European Journal of Family Business (2022) 12, 137-155

Adapt or Perish! A Systematic Review of the Literature on Strategic Renewal and the Family Firm

Remedios Hernández-Linaresa, Triana Arias Abelairab

aCentro Universitario de Mérida, Universidad de Extremadura, Mérida (Badajoz), Spain

bFacultad de Empresa, Finanzas y Turismo, Universidad de Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain

Research paper. Received: 2022-05-24; accepted: 2022-12-20

JEL CLASSIFICATION

L26, M14, O3

KEYWORDS

Family firm, Literature review, Strategic renewal

CÓDIGOS JEL

L26, M14, O3

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar, Revisión de la literatura, Renovación estratégica

Abstract The objective of this paper is to examine the current state of strategic renewal research in family businesses, identifying the main research gaps and providing a path for future research to the academics. To do so, we have performed a systematic and comprehensive review of 21 studies (20 articles and 1 book chapter) about strategic renewal and family business published between 2009 and 2022. Our comprehensive analysis reveals that the majority of studies to date are empirical studies that have focused on the strategic renewal’s antecedents, while the strategic renewal’s outcomes remain unexplored. This and other significant research gaps are identified and discussed in this review, which emphasizes the need for further research about the topic.

¡Adaptarse o morir! Una revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre renovación estratégica y empresa familiar

Resumen El objetivo del presente trabajo es examinar el estado actual de la investigación sobre renovación estratégica y empresa familiar con el fin de identificar los principales gaps de investigación y proporcionar un camino a los académicos para futuras investigaciones. Para ello hemos realizado una revisión comprensiva y sistemática de 21 trabajos (20 artículos y 1 capítulo de libro) publicados entre 2009 y 2022. Nuestro análisis exhaustivo revela que la mayoría de los estudios publicados hasta ahora son de naturaleza empírica y se han centrado en los antecedentes de la renovación estratégica, mientras que sus resultados permanecen inexplorados. Esta y otras importantes lagunas en la investigación se identifican y discuten en esta revisión, que subraya la necesidad de seguir investigando sobre el tema.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v12i2.14718

Copyright 2022: Remedios Hernández-Linares, Triana Arias Abelaira

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author:

E-mail: remedioshl@unex.es

1. Introduction

Today’s dynamic business environment is characterized by substantial and often unpredictable technological, political, and economic changes, which forces organizations to transform (Schmitt et al., 2018). A firm’s strategic renewal, defined as the firm’s ability to envision the future (Mzid et al., 2019) and ensure its survival (Burgelman, 1983), is a key consideration in understanding firms´ long-term survival and prosperity (Schmitt et al., 2018). For family businesses, long-term sustainability is their main goal (Chua et al., 1999), but only 30% of them survive to the second generation (Gascón, 2013). A reason to explain this low percentage of survival could be that family firms are not able to continuously renew themselves, as it is required to succeed in today’s business dynamic environment (Ratten, 2020). Hence, understanding the strategic renewal process in the context of the family business is especially relevant not only because they account for approximately two-thirds of all firms worldwide and account 70-90% of annual Gross Domestic Product and 80% of employment (De Massis et al., 2018), but also to help public administrations to identify ways of improving survival rates of such firms (Cucculelli et al., 2016; Handler Miller, 2008). That is, for ensuring that family businesses are passed down from generation to generation, emphasis should be placed on strategic renewal (Luu, 2022). For this reason, scholars have started to pay attention to the strategic renewal of family firms (Cucculelli et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2013; Weimann et al., 2021), generating a complex body of research. However, this body of research is highly fragmented, as reveals the very scant number of journals that have published more than on article about the topic (see more details in the Methodology section). This fragmentation of the literature on the confluence between strategic renewal and family firms calls for an effort to integrate and make sense of extant research. Strategic renewal is the continuous adaptation of organization’ resources and outputs in response to environmental changes (Albert et al., 2015). Family firms tend to have lower resources than non-family firms (Meroño-Cerdán, 2017), however, the recent Covid-19 pandemic forced many of them to decide between renewal or death. The pandemic has stressed that changes in the environment can be drastic and unforeseen, and that family firms have to cope with change. It is thus timely to advance our knowledge on strategic renewal in order to offer future lines of research that will encourage scholars to deepen our understanding on the topic.

To this aim, we carry out a comprehensive and systematic literature review to answer our two main research questions: What do we know about family firms’ strategic renewal? and what should we know about how family firms renew themselves and cope with change? To answer these questions, we adopted the process by Tranfield et al. (2003) and performed a systematic literature review drawing on the two most comprehensive sources of indexed academic work: Web of Science (WoS) and Elsevier Scopus (Scopus) databases (Mariani et al., 2021). Thus, we reviewed 21 studies at the intersection of strategic renewal and family business to illustrate the evolution of the research field and provide the academic community a guiding framework for new research.

Our work makes important contributions to the strategic renewal and family firm’s literature. First, to our best knowledge, no attempts have been made to carry out either a systematic literature review or bibliometric mapping of research at the intersection of strategic renewal and family firms. This study, hence, contributes to literature by integrating and critically examining prior research on the topic, that is, by providing a broad overview of the state-of-the-art on strategic renewal in family firms. Second, leveraging on our review and systematization of current stock of literature, we identify critical research gaps and provide scholars with a potential future research agenda that endows strategic renewal and family business.

2. Methodology

Systematic literature reviews are characterized by relying on structured, transparent and reproducible methods (Calabrò et al., 2019; Tranfield et al., 2003). Therefore, in line with recent systematic literature reviews in the family business field (e.g., Ge & Campopiano, 2022), we follow Tranfield et al. (2003)’s three-step process. The first step is the planning of the review and requires the researchers get familiarized with the topic, frame the research purposes and set the research questions. To familiarize with the topic, we read a recent systematic literature review on strategic renewal in general (Schmitt et al., 2018), as well as several works related to corporate entrepreneurship (e.g., Randolph et al., 2017) and strategic renewal (e.g., Cucculelli et al., 2016; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020) and family firm, including the seminal study (Mitchell et al., 2009). Based on the knowledge gleaned from these readings, we established the research questions presented in the third paragraph of the Introduction section. The second step consisted of searching for relevant studies using inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as of description and synthesis of studies finally selected. The third and last step for performing a systematic literature review, according to Tranfield et al. (2003), is the reporting and dissemination of the results, drawing future research directions.

After having planned the review (step 1), the second step of the Tranfield et al.’s (2003) process starts with the selection of relevant studies. Thus, considering that “the choice of the database of documents is one of the most important steps in performing a reliable literature review” (Aparicio et al., 2021), we built a comprehensive database by searching in two comprehensive citation databases (Mariani et al., 2021), WoS and Scopus, which have been used in other systematic literature reviews in the field (e.g., Hernández-Linares & López-Fernández, 2018; Su & Daspit, 2021). The search criteria is shown in Table 1. Specifically, we combined the keyword “famil*” with the following keywords: “strategic renewal”, “self-renewal”, “organizational renewal” (“famil*” AND “strategic renewal”; “famil*” AND “self-renewal”; “famil*” AND “strategic renewal”). We sought only documents written in the English language, which is a common practice in literature reviews (Schmitt et al., 2018), and in line with other studies (e.g., Landström et al., 2015), we did not limit our search to journal articles as in emerging fields of research, early studies often appear first in books (Hernández-Linares et al., 2018). To provide a comprehensive review of the literature and to avoid any omission and/or potential bias caused by considering only a set of relevant journals (Dinh & Calabrò, 2019; López‐Fernández et al., 2016), we did not look for particular journals; instead, we used the entire WoS and Scopus databases. Similarly, to prevent distortion of the results, the selected time limit was the maximum allowed (including papers in press), although the first document found was published in 2009 by Mitchell et al. Our search therefore covers almost 14 years of strategic renewal research and family business research (2009-2022).

The initial WoS and Scopus databases search, performed on October 24, 2022, yielded 3108 and 1742 documents respectively. We merged the results from the two databases and given that 1331 studies appeared in the two databases, the final set of documents to analyze comprised 3519 studies. Then, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the titles and abstracts of these 3519 documents, and when it was required, we downloaded the documents and read them independently (following the procedure used by Ge and Campopiano, 2022) to exclude those studies that were not relevant to answer our research questions. Specifically, we eliminated from our list all misclassifications, that is, studies that did not investigate strategic renewal or not about family firms. Thus, 19 studies (18 articles and 1 book chapter) were considered relevant for this research. To complete the list identified in our searches in both databases (WoS and Scopus), in a second phase, we performed an additional manual search, by reading all references listed in the documents identified in the first phase, but we did not identify more studies to be included in our review. Similarly, in order to provide an up-to-date a review as possible, we analyzed those works that had cited such 19 studies since 2022. Two new studies were identified to be included in our review (Anggadwita et al., 2022; Issah et al., 2023).

|

Scopus |

||

|

“Famil*” and following keywords: “strategic renewal” “self-renewal” “organizational renewal” |

|

|

|

Search date |

10-24-2022 |

10-24-2022 |

|

Number of studies |

3108 |

1742 |

|

Studies appearing in the two databases |

1331 |

|

|

Excluded studies |

1310 |

|

|

Studies included in our literature review |

19 |

|

|

Studies identified in the manual search |

2 |

|

|

Studies finally included in our literature review |

21 |

|

From 21 studies finally included in our systematic literature review, 20 studies are peer-reviewed articles published in 18 different journals, 14 of which (80%) are listed in the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) Academic Journal Guide 2021. Journal of Family Business Management and Journal of Management and Governance are the only journals that has published 2 articles about the topic. The remaining study included in our literature review is a book chapter (Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020).

|

Table 2. Identified studies by source |

|

|

Journal name* |

Number of articles |

|

Journal of Family Business Management (ABS1) |

2 |

|

Journal of Management and Governance (ABS1) |

2 |

|

Administrative Sciences (-) |

1 |

|

Business History (ABS4) |

1 |

|

Cross Cultural & Strategic Management (ABS2) |

1 |

|

Corporate Ownership & Control (-) |

1 |

|

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice (ABS4) |

1 |

|

International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal (ABS1) |

1 |

|

Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies (-) |

1 |

|

Journal of Business Ethics (ABS3) |

1 |

|

Journal of Business Research (ABS3) |

1 |

|

Journal of Family Business Strategy (ABS2) |

1 |

|

Journal of International Entrepreneurship (ABS1) |

1 |

|

Journal of Small Business Management (ABS3) |

1 |

|

Leadership & Organization Development Journal (ABS1) |

1 |

|

Long Range Planning (ABS3) |

1 |

|

Scandinavian Journal of Management (ABS2) |

1 |

|

Strategic Management (-) |

1 |

|

Total articles |

20 |

|

Books chapters |

1 |

|

Total |

21 |

|

*In brackets the journal's ranking in the Academic Journal Guide 2021. A dash implies that the journal is not included in the guide. |

|

To conclude with the second step of the Tranfield et al.’s (2003) three-step process, and in line with other systematic literature reviews (e.g., Creevey et al., 2022; Ge & Campopiano, 2022), key information from all studies (e.g., year, journal, abstract, definitions, research design, samples, etc.) was then entered into an Excel spreadsheet to facilitate the descriptive analysis presented in next section.

3. Mapping the Strategic Renewal and Family Business Research

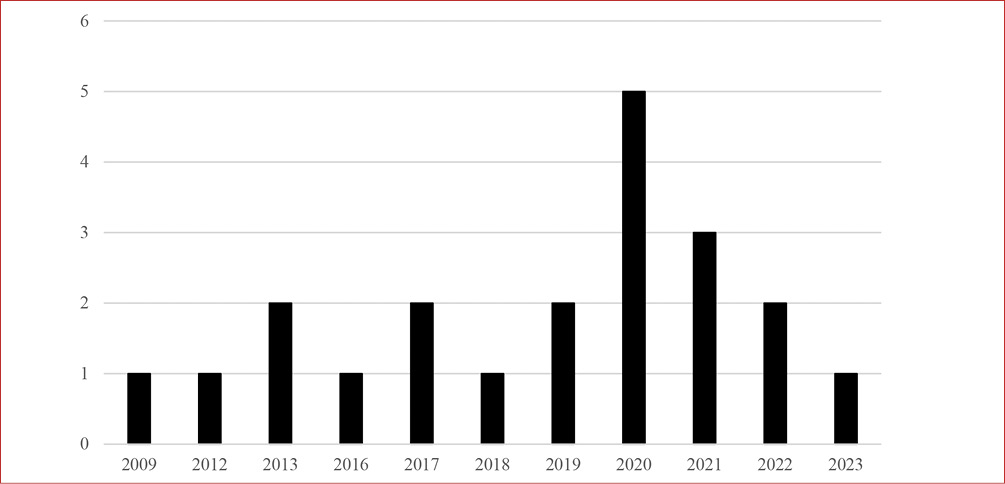

The distribution of studies per year (Figure 1) reveals that the topic is extremely young, with the earliest contributions published in 2009 (Mitchell et al., 2009). That is, the family business field started to pay attention to the strategic renewal 36 years after Burgelman’s seminal article in 1983.

After Mitchell et al.’s (2009) study, and until 2016 the number of studies published was none or 1 or each year, with the exception of 2013, when 2 articles were published. However, since 2017, the interest in the topic began to grow. Since 2017, at least one work has been published yearly, showing a peak in 2020 (with five works). From studies included in this review, 52.38% have been published between 2020 and today, when the year 2022 has not yet come to an end (despite a study that will be published in 2023 has been included in our review).

In order to carry out our systematic review of family business and strategic renewal, we have analyzed the works compiled in terms of their content, exploring four thematic axes: (1) methodological and sample diversity, (2) theoretical diversity, (3) conceptualization of the family business and strategic renewal, and (4) key findings.

Figure 1. Strategic renewal publication distribution (2009-2022)

3.1. Methodological and sample diversity

Studies included in our review (Table 3) are mainly empirical studies (18 studies), with the remaining 3 studies being of a theoretical nature (Abdelgawad & Zahra, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2009; Randolph et al., 2017).

Theoretical studies suggest that successor discretion (Mitchell et al., 2009) and religion (Abdelgawad & Zahra, 2020) promote the strategic renewal in the family business context. Furthermore, Randolph et al. (2017) propose a typology of business orientations and argue that family firms that intend to transfer ownership to next generations of family members tend to invest more in strategic renewal, even if doing so the immediate benefits for existing members are reduced.

The empirical studies may be classified in two groups regarding methodological diversity (Table 3). The first group includes those studies that apply (9 studies) qualitative methodologies, and the second group includes the studies that apply quantitative methodologies (9 studies). This implies that the distribution between qualitative (50%) and quantitative studies (50%) is slightly more balanced than in the literature on strategic renewal in general (49.02% versus 50.98%, according to the Schmitt et al.’s review, published in 2018).

Among the studies included in the first group (9 studies), the 55.56% of qualitative designs are in-depth single cases (Di Toma, 2012; Jones et al., 2013; Németh et al., 2017; Sievinen et al., 2020a, 2020c), with the 44.44% of designs being multiple case studies (Anggadwita et al., 2022; Lionzo & Rossignoli 2013; Mzid et al., 2019; Sievinen et al., 2020b).

The second group of empirical studies comprises those studies that apply quantitative methodologies (9 studies). All of the studies included in this group are based on primary information reached via questionnaires (Au et al., 2018; Cucculelli et al., 2016; Giang & Dung, 2021; Huynh, 2021; Issah et al., 2023; Luu, 2022; Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020; Weimann et al., 2021). In some cases, the survey data are complemented with data retrieved from a secondary database (e.g., Cucculelli et al., 2016; Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020). Further, all quantitative studies are cross-sectional studies. In terms of methodologies used for the data analysis, a 44.44% of quantitative studies performed regression analysis (Au et al., 2018; Cucculelli et al., 2016; Issah et al., 2023; Weimann et al., 2021), another 44,44% used structural equations modelling, in all cases by using the Partial Least Squares software (Giang & Dung, 2021; Huynh, 2021; Luu, 2022; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020) and the last 11.11% used two-step cluster analysis (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019).

Regarding sample diversity (see Table 3), only Au et al. (2018) and Issah et al. (2023), have researched firms from more than one country, 26 and 69 countries respectively. In the case of Issah et al. (2023), they used data from a global survey conducted by the Successful Transgenerational Entrepreneurship Practices (STEP) global consortium, which is an independent association with members from universities around the world.The remaining empirical papers have researched firms from only one country, with Finland (Sievinen et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2020c), Italy (Cucculelli et al., 2016; Di Toma, 2012; Lionzo & Rossignoli, 2013) and Vietnam (Giang & Dung, 2021; Huynh, 2021; Luu, 2022) being the most researched countries (with 16.67% of empirical studies studying each country), followed Spain (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020), researched by the 11.11% of the studies included in our literature review. Other countries researched are Germany (Weimann et al., 2021), Hungary (Németh et al., 2017), Indonesia (Anggadwita et al., 2022), Tunisia (Mzid et al., 2019), and United Kingdom (Jones et al., 2013). It is also interesting to note that 94.44% of empirical studies (17 from 18) study exclusively family firms, with the only exception being Pérez-Pérez and Hernández-Linares (2020), who researched both family and non-family firms

Finally, focusing on studies with a quantitative design, it seems necessary to notice that they are based on samples of different size, ranging from 82 (Luu, 2022) to 2139 firms (Issah et al., 2023), with the average size of the samples being 512 firms. Considering the size of firms researched, five studies focused on small and medium- size firms (Cucculelli et al., 2016; Luu, 2022; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020; Weimann et al., 2021), one study focused on medium to large companies (Au et al., 2018) and one on firms of all sizes (Issah et al., 2013). The two remaining studies (Giang & Dung, 2021; Huynh, 2021) do not report about the size of firms included in their samples. The composition of samples by industry sectors also varies. Around 33.33% of studies (Issah et al., 2013; Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020) analyze companies from all sectors; a 11.11% of studies focus on manufacturing industries (Cucculelli et al., 2016) and another 11.11% (Weimann et al., 2021) focus on firms operating in manufacturing, transport, service activities, suppliers, agriculture, building, trade and communication sector, among other works. Finally, four studies do not provide any information about the industry sectors studied (Au et al., 2018; Giang & Dung, 2021; Huynh, 2021; Luu, 2022).

|

Table 3. Summary of studies about strategic renewal and family firm |

|||||

|

Author/s (year) |

Study type |

Main theory |

FB definition |

Sample short description |

Key findings |

|

Mitchell et al. (2009) |

T |

Social cognitive theory |

n.a. |

- |

To avoid typical post-succession issues in FBs, managerial discretion (the ability to freely formulate, modify and enact future plans) may constitute a key factor for enabling strategic renewal. |

|

Di Toma (2012) |

E/Ql |

AT |

n.a. |

Case-study of an Italian FB that operates in the public sound and professional audio system market. |

Appropriate changes in the corporate governance structure may facilitate the firm’s ability to pursue a strategic renewal. |

|

Jones et al. (2013) |

E/Ql |

DC |

Ownership |

A sixth generation FB, from Liverpool that operates in retail, distribution, financial services and shipping industries. |

Strategic flexibility based on cognition business and effective decision-making routines enable rapid response as new opportunities arise. |

|

Lionzo & Rossignoli (2013) |

E/Ql |

Organizational learning theory |

Ownership |

3 Italian family SMEs |

The culture and experience accumulated by family leaders help them identify critical environmental threats and recognize the need for a strategic change. The knowledge sharing and integration are key tasks of family members if they want to succeed in strategic renewal. |

|

Cucculelli et al. (2016) |

E/Qn |

SEW |

Management, ownership |

220 Italian medium sized FBs operating in industrial sectors |

Company renewal is dependent upon corporate governance, which directly affects the type and growth potential of new products. Family management limits the products that renew technological capabilities, while increasing the offerings that help to open new foreign markets. |

|

E/Ql |

System theory, RBV |

Work, values, continuity |

A medium second-generation FB in western Hungary operating in hospitality services industry |

The generational change in FBs may imply changes in strategic renewal, such as carrying out a renewal, reduction and concentration of activities or new management strategies. |

|

|

Randolph et al. (2017) |

T |

n.a. |

n.a. |

- |

Authors develop a typology of corporate entrepreneurship in FBs and suggest that the varied corporate entrepreneurship orientations (strategic renewal included) of FBs are impacted by the duality of a family’s distinct intention to pursue transgenerational succession and the firm’s unique capabilities to acquire external knowledge. |

|

Au et al. (2018) |

E/Qn |

n.a. |

Continuity, governance, management, ownership, self-definition |

959 FBs from 26 countries |

Family CEO is negatively related to strategic renewal across cultures, but this relationship is attenuated by uncertainty avoidance and power distance. Multigenerational involvement is positively related to renewal, and this relationship is enhanced by cultural dimensions. |

|

Mzid et al. (2019) |

E/Ql |

SFBT |

n.a. |

4 Tunisian FBs in clothing, food, plastics and catering industries |

Financial capital enhances the potential for adaptive, renewal and appropriation capacity, and, ultimately, resilience. International ties contribute to firms’ strategic renewal. Hence, it is necessary for firms to build an enduring trust with their external partners. |

|

Pérez-Pérez et al. (2019) |

E/Qn |

KBV, SEW |

Management, ownership, self-definition |

288 small and medium-sized Spanish FBs from all industries. |

Strategic flexibility and knowledge management allow and constrain strategic renewal. FB’ strategic renewal orientation is impacted by the CEO’s characteristics, the level of family involvement and the firm’s unique capabilities of acquiring and promoting knowledge. Knowledge management practices boot strategic renewal. |

|

Abdelgawad & Zahra (2020) |

T |

Organizational identity theory |

Ownership; management |

n.a. |

Authors propose that a religious identity determines FBs’ spiritual capital, which influences strategic renewal activities (e.g., conflict resolution and resource allocation). Spiritual capital can be a double-edged sword when FBs pursue strategic renewal |

|

Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares (2020) |

E/Qn |

n.a. |

Self-perception |

238 Spanish SMEs (181 FBs and 57 non-FBs) from all industries |

Strategic renewal is strongly shaped by some KM processes (KM flow and KM generation). |

|

Sievinen et al. (2020a) |

E/Ql |

Institutional action theory |

Continuity, governance, management, ownership |

A Finnish FB from lighting controls and luminaire component industry. |

The owners’ active involvement is an important factor contributing to the process of strategic renewal. Some characteristics of FBs such as the importance of tradition, a long-term perspective and strong mental models also deceptive influence the renewal process. |

|

Sievinen et al. (2020b) |

E/Ql |

n.a. |

Continuity, governance, management, ownership |

2 Finish FBs focus on lighting solutions and wood products. |

Some organizational rules display higher stability than others, but rules are not change-hindering or -facilitating per se but their influence on the strategic renewal is contextual. However, by refusing to alter the rules owners adhere to if the contingencies change and the rules are no longer fit for the new environment, the owners can impede change. |

|

Sievinen et al. (2020c) |

E/Ql |

n.a. |

Continuity, governance, management, ownership |

A Finnish mature FB at the cousin consortium stage and operating in the lighting market. |

The advisory role of non-family board members evolves from inertia preservation to inducing stress. The role, content, intensity, and locus of advice can change as the renewal proceeds, reflecting the stage of the renewal process and resource configuration of the firm. |

|

Giang & Dung (2021) |

E/Qn |

Intrapreneurship theory |

Ownership |

368 key role non-family employees at 109 family export and import firms in Vietnam |

Transformational leadership positively influences non- family employee intrapreneurial behaviour. This relationship is mediated by adaptive corporate culture and psychological empowerment. |

|

Huynh (2021) |

E/Qn |

Corporate entrepreneurship theory, international business theory |

n.a. |

379 employees at 132 family export and import firms in Vietnam. |

Strategic renewal of employees assumes a crucial role in the construction of theory in the context of international business. Strategic renewal at the international level are actions that allow the company to take advantage of market opportunities to innovate strategies from products to operating processes, thus improving the organization's competitiveness in the international market. |

|

Weimann et al. (2021) |

E/Qn |

Network theory |

Continuity, governance, ownership |

181 German FBs of manufacturing, transport, service activities, suppliers, agriculture, building, trade and communication industry. |

Social ties do not negatively influence the strategic renewal of FBs. DC are positively associated to strategic renewal in FB context. |

|

Anggadwita et al. (2022) |

E/Ql |

RBV, strategic management approach |

Ownership |

5 FBs in Indonesia |

Women’s successors in FBs can be a valuable source of resilience because they contribute to a company’s adaptive capacity, strategic renewal and appropriation capacity. |

|

Luu (2022) |

E/Qn |

AT, stewardship theory |

Continuity, governance, management, ownership |

82 small and medium FBs in Vietnam. |

Family board members with transformational leadership qualities play an essential role in developing non-family employee SR. |

|

Issah et al. (2023) |

E/Qn |

n.a. |

Governance, ownership |

2139 FBs observations from 69 countries |

In comparison to the later generations, founding generation-managed FBs only do better at strategic renewal as a response to the crisis when they have sufficient managerial capabilities. |

|

A = article; AT = agency theory; B= book; CEO = chief-executive officer; DC=dynamic capabilities; E = empirical; FB = family business; KBV = knowledge based-view; n.a. = not available; Ql= qualitative; Qn = quantitative; RBV = resource based view; RDT = resource dependence theory; SEW = socioemotional wealth; SFBT= sustainable family business theory |

|||||

3.2. Theoretical diversity

In this section we focus on the theoretical framework used by the literature given that a strong theory delves into underlying processes to understand the systematic reasons for a particular occurrence or nonoccurrence of acts, events, structure, and thoughts (Sutton & Staw, 1995), We observed that the most used theory is resource-based view (RBV; Barney, 1991) and its variants. RBV (Barney, 1991) provides a strategic theoretical framework to assess the competitive advantages of firms based on their unique resources and capabilities, which in the case of family firms emerge because of the systems interaction between the family, its individual members, and the business and are called familiness (Habbershon & Williams, 1999). This theory has been used by two studies included in our review (Anggadwita et al., 2022; Németh et al., 2017). Thus, Anggadwita et al. (2022), drawing on RBV and strategic management approach, propose a model to explain how family businesses take advantage of new opportunities (strategic renewal capacity) and become more proactive in dealing with shocks in the environment, creating resilience in the family business. Similarly, Németh et al. (2017) combine RBV with system theory, which focuses on viewing the world in terms of the interrelationships of objects with one another (Barrett, 2014), to explain how the family businesses’ generational changes may promote their strategic renewal. In addition, RBV variants, such as dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997) and knowledge-based view (Leonard-Barton, 1992) have been also used by one study each (Jones et al., 2013 and Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019, respectively). Thus, Jones et al. (2013) draw on this theory to examine development and capability to self-renewal of the only surviving family-owned Liverpool shipping company. While Pérez-Pérez et al. (2019) combine arguments from knowledge-based view with arguments taken from socioemotional wealth (SEW, Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007) to study the existence of heterogeneous groups of family firms in terms of strategic renewal.

Following RBV, we found that agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), and SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007) wereused in two studies each. On the one hand, agency theory focuses on potential conflict between the principal (e.g., owner of the company), and the agent (e.g., a non-owner manager), given the assumption that the agent will behave opportunistically (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Di Toma (2012) was pioneered at the application of this theory to the study of strategic renewal, reporting that appropriate changes in the corporate governance structure contributes to pursue a strategic renewal. Luu (2022) combines it with stewardship theory, despite stewardship theory has been often considered contrary to agency theory (Hernández-Linares & López-Fernández, 2018), and proposes a model to explain the relationship between the transformational leadership of family board members and the strategic renewal of non-family employees. On the other hand, SEW helps explain why family firms behave distinctively and is considered as the most important differentiator of the family firm as a unique entity (Berrone et al., 2012). Thus, Cucculelli et al. (2016) adopted arguments from this theory exclusively to empirically demonstrate that strategic renewal is dependent upon corporate governance. After, Pérez-Pérez et al. (2019) complemented the arguments taken from SEW with arguments taken from knowledge-based view (Leonard-Barton, 1992), one of the RBV variants, and empirically demonstrated that knowledge management practices boot strategic renewal.

Other theories have been adopted only once in the studies included in our sample. Thus, for example, social cognitive theory (see Wood & Bandura, 1989), a theory of human agency that emphasizes the duality of agency and structure, is used by Mitchell et al. (2009) to theoretically analyze the role of agency and cognition in family business-based entrepreneurial action. Organizational learning theory (Crossan et al., 1999) is used by Lionzo and Rossignoli (2013) to study the process by which knowledge is integrated throughout the firm to facilitate strategic renewal, paying special attention to the family’s role in starting and perpetuating the process of learning and change. Sustainable family business theory, which is based on general systems theory and links the company with the family (Danes & Brewton, 2012) is used by Mzid et al. (2019) to explore the role of family capital in family business’ resilience. Organizational identity theory (Albert & Whetten, 1985), which posits that organizations develop a sense of identity that reflects their core values and beliefs, is used by Abdelgawad and Zahra (2020) to propose that the religious identity determines family business’ spiritual capital, which influences its strategic renewal activities. Similarly, institutional action theory (March & Olsen, 1989), which highlights the importance of identity in decision-making processes, is used by Sievinen et al. (2020a) to deepen in the link between family firm corporate governance and strategic change and to study the decision-making of family firms at the micro-level. Specifically, Sievinen et al. (2020a) show that contextually relevant identities, such as those of a board member and an ex-executive (someone who has served as an executive in the past) can increase the response flexibility of the owners as they can shift their focus from being in a control role to resource provision. Network theory (Granovetter, 1985) is used by Weimann et al. (2021) because family firms are considered socially embedded they analyze the influence of this social resource of family firms in their corporate entrepreneurship. Other authors argue the use the intrapreneurship theory (Gian & Dung, 2021), corporate entrepreneurship theory or international business theory (Huynh, 2021), although in these cases we refer to literatures/perspectives instead of mainstream theories.

Finally, the 28.57% of the literature do not formally claim to apply any theory to support their arguments and investigations, although some scholars reveal the perspective in which are based their arguments, this being the case, for the example, of Au et al. (2018), who based on the literature of dominant logic perspective.

3.3. Conceptualization of the family business and strategic renewal

Although family business literature has emphasized that the field would certainly benefit from greater conceptual clarity (Hernández-Linares et al., 2018; Hernández-Linares & López-Fernández, 2018), only the 76.19% of studies included in our systematic literature review do provide an explicit definition of the family business concept or operationalize it in any way. This percentage is higher than that reported by a recent review on entrepreneurial orientation and the family business (69.23% is reported by Hernández-Linares & López-Fernández, 2018).

Among the 16 works that explicitly define family business, the ownership criterion, referred to the control of the company’s capital by the family (Diaz-Moriana et al., 2019; Hernández-Linares et al., 2017) has been the most used. The 87.50% of studies defining family firms considered ownership (i.e., having control of voting rights), either as the sole defining criterion (Anggadwita et al., 2022; Giang & Dung, 2021; Jones et al., 2013; Lionzo & Rossignoli, 2013) either in conjunction with other criteria. Three studies have defined family firm based on ownership and another criterion, this being family management (Abdelgawad & Zahra, 2020; Cucculelli et al., 2016), understood as the involvement of family members in the firm’s management (Hernández-Linares et al., 2018), or strategy (Issah et al., 2023), referred to the family control over its company’s strategic direction. In remaining studies that have used family ownership as definitional criterion, this criterion has been used in combination with two (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019) or more criteria (e.g., Sievinen et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2020c).

The second definitional criterion most used is the family management, used by the 50% of studies that define family firms. This criterion has always been used in conjunction, at least, with the ownership criterion (Abdelgawad & Zahra, 2020; Cucculelli et al., 2016), which implies the current situation in the family business literature in general, these two definitional criteria are often used in conjunction (Diaz-Moriana et al., 2019; Hernández-Linares et al., 2018). Others add to these criteria the self-perception (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019), understood as “the way in which the principals in a business identify it” (Hernández-Linares et al., 2018, p. 942), the family continuity (Weimann et al., 2021), referred to address the intention to have a family business managed in the future by family members, or even several definitional criteria. Thus, for example, Sievinen et al. (2020a, 2020b, 2020c) and Luu (2022), in addition to use management and ownership as definitional criteria, use continuity and governance; and Au et al. (2018) add to these four definitional criteria (continuity, governance, management, ownership) a fifth criterion: the self-definition.

After ownership and management, the definitional criteria most used are continuity and governance, used by seven studies each (43.75% of studies defining family firm). In six of these seven studies, family continuity and family governance are applied in conjunction and with other definitional criteria (Au et al., 2018; Luu, 2022; Sievinen et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2020c; Weimann et al., 2021).

It is interesting to note that among studies that have not defined family firms based on ownership, Németh et al. (2017) defined the family firm based on family work, family values and continuity, the family business conceptualizations based on more than two criteria have always included the ownership criterion, accompanied by others such as continuity and government (Weimann et al., 2021), management and self-definition (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019), or management, governance and continuity (Luu, 2022).

Strategic renewal has been explicitly defined by 76.19% of the studies reviewed, that is, by 16 out of 21 studies. However, strategic renewal has been defined differently, which is not surprising, since “(d)espite its wide recognition and importance across various research domains, there is no consensus in the literature on what strategic renewal means and how it differs from other, related concepts, such as corporate entrepreneurship (…), strategic change (…) and strategy process” (Schmitt et al., 2018, p. 84). Most of studies (e.g., Isaah et al., 2023; Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020; Sievinen et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) have defined strategic renewal following Schmitt (2018), who establishes that strategic renewal is a dynamic management process that allows organizations to alter their path dependence by replacing and transforming their strategic intent and capabilities. In this same line but based on the definitions proposed by Burgelman (1983, 1991), other scholars defined it as “an entrepreneurial process in which organizations anticipate or adapt to changing environmental demands to ensure long-term prosperity and survival” (Au et al., 2018, p. 604). These definitions emphasize the key role of strategic renewal to address emerging environmental opportunities and risks for family business’ long-term survival and prosperity (Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020; Schmitt et al., 2018). Furthermore, others understand strategic renewal “as the firm’s ability to envision the future” (Mzid et al., 2019, p. 254) or the skills “to visualize upcoming opportunities from an innovative perspective to propose solutions and reconsider practices” (Anggadwita et al., 2022, p. 6).

The way in which quantitative studies have operationalized the strategic renewal is also diverse. While some scholars have adopted previously validated scales, others have developed their own scales. Among studies that adopted scales consolidated in literature, we identify two groups. The first group is constituted by the two studies that have used strategic renewal scales and includes Luu’s study (2022), which measured employee strategic renewal by using the 6-item scale from Gawke et al. (2019), and the Issah et al.’s (2023) study, which uses the Klammer et al.’s (2017) scale. The second group is constituted by those studies (4) that adopted items from broader scales. Specifically, two studies (Giang & Dung, 2021; Huynch, 2021) adopted the 3-item measurement scale from Do and Luu (2020) to measure the strategy renewal, this being considered as one dimension of the intrapreneurial behavior variable. In similar sense, Pérez-Pérez and Hernández-Linares (2020) used the items from Burgers and Covin’s (2016) scale corresponding to the strategic renewal dimension, and Weimann et al. (2021) adopted the four items from the Zahra’s (1996) scale corresponding to the strategic renewal dimension.

Among the studies that developed new scales, Pérez-Pérez et al. (2019) used a 5-item scale based on Burgers and Covin (2016), Simsek et al. (2007), and Zahra (1996); while Au et al. (2018) developed a 7-item scale, which are in line with strategic renewal measure used in Kearney and Morris (2015) and Zahra (1991, 1993).

Finally, Cucculelli et at. (2016) assessed strategic renewal with two primary variables: number of new patents the firm achieved in the process of its new product introductions and new foreign market entries that followed the new product introduction.

The diversity of conceptualizing and assessing strategic renewal in the family business field is in line with the lack conceptual clarity detected in general literature by Schmitt et al. (2018) and suppose a difficulty for enabling cross-fertilization and cumulative knowledge development across the different theoretical streams (Schmitt et al., 2018).

3.4. Consideration of the strategic renewal construct within the research models and discussion of empirical evidence

In this section we analyze the findings of the strategic renewal review. We observed that those studies with qualitative design support/argue/contend that family business’ strategic renewal is promoted by the active participation of the owners (Sievinen et al., 2020a), the generational change that takes place in family businesses (Németh et al., 2017), appropriate changes in the corporate governance structure (Di Toma, 2012) and by international links (Mzid et al., 2019). In addition, these studies report that knowledge sharing and integration are key tasks of family members for the success of strategic renewal (Lionzo & Rossignoli, 2013), that strategic flexibility enables rapid response to as new opportunities arise (Jones et al., 2013), that refusing to alter the organizational rules by adhering to if the contingencies change, the family business’ owners can impede change (Sievinen et al., 2020b), and that the advisory role of non-family board members may evolve from inertia preservation to introducing stress (Sievinen et al., 2020c). In addition, Anggadwita et al. (2022) report that in family firms, women’s successors contribute to a company’s adaptive capacity, strategic renewal and appropriation capacity, that is, to corporate resilience.

To explain the main findings of quantitative studies we rely on Table 4. As we can see, when strategic renewal has been considered as an independent construct, in all cases, it has been considered as a dependent variable (Au et al., 2018; Issah et al., 2023; Luu, 2022; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020; Weimann et al., 2021). These works report that knowledge management flow and knowledge management generation (Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020), interfamily social ties (Weimann et al., 2021), sociocultural context of the firms (Au et al., 2018) and managerial capabilities (Issah et al., 2023) promote strategic renewal, although this last relationship is moderated by uncertainty avoidance. Moreover, Luu (2022) reports that family board’s members with transformation leadership qualities play a key role in developing non-family employees’ strategic renewal; while Issah et al. (2023) find that family businesses managed by founding generation are better than those managed by later generations at strategic renewal as a response to the crisis when they have sufficient managerial capabilities. Finally, Cucculelli et al. (2016) find that externally managed firms behave like founder run firms, even if their preference for risky products receives weak statistical support and that risky products become appealing for family managers, as they can help survival when a firm is in financial crisis. In addition, they find that family firms’ favoring of less risky product introductions will extend the firm’s market reach.

|

Author/s (year) |

Independent variable |

Dependent variable |

Moderating variable |

Mediating variable |

|

Strategic renewal is considered as a dependent variable |

||||

|

Cucculelli et al. (2016) |

Risky new product introductions |

Strategic renewal |

||

|

Au et al. (2018) |

Sociocultural context |

Strategic renewal |

Uncertainty avoidance |

|

|

Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares (2020) |

Knowledge management generation, knowledge management flow |

Strategic renewal |

||

|

Weimann et al. (2021) |

Bind social ties |

Strategic renewal |

||

|

Luu (2022) |

Idealised influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, individualised consideration, psychological ownership, nonfamily employee strategic renewal, transformational leadership of family board members. |

Strategic renewal |

Psychological ownership |

|

|

Issah et al. (2023) |

Managerial capabilities |

Strategic renewal |

Founding generation |

|

|

Strategic renewal is considered as part of a broader construct |

||||

|

Giang & Dung (2021) |

Transformational leadership, adaptive corporate culture, employee psychological empowerment |

Intrapreneurial behavior* |

Adaptive corporate culture, employee psychological empowerment |

|

|

Huynh (2021) |

Transformational leadership, employee psychological empowerment |

International intrapreneurship*, |

Employee psychological empowerment |

|

|

Note: Pérez-Pérez et al. (2019) do not study relationships among variables (therefore, we cannot identify dependent or independent variables), but the existence of heterogeneous groups of family firms in terms of knowledge management, strategic flexibility, and strategic renewal. *Strategic renewal is considered a dimension of these variables. |

||||

Among the works that consider the strategic renewal as a dimension of another construct,

Giang and Dung (2021) study the strategic renewal as a dimension of intrapreneurial behavior, a second-order construct, and report that transformational leadership has a positive effect on employee intrapreneurial behavior. Also, they report that adaptive corporate culture and non-family employee psychological empowerment is directly and significantly related to their intrapreneurial behavior. Moreover, Huynh (2021) considers strategic renewal as a dimension of the international entrepreneurship construct (also a second-order construct) and reports that transformational leadership and employee psychological empowerment boost employee international intrapreneurship, although the relationship between transformational leadership and employee international intrapreneurship is partially mediated by employee psychological empowerment.

4. Future Research Directions

The third step established by Tranfield et al. (2003) to carry out a systematic literature review is the reporting and dissemination of results, making room to draw future strand or avenues for research and practical implications. Therefore, taking our systematic and comprehensive analysis of 14 years of research on strategic renewal and family business as starting point, in this section we present some research questions (RQ) that we consider key to advance our knowledge about the antecedents and outcomes of strategic renewal in the family business.

4.1. Strategic renewal’s antecedents

The systematic analysis performed in the previous section reveals that knowledge management flow and knowledge management generation (Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020), interfamily social ties (Weimann et al., 2021) or sociocultural context of the firms (Au et al., 2018) constitute antecedents for strategic renewal. However, other possible antecedents of strategic renewal deserve to be studied.

Specifically, managerial choices are influenced by the desire to preserve the family’s SEW (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019). Thus, for example, when SEW is threatened, family businesses make decisions to avoid the loss of SEW, in spite of their economic efficiency (Gottardo & Moisello, 2015). It is in line with the idea that strong bonds of family to the company, can lead to a desire to preserve the status quo and to resist change (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019). These arguments, the recent advancements linking SEW dimensions to innovation practices or outcomes in family firms (Bauweraerts et al., 2022; Gast et al., 2018), and the existence of both a bright and a dark side of SEW (e.g., Kellermanns et al., 2012) lead us to emphasize here the interest of investigating how SEW could affect strategic renewal. Therefore, we propose:

RQ 1. How does SEW affect the strategic renewal of family firms?

Moreover, lessons from past experience are used to shape organizational strategy (Wadhwani et al., 2018) and facilitate change within continuity (Maclean et al., 2018), Indeed, research shows that, from a path dependence perspective (Liebowitz & Margolis, 1995), firm strategy is heavily influenced by its past history (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015; Lorenzo-Gómez, 2020). Indeed, our literature review reveals that the culture and experience accumulated by family leaders help them identify critical environmental threats and recognize the need for a strategic change (Lionzo & Rossignoli, 2013). However, Lorenzo-Gómez (2020) posits that decisions adopted by family businesses in the past could create a dominant pattern that acts as a barrier to change processes. Therefore, we call for researching how past experiences of mature family firms can influence their strategic renewal. Consequently, we propose:

RQ 2. How family legacy/history affects the strategic renewal of family firms?

Our systematic analysis also reveals that, so far, literature on the confluence between strategic renewal and family firms has not paid attention to key characteristics of family firms, as their long-term orientation, i.e., the “tendency to prioritize the long-range implications and impact of decisions and actions that come to fruition after an extended time period” (Lumpkin et al., 2010, p. 241). It seems a bit surprising given that research provides arguments that lead us to think that long-term horizon often attributed to family firms (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005; Zahra et al., 2004) could impact a firm’s strategic renewal. Thus, for instance, literature points that the intention of the founders to build a lasting legacy over time may lead family firms to have a more conservative approach to strategic decision making (Gentry et al., 2016; Lorenzo-Gómez, 2020). However, research also reports a positive relationship between long-term orientation and corporate entrepreneurship (Eddleston et al., 2012). In this sense, and as a long-term orientation is an organizational culture that favors patient investments in time-consuming activities (e.g., Zahra et al., 2004), it seems reasonable to think that it can affect the strategic renewal, given that any strategic transformation is time and resources consuming. Therefore, we encourage scholars to answer the following research question:

RQ 3. How family firms’ long-term horizon affects their strategic renewal?

It is also surprising that, with the exceptions of Mitchell et al. (2009) and Anggadwita et al. (2022), who study the influence of the successor discretion in the strategic renewal’s promotion and the role of women successors in family business’ resilience respectively, research on strategic renewal and family firms have under noticed one of the major challenges facing the family firms: the succession (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Corona, 2021; Corrales-Villega et al., 2019). According to family development theory (Hill & Duvall, 1948), families go through distinct stages of development, and face processes of change (for instance, divorces). It would be interesting, hence, to explore whether and how the transition from one family’s development stage to another influences the firm’s ability to renew itself. Specifically, we call for research how different types of succession (intra-family succession or external succession, planned versus unexpected, etc.) influence firm’ strategic renewal. Consequently, we propose:

RQ 4. How family’s development stages, and specifically succession processes, affect the strategic renewal of family firms?

Finally, our review reveals that some knowledge-related variables are antecedents of strategic renewal in family firms (Lionzo & Rossignoli, 2013; Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020). In this sense, literature reports that involvement of several family’s generations in the company is a unique predictor of entrepreneurial behavior in family firms (Kellermmans et al., 2008) and that family members from newer generations tend to be a driving force for change (Kepner, 1991). As the newest generations may offer greater input and new and diverse perspectives to modernize organizational objectives and strategies (Handler, 1992; Kellermanns et al., 2008), it seems reasonable to think that the involvement of several family generations in the firm’s board or top management team (i.e., where each generation to have a say in the strategy making of the firm) may influence its ability to renew itself. Therefore, and considering that we encourage scholars to answer the following research question:

RQ 5. How does the involvement of several family’s generations in the top management and/or board influence the capability of family firms to renew themselves?

4.2. Strategic renewal’s outcomes

According to Schmitt et al.’s (2018) review, “since most organizations need to transform themselves at one time or another, strategic renewal is a key consideration in understanding their long-term survival and prosperity” (p. 81). However, in the family business field, the relationship between strategic renewal and survival is merely assumed, but it has not been empirically corroborated. Considering the known family firms’ high mortality rate (Dyer, 2021; Ghee et al., 2015), this lack of empirical evidence results a bit surprising because increasing family businesses’ survival rate has intrigued scholars, practitioners, and consultants (Stamm & Lubinski, 2011), becoming a be considered one of the most difficult challenges faced by both public policies and scholars (Hernández-Linares et al., 2022). Therefore, and convinced the progress of science must not be based on assumptions, we propose a new research question:

RQ 6. How family firms’ strategic renewal impacts on their survival?

According to Schmitt et al.’s (2018) literature review “every organization faces the dilemma of either maintaining continuity or engaging in strategic renewal. Continuity ensures reliability and cohesion, but strategic renewal is equally important to enable innovation” (p. 94). Given that this dilemma presents a singular character in family firms because of their wish to transfer the legacy to the next generation (Brigham et al., 2015; Moreno-Menéndez et al., 2021) and to keep the company in the family (Casson, 1999), as well as the existence of family-oriented goals (Chrisman et al., 2012; Kotlar & De Massis, 2013), such as family cohesion and well-being. Therefore, we propose the following avenue for future research:

RQ 7. How firm’s strategic renewal influences family cohesion and well-being?

Finally, while in the family business field the research on business exit has focused on entrepreneurial exit from a single venture and has overlooked the case of business families that manage a portfolio of businesses and face more than exit process (Akther et al., 2016). However, it is broadly accepted that successful portfolio entrepreneurship involves renewal and constant entry into and exit from business activities (Dess et al., 2003; DeTienne & Chirico, 2013) because a successful business exit can, for example, free up new resources (Carnahan, 2017) and lead to strategic renewal and the foundation of a new firm (Ren et al., 2019). Therefore, it would be interesting to explore how the level of strategic renewal of a portfolio of family firms influences the way a family voluntary disinvests in a business (e.g., selling, shutting down, etc.) both in ordinary economic conditions as in situations of economic crisis. Therefore, we propose a last research question:

RQ 8. How portfolio of family firms’ strategic renewal influences the choice of business exit?

Besides of these research questions, we joint to the call of Mitchell et al. (2009) who state that more research is needed to develop a theory that describes how factors at the individual level can be combined with factors at the family level to positively affect the strategic behavior of individuals.

Finally, although the quantitative research on the strategic renewal in family firms is scant yet, it is fully from cross-sectional nature, wich impides establish causal relationships. Therefore, we call for further quantitative research, but specially we encourage scholars to perform transversal studies that allow us overcame the cross-sectional studies’ limitations. Similarly, we strongly encourage scholars to research family firms’ strategic renewal of contexts not investigated until now, such as Canada or United States of America, with well-developed knowledge economies, with different general competitive conditions (Chen et al., 2007) for firms. It will allow us to compare results of these studies with those found in economies that are in a transitioning situation (e.g., Vietnam) and will contribute to the generalization of findings.

5. Conclusion

Our systematic review of literature on strategic renewal and family firms contributes to both family business literature and strategic renewal literature in two ways. First, this is the first study in systematizing, integrating and critically examining the corpus of knowledge on strategic renewal and family firm, a flourish literature that is very fragmented (indeed, only two journals have published more than one article about the topic), which add value to our compilation and analysis. Therefore, we contribute to literature by providing a chronological account of the relevant research. Second, based on our review and systematization of literature, which relies on a structured, transparent and reproducible method of selecting and assessing studies (Tranfield et al., 2003), we identify gaps in the literature and provide scholars with a future research agenda that endows strategic renewal and family business. Therefore, we trust our study constitutes an impulse for further research.

In addition, we share with Ge and Campopiano (2022) that the main purpose of a systematic literature review is to systematize existing knowledge about a topic and offering avenues for future research. However better understanding the status quo about strategic renewal in family business has also practical implications for managers and consultants. For family businesses’ managers, our study offers a guidance on how to promote strategic renewal. Thus, for instance, managers may find useful to establish practices of knowledge management (Pérez-Pérez & Hernández-Linares, 2020) as an enabling of strategic renewal in their firms. In addition, our systematic literature review offers family businesses’ consultants some insights of how advice firms to face change and advance their understanding of strategic renewal within family firms.

However, this works is not exempt of limitations. First, we limited our search to studies published in English and available in the WoS and Scopus databases. Although our sample’s publications thus represent relevant literature, having searched in other databases could have provided us with more information with which we would have reached other results. Therefore, future systematic reviews can include conference proceedings and studies published in other languages and available via other databases. Second, we are conscious that the number of publications included in our review is slightly lower than those included in other review articles in the family business field (De Massis et al., 2013). Nevertheless, in our view, this is not a serious concern given the novelty of the studies on the confluence between family business and strategic renewal, and the need to systematization of the prior literature. Third, we screened the studies included in our review manually, which subjects our process to human error. Therefore, future literature review could adopt more sophisticated and robust methods to select and filtrate the studies finally revised in order to overcome this limitation.

In conclusion, research on strategic renewal and family firms was born less than fifteen years ago (Mitchell et al., 2009), however our literature review reveals that interest in the topic is growing, and our study aims to lay the foundations for solid growth in research on the topic in the future.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the present literature review.

*Abdelgawad, S. G., & Zahra, S. A. (2020). Family firms’ religious identity and strategic renewal. Journal of Business Ethics, 163(4), 775–787. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04385-4

Akhter, N., Sieger, P., & Chirico, F. (2016). If we can’t have it, then no one should: Shutting down versus selling in family business portfolios. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10(4), 371-394. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1237

Albert, D., Kreutzer, M., & Lechner, C. (2015). Resolving the paradox of interdependency and strategic renewal in activity systems. Academy of Management Review, 40(2), 210–234. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0177

Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 263–295.

*Anggadwita, G., Permatasari, A., Alamanda, D. T., & Profityo, W. B. (2022). Exploring women’s initiatives for family business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Business Management, (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-02-2022-0014

Aparicio, G., Ramos, E., Casillas, J. C., Iturralde, T. (2021). Family business research in the last decade. A bibliometric review. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12503

*Au, K., Han, S., & Chung, H.-M. (2018). The impact of sociocultural context on strategic renewal: a twenty-six nations analysis of family firms. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 25(4), 604-627. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-07-2017-0090

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barrett, M. (2014). Theories to define and understand family firms. In H. Hasan (ed.), Being practical with theory: a window into business research. Wollongong. http://eurekaconnection.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/p-168-170-theories-to-define-and-understand-family-firms-theori-ebook_finaljan2014-v3.pdf

Bauweraerts, J., Rondi, E., Rovelli, P., De Massis, A., & Sciascia, S. (2022). Are family female directors catalysts of innovation in family small and medium enterprises? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 16(2), 314-354. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1420

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gómez-Mejía, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511435355

Brigham, K. H., Lumpkin, G. T., Payne G. Y., & Zachary, M. A. (2015). Researching long-term orientation. A validation study and recommendations for future research. Family Business Review, 27(1), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486513508980

Burgelman, R. A. (1983). Corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management: insights from a process study. Management Science, 29(12), 1349–1364. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.12.1349

Burgelman, R. A. (1991). Intraorganizational ecology of strategy making and organizational adaptation: theory and field research. Organization Science, 2(3), 239-262. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.3.239

Burgers, J. H., & Covin, J. G. (2016). The contingent effects of differentiation and integration on corporate entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal, 37(3), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2343

Cabrera‐Suárez, K., De Saá‐Pérez, P., & García‐Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource‐and knowledge‐based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37-48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00037.x

Calabrò, A., Vecchiarini, M., Gast, J., Campopiano, G., De Massis, A., & Kraus, S. (2019). Innovation in family firms: a systematic literature review and guidance for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(3), 317-355. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12192

Carnahan, S. (2017). Blocked but not tackled: who founds new firms when rivals dissolve? Strategic Management Journal, 38(11), 2189-2212. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2653

Casson, M. (1999). The economics of the family firm. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 47(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.1999.10419802

Chartered Association of Business Schools (2021). Academic Journal Guide 2021. Available at https://charteredabs.org/academic-journal-guide-2021-view/ (accessed 19 October 2022).

Chen, T., Hu, W., Shi, Q., & Yan, H. (2007). Embedded education for Computer Rank Examination. 2007 International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems, 1–4.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family-centered non-economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267-293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00407.x

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402

Corona, J. (2021). Succession in the family business: the great challenge for the family. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 64-70. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12770

Corrales-Villegas, S. A., Ochoa-Jiménez, S., & Jacobo-Hernández, C. A. (2019). Leadership in the family business in relation to the desirable attributes for the successor: evidence from Mexico. European Journal of Family Business, 8(2), 117-128. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v8i2.5193

Creevey, D., Coughlan, J., & O’Connor, C. (2022). Social media and luxury: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 24(1), 99-129. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12271

Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., & White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. The Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.2307/259140

*Cucculelli, M., le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2016). Product innovation, firm renewal and family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(2), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2016.02.001

Danes, S. M., & Brewton, K. E. (2012). Follow the capital: benefits of tracking family capital across family and business systems. In Understanding family businesses (pp. 227–250). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0911-3_14

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., & Lichtenthaler, U. (2013). Research on technological innovation in family firms: present debates and future directions. Family Business Review, 26(1), 10–31. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0894486512466258

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Majocchi, A., & Piscitello, L. (2018). Family firms in the global economy: toward a deeper understanding of internationalization determinants, processes, and outcomes. Global Strategy Journal, 8(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1199

Dess, G. G., Ireland, R. D., Zahra, S. A., Floyd, S. W., Janney, J. J., & Lane, P. J. (2003). Emerging issues in corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 29(3), 351-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00015-1

DeTienne, D. R., & Chirico, F. (2013). Exit strategies in family firms: How socioemotional wealth drives the threshold of performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1297-1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12067

*Di Toma, P. (2012). Strategic dynamics and corporate governance effectiveness in a family firm. Corporate Ownership & Control, 10(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv10i1art3

Diaz-Moriana, V., Hogan, T., Clinton, E., & Brophy, M. (2019). Defining family business: a closer look at definitional heterogeneity, in E. Memilli & C. Dibrell (eds), The Palgrave of heterogeneity among family firms (pp 333-374). US: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77676-7

Dinh, T. Q., & Calabrò, A. (2019). Asian family firms through corporate governance and institutions: a systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(1), 50–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12176

Do, T. T. P., & Luu, D. T. (2020). Origins and consequences of intrapreneurship with behaviour-based approach among employees in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(12), 3949-3969. https://10.1108/IJCHM-05-2020-0491

Dyer, W. G. (2021). My forty years in studying and helping family businesses. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 56-63. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12768

Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F. W., & Zellweger, T. M. (2012). Exploring the entrepreneurial behavior of family firms: does the stewardship perspective explain differences? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 347-367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00402.x

Gascón, S. A. (2013). Conflictos en empresas familiares. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Facultad de Ciencias Económicas.

Gast, J., Filser, M., Rigtering, J. C., Harms, R., Kraus, S., & Chang, M. L. (2018). Socioemotional wealth and innovativeness in small‐and medium‐sized family enterprises: a configuration approach. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(S1), 53-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12389

Gawke, J. C., Gorgievski, M. J., & Bakker, A. B. (2019). Measuring intrapreneurship at the individual level: development and validation of the Employee Intrapreneurship Scale (EIS). European Management Journal, 37(6), 806–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.03.0 01

Ge, B., & Campopiano, G. (2021). Knowledge management in family business succession: current trends and future directions. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(2), 326-349. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-09-2020-0701

Gentry, R., Dibrell, C., & Kim, J. (2016). Long-term orientation in publicly traded family businesses: evidence of a dominant logic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(4), 733-757. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12140

Ghee, W., Ibrahim, M., & Abdul-Halim, H. (2015). Family business succession planning: unleashing the key factors of business performance. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 20(2), 103-126.

*Giang, H. T. T., & Dung, L. T. (2021). Transformational leadership and non-family employee intrapreneurial behaviour in family-owned firms: the mediating role of adaptive culture and psychological empowerment. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(8), 1185-1205. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-03-2021-0116

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núnez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

Gottardo, P., & Moisello, A. M. (2015). The impact of socioemotional wealth on family firms’ financial performance. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 13(1), 67–77.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481-510. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780199 (Accessed 19 Dec. 2022).

Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource‐based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00001.x

Handler, W. C. (1992). The succession experience of the next generation. Family Business Review, 5(3), 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1992.00283.x

Handler Miller, C. (2008). Tales from the digital frontier: breakthroughs in storytelling. Writers Store. 2008.

Hernández-Linares, R., Diaz-Moriana, V., & Sanchez-Famoso,V. (2022). Managing paradoxes in family firms: a closer look at public politics in Spain. In O. J. Montiel, S. Tomaselli, & A. Soto (eds.). Family business debates: multidimensional perspectives across countries, continents and geo-political frontiers. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Hernández-Linares, R., & López-Fernández, M. C. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation and the family firm: mapping the field and tracing a path for future research. Family Business Review, 31(3), 318–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518781940

Hernández-Linares, R., Sarkar, S., & Cobo, M. J. (2018). Inspecting the Achilles heel: a quantitative analysis of 50 years of family business definitions. Scientometrics, 115(2), 929-951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2702-1

Hernández-Linares, R., Sarkar, S., & López-Fernández, M. C. (2017). How has the family firm literature addressed its heterogeneity through classification systems? An integrated analysis. European Journal of Family Business, 7(1-2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v7i1-2.5013

Hill, R., & Duvall, E. (1948). Families under stress. New York, NY: Harper.

*Huynh, G. T. T. (2021). The effect of transformational leadership on nonfamily international intrapreneurship behavior in family firms: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies, 28(3), 204-224. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABES-04-2021-0047

*Issah, W. B., Anwar, M., Clauss, T., & Kraus, S. (2023). Managerial capabilities and strategic renewal in family firms in crisis situations: the moderating role of the founding generation. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113486

Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., & Rau, S. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 29-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.001

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-9257-3_8

*Jones, O., Ghobadian, A., O’Regan, N., & Antcliff, V. (2013). Dynamic capabilities in a sixth-generation family firm: entrepreneurship and the Bibby Line. Business History, 55(6), 910–941. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.744590

Kearney, C., & Morris, M. H. (2015). Strategic renewal as a mediator of environmental effects on public sector performance. Small Business Economics, 45(2), 425-445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9639-z