit, 2020). Three viewpoints are found in extant literature regarding family firms, i.e. t ownership viewpoint, management viewpoint, and subjective viewpoint (Villalonga & Amit, 2020). The viewpoint of ownership states that some FOBs are controlled by two or more family members with significant equity possession (Sciascia et al., 2013). The management viewpoint depicts firm having family ownership and family members managing daily operations (Spriggs et al., 2013). The subjective viewpoint stipulates that a family business has no ownership of equity but owner perception. It means that a business is considered as family business if the owner has faith that it is a family business (Stockmans et al., 2010). Muttakin et al. (2015) observed a family business in terms of concentration of ownership rather than the structure of diffused ownership. Moreover, countries with weak regulatory institutes dominate the family business in terms of the business landscape. Among different conceptualization, the best way to define a FOB is through “three-circle” concept, which explain that the interaction of the family, the company and the owners must be looked at as a whole to understand the FOB holistically (Diaz-Moriana et al., 2019; Tagiuri and Davis, 1996, cited in Zellweger, 2013).

In FOBs the chief executive officer (CEO) would be a family member and next kin will be based on succession; this leaves a room for smooth and long term strategies; and a business process will be trickled down from generation to generation. It may reflect more stability and continuation. Family firms enhance their capital by efficiently using resources to drive innovation. Family firms prioritize humans as a pertinent resource. They manage and socialize their employees that drive toward competitive advantage and improved firm performance (Habbershon & Williams, 1999). FOBs promote a family-based unique working environment that supports and promotes employee’s commitment and dedication. Some attributes prevail in family firms based on the shared sense of identity, better communication with greater privacy, and emotional involvement among co-workers (Tagiuri& Davis 1996). These attributes of family business culture enhance employee loyalty and trust which helps to increase employee output (Bertrand & Schoar, 2006). Another advantage of family firms is the reduction of the expense of employee audits, since employee and employer contractual protection costs like union representation may be substantially less in family firms (Barbera & Moores, 2013). Literature proposed that FOBs have lower recruitment costs and human resource costs; therefore, considered more effective than other family firms compared to labor-intensive businesses (De Paola et al., 2009). Thus, the reasons for family firm success lies in cost-effective labor resources and family strategic level ownership.

Two primary factors drive the superior success of family companies. Initially, senior management of FOBs is based on family members who have greater organizational-specific expertise that enables efficient decision-making. Secondly, a FOB has a long-term investing perspective to make judgments for the future. Consequently, family businesses have beneficial effects on ownership that supports company success. The role of resources has been extensively studied in the literature on family life and work (Halbesleben et al., 2012). Organizational sustainable performance is impacted positively by the resource called family support (Jain & Nair, 2017, cited in Campo et al., 2021). Receiving help in the family or at work is seen as a beneficial resource that enhances the quality of family life and work (Jain & Nair, 2017, cited in Campo et al., 2021). Supportive family resources increase work productivity and strengthen the company’s market position (Jain & Nair, 2017, cited in Campo et al., 2021). When FOB owners have family and professional support, their motivational level improves and they perform diligently (Jain & Nair, 2017, cited in Campo et al., 2021). With reference to diversified literature, current study aims to clarify the concealed role of other family operant resources of FOBs owners that supports to earn profitability.

2.3. Progressive configuration of resources

Despite the widespread usage of the term resources in scholarly work, the meaning still seems evolving. Essentially, resources are productive or economic components required to complete a task or to engage in an endeavor and achieve desired results (Fratini et al., 2019). Capital, labor and land are included in the classic understanding of basic resources (Wilson, 1960, cited in Piven & Cloward, 1995). In the framework of resources, organization resources are viewed as strengths that companies may employ to develop and execute their plans (Porter & Rossini, 2019; Teixeira et al., 2019). Numerous scholars made important contributions to resources by classifying lists of resources according to business characteristics (Fratini et al., 2019). Resources are grouped into three types: organizational capital resources (coordinating system, informal and formal planning, firm structure and controlling), human capital resources (relationship, intelligence, judgment, experience and training) and physical capital resources (raw material, organization physical location, equipment, plant, and physical technology) (Sony & Aithal, 2020). In the RBV, Barney (1991) gives two concepts of physical and immaterial resources (Jogaratnam, 2017). RBV highlights physical resource diversity and the VRIN (non-replaceable, inimitable, rare and valuable) quality of resources as the organization’s strategic reasons of developing key success factors (Barney, 2021). The knowledge-based perspective highlights operant assets as solid strategic assets (Grant & Carolis, 2002, cited in Roberto et al., 2020). The resource-advantage theory (R-A), based on the RBV, defines resources as physical and operant elements (Hunt & Morgan, 2017). It illustrates that a competitive resource leads to greater financial business performance. The R-A concept distinguishes between essential and greater resources (Guillory et al., 2019). The R-A concept offered a paradigm of company resources via the lens of S-D logic by establishing a hierarchal categorization of organizational resources. Further, S-D logic divides resources into operand and operant resources. Conventionally, resources act as productive or financial variables necessary to complete an operation or achieve an objective (Wilson, 1960, cited in Piven & Cloward, 1995). Two categories are found in the literature:

Operand/static/tangible resources: These include capital, labor, and land (Wilson, 1960, cited in Piven & Cloward, 1995).

Operant/intangible resources: These resources operate to convert, multiply or evolve. It is based on competencies, abilities and knowledge (Lusch & Vargo, 2004, cited in Tregua et al., 2021). These properties may adapt, alter and flourish. They are immaterial, ongoing and vibrant. It offers a foundation for seeing competencies, skills and knowledge as operant/intangible resources (Constantin & Lusch, 1994; Vargo & Lusch, 2004, cited in Tregua et al., 2021).

3. Research Methodology

Research philosophy reflected the researcher’s worldview. For selecting research philosophy, research begins with the knowledge of epistemology and ontology. This article endorsed an epistemological stance that is interpretivism and consider several interpretive stances of truth (Hug et al., 2021) alongside ontology resides on FOB owners. Research question of this study indicated exploratory research that inspected family firm owner’s resources and how it facilitates firm profitability. In this viewpoint, this research borrowed qualitative methodology (Eisenhardt, 1989) by adopting abduction approach, beginning from certain assumptions that search most likely explanations from the observations. The subjective point of view is important to understand the depth of studied phenomenon.

3.1. Data collection and demographical details of informants

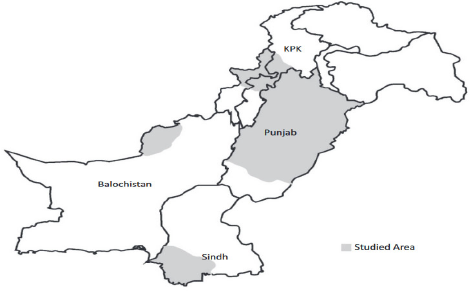

Purposive sampling is used to collect data from FOBs. The rationale of selecting this technique is to collect more relevant data. In purposive sampling, sample is selected based on judgement by researcher and central focus resides on specific characteristics of population (Higginbottom, 2004). FOBs were the unit of observation. Initially, those FOBs who have sound serving history in last 10-30 years of diversified sectors from all over Pakistan are considered. The sample resides on 30 FOBs in four different regions of Pakistan. Figure 1indicates the studied region in the map of Pakistan. Author’s gathered data through triangulation especially in qualitative research (Pettigrew, 1990; Van de Ven, 1992). Primary data sources were interviews and other sources were observations, company websites, brochures, formal and informal telephonic follow-ups etc. An interview guide formed regarding the phenomenon after in-depth and extensive review of literature. Interview guide is based on several semi-structured open-ended questions related to phenomenon. During interviews questions were asked from informants. Alike, what do FOB owners possess the significant agile resources? How FOB owner’s resources facilitate firm profitability? All FOBs of Pakistan are considered for unit of analysis. Detail lists of family businesses were gathered through Karachi and Lahore Stock Exchange.

Figure 1. Map of Pakistan spotlighting the studied area

Table 1. Demographical details of informants

|

Sr.#

|

Gender

|

Nature of Family Business

|

Family Generation

|

Informants Designation

|

No. of Interviews

|

Industry

|

Participation in Business

|

Working Experience (Years)

|

Qualification

|

Firm Age (Years)

|

|

1

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Glass & Aluminium

|

Active

|

10

|

BBA (Hons)

|

35

|

|

2

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Water Filtration Plants

|

Active

|

34

|

MA (USA)

|

34

|

|

3

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Textile

|

Active

|

10

|

BA

|

35

|

|

4

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

Director

|

2

|

Engineering & Management

|

Active

|

10

|

MA (UK)

|

30

|

|

5

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Sports

|

Active

|

11

|

BS (Hons)

|

11

|

|

6

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Hardware

|

Active

|

20

|

BA

|

25

|

|

7

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

3rd

|

Director

|

1

|

Watches

|

Active

|

10

|

BA

|

40

|

|

8

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

3rd

|

Director

|

2

|

Cosmetics

|

Active

|

12

|

BA

|

50

|

|

9

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Textile

|

Active

|

10

|

MBA (HR)

|

40

|

|

10

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Solar Energy

|

Active

|

14

|

BS (Engr)

|

20

|

|

11

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Nuts & Herbs

|

Active

|

40

|

Master

|

50

|

|

12

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

Director

|

1

|

Bicycle

|

Active

|

10

|

M.Phill

|

40

|

|

13

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

Director

|

2

|

Services

|

Active

|

10

|

BA

|

31

|

|

14

|

Female

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

Head HR

|

1

|

Automobile

|

Active

|

15

|

MBA (HR)

|

28

|

|

15

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Glass & Aluminium

|

Active

|

30

|

BA

|

35

|

|

16

|

Female

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Technology

|

Active

|

10

|

MS.c (US)

|

30

|

|

17

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Carpets

|

Active

|

10

|

BA

|

18

|

|

18

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Medical

|

Active

|

15

|

BS

|

33

|

|

19

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Solar Energy

|

Active

|

10

|

BA

|

10

|

|

20

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Textile

|

Active

|

13

|

CFA

|

15

|

|

21

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Services

|

Active

|

10

|

CFA

|

15

|

|

22

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Services

|

Active

|

15

|

CA

|

30

|

|

23

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Tiles & Ceramics

|

Active

|

10

|

M.Phill

|

15

|

|

24

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Steel & Iron

|

Active

|

15

|

BA

|

3

|

|

25

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Steel & Iron

|

Active

|

20

|

BA

|

50

|

|

26

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Medical

|

Active

|

11

|

D-Pharmacy

|

18

|

|

27

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Education

|

Active

|

12

|

M.Phill

|

38

|

|

28

|

Male

|

Partnership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Tiles & Ceramics

|

Active

|

15

|

BS

|

24

|

|

29

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

2

|

Medical

|

Active

|

21

|

D-Pharmacy

|

10

|

|

30

|

Male

|

Sole Ownership

|

2nd

|

CEO

|

1

|

Medical

|

Active

|

12

|

D-Pharmacy

|

30

|

Table 1 indicated the detail demographical descriptions of interviewees. Total 30 informants were selected in which 28 were males and 2 were females. All are working as active participants. Mostly interviews are conducted from 2nd and 3rd generation. Two to three rounds of interviews are taken to reach the essence of phenomenon. Those informants who are acting as Directors, Head of the business and CEO level were considered for interviews. Author’s hide the identities of informants to secure privacy matters. Mostly informants actively working experience revolves around 10-25years of controlling family firms in multiple sectors. Their level of education somehow was Graduation and Master level etc. Most of the interviews were telephonic and skype due to the Covid-19 crisis following Government lockdown restrictions. But some of the interviews were taken through personal visits. During interviews informants’ convenience and comfort considered on priority basis so interviews were recorded based on the permission of informants but field notes are preferred to capture the exact information. All interviews are transcribed. One of the merits of our research is to cover many industry perspectives about agile operant resources. The logic of controlling the diversified views is the commonality of agile operant resources and earning profitability as the central tenant in each sector. The current article opted for theoretical sampling and grounded theory (Thomas, 2006). Saturation level depicted the number of informant’s interviewed for study. This study shown saturation level after conducted 30 informants’ interviews. In grounded theory, theoretical sampling encourages the development of theoretical categories as mentioned in this study. In theoretical sampling, researchers collected information grounded on some research questions developed by authors based on extensive literature review. Theoretical sampling supports researchers to determine the range of variations in emerging categories and properties. Hence, this article indicates the cumulative perspective on the pertinent role of agile operant resources in FOBs and their utilization of resources related to earning profitability in long run to ensure family firm sound sustainable position in industry.

3.2. Analysis of data

Data analyzed by researchers and research questions directed toward abductive approach in qualitative. Findings from the analysis grounded on raw data are not moderated through prior theoretical lenses (Thomas, 2006). Sparse research is available by indicating those operant resources possessed by family firms that facilitate to cater profitability within Pakistan. Consequently, a grounded theory, famously titled as Gioia method, has been used to indicate the hidden mystical role of the firm owner, which encourages the family firm’s profitability. For analysis, this study opted Gioia methodology. Gioia is a well-recognized and rigorous method that nurtures the requirements of novel concept formation through an abductive research approach by following the rigorous standards (Gioia et al., 2013). Gioia is substantially used in strategic management, marketing, organizational behavior and service science literature (Bettis et al., 2015). Thus, Gioia method is used in the relatively novel business stream. The research method assumed researcher and informant as knowledge agents capable of analyzing the socially constructed realities (Gioia et al., 2013). In the field of management sciences, Gioia is famous for new concept formation. This research applied coding propound by Gioia et al., 2013 methodology to introduce rigor and novelty in research. Gioia methodology based the assumptions of socially constructed organizational world and everyone have their own reality. This article adopted complete Gioia methodology as research technique for qualitative rigor. Least research is available in management disciple which used Gioia as research methodology. Gioia et al. (2013) methodology analyzes the data in 1st order, 2nd order and aggregate dimensions to reach the deep soul of the phenomenon. Hence, it offers the methodological rigor and originality for new researchers. Gioia methodology comprises on three steps for analysis i.e. first-order concepts (based on voice of informants), second-order themes (based on voice of researchers) and aggregate dimensions (embedded with 1st-order and 2nd order concepts). Second-order grounded on voice of researchers. Third-order or aggregate dimensions represent higher-order concepts and encourage novel inclusion in theory enhancement. Current study conducts within the domain of FOBs which foster the novel weaves of knowledge in family business studies. The rational for selecting Pakistan in data collection is the pertinent presence of FOBs in Pakistan (Khanna & Yafeh, 2007). This study is useful for practitioners especially family firm owners by providing significant insights about hidden agile operant resource’s role to manage sustainable development.

4. Findings/Results

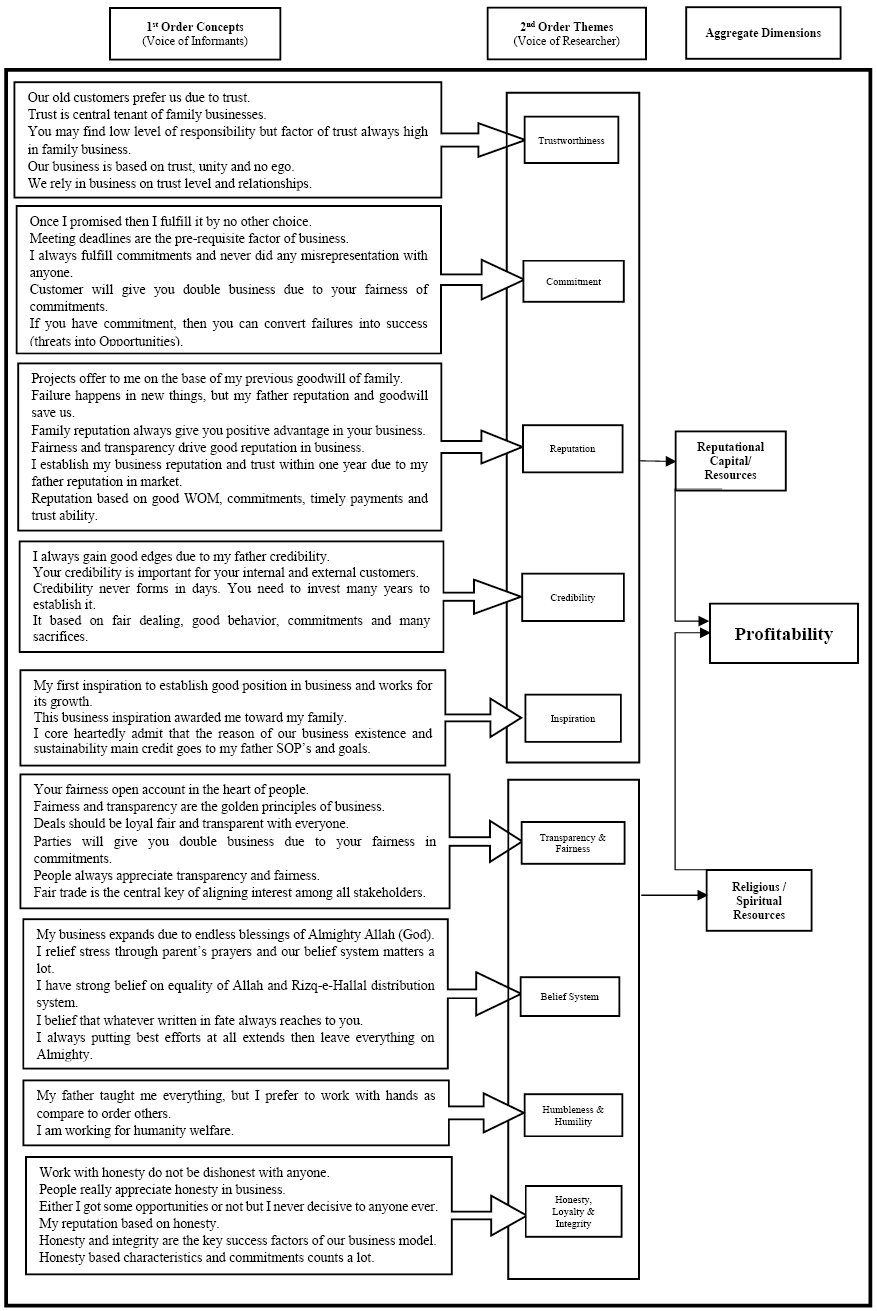

The main objective of each firm is to maximize profitability. For this, family owners possess some agile operant resources supporting profitability. These are reputational resources, religious resources, agile soft skills, esteeming relationships, performance excellence, and efficiency. Reputational resources drive firm profitability, and it is rooted in trustworthiness, commitment, reputation, inspiration and credibility. Respondents repeatedly reported religious resources impact on the maximization of profit. It is based on transparency, fairness, belief system, honesty, loyalty, integrity, humbleness, and humility. Giving esteem to relationships is dominant in attaining a family firm’s profitability. It is based on respect and recognition, self-efficacy and patience. Performance excellence and efficiency are based on the following sub-themes i.e., structure thinking patterns, efficiency, excellence and hard work. Figure 2 shows those agile operant resources which support in attaining profitability.

Figure 2. Family owner’s resources in profitability

4.1. Reputational Capital / Resources

Reputational resources have become an idiosyncratic valuable resource for today’s hypercompetitive business market. The family firms considered reputation as an inimitable resource due to the owning grand history (unique), firm identity, reputation, firm values, trustworthiness and inspirational stories anchored in the minds of all stakeholders (Blombäck, 2011; Krappe et al., 2011). All these characteristics make the business a brand and a potential source of firm sustainable performance. In today’s volatile environment, where every stakeholder possesses multiple endless choices and novel information streams, firm reputation becomes the pertinent means of differentiation (Hulberg, 2006; Keller, 2008). It creates a unique combination and impression about the firm’s rich history of commitments and product quality in the minds of all stakeholders (Anisimova, 2007). It supports stakeholder’s in capturing worth able information that helps in the firm decision-making process (Lievens & Slaughter, 2016). Due to the emerging demand of brands in today’s world, scholars and practitioners widely debated about the phenomenon of family firm branding (Pieper & Baldauf, 2013, cited in Binz et al., 2013; Tasman – Jones, 2015) which is also strongly linked with reputational resources. Family branding establishes based on firm reputational resources grounded on the combination of many factors, such as trustworthiness, rich family history, values, significant reputation and business identity (credibility), meeting deadlines (commitment) and inspiration etc. By analyzing the iterative responses of informants, a few of the themes under this aggregate dimension will be discussed as follows.

4.1.1. Trustworthiness

It can be defined as “How dependable are our words and deeds? It is the most central factor in the family business. For example, Informant 22 reported that “Trust is the central tenant of family businesses”. In a family business, it establishes a sound relationship among all stakeholders (Beck, 2016). For example, as Informant 3 stated, “, “We rely in business on trust level relationships”. Trust supports establishing strong customer orientation. For example, Informant 9 mentioned, “Our old customer prefers us due to trust”. As Informant 21 stated that “You may find a low level of responsibility, but the factor of trust is always high in family businesses”. Trustworthiness is considered the most significant operant resource in family business and the central notion of reputational resources revolves around it. It is important to understand that a stakeholder partnership is complex to establish where aligning of interest is the central source for developing stakeholder relationships. For establishing and maintaining a sound relationship, especially in family firms, some key operant resources play a significant role which must possess by family owner essential to develop stakeholder partnership (Butt et al., 2021). Although, firm’s sustainable performance is a broader concept cover many sub-concepts and complex to develop stakeholder’s partnership is one of the main themes that help in the development of the family firm’s sustainability.

4.1.2. Commitment

Another most important determinant of reputational resources is commitment. It leads toward full-filling deadlines and promises to all stakeholders. For example, Informant 2 said, “Once I promised then I fulfilled it by no other choice”. As Informant 4 stated that “Meeting deadlines is the pre-requisite factor of business”. Full filling commitment is the source of converting future threats or failures into opportunities (Urde & Greyser, 2016). If you commit (ability), you can convert failures into success (threats into opportunities). As Informant 1 reported that “Your customer will give you double business due to your fairness in commitments”. It establishes through many factors i.e. patience, history, quality-based relationships, positive WOM and trust ability etc. as Informant 4 stated, “In industry trust, deadlines meet up, preplanning, work with loyalty, past experiences and full-filling commitments matters a lot”. The commitment was the most iterative theme inferred from family business owner interviews and it is the central source of establishing a reputation in family businesses (Higgins, 1977).

4.1.3. Reputation

Reputation refers to the public’s long term overall evaluation of an organization’s behavior established by the passage of time. It is the set of cumulated beliefs held by the stakeholders and agencies that the company cannot handle (Brown et al., 2006). For example, as Informant 8 reported that “Projects offer me on the basis of my father’s previous goodwill in business”. Informant 11 stated, “I established my business reputation and trust within one year due to my father’s reputation in the market”. Stakeholders can infer reputation from family ownership signals as Informant 18 signaled that “family ownership reputation always gives you a positive advantage in your business”. Many factors determine reputation. For example, Informant 26 reported that fairness, transparency, commitments, trust-ability, good WOM and timely payments drive reputation”.

4.1.4. Credibility

Credibility is linked with firm identity which “shows the mental alliance about the firm held by organizational members” (Brown et al., 2006). It addresses the question about who we are as a firm?” and indicates the firm features which internal stakeholders consider as enduring, distinctive about the organization (Zellweger et al., 2010). It can be considered as the essence of the firm. As informant 11 reported that “I always gain good edges due to my father’s credibility in business” Credibility is the central differentiating feature to all internal and external stakeholders. For example, informant 11 stated that “your credibility is important for your internal and external customers”. Several factors involved in its formation. For example, informant 21 reported that it “is based on fair dealing, good behavior, commitment and many sacrifices”. There is no shortcut to establish it. Like informant 22 stated, “credibility never forms in days. You need to invest many years to establish it.” Once it forms, it is tough to maintain in the long run. Credibility is the central theme of reputation.

4.1.5. Inspiration

Inspiration is the main intrinsic factor that drives business survival and success. It is a hidden force that urges inside but gradually rooted in dreams. In a family business, the main driving force of succession persuasion and sustainability is an inspiration. For example, informant 6 said, “This business inspiration awarded me toward my family”. Informant 29 stated, “My first inspiration is to establish a good position in business and work for its advanced growth”. So, in family businesses, inspiration acts as an intrinsic force to drive willingness to do any business which nurtures by the passage of time. Inspiration creates followership & learning ability that drives the striving power of reputation.

Proposition 1(a). In family firms, the stronger their reputational resources, their opportunities of catering profitability become sounder, which enhances firm sustainability.

4.1.6. Religious / Spiritual resources

Religion is the core key determinant of any business, especially in Asian countries. The key factor of one’s core values is the belief system called religion. Usually, the belief system is linked with religious values and synonymous with religious beliefs (Szocik, 2017). Religious values grounded on religious scripture provide strong insides about the set of beliefs (Djupe & Gwiasda, 2010). Religious values are the religious resources that are followed by the business community to develop a sustainable business model (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Religious resources promote feelings of self-esteem, optimism, positive behaviour, practices of fairness and transparency, honesty, loyalty and integrity and enhance humbleness and humility etc. factors that drive sustainability in a business (Rupp et al., 2011). Each religion provides some common business ethics principles, same as Islam. Islam always encourages fair and transparent principles of doing business. Each deal in business should be fair and transparent rooted in loyalty and honesty grounds. Each businessman should consider himself accountable in front of Almighty Allah. Being a business owner, each businessman possesses some religious resources which are essential to follow. The whole conception & mechanisms of the owner revolve around the principles of religion because Islam provides the full road-map to all businesses. Some of the themes that emerged under this aggregated dimension are mentioned below.

4.1.7. Transparency and fairness

Transparency and fairness are the fundamental principle of all business belonging to any religion. The basic fundamental of every business is based on fair dealing among parties. All exchanges should be transparent and clear among parties. Transparency and fairness are sources of reducing stress. When you are fair in dealings, it ultimately reduces stress and strengthens relationships. The most recurring theme of this research is transparency and fairness. Most family firms consider it as the core value of the business. , informant 11 stated, “Parties will give you double business due to your fairness and commitments”. It is a source of aligning stakeholder’s interest. As informant 23 stated, “Fair trade is the central key of aligning interest among all stakeholders”. Informant 14 said that “People always appreciate fairness and transparency”. As informant 9 claimed that “Your fairness in business opens accounts in the heart of people”. However, in the light of the informant’s responses, transparency & fairness is the core-operant resource of a FOB owner.

4.1.8. Belief system

Another strong religious resource is the belief system. It is the most significant and strong determinant of FOB Owner resources. It is a source of satisfaction for humans. Everyone follows some set of beliefs toward God. The belief system strongly links with religiosity and the reason for success and relief stress. For example, informant 12 reported, “My business expands due to the endless blessings of Almighty Allah”. Everyone has some set of beliefs which they follow and improve over time. As informant 8 stated that “I believe that whatever written in fate always reaches to you”. It acts as an inner driving force. As informant 11 said, “I relieve stress through parent’s prayers and my belief system matters a lot”. It links with individual religious resources.

4.1.9. Humbleness and humility

Another important resource possessed by the family owner is humbleness and humility. Most of them work for charitable purposes through CSR practices. Like informant 6 spotted that “I am working for humanity welfare”. Humbleness element is very important in business. As informant 9 declared, “My father taught me everything so I prefer to work with my own hands rather than to order others”.

4.1.10. Honesty, loyalty and integrity

Another core competency of each business is honesty, loyalty and integrity. Many owners consider them as values of the business and the source of long-term market survival. For example, informant 8 stated, “Work with honesty, do not be dishonest with anyone”. It establishes a reputation in the business as informant 11 reported that “My reputation is based on honesty”. It is the characteristic of a person and key factors of success. Informant 29 reported that “Honesty and integrity are the key success factors of our business model”. Those businesses that do not follow honesty cannot survive in the long run, so it is an essential religious resource that must possess by the family firm owner and is the reason for business sustainability.

Proposition 1(b). In family firms, the stronger their religious resources, their opportunities of catering profitability become sounder, which enhances firm sustainability.

4.2. Agile soft skills

4.2.1. Interpersonal skills

Communication has the importance of backbone in any business. For developing and maintaining long term relationships with all stakeholders, communication plays a pivotal role in it. Communication is the part of interpersonal skills which is essential for all businesses in any sector. The most significant skills possessed by every family owner are interpersonal skills. It is a source of establishing a sound reputation in the market. For example, informant 11 reported, “Good communication and soft skills are essential for developing a strong reputation”. Interpersonal skills help in dealing. As informant 13 stated, “ Business depends upon your way of dealing” and “Being a FOB owner, you should have sound interpersonal skills”. It is an agile resource that every owner every owner must possess to enhance business. It is a way of developing collaboration among all stakeholders that drive sound relationships among them.

Proposition 1(c). In family firms, the stronger their agile soft skills, their opportunities of catering profitability become sounder, which enhances firm sustainability.

4.3. Performance excellence and efficiency skills

The phenomenon of performance excellence and efficiency skill varies in the context of each firm. It is a wider construct, and each firm has its indicators to determine performance excellence and efficiency. Some of the firms consider quality in relationships, satisfaction, customer orientation, business model innovation, profitable increment; efficient services and the firm’s sustainable performance etc. are sound indicators of excellence. In this research, informants emphasize systematic thinking patterns, work efficiency and goals attainment and thriving with quality are the pertinent indicators of performance excellence and efficiency in family firms.

4.3.1. Efficiency

The theme of efficiency is also broad and covers many factors. Everyone explains efficiency in their own way. It is a subjective nature phenomenon that varies based on firm nature and respondents. Some informants respond that timely and quality completion of projects is the source of efficiency. Such as informant 4 reported that “My focus is on quality completion of the project in time so that we can avail the next project sharply to ensure firm survival”. Informant 17 claimed that “I like the smart work efficiently. Efficiency can be enhanced by studying the mindset of customers in business and providing products accordingly. For example, as informant 17 stated that “I want to target the mindset of people in the way that they want “providing quality services is another source of determining efficiency. As informant 22 stated that “I always provide quick quality service to customers”.

4.3.2. Excellence

Many firm owners consider excellence attainment as the best performance indicator. Again, excellence resides in many other concepts. For example, as informant 3 stated “Our focus on thriving based on quality (products, process and relationships). “Performance resides in excellence for us, not in the money”. As informant 8 stated, “Goals should be excellence and money is the buy product”.

4.3.3. Devotion / Diligence

Each business requires a lot of efforts and hard work to reach a tipping point. A successful journey holds many hidden secrets of hardships and sacrifices in business. Each family owner believes that “Every day is a new struggle for ensuring its growth”. Hard work is the key to earning a solid profit. As informant 13 reported, “When you put hard efforts then ultimately you deserve a good amount of profit” and informant 26 stated, “If your homework complete then nothing can defeat you”. So, being an FOB owner, work is the pre-requisite resource that ensures firm survival in the long run.

Proposition 1(d). In family firms, the stronger their performance excellence & efficiency, their opportunities of catering profitability become sounder, enhancing firm sustainability.

4.4. Relationship proneness

Relationship proneness is important in establishing long term sound relationships among all stakeholders. In businesses, the nature of the relationship varies with all stakeholders due to work based on the nature of businesses. Each organization requires high-quality networking-based relationships with all stakeholders to deal with dramatic changes that happen in the business world continuously. Especially in family firms the roots of relationships linked with ancestors & their preceding/present owners are always curious & caring about their relationships with all stakeholders due to protecting the firm as the brand. They handle relationships with much care. FOB owners always strive to seek & give respect and recognition to others. Handle challenges and crisis phases with immense patience and always strive to establish quality able relationships with others. By analyzing the informant’s responses, a few of the themes under this aggregate dimension will be discussed as follows.

4.4.1. Relationship quality

The high-quality relationship is the pre-requisite operant resource for family firms. Relationship quality enhances resource management and improves firm performance outcomes (Varki & Rust, 1998). Better relationship quality supports knowledge sharing and enhances the adaptability and flexibility of the firm. The organization needs high-quality relationships with their network partners (all stakeholders) to collaborate to co-create value. Relationship quality is a higher-order resource and based on many other resources (constructs). The relational dimension of social capital depicts behavioral attitudes and norms and the reliable relationship based on a person’s or group’s motivations and willingness (Adler & Kwon, 2002). In many firms, managers and employees reduce stress by showing an honest and trustworthy relationship (Castro & Roldan, 2013). For example, informant 6 said, “I establish a relationship by convincing parties on transparent and fair dealings”. Long-term relationships establish based on appreciation and acknowledgement of significant contributions. Such as informant 19 stated that “Appreciation and care are the determinants of good & sound relationships.

Additionally, family businesses are grounded on the long-term inherited relationship with all stakeholders. Therefore, relationship proneness is the pre-requisite factor in the growth of family firms. As informant 11 stated, “I always oblige people for establishing relationships in long run”. For this, they celebrate diversity-based events. As informant 6 reported that “We celebrate diversity-based events to strengthen the relationships with employees “Relationships strengthen through full filling promises. As informant 18 claimed, “Relationship establishes through full-filling commitments and quality promises with all stakeholders”. Furthermore, “Punctuality and politeness are the sources of developing long-lasting relationships in the family business”. Informant 22 said.

4.4.2. Respect and recognition

To establish any relationship, respect and recognition are the pre-requisite factors of relationship quality. No relationship can succeed in the long run if respect and recognition are not intricate. In the family firms, respect and recognition are the core value of enterprises. In business, many stakeholders involved in it and their soundness of relationship is based upon respect and recognition in long run. It further based on many other factors such as informant 9 reported that “Full-filling timely commitment is the source of establishing respect and recognition in the market”. Following SOPs and fair dealing in business drives respect in the industry. Informant 11 stated, “I always prefer to live with respect and dignity in business”. Hence, respect & recognition establish over time & the pertinent useful operant resource of establishing the business in the long run.

4.4.3. Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the belief of an individual in his/her capacity to execute productive behaviors that cater to performance attainments (Bandura, 1977). It reflects the confidence level of an individual in yourself. It also comes under the umbrella of the operant resource of a person (owner). It increases over time due to knowledge and experience. For example, informant 12 stated, “, “I possess a great deal of faith and believe in himself”. It is a source of winning the battle of business completion. Informant 29 indicated, “Confidence is the key to winning the battle of business success”. It increases and strengthens over time. As informant 17 reported that “My good decisions boost me up and gave lots of confidence”. It is a power of behavior that boost up gradually. As informant 19 stated that “I always take rational decisions itself and stand on it”. Self-efficacy is the dynamic capability and operant resource of an individual in which he/she controls own behavior and emotions, which helps to establish long-term relationships with all stakeholders that drive firm profitable configuration.

4.4.4. Patience

Another pertinent determinant of relationship quality is patience. It is very essential in business and for dealing with all stakeholders. It is an operant resource of a FOB owner to handle all situations with patience. As informant 12 stated that “I always handle customers with patience”. It is essential for business long-run survival and sustainability. As informant 8 stated, “Being a FOB owner, you must have patience because each business does not work the whole year”. Especially at the time of pressure and stress, it is the most useful operant resource which must possess by a family business owner. As informant 29 stated that “You have to deal with immense pressure sometimes to handle things with patience”. Dealing with immense pressure with patience is the key to firm long-term survival and sound relationships.

Proposition 1(e). In family firms, the stronger their relationship proneness, the more their opportunities of catering profitability become sounder, enhancing firm sustainability.

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

In each era, resources often remain popular in driving firm competitive position. Due to environmental dynamism, resource pertinence evolves overtime (Maiti et al., 2020). Initially, land, labor and capital were scrutinized as effective firm resources (Porter, 1981). By the evolution of time, most researchers introduced the categorize of resources. Further categorize of resources were physical (technology, plant and raw material, etc.), human capital (training and experiences, etc.) and organizational capital resources (firm structures) (Podra et al., 2020; Williamson, 1975). The decade of the 1990s was considered an influential span of resources compared to other decades. Several famous researchers paid pivotal attention toward resources as weapons for driving firm effective performance (Podra et al., 2020). Very famous perspective of resources propounds by Barney (1991), which is considered the fundamental premises in the domain of resources. RBV categorizes resources into tangible and intangible extent that encourage the heterogeneous nature of resources grounded on VRIN attributes (Maiti et al., 2020). These VRIN attributes having valuable, rare, imitable non-substantial resources on especially intangible resources (Peteraf, 1993). These unique elements of resources support firms to secure sustainable positions (Bingham & Eisenhardt, 2008). Another view known as knowledge-based view emphasizes the importance of intangible resources (skills, knowledge and abilities) as a sound determinant of firm competitiveness (Della Corte et al., 2013). Furthermore, R-A classifies resources into basic and higher-order categories (Hunt & Morgan, 1995). Then, Vargo and Lusch (2004) proposed service dominant (S-D) logic grounded on the domain of RBV and R-A theory by tagging resources as operand (tangible) and operant (intangible) (Vargo & Lusch 2008). S-D logic encourages the central dominant role of operant resources upon operand resources as a driver of value creation in fourth foundational premises (Vargo & Lusch, 2010). Previous research indicated the pertinent role of customer and firm operant resources embedded with operand resources determined as a source of superior firm performance (Madhavaram & Hunt, 2008). Therefore, the categorization of operant resources is the less explored area in past studies. This research highlighted the gap by indicating the role that other actors may support in enhancing firm performance. Thus, the current study is conducted to fill this niche (gap) by surfacing the concealed role of agile operant resources that supports to sustainable development.

Previous firms determined the growth of the firms in terms of firm capacity to generate profit (Teece, 2018). Profitability has always remained the key focus of every enterprise in each era, but their mechanisms and paths have changed due to the complexity in the business world (Chen & Lees, 2018). Organizations strive to earn profit through firm downsizing, business re-engineering, mergers, acquisitions, strengthening stakeholder relationships and innovating business model etc. (Pattanayak, 2020). Organizations often practiced some initiatives for lowering cost in terms of partial privatization, six sigmas’, cost analysis, team building, outsourcing, value-added economy, contractual employees and variable pay with the focal attention of catering profit (Chen & Lees, 2018). While adopting each strategy, the role of resources always remains pertinent, especially intangible/operant resources (Vafeas & Hughes, 2020). Efficient utilization of intangible resources always makes viable tangible/operand resources. These agile operant/intangible resources support the firm to cater sustainable competitive advantage (Vafeas & Hughes, 2020). Same as the operant resources of FOB owners supports to drive firm profitability. This research aims to explore agile operant resources that support profitability. These resources are reputational, religious resources, agile skill sets, performance excellence and efficiency, etc.

Proposition 1. In family firms, the stronger their operant resources their opportunities of catering profitability become sounder that enhances firm sustainability.

Current study research question emphasizes exploring the agile operant resources of FOB owners that drive profitability. In each era, Firm growth has always been measured in terms of profitability. Over time, it continuously remains the core business issue but its path of determination remains changed. Resources always play a pertinent role in earning profitability especially intangible/operant resources that create firm value which drives the firm’s sustainable performance. The focus of each firm is to maximize profitability. The same as the family firm’s central goal is to gain profit by using all pertinent resources. Family firms are famous for using operant resources especially ancestor’s reputation & credibility which play a significant role in firm profitability. Limited literature was available on FOB owner’s operant resources that support in determination of firm profitability. This study addressed this discrepancy/gap through interviews of FOB owners. However, it is inferred that reputational resources, religious resources, agile soft skills, relationship proneness and performance excellence and efficiency drive the family firms towards profitability, which smoothens the firm’s sustainable development in today’s competitive market.

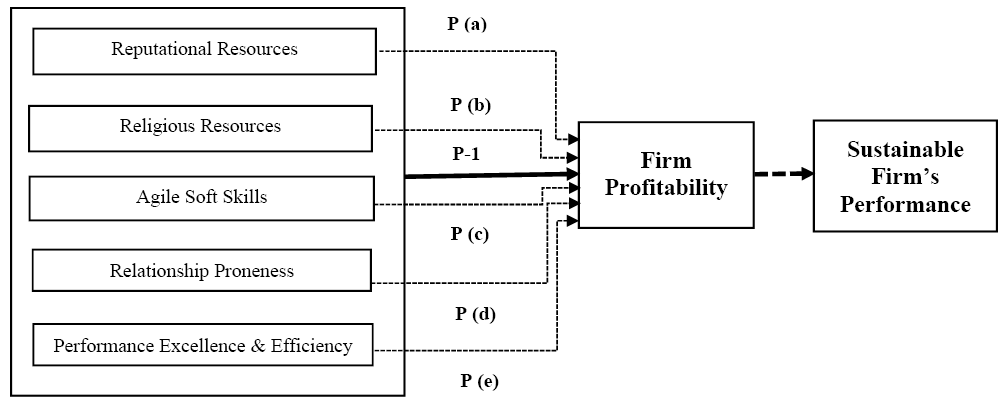

6. Theoretical Contributions

Competing in a volatile business world has become the foremost challenge foreach firm. For this, firms striving hard to establish a sustainable position in the market. Family firms are famous for establishing sustainable positions within the market due to their ancestors’ sound, rich history. Historical evolution significantly impacts family firm performance and guides to handle the dynamic challenges raised toward the environment. Each generation possesses some pertinent resources, especially operant ones, which transformed through forebears. These operant resources enable FOB owners to handle environmental challenges bravely by catering novel profitable pathways. A large number of family firms competing in diversified sectors and earning ample amount of money. Besides this, family owners employed some operant resources for scanning favorable pertinent niches. Based on informant responses, FOB owners utilize reputational resources, religious resources, agile soft skills, performance efficiency and excellence and relationship proneness to ensure family firm’s sustainable performance. In the base of findings and discussion, current research propounds a conceptual framework in below Figure 3 portraying the important role of agile operant resources in catering profitability. It is deduced that the family firm’s sustainability around having zestful characteristics mentioned below Figure 3. The current study proposed in the framework indicates the theoretical contribution that was revealed from our current investigation. Study advanced the theory by strengthening the ground reality of the phenomenon (profitability) with distinct subjective insights. For academics, study proposed conceptual framework enclosed with data that adds value in theory development. This research and its emerging categories motivate academicians to explore the role of other actors’ operant resources in FOBs and other firms. The proposed framework can be utilized for future empirical investigation.

7. Managerial Implications

Current research remains beneficial for practitioners, mainly FOB owners, because each firm striving hard to cater to sustainable positions in a dynamic business world. Current study proposed an applicable framework for FOBs working in Asian countries through providing new avenues for firm sustainable development by highlighting the pertinent viable role of agile operant resources. It opens new doors of growth, innovation and progress for FOBs by confirming the pivotal role of individual FOB owner-operant resources. Practical experiences always serve as the foundational tool of learning new spirals of knowledge that facilitate the corporate sector to compete better. Managers can polish these highlighted agile operant resources which encourage the new roads of firm profitability. Each FOB can adopt and nurture these resources to ensure firm sustainability in today’s volatile business market.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework of firm’s sustainable performance

8. Limitations and Future Avenues

Current research has several limitations, the data collection phase is restricted among interviews and other sources. Furthermore, data can be gathered through other sources or triangulation methods. Highlighted emerging themes of this study can be investigated through empirical investigation method. Study is restricted to family firms. In future, non-family firms can be considered for study. Study is limited to 28 males and 2 females. In-future more females can be considered for interviews or female focus study can be conducted. This research studied the profitability phenomenon as the source of sustainable performance in future other phenomenon can be studied for sustainable performance. Qualitative research can be conducted in other sectors by studying the same phenomena.

Furthermore, future research may be conducted in other European countries. This study is limited to family firms in Pakistan. Future studies may focus on all types of firms, not only family-owned ones. They can also do a comparison of FOBs and other firms; Do FOBs have an edge due to existing agile operant resources that are trickled down as a heritage. This conceptual model can be tested through empirical data. This study has only focused on the ambit of FOBs in Pakistan and it can be studied on a broader platform i.e. across Asia or world-wide. Culture & sub-culture dimensions can be considered for the study when we increase the range of the research.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the journal’s anonymous referees for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of this article. Usual disclaimers apply.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this article’s research, authorship and/or publication.

Ethical statement

The authors confirm that data collection for the research was conducted anonymously and there was no possibility of identifying the participants.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1989). Managing assets and skills: the key to a sustainable competitive advantage. California Management Review, 31(2), 91-106. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166561

Alegre, J., & Chiva, R. (2013). Linking entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of organizational learning capability and innovation performance. Journal of small business management, 51(4), 491-507. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12005

Abdullah, T., & Brown, T. L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethno cultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 934-948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003

Abongo, B., Mutinda, R., & Otieno, G. (2019). Innovation capabilities and process design for business model transformation in Kenyan insurance companies: a service dominant logic paradigm. Journal of Information and Technology, 3(1), 15-45. http://repository.kemu.ac.ke/handle/123456789/1028

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17-40. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.5922314

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140105

Antolín-López, R., Delgado-Ceballos, J., & Montiel, I. (2016). Deconstructing corporate sustainability: a comparison of different stakeholder metrics. Journal of Cleaner Production, 136, 5-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.111

Armour, H. O., & Teece, D. J. (1978). Organizational structure and economic performance: A test of the multidivisional hypothesis. The Bell Journal of Economics, 9(1), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/3003615

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barney, J. B. (1996). The resource-based theory of the firm. Organization Science, 7(5), 469-469. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.5.469